Turning the Other Cheek: Profile Direction in Self-Portraiturepclatto/Articles/Latto 1996.pdf ·...

Transcript of Turning the Other Cheek: Profile Direction in Self-Portraiturepclatto/Articles/Latto 1996.pdf ·...

OF THE ARTS

Journal of the International Association of Empirical Aesthetics

EXECUTIVE EDITOR:

Colin Martindale, Pho Do

Volume 14, Number ]-1996

Turning the Other Cheek:Profile Direction in Self-Portraiture

Richard Latto

Baywood Publishing Company, Inc.f. .26 Austin Ave., AmityVille, NY 11701

can (516) 691-1270 fax (516) 691-1770 orderUne (800) 638-7819e-mail: [email protected] web site: http:/tbaywood.com

EMPIRICAL STUDIES OF THE ARTS, Vol. 14(1) 89-98, 1996

TURNING THE OTHER CHEEK:PROFILE DIRECTION IN SELF-PORTRAITURE

RICHARD LATTO

The University of Liverpool

ABSTRACT

The spatial organization of the forty-seven self-portraits in the exhibition

"Face to Face: Three Centuries of Artists' Self-Portraiture" held at the Walker

Art Gallery, Liverpool, was analyzed and compared with previously publish-ed studies, all of which have obtained their data predominantly from non-self -

portraits. In the seventeenth century there was a significant asymmetry in

self-portraits for both the direction of profile, with most paintings showing the

right profile, and the direction of lighting, with most paintings showing the

light coming from the left of the painting. Both these asymmetries declined

over time and were not present in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century paint-

ings. The lighting asymmetry and the temporal change confirmed findings

with non-self-portraits, but the profile asymmetry was in the opposite direc-

tion probably because of the use of mirrors to generate the image being

painted. Taken together, the findings support an explanation for asymmetries

in portraits of all kinds in terms of the conventions of studio organization.

INTRODUCTION

Portrait painters are more likely to paint their subject's left profile than their right.1

This was first reported by McManus and Humphrey [I] who surveyed 1474

portraits painted in western Europe from the sixteenth to the twentieth century and

found that 60 percent of them showed the left profile. It was confirmed by

Hufschmidt [2] who looked at 50,000 artefacts from the stone-age to the present

1 To try and avoid confusion, left profile, left side of the face, etc. will always refer to the left from

the si\ler or subject's point of view. Where I need to reler to the left from the painter or viewer's point

of view, I shall refer to the left of the picture or the left visual field. Figure 1 illustrates this terminology.

89

@ 1996. Baywood Publishing Coo. Inc.

90 / LATTO

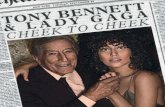

Figure 1. Sir Anthony van Dyck 1599-1641. Self-Portrait with a Sunflower,about 1633. Oil on canvas, 60.3 x 73 cm. In the terminology of this

article, the painting shows the sitter's right profile, while thelight is coming from the left of the picture.

day and Grtisser, Selke, and Zynda [3) who analyzed 933 paintings from the

fifteenth to the twentieth centuries. (None of these studies discriminates between

self-portraits and portraits of others, but since the vast majority of portraits are not

self-portraits it is safe to assume that their data is drawn predominantly from non-

self-portraits and that their conclusions therefore apply only to non-self-portraits.)

The basic finding of a preference for the left profile is very robust and most of

the details are consistent too. McManus and Humphrey [ I) found that the effect

was significant with both male and female subjects but was greater for female

subjects, and this was confirmed by Grtisser et al. [3). McManus and Humphrey

also found that the effect was stronger for "head and body" than for "head only"

portraits, a distinction not looked at by anyone else. Hufschmidt found a right

profile bias until about 600 BC with a consistent left profile bias from the early

