validation book

Transcript of validation book

-

8/7/2019 validation book

1/15

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by: [UNAM Direccion General de Bibliotecas]On: 8 August 2008Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 788841234]Publisher Taylor & FrancisInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Analytical LettersPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713597227

Analytical Method Development and Validation for the Academic ResearcherIra S. Krull; Michael Swartz

Online Publication Date: 01 January 1999

To cite this Article Krull, Ira S. and Swartz, Michael(1999)'Analytical Method Development and Validation for the AcademicResearcher',Analytical Letters,32:6,1067 1080

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00032719908542878URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00032719908542878

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial orsystematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contentswill be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug dosesshould be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directlyor indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713597227http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00032719908542878http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdfhttp://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdfhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00032719908542878http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713597227 -

8/7/2019 validation book

2/15

ANALYTICAL LETTERS, 32(6), 1067-1080 (1999)

MINI-REVIEW

ANALYTICAL METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION FORTHE ACADEMIC RESEARCHER

Ira S. Krull*Department of Chemistry, 102 Hurtig Building, Northeastern University,

360 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA.and

Michael SwartzPharmaceutical Market D evelopment R&D, Waters Corporation,

34 Maple Street, Milford, MA 01757, USA.

INTRODUCTION

During the course of our scientific careers, and after reading numerousoriginal research papers and reviews submitted for publication to various journalsor books, it has become apparent to us that many, if not most, academicresearchers have little use for method validation studies or demonstrations. Now,that may sound a bit harsh or a strong way to start this mini-review, but this

* Author to whom correspondence and reprint requests should be addressed.

1067Copyright 1999 by Marcel Dekker, Inc. www.dekker.com

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

3/15

1068 KRULL AND SWARTZsituation has been our collective impression after carefully reading andcomm enting on hundreds of submitted journal manuscripts over perhaps the past25 years.Many papers that are submitted for publication involve some type ofmethod development, be that in high performance liquid chromatography(HPL C), high performance capillary electrophoresis (H PCE ), mass spectrometry(MS) or other analytical techniques. Unfortunately, most papers from academiado not usually include attempts to partially or fully validate methods. This is veryunfortunate, because the reader is not apprised as to the status of validation of themethod being described, and most importantly, whether or not the method canindeed be routinely applied by other analysts in other laboratories with the sameor similar instrumentation and skills. In many manuscripts, there is a glaringomission of analytical figures of merit, such as limits of detection or quantitation,calibration plots, accuracy and precision, robustness, and reproducibility. Thereis also often an omission of repeat measurements on the very same sampleextract, no indication o f the number of such repeats (n = 3 , 4, 5, ?) , no statisticaltreatment of the data, nor any application to simulated or real samples for anattempt at method validation. Such papers become of questionable and dubiousvalue to the general reader, especially those analysts that might actually wish toemploy the reported (purported) methods in the very near future. How muchmore work will be needed on the part of those readers in order to learn whetheror not the described methods will really work on their own samples in their ownlabs with their own instrumentation and skills?

This unfortunate state of affairs in submitted and published manuscriptshas resulted in a huge literature of methods that are of really questionable utility,applicability, validity, or value, other than to the authors. How can we changethis sorry state-of-affairs, so that journals and authors of future submittedmanuscripts, will indeed provide some degree of method validation andassurance of applicability and transference of the reported methods? That isreally the gist of this mini-review, to provide the readers with some idea of thealready vast literature in the areas of analytical method validation, for academics

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

4/15

METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION 1069as well as those making submittals to the regulatory agencies, and to try toencourage future authors of analytical manuscripts to routinely include somedegree of method validation in the final manuscripts. What then is really neededon the part of these authors in order to provide some evidence of validation andapplicability to future users?

We are not, at the very outset, suggesting that all academics should in thefuture meet al l US P/ICH (U nited States Pharm acopeia/International Conferenceon Harmonization) guidelines required of FDA (Food and Drug Administrat ion)regulated firms that are making new drug submittals of methods for clinicalstudies (IND, Invest igational New Drug) or actual drug release (NDA, New DrugApplication). That is not our intent, nor do we feel that this would be warrantedor accepted by the analytical community or analytical journal editors. Academicsdo not , by and large, need to provide the same degree of method validation as apharmaceutical or biotechnology firm trying to get a new drug to market. But, atthe sam e t ime, i t wou ld appe ar that mo st jour nals are not requir ing any. degree ofmethod validation to be demonstrated by academic (or industr ial) submitters ofpapers dealing with new analytical methods. It is, too often, left to the discretion(if that is the proper word) of the reviewers, with the editors rarely requestingadditional validation evidence. There are no guidelines that we have ever seen inthe directions to authors of any (!) analytical journals requiring or evensuggesting that some amount of method validation data be routinely suppliedwhen a manuscript is f irst submitted. That appears incredulous and astoundingtoday, but i t seem s very clear in reading any nu mb er of journ al descriptors toauthors for papers to be submitted dealing with method development andoptimization (validation as a word almost never appears) .

