BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY: HISTORY AS NOSTALGIA, …

Transcript of BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY: HISTORY AS NOSTALGIA, …

BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY: HISTORY AS NOSTALGIA, NATURE AS

REGRETAn Artist Looks at Historic Sites, Space and Time

Despina Metaxatos Bergen Community College

My interest in space was prompted by my return to New Jersey following three years spent in the wide-open spaces of Western Australia. I experienced firsthand the ways in which physical space impacts many aspects of our lives – our daily routine, our perceptions, and especially our mental space. On my return home, I developed a renewed interest in the history of my town, Teaneck, and in the history of Bergen County in general. If low population density and physical distance affect the ways in which people relate in Western Australia, these factors may have played changing roles in the development of my town from its colonial-era roots to the present. That the expansive sense of space, time, and wild nature I associated with Western Australia had once existed in New Jersey was a revelation in broad daylight, while also provoking a curious sense of loss. “History is experienced as nostalgia, and nature as regret – as a horizon fast disappearing behind us,” writes French philosopher Henri Lefebvre in The Production of Space. Gradual shifts in our perception of space and time began to appear radical as I investigated and photographed historic Bergen County sites such as Paramus’ Red Mill or Arcola Tower, now imprisoned in a Route 4 cloverleaf, thus becoming a locus for Lefebvre’s discussion of “dominated space.” As physical space is usurped by virtual, abstract screen space, the concrete acquires that aura of nostalgia in places where the past punctures our present grid.

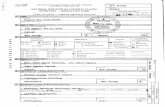

At the museum he operates on Sundays in his retirement, Fritz Behnke shows me a vintage map of the farmland his grandfather acquired in the village of Paramus, Bergen County, New Jersey, in 1886. On the rectangle fronting Paramus road is written “Behnke” in a beautiful cursive script (Bromley). The land on the map has a

personality, surrounded by other family names. I try to picture the acres of black soil celery farm shown in museum photographs in place of the malls and highways that Paramus is known for today.

It’s a peculiar form of time travel. In the 1970s, the Garden State was “the first state to be declared to have no rural areas remaining based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s definition of population density” (Wortendyke). When Mr. Behnke was born in

1919, coming to Paramus might have meant rabbit or turkey hunting along Sprout Brook, not bargain hunting at Paramus Park Mall. Between 1950 and 1960,

following the construction of Routes 17, 4, and the Garden State Parkway crisscrossing the ten square miles of Paramus, Behnke and many of his neighbors sold off most of their land for malls. The sale of their land, he tells me, meant real money, as opposed to the penny an ear of corn would bring – and the labor required to earn it. Geography being destiny, Paramus’ location as the hub of a road network twenty miles from Manhattan ensured that farming would become “passé” (Wells, qtd. in Behnke Paramus xvi) – a situation heralded by the opening of the George Washington Bridge in 1931.

A few years before opening his museum in 2002, Behnke wrote a book entitled Paramus, The Way We Were, 1922-1960. The cover features “one of my proudest pictures … of me as a young man, plowing the fields behind a team of horses. … hard work but I loved it” (Behnke, Paramus xiii). The author considers himself a “Paramus historian by avocation” yet with a broader mission:

In my quest to preserve history I have frequently visited schools and civic and community groups to make my slide presentation. I have also

2 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

The Garden State: “... no rural areas remaining.”

maintained the original Behnke Family Barn as a historical site; over four hundred school children a year come to see it. As they stand in the yard I ell them, “Look around as far as you can see (of course there are houses there now). All of this land was our family’s farm. I show them around the barn and explain all the old tools and implements of farming, including the harnesses for the horses, which did all the work before the tractor was invented. (Paramus xii)

Of his photograph behind the plow, Behnke observes, “I can’t help but feel how odd it is that some of the simple ‘chores’ of yesteryear have become the recreation of today” (Paramus xiii). The repetitive, labor-intensive nature of chore may well carve its own path, according to Freud. Like a wound which does not heal, “The memory of an experience (that is, its continuing operative power) depends on a factor which is called the magnitude of the impression and on the frequency with which the same impression is repeated” (Freud, qtd. in Derrida 201). Freud further observed that “pain leaves behind it particularly rich breaches” (qtd. in Derrida 202).

We sense Behnke’s regret for farming as “the best occupation I have ever held” (Paramus xiii), and his need to come to terms with this loss through his contribution to local history. Is it farming per se or that routine perambulation on the land which is lost? On the other side of the country, Fidel Ybarra, “eleven months retired from forty-four years as a Santa Fe [railroad] section hand” (Least Heat-Moon 231) exhibits a similar intimacy as he sits at his dining table drawing a map for William Least Heat-Moon in PrairyErth:

[Ybarra] draws twin parallel lines across the top that are train tracks and then freehands in curving parallels that are the diverging routes, and he begins talking as he draws in sidings, bridges, the control tower once at Elinor junction, cattle pens, the Strong City hotels…the section hands’ houses there (putting roofs on each one).

The Mid- Atlantic Almanack 3

He labels every item and gives measurements and distances, even the mileposts around Gladstone and Matfield, and he lists the trackman’s tools and defines them: Spike maul—to drive spikesClaw bar—to pull spikesLining Bar – to use to raise track also to line track and other various uses. (233, italics his throughout)

When asked “whether he has driven a spike in every mile of track in the county,” Ybarra responds,

Way more than that. …I could take you out and show you just about every place I drove a spike, and the idea is that it was a hard task, the kind of work you remember. (233-34)

What unites both Behnke and Ybarra in their perception of place is a sense of presence. Their physical investment of hours, days and years of labor in specific natural settings has worn treads. Fidel’s “primitive … first time” map (Least Heat-Moon 236) is a memory of his walking the terrain for decades – as unmediated in its way as explorer García López de Cárdenas’s discovery of the Grand Canyon described in Walker Percy’s essay “Loss of the Creature.” The worst of it is that today’s tourists don’t even realize their “impoverishment” (Percy 54).

