Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

-

Upload

formigas-verdes -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

1/213

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

2/213

Yuendumu Everyday

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

3/213

To my mothers Heidi, Kay, Linda, Lucy, Maggie, Ruth and Salwa

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

4/213

Yuendumu EverydayCa Aa Auaa

Yasmine Musharbash

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

5/213

First published in 2008

by Aboriginal Studies Press

Reprinted 2009, 2010

Yasmine Musharbash, 2008

All rights reserved. No part o this book may be reproducedor transmitted in any orm or by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any

inormation storage and retrieval system, without priorpermission in writing rom the publisher. The Australian

Copyright Act 1968(the Act) allows a maximum o one chapteror 10 per cent o this book, whichever is the greater, to be

photocopied by any educational institution or its educationpurposes provided that the educational institution (or body thatadministers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright

Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Aboriginal Studies Press

is the publishing arm o theAustralian Institute o Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Studies.

GPO Box 553, Canberra, ACT 2601Phone: (61 2) 6246 1183

Fax: (61 2) 6261 4288Email: [email protected]

Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au/aboriginal_studies_press

National Library o Australia

Cataloguing-In-Publication data:

Author: Musharbash, Yasmine.

Title: Yuendumu everyday : contemporary lie in a remoteAboriginal settlement / Yasmine Musharbash.

ISBN: 9780855756611 (pbk.)ISBN: 978 0 85575 691 8Notes: Includes index. Bibliography.

Subjects: Aboriginal Australians Northern Territory

Yuendumu. Warlpiri (Australian people) NorthernTerritory Yuendumu. Warlpiri (Australian people)

Social lie and customs. Yuendumu (NT) Social lie andcustoms.

Dewey Number: 305.89915

Printed by Blue Star Print Group, Australia

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are respectully

advised that this publication contains names and images odeceased persons, and culturally sensitive material. AIATSIS

apologises or any distress this may cause.

Cover image: Liam Campbell

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

6/213

Illustrations viAcknowledgments viiNote on spelling and orthography x

1 Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement 12 Camps, houses and ngurra 263 Transorming jilimi 46

4 In the jilimi: mobility 595 In the jilimi: immediacy 776 In the jilimi: intimacy 957 Intimacy, mobility and immediacy during the day 1128 Tamsins antasy 139 Conclusion 150

Appendix: Yuendumu inrastructure 158Glossary 163Notes 167Bibliography 183Index 194

Contents

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

7/213

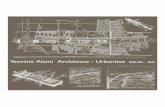

Figures

1. Central Australia xii2. Spatial Camp divisions at Yuendumu 233. Yuendumu settlement 244. The spatial terminology ocamps 295. The spatiality o gendered camps 336. Iconography or ngurra 36

7. Iconography or camp 368. Thejilimi spatial layout 539. Genealogy o Polly, Joy, Celeste and Nora 5810. Nights/people in thejilimi 6311. Genealogy o core residents 6512. Sleeping arrangements, 29 November 1998 8513. Sleeping arrangements, 1 December 1998 87

14. Sleeping arrangements, 3 May7 May 1999 9215. Flour distribution during mortuary rituals 12016. Hithering and thithering 13017. Tamsins genealogy 140

tAbles

1. Average numbers o adults and children sleeping in the 62jilimi

2. Types o residents 643. My positioning in thejilimi 904. Sleeping companions 1025. Sleeping positions 106

illustrAtions

v

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

8/213

I am lucky to be have been taught by three exceptional teachers, whokindled and uelled my passion or anthropology: Lukas Werth (atFreie Universitt Berlin) made me all in love with ideas, the late DawnRyan (at Monash University) made me appreciate that anthropology isabout people, and Nic Peterson (at the Australian National University)made me see the exciting in the real. Their mantra (ideas, people, data)sustained and guided me through my eldwork and the writing o this

book. It led to my ocus on the everyday: the ideas encapsulated in andexpressed through it, the mechanics o it, and the people living it.

My most heartelt thank-yous go out to the people I lived with, whotolerated my presence and incessant questioning with good humour,

who drew me into their lie, let me participate and taught me so much,who made eldwork such an enjoyable experience and through theirriendships turned Yuendumu into a true home or me. Special thanks

go to Kumunjayi Jakamarra Ross, Kumunjayi Napaljarri Ross, Yuurltu,Kumunayi, Gurtley, Kieran, ENR, Keith, Kumunjayi Napangardi,Eugene, Nana, Shane, NO, RO, Ruth Napaljarri Oldeld, Warungka,

Jorna, Lizzie, Serita, Rosie, Jeannie, Jangala, Dadu, Victor, Cecily, Uni,Andrea, Warren, Watson, Sera, Regina, Valery, Kumunjayi NapurrurlaWilson, Kumunjayi Nampijinpa Daniels, and Kumunjayi JapanangkaGranites.

I thank Yuendumu Council and the Central Land Council or

issuing the necessary permits and always being o assistance. Forbeing supportive, generous and helpul in many small and some largeremergencies, I thank Mt Theo Substance Misuse Programme and JaruPirrjirdi, Yuendumu Womens Centre, Warlukurlangu Artists Aboriginal

Association, Warlpiri Media Association, Yuendumu Mining Co., and

ACknowledgments

v

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

9/213

Acknowledgments

v

Yuendumu Clinic. At Yuendumu and Alice Springs I am especiallygrateul to Megan Hoy and Tristan Ray, Charlie and Clancy, SueMorrish and John Boa, Ronnie and Leonnie Reinhardt, David Ratery,

Liam Campbell, the Little Sisters, Frank and Wendy Baarda, MamataLewis, Pam Malden, Andrew Stojanowski (Yakajirri), Ola Geerken,Tara Lackey, Rita Cattoni and Brett Badger, or thousands o cups otea, abulous conversation, encouragement, and once in while a quietplace to stay.

This book grew out o my PhD thesis, and I am deeply grateul or thenancial assistance I received rom the Australian National Universityduring my PhD degree and rom the University o Western Australiaduring my postdoctoral ellowship. At both institutions I ound wonderulriends and colleagues, who in one way or another helped me along

with this book, through critical engagement, passionate debate, helpuladvice, thoughtul insights, most welcome help with the ddly things,and more cups o tea. I would like to especially mention Jon Altman,Sallie Anderson, Marcus Barber, Emily Buckland, Victoria Burbank,Paul Burke, John Carty, Georgia Curran, Richard Davis, Derek Elias,

Sue Fraser, Don Gardner, Katie Glaskin, Chris Gregory, Nick Harney,Melinda Hinkson, Ian Keen, Alex Leonard, David McGregor, AndrewMcWilliam, Erik Meijaard, Francesca Merlan, Howard Morphy, DavidNash, Damon Parker, Michael Pinches, Greg Rawlings, Tim Rowse,

Alan Rumsey, Will Sanders, Dionisio Soares, John Taylor, Bob andMyrna Tonkinson, Allon Uhlmann, Andrew Walker, Jill Woodman andMichael Young.

Extra special thanks go to Debbie McDougall, Kevin Murphy and

Raelene Wilding or their generosity with red ink. More extra specialthanks to Franoise Dussart and Lee Sackett, or their ne comments onmy thesis and their riendship. Heartelt thanks also to the anonymousreviewer who made such insightul comments on an earlier drat othis book, to Caroline Williamson or her considerate editing, and toRhonda Black and the Aboriginal Studies Press team.

As always, I am deeply grateul to Heidi, Nazih, Dina and Yassin or

accepting my choices, visiting me as oten as they can, and looking aterme rom aar.More than anybody else, that Jampijinpa, Nicolas Peterson, deserves

my gratitude. Without him, this book would have never been written.He rst suggested a PhD to me, he assisted me in coming to ANU and

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

10/213

Acknowledgments

x

acquiring my scholarships, was the best supervisor a student could wishor and continues to be a wonderul riend. He helped me through everycrisis, no matter whether at Yuendumu or Canberra, pushed me and my

work when pushing was needed, always welcomed me in his oce, eveni it was three times in a day that I bothered him, and to this day mostgenerously splashes red ink over everything I give him to read. Thankyou very, very much or looking ater me proper.

