Effect of ticagrelor on the outcomes of patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery:...

Transcript of Effect of ticagrelor on the outcomes of patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery:...

Effect of ticagrelor on the outcomes of patients withprior coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Insightsfrom the PLATelet inhibition and patient outcomes(PLATO) trialEmmanouil S. Brilakis, MD, PhD, a Claes Held, MD, PhD, b Bernhard Meier, MD, c Frank Cools, MD, d

Marc J. Claeys, MD, PhD, e Jan H. Cornel, MD, PhD, f Philip Aylward, BM, BCh, PhD, g Basil S. Lewis, MD, h

Douglas Weaver, MD, i Gunnar Brandrup-Wognsen, MD, PhD, j Susanna R. Stevens, k Anders Himmelmann, j

Lars Wallentin, MD, PhD, b and Stefan K. James, MD, PhDb Dallas, TX; Uppsala, and Mölndal, Sweden; Bern,Switzerland; Antwerp, Belgium; Alkmaar, The Netherlands; Tonsley, Australia; Haifa, Israel; Detroit, MI; and Durham, NC

Background Patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) who present with an acute coronarysyndrome have a high risk for recurrent events. Whether intensive antiplatelet therapy with ticagrelor might be beneficialcompared with clopidogrel is unknown. In this substudy of the PLATO trial, we studied the effects of randomized treatmentdependent on history of CABG.

Methods Patients participating in PLATO were classified according to whether they had undergone prior CABG. Thetrial's primary and secondary end points were compared using Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results Of the 18,613 study patients, 1,133 (6.1%) had prior CABG. Prior-CABG patients had more high-riskcharacteristics at study entry and a 2-fold increase in clinical events during follow-up, but less major bleeding. The primary endpoint (composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke) was reduced to a similar extent by ticagreloramong patients with (19.6% vs 21.4%; adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.91 [0.67, 1.24]) and without (9.2% vs 11.0%; adjustedHR, 0.86 [0.77, 0.96]; Pinteraction = .73) prior CABG. Major bleeding was similar with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel amongpatients with (8.1% vs 8.7%; adjusted HR, 0.89 [0.55, 1.47]) and without (11.8% vs 11.4%; HR, 1.08 [0.98, 1.20];Pinteraction = .46) prior CABG.

Conclusions Prior-CABG patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome are a high-risk cohort for death andrecurrent cardiovascular events but have a lower risk for major bleeding. Similar to the results in no-prior-CABG patients,ticagrelor was associated with a reduction in ischemic events without an increase in major bleeding. (Am Heart J2013;166:474-80.)

Patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery(CABG) who present with an acute coronary syndrome

From the aVA North Texas Healthcare System and UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas,TX, bDepartment of Medical Sciences, Cardiology and Uppsala Clinical Research Center,Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, cBern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland, dAZKLINA, Brasschaat, Antwerp, Belgium, eUniversity Hospital Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium,fDepartment of Cardiology, Medisch Centrum Alkmaar, Alkmaar, The Netherlands, gSouthAustralian Health and Medical Research Institute, Flinders University and Medical Centre,Tonsley, Australia, hLady Davis Carmel Medical Center, Haifa, Israel, iHenry Ford Heart andVascular Institute, Detroit, MI, jAstraZeneca Research and Development, Mölndal, Sweden,and kDuke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.Clinical Trial Registration: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT00391872.Eric R. Bates, MD, FACC, served as guest editor for this article.Submitted April 19, 2013; accepted June 13, 2013.Reprint requests: Emmanouil S. Brilakis, MD, PhD, Dallas VA Medical Center (111A), 4500South Lancaster Road, Dallas, TX 75216.E-mail: [email protected]/$ - see front matter© 2013, Mosby, Inc. All rights reserved.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2013.06.019

(ACS) have a high risk for immediate and recurrentcardiovascular events and death.1,2 Although guideline-based treatment, especially intensive lipid-loweringtherapy,2,3 may be beneficial, additional therapies areneeded to reduce the high residual risk.1

Prior-CABG patients may benefit from intensive antith-rombotic and antiplatelet therapies.4 After the initial 5years after CABG, recurrent cardiovascular events aremostly due to saphenous vein graft (SVG) failure5 andoften result in SVG occlusion.6 Saphenous vein graftdisease is difficult to treat because of high rates ofrestenosis7 and progression of disease in nonstented SVGsegments 8 and has been associated with poorprognosis.9,10

