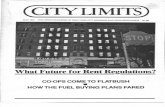

City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

-

Upload

city-limits-new-york -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

0

Transcript of City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

1/28

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

2/28

e i t v L i m i t s

Volume XVII Number 5

City Limits is published ten times pe r year,monthly except bi-monthly issues in June/July an d August/September, by th e City LimitsCommunity Information Service , Inc ., a nonprofit organization devoted to disseminatinginformation concerning neighborhoodrevitalization.

SponsorsAssociation for Neighborhood an dHousing Development, Inc.

New York Urban CoalitionPratt Institut e Center for Community an d

Environmental DevelopmentUrban Homesteading Assistance Board

Board of DirectorsEddie Bautista , NYLPIICharter Rights

ProjectBeverly Cheuvront, NYC Department of

EmploymentMary Martinez, Montefiore HospitalRebecca Reich , Turf CompaniesAndrew Reicher , UHABTom Robbins, JournalistJay Small, ANHDWalter Stafford , New York UniversityDoug Turetsky , Community Service SocietyPete Williams , Center for Law an d

Social JusticeAffiliatians for identification only.

Subscription rates are: for individuals andcommunity groups, $20/0ne Year , $30/TwoYears; for businesses , foundations, banks,government agencies an d libraries, $35/0neYear $50/Two Years. Low income , unemployed, $10/0ne Year .

City Limits welcomes comments an d articlecontributions. Please include a stamped, selfaddressed envelope for return manuscripts.Material in City Limits does not necessarilyreflect th e opinion ofthe sponsoring organizations. Send correspondence to: CITY LIMITS,40 Prince St., New York, NY 10012.

Second class postage paidNew York, NY 10001

City Limits (ISSN 0199-0330)(212) 925-9820

FAX (212) 966-3407

Editor: Lisa Glazer

Senior Editor: Andrew White

Contributing Editors: Mary Keefe , Errol Louis,Peter Marcuse , Margaret Mittelbach

Production: Chip Cliffe

Photographers: Isa Brito, Rkky Flores,Andrew Lichtenstein, F.M. Kearney

Advertising Representative: Jane Latour

Copyright 1992. All Rights Reserved . Noportion or portions of this journal may bereprinted without th e express permission ofth e publishers.

City Limits is indexed in th e Alternative PressIndex an d th e Avery Index to ArchitecturalPeriodicals and is available on microfilm fromUniversity Microfilms International ,Ann Arbor ,M148106.

2 / M A Y 1 9 9 2 / CITY U MITS

"-III'I;'t"

Unholy Alliances

Moving beyond fractious ideological disputes and competingagendas, a broad-based coalition of housing advocates joinedforces in the budget battle last month-and it looks like they'vewo n an important early victory,

As we go to press, the newest version of the mayor's proposed budgethasn't been released, bu t Dinkins administration officials are promisingto restore about half of the proposed $513 million cu t in capital spendingon housing that was announced this winter_

That's a significant step in th e right direction_ I f he City Hall scissorhands slashed away as they originally planned, it would have brought anen d to th e city's ambitious attempt to rebuild New York's poorestneighborhoods. Out the window_ Kaput.

Neighborhood housing groups that have 'spent years developing asophisticated system for rebuild ing housing would have ha d to fire staffan d sit tight, hoping against hope for ne w federal housing money to kickin. And wh o knows when that would have happened?

Behind the united front of the coalition against the budget cuts are

groups that usually compete with each other for precious governmentsubsidies: advocates for th e homeless, city-wide nonprofit developers,community based housing groups, and the New York City Partnership ,which develops middle-income housing in poor neighborhoods.

Much to some people's chagrin, Kathryn Wylde, th e director of theNew York City Partnersh ip, has taken on a leadership role in the coalitionagainst the budget cuts. She's been working side-by-side with advocateswh o have spent years fighting Partnership housing because it doesn'thelp the neediest New Yorkers. It's a credit to everyone involved in th elobbying effort that they managed to overcome their internal differenceslong enough to fight th e first round of cuts .

Now that city officials are promi sing to soften th e budget blow slightly,it's easy for groups in th e coalition to start fighting among themselvesabout ho w th e ever-smaller pie will be divided. Th e larger policyquestions of ho w th e city's money should be spent are vita l-but theymust be pu t on hold until that money is securely in th e budget. Until then,some unholy alliances are entir ely necessary. 0

Cover photograph by Isa Brito .

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

3/28

1 I ' ~ f j " l i I I

FEATURES

Down the DrainMetering was meant to save water , bu t it threatens todestro y community-controlled affordable housing . 10

Beyond Bricks and MortarThe Banan a Kelly community group in the South Bronxis promoting "values clarification " within the organiza-tion an d among tenants . Are they meeting th e needs ofthe neighborhood-or invading people's privacy? 14

DEPARTMENTS

EditorialUnholy Alliance ....................................................... 2

BriefsRed Hook Wins ..... ......... ..... ... ...... ..... ................... ....4Steisel Threa t .......... ................................................. 4AIDS Deadline ......................................................... 5

ProfileOu r Bodies , Ourselves ........ ........ ...... ............ .... .......6

PipelineMutual Aid ............. .................................................. 8

Vital StatisticsBare Necessities .......................................... ........... 20

CityviewAndrew Cuomo 's Blunt Wedge ............................. 22

Review ... .... ............................. .... ...... ........... ........... ... 24Letters ............ ...... ....... ..... ...... ................... ..... ..... .... ...25

Job Ads ........ ........... ..................... ......... ..... ......... ........ 27

Our Bodies/Page 6

Drain/Page 10

Beyond Bricks/Page 14

CITY UMITS / M A Y 1 9 9 2 /

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

4/28

RED HOOK WINS

Residents of Red Hook canbreathe a little easier afterdefeating a plan by the city'sDeportment of EnvironmentalProtection (DEP) to build a nineacre sludge processing plant intheir neighborhood.

Red Hook is one of the poorest communities in Brooklyn ,an d already carries a heavylood of industrial pollution .More than a year ago, it waslisted as a proposed site for twoprocess ing plants that wouldhelp the city stop dumpingsewage sludge into the ocean .plans for the first plant werecancelled last fall and the citywithdrew its proposal for thesecond plant last month afterfierce gras sroots opposition .

''The plant would have beenthe proverbial straw that brokethe camel's back," says JohnMcGettrick, co -chair of the RedHook Civic Association. "Itwould have been an environmental disaster." The mostlyblack an d Latino community has22 waste transfer stations, acontainer port, 1 etroleumrelated facilities , a deportmentof transportation incinerator,chemical plants an d storagefacilities for toxic waste, accord

ing to Red Hook Citizens UnitedAgainst Sludge (RHCUAS), acoolition of tenants an dhomeowners .

The city's decision to cancelthe second plant was announced in front of 15 0 members of RHCUAS, who gatheredat P.S. 27 to discuss strategiesfor improving the neighborhood . Officials say now thatthey believe Red Hook ha s itsfair share of burdensome cityfacilities .

The plant was slated for thesite of the vacant Revere SugarRefinery on Beard Street, a fewblocks from the Red Hook PublicHousing Development, one ofthe largest housing projects inBrooklyn an d home to morethan 10,000 people . A publicschool an d a library ar e alsonearby . The plant would haveincreased traffic by 20 0 trucksper day along neighborhoodstreets already congested bytraffic from the Gowanus Expressway, which carries150,000 cars an d trucks daily .In the post several years, seven

4 / M A Y 1992/CITY UMITS

homes in the neighborhoodhave collapsed from the vibrations caused by the thunderoustruck traffic.

New York ' s sewag e sludge is

c u r r e n ~ ytaken from the city'ssewage treatment plants bybarge an d dumped more than10 0 miles offshore . The federalgovernment has ruled thatocean dumping must end byJuly . On e of DEP's proposedalternatives is to turn the wasteby-product into fertilizer atcomposting plants around thefive boroughs. Under DEP'ssludge plan , Red Hook wouldhave been the only sludge processing site in Brooklyn .

Edna Mieles, co-chairpersonof the environment committee ofCommunity Board Six, sayscommunity activists in the neighborhood were fighting the construction of a garbage transferstation when they learned ofDEP's plan for the sludgecomposting facilities . 'W e decided to join together the diverse elements of the communityto stop the dumping in RedHook," Mieles says .

