Fanon Portarit

-

Upload

louie-bedar -

Category

Documents

-

view

239 -

download

0

Transcript of Fanon Portarit

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

1/13

W.E.B. Du Bois Institute

Frantz Fanon: Portrait of a Revolutionary IntellectualAuthor(s): Emmanuel HansenReviewed work(s):Source: Transition, No. 46 (1974), pp. 25-36Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the W.E.B. Du Bois InstituteStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2934953 .

Accessed: 18/05/2012 21:56

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Indiana University Press and W.E.B. Du Bois Institute are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Transition.

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=iupresshttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=webhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/2934953?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/2934953?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=webhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=iupress -

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

2/13

TRANSITION6

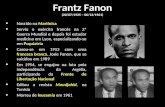

FRANTZ FANON: Portrait of a Revolutionary Intellectual

Totakepart n theAfricanevolutiont is notenougho writea revolutionaryong;youmust ashiontherevolutionith hepeople.Andf you ashiont with hepeople,hesongswill comebythemselves,ndof themselves.Inordero achieve ealaction, oumustyourself e a livingpartof Africa ndof her hought; oumustbeanelement fthatpopularnergywhichsentirelyalledorth or he reeing,heprogressnd hehappinessofAfrica.Theres noplaceoutside hat ight ortheartistorfortheintellectual ho s nothimself oncernedwithandcompletelyt onewith hepeoplen thegreatbattleofAfrica ndofsufferingumanity.

-Sekou TourePracticewithouthoughts blind; houghtwithoutractices empty.

- Kwame Nkrumah

Emmanuel HansenWhenFrantz Fanon died in December1961,he wasrelativelyunknownexcept amonghis fightingAlgeriancomrades,a small group of FrenchLeftistswho hadbeen attracted o his writings,and a handfulof radicalAfricans. Today in the United States and to a lesserextent n WesternEurope,his name s a householdword.Even the Russians,who have for a long time ignoredhis writings,are now beginningto break their silenceabout him.1 Books and articles about Fanon areappearing with increasing frequency, and researchcentreshavebeen erected n his memory. He has takenhis placetogetherwith Che Guevara,HerbertMarcuseand Regis Deblay as intellectual ndideologicalmentorof the New Left.Ironically, n Africa,wherehe spenta largeportionof his adult life dedicatinghimself fanaticallyto thefight for African liberation,he is relativelyunknownexceptin Algeria. And in Ghanawherehe livedas anAmbassadorof the AlgerianProvisionalGovernment,todayhis namehardlydrawsa ripple.There are a number of reasons why we in Africashould be concernedwith Fanon. His was the mostintriguingpersonality;he was a man full of apparentcontradictions:ne of the most assimilatedof France's

sons and yet perhaps ts most passionatecritic;a dedi-cated fighter of racial oppression,he was to die inWashington,the heart of racist America;a man towhom violence was personallyabhorrent,he was oneof the most stridentadvocatesof violence. Secondly,Fanon's ife and workprovideus witha model of whatthe African ntellectual ughtto be: a man who reflectsand yet does not allow reflection o inhibithim fromsocial action,and a man whose socialaction is guidedby thought. To himthe roleof the intellectual ndthatof the political activist were not mutuallyexclusive.Like Marxhe believedthat what matteredwas not tointerpret he world but to changeit, and he used hisknowledgeas a weaponin the battle for freedom. Forhimit was not enoughto analysea social situationandexpose its undesirablenature. One must also includea programmeof action to change the undesirablesituation,and actuallyembarkon activitieswhichleadto change. In short he was a manwho livedhis ideas.Thirdly,Fanon'smessage s of extreme mportance oAfricaand the ThirdWorld. And if today Fanon isnot readin Africa t is not becausehe is less relevant oAfrica. It is because the nationalbourgeoisiewhichholds the reigns of power in Africa is committedtomaintaining he colonial-bureaucratictate and is not

25

I I I I I I

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

3/13

TRANSITION 6prepared to propagate ideas which would change thestatus quo which benefits it so handsomely.Who was this extraordinary person whose life andideas raised a controversy which has by no means beensettled? What kind of life did he live? What were hisideas and what was his message to Africa and the ThirdWorld? What were his hopes, desires and aspirations,and what do we learn from his experience? These aresome of the questions we hope to touch on in thisarticle.

Frantz Fanon's life history falls into five main parts:his birth, bourgeois upbringing and early education onthe island of Martinique; his service in the FrenchArmy; his higher education in France and his exposureto the French intellectual Left; his work in NorthAfrica as a psychiatrist committed to the cause of theAlgerian revolution; his life and work as a professionalrevolutionary, both in North Africa and in sub-SaharanAfrica. It is useful to look at Martinique in 1925 tounderstand the social environment in which Fanongrew up and the foices which moulded his early life.MARTINIQUE: SOCIAL STRUCTURE

The island of Martinique, where Fanon was born,was one of the Overseas Departments of France. To-gether with Guadeloupe it forms what is known as theFrench Antilles. As in other French Overseasterritories,Martinican society consisted of a rigid class structure.2Society was pyramidal. On top of the pyramid was asmall group of whites, called creoles or bekes. Thewhites formed a status group and they consisted ofnative whites, and whites from metropolitan France.Small in number, they formed a closely-knit endogamouscommunity. In the eyes of most Blacks, the whitesconsisted of a single homogeneous and monolithicgroup. However, small as they were, some gradationscould be discerned among them. Edith Kovatz hasidentified three main sub-groups: gros beke, the bekemoyensand the petits blancs.3

Below the white group wasa small but fairlyprosperousmiddle class of Blacks and, at the bottom were the bulkof the Black population. As happens in all cases ofrigid class structure, those at the top of the pyramidtried to stress their social distance from those belowthem, and those at the bottom tried to stress their socialnearness to those above them. In the non-white groupalso, there were some sub-groups: the mulattoes andthe Blacks proper. The formerwere a socially well-to-dobourgeoisie, mostly city dwellers. They were mostly inthe public service, business, and in the liberalprofessions,like law and medicine. Though economically some ofthem were better off than some of the whites, as a groupthey were considered socially inferior to the whites.Status coincided, though not absolutely, with color.The small white group formed a reference group forthe mulatto and the Black bourgeoisie, who tried toemulate it in every imaginable way. They tried to speakimpeccable French, since it was the language of boththe white upper class and the metropolitan power. InMartinique, as indeed in all colonial countries, thecolonizer's language is associated with social class. InMartinique, the more impeccable one's French, thehigherwas one's status. And one was consideredhumanto the extent to which one mastered the language of the

master and approximated his manners and ways ofdoing things. One writer has commented on the magicpower of the white man's language on the island:Disembarking t Fort-de-France,he capitalof Martinique,a person having good French or English is whiskedthroughcustoms,whileCreole-speaking lacks aresearchedfor contraband oods.4

Victor Wolfenstein, writing about Gandhi, remarksabout a similar case:... Gandhihadtriedto be like the English n orderto be aman;he was unableto masterthe task and he revertedtohis mother's Hinduism, thereby arriving at a workableidentitywithhimself. (emphasisadded)5

This is perhaps the most pernicious aspect of colonialrule. To be human one has to be white.The whites, though less than one per cent of thepopulation, owned the large firms, the constructioncompanies, the newspapers and most of the port facili-ties. They controlled the social, economic, and politicallife of the island. They were an ingrown, clannishgroupand, like their counterpartsin other parts of the colonialworld, namely pre-independent Algeria or Kenya, ortoday's Rhodesia, they were hostile even to the whites

of the metropolis.The lower class Blacks who constituted the majorityof the population did mostly manual work. Manyworked in the fields as cane cutters, or on the bananaand pineapple plantations. Some also worked in thesugar refineries or as dock workers,truck drivers,ordomestic servants. Unlike the situation in other colonialareas, the non-white bourgeoisie of Martinique chosethe path of assimilation instead of national independence.BIRTH, FAMILY BACKGROUND, ANDEARLY EDUCATION

