Zoo View - Fall 2014

-

Upload

greater-los-angeles-zoo-association -

Category

Documents

-

view

226 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Zoo View - Fall 2014

FALL 2014

Mayor of Los angeLes

Eric Garcetti

Los angeLes Zoo CoMMission

Karen B. Winnick, PresidentBernardo Silva, Vice President

Yasmine Johnson Tyler Kelley

Marc MitchellRichard Lichtenstein, Ex-Officio Member

Los angeLes Zoo adMinistration

John R. Lewis, Zoo DirectorDenise M. Verret, Deputy Director

Cindy Stadler, D.V.M., Acting Director of Health ServicesMei Kwan, Director of Administration and Operations

Tom LoVullo, Construction and Maintenance SupervisorKirsten Perez, Director of Education

Darryl Pon, Planning and Development DivisionDenise Tamura, Executive Secretary

gLaZa offiCers

Betty White Ludden, Co-ChairRichard Lichtenstein, Co-Chair

Nick Franklin, Lori Winters Samuels, Laura Z. Wasserman, Vice Chairs

Phyllis Kupferstein, SecretaryRobert Ruth, Treasurer

Connie M. Morgan, President

gLaZa trustees

Peter Arkley, Margot Armbruster, Charles X Block, Richard Corgel,

Duncan Crabtree-Ireland, Nancy Leigh Dennis, Brian Diamond, Irfan Furniturewala,

Cassidy Horn, Cindy Horn, David V. Hunt,Frederick Huntsberry, Jonathan D. Jaffrey,

Diann H. Kim, Matthew Krieger, Mona Leites, John Manning, Heather Mnuchin, Kathy Nelson, Beth Price, Patricia Silver, Slash, Richard Sneider,

Jay Sonbolian, Erika Aronson Stern, Madeline Joyce Taft, Dana Walden,

Jennifer Thornton Wieland

trustees eMeriti

Willard Z. Carr, Jr., Richard Corgel, Ed N. Harrison,Mrs. Max K. Jamison, Lloyd Levitin, Mrs. John F. Maher,

William G. McGagh, Dickinson C. Ross, Shelby Kaplan Sloan, Thomas R. Tellefsen, Polly Turpin

gLaZa adMinistration

Eugenia Vasels, Vice President, Institutional AdvancementJeb Bonner, Vice President, Chief Financial Officer

Kait Hilliard, Vice President, MarketingAdrienne Walt, Associate Vice President, Advancement

Lisa Correa, Director of MembershipPatti Glover, Director of Special Events and Travel

Brenda Posada, Director of PublicationsPete Williams, Director of Information Technology

ZOO VIEW (ISSN 0276-3303) is published quarterly by the Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association, 5333 Zoo Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90027. Periodical Postage paid at Los Angeles, CA. GREATER LOS ANGELES ZOO ASSOCIATION ANNUAL MEMBERSHIPS: Individual $55, Individual Plus $75, Family $126, Family Deluxe $165, Contributor $250, Wildlife Associate $500, Conservation Associate $1,000, Safari Club $1,500. Each membership category includes unlimited admission to the Los Angeles Zoo, one-year subscriptions to ZOO VIEW and ZOOSCAPE, and invitations to special events. For more information, call (323) 644-4200 or log on to www.lazoo.org. Copyright © 2014 Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association. All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents of this publication without written permis- sion is prohibited. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to ZOO VIEW, 5333 Zoo Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90027-1498.

2

Best Wing ForWard The World of Birds Show is back in a

brand new home. 8

tending the FlockPreventive medicine is key to keeping

the Zoo’s animals healthy.

12

conservation 2.0 New technology leads to advances in

conservation research.

17a halF century oF assessing species The IUCN Red List of Threatened

Species turns 50.

18Jeans For giraFFes

Donated denim benefits giraffe conservation.

18docents are golden

GLAZA’s docent program marks a major milestone.

19Zoo lights

A new evening event promises glamour and glitz for the holidays.

19rainForest at your Fingertips

A new iPhone app enhances a visit to our rainforest exhibit.

20sponsor spotlight

21donor proFile

CONTENTSFall 2014

the Quarterly MagaZine oFthe greater los angelesZoo association

voluMe Xlviii nuMBer 3

inside Front coverOkapi Bomani, the first of his species born at the L.A. Zoo, turned one in September. Photo by Jamie Pham

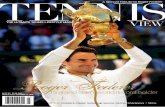

Front coverBateleur eagles have an unusual habit of tipping side to side as they soar, like an acrobat balancing, which is how they got their common name—in French “bateleur” means “street performer.” Photo by Jamie Pham

Back coverA Hawaiian short-eared owl or “pueo” is among the stars of the World of Birds Show. Photo by Tad Motoyama

editor

Brenda Posada

assoCiate editor Sandy Masuo

Web editor Chantel Mikiska editoriaL CoMMittee

Kait Hilliard, Susie Kasielke, John Lewis, Connie Morgan, Kirsten Perez, Eugenia Vasels, Denise M. Verret

Zoo PhotograPher

Tad Motoyama

gLaZa Photo editor

Jamie Pham

design and ProduCtion Norman Abbey, Pacific Design Consultants

Pre-Press Film Craft, Inc.

Printing ColorGraphics

Proofreader Lynne Richter

2

8

12

n u r t u r i n g W i L d L i f e a n d e n r i C h i n g t h e h u M a n e x P e r i e n C e

ZOO VIEW • FALL 2

Settled into a

resplendent new

theater, the staff

and avian stars of

the Zoo’s Angela

Collier World of

Birds Show are

ready to take

the stage.

est wing Forward

by Olivia

GG A blue-and-yellow macaw glides into action.

G Demonstrations of natural bird behaviors captivate audience members.

E Birds and keepers collaborate to make the Bird Show a hit.

JAM

IE P

HA

M

JAMIE PHAM

b y O l i v i a H u m m e r

B

he sun-dappled bleachers of the Angela Collier World of Birds Theater begin to fill. An exotic soundtrack can be heard above the voices of chattering birds and talkative Zoo guests. Hawks and eagles fly overhead, a flock of pigeons surprises visitors with its magnitude, an Abyssinian ground hornbill hops comically across the stage for a reward. Come in; take a seat. The all-new World of

Birds Show is about to begin!The World of Birds Show has been delighting Los

Angeles Zoo visitors for nearly 40 years. After decades of wear and tear, the old set was demolished in 2012 to make way for a new, vastly improved theater. The brand-new Angela Collier World of Birds Theater—built by Fenner Construction and made possible by a

generous gift from the Angela Collier Foundation (see story on page 21)—was completed in April. Shows began soon thereafter with little fanfare, allowing the birds to become gradually comfortable with crowds, which grew larger as word of the show’s return spread.

The new theater features a two-story Mediterranean-style structure, grass-covered stage, a facilities building, and new housing for the birds. The entire performance space was designed to facilitate the birds’ natural behaviors.

