EXPORT INCENTIVE AND EFFECTIVE SUBSIDY IN PAKISTAN: AN EVALUATION

-

Upload

nurul-islam -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of EXPORT INCENTIVE AND EFFECTIVE SUBSIDY IN PAKISTAN: AN EVALUATION

EXPORT INCENTIVE AND EFFECTIVE SUBSIDY INPAKISTAN: AN EVALUATION

By NURUL ISLAM

INTRODUCTION

This article seeks to evaluate the effects and the efficiency of the existingsystem of export incentive schemes in Pakistan. In view of the widespreadprevalence of similar export incentive schemes in many parts of the developingworld, it is hoped that the analysis may provide a few lessons for the otherdeveloping countries.

Since the beginning of 1950's Pakistan superimposed a regime of quantitativerestrictions on imports over and above a system of import tariffs, which werecontinued, even though there was a devaluation of about 45 per cent in 1955,into the 1960's with varying degrees of intensity. Tariffs registered an upwardmovement throughout; the average rates of import duties on the various cate-gories of imports, which ranged between 23 per cent and 99 per cent during theperiod 1955-56-1959--60, increased and ranged between 17 per cent and 142 percent and between 34 per cent and 180 per cent in the years 1963-64 and 1965-66respectively. The scarcity margins on the imported goods i.e., the differencebetween the landed costs (inclusive of duties) and the domestic wholesale pricesof imports, an index of the restrictive impact of the quantitative controls onimports, varied between 7 per cent and 47 per cent during 1964-65 and between7 per cent and 52 per cent during 1965-66.' The implicit rate of exchange forimports, defined as the official rate of exchange, which has been Rs. 4.76 perdollar since 1955, multiplied by the percentage excess of the domestic prices ofimports over their CIF price (converted at the official rate) ranged from Rs. 7.78per dollar to Rs. 19.93 per dollar during 1963-64 and between Rs. 9.12 and Rs.22.69 during 1965-66.

While, on the one hand, the implicit rates for imports were on the increaseduring the 1950's as well as the 1960's, the implicit rates for exports started toincrease to any significant extent oiily during the sixties. The implicit rate ofexchange for exports is the total rupee receipts at the official rate per dollarworth of exports, reduced by the percentage rate of export taxation or increasedby the percentage of export subsidy provided directly or indirectly under variousexport incentive schemes. Towards the end of the 1950's and especially duringthe 1960's, Pakistan adopted a number of export incentive schemes such as theexport bonus scheme and the export performance licensing scheme and intro-duced a number of fiscal concessions for exports. Under the export bonusscheme, the exporters receive a fixed percentage of their exports in terms of the

'S. R. Lewis and S. E. Guisinger, Chapter on Pakistan in The Structure of Protection inDeveloping Countries, Edited by Bela Belassa, IBRD unpublished manuscript. P. S. Thomas,'Import Licensing and Import Liberalisation in Pakistan', Pakistan Development Review,Winter 1966 No. 4 Vol. VI, p. 532. M. Alamgir, 'The Domestic Prices of Imported Commoditiesin PakistanA further study,' The Pakistan Development Review, Spring 1968 Vol. VIII No. I.

B 169

170 BULLETIN

entitlements to imports, which are transferable and can be freely bought and soldfor the imports of a specified list of commodities. The export bonus scheme,which was introduced in 1959, excluded the major primary commodities such asjute, cotton, tea, hides and skins, and wool; the latter constituted in the earlysixties about 80 per cent of Pakistan's total export earnings. The rest of theprimary commodities, which in 1959 did not constitute more than 6 per cent ofthe total exports, and all the manufactured exports were entitled to receive theimport entitlements to the extent of 20 per cent and 40 per cent respectively oftheir export proceeds, with the exception of the jute manufacturing industrieswhich were eligible for the same rate of import entitlement as the minor primarycommodities, i.e., 20 per cent.'

Since 1962-63, an additional measure of export promotion in the form ofexport performance licensing has been in existence under which many exportindustries are entitled to receive import entitlements at varying percentages oftheir exports, as under the export bonus scheme. In contrast to those underthe bonus scheme, these entitlements can only be used for the imports of rawmaterials, spare parts, and machinery required by the industry concerned.2 Thesubsidy element in the export performance licensing arises from the fact thatthere is an excess demand and a consequent scarcity for most of the importedraw materials in the domestic market, especially in view of the widespread pre-valence of excess capacity in the manufacturing industries.3

During the mid-1950's i.e., after devaluation of 1955, the implicit rate forexports varied between 1s. 4.09 and Rs. 4.15 dollar, due to the export taxation,as against the official rate applied to the minor primary exports, with theexception of a few which were eligible for the very restricted export performancelicensing introduced during 1956-58 and hence were entitled to a rate of exchangeof about Rs. 5.12. However, the average implicit rates for major primaryexports improved to Rs. 4.62 per dollar between 1960-61 and 1966-67 with aprogressive reduction in the export duties; the minor primary commoditiesunder the export bonus scheme earned between Rs. 4.78 and Rs. 6.19 per dollar

1 In addition, some invisible items such as the earnings from shipping, ship and aircraftrepairs, and salvage operations were entitled to a bonus at the rate of 20 per cent. The hotelindustry and private remittances from abroad were subsequently included in the scheme, bothof these items being entitled to a 20 per cent bonus rate.

2 The differences as between the different industries, in terms of the extent of subsidyreceived by them, were thus related to scarcity of the imported inputs which were specific tothe industry concerned.

W. E. Hecox, 'The Use of Import Privileges as Incentives to Exporters in Pakistan'Research Report No. 30, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Karachi.

The imports may be used either for a larger domestic production destined for the domesticmarket or for outright sales at high profits to other similarly situated and suffering from excesscapacity. Moreover, a greater utilization of capacity is expected to reduce unit costs and thusto increase profits per unit of sale.

The additional import entitlement or export performance license received by the exportindustries in the initial years was substantially in excess of the import component of exports,especially since the import entitlements were at 100 per cent of the FOB value of export. Until1964 only 43 industries were eligible for the additional import entitlement, and the importentitlements were a uniform percentage of exports. In the subsequent the number of eligibleindustries has been expanded; they were 250 in 1965-66. At the same time, the percentage ofimport entitlements was reduced. Moreover, the import entitlements of each industry were tobe fixed separately in the light of its own import component, but in no case was it to exceed50 per cent of the FOB value of exports. Thus the degree of differentiation between commodi-ties increased and the rates of subsidy accruing to the different industries were widely different.

EXPORT INCENTIVE AND SUBSIDY IN PAKISTAN 171

depending upon (a) the varying percentage rates of bonus and (b) the rates ofpremium on the bonus vouchers in the different years. Insofar as the manu-factured exports were concerned, not more than 1-2 per cent of the exports ofmanufactures prior to 1959 were affected by the various import entitlementschemes in effect during the fifties.' The structure of import and export rates in1965-66, which are the combined result of export incentives, on the one hand,and the import substitution policies, on the other, is given in Table 1.

