Acute hemorrhagic cholecystitis with gallbladder rupture ...

Acute Cholecystitis: *

Transcript of Acute Cholecystitis: *

Acute Cholecystitis: *

An Experimental Stuidy

SA-m E. STEPHENSON, JR., M.D., CARL B. NAGEL, M.D.

From the Department of Surgery and the S. R. Light Laboratory for SuirgicalResearch, Vanderbilt University School of AMedicinie, Nashiville 5 Tennessee

"THE PATHOLOGICAL problems presentedby that profitable stone quarry, the gall-bladder, are numerous and varied. . . Inthe past far too much stress has been laidupon the presence of calculi. Calculi areincidental, not essential, to gallbladder dis-ease." 8 This statement by William Boyd in1923 summarizes much of our inadequateknowledge covering the pathogenesis ofexperimental and clinical acute cholecysti-itis from the time of John Hunter to thepresent.The problem of priority between stones

and an inflammatory response is still un-settled. It seems reasonable to assume, how-ever, that with the exception of certainmetabolic diseases, most cases of acutecholecystitis with or without cholelithiasishave the primary defect of an inflammatoryreaction predisposing to stone formation ata later date.Many factors have been implicated in

the past as being the major cause of acutecholecystitis. This group of experiments isdesigned to evaluate a number of factorswhich may or may not be of importance inthe development of this disease in the ex-perimental animal.

Procedure

Randomly selected adult mongrel dogswere anesthetized with pentobarbital so-dium, 15 mg./kg. body weight. A standard-

*Presented before the Southern Surgical As-sociation Boca Raton, Florida, December 4-6,1962.

ized operative procedure was then carriedout on each of 60 animals. The abdomenwas opened through an upper midline in-cision and the gallbladder and cystic ductexposed. Care was taken to isolate thecystic duct from the surrounding arteryand veins. If vascular injury occurred, theanimal was excluded from the study.The gallbladder in most groups was then

cannulated through the cystic duct withthe withdrawal of 8.0 to 10 cc. of bile forpH determination and quantitative bac-teriologic cultures. An equal amount ofmaterial to be evaluated was injectedthrough the same needle. In most cases thecystic duct was then ligated. The woundswere closed. No antibiotics were given andall animals were sacrificed at 48 hours. Thegallbladders were removed intact, and bilewas aspirated under sterile conditions forrepeat pH and bacteriological studies.

Eleven different combinations of stresswere employed:

I. Ligation of the cystic duct after injection ofautogenous pancreatic juice;

II. Ligation of the cystic duct after injectionof autogenous gastric juice (two of these animalshad a previous vagotomy and showed no essentialchange from the unvagotomized gastric juice);

III. Ligation of the cystic duct after injectionof normal saline;

IV. Ligation of the cystic duct followed by afatty meal;

V. Ligation of the cystic duct following the in-jection of 0.1 N hydrochloric acid;

VI. Ligation of the cystic duct following theinjection of 1.0 per cent phenol;

687

688TABLE 1. Percentage of Grad

the Gallbladder Wall

Group SE

Gastric secretionw-ith ligation

Panicreatic secretionwvith ligationi

Pancreatic enzvineswvith ligation

Saliniewitlh ligation

CGastric secretionwkvithout ligation

Pancreatic secretionwithout ligationi

VII. Ligation of the c!injection of 25,000 units o

VIII. Ligation of the cinjection of 90 mg. of tryp

IX. Ligation of the cyinjection of 25,000 units of

X. Injection of gastricof the cystic duct;

XI. Injection of pancr(tion of the cystic duct.

Resu

The desire to haveamong the various agnecessitated the exclus

STEPHENSON AND NAGEL Annals of SurgeryMlay 1963

'ed Microscopic Changes in expired before the scheduled time of sacri-of Selected Groups fice. Although an occasional animal in

IPercentage of Animals various groptps expired, the onlv deathwvith Patlhological r *Cliange rates of significance vere in the grouips

e Mereloderate Nonie with ligation and gastric juiice (46 c' ) or

71 29 0 trypsinogen (50c).Perforation of the gallbladder occurred

84 16 0 only twice, on both occasions following theinstillation of gastric jtuice combined with

