UNICEF Nepal: Gobinda's story

-

Upload

kelley-lynch -

Category

Documents

-

view

226 -

download

0

description

Transcript of UNICEF Nepal: Gobinda's story

Schools for Asia Nepal

Gobinda’s storyEXPANDING THE REACH OF CHILD FRIENDLY SCHOOLS

2 UNICEF Nepal

Nepal has made great strides towards achieving the international Education forAll goals. Despite poverty and a recent history of conflict, enrolment in gradesone through five has soared from 64 per cent in 1990 to over 95 per cent in2012, and 74 percent of children aged three through five are now enrolled inEarly Childhood Development/pre-primary education programmes. Butchallenges remain. Despite the fact that primary education is free throughgrade five, 1.2 million children age 5-16 are still out of school. Most are frompoor families or marginalised groups with a high incidence of householdpoverty and child labour. Those who are fortunate enough to attend school,study in environments that are not conducive to learning with teachers whorely on rote learning methods. As a result, student learning assessments showgenerally poor levels of learning with high repetition and drop out rates.

The government’s ambitious School Sector Reform Plan (2009-2015) wasdesigned to address many of these challenges. Equity-oriented measures suchas scholarships for disadvantaged children and free textbooks for all aim tobring poor and marginalised children into schools. The Child Friendly Schools(CFS) National Framework was adopted by the government in 2010. It serves asa guideline for all Nepali primary schools on how to improve service deliveryand quality so that the teaching–learning process is meaningful and joyful forchildren. However, thus far, many of these policies and strategies are not wellimplemented, particularly at the district and school levels. In order to build astronger education system, capacity building is essential—at all levels.

UNICEF is working alongside the government and other education partners in Nepal to make Education for All a reality. The organisations’ new educationprogramme (2013-17) narrows its focus to 15 districts (of Nepal’s 75) whereeducation performance indicators are lowest. Not coincidentally, these 15 also

EXPANDING THE REACH OF CHILD FRIENDLY SCHOOLS

Jadhanga village

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 3

have the highest levels of child deprivation. UNICEF will focus its efforts toaffect real change by targeting a greater number of schools in each district,strengthening the capacity of more education stakeholders and creatingsynergies with other UNICEF-supported programmes, such as health and childprotection. A narrower focus will also allow the organisation to assist inexpanding the CFS National Framework—currently only in grades one throughthree—into the higher grades.

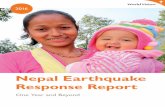

In these pages, you will meet Gobinda, a sixth grade student from themountains of Far Western Nepal. At 14, he shoulders much of the responsibilityfor supporting his family while attending school as often as he can.Unfortunately, Gobinda’s story is all too common. Two in every five children in Nepal live in absolute poverty and children in the Far-Western DevelopmentRegion, where Gobinda and his family live, and particularly the children ofpoor, illiterate mothers suffer most. Like Gobinda, many are engaged in workto help their families. This presents an obstacle to continuing their education.

In circumstances like these, education is critical to breaking the inter-generational cycle of poverty. Over the years from 2013-17, Gobinda and hissiblings will be among the 1.3 million grade one through ten students in Nepalwho will benefit from strengthening of the Child Friendly School approach andits expansion into the upper grades. It is critical that teaching and learning bechild-friendly so that students like Gobinda want to continue—ideally tocomplete eight years of quality basic education and then transitioning tosecondary education. What they learn must be relevant to ensure students areequipped with the skills and competencies that will be useful in their futurelives. And all stakeholders must ensure that measures to promote equity,including scholarships, are properly administered to allow them to continue.

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 5

My name is Gobinda Baduwal. I am 14 years old and I am in thesixth grade. I live in Jadhanga village in western Nepal in thedistrict of Bajura. My father died when I was 10 and my motherhas a bad leg. I live at home with my two brothers and two ofmy four sisters. As the oldest son it is my responsibility to helpmy mother take care of our family. Right now all of us are inschool. I go as much as I can, but I also have to work. If Iget to continue going to school I think I might become a teacher.

06:03 Ama (Mother) returns home after feeding and milking our cow and our buffalo.

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 7

06:10 We have tea and rotis (bread).

