Abstract€¦ · Web viewThis intervention in the foreign exchange markets is intended to create a...

Transcript of Abstract€¦ · Web viewThis intervention in the foreign exchange markets is intended to create a...

Monetary Policy and Foreign Exchange Intervention in an Emerging Market:

Empirical Evidence from Indonesia

Alexander Lubis*, Constantinos Alexiou** and Joseph G. Nellis***

Authors:

*Bank of IndonesiaJl MH Thamrin No 2, Jakarta 10350, Indonesia&Cranfield UniversitySchool of Management, Cranfield University, Bedford MK43 0AL, UKhttps://orcid.org/0000-0001-6045-7924

**(Corresponding Author) Cranfield UniversitySchool of Management, Cranfield University, Bedford MK43 0AL, UKE: [email protected] T: +044 (0) 1234 754311https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9481-3066

***Cranfield UniversitySchool of Management, Cranfield University, Bedford MK43 0AL, UK

Monetary Policy and Foreign Exchange Intervention in an Emerging Market: Empirical Evidence from Indonesia

AbstractThe use of foreign exchange intervention in an inflation-targeting framework raises a number of questions relating to its role. Given the current environment of volatile capital flows, the impact of the risk appetite of foreign investors on economic activity is worth exploring. In this direction, a Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) model is developed and effectively estimated utilizing Indonesian data. The yielding evidence suggests that foreign exchange intervention affects the macroeconomic environment through the portfolio channel. The risk appetite affects the economy by increasing the capital price whilst the foreign exchange intervention helps to stabilise the economy during the presence of risk appetite shocks and monetary policy shocks.

Keywords: monetary policy, foreign exchange intervention, DSGE

JEL Classifications: E44, E52, E58, F31

1. Introduction

Foreign exchange rate (FX) intervention has regained wide attention since the global financial

crisis, particularly in emerging markets. The massive volatility of capital flows, coming in the wake of

unconventional monetary policy in advanced countries, has provided challenges for policymakers,

who must now attempt to restrain the capital flows and prevent them from aggravating the already

heavy pressure on the exchange rate and consequent inflation, and mitigate the risk that protracted

periods of easy financing conditions will threaten the financial stability (Unsal, 2013). Many

emerging market economies depend on FX intervention to tackle this volatility (Adler et al., 2016).

Daude et al. (2016) propose that there are two underlying motives for intervening in the

exchange rate. Firstly, FX intervention addresses the perception that the current level of the exchange

rate is not at the target level. Secondly, FX intervention addresses the perception that the current level

is shifting away from the equilibrium, or to a new equilibrium, rapidly. The second motive drives

policymakers to employ FX intervention within the inflation-targeting framework to stabilise an

economy that is coming under pressure from capital flow volatility (Ghosh et al., 2016).

1

Despite the implementation of, and a host of pertinent studies on, FX intervention, the findings

in this area are still inconclusive. In addition, the study of FX intervention in emerging countries is

still inadequate, due to the unavailability of a dataset. It is essential to put FX intervention within the

framework of the central bank. However, it is still unclear whether central banks should use interest

rate policy or combine this with FX intervention to achieve their targets.

In this paper, we explore the benefits of FX intervention as an instrument in an emerging

market that implements an inflation-targeting framework. We examine this issue by building a

Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) model with a sticky price à la Calvo (1983). We

incorporate in our model the risk appetite of the investor as a shock to the economy. We then estimate

the model using data from Indonesia, one of the emerging market economies that have been affected

by the capital flow volatility. During the episode of surging capital inflows in the aftermath of

quantitative easing in the advanced economies, the exchange rate in Indonesia appreciated strongly.

The interest rate was decreased. Following the Federal Reserve's announcement that it would begin

tapering its quantitative measures, the exchange rate came under depreciation pressures. This

pressure, combined with the increase in inflation, forced the central bank of Indonesia to increase the

interest rate. During this period, FX intervention was used to complement the interest rate and

maintain stability (Warjiyo, 2014). As the biggest economy in South East Asia, Indonesia will provide

useful insight into how FX intervention is utilised to stabilise the economy. Moreover, we examine

the impact of three different policies: an interest rate policy aimed at stabilising inflation and output,

an interest rate policy aimed at stabilising inflation, output and the exchange rate, and finally, interest

rate and FX intervention used in an attempt to stabilise inflation, output and the exchange rate.

This paper makes three contributions. Firstly, it provides empirical estimations of FX

intervention based on the DSGE model in an emerging market, which features households with

limited financial access. Secondly, the model demonstrates the impact on domestic macroeconomic

stability of a change in foreign investors' risk appetite. Thirdly, we prove that FX intervention can be

utilised by policymakers to stabilise an economy during a period of capital flow shocks.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 highlights the related literature on

FX intervention, whilst section 3 presents the small open economy model. Section 4 touches on the

2

empirical estimation as well as discussing the generated evidence, and finally, section 5 provides

some concluding remarks.

2. Related Literature

The early literature on the inflation targeting framework (ITF) suggests that the exchange rate

should be allowed to float without any intervention. The central bank needs to focus on achieving its

inflation target as its overriding objective (Bernanke and Mishkin, 1997). Bernanke et al. (1999)

argue that FX intervention could confuse the public and interfere with expectations. Furthermore,

Ramakrishnan and Vamvakidis (2002) argue that using the exchange rate as an indicator of monetary

policy will decrease the significance of other indicators, such as the money supply or interest rates.

This implies that the central bank should focus on either the exchange rate or non-exchange-rate

indicators. The use of both simultaneously to anchor monetary policy will lead to a decrease in the

monetary policy’s effectiveness. Thus, Amato and Gerlach (2002) suggest that the central bank

should only consider the exchange rate as a monetary target if, and only if, the exchange rate is

deemed capable of influencing the achievement of the central bank’s inflation target.

However, Svensson (2000) argues that the exchange rate plays a significant role in the open

economy context. The real exchange rate affects aggregate demand through the price of domestic and

foreign goods in the economy, and wage setting. Moreover, the exchange rate reflects the expectation

of the forward-looking asset price. External shocks, such as foreign inflation, foreign interest rates or

the risk premium of foreign investors, will be channelled through the exchange rate.

For this reason, Calvo and Reinhart (2002) have documented the tendency of the central

banks – particularly in the emerging market countries – to quietly intervene in the exchange rate

market. These findings have refuelled the lengthy debate on the role of the exchange rate in ITF

countries, that is, its influence on the free-float regime. This intervention in the foreign exchange

markets is intended to create a more stable exchange rate (Calvo and Reinhart, 2002). In addition, by

incorporating the exchange rate into the interest rate policy rule, Svensson (2000) finds that the

inflation will be stabilised without massive volatility in the real exchange rate or other variables. On

the basis of a somewhat different approach, this view is also supported by Juhro and Mochtar (2009).

3

They explain that the exchange rate’s addition to the policy rule describes the Indonesian policy rate

better than the standard Taylor Rule. Aizenman et al. (2011) also demonstrate that central banks in

emerging markets do not follow strict inflation targeting. These central banks use interest rates as a

response to exchange rate movements more frequently, particularly those central banks that come

from commodity-based exporting economies. However, Wimanda et al. (2012) argue that the

inclusion of the exchange rate in the policy rule may worsen economic performance.