83 17 ligation of the cystic duct.16 66 16S The determination of bile pH had no

definite correlation between the degree of28 57 15 inflammatory reaction and varied little

from the preoperative measurement irre-25 75 0 spective of the material injected. The aver-

age pre-injection pH was 7.3, with a rangeof 5.8 to 7.7. The average pH at sacrifice

ystic duct following the was 7.1, with a range of 5.3 to 7.9. The re-f chymotrypsinogen; sults were not consistent in any groupystic duct following the though the groups receiving gastric juice)sinogen; and hydrohlori cended to show

zstic duct following the and hydrochloric acid tended to showtrypsin; slightly lower pH values. These figuresjuice without ligation were not statistically significant.

eatic juiee without liga- Bacteriological studies were also unre-wvarding. Three of 32 animals had positivecultures initially, and 72 per cent of the

[lts animals had a positive culture at sacrifice.

a comparative study Again there was no correlation between;ents and maneuvers the severity of the reaction in the gall-sion of animals who bladder -wall and the presence of a positive

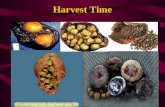

FIG. 1. Three examples of the gross changesproduced by ligation of the cystic duct and injec-tion of pancreatic juice (829), pancreatic juicewithout ligation (830) and gastric juice withoutligation (831).

67 .... , ..

FIG. 2. Two illustrative gross specimens demon-strating the changes at 48 hours with a ligatedcystic duct following the injection of gastric juice(678) and pancreatic juice (679).

Volume 157Number 5

ACUTE CHOLECYSTITIS 689

FIG. 3. A composite of photomicrographs demonstrating the microscopic changes produced in theexperimental study. A. Normal gallbladder wall. B. Changes with the injection of trypsinogen demon-strating mucosal and submucosal edema and intramural hemorrhage. C. Gastric juice with normalmucosa and marked edema and congestion of the wall. D. Typical changes following the injection ofpancreatic juices demonstrating normal mucosa in disruption of the normal submucosal architecture.

bacteriological culture. The most frequentorganisms recovered were streptococcusfecalis and staphylococci.

In each of the 11 groups of animals therewere pathological changes of acute chole-cystitis developing in varying degree in thegallbladder wall as seen by both gross andmicroscopic examination. The gross re-sponse varied from edema and injection tofrank gangrene (Fig. 1, 2). Microscopicallyall sections were graded as to the degree ofinvolvement present. Table 1 represents thepercentage of change present in selectedgroups with comparative grading as tosevere, moderately severe, or normal frommicroscopic evaluation. For this evaluationsevere change represents involvement of alllayers of the gallbladder wall with associ-ated intramural hemorrhage; moderatelysevere changes indicate the lack of involve-

ment of the mucosa; and normal refers tono abnormality or minor amounts of peri-toneal reaction believed to be secondary tothe operative procedure (Fig. 3).

Severe changes in the cystic wall werenoted in at least one animal of each group.Groups I, II, and VIII, receiving pan-creatic juice, gastric juice, and trypsinogenrespectively, demonstrated the most severemucosal involvement. Each of these threegroups had ligation of the cystic duct as-sociated with the injection.Of particular interest in the study are

Groups X and XI in which gastric or pan-creatic juice were injected without manipu-lation or ligation of the cystic duct. All ofthe animals receiving pancreatic juice and85 per cent of animals receiving gastricjuice in this manner developed severe ormoderately severe gross and microscopic

