Foreign Aid, Aid Effectiveness and the New Aid Paradigm: A ...

15. Balance of Payments, Aid & Foreign Investment

description

Transcript of 15. Balance of Payments, Aid & Foreign Investment

2

15. Balance of Payments, Aid & Foreign Investment

Globalization & Its Meaning DC-LDC Interdependence Capital Inflows Balance of Payments Sources of Financing an External Deficit

3

Globalization, Its Contented & Discontented Globalization: expansion of economic activities

across nation-states, including deepening economic integration, increasing economic openness, and growing interdependence among countries in the international economy (Nayyar).

Increasing international integration of markets for goods, services & capital (Rodrik).

Globalization took place during 1870-1913 & in the last quarter of a century.

Recent globalization: strong externalization of services, more rapid expansion of international banking.

4

Recent globalization

Strong externalization of services More rapid expansion of international

banking High share of intra-industry trade Increasing share of international trade that

is intrafirm (between affiliates of the same multinational corporation)

5

Problems with globalization Reduces autonomy of nation-state. Easier to replace domestic workers with foreign

workers. Free flows of capital can undermine LDCs with

poorly developed financial institutions that need to borrow in foreign currencies.

Contributes to marginalization of poorest & those in peripheral economies (such as sub-Saharan Africa).

DC middle classes may face slower income growth, contributing to antiglobalization protests).

6

North-South Interdependence US merchandise imports/GNP increased from 6%

in 1970 to 12% in 1980 to 10% in 1994 & 13% in 2001.

US exports to LDCs increased from 31% in 1970 to 38% in 1975 to 41% in 1981 to 43% in 2001.

Imports from LDCs increased from 25% in 1970 to 42% in 1975 to 46% in 1981 & 2001.

In 2002, 54% of US petroleum consumption was imported, of which 95% was from the third world.

Many other vital minerals came from LDCs.

7

Capital inflows Y=C+I+(X-M)=C+S I+(X-M)=S I=S+(M-X) M-X=F F is capital import (see Table 15-1) I=S+F (see pp. 504-505 for meaning of symbols) Inflow of funds enables country to spend more

than it produces, import more than it exports, & invests more than it saves.

8

____________________-

9

Three-stage Limits Limiting factors by stages: (1) skill limit,

(2) savings gap (I-S), & (3) foreign exchange gap (M-X).

While savings gap is equal to foreign exchange gap ex post (after), stage 2 is likely to be investment limited ex ante (in terms of plans) while stage 3 is likely to be foreign exchange limited.

10

Stages in balance of payments

Newly industrializing countries borrows (young debtor) spending > output, I > S, M > X.

Mature debtor pays back loan if funds used productively, output > spending, S > I, X > M.

Mature creditor [US, the largest debtor in the world but incurring debts in its own currency, is not a creditor so does not fit the “normal” stage approach].

11

International balance on goods, services & income

Exports minus imports of goods & services equal the international balance on goods, services, & income.

Aid, remittances, loans & investment from abroad finance a LDC’s balance on goods & services deficit.

From 1981 to 1999, LDCs had a deficit every year.

12

Sources of financing the deficit

Aid Remittances Foreign investment Loans

(See Figure 15-1)

13

14

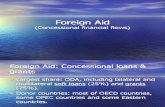

Concessional aid Official development assistance (ODA) includes

development grants or loans (with maturities of more than one year) at concessional financial terms (at least a 25% grant component).

2001: average grant component of OECD bilateral aid to LDCs was 93.8%: $41.0 b grants; $10.4 b X .69 grant component of loans is $7.2b. 41.0 + 7.2/41.0 = 10.4 = 93.8%.

1990s OECD contributed 98% of aid. 2001 aid by OECD 0.22% of GNP, less than half

of 0.70% target.

15

Leading aid givers 1993-2000 Japan gave more foreign aid

than any other OECD country (Figure 15-3).

U.S. led as aid giver 2001 and after. However, U.S. ranked last among OECD

countries in aid as a percentage of GNI, 0.11% (Figure 15-2).

16

17

18

Why give aid? Purpose usually to promote giving nation’s

self interest. Strategic goals: strengthen LDC allies,

shore up donor’s defense installation, improve donor access to strategic materials, & keep LDC allies from changing sides (although military aid is not included in economic aid’s scope).

