TRACES | Winter 2007 only.pdf · and tangled one, and it is due to this complexity that the...

Transcript of TRACES | Winter 2007 only.pdf · and tangled one, and it is due to this complexity that the...

42 | T R A C E S | W i n t e r 2 0 0 7

T R A C E S | W i n t e r 2 0 0 7 | 43

ALL

IMAG

ES C

OURTES

Y ER

IC G

RAYS

ON

44 | T R A C E S | W i n t e r 2 0 0 7

L i m b e r l o s t F o u n d

ollywood has always loved a good story. Since theearly days of cinema, producers have turned tobooks by Indiana authors, and many have beenmade into successful movies. Undoubtedly, themost famous is The Magnificent Ambersons (1942),

the Orson Welles epic based on the novel by Booth Tarkington.Despite the fact that it was severely cut by the studio, it hasalways been available on television and video. Dedicated moviefans could hardly avoid a screening of this gem.

Many other early films were not as lucky as The MagnificentAmbersons, which has the double good fortune both to sur-vive and be available. Motion picture film may be the singlemost neglected art form of the twentieth century. Whennegatives wore out, companies went bankrupt, or commer-cial potential evaporated, films died. An estimated 50 per-cent of all films made before 1950 no longer survive in anyform. Those films that do survive often find themselvesentangled in an elaborate web of copyrights, archives, pri-vate collectors, and dingy warehouses. Searching for oldfilms often evokes the adventures of Indiana Jones.

Hoosier author Gene Stratton-Porter, known for her whole-some nature novels, cast herself apart from her Indiana con-temporaries by establishing her own production company toadapt her works for the screen. This almost unique early author-producer combination has made these movies a kind of HolyGrail for Indiana film historians. Before Stratton-Porter’suntimely death in a Hollywood traffic accident on December7, 1924, her company had produced a number of pictures,notably Michael O’Halloran (1923), A Girl of the Limberlost (1924),and The Keeper of the Bees (1925). Because of the extensive workinvolved in producing a film, Stratton-Porter may also havebeen involved in the productions of Laddie (1926), The MagicGarden (1927), The Harvester (1927), and Freckles (1928), eventhough these were released after her death.

All of Stratton-Porter’s films were produced by her com-pany, but they were released by Film Booking Offices, a firmextremely particular about controlling its release prints and col-lecting them like rare gems at the end of a run. Had theybeen a little more careless about their prints, some might havesurvived in the hands of private collectors. To avoid the costsof storing flammable nitrate film, FBO melted down most ofits inventory to reclaim the silver used in the film emulsion.Only a handful of FBO’s entire output survives today, and,sadly, the Stratton-Porter films are not in that number.

Even after her death, Stratton-Porter’s stories remained pop-ular with filmmakers. RKO (a successor to FBO), made soundversions of Laddie and Freckles in 1935. Laddie sports a castincluding John Beal and Gloria Stuart—the same actress who

starred, years later, in Titanic (1997). These particular films donot appear to have been syndicated for television and are appar-ently not in the collection inherited by Time-Warner/Turner.

Three other Stratton-Porter stories, A Girl of the Limberlost(1934), Keeper of the Bees (1935), and Romance of the Limberlost(1938), were made by Monogram Pictures Corporation andare elusive today due to their rights history. All of these filmswere definitely released to television, so a large number ofprints made their way to local television stations. As yearspassed, these prints sat on dusty shelves in cold storage. Sinceno public film archive has any of these films, any surviving tele-vision prints would probably be the only copies.

The history of Monogram and its distribution process is a longand tangled one, and it is due to this complexity that the Stratton-Porter films are so difficult to find. The coming of sound filmsin the late 1920s dramatically changed the motion picture indus-try. When Stratton-Porter was working, during the silent era,practically anyone with a camera could make a profitable pic-ture. The added expense of sound bankrupted smaller pro-ducers who could not afford to upgrade their equipment. Afterthe Great Depression began in 1929, money was even tighter.The big studios were reluctant to spend money on anythingbut a sure-fire hit. The idea went through Hollywood that higherbudgets and bigger stars meant safer movies.

