Cutaneous Lesions of the Canine Scrotum

-

Upload

luciana-diegues -

Category

Documents

-

view

652 -

download

6

Transcript of Cutaneous Lesions of the Canine Scrotum

-

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd 63

Veterinary Dermatology

2002,

13

, 6376

Blackwell Science, Ltd

Original Artical

Review Cutaneous lesions of the canine scrotum

ROSARIO CERUNDOLO* and PAOLA MAIOLINO

*Dermatology Unit, The Royal Veterinary College, Hawkshead Lane, North Mymms, Hatfield AL9 7TA, UK, Dipartimento di Scienze Cliniche Veterinarie, Sezione di Clinica Medica, Facoltadi Medicina Veterinaria,

Universita

degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Napoli, Italy; Dipartimento di Patologia, Profilassi and Ispezione Degli Alimenti, Sezione di Anatomia Patologica, Facolta

di Medicina Veterinaria Universita Degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Napoli, Italy

(

Received

15

December

2000;

accepted

29

March

2001)

Abstract

Scrotal lesions are uncommon and often present a diagnostic challenge. In the veterinary literature thereare no texts devoted to this subject. This study reviews and illustrates canine scrotal lesions following an aetiologicallayout with the aim of facilitating clinical identification and diagnosis. Infectious, immune-mediated, endocrinological andneoplastic conditions are the most commonly reported causes of scrotal lesions in the dog. They may affect the scrotumonly or other parts of the body as well. The clinical presentation of the lesions, the presence of primary or secondary lesionsand the presence of clinical signs of systemic disease may help in obtaining a diagnosis. In some cases further investi-gations are necessary to reach a definitive diagnosis. Histopathology aids in understanding pathological reactions ofthe scrotal skin but unfortunately this is not commonly carried out and few reports in the literature include histopa-thology. The list of conditions given in this review is not exhaustive and other, more rare, diseases may be encountered.

Keywords

:

dermatosis, dog, scrotum, skin.

INTRODUCTION

In small animal practice scrotal skin lesions are un-common. When they occur, understanding their causeis sometimes a challenge for the clinician. Little informa-tion specific to the scrotum is available in the veterinaryliterature. The aim of this review is to provide a guidethat will be of value in clinical diagnosis; therapy of theseconditions and diseases of the testes are not considered.

Many dermatological diseases and systemic disordersmay present only scrotal lesions and determining theiraetiology is the best way of achieving a rational thera-peutic plan. A thorough history, general physicalexamination to identify abnormalities elsewhere inthe body, and a proper examination of the scrotum byinspection and palpation are fundamental. Appropriatecomplementary tests, including a biopsy of the scrotum,should be carried out. Histopathology of the scrotalskin has been reported infrequently in the literature,and thus the histopathological descriptions of many ofthe conditions considered in this review refer to theskin of the general body surface.

ANATOMY AND HISTOLOGY

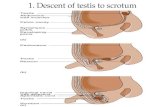

The canine scrotum is a membranous pouch dividedinto two cavities by a median septum and consisting of

two layers: the skin and the dartos. The skin is wrinkled,pigmented, covered with a fine and variable density ofhairs, and richly supplied with sweat glands. Theepidermis is thick, with marked rete ridges and thedermis contains numerous large smooth muscle bundles.

1

The dartos forms a common lining for both halves ofthe scrotum and contributes to the scrotal septum. Thescrotum contains the testes, the epididymides, thedistal part of the spermatic cord with its associatedspermatic fascia and vaginal tunics, and the distalcremaster muscle (Fig. 1). The external pudendal arteryis the main blood vessel to the scrotum and the veinsparallel the arteries. Lymphatic vessels drain to thesuperficial inguinal lymph nodes.

2

The scrotum is involved in the thermoregulation of thetestes. The temperature in the scrotum is lower than thatof the body core to prevent degeneration of the semini-ferous tubules of the testes. Two mechanisms are involved.The first is the cooling of the arterial blood by heat ex-change with the adjacent veins. The second is due to theactivity of the external cremaster and tunica dartos musclesthat allow the testis to be moved away from or closer tothe body depending on the external temperature.

3

SCROTAL DISEASES

Careful clinical examination of scrotal skin lesions isimportant to achieve a correct diagnosis. Many diseasesmay show only scrotal lesions (Table 1). Skin diseasesaffecting the scrotum can present a multifocal or diffusepattern of lesions (Table 2) which may be helpful in

Correspondence: Rosario Cerundolo, Department of Clinical Studies,School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania; 3900Delancey Street, Philadelphia, PA19104, USA.

VDE263.fm Page 63 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

64 R. Cerundolo and P. Maiolino

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd,

Veterinary Dermatology

,

13

, 6376

establishing a correct differential diagnosis (Table 3). Inthis review, a brief description of each disease and itseffects on the scrotum is given, based on aetiologicalcauses. Full descriptions and therapeutic managementof the diseases are given elsewhere.

1,4,5

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

Superficial pyoderma involves the epidermis and follicularepithelium, whereas deep pyoderma involves the dermisand often the subcutaneous tissues. These infections areusually caused by

Staphylococcus intermedius

, but otherbacteria may be involved. Microorganisms may beintroduced by local trauma, by bruising or scratching.Often deep infection follows inappropriate or inadequateantibiotic treatment of a superficial infection or ifunderlying diseases are still present. The primary pre-senting lesions are papules and pustules but latersecondary lesions may occur at many sites includingthe scrotum (Fig. 2). In deep infections, the lesions varyboth in depth and severity.

4

Constant licking of thescrotum may extend bacterial infection to the under-lying testicle.

6

Cytology of pustules shows the presenceof neutrophils and bacteria. Histopathology of super-ficial pyoderma shows a neutrophilic intraepidermalpustular dermatitis and/or a superficial folliculitis,

Figure 1. Structure of the scrotum and testicle.

Table 1. Conditions that may affect only the scrotal skin

BabesiosisBrucellosisContact dermatitisCuterebra emasculator infestationErysipelothrix rhusiopathiae infectionFixed drug eruptionFrostbiteHyperandrogenismIncorrect castrationNeoplasiaProtothecosisRocky Mountain spotted feverSunburnTrauma

Table 2. Differential diagnosis of multifocal and diffuse scrotal lesions

Multifocal lesions Diffuse lesions

Blastomycoses Pyoderma AtopyCandidiasis Sporotrichosis BabesiosisCuterebra emasculator infestation Sterile pyogranuloma BrucellosisDermatophytosis Metabolic epidermal necrosis Contact dermatitisDiscoid lupus erythematosus Systemic histiocytosis Food hypersensitivityEctoparasites Systemic lupus erythematosus FrostbiteEhrlichiosis Toxic epidermal necrolysis Keratinization defectsErysipelotrix rhusiopathiae infection Trauma Incorrect castrationErythema multiforme Uveodermatological syndrome LeishmaniosisFixed drug eruption Vitiligo Lethal acrodermatitisHyperandrogenism Zinc-responsive dermatosis Lupoid dermatosisIschaemic dermatopathy ProtothecosisMalassezia pachydermatis dermatitis Rocky Mountain spotted feverNeoplasia SunburnPemphigus complex Thallium toxicosis

VDE263.fm Page 64 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd,

Veterinary Dermatology

,

13

, 6376

Canine scrotal lesions 65

while in deep pyoderma folliculitis, furunculosis,nodular to diffuse dermatitis, and panniculitis areobserved.

1,7

Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae is an uncommon causeof bacteraemia, bacterial endocarditis and septic arthritisin dogs. Crawford & Foil described erythematous andoedematous skin lesions with pinpoint haemorrhagiculcers on the scrotal skin in a 9-month-old GoldenRetriever.

8

Blood culture is necessary for diagnosis.Histopathology shows a vasculitis that can be systemicand is characterized by the involvement of arterioles,venules and capillaries.

8

Brucellosis in dogs has been reported to be causedby

Brucella canis

, which is usually transmitted throughoronasal, conjunctival or venereal contact with an

infected dog. It usually causes testicular atrophy,epididymitis, prostatitis and sometimes scrotal derma-titis.

