Water efficiency - Austin, Texas...dential Energy Efficiency audit pro-gram to install low-flow...

Transcript of Water efficiency - Austin, Texas...dential Energy Efficiency audit pro-gram to install low-flow...

B Y T O N Y T . G R E G G , D A N S T R U B , A N D D R E M A G R O S S

conservation

Water efficiency

he city of Austin is located in central Texas andreceives approximately 34 in. (812 mm) of rainfall onaverage each year (National Climatic Data Center,2006). The months of July and August are the driestand are often without rainfall for three to four weeks

at a time. The extended dry periods increase overall water usein summer by almost 100% over water use in winter.

Austin receives all of its water from the Colorado River(Texas) through water rights granted by the state of Texas andbacked by storage in lakes managed by the Lower Colorado

River Authority (LCRA). Austin’s water supply is backed bystorage as firm water rights (325,000 acre-ft/year [65 milm3/year]), which are expected to meet demand through 2040without an aggressive conservation and reclaimed water pro-gram. With an aggressive conservation and reclaimed water pro-gram, these water rights should be sufficient through 2050.

INCREASING DEMAND LEADS TO CONSERVATIONIn the late 1970s and early 1980s, Austin voters rejected bond

authorizations for system improvements despite rapid growth in theregion. As a result, high water pumpage levels threatened service deliv-

ery in the summer of 1982. To reduce the demand for water, AustinWater Utility developed the Emergency Water Conservation Ordinance

(EWCO). This ordinance, approved by the city council in February 1983,authorized the city manager to impose mandatory restrictions on outdoor

water use to• assure adequate capacity to meet firefighting needs;• assure adequate service to all customers by spreading out peak demands; and• minimize the potential for service disruptions resulting from stress-

related equipment failures.

76 FEBRUARY 2007 | JOURNAL AWWA • 99:2 | PEER-REVIEWED | GREGG ET AL

WAT E R C O N S E R VAT I O N E F F O R T S

I N A U S T I N H AV E C O N T R I B U T E D

T O A S U B S TA N T I A L R E D U C T I O N

I N P E R C A P I TA WAT E R U S E .

T

in Austin, Texas, 1983–2005: An historical perspective

2007 © American Water Works Association

GREGG ET AL | PEER-REVIEWED | 99:2 • JOURNAL AWWA | FEBRUARY 2007 77

From 1984 to 1987, demandmanagement was primarily seen asan emergency or crisis response toinfrastructure inadequacies. Sincethen, however, water conservationefforts in Austin have evolved intoprograms designed to reduce peak-day demand and average per capitause. Water conservation efforts arealso aimed at delaying the construc-tion of additional water treatmentplant capacity and extending the timebefore which the city will exceed itswater rights.

The city now views efficiency asone of the strategies required to meetits long-term water needs. Austin’s cur-rent water conservation goals are to

• reduce the 1990 projection of2005 peak-day water use and averageper capita daily water use by 10 and5%, respectively;

• reduce the projected demand in2050 of 376,000 acre-ft/year (75 milm3/year) to 325,000 acre-ft/year (65mil m3/year) by 2050 in conjunctionwith Austin Water Utility’s reuse proj-ect; and

• achieve as much of this sav-ings as feasible by 2016 to delay anannual payment to the LCRA of $8million–$13 million. (Under the 1999agreement between the city and theLCRA, the city prepaid for water useup to 201,000 acre-ft [40 mil m3] peryear. Once the city exceeds 201,000acre-ft per year for two consecutiveyears, it must pay annually for allwater use over 150,000 acre-ft [29.9mil m3] per year.)

SERVICE AREA GROWTH SPURSADDITIONAL CONSERVATION NEED

The city of Austin has been grow-ing steadily over the past few decades.Figure 1 illustrates both the bur-geoning population levels andincreasing total water consumption.Between 1984 and 2004, the popu-lation of the Austin service area grewfrom approximately 466,100 to789,000—a 69% increase.

Through a combination of pro-grams targeting inefficient water usepractices, Austin has managed tokeep demand growth well below the

rate of population growth. Totalwater pumpage between 1984 and2004 increased only 35%, from35.071 to 47.519 bil gal (133 to180 GL).

PROGRAMS DESIGNEDTO ADDRESS SPECIFICWATER USE ISSUES

Tools assist customers in easingexcessive landscape irrigation. Asmuch as 50% of August water useis for irrigation, which puts a tremen-

dous load on Austin’s water treat-ment plants and system. In a partic-ularly hot, dry summer, uncheckeddemand could exceed treatmentcapacity. The 1983 EWCO addressedthe immediate problem by limitinglandscape irrigation to a five-dayschedule during drought restrictions,with additional limitations imposedif the drought worsened. The ordi-nance was enforced by ticketing vio-lators with fines of up to $500 perviolation. Restrictions were imposed

2007 © American Water Works Association

An award-winning demonstration at Zilker Botanical Gardens shows Austin customers how

to design, install, and maintain rainwater harvesting equipment.