In addition, FX intervention can be implemented as a complementary policy to interest rate

policy in an ITF central bank (Ghosh et al., 2016). In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008, the

fear of floating has become a global theme for many central banks. This is partly driven by the impact

of the quantitative easing policy, conducted by most of the central banks in developed countries, such

as the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank. The excess liquidity in the global market needs to

be channelled, mainly to the emerging markets. Ghosh et al. (2016) find that the use of FX

intervention helps to achieve price stability. Blanchard et al. (2015) also find that FX intervention

helps to dampen exchange rate pressure and can be considered part of the ITF central bank's toolkit

for stabilising the macroeconomy.

The volatility of the exchange rate is also amplified by the volatility of the market

participants' risk appetite. The media terms this the 'Risk On/Risk Off' phenomenon (Smales, 2016).

Early studies, such as Henderson and Rogoff (1982), have documented that a change in the risk

appetite of the market participants may affect stability. Smales (2016) finds that this changing of risk

perception relates to large volatility in foreign exchange assets. This has been documented by

Cadarajat and Lubis (2012) who record increasing volatility in the Indonesian exchange rate after the

global financial crisis. This volatility increase was driven mainly by the off-shore market, which

represents foreign investors' risk appetite.

Early New-Keynesian DSGE models such as that proposed by Galí and Monacelli (2005)

assume that the exchange rate will be floated and that interest rate policy is the only policy used by

the central bank. Benes et al. (2014) put FX intervention into a New-Keynesian DSGE framework,

something often used by central banks. The latter authors use foreign reserves in the central bank as

an instrument of FX intervention to complement the interest rate policy. They simulate an economy

4

with fixed nominal exchange rate, either by fixing the interest rate or by performing an FX

intervention. They find that, under the pure ITF implementation, the initial level of the nominal

exchange rate is not restored. The nominal exchange rate ends up at a more depreciated level. This

depreciated level of the nominal exchange rate is not found through fixing the interest rate. This is

achieved however with the cost of consumption and inflation contraction. Another model is provided

by Alla et al. (2017), which incorporates the shocks in the international capital markets that cause

variation in the cost of capital to the economy. They show that the use of FX intervention helps to

stabilise the economy during episodes of international capital market shocks. Adler et al. (2016)

propose a model which examines the use of FX intervention under two conditions, one in which

agents perceive the use of FX intervention as an additional tool to help the policy rate achieve

inflation stability, and one in which they perceive the use of FX intervention as a tool for achieving

exchange rate stability. They suggest that FX intervention works better in an environment where

monetary policy is geared towards inflation and output stabilisation.

Empirical evidence of the effectiveness of FX intervention has been provided in a vast range

of literature. Some recent examples of these empirical studies include Berganza and Broto (2012),

Daude et al. (2016), Chang et al. (2017) and Buffie et al. (2018), who argue that FX intervention

helps improve the effectiveness of the ITF by stabilising the exchange rate, which in turn stabilises the

prices of imports. The policy is found to be more important in the context of emerging markets.

However, Kubo (2017) and Catalán-Herrera (2016) argue that FX intervention may have a small

impact on output and monetary policy. Kubo (2017) suggests that a prolonged episode of FX

intervention may have a higher cost on the economy. Drawing from these recent studies, we can see

that the discussion of the impact of FX intervention is still far from reaching a conclusion.

3. A Small Open Economy Model

We consider a continuous-time model with infinite horizon which features nominal and real rigidities

along the lines of Smets and Wouters (2007) and Christiano et al. (2005), among others. Since the

focus of this paper is on the policy of a single economy, we describe the model from the point of view

5

of one country, which we call the Home or domestic country. We will describe the problem of each of

the agents in the following sections.

3.1. Households

Following the approach of Batini et al. (2010), we set the households to consist of two types: regular

ones which pay taxes and do not face any constraints in the financial market, and credit-constrained

ones which consume purely from their wages. We create this set-up to represent the conditions of

Indonesia, which has a proportion of households that may not have access to the financial market.

According to The World Bank (2010), about 60% of the population of Indonesia has access to formal

financial services.

3.1.1. Regular (Non-Credit-Constrained) Households

There are (1− λ )regular households that have access to financial markets. These uniform households

seek to maximise the following objective function:

(1)

where C1, t+sis a consumption index for regular households, L1 ,tis leisure, which we define as

L1 ,t=1−N1 , t. N 1 ,tis the total time the regular households spend on labour (working). The parameter

β is the discount factor. We then define the consumption function as follows:

U1 ,t=U (C1 ,t , L1 ,t )=(C1 , t− χ C1 ,t−1 ) (1−η) (1−σ ) (1−N1 , t )

η (1−σ )−11−σ

(2)

The parameter η represents the Frisch elasticity of labour supply, σ represents risk aversion, and χ

represents the consumption habit formation.

The households then face a nominal budget constraint, which is given by

PtB BH, t+Pt

B∗¿ St B F,t¿ =BH ,t−1+ St B F,t−1

¿ +Pt W t (1−T tw )H 1 , t−Pt C1 , t+Γ t ¿ (3)

where W tis the pre-tax real wages, a proportional labour tax is given by T tw, and the nominal firm

profits transfer is given by Γ t . BH , tis domestic bond bought at nominal price PtBand denominated in

6

the home currency and BF ,t¿ is foreign bond bought at nominal price Pt

B∗¿¿ and denominated in foreign

currency. Stis the nominal exchange rate.

Maximising equation (1) subject to the budget constraint we have

PtB=Et [ Λt ,t+1

Π t ,t+1 ] (4)

Pt

B∗¿=Et [ Λt , t+1

Π t, t +1

S t+1

St ]¿ (5)

U L, 1 ,t

UC ,1 ,t= η

1−ηC1 , t− χ C1 ,t−1

1−N1 ,t=−W t (1−T t

w ) (6)

where Λt ,t+1 ≡U c ,1 ,t+1

U C , 1 ,t. We then define the nominal return on home bonds to be Rt=

1P t

B , where Rtis

set by the central bank. Following Adler et al. (2016) and Chang et al. (2015), we also assume that

foreign bonds are subject to a risk premium that depends on the exposure to foreign debt:

Rt¿= 1

P t

B∗¿ Θ( St ( ψB F,t¿ −(1−ψ ) BG ,t

¿ )PH ,t Y t

)¿

(7)

where BG, t¿ is the amount of government debt denominated in the foreign currency. Parameter ψ

represents the share of government and private debt. If ψ = 0.5 then government and private debt can

be substituted perfectly, and the composition of government and private debt has no real or nominal

effects. If ψ > 0.5 then the market perceives government debt to be less risky than private debt and if

ψ < 0.5 it is the other way around.

The endogenous risk premium Θ induces imperfect asset substitutability between domestic

and foreign bonds, which allows the FX intervention to have real effects in the economy. Next, we

rewrite equation (4) as

1=E t[ Λ t , t+1

Π t ,t+1 ]R t (8)

7

We define Π t ,t+1=P t+1

Pt and Π t ,t+1

¿ =P t+1

¿

Pt¿ as the home and foreign CPI inflation rates and

Π t ,t+1S =

S t+1

St as the rate of change of the nominal exchange rate1. We can then rewrite equation (5) as

1=R t¿Θ( St BF, t

¿

PH ,t Y t )Et[ Λ t , t+1

Π t , t+1Π t ,t+1] (9)

Equations (8) and (9) also represent the uncovered interest rate parity (UIP) condition.

3.1.2. Credit-constrained Households

There are λ credit-constrained households that have to consume out of their wage income.

