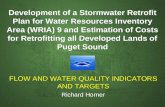

flow and water quality indicators AND TARGETS R ichard Horner

Y ICHARD “We differ · along with what really matters about domestication: the reduction of...

Transcript of Y ICHARD “We differ · along with what really matters about domestication: the reduction of...

“We differ from our ancient ancestors in ways similar to how dogs differ from wolves.

Humans: The Domesticated

PrimatesAs we became more peaceable, our bodies evolved

along the lines of other tamed animals

GET

TY IM

AG

ES

A few years ago, I stayed in Kenyawith the conservationists Karl andKathy Ammann, who kept a rescuedchimpanzee named Mzee in theirhome. Even as a young adult, Mzee

was generally well-behaved and trustworthy. Yethe could be impulsive. At one point, over break-fast, Mzee and I reached for the jug of orangejuice at the same time. He grabbed my hand asI held the jug, and he squeezed. Ouch. “Youfirst!” I squeaked. I was still rubbing my fingersback to life once he had finished his drink.

The truth is that even when chimpanzeesknow the rules perfectly well, they don’t alwaysrestrain their aggression. In the wild, their livesare full of violence. A day spent with wild chim-panzees gives you a good chance of seeingchases and hitting; every month, you are likely tosee bloody wounds. Compared with even an un-usually violent group of humans, chimpanzeesare aggressive several hundred to a thousandtimes more often over the course of a year.

The greater peaceability of human societiescomes from our nature. We can look each otherin the eye. We don’t lose our tempers easily. Wenormally control our aggressive urges. In pri-mates, one of the most potent stimuli for aggres-sion is the presence of a strange individual. Bycontrast, Jerome Kagan, a pioneer in develop-mental psychology, reports that in his hundredsof observations of two-year-olds meeting unfa-miliar children, he has never seen one strike outat the other. That willingness to interact peace-fully with others, even strangers, is inborn.

What accounts for this human difference?The answer lies in the evolutionary pressuresthat selected against aggression, particularly inmen. The cultural anthropologist ChristopherBoehm has found that, in hunter-gatherer soci-eties, a man who threatens others by having tooviolent a temper is treated in a consistent way.If the bully can’t be contained by the cajoling ef-fects of ridicule or ostracism, the other menreach a consensus, make aplan and execute him. Overthe eons, the long-termpractice of killing unrepen-tant aggressors must havefavored genes for morepeaceful behavior.

No other mammal hasthe brainpower to organizecapital punishment. Whenlanguage became suffi-ciently sophisticated, ourancestors’ ability to con-spire led not only to a morepeaceful species but also toa new kind of hierarchy. Nolonger would human groupsbe ruled by the physicalforce of an individual. Theemergence of capital pun-ishment meant that hence-forth, anyone aspiring to bean alpha couldn't get awaywith just being a fighter. Hehad to be a politician, too.

The result of genera-tions of such selective

pressure is that human beings are bestunderstood as an animal species thathas been domesticated—like dogs,horses or chickens. Recent archaeo-logical evidence suggests that humansbecame increasingly docile and lessreactively aggressive around the timeof becoming Homo sapiens, a processthat started about 300,000 years ago.

Critical clues come from compari-sons with domesticated animals. Inhis 1868 book “The Variation of Ani-mals and Plants Under Domestica-tion,” Charles Darwin reported thatthere are various surprising biologicalmarkers of the domestication process.For instance, every kind of domesti-cated nonhuman mammal includessome adults with floppy ears, whichare very rare in adult wild animals.Making matters more mysterious,there was no obvious reason why do-cility should be linked to floppy ears.It was just something that happened.Another example is white spots onforeheads, which are common inhorses, cows, dogs and cats but not inwild animals. It was the same storyfor white feet, curly tails and morethan a dozen other characteristics.

The list of traits associated with the“domestication syndrome” is useful,because it provides telling clues to thehuman past. Critically, the domestica-tion syndrome includes changes tobones. Fossil bones allow archaeolo-gists to recognize when species suchas dogs, goats and pigs became domes-ticated. As the archaeologist HelenLeach argued in an influential 2003 ar-ticle, they can do the same for humans.

Dr. Leach listed four characteristicsof the bones of domesticated animals:They mainly have smaller bodies thantheir wild ancestors; their faces tend

to be shorter and don’t project as farforward; the differences betweenmales and females are less highly de-veloped; and they tend to have smallerbrain cavities (and thus brains). As itturns out, all of these changes appearin human fossils. Even our brain sizefits the pattern: While the human braingrew steadily over the last two millionyears, that trajectory took a suddenturn about 30,000 years ago, whenbrains started to become smaller.

The differences between modernhumans and our earlier ancestors havea clear pattern: They look like the dif-ferences between a dog and a wolf.Half a million years ago, our ancestorswere heavier-bodied, with relativelybigger males, more masculine facesand bigger teeth. To extrapolate fromdomesticated animals, these character-istics indicate that our ancestors wereless docile than we are today. Pre-sapi-ens humans would have had a greaterpropensity for reactive aggression, los-ing their tempers more easily, quick tothreaten and fight one another.

A fascinating puzzle is why thesephysical changes go along with thechanges in emotion and behavior thatwe call domestication. Why should hu-mans and animals grow flatter facesas they become less aggressive?

One way of answering that ques-tion is to think about nipples. Nipplesprovide no benefit to males, yet mam-mals have maintained them since theorigin of suckling around 200 millionyears ago. That is because, in thegrowing embryo, the sequence of de-velopment responsible for female nip-ples, which are adaptive, also leads tomale nipples, which aren’t.

In the same way, the traits associ-ated with domestication—like flatterfaces and smaller brains—may not beevolutionarily adaptive in themselves.Rather, they are side effects that goalong with what really matters aboutdomestication: the reduction of ag-gression that, in animals, we calltameness. The forces that led us to be-come more peaceful with one another,over the course of thousands of gener-ations, have apparently left their markon our bodies as well as our minds.

Dr. Wrangham is the Ruth B. Moore Professor of Biological Anthropology at Harvard. This essay is adapted from his book “The Goodness Para-dox: The Strange Relationship Be-tween Virtue and Violence in Human Evolution,” which will be published by Pantheon on Jan. 29.

BY RICHARD WRANGHAM

In the wild, the lives of chimpanzees are full of violence; they are much more aggressive than humans.