But Red Hook ' s victary couldspell trouble for a neighborhoodfUrther south along the Brooklynshoreline. The city is now con-

sidering locating the compostingplant at the Brooklyn MarineTerminal in Sunset Park . CityCouncilmember Joon GriffinMcCabe , who represents both

neighborhoods , is urging herconstituents in Red Hook to helptheir neighbors fight the plantwith information an d support.

Still, the satisfaction of vic-tory cannot be dampened ."Before the fight , we were quietan d passive," soys EmmaBroughton, co-chair of the RedHook Civic Association . "RedHook has been heard , an dwe ' re not going to be dumpedon anymore. " 0 AlbertNickerson

STEISEL THREAT

Deputy Mayor NormanSteisel is threatening to centralize a" of the city's constructionefforts if there aren ' t significantimprovements in the way cityagencies manage projectswithin New York's $4 billioncapital budget .

In a recent memo sent toagency commissioners, Steisel ' s

threat follows his announcementof a vast expansion in the authority of the Mayor's Office ofConstruction an d its director,Rudy Rinaldi, who is also commissioner of the Department ofBuildings . The aim of thechanges is to dramaticallyreduce the amount o f time ittakes to complete most government construction projects .

Many of the city's construction projects have been mired inc o s ~ ydelays for years . Somerecent failures include :

The Human ResourcesAdministration's $2 3 millionrenovation of the Ho"and Hotelfor the homeless, which hastaken four years and still needsmillions of dollars worth ofrepoirs because of shoddyconstruction work;

The transportation deportment ' s reconstruction projectson 14th Street, Eight Avenuean d 180th Street , which lost$6 .2 million in federal fundingbecause of construction an dmanagement defects;

The Deportment of Envi-ronmental Protection's plannedupgrade of the Newtown Creeksewage treatment plant ;

The renovation of 46buildings in Central Harlem bythe Department of Housing

Preservation an d Development .Fo"owing the changes laidout in Steisel ' s memo , the Officeof Construction will go throughall of the agencies' managementprocedures , create a standardized, government-wide systemfor every phase of construct ionan d development, an d helpdetermine which projects ar ebest done in-house an d whichshould be contracted out . In thepost , the office's primary function was keep ing track offinancing for capital projects.The

office will hire several newstaffers, officials say .Rinaldi an d others have

advocated consolidating all thecapital budget projects foryears. Last fall, City CouncilSpeaker Peter Vallone proposedthe same thing, arguing that thediversity of contracting an dmanagement methods a mongall the agencies was costly an dinefficient . The mayor's currenteffort to curtail the growth of thecity's deb t service has broughtthe issue to the fore, says buildings deportmen t spokesperson

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

5/28

Vahe Tiryakian .The administration Rooted

the proposal in a poragraphburied in the preliminary budgetreleased in January . But somecommissioners told Steisel thatthey can better coordinate services an d contracts if they retaincomplete control of their construction prol'ects, according tosources fami iar with the debate .After meeting with the agencyheads, Steisel agreed to put offthe consolidation idea-for themoment .

Some nonprofit housingdevelopers an d managers fearthat the creation of a centralizedconstruction agency wouldsimply ad d another layer ofbureaucracy to contend with .And Manahattan Borough

President Ruth Messinger iscautious about the idea of taking control of construction awayfrom the agencies . "It's a bobyan d bothwater issue," she says ."W e want the capocity to havea city construction agency .That's the boby. But the bothwater is to sa y no commissionershould have the authority to docapital construction ... That'sreally looney." 0 AndrewWhite

AIDS DEADLINE

The clock is ticking: NewYork City has two months tospend $3 5 .9 million in federal

money for AIDS programs orrisk cuts in future funding. Thedeadline is self-imposed, an dis_part of an effort by cityofficials to convince federalbureaucrats that New York iscapable of properly disbursingthe funds, despite serious delayslast year.

The federal governmentawarded the money to NewYork last month . Earlier thisyear, Dr. Billy Jones, chair ofthe mayorally-appointed HIVPlanning Council, met withfederal officials an d promisedthe new money would beallocated to service agenciesand organizations within 90days of the award date in April.Jones was trying to polish thecity's credibility, which wa s

tarnished by last year's spending delay : $3 3 million thatshould have been handed outlast spring didn't begin to trickledown to AIDS groups untilFebruary, 1992 .

The money is New York'sshare of funding under the RyanWhite Comprenensive AIDSResources Emergency (CARE)Act of 1990 . The HIV PlanningCouncil is the city boa rdresponsible for overseeing theuse of the funds. last month,Mayor David Dinkins named

Jones head of the Health an dHospitals Corporation, an d RonJohnson took over as head ofthe planning council.

While AIDS activists criticizethe city for last year's embor-

Privatlution Takes Its Toll: The city's Human Resources Administrationplans to fire mo re than 200 security officers who guard welfare officesaround the city . an d replace them with guards from a private com-pany . The ci ty officers protested in front of the agency 's Church Streeheadquarters last month .

rassing an d costly delays,members of the planning councilfind little to be defensive about ."All of us wish it had happenedfaster," says David Hansell,deputy director for policy atGay Men's Health Crisis an d amember of the council. "But itwas very important that wedevelop a process [for awarding contracts] that wa s fair an d

defensible."New York City's $3 5 .9million award is the largest sliceofa $119.4 million pieapportioned among the 1 8American cities with the highest

reported AIDS caseloods .The city is in no danger of

losing its current award if it faito meet the 90-day target. Infact, the city officially has untilMarch 31, 1993 to distributethese second -year funds . Butpart of each annual grant isawarded on a c o m ~ t i t i vbosis, an d federal officialsconsider the promptness with

which the previous yea r's fundswere disbursed . New York lostpoints because of the recentcontracting delays, officials say,contributing to a $2.5 milliondecrease in the city's competitive grant this year.

Families in the NYCShelter Systemand Where They Stay

The 1992 Ryan White grantamount to only a fraction of thetotal authorized by Congresswhen it passed the CARE Act i1990. While the IElgislation calfor up to $875 million per yearfor five years, the actualappropriation was only $221million in ~ s c a lyear 1991,$280 million in fiscal year1992, an d $307 million forfiscal year 1993 . Some portionof the CARE Act have neverbeen funded, an d are not likelto be in the future.

==15I f'S.... !E

=

6,000 - r- - - - r- - - - r- - , . - - - . . . , - - - - . - - - - - r- - . . . . . - - - - ,

5,000

4,000

3,000

2,000

1,000

o3189 3191 3It2

Source: NYC Human Resources Administration .

Number of families in

each type of shelter, 31'92: Private ~ ITlor 2'.,3,294[ ] Donnitories ITlor 1'.,.HoIeIs[JOllIerTotal Families:

319

1,161

312

5,086

As for New York, if the citydoes not improve its trackrecord in implementing itsfederally funded AIDS rrograms, it may find itsel with anever-diminishing s hare of thealready too-small CAREappropriations. 0 Michael. r ode r

c m U MI TS /MA Y 1992/5

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

6/28

By Abby Scher

Our Bodies, OurselvesThe Women's Health Education Project teachesholistic health in th e city's shelter system.

Th e baby inside Rose's bellykicks! Laughing with pleasure,th e expectant mother lifts uphe r blouse to show he r com

panions, who watch as th e small limbsof th e almost-due baby press againstth e wall of he r womb.

protect th e identities of the batteredwomen.)

Rose offers tha t she needs to discussmenstruation with he r oldest daughter, wh o is 9, bu t she will instruct he rno t to discuss it with her younger

old twin daughters are with her at theshelter, an d it is th e first time in theirlife she ha s had them on her own-hermother undertook most of their carean d Elaine is no t interested in havingan y more children.

A Critical ApproachThe determination an d tenacity of

th e women at the shelter to controltheir ow n sexuality is th e best testament to the importance of WHEP'sprogram. WHEP's goals are no t to simpl y instruct women on proper health

care, bu t to help themto be critical of theinformation they receive, challenge doctors on th e treatmentthey prescribe, an dlook to holistic an dnatural remedies thatthey can obtain ontheir own. In a society where the poores t women an d theirchildren rarely seedoctors except duringemergencies, preventive practices andnatural remedies ca nmean th e differencebetween chronic illness an d health.

"The Black

The group ofwomen sitt ing onmismatched chairs inthe dining room issmall -Mar ia , Rosean d Maggie, wh o all

live at the Women'sSurvival Space, aBrooklyn shelter forbattered women, wh ocome together fo rmeetings with theWomen's Health Education Project(WHEP). The shelterhouses up to 1 3women an d theirchildren for as long asthree months, an d itis one of four sheltersin Ne w York Citywhere WHEP holdsweekly sessions ontopics chosen by th ewomen themselves.