TABLa 1Implicit Exchange Rates for Coenmodity Exports and Imports'

(Rupees per dollar, 1955-56)Category of Percentage of Exchange Category of Percentage Exchange

Imports total imports rate exports of total rateexports

1 2 3 4 5 5

A. Licensed Imports 95% Major Exports 45% (a) 4.56-4.63(b) 4.76

Capital Goods 46% Rs. 8 Minor Primary 12% 4.78-6.90Exports

Raw Materials 25% Rs. 9-11 Jute and CottonManufactures 29% 5.90-7 À 7

Consumer Goods 24% Rs. 9-14 Miscellaneous 14% 6.47-9.52Manufactures

B. Bonus Imports 5% 3 very minor exports 11.04-12.11Capital Goods (Percentage Rs. 11.80

distribution ofRaw Materials Bonus Imports Rs. 14.50-17.11

is approxim-Consumer Goods ately the same Rs. 15.38-18.60

as licensedimports)

The export rates include the effects of all the export incentive schemes. The category(a) in primary exports consists of jute, tea and cotton which were subject to export taxes in1965-66 and (b) consists of wool and hides and skins which were exempt from export taxes in1965-66. The imports are overwhelmingly manufactured goods. N. Islam, Imports of Pakistan:Growth and Structure, A Statistical Study. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics,Karachi, 1967, pp. 27-31. Appendix B.

N. Islam, 'Export Policy in Pakistan', in Essays in Honour off. Tinbergen, North HollandPublishing Company, Amsterdam, 1968.

Comparing the export rates for manufactured goods, which are of primaryinterest in this paper, with the import rates, it appears that about 68 per cent olthe manufactured exports earn between Rs. 5.90 and Rs. 7.47 per dollar, arange which lies below the lowest rate paid by the manufactured imports.2About 49 per cent of the imports pay between Rs. 9 and Rs. 14 per dollar andabout 5 per cent pay between Rs. 12 and Rs. 19 per dollar. The highest rates formiscellaneous manufactured exports, constituting one-third of the total manu-factured exports, is Rs. 9.52 per dollar. Only three manufactured exports o]

1 Even though the exemption from the indirect taxes on the domestic intermediate inputsas well as the imported inputs was introduced as early as 1956, the procedures for exemptionwere not worked out satisfactorily and the administrative delays and complexities limitedtheir usefulness. It was only during the 1960's when the export drive became one of the maincomponents of commercial policy in Pakistan that the implementation of the measures of tasexemption was pursued vigorously. The exemption of exports from the domestic indirect taxeswas, however, in force during the mid-fifties. The rebate of income tax on exports was intro.duced only in 1963-64 and the export performance licensing in its generous form which isquantitatively the most important incentive, next to the export bonus scheme, was introducedas late as 1962-63.

2 29% of total exports, which are all manufactured, receive between Rs. 5.90 and Rs. 7.4per dollar; all manufactured exports constitute 43 per cent of total exports and hence thformer constitutes about 68 per cent of the manufactured exports.

172 BULLETIN

minor significance earn about Rs. 11-12 per dollar. A considerable increase in theimplicit import rates encouraged and speeded up the process of import substitu-tion in Pakistan during the 1950's. A rise in the implicit import rate without acorresponding rise in the implicit export rate involves a discouragement to theexpansion of exports. Firstly, it increases the relative returns from investmentand production in the import substituting industries compared to those in theexport promoting activities. Secondly, the costs of the inputs into the exportindustries, which are supplied by the import competing industries, go up as theyreplace the imported inputs by the high-cost domestically produced inputs.Thirdly, the cost of the imported inputs in the export industries also goes upinsofar as the restrictions and tariffs on the imports designed to encourage theimport substitution raise their domestic price. Fourthly, the import substitutingindustries, earning high profits in the protected domestic market, bid up suchfactor prices as urban wages above the opportunity cost of labour, thus raisingthe wage costs of the export industries. An import substitution policy whichdiscourages exports foregoes the advantages of economies of scale and of com-petition provided by a participation in and by an exposure to the world market.

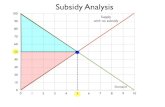

MEASUREMENT OF NOMINAL AND EFFECTIVE EXPORT SUBSIDYWhile the excess of the rate of exchange for imports over the rate of exchange

for exports does indicate a greater attractiveness of production for home marketas compared to production for export market, an appropriate measure of thedifferential incentives, in terms of the allocation of resources between importsubstitution and export expansion, is however, a comparison between the rate ofeffective export subsidy and that of effective protection. Just as the protectiveeffect of tariffs and quantitative restrictions is reduced by the imposition oftariffs and restrictions which raise the prices of inputs, so also the impact of theexport subsidy is reduced to the extent that the domestic prices of the importedinputs used in the export industry or the inputs supplied by the domestic industryfetch higher prices than their corresponding international prices. The magnitudeof subsidy to the export industry should thus be considered in terms of effectivesubsidy, i.e., subsidy received by 'the value added' in the export industry. Theoverall impact of the various export incentive schemes can be expressed in termsof a total amount of subsidy per unit of export i.e., as a percentage of the f.o.b.value of exports, which is thus defined here as nominal subsidy. The rate ofnominal subsidy can be derived as follows. The total receipts per unit of exportsale (R) isR=X (1 +bP +EP') +D(tm.m) +D(td.d) ±Dtwhere X=F.O.IB. export price,D ==domestic market pricetm==the rate of duty on the import component of the output (in domesticmarket price),m=import component of the output (in domestic market price),td=the rate of indirect taxes on the domestic inputs,d =the domestic input component per unit of output,t ==the indirect tax on output;

EXPORT INCENTIVE AND SUBSIDY IN PAKISTAN 173

P=prernium on the bonus vouchers,b =percentage of export bonus,E =percentage of export performance licensingP' =premium on export performance licensing.

Hence the export price which the exporter could quote if he were to equalisehis profits per unit of sale at home and abroad (R =D) would be

D(1tm . mtd. dt)X' 1+bP+EP'In practice he may not be able to sell abroad at that price, since the world pricewhich governs the actual export price (Lob. export price) may be less than X'so that X'>X. The nominal export subsidy as a proportion of f.o.b. export is,therefore,

1=Pb +EP' +[D(trn . m) +D(td. d) +tD]

vxvwThe effective export subsidy is defined as

where V =value added in the export market

1d =the value of the intermediate inputs (domestic and foreign) for exports;this is the same as the value of intermediate inputs in domestic prices, sincethe export subsidies which are given in the form of remissions and exemp-tions of taxes on the inputs (domestic and foreign) used in the exportindustry are already converted in terms of the total subsidy to the grossoutput as indicated earlier and therefore, are not treated again in order toavoid double counting.vw =xIwI =value of intermediate inputs in world prices.

The relationship between the nominal and effective export subsidy is analog-ous to the relationship between the nominal and effective protection as seenbelow. Thus the effective rate of protection is

vx

VdVw whereas the effective rate of export subsidy isVd

In the above derivation of the amount of export subsidy, the rebate on income tax onprofits or income from exports is not included. The percentage of rebate on income tax isrelated in a progressive manner to the percentage of output exported, i.e., a higher percentageof rebate is allowed with a higher proportion of export to the output. During 1963-67, theindustries which exported between 10 per cent and 20 per cent of its output were entitled to arebate of 10 per cent on the income tax payable on profit or income from exports; the rebatewas increased to 15 per cent in 1967. Those exporting above 30 per cent of output received themaximum rebate of 20 per cent which was raised to 25 per cent in 1967. Assuming profits on theexport sales to the extent of 25 per cent of the sales price, and income tax at an average rate of30 per cent, the subsidy works out between 0.7 per cent and 1.5 per cent of the fob, value ofexport during 1963-67, which increased to a value of 1.0 per cent and 1.8 per cent in 1967.

