Web of intrigue

description

Transcript of Web of intrigue

The mainstream art world has untilrecently had a rather uncertainapproach to internet-based art.Earlier manifestations of art onlinehave frequently been ghettoisedand struggled to be absorbed into

the core of art-world discourse, while museums’online commissions, like those of the WhitneyMuseum of American Art in New York and theTate in London, have only fitfully splutteredinto life.

But as the internet has naturally become partof the daily lives of artists, so art made on theinternet, or plundering its endless resources,has grown in prominence in art institutions.The New Museum in New York has led the way,with “First Look: New Art Online”, a monthlyseries of online exhibitions, as well as the regu-lar incorporation of digital art into group showsand its affiliation with the non-profit websiteRhizome, dedicated to “artistic practices thatengage technology”.

Meanwhile, digital art’s rising significance inthe UK alone is evident in three recent projects:the Serpentine Gallery’s AGNES, a digital com-mission by the Belgian-American artist Cécile B.Evans; Oliver Laric’s online project “Lincoln 3DScans” at Lincoln’s The Collection museum, win-ner of the Contemporary Art Society’s annualaward for museum and artist collaborations;and the imminent launch of Opening Times, anon-profit commissioning body for online art,supported by Arts Council England.

This increase in online commissioningmatches the rise of the much-debated idea of“post-internet” art, initially coined by artistMarisa Olson and sometimes called “internet-

aware” art, which is largely object-based andshown in galleries, but inextricably linked withthe language, form and content of the internet.Two shows reflect this tendency in differentglobal settings: “Speculations on AnonymousMaterials” at the Fridericianum in Kassel,Germany (until 23 February) and “Art Post-Internet”, which opens at the Ullens Center forContemporary Art in Beijing (1 March-11 May).

Karen Archey, the co-curator of the UllensCenter show with Robin Peckham, has spentyears curating and interpreting the work in this

new age. She admits that the post-internet termis problematic. The way to understand it, shesays, is “to think about ‘post’ in terms of under-standing it as meaning ‘after’, and ‘after’ mean-ing ‘in the fashion of’. When I talk about post-internet art I think about art that’s made withconsciousness of the networks that produce andtransmit it.”

So are we in the midst of an art-historicalshift? Yuri Pattison is a solo artist and a memberof the collective Lucky PDF, which is included inthe Ullens Center show. He believes art historycannot be isolated from the “incredible point ingreater world history” we have reached, “where

it is basically comparable to the industrial revo-lution, so everything will change. And of course,art will completely change, because there aresuch huge differences in the way we work andcommunicate and travel.”

Ben Vickers, the Serpentine’s first dedicateddigital curator, believes that the art world’s pon-derous response to these developments hasbeen crucial. “There’s a particularly good Randreport [by the US government-funded thinktank, the Rand Corporation] that talks abouttribes, institutions, marketplaces and networks,

and the basic argument is that, in the same wayas you saw the erosion of the Church to theinstitutions of the state and then later to themarketplace with financial capitalism, whatwe’re witnessing now is the same shift with net-works. But what’s particularly interesting in theart context is that the art world has been quiteslow to adapt to this stuff.”

This has meant that the new epoch for con-temporary art could develop organically. “Whatthat scene constitutes is a group of people thatjust met online and started doing stuff them-selves,” Vickers says. “They wrote the texts, theyput on shows and decided what that looks like.

And now, in the past 18 months, you’ve seen arapid adoption of it on the part of institutions.”

Part of the difficulty for museums and gal-leries has been a reluctance from internetartists to engage with the traditional art-worldmodel. “Net art really came into being in themid-1990s and then it was a group of artists thatactually didn’t want to be affiliated with institu-tions,” says Melanie Bühler, the founder ofLunch Bytes, an online platform and discussionseries dedicated to art and digital culture. Thenet artists “conceived of the internet as a spacewhere they could express themselves freelyaside from the institutions”, Bühler says, “sothere was a notion involved of creating some-thing entirely of their own”.

