COVER: Men of the 1st Battalion, 9th Ma- at Da Nang, during the

Transcript of COVER: Men of the 1st Battalion, 9th Ma- at Da Nang, during the

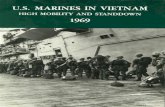

COVER : Men of the 1st Battalion, 9th Ma-rines wait to board the amphibious transportPaul Revere at Da Nang, during the firstphase of the withdrawal of American force sfrom Vietnam .Department of Defense Photo (USMC) A800469

HQMC20 JUN 2002

ERRATUMto

USMC MARINES IN VIETNAM

HIGH MOBILITY AND STANDDOWN 1969 (SFT)

1 . Change the distribution PCN read 19000310300 "vice "19000310200 .

DISTRIBUTION: PCN 19000310380

PCN 19000310380

U.S. MARINES IN VIETNAMHIGH MOBILITY AND STANDDOWN

196 9

by

Charles R. Smith

HISTORY AND MUSEUMS DIVISIO NHEADQUARTERS, U .S. MARINE CORP S

WASHINGTON, D.C .

1988

Volumes in the Marine Corps

Vietnam Series

Operational Histories Series

U.S. Marines in Vietnam, 1954-1964, The Advisory and Comba tAssistance Era, 197 7

US. Marines in Vietnam, 1965, The Landing and the Buildup, 197 8

US. Marines in Vietnam, 1966, An Expanding War, 198 2

US. Marines in Vietnam, 1967, Fighting the North Vietnamese, 198 4

U.S. Marines in Vietnam, 1970-1971, Vietnamization and Redeployment, 198 6

In Preparation

U.S. Marines in Vietnam, 1968

U.S. Marines in Vietnam, 1971-1973

U.S. Marines in Vietnam, 1973-1975

Functional Histories Serie s

Chaplains with Marines in Vietnam, 1962-1971, 198 5

Marines and Military Law in Vietnam: Trial By Fire, in preparatio n

Anthology and Bibliography

The Marines in Vietnam, 1954-1973, An Anthology and Annotated Bibliography ,1974, reprinted 1983 ; revised second edition, 198 5

Library of Congress Card No . 77-604776

PCN 19000310300

Foreword

This is the sixth volume in a planned nine-volume operational and chronological ser-ies covering the Marine Corps ' participation in the Vietnam War . A separate functionalseries will complement the operational histories . This volume details the change in Unit-ed States policy for the Vietnam War. After a thorough review, President Richard M . Nixonadopted a policy of seeking to end United States military involvement in Vietnam eithe rthrough negotiations or, failing that, turning the combat role over to the South Viet-namese . It was this decision that began the Vietnamization of the war in the summe rof 1969 and which would soon greatly reduce and then end the Marine Corps' comba trole in the war.

The Marines of III Marine Amphibious Force continued the full range of military an dpacification activities within I Corps Tactical Zone during this period of transition . Unti lwithdrawn, the 3d Marine Division, employing highly mobile tactics, successfully blunt-ed North Vietnamese Army efforts to reintroduce troops and supplies into Quang Tr iProvince . The 1st Marine Division, concentrated in Quang Nam Province, continued bot hmobile offensive and pacification operations to protect the city of Da Nang and surround-ing population centers . The 1st Marine Aircraft Wing provided air support to both divi-sions, as well as other allied units in I Corps, while Force Logistic Command served al lmajor Marine commands .

Although written from the perspective of III MAF and the Marine ground war in ICorps, an attempt has been made to place the Marine role in relation to the overall Ameri -can effort . The volume also treats the Marine Corps' participation in the advisory effort ,the operations of the Seventh Fleet Special Landing Force, and, to a lesser extent, th eactivities of the 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile), 23d Infantry (Americal) Division ,and 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized) . There are separate chapters on Ma-rine air, artillery, surveillance, and logistics .

The nature of the war facing III MAF during 1969 forced the author to concentrat eon major operations . This focus in no way slights those Marines whose combat servic einvolved innumerable patrols, wearying hours of perimeter defense, and long days o fproviding logistical and administrative support for those in the field . III MAF's combatsuccesses in 1969 came from the combined efforts of all Americans in I Corps .

The author, Charles R . Smith, has been with the History and Museums Division sinc eJuly 1971. He has published several articles on military history, and is the author of Ma-riner in the Revolution: A History of the Continental Marines in the American Revolu-tion, 1775-1783 (Washington : Hist&MusDiv, HQMC, 1975) . He is a graduate of theUniversity of California, Santa Barbara, and received his master 's degree in history fro mSan Diego State University. He served in Vietnam with the 101st Airborne Division (Air -mobile) in 1968 and 1969, first as an artilleryman and then as a historian .

*4Vft!nE. H. SIMMON S

Brigadier General, U.S . Marine Corps (Ret . )Director of Marine Corps History and Museums

iii

Preface

US. Marines in Vietnam : High Mobility and Standdown, 1969, like its predecessors ,is largely based on the holdings of the Marine Corps Historical Center . These holdingsinclude the official unit monthly command chronologies, combat after-action reports ,daily message and journal files, files and studies of HQMC staff agencies and those ofthe Office of the Commandant, and the Oral History, Personal Papers, and Referenc eCollections of the Center.

The author supplemented these above sources with research in the records of the othe rServices and pertinent published primary and secondary sources . Although none of theinformation in this history is classified, some of the documentation on which it is base dstill carries a restricted or classified designation . More than 200 reviewers, most of whomwere participants in the events covered in this volume, read a comment edition of th emanuscript . Their comments, where applicable, have been incorporated into the text .A list of those who made substantial comments is included in the appendices . All ranksused in the body of the text are those held by individuals in 1969 .

Like the previous volumes in the series, the production of this volume has been a cooper -ative effort . Members of the Histories Section, History and Museums Division, past andpresent, have reviewed the draft manuscript . Mrs . Joyce Bonnett, head archivist, and he r

assistants; aided the author's access to the records of the division and Headquarters Ma-rine Corps staff agencies . Miss Evelyn A . Englander, head librarian, and her assistant ,Mrs . Patricia E . Morgan, were very helpful in obtaining needed reference materials, aswere members of the Reference Section, headed by Mr. Danny J . Crawford . Mrs . Regin aStrother, formerly with the Defense Audio Visual Agency and now with the History an dMuseums Division, graciously assisted in the photographic research . Mr. Benis M. Frank ,head of the Oral History Section, was equally helpful in not only making his tapes an dtranscripts available, but also in interviewing a number of key participants and reviewin ga copy of the draft manuscript .

Mr. Robert E . Struder, head of the Publications Production Section, adeptly guidedthe manuscript through the various production phases and assisted the author in partial-ly mastering the intricacies of computer publication . The typesetting of the manuscriptwas done by Corporal James W. Rodriguez II and Lance Corporal Javier Castro . Mrs . Cather -ine A. Kerns contributed significantly to the typesetting effort, developed the charts ac-companying the text, and cheerfully and professionally provided considerable technica lexpertise on typesetting procedures . Mr. William S . Hill, the division 's graphics specialist,expertly produced the maps and completed the design and layout of the volume . Theindex was prepared by the author and Mrs . Meredith P. Hartley with the guidance an dassistance of Mr. Frank .

The author gives special thanks to Brigadier General Edwin H . Simmons, Director o fMarine Corps History and Museums, whose policies guide the Vietnam series ; to Deput yDirectors for History, Colonel Oliver M. Whipple, Jr., Colonel John G . Miller, and thei rsuccessor, Colonel James R . Williams, who provided continuing support and guidance ;to Mr. Henry I . Shaw, Jr., Chief Historian, who aided the author by giving him the benefi tof his considerable experience in writing Marine Corps history, encouragement, advice,

v

vi

prodding when needed, and general editorial direction ; and to Mr. Jack Shulimson, Head ,Histories Section and Senior Vietnam Historian, for providing advice and guidance, an d

for editing the final manuscript .

The author is also indebted to his colleagues in the historical offices of the Army, Navy,Air Force, and Joint Chiefs of Staff, who freely exchanged information and made perti-nent documents available for examination . The author must express his gratitude als oto all those who reviewed the comment edition and provided corrections, personal pho-tographs, and the insights available only to those who took part in the events . To all theseindividuals and all others connected with this project, the author is indebted and trul y

grateful . In the end, however, it is the author alone who is responsible for the conten tof the text, including opinions expressed and any errors in fact .

