B*m of du and et - collections. Canada

Transcript of B*m of du and et - collections. Canada

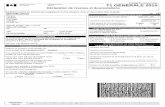

National Library B*m of Canada Bibliothèque nationale du Canada

Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K I A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada

Your hk, Votre réMrence

Our fiik, Noire rdfdrence

The author has granted a non- exclusive licence allowing the National Library of Canada to reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 copies of this thesis in microfom, paper or electronic formats.

L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive permettant à la Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de cette thèse sous la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique.

The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

. . ........ List of Figures ............................... ..,........................o.o..o....s..........ooo..s...o vil ... List of Tables .................................................................................................. VIII

........................................................... Glossary ............................. ix

................................................................................. .......... Acknowledgments .. xi . . ......................................................................... ..................... Abstract .......... XII

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1 . 1 Methodology of this Study ....................................................................... 2

1 . 2 Scope of the Chapters .............................................................................. 2

2.0 CHAPTER

2.1 Defining

W O : Nova Scotia Cultural Tourism: Marketing the "Exotic"

Tourism ..................................................................................... 4

2.2 The

2.3 The

2.4 The

2.5 The

Rise of Cultural Tourism ................................................................... 4

Nova Scotia Experience .................................................................... 7

Tourism Nova Scotia Market Assessment: Structure and Function . . . .8

Results of the Study .......................................................................... 9

2.6 Identifjing the Characteristics of Demand for Nova Scotia

3.0 CHAPTER THFtEE: Planning Tbeory Through a Historical Context and its Relation to Cultural Tourism

3.1 Introduction ........................................................................................... 21

...................... 3.2 Sustainable Development and Cultural Tourism Planning.. 2 1

3.3 Places, Images, and Marketing. .............................................................. 25

.............................................. 3.5 Ethnicity and the Marketability of Culture 28

................................... 3 . 6 Concepts of Authenticity and its Role in Tourism 29

.................................................. 3 . 7 Acculturation and Community Tourisrn 31

3.8 Market-Incentive Planning and Efforts to lntegrate Planning with Business .............................................................................................................. 34

................................. 3 . 9 Planners and the Socio-Cultural Issues of Tounsm 36

4.0 CHAPTER FOUR: A Case Study in Developing a Cultural Tourism Authenticity Guideline: Lancaster County. Pennsylvania

........................................................................................... 4.1 Introduction 41

...................................... 4.2 Background on lancaster County, Pennsylvania 41

................... 4.3 The Lancaster County Heritage Tourism Initiative (LCHTI) 4 2

................................................................... 4.4 The Make-up of the LCHTI 4 3

4.5 The Role of the 'tocal Resident". "Visiter". and "Visitor Domain" within ............................................................................................ the LCHTI 4 5

..................................................... 4.6 The Heritage Authenticity Guidelines 46

................................................................. 4.7 An Assessrnent of the LCHTI 49

5.0 CHAPTER F M : Defining and Assessing Community Heritage in Nova Scotia

........................................................................................... 5.1 Introduction 52

.............................................................. 5.2 The Acadien French Study Site 53

..................... ...................... 5.2.1 The Municipal District of Argyle ... 53

.................................................... 5.2.2 The Municipal District of Clare 53

.................. 5.2.3 A Review of the Clare / Argyle Region Questionnaire 54

...... 5.2.4 Responses to the Questionnaire: Defining Cultural and Heritage ......................... .............................. Features .. 55

5.2.5 Interviews and Questionnaires Comments on Authenticity and ........ .............................. Cultural Tourism in the Clare / Argyle Region 57

........................................................................ 5.3 The Lunenburg Germans 62

....................................................................... 5.3.1 Lunenburg County 62

5.3.2 The Lunenburg County Questionnaire Results ............................ 62

.......................... 5.3.3 A Review of the Responses to the Questionnaire 63

5.3.4 Interview and Questionnaire Comments on Authenticity and Cultural ...................................................... Tourisrn in Lunenburg County 65

5.4 The Black Comunity: North and East Preston . Observations and Interviews .

........................................................ 5.5 Concluding Remarks and Observations 72

6.0 CHAPTER SM: Conclusions and Recommendations Regarding the Planning and Design of a Heritage Authenticity Guideline for Nova Scotia

Introduction ............................................................................................. 74

6.2 Putting the Proposals within Context of the Provincial Tourisrn Strategy ...... 76

6.3 The Provincial Proposds for a Cultural Tourism Authenticity Guideline ....... 79

..................................................................... 6.4 The Municipal Level Proposais 80

.................................................................................... 6.5 Concluding Remarks 81

8.0 APPENDICES 8.1 Appendix One: Census Data on Ethnic Origin .................................. 89

8.2 Appendix Two: Questionnaires and Results ....................................... 94

LIST OF FIGURES

Number Page

3.1 Diagram displaying operation of "place-images" in motivating behavior 27

3.2 Types of "Touristic" Situations 30

4.1 The LCHTI syrnbol used to indicate an authentic tour& site, event, or service 5 1

5.1 "What makes your community unique.. .?" (Clare 1 Argyle) 60

5.2 Rated Response to the level of Quality / Authenticity / and Business Support 61

5.3 "What makes your community unique.. .?" (Lunenburg County) 69

5.4 Rated Response to the level of Quality / Authenticity / and business Support 70

Num ber

LIST OF TABLES

Page

2.1 Origin of Cultural Tourists

2.2 Education of Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists

2.3 Income of Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists

2.4 Reason of Travel for Culturd and Non-Cultural Tourists

2.5 Extension of Stay between Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists

2.6 Reasons for Traveling to Nova Scotia

2.7 Method of Transportation for Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists

2.8 Spending Cornparisons between Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists

2.9 Activities of Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists

2.10 Cornparison of Physical Activity between Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists

2.1 1 Prior Visits of Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists

2.12 Likelihood Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists will Travel Elsewhere in Atlantic Canada

5.1 Frequency of Qudity / Authenticity / 'Business Help' in Tourism Products in the Clare / Argyle Region 56

5.2 Frequency of Quality / Authenticity / 'Business Help' in Tourism Products in

Lunenburg County 65

. S .

Vlll

GLOSSARY

Authenticity : Of undisputed ongin; genuine.

Authentic Resource: A site, service, or event which reflects a community's heritage or

culture, A resource shows evidence of authenticity through the survival of features which

existed dunng its penod of significance, and through its association with historic events,

persons, architectural or engineering design, or technology.

Authentic Interpretation: The conveyance of information about a community's heritage

or culture through an accurate, objective portrayal of people, sites, places, or events.

Acculturation: Adapt to or adopt another culture.

Community: All the people living in a specific locality. A specific locality, including its

inhabitants.

Culture: The customs, civilizat ion, and achievement s of a particular time or people.

Cultural Integrity: The honest interpretation or conveyance of culture to an observer or

visitor.

Cultural Tourism: Visits by persons fiom outside the host community rnotivated wholly

or in part by interest in the historical, artistic, scientific, or lifestyleheritage offerings of a

community, region, group, or institution.

Heritage: A nation's historic buildings, monuments, countryside, etc., especially when

regarded as worthy of preservation.

LCHTI : Lancaster County Heritage Tourism Initiative

Market-Incentive Planning: Planning for site development that utilizes strategic building

projects and marketing to create a "climate of enterprise" that will encourage private

participation and investment .

Place-Images: Term used to define the rigorous selection of specific images from the

many characteristics of a location to help 'commodifL' it as part of a marketing strategy.