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

11/213

I ollow the Warlpiri spelling as taught by the Institute or AboriginalDevelopment, Alice Springs, and at Yuendumu School, based on theorthography developed by Kenneth Hale (or more inormation seeHale 1990). Warlpiri words are italicised on the rst occasion that theyare used.

All Warlpiri words used in this book are listed and translated in theglossary at the end o the book. I have relied extensively on an electronic

copy o the manuscript o the Warlpiri dictionary made available byRobert Hoogenraad. Next to the anthropological literature, the Warlpiridictionary was the most used source in this book. As it is unedited,unpaginated and comes in a number o les, I have not been able toreerence it properly. All elaborations on Warlpiri words in the book

were made in accordance with it, and i I ound a dierent use thanthose listed in the dictionary, it has been noted.

A number o Aboriginal English terms are also used, and are typesetin italics to distinguish them rom dierent meanings they might holdin standard English (e.g. camp and camp).

Kinship terms are sometimes presented in tables and gures using thestandard abbreviations: M = mother; F = ather; D = daughter; S = son;Z = sister; B = brother; C = child; W = wie; H= husband.

note on spelling And orthogrAphy

x

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

12/213

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

13/213

Yuendumu Everyday

x

Figure 1: Ca Auaa

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

14/213

The starry night sky above us, we had arranged piles o blankets andpillows so that we could lounge comortably on top o our mattresses,a re crackling cheerully on the side, and a television set on a longextension cord in ront o us. We were watching Who Wants To Be A

Millionaire, a game show popular in Yuendumu. Tamsin, a seventeen-year-old Warlpiri girl, came to join our row o bedding, nestling down

between her mother Celeste and mysel. Who wants to be a millionaire?the game master asked on the television. Me, me, me, the residents othe camp shouted in reply, Tamsin loudest o them all. What would youdo with a million dollars? I asked her.

Tamsin: I would build a house.Yasmine: Where?Tamsin: In Yuendumu.Yasmine: And what will it look like?Tamsin: Its really, really big, with lots o rooms, and every

room has urniture in it. Soas, and beds, newblankets, and tables and chairs. And every room has astereo in it, and a television, and a video player and aplaystation.

Yasmine: And who will live in that house?Tamsin: Me.

Yasmine: And who else?Tamsin: Nobody else. Just me!

Yasmine: Wont you be lonely?

Tamsin: No, Ill have peace and quiet. And Ill keep the doorlocked. I wont let anybody in.

1

ChApter 1

Everyday life in a remote

Aboriginal settlement

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

15/213

Yuendumu Everyday

2

The antasy o winning a million dollars provides a license to dreamabout what one desires most. Since ever having access to so much moneyis utterly unrealistic or most Warlpiri people, the dream might as well

be about something one will never get, acquire or achieve. In Tamsinscase this was her own new house lled with large numbers o desirableitems such as new blankets, video recorders and playstations. This isunderstandable enough, given the impoverished material circumstancesin which people at Yuendumu live and the long waiting lists or council-provided housing. Her desire or material goods is identical to that omany other Warlpiri people.

But there was more to the antasy. As I lay on those swags, cosy notonly because o the warmth o the re, the blankets and pillows, butalso in the presence o the people around me, my body comortablysnuggled close to those o my riends, curled around Tamsin on oneside and with Greta behind me, her arm slung over my waist, Tamsinsdesire to be alone in that dream house struck me as extraordinary. Livingin the campso Yuendumu, I had taken quite some time to get used tobeing constantly surrounded by and involved with other people all day

and every day. Whenever I sat down with a book in the shade o a tree,people immediately joined me and started conversations, assuming I wassad or lonely. Once I went to get rewood on my own, only to get intotrouble aterwards. I could have been bitten by a snake! Gotten lost!Been assaulted by strangers or spooky beings! And had I orgotten thepeople who were looking aterme, those who were responsible or me?Imagine the trouble they would get into i something happened to me!

No, being alone was never an option in Yuendumu. And ater a while

I came to appreciate the constant company, and even to depend onit. Once I stayed in a riends guestroom in Alice Springs, and wokeup panic-stricken in the middle o the night, because I couldnt hearanybody else breathing!

O course, relations werent always as smooth as they were on thatevening we were watchingWho Wants To Be A Millionaire. Fights brokeout requently and then people let the company o those they were

ghting with, but only to join others, never to be alone.Yet here was Tamsin yearning or a space that was hers and hers alone.While her desire or material goods can be understood literally, the spaceinside the house requires, I believe, more interpretive work, and canbe better read in ways suggested by the French philosopher GastonBachelard. His The Poetics o Space (1994, rst published in 1958) is

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

16/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

3

a psycho-philosophical treatise on the house as a primary metaphor inthoughts, memories, and dreams. He describes how it is reasonable tosay we read a house, or read a room, since both room and house are

psychological diagrams that guide writers and poets in their analysis ointimacy (1994: 38). This is not only true o poets and writers. Tamsinsantasy house strikes me as an excellent i puzzling diagram o heranalysis o intimacy. The house in her antasy is a space she can onlydream about. It is a space where she is independent: the house containsquantities o everything she needs. It is a space lled with peace andquiet, where she is happy. It is a space where she is in control; she holdsthe keys to the doors.

Why would a seventeen-year-old Warlpiri girl living in Yuendumuormulate such a curious desire? The answer lies, I believe, in consider-ing more deeply the issue o intimacy. What does Bachelard mean byintimacy when he calls the house a diagram o an analysis o intimacy?

As I understand him, he conceptualises intimacy as a kind o innermostprotected idea o selhood, a way o being and seeing onesel. I weare to truly understand what Tamsin expresses in her antasy, we need

to understand not only the wished-or intimacy, but how and whythis diers rom more common Warlpiri orms o intimacy. Thesend expression in the ways in which Warlpiri people dene theirpersonhood in everyday social practice by relating to each other.Exploration o such Warlpiri expressions o intimacy opens pathstowards understanding the contradiction inherent in Tamsins wish or ahouse o her own, with keys to lock the doors so she can exclude others,

while at the same time dening hersel through relating to others. This

contradiction arises, I contend, out o the dynamics between the socialpractices o contemporary everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlementand the realities o living in a First World nation state.1 Exploring thesedynamics and the meanings encapsulated within them is the central aimo this book.

My way o approaching this aim is to urther problematise, question,and unpack the metaphor which encapsulates the space o intimacy o

Tamsins antasy: the notion o the house. Bachelard (1994: 6) aims toshow that the house is one o the greatest powers o integration or thethoughts, memories and dreams o mankind. I do not wish to diminish

what he says about the house; in act, I believe its metaphoric potencycannot be emphasised strongly enough. However, I take issue withextending this metaphoric potency to all o mankind in a unied way.

