tuymans interview

-

Upload

foggynotion -

Category

Documents

-

view

184 -

download

0

Transcript of tuymans interview

Luc Tuymanson fighting the literal and mistrusting imagesInterview by YASMINE VAN PEE Portraits by ALBRECHT FUCHS

Next spring Luc Tuymans is turning 50. In lieu of a midlife crisis, he is preparing for two major surveys of hiswork in 2008, at Haus der Kunst, Munich, and the Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio. Perhaps inanticipation of those shows, this past summer he organized a smaller, more personal exhibition in his hometownat the Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp. "I Don't Get It" featured etchings, lithographs, source Polaroids,films, and even a designated smoking room where footage of his murals screened-but no paintings. ModernPainters asked his compatriot Yasmine Van Pee to talk with Tuymans in their native Flemish and translate intoEnglish his candid sentiments on politics, process, his curatorial projects, and his critics.

66 MODERN PAINTERS I OCTOBER 2007

YASMINE VAN PEE: You've just made a substantial institution. They were donated with an archivaldonation of your Polaroids to the Museum of function in mind. The timing relates to my exhibi-Contemporary Art Antwerp [MUHKA]. Why did you tion at MUHKA, "I Don't Get It," but that is concep-choose to do that, and why now? tualized more broadly than it would be if it wereLUC TUYMANS: Well, because Polaroids are work- solely centered on the Polaroids. Its concept clustersing materials for me. They can't really be sold, at around the ephemeral. As you know, no paintingsleast they aren't intended to be, so I thought it are shown. Instead the show includes prints andwould be fitting that they be put in the care of an multiples I made to raise funds for several nonprof-

its, and also more-unique projects using print asmedium-lithographs, a series of six-color etchingscalled "The Temple" [1996]. There's also a smokingroom, which I created so that visitors can smokeinside the museum, rather like those designatedrooms in airports. Inside that space there's docu-mentary footage of several of the murals I madewhich have now been destroyed.

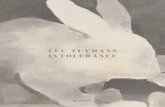

I tried to create chains of recurring images in theshow, not so much concerning myself with the ideaof being straightforwardly didactic, but rathergiving viewers some kind of a way into the processof painting.YVP: It struck me that "I Don't Get It" also seemedto allow for a certain literalness. I mean, being ableto see for example the Polaroid you used to makeDrumset [1998] and compare it to a print version ofthe work itself seems to run counter to the moreoblique nature of most of your previous work.LT: Drumset's the most literal example from theshow. It's a monochrome, strongly abstracted, andplays more off the color nuances of the Polaroid, allthe hues tending towards violet. There are of courseother paintings that can be directly related to thePolaroids shown, because I use them as workingmaterials. There's a work in the exhibition referenc-ing that working process. First I built a scale modelof which a Polaroid was taken, then others weretaken of that image, and then I made the paintingbased on those later Polaroids.

The thing I find fascinating about Polaroids is thatthey are akin to the way I paint: I start off with thelightest color, then work up to higher contrasts,and in a way Polaroids do the same. A Polaroid isnot really a photograph, you see, it's a liquid inwhich the image appears. One of the attractivethings about them is that they are, in essence, tiedto an extreme randomness; you never know exactlyhow one is going to develop, whereas with photog-raphy you retain at least some control. And it's pre-cisely this inherent element of loss and possiblefailure that I value.YVP: Presumably filmmaking also lends itself to"possible failure." Most people aren't familiar withyour film work-I know I wasn't before I saw Feud'artifice [1982]. Could you talk more about that?LT: Yes. Its title, which means "firework," again

