Cultivating Systemic Capacity: The Rhode Island Tobacco Control Enhancement Project

-

Upload

paul-florin -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

1

Transcript of Cultivating Systemic Capacity: The Rhode Island Tobacco Control Enhancement Project

Am J Community Psychol (2006) 38:213–220DOI 10.1007/s10464-006-9080-1

ORIGINAL PAPER

Cultivating Systemic Capacity: The Rhode Island TobaccoControl Enhancement ProjectPaul Florin · Carolyn Celebucki · John Stevenson ·Jasmine Mena · Dawn Salago · Andrew White ·Betty Harvey · Marianela Dougal

Published online: 16 September 2006C© Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2006

Abstract This paper describes the Rhode Island TobaccoControl Enhancement Project (TCEP), a state-university-community technical assistance system. TCEP was devel-oped under the auspices of the Rhode Island Departmentof Health’s Tobacco Control program and was designed tobuild capacity among nine community-based organizationsto mount comprehensive tobacco control interventions in fivediverse communities within the state. This paper: (1) pro-vides a description of community mobilization; (2) presentsa logic model for planning and decision making used bystate-university-community partners; (3) describes training,technical assistance services and implementation; and, (4)describes the evaluation and program improvement activi-ties used to support on-going project development.

Introduction

The Rhode Island Tobacco Control Enhancement Project(TCEP) was initiated in February 2001 by the program man-ager of the Tobacco Control Program at the Rhode IslandDepartment of Health. The program manager’s primary ob-jective was to build capacity in community-based organiza-tions (CBOs) and especially to promote “evidence-based”policy interventions for tobacco control. An additional ob-jective was to develop an evaluation to assess the processand outcomes produced by this initiative. TCEP was a state-

P. Florin (�) · C. Celebucki · J. Stevenson · J. Mena · D. Salago ·A. WhiteDepartment of Psychology, University of Rhode Island,Chafee Bldg., Kingston, RI 02881-0808e-mail: [email protected]

B. Harvey · M. DougalRhode Island Department of Health

university-community technical assistance system that pro-vided program support to nine CBOs engaged in community-level interventions for tobacco control in the five most diversemunicipalities in the state.

The TCEP technical assistance system1 provided a broadarray of supportive strategies including: training programs;telephone and on-site consultation; information and referralservices; coalition development; and methods for dissemi-nating products such as publications and public educationmaterials (Chavis, Florin, & Felix, 1992; Florin, Mitchell,& Stevenson, 1993; Mitchell, Florin, & Stevenson, 2002;Neufeld, 1978). A technical assistance system was neededto build professional, organizational, and systemic capac-ity (Crisp, Swerissen, & Duckett, 2000) because interven-tion programs are characteristically difficult to implement(Lipsey & Cordray, 2000), and more so when they involvecomplex challenges in collaboration and coordinating multi-ple programs and policies (e.g., Florin et al., 1993; Wan-dersman, Goodman & Butterfoss, 1997). The latter wasquintessentially the case in this project at the community-level2 where multi-component interventions combined indi-vidual and environmental change strategies across multiplesettings.

For example, comprehensive tobacco control (thecommunity-level intervention of interest in this article) mightrequire combining a school curriculum for youth to preventinitiation of smoking and a media campaign aimed at reduc-ing parental smoking in the presence of youth (individualchange strategies) with policy change efforts advocating a

1 Also known under rubrics such as “prevention support system” (Wan-dersman & Florin, 2003) or “enabling system” (Chavis et al., 1992).2 Terms such as “community-based,” “comprehensive community,”“Community coalition,” and “collaborative partnerships” have alsobeen used to refer to interventions with similar characteristics.

Springer

214 Am J Community Psychol (2006) 38:213–220

municipal smoking ban for restaurants and increased en-forcement of ordinances prohibiting youth access to tobacco(Warner, 2000). Such complex interventions have, under thebest of circumstances, produced results only about 30% ofthe time (Wandersman & Florin, 2003). Little wonder (asin this case) that capacity building has been advocated formany types of community-level interventions from grass-roots community coalitions to replications of communitytrials (Pentz, 2000; Roussos & Fawcett, 2000; Wolff, 2001).The following paragraphs provide information about aspectsof the TCEP as it was implemented in Rhode Island.

