Abstraction Matters -...

Transcript of Abstraction Matters -...

Abstraction Matters:

Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words

Edited by

Cristina Baldacci, Michele Bertolini, Stefano Esengrini and Andrea Pinotti

Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words Edited by Cristina Baldacci, Michele Bertolini, Stefano Esengrini and Andrea Pinotti This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Cristina Baldacci, Michele Bertolini, Stefano Esengrini, Andrea Pinotti and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-1810-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-1810-0

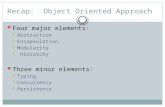

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... viii Andrea Pinotti Part I. Sensation Introduction ................................................................................................. 2 Michele Bertolini Chapter One ................................................................................................. 5 Abstraction in Noguchi’s Own Words: In Search of Permanence Clarissa Ricci Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 19 Yves Klein: All that is Solid Melts into Air Filippo Fimiani Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 32 Gianni Colombo: A Critique of Perception in a Mobile World Anna Detheridge Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 44 To Whom it may Concern: Richard Serra and the Phenomenology of Intransitive Monumentality Andrea Pinotti Chapter Five .............................................................................................. 59 Matthew Barney: The Semiotic Sculptural Body Angela Mengoni Part II. Idea Introduction ............................................................................................... 70 Stefano Esengrini

Table of Contents

vi

Chapter Six ................................................................................................ 73 Vision, Perception, Openness: David Smith’s New Sculpture Stefano Esengrini Chapter Seven ............................................................................................ 84 The Simplest Image: Tony Smith’s “Cubes” Georges Didi-Huberman Chapter Eight ............................................................................................. 95 Donald Judd’s Specificity Elio Grazioli Chapter Nine ............................................................................................ 102 The Experience of Sculpture in Robert Morrisʼs Notes on Sculpture Michele Bertolini Part III. Language Introduction ............................................................................................. 116 Cristina Baldacci Chapter Ten ............................................................................................. 120 Impossible Objects: On Francesco Lo Savio’s Metals Riccardo Venturi Chapter Eleven ........................................................................................ 135 “Sculpture is Matter Mattering”: Spatialization of Matter and Visual Poetry in Carl Andre Giuseppe Di Liberti Chapter Twelve ....................................................................................... 146 Tensional Creation: Luciano Fabro’s Sculpture between Conceptualism and Abstraction Davide Dal Sasso Chapter Thirteen ...................................................................................... 158 “Language to be Looked at and/or Things to be Read:” Language as a Sculptural Material in Robert Smithson Cristina Baldacci

Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words vii

Chapter Fourteen ..................................................................................... 168 Joseph Kosuth and The Play of the Unmentionable David Freedberg Abstracts .................................................................................................. 179 Contributors ............................................................................................. 186

PREFACE

ANDREA PINOTTI Terminology in art theory, art history and art criticism appears to suffer from a chronic condition. Many of the fundamental notions and concepts that structure theoretical, historical and critical discourse are felt to be strongly inadequate because of their vagueness, polysemy, or the heavy semantic burden they bear from a century-long tradition, overloaded with its ideological and cultural prejudices. Yet despite all the comprehensive debates aiming to reject terms and substitute them with more proper designations, the language of the scholarly community – let alone everyday language – ends up returning to these keywords time and time again, forced to accept their indispensable role for research and interpretation.

Paradigmatic examples of such controversial terms are the notions of “form” and “style”. Meaning both the perceivable phenomenon and the invisible structure, the image and the idea, “form” can be opposed both to content (subject) and to materiality. When opposed to content, form can absorb in itself material factors as well; when opposed to matter, it can be employed to identify the subject. As regards “style” (frequently associated with form), it can refer to a principium individuationis, that which makes every work by Picasso specifically “Picassian”. But it can also function as a principium dividuationis, enabling us to gather Picasso, Braque and other artists under one and the same general label, “cubism”. Moreover, style is deemed a positive character when a person or a work has style; a negative one, when something is in a style (implying it is just imitative). Notwithstanding all the ambiguities of these notions, and the repeated efforts to amend them or even get rid of them, they seem more alive and kicking than ever.

“Abstraction” does not lag behind in this respect. A major problem seems to concern the preposition “from” that we always – either implicitly or explicitly – pronounce when employing the term. When we abstract (in any thought process, both in intellectual activities and in everyday experience), we abstract-from a series of elements that nevertheless belong to the object we are considering: from its weight, its form, its material and its dimensions, if we are, for example, focusing on the colour of a certain

Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words ix

thing. But this way of conceiving abstraction ultimately makes it dependent on the total object of which we decide to investigate only one single aspect.

If we transpose this argument to the domain of visual arts, such a conception of abstraction would let in through the back door that which had apparently left through the front: the model or the external referent “from” which this or that particular property would be abstracted in order to obtain an abstract picture. But this is “stylization” much more than “abstraction”. This is why alternatives such as “non-objective (German gegenstandslos)”, non-representational and non-figurative, have been put forward to avoid this relapse into the paradigm of traditional figuration. And still, abstraction resists. Instead of fighting against this term, we had better be critically aware of its possible misunderstandings, and of its deep implications.

What should abstraction consist of, once it is emancipated from the preposition “from”? Not of the iconic restitution of an already given reality, but of letting something come into being that can exist for the first time and only in that image. In this perspective, creation, invention, and all the cognate terms that art theory and history have elaborated over the centuries in order to characterize artistic production take on a new sense.

At the same time, together with the preposition “from” associated with the expression “abstraction-from”, another preposition is radically questioned by this process. It is the preposition “of”, implicitly or explicitly pronounced when we speak of an image as of an iconic representation “of” something that exists before being represented by that image and continues to lead its autonomous existence. The German term for “model”, Vorbild, effectively illuminates the status of the model, which stands “before” (vor) the image (Bild) both in the spatial and in the temporal sense. Once we have understood it in its emancipation from the “from”, abstract art challenges a millennia-old tradition that might be called for the sake of brevity “Platonistic”: a tradition based on the idea that visual arts perform an iconic rendition of a model which is ontologically and gnoseologically superior to the rendition itself. A human being represented in a portrait or a piece of nature depicted in a landscape painting are entities independent from their being rendered by an image, which possesses less being and less truth than the model. The extent of being and truth of the image on the contrary depends on its being able to approach in a more or less faithful manner the external referent.

The claim of the ontological and gnoseological inferiority of the image with respect to the model constitutes the core of Plato’s doctrine of mimesis as exposed in Book 10 of The Republic. As is well known, its

Preface

x

author drew unfavourable consequences for artists: much like the sophists, they were to be banned from the ideal state for producing apparent realities and illusory knowledge. Such a ban inaugurated a powerful iconophobic, if not overtly iconoclastic, attitude that was destined to endure in the Western tradition down to our contemporary age. This attitude fed a pervasive suspicion towards images, which on account of their essentially illusory nature were considered incapable of delivering a clear and distinct knowledge of the real, and were thus opposed in this respect to the logical concept effectively expressed by language.

If we prefer to call this cultural tradition “Platonistic” rather than simply “Platonic”, it is because Plato’s meditations on the status of the image are much more complex and sophisticated than the vulgarization that over the centuries consolidated a simplistic conception of mimesis as a mere reproductive imitation of what is already given: just think of dialogues such as the Meno and the Sophist, which offer – if a pun is allowed here – a totally different picture of the image.

In spite of this complexity, it was nevertheless the “Platonistic” version of reproductive imitation that became the mainstream understanding of what visual arts aim to accomplish, and this could happen only by virtue of a fundamental inversion of the axiological condemnation expressed in The Republic: if the dialogue had judged such an imitation deceptive and delusive, it was only by reverting such a negative evaluation into a positive one that mimesis could become the fundamental task of the visual artist. This applies both to naturalism and idealism, to the extent that the representation of the ideal as an amelioration through art of what is given in nature is obtained by way of a combination of portions of natural components adequately imitated – as shown by the famous anecdote of Zeuxis and the five most beautiful virgins of Croton, each of whom lent the painter bits of beauty so that he could achieve the rendition of a perfect Helen.