Post-Modernism: Denoting a movement reacting against modem tendencies, especially

by drawing attention to former conventions.

Social Carrying-Capacity: The point in the growth of tourism where local residents

perceive on balance an unacceptable level of social detractors from tourism development.

Sustainable Development: Positive socio-economic change that does not undermine the

ecological and social systems upon which communities and society are dependent.

UNESCO: United Nations Educational. Scientific and Cultural Organization.

ACKNO WLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to thank the following people who helped in the fomulation, research,

and s u p e ~ s i o n of this study: Prof Dimitri Procos of DalTech; Mr. Kim McNutt and Ms.

Darlene MacDonald of the Ministry of Economic Development and Tourkm and my wife,

Ms. Tracy Fleming. Their thoughts, editorial cornments and guidance through the duration

of this study are much appreciated.

I would also like to thank Mr. Bill Plaskett and Mr. Peter Haughn for providing invaluable

information over the course of my research on the communities of Lunenburg. I am also

indebted to Mr. Robert French of the Black Cultural Centre; Mr. And Mrs. Matthew and

Carolyn Thomas of Black Heritage Tours of Preston; and Mr. Scott Standish of the

Lancaster County Planning Department for their help in understanding the issues of the

Black community and in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Tdy these people deserve a great deal of praise for their time, patience and expertise.

Again, Thank You! !

ABSTRACT

This research involved the collection and evaluation of survey data which was used to

identi9 and consider "authentic" cultural tourism resources in a sample of rural Nova

Scotia comrnunities. As part of the research, a database of "place images" fiom

comrnunities with distinct cultural groups and levels of tourism activity were collected.

This database was used as a tolls to identify local perceptions of cultural authenticity and

potential cornmunity resources not fiilly developed for cultural tourism use. With this

information, a nurnber of actions are proposed for municipal and provincial planners in

order to fûrther preserve community heritage for the benefit of the community and the

tourist .

The database was created using a mail survey of community groups and tourism

businesses; personal interviews with municipal officials and members of the communities

surveyed; and literature searches on local history.

The fhdings of the research conclude that more local community participation is needed in

identifjmg authentic place images of the surveyed communities. A combination of changes

to planning legislation and greater levels of community involvement in the planning

process are suggested as possible actions to enhance future cultural tourism potential.

Xll

1 . O INTRODUCTION

While considered cornmonplace by many, tourism still remains a marvel when considering

the level of interaction it encourages around the globe, Changes in the nature of both

business and persona1 lifestyle have allowed people the fieedorn and opportunity to travel

throughout many parts of the world. And as would be expected, the resulting growth in

travel has also raised the level of economic importance for the tounsm industry in general.

In Nova Scotia's case, this raises the importance of providing services, products, and sites

that offer something authentic and unique to the traveler. Determining what is considered

authentic to the province is sornething that carries both economic and social importance.

As communities throughout the province market themselves to more and more demanding

travelers, it remains important to identifi and incorporate truly local concepts of

authenticity into how cultural t o u k m is developed and marketed. There remains a fine

line between staying cornpetitive and providing services and products that tourists will

travel for while still remembering who you are as a community and maintaining the

authentic characteristics of the cornmunity that make many tourists want to visit.

For the professional planner, helping to foster community input in defining and

inventorying culturally unique aspects of the cornmunity (as part of an effort t o preserve

what is found) can complement and be appealing to the cultural tourism market (GuM,

1993). Throughout these actions, the planner c m accomplish these goals through

cooperative paftnerships with tourism developers that balance cultural authenticity and

integrity with entrepreneurial fieedorn.

But despite these efforts, given a choice, many community governments prefer to glaze

over some aspects of local history and culture if it means a more expedient development of

2

the local tourism industry - which would be expected to bring in much needed new jobs.

This approach can rob a community of a sustainable future, especially given the rising

cornpetition for cultural tourism destinations.

1.1 Methodolo- of this Studv

This thesis will present data from surveys and interviews from Lunenburg County; the

municipal districts of Clare and Argyle; and the Preston communities. The survey was

targeted toward tourism operators, artisans, and cornmunity groups. The communities

were chosen based on their distinct cultural makeup and the concentration of tourism

development occumng in each community. The result of the research was a collection of

"Place-Images" of what is considered to be culturally authentic about each community.

This information was compared and contrasted in order to conclude what authentic

cultural tourism needs to entai1 fi-om a community perspective.

Proposais were also made on how the planning profession can enrich the level of cultural

authenticity through alterations in both planning legislation and practice.

1.2 Scope of the Chapters

In order to build a case for the value of focusing on the cultural tourism sector, the first

chapter will look into its "demand side" by exploring the changing tastes of tourists who

travel abroad, both generally and specifically in Atlantic Canada. This will be done in

order to understand the reasons behind the increasing interest in cultural tourisrn as a niche

market of which the province has an opportunity to take advantage.

The second chapter will explore planning and marketing theory and its relation to cultural

tourism development and present an argument as t o why the tourism industry needs

assistance from professional planners to both market and protect authentic culture and

3

heritage for the sake of sustainable tourism. In addition, a review of the background of

professional planning will help present reasons why planners are able to provide a bridge

between the protect and promote culture and heritage.

The third chapter will review a case study that will demonstrate a planning approach

offering some lessons in public-private partnerships in cultural tourism development. The

approach involves a partnership between planners, tourism operators, and cornmunity

groups who worked to design and adrninister a cultural authenticity guideline. The

guideline was developed to help tounsm in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania establish a

level of aut henticity, qualit y and integrity in local tourkm operations.

The fourth chapter presents the results of the questionnaire used in this thesis to identiQ

local perceptions about what constitutes authentic cornrnunity heritage and culture. The

cornmunities chosen for the (which do not include any group considered within the

dominant "British" dernographic group) were defined using federal census data to

determine the location of the survey sites. The selected cornrnunities with high

concentrations' of a specific cultural group within the study site will be contacted through

local business and comrnunity representatives and were provided with a questionnaire. The

questionnaire wiIl ask for definitions of local cultural features and asked to estimate the

level of support in promoting local cultural and heritage features as tourist attractions.

The final chapter describes the unique local concepts and features that help define

authentic aspects of local culture. The chapter concludes with suggested recomrnendations

for changing planning policy and legislation to better ensure protection of authentic local

culture in the face of growing tourhm in the province of Nova Scotia.

1 DcGncd as bcing nny group ovcr 1û% of the popuhtion identifLing thcmsch.cs as a mcmbcr of n pirticutr cihnir group withia the 1991

Fcdcnl crasus tract of N o v i ScotiP.

2.0 Nova Scotia Cultural Tourism: Marketing the 'Exotic'

2.1 Definina Tourism

Tourism cm be defined as a "temporary movement of people to destinations outside their

normal places of work and residence, the activities undertaken dunng their stay in those

destinations, and the facilities created to cater to their needs" (Mathieson and Wall, 1982).

Within tourism, many types of activities and interests are catered to. These types of

activities and interests range from the 'sea and sand' style, to the visiting of friends 'up the

road'. In al1 its forms, tourism has a quality of self-discovery and a sense of awareness of a

new and uncertain environment - a feeling of 'differentness' (Boniface, 1995). These

qualities help make the traveling experience enjoyable and exhilarating to many.

