Clinical Supervision for mental health professionals: …...tend to be under-reported in the...

Transcript of Clinical Supervision for mental health professionals: …...tend to be under-reported in the...

CLINICAL SUPERVISION FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS: THE EVIDENCE BASE

77

Social Work & Social Sciences Review 14(3) pp.77-94 DOI: 10.1921/095352211X623227

Clinical Supervision for mental health professionals: The evidence base

Edward White1 and Julie Winstanley2

Abstract: This article acknowledges an enduring debate about the nature of evidence and provides a context for the selective review of a literature on the outcomes of Clinical Supervision, a structured arrangement to support staff, which has been widely introduced into health service systems across the world. The literature revealed that many of the claims for the positive effects of CS have remained unsubstantiated. A contemporary pragmatic randomised controlled trial, summarised here, tested the relationships between Clinical Supervision, quality of care and patient outcomes, in mental health settings in Queensland, Australia. It confi rmed that benefi cial and sustainable CS outcomes accrued for Supervisors and Supervisees, as measured by a suite of research methods and instruments including The Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale©, and for patients in one private sector mental health facility. However, the effect Clinical Supervision had on nominated outcomes still remained diffi cult to demonstrate across a broad front. Plausible explanations are offered for this and a new framework for future outcomes-related research studies is suggested, in the continuing attempt to strengthen an empirical evidence base for Clinical Supervision.

Keywords: clinical supervision; evidence base; RCT; Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale; MCSS-26

1. Director, Osman Consulting Pty Ltd, Sydney and Conjoint Professor, School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales, Australia2. Director, Osman Consulting Pty Ltd, Sydney and Principal Research Fellow, Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney

Address for correspondence: Osman Consulting Ltd, 2/35 Bay Road, Waverton, Sydney, New South Wales 2060, [email protected]

Date of publication: 28th December 2011

Acknowledgments: The pragmatic randomised controlled trial summarised in this article was supported by a competitive research grant (A$248,000) awarded by the Golden Casket Foundation/Queensland Treasury and the authors acknowledge the assistance provided throughout by the staff of the Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation, Queensland Treasury, Brisbane, Australia.

The authors also readily acknowledge with thanks the contributions of Natalie Stuart (Project Research Offi cer), Sue O’Sullivan (CS educator), Christine Palmer, Jo Munday and Kerrie Counihan (Area Coordinators). The commitment to this RCT by the twenty-four neophyte Clinical Supervisors

EDWARD WHITE AND JULIE WINSTANLEY

78

was as enthusiastic as it was steadfast. Grateful thanks are also due to the participating Supervisees; so, too, to every physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, clinical mental health nurse and senior nursing manager, for their candid contributions. As important as these respective contributions were to this study, the responsibility for any errors and omissions and all matters of interpretation reported here, rest solely with the authors.

Finally, the overarching motivation to conduct this study was to make an incremental contribution to better understanding ways in which mental health service consumers could be assisted to recover. To each and every one of them and their carers, the authors acknowledge with gratitude their willingness to share the same ambition and their active participation in a novel attempt to do so.

Introduction

Historically, reaching consensus on the constitution of evidence in health care has been elusive, subject to change and frequently accompanied by controversy (Rycroft-Malone et al 2004). For more than thirty years, the various methods by which any such evidence was produced and interpreted have refl ected the different positions adopted by individual researchers in relation to their convictions about the nature of knowledge and being; the so-called paradigm wars (Oakley 1999). For example, Marsh (1982) believed that positivism -scientifi c method- had become ‘little more than a term of abuse...like sin; everyone was against it’. Later, Clarke (1999) famously complained that quantitative methods ‘were being proselytised as a superior approach to research’ and that ‘a sub-textual propaganda was afoot’. From his initial concern with methodology, he became fascinated by the ‘furtive deployment of language against qualitative studies, which were failing in their refusal to genufl ect before the high altar of statistics’. White (2003a) observed that Clarke’s sharp defence of qualitative methodology, did so at the cost of ‘demonizing quantitative method’ and that, in his opinion, there were only two sorts of social research. These were not ‘quantitative’ and ‘qualitative’; nor ‘hard’ and ‘soft’, nor ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’, which were often their unfortunate value-laden descriptors. Rather, White asserted that there was only ‘good research’ and ‘bad research’, although, in a circular fashion, the conventions by which these relative judgments are made, tended to refl ect the starting positions of individual researchers.

