Oral history interview with Shirley Staschen Triest, 1964 ...

Unconventional Estrogens: Estriol, Biest, and Triest · Biest, and Triest MAIDA TAYLOR, MD, MPH,...

Transcript of Unconventional Estrogens: Estriol, Biest, and Triest · Biest, and Triest MAIDA TAYLOR, MD, MPH,...

-

UnconventionalEstrogens: Estriol,Biest, and TriestMAIDA TAYLOR, MD, MPH, FACOGUniversity of California, San Francisco, California

In recent years, the seemingly rock-solid listof benefits of estrogen has been assailedover and over again. These kinds of chal-lenges are not new in the history of hor-mones in the United States, but the rate atwhich information reaches consumers hasaccelerated tremendously. Patients get thebad news from medical journals as they readtheir morning newspapers, and physicians intheir offices are often times unaware and un-prepared for the onslaught of anxious callsthat hit them with tsunami-like force. Evenif the journal has arrived ahead of the wave,the issue is often unopened, still in its plasticmailer hidden beneath a pile of laboratoryreports, insurance forms, and bills.

The presumed benefits of hormones de-rive from a body of literature that is fraughtwith bias. Concerns and challenges to theuse of exogenous estrogens began to arise inthe second half of this past century, whenconcern about the safety of oral contracep-tives surfaced. After the Nelson Hearings inCongress in 1968 and 1969, which centered

on reports of increased rates of “vascular”disease in oral contraceptive users, estro-gens were deemed dangerous for women athigh risk. Texts and prescribing guidelineslisted a number of high-risk conditions thatcontraindicated the use of sex steroids. Thelist included all women at risk for myocar-dial infarction, stroke, migraine, diabetes,obesity, hypertension, renal disease, meta-bolic disorders, and more. A family historyof these disorders was also cited as a poten-tial contraindication to the use of estrogen.1

So, for almost all of the past half-century,only the healthiest women—white, uppermiddle class, educated, insured—have beenallowed the luxury of using menopausal hor-mones, whereas women at risk were deniedestrogen, directly by virtue of being truly athigh risk and indirectly by being poor withlimited access to health care. We selectivelyprescribed hormones to women who havealso been determined by careful analysis tohave better health indicators—lower choles-terol levels, higher levels of fitness, andlower blood pressure—than nonusers didbefore they start using hormones.1

Most of the data supporting the claims re-garding health benefits of estrogen reside inobservational studies, not randomized con-

Correspondence: Maida Taylor, MD, Associate ClinicalProfessor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology,and Reproductive Sciences, 785 Foerster Street, Univer-sity of California, San Francisco, CA 94127. E-mail:[email protected].

CLINICAL OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGYVolume 44, Number 4, pp 864–879© 2001, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc.

CLINICAL OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY / VOLUME 44 / NUMBER 4 / DECEMBER 2001

864

-

trolled trials (Table 1). The presumed ben-efits may be weaker than we have been led tobelieve. The benefits of estrogen to bonehave been challenged. One study suggeststhat if hormone replacement therapy (HRT)is used for less than 9 years, bone mass byage 80 was only 3% higher in HRT usersthan in nonusers.1 Clearly, at this time, theevidence for estrogen as prevention for car-diovascular disease resides only in observa-tion studies, highly contaminated with se-lection bias. Moreover, recent studies haveunexpectedly found that women with coro-nary vascular disease, as seen in the Heartand Estrogen/Progestin ReplacementStudy2 trial and in women with cerebrovas-cular disease, actually may exhibit wors-ened outcomes compared with non-users.Moreover, the American Health Associationin July 2001 revised its recommendationsregarding the use of estrogen, stating that es-trogen should not be advocated for the treat-ment of preexistent cardiovascular diseaseand that it probably has little role in cardioprevention.3 Breast cancer also represents achallenging Gordian knot for biostatisti-cians, epidemiologists, and clinicians. Cur-rent consensus appears that the baseline risk

of two cases per 100 women in 10 years hasincreased to three cases per 100 after 10years of estrogen exposure, and lately, thisfact has been hammered repeatedly with thestatistical bludgeon recounting this risk as a50% increase. This is a truth, but a truthphrased in the most provocative way pos-sible. Fifty percent excites much greateranxiety and elicits much great media atten-tion than one additional case per 1,000women-years of exposure to HRT. As healthprofessionals debate relative risks, absoluterisks, and confidence intervals (CI), almostevery women’s health and breast cancer ad-vocacy group, fueled by books like BarbaraSeaman’s The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill4

and The Controversy in Women’s Hormones5

and Dr. Susan Love’s Hormone Book6, tellswomen that estrogen is a principle cause forthe increased incidence and prevalence ofbreast cancer in the past 25 years.

Endometrial cancer risks imposed by un-opposed estrogen are well known. Gyne-cologists and other health professionalshave come to believe that the use of proges-tins provides almost absolute protectionfrom this risk. But, large numbers of womenare not using their progestins as directed, of-ten skipping or lowering doses to try tolessen progestin-related side effects (Table2). The protection doctors assume to be pre-sent oft times is severely compromised bypoor adherence and compliance with theprogestin arm of HRT. Moreover, whereasdoctors tend to view the malignancies in-duced by estrogen therapy as “good can-cers”—diagnosed at early stage, evidencingslow growth, and attaining high cure rates—

TABLE 2. Progestin Side Effects

• Bleeding—withdrawal, over-progesteronization• Premenstrual syndrome—mood changes and

other impairments• Breast pain• Headache• Appetite change—anabolic effect• Bloating—decreased gastrointestinal motility• Attenuation of lipid improvements and

vasomotion benefits of estrogen

TABLE 1. Evidence-Based Benefits ofEstrogen Replacement Therapy

Decreased RRLevel ofEvidence

Strength ofRecommendation

Vasomotorsymptoms I A

Genitourinarysymptoms II-2 A

CV treatment/prevention I/II-2 D/B

Hip and vertebralfracture II-2 A

Alzheimer disease II-2 BColorectal cancer II-2 BTooth loss II-2 BBreast cancer

mortality II-2 BDeath at age

youngerthan 80 II-2 B

* RR = relative risk.

Unconventional Estrogens 865

-

women do not view any cancer as a “good”cancer.

Natural EstrogensThe discontent and discomfort provoked bythe current HRT offerings have sent womensearching for new options. Estimates arethat only 10–25% of eligible menopausalwomen use conventional HRT, 30–50% ofwomen given prescriptions for HRT neverhave them filled, and 40–60% of womenwho started using HRT have stopped.7,8 Theunsettled and unsettling controversies sur-rounding HRT have not completely dis-suaded women from using hormones. How-ever, women are looking for alternatives toconventional estrogens that provide the ben-efits of pharmaceutical-grade hormones, butwith fewer attendant side effects and risks,ie, a “kinder and gentler” estrogen. Advo-cates for the “forgotten estrogen,” estriol,are willing to give them what they want, themyth of a risk-free estrogen.

