Transit, More than a Ride – Trusted Advocate Pilot Project Evaluation

Transcript of Transit, More than a Ride – Trusted Advocate Pilot Project Evaluation

Transit, More than a Ride

Trusted Advocate Pilot Project Evaluation

Perspectives on the 2012 Trusted Advocate Engagement Model

as applied to the Central Corridor Transit Service Study Project

For the District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and Minneapolis

Acknowledgements

District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and Minneapolis

Karyssa Jackson Communications and Outreach Coordinator Trusted Advocate Project Manager

Suado Abdi Trusted Advocate

Hadi Abdidubul Trusted Advocate

Mee Cheng Trusted Advocate

Sulekha Diriye Trusted Advocate

Anne Gomez Trusted Advocate

Henry Keshi Trusted Advocate

Sheronda Orridge Trusted Advocate

Tim Page Trusted Advocate

Kjensmo Walker Trusted Advocate

Carol Swenson Executive Director

Metro TransitJohn Levin Director of Service Development

Cyndi Harper Manager, Route Planning

Scott Thompson Senior Transit Planner

Jill Hentges Community Outreach Coordinator

With a special thank you to the Central Corridor Funders Collaborative for its generous support of the Transit, More than a Ride Trusted Advocate Pilot Project.

The District Councils Collaborative wishes to acknowledge The Saint Paul Foundation, The F.R. Bigelow Foundation and The McKnight Foundation for their generous support of our programs.

April 2013

Project evaluation and report prepared by Susan Hoyt, Susan Hoyt Consulting.

Table of ContentsSUMMARY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 Creating a project partnership . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 Findings around the project’s goals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 Community Conversation about the Trusted Advocate Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 Issues to Consider. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 Background . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 Study Area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 The Project . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 Evaluation Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

FINDINGS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 Achieving Project Goals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 Goal 1: Increase participation of underrepresented communities in the CCTS Study . . . . . . . . . . 8 Goal 2: Promote learning by building capacity of underrepresented persons including learning from available communication tools and information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11 Goal 3: Generate a transit service plan that serves the needs of those who live on the corridor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12 Goal 4: Strengthen the relationship between Metro Transit and underrepresented community members to create a shared solution that will influence changes in the system for future planning. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 Goal 5: Bring a new model of engagement to the Twin Cities region . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

CONVERSATION WITH COMMUNITY LEADERS ABOUT THE MODEL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

ITEMS TO CONSIDER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

APPENDIX I Resources. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

APPENDIX 2 Agenda for the Community Leaders Conversation about the Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Figure 1: Central Corridor Transit Service Study Area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 Figure 2: Minority Population in CCTSS Area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Figure 3: Population in Poverty in CCTSS Area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 Figure 4: Diagram of how Trusted Advocate model and Metro Transit public involvement support the planning process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 Figure 5: Trusted Advocate Outreach by Community Engaged . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9 Figure 6: Trusted Advocate Approaches to Engagement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 Figure 7: Metro Transit Public Involvement by Type of Response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 Figure 8: Summary of Evaluation Responses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

income persons. Metro Transit staff, who seek innovative engagement tools to better understand the transit needs of the community served, agreed to join in the pilot project. From the outset, the two organizations agreed that: the DCC would contract and manage the Trusted Advocates based upon their community relationships, residency and familiarity with transit and that Metro Transit would provide training and be available to answer questions for the Trusted Advocates. The Trusted Advocates sought

out community connections to share information and get input from community members to provide to Metro Transit planning staff. Meanwhile, Metro Transit implemented its traditional outreach and engagement process. Although the two

processes were distinctly different they intersected with each throughout the project. Each approach provided useful input into the CCTSS final plan. The Trusted Advocates’ connections substantially increased the input from underrepresented communities.

Findings around the project's goals

At the outset of the project, the DCC and Metro Transit both valued community engagement (DCC) and public involvement (Metro Transit), as stated in each organization's guiding principles. In addition, all participants shared a common understanding that the purpose of the pilot project was to try a new model of engagement to hear the voices of underrepresented communities in the public decision-making process. This was fundamental to the project's overall success in achieving its five goals. The project significantly increased the engagement of underrepresented community members within the study area. This was the most measurable data for the project. Trusted Advocates confirmed contacts with 1,200 residents and business owners in the study area and collected 700 origin-destination data points from them. A minimum of 85 percent of the connections made by the Trusted Advocates was within the target communities. These connections

SUMMARY

This report evaluates the success of the Transit, More than a Ride Trusted Advocate Pilot Project in meeting the project's goals. It also identifies issues to consider when applying the model to future projects in the Twin Cities Region.

The Transit, More than a Ride Trusted Advocate Pilot Project was initiated by the District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and Minneapolis (DCC) from January through August 2012 as a way to engage underrepresented persons (African American, new immigrant (aka New American), disability and low-income communities) as well as students attending one of the area schools in Metro Transit's Central Corridor Transit Service Study (CCTSS). The CCTSS's purpose was to analyze the twenty-three bus routes in the Central Corridor area to determine how to maximize the overall effectiveness and efficiency of transit service in conjunction with the 2014 opening of the METRO Green Line light rail service. In other words, to make sure that the bus service and the LRT meet the transit needs of the communities served. The Trusted Advocate pilot project, which was funded for $75,000 by the Central Corridor Funders Collaborative (CCFC), was the first known application of the Trusted Advocate model outside of the health community in the Twin Cities region. Ultimately, nine community members with high transit literacy, transit ridership experience and strong connections to underrepresented communities in the study area were contracted as Trusted Advocates for the project. This qualitative approach to evaluating the project included a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended conversations, a survey of Metro Transit staff and the reflections of Trusted Advocates.

Creating a project partnership

The DCC invited Metro Transit to join in the Trusted Advocate model of engagement for getting input into the CCTSS because of the large transit dependent population in the study area many of whom are persons of color, new immigrants, disability community members and/or low-

1

The Trusted Advocates, residents of Ravoux and Metro Transit staff created a shared solution to solve the problem

with significant limited mobility and connected them with Metro Transit staff. The result of learning how this community of people use their transit service was more direct bus service rather than the assumption that these residents could transition to a longer walk to rail service. The Trusted Advocates, residents of Ravoux and Metro Transit staff created a shared solution to solve the problem.

The project began to build relationships between the DCC, Trusted Advocates and Metro Transit staff that increased the level of trust that the DCC and Trusted Advocates held for the Metro Transit staff (people) involved in the project. It did not increase the overall trust of DCC and Trusted Advocates for Metro Transit as a government organization. However, over time greater trust in the people in the organization may result in increased trust for the organization. Due to a short timeline to incorporate the Trusted Advocate project into the CCTSS process, the project participants experienced communication and operational issues that could have led to distrust or disrespect along the way. However, the participants viewed these as hurdles rather than major barriers to getting the work done.

The project successfully brought a new model of engagement to the Twin Cities region, which was familiar to local community engagement leaders, but had not been implemented. With the pilot on the CCTSS completed, the DCC is now using the Trusted Advocate model to manage community engagement in the Corridors to Careers project, a partnership with Ramsey County. This pilot project focuses on connecting residents and employers to workforce and training resources.