In his book, Behnke tells readers that his father, a “jack-of-all-trades” like neighboring farmers, built every building on the farm, where he himself developed the construction skills that would serve him post-farming at the Behnke family-run retail lumberyard, Paramus Building Supply (Paramus xiii). He shows me tools at the museum that family members had personally developed to handle specific farm tasks, such as a patented egg-candling machine (Personal Interview), whereas today Paramus has at least one Home Depot.

The terrain that Behnke knew well enough to map in his head would soon be carved into new roads leading to housing developments, malls, and municipal projects which would necessitate the revision of existing paper maps. The burgeoning

4 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

population in turn created a pressing need for more and organized community services – police, fire, postal, maintenance, newspaper, houses of worship, library and recreation – previously shared ad hoc in a “jack of all trades” farming community (Paramus 73-96). We can see Percy’s “complex distribution of sovereignty” taking root here, where formerly farm co-ops doubled as social centers; sawmills, gristmills, blacksmiths, ice houses, home canning and sewing served farm and family needs; and midwives and home remedies preceded hospitals (see Behnke, Paramus 47-52, 152). “In 1948, five hundred eighty homes were built during what was the height of the residential-building boom in Paramus.” This in a community “sprinkled” with a few 19th or early 20th century farmhouses, whose occupants knew, relied upon, and often even married each other (Behnke, Paramus 163, 142). Behnke is fond of lists; the following were built to handle “the rapid growth of the school-age population during the period 1950-1962”: Memorial School, 1950; Spring Valley School, 1950; Stony Lane School, 1954; Ridge Ranch School, 1954; High School, 1957; Parkway School, 1958; Westbrook Middle School, 1960; Eastbrook Middle School, 1963 (Paramus 69, 67-68).

Behnke centers the list on the page, prefacing it with the comment that returning veterans starting families spurred these and other building projects, which “led to another decline of rural life in town” (Paramus 67). One might poetically see Behnke’s simple list of schools as an epitaph to the way of life he was born into but which was taken from him in his prime of life. The nostalgia, if not regret, is palpable even through his dry style. Hardly on the sidelines, Behnke presided over the Paramus Chamber of Commerce “during the height of Paramus’ development in 1965” (Wells, qtd. in Paramus xvi).

The first two plates of Paramus feature maps of Midland Township as it appeared in 1922, followed by a handwritten list of various farm crops grown in upland and lowland areas (divided by Sprout Brook) and the comment “wonderful hunting in dense woods and brush” available “between farms” (xix). Behnke is keenly aware of the spatial loss; his Preface states, “From working on a farm of over thirty-five original acres, I went into a business

The Mid-Atlantic Almanack 5

occupying only two acres of the original farm” (xii). Selling lumber and construction services, Paramus Building Supply helped transform the terrain the family had once farmed, as well as nearby woods. Recalling the large whitewood trees that once surrounded historic Washington Spring in today’s Van Saun Park, Behnke expresses regret at cutting down one specimen five feet in diameter: “At that time our only thoughts were ‘Boy, what great lumber this tree will make.’ Since the park was built, I can’t help but think of those large trees that stood around the spring. What an attraction these large trees would be today” (Paramus 88-90). One wonders: had the area become a residential development rather than open parkland would the loss have been less visible, Behnke’s remorse lessened?

Roads at least were necessary. Behnke contrasts existing north-south and east-west routes on his 1922 map of Paramus with later “milestones” such as the construction of the George Washington Bridge and subsequent opening of Route 4, “another road that bisected its way through many of the farms in the county to include Paramus, which started the great transition to the areas affected by the new road.” Behnke makes special note of a “first in the nation,” the cloverleaf built in 1937 at the intersection of Routes 4 and 17 (formerly Route 2), whose designers “did not anticipate the huge increase in traffic over the coming years” (Paramus 11).

Of the Garden State Parkway, built in 1956, Behnke observes: This road had an effect on farming families of Paramus such as the Bossolts, the Drenths, and the Konickis. But unlike earlier property owners, they suffered a completely adverse affect – the road bisected their farms without providing access to the parkway or other side of their farms. Therefore, it did not increase the property value. (Paramus 13)

Behnke’s emphasis on a web of named relationships affected by changes to the land forms a contrast to the growth of anonymity fostered by the shopping mall culture that followed the new roads. He recalls that in his youth, “The few family-owned combined grocery and butcher stores in the area were relatively small in size,

6 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

but big in friendship” (Paramus 107). In contrast, The Garden State Plaza Shopping Center “on 198 acres at the intersection of Routes 4 and 17,” The Bergen Mall “built in 1958 on 101 acres,” The Fashion Center “on 35 acres,” and “in 1974, the last of the large centers [Paramus Park Mall] was built on 66 acres in the middle of an area where the old farms were located” (Paramus 106). Whereas today’s consumers value easy highway access to these malls, Behnke highlights the farm acreage consumed and attendant repercussions:

These centers and the individual stores forever changed the rural atmosphere of Paramus in the 1940’s and 1950’s. The stores were initially open seven days a week, which had a pronounced effect on the family-oriented church-going atmosphere of early Paramus. This motivated the Sunday Closing Ordinance. (Paramus 106)

A sense of anonymity permeates our daily trajectories that appears unthinkable even in Behnke’s prime. His words personalize the startling contrasts I discover as I compare local maps from various

periods. For example, the 1876 Walker Atlas of Bergen County features elaborate lithographs of individual Victorian houses on substantial lots surrounded by trees, their owners’ names beneath.

