U.S. and Whom? Structures and Communities of International ... · from peripheral countries write...

Transcript of U.S. and Whom? Structures and Communities of International ... · from peripheral countries write...

U.S. and Whom? Structures and Communities

of International Economic Research

Raphael H. Heiberger

University of Bremen, [email protected]

Jan R. Riebling

University of Bamberg, [email protected]

Abstract

Most studies concerned with empirical social networks are conducted on the level of individuals. The

interaction of scientists is an especially popular research area, with the growing importance of

international collaboration as a common sense result. To analyze patterns of cooperation across

nations, this paper investigates the structure and evolution of cross-country co-authorships for the

field of economics from 1985 to 2011. For a long time economic research has been strongly US

centered, while influencing real-world politics all over the globe. We investigate the impact of the

general trend of increasing international collaboration on the hegemonic structures in the “global

department of economics.” A dynamic map of economic research is derived and reveals communities

that are hierarchical and structured along the lines of external social forces, i.e. historical and political

dimensions. Based on these findings, we discuss the influence of the core-periphery structure on the

production of economic knowledge and the dissemination of new ideas.

Keywords

Scientific collaboration, economics, dynamic networks, network visualization

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research (01UZ1001).

Page 2 of 12

Introduction

In this article, we treat countries as primary research subjects in order to investigate the increasing

global connection of social life. The process of globalization has not only left its trace in altering trade

patterns or extending travel destinations, also the way scientists work has changed. In the last 30

years, international collaboration has led to stronger relations between researchers in different

countries and a worldwide scientific network has emerged that includes the former Eastern Bloc

nations (Doré et al. 1996; Georghiou 1998; Glänzel 2001; Glänzel and Schubert 2005; Persson,

Glänzel, and Danell 2004). Yet, international scientific collaboration is still dominated by a core of

western countries with the US at its center (Leydesdorff and Wagner 2008; Wagner 2005). The work

of Zitt and colleagues (2000) also reveals that patterns of collaboration across countries follow

historical and political partnerships. We expand on these insights in two ways: First, we go beyond the

dyadic perspective and take a closer look at the broader relationship structures in which the

collaborations are embedded in terms of networks and communities. This allows us to specify the

political influence spheres which we believe to be decisive factors. Secondly, we look at the underlying

dynamics of international scientific relationships. Since the world changed drastically since the 1980s,

it is reasonable to assume that the network structure would adjust.

In general, the study of scientific collaboration is facilitated by the richness of available data and

provides insights about the creation of ideas and the underlying structure of scientific discoveries,

which makes it an issue that grows more and more important in advanced economies (Kronegger,

Ferligoj, and Doreian 2011; Light and Moody 2011). Despite the widely undoubted impact that

scientific research has on modern, innovation-based societies and the availability of appropriate data,

the global relationships within the discipline of economics have not yet been examined. At the latest,

recent financial turmoil has strikingly shown that the paradigmatic dominance of the neoclassical

approach needs to be reformed (Hodgson 2009; Keen 2011). This orthodox way of doing economics is

linked to the dominant role of the US within the field. For instance, in a comprehensive (and for us,

also eponymously inspiring) study Jishnu Das et al. (2009) identified a far higher likelihood of being

published in the five most important journals if the paper`s topic is US-related. The same pattern of

centralization exists on an institutional level. Only a handful of American universities produce the

most visible publications (Coupé 2003; Kalaitzidakis, Mamuneas, and Stengos 2003; Kim, Morse, and

Zingales 2006). These elite institutions are highly connected with a core network of economic

journals, which is also very consistent over time (Liner 2003; Stigler, Stigler, and Friedland 1995).

Hodgson and Rothman (1999) analyze the institutional background of editors and authors of those

economic journals and find that around 80 percent of authors and editors alike are affiliated to US

institutions. On a personal level, Goyal et al. (2006) discover a growing large component in economic

research collaboration that is due to few interlinking (US based) star economists.

But is a giant monolith dominating the entire discipline or is the global situation more complex?

Questions of international embeddedness and change within the economic research community seem

not only important for the sociology of knowledge, but also for practitioners since economics has

always played an important role in the legitimation and application of different national policies,

ideologies and institutions (e.g. Fourcade-Gourinchas 2001; Hall 1989; Schumpeter 2013). For a long

time, economics has been strongly intertwined with politics in many institutions (e.g. IMF, World

Bank, Central Banks, stock regulations like the SEC), and ideas developed in economics often

influence national and international economic structures and laws. Or as John Maynard Keynes

(1973:383) noted: “The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and

when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood.”