19

Why give aid? Political & ideological concerns: support a

military ally, influence behavior in international forums, to strengthen cultural ties, or propagate democracy, capitalism, or Islam.

US Point Four assistance in 1949 was motivated by promoting democracy & capitalism & minimizing Soviet influence.

Humanitarian motives (for social justice): emergency relief, food aid, assistance for refugees, grants to least developed countries. Sometimes humanitarian motives overlap with self interest, e.g., in maintaining stable, global political system.

20

Tied aid Tied aid (19.2% of OECD aid) is worth

less than face value (US tied aid – where recipient country must use funds in the donor country – was 75.7% in 1996, the latest year for figures).

21

TABLE 15-2. US Top 10 Recipients of Aid (millions of US$, 2000)

Russia (OA) 1,154

Israel (OA) 967

Egypt 799

Ukraine (OA) 282

Indonesia 194

Jordan 179

Colombia 169

Bosnia and Herzegovina 152

India 148

Peru 136

Note: Aid refers to gross bilateral official development assistance (ODA) and official aid (OA).

Source: OECD 2002b:5.

22

Japan’s aid Increase economic power, export promotion,

resource acquisition, overall economic security, bilateral influence, & recipient’s political stability.

Focus on Asia. Understaffed, politically muddled &

administratively complex. Historical memory of rapid growth shapes aid

programs.

23

OECD top aid recipients

Top 10 recipients of OECD foreign aid 2000 shown in Figure 15-4 (next slide).

24

25

Aid to enhance global public goods Atmosphere (climate) Biosphere Family planning programs Economic sustainability, peace, & security

26

How effective is aid?

May exceed capacity absorption. Can delay self-reliance, contribute to

postponing internal reform, support interests opposing income distribution.

Food aid can undercut local food producers’ prices.

27

How effective is aid?(Easterly)

Much of DC, World Bank, & IMF aid squandered on poorly designed programs.

Loans should have been based on economic reform & good governance.

Little investment in improving lot of the masses. Debt forgiveness for highly indebted poor

countries (HIPCs) “throwing good money after bad money.”

- Easterly was disciplined by World Bank.

28

African aid recipients Morss: in 1970 effectiveness of aid to sub-

Saharan Africa declined: Aid programs placed more burden on scarce local management skills & put less emphasis on recipients’ learning by doing. Malawi hired donor country personnel to manage some projects.

29

African aid recipients Tanzania kept best economic analysts at

home in the late 1980s & early 1990s, but “the price of keeping top professionals at home [was] to see them absorbed into the domestic consultancy market, sustained by donor-driven programmes of [technical assistance].” (Sobhan). Diversion from teaching & domestic policy debate & initiative.

30

African aid recipients ODA not associated with economic growth. Low-income countries in Africa and Bangladesh

are hampered by aid dependence that makes no significant contribution to self-sustained development (Riddell).

Aid needs to strengthen economic policy. Aid has high conditionality, is volatile &

unpredictable, & lacks donor coordination & coherence.

31

How to increase aid effectiveness

Select recipients with well developed institutions & polices & oriented toward economic reform.

Aid for global public goods or building indigenous skills.

Aid for food, agricultural development, debt relief, & cushioning external shocks.

Easterly: opposes aid-givers’ stinginess. Wants donors to select better quality projects.

32

US aid Aid/GNP by US lowest among OECD (Figure

15-2). Has reduced political influence since early 1950s

reduced Congress’s interest in aid? Do Americans lack conviction that increased

LDC security reduces threats to US quality of life?

Has the end of the Cold War reduced the US’s aid competition?

Has the US achieved many of its goals through dominance in the IMF & World Bank?

33

OECD share of aid to low-income economies has fallen

From about 50% in 1972-73 & 1982-82 to 73% in 1992-93 to 30% in 2000-01.

Figure 15-5: on aid to least developed countries and other low income countries

Low-income countries received $10 ODA per capita in 2001; middle-income countries $8.

34

35

Multilateral aid OECD (2001): 36% of aid (0.08% of GNP) went

to multilateral agencies. US (1997): 20% of aid (0.02% of GNP) went to

multilateral agencies. International Development Association, World

Bank’s concessional window, largest giver of concessional aid.

US Congress often objects to US loss of donor control.

36

Food aid

US real food aid fell from the 1960s to recent years.