The Mid-Atlantic Almanack 7

Voorhis House

On the aerial view maps I am struck by the clusters of settler family names assigned to large rectangles of land, with little boxes indicating the homes. Much of my own hometown of Teaneck was owned post-Civil War by a wealthy attorney named Phelps who had moved to the area for its country atmosphere (Taylor 47). The roads themselves are mere veins on these early maps, often nameless traces between checkerboards, compared to thicker and more prominent rivers and streams.

In contrast, the 2006 Rand McNally Bergen, Passaic & Rockland Counties Street Guide that I keep in the car privileges roads as boldly colored main arteries, ways of getting me from point A to B as expediently as possible.On map #6389, I have trouble even

locating the Saddle River, a thin blue hairline narrower than nearby Saddle River Road. Our roads occupy more space relative to private property than earlier dirt roads, whose expansion and paving to

accommodate automobiles threatened many a Colonial-era home. In my town, the 18th century Brinkerhoff-Demarest homestead lost its huge kitchen fireplace to the mid-twentieth century expansion of Teaneck Road. That these roads once led to the houses they now truncate or so abruptly abut reveals a “valuation and devaluation” of traces over time (Derrida 231).

Like Freud’s “psychical writing,” maps render concrete and organize “a mass of elements which have been codified in the course of an individual or a collective history” (Derrida 209). In The Power of Maps, Denis Wood states that “knowledge of the map is knowledge of the world from which it emerges – as a casting from its mold, as a shoe from its last – isomorphic counter-image to everything in society that conspires to produce it” (18, italics his throughout).

“I have trouble even locating the Saddle River.”

8 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

Yet maps attempt to conceal this “socially constructed,” even “arbitrary” knowledge by a process of naturalization, of merely representing reality, when in fact it is the “agency of the mapper” constructing a frame which “isolates this view at the expense of another” (Wood 19-24).

In the simplistic explanation of population expansion, individual houses on the 1876 Walker Atlas are exchanged for names on the 1912 Bromley Atlas, which are exchanged for roads on the 2006 Rand McNally Bergen, Passaic & Rockland Counties Street Guide, fostering in the process a greater anonymity. As Wood observes,

... maps are required for us all to keep track of each other. … the specialization required demands a population of the size it permits to function. … This specialization penetrates our consciousness and thereby differentiates us not only from each other, but as a society from those societies whose consciousness remains more whole. … such societies are … less alienated, less caught up in the logics of mapmaking. (38-40)

While Wood refers to societies such as those of native Mexico and Micronesia, we can apply a similar logic to Bergen County less than a century ago, where local merchants routinely extended credit to farmers, where “nobody worked on Sunday,” and where “if you couldn’t get to church or Sunday school, someone would pick you up” (Behnke 152). If this isn’t Norman Rockwell’s America, I’m not sure what is. Yet the population expands:

… inexorably, century after century … what we have is the slow plugging of the holes. It is like watching a computer fill in an outline drawing with color: line by line and pretty soon … none of the white is left. … the map requires and justifies as it records and demonstrates transformations in control over the land. (Wood 46-47)

I am intrigued by one of Wood’s examples: the US Geological

The Mid-Atlantic Almanack 9

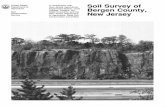

Survey map Wanaque Quadrangle, New Jersey (Wood 80). As a hiker who knows this area of Northwestern New Jersey, I own the North Jersey Trails Two Map Set (nos. 115 and 116), today home to Norvin Green State Forest, Abram S. Hewitt State Forest, and the Appalachian Trail Corridor, but in colonial times a proto-industrial site and “the birthplace of the American iron industry” (Nevins, qtd. in Wood 89). The area was completely stripped of its tree cover for charcoal to feed furnaces, which also accessed abundant waterpower and river transport (Long Pond Ironworks pamphlet 1).

Conversely, to many farm areas undergoing suburbanization, this public land has been allowed to revert to wilderness, preserving traces of industrial archaeology that would otherwise have been subsumed by development. The area is pocked with old mine heads that I have visited as hike “points of interest” (whose map symbols reveal even our supposed topographical map as Wood’s “cultural artifact”); but the re-christened Hasenclever Iron Trail, the colonial-era wagon road linking Ringwood Manor to Sterling Furnace (Frost), remains closed in the vicinity of Peters Mine (operated from the 1760s into the 1940s) due to dumping contamination (not indicated on the map).1

The Long Pond Ironworks Museum in Hewitt, with its restored waterwheels, furnaces, and former company town buildings, is worth a visit today. (Of course, hiking through buggy woods and stumbling across some mineshaft you had no idea was there may well give you a more direct experience, in Percy’s view of all museums as packaging.) Perhaps the most haunting aspect of Long Pond Ironworks today is the surrounding group of relocated and partially restored 18th and 19th century company houses (Self-Guided). Though these unstable buildings are no longer habitable and cannot be visited, their windows have been covered with boards painted with curtained windows, which present a cheerful façade to passing motorists.2

If, as Wood argues, all maps consist of subsumed and amassed cultural capital (48), then flickers of other logics are embedded in the present grids of the Wanaque Quadrangle and Rand McNally Street Guide. Purple areas on the Wanaque Quadrangle show the

10 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

incursion of “urban areas” including subdivisions and new roads, which are not considered “permanent” enough to be named on the map (Wood 81-82). Permanence is an interesting concept with relation to the ever-morphing map; we might better read death. As writing itself mediates between “present and representation” (Derrida 228), so too every map can be read as a sedimented past recorded as having been present – even given a parade of new editions.

