Treatment of Myocardial Infarction United States to · 2104 Circulation Vol 90, No4 October 1994...

Transcript of Treatment of Myocardial Infarction United States to · 2104 Circulation Vol 90, No4 October 1994...

2103

Treatment of Myocardial Infarction in theUnited States (1990 to 1993)

Observations From the National Registryof Myocardial Infarction

William J. Rogers, MD; Laura J. Bowlby, RN; Nisha C. Chandra, MD; William J. French, MD;Joel M. Gore, MD; Costas T. Lambrew, MD; R. Michael Rubison, PhD; Alan J. Tiefenbrunn, MD;W. Douglas Weaver, MD; for the Participants in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction*

Background Multiple clinical trials have provided guide-lines for the treatment of myocardial infarction, but there islittle documentation as to how consistently their recommen-dations are being implemented in clinical practice.Methods and Results Demographic, procedural, and outcome

data from patients with acute myocardial infarction were col-lected at 1073 US hospitals collaborating in the National Registryof Myocardial Infarction during 1990 through 1993. Registryhospitals composed 14.4% of all US hospitals and were morelikely to have a coronary care unit and invasive cardiac facilitiesthan nonregistry US hospitals. Among 240 989 patients withmyocardial infarction enrolled, 84 477 (35.1%) received throm-bolytic therapy. Thrombolytic recipients were younger, morelikely to be male, presented sooner after onset of symptoms, andwere more likely to have localizing ECG changes. Among the60 430 patients treated with recombinant tissue-type plasmino-gen activator (rTPA), 23.2% received it in the coronary care unitrather than in the emergency department. Elapsed time fromhospital presentation to starting rTPA averaged 99 minutes(median, 57 minutes). Among patients receiving thrombolytictherapy, concomitant pharmacotherapy included intravenous

Acute myocardial infarction, the most commoncause of death in most Western industrializedcountries, has received considerable clinical

research emphasis over the past decade. To examine theimpact of new pharmacological and invasive therapy,hundreds of thousands of patients have been enrolled inwell-designed, randomized clinical trials,1 and manyuseful guidelines for management of patients with acutemyocardial infarction have been formulated.1'2

Received March 23, 1994; revision accepted June 27, 1994.From the University of Alabama Medical Center, Birmingham

(W.J.R.); Genentech, Inc, South San Francisco, Calif (L.J.B.);Francis Scott Key Medical Center, Baltimore, Md (N.C.C.);Harbor UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, Calif (W.J.F.); Univer-sity of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester (J.M.G.); MaineMedical Center, Portland (C.T.L.); ClinTrials Research, Inc,Lexington, Ky (R.M.R.); Washington University School of Medi-cine, St Louis, Mo (A.J.T.); and University of Washington MedicalCenter, Seattle (W.D.W.).The National Registry of Myocardial Infarction is supported by

Genentech, Inc, South San Francisco, Calif.Correspondence to William J. Rogers, MD, 334 LHR Bldg,

UAB Medical Center, Birmingham, AL 35223.*A complete listing of participating registry hospitals is avail-

able from ClinTrials, Inc, Lexington, KY 40504.C 1994 American Heart Association, Inc.

heparin (96.9%), aspirin (84.0%), intravenous nitroglycerin(76.0%), oral ,3-blockers (36.3%), calcium channel blockers(29.5%), and intravenous ,3-blockers (17.4%). Invasive proce-dures in thrombolytic recipients included coronary arteriography(70.7%), angioplasty (30.3%), and bypass surgery (13.3%).Trend analyses from 1990 to 1993 suggest that the time fromhospital evaluation to initiating thrombolytic therapy is shorten-ing, usage of aspirin and 13-blockers is increasing, and usage ofcalcium channel blockers is decreasing.

Conclusions This large registry experience suggests thatmanagement of myocardial infarction in the United Statesdoes not yet conform to many of the recent clinical trialrecommendations. Thrombolytic therapy is underused, partic-ularly in the elderly and late presenters. Although emergingtrends toward more appropriate treatment are evident, hospi-tal delay time in initiating thrombolytic therapy remains long,aspirin and 13-blockers appear to be underused, and calciumchannel blockers and invasive procedures appear to be over-used. (Circulation. 1994;90:2103-2114.)Key Words * thrombolysis * clinical trials * angiography

*pharmacology

However, there is only limited documentation on howpatients with acute myocardial infarction are actuallybeing managed in the United States3'4 and how consis-tently the results of recent clinical trials are beingimplemented in clinical practice. Some have reportedthat practice patterns change gradually, over a period ofyears, following new recommendations from clinicaltrials.5'6 The National Registry of Myocardial Infarctionis an ongoing national database that, since September1990, has tracked practice patterns and outcome ofmore than 240 000 patients with acute myocardial in-farction enrolled at selected hospitals throughout theUnited States. The purpose of this article is to reportthe initial findings of this ongoing registry, to contrastpatients receiving thrombolytic therapy with those notreceiving it, and to compare US acute myocardialinfarction management, as documented in this registry,with recommendations from recent clinical trials.

MethodsPurpose of the RegistryThe National Registry of Myocardial Infarction is a phase

IV (postmarketing), observational, collaborative endeavorsponsored by Genentech, Inc, in which contributing hospitals

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

2104 Circulation Vol 90, No 4 October 1994

throughout the United States record demographic, proce-dural, and outcome data on patients with acute myocardialinfarction. The purpose of the registry is to collect uniform,prospective data on the treatment of patients with acutemyocardial infarction that (1) can be used globally to analyzenational practice patterns for infarct treatment, (2) can beused locally to assess individual hospital practice patterns andoutcome to facilitate the continuous quality improvementprocess, and (3) can be used by the sponsor to monitor thefrequency of specific adverse events with the use of theirproduct, recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator(rTPA) (Activase).

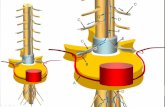

Data Collection ProcessA registry coordinator at each participating hospital records

data from each patient onto a simple one-page data form (seeFig 1), which is then sent to a central data collection center(ClinTrials Research, Inc, Lexington, Ky) for processing andanalysis. Participating hospitals receive quarterly summaries ofthe cumulative study-wide registry data together with confi-dential, individualized, parallel tabulations of their local data.(A complete listing of contributing registry hospitals is avail-able from ClinTrials Research, Inc).

Participation in the registry is entirely voluntary, and hospitalsare encouraged to enter consecutive infarcts irrespective oftreatment strategy and outcome. During the enrollment periodof the recently concluded Global Utilization of Streptokinase andtPA for Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) trial7 (December1990 to February 1993), hospitals participating in both theregistry and the GUSTO trial were asked not to enter GUSTOparticipants in the registry so that the registry would betterreflect actual clinical practice rather than treatment mandated bya clinical trial protocol. Approval of the registry data collectionprocess at participating hospitals may include review by institu-tional committees on human research as dictated by local poli-cies. Demographic data characterizing registry hospitals in com-parison to all other US hospitals are obtained from SMGMarketing Group, Inc (Chicago, Ill).

Quality ControlBefore initiation of the registry, the clinical coordinator at

each site received a training manual that explained how tocomplete the case report form, defined each variable, andprovided examples of correct responses. Double-key entry is usedby the data collection center to add each case report form to thedatabase. Audits are performed electronically to detect out-of-range variables, inconsistencies, errors, and omissions. Queriesare then telephoned to local registry coordinators for resolution.Periodic regional meetings of registry coordinators and investi-gators are held to discuss data entry and registry findings.