Into one of these bourgeois families of small propertyowners Frantz Fanon was born on July 20, 1925. Ofthe father we hardly know anything except that he wasa customs inspector and that he died in 1947, havingbeen born in 1891.6 His mother was described as amild-mannered and heavy-set woman, who consideredherself just another French citizen.7 The family wasdescribed as "conventional." They were integratedinto the Martinican society in spite of the fact that inconversations, the brotherstended to agreewith Frantz'sanalysis of European racism on the island.8 Fanon'selder brother worked with a French separatistorganiza-tion and for this reason he was exiled from the island.Fanon's father was described as a "free thinker" and"a freemason." In Catholic Martinique this providedthe atmosphere in which independent thought couldbe developed, at least in matters of religion.Of Fanon's pre-school life we know very little. Hewas the youngest of the four sons, and as a child wasquite restless and prone to getting into trouble. He wasalso the darkest of the eight children. Those who areattracted to psycho-history attach a great deal of im-portance to this.9 Among the speculations is thatFanon's preoccupation with recognition may haveoriginated from maternal rejection which he mighthave interpreted in racial terms. The significance ofcolour on the island is invoked to give weight to this.Preoccupation with recognition however is not a

26

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

4/13

TRANSITION46

peculiar trait with Fanon. It is found in varying degreesamong all colonial intellectuals. The tendency to inter-pret the drama of Fanon's life as an attempt to solve apersonal psychosis is to say the least shallow, and I findtotally unsatisfactorytheories which class all innovatorsas psychopaths.10Fanon's early education followed strictly along thelines laid down by French assimilationist policy. The

only books available were the official school textbooksconcentrating on the glories of the metropolitan powerand the French Empire. As in other French colonies,the official policy was assimilation, by which the Blacksor a chosen few of them, were promoted to the statusof French citizens, enjoying in theory all the privilegesof the white man's existence.Assimilation and French education were intertwined.Martinican children read the same books and took thesame examinations as white students in metropolitanFrance. Their classrooms were decorated with picturesof the wine harvest in Bordeaux and winter sports inGrenoble.11 They were taught the history of Franceas if it were their own history.12 Fanon and his brotherslearned French patriotic songs. French culture wasexalted to the skies; French language, French literature,French history, French mannerisms were accepted withuncritical adulation as the only legitimate way of life.The effect of this was clear. It made the childrendevelopa deep sense of personal identification with Frenchculture and the French way of life. Corresponding tothe exaltation of the Frenchway of life was a deprecationof the African way of life. Training at home was nodifferent. Fanon recounts that whenever he misbehavedhe was told to "stop acting like a nigger."13 The Mar-tinicans, like some members of the older generation ofBlack Americans accepted the racist stereotypes aboutAfricans. They did not regard themselves as Africans.They were Martinicans. The Africans lived in Africa.They spent evenings talking about the savage customsof the Africans in the same way as whites did. And ofthe Africans the Senegalese were held up as the worstof the Black savages. They were the real Africans ofwhom the most incredibletales were told.Looking back on these incidents of his personal life,Fanon writes:

As a schoolboy,I had on many occasions to spend wholehours talking about the supposed customs of the savageSenegalese.In what was said there was a lack of awarenessthat wasat the very eastparadoxical.Because heAntilleandoes not think of himself as a black man; he thinks ofhimselfas an Antillean.The Negro lives in Africa. Sub-jectively,ntellectually,he Antillean onducts imself ikea whiteman. (emphasisadded)14We would here add that Fanon was not talking of theordinarypoor Martinican, but the educated bourgeoisie.He was thus subjected to colonial education in one ofits most intensive forms. Thus, like most of the childrenof his age, his early trainingwas to end in his alienation.His education led to identification with French cultureand its values. It was not only identificationwith whiteFrenchculture but also a deprecationof African culture.Several years later Fanon was to write: "I am a whiteman for unconsciously I distrust what is black in me,that is the whole of my being."15 Little did he knowthat in France, no matter how much he approximatedto the French Europeanstyle of life, intellectual postureand achievements, he would still be regarded first and

foremost as a Black and differentfrom the white French-man. He would be known not simply as a "doctor"but as a "Black doctor", not simply a "student", buta "Black student", etc. Europe would never forget hiscolour.VICHY TIMES

In 1940, after the fall of France to the Vichy Adminis-tration, the French fleet in the Caribbean declared itsallegiance to the regime of Vichy. The United Statesimmediately imposed a blockade on the island. Inresponse, the French governor instituted a militarydictatorshipon the island with the supportof the leadingproperty owners.16 Consequently, 5,000 French sailorsdescended on the island's city population of 45,000 fora prolonged holiday. Geismar gives a vivid descriptionof the incident:The soldiers expropriatedFort-de-France'sbars, restau-rants, hotels, whorehouses, beaches, shops, sidewalks,taxisand betterapartments... The militarycouldaffordtoorder the civilians around. The servicemenwere roughtoo... Whatmoneyfailedto do brutepoweraccomplished.Cafes were immediately segregated: black waiters andwomen, white customers. In the stores sailors expectedto be served before Martinicans. At firstsegregationcameabout for economic reasons: With the influx of militarymoney prices went up and the islanders could no longerafford to be customers. By 1941 .. the colour lines werefirmlyestablished. The servicemenweren'tgoing to frater-nize with black males. The women were anothermatter:The white visitors requisitioned them; they consideredevery young girl on the island a prostitute. Rape oftenreplacedthe remunerationof those unwillingto conformto the soldiersexpectations. The police, used to operatingin a colonial environmentwhereblackswerealwaysin thewrong, dismissed rape victims as overpriced prostitutes.In the militarycourts,the navy'sworaalwayscarriedmoreweightthan the Martinican's omplaints. It was a totalita-rian racism.17

This was the condition of the island at the time of theVichy regime. Overnight the island came to look likean occupied territory. The regime came to represent"rape, racism and rioting."18 What effect did theseincidents have on the young and sensitive mind ofFanon ? Did Fanon begin to hate Fiance and all thatit stood for at this moment? Fanon was at this timebeginning to develop what one might call "politicalconsciousness." Like many other Blacks on the island,he resented the "totalitarian racism" of the Vichy Admi-nistration. Butat this time he did not link this to a ques-tioning of the whole French presence, nor did he linkracism with the colonial relationship. It was a resent-ment and hatred directedagainst the Administration andthe soldiers, and not the French as such. He identifiedthem more with the Germans than with the French.

Itwas in such circumstancesthat Fanon left the islandin 1943, halfway through his baccalaureate, in companyof two of hisclose friends,to respondto the call of Generalde Gaulleto saveFrance. Theirenthusiasmto fightfoi theFrench was underlined by the fact that they had to paytheir own fares to the Dominican Republic where theyunderwentmilitary training. By 1943, however, AdmiralGeorge Robert had capitulated to the pressure of theAmerican blockade and Fanon once more returnedto the island. However he did not obtain a dischargeafter the ouster of the Vichy Administration, butenlisted in the French Army and left for North Africato fight for the "Free French."27

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

5/13

TRANSITION6Fanon left the island in the company of two of hisclose friends-Mosole and Manville. Mosole was des-cribed as a cynic and a well-informed person, who by1943 knew all about racism and exploitation. Manvillewas the son of a Martinican socialist, who defendedBlacks in lower courts without any fee. Manville, whoseclose association with Fanon might have had some im-pact on him, attemptedto follow in his father's footsteps,and while at the lycee he was always taking up the casesof the defense of other students before the higher autho-

rities.19 Fanon, then grew up in the company of twoimportant catalysts: Mosole with a knowledge of racismand exploitation, and Manville with his emphasis on theneed for action on behalf of the helpless.After a short stay in southern Morocco, they arrivedin Algeria, which was to become Fanon's country ofadoption later on in life. While in Algeria, Fanon andhis two companions volunteered for service in Europe.The rampant racism in the army and the conditions ofpoverty were too much for them. He left the army withthe rank of a corporal in 1946 and he was cited forbravery.