2.2 The Rise of Cultural Tourism

Part of this feeling of 'differentness' includes the experience of discovering and learning

from other cultures - both at home and abroad. In many parts of North America, a

growing segment of tourists are demonstrating a desire to experience first hand the

heritage and culture of the places to which they travel to. Cultural tourism, in tum, is

becoming a more important segment of the tourism industry. It has been reported that the

reasons behind this trend are a reflection of the changing tastes and desires of the tourist

population. In a major study conducted for Tourism Nova Scotia, higher levels of

education, the growing influence of women in travel decision-making, and the

demographic effects of the baby boomer generation (who desire more cultural travei

choices in their lives) appear to account for changes in taste (LORD Inc., 1993). Such

news appears promising when looking specifically at Canada, which has spent considerable

effort in the past prornoting the country to both its own popula.tion, and the World's, as a

mode1 'rnulti-culfural' society .

5

While there is growing interest in the cultural tourism industry, it remains a field that is

still perceived as new and with a short history. The idea of cultural tourism grew out of

the 1969 ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) congress in Oxford,

which declared "cultural tourism, by creating the conditions for a new humanism, must be

one of the fiindamental means, on a universal level, of insuring man's equilibrium and the

e ~ c h m e n t of his personality." (Moulin, 1989). The feeling at the time was that by

encouraging cultural based tourism, more money and support would be generated to help

sustain the health and vitality of the host culture (as interpreted through physical

monuments and historic sites).

By the early 1980s, it was accepted that cultural tourism was distinct fiom other forms of

recreational tourism. Around this time, a desire to broaden the definition provided by

ICOMOS helped spawn Maclntosh's (1980) definition, that saw cultural tourism

"covering ail aspects of travel whereby people learn about each other's ways of life and

thought.. .an important rneans of promoting the development of cultural factors, cultural

attractions, or cultural resources and directed towards conscious contact with cultural

goods." Other researchers, such as John Kelly, added that bbcultural tourism was the

consurnption of cultural experiences (and objects) by individuals who are away fiom their

normal place of habitation". These alterations to the definition saw the marketability of

culture as a great opportunity for both tourism promoters and host communities.

In Canada, a 1993 study on cultural tourism by LORD Cultural Resources mapped out the

parameters of the cultural tourism industry in Ontario. They concluded:

1) Natural Heritage does not fall within the scope of cultural heritage, unless it relates to

human interaction over time.

2) The visitor's desire to take part in a culture experience must be at least partially a

motivation for travel in order w quakfL rs cultual tourism.

6

3) Culture is both "tangible" and "intangible." Exarnples of tangible cultural products

include arts and crafls, gaileries, theaters, and monuments. Exarnples of intangible

cultural products are customs, beliefs, and languages.

4) A cultural tourist may be considered to be anyone Porn mtside the host community

who travels to that cornmunity And who extends histher stay in it for the purpose of

taking part in a cultural activity (ARA / LORD, 1997).

With this information, a market study was perforrned on cultural tourism in Nova Scotia

which defined cultural tourism as "Visits by persorls from orrtszde the host comrnmity

rnotivated wholly ur in part by irlferesf in the historical, artistic, scienti$ic, or

I!festylti heritage qfSerings of a comrntinify, regio~l, grozrp or znstit~~fim. "(ARA / LORD,

1997).

Within the same market study, the Nova Scotia govemrnent elaborated on the elements of

cultural tourism by defining a series of cultural resource components. They included:

The "Anthropologicai" component of cultural tourism - Including characteristics of the

people like customs, 'folkways', dress, language, religion, food, etc.

The "Arts and Culture" component of cultural tourism - Physical expressions, such as

theater, performing arts, visual arts and crafts.

The "Spatial" component of cultural tourism - Urban landscapes, historic places,

coastal and marine areas, rural landscapes, etc.

The 'Wistoric" component of cultural tourism - Sights and activities that focus on a

historic event, its people, and the interaction with the environment (ARA 1 LORD,

1 997)2.

2 Coosidcring thc conternporary nature of this work and ils focus on Novi Scohi, thc definition usrd ip thc ARA / LORD markci study wiU be uscd during thc roursc of this thcsis.

7

When reviewing the literature on the definition of cultural tourism, most authors would

describe cultural tourism as an economic venture where the tourist discovers or learns

some aspect of the host culture by consuming its cultural products. The cultural product,

therefore, is seen as the vehicle by which the tourist judges the quality and persona1

satisfaction of the experience. Given ttiis assumption, it would seem very important to

ensure that the quality and integrity of the product is maintained and that cultural

authenticity is incorporated into how these products are made and designed. Nova Scotia,

like many locations throughout North America, has begun to explore the potential of

tourism to help improve the economic conditions of communities in the province. This

exploration involves understanding the "tastes and desires" of the potential tourist.

To date, the tourism sector in North America has tended to market geographic regions

with diverse tourism interests in mind. This approach rninimizes risk since a variety of

tourism products, including various visitor experiences, c m be developed and used to help

suppon and offset each other. The visitor experiences generally occur at destination sites,

which try to attract a specific tourist market interested in specific features which the

destination site can offer. Tourism products marketed fiom a destination site can be made

up of a locally grown or made item to sel1 or it can be a combination of the physical

makeup of the site and the representative 'atmosphere' that is projected to the tourist. A

destination site's atmosphere can consist of special features such as a geographic location,

setting, development pattern, history, tradition, or Society (GuM, 1 994).

2.3 The Nova Scotia Exverience

Tourism Nova Scotia tends to view the tourism industry as a market-oriented venture.

This is supported by government. Which provides insight through its marketing studies,

which have enabied small business to better understand tourist behavior and anticipate

tourist needs in a more effective way. The marketing process which develops fiom this

insight has been designed to define the most appropriate market 'segments' for the

province to exploit in the cultural tourism industry,

Marketing literature suggests that three basic conditions need to be met in order to define

a market 'segment' on which the province can focus its resources. First, there must be

great enough numbers of interested tounsts in any new segment to warrant special

attention. Second, there must be enough sidarities within any segment in order to define

a theme or linkage. And third, the new segments must be viable (i.e. worthy of attention as

tourism attractions) (Costa and Bamossy, 1995). These conditions indicate that any

segment of the province's culture must possess enough regional continuity to present unity

when marketed; and be feasible fiom an economic standpoint in order to be sustainable for

tourism development. This is the thrust toward which Nova Scotia's cultural tourism

strategy is working.

2.4 The Tourism Nova Scotia Market Assessrnent: Its Structure and Function Recently, a major marketing study was performed for Tourism Nova which assessed the

demand in Canadian, US and international markets for Nova Scotia's cultural tourism

'products' (as they are perceived by tourists to the province). The study also tried to

identify opportunities for developing cultural tourism products in "response to market

demand" other then what was produced at present (ARA / LORD 1997). The work was

conducted by an inter-departmental team that was composed of eight agencies in five

different departments that were involved in some aspect of cultural tourism (ARA /

LORD, 1997). The work focused on:

Economic Development (Tourism, Marketing, Community Econornic Development);

Municipal Affairs (Heritage Preservation);

~Education and Culture (Nova Scotia Museum, Cultural M i r s ) ; and

Abonginal Affairs.

9

The study was limited by some unknown issues that lay beyond its scope: Since cultural

tourism is still an emerging field in the tourism industry, an adequate understanding of the

"characteristics" of the cultural tourism niche still appeared difficult. Additional research

was also felt necessary in identifjing cultural tourism products, packages, and marketing

strategies that would show promise in enhancing Nova Scotia's 'competitive advantage' in

the cultural tourisrn market. It was thought this could be accomplished by first defining the

'characteristics of dernand' of tourists who do travel to Nova Scotia.