Ironically, this helped a lot of smaller producers. Those fewwho had survived the transition to sound realized that thedemands of the rural market were going largely unserved.Hollywood’s big-budget movies catered to big-city tastes, sothe independent producers decided to focus on small markets.This created an interesting underworld of movie productionsthat has still been largely ignored by historians. Until the adventof television in the 1950s, small-time producers catered to thesmall-town markets, making stars of people like Belita and JudyCanova—stars who were all but unknown in the big cities.

Monogram was one of the first studios to exploit this nichemarket. Whereas the smallest of the “big” studios, Universal, hadlong straddled the line by making “up-market” films like ThePhantom of the Opera (1925), it continued to make profitableseries like the long-running Cohens and Kellys films that focusedon the tribulations of a Catholic family and a Jewish family whonever seemed to get along until the last reel. Monogram, how-ever, focused solely on the small-town markets, seeing little needfor the prestige pictures until it became Allied Artists in 1953.

Stratton-Porter’s popular novels were a natural choice forMonogram. They stressed a love of nature and were generallycharacter driven, eliminating the need for expensive sets andlarge casts. A Girl of the Limberlost was one of Monogram’s mostprofitable releases of 1934. Keeper of the Bees came out the next

H

T R A C E S | W i n t e r 2 0 0 7 | 45

year, and there probably would have been another followup, butthings quickly got complicated for the little studio.

In 1935 the owner of a film laboratory named Consolidateddecided to do just that with several of his customers. HerbertJ. Yates withheld lab services from Monogram, the serial stu-dio Mascot, Grand National Pictures, and some independentproducers. He wanted to combine these small players intoone larger studio. There was little hope but to agree, sinceConsolidated was the cheapest film laboratory in town. Theconsolidation became Republic Pictures Corporation.

Subsequently, Republic released The Harvester (1936) andMichael O’Halloran (1937), which had probably been in earlyproduction at Monogram when the uneasy merger happened.Not long after the ink was dry on the paperwork, several keymembers of the new Republic team began to balk at the new man-agement. Disgusted with Yates, former Mascot Pictures chiefNat Levine splintered off to work at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer fora while and eventually retired. Dissatisfaction with Yates alsoresulted in the original owners of Monogram leaving and re-forming their own studio, which of course was named Monogram.

The New Monogram, as it was called briefly, was not tech-nically the same organization the previous one had been, butthe spiffy logo of old returned and many of the technicalstaff left Republic in favor of New Monogram as well. The com-pany dissolved in 1935 and was producing films again in 1937.Many movie patrons were unaware it had ever been gone.The New Monogram released another Stratton-Porter film,Romance of the Limberlost, in 1938. Later that year, the studioreverted to its old name, simply becoming Monogram again.

The brief interlude at Republic caused the Monogram filmsto be in a legal limbo. Since Monogram was, in part, a collectionof very small independent producers, the copyrights for indi-vidual films were often unclear. Even more confusing was thepuzzle of whether the pre-Republic films made by Monogrambelonged to Republic or to the New Monogram. It was sim-ply easier to let most of the copyrights lapse, although NewMonogram took advantage of the confusion by re-issuing anumber of old Monogram films well into the 1940s.

It is difficult to say for certain if all negatives and prints ofthese films are truly gone because of the intricate path of own-ership, which got even more complicated later. The earlyMonogram films that became part of the Republic holdingswere sold to Paramount when Republic sold off its assets. Thelater Monogram holdings became part of Allied Artists, whichbecame part of United Artists, which became part of MGM,which is now part of Columbia, which is part of Sony. If nega-tives or prints of the Stratton-Porter films survive in the corporatearchives of these studios, they have not yet been identified.

The studios have little interest in maintaining prints of thesefilms anyway, since the initial twenty-eight-year copyright periodbegan to expire in the early 1960s for most of Monogram’scatalog. As uncopyrighted works, the Monogram films are freeto be copied and shown by anyone. With preservation moneytight, studios will always opt first to preserve titles that theyclearly own. The downside of copyright expiration is that whenno one owns a title, no one wants to preserve it.