78 FEBRUARY 2007 | JOURNAL AWWA • 99:2 | PEER-REVIEWED | GREGG ET AL

again in the summers of 1984–1986,but lifted each year once the summerirrigation season had ended.

By the late 1980s, increased capac-ity had alleviated pressure on the sys-tem; however, excessive outdoorwatering continued to be a highlyvisible indicator of water waste. Mostof the worst offenders were proper-ties with automatic irrigation sys-tems. In response, Austin’s WaterConservation Division (WCD) estab-lished a free irrigation audit program.Customers often have a poor under-

standing of how their controllerswork, have multiple programs orstart times they are unaware of, lacka backup battery in their controller,or have heads that mist because ofexcessive pressure. As part of the irri-gation audit program, the city waterauditor checks customers’ systemsfor leaks, water application rates,and adequate coverage. The auditoralso assesses the adequacy of theequipment and recommends replace-ment of components if appropriate.(In many cases, recommended up-grades are eligible for rebates.) Cus-tomers are given a watering sched-ule that takes into account factorssuch as plant type and shade cover-age, allowing them to water to theevapotranspiration rate. On the basisof internal data comparing averagesummer water use before and afterirrigation audits, these audits often

result in reductions of 30% or morein irrigation water use.

Although the irrigation auditsassisted customers who had auto-matic irrigation systems, it was feltthat more could be done to assisthomeowners who irrigated usinghose-end sprinklers. It was observedthat many homeowners who irrigatewith hose-end sprinklers often leavethem on longer than they intend.Thus in 1997, the WCD began offer-ing free hose timers. These timers areattached between a faucet and a hose

and will shut off the water flow afterthe amount of time set by the user.

By the late 1990s, Austin wasonce again experiencing explosivegrowth that put pressure on watertreatment system capacities. Adrought in the summer of 2000caused the imposition of wateringrestrictions for the first time since1986. Enforcement of the restrictionshighlighted several of the shortcom-ings in the EWCO, and revisions tothe ordinance were made before thesummer of 2001. These revisionsincluded clarifying restrictions on carwashes and the irrigation of sportsfields and newly installed landscapes,and extending the prohibition onwasting water to a year-round basis.The EWCO is used largely as a mar-keting tool in Austin; the city prefersto contact customers and work withthem directly to eliminate the prob-

lem rather than turning immediatelyto fines and citations.

Xeriscape programs discourage useof inappropriate landscape materials.Many Austin residents have come tothe city from other parts of the coun-try, often from areas with a differentclimate and different native vegeta-tion. To re-create familiar landscapesin Austin’s hotter, drier climate, resi-dents must use excessive amounts ofwater, which drives up peak-daywater demand in the late summermonths. Xeriscaping, which empha-sizes the practice of using plants thatare native or adapted to the climate,can reduce or even eliminate the needfor irrigation.

Austin has used several programsto encourage native landscapes,including the “Xeriscape It” edu-cation program launched in 1984.This program promoted the princi-ples of Xeriscaping through a vari-ety of outreach and education pro-grams. In addition, the WCDproduced a quarterly Xeriscapenewsletter; organized and con-ducted Xeriscape schools, seminars,and garden tours; and workedclosely with Austin’s XeriscapeAdvisory Board and the XeriscapeGarden Club on joint activities.

By 1994, it was evident that theseefforts were not as successful asplanned. Most residential and com-mercial landscapes continued to com-prise large areas of poorly adaptedand water-inefficient turfgrasses. Inresponse, two new initiatives wereintroduced. The first was a residentialrebate program for installing plantsand turfgrasses that were betteradapted to Austin’s climate. The sec-ond initiative was an ordinance thatrequired all new commercial land-scapes to use native or adapted plantsand established standards for irriga-tion systems.

Both of these initiatives met withmixed success. The program attractedcustomers with already low wateruse. As a result, residences partici-pating in the rebate program showedlittle to no change in water use. Inaddition, though the plants they in-

2007 © American Water Works Association

300,000

400,000

500,000

600,000

700,000

800,000

Year

Po

pu

lati

on

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

Pu

mp

age—

mg

d

Population Average-day pumpage

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

FIGURE 1 Austin area population and total water use changes, 1984–2001

GREGG ET AL | PEER-REVIEWED | 99:2 • JOURNAL AWWA | FEBRUARY 2007 79

stalled required less irrigation, someowners continued to water them as ifthey were high-water-need plants.Thus the program was altered toemphasize only trees and shrubs inorder to promote a hardier group ofplants with long-lasting savings, pro-vide shade for thirsty turfgrasses, andreduce the evapotranspiration fromthe rest of the landscape.