DefinitionsTo be included in the registry, patients must have acute

myocardial infarction documented according to local hospitalcriteria, usually by cardiac enzymes (total or MB creatinekinase), ECG, or cardiac angiography. Time of "chest painonset" is defined as the time when chest pain intensified orbecame prolonged or intolerable such that the patient decidedto seek treatment. Time of "initial presentation" is defined asthe time of patient arrival at the registry hospital or at areferral hospital if that was earlier. "Transferred patients" arethose who are transferred to a registry hospital from a referralhospital. Patient initials and birth dates are recorded toprevent "double counting" of patients who might have beentransferred from one registry hospital to another. A "nondi-agnostic ECG MI" includes nonspecific ST or T-wave abnor-malities or no ECG evidence of myocardial infarction. The"standard dose" of rTPA (Activase, alteplase) is 60 mgadministered in the first hour, of which 6 to 10 mg is given asa bolus, 20 mg over the second hour, and 20 mg over the thirdhour. Among the reasons for not using rTPA, "physician

preference" is coded if none of the other reasons applied.Concomitant medications, invasive procedures, and adverseevents are recorded if they are implemented or occur at anytime during the hospitalization. "Peri-MI arrhythmias" in-clude any arrhythmia occurring within 24 hours of the indexinfarction. "Drug-induced hypotension" is hypotension requir-ing fluid replacement therapy.

Statistical MethodsGroup differences were assessed by the X2 test for categor-

ical variables, by the two-sample t test for age and weight, andby the Wilcoxon test for time intervals. All reported P valueswere two-sided and were not adjusted for multiple testing. Allstatistical analyses were performed with SAS 6.06 statisticalpackage programs (SAS Institute). This report is based ondata processed by the central data collection center as ofDecember 31, 1993.

ResultsAcquisition of Patients and HospitalsFrom September 1990 to December 1993, 240 989

patients with myocardial infarction were enrolled from1073 contributing registry hospitals throughout theUnited States (Figs 2 and 3). Enrollment continues andis currently proceeding at a rate of approximately 10 000patients per month.

Registry Hospital CharacteristicsThe current 1073 registry hospitals compose 14.4% of

all 7458 US hospitals (Table 1). Registry hospitals aresignificantly larger, more likely to be certified by theJoint Commission on Accreditation of Health CareOrganizations, more likely to be affiliated with a medi-cal school and to have a residency teaching program,and more likely to have an active emergency depart-ment, coronary care unit, cardiac catheterization labo-ratory, and cardiac surgery program than nonregistryhospitals.

Patient CharacteristicsOf the 240 989 patients enrolled, 84 477 (35.1%)

received thrombolytic therapy. The thrombolytic agentwas rTPA in 72% (60 430) of the thrombolytic recipi-ents, higher than the 56% national average for rTPAduring the same time frame (IMS America, PlymouthMeeting, Pa). Patients receiving thrombolytic therapy(any agent) were significantly younger than those notreceiving thrombolytic therapy (Table 2). The propor-tion of patients treated with thrombolytic therapy di-minished progressively after age 50 years (Fig 4).Among patients <60 years old, 50% received thrombo-lytic therapy, whereas among patients .60 years old,thrombolytic therapy was used in only 28% (P<.001).

Patients receiving thrombolytic therapy weighedmore, were more likely to be men, and were more likelyto have been transferred to the registry hospital fromanother hospital (Table 2). Patients receiving thrombo-lytic therapy were more likely to have ECG evidencelocalizing the infarction to the anterior, inferior, lateral,or posterior wall and less likely to have a nondiagnosticECG or evidence of non-Q-wave infarction than thosenot treated with thrombolytic therapy.The median time interval from chest pain onset to

arrival at the initial hospital was 95 minutes for patientstreated with thrombolytic therapy, 180 minutes forthose not treated with thrombolytics (P<.001), and 130

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Rogers et al National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2105

Patient Demographics Initials L lii Sex L Birth Date Weight llibs D kgsF M L MIzF M D Y (Estimated)

Patient Presentation Profile Chest Pain Onset DateL Z ZL Z TimneLii 111M Dy 24-hr. cl~~~~ock

Presentation (or arrival if transfer) Date L L L Time L Z Lii lM Dy ~~~~~~~~~~24-hr.clock

Interhospital Transfer Was patient transferred? Y/N If YES, co lete the followinReferring Hospital ID# Initial Presentation Date L Time L

M D Y 24-hr. cbckIf no ID#, NameTransportation Initiated Date MIL Time LIZ :LIZM D Y 24-hr. cbockMethod of Transportation E Ambulance El Helicopter El Other (specify)

Method of Ml Diagnosis E Initial ECG E STAT CK El Angiography(check all that apply) E Subsequent ECG El Serial CK

E Other (specify)Infarct Location E Anterior (V1, V2, V3 and/or V4) E Lateral (I and AVL) El Subendocardial(check all that apply) E Inferior (11, Ill and/or AVF) E Posterior (Large R in Vl or Q in V6)

E Non-diagnostic ECG Ml E Other (specify)Activase Treatment If YES, complete the followin If NO, check all that apply:

Total Dose LIEIIIi.O mgs Standard dose and regimen ZYV/N Age over 75 After 6 hoursBolus LIJIIL. mgs. Weight-adjusted dose LYIN EPrimary angioplasty EOther thrombolytic1st hour 1 iZLI mgs. Front-loaded dose L YIN E Patient refusal (specify)_l(induding bolus) El Physician preference E Contraindication

Activase Infusion Initiated DateL LI Time L : L Site El ED E CCU s(fill in blanks and check) M D Y 24-hr. cbck

(s Referring Hospital E Receiving Hospital E During Transport

Concomitant Medication El IV Heparin Date started LIZ Time L mLI(check all that apply) M D Y 24hr. cbc

El Inotropic agent E Oral beta-blocker E Calcium channel blockerEl IV beta-blocker E Aspirin E IV nitroglycerin

Additional Procedures PerformedCardiac Catheterization L Y/N Infarct artery: Patent l Y/N Angioplasty YIN |If YES, Date [IeI 2- c(Prior to angioplasty) Bypass Surgery L I /N

Clinical Course Minor surface bleeding AdverseEvents A Major bleeding (intracranial,(check all that apply) E Peri-MI arrhythmias life-threatening or required transfusion)

E Recurrent MI (ECG and CK @) B Other major MI-related eventE Drug-induced hypotension (specify)_

For A, B, C or D, please complete AER form for c Other major non-MI related event

allthromboyticagents. (specify)thrall thrombolylic D LI Allergic/anaphylactic reaction

Discharge Status El Deceased E Alive Date of Discharge or Death LIZ LIf deceased, cause of death: E Cardiogenic shock E Arrhythmias El Other cardiac (specify)

El Sudden cardiac arrest E Recurrent Ml E Rupture!EMD E Non-cardiac (specify)FIG 1. Case report form for National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (primary data collection form). If adverse events A, B, C, or D arecoded, a second form (Adverse Event Record, AER) is used to record date of onset, severity, action taken, and outcome.

minutes for all registry patients. The proportion of thrombolytic agent in the registry (Table 3). Of thepatients receiving thrombolytic therapy became pro- 60 430 rTPA recipients, 48.7% were given the standardgressively smaller as the time from onset of chest pain to regimen of 100 mg over 3 hours, and 40.2% were treatedpresentation lengthened (Fig 5). with an accelerated dosing regimen (generally 100 mg

over 90 minutes).8 The proportion receiving the accel-rTPA-Treated Patients erated rTPA dosing regimen increased each month in

Detailed information was collected on dosing pat- an almost linear fashion, from 8% in October 1990 toterns, time and site of administration, and reasons for 65% i 1993 (Fig 6). Weight-adjusted rTPAnot administering rTPA, the most commonly used dosing was used less frequently (Table 3).

