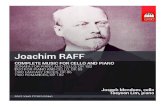

Varese: Orchestral Works, vol. 2

Transcript of Varese: Orchestral Works, vol. 2

VARESE Orchestral Works • 2

r

Ameriques • Ecuatorial • Ionisation Watts • Grochowska • Bloch

Men’s Voices of Camerata Silesia

Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra Christopher Lyndon-Gee

NAXOS

VA

RE

SE

: Orch

estral Work

s

The works on this recording span Varese’s entire career, containing his sole surviving early composition, Un grand Sommeil noir, and his last, unfinished work, Nocturnal, brilliantly and seamlessly completed by the composer’s disciple and assistant during the last seventeen years of his life, the composer Chou Wen-Chung. Chiefly, though, the recording features the original version of Ameriques, for a massive orchestra of 155 players, recorded immediately following a rare public performance at the Warsaw Philharmonic (only its second since the 1920s) as part of the 2005 Warsaw Autumn Festival.

Edgard

VARESE (1883-1965)

Orchestral Works • 2 3] Ameriques (original version 1921) 23:55

® Ecuatorial (1932-34) 3’4 10:27

® Nocturnal (1961) 4 9:24

SI Dance for Burgess (1949) 1:44

(§ Timing Up (1947) 4:50

® Hyperprism (1922-23) 3:48

® Un grand Sommeil noir (1906) 5 2:59

[8] Density 21.5 (1936)2 4:43

[9] Ionisation (1929-31) 5:24

Elizabeth Watts, Soprano 1 • Maria Grochowska, Flute 2 Thomas Bloch, Ondes Martenot3

Men’s Voices of Camerata Silesia (Anna Szostak: Artistic Director) 4

Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra16 9 Christopher Lyndon-Gee, Piano5 and Conductor

A detailed track list can be found on page 2 of the booklet

Available sung texts and translations are included, and may also be accessed at www.naxos.com/libretti/557882.htm

Recorded at Grzegorz Fitelberg Hall, Katowice, Poland, on 23rd and 24th September, 2005 (track 1), 4th November, 2005 (tracks 4-6), 5th November, 2005 (tracks 7-9), 6th November, 2005 (track 3),

7th November, 2005 (Track 2) • Producer: Beata Jankowska-Burzynska • Engineer: Wojciech Marzec

Cover photograph by Juan Hitters (www.juanhitters.com)

Playing Time

67:14

§ NAXOS & o ■JitiiJM Jiii.il,Jii.

CO

8.557882 ■1 DDD £ E x

Also available:

W -r V v V NAXOS ism uiitiiitt mii.ttiu.

[ppdI

Edgard 8554820

VARESE Arcana • Integrates • Deserts

Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra Christopher Lyndon-Gee

8.554820

8.557882 20

Also available

21st Century Classics m WEBERN Passacaglia • Symphony • Five Pieces

Yves PR1N

Dioscurts • Ephemfcres • Le souffle d’lris Pierre-Yve* Artaud • Philijipr Graffiti • Pascal Port

Orchertre Plillliannonitiue do Radio Franc*

gj SCHOENBERG Pierrot Lnnaire

Hir/geoikhw: • Four Orchestral Souks • Chamber S> mphonv No,

WEBERN Symphony

Six Pieces • Concerto for 9 Instruments

Twentieth Century Classics Ensemble I'hilharmiHiia Orchestra

Robert Craft

8.554841

Edgard

VARESE (1883-1965)

3] Ameriques (original version 1921), for very large orchestra and offstage ‘banda’ 23:55 (Performing edition by Chou Wen-Chung, 1998, with further small corrections in 2005)

[2] Ecuatorial (1932-34), for bass voices, two Ondes Martenot and ensemble 10:27 (On a sacred text from the Popul Vuh of the Mayan Quiche)

\3\ Nocturnal (1961), for soprano solo, bass voices and chamber orchestra 9:24 based loosely upon words and phrases from Anai's Nin’s The House of Incest (Edited and completed by Chou Wen-Chung, 1961)

[4] Dance for Burgess (1949), for chamber orchestra and percussion 1*44 (Edited by Chou Wen-Chung, 1998)

® Tuning Up (1947), for orchestra 4:50 (Completed from sketches by Chou Wen-Chung, 1998)

® Hyperprism (1922-23), for nine wind instruments and nine percussion 3:48

[7] Un grand Sommeil noir (1906), for soprano and piano 2:59 (On a poem by Paul Verlaine)

S3 Density 21.5 (1936), for solo flute 4:43

\9\ Ionisation (1929-31), for thirteen percussion, with piano 5:24

Publishers: Ricordi, Milan (tracks 1-6, 9) • Editions Salabert, Paris (track 7) American Music Center, New York (track 8)

With special thanks to Mme. Irena Siodmok, Artistic Director for NOSPR; Mme. Joanna Vnuk-Nazarowa, General Manager, NOSPR;

to Mr Tadeusz Wielecki, for Warszawska Jesien / Warsaw Autumn Festival; and to Professor Chou Wen-Chung (New York).

8.557882 2

Edgard Varese (Paris, 22nd December, 1883 - New York, 6th November, 1965)

Orchestral Works • 2

Edgard Varese is a restless figure, who still, 42 years after his death, disquiets, challenges, excites and mystifies us. We have neither yet absorbed nor fully understood, and are certainly still far from implementing his visionary and confronting rethinking of the art of music.

Varese must have been brilliant and fascinating as a young man, for in his early twenties he attracted the admiration of Debussy, Richard Strauss, Busoni, Guillaume Apollinaire, Pablo Picasso, Roussel, Widor, Hugo von Hofmannstahl (with whom he planned an opera, CEdipus und die Sphinx), Romain Rolland and many more of the foremost musical and artistic figures of his day. He made enemies, too, storming out of d’Indy’s composition class, and daring as something like a twenty-year-old to say to Saint-Saens: “I have no desire to become an old powdered wig like you.” Varese’s disastrous failed relationship with his violent father, who maltreated Varese’s mother and tried to derail any idea of his son’s musical career, is doubtless at the root of this anger that he frequently displayed to such early authority figures.

However touchy and devil-may-care, his brilliance shone for all to see; indeed, Romain Rolland recognized Varese as no less than an archetype for his rebel “artist- hero” Jean-Christophe, for, in the midst of his ten- volume magnum opus Rolland wrote to his friend Sofia Bertholini,

“I have not yet told you the fact that is most amusing in my acquaintance with this Varese: he is writing a [symphonic poem called] Gargantua. And, at this very moment, Jean- Christophe is writing one! To say, then, that my book is a ‘novel’! My book is not a novel. Jean- Christophe actually exists.”

Rolland’s description of his young hero in the first volume of his work is uncannily prophetic of Varese:

“He would rather die than live by illusion. Was not Art also an illusion? No. It must not be. Truth! Truth! Eyes wide open, let him draw in through every pore the all-puissant breath of life, see things as they are, squarely face his misfortunes, — and laugh.”