Accordingly, I’ve become intrigued with the peculiar negative space historic sites generally merit on road maps – what’s this awkward dogleg on an otherwise straight road? Why is this empty space surrounded by dead-end streets? Like the pentimenti drawings of Renaissance artists, present-day maps reveal an accretion of earlier grids visible only through gaps in the surface grid, anchored by these few sites which remain constants from map to map. The Italian word pentimento, or correction, refers to “the reappearance in a painting of an underlying image that had been painted over,” the ghost reappearing as the later painting becomes transparent with age (American Heritage). Though applied to fine art drawing and painting, the word wonderfully accommodates the accretions of mapping. Not so incidentally here, pentimento derives from the Italian pentire, to repent.

And the map harbors that regret. For the accretions of mapping also bear a striking resemblance to Freud’s depiction of the individual psyche as a “Mystic Writing Pad,” whose conscious surface is ever available to new impressions, but whose substrate of

The Mid-Atlantic Almanack 11

“The map is time becoming space.”

repressed memory, the unconscious, reveals an accumulated depth of writing (Freud, qtd. in Derrida 223-24). Memory as a resistance threatening presence must be repressed, but this repression is never fully successful, just as new map editions fail to erase traces of what came before, though they may obscure its connecting logic. Freud’s “process of stratification” is above all temporal; “the material present in the form of memory-traces … being subjected from time to time to a rearrangement … in accordance with fresh circumstances to a retranscription” (Derrida 206, italics his throughout). Literally, the map is time becoming space.

Superimposing old maps on newer reveals an underlying web of social patterns and an entire economy dating to a time when commuting meant working the fields or taking a sloop down the Hackensack or Hudson to New York City. The cyclical repetition of an earlier habitus becomes particularly evident along transport arteries, the earliest of which were rivers, not roads. Simply following the minor line of the Saddle River north on #6389 of the Rand McNally Street Guide suffices. If I am looking for “systems” to drive places, I do not expect this river to figure prominently on a 2006 road atlas, since as Wood notes, “maps are about relationships” (138-39).

And yet square on the river I encounter a map symbol consisting of a yellow Grecian temple inside a red circle with the text “Red Mill” beneath – in red. Looking at the Rand McNally map legend, I discover that the Grecian Temple symbol means museum, and infer that this was once a working mill using the river for hydropower and transport. The fact that Saddle River Road appears to cross over the river and join Paramus Road at this junction is telling – when Route 4, a major highway, also crosses directly above the Red Mill symbol. If there

The Red Mill, also known as Arcola Tower

12 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

are two bridges so close together, can I infer that the minor bridge was there first? I pursue a process of cryptography here akin to Freud’s oneirocriticism; “dreams generally follow old facilitations” (Freud, qtd. in Derrida 207). What have been repressed on the map are signs of an earlier habitus, which reappear as disembodied symbols (Grecian Temple, Red Mill) keyed to a map legend.

The word habitus is defined as “those aspects of culture that are anchored in the body or daily practices of individuals, groups, societies and nations” (Mauss, qtd. in Wikipedia). One thinks of Behnke riding the plow, or Ybarra walking the tracks – or for that matter, colonial-era miners working the Peters Mine in the Wanaque Quadrangle. My habitus includes weekly commutes to Bergen Community College along Paramus Road, past the site of Behnke’s museum. I turn on a gradually descending cloverleaf to access Route 4 East back to Teaneck. A stone tower in the wooded center of that cloverleaf distracts me as I approach a traffic light where I will turn right on red to merge onto Route 4. The tower is visible only for the fraction of time that I am in the cloverleaf; once I merge onto the highway, it disappears from view.

Eventually I decide to visit the tower, exiting the cloverleaf midway into a cramped parking lot. I get out of the car, a sentence I can’t emphasize enough, and the tower looms before me. I follow a paved walkway that curves down around the structure, and notice wildflowers. There’s a replica of a waterwheel near the tower’s base, and I realize that this was a mill, although it doesn’t look that old. I also notice that the Saddle River runs discreetly under the cloverleaf, banked by a cement walkway. These physical features reveal themselves to pedestrians walking the narrow sliver of Saddle River County Park. Even the river is invisible from a car circling the cloverleaf above.

Further along, a blue historical marker informs me that this was the site of the Red Mill, a “grist mill built 1745; scene of many raids and encounters during the Revolution” (Red Mill). Aaron Burr, George Washington, and Lafayette are all mentioned. Although the marker is within sight of the traffic light where cars idle to enter Route 4, it can only be read on foot. In The Practice of Everyday Life, Michel De Certeau makes the haunting observation

The Mid-Atlantic Almanack 13

that place names “slowly lose, like worn coins, the value engraved on them. … they detach themselves from the places they were supposed to define” (104).

The legend on the blue historic marker demonstrates a “second, poetic geography” of “names that have ceased precisely to be ‘proper’” (De Certeau 105) and are now the province of legend, belief and the authorized version of collective memory, which is history. What makes old maps so quaint is the way in which their signs lie exposed: “…creatures of code with the loss of which they are rendered – like fat – into their constituent components, disembodied signifieds separated from insignificant signifiers. It is the codification in which the sign adheres, nothing else” (Wood 109).

