Volume 55, Number 2 March/April 2002 Dirty Bombs: Response to a Threat · PDF fileDirty Bombs:...

Transcript of Volume 55, Number 2 March/April 2002 Dirty Bombs: Response to a Threat · PDF fileDirty Bombs:...

Dirty Bombs: Response to a Threat

Making Sense of Information RestrictionsAfter September 11By Steven Aftergood and Henry Kelly

Continued on page 6

In This Issue

1 Dirty Bombs: Response to aThreat

1 Making Sense of Informa-tion Restrictions AfterSeptember 11

3 The “War on Terror” andthe “War on Drugs”: AComparison

9 Results of the FAS MemberSurvey

11 FAS Staff News

The FAS Public Interest ReportThe FAS Public Interest Report (USPS188-100) is published bi-monthly at1717 K St. NW Suite 209, Washington, DC20036. Annual subscription is $50/year.Copyright©2002 by the Federation ofAmerican Scientists.

Archived FAS Public Interest Reportsare available online at www.fas.orgor phone (202) 546-3300, fax (202)

675-1010, or email [email protected].

Printed on 100% Recycled,100% Postconsumer Waste,Process Chlorine Free (PCF)

Board of DirectorsCHAIRMAN: Frank von HippelPRESIDENT: Henry KellyVICE-CHAIRMAN: Steven FetterSEC’Y-TREASURER: Harold A. Feiveson

MEMBERS:Ruth S. Adams Hazel O’LearyDavid Albright Jane OwenBruce Blair William RevelleHarold A. Feiveson Shankar SastryRichard Garwin Jonathan SilverMarvin L. Goldberger Gregory SimonKenneth N. Luongo Lynn R. SykesMichael Mann Gregory van der Vink

March/April 2002Volume 55, Number 2

Continued on page 2

Henry Kelly testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on March 6, 2002 onthe threat of radiological attack by terrorist groups. This excerpt is taken from the text of hiswritten testimony, based on analysis by Michael Levi, Robert Nelson, and Jaime Yassif,which can be found at www.fas.org.

Surely there is no more unsettling task than considering how to defend ournation against individuals and groups seeking to advance their aims by killing andinjuring innocent people. But recent events make it necessary to take almost incon-ceivably evil acts seriously. Our analysis of this threat has reached three principleconclusions:1. Radiological attacks constitute a credible threat. Radioactive materials that

could be used for such attacks are stored in thousands of facilities around theUS, many of which may not be adequately protected against theft by deter-mined terrorists. Some of this material could be easily dispersed in urban areasby using conventional explosives or by other methods.

The Bush Administration intro-duced a series of new restrictions onpublic access to government informa-tion following the terrorist attacks oflast year. Under the new policy,agencies have removed thousands ofpages from government web sites andwithdrawn thousands of governmentdocuments and technical reports frompublic libraries. In one case, govern-ment depository libraries around thecountry were ordered to destroy theircopies of a recently issued USGS CD-ROM on US water resources.

The new restrictions have alarmedscientists, public interest groups, andconcerned citizens because theyinterfere with the conduct of researchand limit legitimate access to informa-tion needed for public discussion of keypolicy issues. Continued growth ofrestrictions without any clear end insight creates understandable concern

that we are watching a veil of indis-criminate security descending onsignificant portions of the Americanpolicy process.

Without debating the merits ofany particular case, it is clear that thenew information restrictions have beenundertaken in a largely ad hoc fashion.While the unprecedented emergencyrequired quick action in the short term,the inconsistent and often arbitrarypolicies that have emerged are clearlynot satisfactory over the long term.While terrorist threats require reshap-ing some standards, they do not call forwholesale abandonment of existingprocesses and safeguards. Few of theissues raised are new. The challenge ofdrawing a line between what should beprotected and what should not has beenthe subject of years of debate that has

2

FAS Public Interest Report | March/April 2002

Board Of Sponsors* Sidney Altman Biology

* Philip W. Anderson Physics

* Kenneth J. Arrow Economics

* Julius Axelrod Biochemistry

* David Baltimore Biochemistry

Paul Beeson Medicine

* Baruj Benacerraf Immunology

* Hans A. Bethe Physics

* J. Michael Bishop Biology

* Nicolaas Bloembergen Physics

* Norman Borlaug Agriculture

* Paul Boyer Chemistry

Anne Pitts Carter Economics

* Owen Chamberlain Physics

Morris Cohen Engineering

* Stanley Cohen Biochemistry

Mildred Cohn Biochemistry

* Leon N. Cooper Physics

* E. J. Corey Chemistry

Paul B. Cornely Medicine

* James Cronin Physics

* Johann Deisenhofer Biology

Carl Djerassi Chemistry

Ann Druyan Writer/Producer

* Renato Dulbecco Microbiology

John T. Edsall Biology

Paul R. Ehrlich Biology

George Field Astrophysics

* Val L. Fitch Physics

Jerome D. Frank Psychology

* Jerome I. Friedman Physics

John Kenneth Galbraith Economics

* Walter Gilbert Biochemistry

* Donald Glaser Physics-Biology

* Sheldon L. Glashow Physics

Marvin L. Goldberger Physics

* Joseph L. Goldstein Medicine

* Roger C. L. Guillemin Physiology

* Herbert A. Hauptman Chemistry

* Dudley R. Herschbach Physics

Frank von Hippel Physics

* Roald Hoffmann Chemistry

John P. Holdren Public Policy

* David H. Hubel Medicine

* Jerome Karle Physical Chemistry

Nathan Keyfitz Demography

* H. Gobind Khorana Biochemistry

* Arthur Kornberg Biochemistry

* Edwin G. Krebs Pharmacology

About FASThe Federation of American Scientists (FAS), founded

October 31, 1945 as the Federation of Atomic Scientists

by Manhattan Project scientists, works to ensure that

advances in science are used to build a secure,

rewarding, environmentally sustainable future for all

people by conducting research and advocacy on science

public policy issues. Current weapons nonproliferation

issues range from nuclear disarmament to biological

and chemical weapons control to monitoring

conventional arms sales; related issues include drug

policy, space policy, and disease surveillance. FAS also

promotes learning technologies and limits on

government secrecy. FAS is a tax-exempt, tax-deductible

501(c)3 organization.