Following the young composer’s move to Berlin in late 1907, Richard Strauss, Karl Muck, Hugo von Hofmannstahl and Ferruccio Busoni all became firm supporters and advocates. Strauss went to considerable lengths to arrange the first performance in Berlin of the symphonic poem Bourgogne, on 15th December 1910, lending his authority and prestige to Varese’s music when the composer was not quite 27 years old. This score remained in Varese’s possession when he traveled back to Paris, and thus survived the Berlin warehouse fire that took the majority of his other early music, only to be tragically destroyed at the composer’s own hand during a depressive episode as late as 1962. His other early works — the symphonic poems Rhapsodie romane (honouring the Romanesque architecture that so inspired him while he was growing up in rural Burgundy), Prelude a la fin d’un jour, Gargantua and Me hr Licht were almost certainly never seen again after the 1913 fire.

Busoni’s visionary book, Sketch of a New /Esthetic of Music had played a large role in attracting Varese to Berlin, and the rapport between him and the great teutonic-Italian pianist composer was warm on both sides. Indeed, Busoni became his greatest enthusiast of all in Berlin, dedicating the score of his Berceuse Elegiaque in 1910, “All’ illustre Futuro, I’amico Varese, affezionatamente.”

Despite this extraordinary early recognition and success, Varese was both restless and impatient. He founded and conducted choirs in both Paris and Berlin, and, by all accounts had great success conducting Debussy’s Le Martye de Saint-Sebastien with the Czech

3 8.557882

Philharmonic Orchestra in Prague in January 1914. But no orchestra was offered him, and he felt that the First World War had closed off any likelihood of immediate openings. In any case, his inner ear had moved far beyond the possibilities of the orchestra with which he had grown up; we know that, as early as 1906, he was investigating the use of the siren as an orchestral instrument, and his flamboyant use of percussion had already made its presence felt in the early, lost scores. In 1913 he sought out Rene Bertrand, inventor of the dynaphone, and as early as the First World War he wrote:

“I dream of instruments obedient to my thought and which with their contribution to a whole new world of unsuspected sounds, will lend themselves to the exigencies of my inner rhythm.”

The Unknown, new horizons, a new aesthetic, new forms, a new sound-world, freedom from history were what fascinated him. Small wonder, then, that he saw his future in the New World — “symbolic of discoveries: new worlds on this planet, in outer space, or in the minds of men” — so he threw caution to the winds, crossed the Atlantic in wartime and disembarked at New York Harbour on 29th December, 1915.

His life in America was never easy; sometimes, one wonders why he repeatedly returned from the numerous trips he continued to make back to Europe, especially to Paris. During his longest sojourn in Paris, between 1928 and 1933, he briefly explored with Antonin Artaud a possible collaboration that might if pursued have become an opera called LAstronome (The Astronomer). Though never completed, sketches do exist of a segment called Sirius, which has brought forth creative responses of such disparate nature as Stockhausen’s Licht and, at a puzzling extreme, the unmentionable “rock opera” of 2006 by New York rock musician John Zorn that loudly but irrelevantly claims descent from Varese. His early days in New York were marked, however, by successes similar to those he had enjoyed in Europe. Barely a year

after arriving, he conducted a performance of Berlioz’s Requiem at which the sponsors included members of the Guggenheim, Pulitzer, Vanderbilt, Whitney and Morgenthau families, as well as many prominent names from the music establishment. Early in 1919 the New Symphony Orchestra was founded especially for Varese. But it was not long before his relentless programming of new music led to the alienation of much of his audience, and his concerts were soon taken over by Artur Bodanzky with watered-down programmes. Other ventures followed — the International Composers’ Guild in 1921, co-founded with Carlos Salzedo; the Pan-American Association of Composers in 1927; the Schola Cantorum of Santa Fe in 1937; the New Chorus in New York in 1941; and other initiatives. He served as a focal point and inspiration for two generations of young American composers, but his uncompromising nature and fearless programming left the broad public far behind. Little in the musical milieu has changed today.

Throughout his American years, he sought for “new mediums which can lend themselves to every expression of thought and can keep up with thought.” Efforts to develop new technical working tools with Leon Theremin, with Bell Laboratories, with various universities and others all led to frustration; it was 1953 before he received the anonymous gift of an Ampex tape recorder that led him to be able to start work on realizing the taped sections of Deserts, later completed in Paris thanks to an invitation from Pierre Schaeffer, with his vastly superior studio resources.

But Varese did not quite survive into the computer era. Perhaps Pierre Boulez in Repons, perhaps Karlheinz Stockhausen in Octophonie were the true heirs who were able to create sound worlds, worlds in real sound embodying something of what he may have imagined; perhaps it is they who have been — whether intentionally or unwittingly hardly matters — the ‘executors’ of his artistic will.

Yet we can, of course, never second-guess what this imagination without boundaries might have made of the possibilities of the sound-generating means of our own

8.557882 4

day. It is a tantalizing thought, and a sad one, highlighted if we merely contrast the overflowing richness of the ‘new worlds’ of Ameriques with the desolate landscapes of Deserts, written late in his life, by which Varese meant “not only physical deserts of sand, sea, mountains and snow, outer space, deserted city streets ... but also this distant inner space ... where man is alone in a world of mystery and essential solitude”.

Pierre Boulez, writing shortly after Varese’s death, put it best: “Your legend is embedded in our age; from now on, we can rub out that circle of chalk and water, those magic or ambiguous words: ‘experimental’, ‘precursor’, ‘pioneer.’ You have had enough, I think, of being promised the promised land in perpetuity. Enough of that restricted honour which has so often been offered you as an embarrassing and embarrassed gift ... Farewell, Varese, farewell! Your time is finished and now it begins.”

AMERIQUES, for very large orchestra and offstage ‘banda’ (Paris? 1915 - New York 1921)

In a single continuous movement, divided into primary sections:

Moderato, poco lento / alternating with Piu vivo - Appena piu animato, ma pesantissimo - Vivo, quasi cadenza - Presto - Poco lento - Moderato - Lent - Vif - Presto - Mosso - Presto - Extremement souple - Plotzlich, sehr ruhig, Langsam - Moderement anime - Vif (tres nerveux) - Mosso - Anime - Plus retenu - Pesantissimo e rude - Poco piu Lento, lontanissimo - Moderement Lent - Bewegt - Presto - Piu tranquillo - Andante - Lento - Rapidissimo (scuro) - Presto - Lento e stentato - Piu calmo - Grandioso - Presto - Pesantissimo.