Increasingly, women are asking for com-pounded estrogens, particularly estriol andso-called triest and biest preparations, whichcombine estriol with both estradiol and es-trone or with just estradiol, respectively. Thepopularity of these products is fostered by anumber of factors. Women are being giventhe naïve and simplistic impression that es-triol can provide all the benefits of hormonereplacement without the attendant risks ofneoplasm and venous thrombosis. Propo-nents of estriol capitalize on the fears ofwomen, promising not only a decreased riskcompared with conventional estrogens, butprotections against the effects of other estro-gens. With great American entrepreneurialzeal, producers of estriol and the com-pounded, blended estrogens command highprices for this “wonderful” alternative.Many promoters of estriol are as naïve asmany patients, and they do not understandthat the data linking estriol to lowered risksof endometrial and breast cancer are an as-sociative phenomenon, with estriol being amarker of, not necessarily a cause of,

lower rates of these diseases. Most of the re-mainder of this review centers on the usesand abuses of the data on estriol and its es-poused role in hormone replacement.

Comparative EstrogenologyEstriol is the third major estrogen producedby human females. Estradiol, estrone, andestriol serve different functions in womenand different functions at different times inwomen’s reproductive life cycles. Like al-most all estrogens used for HRT, except forconjugated equine estrogens (CEE), estriolis produced from plant sterol molecule. Infact, most steroids used in HRT, estrogens,and progestins are derived from diosgenin, aplant sterol. Through biotransformation in apharmaceutical laboratory, diosgenin is firstreconfigured into progesterone, then used asthe source molecule for production of andro-gens, estrogens, and progesterins like theC19 nortestosterone in oral contraceptives.The precursor molecule is extracted fromhigh-yield yam or soy plants. The term“plant-derived” or “natural” in advertisingparlance can be assigned to any steroid thatstarted as a plant precursor. Therefore, com-pounded products, commercial progester-one, equine estrogens synthesized in thelaboratory, such as those used in esterifiedestrogen products, and even norethindroneacetate and the other progestins in oral con-traceptives could be termed “plant derived”or “natural.” Manufacturers put pictures ofyams and soy plants in their ads, implyingthat the estrogens are manufactured by thegreen plant, not the other kind of plant: achemical plant! The maker of CEE, Prema-rin (Wyeth Ayerst, Philadelphia, PA), haseven resorted to adding a tag line on thepackage that reads, “estrogens obtained ex-clusively from natural sources.” Truly, preg-nant mare’s urine is a natural output.

The principal estrogen before menopauseis 17� estradiol and is produced by the pre-ovulatory follicle and, after ovulation, by thecorpus luteum. After secretion by the ovary,some estradiol is bound by sex hormone-binding globulin, whereas unbound estra-

866 TAYLOR

-

diol enters cells, binds estrogen receptors,and interacts in the nucleus to modulate tran-scription of estrogen-responsive genes. Es-tradiol is converted to estrone in the liverand other tissues by 17� estradiol dehydro-genase. Estrone is further metabolized in theliver to estrone sulfate, a water-soluble es-trogen that constitutes the circulating estro-gen in highest concentration. Estrone pro-vides a reservoir for estradiol production. Inpostmenopausal women, peripheral conver-sion of androstenedione in adipose tissueyields mostly estrone. In women of repro-ductive age, estradiol levels vary throughoutthe monthly cycle. During the early follicu-lar phase, estradiol levels are low, between40 and 80 pg/ml. Later in the follicularphase, at midcycle around ovulation, estra-diol levels are at their highest, at approxi-mately 250 pg/ml, favoring the developmentof a rich endometrial lining suitable for im-plantation of a fertilized ovum. During theluteal phase, estradiol levels gradually de-crease to approximately 100 pg/ml and fur-ther decrease to approximately 40 pg/ml bythe beginning of menstruation. Mean dailycirculating estradiol level is 100 pg/ml. Se-rum levels of estradiol for HRT arbitrarilymatch those seen in the early follicularphase.

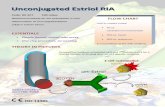

The potency of different estrogen prepa-rations for use in estrogen replacement canbe evaluated in a number of ways. Clini-

cally, potency may be assessed by evalua-tion of maturation of vaginal epithelium.Gonadotropin suppression or induction ofhepatic protein synthesis provide additionalbioassays for assessing the relative potencyof estrogen replacement preparations. Fig-ure 1 compares the biologic potency of twooral estrogen preparations, CEE (0.625 mg)and micronized 17� estradiol (1 mg), acrossseveral parameters. These two doses areequivalent in their ability to suppress fol-licle-stimulating hormones, but differentwith regard to effects on corticotropin-binding globulin, sex hormone-bindingglobulin, and angiotensinogen levels (Fig.1). These differences may define differenttissue effects and differential clinical ef-fects, but overall, in terms of the major indi-cations for HRT, the outcomes are similar.Whereas almost all long-term studies of es-trogen in the United States in the past 40years have been performed with CEE, mostreproductive endocrinologists will agreethat other forms of estrogen, including es-trone and estradiol, offer comparable treat-ment of vasomotor symptoms, retardation ofbone loss, and reversal of urogenital atro-phy. Also, different types and doses of oralestrogens yield remarkably similar levels ofestradiol.9 This self-same logic, however,also suggests that the attendant risks of es-trogen treatment, that is breast cancer risk

FIG. 1. Relative biological potencyof oral estrogen preparations. To com-pare biologic potency of conjugatedequine estrogens and micronized 17�estradiol, four specific parameters ofestrogenicity were measured. Theseincluded changes in serum follicle-stimulating hormone, corticotrophin-binding globulin, sex hormone-binding globulin, and angiotensino-gen. From Mashchak CA, Lobo RA,Dozono-Takano R, et al. Comparisonof pharmacodynamic properties ofvarious estrogen formulations. Am JObstet Gynecol. 1982;144:511–518.

Unconventional Estrogens 867

-

and enhanced thrombotic risk, also are com-parable with estrogens other than CEE.