2 In cases where data on x were not directly available, they were indirectly derived asfollows:x D where D is the domestic wholesale price and P is the ratio of the domestic

P(1 + .05)wholesale price (including indirect taxes) to world price which is in most of the cases based onthe CIF prices of the competing imports. The CIF import price is assumed to be 5 per cent morethan the export price.

174 BULLETIN

VxVw.1Vx

If 'Vs, which is inclusive of export subsidies, equals Yd which includes the effectsof the import restrictions and tariff protection, effective subsidy is the same asthe effective protection. This would be the case if the receipts per unit of exports,including subsidies, (R) equal the receipts per unit of domestic sales (D). Yd isdifferent from V only insofar as the receipts per units of sale in the domesticmarket are different from the receipts per unit of sale (including export subsidies)in the export market, since the value of intermediate inputs in both cases is thesame.2 The available data on the differential between the international anddomestic prices suggest that the receipts, including export subsidies, per unit ofsale in the export market are in some cases less than what is obtained by sellingat home. In these cases, exports are not as profitable as domestic sales.

This paper estimates the magnitude and structure of the nominal andeffective export subsidy in Pakistan for the various categories of exports,especially manufactured exports, resulting from the multiple export incentiveschemes. It further seeks to examine their impact on the expansion of exportsand the degree to which they succeed in counteracting the relative attractivenessof the import substitution policy pursued since the 1950's. It evaluates theprevailing system of the multiple rates of effective export subsidy in terms of theefficiency of use of the domestic resources in the different sectors and industries.

The structure of nominal and effective export subsidy for the different manu-factured industries in Pakistan for the year 1963-64 is given in Table 2.

TABLE 2Nominal and Effective Export Subsidy for Manufacturing Industry

Percentage Distribution of Industries (unbrackcted) and Percentage of Value A dded (bracketed)Nominal Subsidy Effective Subsidy

1 In this paper V has been derived indirectly from Vd-V which is given in S. R. Lewis

and S. Guisinger, o. cit., and Vd is given in the input-output table of 1963-64.2 If V and V are always positive, then a positive V,-V always implies an effective

vxexport subsidy and a negative figures implies export taxation. However, when V and V arenegative the interpretation of V<-V with regard to its sign is no longer simple. If V is

Vxnegative, a positive figure implies an export taxation rather than export subsidy, whereas witha negative V, a negative figure implies an export subsidy rather than export taxation. How-ever, with a positive V, a positive figure implies subsidy and negative figures implies taxationof exports.

Rates of Subsidy

1963-64

Unadjusted non-Traded Inputs

1963-64

Non- Traded Inputsin Value Added

1963-64

(1) (2) (3)

0-25... ... ... ... 2 0 5(4.02) (3.84)

26-50 ... ... ... 60 12 35(77.83) (12.09) (20.19)

51-75 ... ... ... 38 36 40(16.85) (34.80) (47.15)

76-100... ... .. ... - 25 10(27.55) (0.01)

101-125... - 6 -- (6.08) -

Notes: The figures within brackets indicate the percentage contribution made by theindustries in each group to the 'value added' of the entire manufacturing sector in Pakistan, asgiven in the Input Output Table for the year 1963-64. The value added figures as given in theinput-output table have been adjusted to exclude two-thirds of the inputs from the servicesector to correct for the over-valuation of the service sector. (See S. R. Lewis and S. E.Guisnger, op. cil.). The value added proportions in the column 3, indicating the estimation ofeffective subsidy inclusive of the non-traded inputs in the value added, has been computedinclusive of non-traded inputs in the value added to maintain comparability. The percentagedistribution of the industries is based upon treating those industries, which receive exportperformance licensing, twice, since the effective as well as the nominal subsidies are calculatedfor those industries twice, once including the effects of export performance licensing and again,excluding the effects of export performance licensing. This method is adopted to overcome thedifficulty raised by the fact that export performance licensing relates to the specific products orbranches of various industries whereas the data on the other variables used for the estimationof effective subsidy relate to the major industries or groups of industries. The sum of theproportions of value added for each group does not add up to 100 since the estimation ofnominal subsidy does not cover all the industries for lack of data, a number of industries suchas cotton ginning, jute baling, salt and tea, etc., have been omitted as they are not treated asmanufactured exports for the purposes of the present study. The nominal subsidy in column(1) is calculated as RX i.e., the difference between total receipts including subsidy per unit of

Rexport and FOB export price (X) is expressed as a percentage of the former in order to make thenominal subsidy comparable in terms of method of calculation to effective subsidy whichexpresses the difference between value added in export market including subsidies (Vx) andthe value added in world prices, (Vw) as a percentage of value added in the export market, i.e.,VxVw.

VxThe estimates of the effective subsidy in Column (2) are based on the use of undeflated non-

traded inputs. In other words, the domestic value of the non-traded inputs, i.e., the inputsfrom construction, gas, electricity and all other services as recorded in the Pakistan input-output table of 1963-64 is assumed to be equal to their value in world prices. The use of unde-dated non-traded inputs tends to raise the rate of effective subsidy since the value added inworld prices is lower than otherwise it would be if the opportunity cost of the non-traded inputsis found to be below their domestic market value. The inclusion of non-traded inputs in thevalue added for the purpose of estimating the effective protection has been proposed on theground that they measure, in some sense, along with value added, the contribution of theeconomy to the value of the product and hence may be said to represent the domestic resourcecost of the activity engaged in import substitution or in export expansion. W. M. Corden, 'TheStructure of a Tariff System and the Effective Protective Rate', Journal of Political Economy,June 1966). Accordingly, in the column (3) effective subsidy has been calculated includingnon-traded inputs in value added. The appropriate treatment of the non-traded inputs in anyattempt to measure the value added in world prices of any economic activity is, however, notuniversally agreed upon. One measure of the social opportunity cost of the non-traded inputswould be to break down the components of the gross output of the non-traded sectors into (a)intermediate inputs from the other traded sectors, including imports which can then be evalu-

EXPORT INCENTIVE AND SUBSIDY IN PAKISTAN 175

126-150... 4(1.38) -

151-200.,. 2(2.08) -

200 and above...

6(2.75)

2(6.68)

Raies of TaxationO-25 .. 2- (0.52)

2(64.00)

26-50...51-75 ... 4- (2.52)76-100...

176 BULLETIN

ated in world price and (b) primary inputs or value added. It is the evaluation of the latter inworld prices, which poses the problem and an approximate method of solution may be toassume that the weighted average of the nominal protection to the traded products measuresthe excess of the value added in the non-traded products over their social opportunity cost.This is on the assumption that the excess of the opportunity cost is primarily due to theprotection granted to the traded sectors, which raises the profitability of the domestic produc-tion of the traded commodities and hence raises in turn the demand for non-traded inputsnecessary for the production of the traded commodities.

