Tricycle germer (1.29MB)

-

Upload

mitesh-take -

Category

Spiritual

-

view

88 -

download

2

Transcript of Tricycle germer (1.29MB)

likely to differ from anybody else’s,even those of our nearest and dearest.Given the disparities in our geneticmakeup, conditioning, and life cir-cumstances, it’s a miracle we getalong at all.

Yet we yearn to feel connected toothers. At the deepest level, connected-ness is our natural state—what ThichNhat Hanh calls “interbeing.” We areinextricably related, yet somehow ourday-to-day experience tells us otherwise.We suffer bumps and bruises in rela-tionships. This poses an existentialdilemma: “How can I have an authenticvoice and still feel close to my friendsand loved ones? How can I satisfy mypersonal needs within the constraints ofmy family and my culture?”

In my experience as a couples ther-apist, I’ve found that most of the suf-fering in relationships comes fromdisconnections. A disconnection is abreak in the feeling of mutuality; asthe psychologist Janet Surrey describesit, “we” becomes “I” and “you.” Somedisconnections are obvious, such as thesense of betrayal we feel upon discover-ing a partner’s infidelity. Others may

be harder to identify. A subtle discon-nection may occur, for example, if aconversation is interrupted by one per-son answering a cell phone, or a newhaircut goes unnoticed, or when onepartner falls asleep in bed first, leavingthe other alone in the darkness. It’salmost certain that there’s been a dis-connection when two people findthemselves talking endlessly about“the relationship” and how it’s going.

The Buddha prescribed equanim-ity in the face of suffering. In rela-tionships, this means accepting theinevitability of painful disconnec-tions and using them as an opportu-nity to work through difficultemotions. We instinctively avoidunpleasantness, often without ourawareness. When we touch some-thing unlovely in ourselves—fear,anger, jealousy, shame, disgust—wetend to withdraw emotionally and

direct our attention elsewhere. Butdenying how we feel, or projecting ourfears and faults onto others, onlydrives a wedge between us and thepeople we yearn to be close to.

Mindfulness practice—a profoundmethod for engaging life’s unpleasantmoments—is a powerful tool forremoving obstacles and rediscoveringhappiness in relationships. Mindful-ness involves both awareness andacceptance of present experience. Somepsychologists, among them Tara Brachand Marsha Linehan, talk about radicalacceptance—radical meaning “root”—to emphasize our deep, innate capacityto embrace both negative and positiveemotions. Acceptance in this contextdoes not mean tolerating or condoningabusive behavior. Rather, acceptanceoften means fully acknowledging justhow much pain we may be feeling at a given moment, which inevitably

OVER THE YEARS I’ve come toa conclusion: Human beingsare basically incompatible.Think about it. We live indifferent bodies, we’ve haddifferent childhoods, and atany given moment ourthoughts and feelings are

PH

OTO

: STE

PH

EN

WH

ITE

, CO

UR

TES

Y J

AY J

OP

LIN

G/W

HIT

E C

UB

E, L

ON

DO

N

S P R I N G 2 0 0 6 T R I C Y C L E | 2 5

ON RELATIONSHIPS

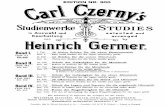

Getting Along Loving the other without losing yourselfCHRISTOPHER GERMER

Love Love’s Unlovable, Gary Hume, 1994, gloss paint on panel, 85 x 144 inches

TRI.SP06_024_027_relationships 1/10/06 12:36 PM Page 25

leads to greater empowerment and creative change.

One of the trickiest challenges for apsychotherapist, and for a mindful-ness-oriented therapist in particular, isto impress on clients the need to turntoward their emotional discomfort andaddress it directly instead of lookingfor ways to avoid it. If we move intopain mindfully and compassionately,the pain will shift naturally. Considerwhat happened to one couple I workedwith in couple therapy.

Suzanne and Michael were living in“cold hell.” Cold-hell couples arepartners who are deeply resentful andsuspicious of each other and communi-cate in chilly, carefully modulatedtones. Some couples can go on like thisfor years, frozen on the brink of divorce.

After five months of unsuccessfultherapy, meeting every other week,Suzanne decided it was time to file fordivorce. It seemed obvious to her that

Michael would never change—that hewould not work less than sixty-fivehours a week or take care of himself (hewas fifty pounds overweight andsmoked). Even more distressing toSuzanne was the fact that Michael wasmaking no effort to enjoy their mar-riage; they seldom went out and hadnot taken a vacation in two and a halfyears. Suzanne felt lonely and rejected.Michael felt unappreciated for work-ing so hard to take care of his family.

Suzanne’s move toward divorce wasthe turning point—it gave them “thegift of desperation.” For the first time,Michael seemed willing to explore justhow painful his life had become. Dur-ing one session, when they were dis-cussing a heavy snowstorm in theDenver area, Michael mentioned thathis sixty-four-year-old father had justmissed his first day of work in twentyyears. I asked Michael what that meantto him. His eyes welling up with tears,

Michael said he wished his father hadenjoyed his life more. I wonderedaloud if Michael had ever wished thesame thing for himself. “I’m scared,”he replied. “I’m scared of what wouldhappen if I stopped working all thetime. I’m even scared to stop worryingabout the business—scared that Imight be overlooking somethingimportant that would make my wholebusiness crumble before my eyes.”