Though most sources indicate that Ameriques was composed between 1918 and 1921, the work was almost certainly begun before Edgard Varese left Europe for

America in December 1915; Louise Norton, whom the composer first met shortly after his arrival in New York — their marriage would be delayed until 1922 — recalled his having with him a considerable quantity of sketches of material for a large-scale orchestral work. If such a work can be deduced to have been Ameriques, it was at that time either untitled or being accumulated under a different (and unknown) working title. As the massive work developed, it came to encapsulate all the composer’s idealism about rebirth and renewal in the new world of the Americas, such as had been extolled by Jose Marti in Nuestra America, and by so many others. What Varese in fact found, particularly in the “downtown” milieu he had chosen as his living environment, was a teeming, chaotic world of ships arriving and departing, commerce, crowded streets, dog- eat-dog competitiveness that (as today) clashed head-on with the mirage-like “opportunity” of the honeypot great city. And this music teems! - with endless invention and almost no literal repetition or conventional “development”, reflected in the tempo listings above. The form of the work follows its content, nothing is squeezed into any kind of pre-existing vessel. All this clamour is reflected especially in the percussion section requiring fourteen or fifteen players, in the sounds of ships’ bells, fire-engine bells, sirens, the composer’s favourite “lion’s roar” (a single-headed drum whose skin, pierced by a rough string, is made to vibrate by dragging a rosin-treated leather pouch up the tightly stretched string), crow-calls, steamboat whistles and other vividly imaginative percussion.

In fact, Varese’s interest in the siren and other “exotic” orchestral percussion instruments goes back at least to 1906. Even then, he was seeking ways to realize an inner musical vision with its roots in childhood memories of train whistles, by employing sound- production means that had greater constant sustaining power than existing orchestral instruments, and that could moreover play across a continuous spectrum of pitch, not limited by any tuning system. Nothing more convincingly anticipates the much later era of electronic music than Varese’s astoundingly imaginative

5 8.557882

employment of the percussion, and his fabulously flexible instrumentation in general. Ameriques, in the Beethovenian sense, is a complete, unrestrained “representation of a state of the soul in music.”

The music composed for the offstage ‘banda’ is the primary repository of nostalgia for the European musical world left behind. Did Varese ever hear Mahler’s Sixth Symphony? Whether he did or not (and the two men did meet in 1909), the phrases for trombones in the earliest of the offstage interpolations powerfully recall that work. We do know that he was present at the premiere of Le Sacre du Printemps on 29 May, 1913, and there are numerous sideways allusions to Stravinsky’s sound-world; even to the contrary motion concatenations of Skryabinesque complex harmonic masses in Zvezdoliki, a work Varese could not possibly have heard, since, though composed in 1911- 12 and published by Jurgenson in 1913, its performance was delayed until 19th April, 1939 in Brussels. Thus, we are encountering not only references to fully and half- remembered musics, but also to ideas that partake of the Zeitgeist of music yet unknown or not yet written.

This extraordinary work seems to span worlds, both historically and geographically; it is an apotheosis of the state of music in 1920; a compendium, no doubt, of everything Varese had not only composed but merely thought up to that date; an encyclopaedia, too, of all his musical experiences in Paris, Berlin and elsewhere. Could it not be claimed, indeed, that Ameriques sums up its age even more comprehensively than Le Sacre ?

This original version of Ameriques overflows with fecund invention and astonishing mastery of a monster orchestra, totaling a possible 155 musicians. Stokowski, perhaps wisely, recommended that Varese reduce the orchestral forces to something a little more reasonable, that would present fewer obstacles to performance, and the better-known revised version was performed in 1927. But, as well as the sharp perspective of the offstage ‘banda’, many of the more intimate, chamber music-like passages were excised, lessening the impact of the famous, overpowering “funeral march”; the instrumentation is in parts watered down, playing much

more “safe”; and especially, the stark, stabbing sffff chords of the shattering ending are robbed of impact, being covered by sustained wind and brass. We take great joy in re-establishing this magnificent work as Varese first heard it in his inner ear.

ECUATORIAL, for bass voices, two Ondes Martenot and ensemble (New York 1932-1934)

Perhaps in respect of no other work of Varese is one of his favourite remarks more appropriate: “I like a certain awkwardness in a work of art.”

For Ecuatorial represents the raw savagery of human sacrifice, whose brutality Varese brings vividly to life in highly unconventional vocal writing that calls for fortissimo nasal singing through closed lips, humming, mumbling, Sprechstimme, “percussive declamation”, glissandi, “raucous” speaking, quarter- tone intonation and so on. Though, earlier in the life of this work, he had called for a solo bass voice, his later prescription of small chorus — the present performance uses six solo voices — seems more in keeping both with the import of the text and the manner of setting for voices, so far outside of any style hitherto employed in western art music.

Indeed, writing to Odile Vivier about Ecuatorial in 1961, with a directness that cannot be contradicted he specifies: “Chorus: bass voices, above all, no church singers. At all costs avoid the constipated and Calvinists.”

The sacred book of the Quiche tribe of the Maya civilisation, the Popol Vuh, has come down to us solely in a translation made in 1707 by Father Francisco Ximenes, of the Dominican order. The Quiche language text, which he — fortunately! — reproduces in parallel with his Spanish translation, was almost certainly made after the Spanish Conquest of the 1520s, perhaps by a late surviving Quiche Indian who had learned the European alphabet; for the original language was a pictographic script. Any earlier manuscripts have long since disappeared, as too the source text from which

8.557882 6

Father Ximenes worked; he returned it to its owner after making his translation, and it has never again surfaced. The Popol Vuh is a creation myth on a par with the Epic of Gilgamesh and with the oral traditions of the Australian aboriginal “Dreamtime”, and incidentally provides us with the fullest intimate portrait we have of the nature of the Mayan civilization. It is also a scriptural text of this most ancient of western- hemisphere civilizations. Alongside the cruelty of a fertility cult and human sacrifice are a sense of true wonder in the face of nature, of awe and respect for the unknowable gods, and a thorough attempt to provide a framework of social structure, of laws and of ethical principles as boundaries for human action.

Though Stravinsky in early versions of Les Noces (circa 1916) had sought to combine the mechanical Pianola with normally played “live” instruments, Ecuatorial is the first work in the history of music to attempt the fusion of traditional and electronic instruments. Varese knew Leon Theremin, creator of arguably the first ever musical instrument to generate sound by electronic means, and commissioned special instruments from him for the first version of Ecuatorial, capable of an astonishingly high range reaching to 12,544.2 Herz, some three octaves above the highest note of the piccolo. Odile Vivier, in a biography of Varese that offers interesting sidelights, cites the composer as declaring, during his work with Theremin: “I will compose no more for instruments to be played by men: I am inhibited by the absence of adequate electronic instruments for which I conceive my music.” It later became clear, however, that the Onde Martenot, with its keyboard and ‘Ruban (a device for making a glissando with continuous pitch, i.e. without intervening divisions into semitones), offered a far more precise means of realizing the music Varese wished.