The effective subsidy was generally higher than the nominal subsidy and hada much wider distribution or a larger variance. In 1963-64, 60 per cent of theindustries, contributing about 78 per cent of the value added in the manufactur-ing sector, received between 26 and 50 per cent of the export price (includingsubsidy) as nominal subsidy and only about 38 per cent of the industries, con-tributing about 17 per cent of the value added of the manufacturing sector,received between 51 per cent and 75 per cent of the export price (includingsubsidy) as nominal subsidy. On the other hand, 36 per cent of the industries,contributing about 35 per cent of the value added of the manufacturing sectorreceived an effective subsidy varying between 51 per cent and 75 per cent;whereas 25 per cent of the industries, contributing about 28 per cent of the valueadded of the manufacturing sector, received subsidy between 76 per cent and100 per cent, and 18 per cent of the industries, contributing about 12 per cent ofthe value added, received subsidy above 100 per cent. A few industries, contri-buting only about 3 per cent of the total value added, received a subsidy of 200per cent and above. On the other hand, there were a number of industries,which, while receiving nominal subsidy, were subject to effective export taxationbut contributed only about 4 per cent to the value added of the manufacturingsector. The highest effective export subsidies were received by edible oils and fats(255 per cent), with negative value added in the export market, rubber manu-factures (123-219 per cent), matches (157 per cent), fertilizers (130 per cent), andmetal products (125 per cent).1 In. a few cases such as silk products, coal andpetroleum products, one variety of non-metallic mineral products and of electricalmachinery and plastic products, the effective subsidy was lower than nominalsubsidy. The rates of nominal and effective subsidy were not correlated. Therank correlation coefficient between the industries, ranked according to nominaland effective subsidy respectively, was small and statistically insignificant at the.05 level.

The level of effective subsidy declined in 1965-66. The percentage of indus-tries receiving effective subsidy of between 25 and 50 per cent increased to 29per cent in 1965-66 from 12 per cent in 1963-64; moreover, they contributed 25per cent of the value added of the manufacturing sector as against 12 per cent in1963-64. The percentage of industries with effective taxation increased to 12per cent but they did not contribute a larger percentage of value added in 1965--66 than in 1963-64.

When effective subsidy was estimated in terms of value added including non-traded inputs, the general level of effective subsidy declined; the vast majority ofthe industries received subsidy below 75 per cent and a large percentage ofindustries received subsidy between 26 per cent and 50 per cent. Moreover, a

'Appendix Table I.

EXPORT INCENTIVE AND SUBSIDY IN PAKISTAN 177

larger proportion of industries suffered from effective taxation. The general lackof correlation between the ranking of the industries by nominal and effectivesubsidy holds true.

IMPORT SUBSTITUTION AND EXPORT EXPANSION:RELATIVE ATTRACTIVENESS

The relative attractiveness of import substitution as against export expansioncan best be evaluated in terms of an industry-wide comparison of the effectiverates of protection and export subsidy for the year 1963-64 as given in thesummary Table 3 below.1 The industries which received approximately equaldegree of effective protection and effective export subsidy account, on an average,for about 42 per cent of the total manufactured exports during 1964-67. Theyinclude the second most important export industry, cotton textiles, and otherrelatively important export industries such as leather and leather goods, sportsgoods, paper and paper products, all of which together constitute 32 per cent ofthe total value added of the entire manufacturing sector.2 A few industries suchas footwear, matches, and rubber manufactures which accounted only for 6 percent of the value added and for about 4 per cent of exports during 1964-67received effective subsidy greater than effective protection. If total exportsexcluding cotton and jute textiles are considered, 84 per cent of the manu-factured exports earned an effective subsidy greater than 90 per cent of theeffective protection. The jute industry which supplied about 44 per cent of thetotal manufactured exports during 1964-67 received an effective protectiongreater than effective subsidy. This seems to indicate that the higher rate ofeffective protection has in this case provided high or abnormal profits to thejute industry which in addition is oligopolistically organized in the domesticmarket.

The industries which received effective subsidy either roughly equal to orgreater than effective protection expanded exports at a faster rate than thosewhich received effective subsidy less than the effective protection. Their contri-bution to total exports increased from 34 per cent during 1961-64 to 46 per centduring 1964-67. Their contribution to total exports excluding jute and cottontextiles, increased from 77 per cent to 84 per cent.

The above general conclusions remain unchanged if the effective subsidy isestimated inclusive of non-traded inputs in value added. Exports by the indus-tries receiving effective subsidy by this definition roughly equal to or greaterthan effective protection constituted 47 per cent of the total exports during1964-67 as against 34 per cent during 1961-64. They contributed 77 per cent ofthe total exports excluding the exports of jute and cotton textiles during 1961-64as against 92 per cent during 1964-67. Excluding jute and cotton textiles,

'The comparison is made in terms of the average export subsidy in the case of those indus-tries for which two rates of effective subsidy are computed. Two rates of subsidy for one industryare computed because one of the major export incentive schemes, i.e., export performancelicensing, relates only to specific products or branches of the industries on which relevant dataare available for the purposes of the present analysis. One rate of subsidy is computed for theindustry excluding the export performance licensing whereas another estimate is made on theassumption that the entire industry is entitled to the scheme. Detailed industrywise com-parisons are given in Appendix I.

2 Appendix.

178 BULLETiN

TABLE 3Relative Raies of Effective Protection and Subsidy

(Distribution of industries in ternis of their percentage contribution to total value added of manu-facturing sector and to total manufactured exports)

Percentage of Percentage of ExportsValue Added

1963-64A B

Effective Protection> Effective 46 16Subsidy

Effective Protection= Effective 32 32Subsidy ..

Effective Protection <EffectiveSubsidy ... ... .. 6 37 3 5 4 8

Inciudes undeflated non-traded inputs.Includes non-traded inputs in value added.

Noie: The columns do not add to 100 because industries such as cotton ginning, etc., arenot included in the list of industry for which effective subsidy and protection have beenestimated but they are included in the total value added for the manufacturing sector asa whole.roughly about equal proportions of industries in terms of their contribution to theexport earnings receive subsidy greater than and less than effective protection.The industries which received roughly equal percentage of effective subsidy andprotection judged by both the definitions of effective subsidy and protection(whether non-traded inputs are included in the value added or not) contributedbetween 60 and 70 per cent of these exports.

A pertinent question to explore is whether a commodity is exported if therate of effective protection exceeds effective subsidy, since this implies that thevalue of output in export prices (including subsidies) is less than the value ofoutput in domestic prices. It is conceivable that under certain circumstances theexporter does not equalize his profits per unit of sale in the domestic and exportmarkets so that exports take placeeven when the effective protection exceedsthe effective subsidy. Firstly, there is the possibility of price discriminationbetween the home and foreign markets, caused by the quantitive restrictionson trade; in view of the imperfections of competition in the domestic market, onthe one hand, and of Pakistan's small share in the world market, on the other,resulting in different elasticities of demand in the two markets, price discrimin-ation appears profitable in many cases.' Secondly, the manufacturers mayoperate on the basis of a conventional profit margin rather than maximise short-run profits; so that if the conventional profit margin is earned in the exportmarket, they are willing to export, even though the domestic market is moreprofitable. Moreover, a short-run maximization of profits may be moderated if apolicy of persuasion, exhortation and pressure, is pursued by the government toencourage the manufactures to enter the export market. Entry into exportmarket is one of the most effective ways of winning the favour of the government,which exercises considerable direct and indirect control over and commandssubstantial patronage in respect of the operation of the private enterprises. Theexport policy of the government has in recent years been buttressed by thecompulsory fixation of export quotas, non-fulfillment of which incurs the dis-pleasure of the government. Lastly, there are considerable differences in costs

M. Gilbert, Temporary National Committee, Monograph No. 6, p. 70, Par. 1, GovernmentPrinting Office, Washington, D.C., 1940.

Kindleberger, International Economics, Chapter 14, pp. 258-280, Richard D. Irwin, Inc.,1-Tomewood, Illinois, 1962.

