Understanding Small Scale Providers of Sanitation Services ... · demands in slum settlements that...

Transcript of Understanding Small Scale Providers of Sanitation Services ... · demands in slum settlements that...

June 2005

Field Note

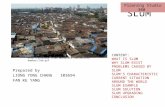

Understanding Small ScaleProviders of Sanitation Services:A Case Study of KiberaLittle is understood of the work of Small Scale Providers of Sanitation Services and their centralrole in sanitation provision but now researchers and urban planners are starting to pay attention.Focusing on sanitation providers in the informal settlement of Kibera in Nairobi, this field noteprovides better understanding of who the SSPSS are, the range of services they offer, andrecommends options for improving the quality and efficiency of their services.

Serving the Urban PoorServing the Urban Poor

The Water and Sanitation Program is aninternational partnership for improving waterand sanitation sector policies, practices, andcapacities to serve poor people

2

Introduction

Throughout the developing world manyof the urban poor depend on informal,private small-scale providers forsanitation services. Theseentrepreneurs receive no governmentresources but survive by offeringservices that the consumers want andare willing to pay for. Until fairlyrecently Small Scale Providers (SSPs)were thought to offer only temporary,short-term solutions to the increasingand unmet demand for sanitationservices and were often ignored bygovernment policy makers and donors.

But there is growing recognition that ameaningful response to the needs oflow-income and informal areas mustinvolve partnerships between smallentrepreneurs and formal utilities. One ofthe reasons for this change in attitude isthe persistent failure by municipalitiesand public utilities to meet servicedemands in slum settlements thatdevelop on the outskirts of cities andtowns. This gap can be filled by SSPswho have shown remarkableresourcefulness in finding simple, buteffective, solutions often under the mostadverse operating conditions.

Kibera a sprawling informal settlement inNairobi, Kenya, is home to half a millionpeople. Here, Small Scale Providers ofSanitation Services (SSPSS) play acentral role in sanitation provision,including the management of publictoilet blocks, the construction of latrines,and the removal of sludge.

Until now, little work has been done tounderstand and evaluate the work ofSSPs, but their importance in the

sector is increasingly attracting theattention of researchers and planners innon-governmental organizations(NGOs), and development agencies.This field note is based on a preliminarystudy carried out during 2003–04, andbuilds on the work carried out by theWater and Sanitation Program-Africa(WSP–AF) since 1997.

The field research is based oninterviews conducted in Kibera with 51service providers (14 groups orindividual manual pit emptiers, 15 truckemptier employees, 12 builders andunskilled workers, and 10 public toiletemployees or volunteer managers), 49households, seven community-basedorganizations (CBOs), six NGOs, fourinternational organizations, two NairobiCity Council officials, one consultantcompany and a Ministry of Healthofficial. The purpose of the study is toprovide a better understanding of whothe SSPSS are, and the range of servicesthey offer, with a view to identifying andrecommending improvements to theenvironment within which they operate,

Kibera’s streets are characterized by uncollected garbage and clogged drainage channels

and the quality and efficiency of theservices they offer.

Kibera’s sanitation nightmare

Kibera is composed of nine villages ofdifferent sizes and population.Strategically placed to provide labor tothe industrial area and neighboringresidential areas, it is the largestinformal settlement in Nairobi andhome to more than a quarter ofNairobi’s estimated total population of2.3 million. It is the most denselypopulated area in sub-Saharan Africawith 2,000 inhabitants per hectare. It isestimated that on average, 3.4 peopleoccupy 10m2 single-room structuresbuilt from mud, timber and corrugatediron sheets.

The high population density, unplannedand crowded housing, and lack ofinfrastructure have resulted in poorprovision of environmental and socialservices. Most roads in Kibera areinaccessible to vehicles, drainage

Understanding Small ScaleProviders of Sanitation Services:A Case Study of Kibera

3

channels on the sides of the roads areoften blocked, pit latrines overflow(especially in the rainy season) andheaps of uncollected garbage areeverywhere.

Kibera is gazetted as government land,much of which has been allocatedinformally to ‘structure owners’(because they do not own the land butonly the structures they have built. Thisfield note refers to them as ‘owners’).

The temporary shelters that the ownerserect are let to the vast number oflaborers seeking daily employment inNairobi. These structures have beensubject to constant threats ofdemolition by the City Council, and thisinsecurity of tenure has affected thelevel of investment that structureowners and residents are willing to risk.Long-term improvement projects arealso hampered by the fact that 90percent of Kibera’s inhabitants aretenants and the owners, who liveelsewhere, have little incentive toprovide services or improve livingconditions in the settlement.