4,9

The lesions appear 12 weeks after intravenousinoculation or 35 weeks after oral inoculation of

B. canis

and it is likely that the scrotal dermatitis iscaused mainly by staphylococci as a consequence ofpersistent licking of the scrotum over painful epidi-dymides.

10

However, Schoeb & Morton describedscrotal lesions, caused by

B. canis

itself invading thescrotum from within, with several discrete, raw, depressedareas up to 1 cm with subsequent draining of fluidfrom the ulcers (Fig. 3).

11

Serological investigationsand bacteriological culture are diagnostic. Histopa-thology shows a nodular to diffuse pyogranulomatousand lymphocytic dermatitis.

12,13

Table 3. Differential diagnosis of scrotal skin diseases according to pattern of lesions

(a) Erythema, macules, papules, crusts and scalesAtopy Food hypersensitivity Sterile pyogranulomaBabesiosis Frostbite SporotrichosisBlastomycoses Keratinization defects Metabolic epidermal necrosisBrucellosis Leishmaniosis Systemic lupus erythematosusCandidiasis Lethal acrodermatitis Systemic histiocitosisContact dermatitis Lupoid dermatosis Thallium toxicosisDermathophytosis Malassezia pachydermatis dermatitis Toxic epidermal necrolysisEctoparasites Neoplasia TraumaErysipelothrix rhusiopathiae infection Pemphigus complex Zinc-responsive dermatosisErythema multiforme PyodermaFixed drug eruption Sunburn

(b) Crusts and ulcerationAtopy Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae infection ProtothecosisBlastomycoses Erythema multiforme SporotrichosisBrucellosis Fixed drug eruption Metabolic epidermal necrosisCandidiasis Food hypersensitivity Systemic lupus erythematosusCuterebra emasculator infestation Ischaemic dermatopathy Sterile pyogranulomaContact dermatitis Neoplasia Systemic histiocitosisDiscoid lupus erythematosus Pemphigus complex Toxic epidermal necrolysis

(c) HyperpigmentationAtopy Food hypersensitivity PyodermaContact dermatitis Hyperandrogenism Vascular hamartoma

(d) Oedema and sloughingCuterebra emasculator infestation Incorrect castration Testicular torsionFrostbite Rickettiosis Trauma

Figure 2. Erythema and pustule formation in superficial staphylococcalinfection. Figure 3. Oedema, erythema and ulceration of the scrotum in Brucella

canis infection (reproduced courtesy of C. Tieghi, Varese, Italy).

VDE263.fm Page 65 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

66 R. Cerundolo and P. Maiolino

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd,

Veterinary Dermatology

,

13

, 6376

RICKETTSIAL INFECTIONS

Ehrlichiosis, a tick-borne disease caused by

Ehrlichia

spp., is characterized by a variety of clinical syndromes.In the subclinical and chronic phases of

E. canis

infec-tion some dogs may develop scrotal oedema.

14

Detec-tion of the morula inside a monocyte in a blood smearand serological investigation are diagnostic.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a tick-borne, zoonotic disease caused by

Rickettsia rickettsii

.Some dogs may present with scrotal erythema, oedemaand ulceration.

4

They often have a stiff gait and arereluctant to walk. Necrosis and sloughing of the oede-matous scrotum may follow (Fig. 4).

15,16

Serologicalinvestigations are diagnostic.

Histopathology in ehrlichiosis and RMSF shows avasculitis.

1,7,8

FUNGAL INFECTIONS

Dermatophytosis is caused by fungi of the genera

Microsporum

and

Trichophyton

, which are transmittedby contact with infected hair or scales derived fromother animals or their environment. The clinical signsare circular patches of alopecia with variable scaling,or diffuse erythema with fine follicular papules,scales and crusts. The signs are highly variable and maybe localized or generalized with associated bacterialinfection.

4

Diagnosis is based on direct microscopicalexamination and cultures of plucked hairs and scrapings.Histopathology shows variable acanthosis, ortho- andparakeratotic hyperkeratosis which extend into thefollicular infundibula, and neutrophilic folliculitis andfurunculosis in more advanced lesions. Dermatophytesmay be seen in or around protruding hairs or occasionallyfree within epidermal keratin.

1,5

Candida

spp. dermatitis is a rare infection most com-monly caused by the yeast

C. albicans

, which may causesuperficial or deep infection. It is usually secondaryto trauma, excessive moisture, debilitation, systemicdiseases, use of antibiotics and, in immunosuppresseddogs, to prolonged antibacterial, steroid and immuno-

suppressive agents. The superficial infections are oftengeneralized. The scrotal lesions are moist, eroded,ulcerated, crusty and pruritic.

17,18

Cytology shows thepresence of numerous ovoid yeasts. Histopathologyshows a massive parakeratotic hyperkeratosis with asevere neutrophilic intraepidermal pustular dermatitis.

1

Malassezia

pachydermatis dermatitis is caused byyeasts commonly found on normal skin but predispos-ing factors, including breed, may cause increasedmultiplication that leads to disease. Skin lesions arefrequently observed in intertriginous areas such as theventral neck, axilla, inguinal area and the scrotum.Clinical signs include pruritus, erythema and thepresence of greasiness, scales and crusts.

19

Cytologyshows the presence of numerous monopolar buddingyeasts. Histopathology reveals a hyperplastic, superficial,perivascular to interstitial dermatitis with diffuse lym-phocytic exocytosis and epidermal spongiosis.

1

Sporotrichosis is caused by the ubiquitous fungus,

Sporothrix schenckii

, which exists as a saprophyte insoil and organic debris. Clinical signs are more oftenlocalized to the skin including the scrotum, subcutane-ous tissues and lymphatics.

20

Lesions are multiplefirm nodules and ulcerated plaques that may developdraining tracts. Cytological examination of materialaspirated from the lesions and fungal culture are notalways diagnostic, as the yeasts are rarely found in dogs,and a serological test is more useful. Histopathologyshows nodular to diffuse pyogranulomatous dermatitisand panniculitis.

1,5,7

Blastomycosis is a chronic granulomatous suppurat-ive systemic mycosis caused by inhalation of the sporesof

Blastomyces dermatitidis

. The cutaneous form isusually a manifestation of the disseminated diseaseand presents as single or multiple papules, nodules ordraining tracts exuding a seropurulent material.

4,21

Protothecosis is a systemic mycosis caused by

Pro-totheca wickerhamii

a ubiquitous, saprophytic achloro-phyllous alga that can cause disseminated infection or skinlesions via wound contamination. The cutaneous lesionsare papules, nodules and ulcers. Primary scrotal involve-ment has been reported in a Collie with scrotal swelling,ulceration (Fig. 5) and secondary generalized lesions.

22

Figure 4. Necrosis and sloughing of the lower part of the scrotum inRickettsia rickettsii infection.

Figure 5. Erythema and ulceration in protothecosis (reproducedcourtesy of P. Ginel, Cordoba, Spain).

VDE263.fm Page 66 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd,

Veterinary Dermatology

,

13

, 6376

Canine scrotal lesions 67

Cytological examination of material aspirated from thelesions is diagnostic and culture can confirm the diagnosis.

Histopathology in blastomycosis and protothecosisshows a superficial and deep pyogranulomatous dermatitiswith abundant microorganisms in most cases.

1,7,22

PROTOZOAL INFECTIONS

Leishmaniosis is caused by protozoa of the genus

Leishmania

that are transmitted by bloodsuckinginsects of the genus

Phlebotomus

or

Lutzomia

. Theorganism is present in macrophages and the infectioncauses a chronic systemic disease. Cutaneous lesionswith excessive scaling (Fig. 6) and ulcers are commonlyseen.

23

Cytological examination of aspirates from thelymph nodes or the bone marrow and serologicalinvestigations are diagnostic. Histopathology showsorthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and a superficial anddeep perivascular dermatitis characterized by histio-cytes and small numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cellsand neutrophils. Numerous amastigotes are presentwithin the macrophages and some are found free in thetissue.

1

Babesiosis is a tick-borne disease caused by

Babesia

spp., which parasitize red blood cells. The clinical signsvary and are peracute, acute or chronic. In severelyaffected dogs, thrombocytopenia may produce haem-orrhagic macules on the scrotum.