The legend is recounted, among other sources, by Cicero and Pliny the Elder. The latter also offers a version of a contest between two famous painters, Apelles and Protogenes, who competed on the same canvas to demonstrate their ability to draw the thinnest line. At the end, Protogenes admitted defeat, and displayed the work that had been the battlefield of their talents to the admiration both of laymen and artists: its large surface contained “nothing but almost invisible lines, so that alongside the outstanding works of many artists it looked like a blank space, and by that very fact attracted attention and was more esteemed than any masterpiece” (Natural History 35: 83).

Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words xi

Hence, during more or less the same period as when Plato was laying down the foundations of the mimetic theory, a painting was admired as the supreme masterpiece for being nothing but blank space and almost invisible lines – in other words, for representing nothing. One could have called this painting gegenstandslos many centuries before Kandinsky’s first abstract watercolour, painted in 1910 and conventionally considered the starting point of modern abstract art. Once we begin to look for starting points, the genealogical gaze immediately attracts us towards the abysses of an almost immemorial past, that of legendary anecdotes and of myth. Such a perspective reminds us that the non-representational drive has always been there, beside (behind? below? beyond?) the representational urge, before manifesting itself openly in the outburst of the 20th century.

The present volume offers a rich panorama of this outburst, focusing on a specific kind of visual art – sculpture – which on account of its three-dimensional and volumetric nature is constitutively “objectual”, “thingish”. It is in this respect much more difficult for a sculpture to undergo a process of abstraction than a two-dimensional picture, and therefore even more challenging.

This volume, however, does not consist of a collection of interpretative essays devoted to the artistic production of some of the most prominent modern and contemporary sculptors, here listed in chronological order: Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988); David Smith (1906–1965); Tony Smith (1912–1980); Yves Klein (1928–1962); Donald Judd (1928–1994); Robert Morris (1931–); Francesco Lo Savio (1935–1963); Carl Andre (1935–); Luciano Fabro (1936–2007); Gianni Colombo (1937–1993); Robert Smithson (1938–1973); Richard Serra (1939–); Joseph Kosuth (1945–); Matthew Barney (1967–).

Its particular and distinctive feature is to lend an attentive ear to the words uttered by the sculptors themselves. The authors we have chosen to be the subjects of the book are not only eminent artists who made their mark in the contemporary sculptural landscape: they are also sharp and insightful theorists, inclined to reflect intensely upon the sense of their own work in particular and upon the nature of abstract sculpture in general.

Nevertheless, the ever more reflexive inclination of artistic expression (already observed as an ongoing and increasing phenomenon by Hegel in the first half of the 19th century) should not mislead the reader about the structural relationship instituted between artworks on one side and theoretical statements on the other. This relationship should by no means be understood as if an artist’s pronouncements contained the ultimate key to the comprehension of their art. Such a misunderstanding would lead us

Preface

xii

to an erroneous reading of these texts for two main reasons: firstly, it would fail to acknowledge a golden principle of hermeneutics, in force at least since the 18th century, namely that the authors are not the best interpreters of their own work (also because they themselves are not always aware of what they put into the work). Secondly, it would adopt a substantially logocentric approach, in assuming that only conceptual assertions assigned to verbal language can offer a clear and distinct knowledge of what is rendered in an opaque and obscure manner through sculptural activity. Essays, articles, interviews, and all kinds of non-iconic sources should on the contrary be assessed and interpreted as expressive works beside the sculptural artworks, and correlated to them in an interconnection of mutual illumination.

The three sections that make up the volume explore three of the main directions taken by abstract sculpture in the course of the 20th century: Sensation (Isamu Noguchi, Yves Klein, Gianni Colombo, Richard Serra, Matthew Barney); Idea (David Smith, Tony Smith, Donald Judd, Robert Morris); and Language (Francesco Lo Savio, Carl Andre, Luciano Fabro, Robert Smithson, Joseph Kosuth). Before inviting the reader to refer to the specific introductions to the three parts (written by my co-editors, respectively Michele Bertolini, Stefano Esengrini, and Cristina Baldacci, whom I warmly and gratefully thank here, together with all the contributors, for their intellectually stimulating cooperation in this project), I would like to say a few final words on how such notions relate to the overall concept of abstraction as illustrated above, namely in its emancipation from the “from”.

Although each of these notions operates in its own different way (and differently for each artist collected under the corresponding category), their “abstract” nature entails a renegotiation of the relationship between the author, the beholder, the sculptural object and the space hosting it. The object is no longer conceived of as a material support for the representation of a sculptural subject to be contemplated by a spectator, but is rather understood as a trigger capable of sparking an experience (and experiencer would actually be a much better name than beholder or spectator for its public).

This aspect is intuitively evident in the section Sensation, a part that thematizes the transformation of the sculptural object into a chronotopic and aisthesic experience, in which synesthetic perceptions and motor responses come to augment and radically metamorphose the traditional optical contemplation of a statue. But it is also addressed by the Section Idea, which elaborates the hypothesis that sculpture has to do with form: not in the sense of a given external shape that should be iconically

Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words xiii

replicated and aesthetically contemplated, but rather in the sense of an eidos or morphe, of structural properties that the sculptural act can bring to disclosure and identify as the truth-content of a knowledge process. Cognitive apprehension has traditionally been considered a task of conceptualization, ideally expressed in a transparent linguistic form: the last section, Language, reveals on the contrary the concrete materiality of language, its opaqueness, while at the same time hinting at the common figural origin of both language and image, two expressive domains too often and too simplistically opposed in their differences.

Sensation, Idea, Language: three ways to understand why abstraction has mattered, and still does.

CHAPTER TWO

YVES KLEIN: ALL THAT IS SOLID MELTS INTO AIR

FILIPPO FIMIANI

N’avoir pas l’air d’avoir des idées dans l’air. —Yves Klein

1. Sculptures freed from their pedestal

“Extended sculpture installation” (Faye 2009, 92): this is a recent definition of the Exposition du Vide of Yves Klein at the Galerie Iris Clert in Paris, from 28 April to 12 May 1958. It is an academic definition, yet in many aspects it is problematic, even anachronistic. It takes up, in fact, an interpretive category notoriously formulated by Rosalind Krauss (1979), but which referred neither to Klein, nor to that installation in particular, since, starting from the crisis of sculpture as a monument, it was employed with regard to the Minimalism of the 1960s, actually to Morris and Judd.

However, a criticism of monumentality is already central to Klein’s agenda and the idea of “sculptures freed from their pedestal” and from the force of Earth’s gravity is linked to the exhibition at Iris Clert, to which I will return later (see Petersen 2018).

The first sculpture without weight and base is a luminous installation or, more precisely, a public light installation, and it existed only on paper, as a blueprint. Klein wanted to illuminate the obelisk in the Place de la Concorde in blue, so that it seemed suspended in mid-air, floating, detached from the pedestal, traditionally and institutionally associated with sculpture and monumental verticality. The pedestal was as bracketed and deleted visually as a symbolic form and cultural foundation, parergonal but essential to the public visibility of the monument, and furthermore strongly politically characterized here (see Porterfield 1998, 13–41, and Curran, Grafton, Long, Weiss, 2009). Set up within the proclamations of

Chapter Two

20

Révolution bleue (Klein 2003, 57–8, 98–101; see Banai 2004, 25) and other similar statements – accused by Debord and others of a shifty political attitude –, the “liberation” of sculpture and the emancipation from the monumental fall in a very delicate moment of French history, in a deep crisis of governmental sovereignty. Among the riots and protests in Paris against the war in Algeria and elsewhere, the resignation of President Felix Gallardo and the settlement of De Gaulle, the illusory suspension of the public monument thanks the light looks as an allegorical representation of the state of exception of political power. At the same time, the bright, ineffectual and immaterial, but symbolically powerful, vandalism against the real monument erected in the Place de La Concorde seems to sublimate the acts of vandalism that Klein feared might happen against the dematerialized and liveable sculpture in the empty space of the Galerie Iris Clert (see Banai 2007, 211–4.)

