Bengali cinema: an other nation , by Sharmistha Gooptu

Click here to load reader

Transcript of Bengali cinema: an other nation , by Sharmistha Gooptu

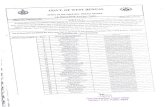

This article was downloaded by: [University of Chicago Library]On: 15 November 2014, At: 20:02Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

South Asian History and CulturePublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsac20

Bengali cinema: an other nation, bySharmistha GooptuSangita Gopal aa Department of English , University of Oregon , Eugene, OR, USAE-mail:Published online: 21 Jun 2011.

To cite this article: Sangita Gopal (2011) Bengali cinema: an other nation, by Sharmistha Gooptu,South Asian History and Culture, 2:3, 452-455, DOI: 10.1080/19472498.2011.577583

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2011.577583

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

452 Book reviews

that allowed for greater upward social mobility among African captives than in Christianlands is important. A Malik Ambar would have been unthinkable in Christian-held lands.However, a more nuanced analysis could have been offered here. A clearer overview of therole of Islam in the region would have been helpful at the beginning of the book.

Undoubtedly, the overriding strength of African Identity in Asia is in bringing togetherthe various threads of research that have been published on the topic of the AfricanDiaspora in Asia. The archival research and fieldwork that scholars have undertaken overthe last 30 years (involving over a dozen different languages) has allowed for a rich holisticoverview of the dispersion and contributions of Africans in South Asia. There is growinginterest in this African Diaspora. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture ofthe New York Public Library, for instance, is currently exhibiting quilts by Siddi womenand is launching an online exhibit featuring an overview of this African Diaspora in SouthAsia, with dozens of historical and contemporary images of Africans and their descendentsin the region. This attention will undoubtedly help bring new perspectives to the same,while expanding the understanding of the African Diaspora for both scholars in South Asiaand those of the African Diaspora in the Atlantic world. Shihan de Silva Jayasuriya’s bookcontributes well to these ongoing efforts.

Omar H. AliAfrican American and Diaspora Studies, University of North Carolina,

Greensboro, NC, USAEmail: [email protected]

© 2011, Omar H. Ali

Bengali cinema: an other nation, by Sharmistha Gooptu, Abingdon and New York,Routledge, 2011, 248 pp., $140.00 (hardcover), ISBN 978-0415570060

Sharmistha Gooptu’s Bengali Cinema: An Other Nation provides one of the most com-prehensive histories of Indian cinema, from the early years of the twentieth century to the1980s. This meticulously researched and subtly argued book uses the history of Bengalicinema to shed light on some of the most interesting questions in Indian film studiestoday: What constitutes a national cinema and does only the Mumbai-based Hindi com-mercial cinema deserve to be viewed as such? What are the stakes of designating films inother Indian languages such as Tamil, Telugu and Bengali as ‘regional cinema’, where aregion is considered a subset of the nation? Does the nation/region distinction hold whenthese so-called regional cinemas construct an alternative imaginary in order to distinguishthemselves from a range of other cinemas including Hindi cinema and the products ofHollywood, and when this imaginary is sustained across other conventional divisions like‘mainstream’ and ‘art’ cinemas? Alternatively, can categories like national/regional bepreserved when these cinemas inhabit industrial structures that are allied and overlappingand often address the same spectator using representational strategies that are often sim-ilar? This work is a worthy addition to an emerging body of scholarship including workslike Cinemas of South India: Culture, Resistance, Ideology (edited by Sowmya DechammaC.C and Elavarathi Sathya Prakash) and Tamil Cinema: The Cultural Politics of India’sOther Film Industry (edited by Selvaraj Velayutham) that seek to challenge the politicaland cultural hierarchies evoked by categories like ‘nation’ and ‘region’.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

hica

go L

ibra

ry]