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

2106 Circulation Vol 90, No 4 October 1994

Number of Registry Hospitals per State0 1-10 11-20 21-30 > 30

C] E3 m2 E

FIG 2. Map showing density of registry hospitals per state. Atleast one hospital participates in the National Registry of Myo-cardial Infarction in every state but one (Delaware).

The median time from onset of chest pain to hospitalpresentation for rTPA recipients was 95 minutes (1.6hours). An additional 57 minutes (0.95 hours) (median)elapsed from hospital presentation to rTPA administra-tion ("door-to-drug time"). Trend analyses from 1990 to1993 showed lower median door-to-drug times in 1993than in preceding years (Fig 7). The site of rTPAinitiation was most commonly (69.4%) the emergencydepartment, but 23.2% of rTPA initiation took place inthe coronary care unit. Among transferred patientsreceiving rTPA, the drug was usually (83.8%) begunbefore transport by the referring hospital. Major rea-

sons cited for not administering rTPA were age >75years, >6 hours since chest pain onset, use of otherthrombolytic agent, a perceived contraindication tothrombolysis, and "physician preference." Primary an-

gioplasty was rarely used (3.1%).

Concomitant MedicationsOther frequently used pharmacological therapies re-

corded in the registry were oral aspirin, intravenousheparin, intravenous nitroglycerin, oral :-blockers, andoral calcium channel blockers (Table 4). Of these,aspirin, intravenous heparin, and intravenous nitroglyc-erin were more commonly used in the thrombolyticgroup, and the other pharmacological agents were more

Sites

1,000

800

600

400

200

010 20 30

Months of Registry Enrollment

FIG 3. Graph showing cumulative enrollment of patients andsites in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. FromSeptember 1990 through December 1993, the registry enrolled240 989 patients at 1073 hospitals in the United States.

commonly used in the nonthrombolytic group. Intrave-nous heparin was used in >90% of all patients receivingthrombolytic therapy, whether it was rTPA or anotherthrombolytic agent. Trend analysis showed small butprogressive increases in the use of aspirin and p-block-ers and a fall in the use of calcium channel blockersduring 1990 through 1993 (Fig 8).

Invasive ProceduresCoronary arteriography was performed in 70.7% of

thrombolytic recipients and in 48.3% of the nonthrom-bolytic group (Table 4). Coronary angioplasty andbypass surgery were also used liberally, especially in thethrombolytic group.

Adverse Events In-HospitalAlthough the thrombolytic recipients had more fre-

quent allergic reactions, drug-induced hypotension,peri-infarction arrhythmias, reinfarction, bleeding, andstroke, their mortality (unadjusted for baseline covari-ates) was less than half that of those not receivingthrombolytic therapy (5.9% versus 13.1%, P<.001) (Ta-ble 5). Among the thrombolytic recipients, hospitalmortality was significantly higher for those presenting tothe hospital later after chest pain onset than thosepresenting earlier (Fig 9). The primary causes of deathwere cardiac in the thrombolytic and nonthrombolyticgroups, and median durations of hospitalization weresimilar (Table 5).

DiscussionThe National Registry of Myocardial Infarction is the

largest voluntary database yet assembled of myocardialinfarction patients in the thrombolytic era, and it revealsimportant insight into the current management of thiscommon and potentially fatal illness. The registry doc-uments the relatively low frequency of use of thrombo-lytic therapy in the United States, the long delay topresentation and treatment, a growing trend in the useof an accelerated rTPA dosing regimen, a lower thanexpected use of other proven pharmacological therapy,and a very high use of invasive procedures.

Frequency of Use of Thrombolytic TherapyThrombolytic therapy was used in 35% of registry

patients, greater than the previously reported 20% usefor myocardial infarction in the United States910 butsubstantially lower than the estimated 51% to 62% ofpatients with myocardial infarction potentially eligiblefor thrombolysis1""12 and the .70% of patients actuallytreated with thrombolytics as part of "usual care" in therecent third Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Soprav-vivenza nell' Infarto Miocardico (GISSI-3) and fourthInternational Study of Infarct Survival (ISIS-4) trials.13The fact that registry hospitals were larger and morelikely to have coronary care units and invasive capabil-ities (Table 1) may explain the more aggressive use ofthrombolytic therapy in registry hospitals comparedwith prior estimates for US hospitals.

Nevertheless, even among registry hospitals, there was atendency to target thrombolytic therapy toward relativelyyoung patients presenting within the first few hours afterinfarction (Figs 4 and 5). Meta-analyses14,15 of recentrandomized trials have shown that the absolute mortalityreduction with thrombolytic therapy is greater in elderly

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Rogers et al National Registry of Myocardial Infarction

TABLE 1. Registry Hospitals Compared With Nonregistry US Hospitals

Registry Hospitals* Nonregistry HospitalsNo. of hospitals

No. of licensed beds

<101

101-200

201-300

301-400

>400

Median (25th, 75th percentiles)

JCAHO certification, %

Medical school affiliation, %

Member, Council of Teaching Hospitals, %

Emergency department, %

Coronary care unit, %

Cardiac catheterization laboratory, %

Cardiac surgery, %

1073

9.3

21.8

23.0

20.8

25.1

282 (175, 401)

94.2

27.6

8.0

99.3

72.1

61.3

37.6

6388

51.6

22.5

10.2

5.5

10.1

99 (54, 207)

68.2

12.0

4.7

73.6

22.3

15.6

8.8

JCAHO indicates Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations. Data were obtained from SMGMarketing Group, Inc, Chicago, Ill.

*AII comparisons between registry and nonregistry hospitals were significantly different at P<.001. Data wereavailable for 1070 of the 1073 registry hospitals.

than in younger patients, and it is therefore now recom-mended that thrombolytic therapy not be withheld on thebasis of age alone. When deciding whether to administerthrombolytic therapy to patients presenting relatively lateafter symptom onset, some practitioners may reason thatthe benefit of thrombolytic therapy diminishes rapidlyover time, but its risk remains constant, thus favoringselective treatment of the earlier presenting patients.Although significant mortality reduction with the institu-tion of thrombolytic therapy (rTPA) up to 12 hours afterinfarction has only recently been documented,16,17 it haslong been appreciated that the benefit of lytic therapyextends to at least 6 hours after onset of symptoms.1"'8"19However, only about one third of patients presentingwithin 4 to 6 hours of symptoms are treated (Fig 5). Thus,with regard to age and elapsed time from onset of symp-toms, it would seem that practitioners are not yet conform-ing to recommendations of recent trials when selectingpatients for thrombolytic therapy.

