Buro Happold Patterns - Issue 15 2010 Small

Transcript of Buro Happold Patterns - Issue 15 2010 Small

the magazine of buro happold issue 15 autumn/Winter 2010

big art

profile

education

The role of engineers in the world’s most ambitious artworks

Phillip Blond: Mr Big Society turns to the future of cities

How the Middle East is transforming its children’s schools

resourcesThe world’s supply of oil is running out. What do we do now?

www.burohappold.com

In association with

Buro Happold

Patterns

Patterns Issue 15 Autum

n/Winter 2010

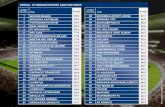

JEDDAH

TORONTO

SAN FRANCISCO

EDINBURGHGLASGOW

LEEDSMANCHESTER

BIRMINGHAM

BELFASTBATH

LONDONMUNICH

CAIROKUWAIT

RIYADH

COPENHAGENBERLIN

WARSAWMOSCOW

HONG KONGPUNE

DUBAIMUMBAI

ABU DHABI

LOS ANGELESCHICAGO

BOSTONNEW YORK

Contacts

Global Sector Directors

Civic and Local Government Stephen JollyE: [email protected]

Education Mike EntwisleE: [email protected]

Rail Damien KerkhofE: [email protected]

Sport, Leisure and Event Paul WestburyE: [email protected]

Commercial Property: Nick NelsonE: [email protected]

Healthcare Andy ParkerE: [email protected]

Urban Development and Planning Andrew ComerE: [email protected]

Aviation Neil SquibbsE: [email protected]

Cultural Stephen JollyE: [email protected]

Hospitality Paul RogersE: [email protected]

Scientific Andy ParkerE: [email protected]

Middle EastOffice 515, 5th Floor Al Akariyah 2, Olaya Street PO Box 34183 Riyadh 11468 Saudi Arabia T: +966 (0) 1 419 1992

North America West Suite B,9601 Jefferson Boulevard,Culver City, CA 90232 USAT: +1 310 945 4800

North Europe and ScandinaviaFour Winds, Pacific Quay Glasgow G51 1DY UK T: +44 (0)141 419 3000

India Suite 1, Vatika Business Centre TechPark 1, Yerwada Pune 411006 India T: +91-20-40111150

UK17 Newman Street London W1T 1PD UK T: +44 (0)20 7927 9700

North America East 100 Broadway,New York, NY 10005 USAT: +1 212 334 2025

Central EuropePfalzburger Straße 43-44 10717 Berlin GermanyT: +49 (0) 30 860 906-0

Asia Pacific 3507-09 Hopewell Centre 183 Queen’s Road East, Wanchai Hong Kong T: +852 3658 9608

Buro HappoldBuildings Environment and Infrastructure Consulting

From our very first project we have used our intricate knowledge of the industry to push the boundaries and achieve more. It is this commitment that sets us apart, that adds value, that makes us award winning. We apply the same level of complex thought and specialist expertise to every project we work on.

Our people define what we do. We invest in them in the same way that they invest in us; by providing opportunities to learn, to research, to develop. Our way of design is to draw on every talent, to consider every approach, to strive to progress; but to always use our proven methodologies to get results.

After 35 years in the industry we have never lost our desire to be challenged, our passion for creativity and our sense of adventure. We know that building a place with a future involves creating strong communities that enable economies to thrive, engaging with society’s big issues and enriching people’s lives.

We are at the forefront of low energy design: we deliver projects that have less carbon emissions and are more sustainable, we deliver projects that do not cost the earth. Our expert teams of engineers and consultants know how to get the best out of the world’s precious land and resources to provide for a growing population. We are leading the way in shaping a new future.

Autumn / Winter 2010 38 39

Comment

Gavin Thompson, CEO, Buro Happold

his founding partners from an early stage in their careers. The instruction was simple: be curious! Explore, think deeply, but also think broadly. Seek to understand the skills and challenges of those with whom we chose to work – our clients, city governors, architects, builders, project managers and so on. It is not our deep technical knowledge in any one or any group of areas that makes us unique; it is how we span these areas to create solutions which have lasting value. We should not be afraid to ask ‘why is this so?’ but must do so from a firm foundation of knowledge and appreciation.

In this edition of Patterns you will see us lifting the curtain on our world, sharing those themes that have aroused our curiosity. From looking at the concept of ‘Big Society’ and the role the built environment might play in it, to considering the great challenges facing society through peak oil, we have deliberately sought breadth. Looking not just at our technical skills but at how an individual experiences a new building, how art and the work of the structur-al engineer fuse together, and indeed how art influences the lives of people outside their work at Buro Happold.

I hope you enjoy this small window on our world.

uriosity may have ultimately got the better of the cat but it is the life blood of Buro Happold.

Patterns has been the name of our technical publication since the early days of the practice. We wanted to continue this tradition of sharing our deep technical knowledge, but also want to share our curiosity within the built environment – looking for patterns, if you will, and exploring how the gaps that exist in

current thinking can be bridged to yield better solutions to the future challenges that will face society.

Most of the current owners of Buro Happold were coached by Ted Happold and

C

Be curious! Explore, think deeply, but also think broadly

Patterns

Contents

02Autumn / Winter 2010 03

04 WelcomePatterns is about our enthusiasms, your projects, and our exciting collaborations

06 News Drive for better buildings, Rensselaer award, Trada chair, Green Building success

08 Profile Radical thinker Phillip Blond on his philosophy, the Big City and what the future holds

12 Education Middle Eastern states are investing heavily in schools in a bid to boost home-grown talent

16 Big pictureA glimpse at what lies behind the classroom features that help inspire the pupils

18 Resources We are nearing the point where oil reserves start to decline. The implications are huge

22 Technology From desert condensation and embodied carbon to sculptures and technical design tools

26 Engineering art Mike Cook adores big art and the engineering that makes it work. How do the two relate?

30 A day in the lifeThree men, three continents, one project, 24 hours: it’s all in a day’s work for the Zero-E team

32 Sport Ireland fan Sean Mackey gives an insider’s impassioned view of the Aviva Stadium

36 Secret lives Zac Braun is a structural engineer by day, but he’s also forging a career as an artist

38 About Buro Happold Vital information about this worldwide practice, and contacts for key sectors

In association with

Patterns is a twice-yearly publication produced by The Architects’ Journal, part of EMAP Inform, for Buro Happold. Magazine director: Tom Foulkes, global head of marketing, Buro Happold; magazine coordinator: Rachel Davies, senior marketing co-ordinator; editor: Ruth Slavid; design: Brad Yendle, Tom Carpenter;

sub-editor: Alysoun Coles; CEO, EMAP Inform: Natasha Christie-Miller.Patterns is printed by Headley Brothers on FSC-certified paper. ©Buro Happold

To contact anybody at Buro Happold email first name.last name@BuroHappold.

Cover image: Voussoir Cloud, Los Angeles

p.26

p.18

p.08

p.12

atterns, the name of this new magazine, may ring a few bells. It is a title that Buro Happold has used before.

Buro Happold, founded by the late and great engineer Ted Happold in 1976, built its strength on imaginative and innovative structural engineering, much of it in col-laboration with the world’s best architects. Projects such as the lightweight tented enclo-sure at Munich Aviary and the Al Marzook Centre for Islamic Medicine in Kuwait soon showed the quality of work that the practice could produce.

When the first issue of Patterns was published in 1987, it reflected the company as it was then. Packed with information, and densely written, it was a celebration and explanation of some of the most interest-ing engineering going on in the world. Features included a construction analysis of unusual structures, a piece on developments in lightweight engineering, and an article on working in Iraq, which described two projects in detail, but explained that they were in abeyance, due to the war. This was written by Rod Macdonald, now chairman of the practice.

Patterns was hugely informative, so much so that you felt that if you read it thoroughly, you could, whatever your back-

ground, probably have a good go at design-ing those buildings yourself. But in fact to fully appreciate it – to really see the genius that was in the detail – you needed a techni-cal background. Buro Happold produced the magazine very much for its peers in the design community.

