Equine Anesthesia || Anesthesia and Analgesia for Donkeys and Mules

Transcript of Equine Anesthesia || Anesthesia and Analgesia for Donkeys and Mules

KEY POINTS

1. Donkeys and mules have unique anatomical, physiological, and behavioral characteristics that are different from those of horses and that can affect anesthetic management.

2. Many donkeys and mules are stubborn and reluctant to move, especially after sedation.

3. Donkeys tend to be stoic and mask pain until it is severe.4. Donkeys metabolize many anesthetic and analgesic drugs

at different rates than horses. Doses or dosing intervals need to be adjusted accordingly.

5. Monitoring donkeys and mules under anesthesia is differentthan monitoring horses; more reliance on blood pressure and close observation of respiratory patterns are indicated.

A

nesthesia and Analgesia for Donkeys and MulesNora S. Matthews

18

Donkeys and mules present unique differences from horses. Mules are more variable in behavior, and their body type

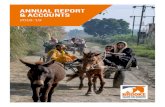

depends on the dam (e.g., Arab mares produce different foals than Draft Mares). Donkeys (burros) are of the species Equus asinus. Donkeys are registered on the basis of size in the United States. Miniature donkeys are less than 34 inches at the withers. Standard donkeys range in size from 34 to 54 inches at the withers, whereas mammoth donkeys are greater than 54 inches at the withers. Mules are produced from breeding a jackass (male donkey) to a mare (female horse). A hinny is produced by breeding a stallion to a jenny (female donkey), but mules and hinnies may be indistinguishable (Figure 18-1). Although both donkeys and mules have long ears, mules show horse characteristics (e.g., a more refined head, charac-teristic of the breed of horse used) and have a tail similar to that of a horse. The donkey has a tail similar to that of a cow, with only a switch of hair at the end.1

Agricultural use of donkeys and mules in North America has declined markedly since the early 1900s. Donkeys are used to guard sheep, goats, and calves from wild predators; whereas mules are used for logging and farm work. Both are primarily used for recreation (riding, driving, and packing) and as pets. Mule and donkey owners are frequently in touch with other owners through local and national clubs and organizations (Box 18-1). The United States is the largest producer of mules in the world. Both donkeys and mules are exported for use for trans-porting goods, agricultural products, water, and fuel; plowing; weeding; pulling carts; and recreational packing. It is estimated that over 50 million donkeys and mules are being used for these activities throughout the world (Global Livestock Pro duction and Health Atlas, Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations, NY, NY). A list of charitable organizations that provide veterinary care for these animals and who have collected useful information about their care is contained in Box 18-1.

PreoPerative evaluation

Behavioral DifferencesBehavioral differences are most evident in donkeys that have had little handling or training. Donkeys do not respond like horses when confronted with something new. They usually become immobile until acclimated (hence their reputation for stubbornness). Patience is required when trying to get them to perform tasks such as entering a stock or trailer. They are not easily “bullied” into movement. A nose twitch is frequently ineffective in restraining donkeys (in part because it slides off the nose easily). Donkeys may be ade-quately restrained by snubbing the head rope securely to a stout fixed object. Mules can be more difficult to work with than donkeys (unless well trained) and are considerably more dangerous because of their larger size. It is strongly recommended to have an experienced mule handler avail-able when working with untrained mules. Both mules and donkeys may strike without warning.

Donkeys and mules are stoic, making it difficult to assess pain or illness; it is likely that they are sicker or have more pain than casual observation and physical examination suggest. There is a myth that says that donkeys and mules don’t colic. This is not true, but mild bouts of colic are rarely observed because of their stoic nature. Since donkeys and mules may be quite ill before being presented for treatment or surgery, they present a significant anesthesia risk (see Chapter 22).

