Context, culture and the role of the finance function in strategic decisions. A comparative analysis...

-

Upload

chris-carr -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of Context, culture and the role of the finance function in strategic decisions. A comparative analysis...

Management Accounting Research, 1998, 9, 213-239 Article No. mg980075

Context, culture and the role of the finance function in strategic decisions. A comparative analysis of Britain, Germany, the U.S.A. and Japan

Chris Carr” and Cyril Tomkinsf

This paper contrasts strategic decision making styles in Britain, Germany, the U.S.A. and Japan, first by reviewing contextual and cultural differences, and secondly through an analysis of 78 strategic investment decisions taken by 71 motor compe nent manufacturers in the four countries. Specific formal strategic and financial appraisal techniques, and subsequent control approaches, are analysed and confirm the longer-term strategic orientation of German and Japanese companies. Anglo- American short-termism reflects a preponderance of strong financial control style companies and over-reliance, particularly in Britain, on high ‘comfort factor’ financial hurdle rates. In many cases this has undermined commitment to international competitiveness and more proactive strategic decisions. Strategic decision making processes, particularly in Britain, have also been more politicked and less attentive to detail. T o counter this, strong financial control style companies should broaden the traditional role of the finance function in strategic investment decisions-a process already under way in the U.S.A. and Germany. Finally a new model is presented, synthesising lessons from this study, and contrasted with more traditional approaches.

0 1998 Academic Press Limited

Key words: strategy; investment; decisions; culture; comparative management.

1. Introduction: context and culture

Though much is known about the strategic styles of British and U.S. companies (e.g. Goold and Campbell, 1987)) little is known of other advanced competitor countries, such as Germany and Japan. Such a comparison is important because, whilst British and U.S. styles are both fairly financially oriented, German and Japanese paradigms may represent longer-term, more strategic approaches to decisions with implications for competitiveness (Hayes and Abernathy, 1980; Hayes and Garvin, 1982; Hayes and Limprecht, 1982). For example, when asked how well does the statement ‘good short-term profits are the objective’ describe your company, only 27% of Japanese companies surveyed by Doyle (1992, p. 21) responded yes, compared to 80% in the

* Manchester Business School, University of Manchester, Booth Street West, Manchester, M15 6PB, U.K. tSchool of Management, University of Bath, Bath, U.K.

Accepted 2 February 1998

1044-5005/98/020213 + 27 $25.00/0 0 1998 Academic Press Limited

214 C. Carr and C. Tomkins

U.S.A. and 87% in the U.K. Germany is also arguably more typical of Continental Europe (Albert, 1994) and some comparative assessment of Continental European and Japanese approaches, as against better documented Anglo-American strategic approaches, seems overdue. This paper focuses on major strategic investment deci- sions and on the role of the finance function in particular.

Differences in strategic approaches are shaped by context and culture, each the subject of rich comparative literatures. With respect to context, given the ‘stability and distinctiveness’ of ‘national business systems’ (Lane, 1992, p. 90; Whitley, 1992, 1996)) Whitley (1992, p. 2) suggests ‘that differences in institutions, interest groups and the nature of firms across societies are crucial to an understanding of how control over organisations and work is exercised and changed’. Thus whilst financial theory stresses commonalities in terms of recommended approaches to capital budgeting, for example, empirical investigations often throw up differences internationally which challenge such assumptions, as for example in the case of Britain and Germany (Carr et al., 1994a; Cam and Tomkins, 1996). Such differences may also constitute formidable sources of competitive advantage for different nations in particular industries (Porter, 1990; Lane, 1992, p. 92; Whitley, 1992)) as for example the car and engineering industries in the case of Germany and Japan.

Such institutional and contextual differences are summarized in Table 1. Taken together, these contextual differences show that within a more stable economic context, characterised by low inflation and interest rates, German and Japanese companies are thought to be less subject to short-termist pressures. Their close relationships with financial institutions render them less subject to stock market pressures or to any threat from acquisition, they are under less pressure to maximise short-term profits and are freer to invest long-term. Internal labour markets provide the necessary skills, motivation and flexibility, particularly in engineering and opera- tional areas, whilst increased wage levels and increasing demands for top quality goods create economic incentives to invest. Yet, Table 1 also poses an important question. If Anglo-American institutions and managerial models are so subject to pressures (particularly short-term pressures) for performance against financial and economic criteria and, hence, are oriented to those performance measures, while countries such as Japan and Germany are subject to much less pressure of this nature, and hence would be expected to be less oriented to such measures, why is it that the economic performance of the former countries is outstripped by the latter? Why is it that the share of world production of the Anglo-American nations of the U.K. and U.S.A. are still falling, most particularly in key technology sectors (Lorriman and Kenjo, 1996, pp. 1 9 0 ~ 1 9 3 ) ~ and that their returns on capital have been, and remain, consistently lower than countries such as Japan? As Table 1 shows, gross return on capital employed in manufacturing in Japan averaged 23% between 1970 and 1987, compared with 15% in both the U.S.A. and Germany, and only 7% in the U.K.

Despite such evidence, the issue of short-termism remains controversial at a national policy level (Marsh, 1990; Ball, 1991; Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte, 1991; Jacobs, 1991; Eltis et al., 1992; Hutton, 1996). Arguably what is needed is a systemic viewpoint, based on a more complete understanding of what is happening at a corporate level (Porter, 1992). At this level, cultural differences must also be considered and Table 2 summarizes some of the key features which have differenti- ated Germany and Japan from their Anglo-American counterparts. Company goals less orientated towards immediate profit and dividend payouts reflect distinctive

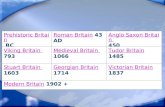

Tab

le 1

Con

text

ual d

zffe

renc

es b

etw

een

the

U.S

.A.,

the

U.K

., G

eman

y an

d Ja

pan

Con

text

ual

fact

ors

U.S

.A.

U.K

. G

erm

any

Japa

n R

efer

ence

s/no

tes

12.2

11.5

4.9

4.8

10.1

8.8

9.4

8.7

7.6

2.9

1.4

4.8

Wor

ld T

rad

e O

rgan

isat

ion,

199

5, T

rend

s and

Sta

tistic

s, T

able

A3.

Wor

ld T

rad

e O

rgan

isat

ion,

199

5, T

rend

s and

Sta

tistic

s, T

able

A3.

EIU

Int

erna

tion

al M

otor

Bus

ines

s, 1

996,

2nd

Qua

rter

. O

EC

D m

ain

econ

omic

ind

icat

ors,

Sep

tem

ber

1996

et a

l. O

EC

D m

ain

econ

omic

ind

icat

ors,

Sep

tem

ber

1996

et a

l.

OE

CD

mai

n ec

onom

ic i

ndic

ator

s, S

epte

mbe

r 19

96 e

t al.

Sha

re o

f w

orld

exp

orts

of

mer

chan

dise

in

1994

(%)

Sha

re o

f w

orld

exp

orts

of

mer

chan

dise

in

1984

(%)

Car

pro

duct

ion

1995

(mil

lion

) G

DP

gro

wth

198

5-19

95 (

% p

.a.)

C

onsu

mer

pri

ce i

ndex

ris

e 19

85-1

995

(% p

.a.)