The show’s cast includes a wide range of birds, from Lanner falcons to bald eagles. Backstage a cacophony of tweets, squawks, and screams fills the air as they communicate and interact. Baby, a Moluccan cockatoo, and Alvin, a rose-breasted cockatoo, are quick to talk to

T

JAMIE PHAM

JAMIE PHAM JAMIE PHAM

TAD

MO

TOYA

MA

HH The bateleur is one of the world’s most colorful eagles.

G Parrots, like this red-lored Amazon, naturally mimic sounds, including human speech.

H The Hawaiian owl, or pueo, is a subspecies of short-eared owl.

3

4 ZOO VIEW • FALL

strangers, showing off their plumage and impressive mimicry skills by bobbing their heads and clearly saying their names among other words.

Onstage the birds put their best wing forward, showcasing their talents to an excited audience. Birds of prey, such as Harris’s hawks, soar just over the heads of the audience, demonstrating their gliding. Owls fly by, surprising Zoo guests with their swift, silent flight. A perennial favorite carried over from the old World of Birds Show is a contest between Nipper, a yellow-naped amazon, and Paco, a red-lored amazon, to see which bird is the best “talker.” Throughout the show, a rotating cast of keepers serve as host and guest stars, filling the space between behaviors with energetic banter and fascinating facts.

The key to running any successful show featuring wild animals is adapta- bility, and the World of Birds Show is no exception. “It’s problem-solving on a day-to-day basis,” says Lead Keeper Jon Guenther.

One of the first steps in developing a smooth routine is adjusting the new stage to fit the needs of the show. Today,

Babs, a Eurasian eagle owl, misses her mark, choosing to land on a nearby rock instead. The keepers are quick to recognize that a cluster of tall grass had obscured her view of the bait and would need to be adjusted. Details that may seem inconsequential to the average human—the lawn being slightly overgrown, for instance—can present uncomfortable obstacles to the birds.

“Most birds that aren’t really terres- trial don’t run around a lot,” Guenther explains. “Their nails can get caught in the grass.” Such factors can affect the show’s pacing, often causing birds to refuse to complete their behavior or return to their designated keeper. Of course, this leaves it up to that day’s show host to continue to engage the audience, sharing scads of off-script information about the species until our feathered friend has found her way backstage.

Periodic lulls and “misbehaviors” attest to the show’s adherence to its goals. The World of Birds Show is not designed to teach the birds to perform “tricks.” Because this is a free-flight, natural behavior show, no bird is ever forced to act on cue. While the birds are trained to complete certain actions, they are simply demonstrating natural

G The Andean condor is the national bird of Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador.

G G The wreathed hornbill enjoys sunning herself.

G E The bald eagle is one of the largest raptors in North America, second in size only to the California condor.

TAD

MO

TOYA

MA

TAD

MO

TOYA

MA

TAD MOTOYAMA

JAM

IE P

HA

M

5ZOO VIEW • FALL

behaviors in a controlled manner. Harris’s hawks dive to catch lures, as they would snatch smaller birds in midair in the wild, and they demon-strate their keen eyesight by spotting a mousey treat from hundreds of feet away. A cockatoo pushes a golf ball on cue, much as it would push its eggs to safety in the wild. Even the talking parrots are showcasing their uncanny ability to mimic sounds they hear—a trait that allows parrots to communicate with one another in social groups.

The show intends to be as educational as it is entertaining. Interspersed with the stunning aerobatic displays is a strong message of protection and conservation. Many of the featured species, such as the blue-throated macaws, are endangered in the wild due to habitat loss and the pet trade. After Nipper and Paco’s “talk-

off,” the host makes a strong case against keeping parrots as pets. With their long lifespan (many live well over 50 years in captivity), surprising intellect (about that of a human toddler), and propensity for loud screams, parrots are quite high-maintenance.

hen it comes to caring for the 20 birds in the show, along with the other non-performers, the saying “it takes a village” rings true. Each day, a handful of keepers and the occasional volunteer must complete all of what Guenther calls their

“normal keeper duties” before 10 a.m. The birds must be weighed, their enclosures must be hosed down, and their diets must be individually prepared to suit their nutritional needs. From

10 until the show begins at 11:30, backstage is a flurry of movement. The performers must be placed in their proper locations—some are just behind the curtain, others must be driven up to the hillside and placed in release boxes so they can dramatically swoop into the audience’s view. The keepers then bait the stage and audience areas with food to reward the flighty cast for their behaviors. It is a learned skill—a certain amount of finesse and a steady hand are needed to place meaty treats atop 25-foot poles using only a hook! As the new show continues to evolve, birds are continually being added to the line-up. These last-minute changes mean more placing of birds, more baiting, and more lines for the day’s host to remember.

In the midst of it all stands Jon Guenther. He involves himself in each

F Handsome and powerful, lanner falcons have been used in falconry for more than a thousand years.

G World of Birds Show staff and stars engage guests.

W

GEO

RGE

STO

NEM

AN

GEO

RGE

STO

NEM

AN

6 ZOO VIEW • FALL

BILL

KO

NST

AN

T/I

RF

detail—from the order in which the birds will appear to musical cues and dialogue. After 19 years at the Zoo and nearly as many as lead keeper, it’s no wonder that he can remain calm and methodical under pressure. It is clear that he is the show runner—the other keepers look to him for input, advice, and the final word on decisions.

Guenther gravitated toward birds from a young age, keeping cockatiels, parrots, and pigeons as pets. When asked what continues to draw him to the World of Birds Show after nearly two decades, he simply responds, “I like inspiring people,” a sentiment echoed by the rest of his dedicated staff.

The World of Birds Show staff consists of eight highly qualified and enthusiastic keepers. On any given day, only four to five are on duty to plan, prepare, and perform in the show. Given the demanding nature of show business and the extensive duties of a zookeeper, this is no small feat. Each keeper plays an integral role, and in the quest to put on a perfect show, it’s not uncommon for

them to wish they could be two places at once. “The stage has a lot of ins and outs,” says Guenther, “so not having the right number of people can slow the show down. There is more going on than most people realize.”

s a result, the keepers are cons-tantly learning. Today, Keeper Kyle Keas is handling one of the show’s newest members for the first time. Azuri, a bateleur eagle, is not yet ready to perform behaviors in front of an audience, so his current role consists of

perching on the heavily-gloved arm of a keeper and taking a look around at his adoring fans. Even at a standstill, the bird is impressive. Native to sub-Saharan Africa, the bateleur eagle is one of the most colorful birds of prey.

Keas’ focus is visible; he knows that Azuri’s sharp beak and talons could inflict major damage if handled incor- rectly. Guenther calmly instructs, giv- ing handling tips and safety warnings. Once Keas is comfortable, he returns

Azuri to his enclosure. Guenther breaks into a grin. “Every

day someone learns something new. It’s great. I love it.”

Of course, as with all new shows, there is room for improvement. Guenther envisions incorporating as many as 20 additional birds to the show, including a flock of parrots that was featured in the old World of Birds Show. “When we look out at the audience while a flock of parrots circles over them, you can see they’re enjoying their time,” said Guenther.