THE FRENCH ARMYFanon's experiences in the French army and the warwere to have lasting effects on him. In the army he cameface to face with blatant racism. Admittedly the islandhad experiencedracism in some of its worst forms,parti-cularly during the time of the Vichy administration.This was resented by Fanon and all Blacks, but, as wehave said earlier, in the minds of the Martinicans, theVichy Administration was identified more with theGermans than with the French. The French were differ-ent. They held the values of fraternite, egalite andliberte. All through school, Fanon had been taught toregard himself as a Frenchman and he was quite un-preparedfor the treatmentwhich awaited him. He reali-zed that France reserved a different place for itsBlack Frenchmen. On the trip to North Africa the whiteFrench troops had attempted, to "requisition the'services'of a groupof femalevolunteers from Martiniqueand Guadeloupe."20 Fanon was deeply upset by thisincident, which raised further doubts in his own mindabout the natureof the realityof the Black-white relation-ship and the hypocrisy of the white world.Fanon also observed that Black troops were alwayssent to the worst areas of the war, and were quarteredin some of the most unhospitable areas. He did notfail to notice that white troops were treated differentlyand preferentially.The whites looked down on the Arabswho also looked down on the Blacks. And Blacks from

the Caribbean also looked down upon Blacks fromAfrica. The Martinicans, on account of their supposedcultural assimilation, were treated in minor ways aswhites, but in things which mattered were treated likethe rest of the non-whites.Manville reports how African troops were sent backand forth, to and from southern France. Their classifica-tion as Europeans or Africans depended on changes inclimatic conditions. The classification and assignmentof the soldiers to areas in France was apparently doneon the basis of the level of fluency in French and thedegree of acculturation. Thus, though Martinique was

in the tropical zone, its troops were sent, not to southernFrance where the climate was warm, but to northernFrance where the climate was cold, because that corres-ponded to their assimilated status! The white man, beingcivilized, lives in cold climates, so as the Black manapproximates the status of the white man through theprocess of assimilation, he is supposed to develop thesame resistance to cold and be able to respond to thephysical environment of the white world in the same wayas the white man! Correspondingly, the Africans, whowere supposed to be less culturally assimilated, weresent to southern France where the climate was warm,since that approximated to the level of their culturallyassimilated status. One is supposed to be civilized to theextent to which one finds the hot weather unbearable.Fanon comments on the sudden inability of the Martini-can to withstand the tiopical heat after a visit to Europe:

They need a minute to two in order to make their diagnosis.If the voyager tells his acquaintances 'I am so happy to beback with you Good Lord, it is hot in the country, I shallcertainly not be able to endure it very long,' they know:European has got off the ship.21Fanon was deeply angered by the record of Germandestruction of North Africa. He was also touched bythe poverty, famine and destitution in Algeria. Hisconcern about the conditions of poverty and destitutionamong the Algerians is even more remarkable if weremember that he was aware that Arabs looked downupon Blacks as social inferiors.

Some ten years ago I was astonished to learn that NorthAfricans despised men of colour. It was absolutely im-possible for me to make any contact with the local popula-tion.22His luck was to be better in the future. It is interestingto note that Fanon did not react to Arab racism in thesame way as he did to European racism. In a way hetended to think that Arab racism was part of the super-structure,a reflection of colonial racism occasioned bythe colonial experience. He viewed it in the same termsin which he viewed Martinican expression of racistattitudes towards Africans.In Europe too there were incidents which made himmore bitter against the French. In Toulon he had towatch white Frenchwomendancingwith Italian plisonersof war after turning down requests from Black service-men who, needless to say, had risked their lives to savethem (the Fiench) from the Italians and the Germans.By the end of the war, Fanon was becoming increa-singly cynical about France and the French values hehad been taught to admire at school.

RETURN TO MARTINIQUE-CESAIRE'SCAMPAIGNA short period of political activity was to intervenebetween Fanon's war years and his higher education.This was when he went back to the island after the warto campaign for Aime Cesaire, who was running on theCommunist ticket as a parliamentary delegate fromMartiniqueto the first National Assembly of the FourthRepublic. There is no evidence that Fanon was at thistime sympatheticto the Communist cause. He was moreinterested in the cultural nationalism of Cdsaireand hisnegritude philosophy at this time. His participationin the campaign activities of Aime C6saire was very

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

6/13

TRANSITION46instructive. His brother, Joby, alerted him to the pro-blems of political and social mobilization in a place likeMartiniqueand pointed out to him the flaws in Cesaire'scampaign in that he never succeeded in reaching thepeasants and the countryside.23 It is significant to notethat his brother,Joby felt that it was importantto involvethe peasants in the politics of the island.24 Fanon wasnot only to come to the same conclusion several yearslater but to make the peasantrythe cardinal point of hisrevolutionarydecolonisation.With the campaign over, Fanon went back to thelycee to complete his education. This was in 1946. Thepicture we have of Fanon at this time was that of anintrospective, withdrawn, and serious student. It ispossible to surmise that he was brooding and turningover in his mind his experiences in the French army.He turned his attention to the study of literature andphilosophy and he studied the works of Nietzsche, KarlJaspers, Kierkegaard, and Hegel. He was particularlyinterested in the works of Cesaire and Jean-Paul Sartre,and for a while he thought of a career in drama.HIGHER EDUCATION IN FRANCE

In 1947, after the death of his father, Fanon went toFrance for higher studies. He first enrolled in dentistryin Paris, but after three weeks introductory courses heabruptly left Paris for Lyon to study medicine,complaining that there were too many "niggers" inParis. Geismar gives as Fanon's reason that there weretoo many fools in dental school. He is also said tohave claimed that he could live more cheaply in Lyon.These reasons, however, are hardlysatisfactory,especial-ly when we know that Fanon has always had the ten-dency to withdraw from an intolerable psychologicalsituation. We have already noticed this "withdrawalsyndrome"when he was in the Army.25If the statement "There are just too many niggers in

Paris" is a referenceto the revulsion which Fanon feltat the disgusting behaviour of the Black bourgeoisiein Paris which tried to be more French than the French,and which tried to imitate and assimilate French culturein every imaginable way, then one can say that, even atthis early stage, he was keenly aware of the problemsof cultural and intellectual alienation which afflict theBlack man in a white-dominated world, a theme he wasto deal with so well in Black Skin, White Masks. If thisinterpretation is accepted, then how do we account forthe fact that with such a knowledge he did try to assimi-late French culture? The plain fact was that he had nochoice, eitherhe had to leave France or to stay in Franceand be assimilated. It could be argued that he soughtfull assimilation like anyone else, and to support thiscontention we may quote the following exclamation:Whatis all this talk of a blackpeople,of a Negro nationality? I am a Frenchman.I am interestedn French culture'French civilisation,the French people... I am personallyinterested n the futureof France,in Frenchvalues, in theFrench nation. What have I to do with a black empire.26It is quite conceivable that Fanon was plagued all thetime by an internal conflict between the demands ofassimilation and the need for autonomy, the need to beoneself and that sometimes he repressed one or theother. His abrupt flight from Paris could therefore beattributed to the constant reminder which the presenceof the Black bourgeoisie in Paris brought to him of his

internal conflict, something which he was trying des-perately to suppress.He thought Lyon wouldpiovide theconditions for psychic harmony. He was sadly mista-ken in this.After a year's preparatorywork in chemistry, physicsand biology, Fanon entered medical school. At schoolhe worked hard to earn the respectof his professors as abright student.While at the university, Fanon continued his interestin philosophy and literature. He read the existentialphilosophers: Husserl, Heidegger and Sartre. He alsoread Marx and Hegel, and he attended the course oflectures of Jean Lacroix and Maurice Merleau-Ponty.He was greatly influenced by Sartre, especially hisAnti-Semite and Jew and later by the Critique de laRaison Dialectique. According to Simone de Beauvoir,what impressed Fanon most about the Critique de laRaison Dialectique was Sartre's analysis of terror andbrotherhood.Fanon was also influenced by Aime Cesaire, an in-fluence which is particularly noticeable in Black Skin,WhiteMasks, with its numerous quotations from C6saire.While a medical student, he also immersed himselfin playwriting and he completed three works: Les MainsParalleles, L'Oeil Se Noie, La Conspiration.These werewrittenbetween 1949-1950.They still remain unpublishedand according to Fanon's widow, it was his wish thatthey remain so. Dr Marie Perimbam, who has readthem, says they reveal Fanon's attempt to solve humanproblems within the existential framework. They givethe impression that Fanon was thinking of the worldas a stage, life as an existential drama and people,as the actors. This was a period of intense reflectionintrospection and self-analysis. Some have called thisthe existentialist phase of Fanon's life. It should alsobe remembered that this was the time when he beganto compose the essays which later were to appear collec-tively as Black Skin, White Masks. It deals with theproblem of colonial alienation, the relations of super-ordination and subordination, the norm which guidesall relations between the colonizer and the colonized,and the creation of a dependency complex. In short it isan examination of the ontological existence of the Blackman in a white-dominated world and covers the subjectmatter of the psychology of colonial rule, a topic noto-riously neglected in college and university courses oncolonialism.Fanon was a restless student and side by side withhis medical studies, he was also active in politics. Whileat the medical school, he helped to orgrnize the Unionof Students from Overseas France in Lyon, and putout the short lived newspaper, Tam-Tam. He was

