Torch [Spring 2005] - uvic.ca

Transcript of Torch [Spring 2005] - uvic.ca

PM40

0102

19

TORCHTH E U N IVERSITY OF VICTORIA ALUMN I MAGAZI N E SPRI NG 2005

The Doctors Are On Their Way

Medical education on campus

10

CONTENTS

8

PEOPLE

10 LETTER FROM PHUKETParadise was not supposed to be like this. Alumnus Mike Corbeil

sends an eyewitness account of the tragedy of the December 26

earthquake and tsunami.

AGI NG

14 HOW CAREGIVERS COPENew research examines the unheralded work of informal

caregivers: the family, friends or neighbours who help out the ailing

or elderly.

EDUCATION

18 THE DOCTORS ARE ON THEIR WAYThey are the first of a new class of student physicians. Five

exceptional young alumni begin their training in the Island

Medical Program.

FITN ESS

24 RACING AGAINST DIABETESCommunity health specialist Joan Wharf Higgins wanted to show

how recreation centres can play big roles in preventing diabetes.

She found proof in the pedometer.

YOUTH H EALTH

26 CATCHING DREAMSAdolescent girls, their health issues, and a voice of experience—

keys to a mentoring strategy created by Nursing Prof. Elizabeth

Banister.

2 SEVEN FLAMESEditor’s note

3 MAILBOX Readers write

6 RINGSIDE News from campus

28 BOOKMARKS Spring reading

29 KEEPING IN TOUCH Notes from classmates

30 ALUMNI NEWS People, programs and events

36 VOX ALUMNI Pierre Berton at Victoria College

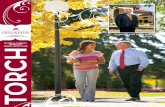

On the cover: Island Medical

Program students (standing, left to

right) David Harris, Steve Burgess,

Patrizia Moccia, with (seated, left

to right) Michelle Tousignant and

Averil Russell. Foreground: “Oscar”

the instructional skeleton.

Photo by Hélène Cyr.

TORCHSP

RIN

G 2

00

5

F E AT U R E S D E PA RTM E N TS

T H E U N I V E R S I T Y O F V I C T O R I A A L U M N I M A G A Z I N E

362418

Torch [Spring 2005] 4/23/05 11:19 AM Page 1

TSEVEN FLAMES | FROM THE EDITOR

Health-mindedTHIS MAGAZINE AND THIS COLUMN TAKE THEIR TITLES FROM THE TORCH AND SEVEN FLAMES—symbolizing learning—that appear above the university’s coat of arms, which alsoincludes the motto, “A multitude of the wise is the health of the world.”

When the coat of arms was selected in 1903 by the founders of Victoria Collegethey imagined great things for post-secondary education in Victoria. They may nothave been thinking of “health” in literal terms when they arrived at that Biblicalphrase, from The Wisdom of Solomon, as an expression of their ideals. Yet the mod-ern university is proving to be quite a direct reflection of a well-chosen motto.

You can find another, tangible symbol of the campus connection between healthand learning—and it’s only a short walk from the bright new Medical SciencesBuilding. On the southwest corner of the Quadrangle stands a mature plane tree. Itwas planted 35 years ago by Dr. Bill Gibson, the former chancellor and Victoria Col-lege grad, on behalf of the Victoria Medical Society to symbolize co-operationbetween the university and the region’s doctors. The seedling is said to have grownfrom a seed of the plane tree under which Hippocrates, the “Father of Medicine,”taught on the Greek island of Cos.

At no time have the ideals represented by our century-old motto or that tall, state-ly tree seemed more prophetic. At no time have the minds and energy of the univer-sity’s educators, researchers and students been so directly involved with the healthof their community. It’s alive in the students that are just starting their medicaltraining on campus, in research for the young and the aging, and in the promotionof healthy living.

The people in our series of health-related features are dedicated to the welfare ofothers. They lead inspiring lives of learning and inquiry driven by the passion forcaring. They remind us—in our wired (and wireless) world—of something higher toreach for, an agelessness at the heart of their efforts.

M I K E M C N E N E Y E D I TO R

Volume 26, Number 1 • Spring 2005

The UVic Torch Alumni Magazine is published biannually in the spring and autumnby the University of Victoria, Division of ExternalRelations and the UVic Alumni Association.

EDITORMike McNeney

ART DIRECTION AND PRODUCTIONClint Hutzulak, BA ’89Rayola Graphic Design

ADVERTISINGBonnie Light, BA ’[email protected]

ADDRESS UPDATES AND [email protected]

LETTERSAll correspondence to the editor will be consid-ered for publication and may be edited.

UVic Torch Alumni MagazinePO Box 3060Victoria, BC V8W 3R4Fax: 250.721-6265E-mail: [email protected]

The University of Victoria, established in 1963, is one of Canada’s leading universities, offeringstudents and faculty a unique learning environ-ment. It is recognized for its commitment toresearch, scholarship and experiential learningand for its outstanding social, cultural, artistic,environmental and athletic opportunities.

CHANCELLORRon Lou-Poy

PRESIDENT AND VICE-CHANCELLORDavid Turpin

VICE-PRESIDENT, ACADEMIC AND PROVOSTJamie Cassels

VICE-PRESIDENT RESEARCHMartin Taylor

VICE-PRESIDENT, FINANCE AND OPERATIONSJack Falk

VICE-PRESIDENT, EXTERNAL RELATIONSFaye Wightman

PRESIDENT, UVIC ALUMNI ASSOCIATIONDoug Johnson, BA ’77, LLB ’80

Publication Mail Agreement No. 40010219Return Undeliverable Canadian Addresses to:Advancement Services University of Victoria PO Box 3060 STN CSC Victoria BC V8W 3R4

Printed in Canada ISSN 1191-7032

THE UVIC TORCH ONLINEwww.uvic.ca/torch

TORCH

2 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 | U V I C TO R C H 3

P I C T U R E S TO L D T H E STO RY

I wanted to comment on the recent photo galleryof pictures with respect to the first day back inSeptember (“Day One,” Autumn 2004). Of all theother articles I’ve read since leaving, it was one ofthe best. It brought back some very familiar feel-ings (good, and anxious) with respect to my firstday back when I was attending UVic. Thanks forbringing back those memories.

R O B I N M I TC H E L L , B S C ’ 8 6C A L G A R Y

M O R E A B O UT T H E B O N E S

I kept “Bear Bones Evidence of Early Life” (Spring 2004) becauseI have an interest in such discoveries and because I wanted topursue it further with a grandson in Grade 9.