24,25

Cytological exam-ination of blood smears and serological investigationsare diagnostic. Histopathology shows a neutrophilicvasculitis, mixed perivascular inflammatory infiltrateand dermal oedema.

24,25

PARASITIC INFESTATIONS

Cuterebra

spp. are flies that may rarely affect the dog

26

but no recent reports of scrotal infestation are avail-able.

Cuterebra emasculator

may affect the scrotum ofwild animals as well as dogs in some regions of theUnited States. The fly deposits its eggs by piercing

the scrotum and the developing larva projects throughthe puncture while the greater portion is buried andsurrounded by a zone of inflammatory tissue. The scro-tum becomes oedematous and a round firm mass maybe palpated. It apparently gives the animal no discomfortunless the parasite causes an abscess with followingnecrosis of the scrotum, inflammation and dislocationof the testes.

6,27,28

Parasites such as

Sarcoptes

spp. and

Demodex

spp.may also infest the scrotal skin. The presence of pruri-tus with erythema, papules and crusts also affectingother areas of the body should lead to a suspicion ofsarcoptic mange. In demodicosis papules, pustules andcomedones with hyperpigmentation commonly affectthe face, limbs and inguinal area. Larvae of

Peloderastrongyloides

or hookworms may also infest the scrotalskin causing erythema. Areas of the body in contactwith the ground are more commonly affected. Skinscrapings and hair pluckings are usually diagnostic.

4

IMMUNE-MEDIATED DISEASES

Atopy is a hypersensitivity disease in which the patientbecomes sensitized to environmental antigens, withIgE or IgGd production. The age of onset variesfrom 6 months to 7 years and the clinical signs may beseasonal or nonseasonal depending on the allergensinvolved. Skin lesions are usually localized on the face,axillae, limbs and ventrum, involving also the scrotum.Initially, there are slightly erythematous macules,usually associated with pruritus, salivary staining andsigns of self-trauma, leading to secondary bacterialand yeast infections. Subsequently, alopecia, hyperpig-mentation, lichenification and seborrhoea may develop.

4

Thickening of the scrotal skin may interfere with thescrotums ability to control testicular temperature andmight contribute to thermal testicular degeneration.Diagnosis is based on Willemses criteria and exclusionof other hypersensitivity disorders.

29

Intradermal andserological tests may help to understand which antigenmay be involved in this condition

.

Histopathologyis not particularly useful in the diagnosis of atopy.However, the most consistent lesion is a superficialperivascular dermatitis with the presence of mono-nuclear cells, and acanthosis, diffuse superficial dermaloedema and vasodilatation. The follicular epitheliumis usually hyperplastic and may be hyperkeratotic.

1,7

Food sensitivity is an abnormal clinical response toan ingested food and can be manifested by cutaneousand/or gastrointestinal signs. Skin lesions, primary orsecondary, are usually associated with pruritus andmay be localized on the face, limbs, axillae and ventrum,including the scrotum. Secondary bacterial and yeastinfections usually contribute to the severity of theskin lesions.

3

A restriction diet, based on a source ofprotein and carbohydrate not fed previously, is essen-tial to diagnose this condition. Histopathology is notspecific and shows a superficial and deep perivasculardermatitis.

7

Figure 6. Diffuse exfoliative dermatitis in leishmaniosis. Note thelarge scales.

VDE263.fm Page 67 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

68 R. Cerundolo and P. Maiolino

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd,

Veterinary Dermatology

,

13

, 6376

Pemphigus foliaceus

30

(Fig. 7) and pemphiguserythematosus

31,32

are characterized by gradual onsetof a vesiculobullous or pustular dermatitis. They usuallyaffect the bridge of the nose, ears, footpads and lessfrequently the scrotum, which may show erosive andulcerative lesions. Generalized lesions sometimes occurin pemphigus foliaceus. Cytological examination of thepustule contents shows neutrophils and acanthocytes.Histopathology shows a subcorneal or intragranularvesiculopustular dermatitis with acantholytic keratinocytes.An important finding is hair follicle involvement.

1,33

Pemphigus vulgaris is a rare disease characterized byan acute onset in association with systemic signs. Thedisease presents as vesiculobullous, erosive, ulcerativelesions affecting the oral cavity, the mucocutaneousjunctions, the skin and the scrotum. Histopathologyshows a suprabasilar acantholysis with resultant clef-ting, and the formation of vesicles or bullae. The basalcells of the epidermis, although separated from eachother by loss of their intercellular bridges, remainanchored to the basement membrane zone like a rowof tombstones. The process may extend into the hairfollicle epithelium.

1,6,33

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a disease charac-terized by depigmentation and ulceration with crustsaffecting the planum nasale and lips, and less com-monly the periocular area, pinnae, distal limbs and thescrotum (Fig. 8).

34

Histopathology shows a heavy

band of lymphocytes and plasma cells along the dermo-epidermal junction, around hair follicles and adnexalglands. Hydropic degeneration of the basal cells andapoptosis of individual keratinocytes during the acute andsubacute phase, and marked pigmentary incontinencemay also be present.

1,7,33

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a rare disorder witha multifactorial aetiology. The clinical signs includepolyarthritis, fever, proteinuria and anaemia. Skin lesionsmay be extremely diverse and multifocal, or generalized,sometimes involving the scrotum and leading to ulcera-tion. The diagnosis in dogs, as well as in humans, shouldmeet four of the criteria established by the AmericanRheumatism Association.

35

Histopathology shows a mildto moderately intense lymphocytic interface dermatitiswith hydropic degeneration and necrosis of the basal celllayer of the epidermis with formation of colloid bodies.

1,7,33

Fixed drug eruption is a rare reaction potentiallycaused by any drug administered topically or system-ically. Certain drugs (sulphonamides, penicillins andcephalosporins) are more frequently reported to pro-duce hypersensitivity-like reactions.

4

Cutaneous drugreactions can mimic virtually any dermatosis, however,the lesions resolve when the drug is withdrawn andreturn when the drug is reinstated.

4

In particular,diethylcarbamazine, 5-fluorocytosine and aurothioglu-cose have been reported to cause scrotal pruritus withsubsequent self-trauma and well-demarcated scrotalulceration.

3638

Histopathological findings are variablebut may include an interface dermatitis composed oflymphocytes and plasma cells, with superficial and deepperivascular dermatitis.

35

Granulomatous vasculitis hasalso been reported in the scrotal skin of one dog.

1

Erythema multiforme is a condition that has beenassociated with infections, drugs, neoplasia and connec-tive tissue diseases. The acute skin lesions are variableand include erythematous macules, papules, urticarialplaques and vesicles. Van Hees

et al

.

39

described scrotallesions in a dog with generalized erythema, maculesand wheals following 20 days of levamisole for the treat-ment of dirofilariasis. Histopathology shows a severereaction in which numerous apoptotic keratinocytesare present at all levels of the epidermis and withinthe adnexal epithelia. Lymphocytes infiltrate into theaffected epidermis, and may closely surround the apop-totic keratinocytes, a process known as satellitosis.

7

Toxic epidermal necrolysis has been also associatedwith drug administration, toxins, tumours and othersystemic disorders. Skin findings are characterized byvesiculobullous lesions with necrosis and ulceration.Fever, anorexia and lethargy are common systemicsigns. Histopathology shows a cell-poor subepidermalvesicular dermatitis with full thickness coagulativeepidermal necrosis that may extend into the externalroot sheath of the hair follicle. Separation of thenecrotic epidermis occurs at the dermoepidermal junc-tion and leads to subepidermal vesiculation. Dermalinflammation is minimal or absent.

1,7

Ischaemic dermatopathy has been reported followingrabies vaccination.

40

Various degree of focal or multifocal

Figure 7. Multiple erythematous brown crusted lesions in pemphigusfoliaceus.

Figure 8. Erythema and erosion in cutaneous lupus erythematosus(reproduced courtesy of C. Curtis, London, UK).