8 UNICEF Nepal

“Things are difficult for us because I’m physically disabled. I injured my leg when I wasthree or four years old. It has no feeling. I have to drag it along with me and sometimes pullit with my hands here and there. I can’t climb steep places or carry heavy loads and it isdifficult for me to bend my body, so nobody will hire me to work for them.

“My husband died four years ago. Before that we had a good life. We had money, and hewould help me with the household chores and the children. But he was illiterate. Before hedied he was cheated out of almost all of our land. I am also illiterate. I can’t even sign myname. Sometimes I feel like I am a dead body or a blind person; I am trying to get some ofour property restored, but I have no idea what’s really happening. Whatever others tell me,that’s what I have to believe.

“I have seven children. My oldest daughter, Shanti, is 18. A couple of years ago she ranaway. Now she is married. She has a new baby and I haven’t even seen it. I miss her somuch. My second daughter, Manisha, also ran away. I worry so much about her. I have nothad any news from her in over a year.

“I still have five children at home: three sons and two daughters. My daughter Suna is 15,my sons Gobinda and Rupa are 14 and 12, Dura, another daughter, is six, and my last child,Khadag, is four. What is most important to me now is that my children get at least someeducation so that they are never in this kind of situation in the future. I am trying my bestto keep them in school because from my heart I believe that being able to read and write isthe path to a better life. But their fate is like this: they don’t have a father and they haveto work. I try, but I can’t always provide enough food and clothes and school materials forthem. Sometimes I really have no idea how I will manage.”

NANDA DEVI BADUWALGobinda’s mother

“The other photo you took is good,but I want you to take one of mesitting like this,” says Nanda Devi.“This is how I feel most days.”

10 UNICEF Nepal

06:22 Ama sharpens our sickles before we leave for the field. Every morning before school we help her to do whatever work needs to be done.

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 11

06:39 This morning we are working on land that belongs to a relative. He harvested the wheatand said we could have the stalks for animal bedding if we cut it and take it away.

12 UNICEF Nepal

07:25 ...while Suna and Dura and I collect greens for the animals...

07:23 Ama keeps working...

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 13

07:51 ...and Rupa carries home a bundle of straw.

14 UNICEF Nepal

08:23 While Ama stores the straw under the house, Rupa, Dura and Khadag play.

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 15

08:46 Ama heats up our breakfast--rice with potato and soybean curry.

16 UNICEF Nepal

08:55 It’s time to get ready for school. We wash...

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 17

09:13 ...and then get dressed.

Ama: Khadag, you need to stay home today so I can wash and mend your uniform.

Khadag: No! Fix it now, Ama. I want to go to school!

09:24 Ama says goodbye and tells us where to find her after school.

18 UNICEF Nepal

09:32 School isn’t far. It takes ten to fifteenminutes to get there.

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 19

“Gobinda started school late. He was eight years old. He was our long-awaited first son. We loved him so much. We were scared to sendhim—even with his older sisters. What if he fell into the river? We werescared to let him go anywhere. Finally we realised that all of the otherchildren his age were already going to school, so my husband began totake him. For a long time he walked Gobinda to school every day.”

—Nanda Devi Baduwal

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 21

10:06 Every morning before classes start we have an assembly and we exercise.

22 UNICEF Nepal

How does UNICEF help?

Advocating for equity in education

UNICEF and its partners have been

instrumental in encouraging the

Ministry of Education to implement a

number of equity-oriented measures

throughout the country. This includes

free schooling and textbooks, school

meals for food insecure districts,

scholarships for girls and vulnerable

groups (low-caste groups and children

with disabilities), construction of

latrines that are child, girl and disability

friendly, and school grants for supplies

and stationeries. Advocacy has also

resulted in the setting of a quota for the

female and disadvantaged population

which the government must use when

recruiting new teachers and the

continued development of strategies to

help the Ministry reach out-of-school

children. UNICEF also provides critical

support to improvements in the

information collection systems that the

government uses to monitor equity.

“It is hard to go to school and work. Some days I am late to classbecause I am doing my household chores. Sometimes I miss most of thefirst period. When I miss a class it can be hard to catch up. If there issomething we don’t understand we can ask the teacher once. If we askagain, the teacher yells at us.