Having read “Setting the Bones Straight” (Autumn 2004) Ishould now ask my grandson to read the original item and thethree letters without comment from me, then ask him what hemakes of it all. I am a retired teacher. If I were still in the class-room I would present the above to my students to get theirresponses and opinions.

For me personally I am reminded that readers must be wary.Also for me Ms. Wigen’s omissions seem more than a lapse. Forone so close to research, her hazy memories surely should havebeen clarified before agreeing to the original item.

A N T H O N Y TA D E Y, P N S ’ 5 0N O R T H VA N C O U V E R

PA RT O F T H E PA R A D E

I was among students from “the castle” (Autumn2003) having enrolled in 1946 at the time thathundreds of ex-servicemen and women descend-ed on the college. I joined the hundreds in theparade that marched on the Parliament buildingsdemanding a larger campus, which we got—withthe Provincial Normal School at the Lansdownecampus.

I spent the next year there, leaving in 1948 tobecome a provincial civil servant until retirementin 1983.

Before moving to the Interior, I lived in GordonHead and saw the development of the university at the new site.I recently was through the area again, and it is now quite a sight.

R AY J E F F E R S O N , VC ’ 461 5 0 M I L E H O U S E

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

LETTERS: We always make room for your thoughts, opinions and reactions to these pages.

Send correspondence to:E-MAIL: [email protected]: (250) 721-6265PAPER: UVic Torch Alumni Magazine

PO Box 3060Victoria BC, V8W 3R4

MAILBOX

T

NEWS FROM CAMPUSRINGSIDE

6 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

We’re Expanding

Tech Park PurchasedThe university has acquired the Vancouver IslandTechnology Park, in Saanich, in a move that promis-es to create greater synergy among facultyresearchers, graduate students, co-op students,spin-off companies and established firms. Thefacility (on the site of the former Glendale Lodge)currently houses 23 companies employing 1,200people and the university has plans to add up tosix new buildings to the 14-hectare tech hub.

UVic is self-financing the $20.2-million transactionwith the BC Buildings Corporation, with no impacton the university’s operating budget. Among thepark’s tenants are MDS Metro medical labs, theGenome Proteomics Centre, and GenoLogics soft-ware, one of 35 companies that have been devel-oped from research generated at the university.

THERE’S A BUILDING BOOM ON CAMPUS. NEW CONSTRUCTION WILL HELP

the university cope with a space crunch from the growing pop-ulation of young people plus the province-wide shift from aresource-based to knowledge-based economy. Close to 2,000more full-time students will be at UVic by 2010. As a result, thecampus is about to undergo one of the most active buildingphases in its 42-year history. The new projects include:

• William C. Mearns Centre for Learning, a technologicallyadvanced extension of the McPherson Library. The project hasreceived a $5-million gift from the family of the late BillMearns, a Victoria College graduate and a force behind theplan to establish the university. UVic and the provincial gov-ernment matched the Mearns gift ($5-million each), withadditional private funding rounding out the project’s $20-mil-lion cost. The centre will be fully wired, and will include amulti-media centre, a round-the-clock study area and anInternet café. A completion date hasn’t been set.

• An 11,000-square-metre, $50-million science building to con-solidate the School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, along withspace for the Chemistry department.

• An 8,600-square-metre, $30-million social sciences/mathe-matics building will include four tiered lecture theatres andoffice space for the departments of Geography, EnvironmentalStudies, Political Science, and Mathematics and Statistics. Theprovince is contributing $60.4 million to the science and socialsciences/mathematics buildings with $20.5 cost to be raised byUVic. Completion of both buildings is scheduled for 2008.

Planning and fundraising are also underway for a $6.5-millionFirst Peoples House and a $14-million support services building.

President David Turpin said the expansion program means“better classrooms, better labs—in fact space that we could notpossibly have provided by rehabilitating older structures.”

3:55 pm, March 23. Construction crane operator Mario Daluz has the best view on campus. From 50metres above ground, he took these images—lookingwest, north and east—at the end of a shift at the siteof the new engineering and computer science structure.

Vision: The family of the late Bill Mearns(right), a universityfounder, is funding amajor extension of theMcPherson Library.

S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 | U V I C TO R C H 7

Masterful MarsalisTrumpeter Wynton Marsalis—jazz statesman and one of thegenre’s most prominent and controversial figures of the pasttwo decades—joined the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra (includ-ing bassist Carlos Henriquez) at the University Centre in Febru-ary. The big band’s sparkling performance was a presentationof the Victoria Jazz Society.

HÉ

LÈN

E C

YR

PH

OT

O

The Big BuildupFor geologists who try to understand the way the earth gen-erates its crust, Pito Deep, a submarine canyon near EasterIsland, exposes a phenomenal treasure of rock outcroppingsthat were key parts of the volcanic process of earth-building.

In February, Kathy Gillis—one such geologist (and thedirector of the School of Earth and Ocean Sciences)—joineda research voyage to Pito Deep led by Duke University’s JeffKarson.

The site is part of the East Pacific Rise, a mid-ocean ridgethat’s spreading at the geologically “super fast” rate of 144mm a year. A fortunate result of that speedy process is that inthe last three million years it has exposed the conduits thatbrought molten rock towards the sea floor. Normally thosegeologically important rocks would be embedded a kilome-tre or so below the floor.

Gillis and graduate student Kerri Heft sent back the aboveimage of one conduit, or sheeted dike. The photo includesan arm of the research submarine “Alvin” as it takes samples,about 3.6 km below the surface.

Hockey School

Beardsley: a national psyche defined by pucks, ice and “mayhem.”

HÉ

LÈN

E C

YR

PH

OT

O

WHEN WORD GOT OUT THAT ENGLISH INSTRUCTOR DOUG BEARDSLEY WAS

introducing a new course this spring—“Hockey Literature andthe Canadian Psyche”—the 40 seats in the class were quicklyreserved, ESPN offered to fly him to New York for an interview,and e-mail arrived from hockey fans and academics from as faraway as Texas and China.

“Because of the NHL lockout all of these people had vast, emptyspaces to fill with no games going on,” says Beardsley, a wonder-fully opinionated hockey nut. “They also think they can learnsomething about us as a nation by learning about the game,about the Canadian character. They’re right.”