CHARLES R. SMITH

Table of Contents

Foreword ii i

Preface vTable of Contents vi i

Maps, Charts, and Tables x i

PART I THE CONTINUING WAR 1

Chapter 1 Planning the Campaign 2I Corps Order of Battle 2

Strategy: A Reevaluation of Priorities 8I Corps Planning 1 2

Chapter 2 Mountain Warfare 1 5Northern I Corps 1 5Off Balance 1 6

From the Cua Viet, South 2 4Chapter 3 The Spring Offensive Preempted 2 7

Strike into the Da Krong 2 7A Phased Operation 2 8Phase I 3 1Backyard Cleanup 3 3

Chapter 4 The Raid into Laos 3 8Across the Da Krong 3 8The NVA Retaliates : 3 9Ambush Along 922 3 9Heavy Fighting 4 5Back Into Laos 47Persistent Problems 47Phased Retraction 48Laos : Repercussions 5 1

Chapter 5 The Quang Tri Border Areas 5 2No Change in Tactics 5 2

The DMZ Front 5 2Brigade Mauls 27th 5 8The 9th Battles the 36th 6 1The Vietnam Salient 6 2Apache Snow 6 7Central DMZ Battles : 7 2Eastern Quang Tri and Thua Thien 7 6

PART II SOUTHERN I CORPS BATTLEGROUND 7 9

Chapter 6 Destruction of Base Area 112 8 0Defense of Da Nang 8 0Attack into 112 82

vii

"A Little Urban Renewal" 9 5Americal's TAOI 10 1

Chapter 7 The Battle for Quang Nam Continues 10 3Rockets Equal Operations 10 3Operation Oklahoma Hills 10 35th Marines and the Arizona 11 6Securing the Southern and Northern Approaches 12 1Americal Battleground 12 5

PART III THE THIRD'S FINAL MONTHS 12 7

Chapter 8 Redeployment : The First Phase 12 8Keystone Eagle 12 8"A Turning Point " 13 3

Chapter 9 "A Strange War Indeed" 13 8Company Patrol Operations 13 8Idaho Canyon 13 8"A Significant Step" 14 9Specter of Anarchy 15 4

Chapter 10 "A Difficult Phase " 15 9Maintaining a Protective Barrier 15 9"You Shouldered Us" 16 5The Brigade Takes Over 17 0

PART IV QUANG NAM: THE YEAR'S FINAL BATTLES 17 3

Chapter 11 Go Noi and the Arizona 17 4Vital Area Security 17 4Pipestone Canyon : The Destruction of Go Noi Island 17 41st Marines : Protecting the Southern Flank 18 7The Arizona 19 0

Chapter 12 Da Nang and the Que Son Valley 20 1The 7th Marines 20 126th Marines : Protecting the Northern Flank 21 2Quang Tin and Quang Ngai Battleground 21 5Results 21 6

PART V SUPPORTING THE TROOPS 219

Chapter 13 Marine Air Operations 22 01st MAW Organization and Deployment 22 0Single Management : Relations with the Seventh Air Force 22 3Upgrading of Aviation Assets 22 6I Corps Fixed Wing Support 22 9The Interdiction Campaign 23 1Air Control 234Helicopter Operations 23 6Improving Helicopter Support 23 9Air Defense 24 1Accomplishments and Costs 24 1

Chapter 14 Artillery and Surveillance 243

ix

Artillery Operations 24 3Surveillance and Reconnaissance Activities 25 1

Chapter 15 Supplying III MAF 26 0Force Logistic Command 26 0Naval Support Activity, Da Nang 26 4Engineer Support 26 7Motor Transport 27 0Medical Support 27 2Communications 27 4Logistics of Keystone Eagle and Keystone Cardinal 27 5

PART VI UNIQUE CONTRIBUTIONS 279

Chapter 16 Pacification 280The National Perspective 280

Pacification Planning In I Corps 28 3Line Unit Pacification 28 5Civic Action 28 7

The Grass Roots Campaign 288

Results 294Chapter 17 Special Landing Force Operations 29 7

The Strategic Reserve 29 7Organization and Operations 29 8The Fleet's Contingency Force 310

Chapter 18 The Advisory Effort and Other Activities 31 1

Marine Advisors and the Vietnamese Marine Corps 31 11st Air and Naval Gunfire Liaison Company (ANGLICO) 31 6

U.S . Marines on the MACV Staff 31 7

Embassy Guard Marines 31 8

Chapter 19 1969 : An Overview 31 9

NOTES 32 3

APPENDICESA. Marine Command and Staff List, January-December 1969 336

B. Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations 349

C. Chronology of Significant Events, January-December 1969 354

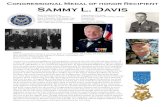

D. Medal of Honor Citations, 1969 358

E. List of Reviewers 374

F. Distribution of Personnel, Fleet Marine Force Pacific (31 January 1969) 376

G. Distribution of Personnel, Fleet Marine Force Pacific (8 December 1969) 38 1

INDEX 386

Maps, Charts, and Table s

Map, Reference Map, I Corps Tactical Zone xi iMap, Allied Commands in I Corps, January 1969 4

Chart, III MAF Command Relationships 6Map, Enemy Order of Battle, Northern ICTZ, January 1969 1 6Map, 3d Marine Division Outposts and Operational Areas, January 1969 2 1

Map, Assault into the Da Krong Valley, 22-25 January 1969 3 2Map, 9th Marines Movement into Base Area 611 40Map, Movements and Objectives of the 3d and 4th Marines, March July 1969 5 8

Map, Operation Maine Crag, 15 March-2 May 1969 6 5Map, Operations of the 9th Marines, May-August 1969 7 3

Map, Enemy Order of Battle, Southern ICTZ, January 1969 8 2Map, Assault on Base Area 112 90Map, Enemy Ground and Rocket Attacks Against Da Nang, February 1969 9 8Map, 7th Marines' Operation Oklahoma Hills, 31 March-29 May 1969 10 9

Table, The MACV List : Composition of Keystone Eagle 13 5

Map, Denial Operations of the 3d Marines, July-August 1969 14 0Map, 3d Marine Division Operations, July-September 1969 14 4

Table, The MACV List : Composition of Keystone Cardinal 16 7

Map, Operation Pipestone Canyon : Attack on Go Noi 18 0

Map, Cordon of Tay Bang An, 15-17 July 1969 184

Map, Scheme of Maneuver, 5th and 7th Marines, July-December 1969 19 2

Map, Hiep Duc Valley Counterattack, 21-26 August 1969 20 8

Map, Hiep Duc Valley Counterattack, 26-29 August 1969 208

Map, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing Locations, 1969 22 2Chart, III MAF Logistic Command Relationships and Facilities, 31 March 1969 26 1

Chart, Special Landing Force Command Relationships 298Chart, Strength, Arms, and Equipment of a Typical Special Landing Force 29 9

Map, Special Landing Force Operations, 1969 304

Chart, Marine Advisory Unit, 1969 312

xi

X11

Reference Ma p

I Corps Tactical Zone

0

2 5kilometers

DaNang

South

China

Sea

Thailand

SouthChinoSea

Quang Tri

Thua Thien

Quang Nam

Quang Tin

Quang Ngai

CHAPTER 1

Planning the CampaignI Corps Order of Battle — Strategy : A Reevaluation of Priorities—I Corps Plannin g

I Corps Order of Battle

Responsibility for the defense of the Republic ofVietnam ' s five northernmost provinces of Quang Tri ,Thua Thien, Quang Nam, Quang Tin, and Quan gNgai in January 1969 rested with III Marine Amphibi-ous Force (III MAF) . Commanded by Lieutenan tGeneral Robert E . Cushman, Jr., III MAF consistedof approximately 81,000 Marines situated at position sthroughout the provinces which constituted I Corp sTactical Zone (ICTZ) . Major General Charles J .Quilter 's 15,500-man 1st Marine Aircraft Wing (1s tMAW) controlled more than 500 fixed-wing and ro-tary aircraft from fields at Chu Lai, Da Nang, Phu Bai ,and Quang Tri . Headquartered on Hill 327 southwes tof Da Nang, Major General Ormond R . Simpson's 1stMarine Division, 24,000 strong, operated throughoutQuang Nam Province . The 21,000-man 3d Marine Di -vision, commanded by Major General Raymond G .Davis and controlled from Dong Ha Combat Base ,was responsible for Quang Tri Province . At Da Nang ,the 9,500 officers and men of Brigadier General Jame sA . Feeley, Jr .'s Force Logistic Command (FLC) provid -ed the wing and two Marine divisions with combatmateriel and maintenance support . Scattered through-out the hundreds of villages and hamlets of the fiv eprovinces were the 1,900 officers and men of the Com -bined Action Program (CAP), under Colonel EdwardF. Danowitz, who continued the Marines' ambitiou sexperiment in local security, still hampered somewha tby the residual effects of the enemy ' s 1968 Te tOffensive .