L

ong-

term

int

eres

t ra

tes

aver

age

1986

-199

5 (%

) S

tock

mar

ket

capi

tali

zati

on/

GD

P 1

996

Gro

ss r

etur

n on

cap

ital

em

ploy

ed m

fr 1

970-

1987

(%

) P

erce

nt o

f pr

ivat

e fi

nanc

ial

asse

ts

inve

sted

in

shar

es

Pro

xim

ity

of c

orpo

rate

rel

atio

n-

ship

s vs

. ar

ms-

leng

th m

arke

t re

lati

onsh

ips

Eas

e of

tak

eove

r P

ress

ure

for

shor

t-te

rm p

rofi

ts

Con

sum

er e

mph

asis

on

hig

h qu

alit

y vs

. low

pri

ce

Inde

x of

wag

e co

sts/

h/

1994

in

mot

or in

dust

ry

Man

uf

unit

lab

our

cost

s av

’ ch

ange

198

5-19

95 (

% p

.a.)

P

erce

nt o

f la

bour

for

ce in

tert

iary

se

ctor

in 1

992

Ava

ilab

ilit

y of

hig

hly

skil

led/

fl

exib

le la

bour

6.3

2.3

4.2

1.5

2.2

5.8

4.4

3.2

2.7

7.1

0

cc,

8.0

9.3

90

15

122 7

25

15

85

Ec

onom

ist, A

ugus

t/S

epte

mbe

r 19

96.

23 9

Lor

rim

an a

nd K

enjo

, 19

96, p

. 3;

Sou

rce

OE

CD

Fina

ncia

l Ti

mes

16.

7.19

96,

p. 2

. 21

Ver

y lo

w

17.5

Low

5.5

Hig

h 2 E P

Ver

y hi

gh

Hir

st a

nd Z

eitl

in,

1989

; Wom

ack

et a

l., 1

990;

N

ishi

guch

i, 19

94.

Ver

y lo

w

Hay

es a

nd A

bern

athy

, 19

80; L

ane,

199

2, p

. 75

L

ow

Hay

es a

nd G

arvi

n, 1

982;

Jac

obs,

199

1;

Lan

e, 1

992;

Lor

rim

an a

nd K

enjo

, 19

96.

Med

ium

P

orte

r, 1

990;

Ebs

ter-

Gro

sz a

nd P

ugh,

199

1.

Fina

ncia

l Ti

mes

, 16.

3.19

95;

Sou

rce

VD

A.

170

Hig

h H

igh

Med

ium

Hig

h H

igh

Low

Low

L

ow

$ B 2. U

P. E. E (D

0

Hig

h

214

148

100

0.7

73

2.7

70

2.8

57

Hig

h

1.0

Econ

omis

t, 3

1.8

.19

96

,~. 9

6.

60

Law

renc

e, 1

996,

p.

9.

Med

ium

L

ane,

199

2; L

ee a

nd S

mit

h, 1

992

Low

L

ow

t4 c

VI

(con

t.)

c ci

ci

Tab

le 1

Con

tinue

d

Eff

ecti

vene

ss o

f co

nfli

ct r

esol

utio

n L

ow

Low

H

igh

Hig

h L

ane,

199

2; G

uill

en,

1994

; Law

renc

e, 1

996,

w

itho

ut r

espe

ct t

o in

dust

rial

re

lati

ons

degr

ee o

f te

chni

cal

vs. g

ener

alis

t co

mpe

tenc

es

oper

atio

ns s

taff

pp.

93-1

01;

Lor

rim

an a

nd

Ken

jo,

1996

.

Ava

ilab

ilit

y of

man

ager

s w

ith

high

M

ediu

m

Low

V

ery

high

H

igh

Hay

es a

nd L

impr

echt

, 19

82; L

ane,

199

2, p

. 75

; L

ee a

nd S

mit

h, 1

992.

Sta

tus/

skil

ls o

f en

gine

ers

and

Med

ium

L

ow

Ver

y hi

gh

Hig

h L

ee a

nd

Sm

ith,

199

2; L

orri

man

and

Ken

jo,

1996

.

Tab

le 2

C

ultu

ral d

zffe

renc

es b

y co

unty

U.S

.A.

Bri

tain

G

erm

any

Japa

n

Pro

fit

is o

nly

real

goa

l (%

of

resp

onde

nts

agre

eing

)' C

ompe

titi

on is

a v

ital

ant

idot

e to

col

lusi

on (

% o

f re

spon

dent

s ag

reei

ng)'

1993

, %

of

afte

r ta

x pr

ofit

s di

stri

bute

d as

div

iden

ds (

aver

age

for

all

com

pani

es)'

Lim

ited

com

mit

men

t to

orga

nisa

tion

s in

res

pect

to

shor

t dur

atio

n

Ave

rage

tenu

re o

f C

EO

up

to 1

98

9/1

99

0 (

year

s)3

Impo

rtan

ce o

f m

anag

ers

havi

ng p

reci

se a

nsw

ers

to s

ubor

dina

tes'

Inne

r di

rect

ed (

% o

f re

spon

dent

s id

enti

fyin

g w

ith

this

cul

tura

l tr

ait)

' In

divi

dual

isti

c (w

eigh

ted

scor

e fr

om m

any

mea

sure

s, m

axim

um 1

00)'

Per

sona

l in

itia

tive

s en

cour

aged

(%

of

resp

onde

nts

agre

eing

)' U

ncer

tain

ty a

void

ing

(wei

ghte

d sc

ore

from

man

y m

easu

res

max

imum

1 00

)' i

See

s co

mpa

ny a

s a

set o

f ta

sks

(% o

f re

spon

dent

s ag

reei

ng)

(% o

f re

spon

dent

s id

enti

fyin

g w

ith

this

cul

tura

l tra

it)'

ques

tion

s (%

of

resp

onde

nts

agre

eing

)4

40

68

51

99

Low

M

ediu

m

68

91

9

7

46

74

33

6

5

69

94

4.5

27

51

89

9

0

35

5

5

24

41

4

0

83

11.4

4

6

65

67

8

4

65

4

1

8

24

40

4

1

Hig

h M

ediu

m

41

4

6

49

9

2

29

'Ham

pden

-Tur

ner

and

Tro

mpe

naar

s, 1

994,

pp.

32,

57,

60,

65

and

71.

'E

cono

mis

t (4-

10 J

une

1994

, p.

147)

. S

ee a

lso

Ran

dles

ome

et a

l., 1

993,

p.

1 3C

arr,

199

2, p

. 83

, bas

ed o

n C

EO

inte

rvie

ws

in v

ehic

le c

ompo

nent

s se

ctor

. 4L

aure

nt,

1983

. 'H

ofst

ede,

19

80, p

p. 2

23,

165.

0

cc, t $ B 2. U

P. E. E (D

0

218 C. Carr and C. Tomkins

financial contexts and ownership structures; but also a set of values distinguished by long-term, almost vocational, commitments made by individuals to their particular organisations, even in terms of developing skills, less transferable in the labour market (see also Dore, 1973; Lawrence, 1980). The obverse of such organisational commitment tends to be a less individualistic approach; less incentives towards more personal initiatives; and a greater tendency towards uncertainty avoiding behaviour. The latter might lead to more participative and thorough decisions, but conceivably at the expense of unduly conservative behaviour?

Whilst contextual and cultural differences undoubtedly influence national strategic decision making styles, we need to explore precisely how such influences manifest themselves, particularly at the interface between strategy and finance, where any short-termism issue might be more pronounced. This article seeks to do this by reporting the findings from 78 case studies of strategic decisions taken by 71 vehicle component manufacturers based in Britain, Germany, the U.S.A. and Japan. The article concentrates on strategic investment decisions (SIDs) and on four aspects of such decisions: capital budgeting techniques, strategic versus financial considerations, subsequent controls, and strategic decision making processes. The remainder of the article is organised as follows. The next section outlines the research approach and methodology used in the study. The following sections then discuss, respectively, differences (and similarities) in approaches in the U.K., U.S.A., Germany and Japan, to each of the four aspects of SIDs already noted.

