Tree Frog Final Report 2008

-

Upload

irvanhakim -

Category

Documents

-

view

599 -

download

3

Transcript of Tree Frog Final Report 2008

2008

[The Tree Frog of Chevron Geothermal Concession, Mount HalimunSalak

National Park Indonesia] REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE WILDLIFE TRUSTPEKA FOUNDATION

MIRZA D. KUSRINI M. I. LUBIS

B. DARMAWAN

Citation: Kusrini MD, Lubis MI, Darmawan B. 2008. The Tree Frog of Chevron Geothermal Concession, Mount Hakimun-Salak National Park - Indonesia. Technical report submitted to the Wildlife Truts – Peka Foundation

PHOTO CREDITS Front cover: (top left) The Javanese tree frog Rhacophorus javanus, (top right) a female Philautus vittiger guarding its eggs, (bottom) the green flying frog Rhacophorus reinwardtii M. Irfansyah Lubis: Cover pictures, Fig2-5, fig2,7 to 2-11, Fig 3-1 top, Fig.3-4, Fig 3-4, Fig 3-7, Fig 3-8, Fig 3-0. (Stage 1, 16-18, 20, 21, 25, 42, 44, adult), Fig.3-11 and Fig 3-12 , Fig 3-13, Fig 3-15, Fig 3-16 B. Darmawan: Fig3-2, Fig.3-10. (Stage 13-15, 37,38,41,43,45,46) K3AR-IPB:Fig. 3-1 below

i

Content

Acknowledgments vExecutive Summary vChapter 1. Introduction 1Chapter 2. The tree frog of CGI Concession 4

Introduction 4Methods 4Results 4Species Review 10Discussions 13Literature cited 15

Chapter 3. Breeding ecology of Pgilautus vittiger (Anura:Rhacophoridae) from CGI – Mount Halimun Salak National Park, West Java, Indonesia

17

Introduction 17Methods 18

Animal descriptions 18Survey & Breeding Ecology 19

Results 21I. Habitat 21II. Breeding Ecology 23

2.1 Breeding Season 232.2 Eggs 242.3 Embryonic Development 242.4 Descriptions of tadpole 272.5 Breeding Behavior 292.6 Advertisement Calls 292.7 Parental Care 31

Discussions 31Literature cited 33Appendix 36

Chapter 4. Conclusions and Recommendations 38

List of Figures

Fig 1-1 Mean monthly rainfall (mm) of Parakan Salak weather station, based from 2005 to 2007 data

2

Fig 1-2 Map of survey area at Chevron Geothermal Concession-Mount Halimun-Salak National Park

3

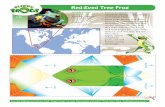

Fig 2-1 Tree Frog Distribution Map in Chevron Geothermal Indonesia, Mount Halimun-Salak National Park 6

Fig 2-2 (a) Undisturbed forest (near awi 10), (b) Disturbed forest (near Powerplant 123)

7

Fig 2-3 (a) Terrestrial habitat near awi 14, (b) terrestrial habitat near awi 4 8

Fig 2-4 Percentage of mature Tree Frog found in Terrestrial habitat in CGI Concession (N = 46 frogs)

8

Fig 2-5 (a) Natural pond near awi 4 and (b) Semi natural pond near awi 7 9

Fig 2-6 Percentage of Tree Frog in Pond habitat in CGI Concession (N= 104 frogs) 9

Fig 2-7 Rhacophorus reinwardtii 10

Fig 2-8 Rhacophorus javanus 11

Fig 2-9 Philautus aurifasciatus 11

Fig 2-10 Philautus vittiger 12

Fig 2-11 Polypedates leucomystax 12

Fig 2-12 Polypedates otilophus 13

Fig 2-12 The distribution of tree frog in three types of habitat at Chevron Geothermal Indonesia Concession Area

14

Fig 3-1 A variety of Philautus vittiger coloring. Picture below shows the underside (left) and distinct shape of disc, webbed toes, tympanum (right)

18

Fig 3-2 (a) plastic box for tadpoles rearing and (b) a close up view of tadpoles inside the box

20

Fig 3-3 Body morphology of a tadpole (based from Dodd,Jr 2004) 20

Fig 3-4 The habitat of Philautus vittiger at CGI concession (a) Natural pond, (b) Semi natural pond and (c) artificial pond 21

Fig 3-5 A male Philautus vittiger perching under a leaf (a) and a coiled old leaf of Musa acuminate (b) with a clutch of eggs inside (c) 22

Fig 3-6 Number of Egg clutches observed at CGI ponds from April to September 2008 23

Fig 3-7 A female Philautus vittiger with visible ripe ova (a) and unripe ova in her stomach (b) 23

Fig. 3-8 Eggs started to hatch 24

Fig. 3-9 Number of Philautus vittiger embryo survived as larvae from lab experiment 25

ii

iii

Fig 3-10 Development of newly fertilized eggs of Philautus vittiger into a fully metamorphose frog.

26

Fig 3-11 The characteristic of Philautus vittiger tadpole 27

Fig 3-12 Labial teeth of Philautus vittiger tadpole 28

Fig 3-13 Breeding sequence of Philautus vittiger. Fig. 3-14a was taken in the natural habitat while the other figures showed mating sequence inside field terrarium. Non calling male have darker coloring than the other frogs. Figure 3-13.f also shows the other female (non-breeding – color pale cream) resting in the same leaf

30

Fig 3-14 (a) An oscilogram of the entire section showing one call group, (b) an oscillogram of the call section showing a single pulsed call from the call group in green bracket in (a), (c) Spectrogram of the pulsed call shown in (b), (d) Power spectrum generated over the peak of the call shown in (b). Un-vouchered male. Record was taken 31 May 2008 at pond-5 at 09.34pm. Air temperature 20oC

30

Fig 3-15 Two different females Philautus vittiger from pond-1 in 28 May 2008 guarding its eggs (a) a female sitting on top of its eggs and (b) a different female wiping her hind feet on top of its eggs

31

Fig 3-16 Unguarded dead eggs found during survey. (a) A clucth of eggs hanging by a thread where leaf was eaten by caterpillar, (b) eggs attacked by ants, (c & d) two different clucthes attacked by fungus

31

List of Tables

Table 2-1 Number of mature individual of each species found in each transect survey 5

Table 2-2 Species found in stream 7

Table 3-1 Various size of P. vittiger from Pengalengan (Iskandar 1998), Mount Halimun (Kurniati 2003) and CGI Concession Mount Salak (Kusrini et al this report)

18

Table 3-2 Pond characteristics in Chevron Geothermal Indonesian Concession Mount Salak

22

Table 3-3 Vegetation used as perching site by Philautus vittiger at CGI-Salak concession

22

Table 3-4 Embryonic development in P. vittiger based from field and laboratory observation. Development duration of each eggs varied, data below shows the fastest development duration

25

Table 3-5 Morphometric measurement of eight Philautus vittiger tadpoles taken from different ponds at CGI concession in Mount Halimun-Salak National Park. All measurements are in mm.

28

iv

List of Appendix

Appendix-1 Development of Philautus vittiger embryos from newly fertilized eggs by a pair of frogs taken on 29th of August 2008 from the field.

36

Appendix-2 Development of Philautus vittiger embryos from newly fertilized eggs by a pair of frogs taken on September 2008 from the field 36

Appendix-3 Development of 14 Philautus vittiger tadpoles raised in lab. at Faculty of Forestry in Bogor taken from 28 May 2008 36

Appendix-4 Development of Philautus vittiger embryos raised in lab. Eggs including the leaf where it hangs were taken in 29 August 2009 from the field. The embryo inside eggs were already in stage 23-24

37

v

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is made possible from funding from Chevron Corporation to the Wildlife Trust in partnership with Peka Foundation Indonesia. We thank the management of Chevron Geothermal Indonesia for access and assistance during field works. We thank Damayanti Buchori, Shinta Puspitasari, Bandung Sahari, Wika, Heri Tabadepu, and Iyus, from Peka Foundation for advice and assistance in the field. We are grateful for the assistant of Mr. Ucup, Mr. Jejen and family who had shared their house with us every month. Dede Hendra Setiawan, Asyrafi, Nur Ikhwan, Akmal, Arif Tajali, Beny Aladin and Neneng Sholihat had volunteered their time in the field, thank you. We also appreciate advices and insights given by Jodi Rowley during the preparation of this report.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The forest surrounding the Chevron Geothermal Indonesia (CGI) Mount Halimun-Salak National Park concession offers a unique opportunity to study the distribution and natural history of tree frog, especially to understand how habitat within a geothermal concession might still able to sustain tree frog diversity. As part of the broad project of tree frog conservation in Indonesia, our first year aims are to map the distribution of tree frog within the CGI concessions and the surrounding corridor area to increase our understanding of the role of habitat for the conservation of this species and to study the breeding ecology of Philautus vittiger.

Six species of tree frog (Rhacophoridae) is found in CGI concessions, consisted of one new record for West Java, which is Polypedates otilophus. Other tree frog species found are Rhacophorus reinwardtii, Rhacophorus javanus, Philautus aurifasciatus, Philautus vittiger, Polypedates leucomystax.