The second sculpture freed from the pedestal in the fight against the law of gravity put forth by Klein, was instead achieved. This is the Sculpture Aérostatique, made of the thousand and one “Blue Balloons” released specially for the inauguration by Iris Clert (Klein 2003, 368–9). As will occur for example with Silver Clouds by Andy Warhol and Billy Klüver (formerly assistant to Jean Tinguely for the self-destructive mechanical sculpture Homage To New York, installed in 1960 in the Sculpture Garden of the MoMA), made for Leo Castelli in 1966, beyond the consistency and the force of gravity, the physical and numerical identity of the work of art was contested. Should we not speak of “aerostatic sculptures”, in the plural and replicables, as it was in 2007 in the square in front of the Pompidou? Not only the ontological identity of the sculpture, even the authenticity of the artistic production is questioned. This literally liberated work of art, dispersed and depersonalized, lost forever in the sky, not one but a thousand and one, definitely detached from the artist and the art world, is in fact made mechanically. It is just the opposite of a work done in a unique and unrepeatable way, organic, through direct and physical contact: the aerial sculptures of Klein are the reverse of the Bodies of air, a series of balloons filled by the “artist’s breath” by Piero Manzoni and then stored as documents of the artist’s life, fixed on wood as natural and physiological artefacts and existential relics (see Fimiani 2010a, 279–84, and Grazioli 2007, 94–9).

There is another type of sculpture released from the pedestal and floating in the air, which was also never really carried out which it will be useful to return to later. This is an amendment to the sculptures-éponges, made at least since 1957, for the exhibition at Colette Allendy in May. Klein writes that he had discovered the sponge while realizing

Yves Klein: All that is Solid Melts into Air

21

Monochromes: seduced by their capacity for impregnation and retention of this natural living matter, the working tool of the painter suddenly becomes first, of course, the raw material of the pigment as such, then, the portrait of the artist and spectators – or rather, the readers, as Klein writes – all soaked and saturated by the colour.

Behind this little tale of the artist and his audience, there is the history of art and its myths, ancient and far off, and there is the kitsch of contemporary history and its new science fiction and technological mythologies. Looking at the sculptures-éponges, we have to recall the happy gamble of Protogenes’ sponge told by Vasari, which by chance transforms the defeat of the manual technique of the artist and of his imitation of nature into the creation of the masterpiece, and in which Max Ernst found a way to go beyond painting (see Vouilloux 2004, 255–96); in the involuntary portrait of the artist as a painting tool, we have to read the late-Romantic exoticism of the self-portrait of the artist en éponge by Matisse who, in 1946, evoked himself in Polynesia in these terms: “I absorbed everything through the eyes, like a sponge absorbs liquid” (see Fimiani 2010b, 296–8); next to the withered sponges, we have to get the Petites Statues de la vie précaire of Dubuffet, especially Duc and Le Danseur, in sponge, glue, hemp and various materials (Rosenthal 1982, 111), and, more generally, the plastic biomorphism of the avant-gardes and material modernist Interior Design in the odour of Informal Art; finally, the porous body of coloured sponges reminds us of the lunar surface after the first circumnavigation of the world made by the third Sputnik, in October 1959, whose acrylic colours ten years later, in full pop globalization, would be just a commonplace of visual mass culture (Petersen 2009, 93 ff., and 2018, 499 ff.).

In any case, in a letter to Iris Clert of 21 May 1959, Klein refused Cocteau’s suggestion to attach the sculpture-sponges directly to the pedestal, thus creating “unreal, strange busts”, and advanced an alternative way out, which he called “the solution of pure imagination.” Disconnected fifty inches from the base, with a helium balloon inside and magnets, the sponges would levitate, without moving around and without technical interventions or tricks, like nylon wires or the like, because they would be “aero-magnetic sculptures”, made following the instructions by Klein, engaged in an accusation of theft by Vassilakis Takis (see Petersen 2009, 96 ff.). Klein was quick to file the patent (Klein 2003, 363–4, 157–8).

Chapter Two

22

2. Specificity and borderline

But we must ask ourselves, at this point, what constituted the quality and specificity of the Exposition du Vide as extended and spatial sculpture, a work capable of impregnating the bodies of the spectators the way colour does with a sponge.

Inquiring, twenty years later, the double negation made by contemporary sculpture, which is neither landscape nor architecture, Rosalind Krauss will maintain as essential the three-dimensional object built and installed in any site-specific space, delimited or extended beyond the walls of an exhibition space of the art world, or a public place of metropolitan life. On the one hand, the three-dimensionality shared by sculpture, by the site, and by architecture, seems to allow us to describe even an enclosed and empty space, as was the Galerie Iris Clert, without artworks, as an expanded sculpture, in which are contested the heaviness, the stillness and the verticality, in short, the physical impenetrability of the work placed in real space. On the other hand, the negative and differential nature of sculpture in the expanded field of which Krauss writes – neither landscape, nor architecture, yet contiguous to environmental art or land art, and to public art – then seems to be similar to what you might call the “borderline” nature of the extended sculpture installation of Klein.

According to Faye Ran (2009), “borderline” is the given constructed space of the Galerie Iris Clert, modified in a specific manner, however, so that it cannot be identified either as the work of a craftsman, perhaps with new aesthetic qualities in addition to the pre-existing properties, or as corresponding to its intended habitual use but just deprived of any physical object or, more precisely, emptied of any artwork isolable, recognizable and available as such by the viewer (see Ring Peterson 2005, 229–30, Rosenthal 2003, 79–80, and more generally Wollheim 1980, 4–10, 30–8). In fact, it can be said that the installation replaces the production of objects with an altered experience of those particular “things” that are constructed spaces. And the work of art is finally replaced by an “operation” (Klein 2003, 131) designed and realized thanks to the presence of the artist, who produces no artworks but is still an activator and operator of a sensible, corporeal experience, and even of a physiological alteration like impregnation.

To understand what is at stake in this modified fruition of places, understood and prepared as plastic artefacts, one can also start from an elementary observation about the spectatorial body. I mean that, even in an empty room as the Galerie Iris Clert, the viewer’s own body moves and orients itself, so to speak, it turns around the objectless space, as it would

Yves Klein: All that is Solid Melts into Air

23

in regard to a plastic manufactured object and between the interior and exterior spaces of a work of architecture – always in relation to the surrounding environment, to impose itself or dialogue with it. The user has a sensitive experience, in flesh and blood, real and not imaginary, of the depth. And it involves an embodied experience, a motor, tactile, and visual experience, in short a synesthetic experience, just as a viewer would if there were a sculpture or an installation, or a work of public art, and as a visitor would if he walks into an architectural place.

That is what happens with the exhibition I have described as the Exposition du Vide, but whose true title was in fact different and much more technical, La spécialisation sensibilité à l’état de la matière première en sensibilité picturale stabilisée (Riout 2009). As is known, the Galerie Iris Clert was empty, an immaculate white, repainted with a roller by Klein himself. However, it was not the first time the artist had presented an institutional place of the art world without objects – actually, without works of art – that, by tradition and habit, by cultural preconceptions and perceptual routines, the public normally expected there to be.

And the question is raised about specificity: such a space that is empty but qualified, accepted and even appreciated with a singular awareness as special – can it be quoted or replicated, can it be repeated and relived?

3. Propositions, repetitions, reinterpretations

As in the case of the sculpture-sponges, the history of the Exposition du Vide provides us with useful information. The previous year, which marks the beginning of the “blue period”, Klein prepared and presented a show split into two contemporary exhibitions. Propositions monochromes is a double-faced and a composite initiative, which mixes more traditional exhibition elements with the installation and performance, and in which we can already illustrate the complexity and ambiguity of the relationship between three-dimensional space and the sensitivity of the viewer.