* Willis E. Lamb Physics

* Leon Lederman Physics

* Edward Lewis Medicine

* William N. Lipscomb Chemistry

Jessica T. Mathews Public Policy

Roy Menninger Psychiatry

Robert Merton Sociology

Matthew Meselson Biochemistry

Neal E. Miller Psychology

* Franco Modigliani Economics

* Mario Molina Chemistry

Philip Morrison Physics

Stephen S. Morse Virology

* Joseph E. Murray Medicine

Franklin A. Neva Medicine

* Marshall Nirenberg Biochemistry

* Douglas D. Osheroff Physics

* Arno A. Penzias Astronomy

* Martin L. Perl Physics

Gerard Piel Publisher

Paul Portney Economics

Mark Ptashne Molecular Biology

George Rathjens Political Science

* Burton Richter Physics

David Riesman, Jr. Sociology

* Richard J. Roberts Biology

Vernon Ruttan Agriculture

Jeffrey Sachs Economics

* J. Robert Schrieffer Physics

Andrew M. Sessler Physics

* Phillip A. Sharp Biology

Stanley K. Sheinbaum Economics

George A. Silver Medicine

* Herbert A. Simon Psychology

* Richard E. Smalley Chemistry

Neil Smelser Sociology

* Robert M. Solow Economics

* Jack Steinberger Physics

* Henry Taube Chemistry

* Charles H. Townes Physics

Myron E. Wegman Medicine

Robert A. Weinberg Biology

* Steven Weinberg Physics

* Torsten N. Wiesel Medicine

Alfred Yankauer Medicine

Herbert F. York Physics

* Nobel Laureate

EDITOR: Henry KellyPresident

ASSISTANT EDITOR: Karen KelleyOrganization Manager

Editorial Staff

“Information” Continued from page 1

Continued on page 12

resulted in a large and useful body oflaw and policy that governs informa-tion disclosure and provide safeguardsagainst abuse.

Recent steps taken by the adminis-tration have exceeded the authorityprovided by existing law and executiveorders. This situation must be quicklyremedied. The process of building anew system provides an opportunity toaddress several flaws in the existingsystem. The following issues deservecareful scrutiny:(i) How does the new threat of

terrorism affect the criteria forreleasing information?

(ii) Should separate release decisionsbe made concerning whether tokeep material classified andwhether to make it easily avail-able by putting it on the web?

(iii) What procedures can be adoptedto prevent abuse, and provideassurance that the people makingdecisions about releasing informa-tion are not withholding informa-tion to protect themselves frompublic scrutiny of their actions?

"Sensitive but Unclassified"Several of the new restrictions on

information are not congruent with theexisting legal framework defined by theFreedom of Information Act (FOIA), orwith the executive order that governsnational security classification anddeclassification. FOIA is the primaryinstrument giving the public the legalright of access to government informa-tion. It also provides legal authorizationfor the government to withholdinformation that fits within one ormore of its nine exemptions (e.g.,classified national security information,proprietary information, privacyinformation, etc.)

Perhaps the most serious exampleof deviation from existing standards canbe found in a March 19 White Housememorandum to executive branchagencies, urging them to withhold“sensitive but unclassified informationrelated to America’s homeland security.”

This is bad policy because no oneknows what it means. The meaning of“unclassified” is clear, of course, but thecrucial term “sensitive” is not defined.

This is a problem, because agencies mayhave many reasons for consideringinformation “sensitive” that havenothing to do with national security.They may wish to evade congressionaloversight, to shield a controversialprogram from public awareness, orotherwise manipulate the politicalsystem through strategic withholdingand disclosure of information.

The Administration has alsomoved to make a distinction betweenhard copy documents (deemed lesssensitive) and web-based documents(deemed more sensitive) that is notrecognized in law. No guidelines havebeen issued defining how to make thisdistinction or the basis for maintainingthe distinction, thereby giving thou-sands of individual governmentorganizations arbitrary authority toremove material from the web. Sincethere are no procedures for reviewingthese decisions, there are no protectionsfrom abuse.

Some agencies are attempting toimpose controls on documents thathave been declassified under properauthority and publicly released, whichis not permitted under current guide-lines (and which is probably futile).

Failure to provide a clear defini-tion of “sensitive but unclassifiedinformation” points to the need forgreater clarity in government informa-tion policy—a policy that encompasseslegitimate security concerns whileupholding the virtues of public disclo-sure.

Start Making SenseCrafting a new policy that

responds to the sometimes competinginterests in security and public accessshould not be an extraordinarilydifficult task.

In the first place, most govern-ment information will be self-evidentlysubject to disclosure under the Freedomof Information Act, or else clearlyexempt from disclosure under theprovisions of that law. These are easycases where the proper legal course ofaction is obvious.

But there will be certain types ofinformation that form an ambiguousmiddle ground, to which the law has

3

FAS Public Interest Report | March/April 2002

The “War on Terror” and the “War on Drugs”:A Comparison

Continued on page 4

By Mark A. R. Kleiman, Peter Reuter, and Jonathan P. Caulkins

The problem of large-scaleterrorism aimed at targets within theUnited States is new. It is much tooearly to judge how permanent theproblem is: whether the September 11attacks will be seen in retrospect asmaking a phase change in the level ofdomestic risk from such acts, or insteadstand out like the Chicago fire or theGalveston flood, not as a precedent butas a one-time event. (To some extent,that may be determined by the ad-equacy of the policy response.)

The effort to prevent repetitions ofthe September 11th incidents has begunto be called “the war on terror.” Thissuggests analogies to the “war on drugs,”and there have been attempts to usethese comparisons to draw conclusionsabout the appropriate shape and likelysuccess of the anti-terrorism campaigns.

The counter-drug experienceholds at least three useful lessons forpolicy makers:

1. Enforcement strategies are verydifferent: Drug dealers havecustomers; terrorists have support-ers and victims. Drug organiza-tions are mostly anonymous andinterchangeable, thus making theremoval of any one, or even anysmall number, of limited useful-ness. Terrorist organizationsappear to be highly individual andmay take a long time to replace, sothat the removal of even one, suchas Al-Quaeda, might make a largedifference to the threat faced inthe United States. The largelysuccessful campaign against theAmerican Mafia — a campaignagainst a specific group of organi-zations, rather than against a classof activities — may provide muchmore insight into successful anti-terrorist policy than does themore diffuse and less successfuldrug enforcement effort;

2. Border control is both necessaryand limited, but is unlikely to bethe key to preventing terrorism.Sealing the borders against tons of

cocaine and heroin has provenimpossible. Border interdiction islikely to be even less successfulagainst explosive devices, nuclearmaterials, or biological weaponswhere the threats are measured inkilograms, or even grams. Detect-ing tens or hundreds of terroristsamong millions of border-crossersis likely to prove no easier.

3. Coordination problems areimmense, not to be solved bymerely naming a “czar.” The drugczar has been able to affect federaldrug policy only marginally,partly because of budgetaryobstacles and Congressionalfragmentation. Inducing agencieswith very different missions andcultures, reporting to differentlevels of government, to worktogether will never be easy, andCabinet rank is a poor substitutefor money and authority.