Students in Beardsley’s class completed three research essaysconcentrating on the usual English studies terrain of imagery,symbolism or style, only in a hockey context. The reading listincluded classics like The Divine Ryans, by Wayne Johnston, TheGood Body by Bill Gaston and Les Canadiens by Rick Salutin.

They’re the sort of books that get at the true meaning of beingCanadian. By Beardsley’s definition, hockey represents a dark,Jungian counterbalance to the stereotype of the polite Canadian.“I think that along with this peace-sharing, gentle (image) comesa need for mayhem. So we invent this game and—whammo!—you get on the ice and it serves as a channel for those externalenergies that we don’t allow ourselves elsewhere.”

As for the sorry state of the professional game, Beardsley saysthe lost season “leaves an appalling abyss. I think we feel lostwithout the game. The reason the game needs to be played inwinter is that it is a metaphor for how to survive winter. It’s ourform of saying, look, even up here in the frozen north we canturn this around and make it work for us.

“I’m talking about something larger than what happens on theice, and so is the course.”

8 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

RINGSIDE | NEWS FROM CAMPUS

Alumni Survey Maps FutureTHE UVIC ALUMNI ASSOCIATION HAS COMPLETED ITS MOST EXTENSIVE SURVEY OF

members and is using the feedback to initiate plans to generate moreawareness and participation in the association’s programs and services.

The association contracted R.A. Malatest and Associates, a Victoria-basedmarket research company, to conduct a telephone survey and focus groupsessions. A total of 601 alumni participated in the survey in September. Fol-low up focus groups were held in Victoria, Nanaimo and Vancouver.

The survey questions ranged from the level of satisfaction with alumnicommunications to the likelihood of participating in alumni events, andthe level of interest in various services available to graduates.

Among the key findings, more than 70 per cent of respondents said theywere satisfied or very satisfied with communications, with the Torch beingthe most commonly read publication. The survey also asked alumnito rate their interest in topics contained in publications. Research,university news, continuing studies, alumni association news, andKeeping in Touch notes were the most popular choices.

Asked to rank their likelihood of attending different events, alumnichose as their top three picks: public lectures, reunions, and plays at thePhoenix Theatre.

In terms of services available to alumni, respondents most often chosetravel packages, special rates on home insurance, and the Alumni Bene-fits Card.

Alumni Services director Don Jones thanks survey and focus groupparticipants and says the information they’ve provided will define thefuture of alumni events, benefits, student programs and alumni services. “Oneof the things that has become clear from the survey is that a fair number ofalumni are asking for services that we already offer,” Jones says. “Our chal-lenge is to bring that information to them and, ultimately, to get more gradsinvolved with their university either as volunteers or as financial supporters.”

A benefits and services guide, Alumni Almanac is available from the alumnioffice (e-mail: [email protected]). And all alumni are welcome to attend theassociation’s Annual General Meeting on June 22 at the University Club.

No FearWhen Steve Canning—talented photog-rapher, writer, student and, above all,adventurer—died last spring frominjuries sustained in an accident on Mt.Logan he left a collection of fine photoslike this one. He also wrote that throughthe dangerous extremes of climbing,skiing or base jumping, he lived withoutfear of death and hoped others couldsee life the same way. A scholarship inhis name—boosted with more than$16,000 from a fundraising night thatdrew 300 people—has been created forstudents in the School of EnvironmentalStudies.

ST

EV

E C

AN

NIN

GP

HO

TO

The Daily DozenGuy Pilch, MA ’99, a counselling psychologist andfounder of Train the Brain Consulting, offers thesebasic tips for keeping the mind at its sharpest. Pilch,with the UVic Centre on Aging, presents workshopson maintaining brain power.

1 Get a good night’s sleep.2 Eat a well-balanced, nutritious diet.3 Maintain a positive outlook.4 Control blood pressure and cholesterol.5 Set goals and stretch yourself (without

unrealistic expectations).6 Learn to control stress.

7 Manage your moods.Depression, anxiety, and panicaffect brain performance.8 Find someone caring to confide in.9 Regular exercise has goodmental as well as physical benefits.10 Develop a spiritual practice.Research shows that the mentalhealth effects of prayer and medi-tation are comparably beneficial.11 Avoid health hazards. A glass of

wine a day may have health benefits for somepeople; more than that will not help anyone’sbrain functioning. Most drugs of abuse are veryharmful to long term mental fitness.

12 Participate in brain stimulating activities likedancing, playing bridge or doing crosswords.

www.trainthebrainconsulting.com

MA

RK

ST

RO

ZIE

R P

HO

TO

“

”

RESEARCH

S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 | U V I C TO R C H 9

Quotable

I was good at math and physics. Ilike numbers and I like science.And I also like to feel I can dosomething that will benefit thecommunity.

Most people kind of assume thatresearch won’t be informed bywhat’s happening in the realworld. From a researcher’s pointof view that can be quite frus-trating. I like to think that every-thing I’ve tried to do has been toeither improve clinical responseor, more recently, policyresponses.

In Australia, brewers, distillersand winemakers are still able tosell incredibly cheap (products).Among their main customers areimpoverished Aboriginal peoplewho then waste themselves. It’sstraightforward government pol-icy. I saw our role to do researchwhich shed light on it, raised theissue for public debate and triedto encourage better outcomes.

It seems extraordinary in BC thatthere’s a mayor in Vancouver who was actually voted in on aharm reduction ticket. I mean, I’ve never heard of this happen-ing anywhere in the world. There’s a lot of progressive thinkingand a feeling that new things can happen. That’s been con-firmed since I’ve been here.

I think our job as an independent research unit is to hold up amirror to the community to say, Well actually if you look across

the whole province these aresome of the things that perhapsyou’re not aware of. Yes, you’reconcerned about violence, roadcrashes, young people dying.This is what we know works andthis is what you can do about it(through) prevention and pro-moting evidence-based pro-grams.

Really, the way you get change isto make sure there’s awarenessacross the whole community. Ithink we have to communicateat all different levels. If we canset up something which is con-tinually informing the politicalprocess and community aware-ness, as well as being trusted andused, that would be fantastic.

I like wine, I like beer and I occa-sionally drink spirits. I would liketo believe it’s good for you butone of my research areas is ques-tioning health benefits or theextent of them. I think there arebenefits but there are a lot ofexaggerated estimates of the

benefits. The ways we normally use alcohol aren’t conducive togetting any benefit at all. You have to drink just a little bit andoften, rather than once or twice a week drinking quite a lot,which is the way most people drink alcohol. T

Tim Stockwell is co-editor of Preventing Harmful Substance Abuse, published

this spring by John Wiley and Sons. The Centre for Addictions Research of BC is

online at www.carbc.uvic.ca.