Recent estimates of risk reduction11 sug-gest current users of estrogen replacementtherapy have an odds ratio of 0.35 (95% CI:0.24–0.53) for hip fracture, and former usershave an odds ratio of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.57–1.01). The protective effects of estrogenagainst osteoporotic fractures have beenprincipally demonstrated in studies usingCEE, with bone mineral loss being com-monly used as a surrogate marker for long-term fracture risk. The dose range for pre-venting bone loss with CEE is between 0.3and 0.625 mg. Oral micronized 17� estra-diol 0.5 mg arrests bone mineral loss in 60%of women, whereas the remaining 40% mayrequire higher doses of 1 to 2 mg daily.Transdermal estradiol products also havebeen approved to prevent osteoporosis at adose of 25 µg per day.

The optimal dose of estradiol, or any es-trogen for that matter, depends on the bio-logical outcome of interest. Clearly, the bestdose for bones is the highest dose, becausethere appears to be a stochastic response,with increasing doses producing increasingpositive bone responses. Similarly, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol also in-creases steadily with increasing doses.However, when considering “bad” out-comes, the lowest dose would appear to bethe safest dose. With regard to endometrialproliferation, breast cancer, triglyceride lev-els, and coagulation profiles, administrationof the lowest dose possible is desirable tominimize risk. The optimal dose for cardio-

vascular protection (if it exists at all) has yetto be determined for any estrogen. In sum-mary, the best dose would be one with maxi-mal benefit and minimal risk, perhaps thesmallest effective dose for the longest periodof time. Currently, the optimal therapeuticrange for serum 17� estradiol levels isthought to be between 60 and 80 pg/ml, withacceptable levels between 40 and 120 pg/ml.As studies continue and understanding ofdosing requirements increases, these valuesmay need to be redefined for different popu-lations, different health outcomes, differentdegrees of symptomatology, and differencesin physiology over the course of time aswomen progressively age.

EstriolWhile pharmaceutical marketers and adver-tisers compete to win our hearts, minds, andhands writing the prescriptions, alternativeestrogen products are being promoted as“safer” options for menopausal women. Es-triol is being offered as the estrogen ofchoice. Estriol is said to hold a lesser poten-tial risk than estradiol or estrone, particu-larly in regard to the increases in endometri-al and breast cancer associated with estrogenreplacement therapy use. At the least, advo-cates insist that estriol decreases the risk ofthese cancers. Some promoters even tellwomen that estriol can block the neoplastic-inducing effects of estradiol and estrone. Atypical example is presented here, takenfrom Community.Drug.com12:

“Estriol (E3) plus progesterone: Estriol(E3) is the estrogen that is made in large

FIG. 2. Tissue/plasma gradients. FromThijssen JH, Wiegerninck MA, DonkerGH, et al. Uptake and metabolism of oes-triol in human target tissues. J SteroidBiochem. 1984;20(4B):955–958.

868 TAYLOR

-

quantities during pregnancy. Both estrioland progesterone, which exist in muchgreater quantities than the other sex hor-mones in pregnancy, have potential protec-tive properties against the production of can-cerous cells. Estradiol is the most stimulat-ing to the breast (causes cell division) andestriol the least.

For a dose equal to 0.6 to 1.25 mg of Pre-marin, you would require 2 to 5 mg of es-triol. Some advantages of estriol are:

● Better than estradiol to treat urinary tract in-fections

● Most beneficial to the vagina, cervix, andvulva (for vaginal dryness treatment)

● Benefits of other estrogens without the risks● Estriol leaves the body more quickly than es-

tradiol and estrone● Estriol is breast-tissue protective, not prolif-

erative”

Alternative women’s health advocateselected estriol as the natural estrogen ofchoice for menopause, based on informationderived from animal models, observationalstudies on endogenous estriol in selectedpopulations, and limited human clinical tri-als. No long-term interventional studiescomparing estriol with other estrogens re-garding long-term risks exist, and shortertherapeutic trials of estriol do not supportthese claims.

Estriol is the principle estrogen producedby the placenta. Reasoning dictates that dur-ing gestation, high levels of estriol protectestrogen-sensitive tissues from the neo-plastic-inducing effects of the other hu-man estrogens. Enthusiasts promotingestriol extrapolate that exogenous adminis-tration will have a salutary effect, somehowmimicking the action of endogenous estriol.The role of endogenous estriol or exogenousestriol as an active estrogen is highly specu-lative.

Observational studies have found thatwomen with early age during first-termpregnancy excrete more estriol than do nul-liparous women. Asian females excretemore estriol than do their American counter-

parts, and when Asians migrate eastward toEuropean or Americanized areas, becomingincreasingly acculturated into Western life-styles, estriol excretion decreases while, in-versely, breast cancer rates increase.13 It ap-pears that high estriol excretion is a markerof lower breast cancer risk in premenopausalwomen. In postmenopausal women, thestory is quite different. As serum estriol, es-trone, and estradiol increase, urinary excre-tion of each these estrogens increases, andbreast cancer risk increases. High estriol lev-els in postmenopausal women appear to be amarker of high endogenous estrogen activityand increased breast cancer risk.14,15

During the 1970s, research by Lemon etal sought to establish estriol as a potentialpreventive of and treatment for breast can-cer. Using female Sprague Dawley rats,breast tumors were induced by ingestion of7,12 dimethylbenza, anthracene, or procar-bazine, which are known carcinogens.16 Theanimals in this exemplar study were pre-medicated with subcutaneously implantedpellets with 5 to 7 mg normal saline plus1–20% estriol 48 hours before exposure tothe carcinogen. Rats that were pretreatedhad markedly reduced rates of tumor induc-tion. Moreover, rats treated after inductionevidenced tumor regression. Estriol alsoproduced remissions in human breast cancerpatients,17 a phenomenon that can be seenwith a number of estrogens. Diethylstilbes-trol,18 estrone, and estradiol all have beenused successfully to induce short-term re-missions. Chemotherapeutic adjuvanttherapy later was shown to produce evenbetter outcomes.19 In 1978, Follinstad pub-lished a commentary in JAMA entitled “Es-triol, the Forgotten Estrogen?”20 He impliesin this treatise that low levels of estriol aftermenopause somehow foment the “villainy”of estrone and estradiol, thus inducing highrates of breast cancer in postmenopausalwomen. Citing published and unpublisheddata from Lemon et al, he reported a 37%induction of remission or arrest of growth ofmetastatic lesions in women with advancedbreast cancer. Later studies failed to confirm

Unconventional Estrogens 869

-

the hope that estriol would be an effectivebreast cancer therapy.