690 STEPHENSON AND NAGEL

changes. Most previous reports 13, 15, 24, 31

have noted the necessity of cystic duct ob-struction for the development of experi-mental actute cholecystitis. Exceptions to

this are the reports of Mann '9 and Aron-sohn 5 referred to in the discussion. Inanalyzing these two groups of animals, one

concludes that the reflux of pancreatic juiceor gastric juice up the unobstructed chole-dochus or cystic duct could precipitate in-flammatory changes in the gallbladder wallmicroscopically identical with acute chole-cystitis. This occurs with or without thepresence of bacteria, with or without a

perihilar inflammatory response, or with or

without vascular insufficiency either fromthe arterial or venous aspects.The results of this group of experiments

demonstrate that a number of both physio-logical and extraneous agents are capableof producing the gross and microscopicchanges associated with acute cholecystitisin the dog. It seems fair to assume that,especially concerning the physiologicalagents, the same progression of changesoccur in the human. The high incidence ofsevere and moderately severe reactions inthe wall of the gallbladder following theinjection of whole pancreatic juice, as wellas purified pancreatic enzymes (trypsin,chymotrypsinogen, and trypsinogen), sup-

ports the data suggesting that a common

pancreatico-choledochal channel not onlyincreases the incidence of pancreatitis frombile reflux, but also increases the incidenceof acute cholecystitis from pancreatic re-

flux and may then in part predispose tocholelithiasis. The factor of greater interestto the authors, however, is that of gastricjuice. In the majority of patients no func-tional common channel exists. In all pa-tients the amount of gastric juice propelledinto the duodenum far exceeds the amountof pancreatic juice present. When refluxoccurs, the experimental data presentedsuggests that gastric juice could be a pre-cipitating factor in certain cases of acutecholecystitis.

Annals of SurgeryMay 1963

The added factors of stasis and increasedteinsion in the gallbladder secondary to ob-struction of the cystic duct accentuate thepathological changes with most of the ex-perimental soluitions hutt are not necessaryfor the development of the disease process.

DiscussionThe goal of many thoughtful investiga-

tive studies is to arrive at a truthful conceptof the basic etiology of a specific disease.Only from an understanding of the causemay the mechanisms and manifold expres-sions of that disease be comprehended andrational therapy envisioned and instituted.The pursuit of etiology is a goal fraughtwith difficulty and error, for it involves therecognition, accumulation, and above all,the interpretation of facts.

In medicine there are two great avenuesof investigation: clinical and experimental.They are the practical tools we possess.Clinical studies are valued because theyare based on broad and all-inclusive mate-rial. Experimental studies are designed toreduce perceptible variables to a minimum.They are valued for this reason. The ir-relevant is pared away. Both may be criti-cized; the former as having too many vari-ables, the latter as having too few. It islittle wonder that the etiology of disease,both common and uncommon, so often re-mains contentious or unknown.

For a great many years acute cholecys-titis was explained on the basis of bacterialinfection. It was a dominant and persistenttheory, and it has succeeded in followingus into the modern age. We have attackedand altered it, but we have not eliminatedit.

In the late eighteenth century JohnHunter observed cholecystitis in patientsstricken with typhoid fever. A hundredyears later the implications of Hunter'sfinding received tremendous impetus fromthe discovery of bacteria and the evolutionand application of the Koch postulates. In1881 Carl Eberth described the typhoid

Volume 157 ACUTE CHNumber 5

bacillus. Typhoid cholecystitis became aninescapable concept when, in 1909, Kochdiscovered clumps of Eberthella typhosain the wall of the acuitelv inflamed gall-bladder.The news spread widely. Hertzler 14

states: "It was a common experience in thedays of typhoid epidemics that the oldfamily doctors regularly palpated the upperabdomen searching for gallbladder tender-ness when the fever extended beyond theusual period."The fact that cholecystitis might occur

years following recovery from typhoidfever seemed an extraordinary but explica-ble quirk of nature; bacilli could still berecovered from the bile or gallbladder wallin such cases.26

Osler cast the first serious doubts uponwhat appeared to be a proven theory. Heemphasized that acute inflammation of thegallbladder was, in fact, a rare occurrencein typhoid fever. Moreover, it frequentlyappeared when the latter was absent. Theforce of this dissenting voice was partiallylost when a variety of other organisms wereassociated with the disease.17' 22 The dis-covery that the bile or tissues from the wallof the inflamed organ were often sterile,3 22questioned the validity of these early con-cepts. It precipitated a search for otherfactors.

