Vol. 10 No. 4 Summer 2006 Journal, Summe… · 1987. In 1989 he received a Certificate in...

Transcript of Vol. 10 No. 4 Summer 2006 Journal, Summe… · 1987. In 1989 he received a Certificate in...

Vol. 10Summer

No. 42006

C O N T E N T S

THE SEATTLE STUDY CLUB JOURNAL 10/4Editor-in-Chief • M

ichael Cohen DDS MSD • M

anaging Editor • Suzanne E. Cohen JD • Senior Clinical Editor • Ariel J. Raigrodski DMD M

SSenior Journal Advisors • M

orton Amsterdam DDS ScD • D. Walter Cohen DDS • Senior Clinical Editor • Frank Spear DDS M

SD Design • Suzanne E. Cohen JD • Production • Janell V. Edw

ardsThe Seattle Study Club Journal (ISSN 1091-4579) is published quarterly by the Seattle Study Club Journal, Inc., 3411 Evergreen Pt. Rd., M

edina, WA 98039Telephone (425) 576-8000 • Fax (425) 827-4292 • http://w

ww.seattlestudyclub.com • Copyright 2006 by The Seattle Study Club Journal, Inc.

All rights reserved • No reproductions, photocopying, storage or transmittals without w

ritten permission of the publisher

2 G U E S T E D I T O R I A LS u z a n n e C o h e n J D

5 C O M M E N T A R YD a v i d S c h w a b P h D

8 C L I N I C A L C A S E 4 6H e n r y N i c h o l s D D S

S t i g O s t e r b e r g D D S M S D

1 3 C L I N I C A L C A S E 4 5G e o r g e D u e l l o D D S M S F A C D

J a c k M a r i n c e l D D S

K e v i n T h o r p e D D S

2 8 R E M E M B E R I N G D R . B O B S T U L T Z2 9 S P E C I A L R E P O R T 8

R o s a r i o P a l a c i o s D D S M S D

A r i e l R a i g r o d s k i D M D M S

S Y M P O S I U M S Y N O P S E S :S u z a n n e C o h e n J D

1 9 O r e n H a r a r i P h D2 1 B a r b a r a L e h m a n2 7 W a y n e D y e r P h D3 4 S c o t t M c K a i n3 6 S u s a n B r o s s3 8 S S C J 1 0 Y E A R I N D E X

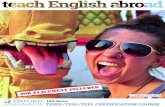

O n t h e c o v e r : s e e p a g e 4A p o r t r a i t o f D r . N e w t o n F a h l , J r .

b y S e a t t l e a r t i s t S o n D u o n g .

GUEST EDITORIAL

2

MICHAEL COHEN DDS M

SD

The China Study: The Relationship of Diet, Health & Disease

What do we really know?If somebody told you that adopting a plant-

based nutrition plan for the rest of your life would likely shield you from most cancers, re-verse heart disease and prevent diabetes, would you do it? Probably not, because unless you’d recently read The China Study by T. Colin Campbell, you’d believe you know what most of us believe we know: that animal protein is vital to our nutrition, that our genetic material largely governs our health regardless of diet or lifestyle, and that recent studies, the results of which have been widely circulated by the U.S. media, “prove” that changing your diet doesn’t do that much for one’s health. But do we really know these things or do we just hold an opinion about them?

2,400 years ago, Hippocrates said: “There are, in fact, two things, science and opinion. Science begets knowledge. Opinion begets ignorance.” In The China Study, T. Colin Campbell uses scientific evidence to challenge every opinion about nutrition that most of us have held for years.

The link between animal protein and cancerT. Colin Campbell, Ph.D., is a nutritional re-

searcher from Cornell University who began his professional career searching for ways to make cattle and sheep grow faster. The purpose was to improve on the U.S. food industry’s ability to produce animal protein, in order to feed the world. Shortly thereafter, he undertook a USDA-funded project in the Philippines, working with malnourished children. The goal of this ten-year program was to ensure that the children were getting as much protein as possible. Another part of the Philippine project was to investigate the unusually high rate of liver cancer in the children there. Researchers hypothesized that high consumption of aflatoxin, a potent mold-toxin carcinogen that occurs in peanuts and corn, caused the liver cancer.

During this project, Campbell discovered something that challenged his own beliefs and started his life-long quest for the truth about nutrition and disease. He found that the Filipino

children who ate the highest protein diets were the ones most likely to get liver cancer from the aflatoxin. Surprised by this result, he searched the literature for corroboration, and turned up a research report from India. In that study, an identical dose of the deadly carcinogen aflatoxin was administered to two groups of rats. One group was fed a diet with 20% protein, similar to what most people living in the Western world consume. The other group was fed a diet that was only 5% protein. At the end of the study, all the rats that ate the 20% protein diet had evidence of liver cancer, and none of the rats that ate the 5% protein did.

This was contrary to everything Campbell had ever been taught, and it was a defining moment in his life. T. Colin Campbell, the son of a dairy farmer, who grew up eating bacon, eggs, fried potatoes and whole milk, was about to step into the abyss. As he states, “It was heretical to say that protein wasn’t healthy, let alone to say that it caused cancer.” Although it wasn’t a wise career move at the time, he decided to start a lab program that investigated the role of nutrition, and specifically animal protein, in the development of cancer. He wanted to understand “not only whether but also how protein might promote cancer.” He designed a study that was funded for 27 years by organiza-tions such as the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society and the American Institute of Cancer. This animal study showed that “low-protein diets inhibited the initiation of cancer by aflatoxin, regardless how much of this carcinogen was administered to these animals. After cancer initiation was completed, low-protein diets also dramatically blocked sub-sequent cancer growth…. In fact, dietary protein proved to be so powerful in its effect that we could turn on and turn off cancer growth simply by changing the level consumed.” The protein used in these studies was casein, from cow’s milk, and the mechanism by which the protein promotes the growth of cancer was found to be in the increase in enzyme activity that allows a carcinogen to bind to a cell’s DNA. Plant protein was also studied, and it did not promote cancer growth, even at higher levels of intake.

SUZANNE COHEN JD

3

result, the weight of the evidence supporting protein’s role in the development of liver cancer starts to mount. One by one, Campbell takes on the “normal” diseases of the Western world like coronary heart disease, Type II diabetes and cancers of the breast, the stomach and the bowels, and shows the statistically significant relationship between consumption of animal protein and the prevalence of these diseases in Western populations versus the relative absence of these diseases in the Chinese villagers who ate a primarily plant-based diet.

The role of geneticsCampbell agrees that our genes govern ev-

erything that occurs inside our bodies, but he argues that our environment, and especially our nutrition, determines whether a genetic predisposition will be expressed. As evidence, he points to numerous studies showing that as people migrate to different countries, they take on the disease risk of the new country as they adopt the eating habits of its people. Their genes remain the same, yet they suffer from disease and sickness that is rare in their home countries. In addition, he believes it is biologically impos-sible to blame our current epidemic of obesity, heart disease and diabetes on genetics, because it has happened too quickly.

How come nobody told us this?Campbell reveals why the American public

is so confused about nutrition, and why we never get the “straight story.” As he says, “the distinctions between making a profit and pro-moting health [and those] between government, industry, science and medicine have become blurred…the result is massive amounts of mis-information.” He also explains why research like the supposedly well-designed “Nurses’ Health Study” that showed no health benefits from reducing dietary fat and increasing fiber, is junk science. As Campbell explains, the Nurses’ Health Study simply compared two uniformly carnivorous groups of women, and, no surprise; the small differences between them didn’t amount to much in terms of health im-provement. The low-fat group did not reduce their fat consumption below 20%, and even to achieve that level of intake they did not reduce their intake of animal protein. Instead, they used low-fat and nonfat animal products, along

The implications for other cancersWhile Campbell and his students were doing

research on the effect of casein on aflatoxin- induced liver cancer, researchers at the University of Illinois were working on breast cancer. The Illinois study showed that higher casein intake promoted breast cancer in rats dosed with two experimental carcinogens, through the same female hormone system that exists in humans. As Campbell observes, “an impressively consis-tent pattern was beginning to emerge…. Casein affects the way cells interact with carcinogens, the way DNA reacts with carcinogens and the way cancerous cells grow.” Campbell and his students then initiated more animal cancer studies using different nutrients, including fish protein, dietary fats and antioxidants like carot-enoids. The results of these studies on animals showed that “nutrition was far more important in controlling cancer promotion than the dose of the initiating carcinogen” and that “nutrients from animal-based foods increased tumor devel-opment while nutrients from plant-based foods decreased tumor development.”