These facts not withstanding, alternativepharmacies in the United States are com-pounding estrogen replacement therapypills, gels, and capsules with estradiol 10%,estrone 10%, and estriol 80% (Fig. 3). Typi-cal formulations contain combinations likeestradiol 0.0125 mg, estrone 0.0125 mg, andestriol 1 mg. For this particular formulation,a common dosing regime is two pills twicedaily. The aggregate dose of estradiol there-fore is 0.5 mg. So, this triest estrogen prepa-ration in fact, is relying on estradiol, whichis present in sufficient quantity to providefunctional estrogenic benefits. Whereascompounding pharmacies making triest donot provide research on the efficacy of theseformulations, anecdotal tests in practicehave verified that women using triest mostoften have a serum estradiol level in a goodtherapeutic range. Promoters of triest prepa-rations, intuitively or discerningly, havecome to realize that estrone is probably su-perfluous in the mixture; so, many naturalestrogen proponents now advise women touse “biest” preparations, compounded withonly estradiol and estriol. Again, the jour-neyman in the duet is estradiol.

Biochemistry of EstriolEstriol differs vastly from estradiol. Unlikeestrone, estriol does not convert to estradiol.Whereas it does offer significant bioactivity,that activity is limited by the fact that it israpidly metabolized and binds fleetingly toestrogen receptors. When orally adminis-tered, in the first liver pass, not unlike estra-diol, a great deal is sulfated. But, unlike es-tradiol, 65% is converted to estrone sulfate,and 80–90% of estriol is conjugated to sul-fate and then rapidly excreted. Thus, only10–20% remains in the circulation and, ofthe total dose, only 1–2% remains in its na-tive form. Like estradiol, when administeredvaginally, the bioavailability of estriol ismarkedly increased. Like natural progester-one, administration with food greatly en-hances absorption. Even when large amountsof estriol are administered, there is no atten-dant increase in the serum levels of other es-trogens. In doses as large as 10 mg, no in-creases are seen in estrone, estradiol, or theirsulfated forms. The only detectable increaseis in estriol sulfate, which is not bioactive.21

Estimates of the potency of estriol varygreatly, ranging from one-tenth to one–one-hundredth that of estradiol.22 The estrogen

FIG. 3. Comparisons of estrone, estra-diol, and estriol.

870 TAYLOR

-

receptor affinity for estriol is only one-thirdto one-fifth that for estradiol, and estriolbinds weakly to both � and � sites, with af-finities of 14% and 21%, respectively, whencompared with the affinity of estradiol forthe same receptor-binding sites.

Though estriol is much weaker than estra-diol at some tissue sites, it appears to havethe ability to stimulate endometrial prolif-erative histologic changes identical to thoseseen with stronger estrogens.23 Estrogen andprogesterone receptors in the cytosol and es-trogen receptors in the nuclear compartmentwere measured in the endometrium, myo-metrium, and vagina of 29 postmenopausalwomen who underwent hysterectomies. Re-searchers attempted to compare the effectsof vaginal estriol (0.5 mg daily) to 17� es-tradiol (0.05 mg daily) therapy on receptorlevels. Overall, they found no clear differ-ences between vaginal estradiol and estriolwith regard to the effects on receptor levelsin vaginal and uterine tissues. On histologicexamination, similar signs of estrogenstimulation of the endometrium were seenafter estradiol and estriol.

Melamed et al24 examined the conceptthat estriol might act as a competitive an-tagonist to estradiol by looking at the effectsof estriol on receptor configuration. Theyconcluded that alone, estriol acts as a weakestrogen, but when acting in concert with es-tradiol, it appears to act as an antiestrogen.Estriol interferes with estradiol-induced,positive, cooperative biding, with receptordimerization, and with the binding of hERcompletely to the estrogen response ele-ment. The ability of estriol to act as an anti-estrogen is maximal when present in a 10-fold molar concentration in excess of theamount of estradiol. At this concentration, itdecreases estradiol binding by only 50%,but it down-regulates estradiol-dependentprotein transcription by 85%. These find-ings lend some support to those who believethat estriol can counteract some of the tissueeffects of other estrogens, but clinical stud-ies have not confirmed this supposition.There appears to be no preferential uptake

or metabolism of estriol in human tissue.Thijssen et al25 assessed the tissue/plasmagradients for estriol and estradiol and foundthat both estrogens exhibit profound uptakeby estrogen-sensitive tissues, concentratingin much greater amounts in the tissues thanin the plasma (Fig. 2).

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidationhas been associated with an increased risk ofcardiovascular disease. Protecting LDLfrom oxidation represents another mecha-nism by which estrogens may help minimizecardiovascular risk in premenopausalwomen. Shwaery et al performed an in vitrostudy in which plasma LDL was incubatedwith the three naturally occurring estrogens,estrone, estradiol, and estriol, at physiologicconcentrations. The incubated material wasthen subjected to copper ion-mediated oxi-dation to assess the degree of oxidative dam-age. Estrone and 17� estradiol both associ-ated with LDL at a five-fold to eight-foldgreater rate than estriol. The only estrogenthat conferred oxidation resistance to theLDL, however, was after formation of esterswith 17� estradiol. This suggests that only17� estradiol, not estrone or estriol, has an-tioxidant activity and protects against LDLoxidation.26 Postmenopausal women withhigh levels of endogenous estrogens, butpredominantly estrone, have a high inci-dence of cardiovascular disease. In contrast,premenopausal women have higher levels of17� estradiol and are well protected fromcardiovascular disease. This implies that thespecific loss of 17� estradiol at menopause,not the loss of estrogens per se, results in in-creased levels of atherogenic oxidized LDL.

Estriol and the EndometriumStudies performed with less than adequatedoses of estriol give the fallacious impres-sion that estriol protects the endometriumfrom hyperplasia. When estriol is adminis-tered in doses that are comparable with es-tradiol and, more frequently, to compensatefor rapid metabolic clearance, estriol in-duces endometrial hyperplasia.27 Englund28

Unconventional Estrogens 871

-

asserts that when estriol was “administeredin a way that gives prolonged elevation ofthe blood levels, is able to produce the sameeffect on the endometrium as other estro-gens.” In human studies, pretreatment andcontemporaneous treatment with estrioldoes not limit estradiol binding, nor does itblock the development of endometrial hy-perplasia. Biopsies of the endometrium inwomen treated with estriol only, estradiolonly, and the two in combination showedsimilar dose-dependent histological prolif-erative and hyperplastic changes. Padwicket al29 administered doses of estradiol (E2)or estradiol plus estriol (E3) to women for a3-month period. Both therapies providedsimilar treatment outcomes: similar degreesof vaginal bleeding, psychological symptomprofiles, reductions in night sweats, and re-lief from vaginal dryness. Endometrial hy-perplasia was found in 9 of 14 endometrialbiopsy samples, a rate of 64%. There ap-peared to be no mitigation of the tendencytoward hyperplasia with dual administrationof estradiol plus estriol. In reviewing theavailable literature on estriol and the endo-metrium, Doren30 concluded, “… data sug-gest that use of oral estriol may be associatedwith endometrial hyperplasia and endome-trial carcinoma relatively more often com-pared to sequential HRT.”