Community mobilization

In Rhode Island, community mobilization was initiated by aRequest for Proposals (RFP) developed jointly by the pro-gram manager of the Rhode Island Tobacco Control Programand the Community Research and Services Team (CRST)in the Psychology Department at the University of RhodeIsland. The RFP was issued to community-based organi-zations willing to conduct comprehensive tobacco control(CTC) in their communities. Five awardees from this RFPwere combined with four minority organization awardeespreviously funded to implement comprehensive tobacco con-trol for their respective communities.3 Thus nine communityorganizations representing a diversity of sizes, organizationaltype, and experiences joined this initiative as communitypartners.

All organizations received funding for a full time tobaccocontrol coordinator, developed a structure (e.g., task force,coalition, advisory group) to engage in community-level en-vironmental change, and worked collaboratively with theDepartment of Health’s Tobacco Control Program and theCRST to build the Tobacco Control Enhancement Project.These nine organizations focused their efforts on five des-ignated geographic communities: four urban, lower incomemunicipalities, (Central Falls, East Providence, Pawtucket,Woonsocket) and a section of Providence know as “TheSouthside” (composed of the four lowest income neighbor-hoods in Providence). Nearly 80% of the minority popula-tions in the state lived in these five communities. In the fiveintervention communities, 69% of the students were eligiblefor subsidized lunch versus 17.5% in the rest of the state.

Planning and decision-making

The next steps were to assess capacity for comprehensive to-bacco control in each of the community-based organizations

3 Local community is often geographically defined (e.g. neighborhoodor municipality) but may be a community of presumed common interest(e.g. Latino community).

and to prepare a core conceptual framework to guide part-ners’ work. TCEP developed both a survey and interviewprotocol for capacity assessment in the nine community-based organizations. A decision was made to develop a briefquantitative survey which would then be followed up by amore in-depth qualitative interview. The survey and inter-view assessed agency capacity in five areas (infrastructure,outreach, planning, program delivery, and evaluation).

Each area contained five or six items taping specific capac-ities. For example, under the planning area, the respondentwas asked, “How able is your agency to. . .” (a) conduct aneeds and resource assessment? (b) map your communityfor tobacco control? (c) form tobacco control goals and ob-jectives? (d) develop a program logic model? (e) identifypromising programs and policies using research evidence?and (f) plan for implementing activities (specifying time-lines, milestones, staffing needs)? The coordinator describedeach capacity as “superior,” “OK,” “needs some work,” or“needs a lot of work.” An initial orientation meeting washeld between the executive director of the organization, thetobacco control coordinator, the TCEP Principle Investiga-tor, and a graduate assistant from TCEP.

This session oriented agency personnel to the purpose andscope of the TCEP project, acquainted the agency staff withTCEP project personnel, and introduced the capacity surveyinformation that served as the basis for the follow-up inter-view. Follow-up interviews (usually scheduled 1–2 weeksafter the orientation session) were conducted by two TCEPgraduate students and focused on developing a more quali-tative, in-depth understanding of agency needs and strengthsusing responses to the quantitative survey as a starting point.Across all organizations, generic strengths were identifiedin infrastructure (including commitment from leadership),outreach (especially with grassroots groups, other agencies,and key community leaders), and planning (especially con-ducting needs assessments and developing objectives).

Capacities more likely to be rated “in need of some work”were those specific to tobacco control, such as “buildinga strong tobacco control coalition” (under the outreach ca-pacity area), “mapping the community for tobacco control”and “developing a logic model” (under planning), or “skillsfor cessation” and “media use for tobacco control” (underprogram delivery). Information from the capacity assess-ment was used to tailor the development of an initial, four-day TCEP training, to plan individualized technical assis-tance for each agency and to reassess capacity as part of theevaluation of the TCEP intervention (see evaluation sectionbelow).