Crime Control and EnforcementTerror has victims, and sponsors,

rather than consumers. Thus there is noclear analogy in the counter-terrorefforts to “demand reduction” efforts asin drug control policy. Instead ofreducing demand, counter-terror policyhas the possibility of hardening targets,such as reinforcing cockpit doors.However, terrorist organizations, likedrug dealers, are capable of adapting tocontrol efforts mounted against them.

Drug enforcement attacks ongoingactivity. Investigative targets have solddrugs many times before, they hope tocontinue doing so on a regular (in somecases daily) basis, and the next drugtransaction typically looks a lot like thelast one. Counter-terror operations seekto arrest activity before it occurs, andare constrained by the need to stop anyknown future action that might riskpersonal injury. By contrast, under-cover drug investigations routinelycontinue while the organizations undersurveillance deliver drugs to customers.

An essential contribution ofundercover drug investigations is

making drug market participantssuspicious of strangers who claiminterest in transacting drugs. Theexistence of undercover operationshampers all drug operations, not justthose directly targeted. Even if enforce-ment agencies have trouble penetratingterrorist cells, aggressive efforts to do somay hamper cooperation among cellsby making them suspicious of strangers.

Drug distribution networks arerobust to enforcement because they arenetworks rather than monoliths orhierarchies. The “new” terroristorganizations are reported to have moreof a network structure, so they may bemore resilient than the “classical”terrorist organizations of the 70’s and80’s, but they are still more verticallyand horizontally integrated, and to thatextent more vulnerable, than are drugdistribution networks.

Dismantling one drug traffickingorganization benefits others by elimi-nating competition for markets.Enforcement can take advantage of this,either by getting one group to informagainst the other or by making inter-group (or intragroup) violence the targetof investigative efforts. There is ingeneral no comparable incentive fordifferent terrorist organizations or cellsto interfere with each other.

Among enforcement activities,counter-terror may resemble traditionalorganized crime enforcement moreclosely than it does drug enforcement.Organized crime enforcement pros-ecutes people for labor racketeering,gambling, prostitution, etc. It is notaimed at those illicit industries, but at asmall list of organizations, each with afinite, though changing, list of mem-bers. By contrast with the standoff inthe “war on drugs,” organized crimeenforcement campaigns in the past havebeen substantially successful.

Incapacitation and ReplacementThere is little prospect of affecting

the supply of drugs through incapacita-tion. There may be much more promise

4

FAS Public Interest Report | March/April 2002

“Drugs and Terror” Continued from page 3

in the removal of a relatively smallnumber of terrorists.

In the instance of drugs, low- andmid-level operatives have proven to bealmost infinitely replaceable. Bycontrast with “predatory” crimes suchas burglary, the incapacitation effect ofimprisoning a drug dealer is close tozero. Even high-level drug dealers andentire dealing organizations haveproven to be replaceable, with at most abrief supply interruption.

Whether these statements are trueof terror operatives attacking targets inthe United States is an open question,but it is easy to believe that they are not,especially when it comes to suicideoperations. Despite its ample funding,al-Qaeda mounted no more than onesuccessful operation every year or so.Nor is there a “demand” for terroristacts in the sense that there is a demandfor heroin, so there is no mechanismthat automatically replaces terrorists asthe market more or less automaticallyreplaces drug retailers.

The requisites for a successfulterrorist operation would seem to be (1)knowledge of how to create damage oringenuity in developing new methodsof doing so; (2) access to the requisitematerial means; (3) a supply of opera-tives willing to kill (and perhaps die);(4) money, or the ability to raise moneyand move it around internationally; (5)organization capable of putting theserequisites together to actually carry outoperations across borders; and (6)motivation, either intrinsic or extrinsic.The combination of these might provehard to reproduce; if so, a terrorist groupdismantled by enforcement might notbe replaced.

In deterring drug dealing, thescarce resource is the ability to incarcer-ate, not the ability to arrest. Theopposite is true of terrorism. More thana million Americans sold cocaine in thelast 12 months. Locking up all of themwould be extraordinarily expensive.Locking up all of the individuals in theUS who are working to commit lethalterrorist attacks would, by contrast, putno strain on the prison system. Theproblem is catching them, not holdingthem.

Source Country Control and In-terdiction

Offshore production locationsare an important resource for cocaineand heroin production, but they arehard to shut down and easy to replace.There may be greater promise in“source-country” operations againstterrorist groups.

Drug crops can potentially begrown almost anywhere, and evensincere efforts by source-countrygovernments may be unable to preventsuccessful cultivation for export. Thenumber of viable source countries forterrorism may be smaller than for drugs.Though recruiting and training terror-ists does not depend on large areas orspecific climates, it may need theacquiescence, perhaps even complicity,of the host government, rather thanmerely weakness. Fewer countries maywish to offer such protection — espe-cially in light of recent events inAfghanistan — than are prepared topassively tolerate drug production. U.S.actions in Afghanistan also demonstratethat the respect for foreign sovereigntiesthat constrains counter-drug actionsdoes not limit counter-terrorist actionsto anything like the same extent.

The counter-drug experienceshows that border control can play asupporting role in the effort to protectthe United States from terrorist threats.On the order of 300 metric tons ofcocaine, and some multiple of thatamount of marijuana, enter the US eachyear. Those quantities are a minusculefraction of the corresponding numbersfor legitimate commerce; the difficultyof interdiction rises with the size of thelegitimate flows of persons and goods,because the needle of contrabandshipments are hard to find in thehaystack of licit commerce. Theproblem for terrorism control at theborder is even greater, because thedifficulty of detection rises as thematerials get more compact. That makestoxins and infectious agents especiallythreatening, and intelligence-based (asopposed to random) search especiallyvaluable.

Acceptable leakage rates are muchlower for terrorism than for drugs.Stopping 90% of the drugs entering the

US would be a spectacular success, butletting 10% of attempted major terroristacts succeed would be a disaster. Theratio of potential social damage toweight or bulk is much higher forexplosives and toxins, and incalculablyhigher for infectious agents, than it isfor drugs. Tracing a shipment of drugsto the recipient often involves lettingthe delivery be consummated, increas-ing the chances that an attemptedshipment will result in an arrest, ratherthan merely the loss of materials. Thefault-intolerant climate of anti-terrorefforts makes “controlled deliveries”much more troublesome for terroristmaterials than they are for drug ship-ments. That reduces the value of bordercontrols in identifying and arrestingterrorists.

The existence of “dual-use”materials, whether fertilizer in theOklahoma City blast or box-cutters andairliners on September 11, raises thesame problem; the threat does not standout from the background.