The primary habitat for Philautus vittiger is permanent pond. Result from this research shows that the development of artificial and semi-artificial ponds by the CGI managements has benefit the frogs by providing suitable breeding habitat for this species. Males were found calling in all observed locations during the six month observation periods. Females attending breeding sites were either taking care of the clutch or ready to breed. Mean number of eggs in one clutch is 52 (n = 12; range: 37 – 66 eggs, SD= 8.25). Eggs are un-pigmented, pale yellow in color and coated by sticky jelly substance. The diameter of egg is 3.98 mm (stage 11) to 4.96 (stage 21). Fertilized eggs will hatched after about 16 days. Tadpoles will emerge as stage 25 and slide to water below the leaves . Tadpoles will stay in stage 25 for quite some time (48 days the fastest), growing its body before moving to the next stage. After about 2 months tadpole will be in stage 26-36 where hind limb develop. In the next 20 days, front limb will emerge. It takes about 3 months for an egg to be a fully metamorphosed frog. We also described for the first time the tadpole, breeding behavior, parental care and frog call of this species. The result of this survey reveals that Philautus vittiger have a free tadpole stage, contrary to the characteristic of the genus. Therefore, in our opinion, there is a need to review the taxonomy of this species and exclude this species from Philautus genus.

Pa

ge1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION Indonesia is home to at least 376 species of amphibians (IUCN 2007), where 102 species are tree frogs from the family Rhacophoridae and Hylidae. About a third of this tree frog species is Data Deficient, 1 species are Critically Endangered, 3 species Endangered, 9 species are Vulnerable and 12 species are Near Threatened. Almost all tree frog species are attractive and depended on the occurrence of forest vegetation. At least 40 species of frogs of Indonesia are on the list for export in live form (for pet) or in skin form (for leather product), out f which 14 species are tree frog (Ministry of Forestry 2007). The habitat and their population are thus potentially vulnerable to human pressure. The overall aim of this project is to collect baseline data on the bio-ecology and habitat of the tree frog to assess population status and management, which is lacking. As the first phase, we will start with the Javanese tree frog, focusing on the endemic frog, Rhacophorus javanus (VU), Philautus vittiger (DD), P. jacobsoni (CR) and Nyctixalus margaritifer (VU). Report on the population status of tree frog species, even for most amphibian in Indonesia is scarce, mostly because lack of monitoring effort. The forest surrounding the Chevron Geothermal Indonesia (CGI) Mount Halimun-Salak National Park concession offers a unique opportunity to study the distribution and natural history of tree frog, especially to understand how habitat within a geothermal concession might still able to sustain tree frog diversity. As part of the broad project of tree frog conservation in Indonesia, our first year aims are to map the distribution of tree frog within the CGI concessions and the surrounding corridor area to increase our understanding of the role of habitat for the conservation of this species and to study the breeding ecology of Philautus vittiger. Study site The study area, Chevron Geothermal Indonesia concession is located at elevation of 950 – 1050 m asl (S 06°44.471′ E 106°38.453′; Fig.1-2). Most of the forested area consisted of Schima wallichii, Quercus lineate, Altingia excels and shrubs such as Cyathea sp. and Pandanus sp (PPLH IPB 2006). The area constantly receives rainfall every month (Fig.1-1), resulting of almost all year round of permanent stream and ponds, thus an ideal habitat for amphibian species. Monthly rainfall statistics were obtained for the period of 2005 to 2007 for the Parakan Salak weather station (Bureau of Meteorology). This is the closest station with a complete rainfall data set to the site where survey was carried out (approx. 20 km distance).

Pa

ge2

Fig.1-1. Mean monthly rainfall (mm) of Parakan Salak weather station, based from 2005 to 2007 data

Survey Methods

Distribution survey was conducted by 4-5 persons for 4 nights in a row each month from April to June 2008. Comprehensive night survey was carried out in streams, ponds and terrestrial habitat within concession area, mostly near the gas checking point (coded as AWI Bengkok or Awi for short). A 400 m transect survey was conducted in 5 streams. We visited 12 ponds around the area consisting of one artificial pond and five semi artificial ponds and six natural ponds. A total of 77 hours of time-search was conducted in 11 terrestrial habitats mostly in forest near the graveled path used by the workers to check on the gas pipe and also in tea plantation that surround the area. If possible, we measured the snout-vent length (SVL) of males and females to the nearest 0.1 mm with calipers and weigh body mass to the nearest 0.5 g with Pesola mechanic balance.

Pa

ge3

#S

#S

#S

#S

#S

#S

#S

#S

#S

#S

#S#S

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

ÿ

Awi 9

Awi 8

Awi 7

Awi 3 Awi 9

Awi 1

Awi 2 Awi 5

Awi 6

Awi 10

Awi 12

Awi 16

Awi 13

Awi 14

Awi 11

Pond 1

Pond 2

Pond 3

Pond 4

Pond 5

Pond 6

Pond 7

Pond 8

Pond 9

Pond 10

Pond 11Pond 12

Cikuluw

ung River

Sakati River

682500

682500

685000

685000

9252

500 9252500

9255

000 9255000

500 0 500 1000 Meters

N

EW

SWEST JAVA

TNGHS

#

CGI

LegendRoad

#S Pond Locationÿ Awi Point

River

Insert

Fig.1-2. Map of survey area at Chevron Geothermal Concession-Mount Halimun-Salak National Park

Pa

ge4

Chapter 2

THE TREE FROG OF CGI CONCESSION

Introduction The tree frogs are probably one of the attractive frog species compared to others. Most of the species are forest dependent, thus making tree frog an ideal animal as indicator of healthy forest. The Chevron Geothermal Indonesia concession (S 06°44.471′ - .559′ E 106°38.453′ - .882′ - 951 – 1039 asl) known previously as Unocal Geothermal Indonesia is located between Mount Salak and Halimun, West Java.

The forest surrounding the CGI concession offers a unique opportunity to study the distribution and natural history of tree frog, especially to understand how habitat within a geothermal concession might still able to sustain tree frog diversity. As part of this proposal, our first year aims are to map the distribution of tree frog within the CGI concessions and the surrounding corridor area to increase our understanding of the role of habitat for the conservation of this species

Methods The CGI concesssion area and the surrounding concession area were surveyed

to map the current distribution of treefrog. Survey was carried out for three months from April to June 2008. Seven permanent stream ranges from 300-500 m length were selected randomly from different elevation and habitat type (disturbed and non disturbed forest). Three streams are located near disturbed forest (mostly near buildings: one located near the power plant 123 Pertamina, one located on the border of tea plantation, and the last one located near the main office building) and four streams in non disturbed forests. Surveys in ponds were conducted in 12 locations, consisting of natural ponds, semi natural ponds and one artificial pond. Survey in terrestrial area was carried out in 14 transect of 500 to 1000 m length near awi. Transects encompassed the yards of awi facilities and office buildings, small path inside forests, roadside of the asphalt street.

Each month we conducted a week-long survey within the designated area using Visual Encounter Survey method (Heyer et al 1994). A combination of methods were carried out during frog surveys: nocturnal survey, daytime survey, and tadpole survey. Presence and absence data of treefrog are derived from frog surveys. An area will have present status of a species if one tadpole or juvenile/adult of this species are found in the area. For each frog found, we recorded the site with GPS for further mapping. For more detailed information, see Survey Methods section in chapter 1.

Results In total, 20 species of anuran is found in this area consisting of Bufonidae (Bufo asper, Leptophryne borbonica), Megophryidae (Megophrys montana, Leptobrachium hasselti ), Microhylidae (Microhyla achatina, M. palmipes), Ranidae (Rana hosii, R. chalconota,R. nicobariensis, Fejervarya limnocharis, Limnonectes kuhlii, L. macrodon, L. microdiscus, Huia masonii ), and Rhacophoridae (6 species). The tree frog species consisted of one

Pa

ge5

new record for West Java, which is Polypedates otilophus. Other tree frog species found are Rhacophorus reinwardtii, Rhacophorus javanus, Philautus aurifasciatus, Philautus vittiger, Polypedates leucomystax. Table 2-1 show the number of tree frogs found in each survey location, whilst Fig.2-1 shows the distribution of tree frog within the CGI concession area. Mature tree frogs inhabit three main habitats: permanent streams, permanent ponds and terrestrial habitats. All tadpoles (except for P. aurifasciatus) were found in aquatic habitats: ponds, streams, roadside ditches and ephemeral pools. Table 2-1 Number of mature individual of each species found in each transect survey

Habitat No Rr Rj Pa Pv Pl Po Total Terrestrial 1 10 0 0 0 2 0 12 Terrestrial 2 3 2 1 0 1 0 7 Terrestrial 3 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Terrestrial 4 1 0 0 0 2 0 3 Terrestrial 5 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Terrestrial 6 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 Terrestrial 8 6 0 0 0 2 0 8 Terrestrial 9 3 0 0 0 1 0 4 Terrestrial 10 2 1 0 0 1 0 4 Terrestrial 11 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Terrestrial 12 1 1 0 0 0 0 2 Terrestrial 13 0 0 1 0 0 1 2 Terrestrial 14 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Stream 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Stream 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Stream 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Stream 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Stream 5 0 10 0 0 0 0 10 Stream 6 0 18 0 0 0 0 18 Stream 7 0 7 1 0 0 0 8 Pond 1 1 1 0 13 0 0 15 Pond 2 6 0 0 0 3 0 9 Pond 3 5 15 1 6 0 0 27 Pond 4 0 12 0 2 0 0 14 Pond 5 0 2 0 11 2 0 15 Pond 6 0 0 0 3 0 0 3 Pond 7 0 3 0 1 0 0 4 Pond 8 1 1 1 1 0 0 4 Pond 9 0 2 0 2 0 0 4 Pond 10 1 0 0 1 0 0 2 Pond 11 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 Pond 12 2 0 0 4 0 0 6

Total 44 76 6 45 14 1 186 Notes: Rr : Rhacophorus reinwardtii, Rj: Rhacophorus javanus, Pa: Philautus aurifasciatus, Pv: Philautus vittiger, Pl: Polypedates leucomystax, Po: Polypedates otilophus

Figure 2-1.Tree Frog Distribution Map in Chevron Geothermal Indonesia, Mount Halimun-Salak National Park

Pa

ge7

Permanent Stream Only two species of tree frogs were found in permanent streams: R. javanus and P. aurifasciatus. Frogs were found both in disturbed and undisturbed habitat. Rhacophorus javanus is a species that can be found in primary forest or open forest area near slow-moving waters (Kurniati 2003).