The networked generationEven today, an ambivalence to the art worldexists among some digital artists. The Lucky PDFcollective, whose online works sit somewherebetween a magazine TV show and a group exhi-bition, are at once artists, curators and produc-ers and have said that their ultimate commis-sion would be to direct a music video for thehip-hop artist Kanye West.

Vickers, who has worked with Lucky PDF,believes this attitude flummoxes institutions. “Ifyou don’t think that the gallery space or even theart world at large is the primary site of displayfor the ideas that you’re trying to narrate, then itactually doesn’t matter too much whether one ofyou says, ‘I am the artist’,” he says. “It’s one ofthe most interesting shifts that we are seeing inthis moment, and the one that’s most difficult tounderstand for existing institutions, because itcompletely breaks the model—how does a

THE ART NEWSPAPER Number 254, February 201450

FEATUREInternet art

LUCK

Y PD

F: O

SKAR

PRO

CTOR

, 201

2; A

LL R

IGHT

S RES

ERVE

D. P

HOTO

: OSK

AR P

ROCT

OR; S

TYLI

ST: H

ANNA

H R.

HOP

KINS

; MAK

E-UP

ART

IST:

LUCY

JOAN

PEA

RSON

Web of intrigue

“Before, you had to rely on showcasing your work to galleries orcurators… today, artists can decide how to brand and distributetheir own work—they’re the master of their own images”

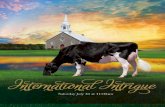

幸運PDF S/S 2013, a fashion collection bythe collective Lucky PDF, in which they createdpatterned fabrics by appropriating imagescreated by artists in their online network

In the ‘post-internet’ age, digital artists are reassessing their relationship with galleries and collectors. By Ben Luke

!

050-051 Features Online art 22/01/2014 09:48 Page 2

THE ART NEWSPAPER Number 254, February 2014 51

PETR

A CO

RTRI

GHT

AND

RAFA

ËL R

OZEN

DAAL

: STE

VE T

URNE

R CO

NTEM

PORA

RY. Y

URI P

ATTI

SON:

LEGI

ON T

V, LO

NDON

AND

THE

ART

IST.

VAN

DEN

DORP

EL: C

OURT

ESY

THE

ARTI

ST A

ND W

ILKI

NSON

GAL

LERY

LOND

ON

gallery begin to represent a network?”Many of those networks began life as “surf

clubs”, essentially a collaboratively producedblog, in which artists posted found and manipu-lated online imagery. They were the “primaryform of output for a lot of artists for a longtime”, and fundamental to post-internet art,Archey says. Among them was Club Internet, asite founded by the Dutch-born, Berlin-basedartist Harm van den Dorpel, who invited guestartists from across the world, essentially curat-ing international group exhibitions of online art.

Attilia Fattori Franchini, the founder of theonline project space bubblebyte.org and thecurator of the Opening Times website, says that“empowering the artist has been one of the fea-tures of the digital revolution”. She adds:“Before, you had totally to rely on showcasingyour work to galleries or curators,whereas today, artists can decidehow to brand and distribute theirown work, through whichchannels, to which commu-nity or blog or online web-site—they’re the master oftheir own images.”

Yuri Pattison, whomade a project forbubble byte, says thatthis sense of a globalcommunity has spilledover into post-internetart, where, he says, “thespeed of engagement” withfellow artists has createdhuge possibilities. “If you’reinterested in an artist, you canfind their website and you can pro-pose to do a show with them,” says theLondon-based artist. “And even if they live inNew York, they can send you the files and youcan fabricate them at this end. You can have aninternational group show with no money, withthe same impact as something that could’vehappened 20 years ago at great expense.”