“Sometimes I miss school for a few days at a time. I like school and Iknow it is important, but if there is a ‘project’ where I can work and earnmoney to help my family I also have to work. Right now I am working asa labourer on a dam project. Friday is a half day at school. I leave homeearly Friday morning and walk all day to the work site. I stay and workfor three or four or maybe five days and then I come home. When I amgone for so long there is a big gap in my learning. But I think to myself,though I am missing school, this month I will have earned 1000-1500Rupees (US $10-15) for my family. So I feel okay about it. When I gethome I ask my friends from class what the homework was and I try mybest to do it.

“I would like to go to school and not have to do labour work. Most ofmy friends go to school regularly and they learn things. If I could dothat, I would be better educated and I could have a better life.”

GOBINDA BADUWALAge 14, grade six

Work

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 23

10:18

10:20

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 25

School

“I have five teachers. One of them doesn’t teach very well. Last year thatteacher asked one of the students in my class to recite the five timestable. He said, ‘Five times one is five, five times two is ten...’ and theteacher stopped him: ‘No, five times two is eight’—and hit the boy’shands with a stick. Then all of the students together said ‘No, five timestwo is ten!’ The teacher added it up and saw that it was ten and said,‘Oh, you were right. Sorry.’ That made me feel scared to speak up in class.My favorite teacher is the head teacher. He hits our hands if we don’t doour homework, but he doesn’t shout for no reason.

“My happiest day in school was when I was in class three. I was aboutto graduate and we got to spend the last four days of the school year inone of the new child-friendly classrooms. The seating arrangement wasgood. We had round tables instead of desks and benches. Our floors arejust dirt, but the one in that classroom was smooth with wooden boardscovered by a carpet and cushions. There were nice pictures and posterson the walls. We don’t have anything like that in our classroom, evennow. In that classroom they had one teacher all day instead of differentteachers coming in for different subjects. And that teacher taught insuch a kind way. He asked us to do things by saying ‘please’ and he gaveus the opportunity to play and sing.

“My favorite subject is Nepali. We are Nepali. That’s why I like it. I’mnot sure, but I think when I grow up I might like to be a secondaryschool teacher. I would teach Nepali.”

How does UNICEF help?

Implementing equity strategies

Between 2013 and 2017, UNICEF and its

partners will work with schools and

communities in the 15 target districts to

develop locally relevant strategies that

address obstacles to access and

retention. These include the school

calendar, language (only 45% of people

have Nepali as their mother tongue),

disability and gender- or caste-based

discrimination. Strategies will grow out of

school-level data, a situational analysis of

each school and meetings and reflections

with stakeholders. They may include, for

example, radio distance education,

libraries, support to teachers in methods

for reading enhancement, the

development of a local curriculum

(government norms stipulate that 20% of

the social studies curriculum should use

locally developed content to provide more

locally relevant learning, but many

schools lack the capacity to implement

this), and catch-up classes for out-of-

school children.

26 UNICEF Nepal

“Grades one through three in this school became child-friendly fouryears ago. Previously children were taught by the ‘parrot method’ andlearning was only focused on textbooks. Neither the teachers nor thestudents had any creativity. With the Child Friendly Schools Initiative allof that has changed. Children learn through playing and interacting witheach other and with the teacher; they sing and dance; they talk freely inclass and are no longer scared of the teachers.

“When I was in grade three, I knew nothing compared to the childrenwho are in grade one today. They are much more aware of everythinggoing on around them. Every day they have to bring news from theirdaily lives or from the community and present it to the rest of the class.They know the day and the date; they work well in groups and theyspeak up in class. Not only are they getting a good education, they aregetting it at a government school—so it is free—and they are getting itwhile they live at home. This means they can help their families—whichis good not only for their parents, but also for the children. Those whoare sent to far away private schools may be good with books and do wellin their exams, but because they live away from their families, theyoften lack the skills and practical knowledge they need to cope withlife—whether they end up having a job or not.

“I often wonder what these children will be tomorrow. Whatever it is,I know it will be good. That’s why I am looking forward to expanding thechild-friendly approach into all of our classrooms.”

How does UNICEF help?