always involved in debates, or going to left-wing meet-ings and touring occupied factories.In November 1951, Fanon defended his medical thesisand left for Martinique. Much has been made of thefact that the thesis startswith a quotation from Nietzsche-"I dedicate myself to human beings, not to intro-spective mental process". But if a medical doctor doesnot dedicate himself to human beings to what else is heto dedicate himself? While in Martinique he presenteda copy of his thesis to his brother with the inscription:To my brother, Felix,I offer this work-

29

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

7/13

TRANSITION6The greatness of a man is to be found not in hisacts but in his style. Existence does not resemblea steadily rising curve, but a slow, and sometimessad, series of ups and downs.I have a horror of weaknesses-I understandthem, but I do not like them.I do not agree with those who think it possibleto live life at an easy pace. I don't want this.I don't think you do either.. .27

These remarkable lines bring out forcibly some aspectsof Fanon's personality: his restlessness, his impatience,his hatred of weakness and the apparentcontradictionsof his personal life. For it is puzzling that a man whoshowed a deep sense of commitment to praxis, shouldhere place style above acts.In the same year he went back to France to do hisresidency under Professor Francois Tosquelles, whowas carrying out innovative experiments in the field ofsociotherapy. He was to make a deep impression onFanon, who worked with Tosquelles for two yearsduring which time they jointly published a number ofresearch papers. His pioneering work in psychiatricmedicine in Algeria and Tunisia bore strongly theimpact of this association with Professor Tosquelles.In 1952, he married Josie Duble, a Frenchwomanwhom he had met while at the lycee in Lyon.28 CertainBlack radicals who have adopted Fanon have beenuneasy about the fact of his marriageto a white woman.They claim it was not right and goes against Fanon'sposition. This is a complete misunderstanding ofFanon's position. Fanon never preached separationor segregation. His writings about the Manichaeanworld are descriptiveand not prescriptive. It is preciselythis idea of the Black man being sealed in his blacknessand the white man being encased in his whiteness whichhe wanted to avoid. Specifically on the question ofmarriage he says: "... I do not feel that I should be

abandoning my personality by marrying an European,whoever she might be.'29 Admittedly, Fanon hascastigated the Black bourgeoisie for deciding to marrywhite. It should, however, be remembered that hisobjection was not to marriage across colour linesper se, but to marriage into the white society in orderto escape one's blackness. In this case it is an indicationof shame and hatred of one's colour. Geismar comesnear to suggesting that Fanon married a white womanbecause of the paucity of Black women in Lyon or as aconsequence of his yearning for "lactification".... it seemsthat Fanon fell in love only with white women.Maybethis was becausethere werefew blacksliving in thecity, but Fanon himself gave a more interesting possibleexplanationin his first book, Black Skin, White Masks.He describes there the neurotic behaviour pattern of ablack man attempting o becomewhite throughlove of awhite woman.30

Such a suggestion rests on a misunderstanding ofFanon. Fanon was not a man to marrya woman becauseshe is Black or white. This is precisely the Manichaeanworld he denounced in the most strident terms. InFanon's view, colour or nationality should be entirelyextraneous to the choice of a marital partner. Hiscommitmentwas neither to a black nor to awhite world.It was to a non-racial society. If Fanon avoided Blackwomen it was less on account of the colour question.It was the same reason which occasioned his abrupt

departurefrom Paris. Fanon has told us in Black Skin,White Masks of the kind of Blackwomen he encounteredin France:I know a greatnumberof girls from Martinique, tudentsin France, who admitted to me with complete candor-completely white candor-that they would find it im-possible to marryblack men. (Get out of that and thendeliberately o backto it? Thankyou, no.)31

Again,I knewanotherblackgirlwho kepta list of Parisiandance-halls 'where-there-.was-no-chance-of-running-intoiggers'.32

If these were the sort of Black women in France at thetime no psychological explanation is needed to accountfor Fanon's action. Any Black man with his head onhis shoulders would avoid such women.Although Geismar does not cite anything from thetext to support his claim of Fanon's marriage arisingout of lactification, his contention perhaps rests on thispassage:

I marry white culture, white beauty, white whiteness.When my restless hands caress those white breasts, theygraspwhitecivilizationand dignityand makethemmine.33Although Black Skin, White Masks is autobiographicalin tone, incidents related in the book do not alwaysrefer to incidents in Fanon's personal life. Sometimesit is only the style, not the incidents which are auto-biographical. The work is an attempt to understandthe world, and the Black man's place in it throughintrospection. The danger of using statements in BlackSkin, White Masks indiscriminatingly as incidents inFanon's personal life is evident from Geismar's work.Fanon, in Black Skin, WhiteMasks writes:

A prostituteonce told me that in her early days the merethoughtof goingto bed with a Negrobroughton an orgasm.She went in search of Negroes and neverasked them formoney. But, she added, 'going to bed with them was nomore remarkable than going to bed with white men.'34Although there is nothing in the text to indicate so,Geismar turns this into an incident in Fanon's personallife.

Not eventhe city'sprostituteswantedblackclients. Exceptfor one Fanonfound,whoconfided he wanted himbecausehe was black. She lateradmitted hatshehad had an orgasmthe first time before he had begun sexual intercourse.35Fanon has discussed in detail in Black Skin, WhiteMasks, buttressing his arguments with copious quota-tions from Mayotte Capecia's Je suis Martiniquaise,Abdoulaye Sadji's Nini, Rene Maran's Un hommepareil aux autres, the phenomenon of "lactification"by marriage to the white woman, or vice versa. It isunlikely that a man so keenly aware of these problemswhich he analyzes would himself become a victim.Also, we know that Black Skin, White Masks wascompleted in 1951, and publishedin 1952. His marriageto Josie Duble did not take place till 1952. Geismar'ssuggestions are thereforeextremelyunlikely.In France, Fanon was exposed to the writings andthe company of the French intellectual Left. He movedin the circles of Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. Hewas particularly friendly with Dr Colin, a leftist intel-lectual who edited a clandestine newspaper during theresistance. Fanon arrived in France when negritudewas still fashionable among a number of Black intellec-tuals in Paris. He was initially attracted to it and he

30

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

8/13

TRANSITION46reacted strongly against Sartre'scriticisms of negritude.Sartre, though regarding negritude as revolutionary,nevertheless described it as "anti-racist racism" andpointed out its limitations, indicating that it is only amovement in the dialectic. Fanon's reaction to Sartrewas swift and angry.

When read hatpage,I felt thatI hadbeenrobbedofmylast chance. I saidto myfriends,Thegenerationfyoungerblackpoetshavejust suffered blow that canneverbeforgiven.Helphadbeensoughtroma friendofthe coloured eoples, ndthat friendhad foundno betterresponsehan o pointouttherelativityf what heyweredoing.35AHe was later to recognise and acknowledge the samelimitations.

