3. OVERVIEW OF SWORDFISH FISHERIES -...

Transcript of 3. OVERVIEW OF SWORDFISH FISHERIES -...

Fishery overview

Swordfish fisheries 21

3. OVERVIEW OF SWORDFISH FISHERIESMost of the world’s swordfish catch is taken by pelagic longline, with smaller catches taken bydriftnet and harpoon and occasionally handline, troll-line, trap (Folsom et al. 1997, p. 9), purseseine and pole-and-line. In several areas, recreational anglers target swordfish with drifting baitsor trolled lures. In this section we describe the main fishing methods for swordfish (longline,driftnet and harpoon), their history, the geographical distribution of swordfish fisheries and globaltrends in catch.

Development of swordfish fisheriesHarpoon

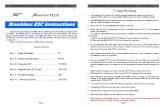

The earliest fishing activities forswordfish used harpoons andprobably handlines (Figure 2).Harpooning involves stalking aswordfish that is basking orfinning at the sea surface, thenspearing it with a 4–5 m longharpoon with a metal head (orheads) attached to a line. The lineis usually attached to a buoy orfloating drum to allow theswordfish to tire before beinghauled on board (Von Brandt1984, pp. 56–59).

Subsistence fishers haveharpooned swordfish for thousands of years. Swordfish harpooning originated in areas wherebasking behaviour coincided with calm weather conditions and easy access to deep, oceanicwaters, e.g., the Mediterranean Sea since the tenth century BC (Di Natale 1991), off westernNorth America 2000 years ago, western South America since at least the 1600s and Japan forseveral centuries (Davenport et al. 1993, p. 265; Folsom et al. 1997, p. 9; Sun et al. 1999, p. 3).The Taiwanese also harpoon swordfish, catching about 200 t per year during the early 1990s.Their catches declined to less than 30 t after 1994. Japan’s and Taiwan’s harpoon fisheries alsotake other species, such as marlin (Wildman 1997, p. 4).

United States and Canadian fishers have harpooned swordfish off New England since the mid-1800s (Goode 1883).1 In the early 1900s a harpoon fishery began in Nova Scotia, Canada. Untilthe late 1950s harpooners continued to land catches of swordfish, but in the 1960s longliningquickly replaced harpooning as the dominant fishing method for swordfish in the north-westernAtlantic. Many United States and Canadian fishers continue to hold harpoon licences andoccasionally harpoon swordfish when fishing for bluefin tuna (Gibson 1998).

A commercial harpoon fishery developed for swordfish off California in the early 1900s, withcatches peaking at 1699 t in 1978 (Ito and Coan 1999, pp. 24, 29). Harpoon fishing operationsthere and in most other areas have become more sophisticated, with motorised boats, longbowsprits, high crow’s nests, spotting planes and harpoons that give the fish a lethal electric shock(Wildman 1997, p. 28). Nevertheless, most harpoon fisheries declined during the 1980s as a resultof decreased abundance of basking swordfish, increased labour costs and the availability of moreefficient fishing methods for swordfish, such as longlines and driftnets.

1 Cited in Hoey et al. (1989).

Small, fresh-chilled longliners undertake fishing trips of several weeks.

Bureau of Rural Sciences22

1000BC

177BC

AD

1840

1930

1940

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

North American boats start using longlines to target swordfish.

Taiwan and Korea commence d istant-water longlining for tuna.

Japan’s longliners begin to target sashimi tuna.

Spain’s longline fleet begins to expand .

United States and Canada set a mercury limit of 0.5 ppm.

Florida-based anglers adapt lightsticks for fishing.

United States and Canada (1979) raise mercury limit to 1.0 ppm.

Spain’s longliners begin to extend operations southwards and westwards.

Monofilament nylon driftnets available.

Longliners begin to use monofilament nylon longline gear.

Expansion in fresh-chill longline fisheries for sashimi tuna commences.

First stock assessment of North Atlantic swordfish by ICCAT concludes that 1978–80 catches exceeded stock production.