Methodologically, the paper applies techniques of the social network analysis approach. With the

global network of collaborating economists we concentrate on the relationships between countries,

which offer an alternative of the investigation of national shares of publication or citations

(Leydesdorff et al. 2013). These collaboration networks between scientists can be seen as a “new

Page 3 of 12

invisible college” (Crane 1972; Wagner 2008), spanning the globe and connecting researchers from

different countries. To identify alterations in the composition of this “global department of

economics,” we first look at the expansion of the field in general and investigate individual positions of

countries therein. Subsequently, we integrate these singular developments in the evolution of the

whole network, revealing a core-periphery structure and communities with particularly dense

relationships that run along historical and political boundaries.

Data and Methodology

We collected a data set that represents virtually the entire economic field.1 The general selection based

on the 100 most important economic journals identified by Das et al. (2009), from which 87 were

available in Thomson Reuters Web of Science, with missing values biased in regard to B- and C-

journals. The raw sample contains about 150,000 articles, spanning from 1985 to 2011. Circa 45,000

(~30%) of these have more than one author. Our focus in this paper, however, lies on the level of

international collaboration, hence, only publications with two or more authors from different

countries are considered. The country affiliation depends on the institutions of the authors. In the

case that two or more institutions are provided per author, only the first (“home”) institution is taken.

Thus, around 5,500 (~3.7%) from the initial documents were internationally coauthored and

remained in the final data set.

Each country pair was used as an edge in a multigraph, that is, a graph with parallel lines between

nodes, where each line represents one instance of cross-country collaboration. For example,

economists in the US and Canada have cooperated 1376 times in the observed period, corresponding

to the same number of edges between both nodes. This raw number of co-authorships between two

nations is normalized as an indicator of international collaboration strength (Boyack, Klavans, and

Börner 2005; Glänzel 2001):

𝑤𝑖𝑗 = ∑ 𝑝𝑖𝑗

√∑ 𝑑𝑖 ∑ 𝑑𝑗 (1).

The weight 𝑤𝑖𝑗 between country i and j consists of the sum of joint publications (𝑝𝑖𝑗), divided by the

geometric mean of total publications of each country (degrees 𝑑𝑖 and 𝑑𝑗, respectively). The

normalization is necessary in order to reveal latent structures that could otherwise be overlooked due

to stars in the network (e.g. the US) and their mere size of research output (Leydesdorff 2007a,

2007b; Leydesdorff and Wagner 2008).

In general, the science system is based on networks of scientists who write paper together and know

one another (Newman 2001). It has been suggested that out of such interactions of single actors arises

a complex system with specific topological and dynamical principles (Barabási et al. 2002). Under

these assumptions, we would expect the network to exhibit a high tendency towards homophilic

relations in regard to the prestige of scientists and their “attractiveness” to work with colleagues from

different countries. A deviation from this pattern on the other hand would point to the influence of

external constraints, most likely in the form of political, linguistic and historical boundaries between

nation states. If our assumptions are correct and political and cultural influence spheres are central to

the formation of scientific collaboration on a global level, we would expect to see a network marked by

heterophilic relationships and following a shifting political landscape.

In order to investigate this system more closely, we apply several network analytical tools, roughly

divided into positional measures and community detection algorithms. To structure the positional

metrics, we distinguish between medial and radial measures according to Borgatti and Everett (2006).

1 Our data does only contain journal publications, but no other media, especially no books. Yet, the bias should be sufficiently low since economics is a discipline in which articles are the major form of communication (Whitley 2000).

Page 4 of 12

Medial measures are used to determine the intermediate position of nodes with regard to other nodes.

We employ betweenness centrality (Brandes 2001; Freeman 1979) as a measure for the mediator

quality of an actor, i.e. the number of shortest paths 𝑔𝑖𝑘𝑗 from node i to node j through the

intermediary k, divided by 𝑔𝑖𝑗, what denotes the number of geodesic (i,j)-paths. Thus, the betweenness

centrality is defined as:

𝐵𝑘 = ∑𝑔𝑖𝑘𝑗

𝑔𝑖𝑗𝑖,𝑗 (2).