Money MattersInternational terrorism, like drug

dealing, involves moving moneyaround, but the sums are of differentorders of magnitude. The September 11actions are estimated to have cost abouthalf a million dollars, which is roughlynine minutes’ revenues in the UScocaine market. The direction of flow isalso different. Money in the drugbusiness all moves up from the custom-ers first to low-level dealers, then up thedomestic supply chain, and eventually(in much smaller amounts) to overseassuppliers. Money flows in the terrorbusiness are more complicated, and thefoot soldiers are likely to receivepayment from above rather thansending dollars up the chain.

Moving drug money is likemoving drugs. It is costly and, moreimportantly, creates enforcementvulnerability. But money launderinginvestigations cannot cut drug traffick-ers off from their source of money,which is their customer base. Sinceterrorism per se expends money, ratherthan making it, it is conceivable thatcontrols on money movements couldconstrain terrorist operations.

5

FAS Public Interest Report | March/April 2002

Even if it were true that we have failed in the“war on drugs,” that would not imply theinevitable failure of the attempt to suppressterrorist actions.

The Coordination ProblemBoth the drug problem and the

terror problem involve foreign residentsand foreign nationals damaging USinterests by actions taken both here andabroad. This means that the US govern-ment can benefit from actions taken byforeign governments. How to balanceunilateral, bilateral, and multilateralefforts is a problem in both areas; theoptimal mix is not the same in the twocases.

The cross-jurisdictional chal-lenges, substantial for drug control, areeven greater for terrorism control.Terrorist organizations transcendjurisdictional boundaries more than doindividual drug organizations. No oneinternational drug organizationoperates in more than a handful ofcountries, and no domestic drugorganization operates in more than ahandful of cities. If al-Qaeda is viewedas one organization, not as a movementcomposed of separate organizations,then its geographic reach is extensive.

With some difficulty, joint federal-local task forces have been created topool information about investigationsof drug operations that span localjurisdictional boundaries. Efforts thathave been made with foreign enforce-ment agencies have been more tentativeand always involve some operationalrisk. Something parallel, but grander,may be needed to effectively poolcounter-terror investigation informa-tion.

The coordination problemextends beyond coordinating investiga-tive agencies. Consider the failuresrevealed by the September 11 opera-tions. More than a dozen intelligenceagencies failed to detect a plot tocircumvent FAA security proceduresthat were implemented by privatecontractors at municipally operatedairports in order to seize commercialairliners to crash into national icons,creating disasters responded to bymultiple city, county, state, federal, andnon-profit emergency response teams.

The Office of National DrugControl Policy is charged with coordi-nating the nation’s counter-drug efforts,but it largely lacks the power andauthority to alter the budgets or actions

of the various federal agencies, let alonethe state and local agencies. The drugczar is in fact not a czar. Nor is that theresult of poor statutory drafting; theagencies whose activity the “drug czar”is supposed to coordinate, and theappropriations subcommittees whohandle their budgets, prize theirautonomy. Giving a homeland defenseczar powers adequate to his mission willnecessarily bring him into conflict withhis cabinet peers, their key subordi-nates, and their Congressional support-

ers, and the public interest will not lieentirely on either side of those conflicts.

Proposals to combine variouselements and responsibilities of theCustoms Service, Immigration andNaturalization Service, and otheragencies into a single Border ControlAgency have apparently already fallenvictim to the interagency politicalprocess. It is hard to judge from outsidewhether that result is better or worsethan its alternatives.

ConclusionsOne way to make new problems

seem familiar is to seek out analogies.That is both a natural psychologicalresponse and a rational analyticalstrategy. The similarities between theproblems of illicit drug distribution andforeign-based terrorist activity go deeperthan the “war” metaphor. In each case,the problem is both important andsomewhat inchoate. In each case, theproblem has both domestic andtransnational aspects. In each case, lawenforcement is indispensable but notitself a complete solution. In each case,there is great difficulty in eitheraccepting an ongoing high level ofdamage or in formulating a strategy tobring that damage down to a level thatseems acceptable. In each case, thetendency to think that tougher is bettermay not be justified by results. In eachcase, there is both great need and great

difficulty in coordinating efforts acrossgovernments, across levels of govern-ment, across agencies, among disci-plines, and across the public, private,and civic sectors.

However, terrorism is also unlikedrug distribution in vital ways: thescale of the activity to be suppressed; thestructure of the organizations whoseschemes we must try to foil; the motiva-tions of their participants; the scale,structure, and direction of the relatedfinancial transactions; and the tolerance

for failure. Even if it were true that wehave failed in the “war on drugs” (aproposition that cannot be properlyevaluated without more careful specifi-cation of standards and alternativesthan is usually employed), that wouldnot imply the inevitable failure of theattempt to suppress terrorist actions. Bythe same token, we cannot simply“port” successful strategies and tactics,or evaluative techniques, from drugpolicy to terrorism control. “As our caseis new, we must think anew, and actanew.” PIR

The Authors:Peter Reuter is Professor of Public

Affairs and Criminology at the Universityof Maryland and editor of the “Journal ofPolicy Analysis and Management.” He wasthe founding co-director of the RAND DrugPolicy Research Center and is the co-authorwith Rob MacCoun of Drug War Heresies.

Mark Kleiman is Professor of PolicyStudies at UCLA and editor of the “DrugPolicy Analysis Bulletin.” He and PeterReuter are co-chairs of the FAS drug policyprogram.

Jonathan Caulkins is Professor ofOperations Research and Public Policy atCarnegie Mellon University. He won the1999 Kershaw Award, given every two yearsby the Association for Public PolicyAnalysis and Management to recognizedistinguished contributions to the field ofpublic policy analysis by researchers underthe age of 40.

6

FAS Public Interest Report | March/April 2002

2. While radiological attacks wouldresult in some deaths, they wouldnot result in the hundreds ofthousands of fatalities that couldbe caused by a crude nuclearweapon. Attacks could contami-nate large urban areas withradiation levels that exceed EPAhealth and toxic material guide-lines.

3. Materials that could easily be lostor stolen from US researchinstitutions and commercial sitescould contaminate tens of cityblocks at a level that wouldrequire prompt evacuation andcreate terror in large communitieseven if radiation casualties werelow. Areas as large as tens ofsquare miles could be contami-nated at levels that exceedrecommended civilian exposurelimits. Since there are often noeffective ways to decontaminatebuildings that have been exposedat these levels, demolition may bethe only practical solution. If suchan event were to take place in acity like New York, it would resultin losses of potentially trillions ofdollars.

BackgroundSignificant amounts of radioactive

materials are stored in laboratories, foodirradiation plants, oil drilling facilities,medical centers, and many other sites.Cobalt-60 and cesium-137 are used infood disinfection, medical equipmentsterilization, and cancer treatments.During the 1960s and 1970s the federalgovernment encouraged the use ofplutonium in university facilitiesstudying nuclear engineering andnuclear physics. Americium is used insmoke detectors and in devices that findoil sources.