Many longliners begin to relocate from the North Atlantic to the South Atlantic.

United Nations bans d riftnets longer than 2.5 km.

Many Atlantic longliners join a rapidly developing swordfish fishery Hawaii. ICCAT agrees on quotas for

North Atlantic swordfish.

Boycott of swordfish by many restaurants in North America.

USA bans imports of under-size north Atlantic swordfish.

Harpoon fishing commences in Mediterranean Sea.

Driftnet fishing commences in Mediterranean Sea.

Harpoon fishery established off New England , United States.

Artisanal harpoon fishery starts to expand in Chile.

Japan commences d istant-water longline operations for tuna and swordfish.

North American tribes start harpooning swordfish in California.

Figure 2. Timeline showing significant events in the history of the world’s swordfish fisheries.

Fishery overview

Swordfish fisheries 23

DriftnetDriftnets, also known as drift gillnets or pelagic gillnets, entangle fish when they swim into them.Driftnets are usually suspended at a predetermined depth from buoys at the sea surface.Sometimes the headline is buoyant so that the top or ‘head’ of the net floats at the sea surface. Tocatch swordfish, driftnets are usually set at night and retrieved the following day.

Subsistence fishers have used entangling nets, made of natural fibres, such as hemp, to catch fishsince the earliest times. In the 1950s synthetic fibres and knotless nets became available, butmonofilament driftnets were not widely used to catch swordfish until the mid-1980s. In someareas (e.g., California) fishers prefer driftnets made of multistrand synthetic materials (Von Brandt1984, pp. 207–9; Hanan et al. 1993, p. 13).

Many swordfish fishers upgraded to driftnets because they produced larger catches than harpoonsand could be used over a wider range of sea and weather conditions. In some areas (e.g., Chile),government incentives encouraged the switch to driftnets. In the late 1980s fishers using small-scale driftnets in several areas (e.g., the Mediterranean) began to attach lightsticks to their driftnetsto increase their swordfish catch rates.

During the late 1980s Japan and Taiwan developed distant-water driftnet fishing operations totarget pelagic species (e.g., salmon, squid and albacore) in international waters. There was animmediate outcry over wastage and the bycatch of marine wildlife by driftnets, especially in large-scale operations targeting albacore. In response to those concerns, many nations banned driftnets.A 1991 United Nations moratorium limited driftnets to 2.5 km in length. Small-scale (<2.5 km)driftnets continue to be used to catch swordfish in several areas, such as Chile, Mexico, Japan,Africa and the Mediterranean Sea (Folsom et al. 1997, p. 9).

LonglineFishers have used pelagic longlines—a series of baited hooks attached to a mainline suspendedfrom buoys at the sea surface—to catch tuna since the early 1800s (Wildman 1997, pp. 26–28).The Japanese pioneered large-scale, commercial longlining in the 1950s and distant-waterlonglining quickly spread throughout the world’s seas and oceans. Longline is now the dominantfishing method for swordfish, accounting for about 85 per cent of world landings in1997 compared with landings by driftnet (~10%) and by harpoon (<5%).

In the late 1980s fishers in various ports of the Pacific realised that tuna could be stored on ice andairfreighted to lucrative sashimi markets in Japan. Others soon realised that fresh swordfish couldbe profitably airfreighted to distant markets, such as the United States. There are now two types oflongliner fishing for pelagic species, such as tuna and swordfish:

• Large, ‘distant-water longliners’ that range over the world’s oceans. Their trips last upto 18 months and they freeze their catches.

• Smaller, ‘fresh-chilled’ longliners that mostly chill their catches. They are based in local ports,close to airfreight facilities and usually undertake trips of 1–3 weeks.

Most fresh-chilled longliners use monofilament nylon mainlines wound on to a hydraulic drumand monofilament nylon branchlines stacked in boxes. Some distant-water longliners usemonofilament mainlines, but many use traditional ‘rope’ gear. The rope gear consists of amultistrand kuralon mainline and multistrand or monofilament branchlines. Branchlines are placedin baskets and the mainline is coiled into a hold.