Physiological DifferencesThere are numerous physiological differences between don-keys and horses.2 Donkeys are adapted to the desert; increases in hematocrit, commonly seen with dehydration in horses, do not occur until donkeys are approximately 30% dehy-drated. Therefore assessing moderate dehydration by packed cell volume or hematocrit is inaccurate. Although generally resistant to disease, donkeys are susceptible to hyperlipid-emia when anorexic.3 Any donkey that is “off feed” should have triglyceride levels checked. In addition, mule foals are more likely to have neonatal isoerythrolysis than horse foals.4 Hyperkalemic periodic paralysis has not been reported in mules; anecdotal reports suggest that a mare positive for this defect does not produce a mule with the defect.

anatomical DifferencesAnatomical differences that are relevant to anesthesia include: (1) the anatomy of the branches of the facial artery (i.e., the artery that is located under the temporal crest) makes it difficult to place an arterial catheter in that location; and (2) the jugular vein is located in the same position in the donkey as in the horse, but the cutaneous colli muscle

353

354 Chapter 18 n Anesthesia and Analgesia for Donkeys and Mules

Figure 18–1. Donkeys are of the species Equus asinus. A mule is pro-duced by breeding a male donkey to a mare. Mules (background) are larger than donkeys (foreground), have characteristics similar to those of horses, and are frequently used as pack animals. (Courtesy Dr. Craig London, Rock Creek Pack Station, Bishop, CA, www.rock creekpackstation.co).

Box 18–1 Organizations Devoted to Donkeys and Mules

American Donkey and Mule Society (ADMS)P.O. Box 1210Lewisville, TX 75667

Canadian Donkey and Mule AssociationCanadian Livestock Records Corporation2417 Holly LaneOttawa, Ontario, CANADA K1V OM7

The Donkey SanctuarySidmouthDevon, EX10 ONUUNITED KINGDOM

table 18–1. Suggested analgesics, dose, and dosing intervals for donkeys and mules

Drug

Dose (mg/kg), route

Dosing interval

Donkeys Mules

Phenylbutazone 4.4, IV, PO bid-tid bidVedaprofen 1.0, PO bid NA*Flunixin 1.1, IV tid NACarprofen 0.7, IV, PO q24h NAMeloxicam 0.6, IV bid-tid NABuprenorphine

Nalbuphine

0.003-006, IV†

0.1, IV

NA

NA

NA

NA

bid, Twice a day; IV, intravenously; NA, not applicable; PO, orally; tid, three times a day.

*No pharmacokinetic data available.†Combined with sedative.

is a sheet of fascia and the skin is thicker; thus needles should be angled more perpendicular to the skin, similar to performing an intravenous injection in cattle when placing a jugular catheter.5 A neck rope may make the jugular vein more visible.

normal valuesNormal values for body temperature, respiration, and heart rate are slightly different than for horses. The don-key is thermolabile. Body temperature may increase to a greater degree than expected in donkeys in a hot cli-mate or following exercise. Heart rate responses appear to be similar to those in horses and are a good indicator of stress or pain when other indicators (such as appearance) do not indicate stress. Normal resting respiratory rates for donkeys are higher than in horses; 20 to 30 breaths/min is normal.

Normal baseline values for most hematological and biochemical indices have been published for donkeys and mules, and slight differences from horses are normal.6-8 Normal values from horses should not be extrapolated to

either donkeys or mules. Some normal values have not been documented; normal plasma protein levels and adrenocor-ticotropic hormone values have not been established for young donkeys and mules, making it difficult to diagnose some conditions (e.g., failure of passive immunity or cushin-goid syndrome) with certainty.

Preoperative analgesia in Donkeys and MulesPreoperative analgesia is particularly important in donkeys and mules and should have the primary emphasis, espe-cially for painful (e.g., orthopedic) conditions. Inadequate pain management can occur easily in donkeys because pain is not easily recognized and differences in drug metabolism have not been investigated adequately. Failure to provide adequate preoperative analgesia may result in inadvertent anesthetic overdose, resulting in cardiovascular collapse soon after induction. This situation is similar to but more common than that in horses in severe pain or those with chronic painful conditions (e.g., chronic laminitis); but, since it is easier to recognize severe pain in horses, it is less likely to occur. Donkeys require higher doses of nonsteroi-dal antiinflammatory drugs or shorter dosing intervals to achieve a degree of analgesia similar to that produced in horses since they metabolize many drugs more rapidly than horses (Table 18-1). This is especially true of miniature donkeys since they metabolize flunixin more rapidly than standard donkeys.