Community Conversation about the Trusted Advocate Model

With a growing interest in the application of the Trusted Advocate model in the Twin Cities region, the DCC invited a group of community leaders to participate in a conversation about the future of the model. The discussion

were in addition to the Metro Transit's public involvement that included extensive outreach prior to the development of the concept plan and official public process following release of the concept plan and the adoption of the recommended plan.

The project built the capacity of the Trusted Advocates around the public transit decision-making process through their direct association, telephone and email access to Metro Transit staff project planners along with their attendance at Metro Transit led public meetings. They also gained more in-depth information about the CCTSS. In their turn, Trusted Advocates increased the capacity of community members around the existence, operations and proposed transit changes planned for the community as well as about how the transit decisions get made. The project did expose more underrepresented community members to the overall public process, but did not necessarily drive large numbers of these community members to public meetings. Although there was a desire and expectation for this result, it may illustrate that the format, timing and location of public meetings may need to be re-thought to make them more accessible to all constituencies. It is also true that some people will never attend public meetings of this type regardless of time and location. It is important to recognize that engagement of underrepresented populations must include non-traditional engagement similar to the strategies implemented by the Trusted Advocates. In some communities, success comes from deep engagement rather than broad engagement.

The project was perceived to have generated a transit service plan that better serves the needs of all those who live on the corridor with particular attention to underrepresented communities. Evaluation respondents expressed confidence that the increased engagement of underrepresented communities through the Trusted Advocates achieved this result. When restating this question in the form of "did the project directly influence the recommendations in the CCTSS," the answer was "yes." One specific example consistently emerged to demonstrate this conclusion, Ravoux Hi-Rise. The Trusted Advocates raised the awareness of low-income residents

2

covered a wide range of topics with a focus on how to build trust between government and community organizations, what is fundamental to the model to make it work, what project criteria make it potentially successful, who is positioned to manage the Trusted Advocates project and how is system change created through this work.

Issues to Consider

In addition to the evaluation of the pilot project, this report includes a discussion of issues to consider around the Trusted Advocate model. Fundamental questions that emerged include: what criteria make a project a good candidate for the trusted advocate model; what is the role of the Trusted Advocate; and what entity is best positioned to manage the Trusted Advocate's work. This report does not address specific operational issues because they did not emerge as issues in the evaluation. Two resources that address operational requirements of the Trusted Advocate model include work done by the Annie E. Casey Foundation (2007) and Forterra (2013).

INTRODUCTIONBackground

Strategies and tools to engage underrepresented communities have become an important part of the community and transit planning dialogue in the recent past. In the past two years, the Twin Cities region has gained national recognition for directly funding community-based organizations to engage their communities through the Twin Cities Corridors of Opportunity initiative – HUD Sustainable Communities Grant. Also visible at the national level is the Trusted Advocate

model. Initially used by community health workers, it was adapted to neighborhood land use planning in Seattle, Washington and community work in Oakland, California.

The opportunity to use the Trusted Advocate model in the Twin Cities emerged with the Metro Transit’s CCTSS planning, which Metro Transit planners were beginning in 2011 for completion in 2012. The purpose of the CCTSS was to review and recommend changes in bus routes

to maximize the transit service and improve efficiency in conjunction with the opening of the METRO Green Line (LRT) in 2014. The District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, a place-based community organization, believed this model held promise for the Metro Transit Central Corridor Transit Service Study (CCTSS) because: 1) the area impacted by the study was demographically diverse and low income, 2) the population was highly transit dependent, 3) the community networks were established, 4) the opportunity to build positive ongoing relationships with Metro Transit through a collaborative engagement model existed, 5) the Metro Transit staff was potentially receptive to a new engagement model in this study area and 6) the opportunity existed to really influence the CCTSS’s recommendations that would be

3

In the past two years, the Twin Cities region has gained national recognition for directly funding community-based organizations to engage their communities.

implemented within less than two years. In addition, funding was available for the Transit, More than a Ride Trusted Advocate Pilot Project from the Central Corridors Funders Collaborative. Metro Transit, in turn, was seeking new opportunities to engage underrepresented persons in the CCTSS.

Study Area

The study area for the CCTS is bounded by the Mississippi River on the south, I-35E on the east, Larpenteur/East Hennepin Avenues on the north and by Hiawatha Avenue, East Lake Street and the Mississippi River on the west (Figure 1). The study area is almost completely urban, including downtown Minneapolis, downtown Saint Paul and the University of Minnesota, and covering many neighborhoods of St. Paul, Minneapolis and the suburbs of Lauderdale, Falcon Heights and Roseville. The population of the Study Area is about 246,170, with minorities making up 35 percent. In the neighborhoods immediately adjacent to the METRO Green Line, the population is about 163,790, with minorities comprising 45 percent (Figure 2). There are concentrations of low-income persons throughout the study area (Figure 3). As of 2008, there were about 357,587 jobs in the Study Area, of which, 348,558 jobs were located in the neighborhoods adjacent to the METRO Green Line or about 22 percent of the employment in the entire metropolitan area. The routes included in the study include all those which operate a significant portion of their total service in the study area and which provide a connection to the Green Line. This includes routes 2, 3, 6, 8, 16, 21, 50, 53, 62, 63, 65, 67, 84, 87, 94, 134, and 144.

Figure 1: Central Corridor Transit Service Study Area

Source: Metro Transit CCTSS Existing Conditions Report

4

Figure 3: Population in Poverty in CCTSS Area

Source: Metro Transit CCTSS Existing Conditions Report

Figure 2: Minority Population in CCTSS Area

Source: Metro Transit CCTSS Existing Conditions Report

5

The Project

The DCC implemented the Transit, More than a Ride Trusted Advocate Pilot Project in collaboration with Metro Transit from January through August 2012. It contracted with nine Trusted Advocates, who were individuals from diverse communities and neighborhoods within the CCTSS area, to do intensive engagement to connect with people who do not normally participate in the formal Metro Transit planning processes. This information would then be shared with Metro Transit staff on the CCTSS project. This complemented the Metro Transit public process; it did not replace it. The Metro Transit public involvement plan and related information about the CCTSS identified the Trusted Advocates as part of the public involvement process. The fundamental difference between the Trusted Advocate approach and the more traditional public process as enhanced by Metro Transit is in how they get input from the community. Both approaches are appropriate ways to connect community members to the project but the more traditional approach reaches members typically engaged in public process, while the Trusted Advocates are able to reach members typically missed in public process. As Metro Transit hosted public meetings or attended existing community meetings, the Trusted Advocates made connections with people in places familiar to them like mosques, homes, and community gathering places to engage them about the project.