Their consumption can be written as follows:

C2 ,t=W t (1−T tW )N 2 ,t (10)

These credit-constrained consumers need to choose C2 ,t and L2 ,t=1−N2 , t, to maximise their

utility function, which is the same to equation (1), subject to equation (10). The first-order conditions

are now the same for both types of households:

U L, 2 ,t

UC ,2 ,t= η

1−ηC2 , t− χ C2 ,t−1

1−N2 ,t=−W t (1−T t

w ) (11)

3.1.3. Aggregate Consumption and Labour Supply

Summing the regular and credit-constrained households, we write the total consumption and labour

supply as follows:

C t= λ C2 ,t +(1−λ )C1 ,t (12)

N t=λ N2 ,t +(1−λ ) N1 , t (13)

3.1.4. Consumption Demand

The consumption of both households consists of domestic and foreign goods (imports), which form a

composite index of

1 Since the currency of an emerging market country is usually the term currency, we interpret a positive Π S as the depreciation rate and a negative one as the appreciation rate.

8

C t=[γ C

1μC CH ,t

μC−1μC + (1−γC )

1μC CF ,t

μC−1μC ]

μC

1− μC (14)

with CH ,t and CF ,t representing the consumption of home and foreign goods respectively. γC

represents the share of domestic goods within the economy, which is also known as the 'home bias'.

The parameter μC represents the elasticity of substitution between domestic goods and imported

goods.

Here we assume that the price of imported goods will be directly passed on to the price

domestically. This view is supported empirically by Rahadyan and Lubis (2018). They argue that,

even though the level of nominal exchange rate pass-through may not have transmitted directly to

inflation, the volatility of the nominal exchange rate amplifies the effect of the pass-through.

Therefore, we may assume that the nominal exchange rate has a perfect pass-through to the inflation.

The corresponding price index is denoted by

Pt=[ γC PH , t1−μC+(1−γ C ) PF , t

1− μC ]1

1−μC (15)

where PH ,t and PF,t are the prices of domestic goods and imported goods in the home country

respectively.

Maximising total consumption in (14) subject to a given aggregate expenditure of

Pt C t=PH ,t CH , t+PF,t CF ,t results in

CH ,t=γC( PH, t

Pt)−μC

C t (16)

CF ,t=(1−γ ¿¿C)(PF ,t

Pt)−μC

C t ¿ (17)

3.2. Firms

Firms consist of the wholesale sector, retail, and capital producers. Wages are taxed at the

proportional rate ofT W . We follow Galí and Monacelli (2005) in assuming that the price-setting

behaviour of firms follows Calvo pricing and the Law of One Price holds.

9

3.2.1. Wholesale Sector

First, we define the production technology, which follows the Cobb-Douglas function as follows:

Y tW =F ( At ,N t , K t−1 )=( A t N t

α ) K t−11−α (18)

where Y tW is the output of the wholesale sector, At is the total factor productivity, N t is the labour

input and K t is the capital input. The wholesale firms sell goods to the retailers at a nominal price of

PtW . The wholesale profit maximisation is written as

FN ,t=αY t

N t

PtW

Pt=W t (19)

FK ,t=(1−α )Y t

K t−1

PtW

Pt=r t

K (20)

where Pt is the price index of final consumption goods.

3.2.2. Retail Sector

There is a continuum of retailers indexed by j∈ ( 0,1 ) which convert goods they purchase from the

wholesale sector, producing a differentiated output Y t ( j ) and selling it at price PH ,t. The final good is

a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) aggregate of a continuum of intermediaries:

Y t ( j )=(∫0

1

Y t ( j )ϵ−1

ϵ dj)ϵ

ϵ−1 (21)

The profit maximisation problem for this type of firm is

maxY t ( j)

PH ,t(∫0

1

Y t ( j )ϵ−1

ϵ dj)ϵ

ϵ−1(∫0

1

PH , t ( j )Y t ( j ) dj) (22)

where ϵ is the elasticity of substitution.

These goods are bundled into final goods and lead to total demand for home good j given

by

Y t ( j )=( PH ,t ( j )PH ,t

)−ϵ

Y t (23)

where we can define the aggregate price index of home-produced goods as follows:

10

PH ,t=[∫01

PH , t ( j )1−ϵ ]1

1−ϵ(24)

Every period, each firm faces a fixed probability 1−ϕ that it will be able to update its

prices. Denoting the optimal price at time t for home good j as PH ,t¿ ( j ), the firms are allowed to re-

optimise prices and maximise expected discounted profits by solving

maxP H ,t

¿ ( j)E∑

s=0

∞

ϕk Λ t , t+ k

PH ,t+ kY t+k ( j ) [ PH ,t

¿ ( j )−Pt+kW ] (25)

Substituting in the demand Y from equation (23), then taking the first-order conditions with respect to

the new price and rearranging, leads to

PH ,t¿ = ϵ

ϵ−1

E∑k=0

∞

ϕk Λt ,t+k

PH ,t+k( PH ,t+k )ϵ Y t+k Pt+ k

W

E∑k=0

∞ Λ t ,t+ k

PH ,t+k( PH ,t+ k) Y t+k

(26)

We then drop the index j because all firms face the same marginal cost and update to the same reset

price. Hence, the right-hand side of the equation is independent of firm size or price history. The real

marginal cost is defined by MC t=Pt

W

PH ,t, and we also introduce k periods of price inflation as follows:

Π H ,t , t+k=PH , t+ k

PH ,t=

PH ,t+1

PH , t

PH ,t+2

PH ,t+1⋯

PH, t+k

PH ,t +k −1(27)

Now we rewrite equation (26) as

PH ,t¿

PH ,t= ϵ

ϵ−1

E∑k=0

∞

ϕk Λ t , t+ k ( Π H ,t ,t+k )ϕ Y t+k MC t+k

E∑k=0

∞

ϕk Λt ,t+k ( ΠH , t ,t+k )ϕ ( ΠH , t ,t+ k)−1Y t+k

(28)

We introduce a mark-up shock MS t to the real marginal cost MC t and write the expression

(28) more compactly by denoting the numerator and denominator as X1 , t and X2 , t respectively. Write

the result in recursive form gives

11

PH ,t¿

PH ,t=

X1 ,t

X2 ,t(29)

where

X1 , t−ϕβ E t [ Π t+1ϵ ]= 1

1−1ϵ

Y t+k U C ,t MC t+k MS t (30)

X2 , t−ϕβ E t [ Π t +1ϵ−1 ]=Y t+k UC , t (31)

Using the aggregate producer price index PH ,t and the fact that all resetting firms will

choose the same price, by the Law of Large Numbers we can find the evolution of the price index as

given by

PH ,t1−ϵ=ϕ PH , t−1

1−ϵ +(1−ϕ ) PH ,t¿ 1−ϵ (32)

which can be written in the following form:

1=ϕ ( Π H ,t −1, t )ϵ−1+(1−ϕ )(PH ,t

¿

PH ,t)

1−ϵ

(33)

Using the demand of output, we can then write the price dispersion that gives the average

loss in output as

Δt=1J ∑j=1

J

( Pi ,t ( j )Pi , t

)−ϵ

(34)

for non-optimising firms j=1 ,⋯ , J . It is not possible to track all P j ,t but, as it is known that a

proportion 1−ϕ of firms will optimise prices in period t , and from the Law of Large Numbers that

the distribution of non-optimised prices will be the same as the overall distribution, price dispersion

can be written as a law of motion:

Δi ,t=ϕ ΠH , t−1 ,tϵ Δt−1+(1−ϕ )( X1 ,t

X2 ,t)−ϵ

(35)

Using this, aggregate final output is given as a proportion of the intermediate output:

Y t=Y t

W

Δt(36)

12

3.2.3. Capital Producers

Capital producers purchase investment goods from home and foreign firms at real price P t

I

Pt

,

selling at real price Qt to maximise the expected discounted profits:

E∑k=0

∞

Λ t ,t+ k [Qt ,t+k (1−S ( I t+k

I t+k−1))I t+k−

PtI

PtI t+ k ] (37)

where total capital accumulates according to

K t=(1−δ ) K t−1+(1−S ( X t ))I t (38)

The first-order condition yields

Qt (1−S ( X t )−X t S ' ( X t ))+Et [Λ t ,t+1 Qt , t+1 S ' ( X t+1 )I t+1

2

I t2 ]=P t

I

Pt(39)

where we define

S ( X t )≡ ϕ x ( X t−X )2 (40)

The relative price of capital Qt will equal P t

I

Pt

. Finally, we define RtKas the gross real return of

capital, given by

RtK=

(1−α )Y t

W

K t−1

P tW

Pt(1−T t

K )+ (1−δ )Qt

Qt−1

(41)

where T tK is a tax on corporate profits, which we assume to be exogenous in this model.

3.2.4. Investment Demand

Parallel to the consumer goods, the domestic, export and import demand for investment goods

will have the same conditions. We express the aggregate price of investment goods as PtI. The

investment demand is satisfied by domestic and foreign good (imports), maximising

I t=[γ I

1μI I H, t

μ I−1μI +(1−γ I )

1μ I IF , t

μI−1μI ]

μ I

1−μI (42)

13

with I H ,t and I F ,t representing the investment using home and foreign goods respectively. γ I

represents the share of domestic goods used for investment in the economy. The parameter μ I

represents the elasticity of substitution between domestic and imported goods. The corresponding

price index is denoted by

PtI=[ γ I PH ,t

I 1−μI+ (1−γ I ) PF, tI 1−μ I ]

11−μI (43)

where PH ,tI and PF,t

I are the prices of domestic and imported goods in the home country respectively.

Maximising total investment in equation (42) subject to a given aggregate investment of

Pt I t=PH ,tI I H , t+PF, t

I I F,t results in

I H ,t=γ I (PH ,tI

Pt)−μI

I t (44)

I F ,t=(1−γ I )( PF ,tI

P t)−μI

It (45)

3.3. External Demand

As in the standard literature on small open economies, we take the foreign aggregate consumption and

investment, denoted by C t¿ and I t

¿ respectively, as exogenous. The exogenous approach is taken

because we focus on emerging markets, which have the same features as the small open economy. We

formulate the foreign demand for exported consumer goods as follows:

CH ,t¿ =(1−γ C

¿ )( PH , t¿

Pt¿ )

−μC¿

Ct¿ (46)

We define the real exchange rate of consumption goods as the relative aggregate consumption

price st ≡Pt

¿ St

Pt. We then rewrite the demand for exports as

CH ,t¿ =(1−γ C

¿ )( PH, t¿

Pt¿s t )

−μC¿

C t¿ (47)

where PH ,t¿ and Pt

¿ indicate the price of domestic goods and foreign aggregate consumption in the

foreign currency. In addition, we assume that the Law of One Price for differentiated goods in the

14

traded sector holds. Therefore, the exchange rate will have perfect pass-through to export prices and

the price of consumption goods will be Pt=S t PH, t¿ . Similarly, we assume that the home country has a

perfect exchange rate pass-through for imports, which implies Pt¿=PF ,t

¿ , St Pt¿=PF ,t , and thus

st=PF ,t

Pt. We then write

CH ,t¿ =(1−γC

¿ )( 1TOT t

)−μC

¿

(48)

where ToT t ≡PF ,t

PH, t are the terms of trade.

We formulate the foreign demand for exported investment goods as follows:

I H ,t¿ =(1−γ I

¿)¿¿ (49)

We define the real exchange rate for investment as the relative aggregate investment price

stI ≡

PtI∗¿ St

PtI ¿. Then, we adjust the demand for exported investment goods to be

I H ,t¿ =(1−γ I

¿)¿¿ (50)

where PH ,tI∗¿¿ and Pt

I∗¿¿ indicate the prices of domestic goods and foreign aggregate investment in the

foreign currency. As with consumption, we assume that the Law of One Price for differentiated goods

holds for investment goods. Therefore, the price of investment goods will be PtI∗¿= St P H ,t

I∗¿¿ ¿. We also

assume that the home country has a perfect exchange rate pass-through for imports, which implies

PtI∗¿=PF ,t

I∗¿¿ ¿, St PtI∗¿=PF ,t

I ¿, and thus st=PF ,t

I

P tI . We then write

I H ,t¿ =(1−γ I

¿) ( 1TOT t )

−μ I¿

(51)

Therefore, the total exports are given by

EX t=CH ,t¿ + I H, t

¿ (52)

3.4. Market Clearing, Fiscal and Monetary Policy

A resource constraint implies the following:

15

Y t=CH ,t +CH ,t¿ + I H ,t+ I H , t

¿ +Gt (53)

where Gt is the government spending.

For our policy setting, we consider exogenous distortionary tax rates on wage and capital

income to pay for exogenous government spending, with a government balanced budget constraint.

We also allow the government to run a fiscal deficit, use government spending as a stabilisation

instrument and borrow from domestic and foreign investors.

We assume foreign bonds are subject to a premium that depends on the exposure to total

foreign debt, as we have already defined in equation (7), where BG, t¿ is the amount of government debt

denominated in the foreign currency. We assume Θ (0 )=0 and Θ'<0 and the following functional

form with these properties:

Θ ( x )=exp (−ΘB x ) ;ΘB>0 (54)

Following Farhi and Werning (2014) and Alla et al. (2017), we contribute by introducing an

exogenous risk-appetite shock (Ξ t) in order to determine the impact of the ‘Risk On/Risk Off’

phenomenon of the global financial system. This phenomenon affects emerging markets, particularly

since the global financial crisis. Equation (7) can be rewritten as

Rt¿= 1

P t

B∗¿ Θ( St (w t BF ,t¿ −(1−wt ) BG ,t

¿ )P H , t Y t

)+Ξ t

¿(55)

Furthermore, government borrowing is the combination of nominal domestic bonds BH , t held

by foreign investors. The total stock of government bonds held in home country consumption units is

defined as

BG , t=BH , t

Pt+

St BH ,t¿

P t=BGH ,t +BGF ,t (56)

Foreign bond holdings are the sum of assets held by households BF ,t and liabilities held by

the government BG, t¿ , and evolve according to

PtB∗¿ (St ( B F,t

¿ −B G ,t¿ ) )=St ( BF ,t−1

¿ −BG ,t−1¿ )−Pt TBt ¿ (57)

16

where the nominal trade balance is the difference between domestic output and private and public

consumption and investment, which can be written as

Pt TBt=PH , t Y t−P t Ct−P I ,t I t−PH ,t Gt (58)

.