In addition to Marines, III MAF controlled approx-imately 50,000 United States Army troops . Located i nQuang Tri Province, 5,000 officers and men of the 1s tBrigade, 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized), com-manded by Colonel James M. Gibson, USA, aided i npreventing enemy infiltration of the coastal plains . Tothe south, in Thua Thien Province, the 101st Airborn eDivision (Airmobile), under Major General Melvi nZais, USA, deployed three brigades totalling 20,000men in an arc protecting the ancient imperial capitalof Hue . These two Army units, which had been shift-ed to I Corps in 1968, together with the 3d Marine

Division, constituted XXIV Corps, commanded byArmy Lieutenant General Richard G . Stilwell .* Locatedat Phu Bai, Stilwell's organization was under the oper-ational control of III MAE Based at Chu Lai insouthern I Corps, the 23,800 Army troops of MajorGeneral Charles M . Gettys' 23d Infantry (Americal )Division operated in Quang Tin and Quang Nga iProvinces under the direct control of III MAE Als ounder the direct control of General Cushman, in hiscapacity as Senior U .S . Advisor in I Corps, were the400 officers and men from all services of the Unite dStates Army Advisory Group (USAAG), who provid-ed professional and technical assistance to South Viet-namese military units operating in I Corps Tactica lZone .

As a member of the III MAF staff, Mr. Charles T.Cross, the civilian deputy for Civil Operations andRevolutionary Development Support (CORDS), coor-dinated the pacification effort in I Corps through hi sU .S . civilian and military representatives at theprovince and district level . Directly controlled b yMACV, CORDS was created to integrate and direc tthe country-wide pacification program .

Other U .S . and allied contingents that were neithe rattached to nor controlled by III MAF also operate dwithin the boundaries of I Corps . Assigned to the U.S .Army Support Command, U.S . Naval Support Activi-ty, 3d Naval Construction Brigade, 45th Army En-gineer Group, Task Force Clearwater, and the AirForce' s 366th Tactical Fighter Wing were approximatel y31,000 U.S . Army, Navy, and Air Force personnel .While controlled by their respective services, these sup -port units cooperated closely with III MAE Like th eother five major allied organizations, the 7,800-ma n2d Republic of Korea Marine Brigade, commanded byBrigadier General Dong Ho Lee, which protected a nenclave south of Da Nang centered on Hoi An ,received operational guidance from III MAF, but wa sunder the direct authority of the commanding genera l

*In order to provide operational direction for the expanded Unite dStates military effort in northern I Corps during Tet, MACV For-ward was established at Phu Bai in early February 1968 . On 10 March ,the command unit was redesignated Provisional Corps, Vietnam ,and on 15 August again redesignated as XXIV Corps .

2

PLANNING THE CAMPAIGN

3

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) A19282 8

LtGen Robert E. Cushman, Jr., right, is congratulated by Gen Creighton Abrams, Com-mander, U. S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, after being presented a Gold Sta rin lieu of a second Distinguished Service Medal. As Commanding General, III MarineAmphibious Force since June 1967, Cushman oversaw a doubling of III MAF's strength .

of Korean Forces in Vietnam, whose headquarters wa sin Saigon .

The Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) andits paramilitary forces gradually were assuming a muc hgreater share of the fighting in I Corps by 1969 . Lieu -tenant General Hoang Xuan Lam, commandin gICTZ, controlled a force of 34,000 ARVN regulars .Headquartered at Hue, the 17 battalions of Majo rGeneral Ngo Quang Truong ' s 1st ARVN Infantry Di -vision pursued enemy forces in Quang Tri and ThuaThien Provinces . In southern I Corps the 2d Division's12 infantry battalions, commanded by Brigadier

General Nguyen Van Toan, fought both enemy regu-lars and guerrillas throughout Quang Tin and Quan gNgai Provinces . Between the two ARVN infantry di -visions, the 51st Infantry and Armored Cavalry Regi-ments operated in Quang Nam Province . The 1s tRanger Group, normally stationed at Da Nang, actedas corps reserve, while the Vietnamese Air Force's 41s tTactical Wing, also located at Da Nang, provided over-all air support .

Reinforcing ARVN regulars were 49,800 troops ofthe Regional and Popular Forces (RF and PF), an d8,500 trained members of the part-time People's Self-

4

HIGH MOBILITY AND STANDDOWN

Cam Lo•i,Ctg;

Dong Ha

Quan gT (i SVantlegrIftSharon

Tr i

• Khe'Sanh x

y1 t►~1~ $,Camp Evans'

Allied Command sin I Corps ,

January 196 9

XXIVkilometers

0 25

50

7 5

Da Nang (ARV NX X

SouthChinaSea

I 1{►~~~

1II

ARVN

USMC

Martac. Mountai nAIr ra[IiIty c\

ARVN

X

ROKMC1 ~RGR

Quang Nam G P

An HoaARVN-

~

r-~-1_~ •

Tam

zX

1

Hiep Du c

Quang Tin

USA

Quang Ngai ARV N

Camp Ea gX X

Thua Thie n

Cambodia

PLANNING THE CAMPAIGN

5

Defense Force (PSDF)—a paramilitary organizationrecruited, trained, and stationed in local areas . Amon gother Vietnamese units available to combat smal lgroups of guerrilla infiltrators and root out membersof the local Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI), were th e9,000-man National Police, and the National Polic eField Force with a strength of 2,500 . In addition, therewere 6,200 men of the Civilian Irregular Defens eGroup (CIDG), composed of Montagnard and Nungtribesmen, Cambodians, and Vietnamese, recruite dand trained by the South Vietnamese Special Force sand advised by the U .S . Army's 5th Special Force sGroup (Airborne), which occupied nine mountai ncamps rimming the lowlands . Their task was to col-lect intelligence on enemy activities and attempt t oblock enemy infiltration routes into the heavily popu-lated coastal plains . ,

From a modern complex of air-conditioned build-ings on the banks of the Song Han at Da Nang ,General Cushman coordinated the activities of thi sdiverse group of forces . Like his predecessor, Lieu -tenant General Lewis W . Walt, he functioned withina complex chain of command . III Marine AmphibiousForce was under the operational control of the Com-mander, U .S . Military Assistance Command, Viet-nam, General Creighton W. Abrams ; but with respectto administrative matters affecting his Marines, Gener -al Cushman reported directly to Lieutenant General

Henry W . Buse, Jr ., Commanding General, Fleet Ma-rine Force, Pacific (FMFPac), in Hawaii . As command -ing general of III MAF, General Cushman not onlydirected the operations of all United States combatunits in I Corps, but also provided guidance to thecommander of the Korean Marine Brigade and othersas I Corps Coordinator for United States and Fre eWorld Military Assistance Forces and, as Senior U .S .Advisor for I Corps, coordinated the activities of Lieu -tenant General Lam's ARVN units with those of hisown .

General Cushman was well prepared when he as-sumed the post of top Leatherneck in Vietnam . Agraduate of the Naval Academy (Class of 1935) an drecipient of the Navy Cross as a battalion commanderduring the recapture of Guam, Cushman served fou ryears on Vice President Richard M . Nixon ' s staff asAssistant for National Security Affairs . In addition hecommanded the 3d Marine Division in 1961, and late rwhile serving as Commanding General, Marine Corp sBase, Camp Pendleton, headed both the 4th Marin eDivision Headquarters nucleus, and the newly or-ganized 5th Marine Division . In April 1967, he wasappointed Deputy Commander, III Marine Am-phibious Force . Three months later he assumed th eduty of Commanding General, III MAF, replacingLieutenant General Walt .

During his tenure, General Cushman managed II I

LtGen Hoang Xuan Lam, left, Commanding General, 1 Corps ; LtGen Richard G. Stilwell,USA, Commanding General, XXIV Corps; and MajGen Ngo Quang Truong, right, Com-manding General, 1st AR VN Divirion, pose with Gen Cao Van mien, center left, Chair -man of the South Vietnamese Joint General Staff during the latter's visit to Phu Bai .

Department of Defense Photo (USA) SC649680

6

HIGH MOBILITY AND STANDDOWN

III MAFCOMMAND RELATIONSHIP S

CINCPA C

FMFPAC

M ACV

I CORPS

III MAF -----

-------------- - USARV

2D ROKM CBDE

1ST MAR DIV

•

XXIV CORPS

•

23D INF DI V

1ST MAW

3D MAR DI V

d

— — — — OP Control

'h

$ Admin Control• • • • • • Command Less OP Contro l

Coordination

101 ABN DI V

1ST BDE5TH INF DIV

• • •

• • • • • • • • • • •

MAF's growth from a force of 97,000 Marine, Navy ,and Army personnel to 172,000 by the beginning of1969. His responsibilities, however, changed little .Like General Walt, Cushman was charged with thedefense of I Corps Tactical Zone . Although thesmallest in area and population, ICTZ was the mos tstrategically located of the four South Vietnames emilitary regions due to its proximity to major enemyinfiltration and supply routes, and base areas in Laos ,the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), and North Vietnam .Cushman would be replaced in March 1969 by Lieu -tenant General Herman Nickerson, Jr ., a highly deco -rated veteran of World War II and Korea, and forme rcommanding general of the 1st Marine Division inVietnam from October 1966 to May 1967 .