What is Required Today of Industrial Firms Submitting New AnalyticalMethods to Regulatory Agenc ies , such as U.S . Food and DrugAdministration?

Perhaps as a point of reference, let us again summarize what is beingroutinely asked by the US FDA of pharmaceutical and biotechnology f irms when

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

5/15

1070 KRULL AND SWARTZ

MethodValidation *

1 *[ Precision 1

^-

*^-

[ Limit of Detection 1

Specificity ]Linearity 1Ranqe )

Robustness 1System Suitability 1

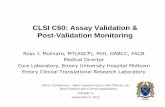

Fig. 1: ICH method validation parameters.

they are submitting an IND or NDA for a new drug substance. There arenumerous reviews and overviews in the area of analytical method validation andUSP/ICH requirements, and we will just summarize the more essential featuresin these1'15. Figure 1 summarizes the ICH method validation parameters, soon tobe adopted by the USP, and what the FDA expects to see for drug methodsubmittals1. The amount of method validation studies and number of validationparameters that must be met changes as a drug proceeds from discovery to PhaseIII and then, it is hoped, final FDA approval of an NDA.

If the drug does not make it through all stages of Phases I-III clinicaltrials, then not all of the validation parameters in Figure 1 need to bedemonstrated. This has all been sorted out by the USP and is discussedelsewhere1'14*16. Whatever the stage of a drug's progress towardscommercialization and introduction, any pharmaceutical analyst must be familiarwith the fundamental terms of Figure 1. Unfortunately, too many academicanalysts and those that develop newer analytical approaches are not always asfamiliar with these terms. Since this mini-review is really being aimed atacademics, we need to critically and correctly define these terms. Variousanalytical textbooks may also be scoured for more in-depth, academic

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

6/15

METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION 1071

discussions of these terms17 '22 . Analytical methods, by and large, are bothqualitative and quantitative, especially with regard to the levels of drugs and/ormetabolites in any given sample. Thus, any validated method must demonstrate,in a reproducible manner, the accuracy of levels determined in real samples.Accuracy, in this context relates to the agreement (or lack thereof) between thevalues determined for the drug of interest and the true or known level actuallypresent. Naturally, small deviations from the true value are usually found, nomethod is 100% accurate, but the closeness of method accuracy is an importantmarker of the overall, final utility and applicability of that method with realsamples.

When the analytical method is repeated on different aliquots of the samesample several times, so that the number of samples is greater than three, and thenumber of repeat injections from each aliquot is also greater than three, then it ispossible to determine precision. It is recognized that no validated analyticalmethod can possibly be done or repeated on the same sample less than threetimes, from start-to-finish, with each workup injected at least three times. In aregulated industry, this is so commonplace and so accepted that it is neverquestioned, especially involving FDA submittals. Only in academia does thisquestion of the number of repeats come into the discussion and be questioned.The closer the agreement amongst the different determinations done on the verysame sample, then the better the precision of that method. The goal, of course, isto demonstrate both high accuracy and precision, within one laboratory and oneanalyst, and then between analysts in different laboratories. Accuracy andprecision therefore become the cornerstones of any quantitative analyticalmethod, and these must be very clearly demonstrated and reproducible. Thatmeans one must have samples of known composition and known levels of theanalytes of interest. The method of demonstrating accuracy and precision caninvolve a variety of practices, such as single-blind, double-blind, interlaboratorycollaborative study, and others1'9"10 .

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

7/15

1072 KRULL AND SWARTZThere are various parts to precision, such as repeatability, intermediate

precision, and reproducibility (ruggedness). Repeatability means how the methodperforms in one lab and on one instrument, within a given day. Intermediateprecision refers to how the method performs, both qualitatively andquantitatively, within one lab, but now from instrument-to-instrument and day-to-day. Finally, reproducibility refers to how that method performs from lab-to-lab, from day-to-day, from analyst-to-analyst, and from instrument-to-instrument,again in both qualitative and quantitative terms.