Strengthening stakeholder capacity

School Management Committees

(SMCs) are in place in most schools, but

many lack the capacity to perform their

roles to assess the situation, formulate

action plans, and monitor progress. For

example, many are unaware of the

nature of the funds that the school

receives from the state. Hence

scholarships meant for girls and the

most disadvantaged children may not be

properly allocated. UNICEF and its

partners are working to strengthen the

capacity of SMCs and other stakeholders

including District Education Officers,

local authorities, teachers and parents so

they can fully participate and make

meaningful contributions to support their

students and their schools over the long

term. UNICEF is also bringing children’s

voices into the process. The organisation

piloted children’s representation in SMCs

in three districts. The initiative was so

successful that it has become part of the

CFS National Framework that is in the

process of being implemented

nationwide.

PADAM BADUWALHead of the School Management Committee

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 27

10:43 “I like to talk with students,” says SMC Head Padam Baduwal. “I think they also need to learn practical things at school, like the importance of planting a kitchen garden.”

28 UNICEF Nepal

“I like going to school. My favorite things are dancing, drawing andplaying with my friends. I also love songs and poems, and there are a lotof those in Nepali, so I like that subject best.

“I loved grades one, grade two and grade three. I could draw more andplay more and I could have a snack at school if I brought one with me. Icould also play the drum in class. In grade three, I drew lots of picturesand they were hanging in the classroom. I felt so happy. I would telleverybody ‘Look, that’s my drawing!’

“When I went to grade four things were different. In grades onethrough three, the classroom had a wooden floor with a carpet and theroom was nice. Now the room isn’t so nice. There are desks and benchesand a mud floor. We don’t hang up any of our work.

“But school is fine. In the morning I finish my chores fast so I can beat school on time. The teachers don’t hit us much and I am getting goodmarks. Only math is a little hard—and sometimes when I am at school Iworry about the work at home, which can make it hard to concentrate.

“If Ama can continue to support my education, one day I want to be ateacher. I would teach English and Nepali. If I can’t do that I will be a farmer.”

RUPA BADUWALAge 12, grade fiveHow does UNICEF help?

The Child Friendly Schools Initiative

UNICEF and its partners implemented

the Child Friendly Schools Initiative (CFSI)

in Nepal beginning in 2004, with a focus

on the early grades of primary school. In

2010, the Ministry of Education

established detailed standards and

indicators through the CFS National

Framework and is now in the process of

rolling these out nationwide. UNICEF, in

addition to supporting 15 disadvantaged

districts, will help the government with

strategies to effectively roll out the new

framework throughout the country.

Another focus for the new country

programme is extending the CFS

framework to target older children and in-

school adolescents. The aim is to improve

the quality of teaching and learning so

that students stay on to complete eight

years of basic education followed by at

least two years of secondary school.

10:56

30 UNICEF Nepal

11:04 “Often I have two students read the English dialogues aloud in front of the class,” says Yam Sharma. “Most of them need a lot of practice with their pronunciation.”

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 31

“The Child Friendly Schools Initiative is a good thing. The children ingrades one through three are very friendly with one another, they areactive and participate, and they are not afraid to talk with the teacher.These are all good things. But most of the time they are just playing. Ibelieve we need to get them to focus more on reading and writing sothat when they move up to grades four and five, they are ready to do thework that is required.

“Teachers used to hit the children if they didn’t do their homework.Now, in grades one through three, the children get to play and theteachers are loving to them and friendly with them. When they get tograde four the children want to carry on in the same way. But they arenot very disciplined. It is hard to control them. They don’t adapt well tothe learning environment and the teachers can’t work well with thembecause they still want to play—but they can’t. They need to focus andthey cannot have so much free time (recess). Gradually we bring themaround, but it takes a month of hard work to change them.”

YAM SHARMAHead Teacher, Nepal National Secondary School, Jadhanga

How does UNICEF help?

Teacher training

To date, most teachers and heads of school

have had little or no training in child-friendly

teaching and learning methods. They do not

have a good grasp of what they are or how

to implement them.

UNICEF Nepal and its partners are

supporting the government in providing

teachers and heads of school in target

districts with the training they need. This

will improve their teaching methods and

allow them to meet the new CFS

standards. By 2017, they will ensure that all

grade one through eight teachers in the 15

target districts have received training and

that children’s general well-being in school

is assured through participatory school

action plans that include health, WASH,

child protection and child participation.