Registry patients with non-Q-wave infarction or non-diagnostic ECGs rarely received thrombolytic therapy,whereas those with well-defined infarct location usuallyreceived thrombolytic therapy (Table 2). Such practiceis consistent with a recent meta-analysis demonstratingno survival advantage at 35 days among patients withoutST elevation or bundle branch block treated withthrombolytic therapy.17 Withholding thrombolytic ther-apy for patients with non-Q-wave infarction or lack ofST elevation is also consistent with recommendations ofthe Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI)phase IIIB trial, which showed no reduction in 6-weekmortality for patients with prolonged chest pain and noST elevation randomized to rTPA plus intravenousheparin versus intravenous heparin alone.20

Time Interval to Presentation and TreatmentThe median time interval from symptom onset until

presentation at the registry hospitals was 2.2 hours (130

minutes), consistent with medians ranging from 2 hoursto 6.4 hours in previous observational studies.21"22 Publiceducation campaigns to reduce patient delay in theUnited States have had minimal or no success.23,24 Theelapsed time from hospital presentation to initiation ofrTPA in the registry (mean, 99 minutes; median, 57minutes) shortened slightly in 1993 (Fig 7) but stillexceeded the hospital delay times for initiating throm-bolytic therapy in the TIMI phase II trial (mean, 81minutes),25 the Pre-hospital Study Group (mean, 84minutes),26 and that reported for hospitals with"streamlined" thrombolytic delivery protocols (mean,30 minutes).25 Of possible relevance is the fact that thecoronary care unit rather than the emergency depart-ment was the site of administration of the lytic agent in23% of registry rTPA recipients, a factor previouslyshown to increase delay in delivery of thrombolytictherapy.25

Because the benefits of reperfusion therapy diminishrapidly with elapsed time before initiation of thera-py27'28 (Fig 9), the National Heart, Lung, and BloodInstitute has recently identified community interven-tions to reduce patient delay as a primary researchtarget. Methods to reduce hospital delay ("door-to-drugtime") by utilization of prehospital 12-lead ECG re-cording and streamlined emergency department proto-cols are also currently under intensive investiga-tion.25'26'29'30 Optimally, thrombolytic therapy should bestarted within 30 minutes of hospital presentation inpatients with typical features of acute myocardial in-farction, according to recently published guidelinesfrom the American Heart Association31 and the 1992National Conference on Cardiopulmonary Resuscita-tion and Emergency Cardiac Care.32

Use of Accelerated rTPA DosingThe registry documents the extraordinary growth in

the use of accelerated or "front-loaded" rTPA dosing

2107

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

2108 Circulation Vol 90, No 4 October 1994

TABLE 2. Baseline Characteristics

Thrombolytic Therapy* No Thrombolytic Therapy

Characteristic N Value N ValueNo. of patients 84 477 156 512

Age, mean, y(median, 25th, 75th percentiles)Weight, mean, kg(median, 25, 75th percentiles)Sex, % men

Male patients

Age, mean, y

Weight, mean, kgFemale patients

Age, mean, y

Weight, mean, kg

Transferred to registry hospital, %

By ambulance

By helicopter

By other means

83 474

79 452

83 688

59 513

56 689

23 227

22 093

23 535

60.6(61.1, 57.7, 69.6)

81.7(80.3, 70.3, 90.7)

71.9

58.9

85.7

64.9

71.4

154 836

143 968

155 053

68.3(69.8, 59.7, 78.2)

77.3(76.2, 64.9, 87.5)

59.7

91 662

85 895

65.7

83.0

61 805

56 881

28 394

65.0

23.9

11.1

72.3

68.6

73.6

14.2

12.2

Time interval, min from chest pain onset to arrival at initialhospital median (25th, 75th percentiles)

All patients

Transferred patients

Nontransferred patients

Infarct locationt

Anterior (V1-V4)Inferior (Il, IlIl, aVF)Lateral (I, aVL)

Posterior (R-V,, Q-V6)Non-Q wave (subendocardial)

Nondiagnostic ECG

73 094

18 448

54 646

84 477

95 (59,180)

90 (50,175)98 (60, 180)

106 252

17 992

88 260

156 512

180 (80, 510)

165 (70, 435)

185 (81, 526)

37.8

54.8

15.9

5.8

2.4

0.8

27.5

30.8

13.1

4.2

26.6

12.6

Other 5.3 8.3

*AII comparisons between thrombolytic therapy and no thrombolytic therapy groups were significantly different at P<.001.'Thrombolytic therapy" includes any thrombolytic agent.

tMultiple responses possible. Infarct location was coded as neither subendocardial, nondiagnostic ECG, nor other in 77 523 of thethrombolytic therapy group and 80 967 of the no thrombolytic therapy group.

over the past 3 years (Fig 6). Accelerated dosing,introduced by Neuhaus et al in 1989,8 was subsequentlyshown to compare favorably with the "standard" 3-hourinfusion of rTPA33 and bolus anistreplase infusion,34 butthe safety and efficacy of accelerated rTPA was not fullyvalidated until the completion of the recent GUSTOtrial.7 Nevertheless, the implementation of acceleratedrTPA dosing among registry hospitals showed strikinggrowth even before release of the GUSTO trial results,probably because of the ease of use of the acceleratedregimen and its documented ability to achieve infarct-related artery patency in more than 80% of patientswithin 90 minutes of initiation.

Pharmacological Therapy Other Than ThrombolyticsRegistry data provide valuable insight into the use of

pharmacological therapy other than thrombolytics foracute myocardial infarction. Aspirin, given to 84% of

registry patients receiving thrombolytic therapy and to63% of the remainder, has been demonstrated to re-duce rates of reinfarction and death after myocardialinfarction whether or not thrombolytic therapy is used.19Although aspirin was used commonly in registry pa-tients, it is surprising that its use was not even higher,given its proven effectiveness, low spectrum of sideeffects, and low cost.

Intravenous heparin, used in 97% of registry patientsreceiving thrombolytics and in more than half theremainder, has never been unequivocally demonstratedto improve longevity in myocardial infarction'135 but hasbeen shown to preserve infarct vessel patency afterrTPA therapy.36-38 The use of protocol-directed intra-venous heparin in combination with rTPA in the recentGUSTO trial7 may explain, in part, the finding of alower 30-day mortality with rTPA than with streptoki-nase-heparin regimens in that trial, whereas prior

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Rogers et al National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2109

% Treated with Thrombolytic Agent in Each Age Stratum70

60 52 53

50

40x

30

20

100

<30 30-39 40-49 50-59 60-69 70-79 80-89 >90

Age (years)

FIG 4. Bar graph showing use of thrombolytic therapy (anyagent) according to age. Top of shaded zone represents thecumulative proportion of patients receiving thrombolytic therapyat each age. After age 50 years, progressively fewer patients aretreated with thrombolytic therapy. The total numbers of patientsin each age stratum are as follows (from left to right): 815, 6261,26 955, 44 671, 63 160, 61 645, 30 501, 4302.

thrombolysis megatrialS39,40 that did not use protocol-directed intravenous heparin showed similar mortalitybetween rTPA and streptokinase therapy. Intravenousheparin may not be required to maintain infarct-relatedvessel patency in patients treated with streptokinase4' oranistreplase,42 agents that, unlike rTPA, cause substan-tial fibrinogen depletion and a measure of "autoantico-agulation." The registry data illustrate that US practi-tioners, even before the results of the above trials wereknown, were routinely administering intravenous hepa-rin with rTPA and other thrombolytic agents.