Figure 2-2 (a) Undisturbed forest (near awi 10), (b) Disturbed forest (near Powerplant 123)

Table 2-2. Species found in stream Habitat Location category Species

Stream 1 Near Power Plant 123 Disturbed No tree frogs Stream 2 Near tea plantataion Disturbed No tree frogs Stream 3 Near awi 10 Undisturbed No tree frogs Stream 4 Near awi 6 Undisturbed No tree frogs Stream 5 Below mushalla Disturbed R. javanus Stream 6 Cikuluwung Stream Undisturbed R. javanus Stream 7 Near Awi 7 Undisturbed R. javanus, P. aurifasciatus

Terrestrial Habitat

Five species of tree frogs were found: R. reinwardtii, R. javanus, P. aurifasciatus, P. leucomystax dan P. otilophus. All, except the latter is not restricted to terrestrial habitat alone. Mature Rhacophorus reinwardtii and its tadpole are mostly found near ephemeral pool inside forest, as well as R. javanus. P. leucomystax and also R. reinwardtii can be found in roadside ditch along the road. One Polypedates otilophus was found already dead (seemingly hit by a car) on the road near the main office. In Sumatra this specis is commonly found in small ponds in primary or secondary forests (Mistar 2003).

(a) (b)

Pa

ge8

Fig.2-3 (a) Terrestrial habitat near awi 14, (b) terrestrial habitat near awi 4 The number and distribution of tree frog differs for each species. The highest number of tree frog found in terrestrial habitat is R. reinwardtii. Rhacophorus reinwardtii is a common species in primary or secondary forests and distributed widely from 250 – 12000 m above sea level (Iskandar 1998). The only tree frog not found in terrestrial habitat is P. vittiger, which is a pond specialist. Fig.2-4 shows the percentage of tree frogs found in terrestrial habitats.

Fig. 2-4 Percentage of mature Tree Frog found in Terrestrial habitat in CGI Concession (N = 46

frogs)

Permanent Ponds Frogs found in pond or other lentic habitats are mostly species having characteristic of tadpoles suited to still or slow moving waters such as R. reinwardtii, R. javanus, dan P. leucomystax, where as for Philautus usually have a direct development mode (Iskandar 1998). Thus Philautus are rarely seen in aquatic habitats, mostly seen deep inside forest far from water source. However, this characteristic is not effective with Philautus vittiger. Unlike P. aurifasciatus, this species is found restricted to habitat near ponds.

(a) (b)

Pa

ge9

(a) (b)

Fig.2-5. (a) Natural pond near awi 4 and (b) Semi natural pond near awi 7

Five species of tree frog were found in ponds: R. reinwardtii, R. javanus, P.

leucomystax, P. aurifasciatus dan P. vittiger. The highest number of frogs found in ponds is Philautus vittiger (found in all except one ponds for a total of 45 individuals), followed by Rhacophorus javanus (36 individuals). Fig.2-6 shows the percentage of tree frogs found in pond habitats.

Fig. 2-6 Percentage of Tree Frog in Pond habitat in CGI Concession (N= 104 frogs)

(a) (b)

Pa

ge1

0

Fig.2-7. Rhacophorus reinwardtii

Species Review

Rhacophorus reinwardtii A pretty and colorful tree frog. Upper side of body leaf green, flank orange, ventral side of body yellowish orange. All except first finger has extensive dark blue web reaching discs. It has rounded snout and distinct tympanum. Distribution: Distributed widely from South China to Malaysia, Sumatra, Kalimantan and Java (Iskandar, 1998). In West Java it is found in Mount Gede Pangrango National park (Bodogol, Cibodas, Telaga Biru) (Kusrini 2007), Mount Halimun, forested area of perum perhutani (Kusrini & Fitri 2006) and even in small patch of forested area of IPB campus in Darmaga Bogor (Yuliana et al 2005). In CGI found mostly on terrestrial habitat near disturbed area such as near office building or other facilities. Several are found in ponds or ephemeral pool. In CGI this is the second most abundant frogs (44 mature individuals). It is found in most awi, even in tea plantation in the border of CGI. Conservation Status: Least Concern (IUCN 2007) Bio-ecology: Males are significantly smaller than females (Liem 1971, Berry 1975, Inger &Stuebing 1997, Iskandar 1998, Yazid 2006). Males SVL 45-66 mm, females SVL 55-80 mm. Breeds all year, however population that live near ephemeral ponds that depends on heavy rainfall have a tendency to breed seasonally (Yazid 2006). No report on number of eggs, however our observation found 111 eggs in one foam and dissection of one female specimen from other area found 209 unfertilized eggs inside (Kusrini, unpublished data). Fertilized eggs are inside foam nest. Nests are usually put on leaf overhanging still waters or in leaf litter in areas higher than ephemeral pools (Yazid 2006) Threats: In Indonesia, this species is collected for international pet trade. Quota for this species is relatively low, for instance harvest quota for 2007 was 4,500 and taken from Java (Dephut 2007). Rhacophorus javanus (sinonym Rhacophorus margaritifer) It is a moderate-sized tree frog, snout weakly projecting. Toes webbed to discs except fourth toe. Heels are with flab of skin. Skin colors are grey mahogany to reddish brown with uneven spots. Distribution: It is an endemic frog from Java. In Mount Halimun it occurs among shrubs that are close to slow moving water in primary forest (Kurniati 2003). In CGI the frogs are found in terrestrial, stream and ponds. Mostly found in trees near aquatic habitats, elevation from 1000-1250 m asl. This is the most abundant tree frogs found during the survey (72 mature individuals). Conservation status: Vulnerable (IUCN 2007)

Pa

ge1

1

Fig.2-8. Rhacophorus javanus

Fig.2-9. Philautus aurifasciatus

Bio-ecology: Males are smaller than females. Measurement from 171 individuals from West Java taken in 2002-2007 showed that females can reach SVL up to 71 mm, whilst male reach up to 45 mm (Kusrini et al 2008). No data on number of clutch in natural habitat. A specimen of a female frog from Curug Cibeureum (Gede Pangrango NP) taken in 2003 showed 127 mature ova and 62 immature ova. As of R. reinwardtii, fertilized eggs are put in foam nest. Presumably breeds all year round. Threats: Mostly found in forested area, thus vulnerable to change of habitat. In Indonesia, this species is collected for international pet trade. Quota for this species is relatively low, for instance harvest quota for 2007 was 900 (Dephut 2007). Species from Cibeureum (Mount Gede Pangrango NP) was found heavily infected with Batrachohytrium dendrobatidis (Kusrini et al 2008). There is no data of impact of Bd to its population. Philautus aurifasciatus Small-sized tree frog with a dull pointed snout. Tips of digits with flattened discs. Color greenish to brownish. Sometimes have a H or X marking in the back. Distribution: This species occurs above 900 m asl on Java and Sumatra in Indonesia (IUCN 2007). In Mount Halimun it lives among shrubs in mossy forest, and usually found on the leaf about one meters above the ground (Kurniati 2003). In CGI the calls is often heard deep in the forest. It is found in trees near stream, forest habitat and ponds. Only six individual were seen during survey. Conservation status: Least Concern (IUCN 2007) Bio-ecology: No report on the number of eggs. Personal observation found 11 eggs in one clutch in Telaga Warna (Ul-Hasanah, unpublished data). The generic name of Philautus comes from this species. There is no tadpole stage, embryo is direct development. Threats: Mostly found in forested area, thus vulnerable to change of habitat. In Indonesia, this species is collected for international pet trade. Quota for this species is relatively low, for instance harvest quota for 2007 was 675 (Dephut 2007).

Pa

ge1

2

Fig.2-10. Philautus vittiger

Fig.2-11. Polypedates leucomystax

Philautus vittiger A small stout tree frog with snout truncate but not projecting. Fingers and toes dilated into discs. Fingers with rudimentary webbing. It is an endemic frog from west java. Distribution: Found in Mount Halimun (Kusriniati 2003) and Pengalengan (Iskandar 1998). In CGI is found in shrubs restricted in ponds near or inside forest. This is the most abundant tree frogs in pond habitats. Conservation status: Data Deficient (IUCN 2007) Bio-ecology: Males are larger than females. The frogs seem to breed all year round. Eggs are laid as jellied clumps in leaves overhanging permanent water-bodies. See chapter 3 for more detailed breeding ecology. Threats: It seems restricted to high elevation sites, in vegetated ponds within forest or near forested. Habitats are in risk to modification. Polypedates leucomystax Large sized tree frog with colour brownish or yellowish green. Males are smaller than females, with stripes from head to the end of body or without stripes but with scattered darker spots. End of digits are flatly enlarged. Not quite fully webbed in the toes, but half webbed in fingers. Distribution: Distributed widely from India, South China, Japan, Phillipines and Indonesia. In Indonesia it is found in most islands, including Nusa Tenggara and Papua (intro). Abundant in villages’ garden (Iskandar 1998; IUCN 2007). In CGI its foam nest is found in ponds in the vicinity of buildings near AWI. Rarely seen in ponds inside forested area. Conservation status: Least Concern (IUCN 2007) Bio-ecology: Males are smaller than females, up to 50 mm in males, 70 mm snout-vent length in females. Clutch can reach as many as 900 eggs (Alcala 1962, Leong & Chou 1999). Although mean embryonic and larval survival might be low (2% - Yorke 1983), the frogs thrive in human modified landscape by utilizing ditches or garden’s vegetation as retreat sites during the day (Sholihat 2007). As of R. reinwardtii, fertilized eggs are put in foam nest. Foam nest might be attached in artificial ponds’ walls or in leaf overhanging permanent or temporary water bodies (Irawan 2008). It breeds all year round. Call analysis of this species is available from Bali (Marquez & Eekhout 2006) Threats: In Indonesia, this species is collected for international pet trade. Quota for this species is relatively low, for instance harvest quota for 2007 was 13,500 (Dephut 2007).