A lot has changed since then. Ted Hap-pold sadly died in 1996, but the practice’s strength and ingenuity in structural engi-neering has continued to grow, as evidenced by such projects as the Millennium Dome (now the O2) centre, the Khan Shatyr Entertainment centre, Kazakhstan and the Aviva Stadium in Ireland. The fact that the architects for these projects were, respec-tively, Richard Rogers, Norman Foster and Populous, shows the practice still works with the very best architects.

But now Buro Happold is much more than just a structural engineer. It expanded first into other engineering disciplines, such as mechanical and electrical, facade, and fire engineering. Now the practice is involved in every aspect of the built environment, offer-ing clients masterplanning, environmental impact assessment, and advice on land purchase and planning. Everything from the initial conceptual stages of a project, when the client may not even be sure that there is a project, through to specialist engineering

P

Buro Happold is redrawing its engagement with its most exciting partners – you. By Tom Foulkes

Welcome

Patterns

services, is offered by Buro Happold.And the practice has also expanded

geographically. When the first issue of Pat-terns was published, Buro Happold had four offices, in Bath, Kuwait, Riyadh and Hong Kong. Now our website lists 24, and with a business this size there are new offices open-ing all the time across the world.

As the company has changed, so has the way in which it wants to communicate. It has much to say, and it wants to say it to a growing number of people. The new Patterns is not about specialists talking to specialists. Instead, it is much more outward looking. It has been devised to talk to people who are working with Buro Happold or who may wish to work with them in the future. These people are skilled and knowledgeable, and interested in the built environment, but they are not necessarily trained as engineers, and may not want to be bombarded with techni-cal wonders.

So this magazine is very much about what interests the fascinating, diverse and multi-talented people at Buro Happold, and what they would like to offer to the equally fascinating people with whom they work.

This issue covers a huge range of issues, from peak oil to education in the Middle East; from a new approach to social science and how it may affect public services all over

the world to how art and engineering relate to one another and where the boundaries blur; but it also covers some of Buro Hap-pold’s newest thinking – not quite in the same detail as the Patterns of old but if it interests you and you want to know more, then you can contact the people involved. If there’s one thing I’ve learnt while co-ordinating this magazine it is that the people at Buro Happold love to share their knowl-edge, and do it with such passion and energy that even if the acronyms and terminology go in one ear and out the other it’s still a great conversation and you will feel richer for it.

And yet even covering such ground as it does, this new Patterns is still not a representative snapshot of the work of Buro Happold. Indeed it isn’t even all about Buro Happold. But it does embody the practice’s spirit and enthusiasms. One of the greatest of those enthusiasms is for you, its exist-ing and potential collaborators and clients, and it is in this spirit that Buro Happold is delighted to offer you the first of the new incarnation of Patterns.

Welcome

Tom Foulkes is global head of marketing at BH. To contact Tom email [email protected]

04Autumn / Winter 2010 05

Pa

ùl

Riv

eR

a/a

Rc

hP

ho

to

News

Macdonald heads industry drive for better buildings

Recognition for NY’s Rensselaer...

... and for Saudi’s ancient capital

Patterns

Rod Macdonald, chairman of Buro Hap-pold, has initiated a process which is leading to a UK parliamentary inquiry into the poor design and quality of the products available for the construction of our built environ-ment. Macdonald, who also won the 2010 ACE Engineering Ambassador of the Year Award, is working with APDIG (the Associ-ate Parliamentary Design and Innovation Group) and other bodies to find ways to produce cheaper, better quality buildings and improved components. Leading the first steering group meeting in July, he said the construction industry has fallen behind others in adapting to the modern world and appropriation of new technology, and that the industry should strive to deliver unique buildings from highly developed compo-nents that continually evolve and improve.

The Curtis R. Priem Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, has won an Excellence in Structural Engineering Award from the National Council of Struc-tural Engineers Associations. The building, which contains a 1,200-seat concert hall within a red cedar hull, was designed by architect Grimshaw with Buro Happold.

Happold Consulting played a pivotal role in the addition in July this year of the first Saudi capital, Al-Turaif, to the Unesco register of World Heritage sites. Happold Consulting is working in the region on the Arririyadh Historic District Comprehensive Development Plan, which includes the area of the historic town, and encouraged its cli-ent’s critical support for the application.

This image Rensselaer’s award-winning arts centre

Below Al-Turaif, Saudi’s historic capital

Cook’s first as he chairs timber body

Eureka! Westbury is in the top 100

New Mumbai office opens

06Autumn / Winter 2010 07

Mike Cook, Buro Happold’s director of buildings, has been named chair of the UK’s Timber Research and Development Associa-tion, the first chair in its 76 year history to come from outside the timber industry. The structural engineer said, ‘Our goal is for timber to be the natural first choice material for construction and for TRADA to be at the centre of its development.’

BH’s European MD Paul Westbury is in The Times’ Eureka 100 guide to ‘the most impor-tant contemporary figures in British science’. His entry reads: ‘The roof structure of the Mil-lennium Dome weighs less than the air held within [it]. The Emirates Stadium houses 100 flights of stairs…What do the award-winning buildings have in common? Paul Westbury, the structural engineer who led their design teams.’

Buro Happold opened its first permanent office in Mumbai, India, on 1 November. It is at No. 201, Delta Building, Hiranandani Gardens, Powai, Mumbai – 400 076.

Green team builds in New OrleansThe RAMPed UP team, a collaboration between Buro Happold and Rogers Marvel Architects, is one of four national finalists in the US Green Building Council’s Natural Tal-ent Design Competition. The team comprises young professionals – Daniel Bersohn, Tim Hanna, Rossella Nicolin, Lauren Page and Ir-mak Turan from the BH New York office, and four from RMA. They were asked to design an 800ft2 LEED Platinum home in New Orleans that is affordable ($100k), hurricane and flood resistant, and handicap accessible. The final-ists’ homes will be graded on energy efficiency, water reuse and indoor air quality, and be built in New Orleans. The grand prize will be awarded at Greenbuild 2011 next October.

For the latest BH news go to www.buro-happold.com or twitter.com/burohappold

oliticians are so busy with tactics they often have little time to spend on strategy, so it is not unusual to see them turn to others to do their

thinking for them. When David Cameron talked about the Big Society, both before and after his election as UK prime minister in May this year, he was adopting ideas from philosopher, theologian and political thinker Phillip Blond. And when Blond launched his think tank ResPublica in November 2009, Cameron spoke at the opening.

But Blond insists he is politically inde-pendent. He says his ideas, though grounded in his experience in England, have a wider application. ‘Britain is the home of policy innovation and radicalism,’ he says. ‘Europe often tracks Britain on policy.’

Britain is important because, he believes,

it has had frequent revolutions in political thinking. Since World War II we have had the welfare state, Thatcherism, new Labour and now the Big Society. ‘It is just the latest idea,’ Blond says, but he is convinced it is the most important. ‘The state and the market have failed, and we need a new mechanism to deliver public policy, that of civic association’. He says, ‘Civic society can create a market and a state that works better for people. We want to back the excluded middle – the life on our streets and in our neighbourhoods, as the site and source of power and prosperity. A society of civic association is better able to express individual and collective needs.’

This needs an enabling physical environ-ment as well as the political structures. Blond is very taken with the work of Canadian writer Doug Saunders, whose book Arrival

Cities looked at the areas of cities where immi-grants from overseas or the country pitch up.

‘There are some poor areas of the city where poverty traps you,’ Blond says, ‘and some where it integrates you into society and accelerates you out of disadvantage.’ This is particularly true in rapidly urbanising coun-tries. ‘Few have thought about urban transi-tion zones,’ he says, ‘and what is required for them to be successful.’

Looking at how cities can succeed is one of the aims of a project Blond is undertak-ing with Buro Happold, to produce a report next year called Big City. It will look at cities that work and those that don’t, and attempt to explain how both existing and new cities can become fit for a big society. Blond will not say which cities he sees as successful, but he has a clear idea of which buildings work.

P

Patterns

Phillip Blond is translating his Big Society to the Big City. He talked to Ruth Slavid.

