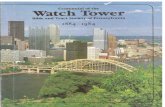

1984.Huesmann Lagerspetz Etal.interveningVariablesintheTeleViol AggRel.developPsych

description

Transcript of 1984.Huesmann Lagerspetz Etal.interveningVariablesintheTeleViol AggRel.developPsych

-

Developmental Psychology1984, Vd 20, No 5. 746-775

Copyright 1984 by theAmerican Psychological Association, lnc

Intervening Variables in the TV Violence-Aggression Relation:Evidence From Two Countries

L. Rowell HuesmannUniversity of Illinois at Chicago

Kirsti LagerspetzAbo Akademi, Turku, Finland

Leonard D. EronUniversity of Illinois at Chicago

Samples of 758 children in the United States and 220 children in Finland wereinterviewed and tested in each of 3 years in an overlapping longitudinal designcovering Grades 1 to 5. For girls in the United States and boys in both countries,TV violence viewing was significantly related to concurrent aggression and signif-icantly predicted future changes in aggression. The strength of the relation dependedas much on the frequency with which violence was viewed as on the extent of theviolence. For boys the effect was exacerbated by the degree to which the boyidentified with TV characters. Path analyses suggested a bidirectional causal effectin which violence viewing engenders aggression, and aggression engenders violenceviewing. No evidence was found that those children predisposed to aggression orthose with aggressive parents are affected more by TV violence. However, a numberof other variables were found to be correlates of aggression and violence viewing.The most plausible model to explain these findings seems to be a multiprocessmodel in which violence viewing and aggression affect each other and, in turn, arestimulated by related variables. Observational learning undoubtedly plays a role,but its role may be no more important than the attitude changes that TV violenceproduces, the justification for aggressive behavior that TV violence provides, orthe cues for aggressive problem solving that it furnishes.

Antisocial aggressive behavior, like manyother behaviors, appears to be overdetermined.Many factorshereditary, paranatal, hor-monal, environmental, familial, and cognitiveonesprobably influence how aggressively achild behaves. Severe antisocial, aggressive be-havior seems to occur most often when there

This research was supported in part by Grants MH-28280 and MH-3I886 from the National Institute ofMental Health to L. Rowell Huesmann, and by grantsfrom the Council of Social Sciences, Academy of Finland(Valtion Yhteiskuntatieteelhnen Toimikunta, SuomenAkatemia) to Kirsti Lagerspetz.

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of PatBrice, Paulette Fischer, Rosemary Klein, and Vappu Vie-mero, who contributed greatly to the operation of theproject and to the analyses of data. Also assisting in thecollection of the data were Birgitta Hagg, Raija-LeenaHolmberg, Patricia Jones, Esther Kaplan-Shain, LiisaKarkkainen, Bo Lillkall, Rebecca Mermelstein, SusanMoloney, Sharon Morikawa, Vita Musonis, Erica Rosen-feld, James Stewart, Ann Washington, and Linda White.

Requests for reprints should be sent to L. Rowell Hues-mann, Department of Psychology, University of Illinoisat Chicago, Box 4348, Chicago, Illinois 60680.

is a convergence of a number of these factorsduring a child's development (Eron, 1982), butno single factor by itself seems capable of ex-plaining more than a small portion of the in-dividual variation in aggression. For example,in a 10-year study of 427 children in NewYork State (Eron, Huesmann, Lefkowitz, &Walder, 1972; Lefkowitz, Eron, Walder, &Huesmann, 1977), no single variable corre-lated more highly than about .40 with aggres-sion (16% of the variance). Yet aggressive be-havior is reasonably stable over time and canbe reliably measured (Olweus, 1979). Thetechnique used to measure aggression in thecurrent study and the Eron et al. 10-year studyyielded an internal consistency of .97, a 1-month stability of .91, and a 10-year stabilityof .38. In Finland, similar findings over a 10-year period have been reported by Pitkanen-Pulkkinen (1981).