PreMeDiCation anD SeDation for StanDing ProCeDureS

Most sedatives and preanesthetic medications used in horses can be administered to donkeys and mules with good results (see Chapters 10, 12, and 13). Generally mules require 50% more drug than donkeys or horses to achieve adequate sedation. Standing procedures can be accomplished with the same drugs or their combinations (e.g., acepromazine with xylazine; xylazine with butorphanol) used in horses. Larger doses (two to three times larger) and combination drug therapies are required for untrained, excited, or feral horses, donkeys, and mules (see Table 18-1).9 The route of administration affects the dose required; generally the

Chapter 18 n Anesthesia and Analgesia for Donkeys and Mules 355

amount of the intravenous dose required is twice that of the intramuscular dose. The same precautions should be observed for sedated mules or donkeys as for untrained or feral horses since they are more likely to bite or kick. It is not uncommon for donkeys to lie down after being admin-istered a preanesthetic dose of xylazine; they do not fall down but deliberately lie down when they become unco-ordinated. Anesthetic-induction drugs can be administered with the donkey in sternal recumbency.

inDuCtion anD MaintenanCe of general aneStheSia with injeCtaBle DrugS

Smooth induction and maintenance of anesthesia depend on adequate sedation. A variety of injectable drugs are advocated for induction and maintenance of anesthesia (Table 18-2). Ketamine after sedation with an a

2-agonist is generally accept-

able but is metabolized more rapidly in donkeys and mules than in horses. Faster metabolism in conjunction with a more rapid distribution phase results in higher doses and more fre-quent readministration (shorter dosing intervals; see Chapter 9).10 This is especially important in miniature donkeys in which a surgical plane of anesthesia will not be achieved if horse doses of xylazine and ketamine are administered. If repeat administration of ketamine (by bolus or infusion) is not possible, a local block with lidocaine helps to ensure ade-quate analgesia during the latter stages of the procedure. The addition of butorphanol to a xylazine- ketamine drug com-bination enhances analgesia and extends the duration of anesthesia.

Drug Dose: Donkeys (mg/kg iv

Preanesthetics

Xylazine 0.6-1.0Detomidine 0.005-0.02Romifidine 0.1Butorphanol 0.02-0.04Diazepam 0.03Acepromazine 0.05Midazolam 0.06

Induction

Ketamine 2.2*Thiopental 5.0Tiletamine-zolazepam 1.1Guaifenesin 20-35 with ketamine or thioPropofol 2.2

Maintenance

Propofol 0.2-0.3 mg/kg/miG-K-X‡ 1.1 ml/kg/hrG.G. with thiopental§ “To effect” with careful mon

respiration

table 18–2. Preanesthetics and anesthetics for inducti

*More rapidly metabolized than in the horse; must redose at shorter in†No information available.‡50 mg/ml; 2 mg/ml; 0.5 mg/ml.§50 mg/ml; 3 mg/ml.

guaifenesin-Ketamine-Xylazine administration to DonkeysThe drug combination guaifenesin-ketamine-xylazine (GKX) produces smooth induction and maintenance of anesthesia in donkeys. Preanesthetic medication with xyla-zine (1.1 mg/kg intravenously [IV]) or an equivalent dose of another a

2-adrenoceptor agonist (e.g., romifidine, deto-

midine) usually produces adequate sedation. Induction to anesthesia is accomplished by rapid infusion (gravity flow) of 1 L of 5% guaifenesin to which 2 g of ketamine and 500 mg of xylazine have been added. Once the donkey is recumbent, the infusion rate is reduced to approximately 1 ml/kg/hr (based on eye signs, respiratory rate and pattern, and heart rate). The increased concentration of ketamine (rapidly metabolized in donkeys) compared to that used in horses (1 g/L) is important because donkeys are more sensitive to the respiratory depressant effects of guaifene-sin.11 Anesthetic induction in mules can be accomplished by administering xylazine (1.6 mg/kg IV) followed by ket-amine (2.2 mg/kg IV); then the GKX drug combination is infused to effect.