Ticagrelor is a reversible and direct-acting oral antagonistof the adenosine diphosphate receptor P2Y12 that pro-vides faster, greater, and more consistent P2Y12 inhibitionthan clopidogrel. The PLATelet inhibition and patient

Table I. Baseline and in-hospital characteristics by whether patients had undergone prior CABG

Characteristic Prior CABG (n = 1133) No prior CABG (n = 17480) P value

DemographicsAge, median (25th-75th percentile), y 66 (59-74) 62 (54-70) b.0001Age ≥75 y, n (%) 261 (23.0) 2615 (15.0) b.0001Female gender, n (%) 226 (19.9) 5058 (28.9) b.0001Race, n (%) b.0001White 1074 (94.8) 15993 (91.5)Black 23 (2.0) 206 (1.2)Asian 19 (1.7) 1077 (6.2)Other 17 (1.5) 204 (1.2)

Body weight b60 kg, n (%) 49 (4.3) 1263 (7.2) .0002Body mass index, median (25th-75th percentile), kg/m2 28.1 (25.3-31.1) 27.3 (24.7-30.4) b.0001Waist circumference, median (25th-75th percentile), cm 102 (94-110) 98 (90-106) b.0001Concomitant disease, n (%)Hypertension 928 (81.9) 11255 (64.4) b.0001Dyslipidemia 924 (81.6) 7765 (44.4) b.0001Diabetes mellitus 475 (41.9) 4187 (24.0) b.0001Current smoking 214 (18.9) 6464 (37.0) b.0001

History, n (%)Angina pectoris 922 (81.4) 7436 (42.5) b.0001MI 660 (58.3) 3164 (18.1) b.0001PCI 466 (41.1) 2026 (11.6) b.0001Peripheral arterial disease 174 (15.4) 970 (5.5) b.0001Nonhemorrhagic stroke 64 (5.6) 658 (3.8) .0015Transient ischemic attack 67 (5.9) 432 (2.5) b.0001Congestive heart failure 166 (14.7) 884 (5.1) b.0001Chronic renal disease 125 (11.0) 660 (3.8) b.0001

Index event and intended approachFinal ACS diagnosis, n (%) b.0001STEMI 130 (11.5) 6896 (39.5)NSTEMI 688 (60.8) 7267 (41.6)UA 274 (24.2) 2838 (16.3)Other 40 (3.5) 449 (2.6)

Hours since symptom onset, median (25th-75th percentile) 14.8 (7.4-21.0) 10.2 (4.3-18.5) b.0001Planned invasive, n (%) 758 (66.9) 12640 (72.3) .0001PCI or CABG during index hospitalization 583 (51.5) 11702 (66.9) b.0001PCI during index hospitalization 560 (49.4) 10833 (62.0) b.0001Any native coronary artery PCI 504 (44.8) 10833 (62.0) b.0001Any SVG PCI 354 (31.5) 0 (0) b.0001Multivessel PCI 110 (20.0) 1508 (14.1) .0001Type of stent b.0001No stent 56 (10.2) 674 (6.3)Bare metal stent(s) only 260 (47.2) 7089 (66.2)At least 1 drug-eluting stent 235 (42.6) 2941 (27.5)

Management during index hospitalization (1 category, hierarchy as ordered) b.0001CABG 26 (2.3) 944 (5.4)SVG PCI 352 (31.5) 0 (0)Native coronary artery PCI 191 (17.1) 10758 (61.5)Angiography 312 (27.9) 2745 (15.7)Medical therapy 238 (21.3) 3033 (17.4)

Biomarkers, median (25th-75th percentile)Creatinine, μmol/L 88 (80-106) 80 (71-97) b.0001Glucose, mmol/L 6.8 (5.6-9.2) 6.9 (5.7-8.8) .7053HbA1C, % 6.3 (5.8-7.3) 6.0 (5.6-6.6) b.0001Hemoglobin, g/L 137 (125-148) 140 (129-149) b.0001NT-proBNP, pmol/L 90 (31-265) 57 (18-178) b.0001Troponin I, μg/L 1.48 (0.10, 7.28) 2.13 (0.23, 12.4) b.0001

