A Longitudinal Study of Complex Syntax Production in Children with SLI There are relatively few...

-

Upload

beatrix-wade -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

4

Transcript of A Longitudinal Study of Complex Syntax Production in Children with SLI There are relatively few...

A Longitudinal Study of Complex Syntax Production in Children with SLI

There are relatively few studies of complex syntax (CS) in children with SLI (Schuele & Nicholls, 2000; Schuele & Tolbert, 2001; Eisenberg, 2003; 2004; Schuele & Dykes, 2005; Owen & Leonard, 2006). From these studies we know that children with SLI are less proficient than both their age- and language-matched peers, produce fewer instances of CS, and when CS is attempted, are more likely to omit grammatical elements of the CS (e.g., relative markers, or the nonfinite to marker). If grammatical impairment is a hallmark of children with SLI, then an understanding of the breadth and depth of the grammatical limitations associated with SLI is warranted. With the exception of the Schuele and Dykes (2005) longitudinal case study, all other CS studies have been cross-sectional. This study explores longitudinal CS production in nine children with SLI.

PROCEDURES• Archival database of language samples collected to study the production of CS in children with SLI• Children were followed longitudinally for either two, three, or four visits at four month intervals• Language samples coded for all instances of CS

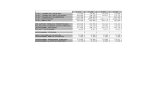

PARTICIPANTS

VARIABLESWithin Entire Transcript: Total Verbal Utterances • proportion of fourteen CS types• description of CS errors

Within 100 Complete and Intelligible Utterances• frequency of CS: number of utterances with CS• CS tokens: total number of CS tokens• embedded CS tokens: total number of embedded CS tokens• CS density: number of tokens of CS/number of utterances with CS

Time 1• Omitted obligatory relative pronoun - ACARR: [nrc] 1/7; SMYER: [nrc] 2/8• Omitted obligatory relative marker - ACARR: [src] 2/2; SMYER: [src] 1/1 but they got two of them *that are the same.• Omitted obligatory to marker - LANDE: [si] 2/28; SCRIB: [si] 1/9;

SMYER: [si] 1/25 then they’re get *to eat it all up.• Substitution of a for obligatory to marker - JSTEV: [si] 1/6; SCRIB: [si] 1/9 her wants you a pet her.• Overgeneralization of reduced infinitive - DDIGI: [cat] 1/9 her wanna go right under here.

= g she wants to go right under here • Omitted verb in relative clause - MTULX: [nrc] 1/1 because that *is how it play/*ed.• Error in subordinate conjunction - substitution - SMYER: [sc] 2/18 but [err] I forgot. = g because I forgot

Time 2• Omitted obligatory to marker - LANDE: [si] 3/25; SCRIB: [si] 1/5• Extraneous use of AND - SMYER: [sc] 2/18 every time she sticks her head in the shower and [err] she’s will say it’s nice and warm• Reduced obligatory to marker - SMYER: [si] 3/11 he looks at it a see if it is a seven.• Omitted obligatory relative marker - SMYER: [src] 1/1 see that thing *that goes around?• Error in obligatory relative marker - substitution - SMYER: [rc] 2/4 then we gotta flip one where you can’t see it and one what [err] you can see it. = g what for where

Time 3• Error in obligatory relative marker - substitution - LANDE: [rc] 1/6 he tells about the story what [err] he was singing about.

Time 4• Omitted conjunction - LANDE: [sc] 1/38 but [err] mommy is not home, daddy will put in the garage.• Extraneous use of AND - LANDE: [sc] 4/38 if it is way too hard and [err] then we do not do it.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Support for this project was provided by The Schubert Center for Child Development, CWRU; NIDCD R03 DC007329; a New Investigator Award from the ASHFoundation awarded to the second author; and an SRCLD travel award to the first author.

Karen Barako Arndt and C. Melanie Schuele Vanderbilt University

The purpose of this study was to explore the production of complex syntax in children with specific language impairment (SLI) to describe the course of complex syntax development. The study of complex syntax development in children with SLI is in its infancy. For this investigation, the spontaneous language samples of nine children with SLI (5;2 - 7;3 at Time 1) were analyzed by spontaneous language samples coded and analyzed for complex syntax. Variables included proportion of fourteen complex syntax types, frequency of complex syntax and complex syntax density within 50 and 100 utterances. Also of interest were patterns of error in production of complex syntax types. Of particular interest was inclusion of obligatory relative markers and inclusion of obligatory infinitival to. The implications of this study are both theoretical and practical in nature, with a better understanding of complex syntax development leading to the formulation of hypotheses of language development in children with SLI and guidance in relevant areas of focus in clinical intervention.