68 MODERN PAINTERSI OCTOBER2007

PREVIOUS SPREADLUCTUYMANS IN HIS STUDIOIN ANTWERP, AUGUST2007PHOTO ALTIRUCHT FUCHý

FACING PAGEDRUMSET, 1998OILON CANVAS, 76 5/8X48 IN((oU RT ESy DAVRiDZWlTlR N EW YORKA ND7 IENO XGALLERY ANTWERP

STUDY FOR DRUMSET, 1998POLAROID, 31/8X 3 INPH OTO MKIIAEITANG

THIS PAGESTUDIO, 2002OILON CANVAS, 811/8 X1181/8 IN(TE VIDA ZAVI VNER, NEWYORK,A•N[)ZNOX GAT LERY, ANTWERP

THREE STUDIES FORSTUDIO,2002POLAROIDS, EACH 31/8X3 IN

I(TURTETY UIfT ARUSFANWEMiiSEUMVANt[{NDLAD-,ý1 KUNST ANT[WERPEN (MUHKA)A N TERP UI

erefers to the ephemeral. It was shot on 16 mm filmand documented a performance which was in itselfthe culmination of two or three years of working inSuper 8. It was filmed in collaboration with a friendwho's an actor. We created a sort of tableau vivantinside the Royal Galleries [a covered walkway bor-dered by a row of columns] of the Thermenpaleis,right on the beach in Ostend, which was a publicperformance I think we even organized breakfastafterwards. The whole event lasted a little over halfan hour and was timed to coincide with the sunrise.it was a collage of different elements: my own texts,fiagments of writing by Joseph Conrad, FernandoPessoa, Michel de Chelderode, and others, but alsofilm footage shot by my friend and me, which wasprojected on a screen in the background. Everythingwas condensed so that it had a theatrical feel. Theperformance was explicitly conceptualized to con-cretize, then disappear again. Feu d'artifice containsa lot of influences that I feel might provide a radicalway of rethinking my work now.YVP: Thinking of Feu d'artifce in relation to a shorterfilm you made more recently, one you shot of a de-veloping Polaroid, might it be a medium withwhich you'd like to start working again?LT: The developing Polaroid was more an idea I wasattracted to on a pragmatic level, to underscore theway an image appears, so I don't really consider ita filn piece. It's different. It's more like an object.Film is of course something that's still in my gut,and maybe that will concretize at some point in aproject again, but not in the immediate future, be-cause film and painting are hard to combine. Bothare very intense, demanding activities.YVP: What exactly do you mean by "hard to

combine"?LT: Well, they are more or less similar. Some mightargue that they are diametrically opposed, sinceone is a moving image and the other is still, butthat's about the only really significant difference.Painting is the process of manufacturing an image,of approaching it, and filming is that too. Both areunlike making a photograph, where you are in themoment. You have much more time when you'reconsidering and approaching an image than you dowith photography, which is why I often say I couldnever be a photographer. Because of all this, film-

making and painting's interference with one an-other becomes too strong, so I couldn't pursue both,with the two different types of attention they re-

quire, at the moment.YVP: There are some obvious relationships betweenyour work and film, but I'm interested in hearingmore about the role certain concrete cinematogra-phers have played in your thinking, and about theaffinities between your work and films by Hans-Jiirgen Syberberg and Peter Weiss.LT: Syberberg was someone I encountered in 1978first by reading the script of Hitler: ein Film ausDeutschlond [19771, then seeing the film on threeconsecutive nights on television-a black-andwhite one if I'm not mistaken. The fascinatingthing about him is the way in which he, in a mannerof speaking, dreams history. The way he approachedthe war, and in particular Nazism, was very riskyfor a German at the time. He was the first Germanto imagine what it could mean to step into the mindof Hitler, without just crudely picturing him. Itmay seem a bit dated now, but it's important be-

cause he starts to unravel the whole of German fas-cism from a cultural standpoint. A lot of what I wasthinking about at the time ran parallel to whatSyberberg was working through in his movies.

Weiss is an entirely different story. Those worksare short films, and there the affinities lie more onthe formal level of making images, the often awk-ward and impossible angles that are taken, and es-pecially the way the image is often masked orcloaked, even though he's dealing with movingimages. Also how he succeeds in marrying themwith a type of immobility-which was already vis-ible in his earlier prints and paintings, of course.You can really see a painter at work there, which isalso the case with Eraserhead [1977], by David Lynch,who I wasn't surprised to learn also started out asan artist before moving on to film.YVP: Weiss often makes use of a type of Chinese boxsystem in his works, putting narratives within nar-ratives, which is presumably something you canrelate to.LT: Yes. It is a way to be able to work on the level of