One environmental factor to which partic-ular attention has been directed is televisionviolence. In most of the developed countries,the mass media, especially television, have be-

746

-

TV AND AGGRESSION 747

come socializes that compete in importancewith home, school, and the neighborhood. Be-cause violence appears on television to a muchlarger extent than in real life, the TV provideseven more opportunities to experience vio-lence than does real life. Evidence from bothlaboratory and field studies has led most re-viewers to conclude that aggressiveness andviewing violence are interdependent to somedegree (Andison, 1977; Chaffee, 1972; Corn-stock, 1980; Eysenck & Nias, 1978; Hearold,1979; Huesmann, 1982a; & Lefkowitz &Huesmann, 1980). More aggressive childrenwatch more violent television. The relation isnot strong by the standards used in the mea-surement of intellectual abilities, but the re-lation is highly significant statistically and issubstantial by the usual standards of person-ality measurement with children. More im-portant, the relation is highly replicable.

Although the relation between violenceviewing and aggression is clear, the reason forthe relation is notnor has it been establishedthat the relation goes in only one direction.Too often researchers have viewed the causalrelation between violence viewing and aggres-sion as an either/or proposition when, in fact,the causal effect is probably bidirectional.

Does TV Violence EngenderAggressive Behavior?

There can be little doubt that in specificlaboratory settings exposing children to violentbehavior on film or TV increases the likelihoodthat they will behave aggressively immediatelyafterward. Large numbers of laboratory studieshave demonstrated this effect both before andafter the 1972 Surgeon General's report ap-peared (Comstock, 1980). This effect has usu-ally been attributed to observational learning(Bandura, 1977; Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961,1963a, 1963b), in which children imitate thebehaviors of the models they observe. Just asthey learn cognitive and social skills fromwatching parents, siblings, and peers, they canlearn to behave aggressively from watching vi-olent actors. Similarly, children can learn tobe less aggressive by watching prosocial mod-els. For example, in Finland, Pitkanen-Pulk-kinen (1979) showed that the aggressive be-havior of 8-year-old boys could be reduced bywatching films depicting constructive solutions

to conflicts that appear frequently in children'severyday life. The question is whether the pos-itive correlations between violence viewing andreal aggressive behavior found in the field existbecause children are imitating the violent be-haviors they see on TV, or because of one ofthe other processes previously mentioned orfor some other reason.

The Lefkowitz, Eron, Walder, & Huesmannstudy (1977; Eron et al., 1972) provided thefirst substantial evidence from a field settingthat implicated television violence as a causeof aggressive behavior. Without rehashing tiredarguments, the results suggested that excessiveviolence viewing increases the likelihood thata child will behave aggressively. Althoughmany researchers have appropriate reserva-tions about the analyses used to extract causalinferences from these longitudinal observa-tional data (Comstock, 1978; Kenny, 1972),the critiques advocating a complete rejectionof the results (e.g., Armour, 1975; Kaplan,1972) contained such serious errors of rea-soning that they have not had a major impact(Huesmann, Eron, Lefkowitz, & Walder, 1973,1979).

Since the Lefkowitz et al. (1977) study, anumber of other observational studies and fieldexperiments have suggested that violenceviewing is indeed a precursor of aggression(Belson, 1978;Gransberg&Steinbring, 1980;Hennigan et al., 1982; Leyens, Parke, Camino,& Berkowitz, 1975; Loye, Gorney, & Steele,1977; Parke, Berkowitz, Leyens, West, & Se-bastian, 1977; Singer & Singer, 1981; Stein &Friedrich, 1972; Williams, 1978). The one re-cent longitudinal study (Milavsky, Kessler,Stipp, & Rubens, 1982) that led its authors toa conclusion of no causal effect has been in-terpreted by others as suggesting a weak pos-itive effect similar to that found in the abovestudies and in the current study (Cook, Kend-zierski, & Thomas, in press). Even if one con-siders Milavsky et al.'s results to be negative,it still seems reasonable to conclude that ex-posure to TV violence increases a child's ag-gressiveness under many conditions. The ma-jor problem with such a conclusion is that theboundary conditions under which the effectoccurs, as well as the essential precursor andintervening variables, and the processesthrough which they affect aggression are notwell specified.

