Whistler Morris

-

Upload

nikolay-todorov -

Category

Documents

-

view

229 -

download

0

Transcript of Whistler Morris

8/20/2019 Whistler Morris

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/whistler-morris 1/9

Morris reply to Whistler

by E Le Mire

IN February, 1885, James McNeill Whistler recited his enO Clock lecture before a very distinguished London audienceat the very fashionable ten o clock hour. On a quiet Sundayafternoon in September, 1886, William Morris read his lectureOf the Origins of Ornamental rt to a working-class Manchesteraudience that sat attentively, bu t probably uncomfortably, instarched collars and Sunday suits. Whistler made his appearancein top hat, white gloves, cane and tails. e stood daintily toyingwith his monocle while waiting for full attention, suffered afreezing moment of stage fright, made several false starts, andfinally spoke out clearly in his characteristic piping voice. Morriswore his customary dark blue serge suit, with a lighter blue cottonshirt he had dyed himself being a natural born do-it-yourselfer). e was, as usual, without necktie. As usual, when lecturing hemopped his brow with a red bandanna held in his left hand, andread from a foolscap manuscript held in his right the same manuscript now kept in the British Museum and from which I quotethroughout). His robust voice made longer than ordinary pausesonly when he stopped to shift his weight from right to left foot,his bandanna and his manuscript exchanging positions at the sametime. the glitter and pomp of St. James s Hall, Piccadilly, wereaccurately reflected by Whistler s formal attire and manner, theplain seriousness of the ew Islington Hall, Ancoats, Manchester,was just as accurately reflected by Morris.

Hesketh Pearson says that Whistler s lecture, precisely thoughinsouciantly titled he en O Clock was as closely studied andwritten as if it had been his life s work. Certainly it was the

longest single composition the painter ever attempted. Of theOrigins of Ornamental rt was, on the other hand, only one ofthe hundred or so lectures Morris delivered on the six hundredoccasions he appeared before public audiences. Whistler publishedhis separately in 1888, included it in he Gentle r t of MakingEnemies in 1890, and listened proudly to Mallarm6 s French

3

8/20/2019 Whistler Morris

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/whistler-morris 2/9

J L ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ -:J1ir~

MtU ·t;·hz t t ~ ~ k m ~ ? ? ~~ h IWJr 7iZ ~ ~ ~~ ~ f ~ ~ ~ _

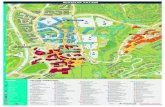

~ . 7 . Of the Origins of Ornamental Art a lecture by William Morris Firstpage of the manuscript 12 inches deep Reproduced by permission oftbe Society of Antiquaries and the Trustees of the British Museum

8/20/2019 Whistler Morris

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/whistler-morris 3/9

translation in 1892. Morris never bothered to publish his at allthough th e Manc ster Guardian no t partial to socialist lecturesprinted an almost complete report of its first delivery. couldno t find a place in the twenty four volumes of his CollectedWorks or even in the two-volume supplement. Were it not forMay Morris devoted preservation of her father s manuscriptsno full text would remain.

One might at this point marshall a host of arguments to provethat although Whistler s name was not mentioned Morris lecturewas a reply to the Ten O Clock. However that would be tobelabour the obvious; and anyone no t belonging to a very smallsection of the intellectual lunatic fringe would be tempted toask so what? anyway. The point would likely be significantonly to those presently editing Morris lectures. That party s

still definitely in the minority.It may perhaps be of more general interest and more use to

explore what Morris lecture had to say about the beginnings ofart its relation to nature and society and finally - that perennialconcern of Victorian critical theory - the artist s relation to hissociety. That Morris was here replying to Whistler should besufficiently apparent though incidental to the main concern.Loath to reawaken the armed butterfly by such disrespectremembering s one must the many less-offending corpses stungto premature death and laid ou t so precisely on the white slabsof The Gentle rt each neatly signed with that sting-tailed

insect ye t will I use the Ten O Clock only s

significantbackground. fter debunking some false prophets including his oldest

enemy Ruskin and his newest Wilde Whistler set ou t to makesome even newer enemies by conjecturing the earliest origins ofart origins just then so much in the news because of recentarchaeological discoveries. By giving life and colour to prehistoricscenes he decorated a system of aesthetic values.

In the beginning man went forth each day - some to do battle some

to th e chase; others to dig and delve in the field - all that they mightgain and live or lose and die. Until there was found among them onediffering from the rest whose pursuits attracted him not and so hestayed by the tents with the women and traced strange devices with aburnt stick on a gourd.

Depar ting from normal practice in his lecture Morris fo r the

4

8/20/2019 Whistler Morris

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/whistler-morris 4/9

first and only time conjectured art s earliest beginnings:

. . . the period is that of a state of things when society has begun whenevery man t as had to give up some of his individuality fo r the sake ofthe advancement of the whole community . . . the strong and youngfare afield to hunt or fish or herd the beasts of the community or digand sow and harvest in the strip of communal tillage while the weak

the women and the cripples stay at home to labour at the loom or thewheel or the stithy.