Greeks to the present day [2). Grtisser et al. found the strongest left profile bias in

the fifteenth century with a gradual reduction to symmetry by the twentieth

century [3). They perform no statistics on their data but the effect appears to

PROFILE DIRECTION / 91

interact with gender: asymmetry for male subjects is only present in the fifteenthcentury whereas for women it persists at least until the seventeenth century .Theyalso found that there was an even stronger asymmetry in direction of illuminationwhich was more likely to come from the left side of the picture (the subject's right)until the twentieth century when left, right, and diffuse illumination becomeequiprobable. This is independent of the gender of the sitter but they suggest,without statistical analysis, that there may be an interaction with head position. Apreference for light coming from the left of the picture is also found in still lifepaintings implying a general relationship between lighting and subject asymmetrywhich is not limited to the representation of the human face. (If there is a causallink between lighting and head position it is not at all clear in which direction thecausality runs. The artist might arrange the studio with the light coming from theleft and then arrange the sitter facing toward the light or begin by placing thesubject facing left and then arrange the studio to provide the most effectiveillumination of the features.)

Explanations of profile asymmetry are many and varied, and there are almostcertainly several factors operating. The simplest, and perhaps least interestingbecause most mechanical, is that right-handed artists find it easier to draw leftprofiles. Given a free choice, the right hand draws left profiles about 75 percent ofthe time [2, 4-6]. This finding is independent of culture, writing direction and,according to Hufschmidt, preferred hand. However, the profiles drawn with theleft hand show equal numbers of left and right profiles. So while ease of drawingleft profiles with the right hand and vice versa is a factor, there must be othereffects leading to preferences for the left profile which partially override thetendency for the left hand to draw right profiles.

Another potentially important set of factors are the asymmetries found in theprocesses of face perception. Clinical studies of patients with neurologicaldamage [7] and tachistoscopic studies with normal subjects [8] show that facerecognition is a predominantly right hemisphere function. So faces presented inthe left visual field of normals are processed more effectively. This might suggestthat left facing profiles would be more effectively recognized than right, but thisdoes not necessarily follow since in a free viewing situation eye fixations are onthe facial features wherever they are [9-11]. Certainly, there is no direct experi-mental evidence supporting this explanation, but it is one possibility, though as yeta weak one, that a left profile is preferred because it puts more of the informationabout the face in the right, face processing, hemisphere.

There are also clear asymmetries in face perception in free gaze situations. Withfull-face drawings and photographs, the right half of the face seems to be moreimportant for both recognition and for judging the emotional state of the sitter [3,12, 13] and subjects spend more time looking at it [11]. There is no direct evidenceon the relative recognizability of left and right profiles or three-quarter views, butassuming that the effect does generalize to profiles, it does not provide an obviousexplanation for why artists prefer the left, less recognizable, profile.

92 I LATTO

Another clear finding is the observation that emotions are expressed moreintensely on the left side of the face [14-16]. So another possible explanation ofprofile asymmetry in portraits is that painters choose the left profile because it isthe most expressive and therefore most characteristic of the sitter.

The fact that the left side of the face is more expressive also suggests that theemphasis on the right side of the face in perception is not due to the fact that it isthe most informative. It may, much more simply, be caused by a generalizedtendency to attend more to the left side of a picture or view whatever it represents[17-19], though the evidence for this is not entirely clear cut [20]. By extension,then, it could be that painters paint the left profile because it puts the importantfeatures in the left half of the picture.

Another possibility, first suggested by McManus and Humphrey, is that theleft profile is more pleasing than the right [1]. Again, there is no experimentalevidence for this, but there is a possible mechanism for its origin. Since motherstend to hold their babies with the head to the mother's left [21-23], we begin lifeby getting repeated exposure to a left profile. The "mere exposure" effect [24]might be sufficient for this initial experience to lead to a permanent preferencefor left profiles.

McManus and Humphrey also suggested there might be a spontaneous tendencyfor the subject to turn to the right, thus exposing the left profile. Again there are nodirect studies, but there is good evidence of spontaneous right head turning inbabies [25].

The interaction of profile direction with gender has led some authors to specu-late on the social or symbolic significance of the two profiles [1, 3], but these ideasare all rather post hoc and it seems more likely that the interaction is caused bygender differences in the processes underlying one or more of the other theories.