Bureau of Rural Sciences24

Table 2. Summary of the world’s fisheries for swordfish.

Area Year commenced Main fishing nations Fishing method(s) Annualcatchi Stock status Fishery status Prospects

Mediterranean Sea 1000 BC Italy, Morocco, Spain, Algeria, Cyprus, Greece, Malta,Tunisia, Turkey longline, driftnet, harpoon 14 670 t Uncertain, probably overfished. Totalcatch levels and size composition of catches has declined. Continued mortality of juvenileswordfish may cause wide fluctuations in recruitment and significant reductions in the size of thespawning stock. Static. Longline and driftnet fishing activity static, harpoon activity declining.Catch levels declining. Catch levels and returns from the resource are likely to stay well belowoptimum while fishing nations unable to agree on and enforce, appropriate management measures.A fishery collapse may result with little warning.

North Atlantic 1800s Spain, United States, Canada, Japan, Portugal, Taiwan, Morocco,Venezuela longline, harpoon 12 175 t Overfished, rebuilding. Catch levels aboveestimated maximum sustainable yield in most years since late 1980s. But, decline in swordfishbiomass may now have slowed. Strong recruitments of young swordfish in 1997 and 1998.

Declining. Substantial declines in catch due to relocation of longliners to other areas,quotas and size limits and reduced swordfish abundance. The stock remains at historically lowlevels and rebuilding will require the long-term commitment of all fishing nations. In response todeclining catch rates, many longliners are targeting tuna or shark or have relocated to the SouthAtlantic.

South Atlantic 1955 Spain, Brazil, Uruguay, Portugal, Japan, Taiwan longline, driftnet13 486 t Overfished. Catch levels above estimated maximum sustainable yield in most

years since early1990s. Increasing. Fishing activity increasing. Catch levels declining. Catchrates, at least in some bycatch fisheries, declining. With declines in swordfish catch rates nowemerging, more longliners are likely to redeploy to other areas.

South-eastern Pacific 1500s Chile, Peru, Spain, Ecuador longline,

driftnet,

harpoon 4 402 t Not known. Static. Longline fishing activity increasing, harpoon and driftnetfishing declining. Catch levels static. Trend to large longliners ranging into distant waterslikely to continue.

Fishery overview

Swordfish fisheries 25

Table 2. Summary of the world’s fisheries for swordfish (cont’d)

North Pacific 1700s Japan, Taiwan, Mexico, United States, Philippines longline,

driftnet,

harpoon 8 154 t Uncertain. Not exploited at levels likely to depress catch rates until at least theearly 1980s. Catch levels believed to be below those estimated to produce maximum sustainableyield. Static. Longline fishing activity and catch levels static. Harpoon and driftnet fishingdeclining. Global market provides stable, but low prices for frozen swordfish. Regulationsstemming from environmental concerns may further limit activities of the United States longliners.

South-west Pacific 1953 Australia, New Zealand, Japan longline 4 193 t Notknown. Increasing. Longline fishing activity and catch levels increasing. Trend to largelongliners ranging into distant waters likely to continue. Heavy reliance on the United Statesmarket leaves fisheries vulnerable to fluctuations in exchange rates and import restrictions.

Indian Ocean 1953 Taiwan, Sri Lanka, Réunion, Seychelles, South Africa, Spainlongline, driftnet 16 735 t Not known. Increasing. Longline fishing activity and catch

levels increasing, mostly in the western Indian Ocean. Trend to large longliners ranging intodistant waters likely to continue.

Bureau of Rural Sciences26

Swordfish are a common bycatch of both fresh-chilled and distant-water longline operationstargeting tropical tuna, such as yellowfin and bigeye. Swordfish are rarer in catches taken bylongliners fishing for southern bluefin, northern bluefin and albacore at temperate latitudes.Longlining for yellowfin and bigeye involves day sets. Longlines are set ‘deep’ to target bigeye(50–400 m) and at ‘regular depths’ (30–200 m) to target yellowfin.