-

748 L. HUESMANN, K. LAGERSPETZ, AND L. ERON

Culture, Age, and Sex asIntervening Variables

One can hardly consider the boundary con-ditions under which media violence might in-fluence a child's behavior without consideringthe child's culture, age, and sex. Although sub-stantial differences in sociocultural environ-ments exist among the children of any country,many cultural factors remain relatively con-stant. Therefore, to obtain reasonable variationof these sociocultural factors and to test thegeneralizability of any model, one would likea sample that includes subjects from severalcountries. Although a number of researchershave reported results from other countriescomparable to those from the United States(e.g., Belson, 1978; Granzberg & Steinbring,1980; Krebs & Groebel, 1977; Murray & Kip-pax, 1977; Williams, 1978), only a few havestudied the effects of television violence withcomparable methodologies in more than onecountry (e.g., Parke et al., 1977).

Similarly, to determine more precisely howthe relation between violence viewing andaggression develops with age, one must ex-amine multiple cohorts of children longitu-dinally during the periods when the relationis likely to be emerging. A number of re-searchers have attempted to determine the ageat which children are most susceptible to tele-vision violence. Eron et al. (1972) argued thatonce an individual has reached adolescence,behavioral predispositions and inhibitorycontrols have become crystalized to the extentthat a child's aggressive habits would be dif-ficult to change. Collins (1973; 1982; Collins,Berndt, & Hess, 1974; Newcomb & Collins,1979) consistently found that young childrenare less able to draw the relation between mo-tives and aggression and, therefore, may bemore prone to imitate inappropriate aggressivebehaviors. Hearold's (1979) review of the areagenerally supported these views, but suggestedthat the relation between violence viewing andaggression may increase again among adoles-cent boys. Perhaps the more important ques-tion, however, is at what age do children beginto be affected by behaviors viewed on TV.McCall, Parke, and Kavanaugh's (1977) ex-periments indicated that children as young as2 years were facile at imitating televised be-haviors, and some imitation was observed in

even younger children. Singer and Singer's(1981) study, mentioned earlier, provided ev-idence of adverse effects for television violenceon children who were only 3 or 4 years old.

An important finding in early field studiesof aggression and television violence was thatfemales were less affected by violence viewingthan were males (Bailyn, 1959; Eron, 1963).In our 10-year longitudinal study, conductedbetween 1960 and 1970, we found no corre-lation between a girl's violence viewing andher later aggressiveness (Eron et al., 1972). Theexplanations offered for the difference in re-sults for boys and girls have been speculativebut lead to some testable propositions. Onehypothesis would be that observational learn-ing was occurring for boys but not for girlsbecause there were no aggressive females por-trayed on TV. Because Bandura, Ross, andRoss (1963a, 1963b) and Hicks (1965) re-ported that both boys and girls more readilyimitated male TV actors than female actorsin laboratory studies, this explanation seemsunlikely. However, the hypothesis can be testedby evaluating observed programs for male andfemale violence because both types of aggres-sors now appear on TV. A second hypothesisfor sex differences is that females have beensocialized so strongly to be nonaggressive thatTV violence has little effect on them. Underthat theory one might expect girls from cul-tures in which female aggressiveness is moreacceptable to be more influenced by televisionviolence. Thus, an effect might be found nowin samples of American girls even though onewas not found in the 1960s. Third, sex dif-ferences might be due to differences in thecognitive processes of boys and girls. For ex-ample, under several of the explanatory modelstelevision violence would be more likely toelicit aggressive behavior if the violence de-picted were perceived as a realistic response.Because there is evidence that girls think tele-vision violence is less realistic than boys do(Lefkowitz et al., 1977), one would expectthem to be less affected than boys are underthis theory.

Design of the Field StudyIn light of these considerations, a longitu-

dinal, cross-cultural field study was undertakento determine the boundary conditions under

-

TV AND AGGRESSION 749

which the television violence/aggression re-lation obtains, to determine the relevant in-tervening variables, and to shed light on theprocess through which television violenceviewing relates to aggression. Samples fromsix countriesthe United States (N = 758),Australia (N = 289), Finland (N = 220), Israel(Ar = 189), the Netherlands (N = 469), andPoland (N = 237) were included, but completedata presently are available only from theUnited States and Finland. Therefore, theconclusions reported in this article are basedon the data from these two countries only.