The double exhibition consists of Peintures, at Iris Clert (10–25 May 1957), which incorporates the exhibition at the Galleria Apollinaire in Milan, Monochrome proposals, blue period – eleven paintings of the same size, but there are also larger canvases and some sculpture-éponges – and Pigments purs, paravents, sculptures, feux de bengale, blocs et surfaces de sensibilité picturale, the exhibition at Colette Allendy mentioned above (14–23 May 1957). Here, on the second floor, Klein prepared a room without any object, illuminating the walls repainted in white; it is, therefore, the first version Exposition du Vide. And here we are faced with many problems.

Chapter Two

24

Problems of definition and interpretation, starting right from the title, almost a list: Does it involve flat surfaces, or three-dimensional, even sculptural, blocks? What are the aesthetic and artistic properties? If they are “surfaces”, what relations do they have with Modernism and the medium specificity of painting according to Clement Greenberg’s principles?

“I work as if on a large painting” (Klein 2003, 83), we read among the notes for the show by Iris Clert: before those of Robert Irwin and Dan Flavin, the room of the gallery repainted by Klein looks like a three-dimensional colour field, as if the flatness and objecthood of painting, of a flat and impenetrable painting, had become a concave sculpture, habitable and enveloping. Klein meant to spatialize volumetrically the Monochromes, which had already radicalized and reduced the modernist canons of pure painting.

Both the room by Colette Allendy, and the Galerie Iris Clert involve, therefore, an extended sculptural installation. But what are the characteristics of both? How can you have an aesthetic experience of an empty space, modified and qualified – repainted and presented by the artist – but with no works of art, a vacant space, but not just an ordinary and liveable one, and, strictly speaking, absolutely singular, neither repeatable nor replicable?

Many subsequent exhibitions, individual and collective, have demonstrated the richness and validity of the Exposition du Vide as a turning point in the history of contemporary art and, in particular, as a reference for reconsidering sculpture and the installation; it is sufficient to cite, just as an example, Vides. Une retrospective at the Pompidou and the Kunsthalle of Bern in 2009. But a detail of the history of the exhibition at the Galerie Collette Allendy gives a cue to problematize the sensory and corporeal immediacy of the relationship between the viewer and the three-dimensional space designed and staged by Klein.

The dematerialization of the artwork, its plastic and environmental spatialization, seems here to compromise the phenomenology of the direct and immediate sensory experience, and give way to an extrasensory or paranormal experience, almost of the fourth dimension. It should be remembered that the room destined for the exhibition of works of art – actually, of their immaterialization, of the void itself – was originally the private study of the deceased husband of Colette Allendy, René Félix Eugène, one of the founders of the Société Française de Psychanalyse, author of a book on Paracelsus and doctor of Antonin Artaud in the early 1940s. Right there, in that place which later will belong to the art world, Artaud le Mômo gave breath to his own ghosts and archetypal symbols, to the personal obsessions of his own singular history and to the universal

Yves Klein: All that is Solid Melts into Air

25

myths of distant cultures; now, in this empty room full of spectres, it is Yves le Monochrome who must remove the material and specific works of art, eliminate the personal perceptual, psychological, and intellectual relationships that they allow, and let “Life” or “the Great Art” show itself again, let the pneuma of the universal Being become plastically incarnate in the distinctive and limited space of the art gallery (see Cabañas 2010, and Cabañas and Acquaviva 2012).

The solidity of the work of art and the expressive originality having been dissolved in the air, the singularity of the aesthetic perceptual and psychological experience of the viewer having vanished, the artistic medium and its aesthetic specificity having dematerialized, the extended sculpture installation becomes the place of a real hauntology and a transmission medium at once spiritual and spiritualist. Like a silent statue of Meno, three-dimensional space finally becomes a medium of communication of the “one thing that does not belong to us: our LIFE [...] in the state of a raw material” (Klein 2003, 102–3).

4. Expanded tactility

The immediate and direct experience of the space as such, both plastic and immaterial so to speak, invisible and intangible but present, is the goal and the result of a complex and articulate operation, involving very different means and mediations, tools and discourses. The phenomenological dimension, in Klein, is always intertwined with a particular self-reflective one, diverging from the aesthetic purism and the medial specificity of Modernism, and from the nominalism of Duchamp. The sensitive incorporation of space that is empty but qualitatively dense and modified and qualified by the artist is undoubtedly the true purpose of his poetry and his action. But such incorporation is activated within a strategy that also includes external elements between the given re-specialized space of the art gallery and the body of the viewer without works of art to look at and appreciate. In short, there is a paratextual threshold that accompanies, introduces and instructs the terms involved in the aesthetic relationship with the Exposition du Vide and works as marker and label that legitimize the authority of the artist and the authenticity of aesthetic experience of the spectator.

This relation is, as I said, borderline or meta-discursive, involving both concept and sensum: it has to do with a three-dimensionality that is only spatial, without objects and topics, without real and mental images, without pictures and images, without an artistic production of representations, without actions, expressions and stories. Now, this real

Chapter Two

26

atmospherization of plasticity should exclude any form of psychology and projection by the artist and the viewer – by the visitor, more precisely. The Exposition du Vide is also a correction and instruction après-coup of the fruition of the Monochromes, still characterized by the pre-conceptions, both existential and cultural, of the audience, always embedded and grounded into an historical form of life. Against all forms of symbolical and psychological projection, the environmental three-dimensionality of the diffused sculpture is a matter of incorporation, or, in Klein’s lexicon resulting from philosophy, mysticism and painting technique, is a matter of impregnation, and, to mention a term from photography, of impression. The atmospheric sculpture of the Exposition du Vide switches the viewer’s body into a support and a modifiable “sensitive vehicle”, into a carnal medium subject to alteration, in short, into a “living medium” which is, in fact, a medial or medialized body (Belting 2005, 306–7).

The vocabulary used by Klein is a symptom of a medial rhetoric, properly indexical, very interesting in relation to sculpture and tactility. The dematerialization of art, on the one hand, cancels every manual characteristic and every contact of the artist’s hands with the concrete elements and tools provided for the manufacture of the artwork; Klein refuses any direct impression, produced by physical contiguity with the support and matter, eliminates all expressive and stylistic signs, every autographic and authorial amount of the artefact. Just think of the naked bodies of the models used as pinceaux-vivants in the Anthropométries, directed with gloves and from afar like a conductor during a performance, as living drones, to leave something like fingerprints and “pagan marks”, archaic like those of Lascaux, of an “impersonal flesh”, on a horizontal surface, à la Pollock (Klein 2003, 161–2, 192–3, 282–6, 366; see Fimiani 2019). On the other hand, the dematerialization of art presupposes, prepares and makes an “abstract, but real, sensitive density” (Klein 2003, 84, 88), a radiating and spreading atmosphere. According to the logic of magic contagion and of remote contact (identified by Frazer and present in phenomenology known to Klein, for example in Bachelard, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty), this communication or participation is created thanks to a tactility with no subject and object, extended and diffused, even – as seen in an exemplary manner in the sponges – invasive and penetrating. It is an expanded tactility, abolishing the space between the viewer and the work and sinking below the epidermal surface of the spectatorial body, the intrinsic value or the absolute quality of pure space, injecting into his living body the subtle body of the Spirit.

In phenomenological terms, Klein expands sight beyond the virtual touch, which is nevertheless implied in the perception of the pictorial

Yves Klein: All that is Solid Melts into Air

27

image and of the sculptural object; basically, he transforms the remote potential action of the viewer’s hand on the object depicted or sculpted into a widespread tactility without a specific cause, into a being touched by the all-embracing space, by the environment all around. Replacing the projection with introjection and impregnation, restoring in the perceptual activity of the body in motion the sensory passivity of the flesh, Klein brings to fruition an empty space full of epidermal experiences and filled with real and tactile events. First of all, the viewer is touched everywhere by the immaterial but sensible and active space, affected by the invisible but present and working atmosphere of the art without artworks.

Enveloping like a coat that is too large, habitable without perceptual stimuli and aspects attracting attention or specific awareness, without stable objects, without apparent changes and actions, the empty space activates in the viewer that which Robert Vischer would have called the “lingering, motionless empathy” or an expansive feeling (Vischer 1994, 105). Vischer was referring specifically to architecture or, and it is a crucial example of Klein’s self-mythography, to the cloudless sky (Klein 2003, 99 and 310, see 136, 219, see McEvilley 1982, 28–9, and Solnit 2006, 157–8): the empty space of Galerie Iris Clert and the clear sky of Nice are both a manifestation that is monotonous, uniform, even perceptually boring (Moller 2014), not able to be framed by an overview and not worthy of careful and focused observation.