32 UNICEF Nepal

“When my brothers and my sister were young, I had to quit school so Icould help my mother take care of them. I started grade one and then Idropped out for two years. Sometimes, when I saw Gobinda and my oldersisters leaving for school, I wished I was going too. But most of the timeI liked being at home and looking after the others.

“When I went back, I started in grade one again. It was different thanthe first time I went. We did drawing and dancing and singing. It feltgood to be in school again.

“Now I have finished grade three and I am starting grade four. I haveonly been here for a few days. It’s different—we can’t dance and singfreely and we can’t make drawings to display in the classroom and wehave different teachers for different subjects—but it seems okay so far.

“What do I want to be when I grow up? I don’t know. I don’t have any plans.”

SUNA BADUWALAge 15, grade four

11:45

34 UNICEF Nepal

12:09 “I like school,” says six-year-old Dura. “Today I playedwith my friends and I drew a picture of a man.”

“Some parents still feel like the children in grades one, two and three arejust playing. They want to see their children writing and reading all thetime. Playing and singing are extra things for them that don’t look likewhat they think of as ‘learning’. This is a lack of awareness on their part.We need to put more effort into making them understand what ishappening in the classroom.”

—Padam Baduwal, Head of the School Management Committee

How does UNICEF help?

Parent education

Many parents, especially those who have

never been to school themselves, don’t

recognize the impact child-friendly

teaching methods have on their children’s

school performance. Developing

stakeholder capacity also means

enhancing parents’ knowledge and

capacities so that they can support their

children to develop to their fullest

potential.

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 35

12:26 ”I like my teacher. He is kind.”

36 UNICEF Nepal

“Previously, enrolment in this school was low, as was attendance. Schoolsin Nepal are open 220 days in a year, but the majority of children were inschool only 100 days. As a result, repetition and drop rates out werehigh. The teachers were also frequently absent, and they taught usingthe ‘parrot’ method. Children’s ‘learning achievement’—which is measurednot only by performance in exams, but also by factors like cleanliness andpersonal hygiene, participation in class, and doing their homeworkregularly—was just 25 per cent.

“Four years ago, when this school started implementing activities tobecome child friendly, the situation changed. After their training,teachers became accountable to the students: they were present in theclassroom, they cared about what students wanted, and they started toparticipate in student activities. A friendship grew between them.Because they were no longer afraid of the teachers, children wanted tocome to school. Today most students are here for over 200 days of theyear, and few drop out. Learning achievement has risen to 85 per cent.

“Currently, only children in pre-school (ECD) and grades one throughthree study in child-friendly classrooms. When these same students moveto grade four they really feel the contrast. They are looking for the sameenvironment as in the lower grades, but the teachers teach using lectures,not participatory methods. The students don’t understand the change andthey don’t enjoy it. They don’t like their teachers. And because theteachers don’t know how to work with them, they try to assert theirauthority by yelling at the students or hitting them. Both sides aredemanding a change. We must make the upper grades child-friendly too.”

MANBIR KHATIResource Person, District Education Office, Bajura District

How does UNICEF help?

Strengthening the capacity of

education authorities

Nepal still lacks capacity at the national,

regional and local levels to implement

the ambitious measures outlined by the

Government to achieve the Education

for All goals by 2015. This includes the

Child Friendly Schools National

Framework. Thus, UNICEF and its

partners are working at all levels to

strengthen the capacities of duty

bearers so that in the long run, they can

fully play their roles. To achieve this,

UNICEF and its partners provide law

makers, government authorities, and

Ministry personnel with evidence-based

studies, reflection workshops,

information and technical support. They

also work with the government to

ensure that national policies, plans, and

strategies are equity-oriented. At

decentralised levels, they help duty

bearers translate policies into local level

action and support the training of

regional and district-level education

personnel like Resource Person Manbir

Khati. This allows for better monitoring

and support for schools in the

implementation of these activities.

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 37

“I supervise teachers in 66 schools,” says Manbir Khati (right). “It is my job to help thembecome more effective at what they do. I try to visit seven to ten schools every month, but it

is not easy to get to many of them-—the most remote is four days walk from a road.”

