Visual Rhetoric in Advertising: Text-Interpretive ......communicate that content, and that is not...

Transcript of Visual Rhetoric in Advertising: Text-Interpretive ......communicate that content, and that is not...

Visual Rhetoric in Advertising:Text-Interpretive, Experimental, andReader-Response Analyses

EDWARD F. MCQUARRIEDAVID GLEN MICK*

Text interpretations, two experiments, and a set of reader-response interviewsexamine the impact of stylistic elements in advertising that form visual rhetoricalfigures parallel to those found in language. The visual figures examined here—rhyme, antithesis, metaphor, and pun—produced more elaboration and led to amore favorable attitude toward the ad, without being any more difficult to com-prehend. Interviews confirmed that several of the meanings generated by infor-mants corresponded to those produced by an a priori text-interpretive analysis ofthe ads. However, all of these effects diminished or disappeared for the visualtropes (metaphor and pun) in the case of individuals who lacked the culturalcompetency required to adequately appreciate the contemporary American adson which the studies are based. Results are discussed in terms of the power ofrhetorical theory and cultural competency theory (Scott 1994a) for illuminating therole played by visual elements in advertising. Overall, the project demonstratesthe advantages of investigating visual persuasion via an integration of multipleresearch traditions.

Visual elements are an important component of manyadvertisements. Although the role of imagery in shap-

ing consumer response has long been recognized (Green-berg and Garfinkle 1963), only recently have visual ele-ments begun to receive the same degree and sophisticationof research attention as the linguistic element in advertising(Childers and Houston 1984; Edell and Staelin 1983; Mey-ers-Levy and Peracchio 1992; Miniard et al. 1991; Scott1994a). The area is now characterized by conceptual andmethodological diversity, with a variety of new propositionsand findings emerging.

Historically four approaches can be distinguished, eachwith its own strengths and weaknesses. Thearchival tradi-tion is perhaps the oldest (e.g., Assael, Kofron, and Burgi1967). Studies in this vein gather large samples of adver-tisements and conduct content analyses to describe thefrequency with which various types of visual elements

appear. Archival studies may also report correlations be-tween the presence of certain elements and specific audi-ence responses (e.g., Finn 1988; Holbrook and Lehman1980; Rossiter 1981). The weakness of this approach is thatit is primarily descriptive and provides only weak evidencefor causality. Also, the specific visual elements investigatedtend to cover a wide range and are not generated by anytheoretical specification.

The experimentaltradition systematically varies eitherthe presence or absence of pictures per se (e.g., Edell andStaelin 1983) or the nature of some particular visual element(e.g., Meyers-Levy and Peracchio 1995) or the processingconditions under which subjects encounter particular visualelements (e.g., Miniard et al. 1991). The strength of thistradition is rigorous causal analysis combined with theoret-ical specification. However, the consumer responses elicitedtend to be abbreviated or impoverished, and theoreticalspecification is mostly applied to consumer processingrather than to the visual element per se.

The reader-responseapproach emphasizes the meaningsthat consumers draw from ads (e.g., Mick and Buhl 1992;Mick and Politi 1989; Scott 1994b). Extended depth inter-views are sometimes used to show the rich and complexinterplay between elements of the ad and consumer re-sponses. Weaknesses include a limited ability to conductcausal analysis and a relatively vague specification of howspecific types of ad elements can be linked to particularkinds of consumer meanings.

*Edward F. McQuarrie is associate professor of marketing and associatedean of graduate studies at the Leavey School of Business, Santa ClaraUniversity, Santa Clara, CA 95053. David Glen Mick is associate professorof marketing at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706. Theauthors, both of whom contributed substantially to the research, would liketo thank the marketing groups at the University of Arizona, the Universityof Michigan, and the University of Wisconsin, the Faculty Colloquium atthe Leavey School, and Barbara Phillips for their insightful comments, andHakshin Chan and Raena Shioshita for assistance with data collection.Mick would also like to thank the Dublin City University Business Schoolfor its support during completion of this project when he served as theEndowed Chair of Marketing (1997–98).

37© 1999 by JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH, Inc.● Vol. 26 ● June 1999

All rights reserved. 0093-5301/00/2601-0003$03.00

The text-interpretiveperspective draws on semiotic, rhe-torical, and literary theories to provide a systematic andnuanced analysis of the individual elements that make upthe ad (e.g., Durand 1987; McQuarrie 1989; Scott 1994a;Sonesson 1996; Stern 1989). It treats visual and verbalelements as equally capable of conveying crucial meaningsand as equally worthy of differentiation and analysis. How-ever, this tradition rarely collects or analyzes advertisingresponses from consumers. This raises the issue of whetherthe elaborate systematization of text elements actually mapsonto the responses of consumers in an illuminating way.Similarly, causality is more often assumed than demon-strated.

This brief summary suggests that there is ample need andopportunity for investigations that span multiple traditionsand draw on the strengths of each. Although several of theseperspectives have been closely linked historically (e.g.,rhetoric, semiotics, literary theory, reader-response), with agreat deal of mutual borrowing, others have rarely crossedpaths (e.g., semiotics, laboratory experiments). This articleinterweaves two strands of the text-interpretive tradition(rhetoric and semiotics) with the experimental tradition andthe reader-response approach. We show that patterns ofstylistic variation parallel to the figures of speech docu-mented in language have a reliable impact on consumerresponse, and we explain these results using a model of theconsumer as an astute and active reader of advertising texts.Specifically, we present a rhetorical and semiotic analysis ofvisual figures in advertising, test predictions from this text-interpretive analysis in two experiments, and supplementthese experiments by means of a reader-response analysisusing phenomenological interviews. This multimethod ap-proach builds on previous attempts to show the value of acritical pluralism for consumer research (Hunt 1991; Mc-Quarrie and Mick 1992).

TEXT STRUCTURE AND CONSUMERSAS READERS

As a reader the consumer approaches advertisements ascomplex texts to be interpreted (Scott 1994b). Approachedas texts, ads may be ignored or engaged, disdained orenjoyed, critiqued or endorsed. Of course, these consumerreadings will be shaped by idiosyncratic factors as well astext structure (Eco 1979). Nonetheless, we assume that textstructure functions reliably as a causal agent. That is, textstructure tends to shape or direct consumer response, eventhough it does not, strictly speaking, fix or determine it. Theunderlying model is probabilistic; although any randomlyselected consumer may or may not read an ad text in a givenway, in the mass, more consumers than not will read a textin a way that is predicated on the text structure itself.

Text structure is an encompassing term that refers to anydiscriminable pattern in any part of the manifest ad. Ourfocus here is on the more narrow concept of stylistic vari-ation. We define style to include all those aspects of an adthat can be varied independently of the assertion of a brand-attribute linkage, that is, message content. Once we createan ad text that communicates a certain brand-attribute link-

age, any subsequent change to the ad that continues tocommunicate that content, and that is not itself simply theassertion of a second brand-attribute linkage, is by defini-tion a change of style. The separation of style from contentin no way implies that ad style cannot convey information,cannot add meaning, or cannot concern the brand. Stylisticvariation in advertising can do all these things. In fact, froma semiotic perspective, it is not possible to change the styleof an advertisement without also changing some of itsmeaning. By contrast, it should be possible in an experimentto hold the assertion of a central brand-attribute linkageconstant while varying aspects of the ad’s style. Becauseconsumers read ad texts for style as well as content, such amanipulation of style should have a predictable impact onconsumer response.

Given our overall commitment to linking the text-inter-pretive and experimental traditions, rhetorical theory ap-pears ideally suited to the task of generating specific pre-dictions, amenable to experimental test, about the impact ofstylistic variation in advertising visuals. With its semioticfoundation, the rhetorical tradition can provide a wealth ofideas for differentiating and integrating aspects of visualstyle (see, e.g., Durand 1987). Furthermore, the practicalbent that has characterized rhetoric from its beginningsfacilitates experimentation—rhetoricians have alwayssought the particular style most able to compel an audienceresponse. Lastly, building on the link to the reader-responsetradition developed by Scott (1994b), rhetorical analysis canalso be applied to generate a rich account of the consumermeanings that visual style might be expected to potentiate.