Does it work the same way in humans?Campbell went on to direct a massive study

arranged through Cornell University, Oxford University and the Chinese Academy of Preven-tative Medicine. This project examined a wide range of diseases, diet and lifestyle in rural China and Taiwan. It ultimately produced more than 8,000 “statistically significant associations between various dietary factors and disease.” The result was the same as in the animal studies: “People who ate the most animal-based foods got the most chronic disease. People who ate the most plant-based foods were the healthiest and tended to avoid chronic disease.”

In great depth, Campbell describes the re-search and the findings from his survey of 6,500 adults and their families in China. In the process, he is careful to explain the difference between correlation and causation. For example, just be-cause high protein intake by the children in the Philippines is correlated with high rates of liver cancer does not mean that protein causes liver cancer. However, when the correlation is statisti-cally significant, that is, when there is less than a 5% probability that an observed effect is due to chance, and when analysis of the combined data from multiple studies shows the same

4

with less fat in cooking and at the table. They did not adopt the largely plant-based diets that have been shown worldwide to be associated with low breast cancer rates. In lay terms, the study failed to show the difference between apples and oranges, because they were comparing apples to apples. Furthermore, in Campbell’s view, this study and others like it that focus on one “magic” ingredient such as fiber, lycopene or a certain vitamin, fail to recognize the complex relationship between whole foods-based nutrition and health. Healthy, disease-proofing nutrition simply cannot be reduced to one or two ingredients or substances.

The tip of the icebergThere’s far more research results discussed in

The China Study than are detailed here, and the information presented overwhelmingly supports

On The Cover — A Tribute to Dr. Newton Fahl, Jr.

On the cover of this issue, we honor Dr. Newton Fahl, Jr., one of the superstars of international dentistry. Newton received his DDS degree from Londrina State University, Brazil, in

1987. In 1989 he received a Certificate in Operative Dentistry and Master of Science degree from the University of Iowa. After return-ing to Brazil, he settled in Curitiba, where he maintains a private practice emphasizing aesthetic and cosmetic dentistry. He is also Director of the Fahl Art & Science in Aesthetic Dentistry Institute in Curitiba, where he conducts hands-on and lecture courses on direct and indirect adhesive restorations.

Dr. Newton Fahl, Jr. is a member of the American Academy of Esthetic Dentistry (AAED), and founding member and past-president of the Brazilian Society of Aesthetic Dentistry (BSAD). He is a MCG-

Hinman Foundation fellow. Dr. Fahl has published several enlightening articles on direct and indirect bonding techniques. He is on the editorial board of the European Journal of Esthetic Dentistry, and of Practical Procedures & Aesthetic Dentistry - PPA&D.

Newton’s cross-cultural educational experiences have had an interesting effect on his speech patterns. He speaks English fluently, but with a slight Mid-Western twang. He has also picked up much of the slang used in the U.S., which makes him seem very American. He is a popular lecturer with clinicians everywhere, as he is easily able to articulate both his extensive knowl-edge of, and his passion for, dentistry. His slides are amazing and his technique is exquisite. Even to a layman, it is easy to see that Newton’s work is awesome. It is no wonder that he has gained a world-wide reputation as a top clinician and an excellent teacher.

Newton and his wife, Grace, are a charming and easy-going couple who are devoted to each other. Michael and I had the pleasure of their company at a neighborhood barbecue at our house a couple of years ago, and we were amazed how easily they integrated into the conversation. They could have moved in next door without skipping a beat — they were that comfortable with our friends, our dogs, and our environment. It’s rare that we get such per-sonal insight into speakers from other countries (let alone their wives) but with Newton and Grace, after one evening, it was as if we’d known them all our lives.

—Suzanne Cohen JD

the proposition that adopting either an entirely plant-based diet or a largely plant-based diet will lead to a longer, healthier life. In addition, Camp-bell tells a frightening tale of the role of industry in the development of our government-sanctioned food guidelines. He concludes that when it comes to health, our “government is for the food industry and the pharmaceutical industry at the expense of the people.”

ConclusionWhether you choose to go vegan or not, this

is a book worth reading. At the very least, The China Study will make you question everything you’ve ever been taught about nutrition. And, if Campbell’s research convinces you to make a heathful change in your lifestyle, it may be the most important book you’ll ever read.

5

COMMENTARYIn my weekly travels across North America, I

am always on the lookout for nascent trends that will shape the future of dental practice

management. Here are some observations.

1. Pay upfront. While there are still practices that struggle with insurance reimbursement issues, many practices are now pure fee-for-service establishments. Patients pay for dental treatment upfront for the right to be scheduled. It’s a take-no-prisoners philosophy that removes the practice from the insurance hassle, guar-antees collections, and strongly encourages patients to show up for their prepaid treatment. With the widespread popularity of third-party financing companies such as Care Credit, there are now practices that focus solely on dentistry, not financial issues.

2. Increased automated reminders and e-mail. Practices with busy hygiene schedules have dramatically reduced the workload on their front office staff by using automated call-ing systems to confirm appointments. These systems can also send patients e-mail reminders. Practices that choose not to use such systems can also save hours of staff time each week by confirming a substantial number of patients by e-mail rather than phone calls.

3. Web videos. Look for more dental web sites to contain customized video clips. With broadband internet service now widely avail-able, television quality videos can be played on most home computers. The videos can be designed to introduce the doctor and the practice to new patients or explain treatment modalities. Web video is the next great trend in patient education.

4. Video brochures. To provide yet another delivery mechanism for practice videos, some doctors are giving patients educational DVDs to take home. Anecdotal evidence suggests, however, that very few patients take the time to load the DVDs into their home equipment and watch the show. The upside is that those pa-

DAVID SCHWAB PHD

tients who do sit on the couch to watch “Dental Masterpiece Theater” have a higher than average case acceptance rate.

5. Wireless headsets. Some dental offices are beginning to look like Mission Control at NASA, because everyone is wearing a small headset. There are headsets that are designed for internal communications, while others, worn by front office staff, are for telephone conversations with patients. Administrative staff report a great sense of freedom when they are “untethered” from the phone cord and the need to cradle the receiver. Because staff are able to move about freely and use their hands to type and complete other tasks while on the phone, they are more likely to multi-task and therefore get more done in less time.

6. Seamless and immediate referrals. The old-fashioned referral card is on the endangered species list. Many referral-based practices now provide the capability for on-line referrals, or at least include on their web sites PDF files that referring offices can print out as needed and fax to the specialist’s office. Because digital ra-diographs can also be easily e-mailed, the time element in the referral process is collapsing.

7. Paperless offices. Those young dentists who are opening new practices are apparently environmentally conscious, enamored of high tech, just plain smart—or all three. They are not clearing forests to create piles of paper in their new offices. Instead, they are installing wireless networks, capturing data on tablet PCs, and creating impeccably documented patient records stored on computer chips. They also access patient records from PDAs or laptop computers from remote locations and create back-up files in multiple locations. We are rap-idly approaching the point where using a pen to write in a patient’s chart will be as antiquated as a pegboard scheduling system.

8. Return of the floaters. The concept of having a person in the office who can “float”

20 Practice Trends That Will Affect Your Practice

6

between the front and back is not new, but traditionally this arrangement worked better in theory than in practice. However, economic necessity and a new breed of dental assistants have combined to revitalize the concept. There are now more dental assistants who truly have the ability to handle both clinical and admin-istrative duties. It is difficult to keep a foot in each camp, but dental assistants nowadays are looking for a more varied work experience.