It indicates the control that a node exerts over the communication of others, and can be interpreted as

a measure for the most influential nodes in a network, who control the flow of information as

gatekeepers. More specifically, it gives the probability that a country k is involved into any

communication between i and j, serving as a bridge between both.

The main aim of radial measures is to specify a node´s position in terms of how many connections are

emanating from it. This is equivalent to degree of node i (𝑑𝑖) in (1). To control for the size of the

network this number is normalized by the maximum number of connections possible (N-1). Thus,

Freeman´s (1979) degree centrality gives us the fraction of realized connections for a certain node.

Complementary to individual centrality scores, we investigate the structure of the whole network in

terms of hierarchy. One of the most common techniques to do this is to calculate the centralization of

connections (Freeman 1979). In our case, the degree centralization measures the concentration of

collaboration, i.e. the strength of deviation between high and low degree values, with 𝑑∗ as the highest

degree of any node in the network. Formally, this can be written as:

𝐶𝐷 = ∑ [𝑑∗−𝑑𝑖]𝑁

𝑖=1

(𝑁−1)(𝑁−2) (3).

To measure not only the hierarchy of countries but to learn more about which country is connected to

what others, we calculate the assortativity of nodes to describe the degree of similarity of coauthors in

terms of their own connections. Technically, this is the Pearson-correlation between the edges

(Newman 2003). For instance, social networks are known to be often assortative by race, gender or

language. In our case, a high score of assortative mixing by degree means that countries with many

collaborations would be linked to other well connected nations, or, the other way round, economists

from peripheral countries write paper rather with their like. Accordingly, a low assortativity coefficient

indicates a disassortative network, i.e. countries prefer connections with others that are unlike them

in terms of relationships.

In addition to hierarchical properties, our paper tries to detect communities within the network.

Those groups consists of countries in which connections are unusually dense and have only loose

connections to other subgroups (Girvan and Newman 2002). To detect them, we applied the

modularity approach of Clauset et al. (2004) by using the algorithm of Blondel et al. (2008). This

method is not only computationally efficient but also provides valid modularity maxima (Lancichinetti

and Fortunato 2009). Complementary to the partition, the modularity score serves as an indicator for

the compartmentalization (modularization) of a network (Newman 2004, 2006). For weighted

networks it is defined as:

𝑄 = 1

2𝑚∑ [𝑤𝑖𝑗 −

𝑑𝑖𝑑𝑗

2𝑚] 𝑓(𝑐𝑖 , 𝑐𝑗)𝑖,𝑗 , (4).

where 𝑚 = 1

2∑ 𝑤𝑖𝑗𝑖𝑗 , and 𝑐𝑖 is the community of node i and j, respectively. The function is 1 if 𝑐𝑖 = 𝑐𝑗

and 0 otherwise. It calculates the difference between realized and expected connections between two

nodes. The modularity score 𝑄 rises as more possible connections are realized within a given

Page 5 of 12

community in relation to connections to nodes in other communities. Thus, 𝑄 measures the division

of a network in modules and the identifiability of these groups in relation to each other.

The calculation of the centrality scores and other network measures was done using the “NetworkX”

module for Python 2.7 (Hagberg, Schult and Swart 2008). For the community detection via the

“Louvain method” described above, we used the “community”-package created by Thomas Aynaud.2

The figures were also created in Python, using the excellent “plotly” module for interactive graphics.

Growth and Hierarchy

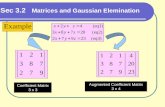

As in other scientific fields, the frequency of all coauthored publications is strongly rising in

economics during the last 25 years, indicating a more differentiated division of labor for more

specialized tasks. The dynamic of international collaborations does not match this exponential growth

(upper and middle box in Figure 1). Also, the number of international coauthored documents is quite

small compared to science in general (around 20% reported by Leydesdorff and Wagner 2008).

However, the share of economists that work together across national borders increased considerably.

In 1985, only 1 out of 100 papers was produced by economists in different countries, in the most

recent years it was nearly every tenth paper. Especially in the last few years this development picked

up some steam.