Lest we doubt this authority, the Red Mill figures prominently as a labeled map symbol – the previously-mentioned yellow Grecian temple inside the red disk – as an actual physical location where nearby and more accessible big block stores are excluded. (Garden State Plaza Shopping Center at the intersection of Routes 4 and 17, the only other text in red type on Rand McNally map # 6389, does appear next to a red dot defined in the legend as “Other point of interest.”) Although the Grecian temple symbol is defined as “museum,” aside from the historic plaque nearby, there is nothing else actually signaling museum to me onsite. (Just as I had decided to begin photographing the Red Mill site, the tower was covered in wooden scaffolding, and the replica waterwheel was wrapped in

14 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

Frontal view of the Red Mill

plastic – and so my photographs document this stage. A prominent sign faced cloverleaf traffic entering Route 4 East for months, identifying “Easton Tower” as a historic renovation project.)

A map symbol signaling historic operates as a sign, leading me to expect something grander – fortunately, I had discovered the site just driving by, before locating it on the map. Like Percy’s Spanish explorer discovering the Grand Canyon or his Falkland Islander finding the dogfish on the beach, I had a first encounter with the site which was direct, unmediated, autonomous (Percy 56). Alone, I respond to the aura and develop questions that lead me to further exploration. Incidentally, the map legend “museum” is an example of deconstructing map code:

… should the words mean nothing, the legend is rendered less helpful than the map image itself where the signs at least have a context … [such as the Saddle River] … laboriously we have learned to interpret the architecture of this picture plane. (Wood 98-99)

What I am discovering in my visits to historic sites around Bergen County, my talks with Mr. Behnke, and my perusing of maps, is that the Rand McNally Street Guide is less and less informative to me as I have developed a personal map on the ground, which exposes the superficiality and focus of the road map. On another level [pun intended], it is surreal to picture Mr. Behnke today looking at road signs and asphalt intersections – potential Mapquest destinations – where once he planted crops. When he wrote his book, he had an entirely different “map” in mind, attuned to other spatial/temporal rhythms. For instance, he describes the once panoramic view that existed at the top of then-appropriately named Farview Avenue:

While farmers tilled the soil, I stood on Farview Avenue by what is now our Lady of Visitation Church and watched the Garrett Mountains to the West. To the East I saw the New York skyline, from the Palisades to George Washington and Battery Park. People came from far and wide

The Mid-Atlantic Almanack 15

to see this beautiful view. (Paramus 2)

One feels the pentire of pentimento in Behnke’s words. Perhaps portions of this view are still available from the upper stories of the church built on this inspirational height, but I when I read these words, I recognize an intersection on my daily commute to the community college – the kind of steep hill with light that makes having a manual clutch challenging in winter.

If a few decades make such a difference for a horizon line, we have to work that much harder to extricate the historic site from Percy’s “symbolic complex.” When Paramus’ Red Mill was built in 1745, it would have been the center of a community, a destination for farmers bringing their grain in horse-drawn carts. Now this replica merits a glance out the passenger side car window, almost a “Turnpike moment” (McKibben, qtd. in Quinn 4). The site’s present enclosure in the highway cloverleaf guarantees a reading that isn’t what the heritage society had in mind. Rather, the site speaks to a compression of space and time – the highway entrance marginalizes what was once the pulse of a community, which the driver absorbs in a passing glance, if at all. Experiencing the site fully means deliberately slowing the pace to that of the body, reminding us of the physical space and time we have traversed.

At Behnke’s Museum, I view 19th century photos of the rambling clapboard Red Mill when it was still a working site, having been converted to a woolen mill by the 1830s (Wright paragraph 5). The present stone tower appears separately in a bucolic early 20th century photo as the “Arcola Mill” along the Saddle River, and as the subject of several landscape paintings. I stare at this tranquil millpond setting and dirt road, trying to reconcile it with today’s stone tower wrapped in the cement cloverleaf. It feels strange to be upset about something that happened here when my parents were still children in their respective foreign countries.

16 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

Red Mill on the Easton Estate

It is precisely the décalage of the cement cloverleaf wrapping (with the presentation “package” of the blue historical plaque) that liberates my “sovereign discovery of the thing.” Having recently returned home to New Jersey after seven years abroad, I am indulging in Percy’s “dialectical savorings of the familiar as the familiar” – which turn out to be quite foreign after all (Percy 48). The long absence and the chance encounter make of me a “sovereign wayfarer,” seeing through new eyes.

“[A] history can be grasped only in the very inaccessibility of its occurrence,” argues Cathy Caruth in Unclaimed Experience (18). As trauma can never be “fully perceived as it occurs,” so too “events are only historical to the extent that they implicate others” (18). It was through the sale of farmland that the house in which I grew up was built, and the houses on either side, and across the street. However much space existed, there would have been no room for my southern European immigrant parents, working commuters to Manhattan, in the Bergen County farming communities of long ago.

“[T]he understanding of one’s own national identity has taken place through the forgetting, and obliteration, of the other” (Caruth 48). There is a necessary violence here, a “breaching” poorly commemorated by the two-dimensional historical plaque, the red-and-yellow map symbol. Let us turn instead to three items discovered by Mr. Behnke “in assembling dates for the history of Paramus”:

The first is a bill from the civil engineer and surveyor, Joseph H. Molloy, who lived on Farview and Pleasant avenues in Paramus. The bill was addressed to my father and dated June 19, 1939. It was for services rendered to survey 0.744 acres on the east side of Farview Avenue. The bill was for twelve dollars, and the land in the survey was a three-quarter acre site next to the Visitation Church, which was sold to Walter and Anna Frank at the time for nine hundred dollars.