Vaginally administered estriol is gener-ally regarded as having a higher safety pro-file than oral estriol. One study reviewed en-dometrial biopsy material from 215 subjectswho were using vaginal estriol.31 The vastmajority of biopsies were performed after 6to 12 months of therapy. Only 13 of the bi-opsies were performed at 24 months. Therewere no significant abnormalities, leadingthe authors to suggest that progestational op-position is not necessary when using estriolvia the vaginal route. Nonetheless, the studyis severely limited by the fact that few sub-jects were studied after lengthy use. This is,however, consistent with larger epidemio-logical studies wherein vaginal estriol ap-pears to yield low levels, if any, of increasedrisk of endometrial carcinoma. Weiderpass

et al32 in 1999 investigated the premise thatlow-potency estrogen formulations like es-triol had few, if any, adverse effects for theendometrium. They set out to quantify thelevel of risk using Sweden’s national popu-lation-based data registry on endometrialcancer. Seven hundred eighty-nine caseswere identified in the registry and werematched with 3,368 control subjects fromthe general population. They determinedthat after 5 years, oral estriol 1 to 2 mg perday was associated with a relative risk of en-dometrial cancer equal to 3.0 (95% CI: 2.0–4.4). The relative risk increased with dura-tion of use, by 8% per year, whereas vaginaluse increased risk by 2% per year, whichwas determined to be less than statistical-ly significant. Review of these findingsprompted the New Zealand governmentto recommend, “If vaginal atrophy is theonly indication for hormone replacementtherapy, it is worth recommending vaginaltreatment as possibly a safer alternative …to oral replacement.”33 Not unexpectedly,the relative risk of endometrial hyperplasiaassociated with estriol 1 to 2 mg orally wasincreased by 8.3-fold (95% CI: 4.0–17.4)compared with never-use. The use of unop-posed CEE, in general, has been said to in-crease the risk of cancer by eight-fold to 20-fold after 10 years of use. It would appearthat the order of magnitude of risk associ-ated with estriol is not as great as that seenwith other unopposed oral estrogen thera-pies, but nonetheless, it is substantiallygreater then nil. Again, in parallel with theother types of estrogens, endometrial neo-plasms in estriol users tended to be well dif-ferentiated, with limited invasion. The riskregresses rapidly after discontinuation of es-triol.

Estriol and the BreastAs stated previously, all impressions of es-triol and its role in breast cancer derive fromobservational studies that have correlatedendogenous estriol metabolism with breastcancer risk. There are no interventional stud-

872 TAYLOR

-

ies using estriol and then comparing rates ofbreast cancer with other therapeutic estro-gens. Estriol is touted as a breast cancer pre-ventive, but in vitro studies contradict theseassertions. Estriol binds to breast cancercells and also appears to partially antagonizethe antiestrogenic effect of tamoxifen.34 Es-triol is metabolized to 16-hydroxyestrone(16-OHE1), and high endogenous levels of16-OHE1 have been suggested as a markerof risk for breast cancer. Telang in the Jour-nal of the National Cancer Institutes re-ported that 16�-hydroxyestrone (16�-OHE1) appears to initiate transformation inC57/MG mouse mammary epithelial celllines. The 16�-OHE1 increased DNA repairsynthesis by 55.2%, increased proliferativeactivity by 23.09, and increased the numberof soft agar colonies by 18-fold, all measuresbeing regarded as quantitative endpoints andmarkers of increased cellular transforma-tion. This phenomenon is not seen with es-tradiol or estrone.35 Whereas 16-OHE1 and16-hydroxyestradiol stimulate the growth ofhuman breast cancer cells as much, if notmore than, estradiol, the metabolites of es-trone and estradiol—2-hydroxyestrone (2-OHE1) and 2-hydroxyestradiols—exhibit

some ability to inhibit hormone-induced cellproliferation seen with estradiol alone whenadministered concomitantly with estradiol.High concentrations were needed, however,to produce a significant inhibition of hor-mone-induced cell proliferation.36 Theclinical significance of these findings re-mains unclear. But, these findings suggestthat 2-OHE1 and 2-hydroxyestradiols areprotective, whereas 16�-OHE1, the estriolmetabolite, is deleterious in terms of breastcancer risk.

Clinical Applicationsof EstriolIn Europe and other regions, estriol is usedas HRT in oral, topical, and intravaginalpreparations, often in combination withother estrogens, most commonly only as ashort-term topical in treatment of urogenitalatrophy before urogenital surgery (Table 3and Fig. 4 show lists of typical products andprescribing information). Clearly, estriolachieves excellent results as a topical thera-peutic. It is regarded by many in Europeas the estrogen of choice for atrophy, andtrials of newer vaginal estrogens usually

TABLE 3. Estriol: Branded Products in Europe, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand

Brand Form Manufacturer

Synapause Estriol succinate 2-mg tablet OrganonSynapause Forte Estriol succinate 4-mg tablet OrganonSynapause Vaginal cream 0.1% OrganonOvestin 1- and 2-mg tablets orally Organon

Pessaries 500 µg (ovula) OrganonVaginal cream 0.1% Organon

Hormonin Estriol 0.27 mg/estradiol 0.6 mg/estrone 1.4 mg Shire/ScheringOrtho Gynest 0.1% cream Janssen CilagOrtho Gynest D 0.5-mg pessary Janssen CilagCyclo-Menorette Estradiol 1 mg, Estriol 2 mg, levonorgestrel 0.25 mg WyethEstrofem Estradiol 2 mg, Estriol 1-mg tablet Novo NordiskEstrofem Forte Estradiol 4 mg, Estriol 2-mg tablet Novo NordiskMenoflush Pharm. Ent.Trisequens 12 tablets, oestradiol 2 mg, oestriol 1 mg; 10 tablets,

oestradiol 2 mg, oestriol 1 mg, norethisterone acetate1 mg; 6 tablets oestradiol 1 mg, oestriol 0.5 mg

Novo Nordisk

Trisequens Forte 12 tablets, oestradiol 4 mg, oestriol 2 mg; 10 tablets,oestriol 4 mg, oestriol 2 mg, norethisterone acetate 1mg; 6 tablets, oestradiol 1 mg, oestriol 0.5 mg

Novo Nordisk

Unconventional Estrogens 873

-

FIG. 4. Excerpts from prescribing information from European estriol products. Accessed at: http://www.organon.com/home_index.html?MedicalProfessional.