We then define BF ,t ≡St BF, t

¿

Pt to be the stock of foreign bonds held by households, in home

country consumption units. Therefore,

Pt

B∗¿ Pt ( BF, t−BGF ,t)=St

S t−1Pt−1(B F,t−1

¿ −BG ,t −1¿ )+Pt TBt⇒¿

Pt

B∗¿ ( BF ,t−BGF ,t )=Π t−1, t

S

Π t−1, t( BF ,t−B GF,t )+TB t ¿

(59)

Then, by analogy with the national budget constraint given in equation (53), the government

budget constraint is

PtB BGH ,t+P t

B∗¿ BGF ,t=1

Π t−1 , tBGH ,t −1+

Π t−1, tS

Π t−1, tBGF,t −1 +D t ¿ (60)

where the nominal government deficit is given by:

Pt D, t=PH ,t Gt−W t N t T tW−(1−α )Y t

W PH ,t MC t T tK (61)

Bond price will be written as:

Pt

B∗¿ ( BF ,t−BGF ,t )=Π t−1, t

S

Π t−1, tBGF,t−1 ( BF ,t−BGF ,t )+TBt ¿ (62)

Therefore, government bond price will be:

PtB BGH ,t+P t

B∗¿ BGF ,t=1

Π t−1 , tBGH,t +

Π t−1 , tS

Π t−1 , tBGF ,t−1+Dt ¿ (63)

Fiscal policy tax rates T tW is given by:

T tW=

PH ,t

PtGt−Dt− (1−α )Y t

W PH ,t MC t T tK

W t N t

(64)

We then define FX intervention as:

17

FX t=BGH ,t

BG,t(65)

The nominal interest rate Rt is the monetary policy variable, given by a standard Taylor-type

rule (Taylor, 1993). Beside the standard inflation and output deviation response, we add an exchange

rate depreciation term following Juhro and Mochtar (2009) and Kolasa and Lombardo (2014):

log( Rt

R )=ρR log( Rt−1

R )+(1−ρR )(θπ log( Π t−1 ,t

Π )+θy log(Y t

Y )+θs log( Π t −1 ,tS

Π S ))+ϵ M ,t (66)

This fiscal stabilisation also follows a Taylor-type rule as follows:

log(Gt

G )=ρG log( Gt−1

G )+(1−ρG )(θBG , Π log ( BG,t−1 ,t

BG )+θG, π log( Π t−1, t

Π )+θG, y log (Y t

Y ))+ϵ G,t(67)

Finally, FX t is set at FX t>0 in the steady state. Then, FX t responds to changes in the

exchange rate depreciation rate Π tS and to Rt

¿ as follows:

log( FX t

FX )=ρFX log( FX t−1

FX )+(1−ρFX )(θFX ,Π S log( Π t−1 ,tS

Π S )+θFX , R¿ log( R t−1 ,t¿

R¿ ))+ϵFX ,t (68)

3.5. Shock Processes

The structural shock processes in log-linearized form are assumed to follow AR(1):

log At−log A=ρA ( log At−1−log A )+ϵ A,t (69)

log Gt−log G=ρG ( logGt−1−logG )+ϵG ,t (70)

log MS t−log MS=ρMS ( log MS t−1−log MS )+ϵ MS ,t (71)

log C t¿−logC ¿=ρC¿ ( logC t

¿−log C¿ )+ϵC¿ ,t (72)

log I t¿−log I ¿=ρ I ¿ ( log I t

¿−log I ¿ )+ϵ I ¿ ,t (73)

log Π t¿−log Π ¿=ρΠ ¿ (log Π t

¿−log Π ¿)+ϵΠ ¿ ,t (74)

Variables without subscription denote the steady state value of the variable.

18

4. Empirical Analysis and Results

This section provides a detailed elaboration on the sample used and the estimation techniques i.e. the

Bayesian estimation procedure, the data and priors used in the estimation, a selection of the resulting

impulse responses, and the variance decomposition.

4.1. Data

Having constructed our model, we use Bayesian techniques to estimate the parameters. We employ

quarterly data for Indonesia from the period 2000Q1 to 2018Q1. We use output growth, consumption

growth, investment growth, and domestic inflation, which are taken from Indonesian Statistics (BPS).

We obtain the policy rate and exchange rate growth from the central bank (Bank Indonesia) and the

terms of trade growth from Thomson Reuters.

The output, consumption and investment are in real terms, while the policy rate and exchange

rate are in nominal terms. The exchange rate used is USD/IDR. Domestic inflation is calculated using

the CPI with 2012 as the base year. Terms of trade are calculated using the index of export prices and

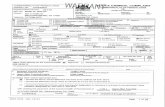

import prices constructed by Thomson Reuters. Figure 1 illustrates the historical and smoothed

variables.

19

Figure 1 Historical and Smoothed Variables

We construct measurement equations to incorporate the measurement error in our observable

variables. Table 1 describes our measurement approach.

Table 1 Measurement Equations

Observable Model VariablesOutput growth Δ lnY obs, t=Δ (ln Y t−ln Y )+ϵY , t

Consumption growth Δ lnCobs ,t=Δ ( ln Ct−ln C )+ϵ C ,t

Investment growth Δ ln I obs ,t=Δ ( ln I t−ln I )+ϵ I ,t

CPI inflation Π obs ,t=Π t−ΠInterest rate Robs ,t=Rt−RChange in the exchange rate Π obs ,t

S =Π tS−ΠS

Terms of trade growth Δ lnToT obs, t=Δ (ln ToT t−ln ToT )+ϵ ToT ,t

20

4.2. Parameter Calibration

To estimate the model, we calibrate some parameters according to previous studies and to be

consistent with the mean values in the data. The discount factor β is set to 0.99, which gives an annual

steady-state real interest rate of around 4% which is in line with many other studies (e.g. Smets and

Wouters (2007)). The home bias parameter γC is set to 0.62 and labour share α is set to 0.46 according

to Harmanta et al. (2014). We take the annual labour work data for Indonesia from Feenstra et al.

(2015) and calibrate the inverse Frisch elasticity of labour to be 0.25. Following Schmitt-Grohé and

Uribe (2003), we set the elasticity of the risk premium to the level of debt, ΘB, to 0.001. We also take

into account data from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), which reports on the bond market in

Indonesia2. We then calibrate the share of government bonds ψ to 0.9, to reflect the average share of

government bonds in the market. Table 2 lists the parameters’ calibrated values.

Table 2 Calibrated Parameter Values

Parameter Symbol ValuesLabour share in production function α 0.46Domestic household discount factor β 0.99Home bias parameter for consumer goods γC 0.62Home bias parameter for investment goods γ I 0.62Inverse Frisch elasticity of labour η 0.25The elasticity of substitution between domestic and imported consumer goods μC 1.5The elasticity of substitution between domestic and imported investment goods

μ I 1.5

Depreciation rate of capital δ 0.025Government bond share ψ 0.9Risk premium ΘB 0.001

4.3. Analysis of Results

We estimate the posterior distribution by numerically maximising the log posterior density

function, a combination of prior information and the likelihood of the data. Then, we estimate the full

posterior distribution using the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm. In this section we elaborate our

findings along with some selected impulse response analysis. We begin with our prior and posterior

results, which are displayed in Table 3.