The different patterns of growth reinforce the idea that there are mechanisms at work which influence

and hinder scientific collaboration across countries. This can partly be attributed to language barriers

(Hoekman et al. 2013; Marshakova-Shaikevich 2006). Yet with the increasing dominance of the

English language as lingua franca of science this explanation seems not sufficient. Instead we argue

that while language may play a role in the facilitation of cross-country collaboration, geo-political

influence spheres are a more important factor. If we look at the number of countries involved in cross-

country collaboration (lower box in Figure 1), we see that a first wave of “new” countries came into

play after the fall of the Iron Curtain. A geopolitical process started at this point in time, which led to

the accelerating trend of rising international exchange of persons, goods and cultural artifacts and is

commonly referred to as globalization. This development is closely matched by all three growth

patterns of scientific collaborations in Figure 1. After a rather stabile time around the millennium, the

number grew significantly in the most recent years and indicates a strong, ongoing trend.

Figure 1: Growth of International Economic Research Collaboration

Despite the increased cross-border collaboration around the world, the paramount actor on the

international level was, and still is, the USA. The degree centrality in the late 1980s and 1990s was

especially high, with values above 0.8 (Figure 2). Although it is slightly declining since then, the USA

is still the most central player in economic collaboration. Beyond the rather consistent role of the US,

some changes exist in the structure of economic collaboration. The big European countries expanded

their international collaboration efforts during the 1990s, particularly England and Germany. As a

consequence, the relative distance between the US and those countries decreases drastically in the

years after 2000. Hence, even though there is no change at the top, all major Western countries

increased their efforts to collaborate with colleagues from other nations, which make the centrality of

the US less “star network like.”

2 perso.crans.org/aynaud/communities

Page 6 of 12

One further issue of global scientific debate is the role of China in the last decade or so. Some

prominent observers see Chinese researchers as number one challenger of the US hegemon (Mirowski

2010). Other than in economic or political affairs, China has not yet achieved a dominant role in

economic research. It is only marginally improving in terms of collaboration, indicating—at least for

economics—that the “overtaking of Chinese scientists” (e.g. Shukman 2011), copiously discussed in

popular media, is not yet conceivable.

Figure 2: Degree Centrality for Selected Countries

Additionally, the betweenness centralities in Figure 3 indicate that the ability of Chinese economists to

mediate between scientists of different countries hardly exists. In contrast, US economists still play

the most important part in connecting researchers worldwide, with the major European countries

increasing their mediator positions only slightly, if at all. However, there is one exception—England.

Together with the clearly decreasing ability of the US to mediate between researchers of different

countries in the new millennium, it seems that the dominance is crumbling, as least relatively. In

combination with the overall growth of the field, this implies that fewer of the “new” participants in

economic research are connected via US economists. Thus, this development indicates that nowadays

exist “supplementary options” to connect economists in peripheral countries to the core, a process

that will also be clearly visible in Figure 5 and the movie. However, no other “beacon” of similar

propensity has, as of yet, emerged that would mediate between peripheral countries and the core,

making US economists still the most important actors in respect of mediator qualities as well as

overall collaborations. Therefore, the hierarchical structure in economic collaboration seems rather

untouched, even in the years after 1990, with the Iron Curtain falling and former communist states

being integrated in the global science community.

Figure 3: Betweenness Centrality for Selected Countries

Structure and Communities

The notion of relative stability in terms of the individual positions of countries in the global

economists´ collaboration network is underlined in Figure 4. All three structural measures are rather

steady over time. Again, the heavily discussed expansion of the scientific community has only limited

effects on the overall structure of the field. The modularity of economic collaboration is rather low,

compared to other social networks (Newman 2006). One possible reason is the generally unified core

of economic research that lies within the neoclassical approach (Reay 2012). The homo oeconomicus

and the nearly exclusive use of quantitative methods are widely accepted theoretical and

methodological foundations of the discipline, making it rather easy to collaborate globally. We suggest

this would be different in a theoretical and methodological diverse discipline, e.g. in sociology (Abbott

2000; Moody 2004).

Figure 4: Modularity, Degree Centralization and Assortivity

Thus, the entire structure shows a relative stability over the last three decades and the, by far, most

important collaboration partner is the US. However, the permanently negative assortativity in Figure

4 represents a heterophile degree distribution. This tendency is very uncommon for social networks

(Newman 2003). As in most social networks, we would expect a network generated solely by the

preferences of scientists to be assortative. Instead, there is a permanent negative assortativity. We

consider this as further evidence for the influence of external factors (i.e. political and cultural

influence spheres) driving the development of cross-country collaboration.