OCTOBER20071 MODERN PAINTERS 69

-0. 00W

Ii C P,) \ /, " 1r _

understatement, which I think is very importantwithin the visual. It is something that, because ofan oversaturation of images that already circulatewithin the media, and a media that now oftenlargely deals with itself, is increasingly rare.YVP: I wonder if the way Chris Marker approachesmemory and history through his cinematographyinterests you. For example, are the images of matingmonkeys in your series "Exhibit" a direct referenceto his Sanssoleil [1982]?LT: Yes, definitely. I think Marker was one of themost important cinematographers of his time; infact he's still active today. And in a strange waythere are links that can be made, albeit indirectly,

with my work and the art films from the 1960s ofwhich he was one of the main proponents. It sad-dened me to read of Michelangelo Antonioni's

I~ i-l -

death, as he was one of my favorite filmmakers be-cause of his treatment of time and history, wherenarrative elements fold in on themselves, are turnedupside down, and are contextualized through pro-cesses that work on an explicitly visual level.

Of course there were certain social motivationsbehind Marker's work that I find intriguing. Alsothe duration of his films and the endurance theyrequired are fascinating to me. His work deals inlarge part with the question of how to rememberthings in and through film in a particular manner.Syberberg grapples with how to reimagine historyin an ethical way and how to be able to dream it. Onthe other hand his treatment was felt at the time tobe transgressive precisely because he used real docu-mentary evidence to shape that reimagining.Marker got to the point where he displayed a certain

wariness towards existing images. This is true ofthe images I work with myself, and, in the bestcases, hopefully leads the viewer to a questioningof and healthy distrust towards them.YVP: It seems that in your own painterly practicethe act of forgetting is a very important element.I'm thinking in particular of how you've talkedabout the "memory-free zone between conceptionand execution."LT: Of course an image is never something that justfalls out of the sky; its choice is always directed byexisting elements. Those elements are moreovernever simply what they are, by which I mean theycan take on several layers of meaning and distortthemselves in the process. Then you get, well, not

really a problem, but you do become faced with thenecessity of making choices. What's important inthat process, and what I aim for, is doing so in asingular manner-to focus, which is where the actof painting becomes important. You shouldn'tforget that painting is a very physical medium thatalways leaves traces of how something was painted.By the way, I started out as a very gestural, fairlyimpulsive painter using a dry color palette, which

70 KA(-F)FPRN PAINITFRP I OCTGRFR P)nn7

FACING PAGEFEU D'ARTIFICE (FIREWORK),1982FILM STILLCOUR ESYT EEARTISTAND MUSEU MVAN HEDENDAAGSE KUNST ANTWERPEN(MUHKA) ANTWERP

THIS PAGE, CLOCKWISEFROM TOP LEFTSTUDY FOR THE PARC, 2005POLAROID, 31/8 X3 INC RTESYTHE ATIST ANUD MUSEUMVAN HEDENDAAGSE KUNSTANTWERPENWMUHKA) ANTWERP