Limit of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ) relate to theconcentration of the analyte, in a real sample, which produces a certain signal-to-noise ratio, using the currently accepted ICH equations and definitions2 . Thesevalidation parameters need to be demonstrated in order to indicate how themethod functions, in a quantitative sense (LOQ), as one attempts to quantitate ananalyte at lower and lower concentration levels. Limit of detection is aconcentration point where accurate and precise (!) quantitation is not usuallyposs ible, but the qualitative identification of the analyte as being present is. Limitof quantitation or quantification, on the other hand, is a higher level, where itnow starts being possible to accurately and precisely determine the absolutelevels of the analyte present in a given sample.

There are numerous definitions of these terms, LOD and LO Q, dependingon the particular reference source or regulatory guidelines. So long as one definestheir terms, a number of these can be routinely used, but for regulatorysubmittals, ICH guidelines and equations are routinely followed.

Specificity is a term that relates to how well a given method is able touniquely (specifically) determine a given analyte in a sample to the exclusion ofother possible interferents. It refers to how well the method qualitativelyseparates and then identifies that analyte of interest, to the perhaps 100%exclusion of all other substances present in the same sample that might interferein the determination. This is different than selectivity, which is less specific, inthat it may determine the analyte of interest, as well as other similar compounds

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

8/15

METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION 1073in the same sample that are not the analyte itself. True quantitation cannot beperformed until the method is first shown to be specific, and that the peak ofinterest is the analyte of interest, and nothing else.Linearity refers to the calibration plot and its slope of detector responsevs. concentrations injected. There can be external standard calibration plots,internal standard, standard additions, and others, with or without the samplematrix present (e.g., matrix-matched calibration plots)24 . Linearity relates to howwell detector response (peak height or peak area or peak intensity) relates to orcorrelates with increasing concentrations of analyte present. Ideally, thecalibration plot should be linear of several orders of magnitude, including theconcentration levels expected to be found in the final samples.

The ICH defines the linear concentration range depending on the nature ofthe sample and the type of method 1. It is not necessary to demonstrate linearitybeyond the expected concentration ranges, with some extension at both ends, andsurely one is not required by ICH to demonstrate linearity of as many orders ofmagnitude as possible, starting from the LOD or LOQ. There are very practicalreasons for demonstrating a rather limited linearity range for real samples, ratherthan the perhaps academic notion of demonstrating linearity over 5-7 orders ofmagnitude.

Range relates to the linear portion of the calibration plot and its linearity.That is, a calibration plot will be linear over a certain range of concentrations, asabove. This concentration magnitude or spectrum is then defined as the range ofthe method, wherein accurate and precise quantitation should be best realized.Again, it is not necessary according to ICH to demonstrate a range of 10 ordersof magnitude, but rather to limit that range to the samples of interest and theirexpected concentrations.

Robustness is a term that academicians rarely utilize in their papers, butone that ICH and FDA have taken very seriously. It refers to how well themethod performs over small, intentional changes in the method's operationalparameters. Robustness is actually demonstrated by experimentation, by

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

9/15

1074 KRULL AND SWARTZintentionally changing various operating parameters of the method, such as pH,mobile phase composition, flow rates, gradient mixing, temperature, etc.Robustness is measured by noting changes in peak shape, retention time, platecounts, resolutions, and accuracy of quantitation, as these operational parametersare modified. If the chromatographic peak shapes, plate counts, resolutions,retention times, and symmetry do not change much (and that must be defined)with perturbations in the operational parameters, then the method is said to berobust. On the other hand, if these chromatographic figures of merit do changegreatly with small changes in these parameters, then the method is said not to berobust.

Obviously, robust is better than not, and the analyst should strive todemonstrate that such is the case in validating a method for future usage. There islittle use in promoting or promulgating a method in the literature that has neverbeen shown robust, for one then never knows how the method will perform in thehands of other analysts. Robustness is very different from ruggedness orprecision, for it really describes how a given method performs when there maybe slight, unintentional changes in the operational parameters within a day orfrom day-to-day, analyst-to-analyst, laboratory-to-laboratory, and instrument-to-instrument.