The second item was a program for the First Annual Entertainment and Dance given by the Farview Avenue

The Mid-Atlantic Almanack 17

Taxpayers Association on April 24, 1926. The ticket cost was fifty cents for adults and twenty-five cents for children. Professor Jean Irving and radio celebrities sang and provided entertainment. It was an entirely different world.

The third item is the complete detailed brochure of the Easton Estate, a sixteen-page booklet with pictures and information about the property; this estate was put up for sale after the death of Mortimer Easton. Call their phone number today, HACK-1881, to get more information. (56)

As it turns out, the tower wrapped in the cement cloverleaf was built by a Mr. Easton, the founder of Columbia Gramophone Company. Behnke tells us that the picturesque “water mill” of early photographs and paintings was used as a “pumphouse” to water “twenty-six acres of lawns, pond, fountain areas, and formal gardens” (Paramus 31) on an estate of over fifty acres purchased by Easton, near where the original [Red] mill had stood until 1894 (Bogert 90). His son “put Paramus on the silent silver screen. … from 1910 to 1920 the Easton home was a scene for Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks ‘romances,’ Fatty Arbuckle comedies and D.W. Griffiths directorial triumphs.” Post-Red Mill, artifice extends to the picturesque renaming of this site:

The senior Mr. Easton gave the area the name of ‘Arcola’, taking it from a town in Italy where Napoleon had a great victory. Whether Easton admired Napoleon or chose ‘Arcola’ because the original was near another Italian town called ‘Lodi’ has not been recorded.3

I have to laugh at the arbitrary nature of local history and its simulacra, thinking of the authoritative blue Red Mill historical plaque, which if idling motorists could only read it, tells a different story. On a more serious note, bucolic pre-Route 4 photographs and paintings demonstrate dramatically how the Red Mill site has been marginalized, rendered interstitial by transportation arteries

18 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

surrounding and bypassing it (Lefebvre 164-165).4 According to Behnke, “The water mill, which was located

on [Easton’s] property, has been relocated by the county and is still a historical landmark in the area” (Paramus 31). It apparently didn’t travel far, but having outlived its various careers – as colonial gristmill, Civil War woolen mill, estate pumphouse, plein air painting subject – the Red Mill aka Arcola or Easton Tower now fulfills some mythos, if not quite that of “museum” then surely as “point of interest” – a revelation of Kant’s permanence, succession and simultaneity compressed into one point on the map (Kant, qtd. in Derrida 225).

While I must “zoom in” by getting out of the car to appreciate the Red Mill and even the Saddle River today, “zooming out” has its merits. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection aerial photographs of the Red Mill area in 1930 and a lifetime later, in 2002, form as dramatic a contrast as the Walker Atlas and the Rand McNally Street Guide. The former Red Mill’s presence explains the awkward three-leaf clover of the Route 4/ Paramus Road interchange, fulfilling that peculiar negative space historic sites seem to occupy. The irregular fourth “leaf” or jughandle containing the Arcola Tower is present in the lower left quadrant of both aerials. The jughandle was also the site of the picturesque millpond, still visible on the 1930 aerial.

The pentimento of an earlier route over the Saddle River is revealed from above by a small bridge in the jughandle, whose elaborate stone parapets were designed for pedestrians taking in the now-vanished millpond view. Today there is no safe room for pedestrians on the roadway. The parapets are blocked by waist-high metal guardrails that I was forced to climb to photograph the tower from the bridge, which today seamlessly forms part of the descending cloverleaf to Route 4.

Absent from the 1930 aerial are acres of grey asphalt in the form of widened highway, secondary roads and parking lots where once were farmer’s fields and estates like Easton’s. More prominent in the 1930 image are tree-lined roads and scattered dense woods. Orienting the viewer, a meandering yellow line roughly follows the Saddle River’s course in both aerials, though northwest of Route 4,

The Mid-Atlantic Almanack 19

the river’s course appears to have been adjusted post-1930 to allow for the widening of Paramus Road. A thin dark line which Behnke guesses to have been a fence runs roughly parallel to Route 4 in the 1930 image (Telephone Interview). The pair of photographs – taken a lifetime apart – testify to a multiplication of roads superseding river, as well as to the dramatic shift from agricultural production to office space and the malls Paramus is now known for.

Can we speak here of a shift from the concrete to the abstract, of farmers selling their land only to be trapped in a grid? (Poulantzas, paraphrased in Soja 129). As David Harvey observes in The Condition of Postmodernity,

It is hardly surprising that the artist’s relation to history … has shifted, that in the era of mass television there has emerged an attachment to surfaces rather than roots, to collage rather than in-depth work, to superimposed quoted images rather than worked surfaces, to a collapsed sense of time and space rather than solidly achieved cultural artifact. (61)At the Behnke Museum, I look at old photographs of buildings that haven’t existed for decades. No building is next to any other building – they’re all front and center, with gravel drives, surrounded by large trees. The expansive space and isolated quality of the buildings makes me think of the ways in which physical space impacts many aspects of our lives – our daily routine, our perceptions, and especially our mental space. Clearly, the space of frontier or boundary – river, tree, forest, field – plays “a mediating role” (De Certeau 127).