Clinical supervision

Similarly, defi nitions of Clinical Supervision (CS) have not been without contest (White et al 1994) and many have been reported unsatisfactory when put to close scrutiny (Milne 2007). The following example, however, has been found to have

CLINICAL SUPERVISION FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS: THE EVIDENCE BASE

79

a practical utility: the provision of time-out and an opportunity within the context of an ongoing professional relationship with an experienced practitioner to engage in guided refl ection on current practice, in ways designed to develop and enhance the practice in the future (Open University 1998). Furthermore, several different models of CS delivery have also been reported (Winstanley and White 2003), often drawn from a range of human service disciplines with long established CS histories (see for example, Kadushin 1976, in relation to Social Work). Not uncommonly, in practical terms, CS has come to mean small groups of Supervisees (n=~6) or dyads (1:1) attending a pre-arranged meeting with an appropriately trained Clinical Supervisor, for 45-60 minutes per session, at a monthly frequency, for facilitated refl ective discussion, in confi dence, around matters of professional relevance and importance.

Over the past two decades, CS has become incorporated into the clinical governance agenda of health care service provision and is now increasingly found as a feature of international professional practice. Indeed, it has come to be widely regarded as a tour de force for clinical practice development and has also underpinned the growing level of interest by researchers to establish the evidence base for causal relationships with quality of care and patient outcomes (White et al 1998). Many of the claims to the benefi ts of Clinical Supervision remain unsubstantiated and robust research studies remain diffi cult to design, conduct, interpret and to fund. Setting aside the width of opinion about CS defi nitions, the multitude of operational models, the differing capabilities of search engines and the likelihood of multiple duplications, the most cursory on-line search for ‘Clinical Supervision’ will yield about 480,000 hits (http://www.google.com.au/search?source=ig&hl=en&rlz=&q=Clinical+Supervision&aq=f&aqi=g10&aql=&oq). Indeed, NHS Evidence at the Health Information Resources (formerly, the National Library for Health), lists some 7362 references to Clinical Supervision; over half of them (53%; n=3888) published within the last 3 years (http://www.evidence.nhs.uk/search.aspx?t=Clinical%20supervision: Accessed 21 April 2011). Some of all these references will contain data, often the product of localised studies that involve small (even tiny) samples. Many will review the attempts of other investigators to produce primary evidential data and identify their methodological shortcomings, often fairly, and then lament the incohate nature of the evidence upon which Clinical Supervision continues to be based.

A systematic review is a high-level overview of primary research on a particular research question that tries to identify, select, synthesize and appraise all high quality research evidence relevant to that question in order to answer it (Cochrane 1972). Mindful of fi ndings from research studies that are not statistically signifi cant (negative) tend to be under-reported in the literature (Hopewell et al 2009), and fi ndings regarded as exciting or statistically signifi cant (positive) tend to be over-reported (Von Elm et al 2004), scholarly reviews of any literature make a contribution in two ways. First, they attempt to anchor the current state of knowledge to a point in time and, to some extent at least, try to obviate the need for other researchers ‘to rake over the coals’ (unless this be the historical purpose of their enquiry, of course). Second,

EDWARD WHITE AND JULIE WINSTANLEY

80

they signpost discriminating readers to telling accounts of the methodological and substantive challenges for future empirical studies. Although the Cochrane Library does not presently list a systematic review of Clinical Supervision (http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/view/0/index.html), the work of Freitas (2002) and Wheeler and Richards (2007) is justifi ably recognised in both these respects.

Freitas (2002) critically reviewed ten CS studies published between 1981 and 1997, each of which sought to link a set of causal relationships between Clinical Supervision and patient outcomes; no relevant studies were found between 1997 and 2001. Inter alia, he acknowledged the monumental contributions of Ellis and Ladany (1997) and Ellis et al (1996) who critically reviewed over 100 studies located in the supervision literature. Freitas (2002) concluded there was reason to be hopeful about the current trend in supervision research, because it was burgeoning (witness the NHS Evidence, above), that methodological fl aws could be easily remedied and that published research may underestimate a good deal of the potential results available by not controlling for Type II error (a so-called false negative; viz, the error of failing to observe a difference when, in truth, there is one). From 8295 references revealed by the keyword search, the later work of Wheeler and Richards (2007) reviewed just 18 CS studies published in English since 1980, which satisfi ed set inclusion criteria. For this review, Supervisees were counsellors or psychotherapists or other professionals who have had a substantial training as counsellors or psychotherapists and who were specifi cally engaged in a counselling role with clients; ‘hence psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists and other health professionals having supervision were excluded’ (Wheeler and Richards 2007). However, here too, the quality of evidence was again found variable, but supervision was consistently demonstrated to have some positive impacts on the Supervisee.

Clinical Supervision ‘sits at the crossroads between professional development and professional practice and cries out for study and enhancement’ (Milne, 2009). However, as yet another review of the international CS literature (Butterworth et al, 2008) also observed, the ‘tired’ discussions in the literature ‘offered no new insights’, although the authors were ‘encouraged that new ideas related to patient outcome and professional development are emerging’. The effi cacy of doing so has rarely been examined; however, Spence et al (2001) made a noteworthy contribution to better understanding the CS literature in relation to mental health professionals (clinical psychology, occupational therapy, speech therapy and social work). She concluded that, as have so many others before and since, that although supervision was generally reported by staff to have been valuable in enhancing skills and competence, there was a lack of empirical evidence to demonstrate that supervision actually produced long-term improvements in clinical practice and better client outcomes (the acid test of good supervision; Ellis and Ladany, 1997). Other recent creditable attempts have been made in discrete mental health settings (see, in particular, Bambling et al, 2006; Bradshaw et al, 2007) to help establish such an empirical evidence base but, for many of these claims, it has remained elusive.