Some fresh-chilled longliners use live bait, such as milkfish, when fishing for yellowfin andbigeye. Longliners often use lightsticks—chemically luminescent cylinders that attract small fishand squid—to target swordfish. Distant-water longliners rarely use lightsticks. The fresh-chilledlongliners sometimes use lightsticks to target bigeye.

Swordfish are predominantly a longline bycatch of the world’s two leading swordfish harvesters(Taiwan and Japan). For all harvesters, we estimate that about 50 per cent of the current globalswordfish catch is bycatch. Bycatch presents problems to fishery management and to assessment;for stock assessment it is difficult to collect catch, effort and size composition data on bycatchspecies and it is difficult to manage fishing for a bycatch species when the fishery is based onanother, target species.

When Japan’s distant-water fishery began to expand in the 1950s their longliners targetedalbacore and swordfish (Sakagawa 1989, p. 67). Swordfish catch rates were particularly high in anarea of the north-western Pacific (the Higashioki fishing grounds) and a targeted longline fisherycontinued there after distant-water longliners in other areas began to target tuna for sashimimarkets (Takahashi and Yokawa 1999, p. 1). Smaller longliners also target swordfish in thecoastal waters of Japan and Taiwan.

In the early 1960s incidental catches of swordfish by distant-water longliners prompted NorthAmerican boats to install pelagic longlinegear to target swordfish. Longlining provedto be far more efficient than harpooning. Notonly were catch rates higher, but boats couldoperate in weather conditions and areas thatwere unsuitable for harpooning (Hoeyet al. 1989; Beckett 1971; Caddy 1976;Hurley and Iles 1981). In the late 1960slonglining for swordfish began in the Gulf ofMexico; it began in the mid-1970s in GulfStream waters and in the mid-1980sswordfish longlining began in the Caribbean(Berkeley et al. 1981). In the late 1980s and early 1990s many longliners moved considerabledistances, from areas such as the Gulf of Mexico, to join a rapidly expanding swordfish fisherybased in Hawaii.

On the other side of the Atlantic, longlining for swordfish began in coastal areas off south-westernSpain in the late 1800s. The fleet rapidly expanded during 1966 when a new longline fisherydeveloped off north-western Spain, from the port of Vigo. Another period of expansion began in1980 when Spain’s longliners extended their operations off the coastline of Africa and into theGulf of Guinea as far south as the equator. Others moved westwards, eventually reaching theCanary Islands (Folsom et al. 1997, p. 100).

In the late 1980s and 1990s fresh-chilled longline fisheries developed for swordfish in many areasof the Pacific, western Atlantic and Indian Ocean, the catches stored ‘fresh’ in ice slurry, brineslurry or in spray brine systems. Fresh-chilled fisheries usually involve small (15–25 m) longlinersundertaking trips of one or two weeks’ duration. Longer trips are possible for swordfish. Hawaii-based longliners, for example, regularly undertake trips lasting four weeks or more. Swordfish aresometimes stored at slightly cooler temperatures (~–2ºC) than sashimi tuna (~0ºC) and have betterstorage qualities.

Unlike the situation for sashimi tuna, fresh-chilled longline fisheries rarely airfreight chilledswordfish to Japan. The eastern coastline of the United States is the main market for swordfish

Swordfish shelf lifeSwordfish can be stored fresh for longer than most fishspecies. Factors contributing to their long ‘shelf life’include a low fat content, predominance of whitemuscle (there is little red muscle) and lower lactic acidbuild-up. They often inhabit deeper, colder water thantuna. Furthermore, flesh quality is not as critical forswordfish, which are cooked, rather than consumed rawas is the case for sashimi tuna (Dr S. Thrower,17 February 2000).