In Finland and in the United States twocohorts of children (first graders and thirdgraders) were interviewed and tested threetimes at 1-year intervals. Thus, the span ofGrades 1 to 5 was covered with an overlappinglongitudinal design. Most children's parentswere interviewed during the first wave, andsome were interviewed again during the finalwave. Because both cohorts of children wereinterviewed in Grade 3, developmental effectscan be separated from cohort effects.

Intervening VariablesThe intervening variables selected for at-

tention in this article were chosen for theirtheoretical relevance to the relation betweentelevision violence viewing and aggression.Three have already been mentioned: culture,age, and sex. However, a number of other cog-nitive, familial, and social variables were alsostudied.

Frequency of ViewingOne important mediating variable ob-

viously would be the frequency with which achild watches television in general and the fre-quency with which he or she watches violentprograms in particular. A violent program thatis viewed only once in a while would not beexpected to have as much effect as a violentprogram viewed regularly. Two studies thatwere done in areas where television was re-cently introduced (Granzberg & Steinbring,1980; Williams, 1978), suggested that fre-quency of viewing was a crucial variable. Inthese and in a study by McCarthy, Langner,Gersten, Eisenberg, and Orzeck (1975),amount of television viewed appeared to be a

critical potentiating variable in elucidating therelation between violent television and ag-gressive behavior.

Sex-Typed BehaviorsThe role of culture in socializing the sexes

in regard to the appropriateness of aggressionhas already been mentioned. However, sex isnot always a complete measure of sex-typedbehavior. Girls who are aggressive might, forexample, be more comfortable with the ste-reotypical male role than with the female role.

Identification With TV CharactersAlthough the weight of evidence from lab-

oratory studies (Bandura, 1963a; 1963b;Huesmann, 1982a) seemed to indicate that allviewers are most likely to imitate a heroic,white, male actor, individual differences shouldnot be ignored. It may be that some childrenidentify much more with some actors, and thisidentification mediates the relation betweenviolence viewing and aggressiveness. Such anidentification would be important not just inan observational learning model but also in amodel that emphasizes norms or standards ofbehavior. The more the child identifies withthe actors who are aggressors or victims, themore likely is the child to be influenced bythe scene, believing that the behaviors are ap-propriate and to be expected.

Fantasy

Fantasizing about aggression has seldombeen investigated as a mediator of a positiverelation between TV violence and aggression.Some theorists have argued that a child whoreacts to television violence by fantasizingabout aggressive acts might actually becomeless aggressive (Feshbach, 1964). However, noresearcher has ever reported finding such anegative correlation in a field study. In fact,a more compelling argument exists that fan-tasizing about aggressive acts should lead togreater aggression by the child. From an in-formation-processing perspective the rehearsalof specific aggressive acts observed on TVthrough daydreaming or imaginative playshould increase the probability that aggressiveacts will be performed.

-

750 L. HUESMANN, K. LAGERSPETZ, AND L. ERON

RealityAnother potential mediating variable would

be a child's ability to discriminate betweenfantasy and reality as portrayed on television(Smythe, 1954). Violent scenes perceived asunrealistic by the child should be less likelyto affect the child's behavior according to sev-eral models, and some evidence for such anoutcome has been provided by Feshbach(1976).

IntelligenceIntelligence has often been postulated as a

third variable that might account for the as-sociation between television-violence viewingand aggression; however, the evidence usuallyhas not supported such a thesis. In many ob-servational studies, researchers have measuredand partialed out the effect of intelligence butstill detected a significant relation between vi-olence viewing and aggression (Belson, 1978;Eron et al., 1972; Singer & Singer, 1981).

PopularityIndividual differences in popularity among

one's peers may also play a role in the aggres-sion/violence viewing equation. Previousstudies (Lefkowitz et al., 1977; Schramm, Lyle,& Parker, 1961) have shown that youngsterswho are unpopular or have poor social rela-tions spend more time watching television.Furthermore, in the Lefkowitz et al. 10-yearstudy, evidence was presented implicating lowpopularity as a cause of television viewing.