874 TAYLOR

-

compare the new agent with estriol as thecurrent treatment of choice. Two hundredfifty-one postmenopausal women reportingat least one bothersome lower urinary tractsymptom were treated with an estradiol-releasing ring or with estriol pessaries 0.5mg every other day for 24 weeks.37 The ringand pessaries were equally effective in re-ducing urgency, frequency, nocturia, dys-uria, stress incontinence, and urge inconti-nence. Dysuria was alleviated in 76% versus67%. This difference is not statistically sig-nificant. Patient satisfaction was muchhigher for those using the ring. Sixty percentrated the ring as excellent whereas only 14%rated pessaries as excellent (P < 0.0001). Asimilar study of vaginal tablets again usedestriol “vagitories” as the control treatment.Ninety-six postmenopausal women withsymptoms of atrophic vaginitis were treatedfor 24 weeks with either estradiol tablets orestriol ovules. Both medications were useddaily for 2 weeks and then twice weeklythereafter.38 Only three women in the tabletgroup (6%) reported urinary leakage; nonerequired sanitary protection. In contrast, 31(65%) of the ovule users reported leakageand 14 (29%) required sanitary pads. Pa-tients rated the tablets superior in terms ofhygiene and ease of use. The tablets in-creased endometrial thickness more than theestriol ovules—1.1 mm versus 0.5 mm—during the first 2 weeks of the study, but re-turned to baseline levels when the use wasreduced to twice weekly. Studies of this sortand new drug developments may be leadingto the obsolescence of estriol for its mostcommon indication.

Note that pharmaceutical companies inEurope, South Africa, and Australia produceand market oral HRT preparations contain-ing both estradiol and estriol, though newerformulations have discontinued the estriolcomponent. Trisequens (Novo Nordisk A/S,Copenhagen, Denmark), an estradiol plusestriol preparation still marketed in someparts of the world, has been reformulated inEurope. The newest “domestic” versionmade by Novo Nordisk in Netherlands only

contains estradiol. There has been recogni-tion that the estriol has not added value in theHRT mix. Hart39 conducted a long-term trialof continuous combined hormone replace-ment, initially randomizing subjects to 2 mg17� estradiol and 1 mg norethisterone (nor-ethindrone) acetate administered once dailywith or without 1 mg estriol. No differenceswere observed during the initial 1-year trialbetween the groups with or without estriol.When the project was extended to a 9-yearopen-label study, estriol was eliminatedfrom the treatment protocol, and all womenwere administered estradiol alone.

Estriol’s clinical performance has beenless than stunning. Estriol does show goodeffects in the treatment of vasomotor symp-toms, sleep disturbances, night sweats, andother “vegetative” symptoms of menopause.Yang40 (Taiwan) reported that estriol waseffective in alleviating symptoms of the cli-macteric, but it did not prevent bone loss.Takahashi41 reported the experienceof 68 postmenopausal Japanese women ad-ministered estriol, 2 mg per day, daily for12 months. Oral estriol therapy improvedmaturation index and greatly decreasedhot flushes, night sweats, and insomnia.Whereas estriol did evidence an impact onthe hypothalamus by lowered serumfollicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizinghormone concentrations, no changes werenoted in lipids, bone mineral density(BMD), liver function, or blood pressures.Vaginal bleeding occurred in 14.3% of thewomen with an intact uterus. Similarly,Minaguchi42 reported statistically signifi-cant decrease in Kupperman’s Index withestriol 2 mg daily. The same study, in a Japa-nese population, demonstrated an increasein BMD of 1.79% in 50 weeks in individualspreselected to have a baseline density morethan 10% less than peak levels.

The studies of the efficacy of estriol intreatment of osteoporosis have shown mixresults. Itio43 studied 64 healthy, earlymenopausal women and treated them for 24months, either with estradiol plus estriol 2.0mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5

Unconventional Estrogens 875

-

mg (n = 15), CEE 0.625 mg plus 2.5 mg me-droxyprogesterone acetate (n = 19), 1.0 µg1-�-hydroxyvitamin D3 daily (n = 13), or1.8 g calcium lactate containing 250 mg ofelemental calcium daily (n = 17). Bone min-eral density at the third lumbar vertebra wasmeasure with quantitative computed tomog-raphy, and bone markers in serum includingosteocalcin and total alkaline phosphatase,urinary calcium-to-creatinine ratio, and hy-droxyproline-to-creatine ratio were evalu-ated at baseline and every 6 months for the 2years of the study. The nonestrogen groupslost 12–14% of BMD during the 24-monthstudy period. The estriol treatment grouplost −4.1 (±4.8%), and the CEE group hadless than 1% loss (−0.9 [±3.2%]) Serummarkers of bone turnover decreased or re-mained unchanged in the estradiol plus es-triol and CEE groups, but increased in otherarms. Estriol produced less uterine bleedingthan CEE. Estriol incurred 2.4 (±4.2) days ofbleeding versus 13.1 (±14.8 ) days per per-son per year (P < 0.001) for CEE. The au-thors felt that the outcomes seen with estrioland CEE were comparable; however, if thestudy period were more prolonged, the 2%loss per year seen with estriol might wellprove to be significantly worse then thatseen with CEE.

In a study of a percutaneous estradiol geland its effects on BMD, women were admin-istered oral estriol 2 mg per day as a con-trol.44 The study is an exception in one re-gard: it included measures of BMD of theproximal femur in addition to the more com-mon measure of BMD of the lumbar spine.Women were studied every 3 months bydual-energy x-ray absorptiometry for 2years. In the 21 patients using estriol, bothsites lost BMD. The percutaneous estradiol-treated group gained 1.2 per year in the lum-bar spine, but had no significant change atproximal femur. Estriol was judged to be atreatment failure. This study, performed inEurope, contradicts the outcomes seen instudies performed in Asian women.

Interestingly, the dose of oral estriol rec-ommended in Europe, Australia, and South

Africa is often much greater than the dosesused in Asia. European pharmaceutical es-triol tablets contain 2 or 4 mg, double thedoses used in Japan. Perhaps, because oftheir body mass, previous BMD levels, orsome other variable, European women ap-pear to be less responsive to estriol thanAsian women. Remember that women withthe worst BMD levels have the greatest re-sponse to estrogen, and they may even re-spond to extremely low levels. Naessen45

found that women older than age 60 with noprevious estrogen treatment gained 2.1%in the BMD of the forearm in 6 months, ver-sus a 2.7% decrease in controls, whereas be-ing treated with a vaginal estrogen ring pro-vided just 7.5 µg per day. Markers of boneturnover decreased significantly. Alkalinephosphate decreased 8%, bone-specific al-kaline phosphatase decreased 14%, and os-teocalcin decreased 9%. Clearly, minusculedoses of estrogen can be remarkably effec-tive in individuals with severe hypoestro-genemia.