2. Research approach and methodology

T o facilitate international comparability and understanding of strategic issues, the approach taken here is to concentrate on a single industry sector, vehicle compo- nents. This industry offers a wide range of technologies (including advanced manu- facturing developments) and competitive situations, whilst affording some commo- nality of strategic themes in sharing a common highly international customer base.

The authors have been involved in a longitudinal study of strategic issues in the vehicle components industry for the last 17 years, conducting field research in multiple companies across a variety of countries. Initially, this more focused research covered case studies of 49 vehicle component manufacturers in the U.K. and Germany (24 companies in the former and 25 in the latter).' Forty-two of these companies provided access to in-depth case study of one strategic investment deci- sion (SID), while seven provided access to two, thus providing 56 SIDs for analysis.'

Results from the analysis of these companies and their SIDs have been published elsewhere. As those results inform the present study and are drawn on as part of the data for the present study, they are briefly summarised here together with the details of the progression and methodology of the research to date. First, Cam (1990) provided evidence of weaker strategic decisions in Britain, concluding that such a situation was exacerbated by problems at the interface between finance and strategy.

'German companies were chosen as the first country for comparison with the U.K. in the longitudinal research, partly as exemplars of an alternative paradigm; but also because they have been in the vanguard of technological developments and for their past reputation as the most competitive in Europe (Carr, 1990; Lamming, 1993; Nishiguchi, 1994). 'The focus was restricted to one SID in most companies bearing in mind the complexity of such decisions (Barwise et al., 1986; Rajagopalan et al., 1993).

The Role of the Finance Function in Strategic Decisions 219

This gave rise to the concern with a focus on SIDs and the role of the finance function therein. Subsequently, pilot case studies were carried out and hypotheses developed which suggested an inappropriate balance between attention given to strategic as opposed to traditional capital budgeting considerations, and which also suggested that finance staff might be required to perform a broader role as guardians of strategic decision making proce~ses .~ A skeletal questionnaire was then con- structed, covering the strategic investment ‘story’ and comprising; the roles of key actors (particularly those of the chief executive and the finance function); techniques of formal strategic and financial analysis; the underlying strategies involved; subse quent controls; decision making processes; and any views on international differ- ences.

The questionnaire formed the basis of the case studies of the 56 SIDs in the 49 companies in the U.K. and Germany. In conducting the case studies, the company chief executive was first approached for interview time, together with a request for additional time at least with the most senior finance executive involved. In a few cases, the chief executive had to be substituted by another senior executive conver- sant with the decision (typically the marketing director), and some German compa- nies did not feel that their senior financial executives were sufficiently central to the decisions to merit interviewing. Factory visits were made in most cases and other interviews were made with relevant executives. Interviews averaged between two and a half and three hours with each company and were taped and transcribed. Within the discipline of the questionnaire, the approach entailed obtaining managers’ own perceptions on the events and what determined them, rather than merely testing preconceived notions. The aim was to obtain the managers’ stories of their invest- ment projects with as little direction as possible. Of course, complete avoidance of preconceptions was impossible and managers were prompted to give their explana- tions of wider aspects of managerial control, states of competitiveness, perceptions of rivals abroad, as well as follow through in discussion of interesting points which arose.

This stage of research gave rise to a series of key emergent themes for strategic investment decisions. These themes are documented in Carr et al. (1994a) which provides a detailed write-up of 14 (seven in each country) such decisions. As a further check on these themes, and to investigate control issues in greater detail in the international comparative context, a separate Anglo-German joint venture case was also written up (Cam et al., 1994a, pp. 197-218) in order to compare the approaches of executives in the two countries, when faced with the same original investment project and the same subsequent strategic and financial control problems. The previous analysis of these SID case studies in the U.K. and Germany is thus fully open to inspection in detail in Carr et al. (1994a).

The next phase of this research, based on the same skeletal questionnaire but now informed by a clear understanding of the research issues in strategic investment decisions and the role of the finance function therein, involved similar field research and case studies of 11 vehicle component manufacturers in the U.S. (with research conducted between July and September 1994) and 11 in Japan (during August and September 1995). These studies yielded 14 and 13 further cases, respectively. The extension of the research to the U.S. and Japan added both to the contextual and

3These hypotheses are described and detailed in Carr et al. (1991).

220 C. Carr and C. Tomkins

cultural dimensions underlying the research overall, and, together with the previously gathered data from the U.K. and German companies, forms the focus of this present paper. The present paper focuses on both the cross-sectional data obtained from the companies in the study, as well as data and commentary obtained in the interviews.

The present paper therefore draws on both cross-sectional and interview data from both the previously published case studies of SIDs in the U.K. and Germany and from the recent, as yet unpublished, case studies of SIDs in the U.S. and Japan. In total, 78 SIDs form the data set for this paper drawn from 71 vehicle component manufacturers across the four c ~ u n t r i e s . ~

3. Capital budgeting techniques used on strategic investment decisions

Table 3 reviews our entire database of 78 strategic investment decisions affording details on financial techniques used. We first examined whether companies were using discounted cash flow (DCF) techniques on any types of investment decisions to compare our field based findings with those from established surveys. All companies in our U.S. sample made some use of DCF techniques, a result confirming the increasing use of such techniques suggested by earlier U.S. surveys (Klammer, 1972; Klammer and Walker, 1984). However, only approximately half of our U.K. sample utilised D C F techniques at all, compared with 84% of large U.K. companies surveyed in 1986 by (Butler et al., 1993, p. 56). We suspect that executives personally interviewed are more circumspect in their claims, but the difference in our results may also partly reflect our sample’s wider size spread and the choice of a more traditional industry.

The application of DCF techniques was even less extensive in Germany (28%) and Japan (1 8%). These differences were accentuated for strategic investment decisions (SIDs). Even more significantly, 50% of the U.S.A. sample identified D C F as the key influential measures in SIDs examined, compared with only approx. 12% and 16% in the U.K. and Germany, respectively and none at all in Japan.

Payback period was identified as the key measure for SIDs by only two U.S. companies, but by the majority of those in all other countries: the U.K. 69%) Germany 52% and Japan 69%. Companies’ target payback periods in the U.S.A. and the U.K. averaged, respectively 4 and 3.3 years. In contrast German targets averaged 5.0 years (even after we introduced a somewhat arbitrary figure of 6 years for companies unwilling to stipulate a specific payback period) and Japanese companies averaged 5.5 years, confirming the popular view that these two countries are much longer-term in terms of profit orientation. The vast majority of German and Japanese companies made it clear that on SIDs they were prepared to be flexible even in terms of these targets. Approximately three quarters of U.K. companies and half of those in the U.S.A. were also prepared to countenance some flexibility, concurring that strategic arguments could occasionally be over-riding, but here the degree of any such flexibility appeared extremely limited, with the exception of a number of turnaround cases.5

4Data from five SID cases (two in Germany and three in the U.K.) were insufficiently comprehensive for the cross-sectional analysis used here. Thus, the 78 is made up of the 56 SID cases in the original U.S. and German study minus these five, plus the 14 and 13 cases from the U.S. and Japan, respectively. 5Turnarounds here are not defined in terms of strict criteria, but represent the views of the executives that the financial and competitive positions of their companies (or business units in the case of conglomerates) were precarious. Many of these cases are detailed in Carr et al. (1994a).

