PGP Rotor - Cincinnati sprinkler systems, Cincinnati Lighting

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI MEDICAL CENTER ENT Insights

Transcript of UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI MEDICAL CENTER ENT Insights

UCMedicalCenterENT.com

I N T H I S I S S U E

Technical Innovation in

Skull Base Surgery Program . . .p 2

New Connection Studied

Between Oropharyngeal Cancer

and HPV . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .p 4

New Surgical Skills Laboratory to

Provide Residents Critical Skills for

Real-Life Scenarios . . . . back cover

Advancing the Field We are excited to share with you

highlights of leading-edge procedures

and research taking place at the

University of Cincinnati Medical Center.

Stay informed as we feature new

techniques, breakthrough technologies,

and innovative approaches our team

of highly trained and experienced

otolaryngologists and otologists are

leading to advance the field.

WINTER 2016UCMedicalCenterENT.com

University of Cincinnati Medical Center ENT Insights

NON-PROFIT ORGUS POSTAGE

PAIDCINCINNATI OHPERMIT #1232

234 Goodman St.Cincinnati, OH 45219

p 2

ENT Insights

WINTER 2016

W I N T E R 2 0 1 6

ENT InsightsA Clinical, Academic and Research, Peer to Peer Publication

U N I V E R S I T Y O F C I N C I N N A T I M E D I C A L C E N T E R Technical Innovation in Skull Base Surgery Program

nerve, according to Samy. Less bone dust may also be created during procedures. One advantage of this greater degree of control can be seen in retrosigmoid vestibular schwannoma removal surgery, where reduced bone dust dispersion could possibly decrease the frequency of postoperative headache.1

Utilization of the ultrasonic bone aspiration has also been adapted for middle cranial fossa surgery

at UC Medical Center. One example where surgeons use this challenging technique is in acoustic neuromas, where preserving hearing function is especially difficult. The ultrasonic bone aspirator may allow for less hearing loss and better outcomes for patients.

“Along with innovation, education is critical,” says Samy. “Our surgical volume is high enough here that we are one of only 15 programs nationwide that offers a neurotology fellowship, reflecting our commitment to preparing the next generation of surgeons to be comfortable with delicate skull base surgical procedures and utilizing revolutionary technology.” The most important measure of success, however, as Samy is quick to note, is in improved patient outcomes.

Reference: 1. Weber JD, Samy RN, Nahata A, Zuccarello M, Pensak ML and Golub JS. Reduction of bone dust with ultrasonic bone aspiration: implications for retrosigmoid vestibular schwannoma removal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015 Jun;152(6):1102-7.

Neurotologist, UC Neuroscience Institute Program Director of the Neurotology Fellowship Associate Professor of Otolaryngology (513) [email protected]

Ravi N. Samy, MD, FACS

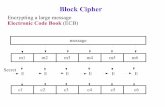

The Sonopet Ultrasonic Aspirator is a versatile system

for precise control of soft tissue while simultaneously allowing fine bone dissection in close proximity to delicate

structures. The console (shown left) is capable of running the handpiece(s)

(shown above) at multiple frequencies through a single connection port.

Images courtesy of Stryker.

Skull base surgeries are some of the most delicate procedures surgeons can perform, so every advantage is welcomed. “As skull base surgeons, we always have to adapt in order to push the frontier of medicine forward,” says Ravi N. Samy, MD, Director of the Neurotology Fellowship and Associate Professor of Otolaryngology, University of Cincinnati Medical Center. One cutting-edge technology that Samy uses often and has provided an edge in recent years is the ultrasonic bone aspirator, which utilizes both longitudinal and torsional motion to give surgeons precise control and allowing fine bone dissection in close proximity to delicate structures.

The ultrasonic bone aspirator now in use by UC Medical Center, known as Sonopet and manufactured by Stryker, allows users to independently control power, suction, and irrigation with one handpiece, and decreases the risk of damaging the facial

“As skull base surgeons, we always have to adapt in order to push the frontier of medicine forward.”