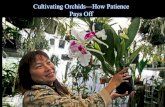

A comprehensive tobacco control logic model (see Fig. 1)was developed as a touchstone that visually communicatedto all partners basic elements of the project. The logic modelwas a constant throughout the project. It was used to de-sign initial and monthly trainings, to sequence and organize

Springer

Am J Community Psychol (2006) 38:213–220 215

Fig. 1 Comprehensive tobacco control logic model

interventions, as a monitoring tool for technical assistance,and as the evaluation framework for the project. Indeed, allpartners have coffee mugs with the phrase “It’s logical tocontrol tobacco” on one side and the TCEP logic model (insmall type) imprinted on the other side.

The TCEP logic model was developed by starting withthree outcome objectives for tobacco control as specified bythe Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): (1)Reduced environmental tobacco smoke; (2) Decreased youthinitiation; and (3) Increased smoking cessation. (A fourthCDC specified outcome, Reduced tobacco related health dis-parities, was infused in the logic model, rather than treatedas a separate objective). The logic model also illustrated howoutcome objectives influenced each other. For example, re-duced environmental tobacco smoke might prompt increasedcessation and both of these outcomes might lead to lessexposure for youth and decreased youth uptake. The logicmodel also specified intermediate objectives (e.g., changesin risk and protective factors) that linked to the outcomeobjectives.

Importantly, the logic model was designed to clearly il-lustrate the fact that risk and protective factors were evi-dent both in the community environment (e.g., communitynorms, formal and informal tobacco control policies) as well

as in the attitudes and behaviors of the community population(e.g., attitudes towards smoking, resistance skills, attempts atquitting or reduced consumption). Furthermore, arrows weredrawn to indicate that changes in environment and popula-tion outcomes would interact and potentially reinforce andamplify each other. For example, changes in policies such assmoking restrictions were linked to increased cessation at-tempts and more negative attitudes towards smoking amongthe population.

Finally, the logic model illustrated how six different cate-gories of interventions might lead to changes in intermediateobjectives. Again, these were divided into those that targetedchanges in the community environment (the top three inter-vention boxes in Fig. 1) and those that were directly aimedat creating changes in individual attitudes, skills, and be-haviors among the community population (the bottom threeintervention boxes in Fig. 1). The assumed logical connec-tions (e.g., arrows) between interventions and intermediateobjectives were diagramed according to empirical evidencewherever possible and dialogue among Tobacco Control staffand CRST team members where empirical evidence wasless complete. The final logic model thus diagramed sixdifferent categories of interventions (with diversity issuesinfused), leading to changes in four interacting categories of

Springer

216 Am J Community Psychol (2006) 38:213–220

intermediate objectives which lead ultimately to changes inthe three CDC specified outcome objectives.

Implementing and sustaining interventions

The TCEP “kicked-off” with a four-day (28 h) training pro-vided by the CRST and Tobacco Control staff to the ninetobacco control coordinators. The training was entitled Cre-ating Comprehensive Tobacco Control4 and participants lit-erally built the logic model presented in Fig. 1 over foursuccessive days. The training emphasized topics identifiedas “needing some work” in the capacity assessment and manyof the experiential exercises were designed to stimulate team-work and produce a sense of community among coordinators.

Copies of the four-day training and curriculum developedas a follow-up (see below) are available from the first au-thor. The training introduced participants to logic modelsand took participants through a running simulation of a five-step process (assessing needs and assets, building capacities,selecting strategies, implementing strategies, and evaluation)covered by many intervention training models.5 The trainingoriented participants to the project logic model and its usein planning, implementing, and evaluating tobacco controlinterventions.

The tobacco control coordinators overall impression ofthe training was positive (e.g., materials were relevant tothe need, learning strategies were engaging, pace was aboutright). Coordinators also believed it was “very likely” theywould take action based on the training (e.g., change howthey worked, use community data to formulate goals). Mostimportantly, as displayed in Table 1, tobacco control coordi-nators reported a significant increase in confidence in theirability to conduct eight different activities related to com-prehensive tobacco control.