Thiopental used alone or in combination with guaifen-esin produces anesthesia in donkeys and mules with good results; but caution is required if guaifenesin is used since less guaifenesin is required to produce anesthesia in don-keys and the biological half-life is longer (see Table 18-2).11

Other drugs that can be administered to donkeys and mules are tiletamine-zolazepam (Telazol). This drug com-bination provides a slightly longer period of anesthesia and is recommended for miniature donkeys.12 Propofol can be

) Dose: Mules (mg/kg iv)

1.0-1.60.01-0.030.150.02-0.040.030.05-0.10.06

2.2*5.01.1

pental 20-35 with ketamine or thiopentalNA†

n NA1-2 ml/kg/hr

itoring of

on or injectable anesthesia in donkeys and mules

tervals.

356 Chapter 18 n Anesthesia and Analgesia for Donkeys and Mules

used for induction and maintenance in donkeys following sedation with xylazine. Since apnea and desaturation are common problems with propofol, it is not recommended for use unless intubation or oxygen supplementation is available.

MaintenanCe with inhalant aneSthetiCS

Endotracheal intubation and maintenance with inhalant anesthetics is preferred for longer procedures in donkeys and mules. Endotracheal intubation is easily achieved using the same technique as in horses; on occasion it may be nec-essary to use a slightly smaller endotracheal tube, especially if the depth of anesthesia is not sufficient to produce ade-quate relaxation for intubation. Additional injectable anes-thetic drugs, preferably thiopental, should be available to deepen anesthesia if required. Miniature donkeys (espe-cially those with dwarflike features) may have hypoplastic tracheas and abnormal airway anatomy similar to that of (dwarflike) miniature horses.

Minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) values for halothane and isoflurane in donkeys are similar to those of horses.13 The MAC value for sevoflurane has not been determined in donkeys and mules, but clinical experience suggests that the same vaporizer settings should be used. Donkeys and mules are monitored using procedures and techniques identical to those used for horses (see Monitoring Anesthesia).

I have observed several donkeys that experienced severe bradycardia and profound hypotension after induc-tion to general anesthesia with inhalant anesthetics. Anticholinergics and inotropic drugs reversed this pro-cess. All of these donkeys had very painful orthopedic conditions (i.e., “three-legged” lame, severe laminitis), which may have produced an exaggerated sympathoadre-nal response and may not have been adequately treated with analgesics before surgery because of a failure to rec-ognize pain.

Monitoring aneStheSia

Anesthetic monitoring in donkeys and mules is similar to that for horses with some subtle differences. Eye signs (nystagmus, corneal and palpebral reflexes, rotation of the eyeball) are helpful and similar to those in horses, but they are not as reliable in donkeys. Direct or indi-rect monitoring of arterial blood pressure is strongly rec-ommended; blood pressure increases as the patient gets “light” and is a more reliable indicator of depth of anes-thesia than eye signs. When placing an arterial catheter, the (thicker) skin should be perforated with a needle before introducing the catheter to prevent “burring” of the catheter. Branches of the facial artery and the dorsal metatarsal and auricular arteries are good sites for arterial catheter placement.

Treatment of hypotension (defined as a mean arterial pressure less than 60 mm Hg) should be similar to that in horses; the plane of anesthesia should be decreased if possible, intravenous fluids should be increased, and ino-trope drugs should be administered until appropriate blood pressure is restored (see Chapter 22). An increase in

hematocrit may not be seen with mild-to-moderate dehy-dration in donkeys or mules; thus the anesthetist should not rely on packed cell volume as an initial guide for fluid administration.

Respiratory rate and pattern should be observed care-fully; normal respiratory rates are greater in donkeys than in horses, but breath holding may occur during a painful procedure. An increase in tidal volume and spontaneous “sighing” are usually suggestive of a very light plane of anesthesia.

Postanesthetic myositis is less likely to occur in don-keys than horses since they have much less muscle mass. Myositis and myopathy can occur in mules, especially Draft Mules. Care should be taken to pad body surfaces and superficial nerves (i.e., facial and radial) appropriately (see Chapter 21).