VDE263.fm Page 68 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd,

Veterinary Dermatology

,

13

, 6376

Canine scrotal lesions 69

alopecia, erosions, ulcers, crusts and hyperpigmentationmay affect the face pinnae, foot pads, tail, the skinoverlying the bony prominences and the scrotum.

40

Histopathology of alopecic areas shows follicular atrophy;lymphocitic perivascular inflammation and vasculitisare present in deep dermis and panniculus.

40

CONTACT DERMATITIS

This disease is conventionally divided into irritant andhypersensitivity reactions although both conditions arelikely to be involved to some extent in every instance.

41

Irritant contact dermatitis is a reaction due speci-fically to the irritating effects of a substance with noimmune basis. It may be caused by many strong irritants(such as acids and alkalis) or other substances, includingselenium and povidone iodine,

42

that injure the scrotalskin following a single exposure. Other substances,such as soap, detergents and medicated shampoosrequire repeated contact to cause injury. In both cases,a secondary bacterial infection may follow.

4,43

Contact hypersensitivity is a type IV reaction andonly a few dogs in an exposed population may developclinical signs of the disease. Repeated or continuouschallenge is necessary for sensitization to occur and forthe signs to develop. The lesions may be common indogs kennelled on concrete floors. Sometimes thelesions may be seasonal if plant allergens are involved.Numerous substances have been incriminated includingcement, synthetic textiles, soil cleaning products andtopical drugs.

44

The clinical signs of the two syndromes are similarand differentiation between them is not always easy. Ifmultiple dogs in a kennel are affected, primary irritantcontact dermatitis is much more likely than contacthypersensitivity. Lesions are observed not only on thescrotum but at all potential contact sites especially ifthe animal lies on or walks over the responsible sub-stance. The primary lesions are patches of erythema,macules and papules with serous exudation followedby formation of crusts, excoriation and hyperpigmenta-tion. Intense pruritus may promote severe self-trauma.A detailed history and avoidance of contact with thesuspected agents will help to identify the cause of thecondition. In contact hypersensitivity, patch tests maybe used. Histologically, it may not be possible to distin-guish between irritant contact dermatitis and contacthypersensitivity, particularly in more advanced lesions.A superficial perivascular dermatitis, spongiotic in theacute phase and hyperplastic in the chronic phase, isevident.

1,4

ENDOCRINE DISEASES

Hyperandrogenism, is a rare disease which may becaused by an interstitial cell tumour of the testis. It isassociated with perianal gland and tail gland hyper-plasia and macular pigmentation of the scrotal skin. In

idiopathic hyperandrogenism, the macular melanosisfades slowly over a 6-month period.

45

An enlarged testisor high level of blood testosterone is diagnostic.

Sertolis cell tumour is the most common of the testi-cular tumours. Symmetrical alopecia, gynecomastia,pendulus prepuce and inguinal and scrotal hyper-pigmentation are common clinical findings. An enlargedor retained testicle is suggestive of this condition. Bloodoestrogen may be elevated.

Metabolic epidermal necrosis (superficial necrolyticdermatitis, hepatocutaneous syndrome) has been asso-ciated with hepatic or pancreatic disease in old dogs.The pathogenesis of this disease is undetermined. Thepresence of a high glucagon concentration due to aglucagonoma may be the cause of the decrease in theplasma amino acid levels which can occur prior to theappearance of skin lesions.

46,47

Scrotal lesions maysometimes be the first sign noted.

48

Erythema and scalingfollowed by erosion or ulceration and crusting with stickyexudate are observed (Fig. 9).

49,50

Little

et al

.

49

describeda case in which scrotal lesions developed followinghepatic injury owing to the ingestion of mouldy biscuitscontaining a mycotoxin. Histopathology shows a perivas-cular dermatitis with diffuse parakeratotic hyperkeratosisand a band of hydropic, pale-staining keratinocytes in theupper half of a usually acanthotic stratum spinosum.Both intra- and intercellular oedema contribute toepidermal pallor. As these cells degenerate, clefts andvesicles may form in the outer stratum spinosum.

1,7

HEREDITARY DISEASES

Lethal acrodermatitis of the Bull Terrier is a rare,familial disease in which a defect in zinc metabolism atthe cellular level has been suspected. Affected animalsdevelop, early in life, crusted and ulcerated skin lesionson the face, limbs and scrotum with cracking of thefootpads and paronychia. Breed predisposition and theclinical findings are suggestive of this condition.Histopathology shows diffuse, parakeratotic hyperk-eratosis and folliculitis.

4,51

Lupoid dermatosis of the German Short-HairedPointer is presumed to be a hereditary disease. Scales

Figure 9. Erythema, crusts and ulceration in superficial necrolyticdermatitis (reproduced courtesy of E. Ferguson, London, UK).

VDE263.fm Page 69 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

70 R. Cerundolo and P. Maiolino

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd,

Veterinary Dermatology

,

13

, 6376

and crusts are initially localized on the face and ears,and then become generalized. Pyrexia is present andthe hocks and the scrotum are markedly pruritic.

52,53

Breed predisposition and clinical findings may beindicative of this condition. Histopathology showsan inflammatory interface dermatitis, orthokeratotichyperkeratosis and acanthosis with hyperpigmentationof the epithelium; similar findings are present in somefollicles.

1,52

Keratinization defects can be congenital (primaryseborrhoea, ichthyosis) or acquired (vitamin A-responsivedermatosis, sebaceous adenitis). The cutaneous lesions(seborrhoea, scales) are usually generalized involvingalso the scrotal skin.4 Sebaceous adenitis is an idio-pathic, probably hereditary, disease commonly seen inStandard Poodles but reported also in other breeds.54

The cutaneous changes are somewhat dependent onhaircoat type and breed. In short-haired breeds thelesions are circular with alopecia and scaling. In long-haired breeds alopecia may be patchy but is usuallymore generalized and the degree of scaling is verypronounced.4 Breed predisposition, clinical signs andthe presence of follicular casts are indicative of thiscondition. Histopathological findings are variabledepending on the severity of the lesions. Early lesionsshow granulomatous to pyogranulomatous dermatitis,whereas chronic lesions show a superficial perivasculardermatitis with prominent orthokeratotic or parakera-totic hyperkeratosis of epidermis and hair follicles.The sebaceous glands are progressively destroyed by agranulomatous reaction and are completely absent inthe final stages of the disease.7,54

ENVIRONMENTAL DISEASES

Traumatic lesions are uncommon despite the exposedlocation of the scrotum. Clinical signs depend on theseverity of the injury. Minor abrasions and lacerationssuch as those which occur in hunting dogs owing tothick vegetation, are initially undetected because of thepaucity of clinical signs.55 Severe lesions such as urinescalding may occur following burns or trauma whichlead the dog to a sedentary position or to incontinence.Inflammation with or without infection may be seen(Fig. 10) and the scrotum is sensitive to palpation. Theaffected animal frequently licks at scrotal wounds,causing further inflammation and possible infection.A stiff gait may be noted and the dog prefers to sit.Trauma to the parietal vaginal tunic of the testis canresult in orchitis with subsequent oedema and sloughingof the ventral scrotal skin.

Incorrect castration, carried out illegally by membersof the public by applying a rubber band to the base ofthe scrotum, may lead to ischaemia, necrosis and sub-sequent infection of the wound (K. V. Mason, personalcommunication).

Sunburn is caused by chronic exposure to strongsunlight and may occur commonly during the summerin dogs such as Dalmatians and white Bull Terriers.