9. Part-timers gain respect. The booming economy has created low unemployment, which means that dentists are having a hard time find-ing quality employees who want to work full-time. The conventional wisdom states that part-time employees do not have the same interest or level of commitment as their full-time coun-terparts. However, the typical employee who is juggling family and work responsibilities may not be able to devote thirty hours or more per week to a job. Practices are increasingly turning to part-time employees who work their hearts out one to three days per week in return for a steady paycheck and one of dentistry’s greatest fringe benefits for most employees—the ability to leave the job behind when they go home.

10. Flex schedules. When employees’ child care responsibilities collide with the need for the dental office to be open on a fixed schedule, the solution is for employees to use flexible schedules, so that some come in early while oth-ers stay late. There are also practices that allow some administrative tasks such as bookkeeping to be done off site. As an aside, some successful doctors are working three and one-half days per week or less, and limiting the number of days per month that they work. When practices run with Swiss-watch precision, they supercharge the in-office work schedule and allow everyone a generous amount of time off each week.

11. Spa dentistry. There has been quite a revolution in the massage business. Just a few years ago, who would have thought that one could get a massage in an airport? There are dental practices that are transforming them-selves into personal care emporiums, where patients can relax, listen to their favorite mu-sic, have their teeth whitened in one visit, and enjoy a head and neck massage as part of the experience.

12. Comprehensive care. It is certainly true that Directors and Members of Seattle Study Clubs have been in the forefront of effort to treat patients comprehensively. The rest of the profession is catching up quickly, however. Patients who are content with patch work and one-tooth-at-a-time dentistry will have to look harder to find a dentist, because sophisticated diagnosis and treatment planning are becoming the norm.

13. More advertising. It is ironic that while dentists have never been busier, they have also never been as interested in trying out various types of media to advertise their services. The two hottest trends in media for the dental pro-fession are infomercials and radio advertising. Infomercials are gaining respectability, and ra-dio advertising seems to work best for a niche market, such as “relaxation dentistry.”

14. Implants go mainstream. In the realm of restorative dentistry, we are in the midst of a sea change. For years, some dentists ran away with the implant market while others dabbled or procrastinated. With the advent of computer guided surgery and less invasive surgical proce-dures for implant placement, everyone, as they say, is getting into the act. The implant market is booming, wide open, full of opportunity, and unforgiving to those who are not nimble enough to keep up with scientific advances and a market that is continually expanding, morphing, and shattering old paradigms.

15. Greater schedule discipline. Scheduling in a dental office creates an inherent conflict between the desire to please the patient and en-force schedule discipline. In order to prevent the inmates from running the prison, offices need to maintain control of their schedules. There is a trend toward more schedule discipline: certain procedures are only done on certain days at specific times. With a firm but tactful approach and the ability to bend but not break, office managers can mollify patients but still ensure that the day’s production goal is reached by lunchtime.

16. Purposeful marketing of cosmetic dentistry. Now that virtually every general dental practice has had an image makeover and emerged as a “cosmetic dental practice,”

7

area. Having a professional take charge of the office décor and make the entire office flow together with a definable look and feel can take the practice to a new level and smartly comple-ment patient education efforts.

20. Increased confidence and optimism. Practicing dentistry can be very rewarding, but it is not easy. A well run dental practice is like a machine with thousands of moving parts, all interdependent and, on any given day, subject to wear and tear, fatigue, stress, burnout, or outright failure. However, when everything is humming just right, a dental practice achieves its objective of improving the quality of people’s lives. Given favorable demographics, stable eco-nomic conditions, and impressive technological advances, many doctors are exuding rock-solid confidence that, to paraphrase Shakespeare, grows on the very success on which it feeds.

As writer Alan Kay has said, “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.” It is more important than ever to use the networking ca-pabilities of the Seattle Study Club, not only to keep abreast of future trends, but to be part of a group of forward-thinkers and early adaptors who are continually inventing those trends.

David Schwab, Ph.D., provides lively and entertaining practice management seminars and he offers in-office consul-tations to help practices reach the next level. He has an audio series available for doctors and team members. Dr. Schwab works extensively with the Seattle Study Club and its affiliates. He may be con-tacted at (888) 324-1933 or via e-mail at [email protected]. His website is www.davidschwab.com.

it is more important than ever for practices to differentiate themselves. More practices are creating holistic marketing campaigns by tying together their exterior signage, office appear-ance, collateral materials, and web site to form an integrated whole that gets the cosmetic mes-sage across effectively and unambiguously.

17. Expanded communication functions for dental assistants. The dental assistant ex-plained her decision to leave the practice in a manner-of-fact manner. “The doctor just wanted me to assist him chairside,” she said. “I never got a chance to work with the patients.” By “work with the patients,” she meant the opportunity to chat with patients at length to educate them and answer their questions. This assistant is now happily employed by another doctor. In the new venue, the doctor reports that the assistant is not only excellent in the clinical arena, but she also puts patients at ease and has them purring with contentment as they schedule their treatment. This is the dental assistant of the future.

18. More show and tell. Great verbal skills will always be critical, but there is also a trend to show patients impressive visuals on a regular basis. These can be digital x-rays, computer-generated animation, images captured by an intra-oral camera, or before and after photos. There are even some doctors who include pho-tos in the post-treatment letter, both to remind patients of how much the dental treatment has improved their smile and to give patients some-thing tangible to show their friends (including those who may need a dentist).

19. More attention to office décor. While most dental offices are kept in ship-shape con-dition, there is a trend toward hiring interior decorators to bring out the best in the reception

8

Clinical Treatment Planning • Case 46Treating Clinicians: Drs. Henry Nichols and Stig Osterberg

Initial facial view

Initial smile

Anterior view out of occlusion

Initial Presentation: May 2001Age at Presentation: 53 Initial Records Made: September 2001Records Remade: May 2003

Introduction and Background

The patient was initially seen for several emergency visits and disease control. As she became more aware of the importance of her oral health, she expressed the will to improve it. Her chief complaint was: “I am unable to chew properly, my teeth are worn, and I do not like the way my teeth look.” Although the patient expressed the above concerns, she waited two years before pursuing treatment.

Medical History

• Oral estrogen replacement and synthroid. • Otherwise non-contributory.

Diagnostic Findings

Extraoral/Facial: • Minimal facial asymmetry. • No incisal edge display of the maxillary anterior

teeth at rest. • No display of the free gingival margins of the maxil-

lary anterior teeth at maximum smile. • Dental midline is coincidental with the facial midline

but not parallel. • Slight occlusal cant on the left side due to supra-

eruption of the maxillary premolars.

9

Initial right lateral view in maximal intercuspation Initial anterior view in maximal intercuspation Initial left lateral view in maximal intercuspation

192829 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 18

LINGUAL

RIGHT

FACIAL

LINGUAL

LEFT

FACIAL

8/29/2001

8/29/2001

31 30 17

Probings

Probings

Mobilities

32

2 2 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

2 1 22 1 22 2 21 1 12 1 21 1 22 1 11 1 11 1 11 1 11 1 11 1 1

3 3 3

2 2 2

143

Probings

Mobilities

FACIAL

RIGHT

LINGUAL

FACIAL

LEFT

LINGUAL

8/29/2001

8/29/2001Probings

254

6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 15 161

3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 2

2 2 22 2 21 1 21 1 12 1 11 1 22 1 22 1 22 2 24 4 2

2 2 2

2 2 2

10

FMX-2001

TMJ/Mandibular Range of Motion: • Within normal limits. • No history of joint noise or pain.

Intraoral: Dental: • Missing teeth #’s 2, 3, 4, 14, 16, 19, 30, 32. • Tipped molars #’s 17, 18. • Proportionally smaller bicuspids. • Moderate anterior tooth wear. • Large posterior restorations. • Maxillary and mandibular midlines were not coinci-

dent, with the mandibular midline deviating 2 mm to the left side.

• Maxillary palatal torus.