Parental Roles

Because the parents' social class, education,and aggressiveness might be correlated withthe child's aggressiveness, the role of parentsas mediating variables must also be examined.More interesting than any of these general so-cial variables, however, would be an exami-nation of the parent's television viewing habitsand attitudes and knowledge about the child'sviewing. According to a number of theories,the parent's beliefs about the realism of tele-vision violence might exacerbate or mitigatethe effects television has on the child. Fur-thermore, whether the parent watches whatthe child watches might be indicative of the

parent's concern and attitudes about televi-sion's effect. A number of experimental studieshave suggested that intervention by an adultmight mitigate the effect of violence on thechild (e.g., Hicks, 1968; Huesmann, Eron,Klein, Brice, & Fischer, 1983); however, noevidence of such an effect has been reportedin a field study. Similarly, one would also liketo test whether television-viewing habits aretransmitted from parent to child. There issome evidence that they are (Soneson, 1979;von Feilitzen, 1976), but the question remainswhether parents who watch more violence alsohave children who watch more violence.

Initial AggressionFinally, one might want to consider initial

aggression as a mediating variable as well. Ithas often been written that the effect of tele-vision violence is more notable among childrenpredisposed to aggression (Rubinstein, Coin-stock, & Murray, 1972). The theoreticalmeaning of such a statement is cloudy. If itmeans that severe aggression is an overdeter-mined behavior resulting from the convergenceof many factors, it is as true a statement abouttelevision violence as it would be about anyother cause of aggression. If it means that tele-vision violence only has a noticeable effect onhighly aggressive children, it requires empiricalvalidation. Some evidence is available fromlaboratory experiments both in favor of thepredisposition hypothesis, and contrary to it(Dorr & Kovaric, 1980; Kniveton & Stephen-son, 1973; Surgeon General's Advisory Com-mittee on Television and Social Behavior,1972). In a study by Lagerspetz and Engblom(1979), the aggressive play of aggressive chil-dren showed no increase after the viewing ofviolent film, whereas the aggression of sub-missive and cooperative children did show anincrease. The only available evidence from fieldstudies suggests that the positive relation be-tween violence viewing and aggression occursamong children at all levels of aggression(Huesmann et al., 1973). However, confir-mation of this finding in children from culturesdiffering in attitudes toward aggression wouldbe valuable.

In the next two sections we present datafrom the U.S. sample and contrast the resultswith the data from the Finnish sample. In the

-

TV AND AGGRESSION 751

final section we integrate the results into amodel of the relation between television vio-lence viewing and aggression.

United States StudySubjects

The original group of subjects in the UnitedStates was composed of 672 children in thepublic schools of Oak Park, Illinois, an eco-nomically and socially heterogenous suburbof Chicago, and 86 children from two inner-city parochial schools in Chicago. The poolfrom which these subjects were drawn con-sisted of all the children in the first and thirdgrades of these schools in 1977. The parochialschools were added to increase the ethnic andsocioeconomic heterogensity of the sample,although Oak Park is by no means uniformlymiddle class. In 1977 it ranked 110th in me-dian family income ($19,820) among Chica-go's 201 largest suburbs. Minority enrollmentin the public schools ranged from 5% to 18%,with an average of 14%. Of the two parochialschools, one was composed of a predominantlylower-middle-class Hispanic population andthe other a predominantly lower-middle-classintegrated population. One of the Oak Parkschools was dropped from the study beforeany data were collected because the principalfelt the study would be too disruptive.

Having selected the schools, we compiledclass lists of all first- and third-grade childrenand solicited their parents' permission for themto participate in the study. Through repeatedwritten and personal contacts we raised thefinal permission rate to 76%.' Of the remainingchildren, 14.8% declined to participate,whereas 9.2% never responded. The responserates were similar in all of the schools. Thisprocedure yielded a final pool of 841 childrenfrom which samples could be selected. Eighty-three children were used for pilot testing, leav-ing a sample of 758 for the study.

Of the 758 subjects, who thus constitutedthe United States sample at the start of thestudy in 1977, 384 were girls (207 first gradersand 177 third graders) and 374 were boys (194first graders and 180 third graders). In 1978,for the second wave, 607 children remainedin the sample, and in 1979 for the third wave,there were 505 children. Almost all of the sub-

ject attrition resulted from children leavingthe school systems.