Fishery overview

Swordfish fisheries 27

caught by fresh-chilled fisheries in the Pacific (e.g., eastern Australia and New Zealand) andwestern Atlantic, (e.g., Brazil and Uruguay). It is also the main market for swordfish taken by thedeveloping fishery off Western Australia, which is one of the few fresh-chilled swordfish fisheriesin the eastern Indian Ocean. For fresh-chilled fisheries in the western Indian Ocean (e.g., theSeychelles, La Réunion and South Africa), the main destination is markets in Europe, such asItaly.

The fresh-chilled longline fisheries either target sashimi tuna (bigeye or yellowfin) or swordfish.Australia’s eastern and western fisheries seem to be unique in that they are mixed swordfish–bigeye fisheries.

Fishery distribution2

In 1997 the largest proportion (41%) of the world’s landings of swordfish (97 698 t) was taken inthe Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, followed by the Pacific Ocean (31%) and IndianOcean (12%; Figure 3). Commercial fishing for swordfish occurs in both tropical and temperatewaters, but the largest fisheries are in temperate waters (23–45º north and south of the equator;Folsom et al. 1997, p. 1; Map 1).

Swordfish fisheries tend to occur in oceanic waters where primary production is high and preyspecies (small fish and squid) are abundant, e.g., over offshore seamounts, shelving banks andassociated with oceanic convergence zones or ‘fronts’ where warm currents meet cooler nutrient-rich waters. At mid-latitudes (15–35º north and south of the equator), a major clockwisecirculation or ‘gyre’ dominates the North Atlantic and North Pacific and a counterclockwise gyredominates the South Atlantic, South Pacific and southern Indian Ocean (Pickard 1979, p. 124). Attheir margins, the mid-ocean gyres create frontal zones that concentrate or attract pelagic specieslike swordfish. In contrast, swordfish are rare in nutrient-poor or ‘oligotrophic’ waters at thecentre of the gyres.

2 Largely based on Folsom et al. (1997, pp. 1–3).

longline (targeted)d riftnetharpoon

limit of d istribution

Map 1. Current distribution of the main, targeted fisheries for swordfish. Not shown are subsistence and small-scale commercial fisheries that exist in coastal waters at mid-latitudes (15–35º south and north) in many areas.Most of the global catch of swordfish is a bycatch of tuna longline fishing which is distributed more broadly acrossthe world’s oceans.

Bureau of Rural Sciences28

In the Pacific, targeted swordfish fisheries are associated with five frontal zones:

• in the north-western Pacific, where the warm Kuroshio Current meets coastal waters of Japanand Taiwan and, further north, where the Kuroshio Current Extension meets the colderOyashio Current;

• off eastern Australia, where the warm East Australian Current meets cold West Wind Driftwaters;

• off northern New Zealand, where the warm South Equatorial Current meets cold West WindDrift waters;

• in the south-eastern Pacific, at the boundary of the cool Peru Current and where its northwardsextension, the South Equatorial Current, meets the Panama Bight Waters (Dr J. Joseph, 7 May2000); and

• off western North America (California, Baja California and Mexico), where the cool offshoreCalifornia current meets warmer southern waters (Folsom et al. 1997, p. 3).

In the Atlantic, swordfish are believed to move seasonally in a circular pattern. During July–September they are caught in northern latitudes, moving to lower latitudes when waters cool inJanuary–March. Adult swordfish enter the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar, arrivingat Sicily in May each year (Folsom et al. 1997, p. 2). In the Indian Ocean, swordfish concentrateoff India, Sri Lanka, Saudi Arabia and along the eastern coastline of Africa down to the Cape ofGood Hope and around to 30ºS on the South Atlantic side of the continent. They are alsoabundant off south-western Australia (Folsom et al. 1997, pp. 2–3; Penny and Griffiths 1998,p. 2).

3 Landings are reported as whole weight and for vessel flag rather than the area of capture. We estimated the

proportion of bycatch based on data on the components of each nation’s fishery or more qualitative informationon their activities. The 1997 estimate of Australia’s landings is from logbook data raised to whole weight. FAO’s1997 estimate for Australia’s landings of swordfish is 62 t, giving it a ranking of 30.