1961-64 1964-67A B A B58 59 48 46

(jute 54) (Jute 54) (Jute 44) (Jute 44)31 29 42 39

(Cottonl7) (Cottonl7) (Cotton24) (Cotton24)

EXPORT INCENTIVE AND SUBSIDY IN PAKISTAN 179

and efficiency between the individual firms in an industry, so that for the moreefficient intra-marginal firms the difference between the world price and costs ismore than met by the magnitude of the export subsidy. These firms are able toforego some profits without making losses. It is usually the more efficient andthe larger firms which engàge in the export trade.

An important feature of the export policy has been a considerable fluctuationover time in the magnitude of export subsidy. The two most important com-ponents of the export policy, i.e., the export bonus scheme and export perform-ance licensing, have been frequently changed in terms of their coverage, per-centage of import entitlements and in terms of the permissible list of imports.The fluctuations in the magnitude and pattern of export subsidy, originatingfrom export bonus and performance licensing, are given below.

TAnLE 4Export Subsidy as Percentage of FOB Exports

Rates of Subsidy Percentage Distribution of Industries

As has been indicated earlier, by 1965-66 there was a decline in the effectiveexport subsidy but no decline in effective protection, judging from the differen-tials between domestic and foreign prices of imported goods and tariff rates;1the result was a diminution in the attraction for exporting as against importsubstituting. Assuming that the rates of effective protection of 1965-66 were thesame as in 1963-64, and comparing them with the effective rates of subsidy, onefinds that in the majority of the cases the effective protection exceeded effectivesubsidy; moreover, the magnitude of the difference between the two corres-pondingly widened.

The rationale of the reduction of the export incentive scheme and corres-ponding reduction in the effective export subsidy is complicated. The exportsubsidization policy after 1963-64 became more discriminatory as betweendifferent commodities, since there was a reduction in the magnitude of the lessdiscriminatory of the two principal measures, i.e., the export bonus scheme, anda widening of the coverage, without raising the rate, of the more discriminatoryexport performance licensing. It was not clear whether the export bonus schemewas conceived by the authorities less as a device for the correction of the over-valuation of the exchange rate for export, given the depreciation of the effectiveimport rate owing to the tariffs and quantitative restrictions on imports, andmore as a temporary measure of assistance to the infant manufacturing industriesin Pakistan. More often than not it was conceived as a temporary measure ofassistance for infant industries; it was, frequently, argued that the cost dis-advantage if not to be entirely offset by an adjustment of the exchange rate forexports via an export subsidy: it should be partly offset by a reduction in costs.

1 M. Alamgir, op. cit.

1963-64 1965-66 1967-680 24... ... .. 1.78 1.61 3.23

25 50... ... 5.36 62.91 62.9051 75... ... ... 58.93 35.48 33.8776-100... ... 5.36 - -

101-125... ... 28.57 - -126-150... ... ... - - *151-200,.. ... ... - - -200 and above

180 BULLETIN

lt was expected that with a gradual improvement in efficiency and/or a reductionin input prices, coupled with a temporary, moderate measure of export subsidy,the economy would grow into the official exchange rate over time.

It was not clear whether a lower exchange rate was to be associated with anincreased effort at lowering costs, and if so, how. If, on the one hand, the effectiveexport subsidy at a lower rate than the effective protection was adequate toensure the competitiveness of the manufactured exports in the world market,the higher effective rate of protection was redundant and it resulted only in highrents or profits for the manufacturing sector. So long as a higher effective rateof protection restricts markets and contributes to monopoly profits, the expectedimprovement of efficiency of the manufacturing industries from an increasedparticipation in the export market tends to be thwarted. However, there havebeen subsequent increases in export subsidy in 1967-68 (following the devalua-tion of stirling) owing to changes in the export bonus scheme involving a rise inthe percentage bonus and in the premium on the bonus vouchers. But at thesame time there has also been a rise in the tariff rates and an enlargement of thebonus import list, both of which have the effect of raising the degree of nominalprotection. Given the close positive correlation between the nominal and theeffective protection, as evidenced in a recent study, there has presumably beenan increase in the degree of effective protection, along with an increase in effectiveexport subsidy.1

MULTIPLE EFFECTIVE RATES, EFFICIENCY CRITERIAAND EXPORT EARNINGS

What has been the rationale for the differentiation between commodities interms of nominal and effective rates of export subsidy? Firstly there is dis-crimination between the agricultural and the manufacturing sectors and secondlythere is discrimination between individual commodities in each group. The mostmajor agricultural exports suffer from effective export taxation. Discriminationbetween different commodities is usually sought to be justified with reference todifferential elasticities of demand and supply. In addition, a higher rate isjustified for those industries which suffer from high costs of infancy and whichare expected to reduce costs over time by 'learning by doing'. When an infantindustry faces a more elastic export demand curve, the case for a higher exchangerate is reinforced. The lower rate of exchange for agricultural commodities issought to be justified with reference to their relatively low supply and demandelasticity. However, excepting raw jute, of which Pakistan supplies a majorshare of the world market, the elasticity of export demand for most of the othercommodities is likely to be high in view of Pakistan's small share in world trade.Even the assumption of low elasticity of demand for raw jute needs reconsider-ation if the new synthetic substitutes such as polypropylene as well as the entryin the world market of the potential marginal producers like Thailand, Brazil andAfrican countries is taken into account. Reliable empirical evidence on the

'S. R. Lewis and S. E. Guisinger, o. cit.

EXPORT INCENTIVE AND SUBSIDY IN PAKISTAN 181

differential demand elasticities for exports is difficult to come by.1The presumption that, in view of Pakistan's small share in the world market

for the manufactured exports, the elasticity of export demand is likely to behigh, needs to be qualified since international trade in many manufactured goodsis imperfect in the presence of product differentiation and of marketing costsinvolved in breaking the barrier of consumer's preference for the establishedproducts.2 However, Pakistan's miscellaneous manufactured exports suffer frompoor quality and lack of standardization; furthermore, the selling efforts andnon-price factors involved in entering the new markets with whom the traditionaltrade links have been relatively undeveloped play a crucial role in export sales.This tends to reduce the price elasticity of demand. It appears doubtful in thelight of the factors considered above whether the considerable degree of dis-crimination between the major agricultural exports, on the one hand, and themanufactured exports, on the other is justified only on the grounds of thedifferential demand elasticities. The reductions in export taxes and the inclusionof wool under the export bonus scheme during 1967-8 constitute a belatedrecognition of the validity of this argument.3

Given the differences in the demand elasticities for exports, the appropriaterate of exchange for the different exports, with a view to maximizing real incomeor net foreign exchange earnings (net of domestic resource cost) would depend onthe differences in supply elasticities. Thus if the supply of agricultural exports ishighly inelastic compared to that of manufactured exports, other things remain-ing the same, a higher exchange rate is called for the latter. While the aggregatesupply elasticity of the agricultural sector may be low, the supply elasticity of the

1 Some fragmentary evidence on the demand elasticity for agricultural exports is givenbelow. The elasticity of export demand for raw cotton in the US market is estimated at 14.5whereas that of the Pakistani skin in the same market is estimated at 2.3 during 1955-64. Theexport demand elasticity for fine rice is estimated at 3.14. However, fine rice is a highlydifferentiated product and its sales are limited to Middle Eastern markets. These are estimatesof elasticity in particular export markets or regional markets, which import considerablequantities of Pakistan's exports. However, if the world market as a whole is considered,elasticity is likely to be higher.