Nairobi City Council does not providesanitation services to Kibera. Althoughtwo sewer lines cross the settlement,most people rely on on-site sanitation.One latrine is often used by severalhouseholds or even several plots (a‘plot’ refers to a group of rooms eitherbelonging to the same owner or placedside by side), which means up to 150people may be sharing a single latrine.In many cases the latrines lack privacyand security, are unhygienic and inpoor condition with gaping holes in thewalls, broken doors and filled pits.

Where neither private nor publiclatrines are available, many residentshave had to resort to using plasticbags that are then dumped in alleysand ditches – a practice called “flyingtoilets”. In the already overcrowdedslums lack of adequate water supply,solid waste management, excretadisposal, drainage and wastewatermanagement impact severely on publichealth. Of the ten most widespreaddiseases in Kibera, five are linked directlyto inadequate water and sanitationprovision (diarrhoea, skin diseases,typhoid, tuberculosis, malaria).

Small scale providersof sanitation services

There is a range of different privateenterprises in Kibera each offeringspecific service skills:

· Latrine management;

· Latrine construction; and

· Latrine emptying.

These services are mostly offered byindependent SSPs who are resident inthe settlement and can deliver whatpublic services are unable or unwillingto provide. Alternative providers

understand the financial situation ofhouseholds served, can offer creditfacilities and respond quickly toconsumer preferences. With theexception of public latrinemanagement, all the service providersare men.

There is a great disparity in theirrevenues (see Graph 1) but theycompare favorably to the minimumwage for general laborers in Nairobi.These figures highlight the important

46

18

33

110

72

58

97

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Volunteer Employee Worker DriverGeneral laborer

minimum

wage in NairobiPublic toilets managers

Certfied

latrines builder

Manual

exhauster Truck exhauster company employees

Providers

Income

A typical pit latrine in Kibera

4

commercial potential of this sector, andthe need for government to recognizeand support the business opportunitiesas well as the contributions made bythese providers in extending servicesto the poor.

SSPSS do not keep account of theirexpenses, and cannot thereforeestimate their income relative to theirrevenue. They have a broad idea oftheir revenue range, which can becompared to the general laborerminimum wage in Nairobi.

The business of operatingand managing latrines

There are six different models ofsanitation systems in Kibera, eachdiffering in ownership, access andmanagement system (see Tables 1 and3). For pit latrines, the two main typesin Kibera are either lined or unlined.

Public latrine blocks

As Table 1 illustrates, municipalauthorities neither own nor managepublic latrines in Kibera. All but one ofthe 20 toilet blocks have beenconstructed using donor or NGO

funding. The latrines are managed byCBOs on a commercial or volunteerbasis (volunteers often receive somecompensation). Operation andmaintenance costs are recovered bylevying a user service charge.

The financial viability of the differentmodels of public toilet blocks has beencompared on the basis of their annualrunning costs in Table 2.

While unsecured land tenure does notappear to hinder developmentorganizations from funding publiclatrines, entrepreneurs appear

reluctant to invest in localinfrastructure because theinfrastructure (investment) may bedemolished at any time. This mayexplain why Kibera has only oneprivately-operated public latrine,which was financed by a micro-creditloan for 35 percent (US$260) of thetotal investment. The structure of thispublic latrine is largely made fromremovable materials such as timberand iron roofing sheets.

Two externally funded pilot projectshave introduced bio-digestiontechnology into a public latrine block.This transforms the lined pit into adigestion reactor producing biogaswhich can be used as an energysource. If this proves to be a viabletechnology, the biogas could be usedto produce electricity and heat waterfor showers. It should also help totackle the problem of sludge disposalsince the process reduces the volumeof excreta, and the resultant wastematerial is less pathogenic.