Women Helping Women: (from left) Mary Williams, Elizabeth Cintron, Regina Linds eyan d WHEP teacher Mary Ochoa at the Linden family shelter in Brooklyn .

Women's HealthProject is ou r inspirat ion," says Burrill,wh o ha s been an edu-

MotherlDaughter RelationsOn the chilly spring daythatI joined

WHEP'sgroupatthe battered women'sshelter, they were watching a videoproduced by the National BlackWomen's Health Project on sexualityan d relations between mothers an ddaughters. Issues discussed on screenwere echoed in conversations amongshelter residents-a woman in th evideo expressed fear that as he r daughter moved into the world on he r ownsh e would be affected by the drugculture. Upstairs at th e shelter, a resident remained in her room to care forhe r young son rather than send hi mback to pre-school. Th e day before heha d brought home "new vocabulary"learned from hi s classmates. Is thisth e proper wa y to protect children,th e women wondered.

"She's got to learn to deal with itnow," says Maria, pregnant with he rthird child. (First names are used to

a / M AY 1992/CITY UMITS

sisters just yet. Unlike most otherwomen, whose children live withthem at th e shelter, Rose's sevenchildren are in foster care. Th e courtswill allow he r to reunite with themonly if sh e sets up a home away fromhe r abusive husband, whose angeran d blows fell on th e children.

Just then, Elaine joins us, sleepybu t ready to talk. Maggie ha d wokenhe r up to make sure sh e wouldn't missthe whole meeting. Jenny Burrill, th eWHEP program director running th egroup, asks what topic the womenwould like to discuss in future weeks,an d gynecological issues an d women'ssexuality wi n ou t over parenting . BothRose an d Maria want tubal ligationsafter they give birth , an d they want toknow more about the procedure.

"We as women should know ou rbodies, because when I go to the doctor,he goes, 'You need this an d that,' an dI' m l ike, 'What ar e you talkingabout!?'" Elaine says. Her four-year-

cator with WHEP forthree years. "We see health educationas a vehicle for developing community, getting together to talk. It's morea support group." Th e staff's ultimateaim is to nurture an d develop th ewomen's sense of their ow n power.They also recognize th e limits of theirwork.

"You can tell people their rights,bu t if they en d up in a ba d hospitalreally ou t of it, there's only so muchthey ca n do on their ow n behalf," saysStephanie Stevens, WHEP's currentdirector an d on e its founders. "But ifpeople ca n find out how to take care oftheir ow n needs, the whole community benefits. I t ripples out immediately."

Making th e LinkWhat makes WHEP unique is its

consistent presence in th e sheltersboth a program leader an d educatorgo into each of the four shelters every

singleweek

toconduct

groupson

top-

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

7/28

ics chosen by the women themselves.Using one of New York 's most extensive Rolodexes of resources th e WHEPstaff links shelter residents to educators specializing in such topics asAIDS awareness , stress management ,

parenting skills an d gynecologicalcare. They also prepare resourceguides an d information booklets onabortion and gynecology for th ewomen to take with them , an d negotiate with shelter staff members onpolicy changes linked to health issues.

"The project seems fairly targeted.They teach women ho w to access th ehealth system, an d that they haverights ," says Denise Hylton, projectdirector for New York Connec t, an d amember of the board of th e North StarFund, which ha s given WHEP grants.

WHEP opened its doors in th espring of 1989, on e year after Stevensorganized a day of workshops on th esame model while working at theLearning Alliance . Her organizingsavvy an d self-taught fundraisingskills have kept WHEP going on ashoestring budget of less than$100,000 a year, an d allowed WHEPto develop beyond its original plan ofsimpl y providing a network of educators . Stevens is leaving th e organization , an d its board is searching for adirector with both fundraising an dorganizing skills to ensure financial

stability .Financial constraints prevent theproject from going into more sheltersbu t so does th e inability of shelterstaff to meet certain minimum conditions set by WHEP. The organizationasks that th e staff support th e projectby providing child care for the womenwho attend an d promising no t to intervene in workshops. They also request that the shelter facility have aprivate room where the workshopscan be held. Some shelters can't, orwon't, cooperate.

Transience a ProblemWHEP's groups at the Linden an d

Springfield Gardens family sheltersin Brooklyn and th e Kingsbridgewomen 's shelter in th e Bronx facegreater obstacles reaching women thanthe one at Women's Survival Space .While the battered women's shelter issmall an d fairly cosy, shelters likeKingsbridge house up to 80 women .Attendance at WHEP meetings therereaches 15 at times, bu t th e discussion can be unfocused. Educators mustwork particularly hard to connect withthe women, wh o ma y suffer from

mental disabilities or other problems,says Burrill. Th e transience of theresidents at Kingsbridge also influences th e success of the group-thewomen only stay about three weeksbefore moving to dormitory-style

shelters . Shelter staff members are th emost consistent group participants and

"When I go to thedoctor, he goes,

'You need this andthat,' and I'm like,

'What are youtalking about?!'"

many women only come to on e group.Another element influencing

whether the workshops reach womenis whether residents associate WHEPwith the shelter managers an d citybureaucracy. At the shelter for families in Springfield Gardens, a young

ma n wearing fringed leather wanderedinto the WHEP meeting asking, "Do Igot to be here, is it required?" WHEPprogram director Mary Williams ha dasked th e shelter staff o announce th estart of the session over th e intercom,bu t the tone of the announcementsuggested attendance was mandatory .

"I'm not required to do anythingbu t be Puerto Rican an d die!" th eyoung ma n said , only half in jest.Women at th e meeting noted that someresidents avoid the group, thinking itis on e more way the shelter managerstry to discipline their behavior. AtWomen's Survival Space , two residents reminded the others that th emeeting wa s starting, bu t at Springfield, that task fell to Williams an dtwo WHEP interns , who knocked onresidents' doors to invite ne w participants.

"I know just ho w they feel," saidWilliams, a mother of five who hasbeen homeless twice in her life . "Itwould unnerve me in th e shelter I wa sin when the guards told me to comedown. You 're constantly on edge whenyo u 're in a shelter situation. When I

was homeless, I didn't want no one

coming in from the suburbs to tell mwhat to do ."

Despite these obstacles, WHEP staffare seeing th e results of their work atLinden, Kingsbridge an d SpringfielGardens. Linden women successful

organized for more nutritious meaan d a ne w caterer with a petitiodrive an d letter writing campaign.a recent parenting workshop atKingsbridge , chemistry sparkedbetween the women an d an educatowho demonstrated ho w to nurturchildren by serving cookies an d mian d creating a party-like atmosphereOne young pregnant woman at a receworkshop on non-prescription druat Springfield Gardens tentativelyasked about childbirth educationclasses. "I do n 't really need it now, it'stoo late ," sh e said, and the WHEeducator running the workshop ananother resident encouraged herfind ou t more about what decisionsh e could make before delivery.

When members of th e workshopdemand rights an d information thatthey want , in a safe place where thedon't have to conform to th e requirments of the city shelter or hospitalsystem, WHEP educators knowthey 've me t their goals.

"We tr y to give them informationwithout someone coming in withcondescending a t t i tude ," say

Williams. " You show them the dooshow them th e steps an d say, 'Honego for it because I know yo u ca n dit . '" 0

Abby Scher is a freelance writer livingin New York.

ADVERTISE You RJOB OPENING

IN CITY LIMITSReach thousands

in the nonprofit community!

Cost: $40 for 50 words.

Call : 925-9820 .

Deadline: The 15th of themonth before publication.

CITY UM"S/MAY 1992

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

8/28

By Aaron Jaffe

Mutual AidMicroenterprise loan programs demand that smallbusinesses rely on their peers.

Aussian immigrant who worked

as a civil engineer in hi s homeland can't get that kind of job inth e United States. He wants to

start hi s ow n cleaning b u s i n ess -carpets an d furniture an d just aboutanything else that customers ask hi mto do. A ma n from EI Salvadorwants to bu y an auto bodyrepair shop, so he can takeadvantage of the years of experience he had back home.Another woman, also from ElSalvador, makes dresses withan ol d sewing machine in he rapartment.

These are the people JohnWaite wants to help.

Waite, director of th emicro enterprise program atth e Church Avenue Merchants' Business Association(CAMBA) in North Flatbush,Brooklyn, saysmicroenterprises ma y be animportant part of helpingthese an d other small entrepreneurs to escape poverty."Our purpose is to workwith these people wh o havenowhere else to turn," he says.