While recognizing a need to further research demand characteristics, Tourism Nova Scotia

also decided to develop a strategy for the selection of tounsm businesses to support. It

was recognized that a 'continuum of potential' existed among tourism businesses in the

province. This continuum consisted of businesses that are 'killing " to attract tourists (

but have not made a commitrnent to do so); that are "ready " (and which have made the

financial and human cornmitment to enhance their products appropriately); and finally who

are "ahle " to do so (and who have the product and the marketing to make it happen)

(ARA / LORD, 1997).

2.5 The Results of the Studv

The ARA \ LORD study tried to determine the characteristics of demand of the consumers

of cultural tourism. This was done by taking a sample fi-orn the 1992 Tourisrn Nova Scotia

exit survey and defining two 'sub-sets' from the sample. One sub-set was composed of

tourists who stated they participated in activities that were defined as having both clear

cultural linkages (i.e. Museums and historical sites, performing arts, art galleries) and

strong cultural associations (e.g. festivals) in the activities they took part in while on

vacation . The other sub-set was composed of individu& who did not identie any cultural

activity as part of their vacation. Their answers are reflected in the following tables.

10

Despite some limitations in the survey, the results showed a number of interesting

findings3. To begin with, it was found that up to 65% of al1 tourists to Nova Scotia have at

least a partial interest in cultural activities. Most cultural tourists tend to be fiom non-

Atlantic Canada origins. Up to three times as many cultural tourism visitors carne fiom

other parts of Canada and fiom international origins as non-cultural tourkm visitors. This

would appear to indicate a strong market of potential tourists willing to travel to Nova

Scotia on the strength of its cultural assets.

Table 2.1: Oririn of Cultural Tourists Origin 1 Cultural Sub-Set ( Non-Cultural Sub-Set Atlantic Canada 26% 73% Canada (Other) 47% 8% International 27% 19% Source: ARA \ LORD

Incomplet e Technical College: Complete 3% lncomplete 19% University: 8% Complete 47%

Table 2.2: Education of Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists

lncomplete Source: ARA / LORD

Education (Main Earner)

The study states that cultural tourists tend to have higher levels of education than non-

cultural tourists. This kind of information would be consistent when considering that the

cultural tounst prefers to l e m about his or her tourist destination and is willing to take

the time to gain that understanding.

High School: 5% 9% Complete 1 8% 23%

Cultural Sub-Set

? Snmplr sizc of survry i s 84,000 oi'in estbatrd 418,?00 tounsts visiting bctwccn mid-Mny to Octobcr. Thrcr o f the s i . catcgones usrd in the s u n y may ooc bc considercd "pure culture", Tourists nre dcGncd as cu lh id tounst only bccausc thcy pahcipnted in six cultural activitics dcfmcd for thir study.

Non-Cultural Sub-Set

The incomes of cultural tourists tend to be higher than the incomes of non-cultural

tourists. This information is consistent with data from other surveys and observations

made by businesses dealing in the cultural tourism industry (ARA / LORD, 1997).

O to $20,000 7% 8% $20,000 to $40,000 22% 25% $40,000 to $60,000 3 IYo 35% $60,000 and above 40% 35% Source: ARA 1 LORD

Table 2.3: Income of Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists

Cultural tourism visitors are more likely to be on pleasure trips then non-cultural tourism

visitors. This finding indicate that cultural tourists are half as likely to report that business

Non-Culturd Sub-Set Total Household Income

is their main purpose for traveling to the province. A striking difference was evident when

Cultural Sub-Set

comparing international to Canadian cultural tourists. Around 39% of al1 cultural tourists

reported pleasure as their main reason for traveling to the province.

Table 2.4: Reason of Travel for Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists 1 Cultural Sub-Set 1 Non-Cultural Sub-Set

1 6% 28% 39% 16% 3 8% 37%

7% 19% Source: ARA 1 LORD

One ARALORD survey question asked whether a business trip was extended to include a

cultural tourism component to their travel plans. The results indicated this was so and that

the extended length of stay translated into increased economic benefits for the province.

This is considered by the authors to be a key finding since it demonstrates that there are

direct economic benefits in cultural tourism development and promotion.

Table 2.5: Extension of Stav between Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists Business Trips 1 Cultural Sub-Set 1 Non-Cultural Sub-Set Extend to include 35% 1 0% pleasure component Length of Extension 2.9 2.2 (days) Brought Farnily / 22% 11% Friends on Trip Source: ARA 1 LORD

When asking what reasons travelers had for coming to Nova Scotia, the most surprising

result was that no group said that they had corne here for the History 1 Culture. This

Table 2.6: Reasons for Travelin~ to Nova Scotia Reasons for Visiting 1 Cultural Sub-Set 1 Non-Cultural Sub-Set Curiosity 26% 23% Ot her 14% 1 9% Specific Area 10% 9% Visiting Maritimes 7% 5% Been here before 6% 5% Recommended 6% 4% Scenery 6% 7% Visit Friends and 5% 8% Relatives See Coastline 4% 6% Festival or Event 4% 6% Former Resident 3% 4% Advertising 2% 0% History 1 Culture 0% 0% Source: ARA / LORD

appears to indicate that travelers were unaware of the culturd heritage but "discovered"

them upon amving to the province. The most cornmonly given reason for traveling to

Nova Scotia was out of curiosity at 26% and 23% respectively for the two sub-sets

(Culturd and Non-Cultural).

The modes of transport used between cultural and non-cultural tourists indicate a

difference. Cultural tourists appear to more ofien use air travel or recreational vehicles

rather then a car. The larger numbers of airplane amivals for cultural tourists may indicate

a tendency to use long-distance, pre-packaged tours when arriving. This fact is confirmed

in a tour operator survey that indicated that 77% of their clientele traveled by air to reach

their destinations (ARA / LORD, 1997).

The average length of stay of the cultural and the non-cultural tourist was found to be

quite different. The cultural tourist stayed around 7 days as opposed to 4 days for the non-

cultural tourist, This data was confirmed in the tour operators survey in which 32% of

respondents said their cultural-oriented clientele preferred to make trips of more than 1 4

days, with 2 1 % prefemng 8- 14 days instead (ARA / LORD, 1 997).

Table 2.7: Method of Trans~ortation for Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists Mode of Travel 1 Cultural Sub-Set 1 Non-Cultural Sub-Set Automobile 65% 76% Recreational Vehicle 6% 4% Airplane 29% 20% Source: ARA / LORD

Cultural tourists tend to spend more while traveling than non-cultural tourists. This would

appear to be an important factor especially in combination with the longer length of stay

that cultural tourists tend to have while visiting.

Another interesting discovery ofthis survey was that the cultural tourist is more likely to

take part in a variety of general activities than the non-cultural tourist. It is also important

to note that besides shopping, the non-cultural tourist seems to take part in fewer forms of

Table 2.8: Spendin~ Com~arisons between Cultural and Non-Cultural Tc ExpenditurelPart Trip 1 Cultural Sub-Set 1 Non-Cultural Sub-Set Accommodation $202.42 $94.76 Restaurants $192.97 $83.05 Entert ainrnent $ 52.12 $1 1.50 Taxi and Car rentd $46.75 $14.17 Shopping $126.55 $5 1.63 Gas and Auto Repair $ 8 1.95 $42.9 1 Groceries and Liquor $ 53.47 $1 8.40 Ot her $ 8.54 $ 7.39

[ Total $764.77 $323.81 Source: ARA / LORD

urists

Table 2.9: Activities of Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists

Rcspondcnts under the culturil tourirt cntcgory wcrc tourkts who chosr six rctivities (crift shop, muscurns nnd historic sigbts. oight clubs

and I O U D ~ C S , wcnts a d fcslj\rds, prrfomiing iris and gnllcrits) thnt &cy bid idcntificd as prrticipnting in. Thosc in the non-cultural c i l egos chose nonc of tbrsr activitics.

