2-Moroko.pdf

Transcript of 2-Moroko.pdf

-

7/28/2019 2-Moroko.pdf

1/6

Employer Branding The Case For A Multidisciplinary Process Related EmpiricalInvestigation

Lara Moroko, Mark Uncles, University of New South Wales

Abstract

There is growing recognition of the role employees play in the development and success of acompanys brand. This is encapsulated in the notion of employer branding. Based on a reviewof previous studies, the internal and external effects of employer branding are conceptualised.A critical assessment of the conceptualisation shows that while it has much merit, there aresignificant gaps and limitations. This paper argues for a more systematic approach that putsprocess-related issues at the centre of the investigation. The need for a study of themechanismsunderlying the process of employer branding at the firm and individual (employee) levels isrequired to address key questions, including the nature of and sufficient and necessaryconditions for successful employer branding processes. Methodological implications are also

discussed.

Employees the Emerging Force Behind Effective Brand Management

In recent years, increasing attention has been given to the critical role employees play in thedevelopment and success of a companys brand. In this context brand is defined as arecognisable and trustworthy badge of origin and also a promise of performance (Feldwick,1991, p.21). Employees ongoing personal contact with consumers gives them a great deal ofinfluence over the way in which consumers view the company (Kennedy, 1977; Stuart, 1999;Dowling, 2001). Employees also have the ability to help build strong and enduring brands,particularly within the services sector (McDonaldet al, 2001; de Chernatonyet al, 2003).

As such, employees are becoming a recognised determinant of successful brand management.Recruiting and retaining employees who can consistently represent the brand in interactionswith clients is now accepted as a significant source of competitive advantage (Chamberset al,1998; Michaelset al, 2001). Recognising this, Ambler and Barrow (1996) and Ewinget al(2002) have introduced the concept of the employer brand. Defined by Ambler and Barrow(1996), the employer brand is the package of functional, economic and psychological benefitsprovided by employment, and identified with the employing company (p. 187). The employerbrand concept unites a broad spectrum of existing thought relating to the way in whichpotential and current employees interact with a companys brand and, in particular, the

companys brand image as an employer (Ambler & Barrow, 1996; Ewinget al, 2002; Lievens& Highhouse, 2003; Freeman & Knox, 2003; Backhaus, 2004; Backhaus & Tikoo, 2004).

Despite growing practitioner and academic interest in employer brands, little is known abouttheprocessof employer branding - specifically theoperation of mechanisms at the firm andindividual (employee) levels that shape and perpetuate the employer brand.

The employer branding process as defined here is an overarching concept. It is inclusive of themechanisms that bring life to the employer brand (i.e., firm level mechanisms that shape anddefine the brand as well as underpin its ongoing implementation). It also includes themechanisms by which potential and current employees interact with the employer band (i.e.

how individuals build associations, brand meaning and ongoing loyalty for the employerbrand). The following section outlines the existing literature on the employer branding process

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 52

-

7/28/2019 2-Moroko.pdf

2/6

and is followed by a discussion of how our understanding may be improved by taking a moremechanism related view.

Our Current Understanding of the Employer Branding Process a Broad View

While a small body of employer branding literature exists, the focus of theses studies has beento define the phenomenon (Ambler & Barrow, 1996; Ewinget al, 2002), consider itsfoundations (Ambler & Barrow, 1996, Backhause & Tikoo, 2004), or examine the outcome ofthe process with respect to recruitment, i.e. employer brand attributes or positioning (Ewingetal, 2002; Freeman & Knox, 2003; Lievens & Highhouse, 2003; Backhaus, 2004).

To establish what may constitute the employer branding process, a broader review of theliterature is required. A number of general marketing concepts would appear to be relevant,including relationship marketing, corporate branding, culture and identity, internal marketingand corporate reputation. In addition, concepts from human resources and organizationalbehaviour literatures, as well as industry journals, are also relevant, illuminating the

relationship between prospective employees, employees and employers.

In reviewing the literature, it is evident that previous studies refer primarily to what can be seenas the effects of the process. These effects relate to external aspects of the organization (i.e.those components that primarily impact external stakeholders, including customers, prospectiveemployees, shareholders or to internal stakeholders (i.e., existing employees).

Effects on interactions external to the firmAt the crux of the employer branding process from the firms perspective is the attraction andretention of the best employees. In this context, best refers to those employees who can addvalue to the company and are able to deliver on the companys brand promise.