The Role of the Finance Function in Strategic Decisions 221

Table 3 The influence of jinancial techniques on strategic investment decisions-vehicle component manufactur- e rs

U.S.A. U.K. Germany Japan

Number of companies interviewed Percent using DCF at all on any investments Number of company SIDs Percent using DCF at all on SID

Percent using DCF as key SID measure Percent using payback as key SID measure Percent using ROCE as key SID measure Percent using ROE as key SID measure Percent using other key measure

Average IRR target % Average payback target-years Percent flexible on payback period Average ROCE target % Average ROE target %

11 100

14 93

50 14 21 0

14

20 4

50 20

n.a.

24 54 26 35

12 69 19 0 0

23

72 25 n.a.

3.3

25 28 25 28

16 52 24 8 0

14 5

86 22 8

11 18 13 8

0 69 8 8

15

5.5 100

11 20

Marsh (1990) has argued that reliance on traditional payback techniques could result in undue short-termism in Britain. However, given that a conclusion of our study (and this paper) is that German and Japanese companies do not emerge as any more financially sophisticated than the U.K. in terms of the financial analyses of SIDs, the main problem may simply be that hurdle rates are unduly high in Britain. Average internal rate of return (IRR) targets, for companies prioritising these mea- sures in SIDs, were highest in the U.K. at 23%6, compared with 20% in the U.S.A. and 14% in Germany, whilst no Japanese company prioritised IRR. Again German companies generally, and even some U.K. companies, treated IRR targets flexibly; but in the U.S.A. any such leeway was almost always tightly defined, with absolute floor levels for IRRs set at an average of 13%) more or less corresponding to their cost of capital. As one U.S. Finance Vice President put it ‘I have final sign-off responsibil- ity and I will not go one cent below that figure’.

Several companies in all four countries prioritised return on capital employed (ROCE) measures, reflecting all round operating company targets, these being set at approx. 25% in the U.K., 22% in Germany, 20% in the U.S.A. and 11% in Japan. One Japanese firm prioritised return on equity (ROE), setting a target of 20%) and two German companies were happy to set ROE targets of approx. 8%) little more than their cost of capital. ‘Other measures’ involved rules of thumb, such as, in the U.S.A., valuing acquisitions as a multiple of operating cash flow (though IRR was still calculated); in Japan, the common rule of thumb on overseas investments was to

6Please note that this U.K. sample of companies using IRRs as key measures in SIDs is very small, comprising just three SIDs. Moreover, only one of the three had an IRR higher than the U.S. average, and indeed even this figure was based on the company’s projected IRR figure. The company was also unclear as to whether it would have allowed this projected figure to fall to a lower hurdle rate, this being the figure we were seeking from them. We do not therefore deduce that U.K. companies are extensively using higher IRR hurdles than U.S. companies: the main point is that few U.K. companies use IRR rigorously on SIDs at all. For a more extensive analysis of U.K. hurdle rates, payback targets are more representative.

222 C. Carr and C. Tomkins

break into profit by the fifth year, on an annual basis, allowing for depreciation, but without any targets for return on investment (RoI), return on sales (RoS), return on capital employed (ROCE), or even ultimate payback period. In fact, this latter rule of thumb was fairly influential in U.S. multinationals too, though on the basis of a much tighter ‘3:5 rule’: get into the black by the end of year 3 and payback within 5 years.

German Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) frequently contrasted and criticized the short-term financial orientation of U.K. and U.S. competitors, but they also recog- nized the effect of Germany’s distinctive financial context, particularly that of family ownership:

The normal U.K. or U.S. companies have to report to their shareholders, on a quarterly basis, good or growing profits to prevent their share price from falling. I don’t care less. I am not on the stock market; I don’t have to report to the outside world ... Always watching the share price, U.S./U.K. companies cannot afford to hold on to an unprofitable product which has a good future for a long time; this system is a disadvantage. The view on RoI in Japan and (West) Germany on the one side, and the U.K. and U.S. on the other, is totally different. They are looking at maximisation of profits in the short-term, we look to long-term maximisation. We want to secure the future of the company in total over the years, much longer than a 5-year horizon.

Japanese executives generally concurred, though they felt that some shift had oc- curred in the last three years towards a greater emphasis on profitability than had been the case in the past, due to market maturity and the higher yen. One company President interjected following a succession of financial questions, with the following ‘personal observation’:

I have often heard of European or U.S. companies thinking over the very short-term ... what return on investment can come back within how many years; whereas Japanese managers have tended not to worry over the short-term, but think more over a much longer period of time ... So my impression from this interview is that you are one of the people who are more accustomed to rushing and recovery.

From the perspective of a President who had served his company for 30 years, connotations associated with any such process of ‘rushing’ things were viewed extremely negatively. Most CEOs in Japan, he pointed out, served a minimum of 4-6 years, so that any evaluation had to be conducted over a period at least as long, and even then most of the credit for any success was more rightfully due to the previous incumbent.

Taken together, these results confirm the popular notion of Japanese and German companies, as less short-term profits orientated, when compared with those in the U.S.A., and especially when compared with the U.K. where hurdle rates frequently displayed almost no linkage with any calculated cost of capital.

4. Strategic versus financial considerations

Porter (1 985) argues that while traditional accounting provides information on an organisation’s absolute costs and value, it does not provide such information relative to competitors. Porter further argues that it is this latter, relative, information that is

The Role of the Finance Function in Strategic Decisions 223

most relevant to strategic analysis, and he advances techniques of ‘value chain analysis’ to make good this deficiency. Dealing more particularly with investment decisions, Shank (1996) argues that traditional D C F techniques need to be comple- mented by three techniques of analysis: value chain analysis, cost driver analysis and competitive advantage analysis. Taken together these three techniques effectively integrate Porter (1 985) value chain techniques into traditional budgeting; but this analytical decomposition can also be employed usefully to examine how companies and countries vary in terms of where they place most attention in making SIDs (Carr and Tomkins, 1996).

Value chain analysis was virtually never used in either German or Japanese companies as an explicit, formalised technique; but their strategies were frequently explicitly linked into those of their car assembler ‘partners’ in a manner which addressed many of the issues raised by Porter (1985) and Shank (1996). Executives in supplier companies stressed that close relationships were sometimes strategically so important as to justify over-riding financial calculations altogether. The intention was to be ready with the very best technology appropriate to those needs, even if this meant investing ahead aggressively to the point where formalised financial analysis was consciously downplayed or even (in a number of cases) over-ridden. As one German Chief Executive put it: ‘If I have that business with X, I’m ready to do it; the calculation becomes a political document’.

In Japan, to a greater extent than even Germany, very close customer relationships dominated almost all aspects of strategic thinking; several companies had equity links with particular Japanese car assemblers, as well as sales dependency ratios so high as to render most market analysis irrelevant. What mattered almost exclusively was serving the Japanese assembler with whom they had a particular affinity, albeit increasingly internationally: there was very little scope for grand changes in terms of market positioning. Japanese SIDs were triggered almost invariably by close customer relationships and, frequently, by the need to follow affiliate car assemblers overseas. Asked why his company had acceded to Nissan’s request to come to the U.K. and to their choice of a particular U.K. partner, one Japanese replied ‘It’s difficult to say no’. An executive at another company expressed the point even more forcefully:

‘We are Japanese. Japanese people have a Japanese mind set, so even if this company does not make a profit for a hundred years, as long as they contribute to the Japanese car manufacturers in the U.K., we will hold this company’. Losses mattered, but ‘their mentality is to continue to improve’. Another SID in Continental Europe is still in fact making losses after 15 years. ‘It’s a problem, but you keep putting people in until you can improve the situation. So hopefully you can go another 10 years, then hopefully you would break even.’