Predisposed areas are the unpigmented, sparsely hairedskin of the flank, ventral abdomen and the scrotum(K. V. Mason, personal communication). Frequently, thecaudal aspect of the scrotum is affected and in the earlystages there is erythema and scaling. Crusts and even-tually ulceration may be seen as the lesion progress.Palpation of the area may reveal an uneven surfaceowing to the thickening of the skin. Continued exposureto sunlight may predispose to squamous cell carcinoma.5

Frostbite affecting the ears, tail tip and scrotum, mayoccur during cold weather particularly in those breedsin which the scrotal skin is sparsely covered by hair. Inmild cases only hyperaemia and oedema are observed,but in severe cases the skin may become pale owing tovasoconstriction and subsequent ischaemia. In severecases, the skin becomes necrotic and sloughs.56

Thallium toxicosis is a cumulative, general cellpoisoning normally caused by a rodenticide which wasused frequently in the past. Thallium may producesystemic toxicity and in the chronic form there is ageneralized alopecia with erythema and necrosis ofthe skin. The scrotal skin becomes erythematous,57

thickened and slightly oedematous with subsequentalopecia and scale formation.58 Histopathology showsmassive and diffuse parakeratotic hyperkeratosis thatextends into follicular infundibula. Marked spongiosisand/or intracellular oedema are evident at the surfaceand in the external root sheath epithelium. The super-ficial dermis shows oedema. Hair follicles are mostly incatagen or telogen.1

NUTRITIONAL DISEASES

Zinc-responsive dermatosis has been reported mostfrequently in Siberian Huskies and Alaskan Malamutesin which a poor or defective absorption of zinc hasbeen suspected.59 The onset of skin lesions frequentlyoccurs during puberty, although old dogs may also beaffected. They show erythema followed by alopecia,crusting and scaling around the mouth, chin, ears,eyes and, less frequently, the scrotum and the pre-puce.4 Clinical signs may be suggestive of this condi-tion but skin biopsy helps to confirm the diagnosis.

Figure 10. Oedema and erosion with diffuse erythema and a largebruise of the inguinal area following a road traffic accident.

VDE263.fm Page 70 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd, Veterinary Dermatology, 13, 6376

Canine scrotal lesions 71

Histopathology shows a superficial perivasculardermatitis with diffuse parakeratotic hyperkeratosis,acanthosis and dyskeratosis.1,5

PIGMENTARY DISORDERS

Hypopigmentation is a decreased amount of melaninin the epidermis and is associated with congenital oracquired defects in melanization such as occurs follow-ing trauma or chemical injuries. It may be also causedby an immune-mediated destruction of the melanocytes.Uveodermatological syndrome (Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada-like syndrome) is a rare, possibly autoimmune, diseasecharacterized by a concurrent granulomatous uveitisand progressive depigmentation with dermatitis of thehead and scrotum.60,61 Clinical findings are suggestive ofthis condition. Histopathology shows a lymphohistiocyticinterface dermatitis with parakeratotic hyperkeratosis,acanthosis and marked pigmentary incontinence.1,5

Vitiligo has been described in Belgian Tervurens inwhich a familial predisposition was reported, however,it may also affect other breeds causing progressivecutaneous depigmentation including of the scrotum(Fig. 11).4,62 Other clinical signs, as in uveodermato-logical syndrome, are absent in vitiligo. Histopathologyof depigmented skin reveals a mild interface accumu-lation of lymphocytes and macrophages in early lesionsand absence of melanocytes and melanin-containingkeratinocytes.5 Sites of dihidroxyphenylalanine oxidase(Dopa-oxidase) activity are absent. In vitiligo, thecutaneous depigmentation is not only an aestheticproblem but may also predispose to sunburn. Occa-sionally, spontaneous repigmentation may be observedwithout any treatment.

Hyperpigmentation is an excessive amount of melanindeposited within the epidermis and may be either

macular as in hyperandrogenism owing to testicularneoplasia (see above) and in vascular hamartoma (seelater), or diffuse as in chronic inflammatory diseases(hypersensitivity disorders) and hormonal dermatoses(Sertolis cell tumour). However, hyperpigmented maculesmust be differentiated from the normal patchy appear-ance of the scrotum in some dogs.

MISCELLANEOUS DISORDERS

Sterile pyogranuloma is a disease in which the aetiologyand pathogenesis are unknown, but an immune-mediatedpathogenesis is suspected.4 There are firm, nonpruriticpapules, plaques and nodules that may ulcerate on thehead, pinna, paws and scrotum.63 Histopathology showsnormal to moderately acanthotic epidermis with largeperifollicular granulomas or pyogranulomas, which areelongated and vertically orientated. They track hairfollicles but do not invade them.4

SCROTAL NEOPLASMS

Many cutaneous neoplasms may affect the scrotum eitheras primary localization or following metastasis.6466 Fine-needle aspiration biopsies and impression smears areuseful techniques to reach the diagnosis. Careful exam-ination and fine-needle aspiration of superficial lymphnodes, bone marrow biopsy, buffy coat examination anddiagnostic imaging investigations are necessary in somecases to rule out tumour metastases. Cutaneous neoplasmsare of epithelial, mesenchymal or melanocytic origin.

Epithelial tumours such as squamous cell carcinoma(SCC) (Fig. 12) and sweat gland adenocarcinoma (SGA)are usually solitary and circumscribed nodules. SCCmay be more common in dogs with unpigmented scrotalskin.64,6670 Histopathology of SCC shows a neoplasticproliferation composed of irregular cords and clumpsof epidermal cells infiltrating the underlying tissues.Large numbers of horn pearls and numerous mitoticfigures, sometimes atypical, are frequently found.64

Histopathology of SGA shows neoplastic tissue, extend-ing throughout the thickness of the skin with someinvasion of the dartos, composed of an irregular pro-liferation of epithelial cells usually arranged in thin

Figure 11. Patchy depigmentation of the lower part of the scrotumand prepuce in idiopathic vitiligo-like depigmentation.

Figure 12. Erythema and ulcerated nodules in squamous cellcarcinoma (reproduced courtesy of F. Albanese, Naples, Italy)

VDE263.fm Page 71 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

72 R. Cerundolo and P. Maiolino

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd, Veterinary Dermatology, 13, 6376

irregular cords with frequent formation of glandularspaces resembling sweat glands.64

Mesenchymal tumours characterized by the histo-logical presence of spindle cells (fibroblast origin) suchas fibrosarcoma, a malignant tumour, and myxoma, arare benign one, arise from fibroblasts and occur inadult dogs. The tumours are usually solitary, of variablesize, irregular and nodular in shape, poorly demarcatedand nonencapsulated.69,70 A scrotal myxoma arisingfrom subcutaneous fibroblasts has been reported.66

Histopathology shows immature fibroblasts which areusually fusiform, but they may be ovoid or stellate inshape, and have a variable amount of collagenous fibre.In fibrosarcoma, mitotic figures, sometimes atypical,are common and undifferentiated tumours may havemultinucleate giant cells and cells with bizarre shapes.1,4,5

Mesenchymal tumours characterized by the histo-logical presence of spindle cells (from blood vesselsendothelium) such as haemangioma, a benign neoplasm,and haemangiosarcoma, a malignant one, occur inadult and old dogs. In the former, the overlying epider-mis is usually alopecic and secondary ulceration mayoccur.5,66,70,71 The latter appears as a plaque or a soli-tary nodule. Histopathology shows blood-filled vascularspaces lined by single layer of well-differentiated flat-tened endothelial cells.4,5,66,72 In haemagiosarcoma,the neoplastic tissue is composed of immature elongateendothelial cells with round or ovoid nuclei which arevery hyperchromatic. Mitotic figures, sometimes atyp-ical, are common.4,5 Vascular hamartoma is believedto be a progressive vascular malformation rather thana true neoplasm. Adult and old dogs of breeds withpigmented scrotal skin are reported to have a higherincidence.69,73 It begins as single or multiple, hyperpig-mented macules consisting microscopically of collapsedcapillaries that progress to firm plaques as the capillariesbecome dilated with blood.5,69 The overlying epidermisbecomes thickened and is frequently ulcerated becauseof chronic licking, and there are repeated episodes ofprofuse bleeding. Histopathology shows acanthosisand increased melanin pigmentation with dermal fibrosisand a cavernous dilatation of blood vessels.5

Mesenchymal tumours characterized by the histo-logical presence of round cells also occur. Plasmacytomaoriginates from plasma cells and is found principally inadult dogs. It is usually solitary, circumscribed, raised,smooth, firm to soft, pink to red and dermal in local-ization, sometimes ulcerating.74 Histopathologyshows sheets or large nests of neoplastic cells withoval, round, indented or lobulated nuclei surroundedby a fine fibrovascular stroma and infiltrating thedermis and subcutis.1,74 Epitheliotropic lymphoma is atumour of T-cell origin and usually affects old dogs.Four different clinical syndromes may be seen: exfoli-ative erythroderma, mucocutaneous ulceration anddepigmentation, solitary or multiple cutaneous plaquesor nodules, and infiltrative and ulcerative oral mucosaldisease.4 The scrotum may be affected in the generalizedform characterized by pruritus, erythema and scaling,and the form with cutaneous plaques and/or nodules