In defining the employee value proposition and aligning it with the companys brand promise,the company may attract potential employees with skills and personal values that allow them todeliver on the brand promise and enable them to represent the brand and company in aconsistent way (Ambler & Barrow, 1996; Reichheld, 1996). Thus, employees are able to meetor exceed customers expectations based on brand promise or previous encounters with thecompany (Pringle & Gordon, 2001). By exceeding customer expectations (i.e., by providingpositive disconfirmation) customers attain satisfaction (Woodruffet al, 1983). According toHeskettet al (1994) and others (Yeunget al, 2002; Rust & Zahorik 1993; Anderson &Sullivan, 1993; Dowling, 1994), increases in customer satisfaction can drive increases in

customer loyalty (although this is not automatic).

This, in turn, drives revenue growth and profitability. Shultz (2004) makes a stronger linkbetween employees alignment with the brand promise, customer satisfaction and increases inprofit. Reichheld & Sasser (1990) report a 5% rise in customer loyalty (i.e., a 5% fall indefection) may increase profit from 25%-85%, dependent on the industry under study.

By fostering conditions for profitability and a positive external corporate reputation, theemployer branding process attains an aspect of self-perpetuation. Profitable firms with positiveexternal reputations both attract (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990; Denton 1997) and retain(Michaelset al, 2001) employees who want to share in and be associated with the companys

success.

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 53

-

7/28/2019 2-Moroko.pdf

3/6

Effects on interactions internal to the firmIn actively managing their employer brand, firms can maintain consistency of key brandmessages across stakeholder groups, a practice which may be of value (Duncan & Moriarty,1998). Not only does congruence positively influence the perception of all related messages (toemployees, customers and other stakeholders), it also ensures that employees are properly

aligned with the brand and what it represents (Keller, 2002). This allows employees to livethe brand, delivering on the objectives of the brand/organization (Ouchi, 1981), and reinforcingcorporate values and performance expectations among new and existing staff (Ind, 2001).

The relationship between expectations and behavior has been explored in the employeecitizenship behavior literature. Morrison (1994) contends that employee pro-social behavior(characterized by Bateman & Organ (1993) as employee citizenship behavior) is more likely tooccur when such behaviors are incorporated into role expectations. Furthermore, whenperformance expectations and values are clear a contract is formed between the company andthe employees (Rousseau, 1990). Expected behavior and resulting rewards are explicit,evaluation of staff is objective, good performers are rewarded, nurtured and become satisfied

and loyal (Dowling, 1994; Mendes, 1996; Majoret al, 1995).

Satisfied, loyal employees are more likely to remain with the firm (Heskettet al, 1994) and toshare good views about the company with each other and prospective employees (Reichheld,1996). Positive word of mouth amongst employees assists in building camaraderie within andacross teams, engendering greater loyalty to the firm and to team members (Herman, 1991),thus improving staff retention. Furthermore, existing employees have a large signalingimpact on prospective employees (Rynes,et al, 1991). Positive word-of-mouth helpscontextualize the employment experience for prospective employees, attracting those withvalues that will fit with the brand and allow them to flourish (Chamberset al, 1998; Ind 2001).

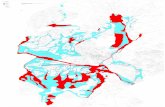

The interplay between internal and external effectsFigure 1 provides a visual summary of key aspects of the internal and external effects of theemployer branding process, as described in the previous sections. Hatch and Shultz (1997)posit that due to networking, business process re-engineering, flexible manufacturing,delayering, the new focus on customer service, the external and internal boundaries of firmsare collapsing (p. 356). Accordingly, there is support in the literature for an interactionbetween the external and internal virtuous circles of the employer branding process.Literature relating to the interaction of internal and external effects is also detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.Virtuous Circles - Internal and External Effects of the Employer Branding

Process

External

effects

Interaction

Internal effects

A. Attract/retain best people

F: Staff/company alignment of performance

expectations, values

B. Employees consistently

representing company

D: Profitability, corporate

reputation enhanced

C: Customers expectations met,

customers satisfied/loyal

G: Satisfied/loyal employees

E: Internal/external comms consistent;

support corporate, employer, product brandsH: Positive word-of-mouth to prospective

employees, teams reinforced

Keller (2000), Gronroos(1990), Gilly & Wolfinbarger(1998), Asif & Sargeant

Ind(2001), Gronroos (1990),Morrison (1994)