Opposing American, South Vietnamese, andKorean forces within the boundaries of I Corps, the

Demilitarized Zone, and contiguous North Viet-namese and Laotian border regions, were 123 NorthVietnamese Army (NVA) and 18 Viet Cong (VC) com -bat and support battalions composed of close to 89,00 0enemy troops . According to allied intelligence esti-mates of early 1969, 42,700 were North VietnameseArmy regulars while 6,500 were Viet Cong main an dlocal force unit members . In addition, there were ap-proximately 23,500 guerrillas and 16,000 political andquasi-military cadre . Added to these known Nort hVietnamese and Viet Cong units were additional in-fantry and support battalions with an estimatedstrength of 30,000 troops located within striking dis-tance of the corps tactical zone .

Five different headquarters directed enemy opera-tions within the corps tactical zone to varying degrees :the B-5 Front which controlled troops along the DMZ ;

PLANNING THE CAMPAIGN

7

Marine Corps Historical Collectio n

LtGen Herman Nickerson, Jr., right, relieves GenCushman as Commanding General, III Marine Am-phibious Force in formal ceremonies at Da Nang o n26 March 1969. LtGen Nickerson previously served inVietnam as Commanding General, 1st Marine Divi-sion and Deputy Commanding General, III MA E

7th Front which directed units within Quang Tr iProvince ; Tri-Thien-Hue Military Region which hadcharge of units in Quang Tri and Thua Thie nProvinces ; troops attached to the 4th Front whichoperated in Quang Nam and Quang Tin Provinces ,and the city of Da Nang ; and units subordinate toMilitary Region 5 which operated in Quang Nga iProvince . The five political and military headquarterswere thought to receive orders from the Central Officefor South Vietnam (COSVN), which in turn was sub-ject to the directives of the Reunification Departmen tof the North Vietnamese Lao Dong Party . *

The dramatic and massive corps-wide attack, con-centrated in the northern two provinces, and resul-tant severe losses during the Tet and post-Te tOffensives of 1968, forced the enemy to reevaluat ehis military position as the new year began . As a result ,Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army strategy an dtactics shifted from an attempt to win an immediat e

*COSVN, the North Vietnamese forward control headquarters ,consisted of a few senior commanders and key staff officers organizedas an extremely mobile command post . Thought to be located inTay Ninh Province, III Corps, near the Cambodian border, COSVN ,although targeted by numerous American and South Vietnames eoperations, eluded capture throughout the war .

victory to an attempt to win by prolonging the con-flict . Large unit assaults were to be undertaken onl yif favorable opportunities presented themselves ; smallunit operations, particularly highly organized hit-and -run or sapper attacks, attacks by fire, harassment, ter-rorism, and sabotage would be used more extensive-ly . The Communists hoped to inflict troop losses b ycutting allied lines of communication, attacking base ,rear service, and storage areas while conserving thei rmilitary strength, defeating the pacification effort, an dstrengthening their negotiating position at Paris .Through such actions the enemy hoped to maintai nan aura of strength and demonstrate to the South Viet-namese populace that its government was incapabl eof providing security for its people .

The differences in terrain and population north an dsouth of Hai Van Pass, which essentially bisected th ecorps tactical zone, resulted in markedly different mili -

tary situations by the end of 1968. In the north, withless than a third of the zone's population, the enem ytended to concentrate regular units in the uninhabit-ed, jungle-covered mountain areas, close to bordersanctuaries . The war in the north, then, was one fough tbetween allied regular units and North Vietnames eArmy regiments and divisions . It was, to draw an anal -

ogy, "like the Army fighting the Japanese in Ne wGuinea—inhospitable jungle, mountainous terrain ;the enemy being not little guys in black pajamas, bu tlittle guys in well-made uniforms and well-equippe dand well-led, and certainly well-motivated ." 2

Faced with a smaller population base and a some -what weaker infrastructure in the northern tw oprovinces, and pursued at every turn by allied forces ,enemy strength by year's end had dwindled to abou t29 battalions from a high of 94 in mid-1968 . The al -lied shift to a more mobile posture and the satura-tion of the remote mountain regions of western Quan gTri and Thua Thien Provinces with numerous patrols ,sweeps, and ambushes resulted in the opening of vas tareas of hitherto uncontested enemy strongholds, ex -posing havens and supply caches . Further, it allowe dallied forces to exploit the advantages of the helicop-ter to the fullest, which permitted the massing ofregimental or multi-regimental-size units anywher ewithin the provinces in a matter of hours . Allied oper-ations north of the Hai Van Pass by the end of 196 8had produced a yearly total of almost 40,000 enem ycasualties, forcing both North Vietnamese and VietCong units to withdraw in an attempt to regroup ,reindoctrinate, refit, and prepare for the winter-spring

8

HIGH MOBILITY AND STANDDOWN

offensive scheduled to begin in the early months o f

1969 .

The three provinces which constituted southern ICorps posed a contrasting problem to that of th enorthern provinces . The large population base an dstronger enemy infrastructure, built up over many yearsin the region south of Da Nang and around QuangNgai, created a continuous threat to the large popu-lation centers and allied military complexes, whic hwere, in spite of the best attempts, the targets of fre-quent enemy ground and rocket attacks . Popula-tion and territorial security was progressing, albei tslowly, and by the end of 1968, 69 percent of th ecivilian population, according to allied statistics, live dwithin secure villages and hamlets . As enemy strengt hin the north diminished and engagements becam eprogressively rarer, the enemy was able not only t omaintain current force levels in the south, but eve nto increase them slightly. The 42 enemy battalions i nsouthern I Corps in mid-1968 were increased to abou t54 by the end of the year .3

Taking advantage of favorable weather and the al -lied out-of-country bombing pause, which went int oeffect on 1 November, the enemy renewed efforts tobuild and repair strategic roads, greatly expandin gresupply capabilities within the corps tactical zone an dsurrounding border areas . With the infusion of menand material from the north, tactical redisposition offorces, and increased determination to carry on th efight, the Communists began the new year as they ha dbegun the previous year—seeking the overthrow o fthe South Vietnamese Government and the reunifi-cation of the two Vietnams under Communist domi-nation . III MAF was ready to ensure that the enem ydid not succeed . '

Strategy: A Reevaluation of Prioritie s

In 1969, the sixth year of direct United States com-bat operations in Southeast Asia, the basic issues ofthe war remained largely unchanged . The Viet Cong ,supported by regular North Vietnamese troops, con-tinued to seek control over South Vietnam by attempt-ing to destroy the existing governmental structure andsubstituting in its place one of Communist domina-tion . On the other hand, the Government of theRepublic of South Vietnam, with allied assistance ,sought to check the VC and NVA assaults by buildin ga viable nation immune to Communist overthrow . Toaccomplish this, the South Vietnamese Governmentasked for and received United States economic and

Courtesy of Maj Charles D . Melson, USM C

Enemy troops assemble in preparation for battle . Th eRussian-designed 7 .62mm automatic rifle each carrieswas the standard rifle of North Vietnamese Army sold-iers and of guerrillas fighting in South Vietnam .

military support, particularly the manpower, mobili-ty, and firepower of the United States Armed Forces .

In the four years prior to 1969, the United State spresence grew rapidly as did its preoccupation withsuccessful military operations. The protection and for-tification of South Vietnam 's political, economic, andsocial institutions had been, to a large extent, left t oits own government, and improvement and moderni-zation of its combat power had received little empha-sis . The advisory effort of the 1950s and early 1960shad become United States direction and prosecutio nof the war. The realization, both in Washington an dSaigon, that the enemy had the capability of launch-ing a major offensive in 1968 led to greater emphasi son meaningful programs, leading to increased popu-lation security, a stable government, and a militarystrategy designed to seize the initiative . These goals ,combat operations to defeat the enemy and promot esecurity, increased effort to improve and moderniz ethe Vietnamese Armed Forces, and emphasis on build-ing a viable state, were to receive equal attention.5 Th etransition, then, was to turn the course away fro m"Americanization of the war" toward "Vietnamizatio nof the peace ."

PLANNING THE CAMPAIGN

9

For the enemy, too, 1969 was a year of transition .From 1965, the main thrust of Viet Cong and NorthVietnamese strategy was to match the United Statestroop buildup and endeavor to defeat the allied force son the battlefield, a strategy that was followed unti lTet of 1968 . The failure of the Tet and post-TetOffensives resulted in the reformulation of strategyand tactics . North and South Vietnamese Communis tleaders set forth a new, pragmatic strategy that dis-missed the possibility of a total victory on the fiel dof battle over United States and South Vietnames eForces, seeking instead to parlay limited military vic-tories into withdrawal of U.S . troops, establishmen tof a coalition government, and ultimate Communis tpolitical victory in South Vietnam . It was a strategydesigned to weaken and exhaust the allies . As a cap-tured enemy document noted : "For each additionalday [U.S . troops] stay, they must sustain more casual -ties . For each additional day they stay, they mus tspend more money and lose more equipment . Eachadditional day they stay, the American people willadopt a stronger anti-war attitude, as there is no hop eto consolidate the puppet administration and Army . "6

Tactics, like overall strategy, were to change . Northand South Vietnamese Communist leaders champi-oned the more frequent use of small unit tactics i nthe form of ground attacks or attacks by fire agains tpopulation centers, economic areas, and allied bases ,while still maintaining the option of large unit actions .They emphasized the importance of the politica laspects of the war and moved to bolster their politi-cal appeal in the South by establishing a forma lgovernmental structure . They prepared for either pro-tracted warfare or a ceasefire, while trying to broade ntheir options in South Vietnam, and enunciating theirmajor demands at the on-going peace negotiations i nParis . The basic enemy campaign plan for South Viet-nam aimed to blunt the allied security program andto foil attempts to Vietnamize the war .