Figure 4: Diagram of how Trusted Advocate model and Metro Transit public involvement support the planning process

6

Metro TransitPublic Involvement

DataCollection

TrustedAdvocate Model

ConceptPlan

Development

Final Metro Transit CCTSS Planadopted by

Metropolitan Council

Empower community members to participate and comment on concept plan

Trusted Advocates reach into the community for input on origins anddestinations

Collects Informationfor Metro Transit

planners to usein preparing plan

Hosts public meetingsAttends meetings

Invites comments viaelectronic media, mail

Evaluation Approach

The Trusted Advocate model as used in the Transit, More than a Ride Trusted Advocate Pilot Project is the focus of this evaluation. The evaluation approach uses a qualitative interpretation of information using a semi-structured interview method with Trusted Advocates and DCC staff (5 people), reflections submitted by Trusted Advocates (7 people) and a survey of Metro Transit staff (14 people). This report uses the terms ‘participants’ and ‘respondents’ to reflect the collective responses gathered from those persons interviewed and surveyed. Responses are specifically attributed to DCC staff, Trusted Advocates, and Metro Transit staff, when this break down adds value to the analysis. A separate section of the report covers perspectives on the Trusted Advocate model, not the project, shared by fourteen community leaders in a facilitated conversation.

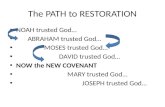

Prior to going ahead with the project, the DCC selected the following definition of Trusted Advocate.

A “Trusted Advocate is a member of a specific ethnic, racial, and/or cultural group who is perceived by other members as trustworthy, approachable and effective, particularly in navigating the cultural and language distance between the group and the majority community.” (Innovative Public Engagement Tools in Transportation Planning: Application and Outcomes)

The Trusted Advocate model is built on the understanding that underrepresented groups are often not engaged in important processes because of lack of relationships with responsible agencies. The model is characterized by the following tenets among others.

• Thereisaneutralentity,suchasanonprofitorother community organization, between the government agency and the community that adds credibility and autonomy to the engagement process.

• Transparencyandaccountabilityappliestoboththe community and government.

• Communityengagementprocessisgivenserious consideration, influences decision-making and brings community voices to the decision-making table.

The DCC and Metro Transit agreed to roles prior to initiating the project. The DCC would contract with the Trusted Advocates and act as the liaison with Metro Transit on a regular basis. Metro Transit would reorder its planning process to allow for public input before the concept plan is developed and Metro Transit would implement its own community involvement plan, while integrating suggestions received from Trusted Advocates. The Trusted Advocates would not represent themselves as employees of either Metro Transit or the DCC. They would use their own connections and ideas about how to connect with their communities and they would not work against the transit planning process, but would encourage community members to participate in the formal process.

7

A “Trusted Advocate is a member of a specific ethnic, racial, and/or cultural group who is perceived by other members as trustworthy, approachable and effective, particularly in navigating the cultural and language distance between the group and the majority community.” -Innovative Public Engagement Tools in Transportation Planning: Application and Outcomes

FINDINGS

Achieving Pilot Project Goals

Goal 1: Increase participation of underrepresented communities in the CCTS Study

At the outset of the project, the DCC and Metro Transit both valued community engagement (DCC) and public involvement (Metro Transit) as stated in each organization’s guiding principles.

The DCC’s guiding values related to the Trusted Advocate model include: Community members should have a voice in issues and decisions that directly impact them; the project should work collaboratively across borders and sectors and result in equitable benefits for all communities. Metro Transit’s guiding principle of community orientation is:

We are an important part of the Twin Cities region. We engage the community in our decision- making, provide well-crafted communication and offer opportunities for public involvement.

The Trusted Advocates, DCC staff and Metro Transit staff identified the primary purpose of the collaboration to be trying a new model to engage underrepresented community members (new immigrants, persons of color, persons with disabilities and low-income persons) in the public decision-making process governing the CCTSS. Trusted Advocates noted that building capacity in community members to participate in formal public processes was a secondary reason for the project. Not only did all participants believe that the primary purpose of the project was to increase the engagement of underrepresented communities in the decision-making process, they also agreed that it had accomplished this goal. The data supports this. Trusted Advocates averaged 11 individual community engagements each, 103 in total. This resulted in connecting with 1,200 residents and business owners in the study area and collecting 700 origin-destination data points from them. A minimum of 85 percent of the connections made by the Trusted Advocates was within the target communities. These connections were in addition to the public involvement through Metro Transit’s public process where they met with over 40 community/neighborhood groups and 700 individuals prior to the creation of the concept plan and revisited many of these stakeholders prior to the presentation of the recommended plan. Before release of the recommended plan, Metro Transit received over 800 public comments and hosted five public meetings that attracted 91 people. Ten of the 91 meeting attendees participated because of Trusted Advocate outreach. There is no baseline data to use in evaluating the increase in engagement of underrepresented community members in the CCTSS public process as compared to other transit service studies. Although there may be some overlap in participants in the Metro Transit public involvement and the Trusted Advocates

8

connections, at a minimum the 700 data points submitted to Metro Transit through the Trusted Advocates’ engagement activities were nearly all from underrepresented people, who although very welcome, would otherwise not have participated in the Metro Transit planning process.

Figure 5: Trusted Advocate Outreach by Community Engaged

*Engagements included under “communities of color” are not duplicates.

This chart represents the percentage of 103 engagements that were tailored to or had majority participation by different community groups. Source: Trusted Advocate Project Files. District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and Minneapolis

Trusted Advocates’ engagement of community members in places they are familiar with like their homes, community spaces, or religious centers is one of the fundamental reasons for using the Trusted Advocate model. How the Trusted Advocates chose to engage their communities was up to their discretion since they are the most closely connected to their individual communities. They independently developed and implemented engagement strategies best suited to their specific constituents. There was lots of variation and it required adapting initial strategies to new venues. Some asked to have the CCTSS information added to a standing meeting of their community members, others were more informal such as door knocking, bus stop interviews and talking around a kitchen table. One Trusted Advocate used her connection with a local high school and her daughter’s relationships to get input from younger residents, elders living in the Kings Crossing, and residents of the Aurora St. Anthony neighborhood, Frogtown (St. Paul District Council 7) and Summit-University (St. Paul District 8). Success using community-based organizations as a connector varied. A Trusted Advocate in Cedar Riverside found the most effective way to engage the Somali, Oromo, Korean and other new immigrant was through already scheduled meetings of existing organizations and the local mosque. She recommended that separate meetings be held by gender to maximize participation of the Somali and Oromo communities. A Trusted Advocate working in the disability community found that her best resource was learning from Advocating Change Together, an advocacy organization for persons with disabilities, and by meeting people in their homes. A female

9

Students5%

African American 4%Elders2%Hmong2%

DisabilityCommunity9%

East African12%

Communitiesof Color12%

Other/Non-Specific15%

New American19% Low Income

20%

Other12%

*

Trusted Advocate, who connected with the Asian American community, found that door knocking in neighborhoods was not productive but interviews at bus stops were especially useful with women and children. She noted that men were more difficult to involve in conversations.