(Fig. 13). Histopathology shows epidermal infiltratesof atypical lymphocytes, either single or in clusters,called Pautriers microabscesses. Lymphocytes vary insize and may have a hyperchromatic and convolutednucleus. Similar infiltration of neoplastic lymphocytesis also observed within the superficial dermis andwithin the epithelia of hair follicles and apocrine sweatglands. The adnexal involvement may precede epidermalinvolvement.1,5

Histiocytic tumours such as histiocytoma and benignfibrous histiocytoma are benign tumours originatingfrom Langerhans cells. Young dogs of pure breed arefrequently affected. The lesions appear as solitary, round,elevated, rapidly growing, alopecic, erythematous, dome-shaped nodules that may ulcerate.4,5,71,75 Histopathologyof the former tumour shows uniform sheets of pleo-morphic histiocytic cells infiltrating the dermis andsubcutis, and displacing the collagen fibres and adnexae.The neoplastic cells are round to ovoid in shape andhave large nuclei. The cytoplasm is pale staining andabundant. Mitotic figures are numerous.4,5 Histopa-thology of the latter shows a neoplastic proliferationcomposed of fibroblasts and histiocytes containingabundant and vacuolated cytoplasm. Lymphocytesand plasma cells are commonly present, especially atthe periphery of the masses.1,5 Cutaneous and systemichistiocytosis is an uncommon disease caused by a his-tiocytic proliferation of Langerhans cells. It has beendescribed in closely related Bernese Mountain Dogsbut also other breeds may be affected. Papules, plaquesand nodules that may ulcerate and have a crateriformappearance are commonly seen (Fig. 14). Histopatho-logy of the skin shows a nodular to diffuse infiltration ofcytologically normal histiocytes in the superficial anddeep dermis and panniculus adiposus. Histiocytic infil-tration of the scrotal skin is usually more diffuse andsevere and extends beyond the panniculus to involve thecommon vaginal tunica.76

Mast cell tumour is the most common scrotal neo-plasm in the dog.65,66,71,77,78 The scrotum may be hot,swollen and bruised following vasoactive amine releasefrom the mast cells. Usually the tumour occurs as awell-circumscribed solitary cutaneous nodule (Fig. 15)but it may also present as a single or diffuse, poorlydelineated oedematous swelling of the skin.69 Histopa-thology shows considerable variation of the tumourand a classification and grading system has been pro-posed based on the degree of cellular differentiation.

Figure 13. Diffuse erythema and ulceration in a case ofnonepitheliotropic lymphoma.

VDE263.fm Page 72 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd, Veterinary Dermatology, 13, 6376

Canine scrotal lesions 73

Sheets, cords or small clusters of more or less recogniz-able mast cells are seen associated with numerouseosinophils. Foci of tumour necrosis and collagenolysisare found.1,5

Transmissible venereal tumour is generally found insexually intact males affecting the external surface ofthe penis and the scrotum, which may appear swollenand reddened, with thin and shiny skin or ulcerat-ive lesions. The tumours metastasize especially inimmunosuppressed animals.66,79,80 Histopathologyshows round, ovoid or polyhedral cells with indistinctboundaries and poorly stained or clear cytoplasm.The nuclei are large, round and hyperchromatic withdistinctly marginal chromatin and large central nucleoli.The cells are in compact masses or sheets and some-times grow in rows, cords or loose in a delicate stroma.The type and number of infiltrating lymphocytesdepend on whether the tumour is in a progressive,steady, or regressive state.1,4

Melanoma is a neoplasm composed of melanin-producing cells. The incidence is highest in middle-aged dogs.69,71 The tumour is usually solitary and oftenmalignant.66,67 The gross appearance ranges fromblack macules to large, rapidly growing masses with asmooth appearance that may be amelanotic or darkbrown to grey or black in colour.69 Histopathologyshows intraepidermal and/or dermal tumour cellswith considerable variation in appearance (spindle,epithelioid and round cells) that are often recognized

by pigmentary content and arrangement in clusters ornests rather than by cellular characteristics. Mitoticfigures are usually rare in benign melanomas andextremely numerous in malignant melanomas.1,70

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Prof. David Lloydwho provided helpful suggestions and critical review ofthe manuscript and Dr Letizia Davino who drew Fig. 1.

REFERENCES

1. Yager, J.A., Wilcock, B.P. Color Atlas and Text of SurgicalPathology of the Dog and Cat. Dermatophatology andSkin Tumours. London: Wolfe, 1994.

2. Evans, H.E., Christensen, G.C. The urogenital system.In: Evans, H.E., ed. Millers Anatomy of the Dog, 3rd edn.Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1993: 50458.

3. Stabenfeld, G.H., Edqvist, L.E. In: Swenson, M.J.,Reece, W.O., eds. Dukes Physiology of Domestic Animals.Ithaca, NY: Comstock Publishing, 1993: 66577.

4. Scott, D.W., Miller, W.H., Griffin, C.E. Muller and KirksSmall Animal Dermatology, 6th edn. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders, 2000.

5. Gross, T.L., Ihrke, P.J., Walder, E.J. Veterinary Dermato-pathology. A Macroscopic and Microscopic Evaluationof Canine and Feline Skin Disease. St. Louis, MO: MosbyYear Book, 1992.

6. Barton, C.L. Diseases of the testes. In: Morgan, R.V., ed.Handbook of Small Animal Practice. New York: Church-ill Livingstone, 1988: 65560.

7. Yager, J.A., Scott, D.W. The skin and appendages. In:Jubb, K.V.F., Kennedy, P.C., Palmer, N., eds. Pathologyof Domestic Animals, Vol. 1, 4th edn. San Diego:Academic Press, 1993: 531738.

8. Crawford, M.A., Foil, C.S. Vasculitis: clinical syndromesin small animals. Compendium on Continuing Educationfor the Practicing Veterinarian 1989; 11: 40015.

9. George, L.W. Semen examination in dogs with caninebrucellosis. American Journal of Veterinary Research1979; 40: 158995.

10. Carmichael, L.E., Kenney, R.M. Canine brucellosis. Theclinical disease, pathogenesis and immune response.Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association1970; 156: 172634.

11. Schoeb, T.R., Morton, R. Scrotal and testicular changesin canine brucellosis: a case report. Journal of the AmericanVeterinary Medical Association 1978; 172: 598600.

12. Dawkins, B.G., Machotka, S.V., Suchmann, D. et al.Pyogranulomatous dermatitis associated with Brucellacanis infection in a dog. Journal of the American VeterinaryMedical Association 1982; 181: 14323.

13. Carmichael, L.E., Greene, C.E. Canine brucellosis. In:Greene, C.E., ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat.Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1990: 57384.

14. Troy, G.C., Forrester, S.D. Canine ehrlichiosis. In:Greene, C.E., ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat.Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1990: 40414.

15. Keenan, K.P., Buhles, W.C., Huxsoll, D.L. et al. Studieson the pathogenesis of Rickettsia rickettsii in the dog;clinical and clinicopathological changes of experimental

Figure 14. Circular crusts and scales with erythema in a case ofsystemic histiocytosis.

Figure 15. Ulcerated nodules and papules in a dog with a mast celltumour.

VDE263.fm Page 73 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

74 R. Cerundolo and P. Maiolino

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd, Veterinary Dermatology, 13, 6376

infection. American Journal of Veterinary Research 1977;38: 8516.

16. Greene, C.E., Breitschwerdt, E.B. Rocky Mountainspotted fever and Q fever. In: Greene, C.E., ed. InfectiousDiseases of the Dog and Cat. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders,1990: 41933.

17. Bourdeau, P., Chermette, R., Fontaine, J.J. Hyperkera-tose et candidose cutanee chez un chien. Etude dun cas.Recueil de Medicine Veterinaire 1984; 160: 8039.