In the following sections we first define, explain, anddifferentiate various types of rhetorical figures, concludingthat a visual embodiment of this historically linguistic no-tion should be possible. We then develop the impact onconsumer response that can be expected upon exposure tovisual rhetorical figures in advertising. This impact in turnderives from the meanings set in motion by the text struc-ture of the visual figures. Hence, we provide an a priori textinterpretation that identifies some of these meanings in thecase of the stimuli constructed for this project. That inter-pretation then provides a context for the empirical studies.

RHETORICAL FIGURESIN ADVERTISING

A rhetorical figure is an artful deviation, relative to au-dience expectation, that conforms to a template independentof the specifics of the occasion where it occurs (McQuarrieand Mick 1996). Familiar examples of figures of speechinclude rhyme and metaphor; dozens more are catalogued inclassical sources (Corbett 1990). Because they are artful,rhetorical figures are not errors or solecisms; and becausethe template is independent of the specific content asserted,figures may be considered a stylistic device. Under thisconception, rhetorical figures could be advantageous to ad-vertisers for several reasons. Most important, artful devia-tion adds interest to an advertisement. For instance, a cig-arette ad that proclaims “Today’s Slims at a very slim price”should be more engaging to the consumer than one that

JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH38

reads “Today’s Slims at a very low price.” Moreover, theadvantage of any stylistic device is that it can potentially beadded to an ad without disturbing the underlying attributeclaim—thus, in the example above, the rhetorical figure stillcommunicates a low-price positioning for the brand butdoes something more as well.

Many variations in advertising style are one-shot affairs,specific cases sampled from a plenitude of possibilities. Bycontrast, rhetorical figures are generated by a limited num-ber of rhetorical operations, and this makes it possible toconstruct an overarching theory of the causal impact offigures, an enterprise that would be intractable if one had towork with isolated heterogeneous instances of stylistic vari-ation. The limited number of figures also poses the intrigu-ing possibility that the entire set can be generated from asingle compact theoretical specification. McQuarrie andMick (1996) suggested that the wealth of rhetorical figuresfound in advertising could be organized into a three-leveltaxonomy, with all the figures located at a given nodesharing certain formal properties. These properties would inturn be the key determinants of consumer response to fig-ures.

The top level of their taxonomy, which includes all fig-ures, is characterized by the property of artful deviation asdefined above. It seems likely that the degree of deviationpresent in specific instances of figures may vary over a widerange and systematically across types of figures, with acorresponding difference in impact on consumers. Thus,there exists a gradient of deviation, with more deviantfigures having a greater impact, up to some point of dimin-ishing returns. In fact, McQuarrie and Mick (1992, experi-ment 2) showed that a rhetorical figure could be so deviantas to have a negative impact, creating confusion rather thaninterest.

At the second level of the taxonomy, schemes are distin-guished from tropes as two different modes of figuration.Schemes deviate by means of excessive regularity. Forexample, rhyme, with its unexpected repetition of sounds, isa scheme. Thus, an ad for motor oil that proclaims “Perfor-max. Protects to the Max” would hold an advantage over theless deviant “Performax. The Top Protection.” Tropes de-viate by means of an irregular usage. Metaphors, with theirliterally false but nonetheless illuminating equation of twodifferent things, and puns, with their accidental resem-blances, are tropes.1 Thus, the punning headline by Ford,“Make fun of the road,” can be construed either as aninvitation to scorn or to enjoy. This deviant construction,whose oscillating meanings cannot be completely pinneddown, would hold an advantage over the more straightfor-ward “Dominate the road” or “Enjoy the road.”

At the third level of the taxonomy, specific rhetoricaloperations, which may be simple or complex, serve toconstruct schemes or tropes. Repetition and reversal are thesimple and complex operations that construct schemes (ex-amples are rhyme and antithesis, respectively), while sub-stitution and destabilization are the simple and complex

operations that construct tropes (examples are ellipsis andmetaphor, respectively). In the aggregate the four rhetoricaloperations provide four different opportunities for addingartful deviation to an ad.

The definition of rhetorical figures as templates indepen-dent of the specifics of individual expressions indicates thatvisualrhetorical figures ought to be possible. Nothing in thefundamental definition of a figure either requires a linguisticexpression or precludes a visual expression. In fact, the ideaof a visual figure has ancient roots in art theory (Gombrich1960; Scott 1994a). Durand (1987) may have been the firstto propose a comprehensive catalog of visual figures. Un-fortunately, most prior work in the text-interpretive traditionhas focused on visualmetaphorto the exclusion of otherfigures (e.g., Forceville 1995; Kaplan 1992; Kennedy,Green, and Vervaeke 1993; Phillips 1997). Of the manyother figures routinely discussed in the context of linguisticrhetoric, only the pun has been investigated in visual form(Abed 1994; McQuarrie and Mick 1992).

In light of the various taxonomies of rhetorical figuresnow available (e.g., Dubois et al. 1970; Durand 1987;McQuarrie and Mick 1996), the most compelling demon-stration of the power of visual figures would utilize multiplefigures, rather than concentrating on a single instance suchas metaphor, and would predict distinct impacts for differenttypes of figures, rather than lumping all figures together. Asuccessful experimental investigation along these lineswould testify both to the cross-modal generality and explan-atory power of the idea of a rhetorical figure, and to thepotency and flexibility of visual style as a means of alteringconsumer response to advertising.

IMPACT OF VISUAL RHETORICALFIGURES

In this article we argue that rhetorical figures, in whateverform, can be expected to have two primary effects onconsumer response. The first is increased elaboration andthe second is a greater degree of pleasure.

Elaboration

In cognitive psychological terms, elaboration “reflects theextent to which information in working memory is inte-grated with prior knowledge structures” (MacInnis andPrice 1987, p. 475). Broadly speaking, elaboration indicatesthe amount, complexity, or range of cognitive activity oc-casioned by a stimulus. As noted by MacInnis and Price,elaboration can take the form of either discursive thought orimagery. When a rhetorical figure is embodied visually, it isreasonable to suppose that both discursive and imagisticelaboration may result.

The idea of elaboration can be readily translated intointerpretivist language, as the extent to which a readerengages a text or the amount of interpretation occasioned bya text or the number of inferences drawn (Mick 1992). Thefundamental property by which all rhetorical figures stim-ulate elaboration is their artful deviance. As texts marked bydeviance, rhetorical figures indicate to readers that they

1For a more extensive list of schemes and tropes found in advertising,see Leigh (1994) and McQuarrie and Mick (1996).

VISUAL RHETORIC IN ADVERTISING 39

should consider the communicator’s reasons for so markingthe text (text marking is discussed in detail by the semioti-cian Mukarovsky [1964]). As Sperber and Wilson (1986)argue, audiences always assume relevance on the part of thecommunicator. Hence, if the text is marked, then the com-municator must have wanted the audience to take note of it,and the surrounding context should allow the reader tointerpret correctly the reason the text was marked, providedthe reader makes a competent effort. The assumption ofrelevance enables Sperber and Wilson to explain why theliteral falseness of metaphor is only a problem for logi-cians—ordinary readers readily recognize that the commu-nicator has deviated from expectation in order to make apoint. In the case of metaphor, the point is typically that avariety of predications should be entertained, with no one ofthem fully adequate to capture the communicator’s intent.

The concepts of deviation and marking can in turn betranslated back into more conventional psychological terms.Deviation can be understood as the stimulus property ofincongruity (Berlyne 1971). Incongruity in ad stimuli isknown to provoke elaboration (Heckler and Childers 1992).Hence, it should be possible to demonstrate experimentallythat an ad containing a visual rhetorical figure will producea greater degree of elaboration relative to a baseline ad thatlacks the figure.

It should also be the case that tropes will produce agreater increment in elaboration than schemes. McQuarrieand Mick (1996) argued that tropes and schemes fall atdifferent points on the gradient of deviation, with schemeson average less deviant from expectation than tropes.Schemes are hypothesized to be less deviant than tropes fortwo reasons. First, in semiotic terms schemes are overcodedwhile tropes are undercoded. This means that tropes areincomplete, requiring the reader to fill in a gap, whileschemes contain redundant cues that more directly suggestmultiple meanings. Within the semiotic tradition undercod-ing is believed to mark the text more strongly (Eco 1979).Second, the excessive regularity of schemes is constructedfrom sensory elements (e.g., the duplication of syllables inrhyme), while the irregularity of tropes is constructed fromsemantic elements (e.g., the different meanings broughttogether in a metaphor). A depth of processing argumentcan thus be framed to support the claim that tropes are moredeviant than schemes (experimental evidence that sensoryand semantic elements differ in depth of processing isprovided by Childers and Houston [1984]). If deviation is infact the primary formal property of rhetorical figures thatcauses elaboration, then in an experimental setting it shouldbe possible to show both a main effect for the presence of avisual figure and also an interaction in which the effect islarger for tropes than schemes. These effects are condi-tioned on the deviation being neither so minimal that it goesunnoticed nor so extreme as to be incomprehensible.