Figure 6: Trusted Advocate Approaches to Engagement

This chart represents the percentage of 103 engagements for which Trusted Advocates used the listed method or approach. Source: Trusted Advocate Project Files. District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and Minneapolis

Figure 7: Metro Transit Public Involvement by Type of Response

Source: Metro Transit CCTSS Concept Plan Outreach

10

One on Ones8%

Interviews8%

Door Knocking9%

Community Gathering10%

Small Group12%

Tabling17%

Meeting25%

Other11%

Kitchen Table 5%

Bus Stop Interviews 2%

Flyer Distribution 2%

Publication 2%

Email 29.4%

Comment Cards 58.3%

Customer Feedback 5.4%

Letter .4%

Fax .1%

Petition .1%

Public Hearing Testimony 5.8%

Twitter .4%

Facebook .1%

sessions where Metro Transit staff attended with the Trusted Advocate. In addition, Trusted Advocates had email and phone access to the Metro Transit staff to ask questions that emerged during their work. Directly accessing Metro Transit staff, if they chose too, built their capacity around working with the government bureaucracy. By participating in preparing comments on the Concept Plan and attending one or more of the five public meetings, the Trusted Advocates directly interacted in the public process, which is fundamental to public decision making. The Trusted Advocates did not suggest a need for more frequent meetings, but the DCC staff and Metro Transit staff believed that more frequent updates and meetings, when necessary, would be useful in a future project. Metro Transit planners felt a need to stay better connected with where the Trusted Advocates were working and what they were learning as the planners proceeded with their planning projects. This was not expressed to limit Trusted Advocates, but to keep the planners feeling more connected.

The longest interaction between the Trusted Advocates and Metro Transit was the training for the CCTSS. Although the Trusted Advocates expressed confidence in their personal transit literacy going into the project, they found the Metro Transit training and information helpful in understanding the CCTSS and details of the transit routes to share with community members. While the Metro Transit staff recognized the Trusted Advocates’ transit literacy

The Trusted Advocates were selected for their advocacy experience, their residence, connections with underrepresented communities on the Central Corridor and their experience with and knowledge of transit. One of the project goals was to build their capacity with government decision making and planning by working with Metro Transit staff through their direct interaction as collaborators, not recipients, with Metro Transit. The Trusted Advocates also learned about the specifics of the CCTSS and how to share the information and the tools required by Metro Transit, which necessitated some problem solving by the Trusted Advocates. Trusted Advocates were also asked about many non – CCTSS related transit questions that they followed up on with Metro Transit staff. Besides building their own capacity, the Trusted Advocates served as capacity building agents for underrepresented community members by sharing transit information and the CCTSS process with them so these community members learned about how transit works along with providing input on their transit needs. Metro Transit staff built their capacity by meeting with representatives of these communities to share information about transit planning and services, answer questions and receive input.

The interactions between Trusted Advocates and Metro Transit staff occurred with two formal meetings and in at least four engagement

Another anticipated benefit of the Trusted Advocate model is to increase participation in the formal government public processes by having the Trusted Advocates encourage community members to participate in these public meetings too. In this project the results were mixed. According to both Metro Transit staff and the Trusted Advocates, Trusted Advocates participated in the five Metro Transit public meetings/hearings to give input on the concept plan for the CCTSS on the draft concept plan. However, despite sharing the meeting dates and times with their community members, Trusted Advocates that were interviewed reported there were very few instances where community members they had connected with actually attended the public meetings held by Metro Transit. According to DCC records, 10 of the 91 attendees at the five Metro Transit public meetings were there because of their interaction with a Trusted Advocate. Metro Transit staff expressed the hope that underrepresented community members’ participation in this component of the formal public process would have been stronger and more visible.

Goal 2: Promote learning by building capacity of underrepresented persons, including learning from available communication tools and information

11

was very good, they believed they had an essential role in training and providing information to the Trusted Advocate. There was a recognition by both the DCC and Metro Transit that the expediency required to implement this project resulted in miscommunication over the timing and availability of Metro Transit’s information, including multi-lingual copies of the origin and destination survey tool, which was the data collection mechanism for the Trusted Advocates. All parties agreed that future projects should have a longer timeline for planning and the resources to provide for interpreters, translated materials and different information formats.

One Trusted Advocate in the Cedar Riverside area worked with Metro Transit to adapt the data collection process to more expeditiously gather origin and destination information at large, multi cultural and multi-lingual gatherings. With limited translated materials and no interpreters, it required ingenuity. By using a map that Metro Transit created for another meeting, the Trusted Advocate could ask these non-English speaking community participants to put dots on the map. The data was later recorded for Metro Transit’s use.

Another Trusted Advocate in the Frogtown neighborhood, who stressed the importance of her accuracy with transit information when she connected with her community, routinely relied on Metro Transit staff to answer specific questions and help her understand the mapped materials so she could correctly explain them and answer questions.

The Trusted Advocate working with the disability community had strong capacity in transit planning, transit routes and working as an advocate with government when she took the job. She got her first experience with

engaging community members and learned not to follow the “dead ends” when trying to make connections into the community.

A Trusted Advocate working with Asian-American communities set out a goal to interact with her Asian community members about how to use public transit because many community members drove cars and did not know about transit services despite their proximity and availability. Although not convinced that she changed any lifestyles in the short run, she believed that she succeeded in educating Asian community members about how to use public transit and the opportunities it provided to them.

Goal 3: Generate a transit service plan that serves the needs of those who live on the corridor (with particular attention to underrepresented communities) The Trusted Advocate model is designed to hear voices from underrepresented communities that often go unheard in order to influence public decisions that create more equitable outcomes. This project was perceived to have generated a transit service plan through an inclusive planning process that serves the needs of all those who live on the corridor with particular attention to underrepresented communities. The participants in the evaluation expressed confidence that the increased engagement of underrepresented communities through the Trusted Advocates achieved this result. When specifically asked, participants agreed that the CCTSS’s outcome was likely to be more equitable for underrepresented communities as a result of the input gained through the Trusted Advocates.

Confirming the importance of the information shared by the Trusted Advocates, Metro Transit staff reported that the information received from the Trusted Advocates was important or essential to developing the recommendations of the CCTSS and that at least one specific recom-mendation was changed in the Concept Plan as a result of

She believed that she succeeded in educating Asian community members about how to use public transit and the opportunities it provided to them.

12

this project. With over 1,200 documented individual contacts and 700 data points combined with the willingness of Metro Transit staff to receive the input, there was strong potential for the Trusted Advocates’ connections to influence the decision. Metro Transit community outreach staff reported that the Metropolitan Council’s policies around public involvement support enhanced and new ways to engage stakeholders and community members of which the Trusted Advocate model is just one example. Although this pilot project did not result in specific systems changes in the form of new engagement policies by Metro Transit, the internal atmosphere and attitude are becoming more open to new ways to directly connect with community members, in part, due to this project.