The initial four-day training was presented as an overviewof the entire project with subsequent topics to be addressedin detail as the project progressed. That is, it was not ex-

4 Creating Comprehensive Tobacco Control, commissioned by theRhode Island Department of Health Tobacco Control Program, wasan adaptation of Getting Prevention Results: A Five Step Training Pro-cess. Getting Prevention Results was itself an adaptation of Getting toOutcomes, a product originally developed by the Center for SubstanceAbuse Prevention’s National Center for the Advancement of Preven-tion. Rhode Island with the approval of its developers, adapted Gettingto Outcomes to provide an increased number of interactive exercisesfor participants. IN addition, funds to support refinement of the GettingPrevention Results: A Five Step Process for the New England School ofPrevention Studies were provided by CSAP’s Northeast CAPT, fundedby the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse andMental Health Services Administration Grant #UD1SPO8999-01.5 For example, the Federal Center for Substance Abuse Prevention(CSAP) is promoting the five steps referred to in this article as a Strate-gic Prevention Framework for state and community level substanceabuse prevention planning.

pected that training alone would suffice to build capacity forcomprehensive tobacco control. Rather, TCEP services andproducts were designed to work systematically (e.g. buildupon each other) and synergistically (e.g., support and am-plify each other). One example of TCEP services was amonthly three-hour meeting. This monthly meeting allowedboth an in-depth examination of each of the intervention cate-gories sequenced within coalition development tasks (Florin,Mitchell, & Stevenson, 1992) as well as a resource exchangeamong the tobacco control coordinators.

Several intervention techniques were addressed in theTCEP project. Each intervention category was covered forabout a quarter of a year (three or four months). For example,social marketing and media advocacy was covered before(and set the stage for) community events were launched andadvocacy for policy change occurred. During each quarter,monthly meetings and some of the follow-up technical assis-tance (see below) concentrated on the knowledge and skillset associated with a particular topic and on the coordina-tor and coalition taking necessary actions to implement thatparticular intervention technique.

In addition, tobacco control coordinators often sharedknowledge and information that they personally possessedwith the group in a resource exchange format. For exam-ple, one tobacco control coordinator who was a member ofa town council, provided an orientation for others on howlocal ordinances were introduced and passed. Thus monthlymeetings provided the opportunity to expand on particularthemes, exchange resources and information, and offered aspace for partners to be reflective-practitioners.

TCEP staff also provided technical assistance to the ninetobacco control coordinators. Technical assistance transfersknowledge and/or practice skills to clients that helps themto develop or improve programs, products, services, deliverysystems, or internal operations. Technical assistance in TCEPwas delivered by two graduate research assistants, each as-signed to particular tobacco control coordinators. Technicalassistance was delivered on-site, by phone, and/or via e-mail.Technical assistance content was determined in two differentways.

First, technical assistance content was follow-on to thecommon theme addressed during a particular monthly meet-ing. For example, coordinators received assistance in prepar-ing a social marketing plan or with gathering informationabout those likely to support or oppose a policy change withinan organization or municipality (e.g., political mapping).Second, technical assistance content was driven by specificrequests from the tobacco control coordinators. Examples ofsuch requests were locating a survey for restaurants concern-ing attitudes toward smoke-free policies, helping prepare abriefing for a local advisory council, and identifying pro-grams specific to Native American communities.