An analysis of the three models ofpublic latrines shows that:

· Voluntary maintenance does notdeliver an effective and efficient

A public latrine funded by an NGO

ModelOwner of

facilityManagement

mode

Investmentfundingsources

Numberof

latrines

Excretadisposalmethod

TechnologyPrice (in US$) Services

and maintenance

qualityPer use Per month

1 CBO Volunteer Grant 105Pit or bio-digestertoilets

Pit latrines orpour flush

0.025 to0.064

1.3 Poor

2 CBO Employee Grant 24 Pit or bio-digester

Pit latrines 0.025 - Good

3 Privateoperator

EmployeePrivate sector

and microfinance institution

6 Sewerconnection

Pour flushtoilets

0.038 - Good

Table 1: Characteristics of public latrines

Understanding Small ScaleProviders of Sanitation Services:A Case Study of Kibera

5

Owner of facility CBO CBO PrivateManagement mode Volunteer Employee Employee

Investment funding sources Subsidies Subsidies Private sectorExcreta disposal method Pit Pit Sewer connection

Characteristics 8 latrines,4 showers 4 latrines, 2 ablution block 6 latrines, 1 ablution blocks

Water connection with tank Water connection with tank Water kiosk with tankTechnology Pour flush Pit latrines Pour flushVillage Kianda Soweto Laini Saba

Sanitation block construction 10,390 15,974 519Sewer connection 0 0 32Land purchase Community contribution Community contribution 130

Bribes 0 0 97Total investments (US$) 10,390 15,974 778

eEmployees/volunteers 234 564 623

Water 779 31 312Electricity No electricity connection 47 47Miscellaneous (toilet paper, soap,cleaning products, stationery) 450 468 545

Emptying 2,026 405Sewage fee included

in water tariff

Sanitation block construction 2,078 (10,390 in total) 3,195 (15,974 in total) 104 (519 in total)Total annual running costs (US$) 5,567 4,710 1,631Number of users Visitors 219 489 200per day Subscribers1 242 0 0Average cost per user 0.033 0.026 0.022

Annual revenues(from user charges) (US$) 4,548 4,636 2,844

Annual margin (including depreciation) -1018 -74 1,109Annual margin (without depreciation) 1,059 3,121 1,213

Table 2: Public latrine annual operation costs (in US$)

Investments (US$)

Annual running costs (US$)Staff incom

Functioning

Capital allowance/provision for depreciation (5 years)

Model 1 2 3

ModelOwner of

facilityManagement

modeInvestment

funding sourcesNumber

of latrinesExcreta

disposal methodTechnology

Price per month(in US$)

Services andfacilities quality

4 CBOCBO member

and usersGrant 298 Pit Pit latrines

Pit latrines

Pit latrines

2.6 to 5.2 Fair

5 Owner Owner Owner and grant 60 Pit Good

6 Owner Owner Owner (Data not available) Pit Very poor

-

Table 3: Characteristics of private latrines

-

1 Subscribers pay per month

6

service. On the contrary,commercial management leads to aquality service and well-maintainedfacilities, irrespective of whether theblock is owned by a privateoperator or a CBO. Customersappreciate a flexible serviceadapted to their demands, whichinclude lending soap and sandalsfor use in the ablution block.

· Private owner management isfinancially viable, mainly becauseinvestment costs are 13 timescheaper than those for donorfunded blocks (see Table 2). This isdue to a ‘cost hunting’ approach,the use of cheap materials and asewer connection that is lessexpensive than pit emptying.Nevertheless private facilitiesprovide a similar level of comfortand hygiene to expensive donor-funded blocks (though thisconclusion is based on a sample ofone, it is a clear demonstration ofthe achievement of the privatesector).

· The CBO blocks are not financiallyviable if the costs of capitaldepreciation are included in theannual running costs (see Table 2).

Private household latrines

Private latrines are only available tomembers of the same household orplot. In the case of Model 4, theconstruction was wholly funded by anexternal aid agency and themanagement entrusted to a CBO. TheCBO rents each latrine to a differentuser group, and provides operationand maintenance services, includingemptying. These models haveincreased the number of decentlatrines available in Kibera but anumber of difficulties have beenreported, notably poor quality ofconstruction, ownership claims frominfluential people and low cleanlinesslevels by latrine users.

The construction of Model 5 is partiallyfunded by an NGO with the ownerfinancing the balance. This approachhas yielded positive results but NGOfunding of this nature is not likely to besustainable. In this specific case theNGO worked closely with the provincialadministration, which has sometimesplayed a crucial role in encouragingprospective owners to demolish a roomin order to build latrines.

In Model 6, the construction isfinanced entirely by the owner. Theselatrines tend to be poorly constructedwith unsatisfactory standards ofmaintenance unless the owner isresident on the plot. Self-financingowners favor the unlined pit because ofits low cost, which works out at aroundUS$100, including labor and buildingmaterials. Most externally fundedprojects opt for the lined pit.