CHALK, 2000OILON CANVAS,281/2X241/4 INCOU ESY DAVID ZWIRN ER, NEUYORK,ANDZENO X ALLE RY ANTWERP

THE PARC, 2005OIL ON CANVAS, 63 X 7X 2 INCOURTESY DAVIDZWIRN ER N EWYORKAND ZENO XGALERYA ANTWERP

OCTOBER20071 MODERN PAINTERS71

BODY, 1990OILON CANVAS,191/4X133/4 INCOURTESYDAVID ZWIRNER, NEWAYORIAND ZENOXGALLERY ANTWERP

EASTER, 2006OIL ON CANVAS,50 3/8 X 701/2 1NCOURTE DAVID ZWIRNER NEWYOAKAND Z NOXGALLERY, ANTWE RP

P

I reduced precisely because of all those layers ofmeaning, and also to create sufficient distance fromwhat I wanted to express with painting. Now I'vede-emphasized the gestural brushstroke and triednot to cultivate a particular style. Of course after agood 400 paintings you accumulate something akinto a style, but that is not something you consciouslyaim for. It's more something you need to reduce tothe level of habit. That habit is essential, however,essential in its integrity.YVP: In that context, does the recurring critique ofyour work as having a certain style that is said tofunction somewhat akin to a"Photoshop filter"-inthe sense that it can be applied to any subject, withthe effect of equalizing all subjects-particularlybother you?LT: It's a very literal critique that stems from igno-rance. I'm someone who takes an extremely longtime before even starting to paint. The choice ofimages, the content of those images, is of essentialimportance for me in terms of meaning. Which isprobably the reason why it may seem I can paint justabout anything with relative ease. Now, you canindeed paint anything, so this criticism is alreadya tad odd to start with. At the same time, exactlybecause you can make an image about anything, Iam making a choice by painting the things I paint,and that choice is always determinant. It deter-mines the way the picture shows itself, and evenpragmatically the way it is concretely made. It's atype of critique that emerges from a consciously in-flated discourse that juxtaposes new media with avery archaic understanding of painting. But that isnot my discourse.YVP: On the contrary, it often feels like paintingsof yours that depict subjects that could be classified

as banal sometimes seem more horrific than theactual horrors you paint.LT: What do you mean by "actual horrors"?YVP: Body [1990], for instance...LT: Body is a doll I used to have as a child, whichopens up with a zipper and could be stuffed to givethe body volume. So that is not something I wouldclassify as horrific. When I first started showing my

work, many interpreted it as intimate, withdrawn,introverted, and poetic, none of which it was. Thenthere was a period when I was accused of nostalgia,

which was not accurate either, because nostalgia inmy eyes is actually truly a notion related to horror.After that came more perfidious readings, empha-sizing negative elements-like the sinister, thesurgical, the distanced-which again weren't ex-

planations of the images.The latest critique is that I take a moralizing

stance towards images that have to do with power.I admit power is something that fascinates me-notto have power but to look at the apparatus behindit, how images could exert power, how they couldhave a certain impact-but that's not moralizing,rather it's an attempt to underscore a of meanings.It's never an accusatory, pointed finger.

The main, enduring criticism of my work is thatI have by now already said too much about it. Whatstarted as an openness and willingness to accom-modate a need for more information has beenturned into a type of pedantic egocentrism on mypart. That is the type of retrograde critique thatsprings from the inability of some to grant any im-portance to the work itself, which is of course anopinion they're more than entitled to. What is nottheir right, however, is to narrow all of that into avery personal critique that has nothing to do withmy work anymore.It's fair to demand a certain level of abstraction,

which appears to be very difficult when everythingelse is becoming increasingly literal; that much isclear. But then that's my personal fight in a worldthat is ever more antiseptic, and in which imagesonly refer to other images, and the media to themedia, and in which my pictures end up in this ter-rifying cycle.YVP: Disregarding a type of criticism that referseverything back to you personally, it seems thatsome of your paintings nonetheless contain a verypoignant moral critique. I'm thinking of MwanaKitoko (Beautiful White Man) and the way it was in-stalled with your other works [in an exhibition ofthe same title] in the Belgian pavilion at the 2001Venice Biennale.LT: "Mwana Kitoko" was not an exhibition that in-tended to point fingers. Because of a confluence ofcoincidences, it happened to be shown in the yearof the Lumumba commission [appointed to investi-gate the direct involvement of the Belgian govern-ment in the murder in 1961 of Patrice Lumumba,the first democratically elected prime minister ofCongo]. About a month after the Biennale closed, ata concluding ceremony which I was invited toattend, the commission announced that the Belgiangovernment should issue an official apology, whichthey duly did. The Royal House did not.