It has been decades since any great expanse of nature in Bergen County has been referred to as “the meadows” or “the woods,” although there was such a time, judging from Behnke’s account of hunting “between farms.” Burgeoning population density and decreasing physical distance have played roles in the development of my own town, Teaneck, from its colonial-era roots to the present, though not as dramatically as mall consumption – that stimulation of desire – replacing the self-sufficiency of farm

20 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

production in Paramus. That an expansive sense of space, time and wild nature once existed in New Jersey has been a revelation in broad daylight, while also provoking a curious sense of loss.

“History is experienced as nostalgia, and nature as regret – as a horizon fast disappearing behind us,” writes Henri Lefebvre in The Production of Space (51). As I think of Mr. Behnke savoring the lost panorama from Farview Avenue or pedestrians admiring

the vanished millpond from the small stone bridge, I acknowledge that the horizon is alterable. I am standing before a painting in the Princeton Art Museum entitled View of New York from New Jersey, dated 1857. The hilly fields of what is perhaps Weehawken yield to an expanse of Hudson River across which the few church spires of Manhattan Island disturb the broad expanse of sky, land, and water. As physical space is usurped by virtual, screen space, the concrete acquires that aura of nostalgia.

On a visit to the 18th century Van Riper-Hopper House Museum in nearby Wayne, NJ, I am struck by the crude wooden sabots of varying size lined up by the hearth. These amusingly clunky clogs would have been very practical in the muddy environs of the farmhouse. If the environment spawns its tools, then our iPods and Blackberrys are as much a product of our vastly reduced social and physical spaces as these clogs were of their Jersey Dutch society. Putting ourselves in their shoes, as it were, we comprehend that the bodily link between physical space and time – the time it

The Mid-Atlantic Almanack 21

View of New York from New Jersey by John Henry Hill

takes a person to walk a mile – has been rendered almost irrelevant, although our bodies have not evolved. By extension, where the Red Mill’s millwheel and stone once harnessed the Saddle River to humbly grind grain into flour, the Hoover Dam now harnesses the Colorado River to power that “City of Lights,” Las Vegas.5

“Ruins,” writes Harvey, “helped ground our identity in a rapidly transforming world” (272). Yet it is as much their awkward location as the buildings themselves which attracts me. The real ruins here are the traces of original transport arteries, or to use the warmer, more body-oriented word, of an earlier habitus. River as road, millpond as hydropower – they are still with us, but they are vestigial, marginal – recreational. We have risen above geography as transport and destiny, in a quite literal way.6 Yet as we channel along the NJ Turnpike, searching for our exit far above and divorced from the Meadowlands below, our channeled mindset is also the product of this abstraction. As an avid hiker, I can testify to the acting out of the itinerary on the ground versus the abstractness even of the topographical map.7

Experienced in pedestrian mode, old roads can be the most powerful of ruins, the phenomenology of “being there” testifying to this former habitus. In my hometown, Teaneck Road skirts the northernmost part of the New Jersey Meadowlands, for decades synonymous with environmental degradation, now in hopeful recovery. To read old accounts of sport fishing and hunting, of salt hay harvesting in these same meadowlands, is truly to experience Lefebvre’s pangs of nature as regret, as that horizon fast disappearing.

22 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

Replica of Clogs at Van Riper-Hopper House

Teaneck Road intersects with DeGraw Avenue, which channels traffic directly onto the major interstates 80 and 95, where once were meadows. But walking a block further along Teaneck Road, near the Dairy Queen, I turn left down to what remains of the meadows and encounter another road now barred to vehicles, abandoned. A sign proclaims this a Bergen County Park, but there are no amenities. On the Rand McNally Street Guide, this pentimento backs into grid-free stippled green space signaling undeveloped, but tracing a finger across Overpeck Creek reveals Fort Lee Road climbing the Palisades in the neighboring town of Leonia. This dead end was once part of a main road through the meadows for an earlier generation of commuters by rail and ferry. The white concrete slabs are cracked, revealing earlier cobblestones. Telephone poles march alongside, festooned with vines.

The road continues for a quarter mile, and walking it is surprisingly relaxing, as though with the detour I have somehow detached myself from the present. No cars pass, no traffic lights blink. Birds call in the trees, cicadas buzz. Teens have carved dirtbike tracks through the reeds to one side; an acquaintance tells me that he used to party here in high school. This appendix of Fort Lee Road has been transformed into “delinquent,” interstitial space, attracting wild life of all sorts who want to get offroad and off the grid for awhile.8 Once again a frontier, “a mediating space,” it has potential for planned or random rendezvous and encounters, which renders it slightly threatening – as a frontier should.9 At the same time, Nature is reclaiming this Road to Nowhere, which ends

The Mid- Atlantic Almanack 23

Road to Nowhere

abruptly in a thicket, through which we hear the rush of traffic on the perpendicular Interstate 80.

I meditate on the Road Once Travelled and ultimately abandoned, a casualty of large public transport works overtaking local habitus. And I think of Mr. Behnke, patiently explaining farm tools, whose uses have long been obsolete, to a group of schoolchildren standing in his former barn. If “materiality is precisely that which translation relinquishes” (Derrida 210), can a museum exhibit or a map convey the depth of his mission when he is no longer there to animate them? In our landscape, this abstraction is apparent where pentimenti – Teaneck’s Fort Lee Road remnant, Paramus’ Red Mill – appear in marginal zones on the present grid, signifiers of the space and time we have traversed.

Notes

1I was given the Hasenclever Iron Trail pamphlet at the Long Pond Ironworks Museum in the summer of 2006, and told that sections of the trail remain closed to hiking due to contamination. The deeply rutted colonial wagon road is clearly visible, especially on hills.