CLINICAL SUPERVISION FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS: THE EVIDENCE BASE

81

Mental health

Mental health service provision in many developed countries is reportedly sub-optimal. In the United States of America, for example, ‘most people with mental disorders remain either untreated or poorly treated’ (Wang et al, 2005). In the United Kingdom ‘acute mental health inpatient units are often, in effect, places of safety, masquerading as a therapeutic response’ (Lawton-Smith, 2008). Similarly, in Australia, the treatment of mental illness has been ‘vastly inadequate, inappropriate, or simply not available’ (Roxon, 2008) and added to stress on staff working in such conditions. This was particularly so for mental health nurses (MHN; White, 2003b). Internationally, Edwards and Burnard (2003) reported low overall job satisfaction, dissatisfaction with perceived quality of decision making by managers, and burnout, as the main reasons for mental health nurses leaving the workforce. Moreover, high levels of emotional exhaustion were known to be associated with direct patient care, the work environment and lack of support (Leiter and Harvie, 1996). A fi t can be found, therefore, between the issues reported by MHNs and the remedial claims made for Clinical Supervision in many of these respects.

The Clinical Supervision Evaluation Project (CSEP; Butterworth et al, 1997) not only provided a unique perspective on stress, coping, burnout and job satisfaction of nurses (Butterworth et al, 1999), it also established the essential contours of Clinical Supervision in Britain. The CSEP was not designed to examine the transfer effect (if any) to the quality of service provision and to patient outcomes. However, the fi ndings from this study informed the relative usefulness of existing assessment tools used to measure the impact of CS and also provided an opportunity to develop the fi rst internationally validated, CS-specifi c, copyright research instrument; The Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale© (MCSS©; Winstanley, 2000). The MCSS© has since been adopted as an outcome measure of the effectiveness of CS in ~85 Clinical Supervision evaluation studies, in 13 countries around the world and has been translated into seven languages other than English; French, Spanish, Portuguese, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish and Finnish (see Hyrkas et al, 2003). Several variant versions of the MCSS© have also been developed, including a Perception of Clinical Supervision version, for use with respondents with no prior CS experience. Other variants have been tailored for school teachers and Allied Health staffs. A large international normative database has grown over time, for benchmarking purposes and secondary analyses. For example, fi ndings from a recent Rasch Analysis of these data, using RUMM 2030 software, have re-confi rmed the established psychometric properties of the MCSS© and have justifi ed a re-modelled version, the MCSS-26©, which will become available to CS researchers under licence via www.osmanconsulting.com later in 2011 (Winstanley and White, 2011). As the name implies, The MCSS-26© contains ten fewer items than the current MCSS©, without compromise to the robust psychometric integrity of the instrument. To date, no other CS-specifi c questionnaire has yet withstood such rigorous analytic scrutiny, nor publicly reported such fi ndings, in an attempt

EDWARD WHITE AND JULIE WINSTANLEY

82

to make stepwise contributions to the methodological literature and the increase of substantive confi dence to end-users; The Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale© remains distinctive in both these respects.

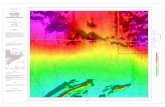

The popularity of the MCSS© arises not only from its established psychometric properties, but also because the seven subscales (recently reduced to six in the MCSS-26©) tapped into the three domains of one of the most infl uential models of group Clinical Supervision (see Figure 1 above); the so-called Proctor Model (Proctor, 1986; Proctor and Inskipp, 2003).

These are known as the Normative domain (to address the promotion of standards and clinical audit issues), the Restorative domain (to develop the personal wellbeing of the Supervisee), and the Formative domain (development of knowledge and skills). A welcome linkage has been established over time, therefore, between a clinical nursing issue (CS), an operational defi nition (Open University, 1998), a conceptual model (Proctor, 1986) and a dedicated research instrument (MCSS©).

Figure 1Description of the factor structure of the Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale© in relation to the three domains of the Proctor Model of Clinical Supervision

CLINICAL SUPERVISION FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS: THE EVIDENCE BASE

83

Clinical supervision evaluation

Set against these multiple backdrops, a novel pragmatic randomised controlled trial (RCT) was conducted by the present authors, to examine the effects of implementing Clinical Supervision into mental health settings. The RCT aimed to test relationships between Clinical Supervision, the quality of nursing care and patient outcomes. It was situated in 17 adult mental health facilities, in 9 participating locations across Queensland Health (the State-wide healthcare provider), Australia, in public and private, and in inpatient and community settings. None of these settings had pre-existing CS arrangements in place. The allocation of clinical facilities to either the Intervention Arm or the Control Arm of the RCT was random, insofar as the Research Team was blind to the characteristics of the facilities that comprised the pool that met the explicit entry criteria. Units assigned to the Intervention Arm of the study had CS implemented into the working practices of MHNs; those that were assigned to the Control Arm of the study did not implement CS. The latter participated in the RCT through the collection and submission of outcomes data only. All necessary ethical approvals were obtained in writing from 10 relevant Human Research Ethics Committees before the RCT began.