During the first and second waves of datacollection in the United States, parents of 591children were interviewed (177 both motherand father, 378 mother only, and 36 fatheronly for a total of 768 interviews). After thethird wave, one of the parents was reinter-viewed for 300 children (285 mother only, 15father only). An attempt was made to interviewat least one parent of" every child, and thosewho were not interviewed represent the morereluctant parents. Thus, the United States par-ent sample is somewhat biased and excludesless cooperative parents. The effect of this biasis examined in the Results section.

ProcedureThe children were initially interviewed and

tested in the United States during the springof 1977. They were retested during the springof 1978 and 1979. Thus, we obtained data onthe original first grade children in the first,second, and third grades, and on the originalthird grade children in the third, fourth, andfifth grades. This overlapping longitudinal de-sign has the advantage of permitting the testof causal and developmental theories morereadily. Parents were interviewed once duringthe first or second wave and, if possible, againduring the third wave.

Data were collected from four sources: thechild, the child's peers, the school, and theparents. From each child we collected data onhis or her use of fantasy, preferred sex-typedbehaviors, self-rating of aggression, favoritetelevision programs, frequency of viewing fa-vorite programs, identifications with TV char-acters, and judgment of how realistic violentTV programs were. From each child's class-mates we obtained a peer rating of popularity

1 The response rate to our original letter sent in the

mail was 55% Telephone follow-ups raised the rate onlyto about 65% Then, a few days before testing was to begin,we gave a prize to each child for whom a letter had beenreturned, regardless of the decision on the letter. The otherchildren were given another copy of the permission letterto take home and were told that they would receive thesame prize if they returned the letter the next day, nomatter how it was signed. This procedure raised our finalresponse rate to about 91% and our permission rate to76%.

-

752 L. HUESMANN, K. LAGERSPETZ, AND L. ERON

and aggressiveness by the peer-nominationprocedure used in previous studies (Eron,Walder, & Lefkowitz, 1971). In the parent in-terviews we collected data on demographiccharacteristics of the family; child-rearingpractices; and parents' personalities, attitudes,and TV preferences. Most of these parentscales had been used in our previous studies.The variables measured included the parents'education and occupations, the parents' ag-gressiveness as measured by the sum of scales4 and 9 on the Minnesota Multiphasic Per-sonality Inventory (MMPI), hours of TVviewing and four favorite programs (giving aTV violence score), the parents' own viewingof the child's favorite programs, judgment ofhow realistic TV violence is, and the parents'estimates of the child's viewing. The finalsource of data was school records. Data werecollected on the older children's standardizedachievement test performance during the firstwave. The only major change in procedureover the three waves of child interviews oc-curred between first and second grade. Eachfirst-grade child received the peer-nominationprocedure and the television viewing questionsin an individual 30-min session. The othermeasures were administered in group sessions.For the second and higher grades, however,both sessions were group sessions. The indi-vidual sessions for first graders were necessi-tated by their low reading level.

Each group session was conducted by atleast two experimenters and contained nomore than 25 children. The teacher and chil-dren who did not participate in the study werenot present except during peer nomination insplit-grade classes. In these classes childrenfrom the other grades were also used as ratersto obtain enough nominators for valid scores.Each page of the interview booklet was a dif-ferent color, so the monitors could be surechildren were on the correct page. Each answerblank was denoted by a different picture, sothe children could readily keep their place.Each group session required about 40 min.

The parent interviews were conducted in-dividually by research assistants. Some wereconducted in a field office and some in theparents' home. In either case, only the parentand interviewer were present in the room whilethe questions were being asked. For the mostpart, the interviewer read the questions and

recorded the parent's answer. However, theMMPI and a few other sensitive test questionswere placed at the end of the booklet. Theparent read those questions and marked theanswers while the interviewer waited. Parentswho traveled to the field office for interviewswere paid their travel expenses.