Pleasure

Artful deviation is also the cause of the pleasure producedby rhetorical figures, but here it is their artfulness that iskey. In semiotics a fundamental tenet is that readers enjoy a

pleasure of the text (Barthes 1985). Texts that allow multi-ple readings or interpretations are inherently pleasurable toreaders. Texts that are simple and one-dimensional are lesslikely to be sources of pleasure. One may take pleasure fromthe referent of such a text, but the text itself does not offerthe reader pleasure. Similarly, texts that are opaque or toodifficult to decipher also fail to give pleasure. It is texts thatresist simple readings while showing the way to morecomplex readings that are most likely to give pleasure toreaders. Texts of this kind may be said to have poetic oraesthetic value. The initial ambiguity is stimulating, and thesubsequent resolution rewarding (cf. Berlyne 1971; Eco1979; McQuarrie and Mick 1992; Peracchio and Meyers-Levy 1994).

The notion of a pleasure-of-the-text is readily linked tothe concept of attitude-toward-the-ad (Mick 1992). In-creased enjoyment while processing the ad text makes itprobable that consumers will regard the overall ad morefavorably. The importance of this transference is that plea-sure-of-the-text is exactly the kind of text-interpretive ideathat cries out for empirical testing. Of course professionalsemioticians derive a great deal of pleasure from teasing outcomplex strands of meaning from great literature—but whatabout naive consumers encountering ordinary advertise-ments? These consumers’ motivation to process advertise-ments, their opportunity to process at any length, and eventheir ability to process are all open to question. It is easy toimagine rhetorical figures, especially those worked into thevisual background, as having no effect on consumers at all,however delightful these figures may be to semioticians andother interpretivists. Although some positive evidence doesexist for the case of puns (McQuarrie and Mick 1992), andfor processes of aesthetic resolution more generally (Perac-chio and Meyers-Levy 1994), it remains an open questionwhether the simple presence or absence of a visual figurecan influence consumer attitudes toward the ad (Aad).

If the text-interpretive account is correct, then it can behypothesized that tropes will produce a greater incrementthan schemes on Aad as well as elaboration. This followsfrom the role of deviation in creating pleasure-of-the-text.There is no pleasure if the text lacks art; but pleasure comesfrom the successful resolution of incongruity, and theamount of incongruity, and hence the degree of resolutionpossible, is a function of the extent of deviation. As before,the assumption of greater deviation in the case of tropesyields the prediction of an interaction such that schemes andtropes are both able to produce a more favorable Aad rela-tive to baseline ads lacking visual figures, but the incrementis larger for tropes.

A PRIORI TEXT INTERPRETATION

Our text-interpretive analysis of the visual aspects of thefour rhetorical ads in Table 1 is based on the synthesis ofthree traditions. The first, of course, is rhetoric, drawing onthe fundamental character of rhetorical figures, their varioustypes, and the underlying operations that construct them, asoutlined above and discussed in detail by McQuarrie andMick (1996). The second tradition is the semiotic doctrine

JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH40

that addresses advertising as a selection and combination ofsigns that have varying natures and functions in communi-cation and meaning (see Mick 1986; Williamson 1978). Theselection issue is related to the concept of paradigmaticrelations (how signs come from preset groups, within whichthere are similarities and dissimilarities, e.g., the paradigmof kitchenware plates such as china, clay, plastic, paper,etc.). The combination issue concerns the concept of syn-tagmatic relations (how signs selected from different para-digms are organized, e.g., the placement of plates, utensils,glasses, napkins, etc., in order to compose a table setting).Thus, as both the rhetorical and semiotic traditions empha-size, the specific elements of ads serve as signs that havebeen selected from among others and combined in onemanner rather than another by the advertiser so as to com-municate meanings about the brand, the product, and/or theuser.

A sign, by its nature, always stands for something,broadly termed its “object.” Although many varieties of this“stand for” relation have been identified, iconic, indexical,

and symbolic relations constitute three of the most funda-mental. Iconic signs resemble their objects, usually throughtopological similarity (e.g., a photograph), leading to cor-responding reactions. Indexical signs refer to their objectsby virtue of a causal relation (e.g., smoke and fire), ofteninvolving some kind of existential contiguity between thesesigns and their objects. Symbolic signs bear an arbitraryrelation to their objects constructed solely through consen-sus and convention (e.g., words and their meanings). A finalcrucial point to emphasize is that most signs in daily lifeparticipate simultaneously in more than one “stand for”relationship, rarely reducible to a single iconic, indexical, orsymbolic connection.

The third tradition our interpretations draw from may becalled the cultural approach (cf. Scott 1994b). That is, whenanalyzing the text of a highly visual advertisement, it isessential not to view the assemblage of signs as a straight-forward copy of reality that viewers apprehend directly anduniformly. Rather, the experience of advertising is a func-tion of a complex process facilitated by tacit, culturally

TABLE 1

TEXT-INTERPRETIVE ANALYSIS OF EXPERIMENTAL STIMULI

Ad stimulusFigurative

modeRhetoricaloperation

Description of rhetoricalfigure

Semiotic relations amongkey elements Manipulation

Mascara ad Scheme Repetition Visual rhyme—contoursof eye lashes and furecho one another

Iconic relation between sablefur and lashes withmascara;Indexical relation betweenfur and “soft”;Symbolic relationshipbetween fur and wealth,sophistication

The fur ends were airbrushed toremove spikiness, eliminatingthe repetition of contours

Yogurt ad Scheme Reversal Visual antithesis—convex contour ofbeach ball juxtaposedwith concave figure ofwoman

Iconic relation contrasts fatbeach ball with slenderwoman;Indexical relation betweenball and fun on the beach;Symbolic relationshipbetween a slender figureand attractiveness

The beach ball was cropped tocreate a beach umbrella witha less convex profile, and thiswas angled away from thewoman’s waist; the swimsuitwas changed to a differentcolor (antithesis rests onopposition within parallelism,and the change in color wasnecessary to break the latter)

Motion sicknessremedy ad

Trope Destabilization Visual metaphor depictsthe package as a seatbelt buckle

Iconic relation betweenpackage shape and therectangle of a typical seatbelt buckle;Indexical relation betweencars and motion sickness;Symbolic relation betweenseat belts and prudentpreparation

A buckle was added to the seatbelt, and the package wasmoved further back on theseat

Almond ad Trope Destabilization Visual pun created bythe “accidental”resemblance betweenthe arrangement ofitems on the rightplate and a smilingface

Iconic relation between platearrangement and “happyface” (yellow circle withdots and a curved line);Indexical relation betweensmiling faces andhappiness;Symbolic relationshipconnecting croissants andfine china to ideas ofsophistication and status

Almonds and croissants on theright-hand plate wererearranged so as not toresemble facial features

VISUAL RHETORIC IN ADVERTISING 41

situated knowledge structures that predate and, to a notabledegree, pattern the kinds of meanings that emerge from aviewer’s interaction with advertising. These structures in-clude the purposes of advertising; other (dis)similar adsseen before (style and content); other social phenomena thatare evoked in, or can be related to, the ad; and so on.

It is worth noting that this cultural approach to advertis-ing visuals is highly convergent with the work of leadingfigures in the semiotic tradition who maintain that there areno pure icons and who base their frameworks of signproduction and interpretation on a foundation of culturalcontext (e.g., Eco 1979). Moreover, from this perspectivethe text reader must be competent before a lone sign orstring of signs can stand for anything. Jakobson (1971)captures this requirement through his emphasis on theshared codes between message sender and receiver that area prerequisite for the successful production and understand-ing of signs. Similar connections between competency andcodes have been made in linguistic theory (Chomsky 1968)and literary theory (Culler 1975).