The commercial landscape ordi-nance was a compromise, because itwas based on an existing ordinanceintended to promote beautification.The revised ordinance retained mostof the beautification elements, eventhough they sometimes conflictedwith water-wise management prac-tices. For example, the ordinancerequired irrigation systems for alllandscapes whether or not theplants needed irrigation, and re-quired raised islands for landscapeareas in parking lots althoughground-level plants could havetaken advantage of water drainingfrom the pavement.

Inefficient plumbing fixtures offerretrofit opportunities. In 1985, theTexas Water Commission issued anenforcement order to the city ofAustin for water quality violations.Under order to reduce its wastewaterdischarges and with its water treat-ment system under pressure of highdemands, Austin was required toimplement retrofit programs toreplace inefficient plumbing fixtures.Because many toilets and shower-heads were using excessive amountsof water and contributing to capac-ity problems at the city’s wastewatertreatment plants, the WCD teamed

with the electric utility in the Resi-dential Energy Efficiency audit pro-gram to install low-flow showerheadsand toilet dams, which are barriersinstalled in toilet tanks that preventsome of the water from beingreleased when the toilet is flushed.This program resulted in the instal-lation of 37,903 low-flow shower-heads and 52,471 toilet dams in34,880 residences between 1984 and1990 at a cost of approximately $17per household.

In late 1985, the Austin CityCouncil adopted the CommercialWater Conservation Retrofit Ordi-nance to comply with an AgreedEnforcement Order from the TexasWater Commission. The ordinancerequired all commercial customers,including multifamily properties, toretrofit all plumbing fixtures to meetcompliance standards outlined in the1983 plumbing code amendments,which required toilets to flush 3.5gpf (13 Lpf) or less. Between 1986

2007 © American Water Works Association

Violations of Austin’s water use

management ordinance, such as this

broken sprinkler head, are subject to fines

of up to $500 per occurrence per day.

Austin has distributed more than 8,900

subsidized rain barrels, like these

at a customer’s home.

80 FEBRUARY 2007 | JOURNAL AWWA • 99:2 | PEER-REVIEWED | GREGG ET AL

and 1990, the WCD expanded theretrofit effort to residential customers,offering door-to-door installation oflow-flow showerheads, faucet aera-tors, and toilet dams.

Savings from the toilet dams inresidential toilets were unreliableand were seen as a stopgap measureuntil additional capacity was con-structed. At the same time, the 3.5-gpf standard for commercial prop-erties was considered excessive. Amore direct strategy was requiredto solve the problem. In 1991, thecity passed an ordinance prohibit-ing the installation of any toilet thatflushed more than 1.6 gpf (6 Lpf).This was followed in 1992 by stateand federal legislation mandatingthe 1.6-gpf models.

These new laws ensured that all newtoilets would be low-flow models, but

did nothing to address toilets that hadalready been installed. In response, theWater Conservation Division instituteda toilet replacement program. The firstincarnation of the program in 1992allowed residential, multifamily, andcommercial customers replacing old,large-capacity toilets with low-flowmodels to get rebates of $60–80 pertoilet (depending on the toilet price).

In 1994, it was recognized thatlow-income homeowners might not

have the means to participate in therebate program, so the WCD begana free toilet program. The city con-tracted with a local plumbing dis-tributor to supply toilets to cus-tomers who presented city-issuedvouchers at the distributor’s store.The program was initially limited tolow-income residential customers,but it was opened to all residentialcustomers in 1996 and to multifam-ily and commercial customers in1998. Finally, in 1999, customerfeedback indicated that the cost ofinstalling the toilets was an impedi-ment to participation, so the WCDinstituted a $30 per toilet rebate forinstallation by a licensed plumber.

In the spring of 2002, researchshowed that the savings gained bylow-flow toilets was often lost oncethe flapper was replaced. Finding

the correct replacement flapper fora toilet was often difficult, if not im-possible, and using the wrong flap-per could change a 1.6 gpf (6 Lpf)toilet into a 5 gpf (19 Lpf) toilet. Asa result, the toilet rebate programwas suspended.

The rebate program resumed inDecember 2002, with rebates limitedto toilet models that did not lose theirlow-flush volumes when the flapperwas replaced with a commonly avail-

able one. Rather than use the LosAngeles Department of Water andPower’s Supplemental Purchase Spec-ification, developed in 2000, Austinrefined the list to exclude all toiletswith early-closing flappers.