Above and beyond the fact the Morris h istory is based on amore careful study of contemporary historians than Whistler sthat the latter quotation is a more scholarly account of primitivesociety it is obvious that in Morris sketch artistic pursuits weremore necessary serious and reasonable. In Morris opinion artbegan with a combination of physical and psychological necessities; it was less a matter of individual choice and more a requirement of nature. The weak or crippled members of the tribe omitted the more active engagements of their fellows because theywere weak or crippled. They probably wished fo r the moreactive life from which physical debility and tribal division oflabour excluded them: Hard indeed it seems fo r them to forgothe brisk life and stir .

Whistler took an individualist s view of the artist and his relation to society whether that society be Victorian or CroMagnon:

This man wh o took no jo y in the ways of his brethren - wh o cared

not for conquest and fretted in th e field - this designer of quaintpatterns - this deviser of the beautiful wh o perceived in Nature abouthim curious curvings as faces seen in the fire - this dreamer apart wasthe first artist.

The dreamer apart created something apart from and foreign tothe world in which he lived. He was chosen by the Gods to go beyond the slovenly suggestion of Nature. The curious curvings were really the product of his ow n special gift; he saw themin nature as faces are seen in the fire they were not really there.

But fo r Morris art was an extension of the functions of nature;

its beauties were refinements of natural beauties; its subject matterand technique were deductions made by man from the naturalphenomena of his world. Morris artist practical as well as primitive vas no dreamer apart. He might dream or think as heworked at his appointed job as he contributed his share to the

. support of the community; but his dreams were the dreams that

5

8/20/2019 Whistler Morris

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/whistler-morris 5/9

all men dreamed since his interests were the interests of all men.Even the fonn that received and held his thoughts was takenfrom nature and his fellows:

The flowers of the forest glow his web and its beast move overit: his imaginings of the tales of the priests and the poets might be pictured on the dish or the po t he was fashioning; the sword hilt the roof

beam were no longer dead bronze and wood but part of his soul madealive forever.

As Morris conceived of primitive society the artist came to berecognized a truly valuable citizen: and with all this [production] he was grown to be no longer a slave of slaves but a master;a man looked upon better and more useful than the hunter orthe tiller of the soil deserving the plentiful thanks of the community. Human society in Morris survey had by this timeevolved into the epic ages and he documented the forgoing

statement with several references to early mythology andliterature. Perhaps he chose the deified craftsmen HephaestusThor and Weyland answers to Whistler who made a lowestimate of primitive popular taste. Whistler related how

. . . the toilers toiled and were athirst; and the heroes returned fromfresh victories to rejoice and to feast; and all drank alike from theartist s goblets fashioned cunningly taking no note the while of thecraftsman s pride and understanding no t his glory in his work; drinkingat the cup no t from choice not from a consciousness that it was beautiful bu t because forsooth there was none other.

For Whistler and I art pour l art which he represented ar t hadits origins outside of social conditions and was disconnectedentirely from public tastes. was an ideal a gift from the gods: the people questioned not and bad nothing to y in the matter.Departing in this from his French master Courbet Whistlerconstructed an aesthetic in which few were called and evenfewer chosen; and these few became the breed apart professionals whose work was beyond the understanding or perceptionof the common herd. In the period of Greece s greatest splendorhe said the Amateur was unknown - and the dilettanteundreamed of . Art in short was never popular. There neverwas an anistic period. There never was an Art-loving nation.

To this Morris opposed a doctrine of popular art a doctrinethat assumed the general distribution of the artistic instinct. Thisview expressed in another lecture Tbe Aims Art sees

6

8/20/2019 Whistler Morris

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/whistler-morris 6/9

the springs of art in the human mind s deathless and judgesperiods and nations with reference to the freedom they providedfor the expression of that instinct. Certainly Whistler desiredfreedom too, bu t he was concerned with the freedom of the few.Fo r him, the health of art depended only on the autonomy of theprofessionals, not on a widespread popUlar art Moreover, thefreedom Whist ler insisted on removed the artist from all publiccensure or approval, making him a law unto himself. In Whistler sview, only the artist had to be free; in Morris , the entire societyhad to be free before art could prosper.

Morris and Whistler agreed in their condemnation of the dominant trends of Victorian art, but they attacked those trends fromdifferent directions. They agreed that commercialism, the rise ofthe philistine, the triumph of cheap and nasty in Victoria s greenand pleasant land spelled the death of art, bu t they disagreed s

to how these things came about and why they were allowed

to continue. Fo r Morris (who was well-versed in the Marxianhistorical dialectic), social, political, and especially economictyranny, abridgements of the freedom of the mass of men,prevented the expression of the manlike, civilizing qualities thatwere, for him, a natural part of man s being. He argued thathuman nature always possesses the instinct for art but at specificpoints in history - under the rule of imperial Roman taxgatherers or, later, of the English Tudors, under seventeenthcentury mercantilism or nineteenth-century capitalism - tyrannysurpressed or stunted that instinct. Morris thought that Man s bynature good; he insisted that every man has within him his propercapacity fo r artistic production and appreciation. Whistler sawthe reverse of this picture; cheap and nasty was accepted and,indeed, welcomed because i t mirrored the un-artistic nature ofmost men, the nature that produced the Crystal Palace exhibits:

The taste of the tradesman supplanted the science of the artist, andwhat was born of the million went back to them, and charmed them,fo r it was af ter the ir ow n heart; and the great and small, the statesmanand the slave, took to themselves the abomination that was tendered, andpreferred it - and have lived with it ever since .And no w the heroes filled from the jugs and drank from the b o w l s -with understanding - noting the glare of their new bravery, and takingpride in its worth .