Intravenous nitroglycerin, used in 76% of thrombo-lytic recipients and 50% of the remainder, was reportedin late 1993 not to improve survival of acute myocardialinfarction.43 However, the widespread use of intrave-nous nitrates in the registry is consistent with an earlier

% Treated with Thrombolytic Agent in Each Time Stratum

70

10

50

0-1 1-2 2-3 3-4 4-5 5-6 6-7 7-8 8-9 9-10 10-11 11-12 '12

Chest Pain Onset to Presentation (hours)

FIG 5. Bar graph showing use of thrombolytic therapy (any

agent) according to duration of chest pain. Progressively fewer

patients are treated with thrombolytic therapy as the interval from

onset of chest pain to hospital presentation lengthens. The total

number of patients in each time stratum are as follows (from left

to right): 43838, 41 508, 23607, 13900, 8801, 6095, 4901,

4069, 3366, 2791, 2280, 2257, 21 933. The graph format is the

same as in Fig 4.

meta-analysis suggesting that intravenous nitroglycerinmight reduce mortality as much as 35%.1 Calciumchannel blockers have not been proven "cardioprotec-tive" after myocardial infarction44,45 and in some studiesappeared to be harmful,4647 yet they were used in 30%of thrombolytic recipients in the registry and in 42% ofall others.Although clinical trials involving more than 26 000

patients' 45 have confirmed the efficacy of f-blockers inlimiting mortality and preventing recurrent ischemiaafter myocardial infarction, intravenous and oralfl-blockers were used in only 17% and 36%, respec-tively, of registry thrombolytic recipients and in 30%and 42%, respectively, of all others. The GUSTOinvestigators, on the other hand, used intravenousfl-blockers in 46% and oral P-blockers in 71% ofpatients with acute myocardial infarction.7 The registry,therefore, reveals patterns of use of pharmacologicaltherapy that, in the case of aspirin, 8f-blockers, andcalcium channel blockers, seem inconsistent with therecommendations of recent clinical trials. However,analysis of trends from 1990 through 1993 suggests thatusage of these agents may slowly be coming closer intoline with trial recommendations (Fig 8), as previouslyreported.5

Invasive ProceduresThe role of postinfarction coronary arteriography

remains controversial.48 The availability of facilities forcardiac catheterization has been shown to correlateclosely with the likelihood of their use after myocardialinfarction.4951' Because the primary incentive for coro-nary arteriography is to identify lesions suitable forrevascularization by angioplasty or bypass surgery, sev-eral recent trials have randomized patients after infarc-tion between an "invasive strategy" of routine coronaryarteriography followed by revascularization, if appropri-ate, and a "conservative strategy" of "watchful wait-ing," with arteriography and revascularization used onlyfor patients with spontaneous or provocable isch-emia.5' 5 None of the trials showed an advantage of theinvasive approach in improving ventricular function,reducing the incidence of reinfarction, or reducingmortality up to 3 years after infarction.54

If the "conservative" approach to postinfarction ar-teriography is followed, what frequencies of coronaryarteriography, angioplasty, and bypass surgery are to beexpected during the initial hospitalization? In the larg-est of the randomized studies, the Should We InterveneFollowing Thrombolysis? (SWIFT)52 trial and the TIMIphase II trial,5' coronary arteriography was used in theconservative groups in 13% and 33%, angioplasty in 3%and 13%, and bypass surgery in 2% and 7%, respec-tively. In the National Registry of Myocardial Infarc-tion, coronary arteriography was used in 71% of throm-bolytic recipients, angioplasty in 30%, and bypasssurgery in 13%. These frequencies are markedly higherthan would have been expected had the conservativepolicy of "watchful waiting" been followed.

Adverse EventsPatients treated with thrombolytic therapy in ran-

domized trials are known to have higher rates of allergicreactions, bleeding, arrhythinias, and reinfarctionn1819and these trends were confirmed in the registry (Table

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

2110 Circulation Vol 90, No 4 October 1994

TABLE 3. Patients Treated With rTPA (Alteplase)

No. of patients treated with rTPA

Dosing regimen, %

Standard

Front-loaded

Weight-adjusted<65 kg

.65 kg

Total dose, mg

Standard

Front-loaded

Weight-adjusted<65 kg.65 kg

Bolus dose, mg

Standard

Front-loaded

Weight-adjusted<65 kg>65 kg

First hour dose, including bolus, mgStandard

Front-loaded

Weight-adjusted

<65 kg>65 kg

Time interval, minutes, mean, median (25th, 75th percentiles)Onset of chest pain to hospital presentationOnset of chest pain to initiation of rTPA

Hospital presentation to initiation of rTPA

Site of rTPA initiation, %

Emergency department

Coronary care unit

Other/unknown

Initiation of rTPA in transferred patients, %

By referring hospital

During transport

By receiving hospital

Other/unknownReasons cited for not administering rTPA, %*

Age >75 years

60 430

48.7

40.2

2.0

6.9

29 053

24 119

99.1

99.0

1163

4116

79.6 (1.4 mg/kg)106.4 (1.2 mg/kg)

28 689

23 983

10.4

15.5

1162

4108

10.9

12.2

28 577

23 559

60.3

74.5

1122

4010

56.2

75.4

52 323

51 092

52 186

60 430

171, 95 (58, 180)

251, 165 (108, 268)99, 57 (35, 96)

69.4

23.2

7.4

15 455

83.8

0.8

8.4

7.1

180 559

19.7>6 hours since chest pain onset 29.7Other thrombolytic used 13.3

Primary angioplasty undertaken 3.1

Patient refusal 1.1Contraindication to thrombolysis 24.2Physician preference 32.5

rTPA indicates recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator.*Multiple responses possible. "Physician preference" was entered if no other reasons applied.

N Value

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Rogers et al National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2111

Percent of rTPA Given by Accelerated Dosing During Prior Month

2 10 20 30 40Months of Registry Enrollment

FIG 6. Graph showing interval use of accelerated recombinanttissue-type plasminogen activator (rTPA) dosing. The proportionof rTPA recipients receiving the accelerated dose regimen (100mg over 90 minutes) increased progressively over the durationof the registry.

5). Hospital mortality was substantially lower (5.9%)among patients treated with thrombolytics than thosenot treated (13.1%). Although thrombolytic therapywas probably life-saving in many instances, it is likelythat selection of lower-risk patients for thrombolysis wasthe primary factor explaining the lower mortality rate.