Microenterprise loans area ne w phenomenon in the seaof economic programs forlower-income New York businesses. They're meant forpeople who wouldn't normally be able to get a . bank

"These people are becoming entrepreneurs no t because they have anM.B.A., bu t out of necessity," saysDelma Soto, executive director ofACCION New York, a microenterpr iseloan project based in Williamsburg,Brooklyn. "I have an M.B.A. an d I

international success with the modelis ACCION International, a 31-yearol d program based in Cambridge, Mas-sachusetts. Working mostly in LatinAmerica, ACCION has about 100,000clients an d more than $55 million in

outstand ing loans, with payment ratesof he same caliber as Grameen's. Now,Soto is trying to make the ACCIONsystem work in Ne w York City, withfunding from a combination of foundations, banks an d low-interest loans.

So far, ACCION Ne w York has onlymade loans to people whose businesses have been operating for at least

a year, even if they are assmall as a food cart on thesidewalk. The organizationbegan distributing loans of upto $2,000 in Williamsburg lastJuly 30, an d by February 1, ithad loaned $73,400 to 36people . So far, none of th eclients, wh o operate businesses like restaurants ,bodegas an d food vans, havedefaulted on payments . Theloans ar e mainly used forworking capital, Soto says,which could cover anythingfrom rent to light bills to moreplantains to basic repairs.ACCION Ne w York doesn'task for item by item accounting.

CAMBA's loan p rogram isstill being hammered together,an d won't start handing outmoney until later this month.Bu t Waite says he is alreadymeeting with prospectiveclients. Not all of them are

Vi happy with the peer groupu:: idea. "We went into class~ rooms with Russians and!ii some other ethnic groups,"

loan, would -be entrepreneursputting together small, laborintensive businesses with vir

Under the EI: Williamsburg's Broadway, where small businesses are Waite says. "The response wasfeeling the pinch of recession. mixed. Many people said, 'I

don't trust other people. Itually no credit history, littlebookkeeping experience an d very littlecollateral. All they have to put up forthe money is their wo rd -an d th eword of three or four other would-beentrepreneurs from th e same community.

That's th e trick to microenterpriseloans-support groups made up offour or five peers, each of hem receiving a loan for their business an d eachof them responsible for one another.Instead of material collateral, th e syste m is based on honor an d mutualdependence. Its a wa y to help people

take care of themselves.8 / M A Y 1992/CITY UMITS

couldn't begin to do what some ofthese people have done with the obstacles they've ha d to overcome."

The Bangladesh ModelThe best known model for th e

method of peer-group loans is th eGrameen Bank in Bangladesh, whichstarted giving microenterprise loansin 1977. A 98 percent repayment rateon an average loan of just $67 openedeyes in the United States, where poverty in some neighborhoods is nearlyas ba d as in some third-world nations.

The organization that has the most

don't want to have to dependon other people an d I don't want themto have to depend on me.'"

These sentiments are echoed bySoto. "I n a place like Colombia, peopleare more willing to participate in th eprogram an d they're no t as leery an dskeptical. In Latin America, you'reno t dealing with the phenomenon ofpeople being locked behind their doorsan d being petrified of everyone else.You can't just walk into someone'sstore (in Ne w York) an d tell them thisis what you're doing an d this is wh oyou are because they don't knowwhether to b e l i e v ~you."

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

9/28

Doubting th e NeighborsMany small business people in

Williamsburg have th e same doubts.Simon Espinal has seen th e comingsan d goings under th e elevated tracksalong Williamsburg's Broadway for

nine years. That's ho w long he's ownedth e Espinal Mini-Market, which sellseverything from mammoth-sizedbottles of malt liquor to rolling papers,diapers, detergent and cookies.Espinal says the business climate ha sworsened in Williamsburg in th e lastfew years. "Business is bad. A lo t ofpeople aren't working and the factorieshave moved out of here."

Espinal spends $1,550 a month inrent for hi s small store, twice what hepaid in 1984. He's breaking even,barely, he says. Bu t th e dire straits ofsome of his neighbors make himwonder if a peer group makes sense.Carlos Guanta, who's owned a pizzarestaurant down the block for twomonths, agrees. "Wha t if th e otherbusiness [in the peer group] fails?" heasks.

Bu t Jeff Stern of the Local Development Corporation of East New Yorksees i t differently. He's working withth e East Williamsburg Valley Industrial Development Corporation to starta microenterprise program with partof a $200,000 grant th e groups receivedfrom th e state Urban Development

Corporation. The peer groups "providestronger ties so people don't take th emoney and run," says Stern. "I tminimizes risk."

Minimizing risk is definitely important to CAMBA's Waite, wh o worksprimari ly with immigrants fromSoutheast Asia, Russia an d EasternEurope, along with immigrants fromthe Caribbean Islands an d LatinAmerica. Many of hi s clients don'thave a good credit history. Anotherproblem, he says, is that many of he mare recognized by the government aspolitical refugees from their homelands, meaning they automaticallyqualify for public assistance a monthafter arriving. "Some of them get usedto it," he says .

News of the international successof microenterprise programs ha s attracted attention at th e federal level,where two bills supporting th e modelare winding their wa y through thehouse. Rep. Tony Hall (Democrat,Ohio), the cha irman of the House Select Committee on Hunger, introducedth e "Freedom From Want Act" lastMay. Part of the bill seeks to expandcurrent employment and training

projects to include microenterprises,making it easier for people on welfareto start businesses without having theirbenefits curtailed.

Stafford, an associate professor at NYork University's Robert F. WagneSchool of Public Service an d a membof the board of th e city's EconomicDevelopment Corporation. "Micrenterprises are no t a panacea by the

selves." 0

Labor experts say microenterprisesare far from th e complete answer to

poorentrepreneurs'fiscal woes. "Theyhave to work with other things likerevolving loan programs-a wholepackage of programs," says Walter

Aaron Jaffe is a reporter for th e AsiWall Street Journal Weekly

--The Homeless A r e NotT h e Criminals!

T he Sys tem Is!"on red background.

To order this button: Send$1.00 and self-addressedstamped envelope to:

RHN, Box 39 , 228 East 10th StreetNew York, New York 10003

Now we meet moreinsurance needs than everfor groupslike yours.

For nearly 20 years we've insured tenant and communitygroups all over New York City. Now, in our new, largerheadquarters we can offer more programs and quickerservice than ever before . Courteously. Efficiently. And professionally.

Richards and Fenniman, Inc. has always provided extremelycompetitive insurance programs based on a careful evalua-tion of he special needs of our customers. And because of he

volume' of business we handle, we can often couple theseprograms with low-cost financing, if required .

We 've been a leader from the start . And with our newexpanded services which now include life and benefitsinsurance, we can do even more for you. For information cal/:

Ingrid Kaminski, Senior V.P.(2r2) 267-8080, FAX (2r2) 267-9345

Richards and Fenniman, Inc.12 3 William Street, New York, NY 10038-3804

Your community housing insurance professionals

em UMITS /M A Y 199

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

10/28

Down the DrainMetering wa s meant to save water, but it threatens to destroy

community-controlled affordable housing .

BY BILL LIPTON AND ANDREW WHITE

It' s nothing more than a little gray bo x with dials an dnumbers that began appearing on the basement walls ofapartment buildings across Ne w York City a few yearsago. The me n and women that installed it ha d only th ebest of intentions: conserving New York's water sup

ply. But th e water meter is changing the way New Yorkerspa y for one of their most basic commodities, an d itpromises to wreak havoc for low-income housing acrossth e five boroughs.

Water meters are part of the city's grand solution to anunrelenting crisis: upstate reservoirs are currently onethird below capacity, an d New YorkCity is threatened with its fourthdrought emergency in 10 years.That's only part of the water proble m in this town; at th e other en d ofth e pipeline, after th e toilets flushan d th e storm drains overflow, th ecity's sewage treatment plants areso overburdened that the city must

cu t i l legal discharges into th eHudson an d East r ivers -or facefines and contempt charges in civilcourt.

By billing consumers for th e wate r they actually use, instead of aflat-rate estimate as in th e past, th ecity hopes to dramatically cut theamount of water flowing through th e system. Logically, aconsumer charged for actual use is more likely to us e lesswater an d thus save money .!3ut th e conservation programis displaying a nasty side effect that city officials are onlybeginnin g to recognize. While the new meter-based billingmethod cuts water an d sewer bills for many New York Cityapartment houses, th e cost of those services in denselypacked low-income housing is becoming astronomical.