Profile

08Autumn / Winter 2010 09

Ph

ot

og

ra

Ph

y b

y r

ich

ar

d N

ich

ols

oN

Patterns

He praises the Great Court at the British Museum, being particularly keen on what some might see as a failure in that it inter-rupts direct circulation through the building. ‘I like the disruption that causes the flow to go back on itself, creating a social space,’ he says. In Britain, he adds, ‘we generally think of spaces as something that we walk through, but in classical European cities people like to parade in front of one another. They are not segmented by age or occupation. Most Brit-ish towns are age and time restricted. After a certain time of day too many of them are populated solely by alcohol and bad food.’

Blond likes hybrid buildings that join old and new, like Tate Modern, and the Bund in Shanghai, with its mix of older buildings and new arrivals. He is less enamoured of many entirely new buildings. ‘They all look the

Profile

with them because of the importance of what they do and a strong parallel between our ap-proaches. We have much to learn from them.’

If there seems a mismatch between the global reach of Buro Happold and this newly established think tank in central London, that may not last long. Already ResPublica has gone from just two people to 20 full time staff, plus 10 to 15 part-timers. Blond has been approached to set up offices in London, Berlin and Paris, and an organisation wants to endow an office in Washington. He has strong links in eastern Europe, and his was the only think tank on a recent government mission to China. ‘The rather optimistic vision I have is to become the first global be-spoke policy think tank,’ he says. ‘We want to be an international platform for best practice.’

Blond’s path to this point started with a

same in so many ways,’ he says. ‘There is noth-ing symbolic or metaphysical about them.’

He has clear ideas about housing, praising Penoyre & Prasad’s scheme for north London’s orthodox Jewish community. Providing ac-commodation for three generations, ‘it reflects the way we need to go’. And he loves Erno Goldfinger’s ‘very beautiful’ Trellick Tower in London, which ‘went from vilified to adored, through being understood soft culture’.

Blond describes cities as the hardware that has to accommodate the ‘software’ of everyday civic life. It is Buro Happold’s expertise in providing that hardware makes him keen to work with the practice. ‘It is one of the most innovative and profound world firms,’ he says. ‘It goes from building the entirely new in China to renovating broken parts of the city in Detroit. We are very interested in working

‘BH is one of the most innovative and profound world firms. We have much to learn from them’

‘There are some areas of the city where poverty traps you and some where it integrates you’

10Autumn / Winter 2010 11

Even a man of Blond’s undoubted energy is fully occupied with a growing think tank, a not insubstantial media career, with inspiring the UK government and playing a growing role on the world stage. Asked why he has done so well so fast, he says, ‘Sometimes the concepts you have capture the moment; it’s a combination of good ideas, strong vision and a lot of luck. We are a small organisation but have increasing national and interna-tional traction. Our ideas are good, and we have some brilliant people. It’s a very exciting organisation to run’.

degree in politics and philosophy ‘because I thought that none of the problems of politics could be solved without philosophy’. After his MA, a spell in local government and a fellowship in New York, he studied for a PhD in theology because ‘I thought that none of the problems of philosophy could be solved without theology. The ultimate questions are ineluctably tied into some theological ac-count of the nature of existence. Why is there something rather than nothing, why is there a good? These are fundamental questions.’

His PhD was on the beatific vision of St Thomas Aquinas and he hopes one day to turn the 200,000 words still waiting to be written up into a book on vision and belief. ‘I am very interested in art and sculpture and in the metaphysics of vision,’ he says.

But at the moment this will have to wait.

‘The rather optimistic vision I have is to become the first global bespoke policy think tank’

Phillip Blond’s CV

1966 Born in Liverpool1984-87 BA in politics and philosophy, University of Hull1987-1988 MA in continental philosophy, University of Warwick1988-1991 Policy officer in finance department, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London1991-1995 Prize fellowship in philosophy, New School for Social Research, New York1996-1999 PhD in theology, University of Cambridge1999-2000 Lecturer in theology, Exeter University2000-2009 Senior lecturer in theology, University of CumbriaJanuary 09 Joins Demos think tankNovember 09 Sets up ResPublica2010 Publishes with Faber and Faber ‘Red Tory – How left and right have broken Britain and how we can fix it’.

To find out more about our consulting services go to www.happoldconsulting.com. To find out more about ResPublica go to www.respublica.org.uk/

hen Tony Blair was cam-paigning to become British prime minister in 1996, he famously made the phrase

‘education, education, education’ one of his mantras. It was one on which his government followed through, although not without criti-cism. Its biggest project was Building Schools for the Future, which aimed to transform every secondary school in the country.

Austerity and a new government have ended that programme. But the countries of the Middle East, acting independently but with much synergy, have taken up the baton and are investing heavily in their education.

‘The Middle East is a growing market for education,’ says Mukund Patel, business development director for contractor Sammon Group UK, the largest provider of educa-

tion buildings in the Abu Dhabi region. ‘The population is expanding, and they want to modernise education.’

These countries realise that if they want to compete in a global market and not rely on importing talent, they need appropriate education. Their large expatriate populations mean they have a lot of private schools offer-ing international curricula. Less than 20% of the UAE’s 6 million population are Emirati nationals, and Saudi Arabia has 26% expatri-ates. Schools exist, and are being built, that offer British, American and Indian curricula, and also the International Baccalaureate.

A 2008 World Bank report found the quality of education in Arab states falling behind other parts of the world and needed urgent reform. The lowest literacy rates were in Djibouti, Yemen, Morocco and Iraq. Although considerable investment since the 1980s has improved standards, this came from a very low base.

Students were also tested by the report and their performance was found to be below those in East Asia, with even wealthy countries like Kuwait and Saudi Arabia scor-ing below the international average.

The report highlighted growing depend-ence on private education, which it says will contribute to inequality. In 2003, when the study was done, 71.8 per cent of primary ed-ucation in Qatar came from private schools. In Lebanon the figure was 64.7 per cent and

W

Patterns

It’s the states of the Middle East that are really building schools for the future. By Alice Knight.

Education

12Autumn / Winter 2010 13

in UAE 57.6 per cent, and the figures had generally risen in the last 10-20 years.

While governments are investing in state-run schools, cash is also being put into private schools as many of these are not up to scratch either. To complicate matters, many countries also invest in private schools, though few go as far as Qatar which is nearing the end of a programme called Education for a New Era, the primary purpose of which is to turn all state schools into independent schools.

Demand for schools can be huge. Sam-mon Group’s Patel was previously based in the UAE and says, ‘There is a large demand for good and affordable schools. Some have a waiting list of 600.’ The number of students in private education in Abu Dhabi, of whom 69 per cent are expatriates, rises by 5 per cent a year. And the facilities are not necessarily good. Abu Dhabi has 185 private schools and inspections for Abu Dhabi Education Council recently found 68 per cent were unsatisfactory in terms of efficiency and teaching standards.

In a speech earlier this year, Dr Rafik Makki, executive director at Adec, the office of planning and strategic affairs, said, ‘We found that nine out of 10 of our students are not ready for higher education, and require a bridging programme.’ So new schools, better facilities and a new approach to education are needed. For instance, two primary schools in Abu Dhabi are to start using a Finnish approach to education in an attempt to raise

Left Children at the Sultan’s school, Muscat, OmanFar left GEMS Dubai Modern High School was built by Sammon Contracting in just eight months

Joc

he

n T

ac

k

Patterns

tion contracts announced in July by Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Finance, worth a total of $16 billion, 287 were for the establishment of schools, colleges and training centres.

Robert Okpala, a Buro Happold group director based in Dubai, says that when designing sustainable schools in the Middle East, water usage is as important as energy. And while air conditioning may be unavoida-ble in summer, there is ‘increasing interest in opening the building for natural ventilation in winter. There’s concern about air quality, and an interest in using outdoor spaces with shading’. He sees particular opportunities in Qatar, which is spending a lot on its schools. For instance, it recently let two contracts for seven schools, due to complete in 2012, at a total value of $100 million.

With its ambition to improve both the delivery of its education and the buildings in which this is delivered, the Middle East is an exciting area in which to work.