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

17/213

Yuendumu Everyday

4

While Bachelard shows howthe house has great metaphoric potency,I nd that the essay Building Dwelling Thinking (1993, rst publishedin 1951) by the German philosopher Martin Heidegger best explains

whythis should be so. He identies the ways these three practices arerelated to each other. In order to dwell, one has to build; and the wayone builds mirrors the way one thinks: which in turn is inspired by the

way one dwells, creating a processual cycle. This goes beyond Bachelard,who asks: i the house is the rst universe or its young children, the rstcosmos, how does its space shape all subsequent knowledge o other space,o any larger cosmos? (Bachelard 1994: viii).2 In Heideggers idea thereis no unidirectionality; instead he demonstrates how the three practicesare interdependent and how, as a series, they encapsulate ideology; andby that I mean nothing more or less than a socio-culturally specic wayo looking at the world and being in the world. The ideology, or themultidirectional connectivity between the physical structures in whichpeople live (building), their social practices (exemplied through theirpractices o dwelling) and their world views (thinking), can be expressed and here Bachelard again is useul in metaphors o great potency. In

the Western context, this ideology can be symbolised by a stereotypicalhouse:

In his essay, Heidegger commences his theory on buildingdwellingthinking with the assertion that the verbs to build, to dwell and to thinkstem rom the same etymological root in Germanic languages. From this

alone we can iner that Heidegger is concerned with a socio-culturallyand historically particular series o buildingdwellingthinking, valid inGermanic or, more contemporarily, Western contexts. The etymologicallink in his particular example is interesting but dispensable; signicantare the meanings he attaches to the series, meanings which substantiallytranscend the linguistic level. My point (not necessarily Heideggers) isthat it is more than likely that the same series may exist with dierentimplications but equal potency in other (non-Western) contexts,independent o the presence or absence o etymological links. I this istrue, then such ideologies, or the interconnectivity between the physicalstructures in which people dwell, their social practices and their worldviews, can be metaphorically encapsulated in symbols or dierentphysical structures o domestic space. Such symbols representing the

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

18/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

5

physical structures express the integration or the thoughts, memoriesand dreams o the people who live in them. In short, each such symbolcan be taken as a metaphor embodying the socio-cultural series o

buildingdwellingthinking and encapsulating a particular way olooking at and being in the world.

I propose that in the Warlpiri context the term that encapsulatesthe parallel metaphoric load to the house in the Western context isngurraa conceptual term o proound depth, encompassing multiplelevels o meaning ranging rom the mundane to the ontological. Mostimmediately, ngurra can be translated as camp, burrow, or nest; butthis meaning o shelter expands to include place, land, country, andatherland. On an emotional plane ngurrameans home, as well as theplace with which a person is associated by conception, birth, ancestry,or ritual obligation. Socially its meanings encompass the people livingin one camp, being one amily, being rom the same place. Temporally,ngurra is a label or the period o twenty-our hours, and is used todesignate numbers o days or nights. Lastly, it is used or socio-spatialdesignations during ritual. Warlpiri people have two iconographic

representations or ngurra:

concentric circles which may serve to represent the entire range o meaningslisted above, or any context-specic ones; and

a combination o one horizontal and a number o vertical lines.

The latter iconographic design always denotes a specic camp inwhich particular people have slept, with the horizontal line depictingthe windbreak and each vertical line standing or a person.

Following the Warlpiri iconography, throughout this book I use therst design o concentric circles and the Warlpiri term ngurra whenI reer to the entire range o meanings, and the Aboriginal Englishterm camp and the iconographic depiction using lines when reerringto a particular camp or when reproducing maps o particular sleepingarrangements. In short, acamp is one o many possible maniestations,

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

19/213

Yuendumu Everyday

6

and represents only one o a number o levels o signication containedwithin the term ngurra. Or, put dierently, acamp in this regard is theequivalent o an actual house (rather than the house as symbol). In terms

o the series o buildingdwellingthinking, acamp and an actual houseare both maniestations o two aspects, building (the material structure)and dwelling (social practices o relating to domestic space). Ngurra,on the other hand, encapsulates the entire Warlpiri series o buildingdwellingthinking; as a term, concept and metaphor it contains Warlpiriideology in exactly the same way as the metaphor o the house does inthe West. From this it ollows that we can say that

represents buildingdwellingthinking in the West, and

represents buildingdwellingthinking Warlpiri way.Since the creation o the settlement o Yuendumu, sedentisation

and the advent o Western-style housing as entailed in the processes ocolonialism and post-colonialism, Warlpiri people have been experiencingan intersecting o these two series o buildingdwellingthinking.This intersection shapes the contemporary settlement everyday, thosethings that people consider normal, routine and mundane; it shapes

contemporary Warlpiri ways o being in the world. It also shapes Tamsinsantasy. Here she is, wishing or a house, her own, just or hersel, andsmack-bang in the middle o Yuendumu, no less, while cosily snuggledup to her mothers in acamp. Taking into account her way o being inthe world, her experiences o settlement lie, her lie history, we must askourselves whether she wishes or a house and only a house, or whetherthe imagery o the house in her antasy also stands or something else.

Like those pictures used in psychological testing, in which, depending

on how one looks at them, one sees either an old woman or a young onebut never both, houses at Yuendumu, I contend, also have at least twomutually exclusive meanings. The house, which at Yuendumu materiallyembodies the intersection o the two series o buildingdwellingthinking, in Tamsins antasy is a vehicle or expressing a particular

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

20/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

7

desire; but it can also stand or the expectations which the Australian

state has o Warlpiri people.

t awk kI we credit the house with the metaphoric potential which Bachelard

ascribed to it, state-provided housing can be viewed as carrying a

specic agenda: the imposition o a particular way o thinking.3 This

goes some way to explain why housing, rom the onset o the Australian

states engagement with Aboriginal people, has been and continues

to be among the biggest items in Australias annual Aboriginal Aairs

portolio budgets, consistently accounting or between 25 and 35 per

cent o the total (Sanders 1990: 41).4 Viewed rom the perspective o

the Western series o buildingdwellingthinking, Yuendumu houses

stand or the expectations the state has o Indigenous people that

they become like us. The always over-crowded, oten dysunctional

and partly derelict houses at Yuendumu become an expression o the

Warlpiri ailure to comply, a ailure to be in the world in acceptable

ways. Yet Warlpiri people want Western-style houses: council discussions

o housing allocation are by ar the most heated as well as the bestattended meetings; and Tamsin, asked what she would do with a million

dollars, answers that she wants a house.

Why do Warlpiri people want those suburban houses so badly, seeing

that their practices o dwelling and their ways o thinking about and

being in the world confict so starkly with the values that houses are

imbued with in the mainstream? In order to understand more ully

the nature o the contradictions between the states expectations and

Warlpiri peoples desires, I employ the lens o the intersecting series

o buildingdwellingthinking to the ethnographic data presented

throughout this book.

The ethnography o this book is based on the dramas o everyday lie

as they unolded in the campso Yuendumu during my eldwork, andparticularly revolves around the three values that seemed to shape the

everyday as I experienced it: mobility, intimacy and immediacy. I suggest

that these values (mobility, immediacy and intimacy) are constitutive othe contemporary settlement everyday because they are maniestations

o the Warlpiri series o buildingdwellingthinking. In order to make

this case, to convey a sense o the eel o Yuendumu everyday lie, to

illustrate the interconnectedness between intimacy, immediacy and

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

21/213

Yuendumu Everyday

8

mobility, and to shed light on the particular socio-cultural orms thesetake, I provide extensive case studies o signicant everyday interactions,situations, conversations, and experiences.