T o provide additional insight into the relative emphasis on strategic versus financial considerations, we sought to score each SID in terms of the percentage weightings placed on the financial calculus compared with the emphasis on each of the other three forms of analysis advocated by Shank (specifically, the value chain, cost drivers and competitive advantage analysis). These weightings are shown in Table 4, together with a residual column for other considerations not falling into the specified cate-

224 C. Carr and C. Tomkins

Table 4 Relative attention to jinancial and strategic issues within SIDs

Companies Financial Value Cost Compet' Other Av. perf. calculus chain drivers adv. factors Score

(%) (%) (%) (%) (%) ( -5 t o + 5)

14 U.S.A. SIDs 26 U.K. SIDs 25 German SIDs 13 Japanese SIDs Average for all 78 SIDs Average for 21 good performers

Average for 15 poor performers

Ratio of good/poor (%)

( + 4 and + 5)

( - 4 and - 5)

42 9 3 46 0 2.7 46 24 6 17 7 - 1.6 15 44 7 31 3 1.9 15 53 3 29 0 2.1 30 33 5 29 3 0.9 20 36 6 35 3 4.6

48 28 4 14 6 -4.8

42 130 150 250 0.5

g ~ r i e s . ~ The percentages applied to the financial calculus may vary for each invest- ment in the extreme form from 0 % ) where the calculus has been ignored or even over-turned by other more strategic considerations, to 100% for investments driven by financial considerations to the exclusion of any more strategic assessment.

Table 4 suggests that U.K. and U.S. companies are, on average, placing approxi- mately three times as much emphasis on the financial calculus as those in Germany and Japan. This again endorses popular views as to the unique financial orientation of the Anglo-American approaches, as compared with other highly competitive coun- tries. Given the performance data in Table 1, which demonstrates the superior longer-term competitiveness of both Japan and Germany especially in this industry, and most notably their longer-term profit performances, this must raise questions as to whether such a high degree of financial orientation does not actually become counter productive at some point. We also sought to score SIDs in terms of their performance. This is extremely difficult to do reliably, given the paucity of post-audits found in this industry, and the fact that many were on-going.8 Our subsequent analysis of the relationship between SID performance and emphasis on financial

7These weighting resulted from our own subjective judgements after going through each SID case specifically to examine this issue. The main residual issue pertained to the political manipulation of analyses. Where such manipulation was particularly rife, only so much influence could be attributed to the categories examined. 'Our method here was to score SIDs either plus or minus four or five, where executives knew the outcomes, according to the level of success or failure. Thus + 5 and - 5 scores reflected either markedly successful or markedly unsuccessful projects, from their viewpoints. A score of + 4 was used by us for SIDs that had at least achieved their targets, and - 4 for those that had not but where results were considered by no means disastrous. Where outcomes were unknown, for on-going SIDs, scores in between provide some indication of a company"s overall performance ( -3 for example being used for companies in turnaround situations). These overall performance indicators provide some proxy for SID performances on the basis that overall corporate performance partly reflects the outcomes of accumulated previous investments, but these figures must necessarily be treated cautiously. Readers of Table 4 should distinguish between these middle scores and scores of 4 and 5 which were based on more reliable information directly relevant to the SIDs. In awarding higher proxy scores up to a maximum of + 3, we looked for evidence of longer-term (e.g. 5 years) financial performance, first in terms of returns on capital, secondly (where these were not provided) of profit/sales margins; but we also looked for evidence of sales growth as this reflects both competitive performance and (for a given level of profit margin) longer-term profit growth.

The Role of the Finance Function in Strategic Decisions 225

versus strategic considerations suggested that better performing SIDs placed con- siderably more emphasis on broader strategic considerations.

The second key point emerging from Table 4 is the very substantial differences in the four countries in terms of their emphasis in SIDs on value chain issues. The relative attention to such issues in each of the four countries is closely in line with literature on arms length market relationships, already carried out on a comparative basis around the world, particularly in this industry (Womack et al., 1990; Lamming, 1993; Nishiguchi, 1994). U.S. companies are taking these key strategic decisions on a highly arms length basis, even more so than the U.K., and far more so than German and especially Japanese companies. The evidence here does support Shank (1996) argument that traditional D C F analyses should be complemented by at least some modicum of value chain analysis; but one should also recognise that any implicit criticism of the U.S. emphasis on arms length rather than value chain relationships is also essentially a criticism of the entire U.S. market based system, as compared to more network based systems of subcontracting (Nishiguchi, 1994). T o take up the point that Shank (1996) made about the need to examine fundamental cost drivers when making investments, there is perhaps some support here in terms of perfor- mance data, but few companies worldwide (and certainly not the Japanese) seem to do much here on SIDs.

The third striking point from Table 4 is that for all their financial orientation, U.S. companies nevertheless put more emphasis on analysing competitive advantage than any other country. This table, in fact, underplays their relative thoroughness in this regard, at least in terms of impressive answers and supporting documentation emerging from our research (see also Lawrence, 1996). Linkage between such strategic competitive analysis and specific financial calculations was unrivalled in any other country. Our data and interviews revealed that U.S. calculations also generally included thorough sensitivity analysis. In contrast in the U.K., we sometimes found blatant cheating.’ It was fairly common for decisions to crystallise early, so that later stages of decision making processes (including capital budgeting) became rubber- stamping exercises; objectivity was not always maintained, for example, when indi- vidual sites needed investments to stave off turnaround crises. Political considera- tions were sometimes remarkably overt: one senior manager of a U.K. SID stated that:

The appraisal process for this investment was reasonable, but extremely weak in financial justification. The whole process demonstrated that logical decisions and analysis are not the only criterion for project allocation. Power politics, personal ambition and the desire to do things differently carry a heavy weighting in the decision making process.

Some lessons from the U.S. with respect to competitive and sensitivity analysis and the rigour of financial analysis may be less transferable to non-Anglo-American contexts, though we noted larger German and Japanese companies were beginning to employ similar analytical techniques; but certainly U.K. companies, whose context is more similar, seemed well behind their U.S. counterparts both in respect to the

9An executive in one U.K. supplier, for example, admitted that ‘When we phrase the Capital Appropria- tion we sometimes have to phrase it in such a way that it looks as though it is a payback within two-and-a-half years although realistically we know it will be nearer four’ (Cam et al., 1994a, p. 86).

226 C. Carr and C. Tomkins

rigour of financial calculations and in terms of methods of strategic analysis. As one U.S. Finance Vice President complained: ‘Admittedly our people don’t always have all the answers on all these (strategic) questions, that we would like them to have, but at least they feel guilty when this happens. Executives in Britain sometimes don’t even seem to feel bad about it’. The real problem perhaps for U.K. companies is that they enjoy neither the formal analytical precision, characteristic of the Americans, nor the less formal systems, the intimate customer relationships (or rather networks) and cultural approaches which, in practice, lead to deep and intimate levels of under- standing in German and Japanese SIDs (see also Gatley et al., 1996, pp. 18, 29, 39).

5. Control styles

Table 5 identifies some features of the control systems observed in the sample firms and compares those features across the countries in the sample. We also examined the control styles identified by (Goold and Campbell, 1987); specifically the Finan- cial Control, Strategic Control and Strategic Planning styles. On Goold and Cam- pell’s model, the contribution of central staff is perceived along two dimensions: first their influence on planning (for example in terms of exploiting group level synergies) and, secondly, their influence on financial controls (for example, in terms of stretch- ing budgets, or applying pressures such that these budgets are met). In ‘Strategic Planning’ style companies, central staff place most emphasis on the former; in ‘Financial Control’ style companies, their emphasis is on the latter; whilst in ‘Strategic Control’ style companies, a balance is sought between both aims.