I mentioned the photographic metaphor. It is significant that we find it in a fragment titled Statue (Klein 2003, 218), probably from the end of 1959, and, starting from Delacroix, referring to a wide-ranging discussion on the “mark of the immediate.” Despite the allusive, if not cryptic, language, this short text is a kind of notional description and of poetological allegory. I will try my best to paraphrase it: Klein describes himself “become like a statue” because of the “exasperation of his Self”,1 petrified as artist into a monumental public persona and as a well-known actor of the art world, but in reality unseen by the audience, which does not realize that the artist has instead gone “to see the world”, the given world of ordinary life; only then, concludes the fragment, can the artist realize what has always been his dream: “to become a journalist-reporter!”

Once again, Klein is harshly critical of all forms of psychologism. As we read elsewhere (Klein 2003, 325), the “indifferent” sculpture is, as in Duchamp and Sartre, the “form” par excellence denoting the past, the life gone by and unchangeable: not only metaphorically, sculpture denies both introjection and projection, annihilates any animation of the artwork by the 1 Exaspérations was the original title for L’Exposition du Vide, and it is a recurring term, to be placed in relation with kitsch too.

Chapter Two

28

artist as Pygmalion, and affirms a mineralization of the artist’s life by himself and, mostly, by the public. The judgment on the staging, on self-celebration and, finally, on the fetishization of the artist without works of art, is inflexible. And it is highly indicative, because, instead, the supremacy of the social value of the artist related to the dematerialization of art is condemned by the most severe critics of Klein (see Buchloh 1998, de Duve 1989) as the hegemony, ultimately kitsch, of the abstract and standardized equivalency established by the capital and orchestrated only for the market.2

But what does it mean to “become a photo-reporter”? It is in the text known as Yves le monochrome 1960: le vrai devenu réalité, and then in the Manifeste de l’Hotel Chelsea, that we find the answer. Opposed to any activity, be it real and artisanal, or virtual and mental, the artist’s body is a passive support, mobile, impressionable and retentive, able to record and store events and phenomena, everything it encounters in the world. It is in Delacroix’s Journal – a note of 25 October 1825 – that Klein, in 1956, finds the notion of the “marking” of what is immediate, “fleeting” and “indefinable.” After having noted that “what an artist needs, is a reporter’s, or journalist’s, temperament, but in the great sense of the expression”, he looks back on his work and beholds that “the spiritual marking of these states-moments” of which Delacroix wrote, are the Monochromes; the “states-moments of the flesh”, are the Anthropométries, or the “footprints detached from the bodies of the models”; the “states-moments of nature”, or the “fingerprints of nature” – wind, rain, and so on –, in short the “marking of a weather event”, are the Naturemétries (Klein 2003, 282–6).

The indexical and photographic paradigm in Klein, both in the design and the making of his works, and in his poetical and critical reflection on the artistic and aesthetic experience, singular and in general, is well known (Dubois 1983, 241; Riout 2004, 23 ff; Everaert-Desmedt 2006, 116–20; Fimiani 2009). The artist, the artwork, the viewers, are all, like sensitive photographic film, present at the static event, without action or transformation (see Klein 2003, 230, 154), impressed and physically modified by the continuous and undifferentiated real, touched and moved by the all-embracing, comprehensive and invisible space. We can call it Lebenswelt, life-world, as the horizon for all shared human experience and habits, or atmospheric sculpture, a living plasticity dissolved in the air but 2 “Alles Ständische und Stehende verdampft,” that is, according to the classical tradition of Samuel Moore, “All that is solid melts into air”, is a famous quote from Marx and Engels’ Manifesto – in which there resounds, in the translation by Wilhelm Schlegel, the speech by Prospero in Shakespeare’s Tempest (Act IV, scene 1); see Marx and Engels 2004, 46.

Yves Klein: All that is Solid Melts into Air

29

shaping and moulding the sensibility of the spectators, who are literally “viveurs”, living beings in the everyday world of commonplace.

References

Banai, Nuit. 2004. “From the Myth of Objecthood to the Order of Space: Yves Klein’s Adventures in the Void.” In Yves Klein, exhibition catalogue, edited by Olivier Berggruen, Max Hollein, and Ingrid Pfeiffer, 15–38. Frankfurt: Schirn Kunsthalle and Hatje Cantz Verlag.

—. 2007. “Rayonnement and the Readymade: Yves Klein and the End of the Painting.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 51: 202–15.

Belting, Hans. 2005. “Image, Medium, Body: A New Approach to Iconology.” Critical Inquiry, 31: 302–19.

Buchloh, Benjamin. 1998. “Plenty or Nothing: From Yves Klein’s Le Vide to Arman’s Le Plein.” In Premises: Invested Spaces in Visual Arts. Architecture and Design from France 1958–98, exhibition catalogue, edited by Bernard Blisière, 86–99. New York: Guggenheim Museum.

Cabañas, Kaira Marie. 2010. “Ghostly Presence.” In Yves Klein: With the Void, Full Powers, exhibition catalogue, edited by Kerry Brougher, 172–89. Minneapolis and Washington DC: Walker Art Center and The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

Cabañas, Kaira Marie and Frédéric Acquaviva, eds. 2012. Espectros de Artaud. Lenguaje y arte en los años cincuenta/Specters of Artaud. Languages and the Arts in the 1950s, exhibition catalogue. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

Curran, Brian A., Anthony Grafton, Pamela O. Long, and Benjamin Weiss. 2009. Obelisk: A History. Cambridge (Mass.): MIT Press.

de Duve, Thierry. 1989. “Yves Klein, or The Dead Dealer.” October, 49: 72–90.

Dubois, Philippe. 1983. L’acte photographique. Paris–Bruxelles: Nathan & Labor.

Everaert-Desmedt, Nicole. 2006. Interpréter l’art contemporain. Bruxelles: De Boeck & Larcier.

Fimiani, Filippo. 2009. “Traces de pas. Atmosphères, affects, images.” In L’Index, edited by Bertrand Rougé, 177–88. Pau: Presses Universitaires de Pau.

—. 2010a. “Mémoires d’air.” In Nues, Nuées, Nuages, edited by Jackie Pigeaud, 259–84. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

—. 2010b. “Embodiments and Art Beliefs.” RES. Anthropology and Aesthetics, 57/58: 283–98.

Chapter Two

30

—. 2019. “‘Il faut détruire les oiseaux’. Mythes et histoires de l’artiste désœuvré.” La Part de l’œil, 32: 113–33.

Grazioli, Elio. 2007. Piero Manzoni. Turin: Boringhieri. Klein, Yves. 2003. Le dépassament de la problématique de l’art et autres

écrits, edited by Marie-Anne Sichère and Didier Semin. Paris: École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts.

Krauss, Rosalind. 1979. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” October, 8: 30–44.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. 2004. The Communist Manifesto (1848), edited by Len Findlay. Peterborough (Ont.): Broadview Press.

McEvilley, Thomas. “Yves Klein: Conquistador of the Void.” 1982. In Yves Klein 1928–1962: A Retrospective, exhibition catalogue, edited by Thomas McEvilley et al., 19–87. Houston and New York: Institute for the Arts, Rice University and The Arts Publisher.

Moller, Dan. 2014. “The boring.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 72: 181–91.

Ring Peterson, Anne. 2005. “Between Image and Stage. The Theatricality and Performativity of Installation Art.” In Performative Realism: Interdisciplinary Studies in Art and Media, edited by Rune Gade and Anne Jerslev, 209–34. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

Petersen, Stephen. 2009. Space-Age Aesthetics: Lucio Fontana, Yves Klein, and the Postwar European Avant-Garde. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University Press.