The lipid effects of estriol differ fromother estrogens and support the concept thatestriol is weaker. Itoi et al performed a2-year trial of estriol 2 mg plus medroxypro-gesterone acetate 2.5 mg versus CEE 0.625mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5mg versus placebo, and found that total cho-lesterol decreased in the estriol group, andthe CEE group evidenced no change. Pla-cebo controls demonstrated a 5.4% increasein total cholesterol. High-density lipopro-tein cholesterol increased 10.7% in the CEEand 3.8% in the estradiol plus estriol groups,but decreased in the controls by 3.6%. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was de-creased 11.4% in the CEE group, remainedunchanged in the estradiol plus estriolgroup, and increased 11.8% in controls. Tri-glycerides decreased a modest 6.7% in theestradiol plus estriol subjects, remainedstable in controls, and, as expected, in-creased 17.6% in the CEE users. Thus, theoverall profiling of estriol indicates minimalimpact on lipids.46 The authors suggest thatestriol might be a good choice for women

876 TAYLOR

-

prone to hypertriglyceridemia. That conclu-sion seems reasonable.

ConclusionsWhen examining estriol as a menopausal in-tervention, one may view the glass as eitherhalf empty or half full. Head,47 in her reviewof estriol, concluded:

“While conventional hormone replace-ment therapy provides certain benefits, it isnot without significant risks. Estriol hasbeen found to provide some of the protectionwithout the risks associated with strongerestrogens. Depending upon the situation, es-triol may exert either agonistic or antagonis-tic effects on estrogen. Estriol appears to beeffective at controlling symptoms of meno-pause, including hot flashes, insomnia, vagi-nal dryness, and frequent urinary tract infec-tions. Results of research on its bone–density-maintaining effects have beencontradictory, with the most promising re-sults coming from Japanese studies. Estri-ol’s effect on cardiac risk factors has alsobeen somewhat equivocal; however, unlikeconventional estrogen prescriptions, it doesnot seem to contribute to hypertension. Al-though estriol appears to be much safer thanestrone or estradiol, its continuous use inhigh doses may have a stimulatory effect onboth breast and endometrial tissue.”

This is a generous and upbeat view of es-triol. Since 1998 (when that statement waspublished), the new information has sur-faced regarding the endometrial risks of es-triol. Moreover, the work performed in Ja-pan may not be applicable to other popula-tions. In his excellent study in 2000,Takahashi concluded, “Estriol is a safe andeffective alternative for relieving climac-teric symptoms in postmenopausal Japanesewomen.”42 Emphasis in that statementshould be on “Japanese.” Perhaps that au-thor is subtlety suggesting that the resultscannot be extrapolated to other populations.I would also insert a similar cautionary note.

The most that can be said is that estriol isno worse than the currently available formu-

lations using estrone and estradiol in termsof overt risks. It appears to offer good symp-tom control. But, it is clearly no better thanestradiol or estrone. Triest and biest prepa-rations do contain sufficient amounts of es-tradiol to provide all the therapeutic benefitsof conventional HRT, and patients usingthem clearly will have good symptom relief.Unconventional, compounded estrogens donot appear to be worth the extra cost and ef-fort they exact, but they do represent an ad-ditional therapeutic option for women whocannot tolerate conventional prescription es-trogens.

SummaryThe use of estriol alone or with other estro-gen does not provide documented safety, se-curity, or protection for the breast or endo-metrium.

There is no clinical or epidemiologicaldocumentation for the claim that estriol willprotect against breast cancer. Estriol clearlyhas the potential to up-regulate estrogen re-ceptors in the endometrium, and to stimulatethe endometrium. Estriol is associated withan increased risk of endometrial cancer andendometrial hyperplasia when administeredorally in doses from 1 to 2 mg per day. Itdoes not “block” the endometrial prolifera-tive effects of other estrogens. Oral estriol,used any longer than short-term and not un-like other estrogens, should be used in com-bination with progestational therapy to ob-viate the risk of hyperplasia and carcinomaassociated with the use of unopposed estro-gens. The bone effects of estriol appear to bemilder than those of estradiol or estrone. Es-triol has minimal lipid effects. Whereas es-triol does not improve total cholesterol,high-density lipoprotein, or LDL, it does notincrease triglycerides like other oral estro-gens, and it may be a safer alternative forwomen prone to hypertriglyceridemia.Transdermal estradiol is also a safer optionfor women with this type of lipid disorder.

Unconventional Estrogens 877

-

References1. Cauley JA, Seeley DG, Ensrud K, et al. Es-

trogen replacement therapy and fractures inolder women. Study of Osteoporotic. Frac-tures Research Group. Ann Intern Med.1995;122(1):9–16.

2. Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Random-ized trial of estrogen plus progestin for sec-ondary prevention of coronary heart diseasein postmenopausal women. Heart andEstrogen/progestin Replacement Study(HERS) Research Group. JAMA.1998;280(7):605–613.

3. Mosca L, Collins P, Herrington DM, et al.Hormone replacement therapy and cardio-vascular disease: A statement for healthcareprofessionals from the American Heart As-sociation. Circulation. 2001;104:499–503.

4. Seaman B. The Doctors’ Case Against thePill. New York: P. H. Wyden, 1969.

5. Seaman B, Seaman G. Women and the Cri-sis in Sex Hormones. New York: RawsonAssociates, 1977.

6. Love S, Lindsey K. Dr. Susan Love’s Hor-mone Book: Making Informed ChoicesAbout Menopause. New York: RandomHouse, 1997.

7. Faulkner DL, Young C, Hutchins D, et al.Patient noncompliance with hormone re-placement therapy: a nationwide estimateusing a large prescription claims database.Menopause. 1998;5(4):226–229.

8. Berman RS, Epstein RS, Lydick E . Riskfactors associated with women’s compli-ance with estrogen replacement therapy. JWomens Health. 1997;6(2):219–226.

9. Jones KP. Estrogens and progestins: what touse and how to use it. Clin Obstet Gyne-col.1992;35(4):871–883.

10. Cummings SR, Browner WS, Bauer D, et al.Endogenous hormones and the risk of hipand vertebral fractures among older women.Study of Osteoporotic Fractures ResearchGroup [see comments]. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:733–738.

11. Michaelsson K, Baron JA, Farahmand BY,et al. Hormone replacement therapy and riskof hip fracture: population based case-control study. The Swedish Hip FractureStudy Group. BMJ. 1998;316(7148):1858–1863.

12. Community Drug web site. Available at: http:

//www.communitydrug.com/NHRT/nhrt4.cfm. Accessed March 2000.

13. Dickinson LE, MacMahon B, Cole P, et al.Estrogen profiles of Oriental and Caucasianwomen in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:1211–1213.