With the first large commitment of United Statestroops to the war in 1965, U .S . strategy focused onassisting the Government of South Vietnam and it sarmed forces in defeating Communist subversion an daggression . This strategy stressed military operations ,and advisory and financial assistance to aid in creatin ga secure environment, necessary for the success of na-tional development programs . Further, efforts wer emade to encourage and assist the South Vietnames ein assuming greater responsibility for the developmen tand maintenance of a free and independent nation .

Various operational concepts to support this strate -

gy were developed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS )and Commander-in-Chief, Pacific (CinCPac), wit hprimary emphasis on maintaining maximum pressureagainst the enemy' s disruptive and war-making capa-bilities through three interrelated undertakings . Firstwere the destruction of the Viet Cong main and Nort hVietnamese Army forces in South Vietnam, forcing theNVA to withdraw, and the separation of the VC unitsfrom the population by providing a protective shiel dthrough ground, air, and naval offensive operationsagainst the remaining enemy main force units . Thesecond undertaking involved the establishment of amilitarily secure environment within which the govern-mental apparatus of South Vietnam could be extend-ed, consolidated, and sustained. This entailedaccelerating offensive operations against Viet Con gguerrilla and main forces, with priority being give nto the elimination or neutralization of the enemy's po-litical and military infrastructure while simultaneousl ydeveloping and improving the Republic's armed an dsecurity forces . Third was the improvement of the na -tional development effort through a number of in-tegrated security, political, economic, and socialprograms.

Although all three of these undertakings were con-ducted simultaneously well into 1968, priority wasgiven to the first operational goal . Military operationsdesigned to inflict unacceptable casualties on the ene -my and thereby bring about a successful outcome t othe war were stressed . A strategy of attrition, whilenever formally articulated, was adopted . As GeneralWilliam C. Westmoreland, Commander, UnitedStates Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, unti lJuly 1968, stated :

Our strategy in Vietnam is to secure our bases which areessential if we are to fight troops and sustain combat ; t ocontrol populated and productive areas, . . . to neutralizehis [the enemy's] base areas which are in the main situated. . . along international borders, . . . to force the enemyback, particularly his main forces, back to peripheral areasand to contain him there . Next to interdict infiltration . An dfinally to inflict maximum attrition on his ranks . '

In short, until mid-1968, "it was to grind down th eenemy using the combined forces available in SouthVietnam . "8 The other two operational goals receivedrelatively little in terms of effort and resources .

As allied losses declined and territorial security im -proved following the enemy's failed Tet and post-Te t

Offensives, greater emphasis was placed on popula-tion security and improvement of South Vietnam ' sArmed Forces . Out of this change in operational em-

10

HIGH MOBILITY AND STANDDOWN

phasis evolved a balanced approach which was to be -come the guiding principle for all future allie doperations . In September 1968, General Creighton W.Abrams, General Westmoreland's successor at MACV,advanced the "one war" concept which in essenc erecognized no such thing as a separate war of big unit sor of population and territorial security. Under thi sintegrated strategic concept, allied forces were to car-ry the battle to the enemy simultaneously, in all area sof conflict, by strengthening cooperation between U .S.advisors and commanders and their South Vietnames emilitary and civilian counterparts . Major elements ofthe "one war" concept were population security ,modernization and improvement of South Vietnam' sArmed Forces, and combat operations, each to receivethe highest priority, and each to be kept abreast ofthe other and moving forward with the ultimate aimof ensuring a strong and viable nation. No single ele-ment was to be allowed to overshadow the other two .

Under this concept, all allied forces were to be mar-shalled into a single integrated, all-out attack agains tthe enemy's forces, organization, activities, and facil-ities . Working in close coordination with the ArmedForces of the Republic of Vietnam and other govern -mental agencies, each element within the overall ef-fort was to be assigned a mission and related tasks mos tappropriate to its particular capabilities and limita-tions . Emphasis was to be placed on combined oper-ations in which Free World Military Assistance Forcesand Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces would joi nin an effort to increase the latter's experience and con-fidence . In all operations, mobility and flexibility wereto be stressed ; as the enemy situation changed, exist-ing plans were to be rapidly modified to counter o rcapitalize on the changing situation. The strategy o fattrition was dead . As General Abrams pointed ou tto his major field commanders in mid-October :

The enemy's operational pattern is his understanding tha tthis is just one, repeat one, war . He knows there' s no suchthing as a war of big battalions, a war of pacification or awar of territorial security . Friendly forces have got to recog-nize and understand the one war concept and carry the battleto the enemy, simultaneously, in all areas of conflict . In theemployment of forces, all elements are to be brough ttogether in a single plan—all assets brought to bear agains tthe enemy in every area, in accordance with the way th eenemy does his business . . . . All types of operations areto proceed simultaneously, aggressively, persistently andintelligently—plan solidly and execute vigorously, never let-ting the momentum subsides

The "one war" concept embodied Abrams' long-hel dbelief that both the multi-battalion and pacification

wars were mutually supporting aspects of the sam estruggle. *

As a corollary to the "one war " concept, significan temphasis was to be given to the Accelerated Pacifica-tion Campaign (APC), initiated in November 1968 .Recognizing that insurgency would fail if cut off fro mpopular support, allied efforts were to be directe dtoward denying the enemy access to population andrice-growing centers, which in turn would deprive hi mof his mobility and force him to divert combat troop sto logistical duties for which he would otherwise im-press local laborers .

Guided by these principles, the South Vietnames eJoint General Staff (JGS), in coordination with Gener-al Abrams' MACV staff, issued two documents late in1968 which set forth strategy for the conduct of th ewar in the coming year . The 1969 Pacification and De-velopment Plan was the first attempt by the Sout hVietnamese Government to present in a single docu-ment the strategy, concepts, priorities, and objective swhich were to guide the total pacification effort . Is -sued on 15 December by South Vietnamese PremierTran Van Huong and members of the newly forme dCentral Pacification and Development Counci l(CPDC), it was to take effect with the termination o fthe Accelerated Pacification Campaign in February1969 . Although a unilateral plan, it was considere dto be directive in nature for all allied forces . Theprimary objectives of the plan were to provide at leas ta measure of security for 90 percent of the South Viet-namese population by the end of 1969, and extendnational sovereignty throughout the country b yeliminating the Viet Cong Infrastructure, strengthen-ing local government, increasing participation in self -defense forces, encouraging defection among enem yunits and their supporters, assisting refugees, combat-ing terrorism, and promoting rural economic develop-ment and rice production .

*In commenting on the "one war" concept, promulgated b yGeneral Abrams, General Westmoreland stated : "It was not Abramsthat did it, it was the changed situation which he adapted to. Th echange was the situation, it was not the personality because, GeneralAbrams was my deputy for over a year . He and I consulted abou talmost every tactical action . I considered his views in great depthbecause I had admiration for him and I'd known him for many years .And I do not remember a single instance where our views and th ecourses of action we thought were proper, differed in any way." Con-tinuing, "there was no change in strategy . But there was a changein the situation, a profound change after the defeat of the Mt Offen-sive." (Gen William C . Westmoreland intvw, 4Apr83, pp . 7, 19 [Oral -HistColl, MCHC, Washington, D .C.])

PLANNING THE CAMPAIGN

1 1

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) A19254 0

A Marine infantryman scrambles down a steep moun-tain slope during a typical patrol in I Corps' rugged,jungle-covered mountainous terrain in search of Nort hVietnamese Army Forces, base camps, and cache sites .

The four corps and Capital Military District com-manders were given primary responsibility for execut-ing the pacification plan on the basis of province plan sprepared under corps supervision and reviewed in Sai-gon . To focus and ensure success for the effort, inter-mediate goals were established . These goals, to be ac-complished by 30 June 1969, were deliberately set hig hin order to exact maximum effort .

The second document issued was the CombinedCampaign Plan (CCP) for 1969, which provided basi cguidance for all Free World forces in the conduct ofmilitary operations in South Vietnam . The 1969 pla ninaugurated a number of changes in annual campaig nplanning which strengthened the status of the Sout hVietnamese Joint General Staff . Unlike previous cam-paign plans, which were prepared by MACV, the 1969plan was prepared by the JGS with assistance fromMACV. In addition, U.S . forces were for the first tim elisted among Free World forces instead of separately ,and more significantly, the plan, once drawn up, wassigned by each of the national commanders .