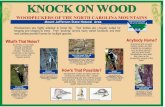

With this background on the theoretical and terminolog-ical underpinnings of our text-interpretive analyses, Table 1displays some of the basic semiotic and rhetorical relation-ships that characterize the four stimuli containing visualfigures constructed for the experiments (see Fig. 1 for ex-amples of the actual stimuli). We have placed these analysesin a table to facilitate review of the key elements of theinterpretations as we proceed through the remainder of thearticle. Some of the central cultural elements in these ads,which are more amenable to narrative rather than tabularpresentation, are discussed below.

The sociocultural knowledge required to appreciate themascara ad includes an understanding of the associationbetween fur and wealth, glamour, and sophistication, andalso of the flirtatious character of a backward, over-the-shoulder glance. Particularly knowledgeable readers mayassociate the style of hat with Arctic regions and infer anexotic quality for the brand. The sociocultural knowledgerequired to appreciate the yogurt ad includes an awarenessof the beach as a place where a woman’s attractiveness canbe demonstrated and an understanding of the role of anhourglass figure, together with its effective display in aswimsuit, in establishing that attractiveness.2 Readers mayalso connect the beach ball with ideas of fun and festivities,and draw the inference that only the slender can really enjoythemselves. For the motion sickness remedy, the readermust appreciate how the legal mandate to wear seat belts,together with decades of public service ads promoting seatbelt use, have invested the seat belt, and in particular the actof buckling it, with ideas of safety, security, and protection,and with the guarantee of same. More knowledgeable read-ers may infer a general theme as to the importance ofprudence, with obvious application to the idea of buying theremedy “just in case.” For the almond ad, the reader needsto be familiar with the yellow happy face symbol, with the

idea of toppings as a way to improve food, and with crois-sants and their associations as a special or elite food withinthe breakfast category. More generally, the reader has to becomfortable with the idea that objects and things can expe-rience human emotions and that food can be the source ofhappiness, as seen in countless ads for various packagedfood products over the years.

STUDY 1This study is an experiment designed to test the impact on

consumer elaboration of the four visual figures analyzed inthe previous section. We first describe the computer-aidedtechnique whereby the manipulations of visual figures wereexecuted. Then we describe the experimental procedure andreport the results of statistical tests.

Stimuli Construction

The four test ads were based on actual magazine ads—formascara, yogurt, a motion sickness remedy, and almonds—that were judged to contain instances of different visualfigures and to be relevant to a student subject pool. Aprofessional artist used a scanner and computer graphicssoftware, first to duplicate the original ad, then to abstractthe key elements that made up the visual figure, and finallyto alter these according to our specifications (Table 1). Next,a fictitious brand name was devised for each, along with amatter-of-fact headline that claimed a key attribute for eachbrand (based on the verbal text of the original ad). Desktoppublishing software and a color laser printer were used toprint the resulting test ad on 81⁄2 3 11 inch paper.

Each ad was produced in two versions, with the differ-ence between the versions constituting the manipulation.Specifically, for each ad a small change to the visual ele-ment sufficient to remove or break the rhetorical figure wasmade using graphics software. For example, the originalmotion sickness ad for Dramamine constituted a visualmetaphor in which the product package was depicted as thebuckle of a seat belt. By moving the product package awayfrom the belt, and incorporating a normal buckle, the met-aphor is broken, but all the other elements represented in thepicture, together with their associated semantic cues—carseat, seat belt, product package—are held constant acrossthe manipulation. Similar manipulations were performed toremove the visual rhyme from the mascara ad, the visualantithesis from the yogurt ad, and the visual pun from thealmond ad (see examples in Fig. 1 and discussion in Table1). Hence, the stimuli include two schemes (rhyme, antith-esis) and two tropes (metaphor, pun).3

Subjects and Procedure

A total of 72 undergraduates at a private university inCalifornia participated in the experiment. Each subject re-ceived a folder containing ads accompanied by an answerbooklet. The four test ads were administered in four coun-

2The authors by no means endorse these ideas; we only note theirpresence in the culture and their availability to readers seeking to interpretthis ad. 3Copies of the stimuli can be obtained by writing the first author.

JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH42

FIGURE 1

EXAMPLES OF THE VISUAL RHETORIC MANIPULATION

NOTE.—For each pair the illustration on the left shows the visual figure present (treatment), while the one on the right shows the corresponding control. The toppair of ads, for mascara, represent a scheme treatment; the bottom pair, for a motion sickness remedy, represent a trope treatment.

terbalanced orders. Figurative and nonfigurative treatmentsalternated within each order, so that each subject saw twoads with visual figures (these constituted the treatment con-dition for a given subject) and two without visual figures(the control condition). The specific ads that served astreatments and controls varied across orders. A warm-up adalways appeared first (two different ads, each appearing intwo of the orders), to accustom subjects to the kind ofstimuli and questions they would encounter.

Subjects were told that this was a study of advertising,that the ads they were going to see were in rough andunfinished form, and that this type of pretesting was com-mon in the industry. They were encouraged to imagine theywere encountering these ads in a magazine and to respondas naturally as possible. Each subject worked through theads at their own pace, answering questions pertaining to anindividual ad immediately after viewing it. These conditionsof forced exposure were adopted to encourage subjects toact as astute readers of ad texts. Put differently, a failure tofind the proposed effects under these favorable conditionswould call into question the theoretical basis of the research.About 20 minutes were required to complete the study.

Measures

Manipulation and Confound Checks.The perceivedfigurativeness of each ad served as a manipulation check,and this was measured by a seven-point semantic differen-tial item corresponding to that used by McQuarrie and Mick(1996), anchored by “artful, clever”/“plain, matter-of-fact.”A single yes or no item was included as a confound check.For each ad, this item restated the attribute conveyed in theheadline and asked whether this was what the ad was tryingto convey (e.g., “Pramnol prevents motion sickness”). Thisitem was the last one completed for each ad. The purpose ofthis confound check was to ensure that the inclusion orremoval of a visual figure did not unintentionally substitutea different focal brand attribute altogether, or convey thefocal attribute to a disproportionately larger or smaller num-ber of subjects.4 Failure to meet a test of key attributeequivalence would undermine inferences about the treat-ment contrast; that is, it would suggest that differences inelaboration might be due to differential effectiveness inconveying the central brand attribute and not to the manip-ulation of ad style per se.

Dependent Variables.Elaboration was measured by sixitems designed to tap both imagistic and discursive re-sponses. Imagistic responses were measured by three se-mantic differential items drawn from the vividness measuredeveloped by Unnava and Burnkrant (1991), anchored by“provokes”/“does not provoke imagery,” “vivid”/“dull,”and “interesting”/“boring.” Discursive responses were mea-sured by three items anchored by “I had many thoughts inresponse”/“I had few thoughts in response,” “the ad hasmultiple meanings”/“the ad has one meaning,” and “the ad

has rich, complex meaning(s)”/“the ad has simple mean-ing(s).” The six-item sum appears to be unidimensional(factor analysis revealed only one eigenvalue. 1) andexhibits a high degree of internal consistency (a 5 .87).

Results

For each of the four ads, the confound check showed thatthere was no significant difference in the extent to which thefocal brand attribute was conveyed by versions with andwithout visual figures (allx2 , 1.48). Moreover, within-subjects comparisons using the manipulation check showedthat the ads that received the visual figure treatment wereperceived as significantly more artful and clever than thecontrol ads (X treatment5 4.76,Xcontrol 5 3.55,t(71) 5 5.83,p , .001). Finally, ads with visual figures also evoked moreelaboration than the controls (Xtreatment 5 4.06, Xcontrol5 3.34,t(71)5 3.60,p , .001). An examination of the fourads individually showed that all the mean differences werein the predicted direction, indicating that the overall effectwas not dependent on one or two unusually effective ads.

Treatment3 Treatment Interaction Effect.In two ofthe orderings of stimuli the two ads with visual figures weretropes, while in the other two they were schemes. Hence, theinteraction term in an ANOVA with one within-subjectsfactor (visual figure present or absent) and one between-subjects factor (figure treatment applied to schemes ortropes) provides a test of whether the impact of the visualrhetoric treatment is greater in the case of tropes. Althoughin the case of the manipulation check that measured figu-ration the pattern of means was as predicted (Table 2), theinteraction did not achieve significance (F(1, 70) 5 1.24,NS). Nonetheless, the expected pattern of mean differenceswas found, accompanied by a significant interaction term,for the elaboration measure (F(1, 70) 5 24.7, p , .001).These latter results can be explained in terms of the morecompelling invitation to elaborate offered by tropes, whichare undercoded and incomplete in semiotic terms, such thatsubjects are drawn to further interpretation, both imagisticand discursive.