Exploring a Novel Method for Improving Facial Nerve Healing from Facial Nerve Injury

Facial nerve injuries result in significant functional deficits and cosmetic deformities. Better methods are still needed to improve facial nerve healing resulting from injuries.1 To further explore this clear need to improve facial nerve healing, a team at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center examined the use of magnesium filaments to assist in peripheral nerve healing. David Hom, MD, Director, Division of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in the Department of Otolaryngology at UC Medical Center and Matt Hershcovitch, MD, former otolaryngology resident, collaborated with Sarah Pixley, PhD, University of Cincinnati Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology to develop this novel idea, which was nationally recognized with a research grant by the American Academy of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) and the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (AAFPRS) Leslie Bernstein Resident Research Grant.

Recently, the preliminary results of this research were published in the Journal of Biomaterials Applications and the new method of using MicroCT to analyze the biomaterial filaments was highlighted in the Journal of Neuroscience Methods.2,3 The collaborators have seen encouraging results in utilizing magnesium as a method to help improve closing the nerve gap of peripheral nerve injuries to help these patients heal more completely.

Specifically, biodegradable magnesium metal filaments were placed inside biodegradable nerve conduits to attempt to provide the physical guidance and support to aid in the regeneration of peripheral nerves across injury gaps in a rodent model. At six weeks after implantation, magnesium degradation was examined by micro-computed tomography and histological analyses.

Using histological and immunocytochemical analyses, good biocompatibility of the magnesium implants

Surgery: (a) a scaffold diagram (arrows=sutures), (b) surgical pictures of the Mg insertion into nerve at surgery and (c) the PCL conduit in place.

Mg: magnesium; PCL: poly(caprolactone).2Continued on page 3

Surgical simulation has emerged as a proven training tool with significant potential for refreshing previously acquired skills and learning more advanced procedures and techniques.1 As surgical simulation technology has evolved, one of its earliest users, the University of Cincinnati Medical Center, has kept pace with these changes. The UC Medical Center Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery has a long history of using simulation for training, from its early temporal bone laboratory to its current Resident Bootcamp and Midwest Airway course, and the newest expansion of this initiative is a state-of-the-art Surgical Skills Laboratory. The Surgical Skills Laboratory, which is currently under construction and expected to open within the next year, will be available 24/7 and provide critical skills training to all otolaryngology residents in both the adult and pediatric programs.

Charles M. Myer, IV, MD, head and neck surgeon at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, who leads this initiative,

explains, “The goal of simulation is to provide opportunities for residents to practice in real-world situations without risk to the patient.” Faculty will conduct lectures and workshops in the Skills Laboratory, as well as review videos of the residents performing specific skills to evaluate their competency. Helping residents develop the “muscle memory” necessary to perform both common and uncommon procedures, the Surgical Skills Laboratory will be especially useful in providing an opportunity to practice working with high-risk, low-frequency conditions such as orbital hematomas, thyroid hematomas, and airway foreign bodies.

Zenker’s diverticulostomy is one example of a procedure that residents will be able to practice before encountering it in the operating room. Myer and his colleagues have submitted for publication their experience with modifications made to a Zenker’s simulator to improve the fidelity and use as a standardized competency

New Surgical Skills Laboratory to Provide Residents Critical Skills for Real-Life Scenarios

Assistant Professor, Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery(513) [email protected]

Charles M. Myer, IV, MD

Continued on page 5

Emergent evacuation of a retro orbital hematoma

p 3

University of Cincinnati Medical Center

p 4 p 5

ENT Insights ENT Insights

WINTER 2016UCMedicalCenterENT.com

Exploring a Novel Method for Improving Facial Nerve Healing from Facial Nerve Injury Continued from front page

was observed, with good development of regenerating nerve mini-fascicles and only mild inflammation in tissues even after complete degradation of the magnesium.

In the current state, the need for improved facial nerve healing is exemplified by the following patient, a 44-year-old female with a spontaneous history of bilateral facial paralysis with slow facial

nerve healing over three years, giving her a longstanding residual facial paresis of the lower face. Three years later, she had persistent bilateral decreased lower lip competence resulting in drooling, and the inability to smile. The patient required bilateral staged temporalis muscle slings to improve her lower facial support, lip competence and facial movement. The possibility exists that

intervention with magnesium filaments could one day circumvent the need for facial reconstructive surgery such as the procedures done to improve this patient’s function.