For me the whole experience was a very elemen-tary situation of touching on something, bringingit to people's attention, and visualizing it in a dif-ferent way. That has of course already been done indocumentaries; there's enough factual materialdealing with this incident, but there were hardlyany paintings about it. By transforming it througha painting into an anachronism, the subject becameaestheticized in a way that drew criticism, from the

French especially, that certain political contentshould not be directly expressed in paintings, which

72 MODERN PAINTERSI OCTOBER 2007

N, 40

AMIRROR, 20050 LON CANVAS, 551/2X 01/2X11/2 INCOURT YSDAVIDZWIRNER N EWYORKAND[ EANOX [ALLERY, ANTWERP

I thought was strange coming from a country thatproduced the likes of Manet and his Execution ofMaximilian 11867-681. So for the first time this pavil-ion for a country that's normally seen as puny andinsignificant was able to generate political content.I still feel it's not possible to simply load any workof art with a particular political meaning; this wasan important moment in which something wasachieved through my work, but also because ofevents going on around it. I could just as well havepresented a nice anthology of 20 years of paintingor something like that, but on this occasion, loca-tion, context, and work fitted well through theirmutual feedback.YVP: I was interested in the way you used the ideaof the documentary in your reinterpretation of his-tory painting in that show. if I'm not mistaken,certain paintings at Venice, Chalk [2000], for in-stance, weren't based on historical images.LT: Chalk functions as a point of memory for a story.it was a painting that grew from an anecdote I read:the year I was conceptualizing the exhibition wasalso the year a colonial police officer, who made thebodies of Lumumba and his cabinet ministers disap-pear by dissolving them in acid, had died. Beforedoing away with them-and I guess he had an intu-ition Lumumba would become a mythic figure-hepulled two teeth from Lumumba's jaws, which heclaimed he threw into the North Sea just before hedied. So that presented the idea-I had also paintedthe mission post where both Mobutu [who ruled thecountry, which he renamed Zaire, from 1965 to19971 and Lumumba went to school together-of thefailure of the whole acculturation process withinthat colonial system, which is why I decided on thattitle. I chose black gloves and the yellow backgroundto emphasize the whiteness within.YVP: To come back to the question of horror, for meChalk is one of the most gruesome paintings you'vemade. I think that's because this immensely trau-matic and horrific story can be attached to what atfirst sight seems an innocuous image.LT: Yes, that's possible, but the important thing isthat this isn't shown explicitly in its entirety. Andwhen it's simply acknowledged, I think it's alwaysmore horrific. That's where the idea of nostalgia aspure horror comes in, and that sense of inadequate-

ness, and of missing reality. And it is possible thatall those elements come together in somethingreally banal, when, precisely because of its banal-ity, meaning can be directly inverted.

I should add that I don't concern myself with theviewer's prior knowledge of events when I paint.That's something I'm essentially indifferent to. 1.work from my personal fascination with images,and I've never really believed that same fascinationcan exist in someone else, or at least not as in-tensely. Though I don't believe in some singularexperience of these images, it is important for meto know exactly what I'm painting, what it isabout. Without having that knowledge, it's im-possible for me to start creating an image-I sup-pose that's my own limitation.YVP: Presumably your fascination with the dual

roles of artist and viewer of other artists' work hascolored much of your thinking as a curator. I'mespecially interested in your ongoing role withinthe NICC [New International Cultural Center] andhow that feeds back, or doesn't, into your painterlypractice.LT: The NICC was, and is, extremely important tome for a number of reasons. In its early stages, re-acting to the closure of Antwerp's original ICC[Internationaal Cultureel Centruml, it was driven

by enthusiasm and affirmative action, which ledto the existing hierarchies between artists fallingaway and a type of solidarity forming on two fronts.On the one hand we had an urge to develop andachieve certain artistic goals. On the other therewas also strong social activism, which led not onlyto the creation of a new contemporary arts venue

OCTOBER20071 MODERN PAINTERS73

FACING PAGELUCTUYMANS IN HISSTUDIOIN ANTWERP, AUGUST2007PHOTO: ALBRECHT FUCHS

THIS PAGETHE BOOK, 2007OILON CANVAS 01/2OX 81/2 FTCURTESY DAVID ZWIRNER NEWYORK,ANDZENO xGALLERY ANTWERP

but also eventually to the special [tax and legal]status that currently exists for Belgian artists. TheNICC's function has now been more or less trans-formed into a service -oriented one, but before itsexistence artists in my country were a lot moreisolated; it played a vital part in breaking that isola-tion down.