Child MeasuresPeer-nominated aggression and popularity

were measured by a slightly modified versionof the Peer-Rating Index of Aggression (Walder,Abelson, Eron, Banta, & Laulicht, 1961): Eachsubject in the sample names all of the studentsin his class who have displayed 10 specific ag-gressive behaviors during the school year. Re-liability as well as concurrent, predictive, andconstruct validity of this measure have beenamply demonstrated (Eron, 1980; Lefkowitzet al., 1977). A slight deviation from the pre-vious use of this technique was the instructionthat subjects were only to consider behaviorsthat had occurred during the current schoolyear. A more major modification was that inthe first-grade classes the procedure as notedabove was conducted individually. These chil-dren nominated their peers by naming orpointing to the appropriate child's picture ona class photograph containing individual pic-tures of each child in the class. Coefficientalpha in the current study calculated only onthe United States sample was .97 and test-retest reliability over one month was .91.

The child's self ratings of aggression werebased on four items in which the child ratedhis or her similarity to fictional children de-scribed as engaging in specific aggressive be-haviors (e.g., "Steven often gets angry andpunches other kids." "Are you just like Steven,a little bit like Steven, or not at all likeSteven?"). Coefficient alpha was .54. Self-rat-ings correlated .38 with peer ratings of aggres-sion in the United States and .39 in Finland.

Sex-typed behavior was indicated by pref-erences for sex-typed toys and games. Thismeasure of preference for sex-typed activities,based on Nadelman's (1974) procedure, madeup a booklet of four pages, each of which con-tained six pictures of children's activities. Twopictures of each set had been previously ratedas masculine, two as feminine, and two asneutral by 67 U.S. college students who had

-

TV AND AGGRESSION 753

been asked to designate the activities as popularfor boys and/or for girls. The task for the chil-dren was to select the two activities they likedbest on each page; they received a score forthe number of masculine, feminine, and neu-tral pictures they chose. The reason for in-cluding a neutral category was that, eventhough less masculine boys may not like tra-ditionally feminine activities, they might preferneutral over traditionally masculine ones.Similarly, for girls, we anticipated that thosewho did not prefer traditionally feminine ac-tivities might also eschew masculine activitiesbut would subscribe to neutral ones. Coeffi-cient alpha is not an appropriate measure ofreliability for this scale. However, one-monthtest-retest reliabilities ranged between .55 and.60. Only the masculine and neutral sex-typedpreferences are included in the present analysesinasmuch as preference for feminine activitiesdid not relate to aggression, either positivelyor negatively.

Aggressive fantasy and active-heroic fantasywere measured by two scales devised by Ro-senfeld, Huesmann, Eron, and Torney-Purta(1982). Each scale has six items, for example,"Do you sometimes have daydreams abouthitting or hurting somebody you don't like?"or "When you are daydreaming, do you thinkabout being the winner in a game you like toplay?". Coefficient alphas for these scales were.64 and .61, respectively, and one-month test-retest reliabilities, .44 and .62.

The children's regularity of TV viewing andTV violence viewing scores were derived fromtheir responses to several lists of programs. Oneach list they were asked to select the one theywatched most. For the program selected, theythen marked whether they watched it once ina while (I), a lot but not always (2), or everytime it's on (3). A child's regularity of TVviewing was computed as the sum of theseresponses for the selected programs. Thus, theregularity score is a measure of the child'sfrequency of viewing his or her favorite showsrather than of hours of viewing.

Violence in favorite television programs wasdetermined from the same program selections.Two psychology graduate students, who them-selves had small children, rated all programsfor the amount of visually portrayed physicalaggression on a 5-point scale from not violentto very violent. Each rater received a paragraph

giving detailed descriptions of what constitutedviolent behavior (e.g., graphically portrayedphysical assaults). Interrater reliability was .75.Previous analyses have shown (Lefkowitz etal., 1977) that this method yields ratings com-parable to those obtained from more objectivecontent analyses (e.g., SignoreUi, Gross, &Morgan, 1982). A child's TV violence scorewas the sum of the violence ratings of showsthat the child had indicated he or she watchedmost, weighted by the regularity with whichthe child reported watching the program.2

In the United States, eight lists of 10 pro-grams each were used to obtain TV frequencyand violence scores. The 80 shows used werethe most popular ones for children ages 6-11during the current year (1977, 1978, or 1979)according to Nielsen ratings. The programswere arranged into lists; each list had an equalnumber of violent programs. The violent andnonviolent programs on a list were equatedfor popularity. An attempt was made to equateviolent and nonviolent programs for time andday of week shown and for sex of the centralcharacter. The one-month test-retest reliabilitywas .75 for frequency and .76 for violenceviewing.