Lack of coordinationbetween developmentorganizations

Various development organizations(including CBOs, NGOs and UnitedNations agencies) have financedlatrines in villages in Kibera. The levelsof external funding range from 75 to100 percent. Table 4 highlights hugedisparities in the numbers anddistribution of such latrines which arepartly the result of poor coordinationbetween the agencies involved. Thereis a tendency for these externallyfinanced latrines to be constructed invillages where access may be relativelyeasy, but the needs are less urgent

Village Population % of total population Total externally funded latrines

Gatwikira 52,234 11.1 1

Kianda 71,366 15.3 136

Kisumu Ndogo 48,340 10.3 34

Laini Saba 27,340 5.9 156

Lindi 57,715 12.3 30

Makina 95,636 20.5 96Mashimoni 23,437 5.0 0

Siranga 53,850 11.5 30Soweto 37,949 8.1 4

Total 467,867 100 487

Table 4: Presence of externally funded latrines

Understanding Small ScaleProviders of Sanitation Services:A Case Study of Kibera

7

than in more remote and equallyovercrowded areas.

While current planning for sanitationservices by municipalities, utilities andthe donors who support themrecognizes the urgent need for moreand better latrines in Kibera, and for animproved emptying service, SSPs arelargely excluded from the planningprocess. They are simply used asmanpower to construct the facilities.Government should recognize theimportance of the SSPs in the sectorand the contributions their successfuloperations could make in extendingsanitation services to more poorhouseholds.

The business ofbuilding latrines

Latrines in Kibera are normally simpleconstructions of mud, wood andsheets of corrugated iron erected byunskilled workers, so there is littledemand for builders with specialized

masonry skills. As a result, the qualityof construction varies a great deal anddepends primarily on the level of fundsavailable.

In Model 5 (see Table 3), the owner

received a grant of 75 percent of theconstruction cost, and he provided theland and paid the wages. To qualify forthe subsidy, the owner must employcertified builders trained to a highstandard by the NGO providing the

grant. This training has introduced acapacity building opportunity for local

entrepreneurs and these specialistlatrine constructors now earn thehighest wages of all workers in thesanitation sector (see Graph 1).

Individuals and small-scale buildersneed to invest, on average, aboutUS$45 to buy tools and equipment.There is no public subsidy for thisinvestment, which is often donegradually over time. There is alsoevidence of mutual cooperationamong workers to facilitate borrowingor hiring tools.

The business of humanwaste management

Sludge emptying is a key activity forSSPSS since pits need to be emptiedevery 10 months. In Kibera 13 percentof pits are currently unusable becausethey are full (See Graph 2). Consumerdemand for pit emptying is particularlyhigh during the rainy season whenblocked drainage channels andoverflowing latrines create acutesanitation problems. Sludge disposalinto the local river, the Mbagathi, thenbecomes convenient but also polluteswater for washing and bathing.

Construction of a partially funded private latrine

8

Box 1: The manual pit emptiers’ burden

Manual pit emptiers at work

The three main emptying techniquesemployed in Kibera are manual,mechanical, and gravitational.

Manual emptying: anirreplaceable activity

Manual emptying of pit latrines is themethod of choice for 28 percent ofhouseholds in Kibera (see Graph 2). Itis well suited to slum conditions suchas chronic overcrowding, poorvehicular access and heavy sludge,which is difficult to pump up intotrucks.

This sector comprises small groups ofpeople working together on a regularbasis, and some individual operatorswho work on an occasional basis.Since manual emptying is largely aseasonal activity it is not necessarilythe main source of income for eithergroup.

Estimates suggest there are between50 - 100 manual emptiers working inKibera, resulting in competition aroundservice quality and features such asthe use of a handcart, wheelbarrow orbuckets for transport.

The use of 0.2m3 (200 liters) capacitydrums does not allow the workers tofully empty a pit in one trip as pitcapacity ranges from 2m3 to 3m3.When working as a group, people pooltogether and use personal savings(US$39-US$104) to buy equipment,but individuals working alone areusually not able to afford this type ofinvestment. Incomes are irregular andmodest, but still above the minimumwage for a general laborer in Nairobi(see Graph 1).

Few manual emptiers can afford basic protective gear such as gloves and boots

for their work. Lack of equipment exposes them to infections and diseases,

especially when working directly in the pit, which they commonly refer to as the

‘kitchen’. Here, the manual pit emptiers are in direct contact with excreta, broken

glass, and other discarded waste thrown in the pits and, as a result, are likely to

suffer from many health problems.