After all necessary administrative permissions had been obtained, 24 individual mental health nurses were identifi ed at local level, across the State, to be trained as a CS Supervisor. Each was required by the research protocol to hold the respect and confi dence of managers and clinicians alike, in such a role. Mindful of the need for an appropriate educational preparation (the absence of which, in psychology, was once identifi ed as a ‘signifi cant gap’ and the profession’s so-called dirty little secret: Hoffman, 1994), they attended an intensive, residential, tailor-made, 4-day, experiential CS course, led by the RCT Research Team (White and Winstanley, 2009a). The course comprised practical CS sessions with direct feedback, each of which followed a linked program of theory-based seminars. The course was well reviewed by Supervisors and was found to be demonstrably effi cacious. The Supervisees were prepared locally by the Supervisors who attended the CS training course, during which the importance of information-giving and orientation to CS was stressed.

A year-long Intervention Phase of the RCT immediately followed the end of the CS course, during which the neophyte Supervisors set-up and delivered group Clinical Supervision sessions to Supervisees in their respective Mental Health Service locations. The two furthest RCT locations were 1770kms (1100 miles) apart. Each Supervisor received their own CS from one of three RCT-funded Area Coordinators (themselves, experienced Clinical Supervisors), who visited participating facilities at least once a month over the following year.

EDWARD WHITE AND JULIE WINSTANLEY

84

Data collection

In keeping with contemporary research practice and the logic that neither quantitative nor qualitative methods, alone, are suffi cient to capture the trends and details of the situation (Creswell, Fetters and Ivankova, 2004), supplementary qualitative data collection methods were also employed to illuminate the quantitative data. Diary accounts (n=139) were provided by the neophyte Clinical Supervisors on a monthly basis, for a year after completion of their preparatory CS course (White & Winstanley, 2009a). In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of their senior nursing managers and other clinical staff (n=17) in each of the participating locations (White and Winstanley, 2010a). Quantitative data were collected at three levels; Nurse, Patient and Unit staff. From the plethora of research instruments available, a suite of copyright outcome measures was deemed fi t for purpose (see presently cited examples in Figure 2). Each was credentialed by well

Figure 2Table to show cited examples of quantitative research instruments used in the RCT

Level of data Research instrument Reference

Su

perv

isor

s an

d Su

perv

isee

s

General Health Questionnaire 28 item version (GHQ28)

Goldberg D and Williams P (1988) A Users Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-Nelson

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)

Maslach C and Jackson S (1986) The Maslach Burnout Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press

General Health (SF-8) Ware J, Kosinski M, Dewey J and Gandek B (2001) A Manual for Users of the SF-8 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Inc.; and Boston, MA: Health Assessment Laboratory

Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale© (MCSS©)

Winstanley J (2000) Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale. Nursing Standard 14:19, 31-32

Pat

ient

s

Psychiatric Care Satisfaction Questionnaire (PCSQ)

Barker D and Orrell M (1999) The Psychiatric Care Satisfaction Questionnaire: A reliability and validity study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 34, 111-116

U

nit

Perception of Unit Quality (PUQ)

Cronenwett L (1997) A multidisciplinary measure of perceptions of unit quality. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of North Carolina, USA

CLINICAL SUPERVISION FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS: THE EVIDENCE BASE

85

established psychometric properties and all necessary permissions for their use were received in writing. Data were collected between July 2007 and January 2009. The collection of specifi c resource-use information, to enable an economic evaluation, fell outside the scope of this RCT. The methodological design and statistical procedures have been fully reported elsewhere (White & Winstanley, 2009b).

Summary fi ndings from the RCT

Participants

At baseline, participants in the Intervention Arm of the RCT (n=9 sites), in which CS was implemented, comprised Mental Health Nurses (Clinical Supervisors n=24; Supervisees; n=115); Patients (n=82) and Unit staff (n=43). In the Control Arm (n=7 sites), in which CS was not implemented, they comprised Mental Health Nurses (n=71); Patients (n=88); Unit staff (n=11), shown in Table 1 overleaf.

No statistically signifi cant differences were found in the demographic data, nor for any work or health-related outcomes as measured by the SF8, between the Intervention and Control Arm nurse participants at baseline. As was anticipated for MHNs in the Control Arm of the RCT (because nothing was changed from usual), no statistically signifi cant differences were found on any of the research instruments, over the following 12 months of the trial.