Realism of television programs was ratedby the children. They were given a list of vi-olent shows, including cartoons, and wereasked, "How true do you think these programsare in telling what life is really likejust likeit is in real life, a little like it is in real life, ornot at all like it is in real life?" The subject'stotal realism score was the sum of the ratingson the items. One-month test-retest reliabilitywas .74; coefficient alpha was .72.

Identification with TV characters was de-rived from children's ratings that indicated

2 Several different weightings for frequency were tried

m the test-retest subsample A multiple regression analysispredicting aggression from the product of the frequencyand the violence rating indicated that the strongest relationcould be obtained if violence ratings, scaled from mostviolent (4) to nonviolent (0), were multiplied by frequency,scaled from watching every time its on (10) to watchingonly once in a while (0). This result was cross-validatedwith the enure first wave of U.S data separately for boys& girls. Therefore, for all waves these scalings were usedto compute the violence viewing scores in both countries.In other words, a program that is only viewed once in awhile does not contribute to a child's violence viewingscore, no matter how violent the program is.

-

754 L. HUESMANN, K. LAGERSPETZ, AND L. ERON

how much they believed they acted like certaintelevision characters. These characters in-cluded two aggressive males, two aggressivefemales, two unaggressive males, and two un-aggressive females. For each character, thechildren were asked "How much do you actlike or do things like the character?" The sumof their responses constituted a reliable "iden-tification with aggressive character" score.Coefficient alpha for this measure was .71 andtest-retest reliability over one month was .60.

Parent MeasuresThe parents reported their own and their

spouses' education and occupation. The fa-ther's occupation was coded to obtain a social-class score for the family (Warner, Meeker, &Eels, 1960). Each parent's aggression wascomputed as the sum of Scales 4 and 9 of theMMPI, which has been shown to be a reliableand valid measure of antisocial behavior(Huesmann, Lefkowitz, & Eron, 1978). Theparent's TV violence viewing was calculatedas the sum of violence scores for the four pro-grams listed as favorites and weighted by thefrequency with which the parent reportedwatching them. The parent's judgment of TVrealism was derived in the same way as thechild's. A measure of how frequently the parentwatched the child's programs was obtained byasking the parents how often they watched thespecific programs their children had selectedas their favorites (without telling the parentthis). Finally, the parents estimated both theirown and their children's weekly hours of TVviewing.

ResultsFigure 1 shows how peer-nominated aggres-

sion changed for boys and for girls over thecourse of the 3 years. One can see that in theUnited States the occurrence of peer-nomi-nated aggressive behavior increased from firstto fifth grades as has been reported previously(Eron, Huesmann, Brice, Fischer, & Mermel-stein, 1983). To give this graph more substan-tive meaning, one should remember that anaggression score of .20 indicates that a childwas nominated on aggression questions 20%of all possible times.

Within the United States, the amount ofviolence shown on TV did not change to an

appreciable extent over the course of the 3years (Signorelli et al., 1982). Furthermore,during each year approximately the samenumber of violent shows (25%) was includedin the 80 programs from which the childrenmade their selections; thus, it is appropriateto compare TV violence viewing from year toyear. Figure 2 indicates (as reported previouslyby Eron et al., 1983) that TV violence viewingin the United States sample peaked in the thirdgrade. This suggests that the third-grade timeperiod would be particularly important in thetelevision violence-aggression association.

Violence-viewing scores are more difficultto interpret than are aggression scores. Becauseeach score represents the product of theamount of violence occurring on the selectedshows with the self-reported viewing regularity(i.e., frequency of viewing the shows), the samescore can have somewhat different meanings.For example, a score of 80 (the mean score

40

35

Qua.oo