The basic assumptions included in the plan re-mained unchanged from those of 1968, except for ac -

knowledging the on-going Paris peace negotiation sand assuring that allied force levels would remain sta-ble throughout the year. Under the plan, United State sand South Vietnamese troops were to continue mobil eoperations against enemy forces and bases, whilescreening population centers against attack and in -filtration. The plan also directed continued extensionof government control by securing major cities, towns ,and military installations, and denying enemy acces sto important economic regions, rail and road links ,and centers of government . Again emphasized werethe need for population security, elimination of enemyinfrastructure, development of local self-defense forces ,and civic action programs, but to a much greate rdegree than similar programs had received in previ-ous campaign plans .

Twelve major objectives and goals were enumerate dfor use in measuring progress . As compared with th e1968 plan, the 1969 campaign plan reduced and sim-plified the list, making it more meaningful and mor ereasonably attainable than were the percentile goal sused in the past. The goals established for Free Worl dforces varied : defeat Viet Cong and North Vietnames earmed forces ; extend South Vietnamese Governmen tcontrol; modernize and raise the level of South Viet-nam combat readiness ; inflict maximum enemycasualties; increase the percentage of territory andpopulation under South Vietnamese control throughan expanded pacification effort ; reduce the enemy'sability to conduct ground and fire attacks against mili-tary and civilian targets ; destroy or neutralize enemybase areas ; enhance the effectiveness of provincial secu -rity forces ; secure vital lines of communication ; neu-tralize the enemy's infrastructure ; increase the numbe rof Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army deserters ;and, maximize intelligence collection and counter -intelligence activities . In order to make substantialprogress in achieving these goals, allied militaryresources were to be applied to critical areas, with econ -omy of force being practiced in less essential areas .

In ICTZ, allied forces were to be committed primar-ily to offensive operations in order to destroy enem yforces throughout the tactical zone and those whic hmight cross the Demilitarized Zone and Laotian bord-er . Operations were also to be conducted to destro yenemy base areas, and to protect the major populationcenters of Hue, Da Nang, Quang Ngai, and the mai nlines of communications, especially Routes 1 and 9 .Pacification activities would be concentrated on th epopulated coastal areas surrounding the major citie sand extended to other populated areas along Route 1 .

12

HIGH MOBILITY AND STANDDOWN

In essence, the 1969 country-wide Combined Cam-paign Plan abandoned the earlier concept of a pro-tective shield of containment, and both emphasize dand implemented the concept of area security and con-trol, while again stressing the spirit of the offensiveand relentless attack against the enemy. It recognizedboth the enemy's political and military threats and ad-vocated expanded spoiling and preemptive operation sagainst all types of enemy organizations and facilities ,with particular emphasis placed on eliminating th eViet Cong Infrastructure. Further, it recognized thatthere was just one war and the battle was to be car-ried to the enemy, simultaneously, 'in all areas of con-flict . Friendly forces were to be brought together i na single plan against the enemy in accordance wit hthe way he operated . "The key strategic thrust," as stat-ed in the MACV Strategic Objectives Plan approve dby General Abrams early in 1969, was "to provid emeaningful, continuing security for the Vietnames epeople in expanding areas of increasingly effective civi lauthority." As envisioned by MACV and the JGS, th e"one war" concept was to be forcefully implemente don all fronts in 1969. As General Abrams stated toa gathering of his major field commanders early i nJanuary :

Pacification is the "GUT" issue for the Vietnamese . This i swhy I think that we cannot let the momentum die down .I started off by saying that I think we have the cards. I be-lieve that . But the artistry in this situation is going to b eto play the cards at the proper time and in the proper place .We do not have so many extras that we can afford to blunde raround and put forces where the enemy isn't and where th epacification effort doesn 't need it . It is going to require th eutmost in professional work and professional judgment dur-ing the next weeks to ensure that we play our cards in th emost effective way. If we do not and we get sloppy, pacifica-tion is going to really suffer . You can't let the old steam rolle rget going and not feed it fuel and expect it to keep going? 0

I Corps Planning

On 26 December 1968, South Vietnamese, Korean ,and American commanders in I Corps Tactical Zon eissued their Combined Campaign Plan for 1969 .Designed to implement the objectives outlined in th enationwide campaign and pacification plans, thisdocument was to provide basic guidance for the oper-ations of Marines and allied forces in ICTZ through -out the coming year.

The drafters of the plan assumed that the NorthVietnamese and Viet Cong in I Corps would continu eto follow the strategy used during the campaigns o flate 1968— that of concentrating men and materiel in

attacks on population centers in order to inflict adefeat on the ARVN and incite a popular uprising thatwould culminate in either the overthrow of the Sout hVietnamese Government, or its replacement by a coa-lition government which would include representativesof the National Front for the Liberation of Sout hVietnam .

Due to a number of decisive tactical defeats, heav ycasualties, and failure to gain popular support by 1969 ,allied planners noted :

Realizing that he cannot win a military victory, the enem yis apparently resorting to a "fighting while negotiating "strategy. In adopting such a strategy, he now hopes to gai npolitical advantage at the conference table through continue doffensive action in RVN [Republic of Vietnam] . The enem yis expected to expand his efforts to control the rural area sand strengthen his infrastructure as a base for further action .,

In pursuit of this goal, the planners declared, th eNVA and VC in I Corps would endeavor to "wear downand eliminate RVNAF [Republic of Vietnam ArmedForces] and Allied forces to the maximum extent pos-sible and to draw friendly forces away from urban area sand thereby relieving pressure on those enemy forcesattacking the urban areas ." 12 In the attack on the ur-ban population, Communists forces would continu eto rely on such standard tactics as assassination, rock -et and mortar attacks on vital areas and key installa-tions, and direct assaults on isolated units, outposts ,and towns . These actions were aimed, the planner snoted, at demoralizing allied forces, discrediting th eSouth Vietnamese Government, and disrupting it spacification effort .

To meet and eliminate the enemy threat, campaig nplanners divided the opposing force into twocategories, the VC and NVA main force units oftenfound in remote areas and local VC guerrilla units an dtheir supporters, concentrated in and around urba npopulation centers . They assigned a distinct yet over-lapping function to each allied unit : Korean, Ameri-can, and ARVN regulars were to focus on destructio nof the enemy's main forces, neutralization of base andlogistical areas, and prevention of infiltration of popu-lation centers . Regional and Popular, People's Self-Defense, and National Police forces were to weed ou tand eliminate Viet Cong local force units and infra -structure. These auxiliaries were to furnish "securityfor hamlets and villages and will defend the LOCs[lines of communication], political and economi ccenters and government installations . They will als oparticipate in and coordinate with the ARVN regular

PLANNING THE CAMPAIGN

1 3

Abel Papers, Marine Corps Historical Cente r

LtGen Robert K Cushman, left, Commanding General, III Marine Amphibious Force ;

LtGen Hoang Xuan Lam, Commanding General, I Corps ; and BGen Dong Ho Lee, right,Commander, 2d Republic of Korea Marine Brigade, sign the I Corps Combined Cam-paign Plan for 1969, outlining allied coordination and assistance policies for I Corps.

forces in the protection of cities and provincial anddistrict capitals" 1 3

The major task assigned to the regular forces un-der the plan was to locate and "systematically neutral-ize " the enemy ' s base areas scattered throughout thetactical zone, predominantly in the mountains adja-cent to the Laotian border . Allied troops were to con-centrate on those enemy command, control, andlogistical facilities which "directly affect the selectedRD [Revolutionary Development] priority areas, ke ypopulation and economic centers, and vital commu-nications arteries" 14 Priority was given to those enemybase areas within striking distance of Dong Ha andQuang Tri City (Base Area 101), Da Nang (Base Area112), and Quang Ngai City (Base Area 120 .* For themore remote bases where complete neutralization an dpermanent denial was impossible, "repeated air strikeswith random pattern ground operations " were to b e

*Each enemy base was assigned a three-digit number . The firs tdigit represented the country in which it was located (1 for SouthVietnam and 6 for Laos), while the last two digits indicated se-quential position of discovery by allied troops .

used to "create insecurity, disrupt command channels ,and deter stationing and movement of VC/NVA

forces " within those areas 1 5 The drafters of the cam-paign plan were convinced that :

The destruction of the enemy's command, control, and

logistics facilities will contribute to his eventual defeat . Theneutralization of these bases will also require the enemy t oplace greater demands on the people for more manpowe r

and resources . As these demands increase, the people wil lbecome more susceptible to friendly psychological opera-tions . This will support the objective of assisting the GV N

in expanding territorial control 1 6

"Territorial control" or territorial security was stressedby the authors as the primary objective of all allie d

activity in I Corps :

The campaign to provide sustained territorial security i nthe countryside and concurrently to introduce political, eco-nomic and social reforms which will establish condition sfavorable for further growth and stability, is just as impor-tant as anti-aggression operations . Operations to annihilatethe enemy, while clearly essential to pacification, are by them -selves inadequate . The people must be separated and wonover from the enemy."