ABSTRACT

METHODS

INTRODUCTION

RESULTS PATTERNS OF ERROR

REFERENCES

PROPORTION OF COMPLEX SYNTAX IN TOTAL VERBAL UTTERANCES

CS PRODUCTIONS IN 100 COMPLETE & INTELLIGIBLE

UTTERANCES

This data suggest that complex syntax development continues in children with SLI between the ages of 5 and 9; however, their proficiency in complex syntax production is still limited. Children with SLI continue to struggle with grammatical elements of complex syntax, including the inclusion of obligatory markers. Elicited tasks targeting these types of complex syntax will be used in conjunction with this data to understand more fully the nature of CS production in children with SLI. Implications of this study are theoretical and practical, with a better understanding of complex syntax development leading to the refinement of hypotheses of language development in children with SLI, thus informing clinical practice.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

COMPLEX SYNTAX TYPES

WHAT TYPES OF COMPLEX SYNTAX

WE ARE INTERESTED IN?

DOES COMPLEX SYNTAX PRODUCTION CHANGE OVER TIME?

IF SO, HOW DOES IT CHANGE?

WHAT IS THE FREQUENCY OF COMPLEX SYNTAX WITHIN A 100

UTTERANCE CUT?

YES. CS does change over time. Although some growth is seen over over time by all nine children in one or more of the complex syntax types, the change is very limited. If complex syntax is itself on a continuum from least complex to most complex, much of the change seen is on the less complex CS types. This data suggests that CS continues to be an areas of weakness for children with SLI over time.

We are interested in 13 types of complex syntax. In particular, we are interested in complex syntax with embedded clauses. Also of interest are complex syntax types with obligatory grammatical markers, like the to marker in infinitival complements and markers such as that or who in relative clauses.

Within a 100 utterance transcript cut, and for all nine children, the change is overall is limited. Recall that there is only a 4 month time difference in samples.

For all children, growth is challenging to capture with the frequency of CS, frequency of CS tokens, and even CS density. Growth is more evident using the frequency of embedded CS tokens and # of types of CS.

While use of cognitive state complement verbs in full propositional clauses, wh- finite clauses, and wh- nonfinite clauses was very limited for some children, growth is evident over time. For most children, limitations are both in amount of verbs and in variety of verbs used.

Eisenberg, S. (2003). Production of infinitival complements in the conversational speech of 5-year-old children with language impairment. First Language, 23, 327-341.

Eisenberg, S. (2004). Production of infinitives by 5-year-old language impaired children on an elicited production task. First Language, 24, 305-321.

Owen, A. J. & Leonard, L. B. (2006). The production of finite and nonfinite complement clauses by children with specific language impairment and their typically developing peers. Journal of Speech,

Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 548-571.

Schuele, C. M. (2006). Research Manual for Complex Syntax Coding. Nashville: Vanderbilt University.Schuele, C. M., & Dykes, J. (2005). Complex syntax: A longitudinal case study of a child with specific language

impairment. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 19, 295-318.Schuele, C. M. & Nicholls, L. M. (2000). Relative clauses: Evidence of continued linguistic vulnerability in

children with specific language impairment. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 14, 563-585. Schuele, C. M. & Tolbert, L. (2001). Omissions of obligatory relative markers in children with specific language

impairment. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 15, 257-274.

Age MLU

TV Utt.

C&I Utt.

MTULX1 5;10 4.91 246 200 MTULX2 6;6 5.29 189 157 MYARK1 5;2 3.83 290 224 MYARK2 5;9 4.21 230 199 MYARK3 6;2 3.29 170 147 SCRIB1 5;11 4.59 150 123 SCRIB2 6;2 3.75 221 199 SCRIB3 6;8 4.34 101 87 SCRIB4 7;2 4.83 258 241 SMYER1 5;10 4.81 306 267 SMYER2 6;8 6.19 238 198 SMYER3 7;5 5.62 346 318

Age MLU

TV Utt.

C&I Utt.

ACARR1 7;1 6.19 172 156 ACARR2 7;6 6.40 298 259 DDIGI1 6;5 4.49 189 171 DDIGI2 7;5 4.43 368 342 JSTEV1 7;3 4.41 104 96 JSTEV2 8;0 5.63 339 323 JSTEV3 8;8 5.36 219 207 LANDE1 6;9 5.23 215 195 LANDE2 7;3 6.22 179 165 LANDE3 7;9 6.46 466 423 LANDE4 8;2 7.51 202 193 MPAUL1 6;3 6.42 166 149 MPAUL2 6;10 5.52 178 164

Proportion of CS in TVU

00.050.1

0.150.2

0.250.3

0.350.4

0.45

Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 Time 4

JSTEVLANDEMYARKSCRIBSMYER

Example Utterances

Reduced Infinitive [cat] LANDE1: That’s because she is gonna have babies.

Let’s clause [lc] SMYER2: Let me go check in my mom’s room.

Coordinate clause [cc] ACARR1: And you could unscrew it and make it taller.

Subordinate clause [sc] MPAUL: She wanted another cat because she didn’t have a cat.

Marked infinitive [si] SCRIB3: You try to get to your spot before they tag you.

Unmarked infinitive [uic] LANDE1: They helps [err] children find their parents.

Subject relative clause [src] MYARK2: And the people who was [err] hiding get to count.

Relative clause [rc] SMYER1: Then the last one I saw was Andy.

Headless relative clause [nrc] MTULX2: That’s what we do.

Full propositional complement [fpc] JSTEV3: I think she’s just making that up!