Non-Cultural Sub-Set Participation in General Activities Shopping 78% 42% Craft Shops 70% 0% Museums and Histonc 58% 0% Sight s National and Provincial 43% 5% Parks Antique Shops 37% 2% Night Clubs, Lounges, 33% 0% Pubs Special Events and 21% 0% Festivals Guided Tours 1 7% 0% Bird Watching 16% 3% Live Performing Arts 15% 0% Art Galleries 14% 0% WhaIe Watching 12% 1% Theme or Amusement 6% 2% Parks

Cultural Sub-Set

Source: ARA / LORD

The percentages listed under the two sub-sets indicate that most cultural tourists tend to

participate in a wide variety of activities while on holiday in comparison to the non-

cultural tourist.

The research indicates that cultural tourists are more likely to participate in physical

activity than non-cultural visitors. This could indicate a strong linkage between nature or

eco-tourism and cultural tourism which could offer possible CO-operative marketing

ventures. The figures d so show that cultural tourists often take part in many more

out door activities in comparison to the non-cultural tourist .

The anaiysis also showed that a significant number of cultural tourists had not visited the

province before when compared to non-cultural tourists. This result could be a reflection

of the non-cultural tourist being here primarily for business. (ARA / LORD, 1997).

While many cultural tourists appear not to have visited Nova Scotia before, they are likely

to travel to more than one of the other Atlantic Canada provinces when they do corne.

This would appear to indicate that Nova Scotia is likely to compete with the other Atlantic

provinces for the cultural tourist which underscores the need to coordinate efforts among

the four provinces.

In summary, the ARA / LORD study found that the profile of the cultural tourist appears

to have a number of traits needed to be considered when determinhg the characteristics of

demand. To begin with, cultural tounsts tend to be well educated and possess a higher

income. They tend to stay twice as long as others and travel in larger groups. They will

16

Table 2.10: Com~arison of Phvsical Activitv between Cultural and Non-Cultural

Walking 74% Wildemess hiking 25% Going to a beach 38% Swimming 20% Boating, Windsurfing 12% Fishing 9% Golfing 8% Bicycling 5% Canoeing 3%

Tou ris t

Tennis 2% 1% Source ARA / LORD

Table 2.11 : Prior Visits of Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists, r~revious Trips to 1 Cultural Sub-Set 1 Non-Cultural Sub-Set 1

Non-Cultural Sub-Set Participation -

Nova Scotia 1 1 Visited before 70% 88%

Physical Activity Sight-seeing 84% 41%

Culturai Sub-Set

1 Never visited before 30% 12% 1 Source: ARA / LORD

Table 2.12: Likelihood Cultural and Non-Cultural Tourists will Travel Elsewhere in

Provinces I I Visited at least one 53% 39% other Visited New Brunswick 46% Visited Prince Edward 25% Island Visited Newfoundland 7% 7% Source: ARA 1 LORD

spend more than the average visitor and travel for pleasure more so than others. In

addition, cultural tourists appear to have wide tastes and participate in a Ader variety of

events and activities. They tend not to have visited Nova Scotia before, or are less likely

17

to have visited recently, and are more likely to also visit other provinces in the region.

They are also more likely to use a travel guide when planning and deciding to see things in

Nova Scotia (ARA / LORD, 1997). The cultural tourkt appears to be more selective when

traveling, making the provision of accurate and effective information important when

trying to sway their decision-making.

2.6 Identieing the Characteristics of Demand for Nova Scotia

This ARA study attempted to use a strategic focus to understand the needs of the cultural

tourism market and give a sense of what will be needed to attract and service the cultural

tourism segment (ARA 1 LORD, 1997). Gven the traits identified in the survey, a picture

emerged concerning the things tourists were looking for when traveling to Nova Scotia.

The following is a general listing of the characteristics of demand that appear to influence

tourists in the province. The list is derived from previous research and fiom secondary

sources provided by tourism Nova Scotia. It includes the following:

Awareness: There needs to be an awareness of whatever cultural site, event, or product is

being presented by a community to the cultural tourist. This advertisement can come from

recommendations from fiiends, travel associations, or some other group that the cultural

tourist can access about travel within the province.

Quality: Because cultural tourists are seen as generally coming from a higher educational

and income bracket, they will also tend to want something of higher quality and value as

they travel. This could be interpreted to mean that communities wishing to capitalize on

increased cultural tourist traffic need to create a high standard of quality in the heritage

landmarks visited, cultural products produced, and the experiences created during cultural

events. In this regard, quality could be seen as developing culhirally and historically

accurate portrayals of whatever cultural product or event is identified by a community. A

key component in defining the authentic.

Uniqueness: Given the growing level of world competition for tourism, the need for

communities in the province to develop unique aspects of their local cultures is important

18

to ensure the visitor will come, spend money and perhaps visit longer. It is important to be

perceived as unique, but also to have enough 'depth' in that uniqueness to be able to

sustain the interest of the visitor.

Entertainment Value: The perception of a cultural product's 'entertainment value' will

determine if a visitor (who is primarily traveling for pleasure) will want to stop. M a t

entertainment value means specifically to a cultural tourist could be the ability to have

more of a 'hands on' approach to things like local craA making, access to on-going

archeological digs, or the ability to learn and interact with musicians and artists.

Convenience: There has to be recognition of the need to work within time-fiames and

schedules that are convenient for the tourist. This would imply seasonal considerations,

but it also means that events and sites are accessible over longer periods during the day.

This kind of criteria would suggest that more rural communities need to be willing to alter

their normal business operating hours, at Ieast for tourism-related businesses, perhaps

seasonally. This would be in order to solve potential time restrictions in traveling fiom one

community to another so the traveler has time to reach an event to make the trip worth the

effort.

Value for Time: This would relate to the issue of whether a cultural event or site

developed by a community has the capacity to attract tourists and satise the criteria

mentioned above on its own, or in combination with other tourkm assets in the area. This

depends on whether there is enough CO-operation between cornmunities to 'pool' tourist

assets and CO-market them to better ensure tourists become interested and see a particular

cornmunity as a 'link' in a chah of cornrnunities with unique attractions.

Value for Money: Despite the suggestion that the cultural tourist is willing to pay more

whiIe traveling, this still remains dependent on whether the tourist is receiving his or her

'money's worth', This raises issues of what communities should do to ensure that the

relationship between quality and integrity of a cultural product is established and

maintained to ensure a fair price.

Need to Feel Welcome: The final criterion suggested by the ARA study recognizes that

cultural tourists also want to feel they are being treated as a person with respect and not

simply as a source of money. This criterion depends as much on how the cornmunity feels

about itself as it does about the traveler. There needs to be enough space between the

visitor and the community to allow both to enjoy their own lifestyles, without too much

congestion, possibly causing 'fiction' between the two.

In Nova Scotia, a demand for more diverse samplings of culture by the tourist is good

news for those involved in the tourism industry since it can create new opportunities to

strengthen local community econornies. But first the tourism industry in Nova Scotia

needs to integrate a method of incorporating unique cultural assets in both community and

tourism business plans. Cultural assets would not only include the built heritage of the

many ethnic and cultural groups in the province, but also the 'living' cultural heritage

(which could provide the basis for many events) the products, and the seMces that can be

provided for use in tourism. Clearty a method of integration is needed to change the

perceptions and misconceptions that planners and tourism developers may have toward

each other. This is why efforts have been made to emphasize a need to focus on

est ablishing a 'competit ive advantage' approach to tourism planning.