Supervisors

In the Intervention Arm, quantitative fi ndings revealed that the Supervisor Total MCSS© scores at the end of the CS course were statistically signifi cantly higher compared with their perception of CS at baseline (Table 2). This signifi cant difference was maintained after 12 months supervisory experience as Supervisor (who also received personal CS throughout). Two MCSS© subscales revealed particularly signifi cant differences, over time; viz, Trust and Rapport and Importance/Value. (See Table 2overleaf.)

In general terms, fi ndings from this RCT confi rmed that high Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale© scores were systematically associated with low Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) scores (see also, for example, Edwards et al, 2006); that is, the better the CS, the less burnt out they felt. Supervisors also revealed scores which were indicative of an overall reduction in the level of General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) so-called ‘psychiatric caseness’ during the course of the study (9/24, 38% ‘ 5/22, 23%), although this was not statistically signifi cant at the 5% level.

Findings derived from the qualitative data collection methods at baseline found

EDWARD WHITE AND JULIE WINSTANLEY

86

Table 1Demographic details and baseline health related outcomes of all nurse participants

CLINICAL SUPERVISION FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS: THE EVIDENCE BASE

87

that Supervisors were most daunted by the anticipated lack of support from their managers and peers in their home locations. In the event, they were found to be challenged by their experience; many to a very considerable extent (White and Winstanley 2009a).

Senior Managers reported that they were optimistic and enthusiastic about CS, but were also disappointed and embarrassed when their junior managerial colleagues and other clinical nursing staff, did not hold a similar conviction when tested by the realities of implementation. Almost without exception, Supervisors were most challenged by the practical mechanisms necessary to schedule a staff duty roster to accommodate innovative Clinical Supervision arrangements. Managerial mindsets reportedly ranged from enthusiastic, through unsupportive, to frankly hostile and resistant. When the latter was the case, considerable tensions were created and the setter of the staffi ng roster became the sole de facto arbiter of the entire CS implementation program. Control and management of the roster was found to be the bellwether mechanism by which CS was both facilitated and stymied. It also conveyed how Clinical Supervision was conceptualised at local level as either integral to local practice arrangements, or as extra-curricular.

Table 2Medians (ranges) of MCSS© sub-scale scores obtained from Supervisors and Supervisees who provided complete MCSS© data at both time points

EDWARD WHITE AND JULIE WINSTANLEY

88

Supervisees

In two thirds of RCT Intervention Arm locations (6 of 9), Supervisees self-reported their CS experience as having met or exceeded their expectations, between baseline and twelve months. Overall, the MCSS© Total scores for Supervisees did not change systematically in a statistically signifi cant direction. However, over the 12 months of receiving Clinical Supervision, two MCSS© subscales associated with Proctor’s (1986) Normative and Restorative domains (Trust/Rapport and Personal Issues) did increase signifi cantly, over time (Table 2).

Patients

Psychiatric Care Satisfaction Questionnaires (PCSQ-R) with complete data were received from 159 of the 170 respondents at baseline (94%) and 110 were received at fi nal time point. At baseline and fi nal time points, the overall median score was 65. From samples gathered at the baseline and 12 month time points, there were insignifi cantly small shifts in either direction, but large variability. For benchmarking purposes, a median score for the total PCSQ-R of 65 (range 19–90) would be indicative of the patients being reasonably satisfi ed with the level of care and service provided from their mental health service; that is, they tended to agree with most of the positive statements in the questionnaire and tended to disagree with the negative statements.

Unit staff

In this RCT, there was also no overall statistically signifi cant difference, over time, between Perception of Unit Quality (PUQ) surveys received from Unit clinical staff in the Intervention and Control groups (z=-1.7, p=0.088). The possible PUQ total scores range from 19 to 95. For benchmarking purposes, the overall median PUQ score of 66 found in this RCT (range 30-95) was indicative of the group of clinical staff rating the quality of care as ‘fair’. On inspection, these data revealed a positive shift for the Intervention Arm and a negative shift for the Control Arm. However, statistical analysis was limited by small sample sizes and these intuitively encouraging fi ndings should be interpreted in an appropriately parsimonious manner.

Given these fi ndings and their explicit caveats, however, one RCT location was statistically signifi cant standout in an unequivocally positive direction; that is, the PUQ score increased by 11 points. This clinical facility was located in the only private sector mental health service to participate in the RCT. It was also characterized by its small size (the smallest in the study), an enthusiastic buy-in from all levels of management (probably the highest), an exceptional commitment from the single Supervisor, who provided regular CS sessions, occasionally in their own time, of a

CLINICAL SUPERVISION FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS: THE EVIDENCE BASE

89

demonstrably effi cacious standard, where Supervisees reported their expectation of CS at baseline was met by their subsequent experience of it, where 100% of the Unit nursing staff participated in the CS sessions (the highest) and where the Supervisee attrition rate was the lowest in the RCT.