Tim Stockwell came to the university last year, joiningthe new Centre for Addictions Research of BC as itsdirector. A professor of psychology, Stockwell’sresearch interests lie in alcohol policy and drinking pat-terns and their consequences. He was born and edu-cated in London, England and early in his career, work-

ing at a drug addiction unit, he was active in a publicbattle to save the facility from Thatcher governmentcuts. Since then he’s never been shy about widely com-municating the findings of solid research, most recent-ly as head of Australia’s National Drug Research Insti-tute. Here are excerpts from a recent conversation.

DO

N P

IER

CE

/UV

IC P

HO

TO

SE

RV

ICE

S

Dealing with addictions: Stockwell is leading researchthat will “hold up a mirror to the community.”

10 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

PEOPLE

Letter from PhuketMike Corbeil, BSW ’79, and his wife Cindy are former

Victoria residents living on Phuket Island in Thailand.

Safe from the worst of the December 26 earthquake

and tsunami, Mike worked in the aftermath of the

devastation to help survivors locate the missing. This is his account of

an exhausting, heartbreaking ordeal.

P H OTO G R A P H Y B Y D E D D E D A S T E M L E R

CIN

DY

CO

RB

EIL

PH

OT

O

S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 | U V I C TO R C H 11

DECEMBER 26. AFTER A LATE NIGHT CELEBRATING

Christmas with friends, I noticed my sofashaking slightly. Was it an effect of the party orjust my imagination? A second shake joltedthe house and I knew it was an earthquake.That got the heart pumping.

I didn’t think any more of it and at 10:00 a.m.we started making our Christmas calls to fam-ily in Victoria. I didn’t know that the firsttsunami wave was hitting the beach about twokilometres from our house. About an hourlater, my friend German Mike came to ourhouse, very shaken and having a hard timedescribing what he had just seen. At KataBeach he had been unable to get through thechaos on the streets. People were receivingCPR, there was debris on the roads and vehi-cles were strewn about like matchsticks.

We immediately went to Nai Harn beach,where we spend a great deal of time, to checkwhat was going on. A nearby lake was full offloating beach chairs and very muddy, murkywater. Uprooted trees blocked parts of theroad. I found a Thai friend who ran the beachchair concession. He was in shock. Hedescribed how the water had suddenly gone

way out into the bay and then “just came up”—not a big wave,just a huge volume of rushing water.

We went about 150 metres down to the north end of thebeach. People started to look anxious as a murmur rolledthrough the crowd that “it’s coming again.” The sea water wasdrawing out into the bay and we all ran from the beach to high-er ground. There was a large surge of water, not a wave thatcaused damage but quite impressive.

Mike and I headed up to a lookout where you could see thebeaches of Kata and Karon. The tidal action was very odd. Thewaves weren’t rolling in and out like they normally do—theykept lapping up to the shoreline. A British friend came up to thelookout after hearing on the radio that a large wave would behitting at 1:00 p.m. Others had heard that a 50-metre wave wason its way. People, worried, scanned the horizon.

I realized I had about an hour to get home, put together a sur-vival kit, pick up my wife Cindy and head back to the safety ofthe lookout. We packed and returned to find hundreds morecrowding the hill. News came that the next big wave was notcoming until 3:00 p.m. Then at 5:00 p.m., when it hadn’t materi-

alized, we were told to go home. I was able to send an e-mail tofamily members and friends to let them know we were safe.

December 27. I had heard about a relief centre at the provincialhall in Phuket town. There were tents with tables and signs indi-cating different countries. At the table with a “Canada” sign,Thai volunteers gave me forms to register missing people andforms to document people who needed passports. They showedme where the Thai immigration staff was fingerprinting andphotographing people so they could replace lost travel docu-ments and arrange transportation home.

I went to the Canadian Embassy area, and met AmbassadorDenis Comeau, his military attaché and three Thai staff from theembassy in Bangkok. I can’t stress strongly enough how great theambassador was under the circumstances. The area was bustlingwith embassy staff from at least 30 countries. Helicopters arrivedwith hundreds of survivors from around the region. Thailand’swell-organized equivalent of Girl Guides and Boy Scouts were intheir uniforms helping to dispense truck loads of water. Volun-teers at food stalls fed victims and volunteers.

Bulletin boards held hundreds of photos of the missing and theunidentified dead. It was startling to see so many people, somany children. Some were badly battered from the debris in thewater, but most looked peaceful, as if sleeping. That was the firstday of photos. The next and subsequent days brought more andmore images of the dead, indescribable and unrecognizable.

December 28. I went to the naval port to meet boats coming toPhuket Harbour from Phi Phi Island carrying survivors and 400bodies of the dead. A temporary morgue was set up for family

Victoria Times Colonist photojournalist Deddeda Stemler captured these images of the tsunami’sdamage in Phuket 24 hours after the first waves. Emergency personnel (below) carry a body thatwas trapped inside a travel agency building on the main road along Patong Beach. Left, crews pumpwater from the flooded main floor lobby of the Seapearl Resort.

12 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

PEOPLE

members waiting to identify loved ones. A German man waitedto identify his nine-year-old daughter and his mother. They hadbeen together on Phi Phi, along with his wife and 12-year-oldson. As the ferry approached to take them to Phuket, he askedhis wife to go and get water for the trip. She went with his moth-er and daughter to the port area stores. As he waited in line withhis son he saw the sea retreat and the waves suddenly approach.He ran with his son to higher ground. Afterwards he found hiswife in shock. His mother had been swept away. Their daughterhad been torn from his wife’s arms, screaming, dragged awaywith the debris. He was so strong in his resolve to identify hismother and daughter, so composed and determined.

December 31. I had received a phone call from the Canadianambassador asking if I would go to Krabi town with anotherCanadian, Greg Jones, to look for Canadian passports. The sisterof a missing Canadian girl gave me a description of her tattoosand photos. Another woman gave me a photo of her missinghusband and described the burn scar on his stomach.

At the Krabi immigration office we found a pile of wet, sandypassports including five belonging to Canadians. Inside amakeshift morgue, trucks were arriving with more bodies. Itwas five days later and there was no refrigeration. Having seenthe photos of the recent arrivals I knew there was no point intrying to look for identifying marks, nor did I feel I had thestrength to do the job.