The need to be honest with the cultural tourist in authentically portraying any tourist site,

event, or service cannot be over stated. However it remains very difficult to design and

maintain some level of product compliance without being seen as limiting ''artistic"

creativity or by "adding another layer" of regulation upon an industry that finds the idea of

too much bureaucracy abhorrent. In light of these concerns, the planner needs to rely on

more non-traditional fonns of planning enforcement.

In order to understand what role planners can play in preserving the authenticity of

cultural tourism development it is important to review some of the theory and research

20

done on both the planning profession and on cultural tounsm management. Such a review

can help draw out lessons that can allow readers to understand both the limits of planning

and the opportunities that exist for the profession to provide a method of preservation and

conservation of local culture.

3.0 Planning Theory Through a Historical Context and its Relation to Cultural Tourism

3.1 Introduction

Mile it has been argued that cultural tourism is primarily an economic venture that must

be planned with marketing strategies in mind, professionai planners still need to consider

the impact on the host community and the effect tourism development has on the quality

of life for local people. With this in mjnd, the planners should help create an environment

where both the community and professionals can ofEer their expertise and advice on a

number of technical and social matters. Such interactions cm lead to more sustainable

approaches in tourism planning.

3.2 Sustainable Development and Cultural Tourism Planning

Sustainable tourism is best viewed as an extension of conservation - which can be

described as the wise use of resources (Gunn, 1994). While defined in many ways, Bill

Rees, of the School of Cornrnunity and Regional Planning at the University of British

Columbia, offers the rnost appropriate description of what sustainable developrnent can

mean for tourism planning.

"Sustainable development is positive socioeconomic change that does not undermine the ecological and social systems upon which communities and society are dependent. Its successful implementation requires integrated policy, planning, and social learning processes; its political viability depends on the full support of the people it affects through their governments, their social institutions, and their private activities" (Rees 1989).

22

When exarnining the impact on touisrn of this definition, some key points corne out. To

begin with, the premise of "positive economic growth" implies growth that is tempered

with the need to be seen as enhancing social and economic growth. A change must be

qualified by whether or not it undermines the "ecological and social systems" which are

seen as vital to the stability of a comrnunity and society (Gunn, 1994). The definition also

states that certain actions, such as "integrated policy, planning, and social leaming

processes" are needed to ensure implementation of a sustainable tourism industry.

Gunn states that sustainable tourism can only be achieved through a recognition by

developers and business operators of the importance of maintaining the cultural and

natural resources (Gunn, 1994). Getting developers to recognize this has proven difficult

in the past. One approach that has had success is through alerting tourism developers and

the host communities of the economic value of retaining and preserving cultural heritage.

By arguing the competitive advantage of preserving Nova Scotia's authentic cultural

assets, the tourism industry has a better chance of remaining a sustainable industry into the

future.

Obviously, Competitive advantage is defined as a way to differentiate oneself from

competitors. Porter describes the concept as follows:

Competitive advantage grows out of value a firm is able to create for its buyers that exceeds the firrn's cost of creating it. Value is what buyers are willing to pay, and superior value stems from offering lower prices than competitors for equivalent benefits or providing unique benefits that more than offset a higher price. There are two basic types of competitive advantage: cost leadership and differentiation (Kotler and Turner, 1989).

The concept of competitive advantage has had a 17 year history as an element in tourism

marketing strategy and has been used as a tool for planning the accommodations sector,

23

the resort s development sector, and the transportation sector (Seaton and Bennett, 1 996).

According to Young Nichols and Gilstrap (1996), planning tounsm around a competitive

advantage approach can achieve a number of goals that can sustain tourkm for a region.

The goals include:

Establishing the idea that the destination competes in a distinctive niche.

Helping establish specialized resources (labor, management, capital, suppliers) that

reinforce that niche and which have been trained or attracted to the market.

Creating the conditions for the customers to perceive that the destination is the leader - often the global leader - in its niche.

Encouraging new investment and resources to be attracted to the market, reinforcing

the destination's leadership position.

In the end, the customers' perception, the focused resources and the attraction of the

new investment is felt to make it harder for other destinations to copy the strategy

successfùlly .

Source: Young Nichols Gilstrap, Inc., 1996

Many of these goals can be achieved once a cost advantage or product differentiation is

achieved. The specific methods used by many cornmunities to achieve these goals involve

developing public-private partnerships and appropriate 'market planning7 techniques to

at tract investment and stimulate local entrepreneurial activity .

However, rnany cases exist where destinations use similar marketing tactics (i.e. lower

prices, increased advertising, etc.) and often lose out to other destinations over time

simply because of natural advantages one destination has over another (such as a physical

proximity to large population centres, etc.) This concern is evident in locations where

there are few major attractions in a given area to attract visitors fiom any great distance.

Part of the solution to developing a tourism industry in relatively isolated locations is to

avoid "head-to-head" cornpetition with local communities, and allow planners dong with

members of business and the community to create distinctive niches that can attract

specific types of tourists. This approach of focusing on local "competitive advantages"

means that choices have to be made regarding what kinds of tourkm products are

developed. Some of those choices, in places like Nova Scotia, must include deciding what

product or cultural feature to market and how best to present this to the touring public.

For planners, a major concern must be how best to maintain comrnunity heritage (which

these products would be based upon) to ensure its continued integrity for future travelers?

In order to maintain a competitive advantage in the cultural tourism market, steps need to

be taken to ensure tourism operators are able to create and maintain value in local

products that exceeds the cornpetition elsewhere. This means that planners and tourism

operators have a cornmon stake in protecting unique aspects of a community for the sake

of fiiture tourisrn stability. Such a goal involves meshing the "presentation and

preservation" of a host community's cultural heritage. In order to present cultural

heritage, action must be taken to ensure the survival of the physical and social f oms of

culture. Some comrnunities, such as Lunenburg, have done a great deal in this regard.

However, preserving culture also rnust involve respecting local sensitivity and attitudes

regarding the impact tourists will have on local lifestyles. While the planner has tools to

deal with some aspects of this issue (such as heritage property preservation, zoning, etc.)

there are other aspects that require closer partnerships with the community in order to

succeed. In this regard, lessons can be learned fiom the experiences of other small

communities that are trying t o create a community-driven tourism industry . In Nova

Scotia, planning legislation may be in need of change on order to allow cuItural tourism

operators the opportunities to take advantage of any competitive advantage they envision.

When looking at the role professional planning has played in cultural preservation to date,

it can be said that planners have failed to play a stronger role in ensuring that local

heritage is correctly interpreted within tourism developments. For example, Nova Scotia's,

23

Upper Clement's Park development, has drawn some cnticism in the past over its

inconsistency in portraying the "living" and built heritage of Nova Scotia culture

(Stevenson, 1997). Some critics have pointed specifically to the lack of community input

into its design and purpose (Plaskett, 1997). Some of these gaps in the park's design were

created due to a lack of research and interest in the design (and choice of material) in both

the products and the buildings within the Upper Clement's "Village". Another concern

involves the focus of the development, with the educational and cultural aspects of the

park being cheapened and undermined by the entertainment which includes such things as

carnival rides and miniature golf courses in the shape of Nova Scotia (Mackay, 1994).