18. Pichler, M.E., Gross, T.L., Krool, W.R. Cutaneous andmucocutaneous candidiasis in a dog. Compendium onContinuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian1985; 7: 22530.

19. Mason, K.V. Malassezia dermatitis and otitis. In: Kirk,R.W., Bonagura, J.D., eds. Current Veterinary TherapyXI. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1992: 5446.

20. Moriello, K.A., Franks, P., Delany-Lewis, D. et al.Cutaneouslymphatic and nasal sporotrichosis in a dog.Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association1988; 24: 6216.

21. Legendre, A.M. Blastomycosis. In: Greene, C.E., ed.Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. Philadelphia:W.B. Saunders, 1990: 66978.

22. Ginel, P.J., Perez, J., Molleda, J.M. et al. Cutaneousprotothecosis in a dog. Veterinary Record 1997; 140:6513.

23. Dereure, J., Espinel, I., Barrera, C. et al. Leishmaniasis inEcuador. 4. Natural infection of the dog by Leishmaniapanamensis. Annales de la Societe Belge de MedicineTropicale 1994; 74: 2933.

24. Carlotti, D.N., Pages, J., Sorlin, M. Skin lesion in caninebabesiasis. In: Ihrke, P.J., Mason, I.S., White, S.D., eds.Advances in Veterinary Dermatology, Vol. 2. Oxford:Pergamon Press, 1993: 22938.

25. Capelli, J.L., Ghernati, I., Chabanne, L. et al. La babesiosecanine, maladia a complexes immuns: a propos duncas de vascularite a manifestations cutanees. PratiqueMedicale et Chirurgicale de lAnimal de Compagnie 1996;31: 2319.

26. Roosje, P.J., Hendrix, W.H.L., Wisselink, M.A. et al. Acase of Dermatobia hominis infection in a dog in theNetherlands. Veterinary Dermatology 1992; 3: 1835.

27. Bloom, F. Scrotum. In: Pathology of the Dog and Cat.The Genitourinary System, with Clinical Considerations.Evanston, IL: American Veterinary Publications, 1954:25761.

28. Muller, G., Glass, A. Diseases of sexual organs. In:Diseases of the Dog and their Treatment. London: Bailliere,1937: 30320.

29. Willemse, T. Atopic skin disease. A review and a recon-sideration of diagnostic criteria. Journal of Small AnimalPractice 1986; 27: 7718.

30. Griffin, C.E. Diagnosis and management of primaryautoimmune skin disease: a review. Seminars in VeterinaryMedicine and Surgery (Small Animal) 1987; 2: 17385.

31. Scott, D.W., Walton, D.K., Slater, M.R. et al. Immuno-mediated dermatosis in domestic animals. Ten yearsafter Part I. Compendium Continuing Education for thePracticing Veterinarian 1987; 9: 42435.

32. Papp, L., Tuboly, S., Vetesi, F. Autoimmune dermatitisin dogs Case report and compilatory account. MayarAllatorvosok Lapja 1994; 49: 71018.

33. Scott, D.W., Wolfe, M.J., Smith, C.A. et al. The com-parative pathology of non-viral bullous skin diseases indomestic animals. Veterinary Pathology 1980; 17: 25781.

34. Rosenkrantz, W.S. Discoid lupus erythematosus. In:Griffin, C.E., Kwochka, K.W., MacDonald, J.M., eds.Current Veterinary Dermatology: The Science and Art ofTherapy. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1993: 15464.

35. Tan, E.M., Cohen, A.S., Fries, J.F. et al. The 1982 revisedcriteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythema-tosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism 1982; 25: 12717.

36. Mason, K.V. Fixed drug eruption in two dogs caused bydiethylcarbamazine. Journal of the American AnimalHospital Association 1988; 24: 3013.

37. Rosenkrantz, W.S. Cutaneous drug reactions. In: Griffin,C.E., Kwochka, K.W., MacDonald, J.M., eds. CurrentVeterinary Dermatology: The Science and Art of Therapy.St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1993: 15464.

38. Malik, R., Medeiros, C., Wigney, D.I. et al. Suspecteddrug eruption in seven dogs during administration offlucytosine. Australian Veterinary Journal 1996; 74: 2858.

39. van Hees, J., Mason, K.V., Gross, T.L. et al. Levamisole-induced drug eruption in the dog. Journal of the AmericanAnimal Hospital Association 1985; 21: 25560.

40. Vitale, C.B., Gross, T.L., Magro, C.M. Vaccine inducedischemic dermatopathy in the dog. Veterinary Dermatology1999; 10: 13142.

41. Walder, E.J., Conroy, J.D. Contact dermatitis in dogsand cats: pathogenesis, histopathology, experimentalinduction and case reports. Veterinary Dermatology1994; 4: 14962.

42. Willemse, T. Clinical Dermatology of Dogs and Cats. AGuide to Diagnosis and Therapy. Philadelphia: Lea &Febiger, 1991: 545.

43. Baker, E. Contact allergy. In: Small Animal Allergy. APractical Guide. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1990:11318.

44. Carlotti, D.N., Pin, D., Bensignor, E. Scrotal contactdermatitis in the dog: 6 cases. Proceedings of the 16thAnnual Congress of the ESVD-ECVD Helsinki (Finland).Ooshra Nylands Tryckei Ab, Finland. 1999: 136.

45. Scott, D.W., Reimers, T.J. Tail gland and perianal glandhyperplasia associated with testicular neoplasia andhypertestosteronemia in a dog. Canine Practice 1986; 13:1517.

46. Gross, T.L., OBrien, T.D., Davies, A.P. et al. Glucagon-producing pancreatic endocrine tumors in two dogs withsuperficial necrolytic dermatitis. Journal of the AmericanVeterinary Medical Association 1990; 197: 161922.

47. Torres, S.M.F., Caywood, D.D., OBrien, T.D. et al.Resolution of superficial necrolytic dermatitis followingexcision of a glucagon-secreting pancreatic neoplasm ina dog. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association1997; 33: 31319.

48. Walton, D.K., Center, S.A., Scott, D.W. et al. Ulcerativedermatosis associated with diabetes mellitus in the dog.A report of four cases. Journal of the American AnimalHospital Association 1986; 22: 7988.

49. Little, C.J.L., McNeil, P.E., Robb, J. Hepatopathy anddermatitis in a dog associated with the ingestion of myco-toxins. Journal of Small Animal Practice 1991; 32: 236.

50. Miller, W.H., Scott, D.W., Buerger, R.G. et al. Necrolyticmigratory erythema in dogs: a hepatocutaneous syndrome.Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association1990; 26: 5738.

51. Smiths, B., Croft, D.L., Abrams-Ogg, A.C.G. Lethalacrodermatitis in Bull Terriers. A problem of defectivezinc metabolism. Veterinary Dermatology 1991; 2: 916.

VDE263.fm Page 74 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd, Veterinary Dermatology, 13, 6376

Canine scrotal lesions 75

52. White, S.D., Gross, T.L. Hereditary lupoid dermatosisof the German shorthaired pointer. In: Bonagura, J.D.,ed. Current Veterinary Therapy XII. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders, 1995: 6056.

53. Vroom, M.W., Theaker, M.J., Rest, J.R. et al. Lupoiddermatosis in five German short-haired pointers. Veterin-ary Dermatology 1995; 2: 938.

54. Dunstan, R.W., Hargis, A.M. The diagnosis of sebaceousadenitis in Standard Poodle dogs. In: Bonagura, J.D.,ed. Current Veterinary Therapy XII. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders, 1995: 61922.

55. Allen, W.E., Noakes, D.E., Renton, J.P. The genitalsystem. In: Chandler, E.A., Thomson, D.J., Sutton, J.B.et al., eds. Canine Medicine and Therapeutics, 3th edn.Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1991: 6597.

56. Fadok, V.A. Necrotizing skin diseases. In: Kirk, R.W.,ed. Current Veterinary Therapy VIII. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders, 1983: 47380.

57. Zook, B.C., Gilmore, C.E. Thallium poisoning in dogs.Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association1967; 152: 20617.