0 5 10 15 20 25

Other nations

Morocco

Mexico

Sri Lanka

Brazil

*Australia

Chile

Philippines

Italy

United States

Spain

Japan

Taiwan

Landings ('000 t)

TargetBycatch

*estimate from logbooks

Figure 3. Annual landings reported by the 12 leading nations harvesting swordfish in 1997 (FAO 1999).3, 4, 5 Wewere unable to verify the surprisingly large catch reported for the Philippines.

Fishery overview

Swordfish fisheries 29

Global trendsThe Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO 1999)4 reports that swordfish landings (97 698 t)account for about 3 per cent of the 3 300 000 t landings of oceanic tuna and billfish reported bythe Food and Agriculture Organization for 1997. Nevertheless, the swordfish catch is larger thanthat of all billfish combined.

Sixty-two nations reported catches of swordfish to the Food and Agriculture Organization in 1997,compared with 34 nations in 1984. Taiwan, Japan5 and Spain have accounted for more than halfof those landings since the mid-1980s (Figure 3). As a result of an abrupt increase in distant-waterlongline catches, particularly in the western Indian Ocean off Somalia, Tanzania and South Africa,Taiwan suddenly overtook Japan as the leading harvester of swordfish in 1995 (Dr C. Sun,15 February, 19 March 2000). Taiwan reported 21 863 t of swordfish (22% of total worldlandings), followed by Japan (18%) and Spain (15%) in 1997. Targeted fisheries for swordfishexist in coastal waters of Taiwan and Japan and Japan has a small fleet of longliners that targetswordfish in the wider north-western Pacific. However, most swordfish landed by Taiwan, Japanand South Korea are an incidental catch of longline fishing operations that target tuna. Distant-

4 FAO developed its fishery statistics database from data provided by national correspondents and regional fishery

organisations (e.g., ICCAT). Some data provided to FAO, particularly those for the last year of the series, areprovisional and subject to future revisions. Several nations with developing swordfish fisheries do not reportcatches to FAO (Folsom et al. 1997, p. 10). Where officially reported statistics are lacking or are consideredunreliable, FAO estimates statistics based on the best information available or, in the absence of information,repeats the data previously reported for the nation. Several nations report their catches by large groups of speciesand an unknown proportion of the catch of some species might have been reported under a broad species group,e.g., ‘billfish’ (Dr A. Crispoldi, 10 February 2000). Discarded swordfish, particularly small swordfish that are anincidental catch of longliners targeting tuna in tropical waters, are unlikely to be reported. Consequently, speciestotals frequently underestimate the actual catches and there are inconsistencies between FAO statistics andestimates of swordfish catches in sub-areas.

5 Catches are the whole weight equivalent of landings. However, there is uncertainty about the processing of catchdata by distant-water fishing nations, such as Japan and Tawain. Those fleets fillet many of the swordfish thatthey catch, yet it is unclear how fillet weights are raised to whole weights. Consequently, global catch statisticsmight substantially underestimate true catch levels of swordfish.

0

20

40

60

80

100

1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996Year

Lan

ding

s ('0

00 t)

PacificIndianAtlanticMediterranean

Figure 4. Estimates of annual global landings of swordfish, aggregated by ocean or sea (FAO 1999).

Bureau of Rural Sciences30

water longline landings are frozen and sold at lower prices than markets in the United States andEurope generally pay for fresh-chilled swordfish.

Although it has several features of the fish that are popular as sashimi, swordfish is usually cooked(grilled, fried or broiled) before consumption. Unit prices of swordfish are generally lower thansashimi tuna prices. The United States is the world’s largest market for swordfish, consumingabout 25 per cent (~16 000 t Dwt or 22 000 t Wwt) of the world’s catch (NMFS 1999c, p. 2). Othermajor markets for swordfish include Europe (particularly Spain and Italy) and Japan.