Periodontal: • Excellent plaque control. • All probing depths were within normal limits. • Mesially tipped molars #’s 17, 18 with root proximity.

O c c l u s a l N o t e s • CR = MIP (maximal intercuspal position).

• Vertical overlap: 70%.

• Horizontal overlap: 4 mm.

• Tipped molars #’s 17 & 18.

• Bilaterally Angle Class I malocclusion according to the canines.

R a d i o g r a p h i c R e v i e w • Caries tooth # 12.

• Large maxillary sinuses.

11Stop! Time to Outline Goals/Objectives of Treatment and Treatment Plan

D i a g n o s i s a n d P r o g n o s i s • AAP Type I – isolated areas of mild

gingivitis.

• Partial edentulism.

• Anterior tooth wear.

• Bruxism.

• Prognosis with treatment is fair to good.

S u m m a r y o f C o n c e r n s• What would be the best way to restore the

dentition with proper occlusion?

• Would orthodontics be beneficial, especially in managing the tipped molars?

• Is there a need to modify the vertical dimension of occlusion?

• How will tooth wear be corrected and managed?

• Does the existing anterior guidance need to be modified?

• What is the best way to restore the posterior missing dentition?

• Would a combination of surgical and orthodon-tic treatment be optimal for this patient?

Occlusal views of the maxillary and mandibular arches

12

Proposed Treatment Plan • Case 46Phase I: Initial Therapy

1. Oral examination with full-mouth radiographs.2. Oral hygiene instructions.3. TMJ evaluation.4. Periodontal prophylaxis and maintenance.5. Caries control tooth # 12.

Phase II: Diagnostic Work-up

6. Records: Two sets of diagnostic casts, centric relation record, face bow transfer, and a full set of photographs.

7. Evaluate the edentulous sites for endosseous implants.

8. Orthodontic consultation.9. Diagnostic wax-up.10. Patient consultation.

Phase III: Implant Placement

11. Place implants to restore teeth #’s 2, 3, 4 & 30.12. Evaluate implant integration.

Phase IV: Provisional Restorative Treatment

13. Maxillary Arch: Provisional complete coverage crowns teeth

#’s 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 & 12 and a 3-unit provisional fixed partial denture prosthesis (FPDP) restoring teeth #’s 13-15.

14. Mandibular Arch: Provisional complete coverage crowns teeth

#’s 20-31.

Phase V: Surgical

15. Remove teeth #’s 1 & 17.

Phase VI: Definitive Restorative Treatment

(Excluding teeth #’s 18 & 19.)16. Individual crowns teeth #’s 2-12, 3-unit FPDP teeth

#’s 13-15, and individual crowns teeth #’s 20-31.17. Maxillary occlusal splint.

Phase VII: Orthodontic Treatment

(By opening of the vertical dimension of occlusion, orthodontic uprighting of tooth # 18 would be facilitated.)18. Upright tooth # 18.

Phase VIII: Implant Placement

19. # 19 implant.

Phase IX: Restorative

20. Individual crowns teeth #’s 18 & 19.

Phase X: Re-evaluation and Maintenance

Henry Nichols is in the private practice of general den-tistry, Port Townsend, WA and is a Restorative Advisor for the Olympic Peninsula Study Club and Great Blue Heron Seminars.

Stig Osterberg is in the private practice of periodontics, Port Townsend, WA and is the Director of the Olympic Peninsula Study Club.

1

2

3

4

5

6

78 9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

1831

1930

2029

2128

22272326 2425

32

LOWERARCH

UPPERARCH

CC

C

C

CC

C C C CC

C

C

C

CC

C

C

C

C

FPDP

I/C

I/C

I/C

I/C I/C

FPDP = fixed partial denture prosthesis I/C = implant supported crown C = crown

13

Active Clinical Treatment • Case 45Treating Clinicians: Drs. George Duello, Jack Marincel, and Kevin Thorpe

Age at Initial Presentation: 53 Initial Presentation: July 2004 Active Treatment Completed: January 2006

Review of Treatment Goals

The patient was initially seen for implant therapy. How-ever, during the consultation and co-discovery phase she expressed aesthetic concerns; specifically, the color and wear on her front teeth. This patient was presented at the Gateway Study Club as part of the first Web-based treatment planning sessions with Dr. John Kois. In consid-eration of these events, the goals mutually established for this patient were (1) elimination of oral pathology through strategic extractions; (2) functional therapy to reduce or eliminate the occlusal dysfunction and replacement of strategically extracted teeth with implant prostheses; and (3) dento-facial treatment to improve the shape, surface-texture and color of the anterior teeth.

Phase 1: Restorative Phase

The patient was advised of the need for comprehen-sive occlusal and orthodontic evaluations in anticipation of presentation for the Web-based learning program. Cephalometric radiographs, tracings, and analysis were performed for the patient in addition to a centric relation record and mounting on a Panadent articulator. Doppler TMJ analysis was performed to evaluate the competency of the joints—these findings were within normal limits.

Pre-treatment diagnostic digital photographs were taken and aesthetic enhancements were performed in Adobe Photoshop CS using the methods of Dr. Greg Lutke. All diagnostic information was summarized using the Ten Step Diagnostic Opinion developed by Dr. Kois and used for the SSC Web-based programs. Based on the conclusions of the Web-based program with Dr. Kois, a definitive treatment plan for the patient was collectively formulated by the Gateway Study Club for the treating clinicians. A metal-ceramic crown was previously fabricated for tooth # 19 and was cemented with a composite-resin cement in late fall of 2004. Prior to the cementation of the crown on tooth # 19, an MOD direct composite-resin restoration was placed on tooth # 4. Following these procedures, irreversible hydrocolloid impressions were made for the fabrication of at home bleaching trays for use with 15% carbamide peroxide gel. After successful home bleaching, the patient was seen for the initial direct composite-resin restorations on the maxillary anteriors. A silicone putty index was used along with a 3 tier layer-ing technique to lengthen the maxillary and mandibular incisal edges based on the aesthetic imaging, occlusal analysis, and the diagnostic wax-up, emulating the meth-ods of Drs. Magne and Fahl, Jr. An acute periodontal abscess developed in the tooth # 30 region and was treated with systemic amoxicillin with immediate referral to the periodontist for the surgical phases of treatment.

Pre-treatment facial view Final facial view

14

Final right lateral view in maximal intercuspation Final anterior view in maximal intercuspation Final left lateral view in maximal intercuspation

143

Probings

Mobilities

FACIAL

RIGHT

LINGUAL

FACIAL

LEFT

LINGUAL

8/18/2004

8/18/2004Probings

254

6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 15 161

3 3 4 2 2 3 2 2 3 3 2 3 3 2 3 3 2 3 3 2 3 6 5 43 4 3

4 2 4 4 3 43 3 33 2 33 2 33 2 33 2 33 2 33 3 3

3

4 2 3 3 3 3

14

3 3 3 3 2 3

3 2 3 3 2 3 3 2 2 3 2 3 3 2 2 2 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 2 3 3 3 33 3 3

3 3 3 4 3 43 2 32 2 23 2 22 2 32 2 23 2 23 2 3 3 2 3 3 2 2 2/7/2006

2/7/2006

2829 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18

LINGUAL

RIGHT

FACIAL

LINGUAL

LEFT

FACIAL

8/18/2004

8/18/2004

31 30 17

Probings

Probings

Mobilities

32

3 3 3 3 2 3 3 2 2 2 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 2 3 3 2 3

4 3 43 2 3 3 2 33 3 33 2 23 2 22 2 22 2 23 2 23 3 3

0 5 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

0 3 4

3 2 3 2 2 2 1 1 2 1 1 2 2 1 2 1 1 23 2 3 2 1 23 2 3 2 2 2 3 2 3 3 2 3

3 2 3 2 3 3 3 3 3 2 1 22 2 22 1 22 1 22 1 22 2 2 3 2 32 2 2 3 2 3

2/7/2006

2/7/2006

15

the maxillary anterior restorations was accomplished to meet the aesthetic goals of the patient.