Limitations of the RegistryMultiple limitations of the National Registry of Myo-

cardial Infarction should be acknowledged. Althoughthe registry is composed of hospitals throughout theUnited States, registry hospitals are not necessarilyrepresentative of all US hospitals, as shown in Table 1,but probably reflect practice in larger, more procedure-oriented centers. Registry hospitals may have beenmore prone to use thrombolytic therapy, and specificallyrTPA, than nonregistry hospitals. The registry, al-though very large, is a simple observational databaserather than a randomized trial, and thus it is morevaluable for documenting practice patterns and tempo-ral trends than comparing outcomes of patient subsets.Like many of the recent megatrials in thrombolysis, dataobtained on each registry patient were rather limited,there was no independent validation of data forms, and

Time to Presentation and Initiating rTPA (Hours)

3

2.5

2

1.5

U.Ulul-Dec 90 Jan-Jun 91 Jul-Dec 91 Jan-Jun 92 Ju-Dec 92 Jan-Jun 93 Jul-Dec 93

Months of Registry Enrollment

FIG 7. Graph showing temporal trends for time to presentationand initiation of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator(rTPA). Time intervals were remarkably consistent from 1990 to1992. The interval from hospital evaluation until initiation of rTPAtherapy was slightly shorter in 1993.

TABLE 4. Concomitant Medications andInvasive Procedures

NoThrombolytic ThrombolyticTherapy* Therapy

Characteristic N Value N Value84 477 156 512

Aspirin, % 84.0 62.8

IV heparin, %

All patients 96.9 56.0

With rTPA 98.4

With other thrombolytics 93.2

With rTPA plus otherthrombolytics 97.8

IV nitroglycerin, % 76.0 50.1

IV P-blocker, % 17.4 5.5

Oral 3-blocker, % 36.3 29.5

Calcium channel blocker, % 29.5 41.9

Inotropic agent, % 14.2 18.5

Coronary arteriography, % 70.7 48.3

PTCA, % 30.3 16.3

CABG, % 13.3 10.9

IV indicates intravenous; rTPA, recombinant tissue-type plas-minogen activator; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronaryangioplasty; and CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

*AII comparisons between thrombolytic therapy and no throm-bolytic therapy groups were significantly different at P<.001."Thrombolytic therapy" includes any thrombolytic agent.

there was the potential for nonconsecutive patientenrollment and "underreporting" of adverse events.The limited baseline data collection in this simple

registry renders interpretation of some of the findingsless certain than others. Whereas observations on ex-cessive delay to initiate thrombolytic therapy and over-use of calcium channel blockers seem indisputable, therelatively low usage of aspirin and 8-blockers might besecondary to contraindications to these agents not

% of Registry Patients Receiving Pharmacotherapy

80 77Aspirin62~

60

44 Calcium Channel Blockers

40 *3***6*- --_27

3120 Oral Beta Blockers IV Beta Blockers

8~~~~~~~~~~8 f f f *l P 12

5-Dec90 Jan-Jun 91 JulDec 91 Jan-Jun 92 Ju-Dec 92 Jan-Jun 93 Jul-Dec 93Months of Registry Enrollment

FIG 8. Graph showing temporal trends for usage of pharmaco-therapy other than thrombolytics. Among all registry patients,small but progressive increases in the use of aspirin andp-blockers were noted from 1990 to 1993 as well as a fall in theusage of calcium channel blockers. IV indicates intravenous.

Pain Onset until Initiating rTPA_>; ~ ~ ~~.8_28 2.7 28 2.8 2.8 2.7 2.

- Pain Onset until Hospital Presentation

1.5 1.5 168 1.6 1.6 1.6 1.1.5 1.5 ± _ 7

1.0 .0 1.0 1.0 1.0 00 0.8

Hospital Presentation until Initiating rTPA

.jn c

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

2112 Circulation Vol 90, No 4 October 1994

TABLE 5. Adverse Events In-Hospital

Thrombolytic Therapy* No Thrombolytic Therapy

Characteristic N Value N ValueN 84 477 156 512

Allergic or anaphylactic reaction, % 0.4 0.0Drug-induced hypotension, % 6.4 1.1Peri-infarction arrhythmias, % 26.0 13.0

Reinfarction (ECG and CK positive), % 3.1 1.4Minor surface bleeding, % 9.1 0.9Major bleeding (intracranial, life-threatening,or required transfusion), % 2.8 0.5Death, % 5.9 13.1Total stroke, %t 0.9 0.3

Intracranial bleed 0.6 0.04

Cause(s) of death, %tCardiogenic shock 2.3 4.2

Arrhythmias 0.9 1.9

Sudden cardiac arrest 1.5 3.8

Reinfarction 0.4 0.9

Rupture/EMD 0.7 0.9

Other cardiac 0.5 1.5

Noncardiac 0.8 2.1

Duration of hospitalization, days, median(25th, 75th percentiles) 82 290 7.5 (5.2, 10.4) 153 036 7.5 (5.1, 11.2)CK indicates creatine kinase; EMD, electromechanical dissociation.*AII comparisons between thrombolytic therapy and no thrombolytic therapy groups were significantly different at

the P<.001 level. 'Thrombolytic therapy" includes any thrombolytic agent.tRegistry hospitals were asked to complete the Adverse Event Record only for patients receiving thrombolytic

agents; therefore, total stroke and intracranial bleeding frequencies for the no thrombolytic therapy group may beunderrepresentative. Intracranial bleeds included any of the following, diagnosed according to the registryhospital's local criteria: cerebral hemorrhage, intracranial hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and subduralhematoma.

*Multiple responses possible.

% Mortality (Thrombolytic Recipients)10

8

6

4

2

00-1 1-2 2-3 3-4 4-5 5-6 6-7 7-8 8-9 9-10 10-11 11-12 >12

Chest Pain Onset to Presentation (hours)FIG 9. Bar graph showing hospital mortality as a function ofduration of chest pain before hospital presentation amongthrombolytic recipients. In general, hospital mortality increasedas the interval from onset of chest pain to delivery of thrombolytictherapy lengthened. The cumulative mortality distributions risesonly slightly, however, because most patients are clustered inthe 0- to 4-hour time frame. The graph format and numbers ofpatients in each time stratum are the same as in Fig 5.

recorded on the simple data form, as might be therelatively low use of thrombolysis in the elderly and latepresenters. Despite these limitations, the registry datacompare favorably with practice trends and outcomespreviously reported in smaller surveys and clinicaltrials.3,4

Clinical Implications and Future DirectionsThe National Registry of Myocardial Infarction sug-

gests that, among the participating institutions, compos-ing about 14% of all US hospitals, the results of recentclinical trials are being implemented in clinical practicein an inconsistent fashion. Although thrombolytic ther-apy is used in a substantial proportion of infarct pa-tients, it is often withheld from elderly patients, inwhom it may save the most lives, and from patients whodo not reach the hospital immediately after symptomonset. For patients treated with thrombolytic therapy,the "door-to-drug time" is extraordinarily prolonged.Although adjunctive treatment with intravenous hepa-rin and intravenous nitroglycerin is usually used, aspirinand }3-blockers appear to be underused and calciumchannel blockers appear to be overused. Furthermore,it is evident that routine coronary arteriography after

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

Rogers et al National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2113

infarction followed by revascularization, if feasible, isthe policy at many institutions, despite the findings ofrecent clinical trials showing that such invasive manage-ment offers no better short- or long-term outcome thana more conservative approach.These observations should provide incentive for al-

terations in current practice patterns: expansion of theuse of thrombolytic therapy, more rapid triage andtreatment, more appropriate conjunctive pharmaco-therapy, and a more rational utilization of invasiveresources. As these or other changes begin to occur, theNational Registry of Myocardial Infarction will be avaluable tool to detect and track such modifications andtheir outcome.