As today’s host, Melissa Loebl, prepares to walk onstage, she recites her lines under her breath. More birds have been added to the show, and with new birds comes new dialogue. The show’s script is being continually revised to incorporate more birds and behaviors, and each host must adapt to these changes. Once they have rounded out a full cast of birds, the staff plans to solidify a running theme for the show—a cohesive storyline designed to impress and inspire Zoo guests with messages of awareness and conservation.

G The World of Birds Show human cast includes Kevin Copley, Caitlyn Coffey, Shawna Joplin, Jon Guenther, Jennifer Kuypers, Melissa Loebl, and Kyle Keas.

A

JAMIE PHAM

7

F H The completely redesigned Angela Collier World of Birds Show Theater affords exciting new demonstrations of bird behaviors.

F Moluccan cockatoos are charismatic and playful.

F Eurasian eagle owls are among the world’s largest owl species.

G A Harris’s hawk is one of many spectacular raptors in the show.

But today, the World of Birds Show is content to impress audiences with its new theater and exciting performances. Music swells, keepers take their positions, and the stands fill with visitors. This is the culmination of the morning’s

efforts; this is the chance to inspire. The show begins with a flourish as Chinook, an American bald eagle, flies majestically overhead. Antsy children sit stiller as beautiful birds glide just out of reach. The audience gasps and applauds as KC, an Andean condor, swoops down from the hillside with her breathtaking 10-foot wingspan.

Twenty minutes later, another World of Birds Show has come to an end. At the end of the day, the show is about the guests. Says Guenther, “I honestly think that if they come to the Zoo and don’t come to the bird show, they’re missing one of the best things the L.A. Zoo has to offer.” j

JAMIE PHAM

JAM

IE P

HA

M

TAD M

OTOYA

MA

TAD

MO

TOYA

MA

TAD

MO

TOYA

MA

8 ZOO VIEW • FALL

B y C h a n t e l M i k i s k a

8

1

rom our tiniest frog (1 gram) to our Asian bull elephant (12,000 pounds), we try to

treat each animal individually,” says Dr. Cindy Stadler, acting Chief

Veterinarian for the Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens. The Zoo’s approach to preventive medicine is comprehensive. One commonality of care received by all the animals, big and small, is the focus on prevention. Preventive health care plays an important role in maintaining a healthy Zoo population, by discovering disease early on, or before it becomes a big problem.

When’s the last time you had a check-up at your doctor’s office? If you’re like most people, the animals at the Zoo probably receive more regular examinations than you do. Sick animals aren’t the only ones that see the vet—all of the Zoo’s animals undergo preventive health exams, also known as routine exams. Most animals are examined by one veterinarian and a veterinary techni- cian (as well as any veterinary students who are there to observe).

Let’s say the Zoo has a female kangaroo due for her annual exam. The first decision to be made is where to conduct the exam—at the animal’s exhibit or at the Zoo’s state-of-the-art Gottlieb Animal Health and Con-

servation Center, located just beyond visitor parameters. In the case of a very large animal, such as an elephant, practicality dictates that the veterinarians go to the patient. But that is the exception to the rule, Stadler explains, “If we can safely transport them to the Health Center, we usually bring them here.” Although most everything at the Health Center is portable, it’s best if the veterinarians have quick access to all of their equipment in case an emergency arises.

Next our kangaroo patient must be im-mobilized, both for her safety and the safety of the veterinary staff. If she has not been trained to receive hand injections, she’ll be darted with an anesthetic agent. As the anesthesia takes effect, the veterinary staff keeps a close eye on her vital signs. Devices are attached to monitor the kangaroo’s TPR (temperature, pulse, and respiration) and oxygen saturation to make sure there are no complications. Once stable, the kangaroo is ready to be transported from the exhibit to the Health Center.

A typical physical examination takes 30 to 60 minutes, a testament to the efficiency of the veterinary staff. The vet starts by performing a full physical examination—checking the animal’s nose, mouth, lymph nodes, teeth, eyes, and so on—working from

ZOO VIEW • FALL

CO

URT

ESY

OF

GO

TTLI

EB A

NIM

AL

HEA

LTH

& C

ON

SERV

ATIO

N C

ENTE

R

JAM

IE P

HA

M

When it comes to the Zoo’s

animal residents, an ounce of

prevention is worth not just the

proverbial “pound” of cure, but

up to several tons!

G Every animal at the Zoo, including this female Western gray kangaroo, receives routine preventive exams.

G A full physical includes checking each individual from head to toe.

The

F“

TENDING

99

the head down to the tip of the tail. The exam includes chest auscultations (listening to the chest with a stethoscope to make sure the heart and lungs sound normal) and abdominal palpations (feeling the abdomen for unusual masses or enlarged organs). Although veterinarians are looking for signs of disease, sometimes happy discoveries are made, such as pregnancy.

The next step involves taking blood samples and administering any necessary vac- cines. The routine blood test is called a CBC (complete blood count) and chemistry. The CBC will reveal evidence of infection, anemia, or other abnormalities. The chemistry sheds light on the functioning of the organs, such as the liver and kidneys. If needed, the vet will run species-specific tests—testing the Zoo’s big cats for feline leukemia or feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), to cite impor- tant examples. Vaccines are also species specific and given if the potential benefits outweigh the risk of complications. The kang- aroo would be administered a tetanus and rabies vaccine.

The veterinarian may choose to do more comprehensive blood tests on an older animal. Zoo animals are living longer than ever, and preventive medicine for the geria- tric crowd is critical, considering their health

needs are different from the spry young ones. Older animals are at greater risk for certain conditions, such as heart disease, kidney disease, liver disease, arthritis, and cancer. While the screening process is practically the same, the veterinary doctors pay close attention to any issues that may arise from advanced age.

Next the vet may take baseline radio-graphs of our kangaroo, especially if she has not had any recent ones. The rapid advance-ments being made in human health care often make headlines, but zoo medicine has also drastically evolved in the digital age. There are risks associated with anesthesia for humans and animals alike, so doctors try to minimize the time spent under anes-thesia. Digital radiographs take 20 to 30 seconds to develop, compared with three to five minutes for the old-school film X-rays. Vets can now take more diagnostic tests in less time. This leads to a clearer picture of an animal’s health status and a better chance at discovering disease before it’s in its later stages and becomes difficult to treat.

Other advanced digital diagnostics, such as electrocardiograms, endoscopies, or ultra-sounds may be performed if indicated.

Veterinarians aren’t the only ones who can spot signs of disease; animal keepers

are the first line of defense. They work closely with the animals and know each individual’s behavior patterns. Zoo animals may instinctually shield signs of disease like they would in the wild in order to survive. Keepers often pick up on subtle shifts in behavior that may signal a medical problem. An animal that is not eating, spitting out food, or drooling may have a dental issue. Kangaroos in particular are susceptible to a disease called “lumpy jaw,” which is a swel ling on the jaw caused by a tooth root abscess or infection of the bone. With preventive dentistry exams, our kangaroos remain lumpy jaw free.