Pa

ge1

3

Fig.2-12. Polypedates otilophus

Polypedates otilopus Compared to P. leucomystax, this is a larger sized frog. In life the color is brown with dorsal hour-glass mark. Hells have small tubercle. The base of jaw with sharp bony processes and bony crest projecting above tympanum. Limbs have dark crossbars. Distribution: Borneo (Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia) and on Sumatra. However, recent report suggested that this frog is also found in central Java (Awal, unpublished report). In CGI a dead male was found during survey in terrestrial area, in roadside. Conservation status: Least Concern (IUCN 2007) Bio-ecology: males range from 64-80 mm and females from 82-97 mm (Inger and Stuebing 1997). In Kalimantan, it is usually found on vegetation near pools and breeding season is presumably during April thorugh May (Inger 1966). Eggs are put in foam nest where hatching tadpole will drop into water (Inger and Stuebing 1997). There is no data on the number of eggs. Adults feed insects and spiders (Malkmus 2002), especially large tree crickets (Inger and Stuebing 1997). Threats: In Indonesia, this species is collected for international pet trade. Quota for this species is relatively low, for instance harvest quota for 2007 was 1,350

DISCUSSIONS

Compared to Sumatra or Kalimantan, the amphibian species of Java is less diverse with only 36 species of amphibian (Iskandar 1998). The finding of 20 species of amphibian in CGI concession, including one new record showed that the forested area of CGI concession is still able to sustain this diverse species. The finding in 2008 survey is higher compared to result of previous survey. An one-day survey in the Cisaketi Stream in 2002 found 5 species of frogs (Kusrini, unpublished data), while a six day aquatic and terestrial survey in 2006 (total 14 hours of search effort) reported 10 species occurring in CGI concession area (Kusrini and Fitri 2006). Differences in result are most probably due to higher search effort in this survey (77 hours of search effort) which encompassed six month of repeated survey. It is interesting that we were able to record Polypedates otilophus which for years have escaped the scrutiny of noted herpetologist who worked with Indonesian species such as van Kampen (1923) and Iskandar (1998). The finding of this species coincidentally occurs almost the same time with the finding of the same species in Mount Slamet, Central Java (Awal, unpublished data). With higher effort of survey in Java, it is thus possible to found other species unrecorded previously or presumed extinct. In general, the tree frogs need both aquatic and terrestrial habitat for their live hood. Except for P. aurifasciatus which do not have aquatic stage during their development, all of the other tree frog species in CGI needs water bodies for their tadpole stage. Rhacophorus reinwardtii is more dominant on terrestrial habitat compared to R. javanus which also found in stream; however it is clear that R. reiwardtii depends on water

Pa

ge1

4

Fig.2-13. The distribution of tree frog in three types of habitat at Chevron Geothermal Indonesia Concession Area

bodies since it is mostly found near temporary water bodies inside the forest. Philautus vittiger is not found in terrestrial habitat but restricted to permanent pools compared to P. aurifasciatus which is found mostly in terrestrial habitat and near stream

0

10

20

30

40

50

Terrestrial Stream Pond

Rhacophorus reinwardtii Rhacophorus javanus

Philautus aurifasciatus Philautus vittiger Polypedates leucomystax Polypedates otilopus

Pa

ge1

5

The main threat to tree frog population in CGI is loss or continued degradation of habitat. We saw no evidence of amphibian being collected commercially for pet or consumption. There is also a possibility of Bd occurring in this area, considering the finding of Bd in Mount Gede Pangrango. We have encountered several Rhacophorus javanus that remain passive during the night, however we are not certain if the frogs showed clinical signs of the impact of this disease. A Bd survey might be needed to The most diverse community of tree frog was found in pond habitats. Conservation effort thus should focus on maintaining the pond habitats. Philautus vittiger are well suited to monitoring pond habitats as they restricted themselves in ponds to breed, and males congregate to call at night from vegetation at the water edge. Ponds can be easily surveyed at night, either by listening for chorus activity (to record presence/absence), or by counting individuals along transect at the perimeter of the pond. This type of nocturnal monitoring could also be extended to include two other common species that frequently encountered at the pond perimeter: R. reinwardtii and R. javanus. LITERATURE CITED

Alcala, A. C. 1962. Breeding behaviour and early development of frogs of Negros, Philippine islands. Copeia 1962(4): 679 - 726.

Berry, P. Y. 1975. The amphibian fauna of peninsular Malaysia. Tropical Press. Kuala Lumpur127. pp.

[Dephut] Departemen Kehutanan Republik Indonesia. 2007. Surat keputusan direktur jenderal PHKA nomor : SK 33/iv-KKH/2007kuota pengambilan tumbuhan dan penangkapan satwa liar yang tidak termasuk appendix cites untuk periode 2007: 61 pp.

Inger, R. F, and Stuebing, R. B. 1997. A Field Guide to the Frogs of Borneo. Natural History Publications (Borneo) Limited, Kota Kinabalu.

Inger, R. F. (1966). ''The systematics and zoogeography of the Amphibia of Borneo.'' Fieldiana Zoology, 52, 1-402.

Irawan, F. 2008. Preferensi habitat berbiak katak pohon bergaris (Polypedates leucomystax Gravenhorst 1829) di kampus ipb dramaga bogor. Skripsi. Departemen Konservasi Sumberdaya Hutan dan Ekowisata, Fakultas Kehutanan, Institut Pertanian Bogor, Bogor.

Iskandar DT. 1998. Amfibi Jawa dan Bali – Seri Panduan Lapangan. Puslitbang – LIPI. Bogor.

IUCN 2007. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed at <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 14 July 2008.

Kurniati H. 2003. Amphibians and Reptile of Gunung Halimun National Park West Java, Indonesia (Frog, Lizard and Snake). Cibinong : Puslitbang Biologi LIPI.

Kusrini, M. D. 2007. Frogs of Gede Pangrango: A follow up project for the conservation of frogs in west java indonesia. Book 1: Main report. Technical report submitted to the BP conservation programme. Bogor, Institut Pertanian Bogor: 71.

Kusrini, M. D., M. I. Lubis and B. Darmawan. 2008. Ecology and conservation of treefrog of west java, Indonesia. Technical report submitted to Sea World/ Busch Garden conservation fund. Bogor, PEKA Foundation: 7pp.

Pa

ge1

6

Kusrini, M. D., L. Skerratt, L. Berger, S. Garland and W. Endarwin. 2008. Detection of chytridiomycosis in frogs of mount gede-pangrango, indonesia. Diseases of aquatic organism; In press.

Kusrini, M. D. and A. Fitri. 2006. Ecology and conservation of frogs of mount Salak, West Java, Indonesia. Final report submitted to the wildlife trust. Bogor, Institut Pertanian Bogor: 30pp.

Leong, T. M. and L.M.Chou. 1999. Larval diversity and development in the Singapore anura (amphibia). The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 47(1): 81-137.

Liem, D. S. S. 1971. The frogs and toads of Tjibodas national park Mt. Gede, Java, Indonesia. The Philippine Journal of Science 100(2): 131-161.

Malkmus, R., Manthey, U., Vogel, G., Hoffmann, P., and Kosuch, J. 2002. Amphibians and Reptiles of Mount Kinabalu (North Borneo). Koeltz Scientific Books, Koenigstein, Germany.

Marquez, R. and X. R. Eekhout. 2006. Advertisement calls of six species of anurans from bali, republic of Indonesia. Journal of Natural History 40(9-10): 571-588.

Mistar. 2003. Panduan Lapangan Amfibi Kawasan Ekosistem Leuser. Bogor: The Gibbon Foundation & PILI-NGO Movement.

Sholihat, N. 2007. Pola penggunaan ruang dan pergerakan katak pohon bergaris (polypedates leucomystax) di kampus ipb darmaga. Skripsi. Departemen Konservasi Sumberdaya Hutan dan Ekowisata, Fakultas Kehutanan, Institut Pertanian Bogor, Bogor.

Yazid, M. 2006. Perilaku berbiak katak pohon hijau (rhacophorus reinwardtii kuhl & van hasselt, 1822) di kampus ipb darmaga. Skripsi. Departemen Konservasi Sumberdaya Hutan dan Ekowisata, Fakultas Kehutanan, Institut Pertanian Bogor, Bogor.

Yorke, C. D. 1983. Survival of embryos and larvae of the frog Polypedates leucomystax in Malaysia. Journal of Herpetology 17(3): 235-241.

Yuliana, S., M. D. Kusrini and H. Remetwa. 2005. Pendugaan asosiasi interspesifik dan pengelompokan tipe habitat beberapa jenis amfibi. Jurnal Penelitian Hutan dan Konservasi Alam II(2): 189-196.