Challenging cases such as this example were recently presented at the National AAO- HNS meeting in Dallas 2015 by Continued on next page

Figures A-D: Immunostained regenerating tissues after 6 weeks; (a and b) mid-conduit sections were stained for GLUT1 (green)/S100 (red)/DAPI (blue) in (a) NoMgSa and (b) MgSa animals (*cavity left by Mg, arrows delineate conduit material, bar=300μm). (c and d) Regenerating nerve mini-fascicles, indicated by arrows, run close to the Mg cavities, which are marked by * and arrowheads. The same staining was done on the section in (c), while the section in (d) was stained with ED1 (green)/NF200 (red)/DAPI (blue). Note GLUT1þ perineurium in (c) and thin layer of ED1+ macrophages above arrowheads in (d) (bar in c and d=50μm).

NoMgSa: saline filler only; MgSa: saline and Mg; GLUT1: glucose transporter 1; DAPI: 4’ 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.2

Reproduced by permission of SAGE Publications Ltd., London, Los Angeles, New Delhi, Singapore and Washington DC.

Figure 1a: Preoperative state, resting 44-year-old female with a history of initial bilateral facial paralysis with slow facial nerve healing resulting in longstanding residual facial paresis of lower face. Three years later, she still has persistent bilateral decreased lower lip competence when eating and speaking with drooling and the inability to smile. Figure 1b: Preoperative state, grimacing. Figure 2a: Postoperative state (one year later), resting. She underwent bilateral staged temporalis muscle slings to improve her lower facial support, lip competence and facial movement to control her drooling and allow her to smile. Figure 2b: Postoperative state (1 year later), grimacing.

(a)(a)(a) (1a)

(2a)

(1b)

(2b)

(b)

(c) (d)

New Connection Studied Between Oropharyngeal Cancer and HPV

For decades, oropharyngeal carcinoma has been associated with patient behaviors such as smoking and drinking, but in recent years, scientists have recognized another cause of the disease, the human papillomavirus (HPV). The incidence of these types of oropharyngeal cancer has been dramatically increasing, according to a recent study.1 In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now reports that 72% of oropharyngeal cancer cases are related to HPV.2 Collaborative care and the use of

newer treatment options, both medical and surgical, can yield significant benefits to the patient.

Patients with oropharynx cancers tend to have better outcomes, particularly at high-volume centers, according to many studies.3 “We probably see over 500 new head and neck cancer patients per year,” says Jonathan Mark, MD, Assistant Professor of Head and Neck Surgery at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. Maintaining patient quality of life during Continued on next page

Hom and Ravi Samy, MD. Over the last seven years, Hom and Samy have taught an annual National AAO-HNS course on “Optimal Surgical Strategies for Treating Facial Paralysis” from a facial plastic surgery and neurotology standpoint.4 Continued research into magnesium filament implants, which have the potential to improve repair of injured peripheral nerve defects, may help improve outcomes in these patients. Says Hom, “Our study is preliminary research, but the findings are promising, and seem to indicate that magnesium is compatible with peripheral nerve healing. Clearly, this warrants additional study.”

References: 1. Hom DB, Reanimation of the Paralyzed Face. Clinical Otology. (Eds Pensak M, Choo D) Thieme, 2014. 2. Vennemeyer J, Hopkins T, Hershcovitch M, Little K, Hagen M, Minteer D, Hom D, Marra K, Pixley S. Initial observations on using magnesium metal in peripheral nerve repair. J Biomater Appl 2015;29(8):1145-54. 2. 3. Hopkins TM, Heilman AM, Liggett JA, LaSance K, Little KJ, Hom DB, Minteer DM, Marra KG, Pixley SK. Combining micro-computed tomography with histology to analyze biomedical implants for peripheral nerve repair. J Neurosci Methods 2015;255:122-130. 4. Hom DB, Samy R. AAO-HNS Course, Optimal Surgical Strategies for Treating Facial Paralysis. Dallas, Sept 2015.