—. 2018. “Sculpture in Space: Flotation and Levitation in Postwar Art.” Leonardo, 5: 498–502.

Porterfield, Todd. 1998. The Allure of Empire. Art in the Service of French Imperialism 1798–1836. Princeton (N.J.): Princeton University Press.

Ran, Faye. 2009. A History of Installation Art and the Development of New Art Forms: Technology and the Hermeneutics of Time and Space in Modern and Postmodern Art from Cubism to Installation. New York: Peter Lang.

Riout, Denis. 2004. Yves Klein. Manifester l’immatériel. Paris: Gallimard. —. 2009. “Exaspérations 1958.” In Vides. Une Retrospective, exhibition

catalogue, edited by John Armleder et al., 37–46. Centre Georges Pompidou de Paris-Kunsthalle Bern: MNAM.

Rosenthal, Mark. 2003. Understanding Installation Art: From Duchamp to Holzer. München: Prestel.

Rosenthal, Nan. 1982. “Assisted Levitation: The Art of Yves Klein.” In Yves Klein 1928–1962. A Retrospective, exhibition catalogue, edited by Thomas McEvilley et al., 91–135. Houston and New York: Institute for the Arts, Rice University and The Arts Publisher.

Yves Klein: All that is Solid Melts into Air

31

Solnit, Theresa. 2006. A Field Guide to Getting Lost. Edinburgh: Canongate.

Vischer, Robert. 1994. “On the Optical Sense of Form. A Contribution to Aesthetics” (1873). In Empathy, Form, and Space. Problems in German Aesthetics, 1873–1893, edited by Harry Francis Mallgrave and Eleftherios Ikonomou, 89–124. Santa Monica (CA): Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities.

Vouilloux, Bernard. 2004. L’œuvre en souffrance. Entre poétique et esthétique. Paris: Belin.

Wollheim, Richard. 1980. Art and Its Objects. Cambridge (Mass.): Cambridge University Press.

ABSTRACTS Cristina Baldacci “Language to Be Looked at and/or Things to Be Read:” Language as a Sculptural Material in Robert Smithson

Words and objects, “mind and matter”, are equivalent to Robert Smithson, who saw in nature – and in particular in rocks – the same “syntax of splits and ruptures” that characterizes language. In his writings, which sometimes appear as montages of written and visual elements, images are not mere illustrations, but an integral part of words. And, vice versa, many of his works both define and complete themselves through words. Even his Non-Sites, the famous withdrawals of land that for Smithson represent the part for the whole, are both matter and language. Actually, they refer to a stratification of places and experiences over time. Today, many of Smithson’s interventions are hardly visitable as actual “sites.” Geographically distant, and often hidden or eroded by atmospheric agents, they belong more to nature than to the art world. However, they persist both as visual documents as well as written and oral stories. Reworking the title that is usually attributed to his works, and, more generally, to the works by other land artists, one could say that what remains of Smithson are mostly “earthwords.”

Michele Bertolini The Experience of Sculpture in Robert Morrisʼs Notes on Sculpture

The essay focuses on Robert Morris’s theoretical writings, particularly on Notes on Sculpture, published in the 1960s. Morris epitomizes the historical and anthropological idea of sculpture, and his connection with the human body and the beholder’s place. The change of scale produces a perceptual alteration and a new experience of sculpture whose identity swings between the monument and the object. The contemporary abstract sculpture requires a complex experience and consciousness from the beholder, inciting a new reflection on space and time.

Abstracts

180

Davide Dal Sasso Tensional Creation: Luciano Fabro’s Sculpture between Conceptualism and Abstraction

Abstraction in art coincides with at least two different ways of working on forms: their geometrical structuring, and their expansion up to the formless. A third way reveals the close relation between abstraction and conceptualism in art, being contaminated by the reduction of forms, the expression of ideas, and the development of creative processes. The poetics of Italian artist Luciano Fabro, in his words and works, is a considerable example of this last way to create abstract works. The author’s attempt is to identify some of the main theoretical cores of Fabro’s poetics so as to clarify his idea of sculpture in light of this approach to abstraction. To this end, in this essay he examines in particular: the deep relation between thought and action; the search for a behavioural balance in creating works; the relation between the physical plane of the work and the metaphysical one; the role of ideas and interaction in his pragmatic approach supposing that it is based on the primacy of what Dal Sasso calls “planning process.”

Anna Detheridge Gianni Colombo: A Critique of Perception in a Mobile World

Through generations and with the echo of history in their ears, Italian artists, from Lucio Fontana to Gianni Colombo and Alberto Garutti, retain and nurture a real obsession for the built space. This inquiry into the nature of our perception of space and its relationship with the human beings who inhabit it, is the focus of Gianni Colombo’s research. Despite his few writings, scanty information and synthetic interviews, today Colombo is emerging as one of the first artists to fully understand the perceptual mutations of individuals in the media and mutant contexts of our contemporary society.

Giuseppe Di Liberti “Sculpture is Matter Mattering:” Spatialization of Matter and Visual Poetry in Carl Andre

Carl Andre’s works and writings offer a rare and fertile articulation between poetry and sculpture, which interact in an attempt to overcome their limitations: on the one hand, a visual poetry that escapes the linguistic phenomenon, on the other, sculptures that want to be nothing else than “specimens of matter”, and that, therefore, require organizational and structuring schemes that Andre identifies especially through his poetry. By going through some of the most significant pages of Andre’s

Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words

181

writings (in particular, Matter Mattering, 1996; On Literature and Consecutive Matters, 1962; Poetry, Vision, Sound, 1975; Art Is Not a Linguistic Phenomenon…, 1976; Linguistic Terrorism, 1976; A Museum of the Elements, 1972; The Turner of Matter, 1980; Sculpture as Place, 1970; The Experience of Materials, 2000) and by considering his wide historical-critical reflection on 20th century sculpture, this essay intends to present the specific ways through which poetry helps to build the sculptural work as a critical (and political) space that places at its centre the experience of matter.

Georges Didi-Huberman The Simplest Image: Tony Smith’s “Cubes”

What is a cube? An almost magical object, actually. An object delivering images in the most unexpected and rigorous way ever. Undoubtedly for the very reason that it does not imitate anything to begin with, that it is itself its own figural reason. It is then undoubtedly a prominent tool of figurativity. Somehow evident, as it is always given as such, immediately recognizable and formally stable. Non-evident in other respects, as far as its extreme manageability makes it suited to any game, hence to any paradox. The cube reveals, then, its complexity as soon as we grasp its character of simple element. For it is at the same time result and process; for it belongs to the universe of children as well as to the most learned thoughts, for instance, the radical needs to which contemporary art has devoted the realm of figures, after Malevich, Mondrian, or El Lissitzky. From the start, it leads, therefore, to failure any genetic or teleological model applied to images, in particular the images of art, inasmuch as it is not more archaic than any simple result of an ideal process of formal “abstraction.” The way the American Minimal Art of the 1960s calls upon the virtuality of the cube is still, in this respect, exemplary. The investigation of such a reference should start – or start again – with Tony Smith’s work, not only because of the inaugural value of Tony Smith’s early sculptures for other minimalist artists, but also because of the value of the theoretical parable that the very story of their invention conveys.

Stefano Esengrini Vision, Perception, Openness: David Smith’s New Sculpture Dead before his time in 1965 in the climax of his creative life’s course,

David Smith appears, together with Alexander Calder, Eduardo Chillida, and Anthony Caro, as one of the most decisive abstract sculptors of the second half of the 20th century. Evidence of all this is the extraordinary display given to his work on the occasion of the exhibition organized by

Abstracts

182

Giovanni Carandente in Spoleto in 1962 entitled Sculptures in the city. Invited by the Italian Government to make one or two works at the Italsider factory in Voltri, in just one month, Smith was able to create an impressive series of twenty-six sculptures. The following year saw the advancement of the decisive series of the Cubi he had started in 1961, which sees the use of stainless steel as the material best suited to the plastic need of giving evidence to the encounter between man and nature, in which sculpture faces, by reflecting it, the vastness of celestial and terrestrial references as taken in their unceasing metamorphosis. A need, on the other hand, which had enlivened his willing to place in the two fields surrounding his studio almost ninety sculptures, in view of a more direct contact with reality, thanks to the intermediate action of the work of art, icon of that spiritual eye by which the artist corresponds to the world’s epiphany. The so-called Fields thus represent the most accomplished manifestation of the urgency which is fundamental in Smith’s work, as they define a real cosmos at a lower scale in which the artist’s existence takes place in his unexhausted challenge to himself and to the whole world to affirm his identity as a man and as a sculptor.