In a convincing analysis of the work, the young composer and musicologist Brian Kane points out that, following the last brass “explosion” in the work, the conventional instruments disappear, are wiped out, leaving only the (electronic) organ and the two Ondes Martenot. His observation is that this radical rupturing

of the musical texture offers us a “sonic image of the tribe’s survival”. My own view is that, perhaps, in a mystical way, through his depiction of the lost spiritual world of a time deep in the past, Varese was seeking to show a path to the even more unknowable future of humankind.

NOCTURNAL, for soprano solo, bass voices and chamber orchestra (New York 1961) Edited and completed from the composer’s notes and sketches by Chou Wen-Chung in 1969

“If light travels faster than sound, in the case of Varese, sound traveled much faster.” (Ana'is Nin)

The last practicable, realizable complete work of Varese received a tortured premiere at a famous concert conducted by Robert Craft at New York’s Town Hall on 1st May 1961; for, in the later part of his life, Varese was not only wrestling with illness, but was less satisfied than ever with the means at his disposal that fell so far short of the rich and infinitely malleable sound-world of his imagination. Thus, he completed in time for the concert (a “Composer Portrait” in his honour) only just over half of the score presented here; and what was performable was handed to Robert Craft and his musicians piecemeal in barely legible parts only two days before the performance — just in time for a single rehearsal. The other works on that concert programme were Integrates, Poeme electronique, Offrandes, Deserts’, and, in its first performance since its premiere in 1934, Ecuatorial, with two “oscillators” played by Earle Brown and the engineer Fred Plaut, in lieu of the Ondes Martenot that were no more available in New York than Theremins and the musicians to play them.

Nocturnal began life in the composer’s imagination as an Ecuatorial-like setting of invocations from various ancient civilisations. Later, he investigated poems such as Henri Michaux’s Dans la Nuit, and work by Novalis and St John of the Cross before finally choosing

7 8.557882

fragments in English from the early writings of his close New York friend (and fellow expatriate) Anai's Nin as the skeleton upon which this music is constructed. The chorus of male voices sings almost exclusively nonsense syllables of Varese’s invention, which indeed recall Ecuatoriai, while the soprano’s disjointed phrases relate closely to Anai's Nin’s tortured relationship with her father. If her 1935 book The House of Incest is to be believed as autobiographical narrative rather than dream-allegory, she was raped by her father in her childhood, only to take “revenge” by seducing him as an adult, enticing him into an extraordinary, nine-day erotic adventure. She had prepared for this decisive encounter in her earlier love affair with Henry Miller (another friend of Varese, who enshrined the composer in his remarkable indictment of America, The Air- conditioned Nightmare), and in her attempt to seduce the well-known homosexual Antonin Artaud. It had been with Artaud, among many other authors, that Varese had sought to develop his ultimately unfulfilled project for the opera L’Astronome.

Like Varese, Anai's Nin had fled the France of her birth for the life-renewing anonymity of New York because, in part, of a seemingly unhealable rupture with her father. There can be little doubt that Varese’s profound identification with Anai's Nin’s work was closely connected with her experiences of incestuous rape by her father, on the one hand; and Varese’s suppressed parricidal relationship with his father, on the other.

A little over half of Nocturnal was completed by Varese, and though the fragment, composed typically in a great hurry under commission from the Koussevitzky Foundation was performed at the May 1961 concert, the composer did not further advance the work in the four years of life that remained to him. He did, however, leave extensive sketches. These were skillfully joined to the existing fragment in 1980 by the composer’s amanuensis Chou Wen-Chung, and the work has ever since been performed in this form.

T.S. Eliot’s profound observation, “in my beginning is my end” reminds us that Nocturnal describes a full circle from Varese’s earliest surviving composition, Un

grand Sommeil noir, written when he was 23. Night, darkness, solitude, isolation, the ultimate loneliness, unknowability and unreachability of the individual human soul are themes that permeate all of his work.

DANCE FOR BURGESS, for chamber orchestra and percussion (New York 1949) restored and edited by Chou Wen-Chung in 1998

Varese’s unrealised Espace, which occupied him almost continuously from 1932 until 1949, and intermittently until the end of his life — though incomplete, fragments are performable and remain a fascinating conundrum — stands indirectly in the pedigree of the dashed-off occasional piece Dance for Burgess.

An early version of Etude pour Espace, for chorus with the wind orchestra part adapted for two pianos, was performed in 1947, but left Varese deeply dissatisfied. Thus he embarked upon transforming sketches for Espace into a new work. Deserts (Naxos 8.554820). He proposed to Burgess Meredith a cinematic montage of sound and images based upon Deserts, and the two agreed to collaborate on a film which, however, never materialised. In the meantime, Meredith had embarked upon production of an unconventional Broadway musical called Happy as Larry, in which his collaborators were the choreographer Anna Sokolow and the sculptor Alexander Calder, the latter supplying sets in the form of his customary mobiles. As a gesture of friendship — and hoping that the deferred film would eventuate later — Varese composed this brief dance, which was performed a handful of times before the production closed in its first week, on 7th January 1950.

Varese was no Broadway composer, yet, with an astringency that is unique to his musical voice, he succeeds in making a few sly allusions to the rhythms and “swing” of “uptown” Jazz. Though a curiosity, this little work reminds us that Varese was a skilled professional composer who could turn his hand and his technique to any medium. The scant productivity of his later years was a consequence less of a “block”, than

8.557882 8

simply of his extreme self-criticism, and the near impossibility of finding the technical means to realize his inner vision.

TUNING UP, for large orchestra (New York 1947) reconstructed from sketches by Chou Wen-Chung in 1998

Chou Wen-Chung relates the story of the origin of Tuning Up as an all-too typical illustration of the ways in which Varese and his musical vision found it hard to win comprehension. In 1947, Boris Morros was producing a film called Carnegie Hall, featuring many musicians such as Fritz Reiner, Bruno Walter, and Leopold Stokowski, who had been the earliest champion of Varese’s music in the United States. Varese knew Morros through Walter Anderson, one of the composer’s most loyal advocates and editor of The Commonweal, where Varese’s seminal essay Organized Sound for the Sound Film was published in 1940.

Thus when Carnegie Hall was in production in 1946, Morros approached him through Anderson to compose a short character piece for the New York Philharmonic and Stokowski, parodying the orchestra’s tuning up procedure. It seems that Morros had a light¬ hearted, parodistic skit in mind; whereas Varese, completely in personality, took the project seriously, delivering a score that allows fragments of Ameriques, Arcana, Integrates, Ionisation and other works to emerge from a mist of repeated A’s. He sketched two versions — which Chou Wen-Chung has skillfully woven into a bi-partite score — but was incensed at the distorted and irreverent way his music was played in rehearsal, stormed out, withdrew the score and returned the large cheque he had been paid for its composition. Stokowski, at least, would have recognized the Ameriques references; but, for the work to be taken as a serious gloss upon the inner nature and force of the symphonic beast was more than Varese could possibly have hoped for at this date.