In 2004, Austin added a perfor-mance specification based on theMaximum Performance (MaP) test-ing protocol. Toilets eligible forAustin’s rebates must not use anearly-closing flapper and must flusha minimum of 250 g of waste mate-rial (Gauley & Koeller, 2003). Thefree toilet program was not affectedbecause the toilet distributed throughthat program retained its low-flushvolume even with a standard flapperreplacement.

Austin’s program was not the onlyone grappling with this problem.Many water conservation programsbegan limiting the toilet models thatqualified for their replacement pro-grams, but without coordinationamong those programs, toilet manu-facturers were faced with many dif-ferent sets of qualification criteria tomeet. In response, a group of con-servation professionals met in Janu-ary 2004 and agreed that the failureto maintain flush volumes, as wellas long-standing complaints abouttoilet performance, demanded a uni-fied standard for toilet performance.

This new standard, known as theUnified North American Require-ments (UNAR), will set limits on theflush volume of a toilet after it is fit-ted with a standard flapper. Flush-ing performance, which has been abarrier to acceptance since the 1.6-gpftoilets were introduced, will be eval-uated by incorporating the MaP test-ing protocol.

The UNAR will also address anumber of other factors, includingreplacement part identification andavailability, standards for chemical-resistant flappers, and the use of fillvalves that are not susceptible tocreep or leakage. The UNAR will bea strictly voluntary system but couldlead to a single, uniform list of toiletmodels that qualify for many replace-ment programs. This clear set of stan-

2007 © American Water Works Association

203

192

212

191

221

202

188

175

186 190

180

168 172

176

153 157

173

161

175

166

172

164

168

165

150 155 160 165 170 175 180 185 190 195 200 205 210 215 220 225

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

Year

Wat

er U

se—

gp

cd

FIGURE 2 Nonindustrial per capita water use per day in Austin, 1980–2003*

*Texas Water Development Board data to 2000, city data to 2003

Trend line

GREGG ET AL | PEER-REVIEWED | 99:2 • JOURNAL AWWA | FEBRUARY 2007 81

dards, coupled with the market forceof multiple toilet replacement pro-grams, will send a clear signal to toi-let manufacturers and drive the mar-ket toward better-performing and-conserving toilets.

In November 2004, dual-flush toi-lets became available in the Austinmarket. These toilets have two flush-ing options: a standard 1.6 gpf and areduced flush, usually 0.8 or 1 gpf,that clears liquid waste from thebowl. Studies have shown that thesetoilets can result in average flush vol-umes of 1.2 gpf (Koeller, 2003). Fourmodels (three manufactured by Car-oma and one by Kohler’s SterlingDivision) met the UNAR standardsand were added to the toilet rebateprogram in 2004.

The toilet replacement programin Austin has been successful, withwell more than 50,000 toilets dis-tributed under its various initiatives.As of 2005, the program has saved in

excess of 700,000 gpd of waterthrough commercial, multifamily,and single-family retrofits.

ADDITIONAL WATERCONSERVATION EFFORTS SEEKTO EXPAND SAVINGS

Commercial and industrial initia-tives offered. By 1996, the WCD hadactive programs to address landscapeirrigation and retrofitting old toilets,but nothing to assist commercial orindustrial customers who use water inthe course of their business. If incen-tives could be offered to conservewater, savings could be significant.For example, Austin has several largecomputer chip manufacturers whosemanufacturing processes can usemore than 2 mgd (7.57 ML/d) ofwater per plant. By changing wateruse practices (e.g., reusing rejectwater from reverse osmosis filters),water use could be reduced by20–40%. However, manufacturers

needed incentives to shorten thepayback period on the necessaryequipment.

The WCD responded by offer-ing rebates of up to $40,000 perproject, with the amount of therebate limited to half the cost ofthe improvement up to $1/galsaved per day. Manufacturerssuch as Motorola, AMD, andSamsung have taken advantageof the program, conserving 1.5mgd (5.68 ML/d) of water.

In 2004, the WCD identified anew opportunity for water sav-ings in restaurants. The sprayvalves that most restaurants useto rinse dishes before washingoften use 3–6 gpm (12–24 L/min),although new valves are availablethat use only 1.6 gpm (6 L/min).These valves are relatively inex-pensive and easy to install, but

most restaurants were not aware ofthe valves or of the savings theywould bring. To raise awareness ofthese valves, WCD staff members vis-ited restaurants, performing wateraudits and replacing old spray valveswith new 1.6-gpm valves. In less than1 year more than 300 spray valveshad been replaced, saving 60,000 gpd(225,000 L/d) of water.

In 2005, the Texas Legislaturepassed House Bill 2428, which man-dates that as of Jan. 1, 2006, onlyspray valves with a flow rate of 1.6gpm or less can be sold or distrib-uted throughout the state. Once thewater-efficient spray valves hit mar-ket saturation, the state has thepotential to save approximately 2.6bil gal of water each year (SBW Con-sulting, 2004).