58. Larson, C.P., Keller, W.N., Manges, J.D. Accidentalcanine thallotoxicosis and dangers of thallium used as arodenticidal agent. Journal of the American VeterinaryMedical Association 1939; 95: 4869.

59. Kunkle, G.A. Zinc responsive dermatoses in dogs. In:Kirk, R.W. ed. Current Veterinary Therapy VII. Philadel-phia: W.B. Saunders, 1980: 4726.

60. Kern, T.J., Walton, D.K., Riis, R.C. et al. Uveitis associatedwith poliosis and vitiligo in six dogs. Journal of the AmericanVeterinary Medical Association 1985; 187: 40814.

61. Vercelli, A., Taraglio, S. Canine Vogt-Koyanagi-harada-likesyndrome in two Siberian husky dogs. Veterinary Derma-tology 1990; 1: 1518.

62. Mahafey, M.B., Yarbrough, K.M., Munnel, J.F. Focal lossof pigment in the Belgian Tervuren dog. Journal of theAmerican Veterinary Medical Association 1978; 173: 3906.

63. Panic, R., Scott, D.W., Miller, W.H. Canine cutaneoussterile pyogranuloma/granuloma syndrome: a retrospectiveanalysis of 29 cases 19761988. Journal of the AmericanAnimal Hospital Association 1991; 27: 51928.

64. Barron, C.N. Scrotal neoplasms a report of two cases indog. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association1949; 115: 1314.

65. Brodey, R.S. Multiple genital neoplasia (mast cell sarcoma,seminoma, and sertoli cell tumor) in a dog. Journal of the

American Veterinary Medical Association 1956; 128:4502.

66. Bastianello, S.S. A survey on neoplasia in domesticspecies over a 40-year period from 1935 to 1974 in theRepublic of South Africa. VI. Tumours occurring indogs. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 1983;50: 199220.

67. Milks, H.J. Some diseases of the genitourinary system.Cornell Veterinarian 1939; 29: 10514.

68. Baker, K.P., Thomsett, L.R. Neoplasia and cysts. In:Canine and Feline Dermatology. Oxford: BlackwellScientific, 1990: 172203.

69. Pulley, L.T., Stannard, A.A. Tumors of the skin andsoft tissues. In: Moulton, J.E., ed. Tumors in DomesticAnimals, 3rd edn. Berkeley: University of CaliforniaPress, 1990: 2387.

70. Goldschmidt, M.H., Shofer, F.S. Skin Tumors of the Dogand Cat. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1992: 37291.

71. McEntee, K. Scrotum, spermatic cord, and testis: prolif-erative lesions. In: Reproductive Pathology of DomesticMammals. San Diego: Academic Press, 1990: 279306.

72. Culberston, M.R. Hemangiosarcoma of the canine skinand tongue. Veterinary Pathology 1982; 19: 5568.

73. Weipers, W.L., Jarret, W.F.H. Haemangioma of thescrotum of dogs. Veterinary Record 1954; 66: 1068.

74. Rakich, P.M., Latimer, K.S., Weiss, R. et al. Mucocutaneousplasmacytomas in dogs: 75 cases (19801987). Journal ofthe American Veterinary Medical Association 1989; 194:80310.

75. Taylor, D.O.N., Dorn, C.R., Os, L. Morphologic andbiologic characteristics of canine cutaneous histiocytoma.Cancer Research 1969; 29: 8392.

76. Moore, P.F. Systemic histiocytosis of Bernese Mountaindogs. Veterinary Pathology 1984; 21: 55463.

77. Bloom, F. Spontaneous solitary and multiple mast celltumour (mastocytoma) in dog. Archives Pathology 1942;33: 66175.

78. Nielsen, S.W., Cole, C.R. Canine mastocytoma. A reportof one hundred cases. American Journal of VeterinaryResearch 1958; 19: 41732.

79. Dass, L.L., Sahay, P.N., Khan, A.A. et al. Malignant trans-missible venereal tumour. Canine Practice 1986; 13: 1518.

80. Jackson, C. The contagious (transmissible venereal)neoplasm of the dog and the heart base tumours of thedog. The Onderstepoort Journal Veterinary Science andAnimal Industry 1936; XI: 387413.

Rsum Les lsions scrotales sont peu frquentes et reprsentent souvent un dfi diagnostique. Dans la littraturevtrinaire, aucun texte nest dvolu ce sujet. Cet article rapporte et illustre les lsions cutanes scrotales chezle chien, en suivant lorigine tiologique des lsions afin de faciliter lidentification clinique et le diagnostic. Lesmaladies infectieuses, dorigine immunologique, endocriniennes et noplasiques sont les causes les plus frquentesde lesions du scrotum chez le chien. Elles peuvent atteindre seulement le scotum ou tre galement localises dautres zones cutanes. La presentation clinique des lsions, la prsence de lsions primaries ou de lsionssecondaires, et la prsence de symptmes en relation avec une maladie systmique peuvent aider au diagnostic.Dans certains cas, des examens complmentaires sont indiqus pour obtenir le diagnostic dfinitif. Lexamenhistopathologique est une aide prcieuse pour comprendre les ractions pathologiques de la peau du scrotum,mais malheureusement cet examen est rarement realise et peu darticles dans la littrature font tat danalyseshistopathologiques. La liste des maladies rapporte dans cet article nest pas exhaustive et dautres maladies, plusrares, peuvent galement tre rencontres dans cette localisation.

Resumen Las lesiones escrotales son infrecuentes y presentan a menudo un desafo diagnstico. En la bibliografaveterinaria no existen textos dedicados a este tema. Este estudio revisa e ilustra las lesiones escrotales caninassiguiendo una relacin etiolgica con el objetivo de facilitar la identificacin clnica y el diagnstico. Las causasms frecuentes de lesiones escrotales caninas son de carcter infeccioso, inmunomediado, endocrinolgico y

VDE263.fm Page 75 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM

-

76 R. Cerundolo and P. Maiolino

2002 Blackwell Science Ltd, Veterinary Dermatology, 13, 6376

neoplsico. Pueden afectar slo el escroto o tambin otras reas corporales. La presentacin clnica de las lesiones,la presencia de lesiones primarias o secundarias y la presencia de sntomas clnicos de enfermedad sistmicapueden ayudar en el diagnstico. En algunos casos, son necesarias otras pruebas diagnsticas para conseguir undiagnstico definitivo. La histopatologa ayuda a comprender las reacciones patolgicas de la piel escrotal perodesafortunadamente no se realiza normalmente y pocos estudios incluyen histopatologa. La lista de las afeccionesde esta revisin no es exhaustiva y es posible la presentacin de otras enfermedades menos frecuentes.

Zusammenfassung Skrotale Lsionen sind nicht hufig und oft eine diagnostische Herausforderung. In derveterinrmedizinischen Literatur sind diesem Thema keine Verffentlichungen gewidmet. Diese Studie gibt nacheiner tiologischen bersicht eine Zusammenfassung und Illustration skrotaler Lsionen beim Hund mit demZiel, die klinische Erkennung und Diagnose zu erleichtern. Infektise, immun-bedingte, hormonelle undneoplastische Erkrankungen sind die hufigsten verffentlichten Ursachen von skrotalen Lsionen beim Hund.Sie knnen ausschliesslich den Hodensack oder auch andere Teile des Krpers betreffen. Die klinische Prsentationder Lsionen, das Vorhandensein von primren oder sekundren Lsionen und klinische Zeichen systemischerErkrankungen knnen in der Diagnosefindung behilflich sein. In einigen Fllen sind weiterfhrende Untersuc-hungen ntig, um zu einer definitven Diagnose zu gelangen. Histopathologie zielt darauf ab, pathologischeReaktionen der skrotalen Haut zu verstehen, wird aber unglcklicherweise nicht hufig duchgefhrt und wenigBerichte in der Literatur schliessen Histopathologie ein. Die Liste der hier aufgefhrten Erkrankungen ist nichtvollstndig und andere seltenere Erkrankungen knnen angetroffen werden.

VDE263.fm Page 76 Wednesday, March 20, 2002 1:26 PM