Applying the principle of parsimony, and Lloyd-Morgan's Cannon shouldapply to humans as well as animals, what is the most likely explanation of thepreference for the left profile? If right-handed artists arrange their studio so thatthe palette, held in the left hand, is lined up with the subject being painted to makethe selection of colors easier and the light comes from the left so that the paintinghand does not cast a shadow, then having the sitter's head turned to the rightwould cause the face to be well lit and present the easier-to-draw left profile to theartist. The importance of lighting might also go some way to explaining the genderdifference if we assume that at least until recently the painter of the female portraitwas more concerned with physical beauty and therefore put greater emphasis onensuring that the subject was seen, literally, in the best light than when paintingmen. An explanation in terms of studio organization would also account for thedecline in the effect as artists became less studio bound in the nineteenth andtwentieth centuries.

The other more cognitive explanations considered above may contribute butthey are not necessary to give a full explanation of the findings so far. Until thereis direct evidence that the left profile is aesthetically more pleasing or easier to

PROFILE DIRECTION I 93

recognize or more significant of social status or that sitters spontaneously turn

their heads to the right, the studio bound explanation will remain sufficient. And

its sufficiency can be tested further by looking at data from the unique sub-class of

self -portraits.Until photography became available in the middle of the nineteenth century,

realistic self-portraits necessitated the use of a mirror to generate an image of the

painter. If the sitter in a studio organized in the manner outlined in the previous

paragraph is simply replaced with a mirror angled to reflect the artist at work, then

the image will be reversed and a right profile would be painted. This would also

be true if the artist felt his or her own actual left profile was more pleasing,irrespective of how it was reflected. On the other hand, if ease of drawing is a

dominant factor then the left profile should also be more common in self-portraits,as it would if any of the explanations in terms of leftward attention, or ease of

recognition or aesthetic preference for left profiles in general are correct.An exhibition of self-portraits at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, provided an

opportunity to test these hypotheses.

METHOD

Materials

The exhibition "Face to Face: Three Centuries of Artists' Self-Portraiture," was

held at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, United Kingdom, from October 28,1994 to January 8, 1995. It was organized for National Museums and Galleries on

Merseyside by Xanthe Brooke, curator of European Art at the Walker and con-

sisted of forty-seven oil paintings by forty-four European artists. There were also

a number of drawings which were not used in the present study. The earliest

self-portrait was by Rembrandt in 1630, the most recent by George Frederick

Watts in 1904. There were four Rembrandts. All other artists were represented by

single paintings. The paintings were all from collections in the United Kingdom,

so there was a relatively high representation of British artists. Only three of the

painters were women, not enough to analyze as a separate sub-group. Using

McManus and Humphrey's division into "head only" and "head and body," only

five paintings could be classed as "head only" which was again not enough to

analyze separately.

Scoring

Each painting was scored on two dimensions:

Direction of profile of the subject: Left, Straight ahead, or Right ( where "Left"

indicates that the subject is showing their left cheek).Direction of the source oflighting: Left, Straight ahead, or Right (where "Left"

indicates light coming from the left side of the picture).

94 / LATTO

The date of the painting and the handedness of the painter, where this wasapparent from the self-portrait, were also noted.

RESULTS

The profile and lighting direction for the forty-seven self-portraits are shown inTable I. This shows the distributions both overall and divided into three groupsaccording to the century in which the portrait was painted (the Watts, painted in1904, was included in the nineteenth-century group). Figure 2 shows the samedata expressed as percentages and with the Straight Ahead condition omitted.In the seventeenth-century portraits there was a significant difference for bothprofiles (X2 = 8.33, dl= 1, p < 0.01) and lighting (X2 = 8.33, dl= 1, p < 0.01). In

the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there were no significant differencesbetween directions.