Discussion

This initial experiment established that visual figures inadvertising have the potential to alter the important con-sumer response of elaboration. The manipulation is argu-ably among the more subtle attempted for visual elements,certainly in comparison to such macroalterations as theremoval of the visual element altogether (Edell and Staelin1983) or the swapping out of depicted objects (Miniard et al.1991; Mitchell and Olson 1981) or even the addition ofcolor (Meyers-Levy and Peracchio 1996). The results testifyto the acute sensitivity of consumers to both the visualelement of advertising generally and to the presence ofrhetorical figures specifically. In fact, we were able todemonstrate the elaboration effect using four different adsfor a diverse set of low-cost consumer package goods. Itappears then from this experiment that visual rhetorical

4It should be noted that this confound check does not protect against thepossibility that inclusion of a visual figure might provide other brand-attribute linkages besides the primary one.

JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH44

figures can be an effective stylistic device with wide appli-cability. Overall, the impact shown here is consistent withthe frequent appearance ofverbal figures in print advertis-ing reported in the literature (Leigh 1994) and with priorwork suggesting the potential effectiveness of visual figures(Abed 1994; Forceville 1995; Phillips 1997).

Of course, increased elaboration does not necessarilyimply that consumers are persuaded by an ad. Research hasshown that elaboration may indicate distraction if what iselaborated has nothing to do with the message intended bythe advertiser. Thus, increased elaboration by itself mayactually have a negative effect on persuasion, if the distrac-tion is sufficiently strong. Hence, we undertook a secondexperiment that focused on whether visual rhetoric createsmore positive or negative reactions. Because theorizingconcerning rhetorical figures has emphasized their aestheticproperties, this second experiment focuses on Aad as adependent variable. If visual figures are processed as aes-thetic objects, then, ceteris paribus, they should create plea-sure for subjects, and this pleasure should be captured by astandard measure of Aad.

The counterargument to this line of reasoning would bethat visual figures are more difficult to comprehend. Withinthe Western tradition positive statements about the aestheticvalue of rhetoric are balanced by negative statements thatderide the needless complexity and intellectual vacuity ofrhetorical constructions (Sperber and Wilson 1990). Thisderogatory stance can also be found in contemporary dis-cussions of copy writing, which typically counsel againstcuteness, cleverness, and gimmicks in general (e.g., Burtonand Purvis 1996). If the benefits conveyed by visual figurescome at a significant cost in terms of irritation or confusion,then their net effect on persuasion may be nil.

Taken together, measures of Aad and comprehension dif-ficulty enable the second experiment to adjudicate among avariety of competing explanations for the initial finding thatvisual figures produced greater elaboration. For example,positive findings for Aad combined with a null result forcomprehension difficulty would support our basic assertionabout the communication gains potentially offered by visualfigures as a stylistic device. Visual figures would thenprovide advantages—pleasure, greater engagement with

meanings—without substantial costs in terms of diminishedcomprehension from challenges in processing the figures.Conversely, null findings for Aad in combination with asignificant increase in comprehension difficulty would im-ply that the increased elaboration in the first experimentcame about because subjects were puzzled by the visualfigures. This combination of findings would suggest thatvisual figures, although they do affect consumer processing,do not on balance contribute to persuasion. Next, positivefindings for both Aad and comprehension difficulty wouldintimate that visual figures may sometimes be effective, butonly in circumstances where the consumer is motivated, andhas the opportunity, to overcome the hurdles of processingthem (as commonly occurs in laboratory experiments).Lastly, null findings for both Aad and difficulty wouldcontest the findings of study 1 altogether, suggesting thatthey were artifactual.

Study 2 also provides an opportunity to investigate fac-tors that might moderate the impact of visual rhetoric on Aadand comprehension difficulty. The organizing theme for thisset of boundary factors is competency, which was acknowl-edged earlier with respect to the fundamental theory ofrhetoric and cultural analysis but not directly examined instudy 1. As noted earlier, the pleasure of the text that visualrhetoric is supposed to produce requires some minimumlevel of competency on the part of readers. In other words,text creator and text reader must share common codes tosome degree if the reader is to effectively interpret the text.Competency is also inversely related to difficulty, in thatsubjects with greater competency are likely to be moresuccessful in processing intricate material and hence morelikely to experience the pleasure of the visual figure. Weexplore three dimensions of competency in study 2.

The first dimension involves whether the consumer has apropensity or preference to engage in the processing ofvisual information per se (Childers, Houston, and Heckler1985). Propensity to process visual information is importantbecause the manipulation executed in these experiments canbe easily ignored or missed. Because the nonvisual portionsof the test ads are identical across treatments, a subject wholacks a propensity to process visual information may be less

TABLE 2

RESULTS FOR STUDY 1

Variable

All Scheme Trope

Control Treatment Control Treatment Control Treatment

Confound check (%)a 81.1 86.8 85.9 90.3 76.4 83.3Manipulation checkb 3.55 4.76 3.96 4.58 3.14 4.93

(1.41) (1.45) (1.48) (1.54) (1.21) (1.35)Elaboration 3.34 4.06 3.97 4.28 2.70 3.83

(1.15) (1.20) (.99) (1.26) (.94) (1.11)

NOTE.—n 5 72. SDs are given in parentheses.aThe confound check indicates the percent of subjects in a cell who agreed that the ads making up that cell conveyed a specific attribute.bThe manipulation check took the form of a variable called figuration, measured by the item “artful, clever”/“plain, matter-of-fact.” Higher values indicate ratings

toward the “artful, clever” end of the scale.

VISUAL RHETORIC IN ADVERTISING 45

sensitive to the experimental treatment, with respect tocomprehension difficulty and/or Aad.

A second dimension of competency rests on basic famil-iarity with the product category or benefit(s) being adver-tised. One of the test ads concerns a product used almostexclusively by women (mascara), while another concerns abenefit and appeal—lose weight to look your best—as wellas a product (low-fat yogurt) typically directed at femaleaudiences. Moreover, a third test ad addresses a condition(motion sickness) that is suffered by only a fraction of thepopulation, for whom the proper medicinal benefits arelikely to be salient and urgent. In all three cases, greaterproduct and benefit familiarity imply more developed anddifferentiated knowledge schemata relative to the issuesmentioned. In turn, that difference in knowledge may in-crease the probability that the subject will appreciate themeanings put in play by the visual figures and experiencethe pleasure of the text created thereby. Greater familiaritymay also reduce difficulties in comprehending the visualfigures, as more developed schemata increase the odds thatthe subject will understand why and how the visual portionof the ad has been arranged just so.

A third dimension of competency germane to visualfigures is cultural competency. The importance and role ofcultural knowledge in the processing of advertisements hasbeen developed extensively by Scott (1994a, 1994b). Ac-cording to her theorizing, cultural competency is necessaryto appreciate the visual figures used in this research becausemany of the potentiated meanings require expertise con-cerning contemporary American culture, including its so-phisticated advertising environment and English idiom, ascan be seen from Table 1 and the text-interpretive analysesformulated earlier. Confronted by a visual figure in anAmerican print ad, a person from a non-Western culture,especially one in which advertising is less advanced orconforms to different conventions, is less likely to enjoy,say, a product package used metaphorically as a seat buckleto emphasize safety, stability, and security as product ben-efits. However, and quite interestingly, a cultural compe-tency deficit may or may not be manifest as a perceiveddifficulty or opacity in comprehending the test ad; rather,the person who lacks cultural competency may simply passright over the cultural nuances on which the figure turns.Fewer meanings would then be unlocked, resulting in lesspleasure.

A final purpose of study 2 is to address two limitations ofthe initial experiment. As a within-subjects design, the firstexperiment is susceptible to demand artifacts insofar assubjects may have guessed its purpose or focus and therebygenerated findings concordant with our expectations. Weincluded a demand check in study 2 in order to address thisconcern. Second, the results in study 1 with respect to thescheme versus trope comparison, which is essential to Mc-Quarrie and Mick’s (1996) framework and to this project,were inconclusive. In study 2 a larger sample is combinedwith the close look at three potential moderating factors(competencies) in order to permit a more definitive conclu-sion about the scheme versus trope distinction and its sus-

tainability as an important contribution to theorizing aboutvisual figures.