Springer

Am J Community Psychol (2006) 38:213–220 217

Table 1 Tobacco control coordinatiors pre-post level of confidence

Levels of Confidence

4.72

4.72

4.56

4.61

4.67

4.72

4.67

4.39

4.63

3.72

3.17

3.44

3.00

3.50

3.61

4.11

3.50

3.50

1.00 2.00 3.00 4.00 5.00

Gather data to identify needs and resources fortobacco control

Specify measurable outcome objective for tobaccocontrol

Assess agency and community capacity fortobacco control

Locate science-based interventions for tobaccocontrol

Implement science-based program for tobaccocontrol

Develop an action plan for a policy campaign fortobacco control

Use of variety of media strategies to influencepolicy develop

Monitor the process of policy implementation

Overall confidence

Are

as

Pre-trainingPost-training Not at all

confidentModeratelyconfident

Veryconfident

The TCEP also developed products designed to be usefulto tobacco control coordinators. One product was a series ofbriefing papers that addressed the CDC’s main target areas.Each briefing paper gathered and synthesized informationfrom hundreds of academic articles on evidence-based to-bacco control programs and strategies and put the findingsinto a “user friendly” language and format. The briefing pa-pers have allowed the coordinators and members of theircoalitions to access up-to-date evidence-based informationwithout dealing with multiple and often dense academic ar-ticles.

Another product was a website for the distribution ofTCEP produced information in electronic form and withlinks to other relevant tobacco control sites. The websitealso contained a “click-on” map of Rhode Island communi-ties which allowed the user to access relevant tobacco controldata gathered from a variety of sources for each community.A list-serve, although a simple product, has allowed for in-formation retrieval (i.e., specific requests) among tobaccocontrol coordinators and timely transmittal of “calls to ac-tion” when necessary.

Finally, TCEP staff produced a small wallet-size fold-upcard that described 14 facts about tobacco. This card al-lowed the tobacco control coordinators (and many otherswho have requested these cards) to have, at their fingertips,compelling facts and figures to make their case for tobaccocontrol. The popularity of this card led to the development

of a second card with data from the TCEP adult householdsurvey being used for overall project evaluation. This card,Rhode Island Tobacco Control Facts, displayed data specif-ically from Rhode Island and also contained informationrelevant to policy advocacy (e.g., 79% of Rhode Islandersbelieve there should be. . . .). In both cases, these productswere created in a participatory manner with tobacco controlcoordinators reviewing a wide variety of data and choosingthe facts and figures they thought would be most useful intheir work.

Evaluation and program improvement activities

Monitoring technical assistance services

Monitoring and evaluation was integrated into TCEP ser-vices to promote continuous refinement and to measureimpacts on capacity for conducting tobacco control activ-ities. First, a database was created using Microsoft “Ac-cess” and Microsoft “Visual Basic” to track technical as-sistance delivered to agencies. The database allowed forgraduate assistants to enter the kind and amount of tech-nical assistance delivered, as well as, the intervention cat-egory and intermediate and outcome objectives (from thelogic model) that the technical assistance was designed toenhance. The use of the database became routine and al-lowed for the elimination of paper logs. This provided the

Springer

218 Am J Community Psychol (2006) 38:213–220

advantage of centralized data storage and could produce au-tomatic reports profiling technical assistance use by agencyor reporting period. About 300 different technical assis-tance requests were filled each year and each request tookan average of approximately 1.8 h (inclusive of preparationtime).

Evaluating technical assistance services

Tobacco control coordinators were surveyed each year todetermine the strengths and the weaknesses of activities pro-vided through TCEP monthly meetings and technical as-sistance. In July 2004, technical assistance was viewed asresponsive, easy to access, prompt, respectful of existingskills, and helpful to develop new knowledge and skills (allaveraged above 4 on a 5-point Likert scale where “stronglydisagree” = 1 and “strongly agree” = 5). The perception thatstaff “showed sensitivity to what makes my project unique(e.g., organizational setting, population served)” was espe-cially important to TCEP personnel.

TCEP staff recognized that even free “assistance” cameat a (opportunity) cost. Therefore, we made the followingstatement in our yearly evaluation: “TCEP technical assis-tance may have provided you and your project with benefits.But receiving technical assistance can also have associatedcosts (e.g., takes time and energy, diverts attention from othertasks, and so on). How have the benefits of receiving tech-nical assistance. . .compared with the costs?” In July 2004,three coordinators felt that “benefits equaled costs,” fourthat “benefits exceeded costs,” and two that “benefits greatlyexceeded costs.”