N. Alam. The Experience of an Overvalued Currency: The Pakistan Case. UnpublishedDissertation. Yale University 1968, pp. 170-180.

M. Hussain, 'Export Potential of Fine Rice from Pakistan', The Pakistan DevelopmentReview, No. 4, Vol. IV, Winter 1964, p. 679.

2A. C. Harberger, 'Some Evidence on International Price Mechanism', The Journal ofPolitical Economy, December 1957, pp. 506-522.

Y. Shinkai, 'Price Elasticity of the Japanese Exports: A Gross Section Study', The Reviewof Economics and Statistics, June 1968, pp. 268-273 M. E. Kreinin, 'Price Elasticities in Inter-national Trade', Review of Economics and Statistics, November 1967, pp. 510-516.

A few studies of demand elasticity for the manufactured exports of the developed countriestend to indicate that the elasticity of demand for the textile products is smaller than that forother products such as chemicals, basic metals, metal products, and machinery, etc., eventhough there are differences within each group, with a few items having a very low elasticity.

A recent estimate of the elasticity of substitution between the Pakistan and Indian jutebags in the United Kingdom markets puts it at 13.24 and that between Pakistani and thecompeting cotton fabrics in the US market at 6.38. The elasticities of export demand, on theother hand, are respectively 11.0 and 5.0; Pakistani's share in the UK and the US marketsfor these two products is about 88 per cent. S. N. Alam, op. cit.

Export tax on a raw material like raw cotton in conjunction with export bonus on theexports of cotton textiles has also been sought to be justified with a view to increasing therelative proportion of exports of the cotton textiles. This is related to the general argument forindustrialization and diversification such as the expansion of employment opportunities, thegeneration of 'external economies', not otherwise available through an expansion of cottonexports, and the possibility of a higher rate of capital accumulation in the manufacturingsector.

182 BULLETIN

individual export crops is high because of the high degree of substitution inproduction between the different export crops as well as between the agriculturalraw material exports, on one hand, and food crops, which are intended primarilyfor the domestic market, on the other. If the aggregate agricultural supply isinelastic, a high exchange rate for raw material exports may tend to divertresources from the production of food to the raw material export sector; highrents and high prices will be earned by the food producers which may result in arise in the urban money wages and hence in the costs of production of the manu-facturing sector. In these circumstances an exchange rate for the agriculturalexport sector lower than that for the manufacturing sector may be in order.Moreover, a higher rate for the manufactured exports can also be justified on thebasis of infant industry argument hut this is intended to be temporary. Thus acertain degree of discrimination in terms of effective exchange rate betweenagriculture and the manufacturing sector in Pakistan is justified on the abovegrounds; but the present degree of effective taxation of the exports of theagricultural raw materials may discourage production, especially since theintroduction of new technology in food production, mainly in terms of the highyielding seeds, and favourable price incentives encouraged by a system ofsubsidies, reduces the relative profitability of export crops. An improvement inthe exchange rate for the maj or agricultural raw material exports appearsnecessary to meet the increase in their opportunity costs.

The wide discrimination between the individual manufactured exports,ranging from high effective subsidy to high effective taxation seems to beunrelated to any plausible range of diffences between them in terms of elasticityof demand or of infancy. While higher rate for the newer manufacturers as awhole (excluding jute and cotton textiles), in consideration of their relativeinfancy in production and export marketing, may be warranted for a temporaryperiod, the extent to which they should be higher is critically dependent upon(a) the extent of competition from synthetic substitutes and (b) costs of entryinto new and unfamiliar markets. But a considerable degree of discrimination asbetween the individual newer manufacturers, as is the case now, is difficult tojustify in view of an inadequate knowledge about the differential elasticities andinfancies of the individual industries; in fact the present system runs the risk ofproviding a higher exchange rate and higher nominal subsidies to the higher costindustries or industries having greater difficulty in their sales effort in the exportmarkets. It is noteworthy that in view of a lack of close correspondence betweenthe rates of nominal and effective subsidy, the discrimination in terms of nominalsubsidy does not result in discrimination in terms of effective subsidy, either inthe desired direction or degree. While nominal subsidies for the textiles productsin general are lower than those for the newer manufactures, many newer manu-factures have lower effective subsidies and in some cases even negative effectivesubsidy, which is contrary to the assumption of the higher demand and supplyelasticities as well as the greater infancy of the newer manufactures.

One way of judging the efficiency of the differential structure of exportincentives is to relate the rates of effective subsidy to the marginal cost of earningadditional foreign exchange from the individual manufactured exports. Since

EXPORT INCENTIVE AND SUBSIDY IN PAKISTAN 183

on the basis of the available data, it has not been possible to estimate the domesticmarginal cost of the additional foreign exchange earning, a few alternativeestimates of the average domestic cost of average foreign exchange earnings havebeen made. Whichever index of the average domestic resource cost is used, therates of effective subsidy for different industries are unrelated to their domesticcosts of earning foreign exchange.1 The absence of any significant correlationbetween the average domestic costs of earning foreign exchange and the structureof effective subsidies tends to confirm that the differential structure of effectivesubsidies is not designed to minimize average costs of earning foreign exchangeby granting higher subsidies to the lower cost exports.

How have the exports responded to the export subsidies? The manufacturedexports of all kinds received subsidies and expanded rapidly during the 1960's.Between 1957-58 and 1966-67 among the various exports enjoying exportsubsidies, the minor agricultural exports increased annually at a compound rateof 15 per cent, the jute and cotton textiles expanded at 22 per cent and the minormanufactured exports at 38 per cent. The high rates of growth of the minorexports, both agricultural and manufactured, are partly statistical phenomenon,since the value of these exports was very small in the late 1950's. The growth ofcotton and jute textiles has been partly at the expense of the exports of rawcotton and raw jute. The growth in the exports of tanned leather and leathergoods has been partly at the expense of hides and skins. The average net foreignexchange earnings of the four major manufactured exports, i.e., FOB exportvalue minus the import component and exportable domestic raw materialsincorporated in the manufactured exports, as a percentage of FOB export value,are as follows: jute textiles, 27 per cent; cotton textiles, 26 per cent; woollentextiles, 30 per cent; and leather and leather goods, 20 per cent, as of 1963_64.2

In the present context the more pertinent question is whether the differentialperformance of the individual exports is related to the magnitude of the differ-ential incentives. The rates of growth of individual manufactured exports

1 The alternative estimates of domestic costs are (1) direct domestic resource cost, i.e.(D+\T

, (2) direct and indirect domestic resource cost, j e,( U and (3) direct and in-X-MIdirect wage cost, i.e., I __Y_ and (4)(X. D is the domestic intermediate inputs and V is the

'1X-MIvalue added in domestic prices, excluding indirect taxes on output; X is the FOB export value,m is the direct import component, excluding indirect taxes on imports, U is the direct and in-direct value added per unit of output excluding indirect taxes, W is the direct and indirect wagecosts per unit of output, M is the direct and indirect import component, excluding indirect taxeson import components, Vd is the direct value added in domestic prices and Vw is value added inworld prices. If it is assumed that the domestic intermediate inputs in a given activity can beeither exported directly or be used in other export or import substituting activity, then theopportunity cost of domestically traded inputs is the value of the intermediate inputs in worldprices and hence the net foreign exchange earnings will exclude not only import componentshut also the value of domestic inputs in world prices. The relevant domestic costs would be thevalue added in domestic prices. If the costs of the intermediate inputs in domestic prices areincluded in the domestic costs, the relative inefficiency of the supplying industries is reflectedin the costs of earning or saving foreign exchange by the specific activity or industry in question.The last measure of cost, i.e., 1Y, is derived from the effective protection which is (l_YY). The