The clues to understanding the ways in which people are in theworld and the view(s) they take o the world lie hidden underneath thecommonplace, and can be revealed by analysing the everyday. By theeveryday I mean those things that people consider normal and oten(no matter whether in an Indigenous or non-Indigenous context) not

worthy o refection. The strength o anthropology as I see it, and hereI am drawing on Outline o a Theory o Practice (1977) by the Frenchsociologist Pierre Bourdieu, lies in understanding and explaining exactlysuch apparently mundane matters as who sleeps where and next to

whom; why people are mobile in the way they are; where the boundariesbetween public and private lie; how ood and other material items aredistributed; how people relate to each other; and what we can learn romthe ways in which people use their bodies. Kinship, ritual, exchangeand so orth all can be ormulated in esoteric terms, but ultimately,I believe, they need to be understood as grounded in and arising out

o everyday social practice. Primarily ocussing on the ormer, anthro-pology has largely ignored the contemporary everyday o remote

Aboriginal settlements.5

The case studies in this book centre around one particular camp(ajilimior womens camp) at Yuendumu, and I use them to consider

Warlpiri peoples high residential mobility by examining the fowo people through camps. I present examples o Warlpiri sleepingarrangements, which change on a nightly basis, and interpret them as

expressions o the current state o social aairs and statements about theperson. These discussions are ramed with a view o understanding theconnections between people and how they are negotiated, reinorced,maintained or broken; or, how Warlpiri ideas o intimacy are lived outin everyday lie. I also explore Warlpiri sociality during the day, mappingthe movements o people in and out o camps and throughout thesettlement, to elaborate how the particular eeling o immediacy, that so

characterises the contemporary Yuendumu everyday, is created.The contemporary everyday, however, cannot be understood withoutrelating it to the beore. The relationship between then and nowentails continuities, changes and ruptures which critically shape the hereand now. The most decisive date o rupture in this sense is 1946, the

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

22/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

9

year Yuendumu was set up as a government ration station. Analysis ocontemporary everyday social practice at Yuendumu needs to proceedrom an understanding o what the situation was beore 1946, and what

has happened since to aect it. In regard to this crucial date, Warlpiripeople themselves distinguish between two types o historical past: 6 the

olden days and the early days. The Aboriginal English term olden daysis used to label pre-contact and early contact times, characterised by anomadic liestyle, a hunting and gathering economy and an elaborateritual lie. Early days, on the other hand, is the period o initial settlementand strict institutional control which brought with it, among otherthings, Christianisation, sedentisation, and a new economy.

Quite a ew people still alive today experienced the olden days,growing up and living in the bush beore either coming voluntarily orbeing brought by orce to live at Yuendumu. Others do not rememberthe olden days themselves and grew up during the early days. Theirchildren and grandchildren, on the other hand, were born and raised in

Yuendumu; to them the olden daysand the early daysare known as storiesrom the past, and their lives and histories are intricately linked with the

settlement o Yuendumu as their home.Throughout the book, Iexamine some o the key ruptures, continuities

and transormations in social everyday practices that have taken place inthe last sixty years or so. I ocus on the impact sedentisation has had onsocial practices relating to domestic space, elaborating on past as well ascontemporary residential arrangements, and within this specically theincreased signicance o womens camps, or jilimi.7 I suggest that jilimiand their older emale residents have become central oci o everyday

social lie generally, in particular or young mothers and their children.Also, I establish how lie in the jilimi is intensely social, not least sincethe great majority o people who pass through them are unemployed andlive on social security payments. Inclusion o this historical perspectiveallows me to illustrate how contemporary orms o intimacy, immediacyand mobility are the result o Warlpiri engagements with both thepresent and the past.

The arena within which I explore these contemporary orms lies inthe interplay between Warlpiri peoples social practices and the spatialityo the settlement, which enables me to analyse more precisely the

ways in which the two series o buildingdwellingthinking intersectat Yuendumu. The crux o the book, then, is to unveil the meanings

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

23/213

Yuendumu Everyday

10

contained in Tamsins antasy and through this to elucidate how and

why the imagery o the house can serve to express the dilemmas o

contemporary settlement lie.

Fwk, a a k a

I began research at Yuendumu in 1994, and I have returned there every

year since. The most concentrated research took place between 1999 and

2001, during which time I lived at Yuendumu or eighteen months. The

Warlpiri everyday described in this book is dierent rom the everyday

o previous decades, and, it can saely be assumed, will be dierent again

rom everyday lie in the uture. I emphasise this temporal dynamic o

the ethnographic present by using the past tense and the present tense

interchangeably in the descriptive parts. The past tense fags that the

period o research or this book is over, and things are already changing.

People have passed away, children have been born, new marriages have

been made and others have deteriorated, and government policies

and incomes have changed, as indeed has the physical appearance o

Yuendumu. New houses are being built, others have allen into disuse,

humpies(shelters o corrugated iron and bush materials) occur less andless oten, there seem to be ewer jilimiand many are smaller than they

were in the 1990s, new roads have been sealed, and so orth. The present

tense, on the other hand, is used as a literary device to convey the distinct

atmosphere o the immediacy o everyday lie at Yuendumu.

Fieldwork was conducted in classical participant observation style.

Since 1994 I have spent more than three years in total living in campswith Warlpiri people, who, ortunately, insisted on my incessant

participation in everything they themselves were involved in. My co-

residents, neighbours, riends and I experienced the everyday I describe

and analyse, and this everyday was created, lived and shaped by all o us,

including me.

There is no point even trying to write mysel out o the book.

While I doubt that I caused major shits and changes, my presence and

participation was certainly responsible or the crystallisation o certain

disputes that otherwise may have lain dormant, and or an increasein options or a number o people through access to my resources, in

particular my Toyota.8 The Warlpiri view o Toyotas is that they should

run until they die. This meant that as soon as I arrived back in the camprom one trip, other people turned up (or were waiting already) requesting

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

24/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

11

a lit, a rewood trip, or just to go cruisingaround the settlement. Onaverage, I drove about 1000 kilometres a week. A substantial part o

this mileage was taken up by just driving in and around Yuendumu, but

we also requently went urther aeld. The Toyota loaded to maximumcapacity, we went on hunting trips throughout the Tanami Desert; we

drove to settlements all around central Australia to visit peoples relatives

or to participate in Sports Weekends; we travelled in large convoys or

sorry business(mortuary rituals), womens business(womens ceremonies),and business (initiation ceremonies); and o course we oten went to

Alice Springs (to shop and to visit people in hospital and in jail). Having

the Toyota in the eld also allowed me to gain a comprehensive insidersview o Warlpiri mobility.

While participation in such extensive mobility was physically exhau-

sting, immediacy was a challenge in other ways. Immediacy shaped my

eldwork every day in multiple ways, and I struggled to come to terms

with it (and in the end, came to miss it very much when away rom

Yuendumu). Immediacy meant that I could not plan ahead. Specic data

collection, language lessons, everything happened when it happened,

rather then when I wanted it to happen. Big events (such as mortuaryrituals in the case o death) overruled any other activity, but even without

them, everything had to be slotted in with what was happening in the

settlement on that particular day, and coordinated with large numbers

o people and their assorted ideas and desires. Appointments simply

did not work. Once I let go o my ideas o scheduling and planning

(and believe me, this was no easy task!), once my lie and my eldwork

agendas ell into sync with whatever it was that happened on any given

day in Yuendumu, I discovered a way o being in the world very dierent

rom the one I was used to. There is a undamental dierence between

waking up in the morning and knowing what lies ahead and waking

up in the morning ull o curiosity about what the day might bring.

It not only meant experiencing time in new ways, but also entailed a

undamental shit in my ways o relating to others. Immediacy meant

that rather than seeking to ull my own desires (be they a particular

interview, a hunting trip, or listening to olden timestories), I learned tohave them ullled by ully participating in the collective push and pull

o being in the present.

This, in turn, taught me much about Warlpiri orms o intimacy,

o how to know and how to relate to others in Warlpiri ways. Many

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

25/213

Yuendumu Everyday

12

anthropologists beore me have noted the Aboriginal maxim o knowingbecause o doing (rather than through verbal answers), and this isnot only true or ritual but also or everyday lie (see amongst others

Harris 1987; Morphy 1983; Myers 1986a: 294). Only through livingwith Warlpiri people, through being in the same space and time withthem, sharing activities and stories, and, not unimportantly, throughsubmitting to the wishes o others did I learn what intimacy in thissocio-cultural context means: a reciprocal awareness o the other as aperson, o their lie histories, their desires, their quirks, their habits, anda willingness to let this awareness infuence how one acts in the world.