"There is a fundamental inequity in this," says DavidSteinglass of the Community Housing Association ofManagers an d Producers (CHAMP), a group of community-based housing providers. "It's all wrong," he says."The more people in your apartment, the more water youuse, period. It's a head tax."

Steinglass an d other affordable housing advocates argue that water an d sewer charges are a regressive tax,falling disproportionat ely on the poor and the homeboundan d threateni ng to undermine years of work spent assembling a still-small stock of community-controlled affordable housing.

"This could be the last nail in th e coffin," says Dalma

Delarosa, president of the Northwest Bronx Community1 0 j M AY 1992j CITY LIMITS

an d Clergy Coalition, which works to preserve and developlow-income housing. If th e water authorities don't dosomething soon, sh e says, "Our buildings will go down th edrain. We 'll have to forfeit them to th e city. I see no otherway."

Years of DroughtFo r now, th e city is giving building owners a temporary

break from ay ing th e meter-based bills, allowing them topay the 01 ,estimated charges instead for th e first yearafter meters are installed. But water rates in general havedoubled in th e last five years, partly to cover th e cost of theextensive conservation an d maintenance effort that began

in 1986 following two successiveyears of drought. So even th e oldstyle estimated bills are putting astrain on the budgets of low-income cooperatives and nonprofitowned and managed buildings.

But affordable housin g advocatespoint to evidence that metering willonly make it worse. They ar e

demanding permanent changes toguarantee that poor people don'tend up footing th e conservationbill.

They argue that plumbing isfundamentally different from wirin g an d gas piping, and can't bemetered the same way. Fo r one

thing, it 's impossible to measure use in every apartmentonly whole buildings can be metered, so those wh o conserve subsidize those wh o don't. Besides, old plumbingoften leaks, an d most poor people live in ol d buildings.People without jobs-whether they are retired, disabledor single parents-spend more time at home, runningwater, taking showers, flushing toilets. An d many poorNew Yorkers live in apartments with numerous familymembers an d relatives . The more people in an apartment,th e more water goes down th e drain.

Th e different conclusions reached by two recent studies underline th e inequities of metering and water rateincreases. One, by th e plumbing industry, showed that the"average" New York apartment building can cut its waterbill in half by installing a water meter. But the plumberswere looking at buildings of every income level. Meanwhile, Irene Baldwin of th e University NeighborhoodHousing Program (UNHP), which helps to developaffordable housing for Bronx families, gathered data onexclusively low income buildings, both metered an dunmetered, an d found an average increase of about 33percent in water charges from 1990 to 1991. -

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

11/28

Breaking Budgets: Mercedes White an d her neighbors outside their lo w income cooperative in the Bronx . Their water bill went up more than 50percent last year. They expect next year's to be even higher.

"You're going to find that a building in Manhattan, allsingles an d couples, their bills will go down," says JimBuckley of UNHP . "I n those buildings people get homelate at night, they clear ou t for th e weekend," he says. "Butbuildings like ours that have families, that's no t so ."

360 Percent Increase

On e building in Buckley's program, 824 East 181ststreet, recently received meter-based water an d sewer billstotalling $12,794 for a five month period in 1991. Thewater an d sewer bill for th e entire previous year, 1990, wascalculated on the old frontage formula an d came to only$6,666. That's a 360 percent increase in on e year.

A few years ago, the building wa s derelict, vacant an downed by th e city. With funding from th e EnterpriseFoundation, th e city an d other sources, Bronx United InLeveraging Dollars (BUILD), a community housing group,renovated th e shell an d created 31 rent-stabilized apartments with monthly rent s ranging from $215 to $383. Thetotal rent roll is only $9,200 a month. Jim Mitchell, directorof BUILD, says hi s budget based on that rent roll cannot bestretched to cover such a huge water payment. Like othersubsidized projects, the building has a special reservefund, bu t that fund is no t going to cover many years worthof such huge bills. "I don't know where else we can look,"Mitchell says. "It's a matter of fact that if we don't pay thebills we'll go on an in rem list," he adds, referring to th ecity's list of delinquent taxpayers, "and eventually th e citywill get the building back."

Mitchell's experience is no t uncommon. One newlyrenovated, 64-apartment complex for formerly homelessan d low-income seniors an d families on the Lower EastSide paid 170 percent more than ha d been budgeted lastyear on its water bill. Lee Chong of Asian Americans forEquality, which manages the property, says th e budgetwas based on a city housing department analysis of pre vious water bills. Bu t it was miles offbase. "Obviously it will

get higher an d higher," she says. "These are people wh oare at home flushing toilets all day. I'm worried in th e lonrun. Income will no t keep up with these bills."

Grace Period

While city officials deny the charges are as regressive asadvocates claim, they admit there's a problem. An d t

ease the trans ition to meters, an d hel p owners an d managerfigure ou t ho w to conserve water, th e city's Department oEnvironmental Protection (DEP) has offered ratepayers aon e year grace period during which they can choose to patheir bill based on the old estimate system.

The city says it ha s no choice bu t to push ahead withconservation efforts. Assistant Commissioner StevenOstrega of DEP insis ts that increases in meter-based watebills ca n be reduced by installing toilets an d showerheadsdesigned to cu t water use. He adds that landlords mustmake regular inspections for leaks to keep their billunder control. In response to complaints, hi s departmentis seeking approval from the city's mayorally-appointedWater Board, which regulates th e rate system, to extendth e grace period on meter-based bills to two years, or threyears if owners install th e conserving fixtures. He hopesto create a rebate program to encourage owners to inst allth e least-wasteful toilets available.

Bu t Ostrega downplays the criticism from affordablehousing advocates. "This is a small number of peoplemaking it sound like the world is caving in," he says . Eveso, he agrees that buildings where more than four peoplelive in most apartments will see their bills as much adouble under the metering system. And he says the cityshould find a better wa y to ease th e burden. That doesn'tchange hi s essential message, though. "Conservation hato catch on," he says. "This is nothing compared to whait'll cost if we have to build new reservoirs an d ne wtreatment plants."

Housing advocates don't deny that conservation iCITY U MI TS /MA Y 1992/11

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

12/28

necessary. But they have proposed some methods toreduce the impact, including passing some of th e cost ofth e water infrastructure into the city's property tax base.As it no w stands, ratepayers' bills cover th e operatingcosts of the system as well as th e debt service on moneyborrowed to pa y for its expansion an d repair.

Andy Reicher of th e Urban Homesteading AssistanceBoard supports legislation to create a cheaper water ratefor low-income buildings. He proposes a rate scale thatmakes conservative use cheap for everyone, an d wastefuluse expensive for everyone. But buildings filled with lowincome families should be given a special, extra-cheaprate for a reasonable amount of water, based on the numberof people in th e building. I f hey use more than that, theywould get socked with a high rate; if he y don't, their waterbills would stay very low.

Double TaxationBut until some kind of solution is worked out, housing

controlled by nonprofits an d cooperatives is not the onlysore spot. Unregu lated tenan ts o f for-profit landlords inol d dilapidated buildings are finding that higher wateran d sewer charges translate into higher rents. An d ownersof rent-stabilized buildings are pressuring rent regulatorsto authorize rent increases greater than the four percentallowed last year.

ada Friedheim, a tenant advocate on the Rent Guidelines Board, which determines annual allowable increaseson rent regulated properties, says owners' groups want theauthority to pass along th e increased cost of water an dsewer charges to their tenants. Sh e says the board isn 'tlikely to allow owners to charge tenants directly for thewater an d sewer costs . Instead, "It's becoming a fig leafbehind which you do all kinds of other things," sh e says.

" I t adds to th e hysteria behind raising the guidelinesthemselves. "

Friedheim an d other tenant advocates point out thatleaks an d decrepit plumbing systems are a common problem that landlords often ignore. Charging tenants for th eexpense of water would amount to a doub le tax, sh e s a y s

they already have to tolerate th e water damage from pipeleaks in ceilings an d walls; soon they may have to pa y forth e wasted water as well.

Yet the most precarious buildings are th e ones ownedan d managed by low-income families themselves-thelimited-equity cooperatives created by tenant associations in formerly city-owned buildings. Tenants purchased 2131 Clinton Avenue, a 31-unit building in th eTremont section of the Bronx, from th e city on June 14,1991, an d nearly every apartment houses a family withchildren. Mercedes White, president of th e cooperative,says th e city did a lot of major repairs before th e closing.Bu t the co-op is currently spending its monthly maintenance fees on repairs inside apartments so their residentsca n qualify for federal rent subsidies.