Discussion

The presently reported quantitative fi ndings all support the premise that the CS training, and subsequent participation and dedicated CS support in their own workplaces, had sustainable benefi cial effects for Supervisors. For Supervisees, statistically signifi cant changes were also found in the MCSS© subscales associated with Proctor’s (1986) Restorative and Normative domains. A novel theoretical proposition emerged, therefore, that the Formative domain (concerned with the development knowledge and skills and, therefore, most relevant to an impact on patient outcomes) may only be demonstrable after signifi cant changes to the Restorative (concerned with personal wellbeing) and Normative (concerned with the promotion of standards and clinical audit issues) domains have fi rst become established, caused by sustained effi cacious Clinical Supervision. An increase in the frequency and length of CS sessions (White 1999) and a reduction in the number of Supervisees per CS group (Proctor 2010) are also worthy considerations to be tested in future research designs.

This RCT also found that signifi cantly more Supervisees who scored less than MCSS© median value of 136 (the hypothesised threshold at which CS effi cacy may be achieved) moved into GHQ© ‘psychiatric caseness’, over time. There was no signifi cant change in the level of ‘caseness’ for those that scored more than 136. This suggested a second proposition; that only demonstrably effi cacious CS may make a contribution to the maintenance/improvement of Supervisee’s well-being (Proctor’s Restorative domain); axiomatically, superfi cial supervision will not.

Many of the senior offi cers who managed the mental health nursing services in this RCT declared a preference for their clinical settings to be allocated to the Intervention Arm, rather than the Control Arm. Indeed, such was their optimism about CS as a tour de force for change in the organizational culture, which was often described by in deprecating terms, that some were not willing to participate unless this was so. In addition to these declarations of preference, the attrition of data-providing respondents subsequently varied by location and, in some settings, was noteworthy. These features challenged the methodological requirements of this RCT, not only to ensure a balance between Intervention and Control Arm numbers, but also to limit the scope of appropriate analyses that could be performed on the data received. These real-life features of a pragmatic trial are acknowledged here and in the methodological literature (see Oxman et al, 2009; White, 2011).

EDWARD WHITE AND JULIE WINSTANLEY

90

The individual performance of Clinical Supervisors, as reported by Supervisees in this study, and vice versa, was mediated by the organizational culture in which they were expected to be at the vanguard of a nursing practice innovation (see Greenhalgh et al, 2004). Good Supervisors were as unlikely to achieve a desired CS effect in unhealthy cultures, as were poor Supervisors in healthy cultures. From a descriptive point of view, across Intervention and Control Arm settings over time, only small changes were seen in either direction. Thus, an overall positive systematic relationship between CS, quality of nursing care and patient outcomes could not be statistically established in this RCT. However, absence of evidence, is not evidence of absence (see the earlier related reference to Type II Error). Randomised controlled clinical trials that do not show a signifi cant difference are often called ‘negative’. This term wrongly implied that a study had shown that there was no difference, whereas

usually all that had been shown was an absence of evidence of a difference (Altman and Bland, 1995). Indeed, in one location, a private sector mental health service provider, all outcome measures were found to move in a signifi cantly positive direction and in an intuitively convincing manner. Both the Psychiatric Care Satisfaction Questionnaire and the Perception of Unit Quality instruments, revealed statistically signifi cant improvements over the period of 12 months.

Implications for practice development and future evaluations

A number of factors were identifi ed in this positive location which, given appropriate parsimony and mindful of the relevant literature (see Fixsen et al, 2005), appear to be pertinent and indicate the best generic contemporary advice available for practice development and/or a framework for focussed evaluation strategies in the future (White and Winstanley, 2010b), suffi cient to be tested in other environments. The culture of such an evaluation environment should be characterised by a prevailing measure-theorise-modify-retest approach to practice development. First, select a single, discrete clinical location and agree an explicit, unifi ed, positive position on CS that can be owned by all levels of Management. Then, carefully identify Clinical Supervisor candidates and educationally prepare them to the standard demonstrated in this RCT. Recruit all staff in the clinical setting to participate in CS, according to standard protocols for size, frequency, length, ground rules and so on. If the model of CS involves groups, ensure that fewer than nine Supervisees are allocated to one Supervisor per session and retain as many of the Supervisees as possible (>90%) over the period of data collection (not less than one year). Deliver sustained, effi cacious CS (indicated by a median Supervisee Total MCSS© score of >136) and support Supervisors with their own regular CS sessions.