A more detailed analysis of this decline in asymmetry over time showed thatthere was a significant correlation between the date the portrait was painted andboth the direction of the profile (Spearman's rs = 0.40, t = 2.95, p < 0.01) and thedirection of the lighting (Spearman's rs = -O.32, t = 2.23, p < 0.05).

Within paintings, there was a significant negative correlation between thedirection of the profile and the direction of the lighting, that is if the paintingshowed the right profile the light tended to come from the left and vice versa(Spearman's rs = -O.42, t = 3.13, p < 0.01). Handedness could be clearly deter-mined in only eighteen of the portraits. Of these three were left-handed. Therewas no correlation between handedness and the direction of either the profileor the lighting.

DISCUSSION

The asymmetry in lighting found here for self-portraits, with a preponderance

from the left of the picture, is in the same direction as that reported by Griisser

Table 1. Self-Portraits Classified According to the Directions of the Profileand Lighting ("Left" refers to the Sitter's Left Profile and Light Coming

from the Left of the Picture, Respectively)

Profile Lighting

StraightAhead

StraightAheadLeft RightCentury Left Right

1

3

O

11

9

7

1

6

6

1

3

3

17

18

19

1

7

11

11

8

5

27 13 7Overall 19 24 4

96 / LATTO

nonnally seated to the left of the canvas with the light coming from the left,is simply replaced with a mirror angled to reflect the artist as she or he facesthe canvas.

The weakening of this pattern over time may be partly due to the arrival of thenon-reversed photographic image in the nineteenth century , although Figure 2suggests that it begins rather earlier than that so there may be some other factoroperating as well, presumably the same one that causes a decline in asymmetry inportraits in general [3]. One suggestion for this second factor is that it is caused bya move out of the studio or at least a weakening of the conventional studio

organization.The influence of photography is also supported by the negative correlation

between the direction of profile and the direction of lighting. For if the mirror isreplaced by a camera, the photograph of the artist at work will show a left profilewith the light coming from the right of the picture. So if self-portraits consistmainly of either mirror or photographic images, with the camera or the mirrorsimply replacing the sitter, this would generate a negative correlation of thekind found.

The findings in the present study have clear implications for the various explan-ations which have been offered for asymmetry in portraits. They reduce theimportance of ease of drawing or any of the explanations in tenns of leftwardattention, ease of recognition or aesthetic preference for left profiles in general,since all of these would have predicted a preference for left profiles in self-portraits. It remains a possibility that the artist simply finds his or her own leftprofile (appearing as a right profile when reflected in a mirror but as a left profilewhen photographed) more pleasing or more expressive, although the fact that thelighting does not seem to be adjusted to shine on this left profile makes this

explanation less likely.The data from self-portraits thus most strongly support the explanation sug-

gested in the introduction that asymmetry in portraits of all kind is not caused bycognitive or social factors, though these may have some influence, but is simplythe result of the conventions of studio organization.

REFERENCES

1. I. C. McManus and N. K. Humphrey, Turning the Left Cheek, Nature, 243,

pp. 271-272, 1973.2. H.-1. Hufschmidt, Profile im Kulturhistorischen L8ngsschnitt: Bin Dominanzproblem.

Archiv fiir Psychiatrie und Nervkrankheiten, 229. pp. 17-43. 1980.3. 0.-1. Grtisser. T. Selke, and B. Zynda. Cerebral Lateralisation and Some Implications

for Art. Aesthetic Perception and Artistic Creativity, in Beauty and the Brain: Bio-logical Aspects of Aesthetics. I. Rentschler. B. Hertzberger, and D. Bpstein (eds.),Birkh8user Verlag. Basel. Switzerland, pp. 257-293.1988.