Pa

ge1

7

Chapter 3

BREEDING ECOLOGY OF Philautus vittiger (ANURA:

RHACOPHORIDAE) FROM CGI – MOUNT HALIMUN

SALAK NATIONAL PARK, WEST JAVA, INDONESIA

INTRODUCTION Philautus vittiger or the wine colored tree frog was first described by Boulenger in 1897 as Ixalus vittiger based from specimen from Mount Pengalengan, West Java province, Indonesia (Bossuyt and Dubois 2001; Iskandar 1998). Although described more than 100 years ago, the population and bio-ecology of this small tree frog species has never been studied thoroughly and the frog has been listed as Data Deficient (IUCN 2007). To date, several populations of P. vittiger has been identified in West Java, which consist of Situ Lembang and Mount Burangrang (Iskandar 1998), Mount Halimun (Kurniati 2003) and Mount Salak (Kusrini and Fitri 2006). There is no detailed habitat description of this species, however from previous report it is known that it inhabits high elevation locations (more than 900 m above sea level) and mostly found near ponds or stagnant waters (Kurniati 2003; Kusrini & Fitri 2006).

Mount Salak (latitude 6.72°S – 6°43’0”S, Longitude 106.73°E – 106°44’0”E) with the highest level of 2211 m, is one of remaining pristine habitat in West Java. Although less known compare to other mountain in West Java such as Gede-Pangrango, the area, which harbors various waterfalls and diverse ecosystems is popular with local hikers. The forest of Mount Salak was managed by Perum perhutani, a state owned forest production management. In 2003, Mount Salak was incorporated into the management of Mount Halimun National Park under the Ministry of Forestry decree Number 175/Kpts-II/2003. The decree had changed the name of Mount Halimun National Park into Taman Nasional Gunung Halimun Salak (TNGHS - Mount Halimun-Salak National Park) and broadens the initial Mount Halimun NP from 40,000 ha to 113,357 ha. A small part of the TNGHS is operated by Chevron Geothermal Indonesia (CGI). Located in Mount Salak adjacent to corridor to Mount Halimun, CGI has maintained most of the natural forest in its concession. In 2006 amphibian survey was conducted in the area, mostly in the graveled path used by the workers to check on the gas pipe in several blocks. Two individuals of P. vittiger were found in one of the pond inside this area (Kusrini and Fitri 2006). Since the forest surrounding the CGI concession offers a unique opportunity to study the distribution and natural history of tree frog, we conducted additional survey starting in April 2008 to study the ecology of Philautus vittiger. Here we describe habitat requirements of P. vittiger, breeding behavior and other aspect of its reproductive biology.

Pa

ge1

8

METHODS Animal descriptions A small sized frog (mass ± 1.22 grams) where males are slightly larger than females (t35=6.959, P < 0.001). Mature male 24.8-30.2 mm SVL (n=18, mean + SD = 27.26 + 1.34 mm) and mature female 21.6-26.5 mm SVL (n=17; mean + SD = 24.05 + 1.39 mm). Table 3-1 shows different size of P. vittiger in three locations. Tympanum presents, skin smooth without supratympanic fold. Snout shorts and a bit pointed. A dark stripe occurs from eyes to the groin, mostly distinct until fore limb. Color in life varied. Dorsum pale yellow cream with a see-through quality (usually during night) sometimes with brown spots or brown bars or even totally brown. Color might change rapidly within hours, from yellow cream to yellow-brown. In the light version, fore and hind limb usually pale pink whilst the brown version usually has yellow fore and hind limb with brown bar or dark spots all over the limb. Throat to belly is white in color with the middle part to groin pinkish. Toes and fingers distinctive enlarged into flattened disc (Fig.3-1). Fingers webbed a little in the base, toes are 2/3 webbed. Fig.3-1. A variety of Philautus vittiger coloring. Picture below shows the underside (left) and

distinct shape of disc, webbed toes, tympanum (right). Table 3-1. Various size of P. vittiger from Pengalengan (Iskandar 1998), Mount Halimun (Kurniati

2003) and CGI Concession Mount Salak (Kusrini et al this report)

SVL adult (mm) Iskandar 1998 Kurniati 2003 Kusrini et al 2008 (this report)

Male 25-30

24 24.8-30.2 mm

Female 24-26 21.6-26.5 mm

Location Pengalengan Halimun CGI Concession-Salak

Pa

ge1

9

Survey & Breeding ecology

See Survey Methods in chapter-1 for distribution survey. Breeding observations were carried out from April to September 2008. We visited the breeding habitat of P. vittiger at least once a day for 3 nights and searched for newly-laid eggs. When we found such egg-masses, we recorded habitat characteristics such as heights of egg-masses positions (measured from the surface of the pond to their lower margin to the nearest 0.1 m), air and water temperature, type of water body (standing water or moving waters), type of leaves (small type leaf, big size leaves), and vegetation structure (shrubs, liana and trees). We define shrub as any woody vegetation or a woody plant having multiple stems and bearing foliage from the ground up. Trees are any woody plant, normally having one stem or trunk bearing its foliage or crown well above ground level to heights of 5 meters or more. A liana is a woody climber that starts at ground level, and uses trees to climb up to the canopy. We count the number of egg in one clutch by counting number of eggs from image or in case of eggs rearing lab by checking the number that hatch and failed. We then noted their stage of development following Gosner (1960) and mortality, if any. Each clutch’s location in the field was noted and revisited each subsequent month until September 2008. We noted the number of egg-masses present and assessed changes in egg mass development found in previous month. In total, we observed the development of four clutches in the field for a total of 10 days. The development of three clutches of eggs plus 14 tadpoles (stage 24 to 42) was observed in the Wildlife Ecology lab at the Faculty of Forestry in Bogor. The tadpoles were captured from pond- 1 and brought in to the lab on 03 June. The first clutch of eggs observed was the result of a mating of a pair of frogs that was brought back to the lab. In 29 August 2008, a pair of P. vittiger (females already gravid – eggs are visible inside the stomach) were captured and placed into a plastic bag (30 × 40 cm) together with a branch and leaves and brought into lab. In lab, the pair was put inside pet house (21x14x14 cm) in which 9 days later a clutch of eggs emerge.

The second clutch was taken from pond-1. In 29 August 2008 we carefully removed one clutch (embryonic stage 21) and placed it inside plastic buckets (210 l in volume), filled with pond water and brought to the lab for monitoring until emergence of hatchlings. The nest was placed inside a plastic box (28 x 22 x 16 cm) above the water surface on branches and leaves collected from the study site. We put bits of mud and leaf litter from its original habitat and added aquatic plants (Hydrila spp.) (Fig.3-2). In addition, one clutch consisted of 67 eggs were taken in 25 September 2008 from a pair that mate in artificial terrarium in the field-lab and reared in aquarium. Lab temperature range 24-25oC.

Pa

ge2

0

(a) (b)

Fig.3-2. (a) plastic box for tadpoles rearing and (b) a close up view of tadpoles inside the box

We measured 8 specimens of tadpole to assess morphological variability. All measurements follow Altig and Mc-Diarmid (1999) with some modification. Measurements were taken to the nearest 0.1 mm with calipers. Measurements taken included: body length (distance from the tip of the snout to end of body); tail length (the distance from body to tip of the tail); total length (the sum of body length and tail length); body width (measured at the widest point of the ‘‘head’’ right behind the eye); interorbital distance (measured between the centers of the pupils); internarial distance (measured between the centers of the nares); distance between tip of snout and naris (up to the centre of the naris); tail muscle height (including fins and caudal musculature, taken at its maximal vertical extent); oral disc width (from the widest point) (Fig.3-3). The formula of labial tooth rows follows Iskandar (1998).

Fig. 3-3. Body morphology of a tadpole (based from Dodd,Jr 2004)

Observations on breeding behavior were made at night whenever breeding occurrences is found. We recorded courtship interaction (male and female conducted pair formation and mating) and after eggs were laid, the occurrence of parental care if any. To obtain detailed information of breeding sequence we constructed artificial terrarium in base camp (about 2 km from CGI concession area). We used a 30x20x21 cm plastic box completed with aquatic plants. A quarter of box is filled with water. Two males (SVL 27.9

Pa

ge2

1

(a) (b) (c)

mm and 28.4 mm) and three females (SVL 21.6 mm, 24.4 mm and 24.3 mm) were taken at 23rd of September 2008 from two locations (a pair were taken from pond-3 and the rest were taken from pond-4). All females showed visible ova, although only one showed mature ova (big-yellowish color). One female escape after 6 hours in captivity, thus observations were made only for the remaining 4 frogs. Observations were conducted for 3 days in a row. Afterwards frogs were released back to its original habitat. Calls were recorded whenever possible using a digital recorder Edirol by Roland type R-09 with built-in microphone. A call by male on pond-5 taken at 31 May 2008 at 21.34 with air temperatures ranging from 19o-20oC was analyzed using Sound Ruler Acoustic Analysis version 0.9.6.0 (Gridi-Papp 2007). Other males nearby were also calling. RESULTS I. HABITAT No Philautus vittiger were found in streams or terrestrial habitat. The habitat of this frog is restricted in vegetation surrounding ponds (Fig.3-4). From 12 ponds that we visited, only one pond located near the tea plantation was absent. The wine colored frogs were mostly found in vegetation, either in natural (5), semi natural (5) or artificial pond (1). Most of the natural ponds have depth less than 1 m. The semi natural ponds were originated from slow moving stream impounded by the CGI management, depth around 2-3 m, in which in several parts were cemented. Tree frogs were also found in an artificial pond made from cement depth around 3 m (Table 3-2). All of the ponds except the one in tea plantation (pond-2) have similarity in which it is surrounded by dense vegetation, mostly shrubs with broad type leaves or epiphytes that inhabit moist and wet soils. Table 3-3 shows the type of vegetation used as perching site.