2 Data can be downloaded from https://asianbondsonline.adb.org/data-portal/

21

Table 3 Estimation Results

Parameter Symbol

Prior Mea

n

Post Mean

90% HPD Interval Prior Pstde

v

Persistence of total factor productivity shock ρA 0.5 0.2820.131

4 0.417 beta 0.2

Persistence of monetary policy shock ρm 0.50.597

50.142

60.887

3 beta 0.2

Persistence of mark-up shock ρMS 0.50.488

10.161

10.757

7 beta 0.2

Persistence of government spending shock ρG 0.50.470

60.179

3 0.8 beta 0.2

Persistence of foreign consumption shock ρC¿ 0.50.468

40.172

60.767

8 beta 0.2

Persistence of foreign investment shock ρ I ¿ 0.50.536

70.251

40.843

2 beta 0.2

Persistence of foreign interest rate shock ρR¿ 0.750.754

10.516

4 1 beta 0.2

Persistence of FX intervention shock ρFX 0.50.854

10.785

90.924

3 beta 0.2

Persistence of foreign inflation shock ρΠ ¿ 0.50.136

90.054

30.213

6 beta 0.2

Share of credit-constrained households λ 0.50.410

20.339

20.478

8 norm 0.05

Internal habit formation χ 0.60.964

60.934

3 0.998 beta 0.2

Calvo parameter ϕ 0.50.381

40.222

4 0.558 beta 0.2

Risk premium in investment ΘI 44.262

73.594

15.146

1 norm 1.5

Labour share in production function α 0.540.559

60.482

10.635

4 norm 0.05

Elasticity of substitution among goods ϵ 76.735

26.185

27.159

2 norm 1.5

Risk premium of bonds ΘB 0.0010.116

60.078

20.155

9 norm 1.5

Risk aversion of households σ 21.991

31.907

22.072

2 norm 0.05

Interest rate smoothing ρr 0.70.930

30.913

30.948

7 beta 0.1

Inflation weight parameter θπ 21.909

4 1.4982.342

6 norm 0.25

Output weight parameter θY 0.10.112

90.037

70.184

6 norm 0.05

Government spending weight parameter θG 0.10.125

10.071

70.174

7 norm 0.05

Foreign inflation weight parameter θFX , Π S 0.1 0.104 0.0220.185

1 norm 0.05

Foreign interest rate weight parameter θFX , R¿ 0.10.100

80.018

20.182

4 norm 0.05

Feedback from exchange rate depreciation θs 0.10.011

10.003

50.018

7 norm 0.05

Our results shown in Table 3 indicate that the persistence of FX intervention is relatively

high, with a posterior mean value of 0.88 compared to our first prior mean of 0.5. This finding

22

confirms the tendency of the central bank to intervene in the exchange rate, as stated in Calvo and

Reinhart (2002). Moreover, the feedback of the exchange rate into the interest rate policy rule is found

to be low. We interpret this as implying that the policy rate may be targeted to address inflation, as

Bank Indonesia is an inflation-targeting central bank. Besides this, Table 3 indicates that the mean

value of the posterior inflation weight parameter in the Taylor rule is 1.9094, which is in line with

Harmanta et al. (2014). We also find that the share of credit-constrained households is 0.4102 or 41%

of all households. This number is slightly above the figure in the Indonesian Financial Services

Authority (OJK)'s report, which stated that the percentage of households lacking access to financial

services was 33% in 2017 (OJK, 2017), but is similar to that in the World Bank's report of 40% (The

World Bank, 2010).

4.3.1. Impulse Response Analysis

Another necessary piece of analysis is impulse response analysis, which explains the transmission

mechanism in the model. We focus our discussion on describing the impact of the monetary policy

shock, the FX intervention shock and the risk premium shock. The impact of the monetary policy

shock is displayed in Figure 2.

23

Figure 2 Impulse Response to Monetary Policy Shock

Note: ToT: Terms of Trade

Here we interpret monetary policy shock as the surprising positive shock to the interest rate

which is taken by the authority. Figure 2 shows that the monetary policy shock affects all the

observable variables. Nominal interest rate increases as a result of the positive shock and subsequently

the exchange rate appreciates, given the foreign interest rate remains the same, because the UIP holds.

Consequently, the terms of trade (ToT) is declining. As the cost of fund increases, the household

adjusts its consumption downward hence causing inflation to dwindle. As consumption goes down,

investment and output also decrease. However, the appreciation of the exchange rate drives the import

goods to become cheaper which brings the consumption back to the steady-state in the second round.

When imports increase and the economy demands more foreign assets (or foreign currency), without

FX intervention, nominal exchange rate adjusts to the steady-state. As the nominal interest rate

decreases investment starts to go up and subsequently the output is back to its steady-state.

24

Figure 3 Impulse Response to FX Intervention Shock

During an episode of positive FX Intervention shock, Figure 3 indicates that the positive FX

intervention causes the exchange rate to depreciate and the ToT to increase. As a result, the output and

consumption increase at the time of the shock. However, sudden upsurge in consumption and output

causes the inflation to move up and interest rate to follow in the same fashion. Subsequently,

investment goes down as the cost of borrowing increases. Following the increased of inflation, output

and consumption are contracted below their steady-state value. As the nominal interest rate increases,

the exchange rate appreciates given the UIP holds and investment starts to increase as a result. The

appreciation of the exchange rate also alleviates the pressure on domestic inflation as the price of the

imported goods becomes cheaper. The reduction of inflation drives consumption up with output

moving in the same direction.

25

Figure 4 Impulse Response to Risk Appetite Shock

Here we model risk appetite as an addition to the risk premium. Figure 4 reveals the impact of

the risk appetite shock on the observed variables. As the risk premium increases, the nominal interest

rate is also increasing. The upward movement of the domestic interest rate causes the exchange rate to

appreciate and the inflation increases. However, the increase in the interest rate drives investment

down. As both the inflation and the interest rate increase, households adjust their consumption and

drives output down. In addition, the exchange rate is also appreciating following the increased

domestic interest rate. The appreciation of the exchange rate causes imported goods to become

cheaper whilst the adjustment in consumption along with the appreciating exchange rate alleviates

inflation pressures. As a result, inflation and interest rate go down, whilst consumption, investment

and output increase.

4.3.2. Variance Decomposition

We also examine the variance decomposition of the observed variables, portrayed in Figures

5 and 6.

26

Figure 5 Variance Decomposition (1)Output Consumption

Investment Inflation

Contrary to Kubo (2017), Figure 5 shows that FX intervention may affect real variables such

as output, consumption, investment and inflation. Figure 5 displays that technology shock (eps_a),

similar to the standard New-Keynesian DSGE model, and FX intervention (eps_fx) are the

dominating shocks that affect the output. We may observe the presence of error measurements in

output (mes_y) in certain periods. Other effects are relatively small compare to the technology shock

and FX intervention shock. A similar situation can also be observed in consumption investment and

inflation. Technology shock and FX intervention are the major factors in affecting consumption,

investment and inflation.

27

Figure 6 Variance Decomposition (2)Interest Rate Exchange Rate

Terms of Trade

Figure 6 confirms that the effect of FX intervention comes through the interest rate and the

exchange rate and finally the ToT. FX Intervention (eps_fx) and technology shock (eps_a) affect the

interest rate. Since we set the Taylor rule that responds to the exchange rate, the foreign inflation

shock (eps_pi_star) also has a strong presence in the interest rate. As previously mentioned, the

exchange rate is affected by the FX Intervention directly. Moreover, foreign inflation has also affected

the exchange rate strongly. FX intervention affects inflation by lowering the import price through the

perfect exchange rate pass-through to inflation. Figure 6 also shows that ToT is affected by

technology shock (eps_a) and FX Intervention (eps_fx).

4.4. Model Comparison

In order to gain more insight into how FX intervention to the economy, we compare our model

without the presence of the intervention. We construct two modified models to compare with our

existing model. First, we take the same model and experiment with the monetary policy that only the

28

interest rule presence or the full-pledge ITF. Second, we also modified the same model by

incorporating the exchange depreciation to the Taylor rule. This the case of flexible ITF as suggested

by Kolasa and Lombardo (2014) and Juhro and Mochtar (2009). The rest of the equations will be

similar to our FX intervention model. We then take these two models and compare the results with the

FX intervention model results. The impulse response of some selected variables is presented in Figure

7, 8 and 9. We focus our analysis on the impact of these selected variables on the technology,

monetary policy, and risk appetite shocks to observe different implications of these policy options to

these specific variables.