Clothes washer rebates offered. Inthe United States, nearly all clotheswashers have been top-loadingdesigns, traditionally using 40%

2007 © American Water Works Association

Licensed irrigator and water

conservation staffer Jessica Woods

performs a commercial irrigation

system evaluation.

82 FEBRUARY 2007 | JOURNAL AWWA • 99:2 | PEER-REVIEWED | GREGG ET AL

more water than newer front-load-ing models. However, the front-load-ing machines are more expensivethan traditional washers, with sug-gested retail prices ranging from $500to $1,500.

The WCD has addressed thisproblem by giving rebates for high-efficiency washing machines. Therebate program is designed to bringthese prices more in line with tradi-tional machines with the same levelof features. The program offersrebates of up to $100 for the pur-chase of a new front-loading washer.As a result, the front-loadingmachines have been gaining in pop-ularity, and more models have beenintroduced as sales have increased.

In August 1998, 12 models avail-able from five manufacturers wereeligible for the rebate. As of 2005,145 qualifying models were avail-able from 28 manufacturers. Theprogram determines eligible modelsfrom a list published by the Consor-tium for Energy Efficiency, offeringrebates on washing machines locatedin tiers 3a and 3b of the list.

The number of rebates givenannually has also increased from 925in 1998 to 2,220 in 2004. By 2005,more than 12,300 rebates hadbeen issued for a total water sav-ings of more than 187,000 gpd.

In addition to generatingwater and energy savings, theseefficient washing machines havealso expanded the market, allow-ing some manufacturers to beginlowering prices as a result ofeconomies of scale.

Submeters encouraged in mul-tifamily dwellings. All propertieshave always had metered waterservice in Austin. However, manyproperties with multiple dwellingunits have had a single mastermeter for the entire property.

Thus people living in multifamilyproperties often did not pay directlyfor the amount of water they used.Absent this direct link, they lackedfinancial incentives to conserve. Stud-ies have shown that savings of15–30% can be achieved by switch-ing a multifamily property from mas-ter meter billing to direct meteredbilling (Mayer, 2004).

In Austin, local and state codesdivide multifamily dwellings intotwo classes: those with two to fourdwellings and those with five ormore. In 2000, the WCD was ableto work with Austin Water Utilityto require that all new two-, three-,and four-dwelling properties have adedicated water meter for eachunit. In addition, because most ofthese properties are rental proper-ties and may share a single irriga-tion system, a separate meter isrequired to serve any irrigation sys-tem for the property. This enablesthe irrigation water to be separatedfrom the tenants’ usage and eitherpaid for by the landlord or dividedequally among the tenants.

In apartments with master meters,state law permits the management todivide water bills among tenants

using a formula on the basis of thenumber of people living in the prop-erty, the number of square feet in thetenant’s apartment, or a combina-tion of the two. They can also installprivate submeters for each apartmentand charge each tenant only for thewater he or she uses. Althoughinstalling and reading the meters ismore costly for the property owners,it is much more equitable than charg-ing on the basis of an arbitrary for-mula and is overwhelmingly pre-ferred by the tenants.

Nevertheless, the majority ofapartment properties that chargedtenants separately for water weredoing so using a formula. In re-sponse, the WCD supported a billin 2001 to change state law in or-der to encourage new propertiesto be equipped with submeters foreach apartment unit or to have thewater utility install a meter in eachunit, with the meters to be sup-plied, maintained, read, and billedby the utility.

Commercial irrigation meters re-quired. For years the WCD receivedcomplaints about commercial prop-erties that wasted water irrigating.However, many of the properties

2007 © American Water Works Association

As shown at this Austin-area Sears

store, point-of-purchase displays help

promote the WashWise Rebate

Program.

GREGG ET AL | PEER-REVIEWED | 99:2 • JOURNAL AWWA | FEBRUARY 2007 83

were not aware of how much waterthe irrigation system was wastingbecause the system drew water fromthe same meter as the rest of theproperty’s water uses. To give theseproperty owners the informationneeded to manage their water use,in 2000 the WCD and the AustinWater Utility established criteriarequiring that all new commercialproperties over a minimum sizeinstall a meter to register irrigationuse. Because the water that passesthrough this meter is not returnedthrough the sanitary sewers, theowners are not charged for sewageon this water, helping to offset thecost of the meter.

Rainwater harvesting encouraged.Texas has a rich history of rainwaterharvesting. Many ranches and homesin the Hill Country immediately westof Austin are dependent on rainwa-ter. However, with the advent ofmodern water treatment and distri-bution systems, rainwater harvest-ing has fallen from favor and by 2000was virtually unheard of in the city’swater service area.