It is important to ensure that airflow is not compro-mised in donkeys that are not orotracheally intubated. The head should be positioned to ensure that the airway is not kinked or obstructed by their excessive nasal tissue. Straightening the position of the head relative to the neck or placing a nasal cannula usually relieves inspiratory noise.

reCovery froM aneStheSia

Recovery from anesthesia is usually not affected by the occasional hysteria seen in horses because donkeys gen-erally are calmer (see Chapter 21). Analgesia should be provided. Donkeys generally lie quietly until they are able to regain a sternal position and stand; they may make a half attempt to stand and lie back down if not coordinated enough. It is generally not necessary to “hand recover” donkeys. They frequently stand hind-end first (like a cow) or get up on one knee with the hind legs first. Mules are highly variable in their response to recovery and may require assistance with head and tail ropes similar to horses.

analgeSia

The analgesics used in horses are appropriate for don-keys and mules; but the dose or dosing interval should be adjusted, and pain should be assessed frequently (see Table 18-1). There are currently no data on the usefulness of transdermal fentanyl (patches) in donkeys or mules. Although fentanyl concentrations are achieved rapidly in horses via the transdermal route, donkeys have thicker skin, which could inhibit fentanyl absorption and produce dif-ferences in the rate of absorption from dermal sites (e.g., a thick fascial layer on the neck might prevent absorp-tion). Epidural administration of local anesthetic drugs and other analgesics are very useful in providing anesthesia for procedures of the caudal region or analgesia for postop-erative pain (see Chapter 11).14 No differences between donkeys and mules and horses have been reported using epidural or spinal techniques.

In conclusion, although it is tempting to treat donkeys and mules like horses, there are subtle and at times signif-icant differences in physiology, behavior, and response to anesthetic drugs that must be taken into account to provide successful and minimally stressful anesthesia.

Chapter 18 n Anesthesia and Analgesia for Donkeys and Mules 357

RefeRences

1. Taylor TS, Matthews NS, Blanchard TL: Introduction to don-keys in the US: elementary assology, N Engl J Large Anim Health 1:21-28, 2001.

2. Yousef MR: The burro: a new backyard pet: its physiology and survival, Calif Vet 33:31-34, Oct 1979.

3. Watson TDG et al: An investigation of the relationships between body condition and plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentra-tions in 24 donkeys, Vet Rec 127:498-500, 1990.

4. Traub-Dargatz JL : Neonatal isoerythrolysis in mule foals, J Am Vet Med Assoc 206:67-70, 1995.

5. Sobti VK, Dhiman N, Singh KI: Ultrasonography of normal palmar metacarpal soft tissues in donkeys, Indian J Vet Surg 17:37-38, 1996.

6. Zinkl JG et al: Reference ranges and the influence of age and sex on hematologic and serum biochemical values in donkeys, Am J Vet Res 51:408-413, 1990.

7. Mori E et al: Reference values on serum biochemical param-eters of Brazilian donkey breed, J Equine Vet Sci 23:358-364, 2003.

8. Terkawi A, Tabbaa D, Al-Omari Y: Estimation of normal haematology values of local donkeys in Syria. In Proceedings of the Fourth Colloquium on Working Equines, Hama, Syria, 2002, pp 115-118.

9. Hubbell JAE et al: Anesthetic, cardiorespiratory, and meta-bolic effects of four intravenous anesthetic regimens induced in horses immediately after maximal exercise, Am J Vet Res 61: 1545-1552, 2000.

10. Matthews NS et al: Pharmacokinetics of ketamine in mules and mammoth asses premedicated with xylazine, Equine Vet J 26:241-243, 1994.

11. Matthews NS et al: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of guaifenesin in donkeys, Vet Surg 25:184, 1996.

12. Matthews NS, Taylor TS, Sullivan JA: A comparison of three combinations of injectable anesthetics in miniature donkeys, Vet Anaesth Analg 29:36-42, 2002.

13. Mercer DE, Matthews NS: Minimum alveolar concentrations of halothane and isoflurane in donkeys and MAC-sparing effect of butorphanol. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth PanVet Congress, Campo Grande, Brazil, 1996, p 129.

14. Shoukry M, Seleh M, Fouad K: Epidural anaesthesia in donkeys, Vet Rec 97:450-452, 1975.