Figure 7 Comparison of Impulse Responses to Total Factor Productivity Shock

Figure 7 shows that the selected variables are more volatile in the presence of FX

intervention. Unlike in Wimanda et al. (2012), our results indicate that monetary policy that

incorporates the exchange rate depreciation in the Taylor rule displays more stable variables in the

presence of a Total Factor Productivity (TFP) shock. Meanwhile, the FX intervention amplifies the

risk perception and expectation during the TFP shock. A keen appreciation in the exchange rate leads

to a lower price in the midst of a low interest rate period.

29

Figure 8 Comparison of Impulse Responses to Monetary Policy Shock

A strict Taylor rule has a tremendous impact on the presence of a positive monetary policy

shock as shown in Figure 8. The nominal exchange rate, particularly, appreciates as much as

expected. A similar impact can be seen for the other variables. Without the presence of the exogenous

risk appetite, the monetary policy is sufficient to influence all the variables.

Figure 9 Comparison of Impulse Responses to Risk Appetite Shock

In the presence of a risk appetite shock, the selected variables fluctuate quite a lot under the

strict Taylor-rule policy regime, as displayed in Figure 9. FX intervention helps to stabilise the

30

variables during this shock, particularly the exchange rate. This, in turn, helps to stabilise the inflation

rate and the output growth.

4.5. Policy Implications

The findings generated in this study may have several implications for the central bank. Our

estimations suggest that FX intervention helps to stabilise the economy during an episode of capital

flows. In particular, without the FX intervention, the central bank has to increase the policy rate to

contain the impact of the risk appetite shocks. Otherwise, the central bank needs to allow the nominal

exchange rate to appreciate (in the case of capital inflows) or to depreciate (in the case of capital

outflows) rapidly (Ghosh et al., 2016). Using the interest rate as the only instrument is demonstrated

to be costlier to the economy, in our findings. This FX intervention, however, needs to take into

account the availability of the foreign reserves of a country. An FX sale intervention requires

sufficient foreign reserves and an FX buy intervention will increase the foreign reserves. Investigating

the adequate amount of foreign reserves is beyond the scope of this research.

In addition, our findings highlight that FX intervention is not a generic solution for every shock

in the economy. For instance, during an episode of positive productivity shock, the use of both

interest rate and FX intervention will amplify the shock to the economy. By reducing the cost of

borrowing through both the interest rate and the exchange rate policymakers will aggravate the

optimistic view of the agent, which will in turn intensify the impact of the shock on the economy. Our

model comparison indicates that a Taylor rule that increases with the exchange rate depreciation

response is the best policy option to stabilise the economy. This paper supports Juhro and Mochtar

(2009) in suggesting that a policy rule in Indonesia needs to incorporate the exchange rate.

One other point that needs to be stressed is that the use of FX intervention should not

undermine the commitment of the central bank to achieve a pre-set target for inflation. An inflation-

targeting central bank, within its communication strategy framework, needs to communicate clearly

its strategy with regard to the intentions of the FX intervention, which is to tackle specific shocks, in

particular the capital flow shocks (Ghosh et al., 2016).

31

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the use of FX intervention by building a DSGE

model and producing estimates based on Indonesian data. We find that the central bank actively

intervenes in the exchange rate. The FX intervention affects the macroeconomic variables through the

portfolio channel. The risk appetite also affects the economy by increasing the capital price.

To have a better understanding of the use of FX intervention, we also compare the estimation

results with a policy simulation based on two conditions: an interest rate policy which strictly follows

the Taylor rule and an interest rate policy that addresses inflation, output and the exchange rate. We

find that the FX intervention helps to stabilise the economy during the presence of risk appetite

shocks and monetary policy shocks. However, the interest rate policy that addresses the exchange rate

as well as following the standard Taylor rule is found to be more effective in stabilising the

macroeconomy during TFP shocks.

These findings have a direct implication for policymakers. Our results suggest that FX

intervention can be used to complement interest rate policy, particularly in tackling external shocks

such as risk appetite shocks. However, policymakers need to be cautious in identifying shocks so as to

provide the right policy mix to tackle the issue. We simulate the economy under three different

shocks, a positive productivity shock, monetary policy shock and risk appetite shock, and our findings

indicate that FX intervention may not be the best complement for handling positive productivity

shocks to the economy.

Although this study provides interesting findings, it also leaves avenues for future research.

First, it would be interesting to incorporate the availability of foreign reserves into the FX

intervention. On the one hand, piling up foreign reserves while performing an FX buy intervention

may incur investment costs. On the other hand, implementing an FX sale intervention may be

restricted by the amount of foreign reserves available. Second, macroprudential instruments such as

capital flow management may strengthen or diminish the effect of FX intervention. Furthermore,

macroprudential tools aimed directly at the banking system, such as loan-to-value or reserve

requirements, may have different implications. It would be worth combining this analysis with our

framework.

32

Reference

Adler, G., Lama, R. and Medina, J.P. (2016), “Foreign Exchange Intervention under Policy

Uncertainty”, IMF Working Papers, No. WP/16/67.

Aizenman, J., Hutchison, M. and Noy, I. (2011), “Inflation Targeting and Real Exchange Rates in

Emerging Markets”, World Development, Vol. 39 No. 5, pp. 712–724.

Alla, Z., Espinoza, R. and Ghosh, A.R. (2017), “FX Intervention in the New Keynesian Model”, IMF

Working Papers.

Amato, J.D. and Gerlach, S. (2002), “Inflation Targeting in Emerging Market and Transition

Economies: Lessons after a Decade”, European Economic Review, Vol. 46 No. 4–5, pp. 781–

790.

Batini, N., Levine, P., Pearlman, J. and Gabriel, V. (2010), “A Floating versus Managed Exchange

Rate Regime in a DSGE Model of India”, Discussion Papers in Economics, University of

Surrey, Vol. DP 04/10.

Benes, J., Berg, A., Portillo, R.A. and Vavra, D. (2014), “Modeling Sterilized Interventions and

Balance Sheet Effects of Monetary Policy in a New-Keynesian Framework”, Open Economies

Review, Vol. 26 No. 1, pp. 81–108.

Berganza, J.C. and Broto, C. (2012), “Flexible Inflation Targets, Forex Interventions and Exchange

Rate Volatility in Emerging Countries”, Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 31

No. 2, pp. 428–444.

Bernanke, B.S., Gertler, M. and Gilchrist, S. (1999), “The Financial Accelerator in a Quantitative

Business Cycle Framework”, in Taylor, J.B. and Woodford, M. (Eds.), Handbook of

Macroeconomics, Vol. 1 Part C, North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp. 1341–1393.

Bernanke, B.S. and Mishkin, F.S. (1997), “Inflation Targeting: A New Framework for Monetary

Policy?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 97–116.

Blanchard, O.J., Adler, G. and de Carvalho Filho, I. (2015), “Can Foreign Exchange Intervention

Stem Exchange Rate Pressures from Global Capital Flow Shocks?”, IMF Working Paper, Vol.

WP/15/159.

Buffie, E.F., Airaudo, M. and Zanna, F. (2018), “Inflation Targeting and Exchange Rate Management

in Less Developed Countries”, Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 81, pp. 159–

184.