Out o the three values underpinning everyday lie at Yuendumu,intimacy is perhaps the hardest to convey in a book. To bring somesense o it to the reader, most o the case studies revolve around a smallnumber o key protagonists, with the aim o amiliarising the readernot only with Warlpiri social practices but also with a range o actual

Warlpiri people.9Next to Tamsin, these key protagonists o the book are Tamsins

adopted mother Celeste, Celestes mother Polly, and two classicatory

sisters o Polly: Joy and Nora. Joy was my rst mother, as her husband,Old Jakamarra, had been the one who when I rst came to Yuendumuhad given me my skinname [subsection term] Napurrurla, thus makingme his classicatory daughter. This meant that I was henceorth ableto work out the ways in which I should relate to all Warlpiri peopleI met. As I was Old Jakamarras daughter Napurrurla, Joy Napaljarribecame my adopted mother, as did all other Napaljarri women. Inthe same way, I would now relate to all other women with my own

skinname, Napurrurla, as my classicatory sisters, Celeste amongstthem.10 Nora, another Napaljarri and hence mother o mine, was oneo my co-residents in the jilimi (and in some other campslater on), andinstrumental in my education about olden daysand early days. Ater I hada ght with Joy, Polly adopted me, and to this day in Yuendumu I amknown as Polly-kurlangu, belonging to Polly. These our women weresome o my key inormants, and those still alive remain close riends,

and indeed adoptive relatives.In this book I introduce dierent aspects o these our women: howthey relate to each other, how they related to others in the camp we

were staying at the time, how they presented their selves in the ways inwhich they positioned their bodies at night, and how they cooperated

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

26/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

13

with some people and ought with others. All o these descriptions arepresented by me as author. As the nature o my own personal relationshipto each o these women is particular and unique, I here provide sketches

in narrative orm about the personal ways in which I related to them,recapitulating interactions between these women and mysel as they tookplace around the time we all lived together in the jilimi. These vignettesrepresent my own portraits o the our women as I experienced them,and hopeully will convey to the reader the nature o our relationships,

which, I am sure, has impacted on how I represent them in the casestudies throughout this book.

Joy Napaljarri, my frst mother

In the evenings, Joy and I oten sat around the re, telling stories. Manywere about other white women Joygrew up. And then I helped thatanthropologist, but she let me or that West Camp mob, and thatlinguist, she let or Leah, and that Womens Centre coordinator, shelet, too. Her stories inevitably ended with: And now I got Napurrurla,she is like a real daughter, shell look ater me or a long time, and when

I get my house, shell move in, too. Joys name was right at the top othe list at council; the next house to be built in Yuendumu was goingto be hers. When we move into that house, it wont be like those otherhouses, our house will have a garden with fowers and an orange tree,and a green lawn. Inside, therell be curtains, and chairs and soas, andpictures on the walls. And everybody will have their own room. Oneor me and Kiara [her grand-daughter], one or Napurrurla and one orLydia [her daughter]. I liked sitting around that re, in the evenings

and sharing dreams and oten it reconciled us ater the clashes wehad during the day. It was nice to be compared avourably to the otherKardiya [Whiteella] women, those ones that let Joy. Sitting aroundthat re, we elt snug, warm and content, looking orward to the uture,

when our dreams would come true.In the jilimi, every once in a while, somebody, most oten Joy, would

decide it was time to clean. This place is a mess, lets clean up! Cleaning

means a trip to the shop to buy a rake, a broom, and Ajax. The rubbishin the yard would be raked up and burned, and the bathrooms would besprinkled with Ajax, scrubbed with brooms and hosed down with water.One time, Joy said to me, Go back to the shop and get some Pine-O-Clean. When I came back, she opened the bottle, generously splashed

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

27/213

Yuendumu Everyday

14

it all over the bathroom and stood in the middle o it, her hands on herhips, looking expectant. Ater a couple o minutes, her ace dropped andshe murmured, Maybe it only works or Whiteellas.

In the end, Joy and I did not get along, and I, like all the other whitewomen beore me, let her. I always elt I disappointed and hurt hergravely. Her biggest dream was having her own house, Kardiya-style,and she knew that on her own she could not create and maintain asuburban dream house in the middle o Yuendumu. Her hope was thatmy presence, the presence o a Kardiya in her house, would achieve that.

We ought a lot, and when she nally got her own house, I decided tostay in the jilimi and did not move in with her. I always elt that or herI was a disappointment in the same way the Pine-O-Clean was. In adson TV she had seen what it could achieve: clean gleaming bathrooms

with tiles in which your ace would be refected. The Pine-O-Clean didnot ull its promise, that bathroom never sparkled, and I did not movein with her; and thus, although she was so close to achieving her dreamo living in a Kardiya-style house, it was always my ault that it did noteventuate.

Celeste Napurrurla, my sister

The rst time I saw Celeste, I was living in Old Jakamarras camp andshe came over to pick up Joy or a Night Patrol shit. Celeste is small,a head shorter than me at least. There she was, looking erce in a largeblack bomber jacket with NIGHT PATROL written in silver letters onthe back, swinging a bignullahnullah in her let hand, a black beanie onher head. Ater she let with Joy I said to Old Jakamarra, Who was that?

He chuckled. Your sister that one.Later, Joy and I moved into the jilimi and Joy resumed working ull

time at the schools Literacy Centre. Because o that and her many otherresponsibilities, she asked Celeste to keep an eye on me and make me teaand damper in the mornings. In retrospect I think the main reason sheasked Celeste and not anybody else was that she never perceived Celesteas a threat in respect to her ownership o me. Celeste is excellent in

arranging domestic matters, but nobody thinks she is too bright whenit comes to politics; neither is she pushy. And while Celestes value as ananthropological inormant is most limited, as a person to hang out with,to live with, and to be around, she is bliss.

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

28/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

15

Celeste made sure I had a break once in a while. This is not to saythat she didnt have her own agenda. She was working around the jilimiall day long, looking ater children and old people there, preparing ood

and organising rewood and sleeping arrangements, and it was whenshe insisted I needed a break that she could have one, too. And in themornings we managed to stay in bed longer because o each other. I keptthinking, As long as Celeste is not up, I wont need to get up either. SoI spent contented extra minutes in my swag listening to the clatter inthe jilimi, pretending to be still asleep, once in a while peeping out romunderneath my blankets to make sure Celeste was still asleep underneathhers. One morning as I emerged or a quick glance, she did the same atthe same moment. Having caught each other at it, we laughed and shesaid, Oh, now we have to get up ater all.

One o my avourite memories o Celeste is o a very, very hotsummer aternoon when we borrowed a an and went into her room tohave a siesta. There we are lying on the blankets with the an keeping usmoderately cool. Celestes steady breathing next to me is as always themost soothing sound. I keep driting in and out o sleep, once in a while

opening my eyes or a glance to the outside. Through the hal-open doorI can see the roo o the verandah, the wall dividing the verandah romthe yard and in between them a strip o blue, blue sky. Occasionallythere is a cloud in it, sometimes two; sometimes there is none.

Nora Napaljarri, another mother

When nally, ater many months, I had my big ght with Joy and thetwo o us stood on the jilimis verandah yelling at each other, it was Nora

who ended our ght. She was sitting at the other end o the verandahnext to a small cooking re, making tea and damper. In the middle oour yelling, she calmly said, Napurrurla, come over, your tea is ready. I

went and sat down with her, accepting a pannikin ull o tea and puttingchops on the re or us. Joy stormed o. When the chops were done,I gave one to Nora and one to Polly and ate one mysel. Polly noddedtowards the door o Joys room and said, Too cheeky, that one. I will

be your mother now, and Nora nodded in agreement. Up until thatmoment I had not been sure whether the ght with Joy was a goodidea. Emotionally it was more than overdue; rationally I was unsureabout the consequences it would have. What I had not counted on was

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

29/213

Yuendumu Everyday

16

the presence o somebody like Nora, whose experience in politics andnegotiations is considerable.