With the exception of nuclearpower reactors, commercial facilities donot have the types or volumes ofmaterials usable for making nuclearweapons. Facility owners provideadequate security when they have avested interest in protecting commer-cially valuable material. However, onceradioactive materials are no longer

needed and costs of appropriate disposalare high, security measures become lax,and the likelihood of abandonment ortheft increases.

We must wrestle with the possibil-ity that sophisticated terrorist groupsmay be interested in obtaining thesematerials and with the enormousdanger to society that such thefts mightpresent. Significant quantities ofradioactive material have been lost orstolen from US facilities during the pastfew years and thefts of foreign sourceshave led to fatalities. In the US, sourceshave been found abandoned in scrapyards, vehicles, and residential build-ings.

If these materials were dispersedin an urban area, they would pose aserious health hazard. Intense sourcesof gamma rays can cause acute radiationpoisoning, or even fatalities at highdoses. Long-term exposure to low levelsof gamma rays can cause cancer. If alphaemitters, such as plutonium, americiumor other elements, are present in theenvironment in particles small enoughto be inhaled, these particles canbecome lodged in the lungs and damagetissue, leading to long-term cancers.

Case StudiesWe have chosen three specific

cases to illustrate the range of impactsthat could be created by malicious use ofcomparatively small radioactivesources: the amount of cesium that wasdiscovered recently abandoned inNorth Carolina, the amount of cobaltcommonly found in a single rod in afood irradiation facility, and the amountof americium typically found in oil welllogging systems. The impact would be

much greater if the radiological devicein question released the enormousamounts of radioactive material foundin a single nuclear reactor fuel rod, butit would be quite difficult and dangerousfor anyone to attempt to obtain and shipsuch a rod without death or detection.The Committee will undoubtedly agreethat the danger presented by modestradiological sources that are compara-tively easy to obtain is significant aswell.

The impact of radioactive materialrelease in a populated area would varydepending on a number of factors, suchas the amount of material released, thenature of the material, the details of thedevice that distributes the material, the

direction and speed of the wind, otherweather conditions, the size of theparticles released (which affects theirability to be carried by the wind and tobe inhaled), and the location and size ofbuildings near the release site. Uncer-tainties inherent in the complex modelsused in predicting the effects of aradiological weapon mean that it is onlypossible to make crude estimates ofimpacts; the estimated damage we showmight be off by an order of magnitude.

In all three cases we have assumedthat the material is released on a calmday (wind speed of one mile per hour)and that the material is distributed byan explosion that causes a mist of fineparticles to spread downwind in acloud. People will be exposed toradiation in several ways.

� They will be exposed to materialin the dust inhaled during theinitial passage of the radiationcloud, if they have not been ableto escape the area before the dust

“Dirty Bombs” Continued from page 1

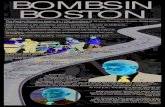

Figure 1. Long-term ContaminationDue to Cesium Bomb inWashington, DC

Inner Ring: One cancer death per 100people due to remaining radiation

Middle Ring: One cancer death per1,000 people due to remainingradiation

Outer Ring: One cancer death per10,000 people due to remaining ra-diation; EPA recommends decontami-nation or destruction

7

FAS Public Interest Report | March/April 2002

cloud arrives. We assume thatabout twenty percent of thematerial is in particles smallenough to be inhaled. If thismaterial is an alpha emitter, it willstay in the body and lead to longterm exposure.

� Anyone living in the affected areawill be exposed to materialdeposited from the dust that settlesfrom the cloud. If the materialcontains gamma emitters, resi-dents will be continuouslyexposed to radiation from thisdust. If the material contains alphaemitters, dust that is pulled off theground and into the air by wind,automobile movement, or otheractions will continue to beinhaled, adding to exposure.

� In a rural area, people would alsobe exposed to radiation fromcontaminated food and watersources.

The EPA has a series of recommen-dations for addressing radioactivecontamination that would likely guideofficial response to a radiological attack.Immediately after the attack, authoritieswould evacuate people from areascontaminated to levels exceeding thoseguidelines. People who received morethan twenty-five times the thresholddose for evacuation would have to betaken in for medical supervision.

In the long term, the cancerhazard from the remaining radioactive

contamination would have to beaddressed. Typically, if decontaminationcould not reduce the danger of cancerdeath to about one-in-ten-thousand, theEPA would recommend the contami-nated area be eventually abandoned.Several materials that might be used in aradiological attack can chemically bindto concrete and asphalt, while othermaterials would become physicallylodged in crevices on the surface ofbuildings, sidewalks and streets.Options for decontamination wouldrange from sandblasting to demolition,with the latter likely being the onlyfeasible option. Some radiologicalmaterials would also chemically bind tosoil in city parks, with the only disposalmethod being large scale removal ofcontaminated dirt. In short, there is ahigh risk that the area contaminated bya radiological attack would have to bedeserted.

Example 1:Cesium (Gamma Emitter)

Two weeks ago, a lost medicalgauge containing cesium was discoveredin North Carolina. Imagine that thecesium in this device was exploded inWashington, DC in a bomb using tenpounds of TNT. The initial passing of theradioactive cloud would be relativelyharmless, and no one would have toevacuate immediately. However,residents of an area of about five cityblocks, if they remained, would have aone-in-a-thousand chance of getting

cancer. A swath about one mile longcovering an area of forty city blockswould exceed EPA contamination limits,with remaining residents having a one-in-ten thousand chance of gettingcancer. If decontamination were notpossible, these areas would have to beabandoned for decades. If the devicewas detonated at the National Gallery ofArt, the contaminated area mightinclude the Capitol, Supreme Court, andLibrary of Congress, as seen if Figure 1.

Example 2:Cobalt (Gamma Emitter)

Now imagine if a single piece ofradioactive cobalt from a food irradia-tion plant were dispersed by an explo-sion at the lower tip of Manhattan.Typically, each of these cobalt “pencils”is about one inch in diameter and onefoot long, with hundreds of such piecesoften being found in the same facility.Admittedly, acquisition of such materialis less likely than in the previousscenario, but we still consider theresults, depicted in Figure 2. Again, noimmediate evacuation would benecessary, but in this case, an area ofapproximately one-thousand squarekilometers, extending over three states,would be contaminated. Over an area ofabout three hundred typical city blocks,there would be a one-in-ten risk ofdeath from cancer for residents living inthe contaminated area for forty years.