3.3 Places. Images. and Marketing

For any cultural tounsm development to be successfûl, it is clear that successful marketing

and promotion is key. Any promotion or marketing strategy wouId need to include a

description of the physical and intrinsic qualities of the cornmunity, region, and/or

province the destination site is in. Because of the number of intrinsic qualities to any

particular place, which are in themselves made up of many features, it is difficult to fiilly

describe for tourists the location without becoming too obscure - which would only tum

off potential visitors. To avoid this, specific images of the location are carefully created.

The choice of image used by a marketing strategist to attract visitors is important since the

image projected helps the tourist determine if and on what ternis, the tounst will travel to

the site. In this sense, "images are more important than tangible resources" (Hunt, 1975).

While their are vast amounts of material available on the psychology of image projection

and reception, it is best to lirnit our inquiry to material that is the rnost relevant to planning

and tourism marketing. Therefore two limitations should be set:

26

1) Our definition of place needs to be narrower than what many psychologists and

behavioral scientists would prefer to have. In this case, Our definition of place will be

limited to a planned or existing development site or host comrnunity.

2) The marketing process is assumed to be concerned with only one sort of behavior, that

of the tourist.

When someone tries to create an image of a place, it is ofien pojected through a set of

cultural codes. These codes can then be trarmitled through a variety of channels that exist

in Society (media, word-of-mouth, etc.), which can be distorted to the point of losing some

of the information originaily received. Any image received after traveling through these

filters is again decoded by the final receiver and used as images to construct a potential

tounst's perception. It is during the coding and decoding of these images that "signifier"

objects or images cm trigger "signifier" feelings or states of mind within the receiver

(Ashwood and Voogd, 1990). These "signifiers" can be specific place-images, icons, or

feelings that the potentiai tourists normally carry's within themselves.

Image promotion, where community marketing is concerned, is rarely the creation of

images in a "perceptual vacuum." It is more likely the accommodation, modification, or

exploitation of exiçting images, derived fiom rnany sources which marketing has little

control over (Ashworth and Voogd, 1990). Within this environment, the receiver is not

passive to any message that cornes by affecting his or her existing images and behavior.

Rather, the union of message and receiver is more likely a result of 'active collusion'

(Uzzell, 1984), which is the result of pre-existing associations and biases. In most cases, the

promotion of a place without such reference to pnor images is Likely to be used only if it is

clear that existing place-images are so negative that they prevent achieving the desired

effect of attracting tourists.

Describing the properties of a promotional image of a place, despite the amounts of

research done, remains a difficult thing to do. However, enough work has been done in

certain fields to provide some insight. From a marketing perspective, research studies

provide interesting insights on measuring the effectiveness of transmitting particular place-

images (Ashwonh and Voogd, 1990). These studies describe, as ülustrated in Figure 3.1,

the central role of image promotion in creating an 'evaluative image'. Evaluative images

corne fiom an advertisement and ''preferential images" fiom the potential consumers

motivation. These are compared by the potential consumer and is the basic method for

selecting new information. In tirne, this method becomes expanded as the consumer gains

the experience of actual consumption. This can then lead to the attainment of levels of

satisfaction or dissatisfaction for the consumer (Ashworth and Voogd, 1990).

NEEDS AND DESIRES

I I + MOT IVATIOKS 4

images PREFERENCES PFRCEPTIONS 4-' opportunities I I

Place Images in the Decision-making Process

(Figure 3.1 - Ashworth and Voogd, 1990)

Obviously, the work of the marketer is to provide carefùlly designed place-images which

help influence a potential tounsts behavior enough to allow him or her to decide to travel

to a specific destination. Yet, despite the effon, targeting specific markets has rarely

achieved precision. Therefore, anyone promoting a place is never certain and ultimately

the decision is leA to the prejudices of the receiver who accepts, rejects, or modifies the

28

message promoted (Neisser, 1976). Studies of the nature of these prejudices has helped

marketers gain a better understanding of the nature of place-images and their relation to

"image components" that carry special significance to individuals. Some image

components also hold some significance for people from V ~ ~ O U S ethnic and cultural

backgrounds (Lynch, 1 960).

3.4 Ethnicity and the Marketability of Culture

Because of a recognition by marketers of the power of family and cultural ties in many of

us, one marketing technique is used to target people with sirnilar cultural ties to a product

or service that could have some special cultural meaning.

In the past, Worlds Fairs and other global events have allowed cities to present their

cuItures in tems of spectacular structures and landscapes that became symbols to promote

their respective cultures (the Eiffel Tower in Paris comes to mind in this case). Many of

these structures are left as symbols of the power and achievement of the societies that

produced them. Over time, many modem cultures have asserted their existence by creating

products that translate its qualities into cultural meanings (Firat, 1995). In a visually

oriented modem world, this can be the best way to exert ones existence. The more that a

culture translates its qualities into marketable experiences, the more they translate an

essence of their cultural experience beyond their onginal borders. Sorne believe this

difision of cultural symbols around the world has the potential of endangering less

dominant cultures (Alavi & Shanin, 1982; Featherstone, 1990; Keane, 1990), but the

potential is also their to raise the interest level of tourists in cultures that may otherwise

have had little chance to raise their profile.

Contrary to a common fear over the "Americariization" of World culture, the current

trend toward World globalization does not seem to be an event in which one culture or

style of life is dominating. Rather, this trend appears to be turning into a diffusion of

29

different forms of existence from around the world. On the contrary, the rising interest in

culture can be partially attributed to a general weakening of uniforrnity and universality in

the approaches to living. In the United States, the idea of the "Melting Pot" has given way

to the acceptance of a "Cultural Mosaic" within that nation. This tendency to respect and

allow different ethnic, religious, social, and ideological cultures to flounsh appears to be

gaining strength in the U. S. (Firat, 1995). These trends in the U. S. (and sirnilar

experiences in Canada with its multicultural policy) are not limited to North Arnerica.

There seems to be a conscious effort by consumers, regardless of their nationaiity, to

experience different styles and cultural artifacts (Firat, 1995).

3.5 Concepts of Authenticitv and its Role in Tourism

While cultural tourism can take many forms5, some critics have commented that the

challenge of exploration and the chance to experience authentic culture has been

undermined by tourism. Researches, such as Boorstien have strongly criticized the tourism

industry by claiming that traveling in search of authentic experiences has been emasculated

by mass tourism (Murphy, 1985). This kind of concern raises the question of what is

meant by authenticity in cultural tourism.

To begin with, the level of cunosity and desire for authentic experience varies with the

traveler. The type of traveler who wants to seek out authentic experiences has the time

and interest to explore how other cultures operate. Yet, even without the time, the

majority of travelers still have some level of interest in authentic experiences (Murphy,

1985). Besides the different levels of interest in authentic experiences by travelers the level

of authenticity within a destination will also Vary according to the local priorities and

capacity of the host community to accept tourists into an authentic experience.

- - - --

"me of the more popular aspects of local culture that toudsts seek out include: Handicrafts; Language; Traditions; Gastronomy; Art Music; History; Work engaged by residents; .4rchitecture; Religion - including its visible manifestations; Educationai systems; Dress; aud Leisure activities (Muiphy, 1985).

30

Cohen offers a view of authenticity that tries to identiQ the his form for both the host

cornmunity and the tourist (See Figure 3.2). Needless to say, the ideal situation occurs

when both the tourist and the host cornrnunity view an event o r attraction a s authentic.

However, Cohen does point out that situations exist where either host o r guest can

perceive an event or attraction as authentic, while the other does not feel it is so. In

situations where the event or attraction is staged, but based on genuine components and

events and put together for the convenience of both tourist and host comrnunity there is

ofien little problern. But problems c m occur when a setting becomes contrived by being

artificial in content andor location, while portraying t o be otherwise.