Phase II: Surgical Phase

The initial treatment plan sequence called for therapy to begin on the maxillary left posterior sextant with the mandibular right posterior sextant to follow. However, the patient traumatically fractured the distal abutment tooth, a hemi-resected mandibular right first molar, in March of 2005. Therefore initial surgical therapy was started in the mandibular right sextant with the strategic extraction of the distal root # 30 after sectioning the connector on the

PANO-2004

PANO-2006

In support of the surgical phases, Valplast acrylic interim removable partial dentures where made for the maxillary left and mandibular right sextants. The patient was in discomfort when wearing the mandibular interim partial denture and wore the appliance minimally after insertion. As soon as the implants were placed in the mandibular right sextant, the interim removable partial denture was converted to an immediately loaded pro-visional screw-retained prosthesis. In the maxillary left sextant, the patient was comfortable and compliant with the use of the Valplast interim removable partial denture. During the surgical phase, modification and finishing of

16

tion of the mandibular right sextant, surgical therapy was performed on the maxillary left posterior sextant. The roots of teeth #’s 13 & 14 had remained asymptomatic until July of 2005 when the root of tooth # 14 fractured. This fracture led to an acute periodontal abscess that was initially managed with systemic antibiotics immediately followed by strategic extraction of teeth #’s 13 & 14. After debridment of the sockets, it was deemed pos-sible to place immediate implants in the sockets without sinus elevation. Two parallel walled endosseous implants were placed in Type III bone in the maxillary left sextant and were deemed stable. However, these implants did not

mesial abutment retainer. After extraction and site inspec-tion, it was deemed feasible to perform immediate one stage implant insertion in teeth #’s 29 & 30 sites. Paral-lel walled endosseous implants were placed in Type II-III bone and were deemed stable at 45 Ncm after insertion. Screw-retained composite-resin provisional restorations were fabricated for immediate provisional loading of the implants after allograft bone placement. The soft tissue was sutured and allowed to heal for 3-4 months with a screw-retained provisional restoration. The post-operative course for this treatment was uneventful. Following healing and definitive prosthetic rehabilita-

FMX-2004

FMX-2006

17

Implant placement teeth #’s 29 & 30 sites Screw retained composite resin provisionals #’s 29 & 30 Allograft of residual defects #’s 29 & 30

Immediate provisionals teeth #’s 29 & 30 Periapical of provisionals #’s 29 & 30 Final healing of soft-tissue around provisionals

CAD-CAM titanium Procera abutment Definitive porcelain metal-ceramic crowns #’s 29 & 30 Root fracture with periodontal abscess tooth # 14

Immediate implant placement — allograft socket augmentation

CAD-CAM Procera zirconia abutment Definitive Procera AllZirkon crowns teeth #’s 13 & 14

18

meet either the mechanical or the biologic requirements for immediate loading. Mineralized allograft mixed with medical grade calcium sulfate was placed to augment the peri-implant spaces in the socket followed by low profile healing abutments. A Valplast acrylic interim removable partial denture was fabricated by the general dentist at the patient’s request during the healing phase in this sextant. Both surgical treatments’ sequelae were uncomplicated and osseointegration was confirmed by radiographic and standard clinical methods. The patient was referred back to the general dentist for the final restorative phase.

Phase III: Prosthetic Phase

After implant surgical treatments, the patient was seen for definitive restorative therapy. The healing abutments in the maxillary left sextant and the composite-resin pro-visional restoration in the mandibular right sextant were removed, and implant level open-tray impressions were made. Stone casts with soft-tissue indexes were made by the laboratory technician for fabricating custom abut-ments. The abutments’ wax-patterns were scanned with a Nobel Biocare Procera scanner for CAD-CAM custom zir-conia abutments for teeth #’s 13 & 14 and custom titanium abutments for teeth #’s 29 & 30. Upon return and modification of the zirconia abut-ments, the maxillary zirconia abutments were scanned for zirconia copings to serve as an infrastructure for Procera AllZirkon crowns for teeth #’s 13 & 14. The titanium abut-ments served as platforms for metal-ceramic crowns for teeth #’s 29 & 30. In conjunction with the overall occlusal reconstruction, teeth #’s 2, 18, 19, and 31 received new metal-ceramic crowns that were definitively cemented with resin-modified glass ionomer cement (RelyX luting cement, 3M ESPE). Tooth # 2 became symptomatic with pulpalgia after cementation and the patient was referred to the endodontist for therapy. After successful endodontic therapy and cessation of the patient’s symptoms, it was elected to place a new metal-ceramic crown on tooth # 2. Subsequently, a maxillary clear hard acrylic occusal guard was provided to the patient.

Commentary

This case represents the cumulative efforts of a Seattle Study Club and its members. The diagnostic phase of this patient utilized methods taught by expert clinicians at the SSC National Symposia and the Web-based treat-ment planning sessions. These methodologies guided the Gateway Study Club collectively to formulate the treat-ment plan for this patient in our annual treatment planning session for the treating clinicians. Although the expert

opinions weighed heavily in the final treatment plan for this patient, the formulation of the eventual treatment was not without a spirited debate by our members. Given the extensive time devoted to the treatment planning and sequencing for this patient, it would be assumed by the naive clinician that the treatment would always proceed as planned. However, the experienced clinician knows the treatment never follows the ascribed blueprints and we need to be ready to modify our thera-peutic protocols appropriately, based on the needs of the patient. Initial treatment planning of this patient empha-sized the use of felspathic “contact lens” porcelain lami-nate veneers for the maxillary anterior teeth. The patient was extremely pleased with the final result of the direct bonded composite-resin veneers on the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth and at this time has declined the recommended porcelain laminate bonded veneers. Although the clinicians are disappointed by this decision, the clinical option for aesthetic porcelain laminate veneers in the maxillary anteriors may be possible in the future to achieve the optimal luster and surface characteristics obtainable with laboratory fabricated porcelain laminate veneers. In summary, this case has been successfully com-pleted and was presented to our members at our recent annual treatment planning session by the general dentist who performed the restorative therapy. The treating clini-cian revealed his trepidations, anxieties, and challenges in documenting a case at this professional level. By shar-ing this knowledge and staying on the path with guidance from collective membership of the Gateway Study Club, the general dentist treating this case has learned experi-entially to perform at a higher level than he ever dreamed he could and he enjoys the admiration of his professional peers. It is with great pleasure that we now share this case with the Seattle Study Club network for examination and review. The authors would like to acknowledge Gerry Jacobi of Jacobi Lab, dental technician, for his skillful execution of the laboratory phase of treatment. The Gateway Study Club would like to thank all the clinicians who have visited our club in the past six years who have shared their time and knowledge with us. We especially would like to recognize Dr. Michael Cohen for his vision, Dr. John Kois for his systematic analysis, and Dr. Greg Lutke for his aesthetic interpretations.

George Duello is in the private practice of periodontics, St. Louis, MO and is the Director of the Gateway Study Club.

Jack Marincel is in the private practice of general dentistry, St. Louis, MO and is a member of the Gateway Study Club.

Kevin Thorpe is in the private practice of general dentistry, Clayton, MO and is a member of the Gateway Study Club.

19

SYMPOSIUM SYNOPSISSymposium 2006: Oren Harari

SUZANNE COHEN JD

How to Build Your Business for Competitive Success

Oren Harari, Ph.D., is a Professor of Manage-ment at the Graduate School of Business at the University of San Francisco. He is not only a lead-ing management consultant but also a respected author of many books, including the NY Times and Business Week bestseller, The Leadership Secrets of Colin Powell. In his entertaining and thought-provoking presentation, Dr. Harari talked about what small business owners must do to differentiate their businesses from com-petitors, and overcome commoditization of their products and services.

Circle the Wagons or Capitalize on New Ideas?