Whistler charged that ar t died when it became popular: and

7

8/20/2019 Whistler Morris

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/whistler-morris 7/9

the people - this time - had much to say in the matter - and allwere satisfied. nd Birmingham and Manchester arose in theirmight - and ar t was relegated to the curiosity shop.' Morris, onthe other hand, dated the decline of art from the time it ceasedto be popular, meaning by popular not 'mass-produced' but'commonly-produced' by a people s the expression of theirjoy in labour. While he believed that in is own day great individual artists still worked with some limited success, Morris didnot see this s redeeming nineteenth-century art. He joinedRuskin in stressing the merits of individual expression, but bothhe and Ruskin also insisted that individual expression dependedon other things: T he tones of Venice demanded a societyruled by Christian morality; Morris' lecture f tbe rigins of rnttlnental rt placed greater emphasis on social and economicreconstruction. When Morris spoke of morality, he generally

meant no more than social justice. But, fo r him s for Ruskin,individual expression required freedom of expression for themass of men.

The concept of ar t s a natural habitus of man, s indeed thatpart of his nature that is most elevated, became in Morris' lecture nearly a doctrine of an aesthetic 'noble savage.' shouldbe emphasized that Morris thought man nature artisticallygood. To rebut Whistler's charge that ' the one touch of naturethat calls aloud to the response of each . . . this one unspokensympathy that pervades humanity, is - VUlgarity ' Morris wasforced to make his most careful defence of artistic primitivism.Herein may be the lecture's greatest significance.

Drawing on his legacy of Pre-Raphaelite ideas, Morris gavethem much wider application than any of the Brethren hadbefore, integrating those ideas with what appears to be a cyclicconcept of art history. In phrases that remind the modern reader,perhaps unfortunately, of Thomas Gray s 'mute inglorious Milton,' he told his audience that

in popular ar t the expression of man's thoughts by his hand does fo r

the most par t fall far short of the thoughts themslves; and this always themore s the race is nobler and the thought more exalted

Tracing the progression ou t of this primitive state, he used anargument that, with important alterations, Holman Hunt mighthimself have used:

for a long while among Greek and kindred peoples, a rt was wholly

8

8/20/2019 Whistler Morris

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/whistler-morris 8/9

in the condition of its thought being greater than its expression. . . .then came a period [the age of Pericles perhaps] when technicalexcellence advanced with wonderful speed; the standard of excellence inexpression grew very high and the feeling of a people cultivated veryhighly within narrow limits began to forbid any attempt at expressionof thought which did not approach within limits prescribed something like perfection

he intensely Christian unt would have applied this argumentonly to the Christian painters who preceded Raphael with whomhe thought the point of highest excellence in painting wasreached. Morris broke the medieval Christian confines of thetheory giving to the Greeks the Assyrians and the Egyptianseach an ideal primitive Pre-Raphaelite period where contentheld primacy over technique.

In this same lecture Morris explored some of the implicationsof this theory. e outlined how progression out of primitivismwhere matter or thought was superior to technique resultedin an early division of the arts into fine and ornamental. Withthe division according to Morris fine ar t became aristocratic;it was practised only those few who could master its constantly increasing techmcal excellences. he aristocracy positedby Whistler s natural to ar t and the artist was in Morris viewthe product of a gradually increasing sophistication. By hardening rules for the attainment of its sophisticated ideals the artisticaristocracy came eventually to tyrannize over all the ts with

which it was directly concerned.However directly aimed at Whistler Morris lecture f theOrigins of Orncrmental r t explains bet ter than any other hisapproach to Pre-Raphaelite principles. Without referring to themovement s such he justified its attempt to avoid the tyrannyof technique. is immediately clear that he did not propose anyabandonment of technique; rather like unt and Millais beforehim he wished to eliminate the conventions of excellence imposedby an accumulated technical mastery a mastery that in thedecorative arts of his own day took the form of machine preci

sion. Both in this lecture and in the l3ter one on he EnglishPre Raphaelite School the discipline of ar t is made to rest onnature directly apprehended; this is the same discipline towardswhich Ruskin had pointed in Modern Painters and his pamphletdefence of Pre Raphaelitism. All of Morris lectures patientlyrepeat this part of the message by constantly defending the free-

9

8/20/2019 Whistler Morris

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/whistler-morris 9/9

dom from artificial conventions. But like Ruskin he wantedno repetition of pre-Renaissance ineptitudes.

The contention with Whistler pushed Morris a step beyondRuskin though. y making the Pre-Raphaelite creed explicitand widening its application between technical mastery and thetyranny of technique he gave that creed a new life. or thiswell fo r his own artistic production he was the leader of whatmight be called the second wave of Pre-Raphaelites.