STUDY 2

Sample and Procedure

Data were collected from undergraduate students at twosites, a large public university in the Midwest and the sameprivate university in California as in study 1. In each case,subjects were recruited from class sections known to con-tain international students. A total of 187 subjects partici-pated; after elimination of severely incomplete answerforms, responses from 181 subjects were available for anal-ysis. Instructions and stimuli were the same as for study 1.

Measures

Manipulation, Confound, and Demand Checks.Weagain used a seven-point semantic differential item an-chored by “artful, clever”/“plain, matter-of-fact” as a ma-nipulation check to assess the perceived figurativeness ofads. As in study 1, for purposes of a confound checksubjects were also presented with a restatement of theattribute claimed by the headline and asked to check yes orno as to whether the ad had conveyed that message. How-ever, when presented in isolation, as had been the case instudy 1, there is the possibility that yea-saying bias woulditself tend to eliminate differences between the treatmentand control versions, thus undermining the credibility ofthis confound check. Hence, in study 2 we devised a be-lievable but false claim for each ad, not congruent witheither picture or headline (e.g., “Pramnol is used by millionsof people every day”), to which subjects almost had to sayno, and placed it before the key attribute claim, in anattempt to mitigate yea-saying bias. Lastly, as a check ondemand artifacts, at the end of the study subjects were askedto explain what it was about.

Dependent Variables.Attitude-toward-the-ad was mea-sured by the sum of three semantic differential scales,anchored by “liked”/“disliked,” “unpleasant”/“pleasant,”and “enjoyed”/“did not enjoy” (a 5 .90). Subjects alsorated each ad’s difficulty of comprehension using threesemantic differential scales anchored by “easy to under-stand”/“difficult to understand,” “straightforward”/“confus-ing,” and “the meaning is certain”/“the meaning is ambig-uous” (a 5 .87).

Visual Style of Processing.Childers et al. (1985) devel-oped their style of processing (SOP) measure to distinguishindividuals who prefer to process information visually fromthose who prefer to process verbally. The SOP consists of22 items (e.g., “My thinking often consists of mental pic-tures or images”) rated on a four-point scale (“always true”/“always false”) and intended to be summed. Half the itemsassess preference for visual processing and half for verbalprocessing, which are assumed to lie at opposite ends of acontinuum. Unfortunately, in pilot testing we were unable toobtain opposing scores for the visual and verbal subscales;

JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH46

in fact, there was no linear relationship between them (n5 54, r 5 .04, NS). Hence, for purposes of examining theinteraction between visual style of processing and the ef-fectiveness of the visual rhetoric treatment, we used only thesum of the 11-item subscale that measured visual processing(a 5 .70), with the sample split at the median of thismeasure to create a between-subjects factor.

Additional Blocking Factors. We also split the sampleon some additional between-subjects factors to test the othermoderating variables corresponding to the theme of com-petency. These included sex of subject (56 percent werefemale), whether the subject had ever suffered motion sick-ness (43 percent stated “never”), and the subject’s originalculture (foreign or American). The latter was assessed byhaving subjects list all the languages they could speak andthe age at which they learned to speak each one. Non–nativeEnglish speakers were 32 percent of the sample, and most ofthese (51 of 58) grew up speaking an Asian language. Thecultural homes of these individuals thus represent economicenvironments (e.g., China, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Viet-nam) where advertising is neither as pervasive nor as highlydeveloped as in the United States and where the productsfeatured in the ads may themselves be uncommon.

Analyses

Each subject viewed one visual trope, one visual scheme,and two ads without visual figures. Which ad carried a tropeor scheme varied across orders. The 2 (mode of figuration)3 2 (visual figure present or absent) within-subjects inter-action serves as a test of whether visual tropes have a morepowerful impact than visual schemes. In addition, variousbetween-subjects factors as described above were used totest for interactions indicating a moderating role for com-petency.

Results

Manipulation, Confound, and Demand Checks.Themanipulation check showed that the ads receiving the visualfigure treatment were again judged to be significantly moreartful and clever than the controls (Xtreatment 5 4.33,Xcontrol 5 3.62, t(180) 5 5.08,p , .001 ). As before, theconfound check showed that there was no significant dif-ference in the extent to which treatment and control versionsof an ad communicated the key brand attribute (allx2s, 1).Inasmuch as the patently false claim that preceded the keybrand claim was checked no in about 95 percent of cases,this null result does not appear to be an artifact of yea-saying bias. Finally, when subjects were asked to explainwhat they thought the study was about, no one made anyreference to alterations in the pictorial portion of the ads, orto figures of speech, humor, metaphor, or any rhetoricalnotion, suggesting that no one guessed the hypotheses of thestudy.

Treatment Effects. Before assessing possible interac-tions,t-tests for paired observations were conducted on Aadand difficulty of comprehension. These showed that ads

receiving the visual figure treatment produced a signifi-cantly more positive attitude than the control ads (Xtreatment5 4.63,Xcontrol 5 4.10, t(180) 5 4.27,p , .001), withoutbeing any more difficult to understand (Xtreatment5 2.69,Xcontrol 5 2.73, t(180) 5 2.37, NS).

Block 3 Treatment Interactions. Each blocking factorwas examined in turn, first with respect to Aadand then withrespect to difficulty of comprehension. For Aad, visual styleof processing did not interact with the manipulation (F , 1),indicating that favorable responses to visual figures did notdepend on a preference or propensity for processing visualinformation. Next we considered the within-subjects com-parison between the mascara and the yogurt ad (the orderswere such that for each subject, when one ad received themanipulation, the other did not), with gender as a between-subjects variable. Again, no significant interaction wasfound (F , 1), indicating that subjects likely to differ intheir degree of product/benefit familiarity were nonethelessequally able to derive enjoyment from the visual rhetoric.This finding was replicated in a totally between-subjectsdesign that examined Aad for the motion sickness product.Using a 23 2 design that crossed the visual figure manip-ulation with the presence or absence of prior experience ofmotion sickness, we again found no significant interaction(F(1, 177)5 1.31, NS). Lastly, we examined the interactioninvolving foreign versus American subjects as an indicatorof cultural competency with respect to American advertis-ing. Here we found a significant interaction (F(1, 179)5 4.57,p , .05), such that the treatment effect is minimalamong foreign subjects (see Table 3).5 This suggests thatthe impact of visual figures is in part a function of adequatelevels of cultural competency.

We repeated these analyses using difficulty of compre-hension as the dependent variable. In no case was there asignificant interaction between any of the blocking factorsand the manipulation. In the case of foreign subjects therewas a main effect, such that relative to American subjectsthey found all the test ads—both treatments and con-trols—to be somewhat more difficult to comprehend(F(1,179)5 3.68,p , .06). This is confirmed by a reanal-ysis of the confound check, which showed that foreignsubjects were significantly less likely than American sub-jects to register the key brand attribute (87.5 percent vs. 93percent,x25 5.1, p , .05) but that this slight failure toregister the key attribute was constant across treatment andcontrol ads (x2 , 1). Taken together, the difficulty measureand the confound check show that foreign subjects makingtheir way in American culture did find all the test stimulisomewhat more refractory, as might be expected, but didnot find ads with or without visual figures to be any more orless difficult to comprehend.

Treatment3 Treatment Interactions. With the largersample and an all within-subjects design of study 2, we were

5After obtaining this result we reexamined the other two blocking factorsin a series of three-way interactions that included culture of origin. Both ofthe other two-way block3 treatment interactions, involving style ofprocessing and product/benefit familiarity, remained insignificant.

VISUAL RHETORIC IN ADVERTISING 47

able to obtain a significant interaction for the manipulationcheck that measured figuration (F(1,180)5 4.07, p , .05).That is, tropes were judged to be significantly more artful thanschemes (Table 3). Perhaps more interesting, when culturalcompetency is added as a blocking factor, the three-way inter-action is also significant (F(1, 179)5 5.83,p , .05). As canbe seen from Table 3, foreign subjects appreciate the artfulnessof the overcoded visual schemes to about the same degree asAmerican subjects, but foreign subjects do not find the under-coded tropes to be particularly artful or clever. Examining Aadas the dependent variable, the trope by scheme interactionexamined in isolation was only marginally significant (p5 .08). However, when cultural competency is added as ablocking factor, the three-way interaction is significant (F(1,179) 5 5.52, p 5 .05), confirming that for the Americanstudents, who are familiar with the culture of American adver-tising, visual tropes have an even more positive impact on Aad,relative to their controls, than visual schemes, relative to theircontrols (Table 3). By contrast, as can be seen from Figure 2,foreign subjects are particularly unappreciative of visualtropes—in their case the manipulation had no effect on Aad. Noother blocking factor interacted significantly with the tropeversus scheme distinction when applied to Aad. Moreover,there was no trope by scheme interaction in the case of diffi-culty of comprehension, nor did any blocking factor enter intoan interaction involving this dependent variable.