We recorded passport numbers, dates of birth, and names andsaw the faces of so many young people as we wiped sand fromtheir photos.

It was late, dark and New Year’s Eve.

•

WEEKS LATER THINGS SEEMED ALMOST BACK TO NORMAL. BEACH CHAIRS

reappeared Feb. 1. All of the clean up on Phuket was done andrebuilding was underway. Our beach chair vendor, Nui, whoused to have 100 chairs, was allowed 20. Maybe the governmentwould let him have more in the future but for now he wouldn’tneed them: there were no tourists. The streets of Phuket’s beachtowns were quiet. It’ll be tough if the tourists stay away.

Cindy, who teaches English at a Thai government school,helped students cope with grief and loss. One girl who lost herolder sister didn’t know how to console her grieving parents.Another little girl, about 12, didn’t show up to school for the firstweek. Her family lost everything. She was embarrassed to go toschool because she didn’t have an iron for her uniform.

For all of us the tears come easily. You think it is behind you,and then something reminds you of the sadness. You feel guiltybecause nothing happened to you and so much happened toothers. You wonder how, over the course of time, they will dealwith this. T

14 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

AGING

SETTLED INTO A GREEN LEATHER RECLINER, 82-YEAR-OLD RICHARD

Bunbury looks almost as cozy as the butterscotch cockerspaniel sprawled on his raised legs. Several other long-termcare residents at the Oak Bay Kiwanis care facility sit on over-stuffed chairs or shuffle around the bright sitting area andadjoining sunroom.

As his wife Elaine sits in the loveseat next to him, Richardclutches a yellow ball with blue stars close to his chest. His fin-gers pulse at it like a heartbeat. Seeing a new visitor, the dogwags its tail and tries to stand. As I squat to make friends,Richard launches the soft ball at me. Elaine, a petite 76-year-oldwoman with neatly curled sandy blonde hair, immediatelyapologizes as I catch the ball, laugh and give it back to Richard.

“I throw the ball to him every day,” she explains. “It helps keephim alert.”

Richard murmurs and throws the ball into the middle of theroom. A thin woman perched next to Elaine watches it roll intoa corner.

“He’s lost words,” says Elaine. “But he still has quite a sense ofhumour, as you can see. Once I got really frustrated with him fornot being able to talk and said, ‘Say something!’ He looked rightat me and said, ‘Something.’ ”

Her silver bangles jingle as she clasps Richard’s hand. He looksat her, slightly puzzled.

It’s been just over a year since Elaine moved Richard, who hasAlzheimer’s, into long-term care. For 11 years before that, shelooked after him at home. As his condition progressed the levelof care he needed increased. “It became very difficult,” she says.“He refused to undress, swallow his medication, and get out ofthe tub. Once when he refused to get out of the tub, I turned onthe cold water—that got him out.”

Three mornings a week, home care workers helped Elainebathe Richard, and the couple’s daughter came over every nightto help put her father to bed. When he was still capable, Richardattended a day program so he could socialize and Elaine couldcatch a break.

“I wouldn’t have coped as long as I did without that assistance,especially the day program,” she says. “Some people find talk-ing helps, but listening to other people’s stories pulled medown. It was enough to cope with what I had. I had to keepthinking positively. I’ve always believed you have to overcome.”

BARBARA WARMAN, 55, RESTS HER NUMB LEG ON A CUSHIONED

ottoman. Two dogs and four of her seven cats curl up near her.The apartment is warm and smells of bread from the bakery onthe ground floor.

A seasoned informal caregiver, Barbara provides care to herhusband, who has rheumatoid arthritis, and to her 90-year-oldblind mother, who lives down the hall. Barbara also has multiplesclerosis. But it doesn’t seem to impede or complicate her care-giving. “Caregiving gives MS something to take second place to.”

Over the past 15 years, Barbara’s also cared for her dyingfather, four aging aunts and uncles with varying degrees ofdementia, and she’s provided respite care for a cousin’s wife.

Like most caregivers, Barbara tailors her caregiving duties foreach recipient’s need and level of independence, which canchange over time and from day-to-day. Sometimes caregivingmeans laundry, grocery shopping, helping with finances, driving,coordinating home support or providing meals. Other times, itinvolves more intimate challenges, such as bathing or toileting.

Barbara spoke about her experiences at a forum on intergen-erational relationships. Jaws dropped as she cheerfully sharedstories—like the one about bra shopping with her mother and

How CaregiversCopeOur aging population will grow to depend on the informal care of family,

friends or neighbours. The job is rewarding and demanding and it can be

overwhelming. Caregivers who cope (and there are lots of them) are helping

the UVic Centre on Aging help caregivers who don’t handle the role so well.

S TO R Y A N D P H OTO G R A P H Y B Y H O L LY PAT T I S O N , B FA ’ 0 5

S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 | U V I C TO R C H 15

elderly aunt where the aunt with dementia went one way, herblind mother went the other and Barbara, who was using awalker for her MS, tried to round them up without anyone get-ting injured or lost.

When asked how she copes, Barb’s brown eyes grow wide andher eyebrows rise in a startled expression. “I don’t know,” shefinally says, “you just do it.”

A TEAM OF UVIC RESEARCHERS IS ALSO SEARCHing for answers to thatquestion. It’s the focus of a soon-to-be completed study by theuniversity’s Centre on Aging. The study, “Caregiving: Why SomeCope Well,” funded by the Social Sciences and HumanitiesResearch Council, digs into informal caregiving—unpaid care—by talking to the family, friends, and in some cases, neighbourswho provide physical and emotional support to others.

The three-year project involves 91 infor-mal caregivers who help seniors living athome in Greater Victoria, Duncan andNanaimo. Caregivers were interviewed atthe beginning of the study with a follow-up session one year later.

“It was hard to get them in,” says sociolo-gist and principal investigator NeenaChappell, “but once they were here it waslike turning on a tap. People don’t usuallyask about the caregiver. Even when thereare people around, the focus tends to beon the care recipient.”

Chappell, who holds the Canada ResearchChair in Social Gerontology, says the studyfocuses on the positive aspects of caregiv-ing. Existing research tends to concentrateon the stresses and burdens, which createsa bias and draws a picture of burnout. Butin her 1995 report, “Informal Caregivers toAdults in British Columbia,” Chappellfound that most informal caregivers—91per cent—feel they manage well.