Another sign of the evolution of preven-

ZOO VIEW • FALL

JAM

IE P

HA

M

JAM

IE P

HA

M

G Dr. Stephen Klause peers into a Sumatran tiger’s ear while the animal is under anesthesia.

G An enlarged liver is apparent in radiographs taken during the Sumatran tiger’s physical examination.

10

tive health care at the Zoo is the modern emphasis on training. Many species are taught to perform certain behaviors in order to facilitate health care. (The training itself also provides cognitive stimulation to the animals, and serves as a form of environmental enrichment.) Take the example of Kaloa, a 13-year-old male jaguar. Several times a week, keeper Danila Cremona leads the big cat through a series of training exercises designed to make his veterinary care easier—on both Kaloa and the veterinary staff. Kaloa’s paw pads become dry and cracked if they are not oiled. Rather than immobilizing him to perform this task, Cremona signals Kaloa to place his paws against the barriers of his holding area and allow her to apply the oil.

Kaloa has mastered several other valu able behaviors, such as getting on a scale, touching targets, and showing his belly. When the jaguar performs the correct behavior, Cremona uses a whistle as a “bridge,” or an immediate signal to Kaloa that he’s doing what he’s supposed to do.

Just like house pets, many zoo animals are leery of the vet. There’s not much our vets can do for a stubborn tortoise who refuses to come out of his shell. Cremona conditions Kaloa to accept the presence of a vet by bringing a kit of medical supplies to his training sessions. She mimics actions a vet would perform, such as tugging on his tail to administer anesthesia. She gently touches Kaloa’s fur with a needle, not enough to cause pain or break the skin, but just enough that the jaguar doesn’t develop a fear of needles. Such a fear would add unneeded stress to the administration of vaccines, medications, or sedatives.

“Training is about building trust,” Cremona explains. Lacking this trust, the animal won’t be willing to learn the behaviors that can make preventive health care more seamless.

At the end of his session, Kaloa is rewarded for good behavior with tasty raw meat; Zoo staff use only positive reinforcement as a reward and motivation to perform the behaviors.

peaking of meat, nutrition is a big component to disease prevention. Each animal’s diet has been carefully prescribed, based

on research into the species’ diet in the wild and an individual’s

life stage and medical needs. All animals, including humans, need protein, carbohy- drates, fats, fiber, minerals, and vitamins to stay healthy. The difference lies in deter-mining which foods the animals should consume in order to receive the proper balance of those nutrients and the ratio of these nutrients as the animals age. For example, apes and monkeys, just like humans, are susceptible to diabetes. As a result, the Zoo’s primates are prescribed diets that are low on sugary fruits and higher in leafy green vegetables.

Once a diet has been approved by the Zoo’s animal curators, keepers (sometimes assisted by volunteers) prepare and present the food. Presentation is just as important as the food itself—searching for food is a natural behavior of many species, and hiding or scattering food keeps these foraging animals both mentally and physically healthy.

An aspect of Zoo health care unfamiliar to

most people is necropsy, or animal autopsy. Every animal that dies at the Zoo undergoes a necropsy regardless of its age at death. It’s important to find out why animals die, so that, if necessary, we can take steps to prevent the spread of disease. This policy may extend to local wildlife, such as squirrels or raccoons, which are not part of the Zoo’s collection. This practice proved life-saving three years ago, when necropsies performed on some of these local residents revealed they’d suffered from canine distemper. Canine distemper can affect many species, so the veterinarians had to ensure that every Zoo animal at risk for the disease was up to date on their vaccinations.

Information sharing is vital to preventing the occurrence or stopping the spread of disease. The veterinary staff is required to notify the Department of Public Health

G It takes teamwork to coax an infant giraffe onto a scale to be weighed.

H E Veterinarians weigh the risk of complications from anesthesia against the benefits of performing preventive health exams. A siamang (left) undergoes a health check. A Komodo dragon (right) receives an eye examination.

BREN

DA

POSA

DA

JAM

IE P

HA

M

CO

URT

ESY

OF

GO

TTLI

EB H

EALT

H C

ENTE

R

S TAd

MO

TOYA

MA

1111

JAM

IE P

HA

M

(DPH) of specific disease outbreaks. In this particular case, the DPH confirmed an out-break of distemper in the Griffith Park area, thus the Zoo provided additional disease surveillance for the local county agency.

Moreover, many necropsy results are sent to a central lab so that researchers have a larger pool of data to work from when determining how to better manage and care for different species.

Last but not least—actually the first step in preventive health care—is quarantine. When a new animal arrives at the Zoo, it goes through a quarantine period, which is a minimum of 30 days. Reptiles, which take longer to manifest disease, are quarantined for at least 90 days. If she transferred here from another zoo, our kangaroo patient would have been quarantined for 30 days

upon arrival. If the animal is diagnosed with a contagious disease while in quarantine, its stay would be extended throughout the duration of its treatment.

All staff working in the Zoo’s quarantine facility must suit up by wearing clothes and boots only worn in the quarantine area. Two of the rooms—designed for small reptiles, amphibians, or birds—are temperature and humidity controlled depending on the spe cies’ individual needs. The primate quarantine wing is one of few in the United States that meets the rigid standards of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Preventive health care, extending far beyond the examination room, is the foun dation of zoo medicine. Maintaining a thriving zoo population ensures the well-

being of our animals, as well as the pres-ervation of dwindling species. With more than 1,100 animals at the Zoo, conducting routine checkups is a tremendous and never-ending task, and one that plays a crucial role in keeping the animals healthy.

When the vet staff has finished examining our kangaroo patient, she will be transported back to her exhibit and closely monitored while the anesthesia is reversed or wears off. Once she’s back on her oversized feet, keepers will keep an eye on her. The veterinarians, meanwhile, are already on their way to their next scheduled examination. j

F Animal keeper Dani Cremona signals male jaguar Kaloa to stand up against the mesh so she can inspect his paws.

FF California condors are vaccinated against West Nile virus.

G Ultrasound of an emperor tamarin’s heart: primates are susceptible to cardiac disease, so it is important to check their hearts regularly.

G Some check-ups involve veterinarians, veterinary technicians, and observing externs.

CO

URT

ESY

OF

GO

TTLI

EB H

EALT

H C

ENTE

R

TAd

MO

TOYA

MA

JAM

IE P

HA

M

ZOO VIEW • FALL

12 ZOO VIEW • FALL

2.0

ZOO VIEW • FALL12

By the Numbers Establishing policies that protect habitat and endangered species is a numbers game. Making a case depends on data—the more data the better—and over the past 50 years, advances in digital recording technology have dramatically changed the quantity and quality of information that biologists are able to gather, painting a more detailed picture of the species they are striving to save.

Kodak engineer Steven Sasson completed the first prototype digital camera in 1975. It weighed eight pounds and used a 100x100-pixel sensor to create black-and-white images. Today, digital cameras are standard equipment on phones, and they are tiny enough to attach to insects and surgical implements.