Figure 2. Long-term Contamination Dueto Cobalt Bomb in NYC -EPA Standards

Inner Ring: One cancer death per 100people due to remaining radiation

Middle Ring: One cancer death per 1,000people due to remaining radiation

Outer Ring: One cancer death per 10,000people due to remaining radiation; EPA rec-ommends decontamination or destruction

Figure 3. Contamination Due to CobaltBomb in NYC - Chernobyl Comparison

Inner Ring: Same radiation level as per-manently closed zone around Chernobyl

Middle Ring: Same radiation level as per-manently controlled zone around Chernobyl

Outer Ring: Same radiation level as peri-odically controlled zone around Chernobyl

Continued on page 8

�

�

8

FAS Public Interest Report | March/April 2002

The entire borough of Manhattan wouldbe so contaminated that anyone livingthere would have a one-in-a-hundredchance of dying from cancer caused bythe residual radiation. It would bedecades before the city was inhabitableagain, and demolition might be neces-sary.

For comparison, consider the 1986Chernobyl disaster, in which a Sovietnuclear power plant went through ameltdown. Radiation was spread over avast area, and the region surroundingthe plant was permanently closed. Inour current example, the area contami-nated to the same level of radiation asthat region would cover much ofManhattan, as shown in Figure 3.Furthermore, near Chernobyl, a largerarea has been subject to periodiccontrols on human use such as restric-tions on food, clothing, and time spentoutdoors. In the current example, theequivalent area extends fifteen miles.

Example 3:Americium (Alpha Emitter)

If a typical americium source usedin oil well surveying were blown upwith one pound of TNT, people in aregion roughly ten times the area of theinitial bomb blast would requiremedical supervision and monitoring, asdepicted in Figure 4. An area thirtytimes the size of the first area (a swathone kilometer long and covering twenty

city blocks) would have to be evacuatedwithin half an hour. After the initialpassage of the cloud, most of theradioactive materials would settle to theground. Of these materials, some wouldbe forced back up into the air andinhaled, thus posing a long-term healthhazard, as illustrated by Figure 5. A ten-block area contaminated in this waywould have a cancer death probabilityof one-in-a-thousand. A region twokilometers long and covering sixty cityblocks would be contaminated in excessof EPA safety guidelines. If the buildingsin this area had to be demolished andrebuilt, the cost would exceed fiftybillion dollars.

RecommendationsA number of practical steps can be

taken that would greatly reduce therisks presented by radiological weapons.Since the US is not alone in its concernabout radiological attack, and since weclearly benefit by limiting access todangerous materials anywhere in theworld, many of the measures recom-mended should be undertaken asinternational collaborations.

1. Reduce access to radioactivematerials

Measures needed to improve thesecurity of facilities holding dangerousamounts of these materials will increasecosts. In some cases, it may be worth-while to pay a higher price for increasedsecurity. In other instances, however,

the development of alternative tech-nologies may be the more economicallyviable option. Specific security stepsinclude the following:

Fully fund material recovery andstorage programs. Hundreds of pluto-nium, americium, and other radioactivesources are stored in dangerously largequantities in university laboratories andother facilities. In all too many casesthey are not used frequently, resultingin the risk that attention to theirsecurity will diminish over time. At thesame time, it is difficult for the custodi-ans of these materials to dispose of themsince in many cases only the Depart-ment of Energy (DoE) is authorized torecover and transport them to perma-nent disposal sites. The DoE Off-SiteSource Recovery Project, which isresponsible for undertaking this task,has successfully secured over three-thousand sources and has moved themto a safe location. Unfortunately, theinadequate funding of this programserves as a serious impediment tofurther source recovery efforts. Thisprogram should be given the neededattention and firm goals should be setfor identifying, transporting, andsafeguarding all unneeded radioactivematerials.

Review licensing and securityrequirements and inspection procedures forall dangerous amounts of radioactivematerial. Human Health Services, theDoE, the Nuclear Regulatory Commis-

Figure 4. Immediate Effects Due to Americium Bomb in New York City

Inner Ring: Everyone must receive medical supervision

Middle Ring: Maximum annual dose for radiation workers exceeded

Outer Ring: Area should be evacuated before radiation cloud passes

“Dirty Bombs” Continued from page 7

Figure 5. Contamination Due to Americium Bomb in New York City.

Inner Ring: One cancer death per 100 people due to remaining radiation

Middle Ring: One cancer death per 1,000 people due to remaining radiation

Outer Ring: One cancer death per 10,000 people due to remaining radiation;EPA recommends decontamination or destruction

9

FAS Public Interest Report | March/April 2002

Continued on page 10

sion and other affected agencies shouldbe provided with sufficient funding toensure that physical protection mea-sures are adequate and that inspectionsare conducted on a regular basis. Athorough reevaluation of securityregulations should be conducted toensure that protective measures apply toamounts of radioactive material thatpose a homeland security threat, notjust those that present a threat ofaccidental exposure.

Fund research aimed at findingalternatives to radioactive materials. Aresearch program aimed at developinginexpensive substitutes for radioactivematerials in functions such as foodsterilization, smoke detection, and oilwell logging should be created andprovided with adequate funding.

2. Early Detection

Expanded use of radiation detectionsystems. Systems capable of detectingdangerous amounts of radiation arecomparatively inexpensive and unob-trusive. The Office of HomelandSecurity should act promptly to identifyall areas where such sensors should beinstalled, ensure that information fromthese sensors is continuously assessed,

Just In! Results of theFAS Member Survey

In early 2002, FAS conducted asurvey of our members. Our purposewas to better understand memberinterests, document expertise, andengage members in helping affirm oldpriorities and set new ones.

The survey’s results profile ahighly educated membership with in-depth expertise in such sciences asphysics, biology, and chemistry, andwho work either full-time in these fieldsor are retired from positions in aca-demic institutions. FAS members sharethe concerns of civil rights, environ-mental, and human rights organiza-tions, and are active supporters ofEnvironmental Defense, the NaturalResources Defense Council, the ACLU,People for the American Way, andHuman Rights Watch. The largestpercentage of our members joined FASin the 1970s. When asked how mem-bers came to join FAS, 60% said thatthey had “known about FAS forever.”While half of FAS’ responding membersare over 70 years of age, a growingnumber of individuals under the age of50 are joining up. We were pleased tolearn that 68% of our members find thePublic Interest Report “informative,timely and relevant;” 20% agreed thatthe PIR “is perfect as is;” and 19% wouldlike us to cover more energy andenvironmental issues.

FAS’ members are a group withmutual concerns, common back-grounds, and scientific interests. Theirsurvery responses do differ, though.Let’s take a closer look.

“My fields of expertise are . . .”FAS was founded by physicists

working on the Manhattan Project in1945 and was known back then as the“scientists lobby” and the socialconscience of the nation’s scientists.When we asked members to identify thefields in which they worked, sciencessuch as physics, biology and engineer-ing outnumbered the fields of foreignpolicy, economics, law and finance.Nearly 30% of survey respondentsidentified themselves as physicists. The

and ensure adequate maintenance andtesting. High priority should be given tokey points in the transportation system,such as airports, harbors, rail stations,tunnels, highways. Routine checks ofscrap metal yards and land fill siteswould also protect against illegal oraccidental disposal of dangerousmaterials.