Medications before index event, n (%)Aspirin 835 (73.7) 5213 (29.9) b.0001β-Blockers 681 (60.1) 4694 (26.9) b.0001ACE inhibitors or ARB 694 (61.3) 5828 (33.4) b.0001Statins 771 (68.0) 4297 (24.6) b.0001Calcium-channel blockers 224 (19.8) 2078 (11.9) b.0001Diuretics 358 (31.6) 2451 (14.0) b.0001

(continued on next page)

Brilakis et al 475American Heart JournalVolume 166, Number 3

Table I (continued )

Characteristic Prior CABG (n = 1133) No prior CABG (n = 17480) P value

Medications from index event to randomization, n (%)Aspirin 1065 (94.0) 16516 (94.5) .4877β-Blockers 888 (78.4) 12301 (70.4) b.0001ACE inhibitors or ARB 860 (75.9) 11110 (63.6) b.0001Statins 1008 (89.0) 13759 (78.8) b.0001Calcium-channel blockers 259 (22.9) 2659 (15.2) b.0001Diuretics 483 (42.6) 4175 (23.9) b.0001

Medications from index event to discharge, n (%)Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor 302 (26.7) 4735 (27.1) .7504Unfractionated heparin 633 (55.9) 10144 (58.0) .1530Low–molecular weight heparin 581 (51.3) 9067 (51.9) .6997Fondaparinux 17 (1.5) 492 (2.8) .0086Bivalirudin 63 (5.6) 311 (1.8) b.0001

Aspirin dose b.00010 72 (6.4) 1148 (6.6)b100 mg 319 (28.2) 4740 (27.2)100 mg 477 (42.2) 8544 (49.1)N100 mg 262 (23.2) 2972 (17.1)

STEMI, ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non–ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina; ACE, angiotensin-convertingenzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide.

Table II. Clinical events of the study population classified according to whether they had undergone prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery

VariablePrior CABG(n = 1133)

No prior CABG(n = 17480)

Unadjusted Adjusted

HR (95% CI) P HR (95% CI) P

Primary outcome: CV death/MI (excl. silent)/stroke 20.5 (216) 10.1 (1662) 2.06 (1.79, 2.38) b.0001 1.43 (1.20, 1.70) b.0001CV death/MI/stroke in patients intended forinvasive management

18.9 (131) 9.3 (1106) 2.03 (1.69, 2.43) b.0001 1.36 (1.09, 1.70) .0072

CV death/MI (all)/stroke/severe recurrent ischemia/recurrent ischemia/TIA/arterial thrombotic event

27.9 (295) 14.9 (2451) 1.94 (1.72, 2.18) b.0001

All-cause death 8.2 (85) 5.0 (820) 1.60 (1.28, 2.00) b.0001 1.33 (1.01, 1.74) .0400MI (excluding silent) 13.8 (144) 5.9 (953) 2.39 (2.01, 2.85) b.0001Stroke 2.5 (25) 1.3 (206) 1.88 (1.24, 2.85) .0029Any stent thrombosis (definite, probable, or possible) 3.5 (33) 2.2 (339) 1.48 (1.04, 2.12) .0307Major bleeding (study criteria) 8.4 (84) 11.6 (1806) 0.72 (0.58, 0.89) .0029 0.45 (0.35, 0.59) b.0001Coronary procedure–related major bleeding 5.0 (51) 9.0 (1426) 0.55 (0.42, 0.73) b.0001Non-coronary procedure–related major bleeding 0.2 (2) 0.4 (62) 0.51 (0.12, 2.08) .3484Coronary procedure–related major or minor bleeding 6.2 (64) 10.8 (1718) 0.57 (0.44, 0.73) b.0001Non-coronary procedure–related major or minor bleeding 0.6 (6) 0.8 (113) 0.84 (0.37, 1.90) .6718Intracranial bleeding 0.4 (3) 0.3 (38) 1.27 (0.39, 4.11) .6925

HR, Hazard ratio; CV, cardiovascular; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

476 Brilakis et alAmerican Heart Journal

September 2013

Outcomes (PLATO) trial demonstrated significant reduc-tion with ticagrelor in the incidence of cardiovasculardeath, myocardial infarction (MI), and nonfatal stroke aswell as all-cause mortality among ACS patients.11 The goalof the present analysis was to examine the outcomes andthe effect of ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel amongprior-CABG ACS patients enrolled in PLATO.