Camera traps—small, durable digital cam- eras triggered by motion or heat sensors—have revolutionized the collection of field data. The cameras record a wealth of data quickly and inexpensively. Numerous species from snow leopards in the Himalayas to Komodo dragons in Indonesia, to jaguars in Nicaragua and mountain lions in the Santa Monica Mountains, are benefiting from technology that makes it easier for scientists to understand the details of their lives. Although trapping animals still provides specific physiological information about individuals, camera traps yield a wider range of information about how they live.

Strategic placement of the traps to answer specific questions is important. An urban setting versus forest loca-tion can indicate which species are able to adapt to human habi- tat. Security cameras intended to identify car thieves in neighbor-hoods adjacent to Griffith Park captured footage of the mountain lion now known as P-22 (short for Puma 22; the four-year-old male

was the twenty-second mountain lion captured and radio-collared by National Park Service biologists in this region) strolling through a Hollywood Hills neighborhood in the pre-dawn hours.

Scientists can learn which animals are using trails and which ones are not—useful informa-tion in making cases for wildlife corridors and tunnels. Camera trap images revealed that bobcats tend to use tunnels and shadowy passages, while deer and coyotes disregard traffic and will cross bridges. Design elements of wildlife overpasses can be examined—for instance, whether animals favor natural sub-strate, or if naturalistic habitat on either side encourages the use of overpasses or tunnels. The effect of traffic patterns on wildlife move ments can be determined by cross-referencing these data. The ability to predict where potential conflict between wildlife and humans is likely to erupt makes for better environmental policy and urban planning.

Further afield, cameras purchased by the L.A. Zoo for the Komodo Survival Program have transformed fieldwork in the giant lizards’ home range. The five small Indonesian islands to which the dragons are endemic are paradoxically hot and humid yet limited in fresh water—and far beyond the range of most wireless/cell technology. Whereas trapping the animals to collect data can be quite challenging and potentially dangerous, using

camera traps allows biologists to gather better information in a non-invasive (and cost-effective) manner. A $5,000 conservation grant provided 50 cameras plus other necessities such as boat fuel and field assistants, who helped set up the cameras and the bait boxes used to attract the dragons. Between the bounty of photos and

n the Star Trek universe, scientists orbiting a planet can conduct a computer scan that almost instantly determines its structure, composition, and resident life forms. In our universe, technology is not yet that sophisticated, but biologists and researchers are finding applications for new technology that are taking conservation work light years into the future.

Conservationb y S a n d y M a S u o

IAN

REC

CH

IO

H Digital data helps biologists target their analog efforts on the ground.

I

13ZOO VIEW • FALLZOO VIEW • FALL 13

G E Gus and Mabel, the Zoo’s first southern black rhinos, arrived from Zimbabwe in 1982 as part of an international rescue operation.

G 1) Capturing dragons is much simpler with camera traps. 2) Boxes baited with meat draw dragons (and other animals) into the camera’s field of vision. 3) Small, sturdy cameras go places that large, cumbersome traps cannot. 4) Camera traps are cost effective and easy to maintain. 5) Camera traps revealed Griffith Park as an urban oasis for local wildlife. 6) Digital camera trap photos of a snow leopard family in the wild.

13

1

2

5 6

3 4IAN RECCHIO IAN RECCHIO IAN RECCHIO

PHOTO COURTESY MIGUEL ORdEñANA PHOTO COURTESY SNOw LEOPARd TRUST/www.SNOwLEOPARd.ORG/SNOw LEOPARd FOUNdATION KYRGYzSTAN

AN

GEL

A W

OO

DSI

DE

H GSM transmitters mounted on California condor wings are solar powered.

scat samples, biologists have accumulated a wealth of information about the population.

But Komodos are big fish in a small pond. Researchers studying jaguars in Nicaragua face the opposite scenario. The dense tropical jungle terrain in Central America can be as difficult to negotiate as the rugged Komodo islands, but the cats are secretive, few, and far between. The situation requires a different tool.

Getting in TuneWildlife biologists have used radio tracking since the 1960s. The oldest and most reliable method relies on Very High Frequency (VHF) radio signal transmissions. Animals are fitted with collars that transmit a signal that is picked up by ground-based receivers. It is dependable, familiar, and cost-effective. A disadvantage to this method is that it is labor intensive because the triangulation necessary to pinpoint an animal’s location involves navigating through habitat, which can be challenging. Also, because radio-tracking is ground-based, it is more limited and less accurate than GPS.

Since the 1980s, satellite telemetry has also been an option. The Argos satellites are in polar orbits of the Earth and provide near-global coverage reading Ultra High Frequency (UHF) radio signals. Although Argos telemetry covers a very wide range, it is more expensive than VHF ground tracking and is less specific. It is, however still the best option for far-ranging species such as marine mammals, sharks, and sea birds.

Global Positioning Satellite (GPS) techno- logy is the most recent tracking alternative. The same network of satellites that helps us

navigate through traffic enables biologists to gather detailed information about the movement of animals. GPS collars record location data for the animals, which the researcher can download manually or remotely. Although it is more expensive to collect data this way (a conventional VHF radio collar costs about one-tenth the price of a GPS collar), it also provides more detailed information over a small area than Argos telemetry and is considerably less labor intensive than VHF. Additionally, it enables researchers to track animals from a remote location, thus lowering the likelihood of observational interference with natural behavior.

Researchers sometimes use a combination of tracking technologies to strike a balance between cost efficiency, data accuracy, and man-hours. Scientists researchers studying P-22, Griffith Park’s resident mountain lion, use both GPS and VHF methods to record his movements, which then help determine the best locations to set camera traps and search for physical evidence.

Originally, radio tracking California condors was done using VHF transmitters when the birds were in the immediate vicinity of researchers and Argos telemetry when they ventured out of range. GPS tracking only became possible once the transmitters became small enough to fit on a bird, 10 to 15 years ago, and they have become even smaller in the past decade. Today’s tail-mount transmitter is the size of one AA battery and lasts two years. It provides very detailed information about condors but is prohibitively expensive. The newest upgrade in condor observations

incorporates cell phone transmission techno- logy. By using cell phone networks (Global System for Mobile Communication, or GSM) to transmit data, it is possible to gather minute-by-minute data on condor movements. Not only does GSM increase the volume of data that can be collected, it does it much more cost effectively (roughly $30/month versus $100/month for Argos). This method is effective only in areas with strong coverage. In Southern California, where cell coverage is extensive, the Argos transmitters are being phased out. Most condors now have a GSM on one wing and one or two tail-mount radio/VHF transmitters.

This data helps scientists understand not

E Powered by a solar cell and set on a timer, a digital recorder tapes the nightly calls of bats at the Zoo.

E Big brown bats are one of many species found in Southern California.

COURTESY US FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE

15ZOO VIEW • FALL

only the dimensions of individual condor territories, but also how the birds use it. This information is vital when debates over land use arise. For instance, detailed 3-D condor range maps have proven invaluable in negotiations over the placement of wind farms.