Monthly meetings were perceived by coordinators as wellorganized, creating a feeling of “team spirit” and promotingnew knowledge and skills. Areas identified as needing im-provement included increasing the amount of time for net-working among coordinators and attending to the resourceexchange potential in meetings. Finally, the second adminis-tration of the capacity assessment indicated that the tobaccocontrol coordinators perceived increased capacity in some ofthe areas they identified “as needing work” in the initial ca-pacity assessment. To validate the perceptions of the tobaccocontrol coordinators, we asked the state level program co-ordinator to independently rate capacity and we found theseratings to be comparable with the coordinators’ own ratings.

The quality of CTC data on capacity were hard to judgewithout an objective test. One naturally occurring test of ca-pacity for tobacco control in Rhode Island has been a yearlyattempt to pass a statewide smoking ban. After six years oftrying, in 2005, the “Workplace Safety Act” made RhodeIsland the seventh state in the nation with a statewide smok-ing ban. The CTC tobacco control coordinators carefullyadvocated at both municipal and statewide levels, creating apowerful synergy and their leadership has been recognized

by the broad based Coalition for a Healthy Rhode Island thatcoordinated the campaign.

Monitoring CTC intervention activities

A monthly reporting form was designed to act as both adescriptive measure of tobacco control coordinators’ experi-ences in attempting to implement tobacco control initiativesand an evaluative tool. From an evaluation standpoint, themonthly reporting form allowed coordinators to documenttheir major activities and accomplishments. With this de-scriptive tool, coordinators were able to document specificbarriers (e.g., within their agency, community, and state)that inhibited them from implementing tobacco control ini-tiatives, the extent and quality of the training and technicalservices they received during the reporting period, and theirlevel of involvement with other organizations.

The reporting form also acted as a complementary toolto the logic model. Specific activities and linkages to out-come objectives could be considered in the context of thelogic model. In addition, each of the key constructs (asshown in the logic model) represented a specific categoryof interventions. Each category was then segregated into amore exhaustive list of activities. For example, the category“Media Advocacy and Social Marketing Interventions” wasbroken down into such activities as conducting televisioninterviews, writing editorials at the state- or local-level, andpaying for additional public service announcements, whileCommunity Mobilization included activities such as assist-ing with policing programs, contacting government officialsand key decision-makers about tobacco control policies, andconducting compliance checks for local businesses.

For each activity in which they engaged, tobacco con-trol coordinators were asked to supply specific informa-tion, including the status of the activity (e.g., in planning,in progress, completed), the types of materials that weredistributed (e.g., surveys, reports, informational pamphlets),language used in the materials, as well as the specific au-dience the activity targeted (e.g., cultural group, coalitionmembers, restaurant/bar owners). In addition, tobacco con-trol coordinators were asked to specify where that particularintervention activity was expected to most impact intermedi-ate and outcome objectives. Overall, the monthly reportingform offered a way in which tobacco control coordinatorscould document their progress over the entire project period.

Evaluating the entire CTC initiative

There were two major questions to be answered by the out-come evaluation of this project. The first question concernedwhether the CTC communities as compared with the restof the state of Rhode Island demonstrated increases frombaseline to the end of the funding cycle (4 years) in the

Springer

Am J Community Psychol (2006) 38:213–220 219

intermediate outcomes, (i.e., favorable community norms forpolicy initiatives, formal and informal tobacco control poli-cies, negative attitudes towards tobacco use and industry, andattempts to quit and decreases in per capita consumption).The second question focused on whether CTC communitieswould show decreases in the long-term outcomes of expo-sure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), youth initiationof tobacco products, and increases in smoking cessation. Athird question concerned assessing differences (where pos-sible) within the geographic communities or within certaindemographic subgroups (i.e., SES, gender, race/ethnicity) inoutcome achievement.

The specific steps that TCEP undertook in planning theoutcome evaluation involved examining, enhancing, coordi-nating, and developing instrumentation for long-term, short-term, and process evaluation. First, we examined all repre-sentative data collection efforts within the Rhode Island De-partment of Health and Education that could inform the CTCevaluation design, including but not limited to the BehavioralRisk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), Household Inter-view Survey (HIS), Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS),Youth Tobacco Survey (YTS), and the School Accountabil-ity for Learning and Teaching Survey (SALT). With thedearth of short-term and intermediate tobacco related mea-sures available for sub-state estimates, TCEP undertook theadministration of a cross-sectional, adult telephone survey(using a random digit dialing procedure). This survey wasreferred to as the Rhode Island Adult Tobacco Survey (RI-ATS). Base-line data were collected from January throughJune of 2002 with the intention of repeating the survey in2006.