US real agricultural aid also declined. Three-fourths of food aid in 1980s and 1990s

went to low-income countries, amounting to one-third of their cereal imports.

While food aid has frequently saved lives, it can increase dependence, promote waste, not reach the most needy, and dampen food production.

37

Food aid International Food Policy Research Institute

(IFPRI, 1997): donors should replace program food aid with cash assistance for commercial food import or buying locally. Cash aid is fungible, increasing the recipient’s real resources.

Need focus on long-term agricultural research & technology in LDCs. Little DC agricultural research is applicable to the ecological zones of LDCs. Green Revolution of 1960s through 1990s in India, Pakistan, the Philippines, & Mexico emphasized aid to LDC agricultural research & might be a model for future DC aid to LDCs.

38

Workers’ remittances World migration pressure is high & rising,

analogous to a pent-up flood, increasing as the tap widens from increasing wage gaps between DCs & LDCs.

2003: 175 million people were living outside their own country; 1973: only 75 million people.

Remittances from nationals working abroad help finance many LDCs’ balance on goods, services & income deficits.

39

Workers’ remittances Workers’ remittances/total inflows to LDCs

24.9% in 2001, a “brain gain.” In low-income economies, remittances/GDP

26.5% Lesotho; 16.2% Nicaragua; 16.1% Yemen; 15.0% Moldova; 8.5% Honduras; 8.5% Uganda. Tajikistan migrant workers to Russia sent back $200-300 million, more than total government revenues (see Figure 15-6 for relative importance of remittances and Figure 15-7 for leading remittance recipients).

40

41

42

Private Investment & Multinational Corporations (MNCs)

While real aid to LDCs fell during the 1990s, foreign direct investment (FDI), 74% of total resource flows to LDCs, increased (Figure 15-1).

Private FDI consists of portfolio & direct investment.

MNCs, business firms with a parent company in one country & subsidiary operations in other countries, are responsible for much of direct investment.

43

MNC intrafirm trade/international trade In 1999, 36% of US exports were intrafrim

exports; in Japan 31%. Exports of US affiliates/China’s exports 36% in

1998. See Figure 15-8 on US affiliate export share. DCs 71% of FDI inflows, 75% of FDI outflows,

& large share of international trade. But emerging countries (Taiwan, Korea,

Singapore, China, India & Brazil) are beginning to be a factor in FDI.

44

45

DCs’ FDI Figure 15-9: in 2000, 56% of FDI in LDCs is

from high-income OECD countries, 9% from high-income non-OECD countries, & 35% from LDCs.

US 52% of world’s stock of outward FDI in 1971, 40% 1983, 25% 1993, & 16% 2001 (leader all these years although European Union [38%] had more than twice the US’s 2001 figure).

US largest inward and outward FDI flows in 2001. When Hong Kong is included, China ranked 2nd in inward flows in 2001 (first among LDCs).

46

47

Global production networks (GPNs)

World Bank (1997): participation in the global production networks established by multinational enterprises provides developing countries with new means to enhance their economic performance by accessing global know-how and expanding their integration into world markets.”

48

Private capital flows to LDCs However, net private capital flows to LDCs, $168

billion, 2.8% of LDCs’ GNI in 2001, a fall the percentage in 1990 (percentage for low-income countries fell even more because of low credit ratings).

Private capital flows are highly volatile, especially in countries that have liberalized their financial markets (e.g., Asian crisis of 1997-98).

49

Advantages of FDI No future debt service Transfer of technology Aids balance of payments Management & entrepreneurship Creates forward & backward linkages Trains domestic managers & technicians Provides contacts with overseas banks, markets,

& supply sources

50

Changes LDCs need

Institutional changes to facilitate foreign & domestic investment (especially to become part of GPNs), & participate in the new international division of labor created by outsourcing by high-income OECD countries).

51

Costs of FDI & MNCs

Technological dependence Unsuitable technology Diversion of local skills from domestic

entrepreneurship & innovation

52

Alternatives to MNC technology transfer Joint MNC-local country ventures Management contracts Buying or licensing technology Buying machinery from MNCs

53

Sanjaya Lall (1985) Correct strategy must be judicious & careful

blending of permitting MNC entry, licensing & stimulation of local technological effort.

Stress must be to keep up with best practice technology & achieve production efficiency which enables local producers to compete in world markets.