Pringle & Gordon (2001),Bansal et al (2001), Grayson&Martinec (2004)

Reichheld (1996), Shershic(1990), George (1990), Kelley(1990), Clark (1997)

Heskett, et al (1994), Uncles(1995), Bolino et al (2002)

Michaels et al (2001)

Chambers et al (1998),Reichheld (1996)

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 54

-

7/28/2019 2-Moroko.pdf

4/6

Multidisciplinary, Process Related Empirical Examination Equally Criticalfor Theorists and Practitioners

This conceptualisation, arrived at by reviewing the academic literature, is echoed in part or inwhole in human resources management and marketing trade publications (see, for example:

Lee, 2002; Linstedt, 2002; Donath, 2001; Simms, 2003; Buss, 2002; Woods, 2001; Hatfield,1999). Agreement between the two bodies of literature could indicate that the benefit ofadditional empirical investigation is minimal. However, the consceptualisation highlights onlya normative, conjectural view of theoutcomeof the process. Taking a truly process-relatedview, which considers the underlying generative mechanisms of the employer branding processand the scope of outcomes that may arise from these mechanisms, is a way in which ourdeficiency of understanding may be addressed. Theorists and practitioners alike would benefitfrom a systematic, multidisciplinary, empirical examination of the following:

A coherent view of the virtuous circles of employer branding in practice

While the literature indicates a range of plausible, even logical outcomes, these outcomes are atbest conjectural. It does not necessarily follow that implementing an employer brandingprocess will result in the outcomes suggested by the existing literature. Employer branding hasnot been studied as a process, i.e. mechanisms at the firm and individual level that constitutethe process have not been examined over time and from the perspective of a variety of relatedactors. While there is support for links between one or more of the components (for exampleHeskettet al, 1994), there is no compelling evidence, as yet, that the virtuous circles operatewholly as specified.

The scope of the outcomes of employer branding

The literature and initial anecdotal evidence indicates that firms undertaking employer brandingexperience positive outcomes, particularly with respect to attracting and retaining desirableemployees. It is not known, however, whether there may also be neutral or negative outcomesattributable to the employer branding process. For example, Aldrich (1999) raises what may bea potentially undesirable outcome of the process. He posits that when there is a high level ofcultural consistency in an organization, organizational growth may be threatened as variation toexisting work practices introduced by employees is likely to be low. Organizational behaviourliterature points to a similar phenomenon where employers hire employees with similarcharacteristics, skills, and attitudes to themselves. This approach is not necessarily beneficial tothe firm as it limits diversity (Robbins, 1996).

Similarly, negative outcomes of the process may arise when employees find their experience ofemployment differs from that promised by the company in communication of the employerbrand. Rousseau (1990) describes a psychological contract as individual beliefs in reciprocalobligations between employees and employees (p.389). Brands, by definition (Feldwick,1991) contain a promise of performance (p.149) which, if unfulfilled in the eyes of theemployee, may have negative consequences for the employee and firm including reduced jobsatisfaction, reduced organizational trust, decreased job performance and increased turnover(Robinson & Morrison, 1995; Robinson & Rousseau, 1994).

Research to date does not shed light on whether there is such a thing as an unsuccessful

employer branding process, i.e. a process that results in negative or counterproductive

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 55

-

7/28/2019 2-Moroko.pdf

5/6

outcomes. Furthermore, the hallmarks of a successful or unsuccessful employer brandingprocess have not been identified.

Mechanisms underpinning the process

As Ambler & Barrow (1996) state, traditional marketing techniques are not directly applicable,

butmutatis mutandisapplicable to the employer brand. This raises the question how do theydiffer and under what conditions?. It is also evident in the review of literature that otherschools of thought and practice may offer techniques outside those traditionally associated withmarketing and branding. Mechanisms can be seen as a systematic set of statements thatprovide a plausible account of how [entities] are linked to each other (Hedstrom & Swedberg,1998; p. 7). Human resources and organizational management literatures, for example, may beshown to be pivotal to the employer branding process, providing mechanisms that plausiblyaccount for the employee and employer interaction.