Fortunately, in the 1950s, with the burgeoning market fortelevision, Monogram made 16mm prints of all of its available

STRATTON-PORTER’S POPULAR

NOVELS WERE A NATURAL CHOICE

FOR MONOGRAM. THEY STRESSED

A LOVE OF NATURE AND WERE

GENERALLY CHARACTER DRIVEN,

ELIMINATING THE NEED FOR

EXPENSIVE SETS AND LARGE CASTS.

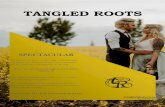

The four 16mm reels of Romance of the Limberlost and

A Girl of the Limberlost after being cleaned and repaired.

46 | T R A C E S | W i n t e r 2 0 0 7

L i m b e r l o s t F o u n d

films, even the older ones, for use on local stations. The majorstudios, fearing that overexposure on television would killthe value of their films, withheld their product from the mar-ket. Monogram, on the other hand, saw potential financialgain. Reprinting its catalog of twenty-year-old films was cheaperthan making new movies, and the old films had just aboutstopped making money in theatrical reissues. Records showthat all the Monogram Stratton-Porter films were made inthe 16mm syndication package for television. The originalnegatives and 35mm prints (the films shown in theaters) prob-ably do not survive today. Fortunately, there were definitely16mm prints on more durable triacetate safety film, the suc-cessor of the older, flammable nitrate film.

These 16mm prints are exactly the kind that were scoopedup by private collectors. Many films survive nowhere else butin the hands of a dedicated group of people who hoarded oldfilms simply because they loved them. Since the Monogramprints were made for only a brief window of time, approxi-mately between 1955 and 1960, they would likely be in thehands of older collectors who had worked at television sta-tions. The stations would have junked these old prints when thebig studios finally opened the floodgates of major titles, begin-ning about 1957 and continuing through the mid-1960s. No self-respecting station manager would want to run A Girl of theLimberlost when he could run Frankenstein for a similar price.

mazingly, the Monogram films have indeedbegun to surface in the private collector market,just as their history would predict. Several yearsago, a collector in Philadelphia rediscovered aprint of Keeper of the Bees (1935) and released it

on a small video label, although this title appears to be out ofprint at the moment, making the film’s quality difficult toreassess. The surviving film is one of the old distribution prints.

In 2004 an elderly collector from Syracuse, New York,decided to sell his 16mm print of the 1934 A Girl of theLimberlost, which he had rescued from the trash heap of atelevision station. Seen today, the film is a surprisingly livelystory that seldom betrays its low budget. Its director, W.Christy Cabanne, had been a director from about 1914 andfell on hard times with the advent of sound. The supportingcast consists of silent-era stars such as Henry B. Walthall,Betty Blythe, and Indiana native Louise Dresser. Particularlyoutstanding is the star, Marian Marsh, who projects inno-cence and vulnerability as Elnora. The surviving print is inrather good condition, despite having been spliced a numberof times and stored improperly in a metal tin for many years.

Additionally, a 16mm print of the 1938 Romance of the

Evansville native Louise Dresser tries to rescue her drowning husband

from a swamp in a scene from A Girl of the Limberlost.

Title plate for the 1934 film A Girl of the Limberlost.

Born in Acton, Indiana, Marjorie Main appeared in 1938’s Romance of

the Limberlost before going on to win fame playing Ma Kettle in a series

of popular movies during the 1940s and 1950s.

A

T R A C E S | W i n t e r 2 0 0 7 | 47

L i m b e r l o s t F o u n d

Limberlost appeared on eBay in mid-2003, from the estate ofa deceased collector. The film, however, contains a disap-pointing credit that it is “inspired” by the works of Stratton-Porter, although not based on any particular one. However,it certainly is true to the Hoosier author’s spirit, with typicalStratton-Porter touches in the form of a benefactor who col-lects butterflies, a nasty uncaring stepmother (played to thehilt by Hoosier Marjorie Main), and the sensitive young hero-ine. The director was the competent William Nigh, who hadbeen a top director at MGM. Nigh had worked with LonChaney on such top-flight features as Thunder (1929) beforeinexplicably being relegated to such horrible misfires as TheMysterious Mr. Wong (1935) a few years later. His directorial turnhere is a welcome return to the quality, if not the budget, ofhis earlier work. The print is in fairly good shape, with a fairamount of splicing due to careless projection and somewarpage due to poor storage. However, it has responded wellto some emergency repairs and can be projected once again.