at 2

0:02

15

Nov

embe

r 20

14

South Asian History and Culture 453

The study commences in the 1920s by which time cinema-going had become afavourite leisure activity in the city of Kolkata (then called Calcutta), especially amongits educated, middle classes, that is, the bhadralok. As Gooptu notes, an unusually largepercentage (up to 75%) of the film-going audience in Kolkata comprised the bhadralokincluding the elite upper classes, students, and even the ‘genteel’, if impoverished, gov-ernment clerks. In comparison, the proportion of the ‘educated’ classes frequenting thecinema in Mumbai and Madras was 50% and 40%, respectively. This statistic, as Gooptu’sargument shows, becomes very significant as Bengali cinema in the coming decades seeksboth legitimacy and distinction by positing itself as a bhadra (cultured) form of leisure. Ata time when film’s sensory enticements and its democratizing potential was viewed withconsiderable suspicion among the colonial elite, Gooptu contends that the Bengali intelli-gentsia, who frequently wrote on film in various journals, approached this new medium asone ‘that held the prospect of internationalism and universalism – both key tropes in theBengali intellectual imaginary since the end of the nineteenth century’ (p. 43). Regardlessof what type of films were actually produced and consumed, Gooptu demonstrates that ‘theBengal school’ of Indian cinema emerged by advocating film as an art form, capable ofconferring aesthetic satisfactions and cultural distinctiveness. She then tracks how Bengalientrepreneurs deployed this ideal in order to differentiate themselves from ‘non-Bengali’film production companies like Madan Theatres. In the following chapter on New Theatres,one of India’s pre-eminent film production and distribution companies in the 1930s and1940s, Gooptu links the rise of a fiscal mode that buttressed the aesthetic protocols of thebhadralok cinema. New Theatres’ perfected a brand of ‘good cinema’ (refined, literary)and successfully exported it to other parts of the country. Her account of the emergenceof Bengali cinema as a ‘national brand’ indeed challenges the more familiar narrative ofHindi cinema being the template for the ‘All-India’ film.

The section of Gooptu’s study focused on the pre-Independence period (i.e. 1920s to1947) asks us to think dialectically about the moniker ‘Bengali cinema’ for she shows thatthis term does more than describe films in a particular language that may reflect the culturalvalues of a region; it constructs – over time – a distinct identity and a repertoire of culturalassertions that are then named ‘Bengali’. Cinema emerges in her account as a key sitefor working through and putting into circulation ‘Bengaliness’ as an ‘order of difference’.This difference, she intriguingly suggests, is precisely what enables a regional cinema toestablish a contiguous (rather than a subsidiary) relation to the nation and provides culturalcohesion to a region at a time of great economic and social change. If the ‘Bengal school’had a national presence in the pre-Independence era, after 1947 the nature and function ofthis brand shifted. Owing to a number of factors including the Partition (whereby Bengallost a huge section of its film market to East Pakistan, now Bangladesh) and the hyper-capitalization of the film industry in Mumbai, post-Independence Hindi cinema assembledsomething close to an All-India market. Bengali cinema turned ‘inwards’ but by doing so,it consolidated a localized product that was able to resist the onslaught of Hindi cinemathrough the next two decades. In other words, Bengali cinema far from being subsumed bynational cinema became regionalized and resilient, thus entering its ‘golden age’.

In the chapters that analyse the extraordinary power of the star-duo Uttam Kumarand Suchitra Sen and the screen persona of the comedian Bhanu Banerjee (who oftenplayed the witty ‘bangal’ or the person from East Bengal), Gooptu shows the differentmeans through which Bengali cinema forged a flexible idiom which both referenced theupheavals that Bengal was going through at this historical juncture and reinforced theBengali bhadralok culture as a bulwark against change. The Uttam–Suchitra melodramasvisualized a quintessentially Bengali form of romantic deportment through the bodies of

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

hica

go L

ibra

ry]

at 2

0:02

15

Nov

embe

r 20

14

454 Book reviews

these two very appealing stars. The relatively greater sovereignty available to the roman-tic couple in the Bengali melodramas of Uttam–Suchitra (as opposed to the Hindi filmwhere the romantic couple is invariably framed by the patriarchal family) helped delin-eate a Bengali modernity. While these melodramas referenced a sophisticated ideal and afrequently upper-middle class milieu, the comedies starring Bhanu Banerjee were firmlyembedded in the trials and tribulations of the quotidian. As such they referred to – withinthe generic conventions of comedy – the stresses of urban life in Kolkata, including unem-ployment, a crumbling infrastructure and overcrowding created by a huge influx of refugeesfrom East Bengal. Banerjee – who often played a resourceful bangal – used comedy to raiseand resolve many of the cultural tensions roiling post-Partition Kolkata. In these chaptersGooptu carefully delineates how Bengali cinema as a modern, industrial product is bothaligned with several broader trends of Indian commercial cinema in the 1950s and 1960s,including the collapse of the studio mode of production and the rise of the star system, andyet localized in its idiom, image and address.