Fund research to improve detectors. Aprogram should be put in place to findways of improving upon existingdetection technologies as well asimproving plans for deployment ofthese systems and for responding toalarms.

3. Effective Disaster response

An effective response to a radio-logical attack requires a system capableof quickly gauging the extent of thedamage, identifying appropriateresponders, developing a coherentresponse plan, and getting the necessarypersonnel and equipment to the siterapidly.

First responders and hospitalpersonnel need to understand how to protectthemselves and affected citizens in the

FAS Conclusions

Radiological attacks constitute a credible threat. Radioactive materials that could be usedfor such attacks are stored in thousands of facilities around the US, many of which may notbe adequately protected against theft by determined terrorists. Some of this material couldbe easily dispersed in urban areas by using conventional explosives or by other methods.

Radiological attacks would not result in the hundreds of thousands of fatalities that could becaused by a crude nuclear weapon, though they could contaminate large urban areas.

Materials that could easily be lost or stolen could contaminate tens of city blocks at a levelthat would require prompt evacuation and create terror in large communities even ifradiation casualties were low. But, since there are often no effective ways to decontami-nate buildings that have been exposed at these levels, demolition may be the only practicalsolution.

FAS Recommendations

Reduce access to radioactive materials1. Fully fund material recovery and storage programs.2. Review licensing and security requirements and inspection procedures for all dangerousamounts of radioactive material.3. Fund research aimed at finding alternatives to radioactive materials.

Early Detection1. Expanded use of radiation detection systems.2. Fund research to improve detectors.

Effective Disaster response1. First responders and hospital personnel need to understand how to protect themselvesand affected citizens.2. Research into cleanup of radiologically contaminated cities.

Continued on page 10

10

FAS Public Interest Report | March/April 2002

“Survey” Continued from page 9

next largest fields represented weremedicine (18%), biology (15%), engi-neering (15%) and chemistry (13%).

It is especially interesting tocompare fields represented by FAS

earliest members with more recentmembers. Nearly half of FAS memberswho joined before 1955 are physicists.FAS newest members, who joined since2000, are also physicists (21%), but 29%said their field of expertise is nationalsecurity, 25% said aerospace, and 22%said computer science. This reflectssignificant growth in security-relatedfields over the past decades—and anincreasingly diverse membership.Other fields were environmentalscience, psychology, public policy,finance, law and transportation. Nearlyhalf of responding members work innonprofit or academic institutions asopposed to private industry (13%) or ingovernment (8%).

“The highest level of education Ihave attained is . . .”

FAS continues to attract highlyeducated scholars and analysts, and thecomposition of members’ level ofeducation does not change as the fieldsof expertise do from one age group toanother. Among all respondents, 63%have Ph.Ds. Individuals with profes-sional doctoral degrees such as doctorsor lawyers account for 14%. A master’sdegree is the highest level of educationattained by 12%, and 7% have abachelor’s degree. Two percent ofmembers are high school students orgraduates. These two latter goups areour most recent members, having cometo us through our website.

“Go to <www.fas.org> . . .”In addition to giving access to

technical information and policyanalysis, the FAS website is our mosteffective member recruitment tool.Since 2000, 85% of FAS newest membersjoined over the web. More than half ofthese members also use the website oncea month; more than a third use it everyweek. The survey also shows thatamong FAS’ earliest members (memberswho joined between 1945 and 1970),43% use the website once a month orless. For members who joined in the1980s and 90s, we see a modest increasein members’ use (46%). Only 7% of ourmembers have no access to the Internet.

The feature of the website that FASmembers use most often are the techni-cal details about weapons technologiesand arms control treaties, and thecountry-by-country weapons sales andpossessions tables. Eighteen percentrefer to the site for this information,while 15% use the site to keep up to dateon FAS findings and projects. This doesnot capture the hundreds of thousandsof hits that the website receives dailyfrom non-member users. Surprisingly,one third of our members were notaware of the site at all.

“I subscribe to . . .”The survey offered members a

wide range of choices of journals andtrade magazines, including Bulletin ofAtomic Scientists, Foreign Affairs,Fortune, Time, Science, ScientificAmerican, and US News and WorldReport. By far, the most subscribed tomagazines were Science (48%) andScientific American (36%). Subscribersto the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists andNew Scientists each account for 21% ofmember respondents. While subscrip-tion to Science and Scientific Americanis steady among FAS members through-out the generations, only 6% of ourmost recent members subscribe to theBulletin.

“I am also a member of . . .”Our survey shows that FAS

members live up to their reputation asscientists with a conscience. Theysupport numerous causes, working toprotect the world’s environmentalresources, eliminate weapons of mass

Based on survey re-sults, [FAS] members’priorities are right ontarget with FAS’agenda.

event of a radiological attack and beable to rapidly determine if individualshave been exposed to radiation. Thereis great danger that panic in the event ofa radiological attack on a large citycould lead to significant casualties andseverely stress the medical system.While generous funding has been madeavailable for this training, the programappears in need of a clear managementstrategy. Dozens of federal and stateorganizations are involved, and it is notclear how materials will be certified oraccredited.

Research into cleanup of radiologi-cally contaminated cities has beenconducted in the past, primarily inaddressing the possibility of nuclearwar. Such programs should be revisitedwith an eye to the specific requirementsof cleaning up after a radiological attack.

ConclusionThe events of September 11 have

created a need to very carefully assessour defense needs and ensure that theresources we spend for security arealigned with the most pressing securitythreats. The US has indicated itswillingness to spend hundreds ofbillions of dollars to combat threats thatare, in our view, far less likely to occurthan a radiological attack. This includesfunding defensive measures that are farless likely to succeed than the measuresthat we propose in this testimony. Thecomparatively modest investments toreduce the danger of radiological attacksurely deserve priority support.

In the end, however, we must facethe brutal reality that no technologicalremedies can provide complete confi-dence that we are safe from radiologicalattack. Determined, malicious groupsmight still find a way to use radiologicalweapons or other means when theironly goal is killing innocent people,and if they have no regard for their ownlives. In the long run our greatest hopemust lie in building a prosperous, freeworld where the conditions that breedsuch monsters have vanished from theearth. PIR

“Dirty Bombs” Continued from page 9

11

FAS Public Interest Report | March/April 2002

Levi Directs Strategic SecurityProject

In February, Michael Levi waspromoted to director of the StrategicSecurity Project. Since then, Michaelhas endeavored to raise the awarenessof both policy makers and the publicregarding nuclear security issues. Hehas published comments in the NewYork Times, written an Op-Ed for theChristian Science Monitor and has been aguest on several radio and televisionprograms. Since February, he hasinitiated collaborative efforts with theCenter for Defense Information and theMonterey Institute of InternationalStudies regarding low-yield nuclearweapons and the US Nuclear PostureReview. His recent work has alsofocused on missile defense, cooperativesecurity programs with Russia, radio-logical weapons, and nuclear terrorism.A proposal for an article on dirty bombshas been accepted by Scientific Americanand will be forthcoming this summer.Michael continues to amaze with hisastonishing energy, tireless devotion,and sharp intelligence.