When restating this question in the form of “did the project directly influence the recommendations in the CCTSS,” the answer from participants in this study was ‘”yes.” One specific example consistently emerged to demonstrate this conclusion, Ravoux Hi-Rise. Here is why. Transit service, Route 94, the segment that connects Ravoux, a 218-unit multi-family, public housing complex at Saint Anthony Avenue and Marion Street to University Avenue bus service, was planned for elimination. If eliminated, the residents, most transit dependent and many of whom are disabled, would have been without a transit connection to University Avenue service unless independently traveling over five blocks to University Avenue. Anticipating an issue, the DCC staff encouraged the Trusted Advocates for the area and disabled community to arrange a meeting in the meeting room at Ravoux. They invited Metro Transit staff to attend so the staff could hear first-hand the residents’ negative responses that included their personal accessibility challenges should the bus service be eliminated as planned. The residents of Ravoux provided Metro Transit staff with their origin-destination information (where they travel and on what days/times of day they travel). The Metro Transit staff listened, reviewed and revised their recommendation to provide transit service that much better aligns with the travel patterns of the Ravoux residents. Through a rerouting of the Route 16 on University Avenue to Ravoux, residents will either transfer to the METRO Green Line or stay on the Route 16 to access their favorite destinations, like Midway Shopping. The Ravoux experience was not limited to the Trusted Advocate having residents of Ravoux Hi-Rise share their concerns about the loss of a bus stop for their building with Metro Transit staff. Instead it was an opportunity to work as partners with Metro Transit staff, Trusted Advocates and residents sitting around a table. This left the Trusted Advocates and Metro Transit staff understanding that they had jointly developed a shared solution with residents that was more equitable than the earlier proposal. As one transit planner, who requested no attribution, stated:

13

This addition (Route 16) to the plan (CCTSS) was a result of a Trusted Advocate meeting with area residents. The information gained from this meeting helped us understand the travel behavior of residents and the need for a continued transit connection to University Avenue.

she “communicated directly and honestly with the Trusted Advocates even around issues that were not necessarily happy ones.”

There were other opportunities to learn from each other. Trusted Advocates became more acquainted with Metro Transit planning language through their connections with transit service planners. In turn, the planners learned more about how community members describe their bus service. For example, the man who calls the community connector Route 21 from St. Paul to Minneapolis “I will get there when I get there.”

Project operational issues raised potential challenges to the relationship for the Trusted Advocates, DCC staff and Metro Transit staff, especially since this project was not identified and integrated into the original public outreach and communications plan prepared by Metro Transit. However, none of the participants let these issues derail the project.

Significant issues included the Trusted Advocates and DCC staff not fully understanding the decision-making process for the CCTSS final recommendations, delays in getting materials, and feeling that some questions ‘disappeared’ when the Metro Transit CCTSS project team did not have the information because the question belonged to another part of the government organization. Improving communication through more routinized opportunities and providing enough up front time to plan the project were identified as important for the next project. Also, Metro Transit staff would benefit from more resources to prepare multi-lingual information and maps or graphics that could be understood by different cultures, who do not use maps or who read maps differently. In addition, the sense of sharing might be improved by having the Metro Transit staff and the Trusted Advocate(s) appearing together at DCC Governing Council and Corridor Management Committee meetings to discuss the work rather than reporting separately and, thus, visually separating their roles. This would also go a long way in building capacity for the Trusted Advocates because presenting before formal government bodies is a step to being comfortable sitting at these public decision-making tables.

Goal 4: Strengthen the relationship between Metro Transit and under-represented community members to create a shared solution that will influence changes in the system for future planning.

The DCC initiated this project to learn more about the Metro Transit planning process and to work with Metro Transit community outreach and planning team to provide for early engagement with underrepresented communities around the CCTSS. While planning the work, the DCC anticipated that by working together they would build a stronger relationship between Metro Transit, the DCC staff and the Trusted Advocates. For Metro Transit staff, the opportunity to engage more transit dependent residents in the CCTSS and to collect more origin and destination information from this population was a compelling reason to get involved. At the end of the project, DCC staff and Trusted Advocates expressed an increased level of trust for the ‘people’ of Metro Transit that they met through the project, but had not increased their trust for the Metro Transit organization. However, developing trusting relationships with the people in the organization is a critical first step in trusting the organization since the people are the organization.

Metro Transit demonstrated elements of trust and confidence in the Trusted Advocates by agreeing to shift their timeline at the beginning of the work, by not being involved in the formal decision over whom to contract as Trusted Advocates and by not interfering with the independent nature of the Trusted Advocates’ job. Metro Transit staff par ticipated in community engagement meetings with the Trusted Advocates on at least four occasions and they repor ted that the project was overall very helpful to their work. They expressed no negative comments about the DCC staff or Trusted Advocates. The Route 16 solution to the Ravoux Hi-Rise service significantly strengthened the feeling that this was a shared solution among the par ticipants. As evidence of trust that emerged during the process, Metro Transit staff member, Jill Hentges, explained that

14

Perhaps the best evidence of a growing positive relationship between Metro Transit and underrepresented communities is a statement by Metro Transit staff member, Karen Underwood.

Being involved cross-culturally (outside of Metro Transit) for decades, including with refugees and immigrants and teaching English to speakers of other languages, I’ve been concerned for a long time with how we can effectively communicate with and get input from the public. I cannot tell you how THRILLED I was to hear of the Trusted Advocate project!!! I did not work directly with the TAs, except one public meeting. I only wish I could have been more directly involved! Because of the Trusted Advocate project, I am MUCH more confident about the Central Corridor service plan.

Goal 5: Bring a new model of engagement to the Twin Cities region

The project successfully brought a new model of engagement to the Twin Cities region. Local community engagement leaders were familiar with the model as used in Oakland and Seattle, but it had not been implemented in the Twin Cities. With the pilot on the CCTSS completed, the DCC is now using the Trusted Advocate model to manage community engagement in Corridors to Careers, a partnership with Ramsey County. This pilot project focuses on connecting residents and employers to workforce and training resources. A recent land use pre-planning study for the Bottineau Corridor LRT suggested that the Trusted Advocate model be considered as an engagement model. Metro Transit staff saw opportunities for using it in bus shelter design and in the Midtown Corridor alternatives analysis. As interest in this approach grows, it is important to provide a framework to evaluate when it can be an effective engagement tool for underrepresented communities to learn about and influence a public decision.

15

PROJECT GOALS DCC/TRUSTED ADVOCATES METRO TRANSIT

Goal 1:Increase participation of underrepresented persons in the CCTSS process

Documented connections with 1,200 individuals, who provided 700 origin and destination data points to Metro Transit.

Public meetings held by Metro Transit had 91 participants – other outreach efforts gathered over 800 comments. There was substantial outreach at other public meetings about the CCTSS project beyond the scheduled public meetings.

Goal 2: Build capacity in underrepre-sented community members

Directly connected 9 Trusted Advocates from underrepresented communities with the Metro Transit public agency staff using a collaborative and information sharing model; shared transit route information and user details with under-represented communities to get their input and educate them about transit and the CCTSS.

Provided training and information materials to 9 Trusted Advocates; shared information and an-swered questions from Trusted Advocates and DCC in a collaborative manner; participated in training sessions and meetings with Trusted Advocates at the table sharing questions and information on the CCTSS. Staff welcomed the work of Trusted Advocates to get more com-munity members into the formal public process. Had anticipated the Trusted Advocates might increase attendance of more underrepresented community members at Metro Transit’s public meetings.