Education

standards – Finland is acknowledged to have the best-educated population in the world.

In terms of physical fabric, six schools re-cently had to be closed because of health and safety risks. The government has also made physical education mandatory, in response to concerns about childhood obesity.

In July, Musanada, the organisation set up to deliver projects for the Abu Dhabi government (the name means ‘to support’) announced a plan to build 15 new schools. This is just the first phase in a 10-year plan to build 100 schools in total. In September Abu

Dhabi enshrined in law a scheme called Esti-dama (the Arabic name for sustainability), a green rating scheme which Buro Happold helped to set up and which is similar to the American LEED or UK BREEAM. All buildings in certain categories must comply and the aim is to reduce energy use by 40 per cent, and water use by 26 per cent. It rates buildings in terms of ‘pearls’ and the new schools will have to achieve three pearls from a potential five.

The government is also undertaking a major refurbishment programme which in-volves everything from increasing the size and number of classrooms to ensuring there are adequate facilities for pupils with disabilities.

In terms of private schools, Patel says, ‘Private operators are trying to meet demand.’ They are struggling to find funding for major projects but pressure is acute in Abu Dhabi, Qatar and Egypt, with its growing middle

class and interest in a US curriculum. Patel says that schools built for expatriates

are very like those of the academy programme in the UK. They typically have imposing entrances and impressive atria.

Every curriculum, he says, makes different demands on a building. The International Bac-calaureate has a lot of project-based work, which needs large spaces. American schools emphasise sports (‘their facilities are incredible’); Indian ones tend to classes of 30 rather than 24, and a more traditional academic curriculum.

In general though, the facilities in the UK’s

academy schools, such as design technology and food technology areas, will be increasingly wanted in the expatriate schools. In Kuwait, the government is trying to foster e-learning, which will have a big impact on the fabric of schools.

Saudi Arabia is another country spend-ing a lot on schools. In 2009 King Abdullah announced a major investment in education, saying, ‘We need more efforts to strengthen Saudi Arabia’s position by building brains and investing in humans.’ He pledged SR9 billion for educational development, and set aside money specifically to build new schools. A total of SR4.2 billion (US$1.1 billion) was allocated ‘to improve the educational environ-ment’. The country has said it wants to follow models from Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Japan, China, New Zealand, Finland, France, Ireland, Britain, Canada and the US.

There is further evidence of this commit-ment. Of 1,018 development and construc-

Below Brislington Enterprise College in England is the kind of facility many Middle East schools would like

In Saudi Arabia, SR4.2 billion was allocated ‘to improve the educational environment’

Bu

ro

Ha

pp

old

/Hu

ft

on

& C

ro

w

Buro Happold’s education sector leader is Mike Entwisle. To contact Mike email [email protected]

14Autumn / Winter 2010 15

Buro Happold

This project is an innovative private university with an emphasis on business, science, engineering and medicine. The development is located in the grounds of the late King Faisalbin Abdul Aziz’s palace in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funded by private donations, the project is being developed on a fourphase basis. The 220,000m2 campus comprises buildings for the Science, Business, Engineering and Medical departments, along with a conferencing library, student centres, sports facilities and below ground car parking.

Buro Happold has been appointed in a joint-venture format with Hijas Kasturi Associates of Malaysia for the engineering design and project management services.

Phases 1 and 2 are expected to be completed in late 2007.

Key project information

Client Al Faisal UniversityArchitect Hijas KasturiDates Ongoing

Services provided by Buro Happold

Structural engineering, building services engineering, geotechnical engineering and civil engineering

Al Faisal UniversityRiyadh, KSA

Below left Al Faisal University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia is under constructionBelow right Masterplan for Kuwait University Al-ShadadiyahCentre Al Faisal University in Riyadh, Saudi ArabiaBottom Construction work at Princess Noura University for Women in Saudi Arabia

Higher education

The Middle East is also active at tertiary level, attracting students and educationalists from overseas to create the best possible learning environment. The highest-profile operation is the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology, which will open in 2011, in the new sustainable city of Masdar in Abu Dhabi. It has strong links with Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US.

Meanwhile, in Dubai, Buro Hap-pold developed systems for Kings College to reduce energy, use water more efficiently and improve usabil-ity for occupants. Dubai Internation-al Academic City is home to out-posts of 28 institutions, including the UK’s University of Exeter, the University of Phoenix in America, India’s Mahatma Gandhi University and the University of Woollogong in Australia. In total there are 16,000

students and it has further plans for expansion. Dubai’s Knowledge Vil-lage has a particular emphasis on training in human resources, while the emirate Ras Al Khaimah has created a free zone to attract around five UK and American universities to set up campuses.

In Riyadh, Saudi Arabia is building the Princess Noura Bint Abdul- Rahman University for Women, at a cost of $11.5 billion. When it is complete in 2012, the university will cater for 26,000 students, and will include a 700-bed teaching hospital.

Even more ambitious is Qatar’s Education City, masterplanned by Japan’s Arata Isozaki, and with a central library by Rem Koolhaas, which opens in 2012. It will have the Middle East’s largest convention centre, designed by Yamasaki Archi-tects, and is due to open this year.

Patterns

03

01

02

04

Bu

ro

Ha

pp

old

/da

nie

l H

op

kin

so

n

Autumn / Winter 2010 16 17

Big pictureCastle Rock School

Buro Happold finished work on Castle Rock School, Leicester, in 2006, as part of the Building Schools for the Future programme. It was designed to provide out-standing teaching facilities with a strong focus on sustainability. Ofsted’s June 2008 report praises Castle Rock as a ‘good school with some outstanding features’.

01. Lots of natural light and fresh air help improve pupils’ concentration.02. Solar treated glass and controlla-ble blinds boost comfort by reducing the impact of the sun.03. Glulam timber frame structure used one-sixth the energy of similar strength steel, and saved on budget.04. Passive infra red controls turn off lights in empty classrooms, helping cut electricity costs by up to 25%.05. Sustainable features, includ-ing rainwater harvesting and solar roof panels, have won the school a BREEAM ‘Very Good’ rating.06. The windows’ very low U-valueof 1.54W/m2K keeps the classroom warm in winter while the high per-forming filters help it stay cool in summer.07. Secure cycle storage for 10% of pupils means parents need not clock-watch at going home time.08. The average pencil can write 45,000 words. For this pupil it’s writ-ing a story that will get a B+.

05

07

06

08

elatively recently the buzz words ‘climate change’ and ‘carbon footprint’ have been joined by ‘peak oil’ as governments and

energy suppliers grapple with the realisation that our supplies of the fuel that has driven so much of our development are not in� nite – and that the end is in sight. � is will a� ect every aspect of our lives – including the built environment.

What is peak oil? Peak oil is the point at which the rate of oil extraction reaches a peak and starts to decline. It is an area shrouded in controversy, and the methods of calculating when peak oil will occur are complex and open to debate. Some think we have already reached that point, others that it is yet to come. A study by the UK Energy Research Centre in Octo-ber 2009, which brought together the � nd-ings of more than 500 pieces of independent research, concluded that peak oil would occur sometime between 2009 and 2030.

But whether it has already happened or is still some time o� , decline is inevitable. While the experts argue about the details, the rest of us need to face reality. Once the peak has passed, even though there will still be ‘a lot’ of oil available, the world will be very di� erent. Oil will rapidly become scarce (for which the synonyms are ‘expensive’ and ‘un-reliable’) because, without drastic changes,

demand is set to keep growing. In 2009, the International Energy Agen-

cy’s (IEA) ‘Reference Scenario’ projected an increase in global oil demand of nearly 40% between 2005 and 2030 (an average annual growth rate of 1.3%). � is took account of measures adopted by governments up to mid 2006, and assumed that there was no further change in behaviour.

According to BP, world primary energy consumption – including oil, natural gas, coal, nuclear energy, and hydroelectricity – fell by 1.1% in 2009, the � rst decline since 1982. � is was largely attributable to the re-cession, and cannot be expected to continue.