Table 5 shows that the U.S. and U.K. companies were characterised by widespread use of the Financial Control style, contrasting with German and Japanese companies which afforded more influence to strategic considerations. It should also be noted that ownership structure differed across the sample by country with all U.S. and most U.K. firms being public companies and all but two of the Japanese also public companies. By contrast, family firms were far more prevalent in Germany. Many large German firms, often major world players in the industry, were often family firms pursuing highly entrepreneurial strategic styles, conforming closely to those noted as ‘hidden champions’ by German researchers (Simon, 1992, 1996).”

Table 5 Control features of the full sample of motor component manufacturers

U.S.A. U.K. Germany Japan

Perceived city pressure (%) 20 50 5 0

Hands off style by parent (%) 54 73 27 0 Strong financial control (%) 54 68 23 0 Turnaround situation (%) 9 64 9* 9

Division of large groups (%) 100 82 32 82

*Consistently poor RoS performance, though no actual turnaround crisis.

l o ‘Hidden champions’ were defined as companies which, whilst being European or international market leaders (or No. 1 or 2 worldwide), were nevertheless under $1 billion sales and low in terms of public visibility. Simon describes their common strategic characteristics and many German firms fell into the this category.

The Role of the Finance Function in Strategic Decisions 227

It is difficult to classify the larger Japanese companies interviewed according to the Goold and Campbell (1987) classifications which do not fit comfortably with what is known of Japanese organisations (see, for example, Ouchi, 1984). None could be described as Financial Control and none were running ‘hands off’ from some Central Office. Some were similar in style to larger German hidden champions and quite entrepreneurial (at least until recently); others would perhaps be closest to the Strategic Planning style, with one or two veering towards the Strategic Control style. Networking arrangements were strong, reinforced by equity cross-holdings, common bank and trading company linkages, very high sales dependency ratios, personnel exchanges, as well as just-in-time and synchronous supply logistical linkages, with plants sometimes no more than 10 minutes away. Quasi-vertical integration with up-stream car assemblers frequently relegated strategic planning to the level of technical and operational planning.

The contrasting Financial Control styles in the U.K. appeared to be linked to perceptions of short-termist pressures from financial institutions with Table 5 showing that some 50% of the companies perceived such pressure. Such perceptions were widespread and roused strong feelings in the U.K.; but were absent in Japan and in Germany (with the exception of one U.K. owned subsidiary). Some German CEOs stated that their SIDs would probably not have received funding support from those British financial institutions with whom they had come into contact. It may be suggested that the tough turnaround contexts, experienced by U.K. companies whose financial and competitive positions were precarious, contributed to such styles; but our longitudinal research (Cam, 1985, 1990) indicated that such styles were already well in place in both Britain and the U.S.A. albeit a little less prevalent, early in the 1980s. Nor was turnaround a feature of U.S. companies interviewed in 1995. Our findings here concur with other research (Marsh, 1990; Ball, 1991; Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte, 1991; Jacobs, 1991; Eltis et al., 1992; Hutton, 1996) that sees such short-termism and financial orientation as a phenomenon intricately associated with the Anglo-American financial context. It is though surprising that it is even more evident in the U.K. where the pressure for quarterly results and from raiders might seem rather less pronounced. Certainly some U.S. executives felt themselves exposed to pressure, though the impression given was that they had now become well accustomed to balancing financial and longer-term considerations. As one Chief Executive expressed the situation:

It’s a fact of life and I don’t know that we are all consumed on short-term, but we do have to give it its fair understanding.

We have already published a highly detailed analysis, contrasting the control styles of British and German companies as highlighted by our Anglo-German joint-venture SID case (Cam et al., 1994b). Approaches in the two countries to the same SID were examined and we were then able to follow up on control approaches. Interestingly, the U.K. conglomerate involved owed its very raison d’2tre to the belief of its (then) City-based CEO that opportunities existed for strong Financial Control style con- glomerates, prepared to raise short-term returns for potentially dissatisfied share- holders. Differences in control approaches illustrated a stark contrast, the British approach emphasizing financial issues and controls, and the German partner ada- mant that strategic issues and controls had to take precedence. After sharp clashes the

228 C. Carr and C. Tomkins

German viewpoint prevailed and the outcome was ultimately highly successful commercially, despite initial financial results that would otherwise have led to a British pull-out.

Interestingly, one Japanese company interviewed was also pursuing a joint venture with a French partner, to acquire a U.K. company, and noted similar conflicts with the French. Initially the Japanese company had been mesmerised by its partner’s impressive strategic and financial plan. Within just one year, though, the figures proved to be such nonsense that they found they were being asked to bail out the partner’s entire operation. Clashes again reflected contrasting strategic and financial control styles. ‘The most important thing for us was to have good quali ty... but when we raised investment proposals they [the French company] didn’t like it.’ Success had only come later after their insistence on taking over full management control and taking steps to counter what was regarded as inordinate creative accounting. This is precisely what happened with the Anglo-German joint venture already described. Finally, the other Japanese company we examined, joint venturing with a U.K. partner, stated that for this reason it was no longer prepared to accept any U.K. financial reports, other than on a cash flow basis.

Returning to the British/German joint venture, the British CEO’s final over-riding impression of the distinctive strength of his German partner was that of their strategic consistency:

If you go back 20 years there is nothing special about Eincore but they decided they were going to specialize in widgets. It was 2 or 3 years before they got going, but they were prepared to soldier on and get to that profitable phase. I think a British company probably would have changed its objectives.

Such long-term strategic consistency was equally a feature of Japanese companies interviewed. Their control philosophies likewise involved maintaining the strategic objective: any backtracking would in general have been almost unthinkable, particu- larly if relationships with key customers were involved. Profitability, as in Germany, was seen as the natural outcome (and not the aim) of proper management. However, whilst German companies fervently believed that financial salvation was the natural reward for well prepared and thoroughly executed plans (echoing cultural attitudes noted by Gatley et al., 1996, p.36)) in Japanese perceptions the future was inherently unpredictable. The Japanese partner in the Japanese/French venture pointed to the collapse, within the space of a single year, of their European partner’s impressive financial plans. Indeed, this company, like the U.K. joint venture company already discussed, moved to the brink of insolvency. For the Japanese company, though, profits might take 15 years to swing round, but sooner or later this was going to be achieved by painstaking processes of continuous improvement. It was this latter emphasis, and their willingness if necessary to keep sending out more and more advisors, or ultimately to change managers considered as weak to ensure full participation by the whole workforce in such improvement programmes, that distin- guished Japanese from German companies; again this accords with cultural disposi- tions noted by other researchers (Gatley et al., 1996, pp. 18, 26).

Such long-term consistency and persistency by German and Japanese companies presents a significant challenge to the short-termism that has emerged from distinc- tive Anglo-American financial contexts and cultures. The British experience (and one U.S. case proved remarkably similar) highlights the danger of a vicious cycle of

The Role of the Finance Function in Strategic Decisions 229

decline in which short-term City pressures'', extreme financial orientation, and turnaround contexts calling for yet tougher financial controls, are all going hand in hand. Overcoming this danger calls for measures not only at a macro-level, but also recommendations directed at modifying strategic management styles; in particular, some movement away from the now ubiquitous Financial Control style in Anglo- American countries would appear necessary."