Goal 3: Generate a transit service plan that serves the needs of those who live on the corridor, with particular atten-tion to underrepresented communities

Confident that the inclusion of community input gathered by the Trusted Advocates in the form of 700 data points and the information shared created a plan that serves the needs of people, especially underrepresented persons. Specific example: Ravoux Hi-Rise and re-route of #16 service.

The information received influenced the transit service plan to better serve underrepresented communities as a result of the Trusted Advo-cate input from their constituencies. Specific example: Ravoux Hi-Rise and re-route of #16 service.

Figure 8: Summary of Evaluation Responses

16

PROJECT GOALS DCC/TRUSTED ADVOCATES METRO TRANSIT

Goal 4:Build stronger relationships between the underrepresent-ed communities and Metro Transit that will influence change in the system

The collaboration left Trusted Advocates and the DCC staff feeling more trusting of Metro Transit’s personnel assigned to the CCTSS proj-ect primarily due to the back and forth nature of the work and face-to-face, phone, or email communication. This was somewhat challenged, but not undermined, by miscommunication about the way comments would be input into the final plan and delays in getting started. This did not eliminate any concerns about the Met-ro Transit as a public organization, but began to build the relationship between the people of the organization and the Trusted Advocates, which is a start at trusting the organizations.

Metro Transit staff acknowledged the value of the information and the perspective of the communities. Specific relationship building issues were not addressed with the exception of want-ing more frequent communication on a future project. No negative comments emerged about the DCC or the Trusted Advocates.

Goal 5:Bring a new model of engage-ment to the region

This was believed to be the first example of using the Trusted Advocate model in planning in the Twin Cities. The model is being applied to a project designed around connecting workforce resources and employment opportunities with the DCC as the project manager for the Trusted Advocates.

The information was considered influential in the recommendations of the CCTSS. Suggested improvements for clarity in roles, timelines and communications to the operations of the model would need to be worked out to use it again. There were two suggestions for where this mod-el might work again in Metro Transit projects including the Midtown Greenway Alternatives Analysis and bus shelter design and placement.

17

IMPROVING THE MODEL

DCC/TRUSTED ADVOCATES METRO TRANSIT

Taking more time upfront for joint planning and adapting the public process to the work

DCC and Trusted Advocates generally agreed that it was critical to take more time to carefully plan the project in collaboration with Metro Transit to avoid miscommunication about the process and expectations of the Trusted Advocates. It was suggested that a clear road map of the process be developed. In addition, to help everyone better understand the process, it is important to explain in advance of the engagement process how Metro Transit will address questions that come up but are not associated with transit or the study and to reconfirm this when specific instances arise.

Metro Transit staff felt that taking more time to plan the collaborative project was critical to be successful. Delays in providing the Trusted Advocates with critical information for their work and a clear timeline of expectations emerged. In addition, planning in advance how to maximize input through tools (like the origin and destination gathering tool) rather than planning on the fly to get valuable input. It would also provide time to prepare multi-lingual materials. Metro Transit staff believed the time demand for this project as part of the CCTSS was moderate.

More communication between Trusted Advocates / DCC and Metro Transit project staff

The Trusted Advocates and DCC valued the face–to-face meetings with Metro Transit staff and the access via phone and email. More is better without formalizing the work too much.

Metro Transit staff believed more direct com-munication in a systematic way with the Trusted Advocates about their work would be helpful to project planners. These would not necessar-ily be face-to-face meetings, but might be quick updates and status reports.

Carifying roles and responsibilities

DCC staff did not have difficulty keeping its role managing the Trusted Advocates separate from Metro Transit. For the benefit of the Trust-ed Advocates work, the DCC expressed the need to better define the role of the Trusted Advocate as that of a community advocate, not a spokesperson for Metro Transit. Some Trusted Advocates found themselves perceived in this way by community members. The question of whether or not the advocate can continue to ‘advocate’ about a decision independently or after the decision is made emerged as a future issue to address.

Metro Transit staff identified the role of the Trusted Advocates in the CCTSS process as an additional way to get input. The input was appreciated. However getting underrepresented community members to participate in the public process is also desired.

18

19

IMPROVING THE MODEL

DCC/TRUSTED ADVOCATES METRO TRANSIT

Identifying potential project management responsibilities and funding (foundations, government, consultants working for government or foundations, community-based organizations, non-profit advocacy organizations, other)

The DCC staff and Trusted Advocates believe that community-based organizations are the place for this work. This is a community-based initiative and needs to be led and implemented through an organization connected to the community. One Trusted Advocate believed that community-based organizations should be given funds directly to organize their own communi-ties because of the time that they are expected to invest in assisting Trusted Advocates in the engagement work.

Metro Transit staff was spread across the spectrum of management options, some identifying several. The majority of respondents were evenly split between community-based organizations because they are connected to communities and know them best; and government managing the work because it will build connections and trust between government entities and underrepresented communities. Funding was not addressed in these comments.

Resources The topic of resources came up in the context of providing multi-lingual and information that is more easily understood by these communities. For example, some community members are not map literate and unfamiliar with transit routes so this required a lot of verbal explanation by the Trusted Advocates. Having interpreters available for Trusted Advocates working in communities like Cedar Riverside or Skyline Towers where there are a lot of languages spoken would make the work more accessible.

Metro Transit staff recognized the value of having more time and resources to anticipate and prepare materials in advance of the work beginning. The Metro Transit staff found that the project moderately increased their workload.

19

who is free to express opinions on a public project, independent of the role of being a Trusted Advocate. Finally,

Trusted Advocates do not create adversity within a project, but build a way out of adversity by creating positive relationships and providing information to

government entities from persons who might be potential adversaries to the public decision-making process.

The relationship of Trusted Advocates to community-based organizations surfaced deep discussion about the sensitivity that is required while working in the world of community – not government. For the Trusted Advocate to be able to garner trust among community-based organizations creates its own set of challenges to the Trusted Advocate model. Trusted Advocates need to respect and, hopefully, get support from community-based organizations. However, Trusted Advocates should not be limited by community-based organizations that have established strong, historic leadership and may be considered the sole organization speaking for a particular community. There are times when it is appropriate to let a community-based organization take the lead on some connections that might otherwise be handled by Trusted Advocates and compensate these organizations for their work.

have time to provide information from the community back to the government agency. However, it is also

important that the timeline not be extended so long that the information is not relevant, too late or that there is no energy around the topic.

The work must be sustainable. This might mean looking at it from the perspective of a public policy maker who will rely on the information as a way to make short- and long-term decisions that reflect community needs or creating a change in the system through public policy. And, ultimately, it should build the capacity of community members so they are seated at the de-cision-making table as decision makers.

The role of the Trusted Advocates is to connect with community members where they have established relationships, to share information about the project and to collect information to bring back to the agency, in this case, Metro Transit. Trusted Advocates are not intended to represent the community as their spokespersons. It was acknowledged that the role of the Trusted Advocates is that of an independent advocate,

To better evaluate the potential use of the Trusted Advocate model in future projects in the Twin Cities, fourteen community leaders from regional and local government, advocacy organi-zations, community-based organizations and the philanthropic community, were asked to share their ideas about the Trusted Advocate model. The conversation was intentionally facilitated to be an open exchange of perspectives rather than a formally structured discussion. Many of the comments directly or indirectly dealt with building trust between government, community-based organizations and community members. It was agreed that this requires candid, honest and sometimes painful conversations. A synopsis of the discussion follows.