References1. Yusuf S, Sleight P, Held P, McMahon S. Routine medical man-

agement of acute myocardial infarction: lessons from overviews ofrecent randomized controlled trials. Circulation. 1990;82(suppl II):11-117-11-134.

2. ACC/AHA Task Force. Guidelines for the early management ofpatients with acute myocardial infarction: a report of the AmericanCollege of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force onAssessment of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Cardiovascular Pro-cedures (Subcommittee to Develop Guidelines for the Early Man-agement of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction). JAm CollCardioL 1990;16:249-292.

3. Hlatky MA, Cotugno HE, Mark DB, O'Connor C, Califf RM,Pryor DB. Trends in physician management of uncomplicatedacute myocardial infarction, 1970 to 1987. Am J Cardiol. 1988;61:515-518.

4. Rouleau JL, Moye LA, Pfeffer MA, Arnold JM, Bernstein V,Cuddy TE, Dagenais GR, Geltman EM, Goldman S, Gordon D,Hamm P, Klein M, Lamas GA, McCans J, McEwan P, MenapaceFJ, Parker JO, Sestier F, Sussex B, Braunwald E, for the SAVEInvestigators. A comparison of management patterns after acutemyocardial infarction in Canada and the United States: the SAVEinvestigators. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:779-784.

5. Lamas GA, Pfeffer MA, Hamm P, Wertheimer J, Rouleau JL,Braunwald E, for the SAVE Investigators. Do the results of ran-domized clinical trials of cardiovascular drugs influence medicalpractice? N Engl J Med. 1993;327:241-247.

6. Ketley D, Woods KL. Impact of clinical trials on clinical practice:example of thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. Lancet.1993;342:891- 894.

7. The GUSTO Investigators. An international randomized trialcomparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardialinfarction. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:673-682.

8. Neuhaus KL, Feuerer W, Jeep-Tebbe S, Niederer W, Vogt A,Tebbe U. Improved thrombolysis with a modified dose regimen ofrecombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator. JAm Coll Cardiol.1989;14:1566-1569.

9. Cragg DR, Friedman HZ, Bonema JD, Jaiyesimi IA, Ramos RG,Timmis GC, O'Neill WW, Schreiber TL. Outcome of patients withacute myocardial infarction who are ineligible for thrombolytictherapy. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:173-177.

10. Muller DWM, Topol EJ. Selection of patients with acute myo-cardial infarction for thrombolytic therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:949-960.

11. Jagger JD, Murray RG, Davies MK, Littler WA, Flint EJ. Eligi-bility for thrombolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction.Lancet. 1987;1:34-35.

12. Doorey AJ, Michelson EL, Topol EJ. Thrombolytic therapy ofacute myocardial infarction: keeping the unfulfilled promises.JAMA. 1992;268:3108-3114.

13. Ferguson JJ III. Meeting highlights. Circulation. 1994;89:545-547.14. Grines CL, DeMaria AN. Optimal utilization of thrombolytic

therapy for acute myocardial infarction: concepts and contro-versies. JAm Coll Cardiol. 1990;16:223-231.

15. Collins R, for the ISIS Collaborative Group. Optimizing throm-bolytic therapy of acute myocardial infarction: age is not a con-traindication. Circulation. 1991;84(suppl II):II-230. Abstract.

16. LATE Study Group. Late assessment of thrombolytic efficacy(LATE) study with alteplase 6-24 hours after onset of acute myo-cardial infarction. Lancet. 1993;342:759-766.

17. Fibrinolytic Therapy Trialists' (FTT) Collaborative Group. Indi-cations for fibrinolytic therapy in suspected acute myocardialinfarction: collaborative overview of early mortality and majormorbidity results from all randomised trials of more than 1000patients. Lancet. 1994;343:311-322.

18. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell'InfartoMiocardico (GISSI). Effectiveness of intravenous thrombolytictreatment in acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1986;1:397-402.

19. ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collabo-rative Group. Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oralaspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acutemyocardial infarction: ISIS-2. Lancet. 1988;2:349-360.

20. The TIMI IIIB Investigators. Effects of tissue plasminogenactivator and a comparison of early invasive and conservativestrategies in unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardialinfarction: results of the TIMI IIIB trial. Circulation. 1994;89:1545-1556.

21. Turi ZG, Stone PH, Muller JE, Parker C, Rude RE, Raabe DE,Jaffe AS, Hartwell TD, Robertson TL, Braunwald E. Implicationsfor acute intervention related to time of hospital arrival in acutemyocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1986;58:203-209.

22. Cooper RS, Simmons B, Castaner A, Prasad R, Franklin C, FerlinzJ. Survival rates and pre-hospital delay during myocardialinfarction among black persons. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:208-211.

23. Ho MT, Eisenberg MS, Litwin PE, Schaeffer SM, Damon SK.Delay between onset of chest pain and seeking medical care: theeffect of public education. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:727-731.

24. Moses HW, Engelking N, Taylor GJ, Prabhakar C, Vallala M,Colliver JA, Silberman H, Schneider JA. Effect of a two-yearpublic education campaign on reducing response time of patientswith symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:249-251.

25. Sharkey SW, Brunette DD, Ruiz E, Hession WT, Wysham DG,Goldenberg IF, Hodges M. An analysis of time delays precedingthrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1989;262:3171-3174.

26. Kereiakes DJ, Weaver WD, Anderson JL, Feldman T, Gibler B,Aufderheide T, Williams DO, Martin LH, Anderson LC, MartinJS, McKendall G, Sherrid M, Greenberg H, Teichman SL. Timedelays in the diagnosis and treatment of acute myocardialinfarction: a tale of eight cities: report from the Pre-hospital StudyGroup and the Cincinnati Heart Project. Am Heart J. 1990;120:773-780.

27. Tiefenbrunn AJ, Sobel BE. Timing of coronary recanalization:paradigms, paradoxes, and pertinence. Circulation. 1992;85:2311-2315.

28. Weaver WD, Cerqueira M, Hallstrom AP, Litwin PE, Martin JS,Kudenchuk PJ, Eisenberg M, for the Myocardial Infarction Triageand Intervention Project Group. Prehospital-initiated vs hospital-initiated thrombolytic therapy: the Myocardial Infarction Triageand Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1993;270:1211-1216.

29. Valenzuela TD, Hampton DR, Keep MH, Clark LL, Finkel E,Spaite DW, Smith R. Effect of paramedic-acquired 12-lead elec-trocardiograms (ECGs) on time to thrombolysis in acute myo-cardial infarction (AMI). Circulation. 1993;88(suppl I):I-17.Abstract.

30. Martin JS, Kudenchuk PJ, Litwin PE, for the MITI Project Inves-tigators. Do pre-hospital electrocardiograms affect treatmentincidence, time to treatment and hospital admission rates for acutemyocardial infarction? Circulation. 1993;88(suppl I):I-17. Abstract.

31. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee and Subcommittees, AmericanHeart Association. Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation andemergency cardiac care, III: adult advanced cardiac life support.JAMA. 1992;268:2199-2241.

32. Eisenberg MS, Aghababian RV, Bossaert L, Jaffe AS, Ornato JP,Weaver WD. Thrombolytic therapy. In: Proceedings of the 1992National Conference on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation andEmergency Cardiac Care. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:417-427.