A collaboration between USGS, the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the San Diego Supercomputer Center at the University of California San Diego produced 3-D animated maps that showed California condors’ individual ranges, how breeding pairs shared territory, where they spent most of their time and at what elevation. To accomplish this, the scientists pinpointed the birds’ locations every hour from 5 a.m. to 8 p.m. (their period of peak activity) starting in 2007. Similar mapping has been completed for dugongs (sea cows) and giant pandas.

Can You Hear Me Now?Zoologist Donald Griffin discovered echo lo- cation in bats in 1944 by slowing down recordings of the sounds bats make to levels audible by the human ear. Digital recording devices have dramatically enhanced our ability to monitor these nocturnal creatures (and others) in the same way that camera

traps have changed the way we study terres-trial animals.

In January 2012, as part of the Griffith Park Natural History Survey, an echolocation detector was installed on Zoo grounds. Within two months, several bat species were confirmed. Most calls were those of Mexican free-tailed bats, but the recorder also picked up calls from hoary, Yuma myotis, canyon, and Western mastiff bats. The discovery of the Western mastiff is particularly significant because there were concerns that this species had been extirpated from parts of the Los Angeles Basin. Last year a second bat detector was added near the black-necked swan exhibit.

The devices appear to be boxes on posts, outfitted with solar cells. Inside the box is a digital recorder that is set on a timer to go on at dusk and off at dawn. The recorder stores data on an external hard drive that can be plugged into a computer via a USB port. The data is downloaded every two weeks or so. Specialized software processes the data in two steps. The first filters out random sounds. Next, bat calls are identified based on a sound library that is the accumulation of many years of documented bat IDs. Each bat species has its own distinct repertoire of vocalizations, representing many dif -fer ent behaviors: communication, naviga-tion, locating food.

G A tiny transmitter on a mountain yellow-legged frog tells biologists how far ranging the amphibians are.

GG Bird watchers are among the most enthusiastic citizen scientists.

G These two real-time maps show two different species’ relationships with humans. Bright spots (left) illustrate how chimney swifts thrive in urban centers. Dark spots over the same areas (right) show that indigo buntings do not.

G Andatu (shown with mother Ratu) was born at the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary in Indonesia’s Way Kambas National

MA

RLO

WE

ROBE

RTSO

N-B

ILLE

TJA

MIE

PH

AM

TOM

NO

RD

16 ZOO VIEW • FALL

In order to verify the presence of a particular bat species, at least three distinct calls, or pulses, have to be identified in a particular data batch. Then an additional, separate ID must be made. So, for example, California myotis was recently read in three instances on one data file, but researchers are waiting for an independent reading to confirm its presence in the Zoo.

As with digital camera technology, the record-ing devices that detect bats are becoming more widely available and less expensive. Bat detectors now cost about $500; the apps to help identify the calls are free.

There’s an App for Thatdvances in technology are not only making data collection more efficient for experts, but are also expanding the role of citizen scientists. Anyone with a cell phone can record animal sightings, a plethora of apps

are making it easier to collate and interpret that data, and the science establish-ment is recognizing more and more the value of public participation in research.

For 16 years, the Great Backyard Bird Count (GBBC), sponsored by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Audubon, has been encour-aging people to become citizen scientists. Every year, bird watchers across the country (and here at the Los Angeles Zoo) participate in the GBBC. As of last year, the data gathered totaled 140 million observations submitted by 150,000 separate observers. Mobile apps aid bird identification and make it easy to contribute. Through its online database “eBird,” Cornell compiles the data, adjusts for accuracy, and uses the findings to help public and private sector agencies make policy.

In 2012, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF)

received a $5 million grant from Google to work on developing ways to protect wildlife. WWF developed an app called Field Notes that allows field researchers using Google Glass to record a variety of data hands-free using digital imaging, voice recognition software, and GPS. Scientists in Nepal are testing it in their work monitoring threatened populations of Indian rhinos.

The Final FrontierPeople living in cities may worry over the privacy issues that drones and high powered zoom lenses raise, but in remote rain forests, small, maneuverable unmanned aircraft equipped with cutting edge cameras are able to provide the most accurate orangutan census available—or patrol tirelessly for signs of poachers. Greg Asner, a scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., has outfitted a small utility aircraft with an array of sensors—including spectrometers that can read the chemical composition of leaves, laser scanners that provide minutely detailed topographic readings, and cameras equipped with zoom lenses powerful enough to read the leaves on the trees. Computer software can analyze the data and produce interactive maps that can indicate even incremental changes in rainforest habitat or reveal illegal activities such as mining, which produce signature changes in the bio readings of a normal forest.

Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry was an optimist who believed in the human potential for creating a better world, one that places equal value on all life forms, and he believed technology would be integral in realizing that utopia. If we can use it wisely, we may yet reach that goal. j

FGG The Carnegie Airborne Observatory is a small utility aircraft equipped with an array of powerful sensors. An image of rainforest in Peru (left) shows red areas where the largest trees sequester the most carbon.

G The Carnegie Airborne Observatory (above) and an AToMS 3-D image showing the chemical composition of Amazon tree forest.

G At the Zoo, inexpensive digital cameras allow staff to record and monitor nightly activities of nocturnal species such as Panay cloud rats.

AJA

MIE

PH

AM

GREGORY ASNER, CARNEGIE INSTITUTION FOR SCIENCE

17ZOO VIEW • FALL

The Bali mynah is one of the world’s most endangered birds . . .The axolotl is critically endangered . . . Such statements often appear in these pages, but did you know how these classifications are determined?

Celebrating its fiftieth anniversary this year, the International Union for Con-servation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species is the world’s most

comprehensive source of information on the conservation status of animal, fungi, and plant species. The Red List

sets forth the rigorous criteria for cate-gorizing species as endangered, critically endangered, vulnerable, and so on.

In addition to quantifying the status of specific species, the Red List is also used to identify large-scale trends and threats, according to Dr. Simon Stuart, IUCN Species Survival Commission Chair. “When you put together all the data for a country, or all the data for birds, or whatever it may be—you can find out ‘How are birds doing?’ or ‘How are the species in the U.S. or the state of California doing?’

And how has that changed over time?”Beyond its utility in scientific research,

the Red List is also used in conservation planning and policymaking. It helps donors, governments, and environmental organiza-tions decide how to allocate funds.

Nearly 74,000 species have been assessed to date. Fifty years ago, that number was just a few hundred. While the Red List was helpful in identifying threatened species as early as 1964, it wasn’t looking at the big picture. “They weren’t getting a measure of the health of the planet,” explains Stuart. “They could say, ‘These species are threatened,’ but they couldn’t say, ‘Twenty-five percent

of all mammals are at risk of extinction.’”The IUCN’s goal is to reach 160,000 species

in the next six years—more than double the current total. Stuart says, “That is the number we calculated could be accurately representative of all life on Earth.”

As zoos worldwide have increasingly taken conservation into their mandate, their reliance on the Red List as a tool for research and priority-setting has grown. Zoos are also increasingly contributing to the data pool, Stuart points out: “A growing proportion of the scientists involved with the Red List are employed by zoos.”