Moreover, the development of the correlation by degree shows a slump during the integration of the

former Eastern bloc countries, and rises slowly since then. The relatively abrupt global opening

seemed to cause even more disassortative countries to work together. After this phase of integration

the negative mixing is gradually decreasing, but still, mostly unequal partners collaborate together.

Page 7 of 12

As we will see, most communities have some sort of “beacon” or broker that is distinguished by the

amount of degrees from the other community members.

To examine the evolution of the economic field in terms of international collaborations in greater

detail, we created a short movie in Gephi (gephi.github.io). Therein, the displayed communities are

based on all international collaborations between 1985 and 2011. This step is necessary since

community detection is still a rather sensible issue in social network analysis (Fortunato 2010). We

experienced such problems using Gephi’s modularity algorithm, where the number of communities

changed—under the same settings—with every running. Therefore we used the Python-algorithm by

Thomas Aynaud mentioned above, which provides steady results for both numbers and members of

communities. For a better overview, the whole network with its subsequent partitions is shown in

Figure 5.

Figure 5: Map of Economic Research Collaboration between 1985 and 2011

The nodes of the communities are turquoise (“Europe” 32.4% of all edges), red (“Pacific,” 28.9%), green

(“Emerging,” 25.5), blue (“East Mediterranean,” 4.8%), yellow (“Post-Communist,” 4.8%), purple

(“Caribbean,” 2.1%) and pale purple (“Baltic,” 1.4%). The edges inside a community are drawn in the

same color as the community and the positions are defined by the Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm.

The community detection reveals two major groups dividing the center, another large and two smaller

cliques sharing the periphery and two very small communities. The largest group in terms of relations

is the European cluster, with the key members Germany, Netherlands and, somewhat surprisingly,

England. It seems that the scientific connection to the continent is in sum more important for English

economists than for their US colleagues. However, with Argentina and Brazil some former European

Page 8 of 12

colonies in Latin America are also part of the community. The countries arranged around the US

spread mostly along the Pacific, from Canada through Chile and Australia to China and Japan. It

forms a similar large group (due to the US) and includes mostly developed nations outside Europe like

Australia or Japan. Especially the tight center of the network is divided by these two clusters. In

contrast, the periphery is mostly defined by developing countries spreading around the center. As in

real-world economic deprivation, these countries are located in the Southern hemisphere, in Africa,

Middle and South America. Mexico is the “beacon” of this community and their most influential

member. Interestingly, Brazil and Argentina hold stronger relations to Europe, while Chile is more

oriented towards the US centered community than to their Latin American neighbors. Only relatively

deprived countries like Bolivia, Uruguay or Peru belong to the “Emerging” community. Also in the

periphery we find the “Post-Communist” community, consisting of former members of the USSR (e.g.

Russia or the Ukraine) and a cluster of mostly Mediterranean countries. Finally, there are two very

small clusters of countries in the Caribbean and the Baltic.

Corresponding with the modest modularity scores over time, the network is only slightly

compartmentalized, with the great majority of collaboration going on within and between the US and

European based communities. Inside each group relatively diverse countries assemble in regard to

their output in economics. The USA in the Pacific community, Mexico as leading Emerging nation or

England and Germany in the European community. As the assortativity scores over time suggested,

node relations correlate negatively with each other and countries mix mostly with others unlike them.

In addition, the communities reflect roughly the topology of international politics and economic

differences. Relatively rich and developed countries gather in the Pacific and European communities.

The global south with mostly poor countries, is also relatively peripheral in economic research and is

only rudimentary linked to the other communities. Thus, besides distinct traditions of economics that

shape the collaboration structure across countries, the world map reveals clustering tendencies

between scientifically diverse countries, that are, however, historically, politically and/or economically

related.