Real

(4) Scageà authenmty (3) ConEnd (-a t- -1 (oireriiarristspace)

Types of "Touristic" Situations

(Figure 3.2 - Murphy, 1 989)

Within a contrived cultural tourism setting, Boorstein describes four comrnon

characteristics. First, such settings are not spontaneous or natural events. Second, they are

designed to be reproduced so they occur at times convenient to the tourist rather than

what is normal or appropriate to the comrnunity. Third, the relationship of a contrived

event to authentic events or reality is ambiguous. And fourth, the contnved experience

may become seen as the n o m over time as the contrived representation o f authentic

events is allowed to be interpreted as authentic by visitors (Murphy, 1985). Over t h e , the

perpetuation of contnved cultural tourism developments can make the local cultural

tourism industry lose its sense of uniqueness and this can undermine any cornpetitive

advantage fiom cultural tourism.

3 1

3.6 Acculturation and Cornrnunit~ Tounsm

Part of what Hughes has raised is a concern for the long-term effects o f 'acculturation' on

communities that choose to develop a tourism industry. It is true there is some benefit in

making more people aware of isolated cultures through tourism, however, there are also

some risks in "overexposing" a relatively isolated community culture to a mass tourist

population. One fear is that tourism has the potential t o undermine the cultural uniqueness

of the communities that embrace tounsm without fiilly preparing for it. This type of local

cultural erosion is known as 'acculturation'.

Acculturation is defined as a slow loss of unique cultural assets over time by isolated

comrnunities who absorb or borrow facets fiom a more dominant 'urban-industrial'

cuIture (Murphy, 1985). The concern over acculturation is evident in what Papson calls

"Spurious Reality". Papson raises the concem that reality (as presented within a cultural

site) can become spunous because, in many cases, events, attractions and the physical

design can be created or imposed by agents outside everyday community existence. Such

agents could include developers, planners and govemment officials fiom outside the

community whose main concem would be economic development (Papson 1981) rather

than the accurate reflection o f a local culture.

In rnany locations around the globe, tourism has played a role in transforming collective

and individual values through cornmoditisation (Cohen, 1977). Cohen obsewed that

through increased tourism on isolated communities, ceremonies that had represented a

particular 'cultural' display of living traditions or a 'cultural text' of living authenticity

became a 'cultural product' which then has to meet the needs of commercial tourism.

Over time, the value for any s u ~ v i n g practice becarne based on profit, not on the original

cultural value that originally created it. The impact that this has on members of a host

community can be economically beneficial, but socially destructive unless new meanings

are created by the host community.

32

In recent years, Australian aboriginal art has become very popular in the Art world. In

becoming a marketable cornrnodity, Aboriginal art could become rernoved from its

traditional social and cultural environment with time (Wall, 1994). For example, Hall noted

that art foms fiom the Papunya Tula paintings of Central Australia, are now produced in

large quantities to meet tourist demand. The mass production of this cultural artwork has

led to reduced quality of the copies produced and to a potentiai degradation of meaning in

the artwork through the 'ccornmercialization and trivialisation" of such an important event

in Aboriginal culture (Hall, 1994).

In Nova Scotia, the tourism industry has invested a great deal into creating a "folk"

culture for the province which some argue has been exploited "past the point of

credibility" (MacKay 1994). In the past, the creation of the image of the "folk" has helped

encourage tourkm into Nova Scotia. MacKay feels that because of the past success of this

promotion, the province has increasingly promoted itself as a land of Folk festivals and

handicrafts, which ultimately undermines the tme picture of the province. For example, the

Department of Tourism and Culture have rnounted promotions on the theme of the "Year

of the Quilt." in 1989 and the "Year of the Basket." in 1991. During the late 1980s,

Halifax also began to build its tourism promotion around an "International Street

Pedormers Festival" (The Buskers) which became one of the major events of the summer;

helping to draw large numbers of people to visit the province in 1987. In 1988 the Buskers

Festival was promoted by the then minister for the Department of Tourism and Culture as

part of the province's long standing Folk customs:

"Our Province and our people have much in common with the traditions of the Buskers. We share an appreciation for music and singing and dancing for its own sake, and as part of a community experience. The Buskers establish a very personal relationship with their audience - to the point where the audience becomes part of the perfomance. Its

the same spirit you'ii find at a genuine Cape Breton ceilidh"(MacKay, 1994).

The Buskers Festival provides a good example of MacKayYs concern over the "post-

modem adaptation of the idea of Folk." The Buskers has folk-like qualities, but in reality

has nothing to do with traditions distinctive to Nova Scotia. The Buskers are simply a

'spectacle', organized by private business and supported by govenunent (Mackay, 1994).

According to Greenwood, when a cultural activity is made into a public event, like an

asset to be sold and promoted in the tourkt marketplace, the meaning of the ritual can be

directly violated, "definitely destroying its authenticity and its power for the people"

(Greenwood, 1989). Greenwood explored a case involving the Alarde festival of

Fuenterrabia, Spain. He noted that originally the festival was not performed for pay, but as

an affirmation of local belief in their own culture. When the municipal goverment

declared that the AIarde should be marketed as a tourism package for the t o m , the local

people still performed the 'outward foms of the ritual' for money, but could not subscribe

to the meanings it once heId because it was no longer being performed by 'them for

themselves'. In time however, the community were able to attach a new meaning that was

acceptable to them:

"it has now become much more of a political event and is imbued now with contemporary political significance as part of the contest over regional political rights in SpainW(Greenwood, 1989).

These observations would seem to confirm that while tourisrn potentially can weaken local

culture. The host communities still have the power to create new meaning and significance

into cultural events themselves.

34

The experiences reported on in Spain demonstrate that communities are perhaps more

resilient when faced by tourism than are given credit for. More contemporary academics

are acknowledging this in their recommendations in cultural tounsm design. For example,

Boniface stresses that our attitude toward culture must change in order to better serve the

tourist. She argues that the "idea" of culture needs to be made paramount over its form.

(For example, having no qualms over creating duplicate replicas of cultural sites in order

to better allow public access and to spread tourist dollars around a specsed region).

Boniface dso questions whether one has to travel to the exact site where an event took

place in order to gain some form of experience from it. Her alternative is to create replicas

or facsimiles of a cultural sight as either a physical reconstruction or a computer generated

re-creation (Boniface, 1995). By using such facsimiles, Wear and tear could be kept to a

minimum on sensitive sites (as wefl as communities whose infi-astructure would be

overburdened by potentially high numbers of travelers) and the tourism industry could still

have a cultural 'creation' established for the use of tourists.

3.8 Market-Incentive Planning and Efforts to Inteerate Planninn and Business

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, traditional planning has been under assault from

supporters of the "public-private" partnership. And yet, while Beauregard argues that

these types of arrangements are removing planning decision-making from public review.

This does not have to be the case to satisfy tourism business partners. In fact, market-

incentive planning can ofTer some fiesh insight into how plamers view their role in tourism

planning.

While physical planning is primarily "supply-oriented" (attention being given to

investigating the constraints and physical possibilities of the built environment). The

"demand-side" is usually treated in planning practice as something to be dealt with as a

final goal, but not necessarily something that can determine the treatment of the built

environment (Ashworth and Voogd, 1990). The measures of success and standards of

36

4. The regulation of the urban system in the interest of social groups whose market

position is intrinsically weak;

5. The regulation of developrnent towards longer-term goals than are included within