While in France, he also experienced and reactedagainst white racism, and the hypocrisy of the Frenchwith regardto their claims to be committed to universalethical values. In Martinique it was easy to rationalizeand interpret such behaviour as the aberration ofparticularEuropeans,and in the army one could alwaysargue that soldiers everywhere are coarse and rough,and do not typify the most decent and gentle of thenation. But when Fanon experienced the same thingsin France, and even from the Leftist intellectuals, hisreaction was no longer a matter of doubting Frenchvalues, but it was a rejection of France and all that itstood for. Relating some of his experiences, Fanonwrites:Whenpeopleikeme,they ellme t is in spiteofmycolor,When heydislikeme, theypointoutthat t is not becauseof my color. Eitherway,I am locked nto the infernalcircle.36

Frenchmen could never forget that he was black anddifferentfrom themselves.Colour always played a cen-tral role in everything. Again Fanon writes:Not so long ago, one of those good Frenchmensaid in atrain where I was sitting: 'Just let the real Frenchvirtueskeep going and the race is safe. Now more than ever,national union must be made a reality. Let'shave an endof internal strife. Let's face up to the foreigners hereheturned toward my corner) no matter who they are'.37

The Blacks were never to be part of the French nation,no matter what their assimilated status was. Theywere the foreignerswho had to be faced up to. He wastreated primarily as a Black man, not just as a humanbeing. Fanon writes:A man was expected o behave ike a man. I was expectedto behave like a black man-or at least like a nigger.38

Even in intellectualcircles Fanon was not safe from thishumiliation... more than a year ago in Lyon, I remember in a lectureI haddrawna parallelbetweenNegroand Europeanpoetry,and a French acquaintancetold me enthusiastically, Atbottom you are a white man.' The fact that I had beenable to investigateso interestinga problem through thewhiteman's language gave me honorary citizenship.39

Fanon was suspicious, and to his way of thinking theremark amounted to saying that for a Black man hisintellect was amazing. Incidents of this nature arousedhis indignation, anger and resentment and he hatedFrance and all that it stood for.Fanon was deeply affected by the hypocrisy of theFrench-even the Communist Left. He was also dis-gusted by the self-demeaning attitude of the Black

bourgeoisie who tried in every way to look as Frenchas possible. He was angered by the oppression of manby man, by the dehumanization of man, and by thefact that France was a living negation of the values itclaimed. As he was to say afterwards:When search or Man n thetechniquend thestyleofEurope,I see only a successionof negationsof man, andan avalanchef murders.40

Fanon was entirely disillusioned with Europe andFrance, and if he had one consuming desire at the timeit was to get away from it. No wonder that he was towrite later:Let us waste no time in sterile itaniesand nauseatingmimicry.Leave hisEuropewhereheyareneverdoneoftalkingaboutMan,yet murdermeneverywhereheyfindthem,at thecorner f everyoneof theirownstreets,n allcornersof the globe.41

It was no longer a question of appealing to Europe tolive up to its proclaimed values. That was useless. Hewanted to get to a place where he could search for hisown identity and think of a way where he could con-tribute to the saving of humanity. The burden now wasto be on the oppressed to do what Europe had beenunable to do. Fanon writes:"Letustryto createthe whole man,whom Europehasbeenincapableof bringing o triumphantbirth."42

He wanted a place where he could feel solidarity withthose who were contributing to the "victory of thedignity of the spirit," where man was saying "no" to"the attempt to subjugate his fellows." Algeria wasgodsent.ALGERIA

In 1953, Frantz Fanon passed the all-importantMedicat des Hopitaux Psychiatriques, and was offeredthe directorship of a Martinican hospital. However,he turned it down and took up a position as chef deservice in Algeria, after a short stay at Pontorson, asmall quiet town on the Atlantic coast of France.Geismar contends that his choice was motivated by aconsideration for his career, since Martinique lackedfacilities for psychiatric care on research. He uses thisto back up his claim that it was the Algerian situationwhich made Fanon a revolutionary,and that it was notfor political reasons that he went there. Renate Zahar,however, maintains that Fanon had decided at the timeof his marriage to Josie to work for a few years inAfrica and then return to Martinique.43 If we acceptZahar's account, then Geismar's position is somewhatweakened. If Fanon turned down the Martinicanposition because of his considerations for his career,i.e. lack of adequate equipment for the hospital, thenhow can we explain his plan to go back after a fewyears? There is no likelihood that in a few years theposition at the hospitalwould have changedconsiderably.One would think that if Fanon was all that concernedwith his career, Africa would be the least attractiveplace, if equipment for his work was very important tohim. Zahar'sclaim is supported by the fact that Geismarhimself admits that Fanon sought a position in Senegal,writing to Leopold Senghor, later to become Presidentof Senegal, but his letter was not answered. He badknown Senghor as one of the people connected with

31

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

9/13

TRANSITION 46the Society of African Culture and Presence Africaine.He wanted to leave France and go to Africa, which atthat time was in a state of nationalist ferment. Ghanawas making rapid advances towards self-governmentand Nigeria was following rapidly behind. In Centraland East Africa therewas political agitation. In Uganda,there was political agitation; in Kenya, politics wasbeginning to take a militant turn; Mau Mau had justbegun.

Fanon wanted to be in the center of things. Hewanted to be where the action was. We must not forgethis commitment to praxis. We must also not forgetthat Fanon as a schoolboy had heard a lot about theSenegalese, and it is quite conceivable that Senegal stillfascinated him and he wanted to go there himself.Reflecting on his boyhood Fanon, had this to say aboutthe Senegalese:All I knew about them was what I had heard from theveteransof the First World War: 'They attack with thebayonetand when that doesn'twork,theyjust punchtheirway through he machine-gunirewiththeir fists.44

If the above argumentis accepted, then it means thatFanon had a political motive for wanting to go toAfrica and his departurefor Algeria should be seen inthe same light. In sub-SaharanAfrica, due to languagedifficulty, he could only go to French-speakingAfrica;his attempt to go there was unsuccessful, so he went toNorth Africa. Here he would not have a languageproblem. Fanon had already shown some interest inNorth Africans in France by his essay "the NorthAfrican Syndrome"45in which he discusses the raciallydiscriminatory practices against the Arab minorityeven among doctors in France. Besides, in Algeria,politics was beginningto take a militant turn. Geismar'sposition is furtherweakened by his own admission thatBlida, where Fanon worked, did not have facilities forwork therapy.46 Why then should he want to go there?His argument that Fanon overcame his political phasetowards the end of his studies and set himself up to bea successful professional is unpersuasive. This inter-pretation tends to regard Fanon's political interests andhis commitment to praxis as the restless actions of anadolescent. He seems to think that Fanon was convertedto revolutionaryviolence due to the existential situationin Algeria. It is quite plausible that towards the end ofhis medical training, Fanon tried to concentrate moreon his studies, but that he was committed to revolu-tionary violence before his trip to Algeria is evidencedin Black Skin, WhiteMasks, where he writes:I do not carry innocence to the point of believing thatappealsto reasonor to respect or humandignitycan alterreality. For the Negro who works on a sugarplantationin Le Robert,thereis only one solution:to fight.47

This he wrote long before the trip to Algeria. Further-more, Fanon quotes Hegel with relish to substantiatehis contention for the necessityof revolutionary violencein the pursuit of freedom.It is solely by riskinglife that freedom is obtained; onlythus it is triedand provedthat the essentialnature of self-consciousness is not bare existence, is not the merelyimmediateform in which it at first makes its appearance,is not its mereabsorption n the expanseof life.48

Fanon continues in his own words:... Human realityin-itself-for-itself an be achieNedonly

throughconflictandthrough herisk thatconflict implies.49Again he quotes from Hegel:

The individualwho has not staked his life, may no doubtbe recognizedas a person,buthe has not attainedthe truthof this recognitionas an independent self-consciousness.50In Black Skin, WhiteMasks, Fanon advocates funda-mental change in society. Echoing Marx, he writes:

But whenone has takencognizanceof this situation,whenone has understoodit, one considersthe job completed.How can one then be deaf to that voice rollingdown thestagesof history:'Whatmatters s not to know the worldbut to change it.'51In another passage he writes:

In no way shouldmy color be regardedas a flaw. Fromthe moment the Negro acceptsthe separation imposedbytheEuropeanhe hasno furtherrespite,and 'is it not under-standablethat henceforthhe will try to elevate himselfto the white man's level? To elevatehimselfin the rangeof colors to which he attributesa kind of hierarchy?'We shallsee that anothersolutionis possible. It impliesa restructuringf the world.52

"Restructuring of the world" is the change of socialstructure and value systems. In another passage Fanonis even more explicit:Whatemerges hen is the need for combinedaction on theindividualand on the group. As a psychoanalyst,I shouldhelpmy patient o becomeconscious f his unconscious andabandon his attemptsat a hallucinatorywhitening, butalso to act in the directionof a changein the social struc-ture.53

It is clear from the above that at the time of the com-position of Black Skin, WhiteMasks, Fanon was alreadyconvinced of the need for a change in social structure.When this commitment to fundamentalchange of socialstructure is viewed in conjunction with Fanon's argu-ment for the necessity of violence to achieve freedom,it is difficultto avoid the conclusion that he was commit-ted to revolutionary violence for the purpose of achiev-ing freedom before he went to Algeria. His experiencesin Algeria confirmed a thesis he had already arrived atintellectually.We can say that before he went to Algeria,Fanon was intellectually committed to revolutionaryviolence, but due to his experiences in Algeria, hiscommitment took a personal and practical form.