CLINICAL SUPERVISION FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS: THE EVIDENCE BASE

91

Conclusions

Located within an emergent literature on the outcomes of Clinical Supervision, novel fi ndings reported here have made incremental headway toward helping to establish an empirical evidence base for some of the claims made about CS. Indeed, the latest scholarly review of the international CS literature (Watkins, 2011) identifi ed this pragmatic RCT as ‘one of three studies conducted over the last 30 years, that provide the best and clearest directions for further thought about conducting future successful research in the supervision-patient outcome area’. It confi rmed the importance of the prevailing health service management culture in the outcome of implementation attempts and identifi ed factors that appeared to have the capacity to both advantage and thwart positive outcomes for staff and patients. It revealed evidence that Supervisees valued, and gained benefi t from, demonstrably effi cacious Clinical Supervision. The effect this may have on the quality of care and patient outcomes was able to be demonstrated in a controlled setting within this RCT, but remained elusive to demonstrate across a broad front. Plausible explanations have been have been articulated and a framework for future research has been suggested. Thus, whilst these original substantive insights and theoretical propositions were derived from mental health nursing, in a single geographic location, they may resonate internationally for other mental health professions and offer the opportunity to apply and evaluate these in future attempts to strengthen the evidence base for Clinical Supervision.

References

Altman D and Bland M (1995) Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. British Medical Journal, 311, 485 (19 August)

Bambling M, King R, Raue P, Schweitzer R and Lambert W (2006) Clinical supervision: Its infl uence on client-rated working alliance and client symptom reduction in the brief treatment of major depression. Psychotherapy Research, 16, 317-331

Bradshaw T, Butterworth A and Mairs H (2007) Does structured clinical supervision during psychosocial intervention education enhance outcome for mental health nurses and the service users they work with? Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14, 4-12

Butterworth T Carson J, Jeacock J, White E and Clements A (1999) Stress, coping, burnout and job satisfaction in British nurses: Findings from the Clinical Supervision Evaluation Project. Stress Medicine, 15, 27-33

Butterworth T, Bell L, Jackson C, and Majda P (2008) Wicked spell or magic bullet? A review of the clinical supervision literature 2001-2007. Nurse Education Today, 28, 3, 264-272

Butterworth T, Carson J, White E*, Jeacock J**, Clements A and Bishop V (1997) Clinical Supervision and Mentorship. It is good to talk: An evaluation study in England and Scotland. Final Report. Manchester: University of Manchester

EDWARD WHITE AND JULIE WINSTANLEY

92

Clarke L (1999) Nursing in search of a science: The rise and rise of the new nurse brutalism. Mental Health Care, 2, pp270-273.

Cochrane A (1972) Effectiveness and Effi ciency: andom refl ections on Health Services. London: Nuffi eld Provincial Hospitals Trust. Reprinted in 1989, in association with the British Medical Journal. Reprinted in 1999 for Nuffi eld Trust by the Royal Society of Medicine Press, London

Creswell J, Fetters M and Ivankova N (2004) Designing a mixed methods study in Primary Care. Annals of Family Medicine, 2(1), 7-12

Edwards D and Burnard P (2003) A systematic review of stress and stress management interventions for mental health nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 42, 169-200

Edwards D, Burnard P, Hannigan B, Cooper L, Adams J, Juggessur T and Fothergill A (2006) Clinical Supervision and burnout: The infl uence of Clinical Supervision for community mental health nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15, 8, 1007-1015

Ellis M and Ladany (1997) Inferences concerning supervisees and clients in clinical supervision: An integrative review. In: Watkins C (Ed.) Handbook of Psychotherapy Supervision (pp447-507). Wiley, New York

Ellis M, Ladany N, Krenggel M and Schult D (1996) Clinical Supervision research from 1981 to 1993: A methodological critique. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 28, 47-52

Fixsen D, Naoom S, Blase K, Friedman R and Wallace F (2005) Implementation Research: A synthesis of the literature. The National Implementation Research Network (FMHI Publication #231). Tampa, Fl: Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, University of South Florida.

Freitas G (2002) The impact of psychotherapy supervision on client outcome: A critical examination of 2 decades of research. Psychotherapy; Theory/Research/Practice/Training, 39, 4, 354-367

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P and Kyriakidou O (2004) Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly, 82, 4, 581-629

Hoffman L (1994) The training of psychotherapy Supervisors: A barren scape. Psychotherapy in Private Practice, 13, 1, 23-42

Hopewell S, Loudon K, Clarke M, Oxman A, Dickersin K (2009) Publication bias in clinical trials due to statistical signifi cance or direction of trial results. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 1. Art. No: MR000006

Hyrkas K, Appleqvist-Schmidlechner and Paunonen-Ilmonen (2003) Translating and validating the Finnish version of the Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 17, 358-364

Kadushin A (1976) Supervision in Social Work. New York: Columbia University PressLawton-Smith S (2008) Response to the publication of the Healthcare Commission’s review of NHS

acute inpatient mental health services, ‘The Pathway to Recovery’. News release 23 July 2008. Mental Health Foundation, London

Leiter M and Harvie P (1996) Burnout among mental health workers: A review and a research agenda. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 42, 2, 90-101

CLINICAL SUPERVISION FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS: THE EVIDENCE BASE

93

Marsh C (1982) The survey method: The contribution of surveys to sociological explanation. London: George Unwin and Allen