V11

Vd V.ranking of Industries by -- or (1-- is the same.'w Vd

N. Islam, 'Commodity Exports Net Exchange Earnings and Investment Criteria' PakisfaDevelopment Review, Winter 1968.

184 BULLETIN

during 1960-67 are not related to the differential export subsidies, either nominalor effective, judged by the rank correlation between them. The relative import-ance of the different exports, i.e., the average ratio of the individual exports tothe total manufactured exports during 1960-61--1963-64 or during 1964-65--1966-67, is not correlated with the rates of effective subsidy of 1963-64 or of1965-66. Moreover, there is a very poor correlation between the rate of effectivesubsidy and the proportion of export to the output of each industry. This istrue of both the estimates of the rate of effective subsidy and for both the years,i.e., 1963-64 and 1965-66. Undoubtedly the relative performance of the individ-ual exports is also a function of changes in the supply and demand situation bothat home and abroad, so that the isolation of the influence of other factors isnecessary in assessing the effect of differential export subsidies on the differentialperformance of exports. However, as pointed out earlier, the major proportionof the total manufactured exports (excluding jute and cotton textiles) wascontributed by those items which received effective subsidy greater than orroughly equal to the effective protection implying that in these cases the attrac-tion of production for the domestic market was offset by the export incentives.But the differences in the export performance as between individual items asmeasured by the rates of growth of the individual exports or by the proportionof the total manufactured exports constituted by each individual item is notdirectly in proportion to the relative magnitude of effective subsidy vis-a-viseffective protection.

CONCLUSIONS

Pakistan adopted since the early 1960's a large number of export promotionmeasures which constituted a substantial amount of nominal and effective exportsubsidy to the manufactured exports and to a very few minor agricultural exports.The major agricultural exports were subject to effective taxation, though to adecreasing degree over time. The effective export subsidy was generally higherthan the nominal subsidy and had a much larger variance indicating a consider-able degree of discrimination between the individual commodities and industries.There were a few items which received effective subsidy less than nominalsubsidy; in fact, a few manufactured exports items were effectively taxed. Thenominal and effective subsidy were unrelated, in contrast to nominal and effectiveprotection which were highly correlated. Effective subsidy did offset or nearlyoffset the effective protection in the majority of the cases, thus counterbalancingthe relative attractiveness of production for the domestic market, created by thehigh effective protection throughout the fifties. However, the reduction ofexport subsidy in the years following 1963-64 again increased the relativeattractiveness of the domestic market. The magnitude of nominal and henceeffective subsidy has been subject to frequent changes. The dual role of multipleexchange rates in offsetting the overvaluation of the exchange rate, as evidencedby the high and rising exchange rates for imports, and in providing assistance tothe nascent infant industries in their efforts to compete in the export markets,was not often clearly distinguished.

EXPORT INCENTIVE AND SUBSIDY IN PAKISTAN 185

The discrimination between the individual manufactured exports in terms ofeffective export subsidy does not appear to be related to or justified by anyplausible range of variation in the elasticities of and demand or in the relativedegree of infancy of the different industries. The rates of effective subsidy arenot related to the domestic cost of earning foreign exchange, conceived in termsof average costs and average earnings. While a lower rate for agriculturalexports is justified, the present high degree of discrimination between the agri-cultural and manufactured exports needs to be reduced by raising the effectivesubsidy for the former. Exports have expanded considerably during the 1960'sbut the differential rates of growth are not related to the differential exportincentives. In other words, the manufactured exports in the aggregate haveexpanded in response to export incentive schemes at a rate higher than thegrowth in world trade in manufactures, but not in any direct proportion to thedifferential export incentives.1 While a once and for all upward adjustment ofthe exchange rate will reduce the administrative burden as well as the oppor-tunities and the inducements for evasion, it may be argued that in the presentcircumstances with a complicated structure of effective export and import rates,it will be difficult to determine the appropriate amount of devaluation which canreplace the existing structure of multiple rates. The generalization of the exportbonus scheme, the least discriminatory of the existing export incentive schemes,to include all imports and exports, provides a readily available mechanism forintroducing a flexible exchange market; the resultant rate of exchange whichemerges out of the operation of the bonus market will provide a guide to anappropriate degree of once and for all official adjustment of the exchange in thefuture. Discrimination between agricultural and manufactured exports, thoughat a much reduced scale can be accomplished by taxes.

Even if there is one exchange rate for the agricultural exports and one for themanufactured exports, the effective rates of subsidy on export will be differentfor the different manufactures, depending upon the relative inputs of the agri-cultural and manufactured sectors in the production. Under these circumstances,it is necessary to have different nominal rates to establish a desired structure ofeffective rates with the minimum necessary discrimination. Though there are afew valid cases for discrimination between commodities in terms of differentialexport or import rates of exchange, there hardly seems to be any case in thesame industry for discrimination in favour of the domestic market and againstthe export market, excepting when there is a monopoly power to be exploited inthe export market and when the social evaluation of risks and uncertainties ofselling abroad depress the returns from exports below that of the domestic sales2.On the one hand, if the social evaluation of the risks of the export and domesticsales is the same, but at the same time, private evaluation of risks of the exportsales is higher than the social evaluation, an effective export subsidy higher than

1 The evaluation of the relative performance of the individual manufactured exports bymeans of the individual rates of growth, especially in the case of a large number of new manu-factured exports each of which are very small value, is subject to a serious limitation in thesense that the lower the base year, the higher the rate of growth.

2 J Bhagwati, 'The Theory of Practice of Commercial Policy: Departures from UnifiedExchange Rates,' Papers in International Finance, No. 8, January 1968, Princeton University,USA, pp. 11-14.

C

186 BULLETIN

the effective protection, instead of the other way round, seems warranted. A casein point is when a pioneering firm in an industry incurs costs in introducing itsproduct and establishing itself in the export market, which it cannot fully recoverowing to the late corners or 'follow up' firms reaping the benefits of export sales,without having to incur any of the costs.

Pakistan Institute of Development Economics,Karachi

Indu

stry

APP

EN

DIX

TA

BL

E 1

Eff

ectiv

e Pr

otec

tion

and

Exp

ort S

ubsi

dyN

on-t

rade

d In

puts

not

Def

late

dN

on-t

rade

d In

puts

in V

alue

Add

ed

Eff

ectiv

eSu

bsid

y19

63-6

4(1

)

Efi

ectiv

eR

ate

ofPr

otec

tion

(2)

Eff

ectiv

eSu

bsid

y19

65-6

6(3

)

Eff

ectiv

eSu

bsid

y79

63-6

4(4

)

EU

ectiv

eR

ate

ofPr

otec

tion

(5)

Eff

ectiv

eSu

bsid

y19

65-6

6(6

)

Can

ning

of

frui

ts a

nd v

eget

able

sB

aker

y pr

oduc

ts a

nd c

onfe

ctio

nery

Suga

r...

......

....

...

-0.6

938

2.35

14-0

.339

6-.

5608

1.43

67-

.015

5E

dibl

e oi

ls a

nd f

ats

.....

...-2

.543

65.