There are many future opportunities to use this model in a variety of public projects, but there must be a real opportunity to influence the resulting decision and it must matter to people in their daily lives.

Building trust between government officials/staff and Trusted Advocates requires allowing enough time to integrate the Trusted Advocate project into the government’s process to assure that the Trusted Advocates have time to learn about the project. This will allow the Trusted Advocates to accurately share information with community members. It will also assure that the Trusted Advocates

20

Trusted Advocates do not create adversity within a project, but build a way out of adversity.

CONVERSATION WITH COMMUNITY LEADERS ABOUT THE MODEL

Trusted Advocate work on a public infrastructure project should be treated the same as public art, which is an eligible expense. Options for providing funds to community-based organizations managing the project include using direct payments from government or having government pass funds through a foundation to a community-based organization. The latter approach provides a buffer between the Trusted Advocate project manager and the government entity that is making the decision on the project.

Community leaders believe that the success of the Trusted Advocate model is irrevocably tied to the ability of government officials/staff and community members to build trusting relationships. This does not mean melding their roles — government needs to be government and community needs to be community — but it does mean having candid, honest and, sometimes, painful conversations with each other about how to work together to create stronger communities.

21

Despite potential challenges around community-based organizations and their relationships with each other, with their community members and with the Trusted Advocates, there was clear consensus that managing a Trusted Advocate model was best left to community-based organizations. This is fundamental to the model because it is about reaching into the community with trusted community members serving as Trusted Advocates, and bringing information back to government staff to influence projects’ decisions. The Trusted Advocate model has Trusted Advocates serving a distinctly different role than the role served by people hired to be public liaisons to the community.

Who manages the Trusted Advocate project raises the question of who pays for it. There is a sentiment that since public decisions are being made based on this engagement, the cost of the work should be covered by the government entity benefitting from it. For example, the cost of the

CONCLUSION

The Transit, More than a Ride Trusted Advocate Pilot Project provides a case study in the Trusted Advocate model in the Twin Cities region. The pilot project, a partnership between the District Councils Collaborative and Metro Transit around the CCTSS, was initiated by the DCC. Metro Transit agreed to join the DCC in trying something new for engaging underrepresented communities. The project, accomplished its goals of increasing representation of underrepresented persons into the Metro Transit CCTSS, building capacity, generating a transit service plan that met the needs of the communities, creating stronger relationships among the DCC, Trusted Advocates and Metro Transit and implementing the Trusted Advocate model in public planning in the Twin Cities. The participants recognized the results, the innovation and the opportunity that this model created as an engagement tool to reach underrepresented communities. Perhaps the project’s biggest short-term success was that it changed Metro Transit’s transit service plan by including a solution that emerged from a meeting with Metro Transit planners, Trusted Advocates and low-income residents of Ravoux Hi-Rise.

The pilot project also provided an opportunity to ask what is fundamental to the success of the Trusted Advocate model and how it might be used in the future. Community leaders from regional and local government, community-based organizations and advocacy groups met to discuss this. They are enthusiastic about seeing the model used on other public projects to reach more voices. However, they caution that any engagement strategy, no matter how innovative, is ultimately about trust between public agencies and community. It is having the commitment to build this trust through open, honest, sometimes painful conversation, among the entities involved in the work that fundamentally matters.

Is there an advocate for the model within the govern-•ment agency who can garner support from others and help through the challenges?

Is the project so controversial that a Trusted Advocate •will be suspected as having an agenda in the role of sharing information about a public agency’s project?

Is there a community entity/organization that has the •established community relationships to identify Trusted Advocates that can succeed and not be viewed as hav-ing their own agenda or the public agency’s agenda?

Is the project close to peoples’ daily lives–does it •matter to them so they will want to participate?

Is the timeframe practical to get the Trusted Advocates •prepared for the work? Will there be time to prepare materials including translations, interpreters, materials that work for groups with mixed demographics (e.g. Oromo, Somali, Korean at one meeting)? Is there time to get input from the Trusted Advocates on the mate-rials since they will be using the information and may have ideas about how to communicate effectively with their specific community members? Is the timeframe being used as an excuse not to try the model?

Will the project result in any changes to the system? •(e.g. new engagement policies; new decision makers at the table)

Discuss and determine how to assure underrepresented communi-ties from the outset that the project has trust built into it.

Which partners (organizations) are best positioned to •manage the Trusted Advocate part of the project? This will impact the ‘trustfulness’ of the work. Government,

The pilot project, along with the growing popularity of the Trusted Advocate model as a tool to reach underrep-resented communities in public decision-making, created an opportunity to evaluate and raise questions about what is fundamental to the model’s success. These items come out of this work with the Transit, More than a Ride Trusted Advocate Pilot Project. Although the ‘nuts and bolts’ operational details can make or break a project, specific improvements to these are not included because they did not surface as compelling issues on this project and they can be addressed in a project management format using other sources. The DCC is addressing some of these specific implementation details, along with the broader issues described below, in its planning work around the Corridors to Careers.

Agree upon shared values around engagement

• Avoidmistrustbyhavingthepublicagencyandthemanaging partner of the Trusted Advocate project (in this study a community organization) share and agree upon values around engagement before jointly embarking on the Trusted Advocate project. (DCC has done some work around defining this relationship as part of the Corridors to Careers project.)

Identify the fundamental and practical elements of the project that make it a good fit or a challenge for this model.

Is the project expected to increase equity, a term •which often emerges? If so, is there an agreed upon understanding of what that means to the specific proj-ect being considered?

Is the project connected to a decision that can be •influenced by this model? (Avoid engagement for engagement’s sake.)

22

ITEMS TO CONSIDER

Clarify the Trusted Advocates’ roles so their indepen-•dence and community advocacy role is not confused with being PR people for a government entity. It helps if all parties can articulate their roles and the roles of each other, in a short verbal description (talking points) and a written version because questions will arise from the public agency staff, the Trusted Advocates and the gen-eral public. Help maintain this understanding and build the relationship by regular communication between all parties. Public planners may need to know how their project is being perceived and impacted from this ‘invis-ible’ work by the Trusted Advocates so the planners retain their confidence in the process.

Create opportunities to share information and have •open, direct conversations among Trusted Advocates themselves and with the public agency staff rather than staying only within the technical comfort zone.

Determine if it is important for capacity building of •underrepresented community members to have Trusted Advocates invest a lot of energy into having community members attend public meetings held by the public agency. If hearing these voices through the Trusted Advocates’ work is not enough, why not, and what are the barriers to participation by community members, can they be ameliorated?

Explore ways to build stronger partnerships by sharing •the agenda setting at joint staff and Transit Advocate meetings. Visually reinforce the partnerships between the Trusted Advocates and the public organization by giving joint presentations about the project. Take care to avoid creating confusion between the public agency staff ’s role and that of the advocate, but consider look-ing like a team before the public and the community.