Wh- finite clause [wfc] LANDE2: And Dexter say who is my favorite friend?

Wh- nonfinite clause [wnfc] SMYER2: In the first grade we are learning how to count money.

Participle clause [pc] DDIGI2: Then they get that guy being bad.

Other [other] ACARR1: And it’s like you just sit on it or something.

Tota l freq.

of CS

[cat]

[lc]

[cc]

[sc]

[si]

[uic]

[src]

[rc]

[nrc]

[fpc]

[wfc]

[wnfc]

[pc]

[other]

ACARR1 51 .02 .41 .25 .22 .08 .02

ACARR2 87 .15 .44 .15 .07 .14 .05

DDIGI1 39 .23 .31 .27 .15 -- .05

DDIGI2 66 .35 .29 .08 .09 .11 .09

JSTEV1 20 -- .54 .35 .05 .05 --

JSTEV2 83 .02 .51 .27 .07 .11 .02

JSTEV3 53 -- .36 .43 .06 .09 .06

LANDE1 63 .06 .39 .44 -- .12 --

LANDE2 63 -- .45 .40 .03 .06 .06

LANDE3 149 .04 .38 .38 .10 .07 .03

LANDE4 79 .10 .48 .21 .08 .12 .01

MPAUL1 83 .04 .49 .14 .06 .22 .04

MPAUL2 81 .07 .38 .19 .03 .28 .02

Frequency

of CS

Frequency of CS tokens

Frequency of

Embedded CS tokens

CS Density

Complement Verbs (in fpc, wfc,

wnfc)

# of types of

CS

ACARR1 26 28 8 1.08 think (1) 7 ACARR2 11 12 10 1.09 forget (1)

guess (1) tell (1)

think (2)

5

DDIGI1 11 17 2 1.55 said (1) 8 DDIGI2 6 7 3 1.17 5 JSTEV1 8 8 2 1.0 know (1) 5 JSTEV2 22 33 5 1.5 think (3) 6 JSTEV3 21 30 5 1.43 said (1) 6 LANDE1 28 34 3 1.21 know (2)

say (1) 5

LANDE2 26 36 2 1.38 say (1) 7 LANDE3 23 31 6 1.35 see (1) 8 LANDE4 24 27 8 1.13 know (2)

say (3) 7

MPAUL1 38 53 17 1.39 know (4) like (2)

show (1) think (6) told (1)

7

MPAUL2 33 43 17 1.30 forget (1) know (2)

remember(1) think (2)

10

MTULX1 24 25 6 1.04 mean (1) say (1)

6

MTULX2 33 47 6 1.42 know (1) say (3)

8

MYARK1 13 15 3 1.15 know (3) 7 MYARK2 22 27 4 1.23 know (1)

pretend (1) 9

MYARK3 14 18 0 1.29 4 SCRIB1 12 14 2 1.17 know (2) 7 SCRIB2 11 13 3 1.18 know (3) 7 SCRIB3 8 21 1 2.63 remember(1) 5 SCRIB4 25 34 13 1.36 know (6)

mean (1)

11

SMYER1 23 35 11 1.52 know (1) say (1)

8

SMYER2 28 36 15 1.29 forget (3) know (1) say (4) see (1)

teach ( 3) think (1)

12

SMYER3 29 38 4 1.31 say (4) 9

50 VERSUS 100 UTTERANCES: WHY USE 100?

Frequency of CS, CS tokens, CS embedded tokens, CS density, complement verbs used with CS, and # of types of CS were all analyzed within both a 50 and 100 complete and intelligible transcript cut.

Growth over time is more evident with a 100 utterance cut, in particular with the frequency of embedded CS tokens and # of types of CS variables.

Much growth can also be seen by examining the complement verbs in [fpc], [wfc], and [wnfc], as seen below:

DDIGI 150 Utt.: 1 [cat], 4 [cc], 5 [si]100 Utt: 1 [cat], 6 [cc]. 1 [sc], 5 [si], 1 [uic], 1 [fpc], 1 [nrc], 1 [pc] including 2 embedded CS

DDIGI 250 Utt.: 1 [rc], 1 [nrc], 1 [pc]100 Utt: 1 [cat], 3 [rc], 1 [nrc], 1 [pc], 1 [other] including 3 embedded CS (versus 2 at 50 utterances)

MTULX1 75 .20 .55 .03 .04 .17 .01

MTULX2 100 .06 .36 .45 .04 .08 .01

MYARK1 59 .15 .22 .41 .02 .19 .02

MYARK2 75 .35 .17 .35 .08 .05 --

MYARK3 24 .08 .38 .54 -- -- --

SCRIB1 26 .35 .27 .35 .04 .08 .04

SCRIB2 19 -- .42 .26 .11 .16 .06

SCRIB3 30 .20 .27 .43 -- .1 --

SCRIB4 71 .09 .34 .19 .15 .21 .01

SMYER1 74 .07 .32 .34 .16 .10 --

SMYER2 63 .11 .31 .15 .14 .29 .03

SMYER3 125 .11 .35 .23 .09 .18 .04