12:26

12:48

13:11 “I like playing with blocks,” says four-year-old Khadag, “I don’t like dancing and singing.”

How does UNICEF help?

Preparing children for educational success

Young children in Nepal face particular challenges when entering school for the first time. In

the five UNICEF target districts in the Far Western Mountain Region, home to Nanda Devi and

her family, the repetition rate in grade one is 22.9 percent and the drop out rate is 8.7 percent.

Research shows that Early Childhood Development (ECD) programmes play an important role

in helping children transition into school and succeed because they arrive ‘ready to learn’.

UNICEF is the only major Development Partner in Nepal that is supporting ECD. Not only have

they worked to develop standards that will improve the ECD curriculum and teacher training

nationwide, they have supported the mapping of ECD centres to ensure that the most

vulnerable groups are served and have ensured multi-sectoral coordination (with health,

WASH, nutrition, protection and stimulation) to enhance young children’s holistic development.

Ultimately, UNICEF’s goal is that all children entering grade one will have had ECD experience.

40 UNICEF Nepal

13:35 Ama has a lot of work to do while we are in school. She washes the dishes...

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 41

14:02 ..harvests the dried lentils...

42 UNICEF Nepal

15:20 ...and works with our neighbors to winnow our wheat. “We only have enough land to support us for three months of theyear,” says Nanda. “To get the rest of what we need I helpneighbors with their fields and in their houses and they pay me infood. Whenever there is an opportunity, Gobinda earns money byworking on different projects. The neighbors also provide us withrice to help us get by.”

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 43

15:33 16:09

44 UNICEF Nepal

16:33

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 45

16:34 After school Rupa and I go swimming in the river with our friends.

46 UNICEF Nepal

16:53 Suna and Khadag go to wash the animals.

17:02

48 UNICEF Nepal

17:18 I collect firewood and carry it home.

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 49

17:44 I usually milk the buffalo, but if Ama is here, it won’t give me any milk.

18:28 Ama prepares rotis and pickle for ourevening meal and makes extras for tomorrowmorning’s breakfast. “I feel tired,” she says, “but that’s nothing new. I do this much workevery day. If I had more food I could do morework, but my priority is to feed my children.”

Schools for Asia Gobinda’s story 51

19:04 We do our homework by the light of a solar-powered bulb.

All children deserve an education that will allow them to reach their full potential.

UNICEF is working with the government, DevelopmentPartners, local education authorities and NGOs

to provide Nepal’s most vulnerable children with a child-friendly education that builds a strong

foundation for a better life.

www.supportunicef.org/schoolsforasia

54 UNICEF Nepal

To fund all of its work UNICEF relies entirely on voluntary donations from individuals,

governments, institutions and corporations. We receive no money from the UN budget.

UNICEF’s goal is to make a difference for all children, everywhere, all the time.

ABOUT UNICEF

All children have rights that guarantee them what they need to survive,grow, participate and fulfill their potential. Yet every day these rights aredenied. Millions of children die from preventable diseases. Millions moredon’t go to school, or don’t have food, shelter and clean water. Childrensuffer from violence, abuse and discrimination. This is wrong.

UNICEF works globally to transform children’s lives by protecting andpromoting their rights. Their fight for child survival and development takesplace every day in remote villages and in bustling cities, in peaceful areasand in regions destroyed by war, in places reachable by train or car and interrain passable only by camel or donkey.

Their achievements are won school by school, child by child, vaccine byvaccine, mosquito net by mosquito net. It is a struggle in which success ismeasured by what doesn't happen—by what is prevented.

UNICEF will continue this fight—to make the difference for all children,everywhere, all the time.

Photography, writing and design: Kelley Lynch

Following the success of Schools for Africa, in January

2012 UNICEF launched the Schools for Asia initiative:

www.supportunicef.org/schoolsforasia

Photos this page: Gobinda Baduwal

UNICEF Nepal

PO Box 1187

UN House

Pulchowk

Kathmandu

NEPAL

Tel : + (977) 1-5523 200

Fax: + (977) 1-5527 280

www.unicef.org/nepal