A global network of approximately 8,000 scientists update the Red List. The experts amass information about each species’ dis- tri bution, population trends, habitat, threats, and conservation actions. Based on the pooled data, they calculate its category (on a scale from “critically endangered” through “least concern”). A “data deficient” cate-gory denotes species for which there is not enough known to make a determination. Curious where your favorite animals fall on the scale? You can search the database online at www.iucnredlist.org. j

G The Bali mynah is one of nearly 74,000 species assessed on the Red List of Threatened Species.

H Although common in the pet trade, the axolotl is critically endangered in the wild.

17ZOO VIEW • FALL

b y b R E n d a P o S a d a

A HAlf CenturyAssessing species

ofJA

MIE

PH

AM

TAD

MO

TOYA

MA

18 ZOO VIEW • FALL

v

Jeans for Giraffes

Docents are GolDen

By Olivia Hummer

By Kirin Daugharty

18 ZOO VIEW • FALL

owering 17 feet high and sporting a rather distinct spotted coat, giraffes are hard to miss. In fact, each giraffe’s markings are unique and can be used as a form of identification, not unlike human fingerprints! Despite such high visibility, giraffes may be being taken for granted. Over the last 15 years, giraffe popu-

lations in Africa have declined by more than 40 percent. It is estimated that only 80,000 individuals remain in the wild.

Although the giraffe’s conservation status is categorized as “least concern” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, two subspecies (Rothschild’s and West African) are endangered. Giraffe populations in northern Africa, in particular, are threatened by increasing habitat degradation and poaching. “Their number is less than 200, and they are in an area that’s hard to protect and preserve,” said Animal Keeper Mike Bona. Biologists plan to implement programs to more accurately census the population, distribution, and status of giraffes, but the need for conservation is clear.

The L.A. Zoo is currently home to five Masai giraffes, the largest of the giraffe subspecies. On World Giraffe Day (June 21), the Los Angeles chapter of the American Association of Zoo Keepers kicked off a “Jeans for Giraffes” drive at the Zoo. Visitors who dropped off used denim at the Zoo that day received a discount on admission. Bona collected more than 200 pounds of denim that day alone—and the Zoo continued to accept donations throughout the summer, eventually topping 400 pounds.

When combined with jeans collected at other participating facilities (in- c luding the San Francisco, Oakland, Santa Barbara, and Happy Hollow zoos), the grand total topped 3,200 pounds! The do- nated dungarees will be sold to a textile recycling company that pulps the fabric and converts it into housing insulation. The proceeds will help fund giraffe conservation and research, with the added benefit of reducing waste. The average person in the United States discards 68 pounds of clothing per year according to a study commissioned by Levi Strauss and Co., with 23.8 billion pounds ending up in landfills annually. To learn more, visit www.jeansforgiraffes.org.

T

CH

RISS

Y B

ON

A

he Los Angeles Zoo will be celebrating its golden anniversary in 2016, but that milestone is already here for the Zoo’s docent program, which launched in 1964 with the goal of recruiting and training “zoo guides” to introduce guests to the new Los Angeles Zoo.

Fifteen women graduated from the first 12-week training course. By 1966, these volunteer educators were known as docents rather than guides. The new title better described their role (docent derives from the Latin for “to teach”).

The docent program expanded over the decades to include outreach programs, specialized tours (such as one focusing on endangered species), mini-courses, Animals & You, and adult workshops. The docent-run ZooMobile program was established in the early 1970s, when the gasoline crisis made it impossible for many school groups to travel to the Zoo. Then-docent chair Marion Blair said, “If they can’t come to us, we’ll go to them.”

Former GLAZA President Kaye Jamison said at the time that the goal of the docent program was “the development of the highest educational values and corresponding programs for both the community and for scientific study.” In 1975 the training (which had grown into a 23-week course) became accredited through UCLA Extension, Department of Biology, for eight credits.

As the docent program evolved, so too did the uniform. The first zoo guides wore a modest forest green jacket and belted skirt with baby blue blouse. (Keep in mind, male docents were not admitted

to the program until the late 1970s.). After drifting through some eclectic fashions, the khaki and white uniform the docents sport today was adopted.

The standards for docents are high, with a minimum grade of 80 percent required to graduate, willingness to dive in when or where ever needed, adaptability to weather fluctuations, and ability to give many types of tours. The docents are knowledgeable and friendly—and usually cannot wait to tell you about the amazing tour they just led. Their enthusiasm is contagious, so if you find yourself in the volunteer office, beware—you might just find yourself signing up for the next class!

To learn more, visit www.lazoo.org/support/volunteer.

T

JAM

IE P

HA

M

19ZOO VIEW • FALL

v

Zoo liGhts: a new l.a. traDition

rainforest at Your finGertips

ant to layer another interactive element to your Zoo experience? The Rainforest of the Americas mobile app allows you to do just that. The L.A. Zoo’s first-ever iPhone app allows users to delve deeper into the wonders of the rainforest as they stroll through the exhibit.

The app’s location-based iBeacon technology sends a vibrating pulse to your phone as you approach each Rainforest of the Americas enclosure, unlocking fun facts about its features and inhabitants. Did you know that the harpy eagle is an apex predator? Its huge talons are about the same size as a bear’s claws. How do the exhibit’s giant lily pad replicas stack up to the real thing? A tap of the app reveals that, in a South American rainforest, the tallest pro basketball player could lie down on a single lily pad leaf. Audio clips of select animals’ vocalizations are also available, so if you catch the howler monkeys in a quiet moment, you can listen to a recording of their characteristic calls.

The secrets held within the Rainforest of the Americas app don’t just apply to the animals on exhibit. Facts about the dif-ferent zones of the rainforest, conservation projects supported by the Los Angeles Zoo, and the plant life surrounding the enclosures are also available at the touch of a button. And if you think you took a wrong turn, simply swipe the touchscreen to access a Rainforest of the Americas map—or a map of the entire Zoo—outfitted with GPS capabilities.

The app offers “a way to engage people that’s different from signage,” says Kait Hilliard, GLAZA’s Vice President of Marketing and Communications. “Not everybody stops and reads the signs, and this way they can take the information home with them.”

Currently only available for Apple platforms, the free app is not only handy on Zoo grounds but can also serve as an educational resource after your visit—and a reminder to return. Download it at the Apple App Store or visit www.lazoo.org/connect/rota-app/ for more information.

By Riley Davis

W

By Erica M. Leduc

19ZOO VIEW • FALL

JAM

IE P

HA

M

spectacular light show that will dazzle and delight visitors—while offering a tip of the hat to a bygone L.A. tradition—is coming to the Zoo this holiday season.

Perfect for a family outing, a date night, or a meet-up with friends, Zoo Lights will transform the Zoo with glamour and glitz

and a variety of dynamic displays. This nighttime ticketed event will allow guests to experience the Zoo like never before. And while the focus is on light displays rather than live animals, our annual winter guests—reindeer Velvet, Belle, Noel, and Jingle—will be on display during both daytime and evening hours.