MethodsPatientsThe primary results of the PLATO trial have been pub-

lished.11,12 In the present post hoc analysis, we classified thepatients according to prior CABG, which was one of the clinical

variables collected at enrollment in the study and was availablein 18,613 patients.

Statistical analysisContinuous parameters were presented as medians with

interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were reported aspercentages. The baseline characteristics of patients with andwithout prior CABG were compared using the Wilcoxon ranksum test for continuous parameters and the χ2 test forcategorical variables. Outcomes between the different groupsof patients were compared using the Cox proportional hazardsmethod and reported as Kaplan-Meier estimates at 360 days. Theinteraction between the efficacy of ticagrelor versus clopidogreland prior CABG status was tested by creating a Cox proportionalhazards model and using terms for both the main effects and the

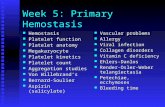

Figure

cidence of major adverse clinical events. Kaplan–Meier curves fore primary end point (cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke; A) andajor bleeding (B) with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel among patientsnrolled in the PLATO trial, classified according to whether they hadrior CABG.

Brilakis et al 477American Heart JournalVolume 166, Number 3

interaction. Postdischarge outcomes are summarized by revas-cularization strategy and CABG history using Kaplan-Meierestimates 360 days following discharge and total number ofevents following discharge among patients discharged fromindex hospitalization without the event.Adjusted models were developed for the primary efficacy and

safety end points and all-cause death based on backwardselection repeated in 1,000 bootstrap samples where asignificance level of .05 was required to stay in the model.Candidate variables included baseline demographics, medicalhistory, medications, laboratory results, and disease character-istics. Continuous variables were assessed for linearity on thelog-hazard scale for each outcome separately; and whenappropriate, linear splines were used. Interaction was alsoconsidered. Covariates chosen for one or more of theadjustment models included age, sex region, prior MI,nonhemorrhagic stroke, transient ischemic attack, peripheralarterial disease, prior CABG, diabetes, congestive heart failure,smoking status, dyslipidemia, angina pectoris, heart rate, systolicblood pressure, Killip class, time from symptoms to randomiza-tion, white blood cells, hemoglobin, creatinine, electrocardio-graphic changes at entry, ST-segment depression, positivetroponin, final ACS diagnosis, and randomized treatment. Aspirinuse at randomization was a candidate variable but was notselected for any of the models. A P value b.05 was consideredsignificant for all analyses. All statistical analyses were performedwith SAS software package (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

The PLATO study was funded by AstraZeneca. Support for theanalysis and interpretation of results and preparation of themanuscript was provided through funds to the Uppsala ClinicalResearch Center and Duke Clinical Research Institute as part ofthe Clinical Study Agreement. The authors are solely responsiblefor the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, thedrafting and editing of the paper, and its final contents.

ResultsPatient characteristicsOf the 18,613 study patients in whom prior CABG

history was known, 1,133 (6.1%) had prior CABG, ofwhom 352 (31%) underwent SVG intervention and 191(17%) underwent native coronary artery intervention.The baseline characteristics of the study patients areshown in Table I. The median time from CABG was 9 (5,13) years. Prior-CABG patients were older, more likely tobe men, and more likely to present with non–ST-segment elevation ACS. They were more likely to bewhite; to have higher body mass index and waistcircumference; and to have diabetes, hypertension, andhyperlipidemia, but were less likely to be currentsmokers. Prior-CABG patients were more likely to havea history of stroke, MI, percutaneous coronary interven-tion (PCI), peripheral arterial disease, chronic renaldisease, and congestive heart failure. Moreover, prior-CABG patients were less likely to undergo coronaryrevascularization by PCI or CABG (Table I). During PCI,prior-CABG patients were more likely to receive a drug-eluting stent and bivalirudin; yet use of glycoprotein IIb/

Inthmep

IIIa inhibitors was similar in the 2 groups. Comparedwith patients without prior CABG, prior-CABG patientswere more likely to receive calcium-channel blockers,angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and β-blockers; but aspirin use following the index eventwas similar in the 2 groups.