In addition to being difficult and unhealthy, the work has a very negative social

image and they are often obliged to work at night. Frequently excluded and

stigmatized, these workers express frustration and would like the importance of

their work to be recognized. Moreover, manual emptiers are ignored by public

authorities, despite the role they play in the domestic pit emptying market. They

are often harassed by youth groups who use violence to extort bribes from them.

There is a mistaken perception that manual emptying is illegal.

Manual emptying will remain as a necessary method for exhausting pit latrines for

as long as vehicle access is limited in Kibera.

Understanding Small ScaleProviders of Sanitation Services:A Case Study of Kibera

9

Table 5: Annual licence fees for private truck operators

Truck capacity (m3) Licence fee (US$)

0 to 3 2603 to 7 520> 7 780

A food kiosk located next to a sewer manhole, rendering it inaccessible

Limited access hinders realcompetition in mechanicalemptying services

Mechanical emptying is the first choiceof households (See Graph 2), as it isthe cheapest, most hygienic andfastest method. Nevertheless, thepresence of sludge and solid waste inthe pit hampers the process.Accessibility is also a huge problem formechanical emptiers and is thegreatest deterrent to real competition inKibera. Run by CBOs, the only twotrucks based in the slum aresubsidized and are smaller than mostprivate trucks. Beyond Kibera, theNairobi City Council Water andSewerage Department (NCCWSD)provides truck emptying services in thecapital city, but, at the time of writing,they had only two fully operationaltrucks2. Because the NCCWSD hasstruggled to provide reliable services, ithas increasingly allowed the privatesector to get involved in this activity.

Since 1998 licences have been issuedto private operators (see Table 5)allowing them to carry out mechanicalemptying and discharge the sludgeinto the city’s sewerage network sincethe treatment plants are far from thecity center. In 1999, only three privateproviders were operating in Nairobi.Five years later, there are about 30operators, of which 10 are licensed.These private operators compete withfive mechanical emptiers subsidized bythe municipality or developmentorganizations. This practice of issuinglicenses, combined with the lack of areliable public service, has confirmedthe role that the private sector hasbeen able to play in service provision.

Gravitational emptying

Gravitational emptying is used by 13percent of households but is generallyonly possible when the pit is next to ariver or a drain as the contents flowdirectly into the water. The process isusually facilitated either by manualemptiers at a cost of US$22 or by theowner of the latrine.

Few accessible authorizedand environmentally-friendlysites for disposal

Kibera has no dedicated disposal siteand human waste disposal is a majorproblem. While mechanical emptiersmainly discharge sludge through thesewers, manual emptiers have toemploy different options. They can dig

a pit to bury the sludge, dump it almostanywhere when it is dry, or pour it intodrains, streams or sewer manholeswhen it is liquid. The choice primarilydepends on the distance of thedisposal site from the worksite, assludge transport is difficult since it isdone either by handcart in the bestcase scenario or carried in buckets.Accessibility of sewer manholes is alsoa problem, as other structures havefrequently been built on top of them orare too close by to allow access. Inaddition, residents can hamper accessto manholes, as they fear the resultingdisturbance and inconvenience.

In practice, manual emptiers normallydispose of their waste in streams. Thisis one of the reasons why manual

2 Truck emptying services were taken over by the newly-formed Nairobi Water and Sewerage Company in May 2004

10

Investmentssources

Type of provider Emptyingsite

Tariffs

Per trip Per 1m3

Private sectorManual emptiers (0,2m3 drum) Kibera 8 40

Truck emptiers (3 to 22m3 tank) Nairobi 57 6

DevelopmentVacu-tug (0,5m3 tank) Kibera 9 18

organizations Truck exhauster (3m3 tank) Kibera 196 6

Nairobi 36 12

NCCWSD City council trucks (3 to 8m3 tank) Nairobi

Pit latrines 26

Septic tank in areas not sewered 32

Septic tank in areas sewered 45

The Vacu-tug is a small mechanical exhauster designed to be used in informal settlements.

emptying is a seasonal activity withpeak periods corresponding to rainyseasons, when the sludge is washedaway by rainwater. Manual andgravitational emptying are compromisesolutions to the sanitation problems ofKibera. They enable the residents toclear their latrines but with adverseconsequences for health and theenvironment. Improper excretadisposal is a major health risk andcontaminates the river water. Blockeddrains and heaps of uncollectedgarbage are unsightly, unpleasant andprovide breeding sites for mosquitoesand flies.