Fanon arrivedin Algiers in November 1953. By thenthe revolution which was to engulf both France andAlgeria was beginning. There were isolated incidentsof terrorism which caused the French to isolate thecasbah from the European quarter, and to institutecheck points everywhere.Initially, Fanon collaborated with the Frontde Libera-tion Nationale. During the day he treated the Frenchtorturersand by night he treated the Algerian tortured.By 1956 this double life was becoming impossible.There was terror all around him; his nurseswere begin-ning to disappear, and he began to feel that he was be-coming less effective. In the circumstanceshe resigned.Fanon had also come to the view that in a colonialterritorylike Algeria, characterizedby economic oppres-sion, political violence, racism, torture, murder and

32

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

10/13

TRANSITION 46inhuman degradation, the psychiatric disorders fromwhich the people suffered were the direct result of thesocial situation; it was, thereforefutile to treat a patientand send him back to the same environment. What hadto be changed was not the people but the social andpolitical conditions prevailing in Algeria.

In Algeria, Fanon saw a confirmation of the thesishe had developed earlier as a result of his observationsin Martinique, namely that for the colonized the mostserious problem standing in the way of self-realizationand freedom was alienation. This alienation could onlybe cured by the destruction of the colonial system. Inhis letter of resignationhe states:If psychiatrys themedicalechniquehat aimsto enablemanno longero be a strangero hisenvironment,oweit to myself o affirmhat theArab,permanentlyn alieninhisowncountry,ives na stateof absolute epersonali-sation.... thefunction f socialstructures to setupinstitutionsto serveman'sneeds. A society hatdrives ts membersto desperateolutionss a non-viableociety,a society obereplaced.54

And to underline his own commitment for praxis, headds: "...there comes a time when silence becomes dis-honesty."After participating in a strike of doctors sympatheticto the FLN, Fanon was expelledfrom Algeria in January1957. Thus ended his short stay in Algeria.FANON IN TUNISIA

After Fanon's expulsion, he stayed in Lyon for a shorttime with Josie's family and then left for Tunisia towork for the FLN. He was now a "professional revo-lutionary." He now belonged entirely to the organisa-tion. The Algerian Revolution was his life. He assu-med whatever role the organization called upon himto perform. Whateveracademic and intellectual interestshe had were now only relevant to the extent to whichthey furtheredthe cause of the Revolution.While in Tunisia he worked as a member of theeditorial staff of El Moudjahid the FLN mouthpiece.Fanon turned it into a radical paper commenting onthe social economic and political aspects of the revolu-tion. He also published a number of articles on BlackAfrica and on African Unity.In spite of his new status as a professional revolu-tionary, he also taught at the university of Tunis andpractised medicine at a government psychiatrichospitalat Manouba, where he worked under the assumed nameof Dr Fares.Here Fanon did not get along very well with some ofhis colleagues. The doctors resentedhis innovations andregarded him as overbearing. He on the other handwas a perfectionist, and tried to impose on othersthe same dedication which he applied to his work.The resentmentagainst him from the doctors was suchthat they began to refer to him as "the Nigger." Thingsgot to such a pass that the head of the unit, Dr Soltantried to fire Fanon on the ground that he was a spyfor Israel, because he had earlier taken a stand againstanti-semitism.

Anti-Semitismits mehead-on:I amenraged, am bledwhiteby an appalling attle, amdeprivedf the possi-bilityof beinga man. I cannotdisassociatemyself romthe uturehat sproposedormybrother.55Fanon's singleness of purpose, his sincerity anddedication to the cause of freedom and justice, standout clearly when it is noticed that not even incidentsof this nature shook for a moment his total dedicationto the cause of Algerian freedom.It was while he was in Tunis that he published The5th Year of the Algerian Revolution. In some ways itbears a close resemblance to Marx's The EighteenthBrumaireof Louis Bonaparte.It is a sociological studyof the effects of the revolutionary war on Algeriansociety. It documents the changes which take place insocial structure, social and political institutions and inconsciousness as a result of the war of liberation. In away it should be seen as a sequel to Fanon's moreillustrious work The Wretched of the Earth, since itindicatesthe changeswhich would occur in the colonizedsociety if the recommendations contained in The Wret-ched of the Earth were put into effect. The importanceof the book for the liberation effort is evidenced by thefact that six months after its publication the Frenchgovernment ordered all copies seized and banned fur-therpublication.In Tunis Fanon seemed to have achieveda total fusionof the role of the intellectual and that of the politicalactivist. His life showed total dedication to the cause ofAlgerian liberation. In his writings, the reflective "I"which had characterized Black Skin, White Masksgave way to the committed "we," the Algerians.Another role which Fanon played in the FLN wasthat of a diplomatic representative.In December 1958,he attended the All-African People's Conference inAccra, where he met Kwame Nkrumah and other na-tionalist leaders, including Patrice Lumumba, FelixMoumie, head of Union Populairede Cameroun,(UPC)

Tom Mboya and Holden Roberto, who was to becomeleader of the Movimento Popular de Libertacao deAngola (MPLA). At the Conference he argued for thenecessity of violence for decolonization. In a report onthe Conference which he later wrote for El Moudjahid,he stated:The endof thecolonial egime ffected y peacefulmeansandmadepossible ythecolonialist'snderstandingightunder ertainircumstancesead oa renewedollaborationof the two nations. History,however, howsthat nocolonialistnation s willing o withdrawwithouthavingexhaustedllitspossibilitiesf maintainingtself.Raisingheproblemf a non-violentecolonizations lessthe postulationf a suddenhumanityn the partof thecolonialisthanbelievingn the sufficient ressure f thenewratioof forceson aninternationalcale.56

In March 1959, he attended the Second Congress ofBlack Writersin Rome, and there he spoke as a memberof the Antilles delegation. Fanon's internationalismwas beginning to appear. Though completely dedicatedto the Algerian cause, this did not inhibit him fromparticipation in the Antillean delegation. In January1960, he also participated in the Second Conference ofAfrican Peoples in Tunis as a member of the Algeriandelegation. He was seen as the man who could bridgethe gap between the predominantly Arab North Africa33

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

11/13

TRANSITION 46and the predominantly black sub-SaharaAfrica.Fanon's singular contribution to the cause of theAlgerian liberation at this time was to internationalizethe Algerian struggle. In his writings and presentationsat conferences he tried to project the Algerian strugglenot only as an Arab nationalist movement, but as partof the whole world movement for the liberation ofAfrica and the Third World.ACCRA