Utilizing the movie to investigate the network evolution, we can observe how the participation within

the described communities changes over time. In the beginning there are only few, mostly Western

countries. The first wave of expansion happens after the fall of the Berlin Wall, as is also shown

quantitatively in Figure 1. In the aftermath of the crush of the USSR, the first Eastern European

countries appear in the network. During the 1990s this group gets bigger (~ 0:08s), as does the whole

periphery. Most of the new participants stem from the global South. Some of them are mostly

connected to other peripheral countries (“green”), some to the US centered Pacific cluster. But only

very few—actually only Argentina and Brazil (ignoring very small countries that just pop up briefly)—

develop a strong relationship to the European field of economics. The US centered cluster, in contrast,

becomes much more diversified during the same period. In the new millennium the expansion visibly

slows down (around 0:17s), with the world´s larger countries already taking part in global economic

research. Only for the last few years (and seconds) we see a further growth in the periphery.

This dynamic emphasizes the hierarchical properties of the network. Furthermore, the network

evolution makes the changes in the political landscape and their influence on scientific collaboration

patterns even more visible. The network starts out as dominated by a strong center which is formed

mostly by the US and large European countries. Until the 1990s this structure grows mostly by

reinforcing the center, or in other words, the central members are intensifying their relations. The

drastic political changes following the fall of the Iron Curtain are reflected in the network by the

connection of former USSR member states in the periphery and the first wave of global expansion. At

the end of the 1990s the European and Pacific clusters become more independent of each other and

include different members in their respective community (i.e. the core). This process is mainly

responsible for the “bifurcation” of the center. It is important to note that the network still retains its

strong hierarchy and grows by adding “levels” in terms of peripheral nodes to the existing topology.

Page 9 of 12

The “new” arrivals seem thereby oriented along sociocultural ties, for example, in terms of Metropole

powers and their colonies (European community) or shared historical experiences (Post-Communist

countries). Thus, countries who join the network are not just integrated within the main core but are

rather located as another layer around the (bifurcated) center.

Conclusion

If one considers each scientific publication as an idea and the authors as their conveyors, then the

global exchange of ideas has drastically increased in the last 25 years. In our paper we have studied

the international collaboration network of economists, to learn more about the way researchers

interact across borders and the distribution of the “global department of economics.” Especially in

times of real-world economic slumps it seems important to take a closer look at the structures and

mechanisms behind the production of knowledge in economics.

The international network of economists follows a clear core-periphery organization, with the US at its

center. Like in other disciplines, collaboration in economics expanded heavily after the fall of the Iron

Curtain. During this process, Europe intensified the relations with “new arrivals,” i.e. countries of the

periphery accessed the field with co-authorships following established historical and political borders.

Due to a history of exploration and colonization, it seems that traditional connections helped

European countries to rather join “their” cluster than the US dominated group. Thus, economists are

more likely to work together across countries which are longstanding allies. Community detection

revealed mainly clusters between culturally and historically connected nations, e.g. between Post-

Communist countries in Eastern Europe. Also, the US has especially intense relations with their

political allies from India, Chile and Turkey, but only very few collaborations exist with the rest of

(rather US skeptical) Latin America. However, although the network expanded heavily in the last

three decades and economic publications are more globalized, the large majority of international

collaborations still take place between the “usual suspects,” i.e. industrialized western countries.

The existence of a stable core-periphery structure in the global network has two, rather different,

implications for the future: Optimistically, economists from peripheral countries can collaborate more

often with members of the core groups. By doing so, their—supposedly less paradigmatic—ideas could

be distributed relatively easy to other central actors (and therefore to important institutions and

journals). As a consequence, a larger variety of economic knowledge would be possible, e.g. about the

modes of production in developing countries, different ways of consumption or ecological problems of

the global South. Secondly, and more pessimistic, the cohesive and persistent core could also

monopolize knowledge and collaboration resources. The great resilience of the hierarchy and

community structure points to processes which reproduce the established structure. In this case, the

opportunities for developing countries to join the “new invisible college” proposed by Wagner (2008)

seem to be a long way off. This could very well be a future obstacle to the free exchange of ideas in

economics, which is science greatest resource and a fundamental driver of innovations.

As has been shown for the (rather homogeneous) countries of the EU (Hoekman et al. 2013), political

incentives can help to establish relations between dissimilar countries. In order to facilitate and

enhance the inclusion of peripheral countries in economic research, hence, worldwide incentives for

joint research efforts could be a useful approach (e.g. provided by financial institutions like the World

Bank or IMF). From a network perspective, this should lead to an increasing flow of ideas around the

globe. For this purpose, the results of our paper would provide rich material about the dynamics and

structural properties of the global community of economists.