This winter, 2131 Clinton Avenue received a meterbased water an d sewer charge of $15,091, covering a 14-month period. The frontage-based estimate for th e sameperiod would have been $9,380, according to DEP. Thistime around, White is confident they can pay the bill. "Ithink we ca n make it," she says. But i f a bill of that sizecomes around next year, th e budget could come close toth e breaking point.

"I've worked that building since da y one," sh e says. "Idon't want to have done all that for nothing." 0

Bill Lipton is a housing coordinator at the Urban Home-steading Assistance Board.

Privatizing the Water System-In Name OnlySkittish politicians playing games with paper slipped

an expensive mickey to th e public when they pr i vatizedth e city's water an d sewer system in th e mid-1980s,critics say. An d they ma y have a point, since water rateshave soar ed ever since.

During th e mid-1980s, a series oflegal maneuver ingsseparated th e funding of water and sewers from thecity's tax base, removing responsibility over rate settingfrom elected officials. The water supply system ha dbecome so decrepit, and the need for expanded sewagetreatment capacity so pressing, that city officials decided an independent authority could finance the workmore efficiently than th e city.

They also decided the cost of the work should bepaid for with bonds, an d the debt incurred would becovered by water rates, no t general taxes. In 1985, statelegislators created th e New York City Water FinanceAuthority to sell th e bonds, and the New York CityWater Board to set th e rates. Technically, the mayorallyappointed, seven member Water Board also owns thesystem, leasing it back to th e city, and contracting withth e Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) forits operation.

Peter Judd, a former DEP official whose recent report

1 2 / M AY 1992/CITY UMrrs

"More Expensive than Oil" summarizes the burden ofth e increasing water rates on low-income housing, saysth e mid-1980s reformation of the system were "papersteps having no effect on the operation of the systemexcept for one key element: rate setting was removedfrom elected officials to an appointed board."

And, as Judd and Comptroller Elizabeth Holtzmanargue, the board is no t accountable to th e public. Thatlack of accountability in rate setting has led to higherrates an d inefficient services, Holtzman says. She pointsout that "DEP ha s little incentive to control costsbecause rates charged to the public are automaticallyse t to cover expenses."

Judd also criticizes the city government for payingless than it should for th e water it uses. Th e city'spayments to the Water Board are "ludicrously disproportionate" to what a private owner would pa y for thesame amount of water that city-owned housing, hospitals, offices an d other facilities actually consume, hewrites. While th e city "privatized" th e system, it stillretains enough control to cu t itsel f a deal. The result isthat instead of the city raising taxes to pa y for its actualwater consumption, the rest of us pick up th e tab on ou rwater an d sewer bills. Bill Upton

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

13/28CITY UMITS /M A Y 19921

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

14/28

Kelly Street, 1992

Beyond Bricksand Mortar

The Banana Kelly community group in the South Bronx is promoting"values clarification" within the organization and among tenants. Are they meetingthe needs of the neighborhood-or invading people's privacy?

BY LISA GLAZER

Fom th e outside, 800 Fox Street looks like almost

any other building managed by the Banana Kellycommunity group in th e South Bronx. Th e bricksare scrubbed clean, there's a secure lock on th efront door an d gray metal mailboxes in th e hallway.

What makes the building unique is the tenants inside:18 formerly ho meless families wh o have been through alengthy, therapy-style "values clarification" program thatis no w being used in all Banana Kelly buildings.

When th e tenants moved into 800 Fox Street, theysigned a special rider to their lease. In no uncertain terms,they promised to attend tenant meetings, help maintaintheir building and spend at least eight hours a weekimproving their l ives-or risk eviction.

The "tough love" lease at 800 Fox Street is a clearillustration of th e changes occurring at the Banana KellyCommunity Improvement Association. Started 15 yearsago on a banana-shaped section of Kelly Street, th e groupbegan as a struggling urban homesteading effort. Todayit's a $7 million, 100-employee community developmentcorporation that manages 26 buildings with more than1,000 tenants.

1 4 / M A Y 1992/CITY UMITS

Across th e city, other community groups followedsimilar paths during th e 1980s, winning governmen t contracts an d corporate support to rebuild th e city's decrepithousing stock. They became housing developers an dmanagers, an d they've responded in a variety of ways totheir landlording tasks in troubled neighborhoods . AtBanana Kelly, th e organization is getting closely involvedin the personal lives of tenants-even though many peoplesay this is wa y out of bounds for an y landlord, even on ewith deep roots in th e community.

All of Banana Kelly's buildings no w have a lease ridersimilar to th e one at 800 Fox Street, an d tenants are alsoexpected to attend meetings with Banana Kelly staff todiscuss community values an d implement those values intheir life, accor ding to Yolanda Rivera , th e organization'sacting director.

"We're living in a time when we need each other likewhen we were born ," sh e says. "I really believe community development corporations are important. We're th eonly vehicle there is to help people integrate into society."

"We're saying let's take control of th e only thing we cancontrol-ourselves ," adds Aureo Cardona , a vice president at th e National Center for Housing Management, a

Washington, D.C. group that helped Banana Kelly devise

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

15/28

its ne w approach.After a decade devel

oping affordable housing,this is a major transitionfor Banana Kel ly -andcommunity advocates

across th e city are only beginning to come to termswith th e change. Some sayit's a pragmatic and compassionate attempt to builda sense of community inan area hard hit by unemployment, homelessness, drug abuse andviolence. But others say thene w focus avoids dealingwith how society causesmany of those problemsand borders on "thoughtcontrol" of a vulnerablepopulation.

buildings an d fi x them upon their own. They followed in th e footsteps oth e Harlem Renegades an dthe People's DevelopmenCorporation, two once

prominent groups thahelped create the conceptof urban homesteading inthe 1970s.

From these early daysBanana Kelly ha s grownwinning millions of dollarworth of government contracts, employing scores olocal residents and rebuilding much of th e immediate neighborhood.Along the way, the group'srelationship with the community changed.

I f there's any point ofagr.eement, it 's that BananaKelly 's efforts are part of agrowing national trendpromoting ind iv idualresponsibility among th epoor. Like welfare reformand attempts to sell publichousing to tenants, it 's anideological chameleon that

In Transition: Banana Kelly staff members on Fox Street. Yolanda Rivera,the acting director , is standing in the front near the middle, wearing araincoat.

"At one time they werseen as a beacon, as trailblazers," says John Robert,th e district manager of thelocal community board."But no w we get complaints at ou r communityboard meetings about ho wthey manage some of theirbuildings. There 's a gradual

confounds th e traditional boundaries of conservative an dliberal social policy.

Onl y 15 years old, Banana Kelly is one of th e mostfamous community groups in America. Its accomplishments have been touted on public television,applauded in the pages of the Wall Street Journal

an d held up as an inspirational model of urban success.It all started on Kelly Street with th e Potts family. Like

many working class blacks, they moved to New York fromthe south in th e 1950s an d ended up unhappy in anovercrowded tenement. But by 1963 they scraped together$3,000 to make a small down-payment on an apartmentbuilding on Kelly Street. Frank Potts fixed up th e building,rented the apartments an d eventually bought four more

an d managed another, keeping a close eye on the block.But by the mid-1970s th e South Bronx was burning. Th erecession sparked a cycle of abandonment an d arson an dentire blocks went up in flames.

On Keily Street, th e city took over three abandonedbuildings and announced plans to demolish them. LeonPotts, Frank's son, played basketball with a local socialworker, Harry DeRienzo, and they discussed their fearsthat if three buildings were dynamited, it would be thebeginning of he en d for th e block. They set ou t to mobilizeth e neighborhood, putting up signs that summed up theirgoal: "Don't Move, Improve!"

Working with about 30 neighbors, the activists start edsmall, cleaning out the rubble from a vacant lot an dtransforming it into a community garden. But then theydecided to defy th e city and take over the abandoned

decay of confidence.Certainly they're seen as part ofthe establishment . . here'a perception that Banana Kelly acts for Banana Kelly'ssake rather than for the community's sake."