PROFILE DIRECTION I 97

4. B. T. Iensen, Left-Right Orientation in Profile Drawing, American Journal of Psychol-

ogy. 65, pp. 80-83, 1952.5. B. T. Iensen, Reading Habits and Left-Right Orientation in Profile Drawing by

Japanese Children, American Journal of Psychology, 65, pp. 306-307, 1952.6. B. Shannon, Graphological Patterns as a Function of Handedness and Culture, Neuro-

psychologia. 17, pp. 457-465, 1979.7. H. H6caen and R. Angelergues, Agnosia for Faces, Archives of Neurology, 7,

pp. 92-100, 1962.8. G. Rizzolatti, C. Umilta, and G. Berlucchi, Opposite Superiorities of the Right and

Left Cerebral Hemispheres in Discriminative Reaction Time to Physiognomical and

Alphabetic Material, Brain, 87, pp. 415-422, 1971.9. G. Buswell, How People Look at Pictures, University of Chicago Press, Illinois,

1935.10. A. L. Yarbus, Eye Movements and Vision, Plenum Press, New York, 1967.11. I. Mertens, H. Siegmund, and 0.-1. Grosser, Gaze Motor Asymmetries in the

Perception of Faces during a Memory Task, Neuropsychologia, 31, pp. 989-998,

1993.12. K. E. Luh, L. M. Rueckert, and I. Levy, Perceptual Asymmetries for Free

Viewing of Several Types of Chimeric Stimuli, Brain and Cognition, 16, pp. 83-103,

1991.13. I. Levy, W. Heller, M. T. Banich, and L. A. Burton, Asymmetry of Perception in Free

Viewing of Chimeric Faces, Brain and Cognition. 2, pp. 404-419, 1983.14. W. Heller and I. Levy, Perception and Expression of Emotion in Right-Handers and

Left-Handers, Neuropsychologia. 19, pp. 263-272,1981.15. R. Campbell, Asymmetries in Interpreting and Expressing a Posed Facial Expression,

Cortex, 14, pp. 327-342,1978.16. H. A. Sackeim and R. C. Gur, Lateral Asymmetry in Intensity of Emotional Expres-

sion, Neuropsychologia. 16, pp. 473-481, 1978.17. I. Levy, Cerebral Asymmetry and Aesthetic Experience, in Beauty and the Brain:

Biological Aspects of Aesthetics, I. Rentschler, B. Herzberger, and D. Epstein (eds.),Birkhauser Verlag, Basel, Switzerland, pp. 219-242, 1988.

18. I. Levy, Lateral Dominance and Aesthetic Preference, Neuropsychologia. 14,

pp. 431-445,1976.19. M. T. Banich, W. Heller, and I. Levy, Aesthetic Preference and Picture Asymmetries,

Cortex. 25, pp. 187-195, 1989.20. I. G. Beaumont, Lateral Organizational and Aesthetic Preference: The Importance of

Peripheral Visual Asymmetries, Neuropsychologia, 23, pp. 103-113, 1985.21. L. Salk, The Role of the Heartbeat in Relation between Mother and Infant, Scientific

American, 228, pp. 24-29, 1973.22. I. L. Richards and S. Finger, Mother-Child Holding Patterns: A Cross-Cultural Photo-

graphic Survey, Child Development. 46, pp. 1001-1004, 1975.23. 0.-1. Grosser, Mother-Child Holding Patterns in Western Art: A Developmental Study,

Ethnology and Sociobiology, 4, pp. 89-94, 1983.24. R. L. Moreland and R. B. Zajonc, Exposure Effects in Person Perception: Familiarity,

Similarity, and Attraction, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 18,

pp. 395-415, 1982.

98 / LATTO

25. G. Turkewitz, E. Gordon, and H. Birch, Head Turning in the Human Neonate: Spon-taneous Patterns, Journal of Genetic Psychology, 107, pp. 143-158, 1965.

Direct reprint requests to:

Richard LattoDepartment of PsychologyUniversity of Liverpool

LiverpoolL69 3BXUK

![Cheek to cheek [jazz] - Free- · PDF fileHe was also a student in jazz interpretation from 1992 until ... About the piece Title: Cheek to cheek [jazz] Composer: ... piano, upright](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/5a727ae17f8b9a98538d9d52/cheek-to-cheek-jazz-free-scorescomwwwfree-scorescompdfenanonymous-cheek-to-cheek-58125pdfpdf.jpg)