“All caregivers talk about the stresses andstrains,” says Chappell, “But most say, ‘I’mcoping very well, thank you very much.’ Theymay get overwhelmed, but they still want tokeep caregiving. So, what can we learn aboutcaregivers coping well under demand to helpthose who don’t cope as well?”

In the current study, researchers exam-ined coping skills in four categories: bur-den, stress, self-esteem and life satisfaction.Coping was measured in terms of problem-focussed and emotional-focussed coping.Problem-focussed coping, says Chappell,includes taking assertive action or seekinginformation to solve problems. Emotion-focussed coping usually involves detach-ment, denial or unhealthy behaviours—

actions aimed at escape over solution. “Results are still preliminary,” says Chappell. “But the

strongest factors suggest psychological characteristics influ-ence how well caregivers cope and who is most at risk. I didn’texpect the psychological factors to be as strong.”

Resilience and neuroticism were the two distinguishing fac-tors—caregivers low in resilience or high in neuroticism had themost trouble coping.

Chappell says resilient people depend on themselves, takethings in stride and see themselves as being able to handle diffi-cult times. Neurotic people, she says, tend to be anxious, self-conscious, hostile, worrying and self-pitying.

“There are two avenues of help,” says Chappell. “We can bringin system help, which can give caregivers a break and helpreduce their hours, and we can teach them how to cope. Maybe

Elaine Bunbury with her husband of 55 years, Richard: “I had to keep thinking posi-tively. I’ve always believed you have to overcome.” Inset: Social gerontologist NeenaChappell: research suggests psychology influences the way caregivers cope.

16 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

AGING

you can’t teach someone who’s neurotic to not be neurotic, butthe data suggest we can teach people positive coping methods.”

There are roughly 56,000 caregivers in the Capital Region andover 3.7 million across Canada. And there’s plenty of companycoming. According to Statistics Canada projections, the propor-tion of seniors in Canada will grow from 12 per cent of the pop-ulation in 2001 to more than 20 per cent by 2026. It’s likely thatmany of those seniors will rely on informal care.

“The nature of caregiving involves change,” says Chappell,looking ahead to the next steps in her research. “We’ll be exam-ining whether people who were coping well during the firstinterview were still coping when the second was conducted. Ifnot, why not? Has there been a change?”

Change came for Elaine Bunbury when full-time caregivingfinally became too physically demanding and aggravated herown health problems—a slipped disc, a hernia and a history ofheart trouble. But moving Richard into long-term care wasn’teasy. “I didn’t want him to come here. This is a wonderful place,but I was afraid he’d go down. So far, he hasn’t.” She reachesover to adjust the headphones that have slipped off Richard’sears, releasing a tinny chorus of a Benny Goodman song.Richard doesn’t seem to notice. From behind wire-rimmedglasses, his gaze drifts across the room. “We’ve been married 55years,” says Elaine. “I wouldn’t want him to think I dumped him.They tell me he’s not capable of thinking that, but I still worry.What must he think?”

Long-term care eased the physical load, but there’s no ques-tion Elaine continues to be a vital caregiver to her husband. For

a few hours each day, she interacts with Richard in ways shebelieves will stimulate his mind and, she hopes, slowAlzheimer’s progression.

“I’m afraid to not come every day,” she says. “I don’t want himto forget me.”

She peels a banana and puts it into his hand. “I read him stories—his stories,” she says. A published author

herself, Elaine reads Richard her written versions of his “notori-ous” oral war stories.

“Richard’s the storyteller,” she says. “I’m never quite sure I’vegotten his words right. But then he’ll say, ‘That’s right. That’show it happened.’ ”

Richard tries to speak, but can’t get the words out. Elaine leansover the arm of his chair and says, “What is it you want to say,Richard? Is it my name?” She repeats, “What’s my name?” a fewtimes. The jewelled chain draping from her glasses glints in thelate afternoon sun.

Richard’s mouth opens and closes but he doesn’t answer. As the moment hangs, I start to feel like an intruder and won-

der if I should retrieve the forgotten yellow ball in the corner.But I can’t turn away. Then Elaine winks at me.

“You know it, don’t you?” she says to Richard. “You know myname, but you won’t tell me. You devil,” she teases. Elainesqueezes his hand and playfully rolls her eyes. Richard’s cheeksgrow round as he gives her a huge grin. T

Holly Pattison graduates in June from the UVic Writing program.

“People don’t usually ask about the caregiver. Even whenthere are people around, the focus tends to be on the carerecipient.”

18 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

EDUCATION

IT WAS A MEMORABLE SATURDAY IN JUNE LAST YEAR AS PATRIZIA Moc-cia’s friends and family gathered to celebrate her marriage toher long-time sweetheart. In the midst of the festivities, thebest man rose to make his toast to the bride, an accom-plished 25-year-old who had graduated with distinction in2002 from the university’s psychology department. The bestman also made an important announcement. Moccia hadlearned just days earlier that she would be among the first 24students in the Island Medical Program at the University ofVictoria, part of the University of British Columbia’s newlyexpanded medical school. “A gasp went up from the guestsand after that everyone was congratulating me on gettinginto medical school more than my wedding,” laughs Moccia.

Well of course. As wonderful as marriages are, they’re rathercommon. But getting into medical school these days—that’sreally something. For every seat available in a first-year medicalprogram in Canada, six or more students apply, almost all ofthem with excellent credentials. Some 1,315 hopefuls vied forUBC’s 200 available spots last year. But high marks and the rightprerequisites aren’t enough to secure a place. Now, successfulmedical school applicants must outshine others in a wide rangeof criteria: volunteering, extracurricular activities, communica-tion skills, civic engagement, empathy, leadership and more.

Five young UVic alumni had what it takes to nab one of thecoveted seats in the IMP. Joining Moccia in the class of 2008 are:Michelle Tousignant, BSc ’03; Averil Russell, BA ’04; SteveBurgess, BSc ’03; and David Harris, BSc ’03.

The Doctors AreOn Their WayFive young alumni are among the first generation of doctors in training

with the new Island Medical Program. The next four years will challenge

each of their exceptional abilities.

BY A N N E M U L L E N SF E AT U R E P H OTO G R A P H Y B Y H É L È N E C Y R

S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 | U V I C TO R C H 19S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 | U V I C TO R C H 19

Trailblazers: Five alumni are among the first class of24 students in the Island Medical Program. They are(from the left): Patrizia Moccia, Michelle Tousignant,Averil Russell, David Harris and Steve Burgess.