Discussion

Visual rhetoric appears to be a subtle but powerful devicecapable of producing a more positive attitude toward the ad

associated with a surplus of favorable over unfavorableelaboration. Moreover, the positive impact of visual rhetoricdoes not come at any obvious cost—ad versions with visualrhetoric are no less effective at communicating a key brandattribute, and are no more difficult to understand. The treat-ment effect for visual rhetoric is also well behaved, inas-much as it conforms to the model presented in McQuarrieand Mick (1996), with the visual tropes in this study able toproduce a more positive attitude than visual schemes, pro-vided cultural competency is adequate.

Analysis of the three competency factors provides someinsight into boundary conditions for the impact of visualrhetoric in advertising. Somewhat to our surprise, the mea-sure of the propensity to process visual information had noeffect. Several explanations are possible. It might be that thevisual figures used in this experiment were so salient, and/orthe stimuli were so simple, that no special propensity toprocess visual information was necessary to apprehend andrespond to the visual figures. Results might be different ifmuch more complex visual stimuli were used. Alternatively,the forced exposure conditions may have washed out anydifference caused by the propensity to process visual infor-mation. In any case, this experiment does not support theproposition that visual rhetoric can only succeed in the caseof a “visualizer” segment of consumers (see Rossiter andPercy 1980).

Our investigation of the role of product/benefit familiar-ity—via gender of subject and prior experience of motionsickness—similarly showed no impact for this factor. Itappears that one does not have to be a product user or

TABLE 3

RESULTS FOR STUDY 2

Variable n

Confound checka

Manipulation checkb

Aad DifficultyControl

(%)Treatment

(%) Control Treatment Control Treatment Control Treatment

All subjects 181 91.2 91.4 3.62 4.33 4.10 4.63 2.73 2.69(1.32) (1.41) (1.16) (1.14) (1.21) (1.26)

Trope 90.6 90.6 3.35 4.29 3.83 4.56 2.85 2.75(1.84) (1.93) (1.48) (1.52) (1.65) (1.60)

Scheme 91.7 92.3 3.88 4.38 4.37 4.71 2.61 2.63(1.69) (1.72) (1.67) (1.60) (1.60) (1.48)

American subjects 123 93.5 92.7 3.59 4.40 3.98 4.69 2.67 2.56(1.34) (1.44) (1.17) (1.11) (1.21) (1.19)

Trope 93.5 91.9 3.30 4.50 3.64 4.71 2.86 2.60(1.83) (1.90) (1.45) (1.44) (1.69) (1.51)

Scheme 93.5 93.5 3.87 4.29 4.32 4.66 2.48 2.51(1.70) (1.69) (1.68) (1.64) (1.51) (1.41)

Foreign subjects 58 86.2 88.8 3.68 4.20 4.37 4.52 2.86 2.97(1.27) (1.35) (1.11) (1.19) (1.21) (1.36)

Trope 84.5 87.9 3.47 3.83 4.26 4.24 2.81 3.05(1.87) (1.92) (1.48) (1.64) (1.59) (1.74)

Scheme 87.9 89.6 3.90 4.57 4.48 4.80 2.90 2.90(1.69) (1.79) (1.67) (1.51) (1.77) (1.58)

NOTE.—SDs are given in parentheses.aThe confound check indicates the percent of subjects in a cell who agreed that the ads making up that cell conveyed a specific attribute.bThe manipulation check took the form of a variable called figuration, measured by the item “artful, clever”/“plain, matter-of-fact.” Higher values indicate ratings

toward the “artful, clever” end of the scale.

JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH48

prospective purchaser in order to understand the visualfigures used to advertise the products in question in thisexperiment. Possibly the gendered products were not gen-dered enough—that is, the schemata required to process theads were available to both genders. Products used in privateby one gender might have yielded a stronger effect. Ofcourse, other approaches to familiarity than those used herecan be envisioned. A study that distinguished, say, long-time users from novices within a technical product categoryand applied a visual figure that was more intimately en-twined with the specialized meanings or professional argotassociated with that product category might show a signif-icant moderator effect for product familiarity.

By contrast, cultural competency emerges as an importantmoderating factor, especially in the case of visual tropes.Despite being implemented in the form of pictures rather thanwords, there is no evidence that particular instances of visualtropes (here, metaphor and pun) are equally effective for con-sumers from different cultures. The meanings provoked byvisual tropes are not on the page or in the picture but ratherrequire an active construal by the reader, a construal thatrequires a body of cultural knowledge before it can occur.These results are generally supportive of Scott’s (1994a,1994b) theory, though the data regarding visual schemes areless so, as will be discussed subsequently.

Two issues remain to be clarified. The first of these

revisits the text-interpretive analyses presented earlier. Theexperiments themselves provide no direct evidence that thesubjects elaborated the ads in the ways suggested. A moresensitive elicitation technique is required to determinewhether the text interpretations are but figments of thesemiotician’s imagination or instead correspond to consum-ers’ actual reactions. If consumers do elaborate on the ads inways roughly consistent with the text-interpretive analysis,then a more secure attribution of the treatment effects to thevisual figures, and to the meanings set in play thereby, canbe forged. To this end, we undertook phenomenologicalinterviews with a small number of informants, as describedin study 3 below. Second, these interviews also allow us tofollow up on the intriguing findings concerning culturalcompetency. It appears that subjects with less knowledge ofAmerican culture simply did not apprehend the meaningsset into play by the visual tropes in the study. Here again, amore thorough and sensitive exploration of the meaningsactually drawn from the ads would have value in replicatingand clarifying the nature of the impact of cultural compe-tency as a moderating factor.

STUDY 3

A dozen undergraduate students from a private universityin California were recruited to participate in interviews

FIGURE 2

ATTITUDE TOWARD THE AD: INTERACTION BETWEEN CULTURAL COMPETENCY AND SCHEME VERSUS TROPE DISTINCTION

NOTE.—The absolute values of the means shown are immaterial, inasmuch as the trope and scheme manipulations were executed in different ads for differentproduct categories. The analysis focuses on the relative size of the treatment versus control differences across condictions and populations.

VISUAL RHETORIC IN ADVERTISING 49

conducted by a graduate assistant. The interviewer gaveeach subject a portfolio containing five ad stimuli. The firstof these was a practice ad that did not contain a visualfigure, while the remainder were copies of the four adstimuli that had contained visual figures used in the twoprevious experiments. For each ad subjects were asked whatmeanings that ad suggested to them and what it said to them.A nondirective interviewing style was used throughout. Nomeanings were suggested to subjects, and they were assuredthat there were no right or wrong answers and that we wereinterested in whatever occurred to them as they looked overthe ads. After all the meanings for an ad were elicited, theinterviewer then queried the informant about which aspectsof the ad had given rise to the meanings mentioned.

Four of these informants were American females, fourwere American males, and four were foreign females nativeto an Asian country. Comparison of the first two sets ofinterviews against the third is useful for exploring the effectof cultural competency found in study 2, while comparisonof the first and third sets against the second assists inexploring the null effect for product/benefit familiarityfound in study 2. Overall, analysis of these interviews isintended to provide a reader-response perspective to com-plement the text-interpretive and experimental analyses re-ported earlier. We expected the responses of these infor-mants, who were able to peruse the ads at leisure and speakfreely and at length, to contribute to tracing the process—opening the black box—whereby visual figures achievetheir impact.