6. Strategic decision making process

Of the contextual and cultural differences noted in Tables 1 and 2, a number appeared to be conducive to more thorough strategic decision processes in Germany and Japan, compared to the U.S. and the U.K. Senior German executives benefited from tenures far longer than their British counterparts (Carr, 1992) and the same was true of Japan, in comparison to both Britain and the U.S.A. Closer customer relationships, already discussed, not only provided intimate customer knowledge and information flows; but in both Japan and Germany they also constrained their strategic focus in a manner that was conducive to becoming experts in more highly specific products and technologies (Gatley et al., 1996, pp. 23-29; Simon, 1996). Contextual and cultural factors, highlighted in Tables 1 and 2, reinforce such tendencies and contribute further to an intimacy with all the market and technologi- cal details so central in strategic debates in both countries.

Consistent with these features, our data and interviews corroborated that both German and Japanese companies were disposed to greater thoroughness in decision making processes, in contrast to the more action orientated mode more typical of the British (see also Gatley et al., 1996, p. 36). In the case of Japan, we expected any such tendency to be reinforced by a consensus orientation, the Ringi system of decision taking, and TQM type involvements, and we did find SID processes taking substantially longer in Japan than in Britain and the U.S.A.

In Britain, the need for extensive risk analysis at the final approval stage was felt to be less necessary in strong Financial Control style companies. Instead of relying on thorough strategic decision making processes, these companies attempted to manage

There has been a long standing controversy over whether the U.K. stockmarket in the City provides undue pressure for high short-term financial results. Some argue that capital markets are efficient and adequately reflect longer-term benefits ensuing from major investments. Others argue that City institu- tions' staff are themselves assessed almost on a quarterly basis and that share prices do not fully reflect such longer-term benefits: if so, companies may be forced into short-term investment horizons, to maintain share prices and stave off the threat of acquisition.

Goold and Campbell (1987) original sample included five companies (all U.K.) categorised as Financial Control style. This group of companies, on average, outperformed other Strategic Planning style compa- nies (based on return on equity, for example) over the five year period of that study. Average returns on equity for these Financial Control style companies, however, fell relative to other classifications in the period following that study, being surpassed by the original Strategic Planning sample. Of the original Financial Control sample, Ferranti ran into serious financial difficulties after problems with its major U.S. acquisition and Tarmac also encountered a serious performance set-back. Like Tarmac, Hanson and BTR have been long established teaching case studies in business schools, exemplifying Financial Control styles, and their styles have been fairly consistent. Even more recently, though, both companies have slightly adapted their styles, perhaps in response to some decline in performance (compared with impressive past performances). Thus Hanson has now lengthened its payback target in response to falling U.K. interest rates, and has subsequently de-merged. BTR has now introduced formal strategic planning reviews. One large U.K. Financial Control style conglomerate which was not in Goold and Campbell's sample, but which we examined in the vehicle components sector, has subsequently entered receivership.

11

12

230 C. Carr and C. Tomkins

risk by setting very high targets, well beyond the cost of capital (which was anyway higher than in Germany or Japan), and then culling those who failed, as an example to the rest. From a corporate perspective, risk could potentially be reduced by the sheer number of bets, in terms of projects, strategic business units (SBU)s, or even entire divisions, with each subject to strong incentives to deliver.

Returns sought were based on a relatively crude judgement founded on a mixture of somewhat intangible considerations which were often difficult to unravel and often not well understood by the executives interviewed. These intangible factors included people’s track records and credibility, the scope for stretching their performance, and historical norms which were set in the mists of time and rarely reviewed. One Finance Director stated that since half of his company’s investments failed to deliver promised results, a hurdle rate of roughly twice the cost of capital ought to be about right. There was no strong theoretical grasp and application of the cost of capital in almost any of these companies, nor, where this was pointed out, was this a matter of great concern. As a result, the real impact on strategic investment choices lay much more with the less visible censorship of projects which were either too large or too long-term, and which no executive, wishing to retain his credibility, was generally likely to bring forward. Occasionally, longer-term projects did arise, particularly in the case of strong personalities whose credibility was high or in turnaround contexts where ‘there was no alternative’; but such cases appeared more the exception than the rule. Given such cultures, not to promise high returns was rarely acceptable: given such high levels of executive turnover, many also felt they had little to lose from promises which might not be met. Political manipulation of financial figures and creative accounting (Smith, 1992) were fairly rife.

Like those in Britain, U.S. companies appeared to be under considerable pressures for financial results particularly in Financial Control style companies, but there was much greater acceptance of the notion that high, arbitrary hurdle rates out of line with the cost of capital should in theory prove counter-productive. Correspondingly, any gap as compared with the cost of capital was much lower than in the U.K. and hurdle rates were correspondingly much lower, as was shown in Table 3. In the context of perhaps more realistic (if still highly demanding) financial targets, U.S. companies generally seemed much more open in their debates and we found no obvious evidence of such gross politicisation of SID processes in the U.S.A. Never- theless, the commercial director of one U.S. multinational complained bitterly about unrealistic demands from Head Office for paybacks as low as one year. U.K. management faced with such ‘irresponsible’ demands, blatantly fudged the figures, despite the obvious danger that sooner or later the real results would come through: ‘By that time, cynically, we would say to ourselves that maybe there will be a new guy in charge over there anyway. This (the SID to which the interview was referring) was an absolute disaster’. No company in any country can be immune to internal political machinations on such critical strategic decisions, and such political processes will come as no surprise to researchers in organisation (Mintzberg, 1985; Pettigrew, 1987) and capital budgeting (Berg, 1963; Bower, 1971; King, 1975; Kennedy and Sugden, 1986); but the scale of this problem in U.K. Financial Control style companies may help to explain such poor SID results and such a preponderance of turnaround contexts, as recorded in Tables 4 and 5.

Generally in the U.S.A., however, there was increasing awareness of the need to constrain gross political manipulation, or at least to tap the more positive aspects of

The Role of the Finance Function in Strategic Decisions 231

those conflicts of interest, often associated with large investment decisions (see Eisenhardt, 1990). As one Finance Executive put the situation to her subordinate on her appointment: ‘I said, now if you see me acting in a certain way that might be biased in one way or another, part of her job was to call me on it, and we developed a pretty good working relationship’.

Asked to comment on a tendency we had observed in the U.K. that sometimes there was a tendency for the finance function, when playing a policing role, to find itself a little isolated from decisions, such that these could finally end up being ‘rubber stamped’, one U.S. Finance Vice President replied: ‘Well, that’s 10 years behind the times. It has to be’. Other U.S. finance executives echoed this shift in the direction of greater teamwork and, as in Germany (see also Ahrens and Chapman, 1996)) there was a strong theme of the need for the finance function to move on from a mere ‘score maker function’ to being almost business consultants. One stated:

Our culture is one where you try to be open and get the team working, and you don’t have people fudging the figures, but ... there must be an awareness that we have got to be looking for 15% ... and there must be some tendency for that to be something of a threat’. In the past dating back to the bad old days when management accountants had been something of a policing function, there had been ‘something of a wall’ between accountants and the rest. Since then, however, more engineers and MBAs had moved into the finance function. They had needed to move up-market educatie nally ... getting good analytical ability, as opposed for going for people with formal chartered accounting training ... [Now] line managers invariably say ‘Help me figure out how to run the business well, don’t just come up with the numbers’.

Another concurred, concluding: ‘We really are in effect reducing if not eliminating, the boundaries that used to keep finance people in the back room’.