In March 1960, Fanon was appointed ambassadorfor the Algerian Provisional Government in Accra.In various other conferences which he attended-theInternational Conference for Peace and Security inAfrica, the Afro-Asian SolidarityConferencein Conakry,Guinea, and the Third Conference of IndependentAfrican States at Addis-Ababa in June 1960-he wentas the official representativeof Algeria. As an ambassa-dor in Accra he concentratedhis attention on three mainaspects of the African liberation struggle: the establish-ment of a southern flank in Mali through which recruitscould be channelled to fight in Algeria; the attempt torecruitvolunteers to fight in Algeria, the armed strugglein Angola and the events in the Congo.He spent much time travelling to present the case ofAlgerian liberation and to propagandize for the forma-tion of an African Legion for the fight for Africanliberation. Fanon's work in Accra was quite trying.His English was not fluent enough for him to be muchinvolved in the social life of the country. Even if hehad spoken very well, it is not likely that he would havegot on very well with the Ghanaian national bourgeoisiewhich was steeped in corruption, conspicuous consump-tion, authoritarianism and a shameless display ofaffluence in the midst of poverty, the very issues whichFanon was to denounce most vehemently in The Wret-ched of the Earth. In Accra, he did not do any medicalor psychiatricwork. His official position as an ambassa-dor would not allow him to do that.In 1961 Fanon unsuccessfullysought posting to Cuba.There have been a number of speculations about this.One opinion has it that he was seeking to return toMartinique and wanted to go to Cuba to study it as amodel. 57It is also claimed that he wanted to go to Cubaas an ambassador to compensate for an earlierwoundedpride in maternal rejection.58 Such an interpretationinvests Fanon with a vanity out of keeping with thedelineation of his character and personality. The morelikely reason was that Fanon was becoming intellec-tually and politically bored with Accra. True enoughAccra remained the headquartersof African liberationsouth of the Sahara, but behind the thin veil of politicalrhetoric there existed among the Ghanaian political

leadership residuary conservatism, ideological bank-ruptcy, political insensitivity, parochialism, incredibleignorance or tolerance of international capitalist machi-nations which any serious revolutionary like Fanonwould find most distressing.Looking around for a placeto escape from such a revolutionary graveyard, Cubaappearedmost attractive.ASSASSINATION ATTEMPTS

Fanon's importance to the Algerian movement andto the whole of the liberation forces in Africa is under-

lined by the numerous attempts to assassinate him.In 1959whilehe was travellingto a camp on the Algerian-Moroccan border his jeep was blown up. There are anumber of speculations about the incident. Some claimthat it was an accident, some that his car hit a land mineplanted either bythe French or someone within theranksof the FLN who wanted to do away with Fanon. Athird opinion is that there was a bomb planted in thecar in which he was travelling.The true story is shroudedin mystery. Fanon was flown from Tunis to Rome forspecialized treatment. In Rome there were two moreassassination attempts: one was when the car of theFLN representativewho was to pick him from the air-port was blown up and the second was when the ward inwhich he was supposed to be occupying was machine-gunned. Fanon had had a premonition and had secretlyrequested a change of rooms the same night. The factthat there was strong evidence linking these attacks withthe French Red Hand gives cause to think that it wasthe same group involved in the Algerian-Morocco borderincident.In 1960, there was another attempt to capture him.While an ambassador in Accra, he travelled frequentlyto various countries in West Africa trying to open thesouthernflank where arms and men could be channelled

to Algeria to aid the war effort. On one occasion he wasreturning to Conakry from Monrovia when there wasan attempt to capturehim. Geismar reports:... Fanon was nformedhathisscheduledlight o ConakryGuinea was filled. He would have to wait until the nextday to get an Air Franceflight o the samecity. His over-night expenseswould be paid by the airline. That eveningwhen a charming French airline hostess stopped at thehotel to tell himthat the planewould be two hours late thenextday,Fanonwassuspicious.It wasthekind of personalattentionhe had come to dread-especially after the 1959incidentin the Rome hospital. Revisingplans, he and anFLN colleague eft the Liberian apital by jeep and enteredGuinea through the dark forest surroundingthe bordertown of N'zerekore.

Air France still had Fanon, under the pseudonym of"Doctor Olnar," on its passengerlist for the next day.French intelligencehad arranged or the plane to changecourses from Guinea to the city of Abidjan, in the IvoryCoast... Despitethe fact that the final list didn't include"Omar" he aircraftwas searchedthoroughlyat Abidjanbeforeit was allowedto return o its normalflight plan.59

It is somethingof a mysterythat in spiteof all this, Fanoneluded his enemies.

ILLNESS AND DEATHLate in 1960, it was found that Fanon was sufferingfrom leukemia. He went to the Soviet Union for medical

treatment.The Russians advised him to go to the UnitedStates where the best center for the cure of leukemiawas the National Institute of Health in Bethesda, Mary-land. But he could not bringhimself to go to the "nationof lynchers."He refusedto allow the fact of his illness todampen his activity. The treatment he had in the SovietUnion gave him relief for some time. He returned toAccra and threw himself furiously into his work. Hebegan to plan projects as if nothing unusual existed.By May 1961, Fanon was working on the last chapterof The Wretchedof the Earth. As Geismar describes it,

34

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

12/13

TRANSITION46it was "a ten-week eruption of intellectual energies."After completing the drafts, he went to France to seeSartrewho had agreed to write the introduction.

Back in Tunis, Fanon had a relapse and his friendsarranged for him to go to the United States for treat-ment. Joseph Alsop, a syndicated columnist for theWashingtonPost, claimed that it was the CIA whicharranged for the transportation to Washington, andthat the CIA had an interest in Frantz Fanon. He wenton to mention the name of Ollie Iselin, a member of th-US diplomatic service, who was involved in the wholecase. The story that the CIA managedto get informationfrom the dying Fanon has been vigorously denied byboth his wife Josie and his brother Joby.There were some suspicious circumscances,however.Fanon was kept in Washington's Dupont Plaza foreight days before he was taken to the hospital, in spiteof the fact that there were vacant beds at the hospitalat this time. This raises the question of why he was nottaken immediately to the hospital, considering the sadcondition in whichhe was when he arrived n the country.Fanon refused to recognize his illness and while onhis death-bed he was still planning book projects. One

was to deal with the extent and functioning of the FLNorganization within metropolitan France; another, apsychological analysis of the death process itself, whichwas to be called Le Leucemiqueet son double. While hewas in the hospital he received a number of visitorsincluding Holden Roberto, and Alioune Diop, editorof Presence Africaine. Fanon had another relapse anddied on December 6, 1961, after reading the proofs ofThe Wretchedof the Earth, the work on which his repu-tation rests. In it he diagnoses the ills of Africa and theThird World. He argues that there has been no effectivedecolonization in Africa because the colonial structureshave not been destroyed. What happened at indepen-dence was the Africanization of colonialism. Therecan be no effective decolonization and consequentlyno freedom so long as the colonial structures obtain.And to destroy colonialism effectively violence is indis-pensable. Violence destroys not only the formal struc-tures of colonial rule, but also the alienated conscious-ness which colonial rule has planted in the mind of thenative. Unlike the so-called dispassionate native inte-llectuals, he is not content with a mere description ofthe structure of politics or a catalogue of colonial in-justices. He propounds a theory of social action andmakes a passionate plea for revolutionarydecolonizationand the creation of a free society in which man wouldacquire authentic existence. His vision of the idealsociety was that of a socialist populist democracy, acombination of Marx and Rousseau, in which man wouldbe free to maintain and express his nature. We maycriticise his vision or the means of its attainment, butwe neglect the issues he raises only at our peril.