Emptying tariffs

Mechanical emptying tariffs are lowestper trip for services funded bydevelopment organizations, but theseare equal to or more expensive thanprivate sector services when calculatedper quantity exhausted (see Table 6).Manual emptying services have thelowest minimum price, which suitscustomers with limited financial meanswho only want to reduce the pitlatrine’s contents as opposed toemptying it completely. However, whenthe cost is based on the quantity

removed, this works out as the mostexpensive method. Complete emptyingof a 2.5m3 - the average pit size -costs US$100. But if the result is thesame, the nature of the work is totallydifferent and accessibility constraintsoften make this option the only onepossible. It is interesting to note thatmany slum dwellers are convinced thatmanual emptying is the cheapestoption. The poorest people living in theleast accessible places have no otheroption but to pay almost seven timesmore than those in servicedsettlements.

Conclusion

This preliminary research has shownthat SSPSS are delivering essentialservices to low-income areas, and thattheir operations form the basis of a realbusiness that is responsive toconsumer demand. Despite the vitalservice they provide in insecure andoften ‘risky’ slum areas, SSPSS haveno formal stake in the sanitation sectornor do they influence sector decisions.These small providers have thepotential to improve sanitation servicesin Kibera at comparatively lowinvestment costs. But to achieve thispotential the following steps need to betaken.

1. The SSPs are poorly organized atpresent, have no formal serviceassociations and very little contactwith other stakeholders. Bettercoordination would increase theirbargaining power and help them togain proper recognition for thecontribution they make in the

Gravitational emptying is common where a pit laterine is located next to river

Understanding Small ScaleProviders of Sanitation Services:A Case Study of Kibera

11

sector. In a situation where‘informal’ is sometimes interpreted(wrongly) as ‘illegal’, a regulatoryframework needs to be developedwhich is adapted to localcircumstances, fosters andsupports existing arrangementswhich work, and providesenforceable consumer protectionfor vulnerable groups. NGOs andexternal aid agencies also need tocoordinate their activities throughcloser dialogue with allstakeholders and more effective

I. Stakeholder cooperationI. Stakeholder cooperation

1. Support private service providers’ coordination

SSPSS coordination through formal associations would

help transform them into real partners in the sanitation

sector. Regulating mechanisms need to be developed

to avoid the formation of cartels.

2. Promote a stakeholders’ dialogue

Dialogue between the various stakeholders (SSPSS,

public authorities, utilities, development organizations)

would help to clarify issues and obstacles, to better

articulate activities of the various actors, and to make

better use of the skills and know-how of the local

private sector.

3. Promote coordination between NGOs

Better coordination between NGOs, who are often

project pioneers who link donors with communities,

would greatly improve the efficiency of assistance to

the sector.

4. Create an enabling framework for SSPSS

Start discussion between public sanitation authorities

and SSPSS to develop agreements, and good

professional practices especially with regard to sludge

disposal. This framework should not restrain SSPSS,

but rather take advantage of their flexibility.

Box 2: Recommendations for improving Sanitation Services in Kibera

planning of their interventions.2. There is need for a concerted effort

to improve the workingenvironment of SSPs, the mostcritical of which is to enable betteruse of existing sewers for sludgedisposal. There is an urgent needfor the construction of new facilitiesand better regulation of sewermanholes.

3. Maintenance of sanitation facilitiescould be improved throughcommercially-managed public toiletblocks. Construction standards

would benefit from a training coursetailored for latrine masons.

The proposals which have emergedfrom this study are summarised in Box2, but any proposals regarding SSPSSshould be part of a bigger strategy toimprove living conditions in the slumsof Africa. These improvements wouldinclude the development of basicinfrastructure such as roads, drainage,waste disposal, and the provision ofpower. It is however clear that suchstrategies would need to first address thefundamental issue of land tenure.

II. SSPSS working envirII. SSPSS working environmentonment

5. Develop and implement a sludge disposal policy and

the construction of facilitiesA stakeholders’ consultation needs to be conducted on

sludge disposal options, which would lead to the

development of a sludge disposal policy that would

specify accountable roles and enable the construction

of appropriate facilities.