Fig.3-4. The habitat of Philautus vittiger at CGI concession (a) Natural pond, (b) Semi natural pond and (c) artificial pond

Frogs were mostly found at night. Males usually perched under the leaves very

near the edge of water up to 3 m above water (Fig.3-5a). Females were usually seen near the males. Leaves are not only used for perching, but to put egg clutch. All clutches were put either under the leaves or inside coiled leaves, directly above the water and protected from sun (Fig.3-5b and c). Clutches were found in the leaves of Impatiens platypetala, Eupatorium pallescen, Musa acuminata, Mikania cordata and Asplenium nidus.

Water temperatures in ponds ranged from 18.1-26°C with pH of 5.5 – 7.0. Air temperatures ranged from 17.5 - 26°C and relatively moist, ranging from 62 to 98%. The substrates of ponds were mostly consisted of decomposed leaves, most probably rich in food sources for tadpoles that inhabit the ponds, including the tadpole of P. vittiger.

Pa

ge2

2

Pond No.

Nearest landmark S E

Elevation (masl)

Category Substrat Water source Dominant vegetation Depth (m) Width dimension (longest and shortest diameter in m)

1 AWI 8-7 -6.73723 106.65462 1051 Semi Artificial mud Small stream Impatiens platypetala, Cythea sp Freycinetia javanica, Clidemia hirta

0.5-5 17 x 20

2 Tea plantation

-6.76402 106.65812 1075 Natural mud, leaf litter, and roots Small stream Tea, Sida rhombifolia, Psidium

guajava 0.3-1 7 x 11

3 nursery -6.75642 106.66363 1188 Semi Artificial mud, leaf litter, and roots Small stream Musa acuminate, Clidemia hirta, Cythea sp

0.2-0.7 18 x 9

4 Small mosque

-6.75848 106.66185 1153 Semi Artificial sand, mud Small stream Cythea sp., Clidemia hirta, 0.5-3 14 x 16

5 AWI -4 -6.73353 106.67435 1413 Natural leaf litter, mud Small stream grass, Clidemia hirta, Musa acuminate

0.2-1.3 10 x 20

6 AWI-2 -6.75242 106.66283 1221 Artificial leaf litter, mud rainfall Eupatorium inulifolium, Calliandra, Freycinetia javanica, Mikania

cordata 0.2-0.5 10 x 10

7 River in AWI -6

-6.73687 106.65828 1073 Natural Mud, gravel Small stream grass, Impatiens platypetala 0.3-1.2 3 x 5

8 AWI -14 -6.75057 106.67508 1225 Natural leaf litter, mud rainfall grass, Impatiens platypetala 0.2-0.8 6 x 4

9 AWI -14 -6.75377 106.67797 1273 Natural leaf litter, mud rainfall grass 0.2-1 3 x 5

10 Awi-14 -6.75722 106.67590 1259 Natural mud rainfall grass 0.5-1 2 x 2

11 Awi-7 -6.73537 106.64143 1047 Semi Artificial mud Small stream Calliandra sp, Clidemia hirta,

Eupatorium inulifolium 1.5-3 15 x 20

12

Between AWI -4 and Cikuluwung

-6.73335 106.67793 1413 Artificial cement, a bit mud rainfall Musa acuminate, Clidemia hirta, Cythea sp

0.3-2 4 x 8

Fig.3-5. A male Philautus vittiger perching under a leaf (a) and a coiled old leaf of Musa acuminate (b) with a

clutch of eggs inside (c)

Other than P. vittiger, other species of frogs found near the ponds are Limnonectes

microdiscus, Limnonectes kuhlii, Fejervarya limnocharis, Rana chalconota, Rana nicobarensis, Microhyla achatina, Microhyla palmipes, Polypedates leucomystax, Rhacophorus reinwardtii, and Rhacophorus javanus. Several tadpoles were seen, mostly from species such as Rana chalconota, Microhyla palmipes, Leptobrachium hasseltii, and Rhacophorus javanus. In pond-1 several fishes were seen.

Table 3-2. Pond characteristics in Chevron Geothermal Indonesian Concession Mount Salak

Table 3-3. Vegetation used as perching site by Philautus vittiger at CGI-Salak concession No Local name Latin name Category

1 Pacar tere Impatiens platypetala Shrub

2 Kirinyuh Eupatorium pallescen Shrub

3 Pisang hutan Musa acuminate Shrub

4 Resam Dicranoteris linearis Shrub

5 Sereh tangkal Piper anducum Shrub

6 Paku sarang burung Asplenium nidus Liana

7 Sangketan Achyranthes bidentata Shrub

8 Areuy capituheur Mikania cordata Shrub

9 Prasman Eupatorium triplinerve Shrub

10 Ganda Rusa Justica gendarrusa Shrub

11 Paku2an Nephrolepis biserrata Shrub

(a) (b) (c)

Pa

ge2

3

II. BREEDING ECOLOGY 2.1 Breeding Season

Males were found calling in all observed locations during the six month observation periods. Twenty six egg-clutch sites were found in five locations: pond-1, pond 3, pond 4, pond-6, where most of it (total 17 clutches, 3-4 clutch per month) were found mainly in pond-1. Eggs were found in all months, however the number of eggs found in each ponds were variable (Fig.3-6). For example in pond-1, during the six month period, no clutch were found in September, however the highest number of clutch found was in May (5 clutches). Females attending breeding sites were either taking care of the clutch (no visible ova in her stomach) or ready to breed, which showed by having visible ova in her stomach. Ripe ova were usually large and yellowish in color, whilst unripe ova were usually smaller size than ripe ova and greenish in color (Fig. 3-7).

Fig.3-6. Number of Egg clutches observed at CGI ponds from April to September 2008

(a) (b)

Fig.3-7. A female Philautus vittiger with visible ripe ova (a) and unripe ova in her stomach (b)

Pa

ge2

4

Fig.3-8. Eggs started to hatch

2.2 Eggs Number of eggs in one clutch is variable. Breeding female will lay all of her eggs, clumped into a single clutch during amplexus (diameter of clutch 13.5 mm for stage 11 to 26.98 mm for stage 22). Mean number of eggs in one clutch is 52 (n = 12; range: 37 – 66 eggs, SD= 8.25). Eggs are un-pigmented, pale yellow in color and coated by sticky jelly substance (see Fig.10). The diameter of egg is 3.98 mm (stage 11, N = 1) to 4.96 (stage 21, N=1). Height of nest position above the pond water ranged from 0.2 to 2.5 m (n = 22, mean = 1.47 m, SD = 0.92 m). 2.3 Embryonic development Fertilized eggs will hatched after about 16 days. Tadpoles will emerge as stage 25 and slide to water below the leaves (Fig.3-8). Tadpoles will stay in stage 25 for quite some time (48 days the fastest), growing its body before moving to the next stage. After about 2 months tadpole will be in stage 26-36 where hind limb develop. In the next 20 days, front limb will emerge. It takes about 3 months for an egg to be a fully metamorphosed frog (Table 3-4, Fig.3-10).

Two experiments to rear newly fertilized eggs in the lab were all unsuccessful (Appendix-1 and 2). Eggs guarded by its mother survived until stage 17, but after attacked by mold the mother left and afterwards both mother and eggs died. Another clutch of newly fertilized eggs taken from field-lab without its parent died in 3 days. Rearing tadpoles and near-hatched eggs were more successful than rearing new-laid eggs. Although our first attempt to grow tadpole ended with only one tadpole survive to stage 43, however our second attempt to rear stage 23-24 eggs (near hatching period) resulted in much better situation (see Appendix 3 and 4). At least 28% of eggs still survived as tadpoles until the 4th of December 2008. Fig. 3-9 shows the number of eggs reared in lab from a clutch taken at 29th of August 2008.

Pa

ge2

5

Fig.3-9. Number of Philautus vittiger embryo survived as larvae from lab experiment.

Table 3-4. Embryonic development in P. vittiger based from field and laboratory observation. Development duration of each eggs varied, data below shows the fastest development duration Developmental Duration (day)

Day after

egg laid

Stage Development character

2 0 1-13 Un-pigmented eggs started to develop 3 2 14-18 Embryo elongated, distinct shape of head

and tail 6 5 19- 20 Tail more developed and longer, gills

distinct 5 11 21- 24 Cornea transparent, operculum develop 48 16 25 Eggs hatched, tadpole went down from

leaves to the water below. Tadpoles increase its body size

10 64 26- 36 Hind limb bud develop but toes not yet distinctive

8 74 37- 40 Hind limb developed, individual toes look distinct

4 82 41 Fore limb bud developed 1 86 42 Fore limb more developed, oral disc

began to change shape. 1 87 43 Tail length diminishes. Changes in mouth

part apparent 1 88 44 Head and mouth longer 2 89 45 Head shape similar to adult shape, tail

absorbed and nearly gone - 91 46 Juvenile stage, metamorphosis concluded

Pa

ge2

6

Stage 37

Stage 25 Stage 21

Stage 1 Stage 16-18

Stage 20

Stage 38 Stage 41

Stage 42 Stage 44

Adult

Stage 13-15

Stage 45

Stage 43

Stage 46

Fig.3-10. Development of newly fertilized eggs of Philautus vittiger into a fully metamorphose frog.