Nora had won a medal rom the Queen or organising Yuendumu

Night Patrol, she had been a bigbusinesswoman, a skilul and experiencedsinger, dancer, and painter. She was cranky a lot when I lived with her,oten because she was ageing too quickly. While very much alive and ullo ideas, her bones hurt and walking became more and more dicult.To be limited by ones own body is most rustrating, and Nora did notgive in easily. To have been powerul once and now to be becomingjust another old lady was very hard or her. In turn, I oten ound herdemands on me a challenge, mainly because they were made with analmost royal air. There was no way to reuse a request o Noras. Thus, I

would drive her to the shop, to the clinic, to look or her grandson, orto go hunting, and I would bring her meat, tea, ruit, and sot drinksrom the shop whenever she asked. And it must be said that she alwaysreciprocated; she would sing songs or perorm love magic or me in theevenings, and sometimes she would slip me a twenty dollar note onpension days.

Two years ater I let Yuendumu, I rang up, as I oten do. This time, Norawas around and she came to the phone to talk to me. She told me about thehouse she had moved into in the meantime, about her grandsons, her sonsand other gossip. Then she said, Napurrurla, I am poor one, your motherhas no skirt and no blouse, no shoes and no blankets. This is the Warlpiri

way o asking me to send up some things or her, but as I was broke at thetime I had to tell her that I was dolla-wangu without money. Oh poorbugger, my daughter, she said. Ill send you one hundred dollar.

Polly Napaljarri, my mother

The rst day o cold time: my sisters and I return home to the jilimirom that days hunting. In our absence, the others have cleaned up. We

join them in the yard, where there are two res: one smouldering withlots o thick white smoke in which the rubbish burns, and one on whichNangala is making resh damper. The white smoke o the rubbish re

against the crisp blue sky reminds me o the potato res that are lit inmy German village in autumn. For the rst time in years I eel homesick.One o my grandmothers asks, Whats wrong, Napurrurla? and passesmy answer on to the others. Napurrurla is thinking o home, little bitsad one, poor bugger. Polly, without replying, gets up. She takes a rake

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

30/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

17

lying in the yard and starts to dance with it around the rubbish re.She dances, rst the way Warlpiri women dance in ceremonies, withquivering, slightly bent legs and abrupt movements. Then she starts

mimicking the movements o the young girls at disco nights: circlingher hips, aster and aster. Her dance becomes more and more lewd.Everybody claps and sings and laughs. At night, when my sisters andI are lying in our swags next to each other, we are still laughing. ThatPolly, shes clown woman, that one.

Some months later. I am in the Big Shop and have just heard the badnews. One o Pollys nieces has passed away. As I leave the shop, I canhear wailing coming rom all directions. I hurry to the jilimi and starthugging and wailing with the women who are sitting lined up on theverandah. As I turn around I see Polly. She is sitting alone, crouchedin the cold ashes o last nights re. She has already shaved o her hair,and her head and body are covered in grey ash. The only visible parts oher warm, brown skin are the tracks on her cheeks made by the food otears. Her wail pierces the aternoon air.

One day in summer, as I hang up my laundry on the barbed wire in

the yard strung between poles as a clothes line, Polly comes over. Thereare wet blankets on either side o us and it is like standing in a tunnel.Polly is not lively, demanding, noisy or intimate, like most o the other

women. She is quieter, and she mainly watches, mostly rom a distancethat she hersel determines. Sometimes she looks like a young girl andsometimes she looks as old as she must be. She has had two husbandsand eight children o whom our have passed away. She has twenty-two grandchildren and nineteen great-grandchildren. In the tunnel o

blankets, she comes towards me, touches my head, says My daughter,and then she is gone.

yuuu

Having introduced the key themes and the main protagonists o thisbook, what remains is to set the scene by introducing the settlement o

Yuendumu.11 Located in central Australia, Yuendumu is situated about

300 kilometres north-west o the town o Alice Springs, in the south-eastern corner o the Tanami Desert that stretches rom the NorthernTerritory towards Western Australia. Beore sedentisation, Warlpiripeople lived throughout the Tanami Desert, in an area roughly extending500 kilometres to the north-west, about 250 kilometres to the north and

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

31/213

Yuendumu Everyday

18

200 kilometres to the south o Yuendumu, and bordered in the east byAnmatyerre country. Warlpiri people had some previous experiences oengagement with non-Indigenous people rom intermittently living and

working at the early gold mines in the Tanami, the Wolram mine atMission Creek, and Mt Doreen pastoral station, and rom the horric1928 Coniston Massacre (see Michaels 1987; Hinkson et al. 1997).

The rst step in the governments eort to institutionalise sedentisationo Warlpiri people in the area was the setting up o three Warlpirigovernment ration depots by the Native Aairs Branch: Yuendumu,

Warrabri (now called Alekarenge) and Hooker Creek (now calledLajamanu). Thus was the settlement o Yuendumu born in 1946. Longdescribes the development o such postwar settlements as aiming to

control the shit o Aborigines to towns; to develop the potentialo the reserves; to train the Aborigines in order that they mightcontribute to the development o the reserves in particular ando the country generally; and to provide health services to the

Aborigines. (Long 1970: 199)

During the 1950s, a Baptist Mission was established at Yuendumu,and or a period o a ew years this mission had charge o the managemento the settlement. The mission ran a store, a school and a clinic, andlater a kitchen was added or communal meals. In the mid-1950s agovernment supervisor took over the administration and operation o thesettlement. Also around that time, the Yuendumu Cattle Company cameinto existence under government ownership and with workers wagespaid by the Department o Aboriginal Aairs (DAA).12 In 1959 social

security legislation was passed to include Aboriginal people, and rom1966 pensions and amily payments started fowing to them. However,payment was oten made via third parties, and unemployment payments

were not generally paid in remote areas. A push to have direct paymentswas instituted by Social Security and Aboriginal Aairs Minister BillWentworth in 1968, a year ater the 1967 reerendum that led to theCommonwealth Government assuming responsibility or various

Aboriginal issues (see Sanders 1986: 11516). At Yuendumu, direct andull payment o social security entitlements came into eect in 1969;simultaneously communal meals and the issuing o blankets ceased. In1978 the rst elected Yuendumu Council assumed responsibility orsettlement administration ater the withdrawal o DAA ocials.

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

32/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

19

O these developments, the direct receipt o social security hasbeen identied by most social scientists as the single most signicantactor determining the economic status o Aboriginal people and their

relationship to the state.13 Having carried out research in the late 1970s,Young wrote in relation to Yuendumu:

the town has virtually no economic rationale. It is neither amarket town, a mining centre, nor a centre or communications unctions which have been responsible or the growth o othertowns in the [Northern] Territory. It remains dependent on therest o Australia or almost every cent its community spends, and

every article consumed (Young 1981: 56).

During Youngs research, 19 per cent o the Indigenous populationat Yuendumu received wages; during my research, i CDEP work(Community Development and Employment Program, a ederal-government-run work or the dole type program or Indigenous people)is included as wage labour, the number was around 29 per cent, or,put dierently, Yuendumu had a 71 per cent unemployment rate. This

stands in bleak contrast both to the overall Australian unemploymentgures (around 6 per cent at the time o research), as well as to theoverall Aboriginal rate, which Sanders estimated to encompass 44 percent o non-employment income (Sanders, 1994: 1003). At the time o

writing, there is much uncertainty about these nancial arrangements,which were targeted in the Liberal Federal Governments NT Inter-vention in the second hal o 2007 (see Altman and Hinkson 2007 ordescriptions and critiques). While I am here not concerned with the

reasons underlying Yuendumus extremely high rate o unemployment,they do present a signicant context or the ethnography. The lack oemployment is a distinguishing actor o lie at Yuendumu; it is notonly expressed through statistics but maniested, as I attempt to showthroughout the book, in the ways Warlpiri people live their lives (see alsoMusharbash 2007).