MNCs’ presence are necessary in some cases but not in others.

54

Loans at Bankers’ Standards Ratio of official aid to commercial loans declined

from 1970 to 1984; then increased from 1984 to 2001. This recent increase mostly reflected the fall in commercial lending rather than rise in official aid.

All but a small fraction of commercial loans were to middle-income countries with high credit rankings.

Very small share to least developed countries (LLDCs) (Figure 15-10).

55

56

Funds from multilateral agencies World Bank, founded in 1944, is well

established in world capital markets.

57

International Monetary Fund IMF, established in 1944, provides ready credit to

LDC with balance of payments problems, equal to reserve tranche, the country’s original contribution of gold or convertible foreign exchange.

Beyond that, credit lines has been increasingly conditioned on a macroeconomic program to overcome international payments difficulties.

58

IMF Various special facilities. Since 1986-88 structural adjustment facility,

renamed the Poverty Reduction & Growth Facility (PRGF) to foster durable growth.

IMF credit depends on collective vote in which high-income OECD has a substantial majority.

US, with 17.5% of IMF shares, is dominant. Econometric studies (Thacker, Barro & Lee)

show that political interests of US substantially drive IMF lending.

59

IMF & World Bank programs for LDC loan recipients Sachs: IMF & World Bank cannot force good

governance with average of 117 loan conditions. Programs don’t diversify production & promote exports in Africa. Too much emphasis on low inflation.

Cramer & Weeks: standard IMF & World Bank packages (macroeconomic stabilization & structural adjustment) cut economic growth, reduce role of the state, & increase probability of political instability.

60

IMF & World Bank programs Barro & Lee (2002): IMF lending has no effect

on growth during its 5-year program but a significantly negative effect on growth in subsequent 5 years.

Independent Evaluation Office of IMF (2004): IMF needs greater flexibility to accommodate countries’ political & administrative systems & constraints. Recipient countries should define own objectives.

61

IMF policies Krugman criticizes IMF for priority in Thailand,

Indonesia, Korea, & other Asian countries in crisis in 1997 on raising taxes & cutting spending to reduce budget deficits and raising interest rates, adding tongue-in-check that “governments [must] show their seriousness by inflicting pain on themselves.”

Policies reduced demand, worsening recession & feeding panic.

62

IMF Recently may have been putting more emphasis

on growth & efficiency & less emphasis on reducing domestic demand & attaining external balance.

Rogoff: just because we see doctors around plagues doesn’t mean they cause them: just because IMF lending accompanies LDCs’ austerity doesn’t mean the IMF is the cause.

The IMF must be satisfied that a borrower can repay a loan.

63

Perverse capital flows: from LDCs to DCs Lucas (1990): “Why doesn’t capital flow from rich to

poor countries?’ Marginal productivity of capital should be higher in capital-scarce, labor-abundant economy such as India than in the US, a capital abundant country.

Lucas: DC capital in LDCs encounters capital market imperfections & restrictions, specifically, economic institutions and policies and political risks that make it difficult to enforce international borrowing agreements.

64

Perverse capital movements

Technology not the same in DCs & LDCs. Technology needs to be modified when shifted to

a different economy & culture. Capital flight is rampant in LDCs. Reinhart & Rogoff (2004): political & credit-

market risks in many LDCs. Show that number of years a country has been in default during the last 55-60 years is central in explaining capital flows & per-capita income levels. Perhaps “too much capital . . . is channeled to ‘debt-intolerant’ serial defaulters.”

65

Massive capital flows to the US – Why? Since 1985, the US has been the world’s largest

debtor. By the end of 2003, US gross external debt, a

stock concept that represents the accumulation over time of international deficits, was $6,800,485 million (US Treasury 2003).

In 2003, the US’s current (income) account deficit represented 10% of the rest of the world’s savings (World Bank 2003e:37).

66

Why were there massive capital flows to the US? Because of the widespread use of the dollar for

international payments and reserves and its attractiveness to international investors, foreigners want to hold financial assets in the US.

The US is able to finance its international deficit in goods, services, & income in its own currency, US dollars.

In 2003, Catherine Mann thought the continuing deficit and large debt were unsustainable. Alan Greenspan thought that the US continuing external deficit makes it vulnerable to foreign asset holders.