Page 10 of 12

References

Abbott, Andrew. 2000. “Reflections on the Future of Sociology.” Contemporary Sociology 29: 296–

300.

Barabási, Albert, H. Jeong, Z. Neda, E. Ravasz, A. Schubert and T. Vicsek. 2002. “Evolution of the

Social Network of Scientific Collaborations.” Physica A 311: 590–614.

Blondel, Vincent D., Jean-Loup Guillaume, Renaud Lambiotte, and Etienne Lefebvre. 2008. “Fast

Unfolding of Communities in Large Networks.” Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and

Experiment 10: P10008.

Borgatti, Stephen P., and Martin G. Everett. 2006. “A Graph-Theoretic Perspective on Centrality.”

Social networks 28: 466–84.

Boyack, Kevin W., Richard Klavans, and Katy Börner. 2005. “Mapping the Backbone of Science.”

Scientometrics 64: 351–74.

Brandes, Ulrik. 2001. “A Faster Algorithm for Betweenness Centrality.” Journal of Mathematical

Sociology 25: 163–77.

Clauset, A., M. E. Newman, and C. Moore. 2004. “Finding Community Structure in Very Large

Networks.” Physical Review E 70: 066111.

Coupé, Tom. 2003. “Revealed Performances: Worldwide Rankings of Economists and Economics

Departments, 19990-2000.” Journal of the European Economic Association 1: 1309–45.

Crane, Diana. 1972. Invisible Colleges: Diffusion of Knowledge in Scientific Communities. Chicago:

University Of Chicago Press.

Das, Jishnu, Quy-Toan Do, Karen Shaines, and Sowmya Srikant. 2013. “U.S. and Them: The

Geography of Academic Research.” Journal of Development Economics 105: 112–30.

Doré, Jean-Christophe et al. 1996. “Correspondence Factor Analysis of the Publication Patterns of 48

Countries over the Period 1981–1992.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 47:

588–602.

Fortunato, Santo. 2010. “Community Detection in Graphs.” Physics Reports 486: 75–174.

Fourcade, Marion. 2004. Economists and Societies: Discipline and Profession in the United States,

Britain, and France, 1890s to 1990s. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fourcade-Gourinchas, Marion. 2001. “Politics, Institutional Structures, and the Rise of Economics: A

Comparative Study.” Theory and Society 30: 397–447.

Freeman, L. 1979. “Centrality in Social Networks: Conceptual Clarification.” Social Networks 1: 215–

39.

Georghiou, Luke. 1998. “Global Cooperation in Research.” Research Policy 27: 611–26.

Girvan, Michelle, and Mark EJ Newman. 2002. “Community Structure in Social and Biological

Networks.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99: 7821–26.

Page 11 of 12

Glänzel, Wolfgang. 2001. “National Characteristics in International Scientific Co-Authorship

Relations.” Scientometrics 51: 69–115.

Glänzel, Wolfgang, and András Schubert. 2005. “Analysing Scientific Networks Through Co-

Authorship.” Pp. 257–76 in Handbook of Quantitative Science and Technology Research, edited by

Henk F. Moed, Wolfgang Glänzel, and Ulrich Schmoch. Springer.

Goyal, Sanjeev, Marco J. van der Leij and José Luis Moraga-González. 2006. “Economics: An

Emerging Small World.” Journal of Political Economy 114: 403–12.

Hagberg, Aric A., Daniel A. Schult and Pieter J. Swart, 2008. “NetworkX.” Pp. 11–15 in Proceedings of

the 7th Python in Science Conference (SciPy2008), edited by Gäel Varoquaux, Travis Vaught, and

Jarrod Millman. Pasadena, CA USA.

Hall, Peter. 1989. The Political Power of Economic Ideas: Keynesianism Across Nations. Princeton:

Princeton University Press.

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. 2009. “The Great Crash of 2008 and the Reform of Economics.” Cambridge

Journal of Economics 33: 1205–21.

Hodgson, Geoffrey M., and Harry Rothman. 1999. “The Editors and Authors of Economics Journals: A

Case of Institutional Oligopoly?” The Economic Journal 109: 165–86.