Finally, ICH introduces something termed system suitability, which isreally used after the method has been fully validated, when the validated methodis being routinely used to actually analyze real samples25 . A system suitabilitysample is run any day that real samples are being analyzed, always before andalways after the actual batch of samples, often within that run of batches, in orderto demonstrate that the instrumental system is performing properly. It is used toshow that the HPLC column, for example, is yielding the desired peak shapes,plate counts, resolutions, and symmetry already demonstrated when the methodwas first validated. It is different from quality control samples, standard referencematerials, real samples, quality assurance samples, and is really used just to showthat the analytical instrumentation and overall system is performing properly

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

10/15

METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION 1075before real samples are then run. If the system suitability sample does not yieldchromatograms (injected several times, in replicate) as expected, then there isevery reason not to proceed with real samples until the problem(s) is defined andcorrected. System suitability samples are run to ensure the proper operation ofthe instrumental system itself, not necessarily the entire method including samplepreparation, and thus such a sample does not constitute a real sample as much asa made-up, make-believe, partial sample (usually without the entire samplematrix present).

We have now defined those USP method validation parameters that anyFDA filing must meet in order to pass muster and avoid rejection of theapplication. There is more to regulatory method validation than just the above,and the reader is urged to approach more intense books and review articles thatdiscuss this topic in much greater depth. However, since this mini-review isreally aimed at the academic researcher/analyst and their approaches to methodvalidation, we need to move forward.

What is Required Today of Academics Submitting New Analytical Methodsto Journals for Eventual Publication?

How much, then, must the non-regulatory analyst include in theirpublications on a new or improved analytical method, in order to have theirmethod considered validated? In the past, this has varied from journal-to-journal,from reviewer-to-reviewer, and from editor-to-editor. There are no firm (stated)requirements in writing. Some authors and reviewers ask for less, others formore, and some for none. Our opinions here are just that, opinions, they are notgrounded in accepted facts or regulatory requirements, and they may change inthe future. However, it seems to us that there are some basic requirements, evenfor academic analytical papers that describe new, improved, better, validatedmethods of analysis.

It is necessary to demonstrate the ability to fully resolve the analyte peakof interest from other compounds present in a real sample. It is necessary to

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

11/15

1076 KRULL AND SWARTZdemonstrate that peak is pure, homogeneous, and the correct analyte (specificity).It is necessary to demonstrate the precision of the overall method and how smallchanges in its operational parameters may affect the final results, as above. It isalso necessary to demonstrate acceptable (

-

8/7/2019 validation book

12/15

METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION 1077Why indeed? The reason is really quite simple- these things are not beingrequired by the reviewers, editors, and journal owners or publishers. The reasonthat pharmaceutical analysts do perform such involved method validations is alsoquite simple- it is required by FDA in order to get a drug approved and remain inbusiness. Academics will do what is required from a purely scientific viewpointor perspective for publication, but if something, such as robustness, is not askedor expected by the journal, then it is much easier to just avoid so doing.

It has been argued that journals do not have the space needed to includefull validation results, and that most readers would not read that data if it wereincluded. Most readers may be much more interested in the science described,rather than in any method validation to demonstrate that the science really doeswork with real samples. However, to satisfy both camps, it would always bepossible to include the complete validation results via a website version of thepaper, in a supplemental section of the journal available on-line or by writing, orfrom the authors on request. The fact of the matter is that the science ofanalytical chemistry will progress when any and all new methods of analysis aredemonstrated valid at the time of first publication, with real samples, using someor all of the guidelines being suggested above. Otherwise, the reader will neverknow for certain that the method can indeed be taken from the literature anddirectly utilized.

Glossary and List of AbbreviationsHPLC = high performance liquid chromatographyHPC E = high performance capillary electrophoresisICH = International Conference on HarmonizationIND = investigational new drugMS = mass spectrometryNDA = new drug applicationLOD = limit of detectionLO Q = limit of quantitationUSP = United States Pharmacopeia

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

13/15

1078 KRULL AND SWARTZLIST OF REFEREN CES

1. M.E. Swartz and I.S. Krull. Analytical Method Development andValidation, Marcel D ekker, Inc., New York, 1997.2. L.R. Snyder, J.J. Kirkland and J.L. Glajch. Practical HPLC Method

Development, Second Edition, Wiley-Intcrscience, NY, 1997.3. T.D. Wilson, Liquid chromatographic methods validation for

pharmaceutical products. J. Phann. Biomed. Anal., 8(5), 389 (1990).4. H.T. Karnes and C. March. Calibration and validation of linearity inchromatographic biopharmaceutical analysis. J. Phann. Biomed. Anal.,

9(10-12), 911(1991).5. H.T. Kam es, G. Shiu, and V.P. Shah. Validation of bioanalytical m ethods.