Pa

ge2

7

2.4 Description of tadpole In dorsal view, body oval, snout rounded. Eyes dorsal, directed laterally, not visible from below. Nostril small, dorsolateral, positioned closer to the snout than to the eyes. The internarial distance is about 50 % of the interorbital distance. The tail musculature is strong, in the distal third of the tail the musculature is gradually tapering and almost reaches the tail tip. Dorsal fin does not extend onto the body; a broader than ventral fin. Dorsal fin expands after one third of tail length, where it becomes the point of maximum fin height. Dorsal fin will gradually tapering in the last 1/3 of length. Spiracle is sinistral, visible from above and below. Anus dextral. Tail length 1.4-2.0 times body length. Dorsal surface of tadpole is transparent brown, head and body with plenty dark mottled but becoming lightly to tail. Ventral surface are mostly transparent (see Fig. 3-11). Mouth directed downwards with flattened throat. Oral disc medium, extending definitely beyond the lower jaw. The upper (suprarostral) and lower (infrarostral) supportive jaw cartilages have pigmented and keratinized jaw sheaths. The relative amount of dark keratinization (width in longitudinal dimension) in the sheath is about half the width (medium). Margin of oral disc is emarginate. Upper sheath with broad arch, lower sheath V-shaped; margins of upper and lower jaw sheaths cuspate, rounded. Marginal papillae have a dorsal gap. Size varied according to its Goner stage. At stage 25, the total length of tadpoles range from 1.5-2.6 cm. In this stage, tadpole has labial teeth formula of I+4-4/III or II+4-4/III (Fig.3-12). Morphometric measurements of eight Philautus vittiger tadpole specimens from stage 21 to 46 are given in Table 3-5.

Fig.3-11. The characteristic of Philautus vittiger tadpole

Pa

ge2

8

Fig.3-12. Labial teeth of Philautus vittiger tadpole Tabel 3-5. Morphometric measurement of eight Philautus vittiger tadpoles taken from

different ponds at CGI concession in Mount Halimun-Salak National Park. All measurements are in mm.

NO STAGE TL BL TAL BW MTH TMH TMW IOD IND ODW

1 41 25.72 8.42 15.62 5.52 5.02 2.72 2.22 4.12 2.02 3.24

2 28 25.74 9.22 16.08 6.02 4.54 2.22 1.92 4.42 2.42 2.68 3 38 30.32 10.54 20.02 6.64 4.78 2.88 2.32 5.14 2.82 2.72

4 28 27.06 9.42 18.84 6.32 5.42 2.56 2.00 4.44 2.40 3.50 5 36 28.42 10.22 17.32 6.00 5.52 2.42 1.88 4.42 2.76 3.34

6 26 24.12 9.62 13.32 5.32 3.92 2.20 1.82 3.94 2.24 3.06 7 28 25.00 8.74 14.82 5.62 4.32 2.22 1.64 4.10 2.04 2.86 8 38 22.42 9.82 12.14 5.90 4.84 2.42 1.88 4.54 2.32 3.60

Note : TL: Total Length; BL: Body Length; TAL: Tail Length; BW: Body Width; MTH: Maximum Tail Height; TMH : Tail Muscle Height; TMW: Tail Muscle width; IOD: Inter Orbital Distance; IND: Inter Narial Distance; ODW: Oral Disc Width

Pa

ge2

9

2.5 Breeding behavior

No amplexus behavior was observed in the wild. Although no amplexus activity were seen during field work, we have encountered 5 pair of frogs sitting closely near each other, apparently in the middle on mating activity. Observation described here are based on a pair of female and male in terrarium which amplexed in 25 September 2008. In addition, a pair of frogs was in the same terrarium. Courtship began a day before with a male choose the widest leaf which situated directly on top of water and calling under the leaf at 22:00 and a female with visible ripe ova in her belly advancing toward him (Fig.3-13a). Both male and female were then sitting near to each other (3 cm apart) but no amplexus were seen. The male continuously called until 5:00 and during the day both were seen resting close together until dusk in which female moved around occasionally to water and leaf. At 18:30 the male started to call again and continued calling until 01.00 whereupon the previous female advanced him and check suitable location in the leaf to deposit her eggs and sat in the selected location. At 01:10 calling male advanced toward a non-calling male however after 10 seconds left the male and approaching the female and shortly after engaged to axillary amplexus (Fig. 3-13b&c). During amplexus male stopped calling. A non calling male in the terrarium approached the amplexus pair in 01:29 during which female laid her eggs. Adhesive, yellow colored eggs were laid for 26 minutes whilst both males seemingly fertilized it (Fig.3-13d). After eggs were laid (01:55) the first male soon departed the female, however the second (non calling) male stayed close until the next 32 minutes (Fig.3-13f). Female sat on her eggs for about 3 hours but intermittently leave. On 03.03 the first male called from near the water (a third of his body submerged in water) (Fig. 3-13g.) then the waiting female left her eggs did the same thing as the male. At 04.11 the female left the water and back to the eggs (Fig.3-13h) whilst male continuously calling until 5a.m. In the next 23 minutes, female were seen on top of the eggs and rubbing her wet hind legs until 04.34 (Fig.3-13i). During the day, female rest closely nears the eggs.

2.6 Advertisement Call The advertisement call of the Philatus vittager recorded on 31 May 2008, 09.34 pm, air temperature 19-20oC was composed of two notes, or clicks of approximately 0.026 second duration, spaced 0.658 seconds apart. The peak frequency of each note was 2.93 kHz (Figure 3-14). The calls were easily heard from a distance of more than 20 m.

Pa

ge3

0

(a

) (b

) (c

)

(d

)

(e

)

(i)

(f)

(g

) (h

)

Fig. 3-13. Breeding sequence of Philautus vittiger. Fig. 3-14a was taken in the natural habitat while the other figures showed mating sequence inside field terrarium. Non calling male have darker coloring than the other frogs. Figure 3-13.f also shows the other female (non-breeding – color pale cream) resting in the same leaf. Fig.3-14. (a) An oscilogram of the entire section showing one call group, (b) an oscillogram of the call section showing a single pulsed call from the call group in green bracket in (a), (c) Spectrogram of the pulsed call shown in (b), (d) Power spectrum generated over the peak of the call shown in (b). Un-vouchered male. Record was taken 31 May 2008 at pond-5 at 09.34pm. Air temperature 20oC

Pa

ge3

1

(a) (b)

(a) (b)

(c) (d)

2.7 Parental care Parental care in the wild is obvious in this species. Most of the non-breeding females were usually located near the eggs during the day although they are mostly non-conspicuous. During night female will occasionally sat on top of its eggs and wiping her hind legs (Fig.3-15). Of the total 17 eggs clutch, 10 clutches were guarded by a female. A male usually sat nearby but never as close as the female. These males usually call and when researchers walk near its location it will increases the tempo of the calls.

Fig.3-15. Two different females Philautus vittiger from pond-1 in 28 May 2008 guarding its eggs (a) a female sitting on top of its eggs and (b) a different female wiping her hind feet on top of its eggs

At least five out of seven clutches unguarded were attacked. Four clutches were attacked by ants and fungal infestations (Fig.3-16b, c, d) in which the eggs either rot, discolored or dried up. In one occasions, a clutch of eggs was finally left by the guarding female because of caterpillar attacks. A newly laid clutch of eggs was found at 28 May 2008 in pond-1 at 19.30. The next day at 21.30 a female were seen guarding the eggs, however on 3rd June 2008 the leaf where the eggs situated was eaten by caterpillar so the eggs only hang in small thread and the mother is not seen nearby (Fig.3-17a). There is a possibility that the eggs will survive since the embryos were already in stage 21.

Fig.3-16. Unguarded dead eggs found during survey. (a) A clucth of eggs hanging by a thread where leaf was eaten by caterpillar, (b) eggs attacked by ants, (c & d) two different clucthes attacked by fungus

DISCUSSIONS Ponds are important for biodiversity conservation (Oertli et al 2002), especially for amphibians since it provides potential breeding habitat for several species. The use of several type of ponds (artificial or temporary) frog breeding habitat has been studied by many scientist, for instance by Hazell et al (2001) who studied the use of farm dams by

Pa

ge3

2

frogs and Griffiths (1997) who reviewed the use of temporary ponds by British species. Result from this research shows that the development of artificial and semi-artificial ponds by the CGI managements has benefit the wine colored frogs by providing suitable breeding habitat for this species. However, it is clear from observation that one of the main characteristic needed for pond to serve as breeding habitat is the availability of emergent vegetation in the margin of aquatic and terrestrial zone as noted by Hazell et al (2001) and DiMauro & Hunter (2002). These vegetations serve as oviposition site where hatched eggs will be able to move straight into water below. Compared to other species of tree frog found in Java, the oviposition site of P. vittiger differs from Rhacophorus reinwardtii or Polypedates leucomystax which both have eggs inside foam nest. Although R. reinwardtii oviposit in leaves as of P. vittiger, however this frog also lays its foam nest in the ground (Yazid 2006) while P. leucomystax oviposit in leaves or even in the walls of artificial ponds (Sholihat 2007). Both R. reinwardtii and P. leucomystax also oviposit in temporary ponds (Yazid 2006, Yorke 1983) compared to P. vittiger which only found in permanent ponds. The selection of pond type (permanent vs. ephemeral) might refer to phenotypic plasticity of tadpole to metamorphose during desiccation (Griffiths 1997). Pond’s frog ecological research in Indonesian has been conducted for several species such as Fejervarya cancrivora, F. limnocharis, R. chaconota, R. erythraea, Occidozyga lima, and M. achatina which inhabits artificial ponds in Cibodas Botanical Garden in West Java (Premo 1985, Mumpuni et al 1990, Erftemeijer & Boeadi 1991), mostly on its diet and reproductive ecology. However, except for R. reinwardtii in which breed in ephemeral ponds (Yazid 2006), no other study has been conducted on reproductive behavior of the pond species in Indonesia. Although we only observed six month period, there is no apparent breeding season of P. vittiger. Both male call and eggs clutch were observed every time survey was carried out in each month. However, it seems that breeding peak will coincided with the timing of rain, as observed by other researchers working on other tropical species (Church 1960, 1961, Inger & Bacon 1968, Premo 1985, Jaafar 1994). The intrusion of other male during amplexus of P. vittiger in this research shows the instance of mate piracy that also occur in other species (Byrne and Roberts 1999, Davis and Roberts 2004, Vieites et al 2004). Yazid (2006) reported the unsuccessful attempt of other non-selected male to engage in the mating process during amplexus of a pair of R. reinwardtii in Bogor which was ousted by the pair. However, we have seen a female of R. reinwardtii during oviposition with three males on her back in Bodogol at Mount Gede Pangrango National Park (Kusrini, unpublished data) without apparent act of protestation. No aggressive behavior is obvious during the intrusion of other male of P. vittiger in our observation. Since we were unable to observe amplexus in the wild, we are unsure if this kind of polyandrous mating and non-resistance behavior of the paired frogs to the other male is common in this frog. The genus Philautus is characterized by direct development in which eggs develop into froglets without an aquatic stage of tadpole (Bossuyt and Dubois 2001). The result of this survey reveals that Philautus vittiger have a free tadpole stage, contrary to the characteristic of the genus. Therefore, in our opinion, there is a need to review the taxonomy of this species and exclude this species from Philautus genus.