HYPERPRISM, for nine wind instruments and nine percussion (New York 1922-1923)

The first performance of Hyperprism in New York in March 1923 caused something of a scandal, out of all proportion to its brevity. A later performance reviewed by a Parisian journalist remarked that Varese was “the cause of peaceable music lovers coming to blows and using one another’s faces for drums.” At least the earlier tumult bought the work a repeat hearing for the half of the audience that had not left, upon the insistence of Carlos Salzedo, co-founder of the International Composers Guild. Stokowski took up the work, playing it twice in Philadelphia in November of the same year, and again in New York in December. Though audience response was just as mystified, that very first March performance did gain Varese a publisher, for John Curwen had been in the audience, and took Varese’s scores back to London.

The title might be interpreted as referring to crystalline structures, with which Varese was famously fascinated. He sought out Nathaniel Arbiter, professor of mineralogy at Columbia University, who taught him that “crystal form itself is a resultant rather than a primary attribute. Crystal form is the consequence of the interaction of attractive and repulsive forces and the ordered packing of the atom.”

Thus, in Varese’s own words, “taking the place of linear counterpoint, the movement of sound-masses, of shifting planes, will be very clearly perceived. When these sound masses collide, the phenomena of penetration or repulsion will seem to occur.” And elsewhere, “This [description of crystalline structure], I believe, suggests better than any explanation I could give about the way my works are formed. There is an idea, the basis of an internal structure, expanded and split into different shapes or groups of sound constantly changing in shape, direction and speed, attracted and repulsed by various forces. The form of the work is the consequence of this interaction. Possible musical forms are as limitless as the exterior forms of crystals.”

9 8.557882

Wilfred Mellers observes, “it is not surprising that Varese’s highly sophisticated music should be also primitive ... in the sense that it does not involve harmony, but rather consists of non-developing patterns and clusters of noises of varying timbre and tension. These interact in a manner that Varese has compared, in detailed if inaccurate analogy, to rock-formation and crystal mutation.”

Hyperprism was the first work of Varese’s that Curwen published, giving it a Witold Gordon cover that features a galleon-like ship decorated with stars, its detached aft section surprisingly like a rocket poised for take-off, a star-encrusted dove carrying an olive branch catching up on the ship from behind, thus clearly labeling it a Noah’s Ark of music. Not a crystal nor a prism in sight; but journeys into the unknown clearly symbolised.

UN GRAND SOMMEIL NOIR, for soprano and piano (Paris 1906) Poem by Paul Verlaine

This brief work, the sole surviving composition of Varese’s early period (apart from juvenilia), was nearly lost. It is well known that, following his period of study with Busoni, Varese left behind in storage in Berlin the majority of his early scores and sets of orchestral parts, and that these were lost in a warehouse fire. Later, probably as late as 1962, he destroyed any remaining early scores that were left, including the manuscript of Bourgogne. But Un grand Sommeil noir had been published, and copies of the printed edition were held by a few libraries. Chou Wen-Chung vividly recalls Varese’s rage upon discovering that the New York Public Library held a copy of Un grand Sommeil, having believed that he had destroyed all extant copies. It is intriguing, too, that, despite having been a published, engraved score, this work is not listed either in Fernand Ouellette’s definitive Edgard Varese of 1966, and is overlooked in Chou Wen-Chung’s Varese: A Sketch of the Man and his Music, also of 1966. It had turned up in 1957, but was often forgotten.

8.557882

Stravinsky set the same poem four years after Varese, in 1910, as one of his Two Songs of Verlaine, first performed, however, in St Petersburg and published there by Jurgenson. Did he know Varese’s setting? It is unlikely, though the two men did indeed first meet during the early years of the Ballets Russes incursions to Paris. No matter: Varese’s score had been written while he was a student in Widor’s composition class at the Conservatoire — coincidentally, too, while he was living, in the first year of his first marriage (to the actress Suzanne Bing), on the selfsame rue Descartes, where Verlaine had died in poverty just ten years before. This score is accomplished, penetrating and individual, despite many signs of the work of another of Varese’s early admirers, Claude Debussy; the open fifths of La Cathedrale engloutie, melancholy melodic lines reminiscent of La Damoiselle elue\ even, as pointed out in a brilliant article by Larry Stempel, a near-quotation of the closing bars of Pelleas et Melisande. Restraint, clarity and an avoidance of overt emotion are the main characteristics of this setting. His other, lost works of this period must have been of at least this quality and better, for in the next year, 1907, Widor and Massenet had promoted Varese for the Premiere Bourse artistique de la ville de Paris', when he failed to get it, they placed in his way other, mysterious private funds that enabled him to travel to Berlin, there to come within the ambit of the next great influence of his life, Ferruccio Busoni.

DENSITY 21.5, for solo flute (New York 1936, revised April 1946)

Though this brief work is the sole composition that punctuates an otherwise twenty-year gap of finished scores from Varese’s hand, the composer was constantly busy with a never-ending stream of sketches and uncompleted projects. These were the years, indeed, during which he made fruitless approaches to Bell Laboratories and others — including three unsuccessful applications for Guggenheim Fellowships — in the hope of being able to develop his revolutionary ideas of a possible new realm of electronic music. Between

10

Ecuatorial (1932-34) and Deserts (1954), these two pages are, however, the only finished music that the composer allowed to leave his desk. A request from the flautist Georges Barrere was the immediate stimulus that brought forth a manuscript, which refers to Barrere’s new platinum flute, enshrining the specific density of the rare metal within its title, in a way that points forward somewhat to naming habits of Iannis Xenakis twenty and more years later.

Density is challenging despite its brevity. Its short duration is based upon stark juxtapositions of powerfully contrasted musical “shapes of sound” (Varese’s phrase) or self-contained musical objects. Rather than a formal trajectory, its structure is rather like a tour around a set of boulders or sculptures, examining them from different points of view, with an absence of exact repetition of any kind. However, as relayed by Hilda Jolivet from a programme note by Varese, traditional development of melodic motifs or expansion of an implied harmonic scheme are not absent: “Despite the monodic character of Density 21.5, the rigidity of its structure is defined overtly by the harmonic scheme carefully described in the unfolding of the melody.” Two years earlier, Varese had declared, moreover, “... [in contemporary music], whether we deny its presence or not, we sense a tonality. There is no need to have a tonic, with its third and fifth, in order to establish a tonality.” Audible are musical “shapes” based upon: pivoting semitones and octave-displaced expansions of these; upon the tritone; upon the minor third; upon repeated pitches; and, occasionally, longer phrases built upon strings of these components assembled together. The work ends with an ascending sequence of nine different pitches drawn from these components, and organized in three mimicking yet dissimilar sub-phrases, that rise from the lowest note of the flute’s compass to, almost, its practicable highest note; summing up, as it were in these nine notes and two measures, the entire piece.