Rainwater is a highly valuableresource and can effectively increasethe amount of water available for

irrigation. People who use rainwa-ter become more aware of their wateruse patterns as a result of managingtheir private supplies. Rainwater isalso more beneficial than treatedwater for irrigating plants, a charac-teristic highly valued by gardeners.As a result, in 2000, the WCD of-fered rebates for rainwater harvest-ing: a $30 rebate for purchasingapproved rain barrels and a rebateof up to $500 for larger systems, de-pending on the storage capacity andcost of the system. Unfortunately,there were few local suppliers of rainbarrels, and few residential customershad the room to accommodate alarger system.

In April 2001, the WCD insteaddecided to supply barrels to its cus-tomers at a reduced, subsidizedprice. Purchasing 1,000 barrels bythe truckload, the program offeredthem to customers at $20 each andsold out in approximately 8 hours.Demand has continued despite anincrease in the price to $60 per bar-rel, and sales and distribution datesare now scheduled every two tothree months. Since its inception,the program has sold more than6,000 rain barrels.

Although water savings from rainbarrels are marginal compared withother water conservation programs(approximately 0.5 gpd [1.9 L/d]),the program has been an effectivemarketing tool. The popularity ofthe program has spurred interest inlarger rainwater systems and in-creased the number of rain barrelrebates issued. Rain barrel distribu-tions also provide an opportunity tointroduce customers to other pro-grams and have generated substantialrepeat participation.

Though the city of Austin offersrainwater harvesting rebates toencourage homeowners to add rain-water harvesting systems to existinghomes, no program currently existsto encourage the incorporation ofrainwater harvesting systems intonewly constructed homes. The cityis considering extending rainwaterharvesting rebates to area home-builders; rebate amounts would likelycontinue to be based on the storagecapacity of rainwater cisterns up to amaximum rebate amount.

Newsletter used to reach cus-tomers. Customer communicationand awareness have long been a chal-lenge to the conservation program.

Despite ongoing awarenesscampaigns using utility billinserts and radio and newspa-per advertisements, many cus-tomers still know little aboutwater conservation. In March2004, the WCD began theWaterWise Newsletter to com-municate more regularly withcustomers and increase par-ticipation in water conserva-tion initiatives. Each month a

2007 © American Water Works Association

Water Conservation Division’s Bill

Hoffman escorts a tour group

through Samsung’s on-site water

reuse facilities. The recycled water

system supplies all of Samsung’s

landscape water, up to 125,000

gpd, and reduces wastewater

discharge by more than 250,000

mgd. The plant currently recycles

more than 60% of the water it uses.

84 FEBRUARY 2007 | JOURNAL AWWA • 99:2 | PEER-REVIEWED | GREGG ET AL

new issue of the newsletter is createdand distributed electronically tonearly 10,000 subscribers.

The newsletter facilitates cross-promotion of city programs byinforming customers who have par-ticipated in one program about otherprograms available and by alertingall subscribers to upcoming eventsand special offers. The newsletteralso includes related topics that maybe of interest to customers, includ-ing material on gardening, energyconservation, and water quality.

AUSTIN WATER UTILITY SEEKSNEW WAYS TO SAVE

Austin Water Utility is currentlyfaced with the need to expand treat-ment capacity by adding a fourth

water treatment plant to meet theexpected water demands of its grow-ing population. However, the envi-ronmental sensitivity of the proposedplant location and heightened con-cern for potential rate increases haveraised a lot of interest in the expan-sion plans.

To address stakeholder concerns,Austin Water Utility is working witha consulting firm to examine newand innovative ways to save water. TheWater Resources Planning Study willexamine the effectiveness of existingand potential conservation programsranging from incentive programs toenhanced communications and ordi-nance or policy changes. A number ofthe following programs were includedin the latest version of the city’s five-year

Water Conservation Plan and are indiscussion at this time.

Block rate for commercial proper-ties. The city of Austin commercialand multifamily water rates are cur-rently structured at peak and off-peak rates, unlike the increasingblock rate charged to residential cus-tomers. Implementing a conservationrate for commercial and multifam-ily properties’ irrigation accountscould potentially create a disincen-tive for outdoor overwatering andincrease property management over-sight of the irrigated area.

Water budgeting and conservationrate structures. Increasing block ratestructures discourage high water useby charging those with high useincreasingly greater amounts, butsuch structures are not well targetedbecause total landscaped area varieswidely among properties. For exam-ple, the amount one home uses towater to the evapotranspiration ratemay be three times as much as re-quired by the house next door. In ad-dition, some high-water-use cus-tomers are not sensitive to the pricesignals given by the rate structure.