Surgeons and pathologists became in-trigued by the observation that the morpho-logic changes in cholecystitis were mostoften concentrated in the outer coveringsof the organ. The mucosa was frequentlyintact and seemingly uninjured.3'8'23 Con-tact infection through the mucosa appearedunlikely; the infecting organisms or un-known agents in the absence of bacteriamust reach the gallbladder through thegeneral circulation from some distant part.Graham 13 began a series of investigations

using clinical modalities of study. He notedthat periportal hepatitis, presumably bac-terial in nature, was an invariable accom-paniment to acute cholecystitis. Judd 16 SUp_

OL,ECYSTITIS 691

ported and gave added weight to this view.Graham concluded that bacteria reachedthe gallbladder from foci of infection withinthe liver by a process of direct extensionthrouigh the rich lymphatic pathways con-necting the two organs. One theory, widelydiscussed at the time, connected cholecys-titis with acute and chronic inflammationsof the appendix. Graham offered an alter-nate view and also performed a series ofexperiments which touched upon other fac-tors. After introducing large numbers ofcolon bacilli into the gallbladder lumen, henoted that "in order to produce cholecys-titis with any regularity it was necessaryto obstruct the cystic duct or to injure theblood supply by ligation of the cystic ar-tery." 13 This led to the study of circulationand obstruction as etiologic agents.The experimental ligation of the cystic

artery, without other factors being intro-duced, is without effect.28 29 Converselycholecystitis does occur in the presence ofa patent cystic artery.3' Primary vascu-lar pathology, except in bizarre circum-stances as in association with polyar-teritis, appeared and remains unlikely. Itcannot be excluded as a secondary factor,however. Mann 19 produced an overwhelm-ing acute gangrenous cholecystitis in ani-mals by the systemic intravenous injectionof Dakin's solution. The disintegration ofthe organ was entirely due to the disrup-tion of the smaller vessels supplying ordraining the gallbladder wall. The processwas peculiarly selective to the gallbladderand took place with extreme rapidity.Whatever the explanation for this remark-able phenomenon may be, it did stress theimportance of pathological changes in thevasculature in relation to the gross andmicroscopic appearance of the inflamedorgan. The morphology may be compli-cated by necrosis or destruction which fol-lows bacterial infection; it is, nonetheless,always dominated by edema, congestion,and intramural hemorrhage-all expressionsof vascular pathology. Mann's work led to

_ ...

692 STEPHENSON AND NAGEL

a search for naturally occurring physiologicsubstances which might produce a similarselective cholecystitis after introductioninto the general systemic circulation. Thissearch failed.5The toxic effect of bile on tissues out-

side the gallbladder has been well docu-mented.11, 21, 30 Concentrated bile, particu-larly associated with obstruction, is dis-astrous to the gallbladder wall itself.5 8 9, 31

When bile is washed away with saline solu-tion, and the cystic duct obstructed, inflam-mation does not occur.31 These observationssuggest that inflammation in the absenceof bacteria depends upon two factors, theconcentration of bile, and its imprisonmentby obstruction to the outflow tract.30

Experimental studies and clinical ob-servations have proven that pancreatic se-

cretions may reach the gallbladder by re-

flux flow.7' 10, 29, 30 When concentrated ex-

perimentally, whole pancreatic secretionsor active enzyme preparations may destroythe gallbladder wall.9' 5 Still another di-mension is added. Colp 10 suggests bile mayact as a catalyst in the presence of pan-

creatic enzymes. If the concentration ishigh enough, and the reaction swift enough,inflammation results.

Regardless of the factor being studied,be it bile, pancreatic enzymes, or bacterialcontamination, investigators have found itdifficult to consistently produce cholecys-titis in the absence of obstruction.5 7, 15, 23, 28

Some degree of inflammation may be in-duced by the simple intraluminal instilla-tion of high concentrations of a variety ofsubstances. Our own results demonstratethis. To produce necrosis and perforation,however, one must add the factor of ob-struction to the experimental preparation.The overriding importance of this factor

is obvious from the fact that stones are

nearly always found obstructing the cysticor common duct in acute cases of cholecys-titis. Stones are not present in 10 per centof such cases, however, and it is difficultto explain the inflammation or the edema