Outcomes in prior-CABG patientsCompared with patients without prior CABG, prior-

CABG patients had a higher risk for ischemic events,including a 2-fold increase in cardiovascular mortality,MI, and stroke (Table II and Figure). After adjustingfor baseline demographic and treatment differences,prior-CABG patients continued to have an increasedrisk for ischemic events. The incidence of majorbleeding was lower in prior-CABG patients because ofthe lower incidence of coronary procedure–relatedbleeding (Table II).

Ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel by priorCABG statusThere were few small differences in baseline charac-

teristics of the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups among

Table III. Outcomes with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with and without prior CABG

End point

Prior CABG No prior CABG

PTicagrelor(n = 547)

Clopidogrel(n = 586)

HR or OR(95% CI)

Ticagrelor(n = 8778)

Clopidogrel(n = 8702)

HR or OR(95% CI)

Primary outcome: CV death/MI(excl. silent)/stroke

19.6 (100) 21.4 (116) 0.90 (0.69, 1.17) 9.2 (764) 11.0 (898) 0.84 (0.76, 0.93) .6637

CV death/MI/stroke in patients intendedfor invasive management

17.8 (60) 19.8 (71) 0.86 (0.61, 1.22) 8.4 (509) 10.1 (597) 0.84 (0.75, 0.95) .8961

CV death/MI (all)/stroke/severe recurrentischemia/recurrent ischemia/TIA/arterial thrombotic event

27.3 (139) 28.5 (156) 0.93 (0.74, 1.16) 13.8 (1151) 15.9 (1300) 0.87 (0.81, 0.95) .6344

All-cause death 8.2 (41) 8.3 (44) 0.99 (0.65, 1.52) 4.3 (358) 5.7 (462) 0.77 (0.67, 0.88) .2638MI (excluding silent) 13.4 (67) 14.2 (77) 0.91 (0.65, 1.26) 5.3 (437) 6.4 (516) 0.84 (0.74, 0.95) .6462Stroke 2.0 (10) 2.9 (15) 0.70 (0.32, 1.56) 1.4 (115) 1.1 (91) 1.25 (0.95, 1.65) .1798Any stent thrombosis (definite, probable,or possible)

4.3 (19) 2.8 (14) 1.45 (0.73, 2.89) 1.8 (142) 2.5 (197) 0.72 (0.58, 0.89) .0569

Major bleeding (study criteria) 8.1 (39) 8.7 (45) 0.93 (0.61, 1.43) 11.8 (922) 11.4 (884) 1.04 (0.95, 1.14) .6141Coronary procedure–relatedmajor bleeding

4.7 (23) 5.3 (28) 0.88 (0.51, 1.53) 8.9 (709) 9.1 (717) 0.98 (0.89, 1.09) .7052

Non-coronary procedure–relatedmajor bleeding

0.2 (1) 0.2 (1) 1.08 (0.07, 17.29) 0.3 (26) 0.5 (36) 0.72 (0.44, 1.20) .7788

Coronary procedure–related majoror minor bleeding

5.9 (29) 6.6 (35) 0.89 (0.54, 1.46) 10.8 (866) 10.8 (852) 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) .6149

Non-coronary procedure–related majoror minor bleeding

0.6 (3) 0.7 (3) 1.08 (0.22, 5.35) 0.7 (50) 0.9 (63) 0.79 (0.55, 1.15) .7120

Intracranial bleeding 0.3 (1) 0.6 (2) 0.54 (0.05, 5.95) 0.3 (25) 0.2 (13) 1.93 (0.99, 3.77) .3160Any dyspnea⁎ 20.8% (112) 12.8% (74) 1.79 (1.30, 2.47) 13.3% (1158) 7.5% (647) 1.89 (1.71, 2.09) .7505Bradycardia⁎ 4.3% (23) 4.3% (25) 0.99 (0.55, 1.76) 4.4% (386) 4.0% (347) 1.11 (0.95, 1.28) .7108Ventricular pauses ≥3 s during first week† 9.6% (10) 3.6% (4) 2.87 (0.87, 9.46) 5.5% (74) 3.6% (48) 1.53 (1.05, 2.22) .3215

OR, Odds ratio.⁎Number of events with odds ratio and 95% CI.†Number of events with odds ratio and 95% CI among the n = 2893 (216 prior CABG and 2677 without prior CABG) with data from the Holter substudy.