Milne D (2007) An empirical defi nition of clinical supervision. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46, 437-447

Milne D (2009) Evidence-based Clinical Supervision: Principles and practice. Chichester: BPS/ Blackwell

Oakley A (1999) Paradigm wars: Some thoughts on a personal and public trajectory. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 2, 3, 247-254

Open University (1998) K509: Clinical Supervision: A development pack for nurses. Milton Keynes : Open University Press,

Oxman A, Lombard C, Treweek S, Gagnier J, Maclure M and Zwarenstein M (2009) Why we will remain pragmatists: Four problems with the impractical mechanistic framework and a better solution. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 485-488

Proctor B (1986) Supervision: A cooperative exercise in accountability. In: Enabling and Ensuring: Supervision in Practice (Eds: Marken M and Payne M) pp21-34. Leicester : National Youth Bureau and Council for Education and Training in Youth and Community Work,

Proctor B (2010) Review. Journal of Research in Nursing, 15, 2, 169-172Proctor B and Inskipp F (2003) Group Supervision. In: Scaife J et al [Eds.] Supervision in

Clinical Practice: A practitioners guide. 2nd Edition. London: RoutledgeRoxon N (2008) The Grace Groom Memorial Lecture (delivered by the Australian Federal

Minister for Health and Ageing). 12 June. National Press Club, Canberra, AustraliaRycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Titchen A, Harvey G, Kitson A and McCormack B (2004) What

counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 47, 1, 81-90Spence S, Wilson J, Kavanagh D, Strong J and Worrall L (2001) Clinical Supervision in four

mental health professions: A review of the evidence. Behaviour Change, 18, 3, 135-155Von Elm E, Poglia G, Walder B, Tramèr M (2004) Different patterns of duplicate publication.

An analysis of articles used in systematic reviews. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291, 974-980

Wang P, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus H, Wells K and Kessler R (2005) Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Co-morbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 629-640

Watkins C E (2011) Does psychotherapy supervision contribute to patient outcomes? Considering 30 years of research. The Clinical Supervisor, 30, 2, 1-22

Wheeler S and Richards K (2007) The impact of clinical supervision on counsellors and therapists, their practice and their clients: A systematic review of the literature. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 7, 1, 54-65

White E (1999) Personal communication. In: Winstanley J (2000) Clinical Supervision: Development of an evaluation instrument. Unpublished PhD thesis, p232. Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Nursing, University of Manchester

White E (2003a) The struggle for methodological orthodoxy in nursing research: The case of mental health. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 12, 88-95

EDWARD WHITE AND JULIE WINSTANLEY

94

White E (2003b) Patient safety and staff support; the sine qua non of high quality mental health service provision. In: Treatment Protocol Project (2003). Acute Inpatient Psychiatric Care: A Source Book. World Health Organisation Collaborating Centre for Evidence in Mental Health Policy. Chapter 13. Darlinghurst, New South Wales 2010, Australia

White E (2011) Challenges which may arise when conducting real-life nursing research: An insight into practical issues. Nurse Researcher: The International Journal of Research Methodology in Nursing and Health Care. RCN Publishing Company, London (Accepted for publication; forthcoming)

White E and Winstanley J (2009a) Implementation of Clinical Supervision: Educational preparation and subsequent diary accounts of the practicalities involved, from an Australian perspective. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16, 10, 895-903

White E and Winstanley J (2009b) Clinical Supervision for nurses working in mental health settings in Queensland, Australia: A randomised controlled trial in progress and emerging challenges. Journal of Research in Nursing, 14, 3, 263-276

White E and Winstanley J (2010a) Clinical Supervision: Outsider reports of a research-driven implementation program in Queensland, Australia. Journal of Nursing Management, 18, 689-696

White E and Winstanley J (2010b) A randomised controlled trial of Clinical Supervision: Selected fi ndings from a novel Australian attempt to establish the evidence base for causal relationships with quality of care and patient outcomes, as an informed contribution to mental health nursing practice development. Journal of Research in Nursing, 15, 2, 151-167

White E, Butterworth T, Bishop, V. Carson J, Jeacock J and Clements A (1998) Clinical Supervision: Insider reports of a private world. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28, 1, 185-192

White E, Riley E, Davies S and Twinn S (1994) A detailed study of the relationships between support, supervision and role modelling for students in clinical areas, within the context of Project 2000 courses. English National Board for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting, London.

Winstanley J (2000) Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale©. Nursing Standard, 14, 19, 31-32Winstanley J and White E (2003) Clinical supervision: Models, measures and best practice.

Nurse Researcher: The International Journal of Research Methodology in Nursing and Health Care, 10, 4, 7-38

Winstanley J and White E (2011) The MCSS-26©: Revision of The Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale© using the Rasch Measurement Model. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 19, 3, 160-178

* Present author** Now Winstanley; present author