In order to employ a systemic approach to the examination of the process, mechanisms thatmay combine to create and perpetuate the process need to be identified. This will allow a

focussed and theoretically meaningful analysis of the process in practice. It will also allow astructured comparison of those companies identified as having a successful employer brandwith those having an unsuccessful employer brand to identify variations in the presence andoperation of those mechanisms.

The relationship between employer branding and other branding processes

It is convenient, normatively, to prescribe a series of activities based on the review of theliterature. However, this deterministic approach does nothing to bring us closer to uncoveringthe process as it is grounded in practice. This limits our understanding of sufficient andnecessary conditions for employer brands to succeed, as well as making it difficult to findmethods we may use to judge the level of success. For example, is a successful employerbranding process predicated on a successful corporate or product branding process? Is itpossible to have an unsuccessful employer branding process in the presence of a successfulcorporate or product brand? Conversely, is it possible to sustain a successful employer brandingprocess in the absence of a successful corporate or product brand?

Conclusion

The preceding discussion indicates that a systematic investigation of the employer brandingprocess in practice is indeed warranted. There is substantial indication that the process itself ismultidisciplinary and should be studied across firms functional units. Furthermore, great

insight would be gained from examining the process as it occurs in a variety of firm contexts(e.g., within firms that are regarded as having/not having successful employee brands, andwithin those regarded as having/not having successful corporate and product brands).Qualitative methods that allow focussed comparison of such firms, over time, may bebeneficial in constructing a detailed understanding ofhowthe employer branding processworks and the scope of process outcomes. Using mechanisms identified in extant literature as aframework, data gathered from employees managing the process as well as employees targetedby the process could facilitate an understanding of the operation of firm level mechanisms (eg:management of culture and organisational identity, employee attraction and retention,psychological contracts, internal communication and branding) and individual levelmechanisms (brand attraction, brand meaning, employee/organization identification, loyalty

and organizational citizenship behaviour). This would enable analysis of the mechanismsacross and within specific contexts/firms.

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 56

-

7/28/2019 2-Moroko.pdf

6/6

In contrast to our current view of the employer branding process, taking the proposedprocess/mechanism approach may result in an understanding that has distinct advantages forpractitioners and academics. The resulting research may assist firms in pursuing particularemployer branding strategies by adapting the firm level mechanisms and enhancing the

operation of specific individual level mechanisms. Additionally, it will add to the extantemployer branding, branding process and inter-functional management literature. This in itselfwould be a first step to creating a coherent, meaningful framework of the employer brandingprocess.

Selected Bibliography

Ambler, T. and Barrow, S., 1996, The employer brand,The J ournal of BrandManagement, 4 (3), 185-206.

Backhaus, K. , 2004, An Exploration of Corporate Recruitment Descriptions onMonster.com,The J ournal of Business Communication., 41 (2), 115-120

Backhaus, K and Tikoo, S., 2004, Conceptualizing and researching employer branding,Career Development International, 9 (4/5); 50510

Bansal, H.S., Mendelson, M.B. and Sharma, B., 2001, The impact of internal marketingactivities on external marketing outcomes,J ournal of Quality Management, 6, 61-76.

Ewing, M.J ., Pitt, L.F., de Bussy, N.M. and Berthon, P., 2002, Employment Branding inthe Knowledge Economy, International J ournal of Advertising, 21 (1), 3-22.

Feldwick, P., 1991, Defining a Brand,Understanding Brands, ed. Cowley, D., KoganPage, London, p.21.

Hatch, M. J. and Schultz, M., 1997, Relations between organizational culture, identityand image. European J ournal of Marketing, 31 (7/8), 356-365.

Heskett, J.L, Jones T.O., Loveman, G. W., Sasser, E. W. and Schlesinger, L. A., 1994,Putting the Service-Profit Chain to Work,Harvard Business Review, 72 (2), 164-171

Lievens, F. and Highhouse, S., 2003, The Relation Of Instrumental And Symbolic

Attributes To A Company's Attractiveness As An Employer, Personnel Psychology, 56(1), 75-103

Michaels, E., Handfield-Jones, H. and Axelrod, B., 2001,The War For Talent, HarvardBusiness School Press, Boston

Reichheld, F.F., 1996,The Loyalty Effect: The Hidden Force Behind Growth, Profits andLasting Value, Harvard Business School Press, Boston

Van de Ven, A. H. and Poole, M. S., 1995, Explaining Development and Change inOrganizations,Academy of Management Review, 20 (3), 510-540.

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 57