20 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

EDUCATION

The students are part of an historic milestone for medicaleducation in Canada. For the first time, one medical school’sprogram is being offered on three campuses: UBC, UVic, andUniversity of Northern BC in Prince George. They follow thesame curriculum and take part in lectures delivered by video-conference link-ups.

The distributed model expands the capacity for medicalschool seats across the province and aims to bring more diversestudents into the mix, particularly those who may be interestedin practising in small towns or remote, rural areas of theprovince. Studies show that doctors tend to practice near theplaces they’re trained. The research seems to hold true for these

five UVic alumni. Not only are they delighted that a new pro-gram enables them to earn a medical degree on a campus theylove, all express hope that their medical careers will eventuallysee them practising on Vancouver Island—either as family doc-tors or specialists.

DR. OSCAR CASIRO, THE HEAD OF THE IMP, NOTES THAT THE NEW

approach is part of a dramatic shift in how the curriculum istaught and in the type of applicants selected to form the nextgeneration of doctors. Individuals with stellar academic recordsalone will have a hard time getting through the interviewprocess if they don’t come across as personable, caring, andcompassionate individuals with exceptional communicationskills. “We really have a patient-centred approach,” says Casiro.

“At the heart of our selection is the question: would I want thisperson to be my doctor?”

With that guiding principle, it’s no surprise to find that thisfirst crop of IMP students in the shiny labs and interactive lec-ture halls of UVic’s new $12-million Medical Sciences Buildingare about the warmest, most accomplished and well-roundedpeople you’re likely to meet at one place and one time.

“Everybody seems to play the piano—and I don’t mean dab-bling, but really well,” quips David Harris, 24, who has Grade 8conservatory piano and has been chosen vice-president of the2008 IMP class. His extracurricular activities over the years areastonishing. He’s acted in musical theatre, coaches 13-year-old

boys in soccer, volunteers at Queen Alexandra Hospital, and is aprovincially-ranked badminton player. He’s no academic sloucheither, graduating with distinction in biochemistry and micro-biology.

Harris co-authored a peer-reviewed paper on T-cell immunol-ogy during undergraduate co-op work terms and credits thoseexperiences for his drive and desire to be a doctor. Working inlabs in the faculty of medicine at UBC he saw “how hard thesebrilliant people worked—they were really passionate. It taughtme to be accountable, to really work hard and to care aboutwhat I was doing.”

The desire to make a meaningful contribution and to care forothers seems to be a central characteristic of the five UVicalumni and their IMP colleagues. UVic kinesiology programgraduate Michelle Tousignant, 25, fits that description. The

Linked up: The main lecture theatre of the Medical Sciences Building includes video links so that students at UBC and UNBC can share lectures. The automated camera (right) follows the lecturer’s movements from signals received from weight-sensitive flooring.

“At the heart of our selection process is the question:would I want this person to be my doctor?”

S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 | U V I C TO R C H 21

daughter of a senior Canadian military officer once visited herfather in Rwanda where he was the force commander of the UNAssistance Mission, replacing General Romeo Dallaire. Shespent time with the orphans of the genocide and saw therefugee camps.

“It made such a lasting impression on me. It made me realize Iwanted a skill that would make me useful in a crisis and that’swhen I started thinking about becoming a doctor,” says the ath-letic Tousignant, who came to UVic to be near her grandparentsand to join the varsity rowing team. Her rowing, however, wassidelined by her grandmother’s sudden illness. Tousignanthelped nurse her until her death. Her desire to enter medicalschool was fuelled again in 1999 when she went to work in ruralhealth clinics in Honduras assisting with vaccinations andbirths. Following her kinesiology studies, she worked as anaquatic therapist at the Saanich Commonwealth Pool, helpingpeople regain movement and strength following heart attacks,strokes, car crashes and other traumas.

“It was not a linear path to medical school but the whole time,since I was 14, I just couldn’t shake the idea of becoming a doc-tor,” says Tousignant.

Steve Burgess’ desire to be a doctor was fueled by a personal,life-changing experience. Burgess, 23, was born with a portwine birthmark on the left side of his face. He was often teasedin elementary school. “An amazing physician made such a dif-ference in my life,” said Burgess who at age 12 began laser treat-ments with Dr. Harvey Lui, a Vancouver dermatologist.

Burgess had some 22 laser treatments spanning six years—unprecedented at the time. The painful therapy successfullyremoved almost all signs of the purple discoloration. It also ledto an enduring desire to become a dermatologist.

Like Tousignant, however, Burgess didn’t follow a direct pathto his calling. He did his undergraduate degree in biology at

UVic, specializing in genetics and cell biology. In his final yearand after graduation he conducted research in the genetics ofthe fungus that causes Dutch Elm disease.

Even with that impressive record, Burgess didn’t get into med-ical school the first year he applied, missing an interview byonly half a point. “I had many of the skills and experiences theywere looking for but I didn’t know that I should detail them inthe application, for example, telling them that I donate bloodregularly. That in itself was worth a point.”

Harris had a similar experience. He, too, took two tries to getinto medical school, despite having most of the qualities theywere looking for the first time. “Writing a good application is askill in itself,” he says, as Burgess nods in agreement.

Having so many skills, interests and aptitudes requires excep-tional multi-tasking and time-management skills—exactly theskills needed in a highly demanding medical program. Mostdays start at 8 a.m. and the students are on the go often untillate at night. Time is spent each week in videoconference lec-tures with colleagues at the other two sites, in small grouplearning sessions, and labs. They work one afternoon in theoffices of local family doctors in Victoria and one afternoon atRoyal Jubilee Hospital learning basic clinical skills, such as tak-ing blood pressure and giving an injection.

THE NEXT FOUR YEARS WILL CHALLENGE ALL OF THEIR EXCEPTIONAL abili-ties—requiring them to absorb vast medical knowledge that israpidly evolving. They will be working in smaller and isolated com-munities throughout Vancouver Island to get a taste of medicineaway from a big urban centre. They will have clinical clerkshiprotations through the specialties of anesthesia, dermatology, emer-gency medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology,orthopaedics, ophthalmology, pediatrics, psychiatry and surgery.Through it all, they will acquire the hands-on skills and knowledge

Sustainable: The medical building was designed to meet the energy-saving criteria of LEED—the Leadership in Energy and EnvironmentalDesign program. Labs like the one on the left are flooded with natural lighting, recycled building materials were used, and the building isequipped with low-flow water fixtures.