Pa

ge3

3

Although we are unable to quantify the survival of embryo to hatching period through metamorphosis stage, however it is clear that development of embryo during pre-hatching are vulnerable to risk of predation by ants and desiccation. Our laboratory work shows that rearing newly fertilized eggs proved unsuccessful without the attendance of its parent. Unattended eggs might have up to 100 % mortality compared to attended eggs. Hatched tadpole that had difficulty of sliding to water (and stuck in the leaf) might eventually die as shown in our laboratory development. Rainfall might be helpful during the hatching periods by providing escape route to water. Newly hatched larvae ate attached algae, however as their body grows tadpoles also ate Tubifex and body parts of their dead conspecific (see appendix). The food habit of P. vittiger is apparently similar to Polypedates leucomystax who also ate the carcass of the conspecific tadpole (Alcala 1962, Yorke 1983). Other research elsewhere has shown that parental cares were mostly in form of egg attendance (Wells 1977), with the intention of reducing risk of embryo mortalities (Taigen et al 1984, Croshaw and Scott 2005). Eggs might be defended by male, female or both (Wells 1977). In the case of P. vittiger parental females seems to have more role in guarding eggs, although parental males are also seen nearby. It is not clear whether males have roles in guarding eggs or rather guarding its territories. There are not many reports on parental care behavior of Indonesian species. Parental behavior of two species of frogs were observed in two species of frogs in Sulawesi which are Rana arathonii (Brown and Iskandar 2000) and Limnonectes modestus (Lubis et al 2008). In both species, male individuals were seen guarding clutch of eggs in terrestrial nest (R. arathoonii) and in leaf (L. modestus). The wiping of eggs by the hind limb by its guardian is presumably to maintain the moisture of its eggs. Maintaining moisture behavior is also observed by other species such as Dendrobates pumilio in which males urinating on its eggs (Weygoldt 1980) and males Chirixalus effingeri (Chen et al 2007) from Taiwan in which used its ventral surfaces.

The distribution of Philautus vittiger in CGI concession is relatively broad. Since there is no previous report on the preceding population, we could not conclude the population status of this species. However, by looking at the number of individual and breeding activity found during the survey we assumed that the current population in CGI is quite healthy. To ensure the population of this frog, the ponds where P. vittiger occur should be maintained. Care needs to be taken by not disturbing vegetation surrounding the area. Pond-1 has the highest number of clutch found during the survey, although we found evidence of fish in this area. Discussion by the workers revealed that fishes were brought from outside since the pond, due to its easy access (on side of the road), is popular for recreational fishing among workers. There are several reports that implicate the occurrence of fish to the reduction of frogs species elsewhere (Bronmark & Edenham 1994, Gillespie & Hero 1999, Knapp & Matthews 2000), thus we advice the management to prohibit the introduction of fish to the ponds. LITERATURE CITED Alcala, A. C. 1962. Breeding behaviour and early development of frogs of Negros,

Philippine islands. Copeia 1962(4): 679 - 726. Altig, R., R.W. McDiarmid, K.A. Nichols, P. A. Ustach. Tadpoles of the United States and

Canada: A Tutorial and Key (In preparation). Accessed at http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/tadpole/division_5.htm on 10 September 2008.

Pa

ge3

4

Byrne, P. G. and J. D. Roberts. 1999. Simultaneous mating with multiple males reduces fertilization success in the myobatrachid frog crinia georgiana. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 1999(266): 717-721.

BrÖnmark, C. and P. Edenham. 1994. Does the presence of fish affect the distribution of tree frogs (Hyla arborea)? Conservation Biology 8(3): 841-845.

Brown, R. M. and D. T. Iskandar. 2000. Nest site selection, larval hatching, and advertisement calls, of Rana arathooni from southwestern Sulawesi (Celebes) island, Indonesia. Journal of Herpetology 34(3): 404-413.

Bossuyt, F. and A. Dubois. 2001. A review of the frog genus Philautus Gistel, 1848 (amphibia, anura, ranidae, rhacophorinae). Zeylanica 6(1): 1–112).

Chen, Y-H., H-T. Yu, Y-C.Kam. 2007. The Ecology of Male Egg Attendance in an Arboreal Breeding Frog, Chirixalus eiffingeri (Anura: Rhacophoridae), from Taiwan. Zoolog.Sci. 24 (5): 434-440

Church, G. 1960. The effects of seasonal and lunar changes on the breeding pattern of the edible Javanese frog, Rana cancrivora Gravenhorst. Treubia 25(2): 215-233.

Church, G. 1961. Seasonal and lunar variation in the numbers of mating toads in Bandung (java). Herpetologica 17(2): 122-126.

Croshaw, D. A. and D. E. Scott. 2005. Experimental evidence that nest attendance benefits female marbled salamanders (Ambystoma opacum) by reducing egg mortality. Am. Midl. Nat. 154: 398–411.

Davis, R. A. and J. D. Roberts. 2005. Embryonic survival and egg numbers in small and large populations of the frog Heleioporus albopunctatus in western australia. Journal of Herpetology 39(1): 133-138.

DiMauro, D. and M. L. Hunter Jr. 2002. Reproductions of amphibians in natural and antropogenic temporary pools in managed forest. Forest Science 48(2): 397-406.

Dodd, Jr., C. K.. 2003. Monitoring amphibians in Great Smoky Mountains national park. U.S. Geological survey circular 1258. Tallahassee, Florida, U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey: 118 pp.

Gosner, K. L. 1960. A Simplified Table for Staging Anuran Embryos and Larvae with Notes on Identification. Herpetologica 16(3): 183-190.

Ertftemeijer, P. and Boeadi. 1991. The diet of Microhyla heymonsi Vogt (microhylidae) and Rana chalconota (ranidae) in a pond of west java. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 39(1): 279-282.

Gillespie, G. and J-M. Hero. 1999. Potential impacts of introduced fish and fish translocations on australian amphibians. In: A. Campbell (eds) Declines and disappearances of Australian frogs. Canberra, Environment Australia: 131-144 pp.

Gridi-Papp M. 2007. Sound ruler. Acoustic analysis. Version 0.9.6.0 ed. Available free from: http://soundruler.sourceforge.net. Accessed on Dec 9, 2008.

Griffiths, R. A. 1997. Temporary ponds as amphibian habitats. Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 7: 119-126.

Hazell, D., R. Cunnningham, D. Lindenmayer, B. Mackey and W. Osborne. 2001. Use of farm dams as frog habitat in an australian agricultural landscape: Factors affecting species richness and distribution. Biological Conservation 102: 155-169.

Inger, R. F. and J. P. Bacon Jr. 1968. Annual reproduction and clutch size in rain forest frogs from Sarawak. Copeia 1968(3): 602-606.

Iskandar, D. T. 1998. Amfibi Jawa dan Bali – Seri Panduan Lapangan. Puslitbang – LIPI. Bogor.

IUCN 2007. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed at <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 14 July 2008.

Jaafar, I. H. 1994. The life history, population and feeding biology of two paddy field frogs, Rana cancrivora Gravenhorst and R. limnocharis Boie, in Malaysia. Doctor

Pa

ge3

5

of Philosophy Thesis. Faculty of Science and Environmental Studies, University Pertanian Malaysia, Malaysia. 228 pp.

Knapp, R. A. and K. R. Matthews. 2000. Non-native fish introductions and the decline of the mountain yellow-legged frog from within protected areas. Conservation Biology 14(2): 428-438.

Kusrini, M. D. and A. Fitri. 2006. Ecology and conservation of frogs of mount Salak, West Java, Indonesia. Final report submitted to the wildlife trust. Bogor, Institut Pertanian Bogor: 30pp.

Kurniati, H. 2003. Amphibians and Reptile of Gunung Halimun National Park West Java, Indonesia (Frog, Lizard and Snake). Cibinong : Puslitbang Biologi LIPI.

Lubis, M. I., W. Endarwin, S. D. Reindriasari, Suwardiansah, A. U. Ul-Hasanah, F. Irawan, H. A. Karim, and A. Malawi. 2008. Conservation of Herpetofauna in Bantimurung Bulusaraung Nasional Park, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Final report submitted to CLP.

Mumpuni, I. Maryanto and Boeadi. 1990. Studi pakan katak Microhyla achatina (Tschudi) dan Hylarana chalconota (Schlegel) di kebun raya Cibodas, Jawa Barat. Pros. Sem. Biol. Das. I: 108-112.