With that, a light went on forSuzanne. “Is that why you ignore meand the kids, and even ignore yourown body?” she asked him. Michaeljust nodded, his tears flowing freelynow. “Oh my God,” Suzanne said, “Ithought it was me—that I wasn’tgood enough, that I’m just too muchtrouble for you. We’re both anxious—just in different ways. You’re scaredabout your business and I’m scaredabout our marriage.” The painful feel-ing of disconnection that separated

2 6 | T R I C Y C L E S P R I N G 2 0 0 6

SAMADHI CUSHIONS SAMADHI STORESince 1975

SAMADHI CUSHIONS · DEPT T · 30 CHURCH ST. · BARNET, VT 05821 1-800-331-7751

Sales support Karmê Chöling Shambhala Buddhist Meditation Center here in Northern Vermont.

ZABUTON

ZAFU

GOMDEN™

Order Online www.samadhistore.com

MORE

Meditation Cushions

Sacred Style

Gongs & Incense

Books & Media

Yoga Mats

Benches

ON RELATIONSHIPS

TRI.SP06_024_027_relationships 1/10/06 12:36 PM Page 26

Michael and Suzanne for years hadbegun to dissolve.

From the beginning of our sessions,Michael had been aware of his worka-holism. He even realized that he wasignoring his family just as he had beenignored by his own father. But Michaelfelt helpless to reverse the intergenera-tional transmission of suffering. Thatbegan to change when he felt the painof the impending divorce. Michaelaccepted how unhappy his life hadbecome, and he experienced a spark ofcompassion, first for his father andthen for himself.

Suzanne often complained thatMichael paid insufficient attention totheir two kids. But behind her com-plaints was a wish—not unfamiliar tomothers of young children—thatMichael would pay attention to her firstwhen he came home from work, andlater play with the kids. Suzanne wasashamed of this desire: she thought it

was selfish and indicated that she was abad mother. But when she could see itas a natural expression of her wish toconnect with her husband, she was ableto make her request openly and confi-dently. Michael readily responded.

A little self-acceptance and self-compassion allowed both Suzanne andMichael to transform their negativeemotions. In relationships, behindstrong feelings like shame and anger isoften a big “I MISS YOU!” It simplyfeels unnatural and painful not toshare a common ground of being withour loved ones.

We all have personal sensitivities—“hot buttons”—that are evoked in closerelationships. Mindfulness practicehelps us to identify them and disengagefrom our habitual reactions, so that wecan reconnect with our partners. We canmindfully address recurring problemswith a simple four-step technique: (1)Feel the emotional pain of disconnec-

tion, (2) Accept that the pain is a naturaland healthy sign of disconnection, andthe need to make a change, (3) Compas-sionately explore the personal issues orbeliefs being evoked within yourself, (4)Trust that a skillful response will arise atthe right moment.

Mindfulness can transform all ourpersonal relationships—but only if weare willing to feel the inevitable painthat relationships entail. When weturn away from our distress, weinevitably abandon our loved ones aswell as ourselves. But when we mind-fully and compassionately inclinetoward whatever is arising within us,we can be truly present and alive forourselves and others. ▼

Christopher K. Germer is a clinical psy-chologist, specializing in mindfulness-oriented couples therapy and treatment ofanxiety, and a co-editor of Mindfulnessand Psychotherapy.

S P R I N G 2 0 0 6 T R I C Y C L E | 2 7

TIBET HOUSE U.S.TIBET HOUSE U.S.

Thubten Chodron • March 31-April 2HOW TO FREE YOUR MIND: TARA, THE LIBERATOR

Sharon Salzberg & Krishna Das • April 28-30AWAKENED MIND & OPEN HEART

Sharon Salzberg & Robert Thurman • May 25-29FIERCE COMPASSION

Cindy Lee & Robert Thurman • June 15-18LOVINGKINDNESS, COMPASSION, JOY & EQUANIMITY

Jivamukti Yoga: Sharon Gannon & David Life • July 7-9THE YOGA OF COMPASSIONATE LIVINGMark Epstein & Robert Thurman • July 27-30

TOWARD A BUDDHIST PSYCHOTHERAPY: INVESTIGATING SELF & SELFLESSNESS

Eddie Stern, John Campbell, & Robert Thurman • August 11-16THE BUDDHA & THE YOGIS

Sharon Salzberg & Robert Thurman • October 3-9 • PEACEGurmukh Kaur Khalsa & Gurushabd Singh Khalsa • October 20-22

YOGA, MEDITATION, & DIALOGUE ON YOGIC & BUDDHIST PHILOSOPHY

Call 212.807.0563 or visit www.menla.org for complete information about these and other programs at Menla. We also welcome group events.

www.menla.orgwww.tibethouse.org

XVI Annual Benefit Concert atCarnegie Hall, Wednesday, March 1, 2006

2006 Programs at Menla Mountain Retreat & Conference Center

Tibet House U.S. will celebrate the Tibetan New Year – the Year of the Fire Dog– with its 16th Annual Benefit Concert

at Carnegie Hall on Wednesday, March 1, 2006 at 7:30 PM.The concert’s Artistic Director, Philip Glass, once again brings together an amazing line-up of artists including:

Philip Glass, Laurie Anderson, Damien Rice,Sufjan Stevens, and others to be announced.

Concert tickets are $30-$108 and can be purchased by calling Carnegie Charge at 212.247.7800 or in-person at the Carnegie Hall

Box Office. A fundraising reception with the event’s Honorary Chairperson and artists will be held following the performance. To reserve tickets for the concert and reception call Tibet House U.S. at 212.807.0563.

Please note: Concert-only tickets are not available through Tibet House.

TRI.SP06_024_027_relationships 1/10/06 12:36 PM Page 27