0000

-1.0

700

13.8

669

2.12

36-3

.368

7A

lcoh

olic

bev

erag

esT

obac

co p

rodu

cts

Cot

ton

text

iles

...

...

.....

.860

1.8

7995

.872

5.6

387

.680

5.6

645

.932

2.8

896

.803

8.7

017

Woo

l tex

tiles

....

. -.

....

.

Jute

text

iles

......

- -.

- -.

- -.

.645

3.8

024

6453

.450

6.6

466

.450

6Si

lk a

nd a

rt, s

ilk te

xtile

s. -

....

....0

334

1.19

01.3

268

1.54

95.9

900

1.10

98-0

.294

2.5

868

Kni

tting

. . -

......

......

Thr

ead

ball

....5

259

.619

8.0

584

.356

0.4

505

.015

7.8

156

.632

2.6

926

.464

0M

anuf

actu

re a

nd r

epai

r of

foo

twea

r.4

565

.459

5.2

909

.368

2.3

711

.217

3.6

874

.479

2.6

076

.390

4W

eari

ng A

ppar

el...

......

.621

91.

2703

.742

61.

1686

0.95

001.

1098

-4.4

377

.543

6.7

576

1.24

52z

Man

uf. o

f co

rk a

nd w

ood

prod

ucts

. -.

-, -

0.90

47.9

200

.867

2.3

908

.479

2.1

866

0.95

05.8

988

.665

4.3

571

Man

ufac

t. of

pap

er a

nd p

aper

pro

duct

sA

rtic

les

of p

aper

and

pap

er b

oard

......

.747

8.7

899

.665

8.5

298

.590

2.4

264

Prin

ting,

Pub

lishi

ng a

nd a

llied

indu

stri

es. .

-.4

925

1.79

65.3

978

.421

3.1

379

.330

5T

anni

ng a

nd le

athe

r ta

nnin

g...

......

.854

5.8

501

.733

8.4

986

.489

8.3

173

Z.7

891

.387

4M

anuf

actu

re o

f ru

bber

......

.. -

2.19

651.

2198

8.42

39.6

183

.840

0.4

830

1.32

752.

1945

.791

1.6

184

Man

ufac

ture

of

fert

ilize

r.,.

...1.

3036

1.17

011.

6086

.497

8.6

503

.362

1Pa

ints

and

var

nish

es. -

,...

....6

725

.719

9.5

611

.515

7.5

708

.400

0.8

184

.603

8.6

992

.442

2Pe

rfum

es, c

osm

etic

s an

d so

ap. .

-...

-..

.608

4.6

399

.448

0.6

633

.690

4.5

255

.796

0.6

651

.824

6.7

121

Sour

ce:

S. R

. Lew

is a

nd S

. E. G

uisi

nger

, Mea

suri

ng P

rote

ctio

n in

a D

evel

opin

g C

ount

ry: T

he C

ase

of P

akis

tan,

Res

earc

h M

emor

andu

mN

o. 6

, Cen

tre

for

Dev

elop

men

t Eco

nom

ics,

Will

iam

s C

olle

ge, W

illia

mst

own,

Mas

sach

uset

ts.

N. I

slam

and

I. O

. Mal

ik, '

Com

para

tive

Cos

ts o

f th

e M

anuf

actu

ring

Ind

ustr

y in

Pak

ista

n-A

Sta

tistic

al S

tudy

', R

esea

rch

Rep

ort N

o. 5

8, P

akis

tan

Inst

itute

of

Dev

elop

men

t Eco

nom

ics,

Kar

achi

, Jun

e 19

67.

W. T

ims,

Ana

lytic

al T

echn

ique

s fo

r D

evel

opm

ent P

lann

ing,

Pak

ista

n In

stitu

te o

f D

evel

opm

ent E

cono

mic

s, K

arac

hi, F

eb.

1968

, p. 1

99.

M. A

lam

gir,

'The

Dom

estic

Pri

ces

of I

mpo

rted

Com

mod

ities

in P

akis

tan;

A F

urth

er S

tudy

', Pa

kist

an D

evel

opm

ent R

evie

w,

Spri

ng, 1

968,

p. 4

4.

Indu

stry

Eff

ectiv

eSu

bsid

y79

63-6

4(1

)

Eff

ectiv

eR

aie

ofPr

otec

tion

(2)

Eff

ectiv

eSu

bsid

y19

65-6

6(3

)

Eff

ectiv

eSu

bsid

y79

63-6

4(4

)

Eff

ectiv

eR

ate

ofPr

otec

tion

(5)

Eff

ectiv

eSu

bsid

y19

65-6

6(6

)

Mat

ches

..,...

...-

- -

.. -

1.57

66.0

991

.392

8.3

733

.082

7.3

441

Che

mic

al p

rodu

cts,

n.e

.s.

....

-.6

862

.750

0.5

844

.443

8.5

305

.324

0.8

232

.682

3.6

437

.438

8C

oal a

nd p

etro

leum

pro

duct

s-

--

--

....5

106

.075

3.4

159

.435

9-.

0526

.345

3M

anuf

actu

re o

f no

n-m

etal

lic-

....

....6

002

.780

2.4

873

.021

4.4

186

- .1

198

Min

eral

pro

duct

s (1

)..

......

....7

644

.628

5.3

812

.080

0M

anuf

actu

re o

f no

n-m

etai

lic...

......

.448

7.3

902

.344

6-

.129

7.3

289

-.38

35M

iner

al p

rodu

cts

(2)

......

....2

857

-.06

21B

asic

met

al in

dust

ries

......

......

.827

6.8

400

.767

4.6

385

.659

9.5

434

Man

ufac

ture

of

met

al p

rodu

cts.

.....

...1.

2437

1.13

001.

3932

2.6

106

.729

7.5

181

1.11

061.

2485

.757

7.6

067

Mac

hine

ry, e

xcep

t ele

ctri

cal (

1)...

....6

640

.780

2.5

298

.485

2.6

296

.347

8.8

235

.700

3.6

911

.527

3Z

Mac

hine

ry, e

xcep

t ele

ctri

cal (

2)...

....5

793

.579

8.6

2687

.236

2.4

505

.354

0E

lect

rica

l mac

hine

ry (

1)...

......

....7

729

1.03

00.8

625

.5 1

60.4

186

.422

01.

2137

.690

0.6

805

.546

2E

lect

rica

l mac

hine

ry (

2)...

.... -

....

.568

4.4

709

.540

75.4

186

.488

0M

anuf

actu

re o

f tr

ansp

ort e

quip

men

t...

-0.4

192

2.56

25-0

.218

31.

3953

1.05

001.

2233

-0.5

699

1.71

53Ph

otog

raph

ic a

nd o

ptic

al g

oods

Plas

tic p

rodu

cts

......

.....

...-3

.248

1.8

700

-0.5

117

- .9

157

.770

1.3

499

Spor

t and

ath

letic

goo

ds...

......

.437

7.4

792

.354

7.3

877

.428

6.3

081

Pens

, pen

cils

and

rel

ated

pro

duct

s. .

-.3

860

.710

1.2

378

.314

3.6

503

.176

7.6

200

.448

5.5

516

.375

3

APP

EN

DIX

TA

BL

E 1

Eff

ectiv

e Pr

otec

tion

and

Exp

ort S

ubsi

dyN

on-t

rade

d In

puts

not

Def

late

dN

on-t

rade

d In

puts

in V

alue

Add

ed