IONISATION, for thirteen percussion, with piano New York 1929-1931

“Rhythm is too often confused with metrics. ... the regular succession of beats and accents has little to do with the rhythm of a composition. Rhythm is the element in music that gives life to the work and holds it together. It is the element of stability, the generator of form. In my own works, for instance, rhythm derives from the simultaneous interplay of unrelated elements that intervene at calculated, but not regular time lapses.'” (Edgard Varese) [Italics added for emphasis by author of these notes].

Ionisation is one of the most famous works of the twentieth century; the first western art music work by any composer to limit itself solely to instruments of percussion, almost all of them unpitched. However, already in Varese’s orchestral scores — Ameriques and Arcana, and also in the smaller Hyperprism and Integrates — large percussion ensembles entirely typical of Ionisation in make-up and usage are found; Ecuatorial and Deserts were later to follow the same pattern. Indeed in Ameriques, a larger number of percussion players is required even than in the present score, and numerous passages feature them as a kind of separate, parallel orchestra. Even the use of the piano on the last three pages of this score is restricted to a percussive amplification of the sonority of the tubular bells, whose percussive attack is of the essence. Pitch is immaterial; the piano and bells supply only resonance and sustained sounds. Did Varese know Gamelan, or Gagaku? Gamelan, probably yes, through Debussy; but what he sets out to do in Ionisation is of a different order, for, in the absence of pitch — other than differentiations of high, medium, low, and the associated implications of skin, metal and wood tone colours — he creates blocks of highly characterized classes of sound (he calls them “shapes”) which interpenetrate, attract and repulse, exactly as the

11 8.557882

sculpturally formed musical gestures in Hyperprism, Octandre and Integrates.

In all of Varese’s percussion writing, from Ameriques onwards, there is more than just rhythmic polyphony at work; rather, a kind of polydirectionality of musical impulse, richly layered. It is his stated aesthetic to seek a music in which mutually oblivious, if not totally unrelated universes converge, collide, briefly coexist, then disappear once again into their separate dimensions of the cosmos. His fascination with the capabilities of — in his day — a still unrealized “machine” that would perform music with a hitherto unachievable accuracy posits the ease with which it would achieve

“new dynamics far beyond the present human- powered orchestra ... cross-rhythms unrelated to each other, treated simultaneously, or, to use the old word, contrapuntally, since the machine would be able to beat any number of desired notes, any subdivision of them, omission or fraction of them - all these in a given unit of measure or time that is humanly impossible to attain.”

Even a modest analysis of Ionisation requires fifty or more pages. For the present note, may it suffice to draw the listener’s attention to an opening section primarily for drums, led by a driving, but soft, rhythmic figure in the military drum; a wrenching change of tempo into triplet figures, led by claves, cencerros and small cymbals — here, the figures of the preceding section

interpenetrate the new material, now alternating with a powerful quintuplet figure in rhythmic unison for five players; soon, the introduction of variegated metallic sounds, for anvils, suspended cymbals, gongs, tam-tams and triangles, with underlying siren drones; a culmination in which the opening rhythm for military drum is now heard on the tarole, a smaller cousin; leading to the concluding, clangorous coda for tubular bells, piano, glockenspiel, tam-tams.

I am not the first to point out that the coda of Ionisation resembles nothing so much as the concluding pages of Les Noces; most especially in the way in which time seems to slow down. The space between musical events is distended; resonance becomes more important than propulsive force; resolution is implied by a circularity of “pitch field” repetitions — not motivic in the least, simply reinforcing the static harmonic quality of this point, nay period of arrival. In a sense, these last three pages and seventeen measures of the work are a kind of long fade. The bell sonorities take the place of the tam-tams and sirens of the body of the piece, while the rhythmic motives of the various drums chatter ever more softly in the background like snatches of conversation disappearing into the distance. Finally, only the bells, tam-tams and suspended cymbal remain. Thus it is that, with mystery and trepidation, we farewell the music and the world of earlier times and set forth into the great unknown, those “new worlds on earth, in outer space and in the minds of men”, “an entirely new magic of sound!”

© 2007 Christopher Lyndon-Gee

8.557882 12

Elizabeth Watts

Bom in 1979, Elizabeth Watts was a chorister at Norwich Cathedral and studied archaeology at Sheffield University, graduating with first class honours. In 2002 she won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music, where she studied with Lillian Watson on the Advanced Opera studies course at the Benjamin Britten International Opera School. In 2004 she was selected for representation by YCAT before graduating from the Royal College in 2005 with distinction. She has received the Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother Rose Bowl, on top of numerous other prizes and awards, including the RCM Lies Askonas Prize, the Maggie Teyte Prize and the Royal Over-Seas League vocal section prize. Most recently she received international acclaim representing England at the 2007 Cardiff Singer of the World Competition, reaching the final and winning the prestigious Rosenblatt Recital Song Prize and automatic selection for BBC Radio 3’s prestigious New Generation Artists Scheme. This follows on from other recent successes including the 2006 Kathleen Ferrier Prize, the 2007 Outstanding Young Artist Award at the MIDEM Classique Awards in Cannes, and a nomination for the 2007 Royal Philharmonic Society’s Young Artist of the Year Award. As an alumna of the Britten-

Pears Young Artist Programme in Aldeburgh, she has appeared at the Purcell Room, Bridgewater Hall, Wigmore Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall and Aldeburgh Festival, among many others. Her operatic work has included the roles of Flora (The Knot Garden) in a Music Theatre Wales / Royal Opera House co-production, the title role in a British Youth Opera production of Handel’s Semele and the role of Arthebuze in a semi-staged performance of Charpentier’s Acteon conducted by Emmanuelle Haim at the Aldeburgh Festival. Roles at the RCM included Flora (The Turn of the Screw), Poppea (Agrippina), Elmira (Sosarme), Fulvia (Ezio) and Constance (Dialogues des Carmelites). Between 2005 and 2007 she was a Company Artist at English National Opera on their Young Singers’ Programme making her debut as Papagena (Die Zauberflote). Roles since then have included Music and Hope (Orfeo), both for English National Opera and with the Boston Handel and Haydn Society, various roles in Purcell’s King Arthur, again for ENO and in Berkeley California in collaboration with the Mark Morris Dance Company, and Barbarina (Marriage of Figaro). Elizabeth Watts is much in demand as a recitalist and concert singer, giving recitals at venues such as the Wigmore Hall, as well as at festivals and music clubs throughout the United Kingdom.

13 8.557882

Maria Grochowska

Maria Grochowska graduated at the Music Academy in Katowice in the flute class of

Marian Katarzynski and in the chamber music class of Andrzej Janicki. During her studies

she participated in courses and music festivals (Munich, Weimer, Eger, Miskolc),

performing as a soloist and chamber musician, a member of the woodwind quintet Silesia.