478 Brilakis et alAmerican Heart Journal

September 2013

prior-CABG and no-prior-CABG patients (data notshown). The incidence of the primary end point wasreduced by ticagrelor by 16% in patients without priorCABG (9.2% vs 11.0%) and by 10% in patients with priorCABG (19.6% vs 21.4%; Pinteraction = .66) (Table III,Figure). The incidence of MI was reduced by 16% inpatients without prior CABG and by 9% in patients withprior CABG (Table III). The incidence of major bleedingwas similar in patients receiving ticagrelor versusclopidogrel in both the prior-CABG and the no-prior-CABG subgroup (data not shown). The age of the bypassgrafts was not associated with the effect of ticagrelorversus clopidogrel (data not shown). The adjustedhazard ratio for the primary end point for ticagrelorversus clopidogrel in the prior-CABG and no-prior-CABG groups was 0.91 (95% CIs 0.67, 1.24) for priorCABG and 0.86 (95% CIs 0.77, 0.96) for no priorCABG (Pinteraction = .7347). Similarly, the adjustedhazard ratio for all-cause death was 1.17 (95% CIs0.72, 1.89) for prior CABG and 0.82 (95% CIs 0.70,0.96) for no prior CABG (Pinteraction = .1757); and thatfor major bleed was 0.89 (95% CIs 0.55, 1.47) forprior CABG and 1.08 (95% CIs 0.98, 1.20) for no priorCABG (Pinteraction = .4570).

DiscussionOur analysis shows that patients with ACS and prior

CABG surgery (a) had higher cardiovascular risk that wasin part due to the higher baseline clinical characteristics,(b) had lower risk for major bleeding, and (c) derivedsimilar benefit from ticagrelor.

Increased risk of prior-CABG patientsPatients with prior CABG have higher risk for death and

major adverse cardiac events compared with patientswithout CABG. This has been shown in multiplestudies2,13-18 and is, at least in part, related to the baselinecharacteristics of those patients, such as older age andhigher likelihood to have diabetes, prior MI, stroke,peripheral arterial disease, and other comorbidities suchas congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease.Although smoking rates were lower in prior-CABGpatients, still 1 in 5 continued to smoke, suggesting thatpoor coronary artery disease risk factor control maycontribute to their high risk.19 Consistent with priorstudies, prior-CABG patients were less likely to presentwith ST-segment elevation and more likely to presentwith non–ST-segment elevation ACS.20

Brilakis et al 479American Heart JournalVolume 166, Number 3

Prior-CABG patients had lower incidence of majorbleeding compared with no-prior-CABG patients (TableIII). This is likely due to the lower use of coronaryrevascularization among prior-CABG patients (51% vs67%, P b .001), which in turn is probably due to moreadvanced coronary artery disease that limited revascular-ization options.21 As expected, only 2.3% of prior-CABGpatients underwent repeat CABG likely because of thesignificantly increased risk of repeated cardiac surgery inthis patient group.21

Efficacy and safety of ticagrelor in prior-CABG patientsIn PLATO, the primary end point was reduced with

ticagrelor to a similar extent in patients with and withoutprior CABG (Table III). Although the reduction in efficacyend points did not reach statistical significance in theprior-CABG group because of the small sample size (6.1%of the overall study population), the relative risk re-ductions were similar among patients with and withoutprior CABG (Table III).Prior studies examining antiplatelet therapies in prior-

CABG patients have provided conflicting results. Al-though prior-CABG patients participating in the Clopido-grel versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischaemic Eventstrial derived benefit from receiving clopidogrel instead ofaspirin,4 in the Clopidogrel for High AtherothromboticRisk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoid-ance trial (20% of the enrolled patients had prior CABG),there was no benefit of clopidogrel plus aspirin versusaspirin.22 In the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina toprevent Recurrent ischemic Event trial, patients whounderwent CABG had a trend for lower incidence of theprimary end point (composite of cardiovascular death,MI, or stroke) at 12 months (14.5% for clopidogrel, 16.2%for placebo; relative risk, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.11).23

Our study extends these prior findings by demonstratingthat intensive antiplatelet therapy with ticagrelor reducesischemic events among prior-CABG patients to a similardegree as in patients without prior CABG.