Incidence rates for overall oropharyngeal cancer, human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive oropharyngeal cancers, and HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancers during 1988 to 2004 in Hawaii, Iowa, and Los Angeles. Incidence rates for HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers increased from 0.8 per 100,000 during 1988 to 1990 to 2.6 per 100,000 during 2003 to 2004. Incidence rates for HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancers significantly declined from 2.0 per 100,000 during 1988 to 2004 to 1.0 per 100,000 during 2003 to 2004. Overall incidence of oropharyngeal cancers increased from 2.8 per 100,000 during 1988 to 1990 to 3.6 per 100,000 during 2003 to 2004.5 Reprinted with permission. © 2011 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.Director, Division of Facial Plastic and

Reconstructive Surgery. Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery(513) [email protected]

David Hom, MD

cancer treatment is paramount, and the reason many departments at UC Medical Center unite for a weekly multidisciplinary tumor board to discuss each case and develop the optimal treatment plan for each patient. Team members include a head and neck surgeon, a medical oncologist, a radiation oncologist, a neuroradiologist, oncology nurses, and other allied medical personnel.

Mark confirms that patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers tend to be younger and healthier in general, which has led to efforts to de-escalate their treatment to avoid serious side effects and improve their long-term quality of life, while maintaining treatment efficacy.1 One way to de-escalate treatment may be to prepare patients for later chemotherapy treatment with a course of the oral diabetes medication metformin. Metformin appears to interfere directly with cell proliferation and apoptosis in cancer cells in a non-insulin-mediated manner.4 One of the key mechanisms of this medication is the activation of adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK).3 Therefore, simultaneously targeting AMPK through metformin and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR cellular signaling pathway in cancer by an mTOR inhibitor could become a therapeutic approach.3 UC Medical Center is conducting clinical trials for many treatment combinations, and one of the most important is the “Dose-finding Study of Metformin with Chemoradiation in Locally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma,” which is currently recruiting participants. While de-escalation of therapy is not a proven approach yet, it is a promising one.

Mark emphasizes that the most important step is identifying HPV tumors that may have metastasized during an “unknown primary workup.” These tumors, often found in the oropharynx, can be recognized by using special histological stains. Using transoral robotic techniques, surgeons can then remove the tumor tissue, providing a vastly more targeted course of radiation therapy. This surgical approach accompanies more moderate medical treatment regimens to maintain quality of life in this group of oropharyngeal cancer patients.

References: 1. Boscolo-Rizzo P, Pawlita M, Holzinger D. From HPV-positive towards HPV-driven oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015 Oct 31. pii: S0305-7372(15)00194-2. 2. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/headneck.htm. Accessed November 9, 2015. 3. Gourin CG, Forastiere AA, Sanguineti G, Marur S, Koch WM and Bristow RE. Impact of Surgeon and Hospital Volume on Short-Term Outcomes and Cost of Oropharyngeal Cancer Surgical Care. Laryngoscope. 2011 Apr; 121(4): 746–752. 4. Liu H, Scholz C, Zang C, Schefe JH, Habbel P, Regierer AC, et al. Metformin and the mTOR inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) sensitize breast cancer cells to the cytotoxic effect of chemotherapeutic drugs in vitro. Anticancer Res. 2012 May;32(5):1627-37. 5. Chaturvedi, K. et al: J Clin Oncol. 29(32), 2011: 4294-4301.

New Surgical Skills Laboratory to Provide Residents Critical Skills for Real-Life ScenariosContinued from back page

with new residents learning by “shadowing” more experienced clinicians, gradually performing more arduous tasks. However, work hour restrictions have made that approach increasingly difficult. In addition to decreased fatigue and improved functionality among residents, it also contributed to an environment where these trainees have fewer opportunities to practice common procedures and less exposure to more uncommon conditions. The Surgical Skills Lab seeks to respond to this evolving training environment. “Having this space will allow us to move forward and improve our simulation-based education,” concludes Myer. “The role of medical simulation is very innovative and I believe we’re on the cusp of a paradigm shift with academic medical centers starting to embrace this new learning technique.”

References: 1. Heskin L, Mansour E, Lane B, Kavanagh D, Dicker P, Ryan D et al. The impact of a surgical boot camp on early acquisition of technical and nontechnical skills by novice surgical trainees. Am J Surg. September 2015;210(3):570–577. 2. Richtsmeier WJ. Simulated Zenker’s endoscopic staple-assisted esophagodiverticulostomy (ESED) surgery. Laryngoscope. 2002 Jul;112(7 Pt 1):1230-4.

Assistant Professor of Head & Neck Surgery(630) [email protected]

Jonathan Mark, MD

Emergent evacuation of a retro orbital hematoma