Rather than featuring a single main attraction, Zoo Lights will have several focal points throughout the Zoo. Highlights include elegant animal motif snowflakes at the main entrance, light tunnels, an illuminated 3-D rhinoceros sculpture, and an ice throne for good old Saint Nick. Whimsical characters incorporated into the event storyline include a troop of monkey electricians, who’ll swing through the entry plaza as they guide an illumi-nated power line toward a giant electrical outlet. There’s much more in store, but we’ve been sworn to secrecy for now.

To produce Zoo Lights, the Zoo has partnered with designer Gregg Lacy and Bionic League—a live event design company known for its work with Daft Punk, Deadmau5, and Kanye West, as well as stadiums, arenas, and clubs around the globe. “Theirs is a vision that is all at once ‘holi-day,’ ‘Hollywood,’ and ‘high art’—and very much about the animals at the Los Angeles Zoo that inspire all of us,” says Genie Vasels, GLAZA’s Vice

President, Institutional Advancement.Some of the displays from Griffith Park’s Festival of Lights are slated for

inclusion in Zoo Lights, a nostalgic nod to the beloved local tradition that ended a 14-year run in 2009. While many Angelenos miss the old Festival of Lights, we hope that Zoo Lights will become a new holiday tradition. The techno-wizardry Bionic League, combined with the unique and magical setting of the Los Angeles Zoo, will surely result in a must-see annual event.

Zoo Lights takes place nightly (6 p.m. to 10 p.m.) from November 28, 2014, through January 4, 2015 (except December 24 and 25). For more information or to purchase tickets, visit www.lazoo.org/zoolights.

A

TAD

MO

TOYA

MA

20 ZOO VIEW • FALL

PePsi and the L.a. Zoo: A T r u e P a r t n e r s h i p

isitors to the Los Angeles Zoo have long enjoyed Pepsi beverages available at our restaurants and treat stands throughout the grounds. But in addition to offering a wide selection of quality beverages to thirsty zoo-goers, Pepsi is a generous supporter of the Zoo and its mission in the community.

For nearly 30 years, Pepsi has been a generous sponsor of the L.A. Zoo and has contributed financial support, marketing and advertising resources, and in-kind products in order to help the Zoo reach the broadest possible audience and provide an excellent guest experience onsite. Pepsi recently reaffirmed its commitment to the L.A. Zoo—and to the thousands of families who attend each month—by renewing its sponsorship support for the coming decade. “Pepsi and its dedicated team have been with us every step of the way as we made countless improvements to our exhibits and visitor amenities over the last ten years,” says Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association President Connie Morgan. “It’s incredibly gratifying to know that Pepsi will continue its gener-ous support and involvement for the next ten years,” she adds.

A selection of more than 20 types of Pepsi beverages are available at the Zoo, including soft drinks, juices, teas, and Aquafina water, so there’s something for everyone to enjoy during their day at the Zoo. “Not a day goes by without Pepsi making a difference to our visitors and to the Zoo,” says Morgan, adding, “They are one of the most generous cor-

porate partners in our history, and we look forward to extending this fruitful relationship well into the future.”

Hive: Lighting the WayThe Zoo recently began a partnership with locally based Hive Lighting to provide the Zoo with a significant amount of energy-efficient lighting equipment rentals and services. The partnership was launched in style at the VIP opening event for Rainforest of the Ameri-cas. Hive Lighting’s participation at the event helped showcase the Zoo’s new exhibit, but also highlighted the conservation message that is at the heart of the Rainforest of the Americas.

Jonathan Miller, Chief Product Officer for Hive Lighting, proposed an effective solution utilizing their patented plasma fixtures. “Our lamps provide exceptional output and use up

to 90 percent less energy than many conventional fixtures,” says Miller, “so it was a perfect match for achieving a beauti-fully lit event for the opening of the Rainforest of the Americas and at the same time offering a sustainability-minded solu-tion.” As part of its donation, Hive Lighting’s fixtures have already been used at numerous special events at the Zoo, including Roaring Nights and Brew at the Zoo.

GLAZA is grateful to all of our corporate sponsors, whose contributions help us support the Zoo’s mission. To learn about sponsorship opportunities, please visit www.lazoo.org/support/sponsorships or phone 323/644-4705.

V

S p o n s o r S p o t l i g h t

ZOO VIEW • FALL20

JAM

IE P

HA

M

JAM

IE P

HA

M

BRIA

N L

EvIT

z

DZ o o D o n o r P r o f i l e

To learn how you can support the Zoo’s mission, please visit www.lazoo.org/support or call the Development Division at 323/644-4767.

Bird SHow BenefACtorSielding a pair of over-

sized scissors, Basil Collier cuts through the

ribbon at the grand opening of the Angela Collier World of Birds Theater, looking proud as a peacock. “It is very beautiful and will enhance the memory of Angela,” he says, surveying the brand new stage and its sur-roundings. Collier’s daughter Angela, for whom the theater is named, died in 1997 at the age of 36.The foundation she had established to support animal welfare lives on today, managed by a board of directors and helmed by Mohammad Virani, foundation president. “Angela once said to me, ‘People can

speak up for themselves, but animals cannot,’” Virani says. The Angela Collier Founda-tion supports numerous animal-related organizations and causes in California, including a previ-ous gift to the Zoo to support construction of Campo Gorilla Reserve. In 2011, with the old Bird Show façade in a serious state of disrepair, the founda-tion committed to a major gift that paved the way toward reno-vating the theater. Virani feels the new theater is a fitting tes-tament to Angela’s vision. “I believe she is here in spirit,” he says, “seeing the wonderful things that are being done.” Other donors to the project include long-time Zoo docent Helen Pekny (who provided a generous gift for new caging), Roslyn Schrank, Ann and Robert Ronus, Jack and Barbara Dawson, an anonymous donor, and GLAZA Trustee Brian Diamond,

who do nated the services of his landscaping company, Diamond Landscaping, Inc. “When [GLAZA President] Connie Morgan asked if I would be interested in working on the landscape for the new Bird Show, I jumped at the opportunity,” Diamond relates. After consult-ing with the Bird Show staff to identify their needs and priori-ties, Diamond crafted a land-scaping plan that would lend a tropical feel to the arena, using sustainable, low water use plant-ings that are easy to maintain. Calling the Zoo “one of L.A.’s dia monds in the rough,” Diamond says, “The connection, educa-tion, and piece of mind you get from spending time with animals is amazing—and sometimes life changing. Just knowing that improvements made today will affect so many children and fami- lies for generations to come fills my heart with joy!”

W E The Collier family celebrates the grand opening with Zoo repre-sentatives and Councilmember Tom LaBonge.

H This towering tribute was erected to honor the theater’s major donors.

ZOO VIEW • FALL 21

TAD

MO

TOYA

MA

JAM

IE P

HA

M

![FALL 2019] - Sacramento Zoo](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/61ef9dfc21922a5dcb2b8371/fall-2019-sacramento-zoo.jpg)