Today, there are between 500 and 900 Indigenous residents livingat Yuendumu, most o them Warlpiri people (and small numbers o

Anmatyerre and Pintupi people).14 An additional 100 residents arenon-Indigenous. Socially, culturally, and socio-economically speaking,

Aboriginal people, locally called Yapa, and non-Indigenous people,locally called Kardiya, constitute two distinct populations.15 (Note that I

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

33/213

Yuendumu Everyday

20

ollow this local terminology throughout the book, and employ the terms

Kardiya and non-Indigenous people to reer to local non-Aboriginal

people and the terms Yapa or Warlpiri people or local Aboriginal

people.) In the main, Kardiya are living and working in Yuendumu asservice providers. Except or Yuendumu Council, which always has a Yapa

president (but a Kardiya town clerk), all organisations and institutions at

Yuendumu are managed by Kardiya sta (see Appendix or descriptions

o these organisations and institutions).

During the early days, Yuendumu had at its centre a gardened areaadjacent to the houses o the Missionary and the Superintendent.

Known as the Park, this area became fanked by an increasing number oKardiya sta residences and buildings or Yuendumus growing number

o institutions (the school, the store, the soup kitchen, the clinic, and

so orth). The residential arrangements or Yapa were located at some

distance rom the Park. Hinkson quotes two Yuendumu men describing

early developments o settlement at Yuendumu:

in those days, the houses were just a ew and onlykardiyawere

living in the houses. But us, we used to live out in the campsor humpies. We never used to sleep close to the houses or thesettlement at that time. We used to be a couple o miles, or at

least a air way rom the settlement and the houses. For water,

the women used to come and collect water with buckets and billy

cans, in the evenings and in the mornings. []

kardiya doesnt want yapa to come in close up becausethey might steal something. And yapadoesnt want to come in

(Japanangka and Japangardi quoted in Hinkson 1999: 18).

Stories I was told conrm that in the early daysthere was a mutuallymaintained separation between Warlpiri people living at a signicant

distance rom the centre o the settlement and non-Indigenous sta

living in houses and working in buildings located around the Park.

During these times, Yapa used to live in traditional shelters built out o

bush materials, sometimes augmented by corrugated iron and sackcloth

(so-called humpies). Above and beyond the spatial ordering o Kardiyaliving in centrally located houses and Yapa living in campsand humpiessurrounding the settlement, the locations o Yapa living quarters ollowed

the cardinal directions rom which people had originally come in to the

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

34/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

21

settlement. Munn describes this spatial ordering in the mid to late 1950sthus (see also Meggitt 1962: 55):

Mt. Doreen, Mt. Allan (and Coniston), and Vaughan Springsare areas that represent or the Warlpiri general regions in which

dierent sections o the Yuendumu community based themselvesin the recent past [...]. The camps o each segment are orientedaccordingly: Mt. Doreen Ngalia camp to the west or north-west,and members o the northern community o Waneiga Warlpiricamp with them; the Mt. Allan Ngalia (also linked with CockatooCreek near Coniston) camp on the east or south-east o the other

camps; the Vaughan Springs (and Mt. Singleton) people camp inthe south-easterly clusters (Munn 1973: 11).

With the advent o the provision o housing or Aboriginal people atYuendumu, more substantial residential arrangements began to surroundthe central administrative area, bringing Yapa closer to the settlement romtheir corresponding quarters and into more permanent structures. Thesestructures (originally crude one- and two-bedroom huts with communal

ablution blocks; see Keys 1999 or details o structures and history ohousing at Yuendumu) were arranged in clusters, and over time theseclusters became named and suburb-like entities. Originally there wereour such suburbs, named ater the cardinal directions as seen rom thePark: East Camp, South Camp, West Camp and North Camp. (I spellCamp with a capital C when reerring to one o Yuendumus suburbs,and with a lower case c and in italics when reerring to individualresidences, camps.) Much has been made o this socio-geographical

patterning o Yuendumus our Camps, and more recent ethnographieshave perpetuated the earlier observations by Munn and Meggitt (seeamongst others Michaels 1986, 1994; Rowse 1998; Young and Doohan1989). Jackson or example, obviously picking up on earlier reports byMeggitt and Munn, discusses location as an index o social identity andclaims that in Yuendumu, or instance, people rom dierent parts othe country live in dierent quarters (1995: 19).

By claiming that orientation to traditional country determinesresidency, the our Camps have eectively been presented as not onlyresidential units but as social units based on shared country aliations.I this was the case originally, it is not true today. Lie histories reveal thatmost Yuendumu residents have lived in dierent Camps at dierent times

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

35/213

Yuendumu Everyday

22

o their lives, with their residential choices motivated by a multiplicityo reasons, most o which do not have anything to do with countryaliation.16 Looking at the composition o any one Camp today makes

clear that its residents originally came rom a number o areas. Moreover,the residential compositions o Yuendumus Camps are in constant fux.The two interrelated issues o slow encroachment towards the Park andthe splitting and growth o urther new Camps compound this.17

Nowadays, Warlpiri people live in and name six Camps at Yuendumu:North Camp, South Camp, East Camp, West Camp, Inner West Camp,and Kulkurru Camp (see Figure 2). West Camp and Inner West Campare separated by a ootball oval and have both independently grownso much that they are now considered to be two separate suburbs, orCamps. However, Kulkurru Camp is particularly pertinent, as it is themost recent. Kulkurru is the Warlpiri word or inside; and this Campis right next to the Park. Houses in what is now called Kulkurru Campused to be exclusively occupied by non-Indigenous residents, but overthe last decade or so Warlpiri people have moved into some o thesehouses, showing that the encroachment on the Park is continuing.

Signicantly, it was around the time that Warlpiri people moved intothis part o Yuendumu that it acquired its Warlpiri name.

An inverted development is currently taking place in Yuendumussouth-west, in an area nicknamed Kardiyaville by some o the non-Indigenous population, because it has by now the largest concentrationo non-Indigenous people and also experiences the greatest growtho new houses designated or non-Indigenous use.18 Kardiyaville is acluster o sta houses owned by the Department o Education and the

Yuendumu Council, and more recently also by Warlpiri Media, the MtTheo Substance Misuse and Youth Program, and the Clinic. Kardiyavilleis located between Yuendumus South Camp and Inner West Camp.

So what is Yuendumu like today? Except during the big summer rains,the drive rom Alice Springs to Yuendumu takes three to our hours. TheTanami Road (which connects Alice Springs in the Northern Territoryand Halls Creek in Western Australia, crossing the Tanami Desert) is

not the rough track it once was; the rst hal between Alice Springsand Yuendumu is bituminised, and the rest is wider and is graded moreregularly than beore. More Yapa have cars than even a short time ago,and bigger cars as well, and there is a regular fow o trac between

Yuendumu and Alice Springs. The Yuendumu turn-o rom the Tanami

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

36/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

23

Road leads down two kilometres o partially sealed road, now fankedby small Arican mahogany trees planted by local CDEP workers, pastthe Police Station, and some occasional humpies, into YuendumusEast Camp, and continues towards the Park. There the corrugated tinruins o the old soup kitchen still stand, but are surrounded by an ever-growing number o newer buildings: the Old Peoples program, thenew Council building, the new clinic (see Figure 3). On weekdays thisarea is bustling. People walk along the our streets fanking the Park, on

Figure 2: saa Ca v a yuuu

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

37/213

Yuendumu Everyday

24

Figure 3: yuuu ( Ax, . 158 c a

aa ).

1 Jilimi

2 Clinic

3 Warlpiri Media and Adult

Education

3b Youth Centre

4 Baptist Church5 Big Shop

6 Warlukurlangu Aboriginal Artist

Assoc.