14

HIGH MOBILITY AND STANDDOWN

Each allied unit was assigned a security function, i naddition to its other allotted duties . American ,Korean, and ARVN regulars, when not engaged inmajor operations against enemy base areas and mai nforce units, were to "prevent enemy infiltration intothe fringes of towns, cities, and areas adjacent to popu-lation" centers by constantly patrolling those areas .1 8They were to reinforce territorial units under attack ,furnish air and artillery support, and assist them i ntheir campaign to eliminate local Viet Cong. Region -al and Popular Force units within the tactical zone wer eto carry out ambushes, cordons, and patrols near in-habited areas, while the National Police and People' sSelf-Defense Forces were to maintain public order andconduct operations aimed at eradicating the enemy' sinfrastructure .

I Corps planners also sought to delineate the ofte nconflicting responsibilities for pacification by requir-ing each locality to be placed into one of five genera lsecurity categories : uninhabited areas, North Viet-namese Army- or Viet Cong-controlled areas, contest-ed areas, areas being secured, and those areasconsidered completely secure. Uninhabited areas en -compassed, that territory just inside the national front-iers which did not contain officially recognizedhamlets . NVA- or VC-controlled areas were regions inwhich the enemy was present and able to exert mili-tary and political influence . In both of these areas, al -lied units were to conduct only transient operations ,with no intention of gaining complete and permanen tcontrol .

Closer to the main population centers were the con -tested areas . Selected as targets for Revolutionary De-velopment activities, these areas were to be cleared

permanently of all organized enemy main force an dguerrilla unit activity by regular forces . In areas in th eprocess of being secured, all "organized resistanc e" wasconsidered to have ceased and the government to b ein the process of destroying what remained of the ene-my's guerrilla network, thereby preventing its re -emergence.

Secure areas, the final category, were densely popu-lated regions where government control was complete ,or where permanent New Life Hamlets (Ap Doi Moi )were being developed . Here the population coul dmove freely without fear of organized enemy attacks ,except for occasional individual acts of terrorism orsabotage, and indirect attacks by fire . In both secureareas and areas being secured, the responsibility fordefense and maintenance of public order rested wit hlocal officials and their principal security forces, th eRF and PF, the PSDF, and the National Police .

The purpose of this regional organization was no tonly to fix responsibility for pacification, but to inte-grate and unify all allied activity. Combat operations ,population and teritorial security, and RVNAF im-provement and modernization were to be equally em-phasized in the "one war" concept as enumerated bythe ICTZ/III MAF Combined Campaign Plan fo r1969 .

Against this background, the battlefields of I CorpsTactical Zone were relatively quiet during the earlydays of 1969 . The Viet Cong's unilateral 72-hour NewYear's truce ended on 2 January, but intermittentfighting took place as allied forces, who had refuse dto recognize the ceasefire, continued both large an dsmall unit operations .

CHAPTER 2

Mountain Warfar eNorthern I Corps— OffBalance—From the Cua Viet, South

Northern I Corps

Arrayed within the provinces of Quang Tri and Thu aThien as 1969 began were the following major Unite dStates headquarters and combat units : HeadquartersXXIV Corps ; 3d Marine Division ; Task Force Hotel ;101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) ; 1st Brigade, 5t hInfantry Division (Mechanized) ; XXIV Corps Artillery ;and U .S . Navy Task Force Clearwater. Generallydeployed along the Demilitarized Zone and Laotia nborder within Quang Tri Province was the 3d MarineDivision, less two battalions of the 3d Marines, wit hthe 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized )under its control, operating throughout the easternportion of the province, primarily within the piedmontand coastal lowlands . Located at Vandegrift CombatBase in western Quang Tri was Task Force Hotel, whic hessentially functioned as 3d Marine Division Forwar dHeadquarters . Deployed within Thua Thien Provincewere the three brigades of the 101st Airborne Divi-sion (Airmobile), headquartered at Camp Eagle, southof Hue and northwest of Phu Bai . Collocated withHeadquarters, XXIV Corps, at Phu Bai Combat Basewas XXIV Corps Artillery, while stationed at Don gHa was the subordinate 108th Artillery Group . TheNav y' s Task Force Clearwater, with the mission of rive rand inland waterway security, operated from a basenear the mouth of the Song Cua Viet in Quang Tr iProvince, with river patrol groups securing the Son gCua Viet and Song Huong (Perfume River), and patro lair cushion vehicle (PACV) elements patrolling inlan dwaterways .

Enemy activity throughout northern I Corps wa slight and sporadic during the early days of Januar y1969 . Along the Demilitarized Zone, units of the 3dMarine Division and 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Divi-sion (Mechanized) faced elements of six North Viet-namese regiments, the 138th, 270th, 84th, 31st, 27th ,and the 126th Naval Sapper, all independent regi-ments of the unlocated B-5 Front Headquarters. Thre eregiments of the veteran 320th NVA Division hadwithdrawn from western and central Quang Tr iProvince for refitting in North Vietnam following theirthird defeat in late 1968.' What enemy activity therewas, was generally limited to infrequent rocket and

mortar attacks on allied positions, ground probes bysquad- and platoon-size units, and attempts at inter-dicting the Song Cau Viet with mines . Artillery firefrom within and north of the Demilitarized Zone ha dall but ceased in December .

Within the central portion of Quang Tri Province ,units subordinate to the 7th Front, including threebattalions of the 812th Regiment, were for the mostpart pulled back into jungle sanctuaries on the Quan gTri Thua Thien provincial border for resupply and in -fusion of replacements . These three units were badl ymauled during the 1968 Tet and post-Tet Offensives ,and their forward base areas and cache sites destroyedby Marine and ARVN search and clear operations dur-ing the late summer and fall campaigns. Enemystrength at the end of January, within the Demilita-rized Zone and Quang Tri Province, was estimated a t36,800, approximately 2,500 more than the Decembertotal . Of these, more than half were confirmed to b ecombat troops .

In Thua Thien Province the enemy situation wa ssimilar . North Vietnamese Army units, with the ex-ception of small forward elements of the 4th and 5thRegiments, had been withdrawn into the A Shau Val -

ley and Laos under constant U.S . and ARVN pressureduring the previous year. These forward elements di dconduct occasional attacks by fire, but were forced toconfine much of their effort to attempts at rice gather-ing and survival in the foothills of the province . VietCong local force units and the Viet Cong Infrastructureremained under steady pressure from Army, ARVN ,and provincial forces, and likewise devoted much o ftheir energy toward survival and avoiding discovery .End-of-January estimates placed enemy strength with -in the province at 15,200, a 25-percent increase overDecember figures .

To the west, in the A Shau Valley and beyond, therewere signs of increasing enemy activity. Roadwork wasbeing conducted on Route 548 in the valley and o nRoute 922 in Laos . Vehicular traffic and troop move-ment was light at the beginning of the month, bu tsoon picked up as January progressed, particularly i nand around Route 922 and enemy Base Area 611 i nLaos .

15

16

HIGH MOBILITY AND STANDDOWN

SouthChinaSpa

Hue

Phu Ba i

x x

1►51 320th =IHQ6~5 Front

II I

1►ml 4 th

In

70138th 1l 86t h

DMZ nu

II I

1►nl 52dIII I

~~•n n31e• 1~~1 h

1►I 64thCon Thiel

27th

Cam Lc) .

* 'Jong H a

xx

Quang Tr i308th

ri1 HQ Front

I q

•Khe Sanh7th

B A114

Enemy Order of Battl eNorthern ICTZJanuary 196 9

kilometers 0

25

50

7 5M 88th

812th J

II I

M102d

C BA101

H QTri-Thlen-Ho eMilitary Regio n

6thLaos

5thIm

9th4,h1 •~~1► I

29thDa NanB A

60 7803 d

I_4III I

MIII I

I

l

In

IC4I

OffBalance

While the enemy generally avoided contact in Janu-ary, American and South Vietnamese forces in north -ern I Corps continued their efforts at keeping him offbalance, striking at his traditional base areas and in -filtration routes, and increasing security within popu-lated areas . Driving deeper into the mountains an dareas bordering the Demilitarized Zone, allied force spushed and probed for evidence of infiltration an dsupply build-up, in order to determine the enemy' sintentions in the months ahead and thwart them be -fore they could be implemented .

Leading the effort in Quang Tri Province was th e3d Marine Division under the command of Majo rGeneral Raymond G. Davis. A veteran of the Guadal-canal, Cape Gloucester, and Peleliu campaigns o fWorld War II and Medal of Honor recipient for ac-tions at the Chosin Reservoir during the Korean War ,Davis assumed command of the division in May 1968 ,following a short tour as Deputy Commanding Gener-al, Provisional Corps, Vietnam .