Filippo Fimiani Yves Klein: All That Is Solid Melts into Air Freeing sculptures from their pedestal, making them dance like

balloons in the cloudless sky and disappear from sight like space rockets towards the infinite, imbue them with transparent air like sponges and become all of a piece with the surrounding empty space: these idées fixes have for a long time been the order of the day in the Agenda of Yves Klein. Many projects, a few patents, few creations, in an unstable and ambiguous balance between utopia and irony, the sublime and the kitsch, the will to create art without works and the legend of the artist with a masterpiece. And a fable, in which the artist abandons the monument of himself to the world of art and becomes a worldly photo-reporter, and goes around recording everything that happens in the life world.

David Freedberg Joseph Kosuth and The Play of the Unmentionable

Kosuth has been producing mosaic-like juxtapositions in such a way as to produce new (or surplus) meanings that go beyond the individual texts and objects made by others. These mosaics of appropriated texts and objects become works in their own right, in which new meanings arise in the interstices between texts and texts, texts and objects. The Brooklyn installation (1990) was thus a work like any other by Kosuth. Fundamental

Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words

183

to everything that he has done is the belief that meaning cannot reside in the object or the text alone and is in no sense autonomous. The meaning of a work of art depends wholly on its context and on its relations with the viewer. Meaning, as Wittgenstein himself declared, lies in use. The Brooklyn installation was about a remote category such as the unmentionable. If art is able to show, even to describe, that which cannot be said, it is even more capable of showing that which cannot be mentioned. The point of the Brooklyn installation was to enable, through the play of these unmentionables, the laying bare of what we are no longer allowed to mention (because of the coils of institutionality), or cannot bring ourselves to mention (because of repression).

Elio Grazioli Donald Judd’s Specificity

The conception of “specific objects” synthesizes Donald Judd’s contribution to the idea of abstract art. But what “specificity” does Judd talk about? How does he mean it and in what way is it different from the one already claimed and theorized by the previous and contemporary European abstract art and also, in particular, by Clement Greenberg’s Modernism? Accused of aporia, interpreted in a formalistic way by some or in a phenomenological or post-structuralist sense by others, Judd’s theory, deemed as the background of the Minimal Art movement, is indeed also different from Robert Morris’s or Carl Andre’s and then from the minimalist critical vulgate it has given birth to. For all these reasons, in order to verify the hypothesis on which it is grounded, rereading Donald Judd’s fundamental text becomes for us the occasion for re-discussing its theoretical result.

Angela Mengoni Matthew Barney: The Semiotic Sculptural Body

Matthew Barney often referred to his artistic practice involving heterogeneous media and materials − from film to photography, from installations to petroleum jelly artefacts − as sculpture. The sculptural status of his artistic practice resides in its capability to shape a common conceptual root in different material forms, beyond any hierarchical classification of artistic mediums or genres. The paper approaches Matthew Barney’s sculpture through the relationship between such a heterogeneous family of forms, figures and materials and the much more abstract diagrammatic semantic core by which it is generated. That is why in Barney’s sculptural system abstraction plays a prominent role, both in the usual meaning of non-figurative quality and as a characteristic of the

Abstracts

184

general conceptual categories he has been constantly going back to in the ensemble of his work and that were drawn from the semantic domain of sport and biology.

Andrea Pinotti To Whom it may Concern: Richard Serra and the Phenomenology of Intransitive Monumentality

In an interview with Douglas Crimp in July 1980, Richard Serra rebelled against the tendency to interpret his sculptures in the sense of “monuments”: “When people see my large-scale works in public places, they call them monumental, without ever thinking about what the term monumental means […]. They do not relate to the history of monuments. They do not memorialize anything.” Yet, especially in front of his stelae it is difficult to avoid the impression of being faced at least with a form of monumentality: they are therefore “intransitive” in the sense that their apparently memorial gesture actually lacks the object as a referent of commemoration. From this problematic tension, we will attempt a parcours through Serra’s writings meant to single out the fundamental motives of his thinking about a certain idea of sculpture: site-specificity, the role of materials and scale, the relationship with architecture, cooperation and multi-authoriality, kinesthetic fruition, the relationship between sculpture and performance.

Clarissa Ricci Abstraction in Noguchi’s Own Words: In Search of Permanence

“Research” is one of the most commonly used words in Isamu Noguchi’s texts, matching his continuous investigation of matter around the nature of sculpture. The artist’s biography, encompassing travels between the United States, Europe and the Far East, is characterized by a sole path aimed at the comprehension of what he calls the investigation of the “unlimited field of sculptural expression” through sculpture from all ages. The Far East, Japan in particular, plays a central role in the comprehension of his production on a formal level, identifiable with his fascination towards Zen gardens or Noh masks, but also of a more intrinsic form of expression, which can be detected in his conception of space and its relation in continuum with human and bodily experience. Hence, scholars pointed out how artistic practice in Noguchi can be viewed as the search for existential awareness through sculpture. Therefore, the main aim of the text is to highlight the characteristics of Noguchi’s abstraction, primarily intended as an existential predisposition, focused on identifying elements capable of lasting in time and space, merging together both Eastern and Western heritages.

Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words

185

Riccardo Venturi Impossible Objects: On Francesco Lo Savio’s Metals This text reconsiders the figure of Francesco Lo Savio – a largely unknown Italian artist of the 1950s and 1960s – whose work remains enigmatic, fleeting, misunderstood, undoubtedly underestimated. In particular, it tackles his sculptural output, the Metalli (Metals), dark deflecting mirrors hanging in balance between painting and sculpture, craftsmanship and industrial design. These objects were and are still largely associated with minimalist aesthetics, although Lo Savio’s art was strongly rooted in pictorial abstraction, the Bauhaus and the utopian avant-garde. Through his distinctive transition from one medium to another (drawing, painting, sculpture, architecture, design, urbanism), his clear-cut writings on the space-light relationship, and the recollections of other artists and critics, this essay attempts to shed light on the complexity of his work. Lo Savio’s industrial aesthetic was equally distant from modernist paintings flatness and neo-avant-garde readymades, closer, under this respect, to the Group ZERO. The Metals – two-dimensional surfaces leaning forward towards the three-dimensional space of reality – are finally a relevant and experimental example of the “extroflection” of post-war Italian painting and sculpture.

CONTRIBUTORS

Cristina Baldacci Cristina Baldacci is an affiliated fellow at the ICI Berlin Institute for Cultural Inquiry, where she was previously fellow for the ERRANS, in Time core project (2016–2018). In 2011 she received her PhD in Art History and Theory from the Università Iuav di Venezia (in conjunction with the Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia), where she spent two more years (2013–2015) as a postdoctoral research fellow. In addition to her research and teaching activities in Venice, she has regularly given lessons and seminars at: Università degli Studi di Milano, IULM–Università di Lingue e Scienze della Comunicazione, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Politecnico di Milano. She was a visiting scholar at both Columbia University (2009) and the City University of New York (2005–2006). Her research interests focus on the archive and atlas as visual forms of knowledge; appropriation and montage practices; strategies of re-enactment, remediation and circulation of images; installation art and contemporary sculpture; visual culture studies and image theories; the relationship between art and new media. She has contributed to various journals, magazines, and essay collections, and co-edited, among others, the volumes Quando è scultura (with Clarissa Ricci, Milano: et al./Edizioni, 2010) and Montages: Assembling as a Form and Symptom in Contemporary Arts (with Marco Bertozzi, Milano: Mimesis International, 2018). She is the author of Archivi Impossibili: Un’ossessione dell’arte contemporanea (Milano: Johan & Levi, 2016), a monograph on archiving as a contemporary artistic practice. Michele Bertolini Michele Bertolini teaches Aesthetics and Art Criticism at the Accademia di Belle Arti “G. Carrara” di Bergamo. After a PhD in Philosophy (EHESS, Paris, and Università degli Studi di Milano), he was a postdoctoral researcher at the Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia (2014–2015), and has been collaborating with the chair of Aesthetics at the Università degli Studi di Milano. His research focuses on the links between the verbal and the visual, on the aesthetics and ontology of moving images, on the aesthetics of spectatorship in the 18th century (particularly on Diderot). As well as numerous writings on aesthetics, art theory (Diderot, Balzac, Bayer, Cassirer, Malraux, Fried) and cinema

Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words

187

(Bazin, Bresson, Lang, Tarkovskij, Tourneur, Welles), he is the author of: Quadri di un’esposizione. I Salons di Diderot (Roma: Aracne, 2018), L’estetica di Bergson. Immagine, forma e ritmo nel Novecento francese (Milano: Mimesis, 2002), La rappresentazione e gli affetti. Studi sulla ricezione dello spettacolo cinematografico (Milano: Mimesis, 2009), Deleuze e il cinema francese (with Tommaso Tuppini, Milano: Mimesis, 2002). He translated and edited: André Bazin, Jean Renoir (Milano: Mimesis, 2012), Diderot e il demone dell’arte (Milano: Mimesis, 2014), and co-edited: Entrare nell’opera: i Salons di Diderot (Firenze: Le Monnier, 2012), Paradossi settecenteschi. La figura dell’attore nel secolo dei Lumi (Milano: Led, 2010). Davide Dal Sasso Davide Dal Sasso obtained his PhD in Philosophy at the Università degli Studi di Torino. His research is focused on the relationships among philosophy, aesthetics, and contemporary arts, with particular interest in questions concerning conceptualism in art. He is a member of LabOnt (Laboratory for Ontology) and curator of Dialoghi di Estetica, the section of philosophy and art published in the magazine Artribune. He has edited the new edition of Ermanno Migliorini’s Conceptual Art (Milano – Udine: Mimesis, 2014). Anna Detheridge Anna Detheridge, founder and president of the non-profit research agency Connecting Cultures, is a visual arts theorist and critic. She was editor for the arts pages of the Italian newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore from 1985 to 2003. She has taught Visual Arts at the Politecnico di Milano and at the Università Bocconi di Milano and has curated several major exhibitions including the Biennale of Photography in Turin in 2003, the exhibition The Global Village at the Musée des Beaux Art in Montreal, and Arte Pubblica in Italia: lo spazio delle Relazioni in 2003 at Cittadellarte, Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Art Factory near Turin. Giuseppe Di Liberti Giuseppe Di Liberti is assistant professor in Aesthetics at the Aix-Marseille Université. He graduated at the Università degli Studi di Palermo, where he studied philosophy and where he also obtained his PhD in Aesthetics in 2003, and was a postdoctoral researcher at the EHESS in Paris. He is a member of CEPERC–Centre Gilles Gaston Granger at the Aix-Marseille University. He has worked extensively on the history of aesthetics, mainly on the system of fine arts. His current work focuses on

Contributors

188

the correlation between aesthetics and life sciences in Diderot’s thought and the notion of aesthetic fact. He is the author of Il sistema delle arti. Storia e ipotesi (Milano: Mimesis, 2009; translated in French as Le système des arts. Histoire et hypothèse, Paris: Vrin, 2016) and co-editor, together with Danièle Cohn, of Textes clés d’esthétique. Connaissance, Art, Expérience (Paris: Vrin, 2012). He has published several articles and book chapters, and is a member of the editorial board of Images Re-vues. Georges Didi-Huberman Georges Didi-Huberman, directeur d’études at the EHESS in Paris, is a philosopher and an art historian whose research spans the history and theory of images, psychoanalysis, the human sciences, and philosophy. He has been visiting professor in several universities and scholar in distinguished research institutes, and has been awarded prestigious writing and research prizes. Among his main publications, Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde (Paris: Minuit, 1992); Ninfa moderna (Paris: Gallimard, 2002); the six volumes of L’œil de l’histoire (Paris: Minuit, 2009–2016); in English translation, Invention of Hysteria. Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière (Cambridge, Mass. – London: MIT Press, 2004); Confronting Images. Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2005), Images in Spite of All. Four Photographs from Auschwitz (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012); The Cube and the Face: Around a Sculpture by Alberto Giacometti (Zurich: Diaphanes, 2015); The Surviving Image. Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms: Aby Warburg’s History of Art (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2016); Bark (Cambridge, Mass. – London: MIT Press, 2017). Apart from his writing activity, Georges Didi-Huberman is also a curator of exhibitions (the latest is Uprisings at the Jeu de Paume in Paris; exhibition catalogue Paris: Gallimard, 2016), member of scientific committees in museums, and editorial member of various journals. Stefano Esengrini Stefano Esengrini graduated in Socio-Economic Disciplines at the Università Luigi Bocconi di Milano in 1993, and in Theoretical Philosophy at the Università degli Studi di Milano in 1997. In 2004 he completed his PhD in Philosophy at the Radboud Universiteit in Nijmegen with a dissertation on philosophy, science, and politics in Martin Heidegger. Since 1998 he has been teaching Philosophy and History at undergraduate level. Since 2012 he has been collaborating with the chair of Aesthetics at the Department of Philosophy at the Università degli Studi di Milano and

Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words

189

at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore di Milano. He is a member of the Martin-Heidegger-Gesellschaft. His research topics are phenomenology, hermeneutics, and art theory. He translated and edited several volumes by Adalbert Stifter, Yves Bonnefoy, Pierre Boulez, Auguste Rodin, Jean Beaufret, Eduardo Chillida, Sachiko Natsume-Dubé, François Fédier, Georges Braque, Paul Klee, Novalis, Mario Negri. Among his writings: “Heidegger legge Stifter. Per un’interpretazione fenomenologica della ‘Eisgeschichte’”, Studia theodisca, 14, 2007; “Heidegger e Chillida. Un dialogo sullo spazio”, Aisthesis – Rivista di Estetica Online, 2010; Dal silenzio l’immagine (Milano: Bruno Mondadori, 2015). He is currently working on a book on the genesis of the work of art in 20th century painting and sculpture. Filippo Fimiani Filippo Fimiani, docteur en Lettres at Paris 8-Saint-Denis and PhD in Philosophy at the Università degli Studi “Federico II” di Napoli, is full professor of Aesthetics at the Università di Salerno. He has been visiting professor at the EHESS in Paris, at the Université Paris 7-Diderot, at the Université de Pau. He is member of the Società Italiana d’Estetica and of many academic centres: CRAL (Centre de Recherches sur les Arts et le Langage, EHESS/CNRS), among them ACTE (Structure de recherches en arts, créations, théories et esthétiques, Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne-CNRS), LIRA (Laboratoire International de Recherches en Arts, Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris 3), CICADA (Centre Inter-Critique des Arts et des Discours sur les Arts, Pau), LAMO (L’Antique, le Moderne, Nantes), PUNCTUM (Centro Studi sull’immagine, Bergamo), and of the networks Atmospheric Spaces and ViStuRN (Visual Studies-Rome Network). Fimiani is co-editor of Aisthesis, contributing editor of WikiCréation, Figures de l’art and La Part de l’Œil. David Freedberg David Freedberg is Pierre Matisse Professor of the History of Art and Director of The Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America. In the period July 2015–April 2017 he was Director of the Warburg Institute at the University of London. He is best known for his work on psychological responses to art, and mainly for his studies on iconoclasm and censorship (see, inter alia, Iconoclasts and their Motives, Maarsen: Schwartz, 1985; The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989); although his more traditional art historical writing originally centred on Dutch and Flemish art (see for example: Rubens: The Life of Christ after the Passion, London:

Contributors

190