In the late 80s and early 90s, Harari was working with the recording industry. In those days, producing musical recordings on compact disks was a very profitable business for the music labels. The marginal cost of production for one cd was about 20 cents each once the master cd had been cut, and millions of duplicates were sold for $15 each. But at about the same time, he and others started to notice, far off in the distance, these “crackpots” who were sharing music using the MP3 data format. It was all in the public domain. He didn’t know what was going on, but he told his music-industry clients that he felt that something big was potentially “out there” because file-sharing and file compression technology could circumvent all the products and services they were offering. Only a few people were using it at the time, but that’s how critical masses grow.

Initially, the recording industry chose to ignore what was going on, and then it got big-ger and bigger. Fundamentally, customers were starting to capitalize on new technologies and new options before the established vendors (the music labels) were. That was the kiss of death for the recording industry, but instead of embrac-ing the new technology the industry executives circled the wagons and sent out lawyers to bring lawsuits against kids.

There was one person who saw all this and capitalized on it—Steve Jobs at Apple. He saw that he could put together a technology that

brought the artist, the record labels and the consumer together, with iTunes and the iPod. Suddenly, the record labels that had lost billions of dollars in missed opportunities over the past 6 or 7 years were scurrying to enter the 21st cen-tury. Meanwhile, this little thing called the iPod took off. It’s not that people were using music less; it’s where they were getting it.

In industry after industry market leaders often collapse because they ignore what is happening, deny it or demean it. Maybe your business is good right now, and you are saying “why fix it if it ain’t broke?” To do so is to violate a cardinal rule of free markets, which is that the numbers you see today just reflect what you did yesterday. If you assume that tomorrow is going to look like yesterday, you are very wrong. It probably won’t even look like today.

In the case of Apple, this strategy has been remarkably profitable for the company. In one year (2004-2005) revenues went up a modest $8.2 billion to $13.9 billion but net profit went from $276 million to $1.3 billion. Was there anything magical? No, it was all out in the public domain: the challenges, the opportunities, the technolo-gies and the potential partnerships. It took a mu-sic-industry outsider like Steve Jobs who wasn’t weighed down by the conventional wisdom to put it all together. The music labels should have “kicked butt” on the MP3 technology, but instead they ignored it. They stayed entrenched.

Can you think of an analogous situation in dentistry today? Is there something that is “out there” to be seen that consumers or competitors will adopt, that will change how dentistry is offered or “consumed” in the future? Of course there is, and you’ve got to find it, conduct the due diligence, and determine if there’s a way you can capitalize on it. If you want to be a market leader, you must see the trends that are beginning to advance before they hit critical mass, and leapfrog over the competition to dif-ferentiate yourself. If you don’t care about being a market leader then you can circle the wagons and keep doing things the way you have always done them. But don’t think that you can ignore, deny or demean what is “out there” and make it go away. As the ex-CEO of Harley Davidson, Rich Teerlink, has said, “It is not competitors that screw us up. It is our own complacency, arrogance or greed.”

20

The Perfect Storm of ChangeIn most every industry, there are a number of

factors colliding. Dentistry is no different. There are technological advances, rising customer ex-pectations and demographic changes. Any one of these can have huge implications, and can provide opportunities for differentiation. For example, demographic changes: the fastest grow-ing affluent population in the U.S. is Asian. Is anybody, in any industry, going after that market? Is anybody going after the Latino market? (The fastest growing group in the U.S.) Meanwhile, there are some 70 million baby boomers march-ing toward retirement. What does this mean for your dental practice? These baby boomers are not interested in geriatrics; they are willing to spend anything to stay young.

But in a copycat economy, there are more choices and more competitors. The convergence of all these factors is the “perfect storm” that means in every industry, rules are starting to change. What does this do to your customer loy-alty, to your “buzz?” Your biggest job as a leader or manager is to ask yourself continually, “How do I de-commoditize what in my customer’s ex-perience is probably becoming more and more of a commodity experience?” Most vendors want to believe that what they do is the greatest thing since the wheel. To the customers, everyone’s good…why should they stick with you? High quality is just the threshold. If you don’t have high quality, you’re dead. Customer satisfaction means nothing—it reflects the generic experi-ence when purchasing a commodity. Zero de-fects is the price of entry. The real issue is to go beyond the generic and the expected. Very few business owners spend the time and money to explore that uncharted space. This is not some-thing customers ask for, because they can’t even conceptualize it. Responding to the needs or wants of your customers or patients is what you have to do just to survive. To thrive, you have to lead them to a place that really matters — an “impossible” place. You know you have taken a customer to an impossible place when they say “wow.” Wow means glow, tingle, bewitch, dazzle, thrill and delight. Not words you hear in most office meetings when pleasing custom-ers is the topic. But customers aren’t asking to be taken to this “impossible” place; you have to educate them. If you ask them if they want the new, “impossible” thing or service that you have in mind, they will probably say “no.” Customers are notoriously bad at predicting what they will buy. How many people in the 1980s thought that

they would gladly pay $4 for a cup of specialty coffee in 2006? If you had held a focus group back then nobody would have said, “Yes, I’m absolutely dying to pay $4 for a cup of a coffee.” Meanwhile, Starbucks completely changed what the coffee experience is all about.

Start thinking about how you can make the experience fun. It’s not just an issue of doing one thing and then relaxing. Think in terms of the promises and the experiences. What you do must be pervasive, relevant and credible. When your customer can count on you for this kind of experience, that’s branding.

The Intersection of Innovation and LeadershipWhy is leadership important in all of this?

Because everything is about radical innovation and for that you need leadership. There is no way to do this if you are timid or if you are incrementally interested in improving. As Colin Powell says, “leadership is the art of accom-plishing more than the science of management says is possible.” Your job is not to be the chief organizer but rather the chief disorganizer. You have to keep looking under the surface even if you don’t like what you find. Don’t go looking for “no,” and never let your ego get so close to your position that when your position goes, your ego goes with it.

There are a number of attributes that make leadership a lot easier: One is optimism. Not “la-la land” optimism but what Harari calls “grounded optimism.” Another is having unreal-istic expectations. Of course leaders have unre-alistic expectations. Passion is also an attribute that makes leadership easier. Leaders often have a mission or “higher cause” and they are impa-tient to accomplish it. Sometimes the mission or cause may seem crazy to others. The beauty of free markets is that each of us can determine our own path to breaking from the pack. People may see certain choices as lunacy, but today’s lunacy is tomorrow’s conventional wisdom.

ConclusionDr. Oren Harari is a compelling presenter

who engages the audience with intriguing in-formation and personal insights gained from his many years of experience in a wide variety of industries. Although his presentation is not included in the DVD collection, he has a new book covering the same material, entitled “Break from the Pack: How to Compete in a Copycat Economy.” See also: www.harari.com.

21

SYMPOSIUM SYNOPSISThree Things No CEO Can Ever Delegate

Barbara Lehman is an entrepreneur, busi-nesswoman, author, lecturer, consultant and marketing coach who focuses on developing integrated communication strategies for clients in the healthcare industry. With a BS from Arizona State University in business adminis-tration, she has over 30 years of experience in strategic marketing and brand management. She is the author of two leading reference books on gender-specific marketing, Hitting the Right Nerve: Marketing Health Services and Reach-ing Women: The Way to Go in Marketing Healthcare Services. Her specialty is helping clients to re-discover their brands, to recognize those areas internally that support those brands or undermine them, and to market the brands to the appropriate audience. At Symposium 2006, she focused her presentation on “the three-legged stool,” a marketing philosophy she has developed.

IntroductionLehman began her presentation with the

observation that she has spent a career help-ing healthcare providers sell things that people don’t want to buy. It has been a challenge because practitioners don’t necessarily under-stand or appreciate marketing, but it is the next horizon for most professionals who have spent their lives becoming the best at what they do. Gypsy Rose Lee said, “you gotta have a gim-mick,” and many people seem to think that marketing is nothing but a gimmick. But when we speak of a competitive edge or differential, it means there needs to be something unique about you that is compelling and resonates with your market. Lehman believes that the advertis-ing “gimmick” is only a part of the marketing mix. It isn’t what really drives your marketing. Her purpose during her presentation was to explain how to put the meat on the bones, to really make marketing matter.