Rise of the digital nativesKey to this scene has been the democratisationof online programmes. “Before, the internet wasa language that was open to few people,” saysFattori Franchini, and online works were largelycreated by artists who knew complex codinglanguages, but today’s digital art is informed by“the easier access we all have into making work,from a software point of view. Programmes arebecoming easier and easier to use, and the latestgeneration was born digital.”

Among the highest profile of these digitalnatives is the Los Angeles-based Petra Cortright,who first gained interest with vvebcam 2007,2007, a self-portrait for the YouTube age, inwhich she filmed herself nonchalantly flickingthrough the visual effects of a cheap webcam,

including animatedpizza slices. It trig-gered a series of

webcam films usingfreeware she finds

online—chance discov-eries are fundamental to

her approach. “I reallyenjoy that aspect of the hunt,”

she says, “and I use whatever I canget my hands on.” She uses Mac and PC

platforms because “there’s so much more weirdfreeware” on PC, that is “kind of virusy, you’realmost scared to install it. But this is exactlywhy this stuff is the best.” Like many artists,Cortright naturally flows between online worksand physical objects. “I make files, that seemslike the most honest way to describe what I do,and then it’s really exciting to be able to have somany outcomes,” she says.

Cortright’s recent show at the Steve TurnerContemporary gallery in Los Angeles included“digital paintings”, actually Photoshop imagesprinted on aluminium, as well as the webcamvideos and flash animations. Turner also repre-sents Rafaël Rozendaal, another leading internetartist. When Turner began working with them,the two artists “made very little that existed inthe physical world”, he says. “Rafaël made web-sites and those websites exist on the internetand if someone wishes to look at them, they canlook at them for free and if someone has theinclination to own it—since ownership is oftena key element in the history of art—they can

buy it.” Turner says of Rozendaal that he “knewnot to ghettoise him” and he now makes lentic-ular prints that reflect the exuberant plays onabstraction found in some of his websites. “He’sstill dealing with the same issues, the same con-cerns, the same curiosities,” Turner says, “buthe’s figured out—because he wanted to—how toshow those works in a physical space.”

The cash questionCortright and Rozendaal have taken novelapproaches to selling their work. Cortright,uneasy at defining the price of her online work,has used an algorithm to decide it for her, basedon the number of YouTube views: when The ArtNewspaper viewed the work footvball/faerie, 2009,which was included in the Los Angeles CountyMuseum of Art’s exhibition “Fútbol: theBeautiful Game” (2 February-20 July), ithad garnered 10,626 views and wasvalued at $3,131.30. Meanwhile,Rozendaal has published on hiswebsite the contract for howprospective collectors must usehis online works .

Certainly, the trend in post-internet art towards digitally-created physical works hashelped drive the market’sinterest in its artists, withmany signing up with gal-leries. But Karen Archeysays some artists remain scepti-cal: “It’s partially that the art world is

a really gross, fierce place, and I think that peo-ple that work online, and do so exclusively, doso for a reason. Just to speculate, I think theydon’t want to be part of the market, but alsodon’t feel that they’re capable of existing in it…A lot of these people that choose to work onlinesee others that entered into the gallery systemas playing a game that is going to fuck themover and chew them up and spit them out, andthat maybe they think that people who workwith galleries now are too good for them.”

Archey is acutely aware that the post-inter-net phenomenon is the art world’s “next bigthing” and hopes her Beijing show will help pre-vent it being seen merely as a trend. “[It] willcreate lineages for this work, so that it’s rootedin a history and a lineage of knowledge andartistic labour,” she says. In the show, post-inter-net artists such as Laric and Van den Dorpel areshown alongside established figures such asDara Birnbaum and the Bernadette Corporation.“My feeling is that I really do care about andlove this work and feel to some extent like ashepherd of it and don’t want it to be swattedaway by a capricious art world,” Archey says.“The way you make something not a trend is byidentifying the roots and letting them grow.”• First Look: www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/online;Rhizome: www.rhizome.org; Opening Times:www.otdac.org; Oliver Laric: www.oliverlaric.com;Lunch Bytes: www.lunch-bytes.com; Yuri Pattison:yuripattison.com; Lucky PDF: www.luckypdf.com;Harm van den Dorpel: www.harmvandendorpel.com;bubblebyte: www.bubblebyte.org; Petra Cortright:petracortright.com; Rafaël Rozendaal:www.newrafael.com