As oil is going to be extracted from in-creasingly di� cult – and therefore expensive – sources, we can expect to start feeling the e� ects of shortage earlier than the more opti-mistic � gures may suggest. And the resources are not spread evenly around the world. As we pass peak oil, we will all depend increas-ingly on oil from the Middle East. � e International Energy Agency has warned that an oil ‘crunch’ could happen as early as 2013.

Once oil reserves start to decline, we will enter an unstable period. Rather than simply rising slowly prices will � uctuate, and so will availability, bringing enormous political pressures to bear. Clearly, the better equipped the world’s economies are to replace oil, the more stable the situation will be.

� ere is another fossil fuel available. Coal

R

Patterns

As peak oil looms and reserves fall back we need to fi nd a new way to live. By Alasdair Young.

Resources

Projected peak of world oil production(million b/d)

2030

2050

1900

1950

1970

1990

2010

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

2% demand growth

1% demand growth

Zero demand growth

SOURCE: DOUGLAS-WESTWOOD LTD

12Autumn / Winter 2010 13

Ge

tt

y im

aG

es

Patterns

is abundant, particularly in Russia and Chi-na. � is would be an easy solution – if there were no such thing as climate change. But unfortunately, coal’s greenhouse gas emis-sions are far worse than those of oil, so such a switch would be disastrous. At a BH partners’ meeting in 2005, Jeremy Leggett, founder of independent solar company Solarcentury, warned, ‘Renewable energy and fuel use, alongside energy e� ciency, will increasingly substitute for oil and gas, growing explosively whatever happens. However, amid the ruins of the old energy modus operandi many will try to turn to coal. � is means that the extent to which renewable energy grows explosively instead of coal expansion, rather than alongside it, will determine whether economies and ecosystems can survive the global warming threat.’

Energy supply after peak oil?At the end of 2009, two American research scientists, Mark Z Jacobson and Mark A Delucchi, published a paper in Scienti� c American, arguing that the world could meet all its energy needs by 2030 from renew-able energy. � ey deliberately limited themselves to technologies that are already available, rather than relying on new, as yet undiscovered, technologies. � ey work on the assumption that there is a current maximum annual power demand of 12.5 trillion TW, and the US Energy Information Administration estimates that this will grow to 16.5 TW by 2030, taking into account rising population and living standards. � is is based on the assumption that domestic cooking and most heating will become electric, and that vehicles will be powered by rechargeable fuel cells. Renewable energy is more e� cient than fossil fuels, so demand would be ‘only’ 11.5 TW.

Resources

Limitations would come from potential shortages of some specialist materials, most particularly lithium for fuel cell batteries.

But in general terms, the authors calculate not only that this power could be produced, but that it would be available at costs equivalent to the price of the fossil fuels we use today.

� is may be a very optimistic forecast. But major resources are certainly available. � e UK, for instance, is very well placed to generate electricity from wind power. A 2005 report by the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford found that the UK had abundant reliable wind that blew at the right time. � ere is more wind in winter, when electricity demand is higher, and it blows more strongly during the day than at night. In winter, what the authors de� ne as ‘low wind speeds’ would a� ect the whole country only occasionally – there would only be one hour in every � ve years when they would cover 90% of it.

Far more than this, they say, is read-ily accessible, with water potentially able to supply 2 TW, wind 40-85 TW and solar 580 TW. � ey envisage the world’s energy being produced in the following way:

Water 1.1 TW (9% of supply) 490,000 tidal turbines – 1 MW – <1% in place 5,350 geothermal plants – 100 MW – 2% in place900 hydroelectric plants – 1,300 MW – 70% in place3,800,000 wind turbines – 5 MW – 1% in place720,000 wave converters – 0.75 MW – <1% in place 1,700,000,000 rooftop photovoltaic power plants –.0003 MW – <1% in place49,000 concentrated solar power plants – 300 MW – <1% in place40,00 00 photovoltaic power plants – 300MW – <1% in place

The growing gap Oil discovery and production

2050

2060

2000

2010

2020

2030

2040

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Past discovery

Future discovery

Production

Past discovery based on ExxonMobil (2002) Revisions backdated

SOURCE: PEAKOIL.IE

20Autumn / Winter 2010 21

tries are committing to improve the environ-mental performance of their buildings. In the UK, for instance, there is a commitment to make all new domestic buildings zero-carbon by 2016, and all non-domestic buildings by 2019. At the same time the UK, like most other developed countries, is having to work out how to bring its vast stock of existing buildings up to current standards or better.

As buildings start to reduce the fossil fuel that they consume in operation, so the embodied energy within them will gain importance. So attention will move to the recycling – and recyclability – of materials.

� e bigger question is how these devel-opments will a� ect our cities. In some ways this could be very positive. For instance, if all transport is electrically driven, it will be much quieter and fume free. So the only inhibition

Large-scale solar power also has great potential in sunny parts of the world. Large plants have already been built, such as the Olmedilla photovoltaic plant in Spain, gener-ating 60MW. Even more interesting are con-centrated solar power plants, some of which have been built in southern Europe, the US and Africa. � ese use either mirrors to focus the sun’s energy on a single point, or energy generated by the upward movement of hot air. Deserts are particularly appropriate places for solar power plants, with uninterrupted sunshine and relatively low land values.

� e wedges solutionIn 2004, two researchers at Princeton Univer-sity, S Pacala and R Socolow, came up with the concept of ‘wedges’ to reduce the growth in CO2 emissions. As the graph shows, each wedge represented an activity that could re-duce carbon emissions and so help to stabilise the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere over the next 50 years. � ey calculated that there were 15 technologies or actions that could do this. � ese ranged from making buildings more e� cient, to capturing CO2 at plants converting coal to synthetic fuels, to the use of ‘conservation tillage’ in agriculture. � e pair proposed that it should be possible to reach the target through seven ‘wedges’ – by scaling up our emissions-reducing e� orts in seven of the 15 activities. Deliberately, none of the techniques they proposed were radical. � e point was that they had done the sums and believed their plan was achievable – but only through a combination of approaches, rather than a single one. Given how often ambitions fall short of targets, this approach could be roughly translated as ‘we need to try hard at everything we can’.

� ere are some obvious ways in which this will a� ect the built environment. Most coun-

Fossil fuel emissions (GtC/y)

2050

2060

2000

2010

2020

2030

2040

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Stabilization triangle

Continued fossil fuel emissions

to having opening windows will be either if they prove not to be the most e� ective way of controlling the environment, or if wind is a problem – most likely in tall buildings.

Transport will drive many of the changes. Electrically-driven vehicles will have a smaller range than existing petrol-� red vehicles. Travel will be expensive, and have to be consid-ered carefully. Both sea and air transport are

pro� igate consumers of fossil fuels. � is will drive us towards more local production and consumption, for both environmental and commercial reasons. Making (and growing) things locally will be far more attractive, with everything from agriculture in cities to a resur-gence of manufacturing a possibility.

Adam Poole, an analyst with Buro Happold, says, ‘People will spend more time where they live. Will you have shared facilities for people to come together and work in one place for other people?’ � e o� ce as we know it, already shrinking as more and more people hot-desk, may become smaller yet. If commut-ing drops right o� , the whole pattern of the use of our cities will change. And as planning and development take a long time, this is an issue, like peak oil, that we should be address-ing not some time in the future, but today.

The International Energy Agency has warned that an oil ‘crunch’ could happen as early as 2013

SOURCE: WWW.SUNHOMEDESIGN.WORDPRESS.COM

Alasdair Young leads BH’s natural resources team and is based in London. To contact Alasdair email [email protected]

here is some fascinating work go-ing on in the Buro Happold offices around the world, developing new technologies and solutions. Here is

just a small sample.

How not to get steamed up in Abu DhabiThe choice of materials for the shimmering perforated dome of Jean Nouvel’s Abu Dhabi Louvre, due for completion in 2014, might seem a simple matter of appearance and costs. But research by Ian Maddocks, a facades en-gineer in the London office of Buro Happold, revealed another important factor – condensa-tion in the vapour-laden desert air. Nowhere else on earth is so much radiant heat energy absorbed by the day and released at night.