Prices paid in the United States for fresh-chilled swordfish provide a guide to world price trends.Unadjusted unit prices increased substantially between the late 1960s (<US$1.00/kg)6 and the late1980s, peaking at United States$7.99/kg in 1987 (Figure 5). A 1971–78 reduction in the tolerancelevel for mercury in swordfish (see p. 52) reduced swordfish imports and severely depressedconsumption in the United States and worldwide. Whereas production declined, prices remainedstatic during the period (Lipton 1986, p. 24). In the late 1990s prices fell from about UnitedStates$7.00/kg (1996) to less than United States$5.00/kg as a result of increased supplies fromSouth America and the south-west Pacific and a boycott of swordfish in United States restaurantsinitiated by conservation groups (see p. 55; Kronman 1999, p. 14).

Global landings of swordfish almost doubled from 53 543 t in 1984 to 97 698 t in 1997 (Figure 5).The rise was mostly due to increases in landings reported from the Pacific Ocean (18 158 t in1984, increasing to 31 617 t in 1997) and the Indian Ocean (1804 t, increasing to 24 833 t in1997). Most of the increase in Indian Ocean landings was from western areas, whereas landingsincreased over most areas of the Pacific.

Bycatch contributed to most of the increase in global swordfish landings; the bycatch of swordfishincreased from an estimated 14 000 t in 1984 to almost 59 000 t in 1997 (Figure 6). Bycomparison, the targeted catch of swordfish fluctuated between about 39 000 t (1984) and 60 000 t(1989) and tended to decline after the late 1980s – mid-1990s.

6 All unit prices are quoted as price per dressed weight (whole, trunk, fillet or a combination of those forms).

0

2

4

6

8

Year 1959 1969 1979 1989

Year

Ex-

boat

pri

ce (U

S$/k

g)

mercuryrestrictions

restaurantboycott

Figure 5. Annual raw prices of fresh-chilled swordfish landed by United States fishing boats in the Atlantic andGulf of Mexico (NMFS 1999a). Prices are unadjusted, for example, for changes in the value of the United Statesdollar or cost of living.

Fishery overview

Swordfish fisheries 31

In several areas, annual catches of swordfish peaked at about 20 000 t then declined by about halfand stayed at that level. Swordfish landings in the Mediterranean Sea declined from 20 339 t in1988 to 11 433 t in 1996. During 1987–98 annual catches declined from 20 236 t to 12 175 t inthe North Atlantic. In the South Atlantic, annual landings increased rapidly, from about 5000 tduring the mid-1980s to 17 918 t in 1995. But they then declined in the South Atlantic to 13 486 tby 1998.

Swordfish catch levels increased rapidly in the South Atlantic during the mid-1990s. TheInternational Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas considers that South Atlanticswordfish have been fished at levels above the estimated maximum sustainable yield in most yearssince the early 1990s.

Swordfish are also likely to be overexploited in the Mediterranean Sea. There, total catch levelsand size composition of catches has declined. Continued mortality of juvenile swordfish maycause significant reductions in the size of the parent stock and wide fluctuations in recruitment.

Reliable stock assessments are not available for the other swordfish fisheries, which is ofparticular concern for those fisheries that are expanding rapidly in the south-west Pacific andwestern Indian Ocean.

0

20

40

60

80

100

1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996Year

Land

ings

('00

0 t)

BycatchTarget

Figure 6. Estimates of annual global landings of swordfish, by targeted catch and bycatch (FAO 1999). SeeFigure 3 for an explanation of how we assigned the proportion of bycatch to each nation’s landings.

Bureau of Rural Sciences32

ReferencesDavenport, D., Johnson, J. and Timbrook, J. (1993). The Chumash and the swordfish. Antiquity,

67(255), pp. 221–22, 257–72.

Di Natale, A. (1991) Interaction between marine mammals and scombridae fishery activities: TheMediterranean case. In GFCM–ICCAT. Report of the GFCM–ICCAT Expert Consultationon Evaluation of Stocks of Large Pelagic Fishes in the Mediterranean Area, Bari, Italy, June21–27 1990. Food and Agriculture Organization Fisheries Report No. 449.