Hoekman, Jarno, Thomas Scherngell, Koen Frenken, and Robert Tijssen. 2013. “Acquisition of

European Research Funds and Its Effect on International Scientific Collaboration.” Journal of

Economic Geography 13, 1: 23–52.

Kalaitzidakis, Pantelis, Theofanis P. Mamuneas, and Thanasis Stengos. 2003. “Rankings of Academic

Journals and Institutions in Economics.” Journal of the European Economic Association 1: 1346–66.

Keen, S. 2011. “Debunking Macroeconomics.” Economic Analysis & Policy 41: 147–67.

Keynes, John Maynard. 1973. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. MacMillan-

St. Martin’s Press.

Kim, E. Han, Adair Morse, and Luigi Zingales. 2006. “What Has Mattered to Economics Since 1970.”

National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series No. 12526.

Lancichinetti, Andrea, and Santo Fortunato. 2009. “Community Detection Algorithms: A Comparative

Analysis.” Physical Review E 80: 056117.

Leydesdorff, L., and C. S. Wagner. 2008. “International Collaboration in Science and the Formation of

a Core Group.” Journal of Informetrics 2: 317–25.

Leydesdorff, Loet. 2007a. “Betweenness Centrality as an Indicator of the Interdisciplinarity of

Scientific Journals.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 58:

1303-19.

Leydesdorff, Loet. 2007b. “Should Co-Occurrence Data Be Normalized? A Rejoinder.” Journal of the

American Society for Information Science and Technology 58: 2411–13.

Leydesdorff, Loet, Caroline S. Wagner, Han-Woo Park, and Jonathan Adams. 2013. “International

Collaboration in Science: The Global Map and the Network.” El profesional de la información 22: 87–

95.

Page 12 of 12

Light, Ryan and James Moody. 2011. “Dynamic Building Blocks for Science: Comment on Kronegger,

Ferligoj, and Doreian.” Quality & Quantity 45: 1017–22.

Liner, Gaines H. 2003. “Core Journals in Economics.” Economic Inquiry 40: 138–45.

Marshakova-Shaikevich, Irina. 2006. “Scientific Collaboration of New 10 EU Countries in the Field of

Social Sciences.” Information Processing & Management 42: 1592–98.

Mirowski, Philip. 2010. “Bibliometrics and the Modern Commercial Regime.” European Journal of

Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie 51: 243–70.

Moody, James. 2004. “The Structure of a Social Science Collaboration Network: Disciplinary

Cohesion from 1963 to 1999.” American Sociological Review 69: 213–38.

Newman, M. E. 2001a. “Scientific Collaboration Networks. II. Shortest Paths, Weighted Networks,

and Centrality.” Physical Review E 64: 016132.

Newman, M. E. 2001b. “The Structure of Scientific Collaboration Networks.” Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences 98: 404.

Newman, M. E. 2003. “Mixing Patterns in Networks.” Physical Review E 67: 026126.

Newman, M. E. 2004. “Analysis of Weighted Networks.” Physical Review E 70: 056131.

Newman, M. E. 2006. “Modularity and Community Structure in Networks.” Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences 103: 8577–82.

Persson, Olle, Wolfgang Glänzel, and Rickard Danell. 2004. “Inflationary Bibliometric Values: The

Role of Scientific Collaboration and the Need for Relative Indicators in Evaluative Studies.”

Scientometrics 60: 421–32.

Reay, M. J. 2012. “The Flexible Unity of Economics.” American Journal of Sociology 118: 45–87.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. 2013. History of Economic Analysis. London: Routledge.

Shukman, David. 2011. “China ‘to Overtake US on Science in Two Years’.” BBC News (28 March 2011).

Stigler, George J., Stephen M. Stigler, and Claire Friedland. 1995. “The Journals of Economics.”

Journal of Political Economy 103: 331–59.

Wagner, Caroline S. 2005. “Six Case Studies of International Collaboration in Science.”

Scientometrics 62: 3–26.

Wagner, Caroline S. 2008. The New Invisible College: Science for Development. Washington:

Brookings Institution Press.

Whitley, Richard. 2000. The Intellectual and Social Organization of the Sciences. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Zitt, Michel, Elise Bassecoulard, and Yoshiko Okubo. 2000. “Shadows of the Past in International

Cooperation: Collaboration Profiles of the Top Five Producers of Science.” Scientometrics 47, 627–57.