FAS Staff NewsStrategic Security Project HiresYassif, Kellar

Jaime Yassif began work as theProgram Assistant for the StrategicSecurity Project in February. She comesto FAS from Swarthmore where shemajored in biology and politicalscience. One of Jaime’s first projects atFAS was conducting research for FAS’testimony before the Senate ForeignRelations Committee. She has alsoassisted in creating a report on the statusof highly enriched uranium in Russiaand other nations. Her hard work onthis project and numerous otherproposals, Op-Eds, and grants has beengreatly appreciated. When Jaime isn’tworking to increase global security, herfavorite recreational activity is dance,and she has recently performed as partof an African dance troupe.

Josh Kellar began work as anintern for the Strategic Security Projectin March. He has undergraduatedegrees in physics and English fromGeorgetown University, and a MA increative writing from Boston University,where he studied poetry. Thus far, Josh

has assisted with physics calculations,editing, and writing, both for theStrategic Security Project and for manyother grateful FAS staff members.

ASMP Intern Returns for MoreMatthew Schroeder rejoined FAS

in February as a Research Associate withthe Arms Sales Monitoring Project. After working during the summer of2001 for the FAS ASMP Project, hereturned to Columbia University’sSchool of International and PublicAffairs to complete his Masters inInternational Affairs. He is also adirector on the National Council of theFellowship of Reconciliation, an 85-year-old peace and justice organization.Before coming to FAS, Matt worked asan intern at the Landmine SurvivorsNetwork. At FAS, Matt has worked onthe ASMP web site and has also beenworking to monitor US militaryassistance to the Philippines, Columbia,Georgia, and Yemen. He hails origi-nally from Holland, MI. PIR

destruction, and bring about a fair andmore humane global society. They alsosupport their professions. We found that70% of FAS members support organiza-tions such as the American PhysicalSociety and the American ChemicalSociety. We did not ask members todifferentiate among the various profes-sional organizations.

“FAS’ top priorities should be . . .”Based on survey results, members’

priorities are right on target with FAS’agenda. Members also reported thatthey would be willing to help advancethese priorities by writing letters tomembers of Congress and the WhiteHouse (41%). A smaller percentage ofmembers said that they would write op-eds to local and national news outlets(18%) and mentor young people whoare interested in careers in science(12%).

In three years, FAS will turn 60, anage seasoned with experience andwisdom. Findings from our member

survey show that our commitment toour mission is constant. FAS is consid-ered one of the most effective organiza-tions in the arms control movement,and we are strong advocates for sensiblepublic policies that reflect the latestdevelopments in science and technol-ogy. This is due, in part, to the steadfastsupport of many long-time members

ATTENTION FAS MEMBERS!

For a short time only, FAS members are offered a discounted sub-scription rate of $49 for Science and Global Security.

Science and Global Security is an international journal for peer-reviewed scientific and technical studies related to arms control,disarmament and nonproliferation policy. It is published three timesa year; the regular subscription rate for individuals is $75.

To take advantage of this offer, call toll-free at 1-800-354-1420 orsend your payment of $49 to Taylor & Francis, Inc., ATTN: CustomerService, 325 Chestnut St. #800, Philadelphia, PA 10106.

and recent upsurge in interest amongyounger Americans. Your supportallows FAS to continue the course thatwas set in 1945. We are very grateful toyou. PIR

PERIODICALS

PAID AT

WASHINGTON, D.C.

FAS Public Interest Report1717 K Street NW, Suite 209, Washington, D.C. 20036(202) 546-3300; [email protected]

March/April 2002, Volume 55, Number 2

ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED

FAS Public Interest Report | March/April 2002

not yet caught up. This may be informa-tion that was formerly available on websites, but that has now been removed, orrecords that were officially declassifiedand released, but that have now beenwithdrawn. It is everything that mightconceivably be considered “sensitivebut unclassified.”

In deciding how to treat suchinformation, the Administration shouldenunciate a clear set of guiding prin-ciples, as well as an equitable procedurefor implementing them and appealingadverse decisions.

The guiding principles could beformulated as a set of questions, such as:

� Is the information otherwiseavailable in public domain? (Orcan it be readily deduced fromfirst principles?) If the answer isyes, then there is no valid reasonto withhold it, and doing so wouldundercut the credibility of officialinformation policy.

� Is there specific reason to believethe information could be used byterrorists? Are therecountervailing considerations thatwould militate in favor of disclo-sure, i.e., could it be used forbeneficial purposes? Documentsthat describe in detail howanthrax spores could be milledand coated so as to maximize theirdissemination presumptively pose

“Information” Continued from page 2 a threat to national security andshould be withdrawn from thepublic domain. But not everydocument that has the word“anthrax” in the title is sensitive.And even documents that are insome ways sensitive mightnevertheless serve to inform

medical research and emergencyplanning and might therefore beproperly disclosed.

� Is there specific reason to believethe information should be publicknowledge? It is in the nature ofour political system that itfunctions in response to publicconcern and controversy. Envi-ronmental hazards, defectiveproducts, and risky corporatepractices only tend to find theirsolution, if at all, following athorough public airing. With-holding controversial informationfrom the public means short-circuiting the political process,and risking a net loss in security.

Of course, no set of principles willproduce an unequivocal result in allcases. There will often be a subjectiveelement to any decision to release or

withhold contested information.Someone will always be dissatisfied.

In order to forestall or correctabuses or mistaken judgments, anappeals process should be established toreview disputed decisions to withholdinformation from the public. Placingsuch a decision before an appeals panel

that is outside of the originatingagency—and that therefore does nothave same bureaucratic interests atstake—would significantly enhance thecredibility of the deliberative process.

The efficacy of such an appealsprocess has been repeatedly demon-strated by an executive branch bodycalled the Interagency Security Classifi-cation Appeals Panel. This panel, whichhears appeals of declassificationrequests from the public that have beendenied by government agencies, hasruled against its own member agenciesin an astonishing 80 percent of thecases it has considered.

A good faith effort to increase theclarity, precision, and transparency ofthe Bush Administration’s informationpolicies, along with provisions for thepublic to challenge a negative result,would go a long way towards rectifyingthe current policy morass. PIR

We are watching a veil of indiscriminatesecurity descending on significant portions ofthe American policy process.