14. Potischman N, Hoover RN, Brinton LA, etal. Case-control study of endogenous ste-roid hormones and endometrial cancer. JNatl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(16):1127–1135.

15. Key TJ, Wang DY, Brown JB, et al. A pro-spective study of urinary oestrogen excre-tion and breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer.1996;73(12):1615–1619.

16. Lemon HM. Estriol prevention of mammarycarcinoma induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz-anthracene and procarbazine. Cancer Res.1975;35(5):1341–1353.

17. Lemon HM. Pathophysiologic consider-ations in the treatment of menopausal pa-tients with oestrogens; the role of oestriol inthe prevention of mammary carcinoma.Acta Endocrinol Suppl (Copenhagen).1980;233:17–27.

18. Sedransk N, Kelley RM, Ansfield FJ, et al.Diethylstilbestrol: recommended dosagesfor different categories of breast cancer pa-tients. Report of the Cooperative BreastCancer Group. JAMA. 1977;237(19):2079–2078R.

19. Holzer D, Harvey HA, Lipton A. Compari-son of DES vs DES + chlorambucil inwomen with first recurrence of breast can-cer. J Surg Oncol. 1979;12(1):1–9.

20. Follingstad AH. Estriol: The Forgotten Es-trogen? JAMA. 1978;239:29–30.

21. Blohm PL, Hammond CB. Oral estrogen re-placement. In: Adashi EY, Rock J, Eds. Re-productive Endocrinology, Surgery, andTechnology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996.

22. Kuiper GGJM, Carlson B, Grandien K, et al.Comparison of the ligand binding specific-ity and transcript distribution of estrogen re-ceptors a and b. Endocrinology. 1997;138:863–870.

23. van Haaften M, Donker GH, Sie-Go DM, etal. Biochemical and histological effects ofvaginal estriol and estradiol applications onthe endometrium, myometrium and vaginaof postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endo-crinol. 1997;11(3):175–185.

24. Melamed M, Castano E, Notides AC, et al.

878 TAYLOR

-

Molecular and kinetic basis for the mixedagonist/antagonist activity of estriol. MolEndocrinol. 1997;11(12):1868–1878.

25. Thijssen JH, Wiegerninck, MA, DonkerGH, et al. Uptake and metabolism of oestriolin human target tissues. J Steroid Biochem.1984;20(4B):955–958.

26. Shwaery GT, Vita JA, Keaney JFJ. Antioxi-dant protection of LDL by physiologic con-centrations of estrogens is specific for 17-beta-estradiol. Atherosclerosis. 1998;138:255–262.

27. Whitehead MI. Prevention of endometrialabnormalities. Acta Obstet Gynecol ScandSuppl. 1986;134:81–91.

28. Englund DE, Johansson ED. Endometrialeffect of oral estriol treatment in postmeno-pausal women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand.1980;59(5):449–451.

29. Padwick ML, Siddle NC, Lane G, et al. Oes-triol with oestradiol veses Oestradiol alone:a comparison of endometrial, symptomaticand psychological effects. Br J Obstet Gyn-aecol. 1986;93:606–612.

30. Doren M. Hormone replacement regimensand bleeding. Maturitas. 2000;34(S1):S17–S23.

31. Vooijs GP, Geurts TB. Review of the endo-metrial safety during intravaginal treatmentwith estriol. Eur J Obstet Gynecol ReprodBiol. 1995;62:101–106.

32. Weiderpass E, Baron JA, Adami HO, et al.Low-potency oestrogen and risk of endome-trial cancer: a case-control study. Lancet.1999;353(9167):1824–1828.

33. Med Safe web site. Available at: http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/Profs/Safety/oest.htm#1.Accessed March 2000.

34. Lippman M, Monaco ME, Bolan G. Effectsof estrone, estradiol, and estriol on hor-mone-responsive human breast cancer inlong-term tissue culture. Cancer Res. 1977;37:1901–1907.

35. Telang NT, Suto A, Wong GY, et al. Induc-tion by estrogen metabolite 16 alpha-hydroxyestrone of genotoxic damage andaberrant proliferation in mouse mammaryepithelial cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84(8):634–638.

36. Gupta M, McDougal A, Safe S. Estrogenicand antiestrogenic activities of 16alpha- and2-hydroxy metabolites of 17beta-estradiolin MCF-7 and T47D human breast cancer

cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;67(5–6):413–419.

37. Lose G, Englev E. Oestradiol-releasingvaginal ring versus oestriol vaginal pessa-ries in the treatment of bothersome lowerurinary tract symptoms. Br J Obstet Gynae-col. 2000;107(8):1029–1034.

38. Dugal R, Hesla K, Sordal T, et al. Compari-son of usefulness of estradiol vaginal tabletsand estriol vagitories for treatment of vagi-nal atrophy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand.2000;79(4):293–297.

39. Hart DM, Farish E, Fletcher CD, et al. Long-term effects of continuous combined HRTon bone turnover and lipid metabolism inpostmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int.1998;8(4):326–332.

40. Yang TS, Tsan SH, Chang SP, et al. Efficacyand safety of estriol replacement therapy forclimacteric women. Chung Hua I Hsueh TsaChih (Taipei). 1995;55(5):386–391.

41. Takahashi K, Manabe A, Okada M, et al. Ef-ficacy and safety of oral estriol for manag-ing postmenopausal symptoms. Maturitas.2000;15;34(2):169–177.

42. Minaguchi H, Uemura T, Shirasu K, et al.Effect of estriol on bone loss in postmeno-pausal Japanese women: a multicenter pro-spective open study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res.1996;22(3):259–265.

43. Itoi H, Minakami H, Sato I. Comparison ofthe long-term effects of oral estriol with theeffects of conjugated estrogen, 1-alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3 and calcium lactate onvertebral bone loss in early menopausalwomen. Maturitas. 1997;28(1):11–17.

44. Devogelaer JP, Lecart C, Dupret P, et al. Thelong-term effects of percutaneous estradiolon bone loss and bone metabolism in post-menopausal hysterectomized women. Ma-turitas. 1998;28(3):243–249.

45. Naessen T, Berglund L, Ulmsten U. Boneloss in elderly women prevented by ultralowdoses of parenteral 17 beta-estradiol. Am JObstet Gynecol. 1997;177(1):115–119.

46. Itoi H, Minakami H, Iwasaki R, et al. Com-parison of the long-term effects of oral es-triol with the effects of conjugated estrogenon serum lipid profile in early menopausalwomen. Maturitas. 2000;36(3):217–222.

47. Head KA. Estriol: safety and efficacy. Al-tern Med Rev. 1998;3(2):101–113.

Unconventional Estrogens 879