Pharm. Research, 8(4), 421 (1991).6. E.L. Inman, J.K. Frischmann, P.J. Jimenez, G.D. Winkel, M.L. Persinger,

and B.S. Rutherford. General method validation guidelines forpharmaceutical samples. J. Chrom. Sci., 25, 252 (1987).

7. G.P. Carr and J.C. Wahlichs. A practical approach to method validation inpharmaceutical analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal., 8(8-12), 613 (1990).

8. A.R. Buick, M.V. Doig, S.C. Jeal, G.S. Land, and R.D. McD owall.Method validation in the bioanalytical laboratory. J. Pharm. Biomed.Anal., 8(8-12), 629 (1990).

9. I.S. Krull, J.R. Mazzeo, and C M . Selavka. A rationale for analyticalmethodology development. Biomed. Chromatogr., guest editorial, 6, 259(1992).

10. M.E. Swartz and I.S. Krull. Validation of chromatographic methods.Pharmaceutical Technology M agazine, 104 (March, 1998).

11. B.R. Thomas and S. Ghodbane. Evaluation of a mixed micellarelectrokinetic capillary electrophoresis method for validatedpharmaceutical quality control. J. Liquid Chromatogr., 16, 1983 (1993).

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

14/15

METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION 107912. Capillary Electrophoresis Guidebook, Principles, Operations, and

Applications, Edited by K.D. Altria, Methods in Molecular Biology,Volume 52, Humana Press, Clifton, NJ, 1996.13. M. Swartz, J. Mazzeo, E. Grover, and P. Brown. Validation ofenantiomeric separations by micellar electrokinetic capillarychromatography using synthetic chiral surfactants. J. Chromatogr., A,735, 303 (1996).

14. Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications of Liquid Chromatography,Ed. by C M . R iley, W.J. Lough, and I.W. W ainer, Pergamon Press,London, 1994.

15. Development and Validation of Analytical Me thods, Edited by C M . R ileyand T.W. Rosanske, Pergamon Press, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam,Holland, 1996.

16. I.S. Krull, M. Swartz, and C. Gendreau. Regulations for chemists in thedrug and biotech industries. Today's Chemist at Work, an ACSPublication, 26 (February, 1997).

17. D.A. Skoog and J.J. Leary, Principles of Instrumental Analysis, FourthEdition, Saunders College Publishing, 1992, Chapter 26.

18. S.E. Manahan, Quantitative Chemical Analysis, Brooks/Cole PublishingCompany, Monterey, CA, 1986.

19. R. de Levie, Principles of Quantitative Chemical Analysis, McGraw-Hill,New York, 1997.

20. A.L. Day, Jr. and A.L. Underwood, Quantitative Analysis, Fifth Edition,Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986.

21. J.C. Miller and J.N. Miller. Statistics for Analytical Chemistry, EllisHorwood, Limited, Chichester, UK, 1986.

22. Handbook for Instrumental Techniques for Analytical Chemistry, Editedby F. Settle, Prentice Hall, PTR, Upper Saddle R iver, NJ, 1997.

23. I.S. Krull and M.E. Swartz. Validation Viewpoint: Determining limits ofdetection and quantitation. LC/GC Magazine, 16(10), 922 (1998).

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

-

8/7/2019 validation book

15/15

1080 KRULL AND SWARTZ24. I.S. Krull and M.E. Swartz. Validation Viewpoint: Quantitation in method

validation. LC/GC Magazine, 16(12), 1084(1998).25. I.S. Krull and M.E. Swartz. Validation Viewpoint: System suitabilitysamples- what they are, why they are, and what they should do? LC/GC

Magazine, in press (January, 1999).

Received: January 15,1999Accepted: January 25, 1999

Downloaded

By:[UNAMDireccionGeneraldeBibliotecas]At:18:128August2008

![8.6 Bayesian neural networks (BNN) [Book, Sect. 6.7] capability, …william/EOSC510/Ch8/Ch8b.pdf · 2019-12-18 · 8.6 Bayesian neural networks (BNN) [Book, Sect. 6.7] While cross-validation](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/5ed413138d46b66d22636923/86-bayesian-neural-networks-bnn-book-sect-67-capability-williameosc510ch8ch8bpdf.jpg)