The book moves from these popular films of the golden age to the cinema of SatyajitRay, that auteur par excellence, whose films, commencing with Pather Panchali (‘Song ofthe Road’, 1955) put Indian cinema in the global art circuit. Though it is well known thatRay had scant regard for Bengali commercial cinema, it is also true that Ray’s main domes-tic market was Bengal since his films were hardly distributed widely in the rest of India.Gooptu shows that not only many of his films are deeply localized in terms of mise-en-scène and gestural/performance idioms – she takes as a telling example the early comedyParash Pathar (‘The Philosopher’s Stone’, 1958) – but also that they include ethnographicdata that remain untranslated and thus legible mainly to the Bengali viewer. Taking herplace in an ongoing attempt to reframe the cinema of Satyajit Ray – Moinak Biswas’s editedvolume Apu and After: Re-Visiting Ray’s Cinema and Keya Ganguly’s Cinema, Emergenceand the Films of Satyajit Ray – Gooptu reclaims Ray as a Bengali film-maker. Through anexamination of his reception in Bengal, she shows that Ray’s international success broughtto fruition what the earliest writers on cinema had recognized to be the medium’s poten-tial to transport Bengali culture beyond its regional boundaries. The book’s final chapterincludes a suggestive – though somewhat truncated – account of the exhaustion of Bengalibhadralok cinema in the 1970s and 1980s in the wake of the disappearance of this cinema’surban middle-class base, and a dissipation of the cultural ideals of ‘Bengaliness’ that hadanimated it.

Gooptu’s book provides a richly layered and fluently written account of the centraltendencies in Bengali cinema. Its strong narrative arc makes for a very pleasurable read.While it is conventional to speak of commercial cinema in India, particularly in the pre-liberalization era, as a form addressed to the masses, the book’s singular achievement is toshow that this is not necessarily the case in Bengal. Owing perhaps to Bengal’s historicalinvestment in modernity, cinema here emerged as a middle-class pursuit, attached to awider literary culture. Based on a carefully assembled, wide-ranging archive of sources,the book provides us glimpses into many hard-to-find films. One yearns, however, to learnmore about the aesthetic forms assumed by bhadralok cinema. How indeed did Bengalicinema convert a ‘good story’ into cinematic narrative? How did the mise-en-scène andcinematography visually code the ‘non-commercial’ ideology of Bengali cinema? Whatinflection did Bengali cinema put on melodrama? How did the look and feel of this cinema,its visual and aural coordinates contribute to our apprehension of this ‘other nation’?

In the Author’s Note that concludes the book, Gooptu explains why certain film-makers – most strikingly – Ritwik Ghatak but others like Mrinal Sen, Goutam Ghosh andBuddhadeb Bhattacharya have not been included in this account of Bengali cinema. Simply

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

hica

go L

ibra

ry]

at 2

0:02

15

Nov

embe

r 20

14

South Asian History and Culture 455

put, these film-makers had little investment in the cultural ideals that has animated Bengalicinema as a bhadralok aesthetic and enterprise. Their films document rather the hollowingout of this ideal and all the other subjectivities that it excludes. Not only certain film-makers, but certain genres – mythologicals, historicals, horror – are outside its purview.This book’s masterful chronicling of bhadralok cinema in its social, cultural and politicalcontexts actually provides us with a great foundation for exploring what lies outside it.

Sangita GopalDepartment of English, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA

Email: [email protected]© 2011, Sangita Gopal

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

hica

go L

ibra

ry]

at 2

0:02

15

Nov

embe

r 20

14