2 The cheery façade belies a rumor that tenants were evicted from these houses in the 1970s.

3 Local newspaper article, author and provenance unknown, paraphrases Bogert’s account of the Easton Estate in more colorful language. The unknown journalist has a way with words which I cannot resist.

4We can argue that the Red Mill site becomes an example of Lefebvre’s

“dominated space,” “closed, sterilized, emptied out” space which has been rendered interstitial, almost null and void, often by transportation arteries which violate its integrity. An extreme example of this “pulverizing” spatial trend would be Gordon Matta-Clark’s mid 1970s project, “Fake Estates,” in which Clark purchased interstitial, uninhabitable and even inaccessible parcels of land in NYC boroughs.

5Parallel between millstone grinding wheat and Hoover Dam powering Las Vegas courtesy of Steven Weigl, Bergen County Historical Society Librarian, Felician College, Lodi, NJ.

24 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

6Witness the extraordinary elevation of the NJ Turnpike above the Meadowlands in the vicinity of Snake Hill, Exit 15X, once the highest point in the marshes, now quarried half to oblivion and lower than the Turnpike.

7See De Certeau’s discussion of the tour versus the map, acting versus seeing: “the relation between the itinerary (a discursive series of operations) and the map (a plane projection totalizing observations), that is, between two symbolic and anthropological languages of space,” and the way in which they have become increasingly dissociated over time (119-122).

8If the specific mark [of the delinquent] is to live not on the margins but in the interstices of the codes that it undoes and displaces, if it is characterized by the privilege of the tour over the state, then the story is delinquent. Social delinquency consists in taking the story literally, in making it the principle of physical existence where a society no longer offers to subjects or groups symbolic outlets and expectations of spaces (De Certeau 130).

9De Certeau speaks of the frontier as a “third element,” “a space between” and at the same time a fruitful space of “crossings” and “bridges.” “… the frontier is a sort of void, a narrative symbol of exchanges and encounters.” Once this space is built upon, becomes “an established place,” he finds that its potential is diminished even for the builder, who escapes in search of another frontier (De Certeau 127-128).

Works Cited

Arcola Mill, photograph. Anon. Collection Fritz Behnke Historical Museum, Paramus, NJ. Undated.

Arcola Mill, oil painting. (Artist name undistinguishable.) Collection Bergen County Historical Society, early 20th century. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Fourth Edition,

Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000. 1 Feb 2008 <www.thefreedictionary.com>.

Behnke, Fritz. Personal interview and tour of Behnke Historical Museum. Paramus, September 2007.

---. Telephone Interview regarding NJDEP aerial photograph of 1930. June 16, 2008.

The Mid-Atlantic Almanack 25

---. Paramus: The Way We Were 1922-1960. Shippensburg, PA: Companion Press, 1997.

Bergen, Passaic & Rockland Counties Street Guide. 1st Edition. Chicago: Rand McNally, 2006.

Bogert, Frederick W. Paramus: A Chronicle of Four Centuries. Paramus: Paramus Free Public Library, 1961.

Bromley, George W. and Walter S. Atlas of Bergen County, New Jersey. Philadelphia: n.p., 1912.

Caruth, Cathy. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative and History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1996.

De Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Vol. 1. Trans. Steven Rendall. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984.

Derrida, Jacques. “Freud and the Scene of Writing.” Writing and Difference. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1978. 196-231.

Frost, Paul. Hasenclever Iron Trail (pamphlet). Hewitt, NJ: Friends of Long Pond Ironworks, n.d.

Harvey, David. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry Into the Origins of Cultural Change. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1989.

Hill, John Henry. View of New York From New Jersey. 1857, American, oil on canvas, Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ.

Least Heat-Moon, William. “En las casitas.” PrairyErth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991. 230-236.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers, 1992.

Long Pond Ironworks National Historic Landmark (pamphlet). Hewitt, NJ: Friends of Long Pond Ironworks, n.d.

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection aerial photographs, Route 4 and Paramus Road Interchange, 1930 and 2002. Courtesy Bob Monacelli, Wayne Historical Commission.

26 Metaxatos: Bergen County, NJ

North Jersey Trails. Two Map Set nos. 115, 116. 8th edition. Mahway, NJ: New York-New Jersey Trail Conference, 2007.

Percy, Walker. “The Loss of the Creature.” The Message in the Bottle. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2000. 46-63.

Quinn, John R. Fields of Sun and Grass: An Artist’s Journal of the New Jersey Meadowlands. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1997.

Red Mill – Paramus Historical Marker. The Historical Marker Database. 9 June 2008 <http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=837

0&Result=l>.

Self-Guided Tour of Long Pond Ironworks Historic District. (pamphlet). Hewitt, NJ: Friends of Long Pond Ironworks, n.d.

Soja, Edward. Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory. New York: Verso, 1989.

Taylor, Mildred. A History of Teaneck. Teaneck American Revolution Bicentennial Committee. 1977.

Walker, A. H. Atlas of Bergen County, New Jersey. Redding, PA: Redding Publishing, 1876.

Wikipedia. 27 Sept 2007 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki.Habitus>.

Wood, Denis. The Power of Maps. New York: Guilford Press, 1992.

Wortendyke Barn Museum Exhibit Plaque. Park Ridge, NJ 1997-98.

Wright, Kevin. “Red Mill and its Haunted House,” Bergen County Historical Society. 1 Nov 2007 <http://www.bergencountyhistory.org/Pages/ redmill.html>.

The Mid-Atlantic Almanack 27