Since 1979 she has been a principal flautist in the Polish National Radio Symphony

Orchestra, with which she has played concerts in many cities in Poland and abroad. She

has made many commercial and radio recordings, performing solo parts in works of

Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Richard Strauss, Brahms, Beethoven, Debussy, and Bizet. She has

been a member of the Silesian Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra, Polish Chamber

Orchestra ‘Sinfonia Varsovia’, and National Philharmonic. With those orchestras she has

toured on many occasions, collaborating with eminent artists and conductors. She has

played concerts among others with the Silesian Quartet and Camerata Vistula. She holds

the position of senior lecturer at the Karol Szymanowski Academy of Music in Katowice.

Camerata Silesia - The Katowice City Singers’ Ensemble

Camerata Silesia, The Katowice City Singers’ Ensemble, founded in 1990 by Anna

Szostak, is a team of vocalists, who sing as a chamber ensemble and perform solo parts for

vocal and instrumental music as well as in unaccompanied choral repertoire. In a short

time the Camerata Silesia has become the most instantly recognizable Polish ensemble

specialising in performance of both early and contemporary music. The singers’ unusual

technical efficiency, along with a style of singing and intonation appropriate to the early

music performance canon, has attracted the attention of both critics and composers. The

former have been generous with praise while the latter have composed pieces specifically

for the ensemble, dedicating them to various singers and to the conductor, who were all

specially sought out for first performances of these pieces. The choir’s discography

embraces thirteen releases, which have repeatedly been awarded prestigous phonographic awards. www.camerata.silesia.pl

Anna Szostak

Anna Szostak is among the most outstanding choral conductors in Poland. She has received many

prizes at singing contests: at the International Choir Festival in M^dzyzdroje (1982), at the Legnica

Cantat All-Polish Choir Competition (1983, 1986), and at the Holsatia Cantat International Choir

Competition w Neumiinster (1990), among others. In 1993 she was awarded a Ministry of Culture

and Arts Prize for her special cultural achievements. In 2004 she was awarded the Jerzy

Kurczewski Prize, the only prize of this type in Poland, for achievements in the choral field.

8.557882 14

Thomas Bloch

Thomas Bloch is acknowledged as a leading specialist in the rare

instruments he plays, the glassharmonica, Onde Martenot, and cristal

Baschet (see www.chez.com/thomasbloch). He has given more than 2,500

performances in thirty countries and has taken part in more than eighty

recordings in various styles as a musician or a composer. As a soloist, he has

performed on the soundtracks of Milos Forman’s Amadeus and The March

of Penguins (Oscar 2006), with rock bands Radiohead, Gorillaz {Monkey:

Journey to the West), with Marianne Faithfull, Tom Waits and Bob Wilson

{The Black Rider), Vanessa Paradis, Zazie, Manu Dibango, Fred Frith, Alan

Alda, Isabelle Huppert, Sally Potter, John Cage, Paul Sacher, Jean Foumet,

Dennis Russell-Davies, Michel Plasson, Myung-Whun Chung, Antoni Wit, Arturo Tamayo, Jean-Fran?ois Zygel, Jay Gottlieb, Roger Muraro, Maurice Bourgue, Vladimir Mendelssohn,

Alexei Ogrintchouk, Alex Balanescu, Marc Grauwels and many others. Concert performances include La Scala

Milan, the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra (for the centenary of the orchestra), the

Paris Opera, and concert halls in New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Los Angeles, London, Sydney, Tokyo,

Mexico, Bogota, Kuhmo, Prague, Berlin, Madrid, and Lisbon, among others. Bloch teaches Onde Martenot at the

Strasbourg Conservatoire and is responsible for presentations at the Paris Musical Museum. He is musical director

for the Evian Music Festival and received (with others) First Prizes for Onde Martenot at the Paris Conservatoire

(with Jeanne Loriod) and the 2002 Midem Classical Music Award for Messiaen’s Turangalila-Symphonie (Naxos

8.554478-79 with Antoni Wit, Francis Weigel and the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra). He has

recorded for all major companies. Since 1998, his recordings for Naxos have included Music for Glass Harmonica (8.555295) and Music for Ondes Martenot (8.555779), among others.

Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra (NPRSO)

The Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra of Katowice was

founded in 1935 in Warsaw through the initiative of the well-

known Polish conductor and composer Grzegorz Fitelberg, under

whom the orchestra worked until the outbreak of World War II. In

March 1945 it was revived in Katowice by the eminent Polish

conductor Witold Rowicki, and in 1947 Grzegorz Fitelberg

returned to Poland and became its artistic director. He was

succeeded by leading Polish conductors, among others Jan Krenz,

Kazimierz Kord and Antoni Wit. The orchestra has appeared with

conductors and soloists of the greatest distinction, including

Leonard Bernstein, Neville Marriner and Kurt Masur, and has

toured most European countries as well as the Americas and countries of the Near and Far East. It has recorded over

190 compact discs for Polish and international record companies. For Naxos, the NPRSO has recorded over seventy

discs, among them the complete symphonies of Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Schumann and Penderecki.

15 8.557882

Christopher Lyndon-Gee

Christopher Lyndon-Gee was nominated for Grammys in 1998 for Best Orchestral

Performance for the groundbreaking complete works of Igor Markevitch (Marco Polo), in

2003 for the world premiere recording of George Rochberg’s Symphony No. 5 on Naxos

American Classics, and again in 2007 for Hans Wemer Henze’s Violin Concertos Nos. 1 & 3,

with Peter Sheppard Skaerved. In 2001-2002 recordings for Naxos of Arcana and other

works by Varese, with the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra received acclaimed

notices worldwide, while The Gramophone, Fanfare, Classics Today and Penguin Guide to

Compact Discs have all recognised his work, the last with numerous Rosettes and a Key

Recordings listing. Australian critics’ organizations named him Artist of the Year and Best

Opera Conductor, the latter for his conducting of the world premiere of Larry Sitsky’s The

Golem at Sydney Opera House. Also a widely performed composer, Lyndon-Gee was

awarded a prestigious composition prize by the Onassis Foundation, Athens, in 2001. He

has won the Adolf Spivakovsky Prize, the Sounds Australian Award (three times), and two

MacDowell Fellowships. He is currently working on major orchestral works including The

Auschwitz Poems, Socrates’ Death (intended for performance at Canterbury Cathedral, in

his native England), and a second commission for the German conductor Eckart Schloifer,

... und unter den Blattern safi Er, weinend. During 2003 his setting of an ancient Greek Ode under the title The Temple of

Athena Pronaea had its premiere in New York. In the same week, On the Theory of Cosmic Strings received its premiere

by Peter Sheppard Skaerved at the Odense Festival, Denmark, and has since been performed over fifty times. Frammento

del Dante, a setting of lines from the Paradiso, was commissioned by the Echo Klassiek Preis-winning German ensemble