When Lehman started her career, commu-nications was part of journalism, and later it became part of the advertising department of the business school. During her career she has

Symposium 2006: Barbara Lehmanseen more and more attention being placed on the “stuff” that marketers do, as opposed to the thinking behind it. This has not been very satisfying for Lehman, or for clients.

Do Good Clinicians Need to Market Them-selves?

In the 70s, McGraw-Hill ran a print ad (seek-ing business publication advertisers) containing the following statements: “I don’t know who you are. I don’t know your company. I don’t know your company’s product. I don’t know what your company stands for. I don’t know your company’s customers. I don’t know your company’s record. I don’t know your company’s reputation. Now—what was it you wanted to sell me?” Unfortunately, this is what happens in the professions all too frequently.

All her career, Lehman has dealt with doc-tors who believe that if they are “good enough” clinicians, they don’t need to market. They seem to think marketing is a four-letter word and that it is something that is only done temporarily; something you do when you are really not good enough. But being good is not good enough, if people don’t know about what you do or why you do it. Furthermore, the bar is constantly being raised. In the “copycat” economy that Oren Harari described in his Symposium 2006 presentation, you have to differentiate yourself from competitors. You have to be a brand, which is more than your logo, sign, letterhead, brochure, etc. Those are just visual cues. Your brand is what your customers believe you are — what you represent to them. It is the total-ity of the experience that your customers have with you, that makes it meaningful. Being the brand gives you choices, including being able to charge more, or having a location that becomes a destination.

For example, denim jeans are mass-produced all over the world. What happens when you put the brand on the back pocket? Now you can put a higher price on it. People want the perception of what the brand represents. The value of being a brand is that it puts you in the driver’s seat.

SUZANNE COHEN JD

22

What You Can’t DelegateThe three things you can’t ever delegate as

a CEO/dentist: the story that you are telling, the credibility that supports that story, and the message that you are marketing. Positioning is your story and your story is your brand. This doesn’t mean that you can’t have others involved in the creation of materials to tell your story, but you cannot delegate the actual story.

How do you get to your story? You need to uncover the buried treasure that is who you are. You don’t necessarily know it, though you may think you know it. Most doctors think their story is their credentials or the procedures they do. The story has to be recreated from the point of view of your ideal customer. How you create your story in the context of the world you’re living in, is your brand.

The Three-Legged StoolPositioning, reputation management and vis-

ibility are the legs of the three-legged stool.Positioning includes who you are, the stand

you take, what you are great at, and why people come to you. What is the story that your loyal patients have about you? Again, it’s not your view of your story; it’s your patients’ view of your story. Why would they never go anywhere else? That is your story.

Reputation management is how you make that story true. Many times, practitioners dis-tance themselves from reputation management. It includes such things as whether you have the right people helping you to make it “show time” every day. Does your team support your story and your brand? Is the administration of your office in harmony with your story? If you don’t pay attention to that, or if you don’t want to be bothered with that, it will come back and bite you. Your team will either support your story, or sabotage it when you’re not looking.

Visibility is how you tell your story, and to whom. This is the tail of the dog, not the dog, though many people think it is the dog. Often when doctors think they need more money, more patients, etc., they start with the mar-keting visibility rather than the story. This is where they go wrong and end up wasting their advertising dollars.

Understanding Your Target MarketTo whom do you tell your story? The profile

of your ideal patient is:• Hardworking and involved• Baby boomers age 55-64• Independent, positive and financially

stable• Informed and educated

Once you understand to whom you want to tell your story, you need to determine what that group wants. According to Lehman, what matters to this group is:• Brand confidence, not just brand

recognition• Messages that are meaningful and

memorable • Uniqueness, rather than one-size-fits

all • Solutions to aging and lack of

attractiveness• Comprehensive, whole picture

services• That you’re the “best” at something• The big picture on financing, timing

and results• Personal service and experience: no

rookies on the front line• Options, choices, alternatives• Convenience: on-site availability of

needed supplies• Consistency: don’t change what they

love• Office harmony and respect for their

time

ConclusionLehman has excellent information that can

help dentists clarify and redirect their market-ing efforts. Her “three-legged stool” philosophy of branding is unique and innovative. By break-ing down branding into its essential compo-nents, Lehman succeeds in making marketing concepts meaningful and understandable. She would be an asset to any healthcare professional seeking a consultant to develop or enhance a marketing plan.

27

SYMPOSIUM SYNOPSISThe Power of Intention

Wayne Dyer is a well-known author and speaker whose focus is on metaphysics and self-development. He is often seen on PBS specials, Oprah, and other television programs. At Symposium 2006, he spoke about intention as a force in the universe that allows the act of creation to take place — a field of energy that you can access to tap the power of your highest self.

The Organizing Force of the UniverseDyer’s fundamental belief is that there are no

accidents in this universe, and that the universe is supported by an intelligent, organizing force. It doesn’t matter what we call the source of this intelligent energy. According to Dyer, one of the most important teachings that has been provided for us by the quantum physicists of the 20th century, is that the building blocks of nature are not atomic but rather sub-atomic. As Deepak Chopra has said, “quantum phys-ics is not only stranger than you think it is, it is stranger than you can think.” The particles called “quarks” are so tiny that trillions of them can fit on the head of a pin, and they behave in strange ways. It is almost impossible to be-lieve that everything we need for our journey through life is present in the tiny little drop of protoplasm that begins us. As healthcare provid-ers, we must be in a complete state of awe at all times. The philospher Rumi said, “sell your cleverness, and purchase bewilderment.” In one split second we go from “no where” to “now here.” And none of us escape the fact that we will ultimately go back to “no where.”

Dyer says that as one looks at sub-atomic particles and tries to figure them out, and then turns away and looks again, one changes what one is observing. The particles change how they behave. At the sub atomic level, when you change the way you look at things, the things that you look at change. In Dyer’s view, the same is true for us.

Manifesting What You ContemplateIt doesn’t matter who squeezes an orange,

what you get out of it is what is inside. If we

extend that metaphor to ourselves; if someone puts pressure on us that we don’t like, what comes out of us is what’s inside. If it’s anger, ha-tred, bitterness, fear, tension, anxiety or stress, it comes out not because of what someone did to us but because that’s what’s inside. In order to change the bad things like depression, stress and anxiety that are being expressed in our lives, we have to clean up the inside.

Dr. Abraham Maslow was Wayne Dyer’s men-tor, and he taught Dyer how to put his intention on what it was that he wanted to manifest for himself in his life. According to Dyer, Maslow talked a lot about inspiration, and his teachings came from one of the great thinkers of the last century, C. G. Jung, who wrote “Modern Man in Search of a Soul.” In that book Jung spoke about how human beings evolve to a higher level. The pinnacle of this is self-actualization. Self-actualization is part of the pyramid that in India, they call Siddhi consciousness. This is a place where we reconnect ourselves back to the place or source from which we came. If we all came from the field of spirit, we must be like where we came from. This is the source that is available to all, a source of beauty, kindness and inspiration.

When you get to this place of spiritual evolu-tion, your world starts to change. Things start to happen. You begin to transform yourself in ways that didn’t happen before. Your thoughts begin to manifest very quickly. This capacity is within all of us — to manifest, and to attract things into our lives from seemingly nowhere.

How does it work? Maslow said, “when you put your attention on what you want to mani-fest, it is the very attention that you give to it that makes it manifest itself.” By passionately believing in it, we create it. That is the differ-ence between people who move at higher levels, and those who can’t even begin to contemplate it. You get what you think about, whether you want it or not. The most important decision you have to make is whether you believe we live in a friendly universe or a hostile universe. If you believe that it is friendly, then you put your attention on that and good things will come to you. If you believe it is hostile, then you will attract hostility and unhappiness. We become what we think about, all day long. Once you understand this, you start getting “real careful”

Symposium 2006: Wayne Dyer

SUZANNE COHEN JD

28

about what you think about.In Dyer’s view, all of this is about energy.