Walking along Kelly Street an d through the surrounding neighborhoo 'd, it 's hard to measure whether that perception is widespread. On every sidewalk, and in evergraffiti-strewn entranceway, people express differenopinions: respect for the community organization thafixed up the buildings, derision an d complaints for th elandlord that ignores tenant complaints. These divergenviews are mirrored by the surrounding landscape. Muralsenliven the sides of buildings, there's a wide, green p ~with a baseball diamond, and block after block of newlooking brownstones, tenements, an d townhouses. BuBanco Central of New York is shuttered, and the area ipockmarked by fields of brick, glass, refrigerator carcasses,tin cans an d crack vials.

Walking past one of these lots, a group of six teenagegirls push each other, giggling, jostling, gossiping. Onepoints to the other an d shouts for th e entire stree t to hear"You're an industrial strength drug dealer!" Drug dealstake place in this neighborhood in broad daylight-aconstant reminder of the challenges still facing BananaKelly.

The preface to an outline of Banana Kelly's newFamily an d Community Enrichment (FACE) programreads, "We are not doomed to pain and sufferingWe ca n change what we do no w by seeing that lif

is in our hands. No matter how hard this is to admit, wechoose our misery an d make it a wa y of life or choose to

CITY UMITS/MAY 1992/15

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

16/28

gain strength to make better choices and lead a moresatisfying life."

Helping people caught in poverty change their lives isno easy task. But that's exactly the aim of the FACEprogram, a three-step program that sounds a lot like grouptherapy. It's designed to accentuate th e role of social

values in every day life. In the first step, a Banana Kellystaff person meets with tenants and they trace whether ornot their behavior mirrors their values. In the secondphase, th e staff person rejects behavior that is consideredirresponsible, an d introduces the idea that people need toplan, act an d reflect to make change meaningful. In the lastphase, the staff person works with groups or individualsto help them define an d achieve their goals for changein their personal life and in th e community.

"The whole idea . .is about helping people identify th etools they need to make it through the day an d th e rest oftheir life," says Carlos Permell, th e 25-year-old director ofth e Family and Community Enrichment program. "This isabout rebuilding community an d looking ou t for oneanother, about caring. It's pr imarily abo ut love."

The most tangible aspect of the ne w program is BananaKelly's lease rider, which requires tenants to spend eighthours a week improving their life an d contributing to th ecommunity. Tenants can meet their commitmen t throughworking, studying, taking part in job-training, drug oralcohol treatment or providing community service.

Yolanda Rivera, th e acting director at Banana Kelly,says th e reality of life in th e South Bronx makes valuesclarification necessary-families an d schools are failingmiserably an d it's up to Banana Kelly to step in to th e fray.Although this can sound paternalistic, Rivera insists thatth e new approach empowers tenants by weaning them offtheir dependency on welfarean d social services. The mostpowerful role of a communitydevelopment corporation is toprotect people from social service providers, th e educationalan d mental health systems an dtheir concepts for promotingchange, sh e says. "We teachpeople, 'Don't buy into thatstuff! Reach into yourself forth e answers!"

The move toward instilling values-oriented actionamong tenants is a recent phenomenon at BananaKelly. Yolanda Rivera has only been in charge for ayear, taking over from Getz Obstfeld, wh o was

director from 1982 to 1991. The tw o have vastly differentstyles, which underscore where Banana Kelly has come

from and where it is heading.Raised in Brooklyn, Obstfeld dropped ou t of collegeand joined th e urban homesteading movement in the1970s. Under his direction, Banana Kelly grew into a miniempire of management an d construction services, teenageeducation projects an d a host of government-funded housing deve lopment programs. But members ofBananaKelly'sboard of directors say Obstfeld wasn't equally skilled atsharing power, which dampened staff morale. There wasalso resentment that a white ma n was running a community group in a black an d Latino neighborhood, leadingsome board members to try an d oust him in th e mid-1980s.

Rivera wa s on th e board at th e time, and says she didn'tsupport th e effort to dismiss Obstfeld. But the conflictfocused her attention on the neighborhood and promptedher to become chairperson of the board and, eventually,acting director.

Rivera was brought up in the South Bronx in a buildingthat the landlord abandoned and the tenants now own.She's worked for a social service agency in Hunt's Pointan d served as a mediator in th e housing court of Connecticut.

When Rivera took over the leadership of Banana Kelly,sh e began to explore th e organization's relationship withthe community. Sh e knew Aureo Cardona, who used towork in the South Bronx, and hired th e National Center forHousing Manag ement (NCHM), as a consultant. Creat ed in

1972, NCHM is the brainchildof Roger Stevens, a formerPolaroid executive who hasadapted corporate theories tohousing management (Seesidebar).

NCHM helped design th evalues-based training programfor 800 Fox Street. They alsotook the Banana Kelly staffthrough an internal process ofvalues clarification. By all accounts, it was a painful ordeal."I put th e whole organizationthrough some internal soulsearching," Rivera says with a

rueful laugh. "We're still recovering!" The pricetag for NCHM'sservices? About $120,000.

Once the Banana Kelly staffan d the tenants at 800 Fox Streetcompleted th e NCHM program,Rivera decided to modify itsomewhat an d tr y it with therest of th e organization's tenants. This was the genesis of theFACE program.

Once basic communi tyvalues are instil led, Rivera saysBanana Kelly steps away, respecting tenants' ability to acton those values in th e outsidecommunity. I f a group of tenants decide they want to get ri dof drugs on their block or bringin a new da y care center, Banana Kelly will provide adviceor support. But there are nopaid community organizers onstaff to lead th e effort. Why?Because that also fosters dependency, according to Rivera."I believe dependency is a formof slavery," sh e says. "We haveto check our own behavior tomake sure we're no t perpetrating what we want to stop."

Homebuilders:Lorena Cruz in her home steading building onFox Street .

The program is still so ne wthat its impact on tenants ishard to discern. Many of themstill talk about Banana Kelly thesame wa y they would talk about

1 6 / M A Y 1992/CITY UMITS

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

17/28

any landlord. Others have strongfeelings about their landlord'snew methods of community andpersonal improvement.

Lorena Cruz is the presidentof th e cooperative board at a

string of newly-renovatedhomesteading buildings thatstretch from 81 1 to 82 7 FoxStreet. Sitting in her spaciousnew living room, she says Banana Kelly is co-managing th ebuilding an d she sometimes hasto prod staffers for documentsor assistance, bu t she doesn'tmention th e ne w philosophy atall.

in. "Each one of my kids hastheir own bedroom," sh e says."You can't beat something likethat."

Aeport commissioned by

the National Center forHousing Management onth e training program at

800 Fox Street offers a vividaccount oftwo years of struggle.Despite rigorous scre ening fortenants, there have been problems with drug abuse, domestic violence, racism an d resentment between neighbors. Buteven with all ofthese problems,advocates in Ne w York an dacross the country have widelyvarying opinions about whethera community group managingbuildings should impose a seof values on their tenants.

Around the corner at 783Beck Street, th e building looksclean on the outside bu t one

stepthrough the

front dooran d

there's graffiti sprayed acrossth e hallways. "As long as I'velived here I felt they did a verypoor job as far as the upkeep ofthe building," says ElizabethHughes, t reasurer of th ebuilding's tenant association.Clara Solomon, th e vice presi

Maintenance Problems: Clara Solomon an d Charles Thompsonat 783 Beck Street.

Some express support for th egeneral idea. "There's a needfor work on values at all lev-

dent, adds, "They took me to court 99 times. I f I was adollar behind they would have me in court."

But Charles Thompson, the president of the tenantassociation, is enrolled in a leadership development program ru n by Banana Kelly and the Coro Foundat ion. Heknows about th e ne w approach. "They're helping us comeup with different ways to help ourselves," he says. "Fromwhat I see now, Banana Kelly is reaching out to us. Theycan't take yo u out of all th e chaos you're in bu t they'relending a hand. I used to be one of th e fellas hanging outin front of the building drinking a quart of beer. I knowthey're helping me. In a way, that could benefit them, bu tI'm trying to keep my eyes open."

Inside 800 Fox Street, Lourdes Rivera lives in a secondfloor apartment and knows all about the values-basedtraining. "At first it was wonderful but then it changed,"sh e says. "Banana Kelly an d the tenants couldn't workthings out. We signed a contra ct before we moved in thatsaid we ha d to go to tenant meetings. For them if you didn'tcome it wa s like breaking the law because yo u were

breaking th e contract. Then reople started to back up, a lotof tenants were saying, 'WeI, I don't care, you can do whatyo u want, an d I'll do what I want.' They pushed ou rbuttons . .it always ha d to be their way."