The clear sky above the Arabian penin-sula admits large streams of solar energy, which is absorbed on the ground and converted into heat. Some energy is lost to the surroundings, and some is radiated back into space as electromagnetic waves invisible to the eye. The rate of radiative cooling at night can be surprisingly high – in the order of 100W/m2. This is enough to cool exposed surfaces several degrees below ambi-ent temperature (the Persians famously de-veloped an ice-making technique using this natural effect). Condensation soon forms on these cooled surfaces if the air is humid.

The two favoured materials for the dome’s cladding were anodised aluminium and stain-

less steel. One difference between them is their thermal emissivity – the amount of radi-ant energy a surface emits, compared to an ideal black body. Thermal emissivity is high in anodised aluminium; low in stainless steel.

Maddocks’ task was to see what effect the different materials would have, by setting up an experiment on site. He explains: ‘We had to think about the dome as a stack of giant sieves: a huge fractal-like object that might condense thousands of litres of vapour from the pregnant air at any one time. Not to mention the capture of all that airborne salt splashed up by the caustic Gulf Sea.’ The quantities are surprising. Some 2g of sea salt will fall every day onto every square metre of exposed horizontal area. Over the 250,00m2 that would equal half a ton of salt per night.

At night, anodised aluminium will cool more rapidly than stainless steel, because it will emit more radiant heat into the clear, thin desert atmosphere. The difference in night time radiative cooling rates is pro-nounced – in the order of 100 W/m² for anodised aluminium and 30 W/m² for stain-less steel under clear skies. And the more the dome cools, the more likely it is that it will reach the dew point temperature, at which point it turns into a mega condenser, convert-ing surplus energy at the surface into dew.

Maddocks explains, ‘The experiment confirmed the condensation rates for the aluminium that we had predicted earlier,

but hadn’t announced. We couldn’t quite believe the figure of a quarter litre of con-densate for every square metre on a winter night – that is, until we saw it with our own eyes. And the figure for the “low-e” stainless steel, predicted and measured? A tenth of that, if any at all.’

On the first night, Maddocks had another surprise, when there was a sea fog, which typi-cally happens 38 times in the year. ‘It licked every square metre of surface area with the same quarter litre of condensate, regardless of emissivity or orientation,’ he explained. ‘All 250,000 m² of the dome system will engage to produce 60m3 of condensate! We want to avoid the 6m3 trickle of condensate produced by radiative cooling, because it will transport salts and other corrosives from above into nooks and crannies in the lower layers.

‘However, we can’t avoid being drenched by a 60m3 sea-fog deluge. Dealing with that is down to detailing and concourse drainage. Ironically, we think that, unlike the radiative-cooling-induced trickle, the sea-fog-induced deluge will create a useful self-cleaning effect (although we didn’t get a chance to investigate this empirically).’

T

Patterns

BH at work: condensation in the desert, embodied carbon, a design tool, and a sculptural net.

Technology

All enquiries about the Louvre Abu Dhabi should go to Tim Page, project director in Bath. To contact Tim email [email protected]

22Autumn / Winter 2010 23

BH at work: condensation in the desert, embodied carbon, a design tool, and a sculptural net.

Right The complex tracery of the dome makes it particularly prone to condensation Below Jean Nouvel designed the Louvre Abu Dhabi with a dome that is reminiscent of Arabic geometric forms

At

eli

er

Je

An

no

uv

el

Patterns

Knitting patternsKnots and knitting are not the most common concerns of engineering practices, but for Buro Happold’s New York office they formed the basis of one of the firm’s most fascinat-ing – and demanding – projects. The practice worked with the artist Janet Echelman to create a hanging sculpture that forms the centrepiece of a new civic space in Phoenix, Arizona.

Called Her Secret is Patience, and inspired by the pattern of desert winds, the installation is a huge, conical, multi-coloured mesh structure, suspended from a metal ring slung between three slender steel posts, each 75cm in diameter. A full 29m across at its widest point, and about 30m high at its high-est, it comes down to just under 12m above the ground, and sways about in the breeze, like some enormous translucent creature in the sea. The artist’s conception is magnificent – but it couldn’t have happened without the engineers who helped to make it.

Echelman has worked with meshes before, but this was her largest and most ambitious commission yet. As with some of her earlier projects, she collaborated with the New York architect Philip Speranza to develop the form, and Buro Happold’s involvement at this stage was to advise on what was physi-cally possible. Eventually they settled on a kind of inverted cone, supported on two suspended rings of very different sizes.

Ian Keough, an associate with Buro Hap-pold who originally trained as an architect, explains how the practice turned the concept into something that could be produced.

‘We had to write a fair amount of soft-ware,’ he says. ‘We called it Netbuilder. We took the original models and broke them down into their constituent pieces and put them into Tensyl, a piece of Buro Happold

Technology

software that is usually used for the design of membrane structures. This examined how the structure would hang under its own weight and made sure it would not be over-stressed.’

Next the software had to create a ‘looming diagram’. The structure was to be made on a giant loom that is usually used to make fishing nets, and the curved profile would be created by the number and spacing of the knots on each line on the loom.

The installation has two sculptural nets, an inner and an outer, the latter of a much wider weave and less immediately visible. The inner net was knotted automatically on the loom, although some manufacturing techniques had to be tweaked. Normally the manufacturer will tension the completed net by pulling it to ensure the polyester knots cannot slip, and will then boil it to ‘fix’ it. Here the tensions were uneven, so the knots had to be tensioned by hand, and the net could not be boiled in the usual way because the colours would have run. So instead, a fine polyurethane coating was applied to hold the knots in place.

The sculptural net had to be knotted entirely by hand. A company called Diamond Knots undertook the task. ‘They are real pros,’ says Keough. ‘It only took them a couple of days to knot the whole net.’

Once both nets were knotted and had been fixed together and then attached to the rings, all that remained was to hoist them in the air and leave them to float about in the breeze. The sculpture, despite its enormous size, looks as insubstantial as the artist intend-ed. There is little hint of the hard work and clever calculations that went into making it.

Analysis of the net

Ian Keough is an associate based in Los Angeles. To contact Ian email [email protected]

24Autumn / Winter 2010 25

Measuring embodied carbon As buildings become ‘greener’ in operation the embodied carbon in their physical fabric becomes increasingly important. Conven-tional thinking has been that the amount of energy a building consumes in its lifetime, and hence the carbon dioxide generated if that energy comes from conventional sources, far outweighs the CO2 ‘embedded’ through the production, manufacture, trans-port and assembly of the components.

But as the amount of CO2 produced in a building’s operation falls, the importance of the structure’s embodied energy increases. Now Ed Sauven, a structural engineer in the Buro Happold London o� ce, has developed a structures carbon tool that helps engineers to make a rapid assessment of the embodied carbon in di� erent structural options.

� e company has now embedded this tool in its BIM (building information modelling) software, so that the potential embodied car-bon in the structure can be considered along-side other elements as the design develops.

What next? Buro Happold is in the early stages of developing a technique called whole-life carbon management, which would bring together whole-life models of a building, along with a version of the struc-tures carbon tool. � is should allow people to make an informed judgement about not only the greenest option for a building, but also to assess just how green that option as a whole will be. We are moving beyond the stage in which good intentions are enough in sustainable design. We need hard facts, and this work aims to produce them.

Embodied Carbon of Structural Frame

9%5%

61%

25%

Steel Frame

Concrete Frame

Floor Slabs

Sub structure

Taking the HEAT out of designSophisticated methods of calculating the be-haviour of buildings are suitable for the later stages of a design, but what is needed early on is quick and reasonably accurate responses to design changes. � is is what Alan Shepherd, who runs the San Francisco o� ce of Buro Happold, has come up with.

‘You need something you can use in real time to make decisions,’ the developer of HEAT (holistic energy analysis tool) explains. It concentrates on orientation, plan depth and � oor-to-ceiling height which Shepherd says are the most important factors in the thermal behaviour of a building. And it ignores detailed geometry and thermal mass, which complicate the calculations, and have a lesser e� ect.