Of course I'm not the only artist involved in cu-rating. There are people like Joblle Tuerlinckx,Michel Francois, Guillaume Bijl, Philip Aguirre,and others who have also taken on that double rolewithin an experimental framework, not so muchto show that curators are unnecessary, or that art-ists can do these things better, but rather to reac-tivate dialogue from within the visual field itself.An artist will, generally speaking, take a very dif-ferent approach to curating. Artists work from an-other kind of modality, with a different vision:usually one that's a lot more oblique and rooted inthe visual than that of curators, who tend to applyconcepts in a more literal way. That's the reasonwhy I first started curating.

The first big project I realized, which I experiencedas a truly collaborative curatorial experience, onewhich I still feel is valuable, was an exhibition titled"Trouble Spot: Painting" [in 1999, at MuHKA andN ICc]. My colleague, the artist Narcisse Tordoir, andI assembled a fairly big show, including works by 75artists, that dealt largely with the interrogation ofpainting as a medium. We tried to avoid the tiredapproach of just placing paintings next to each other,as has been done ad infinitum in the past, reducing

painti ng to wallpaper. We wanted to generate a dis-course by allowing painting to expand into a widerfield, by, for instance, coupling it with installationworks that in our eyes are also situated within anexpanded notion of the painterly but differently con-cretized on a pragmatic level. Those types of juxta-

positions turned out to be well received.

Over the past year I've beenworking on a project called"Forbidden Empire," which is intwo distinct parts: the first wasa more traditional exhibition inwhich classical art from thesouthern Low Countries was jux-taposed with old masters fromChina and hung chronologically,from the 15th century to the 20th. It was shownhere at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, thentraveled to the Palace Museum in the Forbidden Cityin Beijing. I believe this was the first time thatChinese old masters and Western old masters(-ofcourse only from a specific region but still withenormous potential-were shown in relation toeach other. That was a particularly fascinatingstarting point for me, because it created a chanceto reactivate traditional art.

The second part, planned for 2008 and 2009, willbe an exhibition that starts from a similar conceptbut with contemporary art. As with the first show,one of the interesting aspects of the project is thatit's between an enormous country and a tiny one. Iwill choose 35 Belgian artists, and Ai Weiwei, andperhaps another contemporary Chinese artist, willselect 35 artists from China. All the Belgian artistswill travel to China, and all the Chinese artists willcome here and we'll select the works and create theexhibition out of that dialogue. We'll also be collabo-rating with a range of critics, artists, and curators.YVP: I know you've just come back from one of sev-eral recent trips to China, presumably in prepara-tion for the show. Were you there mainly to dostudio visits?LT: No. Although I made some studio visits when Iwas in China, and I got to know a number of artistsmaking strong work over there-Zhang Enli andYang Zhenzhong in particular-I wasn't there to

prospect. I think it's idiotic to try and prospect byyourself there as a Westerner. They have to organizethemselves for the show over there, as we will here.YVP: In what sense do curatorial projects like thisone provide you a different way of approachingpainting?LT: First because they allow me to work with objectsI didn't produce myself, and second, in this particu-lar case, because of the opportunity to work withold masters, which are stunning in their qualita-tive power and became so as we were able to accruemeaning across a time span of centuries. When yourecontextualize that differently, it allows you tolook at them in a totally new way. The contemporarystage of the project will of course add to that by de-veloping discourse between living artists, but work-ing from a similar dynamic as the first show in thatwe'll be foregrounding a similar type of questioningthat comes from a very visually oriented premise.And that is of great importance for me personally,because I feel that contemporary art is, and alwayswill be, primarily a process of visualization.

Luc Tuymans's work appears in "The Painting ofModern Life,"at the Hayward Gallery, London, from October 4 to December30. He will be the subject of a major survey at Haus der Kunst,Munich, opening February 29, 2008, and a retrospective atthe Wexner Center for the Arts, in Columbus, Ohio, openingSeptember 20, 2008. For more information on Tuymans, turnto Index, p. 110.

OCTOBER2007 IMODERNPAINTERS75

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

TITLE: Unnatural Resources: Luc Tuymans on Fighting theLiteral and Mistrusting Images

SOURCE: Mod Painters O 2007

The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and itis reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article inviolation of the copyright is prohibited. To contact the publisher:http://www.modernpainters.co.uk/