Items in the RIATS were comparable to those found infederal and state tobacco surveys and assessed constructs foreach of the intermediate and outcome objectives. Examplesincluded: smoking status, prevalence, and incidence; quit-ting history; addiction level; quitting aids and use of quittingservices; exposure to media and community events; physi-cian advice; support for tobacco control policies; workplace,home, and car smoking restrictions; and past week ETS ex-posure at home, work, and other places. Demographics in-cluded gender, race/ethnicity, age, income, education, work-ing status, insurance coverage, and household compositiondocumenting the number of smokers and children under 18and 12 years of age in the home.

In-school, youth surveillance in Rhode Island was exten-sive and data were available at sub-state levels. A middle andhigh school surveillance survey, SALT, was commissionedby the Department of Education (RIDE) and was a censusof all public elementary, middle, and high schools. This datapermitted comparison of the CTC intervention communitieswith the remainder of state and the state as a whole. Thissurvey also provided trend data on two long-term indicatorsof interest, prevalence and intensity of cigarette and smoke-

less tobacco use. Finally, this survey provided data relatedto one intermediate indicator (i.e., perceived risk of harm insmoking a pack a day or more) and one process measure (i.e.,exposure to prevention curriculum) as well as demographicdata including age, grade, and race/ethnicity.

Observations regarding the implications of TCEP forcommunity practice

The editors of this special issue asked authors to comment onthe implications for community practice they gleaned fromtheir experience. One thing we’ve learned from the TCEPexperience is to attempt to express things briefly and directly(not always easy for academics). So here are a few wordsabout our lessons learned related to mobilization, planning,implementation, and evaluation:

Mobilizing the community: Partners must have credibilityat the community and state levels

CBOs in the TCEP project had the respect of their localconstituencies (e.g., geographic and/or ethnic communities)because of their grassroots origins, long time service, andthe fact that coordinators worked and lived in the commu-nities they served. In addition, the CBOs had credibilitywith the state because of their willingness to participate ina capacity building enterprise and credibility with the uni-versity team because of respect developed in past projects.It was our belief that a capable CBO without communitycredibility would diffuse resources while establishing credi-bility. On the other hand, a CBO with community credibil-ity but without capacity to deliver programs and productswould squander resources. The Rhode Island Departmentof Health Tobacco Control Program chose to build capacityamong CBOs with credibility in the community and credibil-ity at the state level which permitted the most efficient use ofresources.

Planning & decision making: A shared theory ofchange(logic model) among partners is important

The importance of having a common point of reference forall partners cannot be overstated. The CTC logic model ortheory of change served as a consistent touchstone that pro-vided various advantages. One advantage of working withthe CTC logic model was that it served as a communicationtool for trainings and meetings. A quick reference to a boxin the logic model resulted in a general understanding of thetopic of discussion, thus avoiding redundant explanationsand facilitating the ability of participants to stay on task. Thelogic model was also used to organize monthly reportingforms, track technical assistance, provide evaluation feed-back, and organize presentations at national conferences, all

Springer

220 Am J Community Psychol (2006) 38:213–220

of which reinforced the use of the logic model as a sharedframe of reference.

Implementation: Small groups are a potent force

The nine tobacco control coordinators were a relatively smallgroup, but individually each of them was a leader in tobaccocontrol. Together they were a potent force. Each coordinatorwas a nexus for all the different intervention strategies beingimplemented. Coordinators mounted different interventionsthrough a host of interactions in a variety of settings rangingfrom one-on-ones with editors of local newspapers to mobi-lizing coalition members to advocate for policy changes toorganizing city-wide events for hundreds. To coordinators,it sometimes felt like they were keeping many plates spin-ning in the air. Other times it seemed like a symphony ofpraxis, as the small group of coordinators exchanged ideasabout how to manage the forces they had put in motion. Webelieve a greater number of people in the CTC communitieshave been reached and a greater variety of roles and activi-ties have been carried out as a result of collaboration amonggroup members. We also believe that these successes couldnot have been achieved if coordinators had worked alone.