Shepherd has based his tool on Cam-bridge University’s LT method, which divides buildings into passive and non-passive zones. Passive zones have access to natural light and can be naturally ventilated, while non-passive interior spaces need mechanical ventilation.

Because it is quick and easy to use, HEAT allows the design team to look at alternative scenarios and gauge the size of the e� ects of making changes. It produces simple outputs in Excel spreadsheets and by batch run-ning multiple iterations of the model it can produce graphs showing the best orientation, percentage of glass, plan depth and depth of shading overhang.

By the time that the design reaches the stage at which the more sophisticated, and time-consuming, analyses are needed to pro-duce accurate results, the whole team should be con� dent they have the best solution.

Below Janet Echelman’s Her Secret is Patience, engineered by Buro Happold

Embodied carbon of structural frame

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

3029282726252423222120

Steel frame

25%

9%5%

61%

Floor slabs

Concrete frame

Sub structure

00.20.40.60.81.01.21.41.61.8

North – overhang depth versus % glass

JAN

ET

EC

HE

LMA

N

Alan Shepherd is an associate principal based in San Francisco. To contact Alan email [email protected]

Ed Sauven is a structural engineer based in London. To contact Ed email [email protected]

Engineering artt

he

be

an

by

at

eli

er

On

e a

nd

Ch

ris

hO

rn

ze

e-J

On

es

. ph

Ot

O: V

iew

piC

tu

re

s

have a passion for ‘big art’. Art you can walk round; walk through; even sit in. Not buildings or bridges that have a brief to fulfil, but art – its sole purpose

to draw out human response and add to our experience of what the world is.

When I inhabit a Serra, walk round a Kapoor or sit in a Turrell I thank the un-known minds and hands needed to achieve this object. And then I start to wonder about the engineering of art – that interplay of artistic imagination with technical realisation.

Sometimes, though not often enough, I have found myself talking to artists about a new project, perhaps a competition for a work or a new commission that needs to be developed. And I realise that I’m always won-dering about my role. As an engineer I can have big impact or small impact – no impact isn’t an option. But what is the right balance?

Big impact happens where the artist is stepping into the unknown. Engineering experience can help guide the artist away from the unrealisable towards the achievable. It may be about materials that won’t do what they want, or ideas that would end up in a ditch because people might die. Engineering is about how to make things – taking materi-als and building up an object from them with the right form, the right colour and a chance to last a lifetime. And the experienced engineer should understand the cost and affordability of things where that is an issue.

Size does matter in this case. Big works are usually harder to make and they can engage people in potentially dangerous ways. There may be manufacturing complexity in small works but as you get bigger the con-struction logistics start to become important. So when working small the unique hand of the artist is likely to be more easily engaged and apparent.

In the relationship between architect and engineer there is, I like to think, a clear common goal – that of the functioning of the building for the benefit of the client. This helps to stabilise and ground the dialogue between engineer and architect and legitimise the influence that technology can and must have. In the relationship with the artist such common ground is less apparent and the work’s purpose is legitimately more personal to the artist.

For me the question is – do constraints hinder or help? Do they simply take away the freedom of the artist to express what he wants, or do they become an essential part of the work?

And how much influence should technol-ogy have on the artistic creation? How much should concerns about what can be done influence the creative urge to do something different? Shouldn’t art force us into new territory, force us to find new ways to make things; new ways to make things safe; new ways to experience life? So might not an

I

26 27

When it comes to big art are we facilitators, inhibitors or part of the project, asks Mike Cook?

Patterns

garden (according to Anthony Caro, one of his assistants) and the technical constraints and opportunities of the making process became a major aspect of his creativity.

Anish Kapoor has achieved some as-tounding works. ‘The Bean’ in Chicago is a tour de force of precision and perfection, and was achieved through the critical engagement of many engineers and craftsmen. His steel and membrane installation in Tate Modern relied on engineering to ensure the transfor-mation of material into art. I am fascinated by the question of how much his art was influenced by these collaborations, and the

Engineering art

engineer, technologist or fabricator be in grave danger of imposing constraints; no longer a facilitator but an inhibitor?

This is the challenge to the engineering of art: always to search for the technological route forward, always to encourage a new path; to allow technology to be a facilitator and to find new solutions where none yet exist.

But there is another way too, where the technology is the art – or at least forms a fundamental part of the story. In this case it becomes a different level of collaboration be-tween artist and technologist. A game of ping pong (or should I say wiff waff?) between the ‘what if ’ and the ‘how could’, where you can-not predict who will bring what to the table. It’s a jam session of ideas and exploration. But this makes a different kind of art – a techno-logically inspired or at least steered art. And the question for me is – who is the artist?

So I have been looking at examples of col-laborations between artist and technologist to see what might come from different types of collaborative relationship. Do these relation-ships change the art or does the art simply allow the relationships?

How did Christo and Jeanne-Claude make their art? It challenged the possible – that seems to have been the point. In that way it challenged people’s perceptions of their world. So it was shaped heavily by what was possible – or more to the point by what their collaborators said was possible. But art needs leadership so Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s role was to lead; to start things, to make choices, and to keep it moving.

How did Henry Moore achieve his grand art works? Certainly through engagement in the technology of casting and finishing that involved ‘outsourcing’ a lot of the work. At the start he used a makeshift foundry in the

Previous page Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate in Chicago, popularly known as ‘The Bean’Below Voussoir Cloud was a gallery installation, produced by a collaboration between Buro Happold and Iwamoto Scott

impact of his collaborators’ views on the pos-sible and the impossible – the engineering of the art? To what extent did that collaboration affect the end product?

The question remains – ‘How far should the influence of the engineer go?’ The simple answer is that it is different in every case, and this is not a simple cop-out. We all know that every building is different, but artworks, and crucially artists, are probably more different to each other than are buildings and architects.

I have already pondered on the differences in the type of work that the artist is creating, but there are also differences in the experience

Jud

so

n T

er

ry

28Autumn / Winter 2010 29

Case studyCalifornia College of Art

A bland student lounge at the California College of Art has been transformed by a giant hanging sculpture, a perforated white HDPE creation which drapes across a sculptural beam and with two ‘valve’ openings at the top – hence its name, Aortic Art.

Architect Mark Donohue of Visual Research Office (VRO) won a competition for the piece, and then brought his ideas to Buro Happold for refinement. ‘He had an idea,’ says Ron Elad, an architect in Buro Happold’s Los Angeles office. ‘He wanted an object with three holes in it. The shape of the surface was aesthetically driven, but some of the curves couldn’t support them-selves. We had discussions about how his design intent could work.’

The structure had to be entirely self supporting but the material had no inherent stiffness.

‘We played around with the open-ings, and their orientation,’ Elad explains. He used CATIA design software to move things around, and then: ‘Once we found some-thing we were comfortable with, we started analysing it.’

Some of this work was very sophisticated but, to help Donohue understand why it was important to work with the concept of ‘minimal surface’, Elad set up a demonstra-tion using two rings and soap bub-bles. The collaboration was, says Elad, positive on both sides, and he is delighted that ‘it doesn’t look that different from the original model’.

Below Buro Happold’s analysis of Aortic ArcBottom Aortic Arc in situ

of the artist. Crucially, have they created any work of this kind of scale before? Do they understand what is and isn’t possible? Do they understand what the cost implications are?

An experienced artist may just want the engineer to help them to realise their vision; but someone younger and less experienced may need a great deal of help and guidance. Inevitably that may mean we are setting limits and boundaries to what the artist can do. But that may be no bad thing. Just like architects, many artists do their best work in response to limitations.

Working with artists, we should be pre-

pared for the unexpected – for great sophis-tication or, dare I say it, great ignorance; for demands we have never met before, and for them to change their minds during the con-struction process in ways that no experienced architect could expect to do.

It can be difficult and frustrating, but also hugely stimulating and rewarding. My col-league Victor Frutos-Juarez, who has recently been working with several young artists in London, told me ‘I get a lot of satisfaction out of it. Art is more personal. You can do many buildings but they all have the same con-straints – because buildings have to perform.