33

Cadarajat, Y. and Lubis, A. (2012), “Offshore and Onshore IDR Market : an Evidence on Information

Spillover”, Bulletin of Monetary Economics and Banking, Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 323–348.

Calvo, G. (1983), “Staggered Prices in a Utility Maximizing Framework”, Journal of Monetary

Economics, Vol. 12 No. 1978, pp. 383–398.

Calvo, G.A. and Reinhart, C.M. (2002), “Fear of Floating”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol.

CXVII No. 2, pp. 379–406.

Catalán-Herrera, J. (2016), “Foreign Exchange Market Interventions under Inflation Targeting: The

Case of Guatemala”, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, Vol.

42, pp. 101–114.

Chang, C., Liu, Z. and Spiegel, M.M. (2015), “Capital Controls and Optimal Chinese Monetary

Policy”, Journal of Monetary Economics, North-Holland, Vol. 74, pp. 1–15.

Chang, M.-C., Suardi, S. and Chang, Y. (2017), “Foreign Exchange Intervention in Asian Countries:

What Determine the Odds of Success during the Credit Crisis?”, International Review of

Economics & Finance, Vol. 51, pp. 370–390.

Christiano, L.J., Eichenbaum, M., Evans, C.L., Journal, S. and February, N. (2005), “Nominal

Rigidities and the Dynamic Effects of a Shock to Monetary Policy Nominal Rigidities and the

Dynamic Effects of a Shock to Monetary Policy”, Journal of Political Economy, The University

of Chicago Press, Vol. 113 No. 1, pp. 1–45.

Daude, C., Levy Yeyati, E. and Nagengast, A.J. (2016), “On the Effectiveness of Exchange Rate

Interventions in Emerging Markets”, Journal of International Money and Finance, Elsevier Ltd,

Vol. 64, pp. 239–261.

Farhi, E. and Werning, I. (2014), “Dilemma not Trilemma? Capital Controls and Exchange Rates with

Volatile Capital Flows”, IMF Economic Review, Vol. 62 No. 4, pp. 569–605.

Feenstra, R., Inklaar, R. and Timmer, M. (2015), “The Next Generation of the Penn Word Table”,

American Economic Review, Vol. 105 No. 10, pp. 3150–3182.

Galí, J. and Monacelli, T. (2005), “Monetary Policy and Exchange Rate Volatility in a Small Open

Economy”, Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 72, pp. 707–734.

Ghosh, A.R., Ostry, J.D. and Chamon, M. (2016), “Two Targets, Two Instruments: Monetary and

Exchange Rate Policies in Emerging Market Economies”, Journal of International Money and

Finance, Pergamon, Vol. 60, pp. 172–196.

Harmanta, Purwanto, N.M.A. and Oktiyanto, F. (2014), “Banking Sector and Financial Friction on

DSGE Model: The Case of Indonesia”, Bulletin of Monetary, Economics and Banking, Vol. 17

No. 1, pp. 21–54.

34

Henderson, D.W. and Rogoff, K. (1982), “Negative Net Foreign Asset Positions and Stability in a

World Portfolio Balance Model”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 13 No. 1–2, pp. 85–

104.

Juhro, S.M. and Mochtar, F. (2009), “Assessing Policy Rules in Indonesia: The Role of Flexible

Exchange Rates in ITF and Alternative Thinking about Policy Rules”, Bank Indonesia Research

Notes, No. March 2009, pp. 1–7.

Kolasa, M. and Lombardo, G. (2014), “Financial Frictions and Optimal Monetary Policy in an Open

Economy”, International Journal of Central Banking, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 43–94.

Kubo, A. (2017), “The Macroeconomic Impact of Foreign Exchange Intervention: An Empirical

Study of Thailand”, International Review of Economics & Finance, Vol. 49, pp. 243–254.

Lubis, A. and Rahadyan, H. (2018), “Monetary integration in the ASEAN Economic Community

challenge: the role of the exchange rate on inflation in Indonesia”, International Journal of

Services Technology and Management, Vol. 24 No. 5/6, p. 463.

Ramakrishnan, U. and Vamvakidis, A. (2002), “Forecasting Inflation in Indonesia”, IMF Working

Papers, Vol. WP/02/111.

Schmitt-Grohé, S. and Uribe, M. (2003), “Closing Small Open Economy Models”, Journal of

International Economics, Vol. 61 No. 1, pp. 163–185.

Smales, L.A. (2016), “Risk-on/Risk-off: Financial Market Response to Investor Fear”, Finance

Research Letters, Vol. 17, pp. 125–134.

Smets, F. and Wouters, R. (2007), “Shocks and Frictions in US Business Cycles: A Bayesian DSGE

Approach”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 97 No. 3, pp. 586–606.

Svensson, L.E.O. (2000), “Open-Economy Inflation Targeting”, Journal of International Economics,

Vol. 50 No. 1, pp. 155–183.

Taylor, J.B. (1993), “Discretion versus Policy Rules in Practice”, Carnegie-Rochester Conference

Series on Public Policy, Vol. 39, pp. 195–214.

The Financial Services Authority (OJK). (2017), Press Release: OJK Announces Higher Financial

Literacy and Inclusion Indices, available at: https://www.ojk.go.id/en/berita-dan-kegiatan/siaran-

pers/Pages/Press-Release-OJK-Announces-Higher-Financial-Literacy-and-Inclusion-

Indices-.aspx.

The World Bank. (2010), Improving Access to Financial Services in Indonesia, The World Bank,

Washington D.C.

Unsal, D.F. (2013), “Capital Flows and Financial Stability: Monetary Policy and Macroprudential

Responses”, International Journal of Central Banking, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 233–285.

35

Warjiyo, P. (2014), “The Transmission Mechanism and Policy Responses to Global Monetary

Developments: the Indonesian Experience”, BIS Papers, Vol. 78, pp. 199–216.

Wimanda, R.E., Turner, P.M. and Hall, M.J.B. (2012), “Monetary policy rules for Indonesia: Which

type is the most efficient?”, Journal of Economic Studies, Vol. 39 No. 4, pp. 469–484.

36

Appendix A Standard Deviation of Shocks

Table 4 Standard Deviation of Shocks Results

Std. dev. of shocks Prior mean Post. mean 90% HPD interval Prior Pstdev

ϵ A 0.01 2.1909 1.5459 2.7825 invg 2

ϵ M 0.01 0.113 0.0898 0.1318 invg 2

ϵ MS 0.01 0.0321 0.003 0.0578 invg 2

ϵG 0.01 0.0057 0.0025 0.0087 invg 2

ϵC 0.01 0.0064 0.0024 0.0111 invg 2

ϵ R 0.01 0.0079 0.0024 0.0146 invg 2

ϵ Π ¿ 0.01 4.1176 3.5616 4.8036 invg 2

Ξ 0.01 0.0078 0.0032 0.0131 invg 2

m ϵY 0.01 1.6633 1.4536 1.8882 invg 2

m ϵ C 0.01 0.2838 0.2397 0.3219 invg 2

m ϵ I 0.01 1.339 1.1421 1.5389 invg 2

37

Appendix B Prior and Posterior Distributions

38

39

Appendix C Impulse ResponseFigure 10 Impulse Response to Productivity Shock

Figure 11 Impulse Response to Mark-Up Shock

40

Figure 12 Impulse Response to Foreign Consumption Shock

Figure 13 Impulse Response to Foreign Interest Rate Shock

41

Figure 14 Impulse Response to Foreign Inflation Shock

42