Her upstairs neighbor, Cynthia Burrell, adds, "We wenton a retreat when we first moved in about what BananaKelly can do for yo u an d what yo u can do for Banana Kelly.I t was very good. All of the families in here were homeless-when yo u get out of a situation like that you can loseyour values." Speaking of her own situation, she says,"When I was homeless, I didn't stop. I was in college, I keptmy kids active, I wasn't lost."

Asked to name the best part of th e Banana Kelly program, she doesn't mention any of th e orientat ion sessions,

th e tenant meetings or th e values-setting concepts. Instead, sh e looks around her at the apartment she's sitting

els," says Andy Mott, a staffmember at the Center for Community Change in Washington, D.C. Returning from a conference on families, he says"One of the themes at th e conference was th e Africanproverb that it takes a whole village to raise a child. That'sthe reason why the whole community should be concerned about everyone's values."

But is so-called "values clarification" the appropriaterole for an organization that could use personal information gleaned in th e process to evict tenants in housingcourt? ' 'I'm not sure the landlord should be doing this ..bu tthese are no t landlords in the traditi onal sense," notes RonShiffman, th e director of th e Pratt Center for Commu nityan d Environmental Development, which has providedadvice for community-based housing groups across thecountry.

He adds, "I"m concerned that all of this shifts responsibility to families an d individuals an d blames th e victimrather than societal inequities. But I think yo u can buildself sufficiency an d self reliance without doing it inreactionary way. I've always been a pragmatist. Groups arerunning into a lot of problems with th e homeless, withdrugs. You have to address these issues."

The method a group uses to deal with intractableproblems can become th e source of contention. "Thedesire to intervene effectively and help people help eachother can turn into intrusiveness. Groups an d advocateshave to be sensitive to where that line is," adds StephenNorman, a former city official who set up a number ohomeless housing programs an d is now a vice president atth e Corporation for Supportive Housing.

Many advocates draw the line a long way away frompeople's personal lives, preferring to fight neighborhoodproblems instead. "I don't think any organization ha s th eright to impose their view of how other people should ac

on tenants in housing they manage," states AnnePasmanick, the director of th e School for Housing

CITY UMITS/MA Y 1992/17

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

18/28

Organizers .In off-the-record interviews , many people involved in

community-based housing echo Pasmanick, bu t onlyAbdur Rahman Farrakhan , th e director of the OceanhillBrownsville Tenant s Association, is willing to speak publicl y against his peers. "To me , it's just a bunch of crap."

he says. "They have an addendum to their lease whichsays you have to do this or that. Well , you can't say yo uhave a participatory democracy an d then design something an d give it to people. I find that offensive."

The range of opinion reflects a raging debate about thecauses and cures for poverty . Like th e great divide between church and state in American society, there's asimilar barrier between those wh o think th e governmentcreates poverty an d those wh o blame poor people themselves. Yolanda Rivera tries to straddle these points of

view , calling for better schools an d government-subsidized housing in th e South Bronx-but also demandingchanges in th e behavior of her staff an d the tenants inBanana Kelly buildings.

Is sh e blaming th e victim, imposing social control? No,sh e replies adamantly. "I look at this as what naturally

occurs among neighbors an d people who care for eachother. And frankly, I do n 't care what outsiders thinkofit."Bu t when push comes to shove, Rivera concedes that a

community development group can't take th e place of thepolice, the court system and the laws that are meant toreflect th e values of society. Referring to the lease rider ,sh e says, "A contract is a contract. We believe it could beenforceable." Then sh e backs up: "Have we ever litigatedit? No. Is it enforced? We 've never tried to enforce i t -except among each other." D

Controversial ContractBehind many of the changes at Banana Kelly are

concepts promoted by th e National Center for HousingManagement (NCHM), a nonprof it group based in Washington, D.C. Th e National Center is currently workingwith about 30 community-based housing groups inNew York as part of a strife-ridden training programfunded by Banker's Trust an d th e Uris Foundation.

The two funders feared that community groups taking control of newly-renovated city buildings filledwith formerly homeless families might become overwhelmed by their ne w responsibilities. They decidedto look for a consultant that could provide the community groups with training sessions an d seminars inproperty management, organizational development andways to combine social services with property management.

After setting up a steering committee that includedcity officials and community advocates, they awardeda two-year, $200,000 training contract to NCHM.

Established in 1972 through a decree by then-President Richard Nixon, NCHM is best known for trainingand certifying housing managers. But they also have aunique approach to working with tenants.

Instead of blaming th e government, the system or"the man," NCHM expects poor people to examinetheir ow n values an d behavior, according to th eorganization' s vice president, Aureo Cardona. Cardonaused to be president of the South Bronx CommunityManagement Corporation, which has ties to povertyczar Ramon Velez .

"We want masses of people to be thinking aboutwhere they are in life an d ho w they can immediatelybetter their conditions," Cardona says.

In New York, th e NCHM training contract withcommunity groups ha d a haphazard start. Some groupsdidn't take part in training sessions because they didn'tlike th e sound of NCHM's philosophy. There were alsoother problems.

Nonetheless, Gary Hattem, a vice pres iden t at Banker'sTrust who used to ru n th e St. Nicholas NeighborhoodPreservation Corporation in Brooklyn, defen ds th e de

cision to hire NCHM, while also admitting that he ha s

1 8 / M AY 1992/CITY UMITS

some qualms about the group ."All of us who selected NCHM ha d a lot of problems

with their rhetoric," he adds. "It can be a bi t ESTish an dsound canned, but we ha d respect for th e groups-wefigured they would filter out what they didn't buy into ,an d a lot of groups di d find something of benefit."

Jeanette Puryear, th e director of th e Mid-Bronx Senior Citizens Council, is serving as th e president of thecoalition of groups taking part in th e NCHM training."There's a range of opinion-most groups who attended th e NCHM training found it very useful," sh esays, noting that her ow n staff found value in th e nutsan d bolts advice on property management.

However, sh e adds that some groups stayed awayfrom the training sessions because they didn't like th esound of NCHM's "tenant empowerment" strategy."That's th e piece a lot of us have mixed feelings about,"she says. "But there 's a real issue here about howtenants can take responsibility for their environmentan d th e surrounding community-some of it ha s tocome from within ."

One of th e groups that pulled out of the trainingsessions was the Oceanhill Brownsville Tenants Association. "I think it 's a loose class in self actualization,"says Abdur Rahman Farrakhan, th e group's director."It's juvenile an d condescending."

Frances Barrett, th e director of the Community Resources Exchange (CRE), which provides fundraisingan d organization-building advice for nonprofits, ha sanother perspective . Her organization was a to p contender for th e training contract that NCHM won. At on epoint, th e funders considered splitting the contractbetween CRE an d NCHM, bu t Barrett says that after sh etalked with NCHM staff members she decided she'drather compete with them than work side-by-side .Their philosophies mixed like oil an d water.

"I see the housing problems of New York havingmore to do with th e vacancy rate than values clarification," she says. "The bottom line is: whose values? I tseems to me you risk exploiting a person's need forhousing-holding up your help as hostage for a defined

lifestyle. It just feels wrong."Lisa Glazer

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

19/28

CITY LIMITSe i t v L i m i r s e i t v L i m i r s

Starting SmallFighting Incin&ralion (rom the

School.

and Public Housing Protects or Fort Greene. Brooklyn

Winner of the

- . - -,.M l l _ . . . . _ _e i r v L i m i r s

BURIED ALIVE:Ne w York's Garbage

1992 New York City Audubon Society Media Awardfor Distinguished Service to the Environmental Cause

CITY LIMITS covers the urban environment like no other New York magazine becausein this town the environment is more than parks, birds and trees. I t is illegal garbagedumping, lead paint poisoning, overburdened emergency rooms and crack vials in thestreet. We uncover the hazards, and we spotlight grassroots groups turning their n e i g h ~borhoods around. We've won six journalism awards for our reporting. Isn't it time yousubscribed?

, - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1YES! Start my subscription to CITY LIMITS.

D $20/one year (10 issues)D $30/two years

Business/Govemment/LibrariesD $35/one year D $50/two years

D Payment enclosed. Add one issueto my subscription-free!

Name _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __

Addres s _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

City State Zip __L _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _~

CITY LIMITS, 40 Prince Street, New York, NY 10012

CITY UMITS/MA Y 1992/11

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, May 1992 Issue

20/28

Bare Necessities

Aircus for the rich, a workhouse for the

poor-that's New York City , where one