7 Mining Co. Garage and Store

8 CDEPOfce

9 CouncilOfce

10 School

11 CentralLandCouncilOfce

12 Old Peoples Program13 Womens Centre

14 Childcare Centre

15 Police Station

16 Council Garage

17 Powerhouse

A Football Oval

B Basketball Court

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

38/213

Everyday lie in a remote Aboriginal settlement

25

their way to one organisation or another, to the shop, or the post oce.Government and Yapa Toyotas drive around, picking up and droppingo people. Beyond the Park, in the Camps, the red Tanami sand is more

prominent, a reminder that Yuendumu is indeed a desert settlement.Around the Yapa houses there are the obligatory packs o camp dogs,people sitting in groups in the shade or around their res, and little kidsrunning around playing. Music, both Yapa and Western, echoes rommany o the houses, as well as rom cars driving past. I it is windy, asmall whirlwind might sweep through, carrying with it more red sand,empty chips packets, and perhaps someones laundry. Kardiya housesare quieter and have higher ences, and some have gardens, religiously

watered by their owners in an attempt at deying the desert.All in all, Yuendumu is very much a typical central Australian remote

Aboriginal settlement. It is bigger than most some say it is the biggestin central Australia. And, o course, having started as a governmentration station rather than a mission has its own implications, as doesthe act that it accommodates a Baptist mission rather than some otherdenomination. A crucial dierence between Yuendumu and most

other settlements is that most o its organisations and institutions areindependent o the council, meaning that many are more dynamic thantheir counterparts elsewhere, and also that Yuendumu has a much higherKardiya population than most other settlements (both in total numbersand in proportion to the Yapa population). In the campshowever, thesedierences are hardly noticeable. Accordingly, much o what is presentedin this book did take place at Yuendumu, but could have happened inany one o many other remote communities.

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

39/213

26

The realities o everyday lie at Yuendumu are characterised by theintersection o the Warlpiri and the Western series o buildingdwellingthinking, a highly complex, ongoing and multidirectional social process.

A rst step towards understanding this process, and hence, the meaningscontained in, expressed by and created through the contemporaryeveryday, lies in analytically disentangling dierent strands o the

intersection.I begin this work o disentangling by drawing on some anthropolo-gical analyses o the relationship between meaning and domestic space.These originate rom the vast anthropological literature on the socio-cultural signicance o structures o dwellings, beginning perhaps, withLH Morgan (1965, rst published in 1881).1 However, this litera-ture has two shortcomings in regards to conceptualising how Warlpiripeople interact with Western-style state-provided houses, which need to

be acknowledged.First, this literature has generally taken the house as a key symbol

expressing world views. Put dierently, anthropologists have displayedan overwhelming tendency to ocus on the house, while other ormso domestic structures, such as camps, igloos, caves, caravans and soorth, have largely been ignored. That is to say, anthropologists working

with people who have domestic structures resembling a Western house(dwellings possessing walls, doors and ceilings) have undertaken studiesin this vein, whereas anthropologists working with people living indierently structured dwellings have rarely ocussed on issues relatingto domestic space. Some might argue that dwellings that are unlikehouses do not lend themselves to such analyses, but my own view is that

ChApter 2

Camps, houses and ngurra

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

40/213

Camps, houses and ngurra

27

this trend relates anthropologists own inclinations. This can partly beexplained by reerence to the work o Heidegger and Bachelard, botho whom give good reasons why the Western mind (and hence, most

anthropologists) avour the house. This book is an attempt to show thatother types o dwellings, in this case the Warlpiri camp, carry as muchmeaning and in similar ways.

My second misgiving about the anthropological literature aboutdomestic space is that much o it avours structure over social practice.Most studies identiy the way in which a house represents the cosmos,or example, and pay little or no attention to the ways in which peoplelive in these dwellings. Or in regards to Heideggers series o buildingdwellingthinking, many anthropologists draw connections betweenbuilding (the physical structures) and thinking (the ways o being inand conceptualising the world), but they ignore dwelling, the ways in

which people relate to domestic space in everyday lie through theirsocial practices.

The rst anthropologist to pay serious attention to the centralityo social practice and bodily movement to the structuring processes

was Bourdieu, in his landmark essay The Kabyle House or the WorldReversed (1990, rst published in 1970). His approach generated a newtradition o anthropological analyses o social practices, emphasising socialengagement with domestic space. Two works within this tradition havebeen particularly infuential on my own methods o analysis. The rst isHenrietta Moores Space, Text, and Gender(1986). Based on her Kenyanethnography, she aims to shit the conventional ocus o deciphering themeanings encoded in space and their relations to social structure, to a

perspective ocussed on the creation and maintenance o such meaning.The question she asks is: How does the organisation o space come tohave meaning and how are those meanings maintained through socialinteraction? (Moore 1986: 74). To answer this, she approaches domesticspace as a text which is continually read and interpreted by those wholive in it and also by her as the ethnographer. This allows her toanalyse change as situated in a web o new readings o new and old

practices (rather than simply emphasising new developments, such as,in the case o her ethnography, the introduction o square rather thanround houses). Further, she examines how social practice (beyond merereadings) produces and reproduces meanings o structured space. Hermultilevelled and stimulatingly complex interpretation o domestic

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

41/213

Yuendumu Everyday

28

space is particularly relevant to the analysis o contemporary Warlpiriengagements with domestic space.

The second is Robbens analysis o the relationship between social

practice and spatial ordering in the houses o canoe shermen and boatshermen in a Brazilian town (1989). Although these canoe shermenand boat shermen live in architecturally identical houses, they read andemploy the spatiality o their houses in divergent ways, pointing towardsthe incessant appropriation o meaning through social practice:

People have to dwell in a house in order to reproduce thehabitus objectied by it. How they dwell is infuenced by their

early childhood socialization, the architectural structure o theirpresent living quarters, and the nature o their activities and socialinteraction outside the domestic world. House and society are notonly produced and reproduced in domestic and societal practicesthrough a process o structuration, but they also continuallygenerate and regenerate one another in a structurating dynamic(Robben 1989: 583).

His point is pertinent in regard to contemporary Warlpiri uses o andways o relating to domestic space. Today many Warlpiri people livein houses which architecturally are the same as houses ound through-out suburban Australia, yet Warlpiri people dwell in them in quitedierent ways than do suburban Australians. Robbens approach sug-gests how to conceptualise the meanings behind dierent practices insimilar dwellings.

Following Robbens and Moores cues, I rst examine the structural,

the spatial and some o the conceptual properties ocampsand houses,as well as their interplay at Yuendumu rom the olden daysto the present.I begin this process o untangling with a description o the structuralproperties oolden days camps,which leads to a discussion o the valuesunderpinning the Warlpiri series o buildingdwellingthinking. Icontrast this with the values inherent in the Western series and throughthis lens o values examine the introduction o housing at Yuendumuand its eect on contemporary Warlpiri practices o relating to domesticspace.

o a ca

Beore sedentisation Warlpiri people lived a highly mobile huntingand gathering liestyle, travelling across the Tanami in bands o ever-

-

7/27/2019 Yasmine Musharbash Yuendumu Everyday Contemporary Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia 2009.pdf

42/213

Camps, houses and ngurra

29

changing composition.2 Beore nightall, the people who ormed a bandat any one time arranged their sleeping quarters. While the position othese camps changed depending on where a band was at a particular

time, the shape these camps took was always the same, and highlystructured. People did not lie down at random, but every night theyreproduced the same structure, or building in Heideggers sense. This

was made up o windbreaks, rows o sleepers, and res. Figure 4 usesWarlpiri iconography to depict a typical olden days camp, and delineatesthe named spaces within it.

Yunta

In its most restricted sense, the termyuntais used to denote a windbreak(see also Keys 1999: 446; 16571). A windbreak is constructed out oleay branches, either piled on top o each other to create a low, thick