Evaluation: Moving targets are best seen from multipleperspectives

Research in general and evaluation research in particular of-ten require creativity and flexibility if one is to capture theessence of the issue under study. The CTC project evalua-tion process was particularly dynamic and interactive whichallowed us to respond to the tobacco control coordinators’feedback and improve the usefulness of the TCEP systemand services. Coordinators, state level program managers,and technical assistance providers from the University eachsupplied their unique perspectives about organizational ca-pacities which allowed triangulation while “real time” track-ing of technical assistance has allowed us to create a “dosestrength” view of what was delivered to each CBO. We ea-gerly await the second round of our random telephone surveyto assess which particular attitudes and behaviors might havechanged among the population. And while we wait, we allbreathe a little easier in Rhode Island as a statewide smokingban goes into effect.

Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge the tobacco con-trol coordinators and executive directors of the following community

based organizations for their dedication and commitment to the TobaccoControl Enhancement Project initiative: Channel One Central Falls,East Providence Substance Abuse Prevention Task Force, InternationalInstitute of Rhode Island, Pawtucket Substance Abuse Prevention TaskForce, Progreso Latino, Rhode Island Indian Council, Southeast AsianDevelopment Corporation, Urban League of Rhode Island, WoonsocketTask Force on Substance Abuse.

References

Chavis, D. M., Florin, P., & Felix, M. R. J. (1992). Nurturing grass-roots initiatives for community development: the role of enablingsystems. In T. Mizrahi & J. Morrison (Eds.), Community organi-zation and social administration: advances, trends and emergingprinciples. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press.

Crisp, B. R., Swerissen, H., & Duckett, S. J. (2000). Four approachesto capacity building in health: consequences for measurementand accountability. Health Promotion International, 15(2), 99–107.

Florin, P., Mitchell, R., & Stevenson, J. (1993). Identifying trainingand technical assistance needs in coalitions: a developmental ap-proach. Health Education Research: Theory and Practice, 8, 417–432.

Lipsey, M. W., & Cordray, D. S. (2002). Evaluation methods for socialintervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 345–377.

Mitchell, R., Florin, P., & Stevenson, J. F. (2002). Supportingcommunity-based prevention and health promotion initiatives: de-veloping effective technical assistance systems. Health Educationand Behavior, 29, 620–639.

Neufeld, G. R. (1978). Technical assistance systems in human ser-vices: an overview. In S. Sturgeon MLT, A. Ziegler, R. Neufeld,& R. Wiegerink (Eds.), Technical assistance: facilitating change.Bloomington, IN: Developmental Training Center, Indiana Uni-versity.

Pentz, M. A. (2000). Institutionalizing community-based preventionthrough policy change. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(3),257–270.

Roussos, S. T., & Fawcett, S. B. (2000). A review of collaborativepartnerships as a strategy for improving community health. AnnualReview of Public Health, 21, 369–402.

Wandersman, A., & Florin, P. (2003). Community interventionsand effective prevention. American Psychologist, 58(6–7), 441–448.

Wandersman, A., Goodman, R., & Butterfoss, F. (1997). Understandingcoalitions and how they operate. In M. Minkler (Ed.), Communityorganizing and community building for health. New Brunswick,NJ: Rutgers U. Press.

Warner, K. E. (2000). The need for, and value of, a multi-level ap-proach to disease prevention: the case of tobacco control. In B. D.Smedley & S. L. Syme (Eds.), Promoting health: interventionstrategies from social and behavioral research (pp. 417–449).Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Wolff, T. J. (Ed.). (2001). Special section: contemporary issues se-ries I community coalition building—Contemporary practiceand research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(2).

Springer