Study limitationsThis was a post hoc exploratory analysis of ticagrelor

versus clopidogrel for patients with prior CABG. Thenumber of prior-CABG patients was relatively small(6.1% of the total study population), limiting the powerof the analysis. Moreover, the performance of multiplesubgroup analyses might increase the likelihood offinding association by the play of chance. Enrollmentin PLATO was not stratified by prior CABG status, anddifferences about the ticagrelor and clopidogrel arms ofprior-CABG patients may exist. Moreover, the decision ofthe target vessel for PCI was at the discretion of theoperator. Prior-CABG patients were likely underrepre-sented in PLATO and other clinical trials: an analysisfrom the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Cath PCI

registry demonstrated that 17.5% of the total PCI volumebetween 2004 and 2009 occurred in prior-CABG patients(approximately two-thirds of whom presented withACS),24 yet prior-CABG patients comprised only 6.1%of the PLATO study population.

ConclusionsCompared with patients without prior CABG, prior-

CABG patients who present with an acute coronarysyndrome have significantly higher risk for death andadverse cardiac events and derive similar benefit fromticagrelor versus clopidogrel administration.

AcknowledgementsUlla Nässander Schikan, PhD, at Uppsala Clinical

Research Center, Uppsala, Sweden, provided editorialassistance.

DisclosuresE. S. Brilakis: speaker honoraria from St Jude Medical,

Terumo, and Bridgepoint Medical; research support fromGuerbet; spouse is an employee of Medtronic. C. Held:institutional research grants from AstraZeneca, Merck,GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Bristol-Myers Squibb andbeing an advisory board member for AstraZeneca; hono-raria from AstraZeneca. B. Meier: consultant/advisoryboard; AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, DaiichiSankyo, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi Aventis. F. Cools: reportsspeaker's fees from Astra Zeneca and Bayer; consultancyfees from Novartis. M. J. Claeys: honoraria from AstraZe-neca and Eli Lilly, consultant/advisory board fees fromAstraZeneca and Eli Lilly. J. H. Cornel: advisory board feesfrom BMS, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly/Daiichi Sankyo; consul-tancy fees from Merck and Servier. P. Aylward: researchsupport from AstraZeneca, Merck & Co, Eli Lilly, Bayer/Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi Aventis, GlaxoSmithKline, andDaiichi Sankyo; consultant and advisory board fees fromBoeringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Sanofi Aventis,and Eli Lilly; and travel support from Bristol Myers Squibb,AstraZeneca, and Boeringer Ingelheim. B. S. Lewis:consultant/advisory board Bayer Healthcare, Merck, andBristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer and research grants fromAstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Merck/Schering-Plough, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer. D. W. Weaver: none. G. Brandrup-Wognsen:employee of AstraZeneca; equity ownership in AstraZe-neca. S. R. Stevens: none. A.Himmelmann: reports being anemployee of AstraZeneca. L. Wallentin: research grantsfrom AstraZeneca, Merck & Co, Boehringer-Ingelheim,Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline; consul-tant for Merck & Co, Regado Biosciences, Evolva, Portola,C.S.L. Behring, Athera Biotechnologies, Boehringer-Ingel-heim, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-MyersSquibb/Pfizer; lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-

480 Brilakis et alAmerican Heart Journal

September 2013

Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline,and Merck & Co; honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim,AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, GlaxoSmithK-line, and Merck & Co; travel support from Bristol-MyersSquibb/Pfizer. S. K. James: institutional research grant andhonoraria from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; advisory board member for AstraZeneca, EliLilly, and Merck; honoraria from The Medicines Company.

References1. Brilakis ES, Hernandez AF, Dai D, et al. Quality of care for acute

coronary syndrome patients with known atherosclerotic disease:results from the Get With the Guidelines Program. Circulation 2009;120:560-7.

2. Brilakis ES, de Lemos JA, Cannon CP, et al. Outcomes of patients withacute coronary syndrome and previous coronary artery bypassgrafting (from the Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and InfectionTherapy [PROVE IT-TIMI 22] and the Aggrastat to Zocor [A to Z]trials). Am J Cardiol 2008;102:552-8.

3. Shah SJ, Waters DD, Barter P, et al. Intensive lipid-lowering withatorvastatin for secondary prevention in patients after coronary arterybypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1938-43.

4. Bhatt DL, Chew DP, Hirsch AT, et al. Superiority of clopidogrel versusaspirin in patients with prior cardiac surgery. Circulation 2001;103:363-8.

5. Chen L, Theroux P, Lesperance J, et al. Angiographic features of veingrafts versus ungrafted coronary arteries in patients with unstableangina and previous bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28:1493-9.