Under Davis' leadership, the tactical disposition o fthe division would be turned around . No longer con -signed to defensive positions, the 3d Marine Division ,with helicopter support, now would assume a highl ymobile posture, characteristic of Army air cavalry an dairborne operations of 1968 . As General Davis noted :

We had something like two dozen battalions up there alltied down (with little exception) to these fixed positions ,and the situation didn't demand it . So, when the Armymoved into Pegasus to relieve the Khe Sanh operation [i nApril 1968] they applied forces directly responsive to the ene-my's dispositions and forgot about real estate—forgettingabout bases, going after the enemy in key areas—this

See Reference Map, Sections 1-2 7

punished the enemy most . Pegasus demonstrated the deci-siveness of high mobility operations . The way to get it donewas to get out of these fixed positions and get mobility, t ogo and destroy t!ie enemy on our terms—not sit there andabsorb the shot and shell and frequent penetrations thathe was able to mount . So all this led me, as soon as I heardthat I was going, it led me to do something I had never don ebefore or since, and that is to move in prepared in the firs thours to completely turn the command upside down . Theywere committed by battalion in fixed positions in such away that they had very little mobility. The relief of CGs tookplace at eleven o'clock . At one o'clock I assembled the staffand commanders ; before dark, battalion positions had be -come company positions. It happened just that fast .2

In addition to establishing a more mobile posture ,Davis reinstituted unit integrity. For various reasons ,the regiments of the division had slowly evolved int ooperational headquarters which might have any bat-talion of the division assigned . There was constant ro-tation; the 9th Marines, for example, might have abattalion of the 3d Marines, a battalion of 4th Ma-rines, and only one of its own. Thus, as Colonel Rober tH. Barrow, one of Davis' regimental commanders an dlater Commandant of the Marine Corps, noted, th eindividual battalions "felt . . . they were commande dby strangers . Every unit has a kind of personality o fits own, often reflecting the personality of the com-mander, so you never got to know who did what best ,or who would you give this mission to ." 3 Davis changedthat; each regiment, under normal operating circum-stances, would now control its constituent battalions .As General Davis later commented, "it was the keyto our success" 4

As battalions of the division moved from defensiveoperations to more aggressive operations against ele -

MOUNTAIN WARFARE

1 7

ments of the 320th NVA Division during the latterhalf of 1968, the need for helicopters grew. "I was veryfortunate in this," Davis was later to state, " that thelater model of the CH-46 was arriving in-country i nlarge numbers . Whereas it would pick up a platoon ,the old 46 would hardly pick up a squad ."5 In addi-tion, due to his close working relationship with Arm yLieutenant General William B. Rosson, ProvisionalCorps commander, and Lieutenant General Richar d

G. Stilwell, his successor at XXIV Corps, Davis hadthe promise of Army helicopter support if needed.More important, however, was the creation of Provi-sional Marine Aircraft Group 39 and the subsequen tassignment, initially on a temporary basis, of a Ma-rine air commander for northern I Corps who, asGeneral Davis stated, "had enough authority delegat-ed to him from the wing, where he could execut ethings; he could order air units to do things " e* Withhelicopter transport assured, division Marines move dfrom relatively static positions south of the Demilita-rized Zone and along north-south Route 1 and east -west Route 9, the main lines of communication, int othe mountainous regions of Quang Tri Province insearch of the enemy and his supplies .

Davis' concept of mobile operations depended notonly on the helicopter, but on the extensive exploita-tion of intelligence, specifically that gathered by smal lreconnaissance patrols, which he continuously em-ployed throughout the division ' s area of responsibili-ty and which supplemented both electronic andhuman acquired intelligence . Operating within rangeof friendly artillery were the heavily armed "Stingray "

patrols, whose mission was to find, fix, and destro ythe enemy with all available supporting arms, an d

rapid reinforcement, if necessary. In the more remot eareas, beyond artillery range, he used "Key Hole"patrols . Much smaller in size and armed with only es-sential small arms and ammunition, the function o fthese patrols was to observe? The 3d Marine Division ,

Davis noted, "never launched an operation withou tacquiring clear definition of the targets and objective sthrough intelligence confirmed by recon patrols . High

*Assistant Wing Commander, Brigadier General Homer S . Hill ,was temporarily assigned to 3d Marine Division Headquarters fo r"operations requiring more than routine air support and used hisnormal position within the Wing to coordinate air operations o nthe spot? ' The assignment of a Marine air commander to norther nI Corps "did not involve any new command structure ." (Col Edwi nH. Finlayson, Comments on draft ms, 25Nov86 [Vietnam 69 Com-ment File, MCHC, Washington, D.C .])

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) A192746

MajGen Raymond G. Davis led 3d Marine Division .

mobility operations [were] too difficult and comple xto come up empty or in disaster." 8

Armed with information on probable enemy troopand supply locations provided by reconnaissanc epatrols and other intelligence sources, such as radi ointercepts, 3d Division Marines would advance rapidl yinto the proposed area of operations. Forward artillerypositions, or fire support bases (FSBs), defended b ya minimum of infantry personnel, would be estab-lished on key terrain features . These mutually support-ing bases, constructed approximately 8,000 meter sapart with a 3,000-meter overshoot in order to cove renemy mortars, provided ground troops operating un-der the fan with continuous, overlapping artillery sup-port . Once inserted, Marine rifle companies, and eve nentire battalions, would move rapidly, althoughmethodically, and largely on foot, throughout the areato be searched . Additional fire support bases wouldbe constructed, permitting deeper penetration of thearea of operations .

The purpose of the intelligence collection effort an dsubsequent combat operations, if required, was to pre -vent the enemy from sticking his "logistics nose in -

country." "The [enemy's] first order of business," asColonel Barrow later noted, was to "move all the thing sof war ; all of their logistics forward from the sanctu-aries of North Vietnam, just across the DMZ, or fro mLaos." This movement would take weeks, or possibly

18

HIGH MOBILITY AND STANDDOW N

months. At the appointed time, troops would quick-ly move in, marry up with the cached supplies, an dthen do battle . As General Davis believed and Bar-row later stated :

We must do everything we can to find that stuff, where-ver its exists and obviously destroy it . And if we miss anyof it, we must attempt by vigorous patrolling, radio inter-cept, signal intelligence, recon team inserts, and whateverelse, to find out when any troops were moving in . Maybewe hadn't found their logistics, their caches, and we didn' twant to have the surprise of not finding them until afte rthey had married up and were about to engage us som eplace .9

Thoroughly indoctrinated in the mobile concept ofoperations, Marines of the 3d Division at the begin-ning of 1969 could be found from the Laotian borde rto the coastal lowlands . To the west, elements o fColonel Robert H . Barrow's 9th Marines continuedsearching north of the Khe Sanh plateau in operation sbegun the year before. In the center, the 4th Marines ,under Colonel William F. Goggin, patrolled themountainous areas north of Vandegrift Combat Bas eand south of the Demilitarized Zone . Further east, onebattalion of Colonel Michael M . Spark's 3d Marinescontinued to search areas south of the DMZ and north

of Route 9, while the remainder of the regiment as-sisted the 5th Marines in Operation Taylor Commo nin Quang Nam Province .

On 31 December 1968 and 1 January 1969, teamsfrom the 3d Reconnaissance Battalion were insertedwest of Khe Sanh along the Laotian border, initiatin gOperation Dawson River West . The teams immedi-ately secured seven landing zones, eliminating theneed for preassault artillery and air strikes. On themorning of the 2d, elements of Barrow's 9th Marine sand supporting artillery made simultaneous helicop-ter landings into the secured zones north of Route 9 .The initial assaults were made by Lieutenant ColonelGeorge W. Smith's 1st Battalion, Lieutenant Colone lGeorge C . Fox's 2d Battalion, and Company L, 3d Bat -talion under First Lieutenant Raymond C . Benfatti .A battalion of the 2d ARVN Regiment assaulted sout hof Route 9 to the right of the 2d Battalion, 9th Ma-rines on the 4th . Fire Support Bases Geiger and Smith ,occupied by batteries of Lieutenant Colonel Josep hScoppa, Jr.'s 2d Battalion, 12th Marines, supported th e9th, while an ARVN artillery battery at Fire Suppor tBase Snapper supported the South Vietnamese .

Throughout the three-week operation, Barrow's Ma-rines experienced minimal enemy contact during th e

Infantrymen of the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines move through waist-high elephant grassin search of enemy troops and supply areas around Khe Sanh during Dawson River West .

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) A800506

MOUNTAIN WARFARE

19

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) A80050 3

A solitary Marine moves up a small stream near the abandoned Khe Sanh base, carefullychecking out both banks for hidden North Vietnamese Army supplies and harbor sites .