According to Dyer, every thought that we have has an energy component to it. One of Dyer’s secrets and recommendations to others is to avoid all thoughts that weaken you. Contem-plate what you intend to create rather than contemplating the possibility that it might not show up. Since it is in the contemplation of an idea that we create it ourselves, our thoughts must be in complete harmony with what we want to manifest.

Dyer is a strong believer in the practice of yoga as a way to reach higher consciousness and to reconnect with the source. He has found it to be one of the most healing and inspiring practices in his life. In yoga, you learn that there is nothing that you can’t do. The teachers are always telling you, “you’ll be doing that” when there is some stretch or physical position that you can’t do right now. Yoga is an ancient teaching that means “union” or connecting back to the source. According to Dyer, the an-cient Indian yogi Patanjali said “when you are inspired by some great purpose, some extraor-dinary project, all of your thoughts break their bonds. Your mind transcends limitations, your

consciousness expands in every direction, and you find yourself in a new and a great and a wonderful world. Dormant forces, faculties and talents come alive and you discover yourself to be a greater person by far, than you ever dreamed yourself to be.”

Dyer ended his presentation by focusing on the difference between aligning oneself with the source and aligning oneself with ego. He pointed out that we live in a society where many people think that they are what they do, what they have, and what others think of them. The problem here is that if they lose what they have, or cease doing what they do, then they are no more. This is what Patanjali called “the false self” — what other philosophers called “ego.” According to Dyer, we can either live our lives being a host to the source, or a hostage to ego.

ConclusionDyer is an inspiring and motivational

speaker. To this reporter, many of the ideas and beliefs he presented made intuitive sense while others were more difficult to accept. Neverthe-less, his presentation at Symposium 2006 was appreciated by all in attendance.

Remembering Dr. Bob Stultz

Iwas saddened to learn that Dr. Ellwood Robert “Bob” Stultz passed away suddenly and unexpectedly on June 23, 2006. He was just 62 years old. Bob was a talented periodon-tist and an early adopter of new ideas and technologies. He was committed to life-long

learning and to the Seattle Study Club concept. He was one of our very first Seattle Study Club Directors, and he kept with it for many years before deciding that he wanted to run his Study Club independently. We remained friends and although we didn’t speak that often, we were always glad to renew acquaintances at the various professional meetings we both attended.

Bob had a tremendous sense of humor and was usually smiling and laughing. He was a tall good-looking guy who was always exquisitely dressed. Bob and his wife Wendy were a great couple. Wendy herself has great style and together they were the type that you would turn and look at twice. According to his obituary in the Marin County Independent Journal, Bob met Wendy when he moved to California in 1978, after serving in the U.S. Navy. They were happily married for 28 years.

In addition to having a wide circle of friends and professional colleagues, it is clear that Bob was also beloved by his patients. His “guest book” on the internet contains many ex-pressions of shock and sympathy from his patients, and they all mention how much they loved him and will miss him. My heart goes out to Wendy and the Stultz family at this time of sadness and grief.

—Michael Cohen DDS MSD Editor-in-Chief

29

Age at Initial Presentation: 39Initial Presentation: July 2004Active Treatment Completed: August 2005

Introduction and Background

A 42 year-old healthy male was referred from the Univer-sity of Washington’s Undergraduate Dental Clinic to the Graduate Prosthodontics Clinic with a failing three-unit fixed partial denture prosthesis (FPDP). His chief com-plaint was, “ I am concerned about my front teeth and I want a fixed restoration.” His only other concern was an occasional bad taste. The patient also had a previous consultation at the Graduate Endodontics clinic, where he was diagnosed with severe inflammatory external resorption of tooth # 7 and possible resorption of tooth # 9. Nevertheless, he claimed to be unaware of the amount of bone loss and the poor prognosis for teeth #’s 7 & 9. The patient admitted that from the time the FPDP was cemented, he had not flossed between the abutments. The main objectives of treatment were to eliminate the existing pathoses, to restore the damaged soft and hard tissues, and to provide an aesthetically pleasing restoration to fulfill the patient’s aesthetic and functional expectations.

Diagnostic Findings

Clinical examination revealed lack of adequate oral hy-giene. The gingival tissue surrounding the abutments and the pontic was erythematous, edematous and hyperplas-tic. (Fig. 1) Probing depths on the mesial aspects of teeth #’s 7 & 9 were up to 11 mm, with bleeding upon probing. Suppuration was noted upon palpation, as well as a soft tissue buccolingual defect (Seibert Class I) in the pontic area. The gingival margins were leveled, except for tooth # 11, which showed 3 mm of gingival recession. This tooth had a class V composite-resin restoration performed by his former dentist, who accidentally caused a mechanical pulp exposure and therefore a root canal treatment was needed for tooth # 11. The presence of black triangles was also noted between teeth #’s 6 & 7 and teeth #’s 8 & 9.

Special Report 8Treating Clinicians: Drs. Rosario Palacios and Ariel Raigrodski, and Vincent Devaud, MDC

The metal-ceramic FPDP demonstrated class II mobil-ity according to Miller. Open margins were evident at the buccal and lingual aspects. The FPDP was overcontoured facially as compared to the adjacent natural teeth, and the pontic design adjacent to the site of tooth # 8 was a modified ridge lap design, resting on top of the ridge rather than emerging from within the alveolar process. Electric pulp testing, percussion and palpation tests were performed with no response for teeth #’s 7 & 9. The patient was missing his second bicuspids. He was classified as an Angle Class I malocclusion (first mo-lar and canines) on the right side, and an Angle Class II (first molars and canines) on the left side, where a poste-rior crossbite was also noted. The horizontal overlap was 1.5 mm. The vertical overlap was 1.0 mm. Aesthetic analysis demonstrated that the patient had an average to low smile line, with minimal gingival display at maximum smile. The maxillary dental midline was co-incident with the facial midline. However, the mandibular midline deviated 3 mm to the left side. The patient did not demonstrate any other significant clinical findings. Radiographic examination showed severe vertical and horizontal bone loss on the mesial aspect of teeth #’s 7 & 9, and on the distal aspect of tooth # 9, with mild horizon-tal bone loss in the adjacent teeth. A radiopaque mass was noted under the pontic site, which according to the patient, corresponded to a hard tissue graft done at the time of the extraction of tooth # 8 about 6 years ago.

Figure 1

30

D i a g n o s i s a n d P r o g n o s i s • Localized severe periodontitis.

• External inflammatory resorption for tooth # 7 and possible surface resorption for tooth # 9.

• Guarded prognosis for tooth # 10.

• Poor prognosis for teeth #’s 7 & 9.

S u m m a r y o f C o n c e r n s• How to provide the patient with an aesthetic

soft-tissue restorative interface?

• What would be the preferred definitive restora-tion to answer the patient’s aesthetic concerns as well as his functional needs?

• How to provide predictable longevity to the selected restoration?

April 2004

September 2005

31

Treatment Plan

Treatment options were discussed with the patient. Soft-tissue augmentation and a tooth borne FPDP using teeth #’s 6, 7p, 8p, 9p, 10 to 11 was considered since tooth # 10 was a poor abutment. An implant-supported restora-tion was considered as well. However, given the need for extensive bone grafting procedures and their predict-ability for creating a natural soft-tissue profile around the prospective area of implant placement and because of the patient’s preference, this option was discarded. Two restorative options were considered for restoring the partially edentulous space immediately after the ex-tractions: a preparation of teeth #’s 6, 10 & 11 and delivery of a provisional FPDP; or an interim acrylic-based remov-able partial denture (RPD). The latter option was selected to avoid the maintenance of a long-term provisional FPDP risking the integrity of the prospective abutments due to the secondary caries. Due to the Seibert Class I defect as well as the cur-rent vertical bone loss and prospective extractions, it was decided to perform soft-tissue augmentation to enhance the aesthetic result. The patient was sent for a consulta-tion with the Periodontics Department at the University of Washington.

Phase I: Surgical Phase

An interim acrylic-based RPD was fabricated to replace the missing teeth after the extractions. The FPDP was