6. Lichtenwalter C, de Lemos JA, Roesle M, et al. Clinical presentation andangiographic characteristics of saphenous vein graft failure afterstenting: insights from the stenting of saphenous vein grafts trial. J AmColl Cardiol Intv 2009. in press.

7. Brilakis ES, Lichtenwalter C, de Lemos JA, et al. A randomized-controlled trial of a paclitaxel-eluting stent vs a similar baremetal stent insaphenous vein graft lesions. The SOS (Stenting Of Saphenous VeinGrafts) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:919-28.

8. Ellis SG, Brener SJ, DeLuca S, et al. Latemyocardial ischemic events aftersaphenous vein graft intervention–importance of initially “nonsignifi-cant” vein graft lesions. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:1460-4.

9. Mehta RH, Honeycutt E, Peterson ED, et al. Impact of internalmammary artery conduit on long-term outcomes after percutaneousintervention of saphenous vein graft. Circulation 2006;114:I396-401.

10. Abdel-Karim AR, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Percutaneous interventionof acutely occluded saphenous vein grafts: contemporary techniquesand outcomes. J Invasive Cardiol 2010;22:253-7.

11. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrelin patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1045-57.

12. James S, Akerblom A, Cannon CP, et al. Comparison of ticagrelor,the first reversible oral P2Y(12) receptor antagonist, with clopidogrelin patients with acute coronary syndromes: rationale, design, andbaseline characteristics of the PLATelet inhibition and patientOutcomes (PLATO) trial. Am Heart J 2009;157:599-605.

13. Waters DD, Walling A, Roy D, et al. Previous coronary artery bypassgrafting as an adverse prognostic factor in unstable angina pectoris.Am J Cardiol 1986;58:465-9.

14. Wiseman A, Waters DD, Walling A, et al. Long-term prognosis aftermyocardial infarction in patients with previous coronary arterybypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988;12:873-80.

15. Kleiman NS, Anderson HV, Rogers WJ, et al. Comparison of outcomeof patients with unstable angina and non-Q-wave acute myocardialinfarction with and without prior coronary artery bypass grafting(Thrombolysis in Myocardial Ischemia III Registry). Am J Cardiol1996;77:227-31.

16. Mathew V, Berger PB, Lennon RJ, et al. Comparison of percutaneousinterventions for unstable angina pectoris in patients with and withoutprevious coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:931-7.

17. Labinaz M, Kilaru R, Pieper K, et al. Outcomes of patients with acutecoronary syndromes and prior coronary artery bypass grafting:results from the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in unstable angina:receptor suppression using integrilin therapy (PURSUIT) trial.Circulation 2002;105:322-7.

18. Servoss SJ, Wan Y, Snapinn SM, et al. Tirofiban therapy for patientswith acute coronary syndromes and prior coronary artery bypassgrafting in the PRISM-PLUS trial. Am J Cardiol 2004;93:843-7.

19. Boatman DM, Saeed B, Varghese I, et al. Prior coronary arterybypass graft surgery patients undergoing diagnostic coronaryangiography have multiple uncontrolled coronary artery disease riskfactors and high risk for cardiovascular events. Heart Vessels 2009;24:241-6.

20. Gurfinkel EP, Perez de la Hoz R, Brito VM, et al. Invasive vs non-invasive treatment in acute coronary syndromes and prior bypasssurgery. Int J Cardiol 2007;119:65-72.

21. Fitzgibbon GM, Kafka HP, Leach AJ, et al. Coronary bypass graft fateand patient outcome: angiographic follow-up of 5,065 grafts relatedto survival and reoperation in 1,388 patients during 25 years. J AmColl Cardiol 1996;28:616-26.

22. Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versusaspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl JMed 2006;354:1706-17.

23. Fox KA, Mehta SR, Peters R, et al. Benefits and risks of thecombination of clopidogrel and aspirin in patients undergoingsurgical revascularization for non-ST-elevation acute coronarysyndrome: the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrentischemic Events (CURE) Trial. Circulation 2004;110:1202-8.

24. Brilakis ES, Rao SV, Banerjee S, et al. Percutaneous coronaryintervention in native arteries versus bypass grafts in prior coronaryartery bypass grafting patients a report from the national cardio-vascular data registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2011;4:844-50.