One solution is to establish a waterbudget for each property on the basisof landscaped area and historical evap-otranspiration data. All customerswould be charged the same rate forwater if they stay within their definedwater budgets. Once a customer ex-ceeds the budget, he or she wouldencounter inclined block rates that aresteep enough to send a price signal toeven the most wasteful customer.

This approach was first intro-duced in the Irvine Ranch Water Dis-trict in Southern California and wasadopted by Boulder, Colo., inDecember 2004. Although the waterbudget approach requires an inten-sive data collection effort to calculatelandscape areas and the appropriateevapotranspiration amount, theequity of the system and the watersavings it produces may make itincreasingly popular.

Onsite water reuse. In some situa-tions it is both feasible and econom-ical to collect the condensate water

2007 © American Water Works Association

A sample of Austin’s WaterWise Newsletter, winner of multiple communications awards.

GREGG ET AL | PEER-REVIEWED | 99:2 • JOURNAL AWWA | FEBRUARY 2007 85

from air-conditioning units for reuseeither as feedwater for manufacturingprocesses or for irrigation. Severalbusinesses and institutions in Austinalready collect their condensate water,most notably the University of Texas.

Irrigation permitting. A city ofAustin study showed that homes withirrigation systems use an average of132 gpd more than those without irri-

gation systems (Strub et al, 1999).Water utilities throughout the coun-try are therefore justifiably concernedthat these inground systems operateas efficiently as possible. The city ofAustin could require rain shutoff sen-sors, five-day programmable con-trollers, pressure regulators (whereneeded), and head-to-head sprinklerspacing for all new systems.

Evapotranspiration irrigation con-trollers. Some cities are studying thepotential savings from evapotran-spiration controllers that automati-cally adjust the amount of waterapplied to the landscape on the basisof weather conditions. The “smart”evapotranspiration controller receivesradio, pager, or Internet signals withevapotranspiration information and

2007 © American Water Works Association

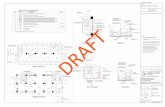

Savings AvoidedThrough Cost of

Peak Day Savings 2005 InfrastructureYear Inefficiency Program Per Measure gpd $3.48/gpd

1984 Excessive irrigation Watering restrictions Not quantified

1984 Excessive irrigation Xeriscape education 1 gpd/person 4,676 $16,272

1986–90 Inefficient shower heads Door-to-door retrofit Not quantified

1986–90 Inefficient toilets (existing) Door-to-door retrofit with dams Not quantified

1991 Inefficient toilets (new) City ordinance for 1.6 gpf 13.8 gpd/single family, 993,099 $3,455,984(6 Lpf) 15.2 gpd/multifamily,

26.0 gpd/commercial

1991–92 Inefficient fixtures (new) State and federal legislation No additional savings beyond 1991 city ordinance

1992 Excessive irrigation Irrigation audits 100 gpd/single family 483,500 $1,682,580

1993–present Inefficient toilets (existing) Incentives for retrofitting 13.8 gpd/single family, 1,424,163 $4,956,08715.2 gpd/multifamily,26.0 gpd/commercial

1993–present Inefficient shower heads Distribute free shower heads 7 gpd/fixture 197,428 $687,049

1994 Excessive irrigation Incentives for water-wise plants 100 gpd/property 75,900 $264,132

1994 Excessive commercial Revised commercial landscape 100 gpd/property 65,500 $227,940irrigation ordinance

1996 Water-inefficient Incentive to switch to efficient Dependent on savings 2,192,503 $7,629,910commercial processes processes achieved

1997 Irrigation water waste Provide free hose timers 5 gpd 26,040 $90,619

1998 Inefficient clothes washers Efficient clothes washer rebates 15 gpd/appliance 244,250 $849,990

1999 Irrigation water waste Ordinance prohibiting Not quantifiedwater waste

2000 Two-, three-, and four- Rule requiring separate meter for Not quantifieddwelling properties not new constructionseparately metered

2000 Commercial buildings not Rule requiring separate irrigation Not quantifiedmanaging water use meter for new construction

2001 Apartments not individually State submetering legislation Not quantifiedmetered

2001 Rainfall not collected Sell subsidized rain barrels; 49,177 $171,136offer rebates for larger systems 5.5 gpd/barrel; larger

systems dependent onstorage capacity

2003 Ultralow-flush toilets not Offer rebates for toilets that Reinforces previous retaining flush volumes maintain flush volume savings

2004 Restaurant water waste Distribute free spray rinse 200 gpd/spray valve 19,200 $66,816valves; conduct indoor and outdoor audits

2004 Limited customer Electronic newsletter founded N/A; boosts participation awareness in other programs

N/A—not applicable

TABLE 1 Summary of Austin water conservation efforts and success

86 FEBRUARY 2007 | JOURNAL AWWA • 99:2 | PEER-REVIEWED | GREGG ET AL

directs the irrigation system to replaceonly the moisture the landscape haslost to heat, humidity, and wind.Other evapotranspiration controllersuse historical data to adjust thewatering program.