7. Conclusion and recommendation

Our study found that formalised techniques of financial analysis had less direct impact on strategic investment decisions than suggested in surveys of general capital budgeting practices (Butler et al., 1993). Our research suggested less extensive use in Britain of DCF techniques on investments generally. We would accept that part of this difference probably reflects our focus on a single, perhaps less sophisticated sector, including a mix of small as well as large firms. Some caution is therefore required in interpreting our findings in any more general context. However, the more significant differences arose when companies explained precisely which financial targets were most critical on specific strategic investments examined, and this issue is more easily accessed through field research. Even in the U.S.A., where even in our sample, all companies were using DCF on investments generally, D C F only emerged as the dominant technique in half of SIDs. Most significant is that fact that the divergence, between practices on SIDs and what might be expected from general U.S. or U.K. investment surveys, increases substantially as one moves away from the U.S .A., and particularly as one examines non-Anglo-American practices in Germany and Japan.

In terms of key investment targets, traditional payback methods remained domi- nant in all countries outside the U.S.A., with British payback periods being shorter and more rigidly applied than in Germany or Japan. Marsh (1990) advocates more

232 C. Carr and C. Tomkins

advanced D C F methods to counter any potential short-termism, given the threat of international competition. Compared with the British, U.S. companies making more extensive use of D C F do indeed generally set lower hurdle rates, more closely in line with the cost of capital. However, our study suggests that the problem is not merely one of relative sophistication of method, since German and Japanese companies pursuing long-term approaches utilize traditional payback methods to almost exactly the same extent as the British. U.S. and particularly U.K. company practices do suggest a genuine problem of short-termism, but this is manifest in implicitly higher hurdle rates (regardless of the financial technique used). This leaves them more exposed to the risk of myopic strategies undermining competitiveness against rivals from Germany and Japan, who operate within distinctive contexts and cultures permitting cheaper, more accessible capital and in return for less immediate pay-off in terms of dividends or stock price increases. The most damaging effect of short- termism is often indirect, such as through more proactive SIDs being withheld, delayed or otherwise curtailed. Barwise et al. (1989) note the importance of quantify- ing down-side scenarios associated with deferred investment decisions, but even sophisticated Anglo-American companies in practice felt unable to do so, as this would have compromised their systems of control and accountability.

Decisions generally hinged (especially in Germany and Japan) on strategic as opposed to financial arguments, yet formalised techniques of strategic analysis had surprisingly little direct impact on SIDs (as perhaps suggested by Mintzberg, 1994)) with the exception of the U.S.A. German and Japanese advantages appeared to reflect, on the one hand, the almost intuitive visions of CEOs possessing intimate understanding of both markets and technology; their willingness to pre-empt the needs of customers (particularly in their need for global coverage) with whom they enjoyed close relationships; and, on the other hand, the thoroughness of less for- malised strategic debates, which, by reason of context and organizational structure, British companies found much harder to achieve. Formal strategic analysis was of far higher quality in the U.S.A. than in the U.K. but the ‘generalist’ disposition of such staff orientated activity was nowhere near sufficient to match Germany or Japan thoroughness in terms of attention to operational and technological details.

The evidence here provides powerful support for those who point to the impact of national context and culture in establishing strategic management styles and financial approaches. In the absence of such understanding of context and culture, U.S. styles cannot be assumed to translate appropriately to contexts as different as Germany and Japan. German and Japanese companies may have been doing a little less well on SIDs than those in the U.S.A., on the indications of Table 4, but they were doing far better than U.K. companies, pursuing (admittedly somewhat crude) variations on the U.S. model. Nor indeed should we presume to develop management theory merely on the basis of U.K. or even U.S. experiences.

T o the extent that lessons can be drawn, from this more international database, Table 4 suggests better results might ensue if U.S. and U.K. companies shifted their emphases, a little more in line with those in Germany and Japan. In particular, U.S. and U.K. companies may be underplaying the importance of close customer relation- ships in this industry. It is one thing being financial conservative on minor, discretie nary investments; but this is more dangerous on SIDs, when customers later prove to have the power to insist that investments, withheld, be restored to ensure a fully internationally competitive service. U.K. companies need to do more on analysing

The Role of the Finance Function in Strategic Decisions 233

competitive advantage, if they are to match any of these international rivals. German and Japanese companies, on the other hand, need to improve their financial analysis, increasing their emphasis on this slightly, but without totally abandoning their distinctive strategic orientations.

Wiser companies will also want to interpret our results from a longer-term, international perspective. Over the last 20 years, it is almost certainly the Japanese, followed by the Germans who have made most competitive progress, and particularly in this industry, but the U.S.A. has always enjoyed a leading position and cannot be written off. Successful models of management come and go. In more recent years, Japanese progress has slowed, Germany has shown signs of complacency, whilst in Britain suppliers have undoubtedly improved at an operational 1 e ~ e l . I ~ Companies will want to examine carefully the practices on SIDs of the best international participants, basing judgements on a balanced assessment of longer-term perfor- mances not just the last year or two. They will then want to interpret how far these other models, suggest lessons that can be applied in their own context and given their own cultures.

Where, as in Britain, financial objectives are so important; where top level execu- tive turnover is so high; and where the effects of short tenure are further accentuated by strongly individualistic styles of decision-making; then it is concluded that the finance function will itself need to play a more active “guardian role” to ensure the quality of strategic decision-making processes. Failing this, there can be little assur- ance that financial figures, so influential in an Anglo-American context, are at all soundly based; nor, indeed, that they are not actually counter-productive. Whilst the presence of formal strategic planning departments (even when justifiable on costs) emerges as no guarantee of the necessary integration of both strategic and financial analysis, there seems no reason why those in top financial positions should not be expected to take on both mantles, just as is already beginning to happen in the U.S.A. A more effective devil’s advocate role is required on SIDs, but greater cohesion is generally less likely to be achieved by splitting such a role between two separate functions (strategic planning and finance), than by providing for finance directors properly trained in the use of strategic analytical techniques, as well as possessing those softer people and organizations skills without which they are unlikely to be effective.

Fewer German companies operated strong financial control styles, but the influ- ence of financial objectives has now sharply increased, as has become evident particularly in German subsidiaries of multinational companies in the industry (Burt, 1996a,b). Our interviews revealed that most German companies in the sample seemed likely to move directly to this more advanced stage. Their finance directors appeared to be very broadly educated and experienced, and also appropriately disposed (see also Ahrens and Chapman, 1996). Many, like many of those inter- viewed in the U.S.A., were now effectively integrating the twin roles of finance and strategic planning. The notion of some separated finance ‘profession’ has always been even less palatable in Japan, but larger Japanese public companies are moving closer

There appears to have been excessive optimism in some Japanese businesses and a lack of discipline in some Japanese financial institutions which has led to the recent correction, but our analysis relates solely to major strategic decisions taken in the motor vehicle parts industry where the Japanese are still extremely strong internationally. We reiterate the need for caution in generalizing from our results, until further research can establish the position in other sectors.

13

234 C. Carr and C. Tomkins

to U.S. style strategic planning (even supported by MBAs) with D C F type analysis likely to follow at some point, in the harsher financial context following on from ‘the bubble bursting’ and the high yen (though more recently this has fallen back substantially). If so, they too may move more directly to a more integrated strategic/financial approach, aided by lower levels of demarcation in staff functions and consensus systems of decision making.

A conclusion of our research for this paper and that from our previous longitudinal studies in this area is that Anglo-American companies (particularly Financial Control style conglomerates) will need to adapt to the challenges of international competition in a manner which fully recognizes their distinctive financial demands. Our research has allowed the construction of Table 6, which, in concluding the paper, synthesizes themes arising from evidence presented here and attempts to plot the way forward for more progressive companies seeking to achieve more effective integration between finance and strategy.