Every piece of art is different. And once the concept has been developed, we can some-times find ourselves leading the process.’

I have always said that good architecture needs good engineers. Once art reaches a certain scale, it is equally true that good art also needs good engineers. What can be more rewarding than engineering in the service of a passion for big art?

Rie

n v

an

Rij

th

ov

en

Mike Cook is director for buildings at Buro Happold. To contact Mike email [email protected]

ero-E was a pilot project carried out by Buro Happold in collabo-ration with architect Woods Bagot to model a large-scale sustainable

scheme that would not merely reduce the energy of new development but look at ways to heal a damaged and fractured city. A truly international project, it involved several Buro Happold offices, and took as its subject an industrial site in Chongqing, China.

In three months of working the teams carried out detailed research work to produce a ‘holistic resource system’ that integrated photovoltaics, solar thermal panels, absorption chillers, biogas fuel cells and an anaerobic waste digester. There was com-plex calculation involved, and parametric modelling, led by Alan Shepherd in San Francisco. The project culminated in a two-day workshop that looked at everything from climate change mitigation targets for China to agreeing a process for market testing, communication and collaboration. Sustainability director Dan Phillips, based in London, worked closely on the presentation with Jeff Till from Woods Bagot. Other main contributors to the project included Laura Wingert and Kurt Komrous in LA and Pablo Izquerdo in Bath.

Weaving this project in among all the others that occupied the team members, and operating across widely different time zones, is all in a day’s work.

Z

Patterns

A day in the life of the far-flung Zero-E team. By Ruth Slavid.

3am San Francisco / 11am London / 7pm Hong Kong

Dan Phillips meets aviation director Alan Regan and Azhar, a director at Conran and Partners, to discuss a competition for a new airport in the Baltic.

5.30am San Francisco / 1.30pm London / 9.30pm Hong Kong

Associate director Alan Shepherd is woken by a scrub jay screeching in his back yard.

6am San Francisco / 2pm London / 10pm Hong Kong Dan Philips discusses the practice’s approach to sustainable healthcare with BH’s business strategist Adam Poole.

8.45am San Francisco / 4.45pm London / 11.45pm Hong Kong Alan Shepherd arrives at Woods Bagot after a crowded ride on the Bay Area Rapid Transit, which reminds him of the joys of the Lon-don Tube. He meets Wood Bagot’s technical director, sustainability director and CEO to discuss a new office development in Beijing. He receives an update on Zero-E meetings in China that will be attended by David Littler, group director of Buro Happold Hong Kong.

11am San Francisco / 7pm London / 2am Hong Kong Dan Phillips cycles to a talk on sustainability organised by the Guardian newspaper.

1pm San Francisco / 9pm London / 3am Hong Kong Alan Shepherd goes to architect HOK’s offices to discuss a zero-carbon project in Portland, Oregon.

4pm San Francisco / midnight London / 7am Hong Kong

Alan Shepherd arrives at his office, at the foot of the Bay Bridge. He works on the de-velopment of a TRNSYS model for a hybrid geothermal system design for the Bull Creek Residence in Austin, Texas.

4.30pm San Francisco / 0.30am London / 7.30am Hong Kong David Littler arrives at his office in Hong Kong. He can take one of several buses from his 11th floor apartment, and relishes not owning a car. The temperature outside is above 30ºC but he puts on a jumper because of the fierce air conditioning.

Worldwide

Alan ShepherdSan Francisco, USA

GM

T -

8 h

oU

rS

30Autumn / Winter 2010 31

6.20pm San Francisco / 2.20am London / 9.20am Hong Kong Alan Shepherd leaves his office and detours to the Oakland Boxing Gym for a workout.

8.05pm San Francisco/ 4.05am London/ 11.05am Hong Kong David Littler rings Alan Shepherd at home to discuss the Holistic Energy Assessment Tool (HEAT) he developed for the Zero-E project and David’s upcoming presentations in China with Jeff Till.

David Littler spends the rest of the day preparing for the presentations. Some of these will be given at meetings with Chinese devel-opers and the Chinese government – arranged through his China-based colleague Yin Liu. Buro Happold CEO Gavin Thompson will accompany Littler on what will be his first trip to China.

Midnight San Francisco / 8am London / 3pm Hong Kong David Littler sends draft Zero-E material to the London office.

1am San Francisco / 9am London / 4pm Hong Kong Dan Phillips arrives at work by bicycle. Barbara in the canteen makes him toast with marmalade and peanut butter. He takes this to a quiet room to review what David has sent him. He likes what he sees.

3am San Francisco / 11am London / 6pm Hong Kong David Littler is on his way home after a meeting on the MTR, Hong Kong’s metro. His Blackberry (phones work underground in HK) details the next Zero-E gathering in London in a couple of weeks, to give the project another push forward.

Dan Phillips London, UK

Lo

nD

on

Gr

ee

nW

ich

Me

An

TiM

e

GM

T +

7 h

oU

rs

GM

T +

7 h

oU

rs

The subject chongqing, china

David Littler hong Kong

To contact Alan, Dan or David email [email protected]

upporting Ireland has been a constant feature of my adult life – a pilgrimage, if you like. Growing up in an Irish family in London,

there was never any doubt as to our national allegiance, and I’ve been travelling to cheer on the Boys in Green since 1972.

Dublin’s Lansdowne Road stadium was dear to me, because of its history and charm and its wonderful, convivial atmosphere. Now the site has a new spiritual home for Irish foot-ball and rugby, and it’s spectacular. I visited the Aviva Stadium for the first time in August, for the opening international against Argen-tina, and it’s a huge improvement everywhere that the rickety old ground was lacking.

I’m proud to say I was a co-founder of the Republic of Ireland Soccer Supporters Club (London). Around 1972 I started going with an old friend to as many games as I could afford. My parents are from Pallasgreen in County Limerick; as a child I didn’t know what summer was like in London, because I was always at my grandfather’s farm.

As a young man, I’d get to every com-petitive game at home and would hand-pick two or three away games in every qualifying campaign. My wife Carmel, who is originally from Clogher in County Tyrone, joined the club just before we married in 1989, and our daughter Roisin became a member in 1991 when she was 30 days old. She went to her first international in Denmark at the age of

two, and at four was pictured with Jack Charl-ton, the manager who took us to two World Cups. She’s been a loyal supporter ever since.

The key point in the formation of the club came in 1984, when Gerry Lappin put a note in the Irish Post saying he’d seen lads go-ing to games, particularly away games, again and again. Since air travel was expensive in those days, he suggested we form a club and travel together, and perhaps get a cheaper rate from the airline. So we met up at the Prince of Wales’ Feathers in Warren Street, off Tot-tenham Court Road, and the club was born.

Following the team was always fun, even though in the early days we weren’t very good. In the seventies, before Jack came on board, I was going to away games and singing that we were the greatest team ever, and almost always losing. But the craic was tremendous.

The old Lansdowne Road had unique features. I’d seen various stadia around the world – some worse and some a lot better. The view of the DART railway line and the rest of Dublin that you had from the upper stand was fantastic, and it’s in such a lovely, leafy, semi-suburban setting.

We’d catch the DART from Tara Street in central Dublin and then wait at the level crossing. You always had to stop there to let trains pass and a huge crowd would gather, but it wasn’t like your average football crowd – at Ireland games, everyone is in tremen-dous form so it’s a very benign and friendly

S

Patterns

Sean Mackey, a 57-year-old Republic of Ireland football fan, talks to Jonathan Coates.

Sport

32Autumn / Winter 2010 33

Left Mackey’s ticket for the opening game at the new Aviva stadium in August Centre Mackey and his daughter Roisin take the escalator up from the DART railway to the new stadium Right Comfortable at last – for the first time Mackey has a seat that can accommodate his 6ft 2in frame

Pa

ul

Mo

ha

n /

SP

or

tS

fil

e.c

oM

Patterns

SportC

hr

is G

as

Co

iGn

e

34Autumn / Winter 2010 35

atmosphere, and children aren’t intimidated.I was on the DART the first time I saw