SingerPur, and had its premiere in Florence in 2006. Lyndon-Gee is now working on a further work for SingerPur, Lieder

des Morgensterns. In 2004 he co-ordinated eight composers (including himself) to set the work of the American poet

laureate William Meredith in honour of Meredith’s 85th birthday, for a “Songbook” recital that toured worldwide in more

than 22 performances. A 25th Anniversary Presteigne Festival Commission, Over Litton, after a poem of Edward Storey,

had its premiere in 2007. Lyndon-Gee studied under Arthur Hutchings and Rudolf Schwartz in Great Britain, Franco

Ferrara and Goffredo Petrassi in Italy, and Igor Markevitch at Monte Carlo. Hearing him conduct a student concert in

Rome, Leonard Bernstein invited him to Tangle wood, where he met Bruno Madema, becoming the latter’s assistant in

Milan. Erich Leinsdorf and Maurice Abravanel were also influential on his work. He enjoyed a busy early career as

pianist, specialising in contemporary repertoire; over 200 new works were written for him, by composers such as Oliver

Knussen, Jonathan Lloyd, Nicola LeFanu, David Bedford, Mauro Cardi, Ada Gentile, Silvano Bussotti and many more.

Since 2005, he has conducted regularly at the prestigious Warsaw Autumn Festival; at the 2007 Jubilee Fiftieth

Anniversary Festival, he conducted four world premieres by distinguished Polish, Lithuanian and Slovakian composers;

in late 2006 he led the closing concert of the eight-day Festival entirely devoted to the works of leading Polish composer

Pawel Szymanski. As Music Director of the Adelphi Symphony based on Long Island, New York, he has gathered an

orchestra of predominantly Russian and Ukrainian expatriate musicians, in programmes featuring music of Peteris Vasks,

Louis Andriessen, Alfred Schnittke, Joanne Metcalf, Sidney Boquiren, Arvo Part and rare American performances of

works such as Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 13 ‘Babi Yar , Messiaen’s Trois Petites Liturgies, Monteverdi’s Vespers of

the Blessed Virgin, as well as many new works. He serves also as Chair of the Music Department at New York’s Adelphi

University. His hectic freelance career includes regular visits to orchestras in Germany, Poland, Italy, England, The

Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, Russia and several other countries.

8.557882 16

[2] Ecuatorial

Spanish translation of the original Quiche text

made in 1707 by Father Francisco Ximenes

Oh constructores, oh formadores

Vosostros veis, vosostros escuchais,

No nos abondonais!

Espiritu del cielo

Espiritu de la tierra Dadnos nuestra descendencia, nuestra posteridad

Mientras hai dfas, mientras hai albas

Que numerosos sean los verdes caminos

Las verdes sendas que vos otros nos dias.

Que tranquillas, muy tranquillas esten las tribus.

Que perfectas, muy perfectas sean las tribus.

Que perfecta sea la vida la existencia que nos dais.

Oh, maestros gigantes

huella del relampago esplendor del relampago,

Gavilan.

Maestros, magos, dominadores poderosos del cielo

Procreadores, engendradores.

Antiguo segreto, antigua ocultadora

Abuela del dia, abuela del alba.

Que la germinacion se haga, que el alba se haga.

Hengh, hongh, whoo.

Salve bellezza del dfa,

dadores del amarillo del verde

Hoo, ha ...

dadores de hijas de hijos

Hongh! hengh, whoo, hengh ...

dad la vida la existencia a mis hijos a mi prole,

Que no haga ni su desgracia, ni su infortunio

vuestra potencia, vuestra hechicherfa.

Que buena sea la vida de vuestros sostenes

de vuestros nutridores

Antes vuestras bocas, antes vuestros rostros

Espiritus del cielo

Espiritus de la tierra

Hooo, oh, ah ...

Whoo, heoh, ha ...

Oh creators and builders, you who have given us shape.

You who see all, you who hear all. Do not abandon us!

Spirit of the heavens

Spirit of the earth

Grant us that our line may continue, our posterity endure

Whilesoever there are days, while the dawns still come.

We ask that verdant pathways be many,

Those green walkways that you have given us.

May the tribes be peaceful, exceeding peaceful.

May the tribes be perfect, exceeding perfect.

May we live in perfection the existence that you give us.

Oh giant beings and masters,

Pathways of the lightning, splendour of the lightning. Falcon.

Masters, magicians, all-powerful lords of the sky, Procreators and begetters.

Ancient secret, ancient hidden mystery

Ancestress of the day, ancestress of the dawn.

Let there be fruitfulness, let there be dawn.

Hengh, hongh, whoo.

All hail to the beauty of the day.

Givers of yellow and of green

Hoo, ha ...

Givers of daughters and of sons

Hongh! hengh, whoo, hengh ...

Grant life and existence to my children and to my line.

Let them suffer neither disgrace nor misfortune

Either because of your power, or your sorcery.

May their lives be filled with good, those who uphold you,

those who offer you sustenance

before your mouths, before your faces

Spirits of the heavens

Spirits of the earth

Hooo, oh, ah ...

Whoo, heoh, ha ...

17 8.557882

Dad la vida, dad la vida Hohe, whoo, dad la vida

Oh fuerza envuelta en el cielo en la tierra

En los cuatro angulos

En las cuatro extremidades

En tanto exista el alba

En tanto exista la tribu.

Grant life, grant life Hohe, whoo, grant life

Oh all-encompassing force of the heavens and of the earth

At the four comers thereof

At the four extremities

For as long as the dawn exists

For as long as the tribe exists.

[7] Un grand Sommeil noir

Paul Verlaine (1844-1896)

Un grand sommeil noir tombe sur ma vie

dormez tout espoir, dormez toute envie.

je ne sais plus rien

je perds la memoire du mal et du bien

Oh! la triste histoire

Je suis un berceau qu’une main balance

au creux d’un caveau

Silence, silence.

A great dark sleep descends upon my life

let all hope fall into sleep, all desire

I no longer know anything

I have lost all recollection of good or of ill

Aah! the sadness of this recounting

I am a cradle, suspended by a hand

over the brink of a chasm

Silence, all is silence.

8.557882 18

Also available:

NAXOS .liijijyyiPi MESSIAEN

Turangalila Symphony L’ascension

DDD

8.554478-79

Francois Weigh Piano * Thomas Bloch, Ondes Martenot

National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra Antoni Wit

2 CDs

8.554478-79

19 8.557882

VARESE Orchestral Works • 2

Watts • Grochowska • Bloch

Men’s Voices of Camerata Silesia

Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra Christopher Lyndon-Gee

® & © 2008 Naxos Rights International Ltd.

DISC MADE IN CANADA A C

W H B H M NAXOS juuiyjyjL

8.557882

□ Ameriques 0 Ecuatorial 0 Nocturnal □ Dance for Burgess

0 Dining Up 0 Hyperprism H Un grand Sommeil noir

0 Density 21.5 0 Ionisation

*FoRMANCE, BROADCAS'f^6 "s

/reo