After his death a collection of some of the editorialshe wrote for El Moudjahidand some of his presentationsat international conferences were published collectivelyas Towardsthe AfricanRevolution.*

The portrait which emerges from this is that FrantzFanon was a man of considerable courage, sincerity

and will power. He was a very sensitive person whodedicatedhis life to bringingaboutthe end of oppression.His whole life was devoted to the cause of humanfreedom. He was a man of keen intellect and revolu-tionary zeal. Simone de Beauvoir describedhis intellectas "razor sharp." He was one for whom the role of theintellectual and that of the political activist posed nocontradictions.Peter Worsely, in a vivid description of his encounter

with Fanon, gives us an insight into his qualities andpersonality:In 1960,I attendedhe All-African eople'sCongressnAccra, Ghana. The proceedings consisted mainly ofspeechesby leadersof African nationalismfrom all overthe continent,few of whom said anythingnotable. When,therefore, he representative f the Algerian RevolutionaryProvisional Government, their Ambassador in Ghana,stood up to speak I preparedmyself for an addressby adiplomat-not usually an experience to set the pulsesracing. I found myself electrifiedby a contributionthatwas remarkablenot only for its analytical power, butdelivered, oo, witha passionand brilliance hat is all toorare. I discovered hat the Ambassadorwas a man namedFrantzFanon. At one point duringhis talk he appearedalmost to break down. I asked him afterwardswhat hadhappened. He replied hathe had suddenly eltemotionallyovercomeat the thoughtthat he had to standthere,beforethe assembledrepresentatives f African nationalistmove-ments, to try and persuadethem that the Algeriancausewas important,at a time when men weredying ana beingtorturedin his country for a cause whosejusticeought tocommandautomaticsupport rom rationaland progressivehumanbeings.60

Like all revolutionaries Fanon was sometimes im-patient, brusque, and arrogant towards people whosecommitment never went beyond the talking stage. Healso tried to impose on others the same disciplinewhichhe imposed on himself, people who perhapsby tempera-ment and constitution were not fit for the arduous tasksto which he subjectedhimself.Aime Cesaire, in a tribute to Fanon, goes fartherthan anyone in delineating his character, qualities andpersonality. He writes:

If the word 'commitment'has any meaning, it was withFanon that it acquired significance. A violent one, theysaid. And it is true he instituted himself as a theorist ofviolence, the only arm of the colonized that can be usedagainstcolonialistbarbarity...But his violence, and this is not paradoxical,was thatof the non-violent. By this I mean the violenceof justice,of purity ana intransigence. This must be uncerstoodabout him: his revolt was ethical, and his endeavourgenerous. He did not simplyadhere to a cause. He gavehimselfto it. Completely,withoutreserve.Wholeheartedly.In him resided the absolutenessof passion...A theoristof violence,perhaps,but evenmore of action.By hatred of talkativeness. By hatred of compromise. Byhatred of cowardliness. No one was more respectfulofthoughtthan he, and more responsible n face of his ownthought, nor more exacting towards life, which he couldnot imagine in terms other than of thought transformedinto action.61

It is clear from the portrait above that simplisticinterpretations of Fanon as "apostle of violence,""glorifier of violence," "apologist for violence," "pri-soner of hate" should be rejected. Fanon was a greathumanist. It was in the name of man that he rose up35

-

7/27/2019 Fanon Portarit

13/13

TRANSITION 46against oppression; it was in the name of man that he We are nothingon earth f we arenot, first of all, slavesof a, a n di ws in cause,thecause of thepeople,the cause of justice,the causefought against degradation and it was in the name of of liberty.62man that he affirmed the dignity of man. If Fanon wasa prisoner, he was a prisoner of a cause, the cause of Che Guevara once said: "Let me say at the risk ofthe people, the cause of freedom. In a letter he wrote to seeming ridiculous that the true revolutionary is guidedRoger Tayed, one of his friends, just before he died, by great feelings of love." This we can say of Frantzhe said: Fanon. [

FOOTNOTES1. See Y. Kransin, The Dialectics of RevolutionaryProcess, (Moscow,Novosti Press Agency PublishingHouse, 1972.)2. For a detailed description of the life, politics and social structure ofMartinique, see Geismar, Fanon, (New York, Dial Press 1971).pp. 5-28:Arvin Murch, Black Frenchmen:The Political Integrationof the FrenchAntilles (Cambridge, Mass. SchenkmanPublishingCo., 1971); EmanuelDe Kadt, ed., Patterns of Foreign Influencein the Caribbean London,Oxford University Press, 1972), pp. 82-102.3. Edith Kovatz, Mariage et CohesionSociale Chez les BI ncs Creoles de laMartinique, (Unpublished M.A. thesis, University of Montreal, 1964)p. 49ff., quoted in Arvin Murch, p. 15.4. Peter Geismar, Fanonp. 205. Victor Wolfenstein, The RevolutionaryPersonality (Princeton, PrincetonUniversity Press, 1971),p. 208.6. Renate Zahar, L'oeuvrede Frantz Fanon (Paris, Maspero, 1970), p. 5.7. Geismar, p. 8.8. Ibid.p. 11.9. See IreneGendzier,FrantzFanon:A CriticalStudy(New York, Pantheon,1973),p. 10.

10. Lewis S. Feuer, Marx and the Intellectuals(New York, Anchor Books,1969)p. 51.11. Geismar, p. 15.12. Ibid.13. Black Skin, WhiteMasks, p. 191.14. Ibid., p. 148.15. Ibid., p. 191.16. Zahar,p. 5.17. Geismar, pp. 22-3.18. Ibid., p. 24.19. Ibid., p. 30.20. Ibid., p. 31.21. Black Skin, White Masks, p. 37. Incidents of this nature may appearimprobable to those unacquaintedwith colonial alienation. However inGhana, whereit is claimed that on account of the indirectrule, the nativesdid not suffer such cultural emasculation which gives rise to such mani-festations of alienation, it was not uncommon, especially in the fiftiesand early sixties for recent returnees from the white man's country tocomplain bitterly about the Feat. Press them closely and you will fndthey were away for only a couple of months and in most cases in thesummer.22. Ibid., p. 102.23. Geismar, p. 40.24. See Fanon, The Wretchedof the Earth(Penguin, 1967).25. This tendency to withdraw from an intolerable social situation seemsto have characterized Fanon all his life: When Martinique fell to theVichy forces he "withdrew" from the island by enlisting in the Frencharmy; while in North Africa, he "withdrew"by volunteeringfor servicein Europe; in Paris he "withdrew" to Lyon; in France he "withdrew"to Algeria; in Accra, he wantedto "withdraw"by asking for a diplomaticpost in Cuba. This shows his restlessness. For a man committed topraxis this is ratherdifficult to explain.26. Black Skin, WhiteMasks, p. 203.27. Geismar, p. 11.28. There have been some inconsistencies in the records about the date ofFanon's marriage. Irene Gendzier (p. 272) writes: "According to David

29.30.

Caute, Fanon(New York: Viking tress, 1970),p. 99, it occurredin 1953;Tosquelles in our interview recalled, but with some hesitation, that itwas in 1953; Geismar, on the other hand (Fanon, p. 52), states that itoccurred in 1952; Zahar in L'oeuvrede Frantz Fanon(Paris: FrancoisMaspero, 1970), p. 7, gives October 1952 as the date." To make theissue more complicated, Philip Lucas, Sociologiede Frantz Fanon(Alger,Societe Nationale d'Edition et Diffusion, 1971), p. 195, gives 1950as the date of the marriage. It is hoped that further research will throwmore light on thisBlack Skin, WhiteMasks, p. 202.Geismar, "Frantz Fanon: Evolution of a Revolutionary: A Biblio-graphical Sketch", Monthly Review, Vol. 21, No.l (May 1969), p. 24.

31. Black Skin, WhiteMasks, p. 48.32.33.34.

Ibid., p. 50.Ibid., p. 63Ibid., pp. 158-9

35. Geismar, p. 47.35A.36.37.38.39.40.41.4243.44.

Black Skin, WhiteMasks, p. 133.Black Skin, WhiteMasks, p. 116.Ibid., p. 121.Ibid., p. 114.Ibid., p. 38.The Wretchedof the Earth,p. 252.Ibid., p. 251.Ibid., 252.Zahar, p. 7.Black Skin, WhiteMasks, p. 162, fn.

45. Fanon, Towardsthe African Revolution,(New York, Grove Press 1968).46. Geismar, p 64.47. Black Skin, WhiteMasks, p. 224.48. Ibid., p. 218.49. Ibid.50. Ibid., p. 219.51. Ibid.,p. 17.52. Ibid., pp. 81-2.53. Ibid., p. 100.54. TowardTheAfricanRevolution,p. 53.55. Black Skin, WhiteMasks, pp. 88-9.56. Toward he AfricanRevolution,pp. 154-5.57. Geismar,p. 173.58. Gendzier, p. 16.59. Geismar, p. 163.60. Peter Worsley, "Revolutionary Theories" Monthly Review, op. cit.,pp. 30-1.61. PresenceAfricaine,Vol. 12, No.40, 1962pp. 131-13262. Quoted in Geismar, p. 185.

36