6. Facilitate and regulate the use of sewer manholes

Where technically possible, the use of sewer manholes

in Kibera as a solution to liquid sludge disposal should

be encouraged and regulated through a licence issued

to all manual and mechanical emptiers.

III. Latrine quality and coverageIII. Latrine quality and coverage

7. Support private investment into public latrines

Public authorities should support and encourage

private sector investment in the building of public latrine

blocks. This would include assurance of investment

durability through property titles, and discounted rates

for water supply. Commercial management of latrine

blocks needs to be encouraged and regulated.

8. Train masons for latrine construction

Government and NGOs should support the training of

masons to promote quality improvements in the

construction of sanitation facilities.

Serving the Urban PoorServing the Urban PoorThis series of field notes on Serving the Urban Poor aims to provide lessonsto public sector decision-makers, managers and implementers, and theirprivate partners, to tackle the challenges of service delivery to the urban poor.The series is concerned with the key issues and actions necessary to improvethe scale and rate of progress towards the MDGs in urban areas: makingutility reform work for the poor; enhancing the role of local private providers;promoting incentive-driven, predictable enabling environments; andstrengthening consumer voice and mechanisms to improve the accountabilityof service providers.

June 2005

WSP MISSION:To help the poor gain sustainedaccess to improved water andsanitation services.

WSP FUNDING PARTNERS:The Governments of Australia, Austria,Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Italy,Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway,Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom,The United Nations Development Programme,and The World Bank.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:This paper has been prepared by Sabine Bongiand Alain Morel, based on a working document“Les petits opérateurs indépendants del’assainissement à Kibera (Nairobi)”.Information was gathered through fieldresearch in partnership with Maji Na Ufanisi.The text was reviewed by Barry Jackson,Ousseynou Diop, Marc Vezina and PeterKolsky. A special word of thanks is due tocolleagues and friends who helped withfeedback and technical support: Piers Cross,Jean Doyen, Andreas Knapp, ShagunMehrotra, Micheal Muriithi, Janelle Plummerand Nathalie Semoroz, and to the Maji NaUfanisi team who contributed greatly to thiswork. The paper was edited by KathleenGraham-Harrisson and Melanie Low, andproduced by Toni Sittoni.Logistical assistance was provided by JaneWachuga and Peter Ng’ang’a.

Photo credits: Sabine BongiPrinted by Kul Graphics Ltd

Water and Sanitation Program -

Africa

World BankHill Park BuildingUpper Hill RoadPO Box 30577NairobiKenya

Phone: +254 20 322-6306Fax: +254 20 322-6386E-mail: [email protected]: www.wsp.org

Bibliography

Bongi, Sabine, and Morel, Alain. 2004. “Les petits opérateurs indépendants del’assainissement à Kibera (Nairobi)”. Working document. Water and SanitationProgram-Africa Region.

Collignon, Bernard. 2002. “Les entreprises de vidange mécanique dessystèmes d’assainissement autonomes dans les grandes villes africaines:Rapport de synthèse final.” Hydroconseil.

Collignon, Bernard, and Marc Vézina. 2000. “Independent Water and SanitationProviders in African Cities: Full Report of a Ten-Country Study.” Water andSanitation Program-Africa Region.

Kariuki, M., and J. Mbuvi. 1997a. “Water and Environmental Sanitation Needsof Kibera: A Rapid Needs Assessment.” Field Note. Water and SanitationProgram – East and Southern Africa Region.

Kariuki, M., and J. Mbuvi. 1997b. “The Water Kiosks of Kibera.” Field Note.Water and Sanitation Program – East and Southern Africa Region.

Mohamed, Farid. 1999. “Small Scale Independent Providers of Water andSanitation to the Urban Poor: A case of Nairobi, Kenya.” Water and SanitationProgram – East and Southern Africa Region.

Seureca, 2002. Kibera Urban Environmental Sanitation Project, Diagnosis andSituation Analysis, Final report, Republic of Kenya, Ministry of LocalGovernment Urban Development Department, Nairobi City Council Water andSewerage Department, AFD.

Water and Sanitation Program – East and Southern Africa Region. 1999. “Waterand Sanitation Services to the Urban Poor: Small Service Providers Make a BigDifference.” Field Note Number 5. WSP-ESAR.

Water and Sanitation Program – East and Southern Africa Region, 1997, KiberaRapid Needs Assessment, Urban Environmental Issues, Third Nairobi water andsupply, Informal settlements distribution infilling component, internal workingdocument, Kenya. Internal Paper.