There can be no doubt that A Girl of the Limberlost is the bet-ter of the two films. Made at a time when Monogram was relativelyflush with cash, Girl features a fair amount of real location footage,with nice outdoor sound work and convincing atmosphere.Romance is a decidedly cheaper film, made with interior sets oftenmasquerading as “the great outdoors,” but its makers effectivelyhid this by using phony exteriors as infrequently as possible.

Now that the films have been found again, how can theybe preserved? This is a complex question. Since no copy-rights apparently exist for these films, they can be copied atwill. However, proper preservation does not mean transfer-ring them to DVD or videotape. Modern video transfers arestill of inferior quality to the original film. The proper wayto preserve these films would be to copy them onto modern,stable motion picture film, a process that would cost sev-eral thousand dollars per title. Since these prints are onrelatively modern triacetate safety film, archives are, under-standably, not interested in spending a lot of money makingnew copies, even though these prints are decomposing. Thearchives are almost literally swamped with decaying nitratefilm that demands immediate copying or the images will belost forever. Unless these films can find a preservation spon-sor, we will have to be content with periodic theatrical show-ings in special venues around the state.

What other films might survive? A surprising numberof FBO films have surfaced in France and the formerYugoslavia. It is certainly possible that a mistranslatedcopy of one of the early Stratton-Porter films survives insome dusty European archive that has yet to properly iden-tify it. It is unclear whether the Republic Stratton-Porterfilms from the mid-1930s were in the same syndicationpackage as the Monogram titles. Republic’s long-lost ver-sion of The Lone Ranger (1937) turned up recently, so oth-ers might show up in private hands. A recent search ofthe Republic archives has turned up some interesting titles,including an incomplete print of Michael O’Halloran (1937),which is missing the picture elements for a ten-minute sec-tion of the film, although the sound survives. A specialscreening in March 2006 received lukewarm reviews.

The RKO titles, Laddie (1935) and Freckles (1935), proba-bly have the worst chance for survival. RKO’s films were notvery well preserved until Ted Turner took over the collec-tion in the 1980s, by which time many of the older titleshad already deteriorated. However, much of the RKO librarywas reprinted for television use in the mid-1950s by a labo-ratory in Mexico. The lab mistakenly printed a number oftitles that should not have been in the syndication package,including the legendary Val Lewton picture The Ghost Ship(1943). If the Stratton-Porter pictures accidentally wereprinted into the first television package, a few errant printsmay still be floating around waiting to be found.

Simple luck often uncovers lost films in garbage cans orother dark places where they have been hiding in obscu-rity for years. Their survival often depends on circumstancesso complex that lawyers make healthy careers out of unrav-eling them. Too often, motion picture history consists ofevents that conspire to destroy this art form, but there is stillthe occasional thrill in finding the most obscure of films.Happily, at least these Stratton-Porter-related films mayrediscover an appreciative audience someday, despite hav-ing lain unseen in rusty cans for decades.

Eric Grayson is an Indianapolis film historian and collector whospecializes in pre-1940 films. He can often be found scrounging forfilm in Dumpsters, scouring burned-out movie theaters, teachingfilm history, introducing classic films, and skinning his knucklesinside some broken projector in his basement.

FOR FURTHER READING Fernett, Gene. Poverty Row. Satellite Beach, FL: Coral Reef Publications, 1973. | ———. American Film Studios: An Historical

Encyclopedia. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1988. | Long, Judith Reick. Gene Stratton-Porter: Novelist and Naturalist. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1990.

| Okuda, Ted. The Monogram Checklist: The Films of Monogram Pictures Corporation, 1931–1952. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1987. | Tuska, Jon. The Vanishing

Legion: A History of Mascot Pictures, 1927–1935. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1982.