However, unlike many conserva-tion measures (such as efficient toi-lets), evapotranspiration controllerscannot offer a guarantee of watersavings, and savings will vary basedon the total landscape area, land-scape type, prior watering habits, andirrigation equipment efficiency. Themonthly fees charged by some con-troller service providers may alsoreduce a customer’s financial savings.

Although evapotranspiration con-trollers take some of the guessworkout of watering, customers cannot “setit and forget it.” Evapotranspirationcontrollers still require initial sched-ule setup, monitoring, and adjustmentsto determine appropriate schedules.Additional testing is under way tomore accurately predict water savingsfrom evapotranspiration controllers.

Commercial rainwater and storm-water harvesting incentives. Rain-water and stormwater collection sys-tems at commercial and multifamilyproperties offer tremendous waterconservation potential. Unfortu-nately, the marginal cost of storingthis water makes it 20 times moreexpensive per gallon than potablewater. However, many multifamilyand commercial properties arealready required to collect and retainstormwater for 72 hours followinga rainfall event for water qualityand flood control reasons.

Retention ponds could also beused as a water source for irrigationand other nonpotable uses if the 72-hour requirement is relaxed. In addi-tion, inclusion of rainwater andstormwater collection into Austin’sGreen Building Program criteria givesdevelopers additional social andfinancial incentives to collect rain-water or stormwater.

CONCLUSIONSEach of Austin’s water conserva-

tion efforts has addressed distinctproblems using different methods:monetary incentives, equipment give-aways, subsidized sales, plumbingcode changes, ordinance enforce-ment, and new state and federal laws.These strategies have been promotedand enforced with the partnershipand cooperation of the water utility,the building code enforcementdepartment, and energy companies.These efforts have met with differ-ing degrees of success, as summa-rized in Table 1. Combined, how-ever, the water conservation efforts inAustin have contributed to a sub-stantial reduction in per capita wateruse (Figure 2).

Austin’s Water Conservation Pro-gram is as comprehensive as it istoday because of its 22-year historyof trial, error, revision, and evolu-tion. Austin continues to look fornew tools, new methods of savingwater, and new partners that can helpfurther its goals. It is hoped that thelessons learned from this long-run-ning program will be equally help-ful to communities beginning to

address water supply issues and tothose looking for ways to expandcurrent water conservation efforts.

ABOUT THE AUTHORSTony T. Gregg (towhom correspon-dence should beaddressed), is man-ager of AustinWater Utility’s Con-servation Division,

POB 1088, Austin, TX 78767;e-mail [email protected] has 26 years of civil engi-neering and planning experiencewith federal, state, and local gov-ernments, including demand andsupply side management, long-range water resource and waste-water reuse planning, policydevelopment, and management ofregulatory programs. He receiveda BS in civil engineering fromBucknell University in Lewisburg,Pa. Dan Strub is a conservationprogram coordinator, and DremaGross is a conservation programspecialist, both for Austin WaterUtility.

2007 © American Water Works Association

REFERENCESGauley, W. & Koeller, J., 2003. Maximum Per-

formance (MaP) Testing of Popular ToiletModels: A Cooperative Canadian andAmerican Project. Veritec ConsultingInc. and Koeller & Co.

Koeller, J., 2003. Dual-Flush Toilet Fixtures:Field Studies and Water Savings.www.cuwcc.org/Uploads/product/Dual_Flush_Fixture_Studies_03-12-17.pdf(accessed Dec. 13, 2006).

Mayer, P. et al, 2004. National Multiple FamilySubmetering and Allocation Billing Pro-gram Study. Aquacraft Inc., Boulder,Colo.

National Climatic Data Center, 2006. Com-parative Climatic Data for the UnitedStates Through 2005. National Oceanicand Atmospheric Administration,National Climatic Data Center.www.ncdc.noaa.gov (accessedDec. 8, 2006).

SBW Consulting Inc., 2004. Evaluation, Mea-surement, and Verification Report for theCUWCC Pre-Rinse Spray Head Distribu-tion Program. www.cuwcc.org/uploads/product/SBW_Final_EMV_Rprt_Phase_1_04-05-03.pdf (accessed Dec.13, 2006).

Strub, D. et al, 1999. Xeriscaping: Sowing theSeeds for Reducing Water Consumption.Report for Bureau of Reclamation, City ofAustin, Tex.

If you have a comment about thisarticle, please contact us at