33. Carney RJ, Murphy GA, Brandt TR, Daley PJ, Pickering E, WhiteHJ, McDonough TJ, Vermilya SK, Teichman SL. Randomizedangiographic trial of recombinant tissue-type plasminogenactivator (alteplase) in myocardial infarction: RAAMI Study inves-tigators. JAm Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:17-23.

34. Neuhaus KL, Von Essen R, Tebbe U, Vogt A, Roth M, Riess M,Niederer W, Forycki F, Wirtzfeld A, Maeurer W, Limbourg P,Merx W, Haerten K. Improved thrombolysis in acute myocardialinfarction with front-loaded administration of alteplase: results ofthe rt-PA-APSAC Patency Study (TAPS). JAm Coll CardioL 1992;19:885-891.

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

2114 Circulation Vol 90, No 4 October 1994

35. Ridker PM, Hebert PR, Fuster V, Hennekens CH. Are bothaspirin and heparin justified as adjuncts to thrombolytic therapyfor acute myocardial infarction? Lancet. 1993;341:1574-1577.

36. Hsia J, Hamilton WP, Kleiman N, Roberts R, Chaitman BR, RossAM, for the Heparin-Aspirin Reperfusion Trial (HART) Investi-gators. A comparison between heparin and low-dose aspirin asadjunctive therapy with tissue plasminogen activator for acutemyocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1433-1437.

37. Bleich SD, Nichols TC, Schumacher RR, Cooke DH, Tate DA,Teichman SL. Effect of heparin on coronary arterial patency afterthrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator in acute myocardialinfarction. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:1412-1417.

38. de Bono DP, Simoons ML, Tijssen J, Arnold AE, Betriu A, Burg-ersdijk C, Lopez-Bescos L, Mueller E, Pfisterer M, Van de Werf F,Zijlstra F, Verstraete M, for the European Cooperative StudyGroup. Effect of early intravenous heparin on coronary patency,infarct size, and bleeding complications after alteplase throm-bolysis: results of a randomized double blind European Coop-erative Study Group trial. Br Heart J. 1992;67:122-128.

39. The International Study Group. In-hospital mortality and clinicalcourse of 20,891 patients with suspected acute myocardialinfarction randomised between alteplase and streptokinase with orwithout heparin. Lancet. 1990;336:71-75.

40. ISIS-3 (Third International Study of Infarct Survival) Collabo-rative Group. ISIS-3: a randomized comparison of streptokinase vstissue plasminogen activator vs anistreplase and of aspirin plusheparin vs aspirin alone among 41,299 case of suspected acutemyocardial infarction. Lancet. 1992;339:753-770.

41. Col J, Decoster 0, Hanique G, Deligne B, Boland J, Pirenne B,Cheron P, Renkin J. Infusion of heparin conjunct to streptokinaseaccelerates reperfusion of acute myocardial infarction: results of adouble-blind randomized study (OSIRIS). Circulation. 1992;86(suppl II):II-259. Abstract.

42. O'Connor CM, Meese R, Carney R, Smith J, Conn E, Burks J,Hartman C, Roark S, Shadoff N, Heard M III, Mittler B, Collins G,Navetta F, Leimberger J, Lee K, Califf RM, for the DUCCSGroup. A randomized trial of intravenous heparin in conjunctionwith anistreplase (anisoylated plasminogen streptokinase activatorcomplex) in acute myocardial infarction: the Duke UniversityClinical Cardiology Study (DUCCS) 1. JAm Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:11-18.

43. Tognoni G. Lisinopril and nitrates after acute myocardialinfarction: introduction and results: GISSI-3. Presented at the 66thAnnual Scientific Sessions of the American Heart Association;November 8, 1993; Atlanta, Ga.

44. Held P, Yusuf S, Furberg C. Effects of calcium antagonists oninitial infarction, reinfarction and mortality in acute myocardialinfarction and unstable angina. Br Med J. 1989;299:1187-1192.

45. Teo KK, Yusuf S, Furberg CD. Effects of prophylactic antiar-rhythmic drug therapy in acute myocardial infarction: an overviewof results from randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1993;270:1589-1595.

46. The Multicenter Diltiazem Post Infarction Trial Research Group.The effect of diltiazem on mortality and reinfarction after myo-cardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:385-392.

47. The Israeli SPRINT Study Group. Secondary Prevention Rein-farction Israeli Nifedipine Trial (SPRINT): a randomized inter-vention trial of nifedipine in patients with acute myocardialinfarction. Eur Heart J. 1988;9:354-364.

48. Topol EJ, Holmes DR, Rogers WJ. Coronary angiography afterthrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Ann InternMed. 1991;114:877-885.

49. Blustein J. High-technology cardiac procedures: the impact ofservice availability on service use in New York State. JAMA.1993;270:344-349.

50. Every NR, Larson EB, Litwin PE, Maynard C, Fihn SD, EisenbergMS, Hallstrom AP, Martin JS, Weaver WD, for the MyocardialInfarction Triage and Intervention Project Investigators. The asso-ciation between on-site cardiac catheterization facilities and theuse of coronary angiography after acute myocardial infarction.N Engl J Med. 1993;329:546-551.

51. The TIMI Study Group. Comparison of invasive and conservativestrategies after treatment with intravenous tissue plasminogenactivator in acute myocardial infarction: results of the Throm-bolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Phase II trial. N Engl JMed. 1989;320:618-627.

52. SWIFT (Should We Intervene Following Thrombolysis?) TrialStudy Group. SWIFT trial of delayed elective intervention vs con-servative treatment after thrombolysis with anistreplase in acutemyocardial infarction. Br Med J. 1991;302:555-560.

53. Barbash GI, Roth A, Hod H, Modan M, Miller HI, Rath S, HarZahav Y, Keren G, Motro M, Shachar A, Basan S, Agranat 0,Rabinowitz B, Laniado S, Kaplinsky E. Randomized controlledtrial of late in-hospital angiography and angioplasty versus conser-vative management after treatment with recombinant tissue-typeplasminogen activator in acute myocardial infarction.Am J Cardiol.1991;66:538-545.

54. Terrin ML, Williams DO, Kleiman NS, Willerson J, Mueller HS,Desvigne-Nickens P, Forman SA, Knatterud GL, Braunwald E, forthe TIMI Investigators. Two- and three-year results of the Throm-bolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Phase II Clinical Trial.JAm Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:1763-1772.

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from

J Tiefenbrunn and W D WeaverW J Rogers, L J Bowlby, N C Chandra, W J French, J M Gore, C T Lambrew, R M Rubison, A

the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction.Treatment of myocardial infarction in the United States (1990 to 1993). Observations from

Print ISSN: 0009-7322. Online ISSN: 1524-4539 Copyright © 1994 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved.

is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231Circulation doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.4.2103

1994;90:2103-2114Circulation.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/90/4/2103World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the

http://circ.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/

is online at: Circulation Information about subscribing to Subscriptions:

http://www.lww.com/reprints Information about reprints can be found online at: Reprints:

document. Permissions and Rights Question and Answer this process is available in the

click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information aboutOffice. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located,

can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the EditorialCirculationin Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally publishedPermissions:

by guest on October 5, 2017

http://circ.ahajournals.org/D

ownloaded from