Net gains: five recent works capturing the new spirit in online art

A still from Petra Cortright’s video, RGB, D-LAY, 2011 (above), Harm vanden Dorpel’s Assemblage (everything vs. anything), 2013 (left), and(below) a screen shot of Rafaël Rozendaal’s jellotime.com, 2007

“Programmes are becomingeasier to use, and the latestgeneration was born digital”

Lincoln 3D Scans, 2013The Collection, Lincoln, and Oliver Laricwww.lincoln3dscans.co.ukLaric made 3D scans of works from the col-lections of two Lincoln museums, thearchaeology works at The Collection andsculptures from the Usher Gallery, fromRoman busts to medieval armour and evena skeletal pelvic bone. These can be down-loaded for free and then manipulated usingfree programmes listed by Laric to createentirely new works—these manipulationscan be viewed on the website (FernandoFoglino’s is pictured). The work relates toLaric’s ongoing “Versions” project, in whichhe plays on the culture of bootlegs, copiesand remixes in the networked internet age.

Dorm Daze, 2011Ed Fornieleswww.facebooksitcom.comFornieles’s self-styled “Facebook sitcom”,which has been bought as an installationby the Zabludowicz Collection, is a vastthree-month long online performance inwhich Fornieles created a self-containednetwork on Facebook. Participants playedfictional roles based on “scalped” accountsof real-life students at University ofCalifornia, Berkeley, and created a soapopera of philandering “hotties”, drugabuse, unrequited homosexual love and,of course, death. Ben Vickers, who hasworked with Fornieles for some time, saysof the artist: “At times his work is totallyabhorrent, but it acts as this social mirror.”

You, the World and I, 2011Jon Rafmanyoutheworldandi.comA modern-day telling of the Orpheusmyth, Rafman’s digital video tells the storyof a man searching for a lost love whorefused to be photographed, because “shewould rather think of things the way theywere in her memory”, and the mournfulnarrator searches for a record of their timetogether online. Using digital renderings ofheritage sites and images found on GoogleEarth and Google Street View, Rafman’svideo reflects on a world experiencedincreasingly virtually, in which even themost private of us leaves a trace.

AGNES, 2012-13Cécile B. Evansserpentinegalleries.org/exhibitions-events/agnesThe Serpentine’s colourful first digitalcommission, is, according to Evans, “aspambot” who lives on the gallery’s web-site and will evolve over the comingmonths. “Please answer my questions so Ican help you with yours,” AGNES tells us ina video. You can then respond to differingqueries, asking how you end a phone callor where you go when you need to bealone. Crucially, and rather uncomfortably,you are then asked for your email address.Vickers, the project’s curator, says theproject began before the NSA (NationalSecurity Agency) revelations, “but it’sheavily predicated on this identity that’scollecting information about you butwants to reward you for it”.

RELiable COMmunication,2013Yuri Pattison for Legion TVreliablecommunications.netInternet art for the post-NSA scandal era,Pattison’s dense and absorbing work isbased on the Soviet Coup Archive, a digitalarchive relating to the attempted coup d’etat in 1991. The archive, Pattison says, is“a ‘pre-internet’ internet that was estab-lished in the Soviet Union that had connec-tions with the West”. Not deemed a majormedia source, it was uncensored and “itactually prevented the coup because peo-ple were feeding out information.” Pattisonlinks the material to another famous leak:the soldier Chelsea Manning’s conversa-tions about the leaking of classified infor-mation with Adrian Lamo, who eventuallyturned her over to the US authorities.

050-051 Features Online art 22/01/2014 09:49 Page 3