Build some evaluation into the project along the way •that allows for some observation of the public and Trusted Advocate processes. This would be useful in evaluating the work.

foundations, community-based organizations and local non-profits have served in this role.

Who will pay for the Trusted Advocate part of the •project? This may impact the perception of the trustful-ness of the work from the public agency, the underrep-resented communities and the general public.

Will community-based organizations support this •work? They will be relied upon for helping get people connected to the Trusted Advocates through their community meetings and their own community-based relationships. These entities are not being paid to engage their constituencies, but are often expected to participate. If useful, consider using a model of pro-viding grants or to cover meeting expenses to these organizations to do the some of the work.

Here are some places to help build trust.

Build the Trusted Advocate project’s work into the •public agency’s public involvement plan so that it is connected into the bigger piece and can be under-stood by all parties. Be flexible, but not hasty, in moving the schedule around and communicate it regularly. Since process changes generate distrust, ideally address these up front and in an on-going manner. Be very clear about the public decision-making process and at what points and how the Trusted Advocate input and their constituencies can influence a decision through an understandable road map.

Clarify the roles and responsibilities of the public agency •staff that will be working with the Trusted Advocates. These include who is the project lead, who on the staff makes decisions, who is the go-to-person for the Trust-ed Advocate, and, very importantly, how, by whom and when will questions that the public agency staff, who are connected to the project, can’t answer get addressed.

23

APPENDIX 1

Resources

Central Corridor Transit Service Study Recommended Final Plan, November 2012.

Central Corridor Transit Service Study, Existing Conditions Report, Metro Transit, 2012.

Central Corridor Transit Service Study Concept Plan Outreach, Metro Transit, June 2012.

Community Engagement: Stakeholder Perspectives on the 2011 Grant Making Process, Shelton, Wilder Research, April 2012.

Connecting to the Future: Inclusive Outreach and Engagement in the City of Tukwila, Forterra, 2013.

Corridors to Careers Community Engagement Workplan, District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, February 2013. (Available from District Councils Collaborative upon request.)

Proposal for a Trusted Advocate Community Engagement Pilot Project to Support the Central Corridor Transit Service Restructuring Study, October 21, 2011.

Transit, More than a Ride Trusted Advocate Pilot Project Interim Report, District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, June 2012.

Transit, More than a Ride Trusted Advocate Reflections, District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, 2013. (Available from District Councils Collaborative upon request.)

Trusted Advocates: A Multicultural Approach to Building and Sustaining Resident Involvement, Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2007.

Use of the Planning Outreach Liaison Model in the Neighborhood Planning Process: A Case Study in Seattle’s Ranier Valley Neighborhood, Oshun, Ardoin, Ryan, Hindawi Publishing Corps, 2011.

24

APPENDIX 2

Agenda for the Community Leaders Conversation about the Model

1. Welcome and Introductions 2. Overview of the DCC’s Transit, More than a Ride Trusted Advocate Project 3. Questions for discussion-sharing your perspectives reflecting your different roles: • WhatarethefundamentalqualitiesforaTrustedAdvocatemodeltobesuccessful? • WhenisaTrustedadvocatemodelausefultool? When doesn’t it make sense to devote resources to the Trusted Advocate model? • WhatistheroleoftheTrustedAdvocateduringtheprojectandaftertheprojectends? • WhatentitiesarebestsuitedtomanageTrustedAdvocateengagementandwhy? (foundations, foundation w. consultant, government, government w. consultant, community based organizations, advocacy organizations, other) • Whatistherole/expectationofcommunity-basedorganizationsinassistingTrusted Advocates if their organization is not receiving funding for their time? • Whopays?Doesitmatter? • WhatneedstobesharedaboutwhatwelearnedfromourDCCexperience?Howshould we share it? What are our next steps in preparing to share information? What communication tools/venues do you suggest?4. Wrap-up and thank you

Attendees: Russ Adams, the Alliance for Metropolitan StabilityAnne Gomez, Trusted Advocate Transit, More than A Ride Cedar Riverside Jill Hentges, Metro Transit, Community OutreachSusan Hoyt, FacilitatorKaryssa Jackson, District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and MinneapolisLaura LaBlanc, Fullthought, NotetakerKenya McKnight, Community Person, Transportation Advisory Board (Metropolitan Council)Lisa Middag, Hennepin CountyJennifer Munt, Metropolitan Council, CouncilmemberJoo Hee Pomplun, Asian Economic Development AssociationJonathan Sage-Martinson, Central Corridor Funders CollaborativeCarol Swenson, District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and MinneapolisLisa Tabor, CulturebrokersLucy Thompson, City of Saint Paul(In addition, Mary Kay Bailey, Corridors of Opportunity Living Cities and Jon Commers, Metropolitan Councilmember were interviewed).

25

26

Rosa Parks Diversity Leadership Award

Ashley Ver Burg’s remarks:This award is relatively new and has only been presented once before in our chapter's history…however it embodies the very premise under which the Women's Transportation Seminar was founded: the more diverse we are as an industry, the more we can achieve, the more we can innovate, and the more we can advance. To this end, the Rosa Parks Diversity Leadership Award recognizes astute organizations and individuals that are bold in their support and promotion of diversity, inclusiveness, and multi-cultural awareness…which is why we are honoring the Trusted Advocates Program today.

The project was a joint effort between Metro Transit and the District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and Minneapolis…to engage a diverse body of transit users in preparing a connecting bus service restructuring study in preparation for Green Line light rail. Nine community leaders were hired on as Trusted Advocates to represent and engage their families, friends, neighborhoods, and communities in providing substantive, meaningful feedback on transit service plans.

Suado Abdi, Hadi Abdidubul, Mee Cheng, Sulekha Diriye, Anne Gomez, Henry Keshi, Sheronda Orridge, Tim Page, and Kjensmo Walker were the nine leaders who fulfilled the prominent and respected role of Trusted Advocate for the Somali, Southeast Asian, African-American, low-income, youth, disabled, and heavily transit-dependent communities. With their leadership, under Jill and Karyssa's partnership, guidance, and vision, the Trusted Advocates Program acknowledged and applied the critical practice of engaging diverse perspectives in transit service planning. Rather than assuming racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic perspectives would be represented in the traditional public participation process, the Trusted Advocates Program boldly pursued these diverse opinions and brought voices to the table to effect change in the decision-making process.

This commitment to diversity in leadership is symbolic of the principles guiding WTS as a trailblazing organization in the positive transformation of the transportation industry, which is why it gives me great pleasure to congratulate Jill and Karyssa as recipients of this year's Rosa Parks Diversity Leadership Award.

April 10, 2012

Ashley Ver Burg (center), this year's WTS Minnesota Programs Director, presents the 2013 Rosa Parks Diversity Leadership Award to Karyssa Jackson (left), and Jill Hentges (right) for their work on the Trusted Advocates Project.

For more information see our website: dcc-stpaul-mpls.org/special-projects/trustedadvocate