Annals of SurgeryMay 1963

induced obstruction which may be found.Anatomical variants, such as a long ortwisted cystic duct which suddenly be-comes kinked, may account for some ex-amples. In other cases a more distal ob-struction, often of obscure origin, may befound. Balo 6 reported sphincter of Oddiobstruction secondary to acute or chronicedema of the duodenal mucosa. Lock-wood 18 suggests that stasis eventually lead-ing to edema and obstruction and perhapseven to stone formation may be stronglyinfluenced by physical habitus consistentlyexpressed over a long period of time. Al-varez 1 raises the question of food allergyinducing sphincter spasm of sufficient dura-tion to cause symptoms and cites clinicalexamples to support his view.

Experimental work has provided somepossible answers to the key question of howobstruction occurs in the absence of stones.Archibald 4 produced sphincter of Oddispasm in cats by the application of dilutehydrochloric acid to the duodenal papilla.Aronsohn 5 made the observation that thecystic duct may become obstructed byedema when highly concentrated bile isintroduced into the lumen of the gall-bladder. This work escapes the valid criti-cism that most experimental studies evalu-ating obstruction are based on the artificialuse of ligatures to occlude the cystic duct.How can one piece together the many

varied concepts reviewed and evolve asatisfactory current concept of etiology?The difficulty of the task is somewhatlessened by the fact that all the factors be-lieved at one time or another to be theprime factor are really complementaryrather than confficting or contradictory.The problem resolves into a question ofweighting, of deciding which is the moreor most important. Any one, be it obstruc-tion, bacterial infection, enzymes or otherirritating agents, can produce some degreeof acute cholecystitis in the experimentalanimal. The factor of obstruction, however,must be singled out and weighted most

Volume 157 ACUTE CHOLECYSTITIS 693Number 569heavily. In examples of gangrene and per-foration obstruction is always present. Theevents which lead to this, particularly inthe absence of calculi, remain at least par-tially hidden.A word must be said about time. It per-

vades all and its influence is felt in everyclinical problem and experimental prepara-tion. It may prove to be, in the end, themost critical factor of all.

SummaryA method to produce acute cholecystitis

in dogs is described. This method permitsa comparative evaluation of any numberof materials to be tested.

Physiologic and extraneous substancesintroduced into the gallbladder lumen arecapable of producing the gross and micro-scopic changes of the disease.Autogenous gastric juice and autogenous

pancreatic juice as well as purified pan-creatic enzymes produce similar changesin the gallbladder wall both in regard todegree of edema and necrosis.

Gastric juice and pancreatic juice areboth capable of producing severe changesin the absence of cystic duct obstruction.

Studies of bile pH and bacteriologic cul-tures were inconclusive and the minorchanges observed could not be implicatedin the development of the disease process.

In evaluating the experiments performelit appears that a number of chemical agentswith or without obstruction are capable ofeliciting acute cholecystitis in the dog inthe absence of cholelithiasis; thus, no singlefacet can be isolated and identified as themajor cause of acute cholecystitis.

References

1. Alvarez, XV. C.: Pseudocholecystitis Appar-ently Cauised by Food Sensitivities. Proc.Staff MIeet. MIayo Clin., 9:680, 1934.

2. Anderson, W. A. D.: Pathology. NMosby, 1961,p. 860.

3. Andrews, E.: Acute Cholecystitis. Arch. Surg.,31:767, 1935.

4. Archibald, E.: An Experimental Production ofPancreatitis in Animals as the Result of theResistance of the Common Duct Sphincter.Surg., Gynec. & Obst., 28:529, 1919.

5. Aronsohn, H. G. and E. Andrews: Experi-mental Cholecystitis. Surg., Gynec. & Obst.,66:748, 1938.

6. Balo, J. and H. G. Ballon: Effects of Reten-tion of Pancreatic Secretions. Surg., Gynec.& Obst., 48:1, 1929.

7. Bisgard, J. D. and C. P. Baker: Studies Re-lating to the Pathogenesis of Cholecystitis,Cholelithiasis, and Acute Pancreatitis. Ann.Surg., 112:1006, 1940.