The four interviews with American females illuminatehow culturally competent informants readily notice andappreciate the visual figures in the ads. For instance, en-countering the visual rhyme in the Mascara ads, two of theseinformants remarked:

The fur creates an effect like lashes. . . . She’s very seduc-tive, mysterious. (Informant no. 1)

The eyelashes go very well with the mink coat. . . . Theway that the mink looks, looks like the eyelashes. (Informantno. 2)

Similarly, these informants understood both the contrastand the parallelism that make up the visual antithesis in theyogurt ad. For example:

Odd position of shapes, how she’s so thin and how the ballis so fat. . . . The ball is curved to the right so my eyeautomatically veers to the right, drifts over, so I see thewoman and her curves are kind of sexy. (Informant no. 1)

The colors in the swimsuit and the colors in the ball arerelating the two shapes. (Informant no. 3)

These informants readily drew expected inferences fromthe visual pun in the almond ad as well.

They’ve formed this happy face on the second plate, kindof conveying the message that it’s somehow better, makesyou happier. (Informant no. 4)

That’s really cute. . . . This one is obviously a smiley face,the happy croissant, saying these almonds are going to makeyour breakfast a lot different. (Informant no. 3)

Lastly, the American female informants grasped and ap-

preciated the visual metaphor in the ad for the motionsickness remedy.

Eye catching . . . kind of creative because it is takingsomething that is familiar and relates to the product and kindof combines them both at the same time. (Informant no. 3)

I get a meaning of safety, I think because they’re using asafety belt with the product. (Informant no. 4)

Turning now to the American male informants and fo-cusing on the two gendered products, mascara and low-fatyogurt, the interviews illuminate how these males, presum-ably less familiar with the mascara product category andwith weight-loss products and appeals generally, nonethe-less are able to generate some of the same meanings as theAmerican female respondents with respect to the visualrhyme and visual antithesis in the mascara and yogurt ads,respectively.

For richer lashes, I equate the fur obviously, all the verydense texture, rich, full, I associate that with her eyelashes.(Informant no. 5)

Has that mysterious look. . . . The fur on the shawl and thehat really bring out the eye lashes. . . . Use our product andyou will be more pretty. (Informant no. 6)

I like how they have a slender body on one side and a bigfat round ball on the other. . . . The ad is saying eat Sophie’syogurt and you won’t look like a beach ball. (Informant no. 7)

Hence, American informants, both female and male,readily played the role of active and capable readers of thesead texts.

With the foreign female informants, our primary concernis to see whether they engaged with the visual schemeswhile failing to appreciate the visual tropes. We found, assuggested by study 2, that these foreign students weregenerally able to appreciate the visual schemes. For in-stance, one informant noted, in the case of the mascara ad,that “the reason why they use fur is because they want tomake parallel between the length of the lashes and the furitself ” (Informant no. 9, Indonesian), while another noted,in the case of the yogurt ad, “[It is] comparing a beach ball,a heavy person, and the person eating the yogurt is the thinone” (Informant no. 10, Vietnamese). The visual tropes, bycontrast, caused problems, leading to aberrant readings,misinterpretations, and/or a simple failure to enjoy the fig-ure, as shown by these quotes:

That [croissant] looks like a foot, [while the other] isobviously a smiley face. . . . Is it because they have thealmond on it so it becomes a happy face, and if you don’thave the almonds, then you’re not happy and you become astinky foot? (Informant no. 11, Taiwanese, with respect to thevisual pun in the almond ad)

They use the box as a buckle for the belt to strap you downfor people that get sick easily. I guess they shouldn’t show aseat belt even though they are unbuckling it. . . . They have toget strapped down to relieve their anxiety. They shouldn’tshow a seat belt. Even though it shows that they are unbuck-ling it, still shows that you’re strapped down. It doesn’t saymuch just by the picture. (Informant no. 10, Vietnamese,regarding the visual metaphor in the motion sickness ad)

It just doesn’t make sense at all. . . . I’ve never seensomeone in their private car get motion sickness. Americans

JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH50

are so used to driving. . . . Driving shouldn’t be a problem formost Americans. (Informant no. 9, Indonesian, regarding thevisual metaphor in the motion sickness ad)

From a semiotic viewpoint, these visual tropes functionas closed texts for these foreign readers (Eco 1979). Lackingthe necessary cultural background, the quotes show theseforeign informants struggling to resolve and appreciate thetext of these visual tropes. Thus, for example, the fact thatthe box containing the motion sickness remedy has beensubstituted for a seat belt buckle is basically apparent to theforeign informants; they know of course that a seat belt is asafety device; but the polysemic interaction of these twoideas never fully develops.

In sum, these interviews provide reader-response analy-ses to supplement the findings of the two experiments. Theinterviews show the informants variously noting and re-sponding to visual figures. They also show the Americaninformants elaborating several of the meanings of thesevisual figures along lines suggested by the earlier text-interpretive analysis. In combination, the experiments andreader-response analyses support the conclusion that visualfigures have a positive impact on consumer response, that itis the figures that act as the causal agent in producing thisimpact and that the positive impact is achieved by steeringcompetent consumers to read the text of the ads in particularways.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Only in recent years have consumer researchers begun totreat visual imagery in advertising as something other thana peripheral cue or a simple means of affect transfer. Todaythe visual element is understood to be an essential, intricate,meaningful, and culturally embedded characteristic of con-temporary marketing communication. However, detailedtheoretical specifications for ad imagery have yet to be fullyconstructed. In pursuit of this goal, the rhetorical figureemerges from this project as a general principle of textstructure that can be embodied in visual texts as well asverbal texts (McQuarrie and Mick 1996). In particular, weshowed that the artful deviation characteristic of figures, andalso the over- and undercoding that produces schemes andtropes, can be constructed out of pictorial elements in ad-vertising.

Our text-interpretive analysis of four magazine ads sug-gested that their pictorial elements comprised a variety ofrhetorical forms (rhyme, antithesis, metaphor, and pun) anddifferent types of signs (iconic, indexical, and symbolic) soas to evoke a diverse set of meanings about the brand and/oruser (e.g., sophistication, beauty, safety, fun). Two experi-mental analyses showed that these four ads, as compared tothe same ads with the visual figures broken or removed,stimulated more elaboration and a more positive attitudetoward the ad. Moreover, the effect of visual rhetoric wasrobust over different samples, across different ad execu-tions, and over multiple product categories. Visual figures,like the more familiar verbal figures (Leigh 1994), wouldappear to deserve a place among the executional devices

available to advertisers that have a consistent and reliableimpact on consumer response. This study provides addi-tional empirical support for the theoretical taxonomy devel-oped by McQuarrie and Mick (1996) and underscores itsgenerality, inasmuch as we found the distinctions they pro-posed for ad language to also hold true when embodied invisual form.

The main boundary condition we uncovered is that theconsumer must be sufficiently acculturated to the rhetoricaland semiotic systems within which the advertising text issituated; that is, s/he must be a culturally competent pro-cessor of the advertising message. However, although thiswas notably true for visual tropes, it did not conditionresponses to visual schemes. This finding both corroboratesand refines Scott’s (1994a) provocative theory. She arguedthat ad visuals should not be conceived as photocopies of apancultural reality; rather, they are often highly stylizedrepresentations that compel consumers to engage ads asmeaningful texts that require an active reading in accor-dance with an existing stock of sociocultural insights. Thisis precisely what we found with respect to the visual tropesthat require intricate semantic knowledge structures con-cerning the objects, activities, and products artfully depictedin the ads (e.g., car seat, safety belt and buckle, and motionsickness medicine; croissants, almonds, and the smiling“have-a-nice-day” face). In contrast, all subjects and infor-mants—foreign nationals as well as Americans—seemed toappreciate the schematic visuals that are constructed bysimilarities and/or differences in such surface features asshapes, sizes, and colors (e.g., black fur coat, black fur hat,and thick black eye lashes). The robustness of the effect forschemes may stem from a pattern-recognition ability basicto human visual perception. Alternatively, the cultural per-spective can be reasserted if it is argued that the experimen-tal subjects were all members of literate cultures, who knowhow to interpret duplicate or mirror-image elements on apage. Had the experiments included members of primitivepreliterate cultures, then perhaps the schemes as well as thetropes would have been shown to be dependent on culturalknowledge, of a very general sort in the case of schemes andof a much more specific and localized sort in the case oftropes. In either case, our data suggest that Scott’s (1994a,1994b) theory about the role of cultural competency inprocessing advertising rhetoric appears correct with respectto tropic rhetorical operations that are strongly dependent onsociocultural semantic knowledge but may be less germaneto schematic rhetorical operations determined by structuralregularities.