FAO (1999) Global production statistics 1950–1997. <ftp://fao.org/fi/stat/windows/fishplus/fstat.zip> (accessed on 20 January 2000). The database includes data up to1995 from the Former FAO Yearbook of Fishery Statistics, Catches and Landings.Volume 80. Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome.

Folsom, W.B., Weidner, D.M. and Wildman, M.R. (eds) (1997) World swordfish fisheries: Ananalysis of swordfish fisheries, market trends and trade patterns, past-present-future.Volume I. Executive summary. United States Department of Commerce, NOAA TechnicalMemorandum NMFS–F/SPO–23.

Gibson, C.D. (1998) The broadbill swordfishery of the Northwest Atlantic: an economic andnatural history. Ensign Press, Maine.

Hanan, D.A., Holts, D.B. and Coan, A.L. Jr (1993) The California drift gill net fishery for sharksand swordfish, 1981–82 through 1990–91. State of California, The Resource Agency,Department of Fish and Game. Fish Bulletin No. 175.

Hoey, J.J., Conser, R.J. and Bertolino, A.R. (1989) The western North Atlantic swordfish.Audubon Wildlife Report, 1989/1990, pp. 457–77.

Ito, R.Y. and Coan, A.L. Jr (1999) U.S. swordfish fisheries of the North Pacific Ocean. pp. 19–38 in DiNardo, G.T. (ed.) Proceedings of the Second International Symposium onSwordfish in the Pacific Ocean. Southwest Fisheries Science Centre Administrative ReportNOAA–TM–NMFS–SWFSC–263. National Marine Fisheries Service, Honolulu.

NMFS (1999a) Annual commercial landing statistics. Fishery Market News.<http://www.st.nmfs.gov/st1/commercial/landings/annual_landings.html> (accessed 7 April2000).

NMFS (1999b) Atlantic swordfish overview. Facts about Atlantic swordfish.<http://www.nmfs.gov/sword.html> (accessed 21 April 1999).

NMFS (1999c) 1989–1998 United States Wholesale Swordfish Prices (Fulton Fish Market).Fishery Market News. <http://www.st.nmfs.gov/st1/market_news/index.html> (accessed7 April 2000).

Penny, A.J. and Griffiths, M.H. (1998) A first description of the developing South African pelagiclongline fishery. Working paper SCRS/98 presented at the SCRS Swordfish WorkingMeeting. ICCAT, Madrid.

Pickard, G.L. (1979) Descriptive physical oceanography. 3rd (SI) edition. Pergamon Press,Oxford.

Sakagawa, G.T. (1989) Trends in fisheries for swordfish in the Pacific Ocean. In Stroud, R.H.(ed.) Planning the Future of billfishes: Research and management in the 90s and beyond.Proceedings of the Second International Billfish Symposium, Kailua–Kona, Hawaii,August 1–5 1988. National Coalition for Marine Conservation, Savannah.

Sun, C.L., Yeh, S.Z., Wang, S.P. and Chang, S.K. (1999) A review of Taiwan’s swordfish fisheryin the Pacific Ocean. Working document ISC2/99/1.41 presented at the Second Meeting ofthe Interim Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species in the North PacificOcean (ISC), January 15–23 1999, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Fishery overview

Swordfish fisheries 33

Takahashi, M. and Yokawa, K. (1999) Brief description of Japanese swordfish fisheries andstatistics in the Pacific Ocean. Document ISC2/99/SWO1 presented at the meeting of theSwordfish Working Group of the Interim Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna–likeSpecies in the North Pacific Ocean, 15–16 January 1999.

Von Brandt, A. (1984) Fish catching methods of the world. Third edition. Fishing News Books,Surrey.

Wildman, M.R. (1997) World Swordfish Fisheries: An analysis of swordfish fisheries, markettrends and trade patterns, past-present-future, Volume III – Asia. United States Departmentof Commerce, NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS–F/SPO–25.

![Hpce Manual [eBook] - Harpoon](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/55cf9d68550346d033ad7e56/hpce-manual-ebook-harpoon.jpg)