8. Boyd, W.: Cholesterolosis of the Gallbladder.Brit. J. Surg., 10:337, 1923.

9. Boyd, W.: Textbook of Pathology. Philadel-phia: Lea & Febiger, 1961, p. 821.

10. Colp, R., I. F. Gerbin and H. Boubilet: AcuteCholecystitis Associated with Pancreatic Re-flux. Ann. Surg., 103:67, 1936.

11. Dragstedt, L. R., H. E. Haymond and J. C.Ellis: Pathogenesis of Acute Pancreatitis.Arch. Surg., 28:232, 1934.

12. Edwards, C. R., W. H. Gerwig, Jr. and W.L. Guyton: Acute Cholecystitis with Perfora-tion into the Peritoneal Cavity. Ann. Surg.,113:824, 1941.

13. Graham, E. A. and M. C. Peterman: FurtherStudies on the Lymphatic Origin of Chole-cystitis. Arch. Surg., 4:23, 1922.

14. Hertzler, A. E.: Surgical Pathology of theGastrointestinal Tract. Chicago: R. R. Don-nelly and Sons Co., 1936, p. 118.

15. Hjorth, E.: Contributions to the Knowledgeof Pancreatic Reflux as an Etiological Factorin Chronic Affections of the Gallbladder.Acta Chir. Scand. Suppl. 134, 96:1, 1947.

16. Judd, E. S. and E. Phillips: Acute CholecysticDisease. Ann. Suirg. 98:771, 1933.

17. Kelly, A. 0. J.: in Osler's MIodern 'Medicine,Vol. V. Philadelplhia: Lea and Febiger, 1908,p. 817.

18. Lockwood, B. C.: Gallbladder Disease. Rev.Gastroenterology, 19:144, 1952.

19. NMann, F. C.: The Production by ClinicalMIeans of a Specific Cholecystitis. Ann. Surg.,73:54, 1921.

20. 'Meltzer, S. J. and W. Salant: Studies on theToxicity of Bile. J. Exper. Med., 8:127, 1906.

21. Najarian, J. S., D. E. Hive, R. M. Whitrockand H. J. NMcCorkle: Effect of PancreaticSecretions on the Gallbladeler. Arch. Surg.,74:890, 1957.

22. Reid, S. F.: The Effect of Pancreatic Juice onthe Gallbladder. Surg., Gynec. & Obst., 89:160, 1949.

694 STEPHENSON AND NAGEL Annals of Surger.y

23. Robbins, S. L.: Textbook of Pathology. Phila-delphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1962.

24. Robinson, T. NM. and J. E. Dunphy: An Ex-perimental Study of the Effect of Pan-creatic Juice on the Gallbladder. Gastro-enterology, 42:36, 1962.

25. Rolleston, H. D.: Diseases of the Liver andBile Ducts. New York: iMacmillan Co., 1929,p. 1905.

26. Saphir, O.: A Text on Systemic Pathology.New York; Grune and Stratton, 1959.

27. Seelig, M1. G.: Bile Duct Anomaly as a Factorin the Pathogenesis of Cholecystitis. Surg.,Gynec. & Obst., 36:331, 1923.

28. Wagner, D. E., D. W. Elliott, G. L. Endahland C. T. MIacPherson: Specific PancreaticEnzymes in the Etiology of Acute Cholecys-titis. Surg., 52:259, 1962.

29. Westphal, K.: Injury to the Biliary Tract andLiver due to Pancreatic Ferments. Zeit. f.Klin. Med., 109:55, 1929.

30. Wolfer, J. A.: The Role of Pancreatic Enzymesin the Produiction of Gallbladder Disease.Surg., Gynec. & Obst., 53:433, 1931.

31. Womack, N. A. and E. 'M. Bricker: Occlusionof the Cystic Duct in the Pathogenesis ofCholecystitis. Arch. Surg., 44:658, 1942.

32. Zollinger, R.: Acute Cholecystitis. New Engl.J. Med., 224:533, 1941.