UV

IC P

HO

TO

SE

RV

ICE

S

to join the ranks of today’s medicalhealers.

“It is a really demanding program,but it is also really fascinating,” saysAveril Russell, 24. Unlike the otherfour UVic grads, she didn’t get a sci-ence degree, opting for anthropolo-gy instead. It’s a route she feels hasprepared her just as well. “Anthro-pology is all about the study of peo-ple, their physical characteristics, their societies and relation-ships. I think it is a great primer for medicine, because medicineis all about people too, particularly the situations or societal dis-parities that cause disease.” Russell did her honours researchproject on HIV infection in South Africa, gaining knowledgeabout AIDS that she’s already putting to use this year.

One of the key features of UBC’s medical education is calledProblem-Based Learning (PBL). It’s a narrative, group approachto assimilating the knowledge to recognize and treat a hugearray of diseases. Each Monday morning, students are providedwith the symptoms and medical history of a patient. Over the

week and working in teams, the stu-dents unravel the mystery behindthe illness—learning the differentialdiagnosis, the way to administerand evaluate medical tests, and thetypes of therapies available. It’s likethe real world of medicine whereteams of health professionals deliv-er care for patients.

For the observer, what is mostremarkable about this first group of students in the Island Med-ical Program is their congenial and co-operative nature. Any traceof the fierce application process is gone. The atmosphere is decid-edly collegial. Patrizia Moccia, the newlywed, recalls the very firstdays of classes when her professors specifically made the pointthat while it was tough to get into medical school, now they wereall colleagues. “The only thing that matters now is that, at the endof our training, we all emerge as good doctors.” T

Anne Mullens is a Victoria-based writer specializing in heath issues.

22 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

EDUCATION

UV

IC P

HO

TO

SE

RV

ICE

S

Lab technician Kurt McBurneydemonstrates an overhead videoprojector. Medical students can eitherview the demonstration on large, flatscreen monitors (upper part of photo)or at smaller monitors at their labtables.

24 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

FITNESS

ODELIA SMITH HAS COVERED A LOT OF GROUND—WALKING FROM VICTORIA

to the village of Tlatlasikwala on Vancouver Island’s northern tipand back—without going far from home. She did it in a four-week virtual foot race with fellow students and teachers from theSaanich Indian School Board’s Adult Education Centre. Equippedwith pedometers they recorded daily steps and mapped their

progress. By the end, they not only reached their 460-kilometregoal but far surpassed it.

For Smith, a 29-year-old member of the Tsartlip First Nation,those were the first steps on a journey toward healthier eating,improved fitness and the loss of 91 kilograms. “I woke up. I real-

Racing AgainstDiabetesResearch at the grassroots level shows how—one step at a time—community

recreation and health promotion can help to prevent diabetes where the risk

is highest.

BY J E N N I F E R B LY T H , BA ’ 9 5P H OTO G R A P H Y B Y H É L È N E C Y R

Prof. Joan Wharf Higgins, MA ’87, and diabetesprevention program coordinator Tara Taggart,BA ’02: rec centres and health promotion can“reduce the burden on health care.”

S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 | U V I C TO R C H 25

ized what I was doing to myself. (Now) I walk every day and I eatfruits and vegetables every day. It’s an awesome feeling.”

Getting people moving was a goal of the four-year SaanichPeninsula Diabetes Prevention Project, led by the university’sSchool of Physical Education and supported by Health Canada.The study, concluded this spring, explored community recre-ation’s role in controlling Type 2 diabetes among higher-riskgroups: single parents and low-income families, seniors, peoplewith disabilities, and Aboriginal communities (where Type 2diabetes occurs three to five times more per capita than in thegeneral population).

More than two million Canadians have diabetes, with threemillion cases expected by the end of the decade. Among thosewith diabetes, 90 per cent have Type 2 (occuring when the bodycan’t properly use the insulin it produces). The disease can bedelayed or prevented by maintaining a healthy body weightthrough fitness and nutrition.

“The anticipated number of people who will be living withType 2 diabetes is really astronomical,” says Joan Wharf Higgins,professor and holder of the Canada Research Chair in Healthand Society. “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,so how can we curb the epidemic at the local level, in the com-munity?”

The first two years of the study were largely spent with com-munity organizations, identifying issues. Given the size of theSaanich Peninsula, transportation—its availability and cost—was seen as a key impediment to fitness participation. Otherconcerns involved time, cost, and a sense of intimidation if onewasn’t already athletic.

TWO MAJOR INITIATIVES CAME FROM THAT ASSESSMENT: THE ABORIGINAL

Walking Programs and A Taste of Healthy Living, a series ofeight-week sessions promoting fitness and nutrition. Otherprograms included a nutrition newsletter for food bank clients,cooking classes, and a Web site (healthypeninsula.ca).

A key partner was Panorama Recreation, which offers swim-ming, skating, racquet sports, fitness classes, and wellness pro-grams for all ages. Still, some were unaware of the centre; othershad misconceptions about its programs.

One solution was to base the Taste of Healthy Living programsand a health fair at Panorama (the Aboriginal Sport Develop-ment Centre hosted a second fair). Single parents or seniorsfeeling isolated in the community were introduced to new peo-ple and new opportunities. “Isolation breeds isolation,” WharfHiggins observes, “so if you can somehow put a crack in that bywhatever means, it really is the first step.”

Part of it, too, adds program coordinator Tara Taggart, BA ’02,was about “allowing people a comfortable and supportive envi-ronment to try something new that they may not have had theopportunity to try.”

Kit Brodsky joined the Taste of Healthy Living program tolearn the importance of exercise and healthy eating in prevent-ing Type 2 diabetes. Now, with two sessions under her belt,Brodsky is a program facilitator and has lowered her bloodsugar levels, blood pressure, and her LDL or “bad” cholesterol—

all without medication. She also dropped 30 pounds in theprocess. “I’m what they refer to as a success story,” she says. Shenow enjoys regular yoga sessions and strives each day to record10,000 aerobic steps on her pedometer.

Aboriginal Walking Program participants reported that, apartfrom the fitness payoff, walking provided a break from routine,helped alleviate stress, and provided time to think and relax.Joint participation by students and staff also increased cama-raderie, says teacher Kaleb Child, who with teacher Tye Swallowcoordinated the walking program at the Adult Education Cen-tre. “The first year we did the Vancouver Island race, it was kindof like an ongoing intramural program,” Child says. “It (created)a real sense of solidarity, team spirit and school spirit.”

The next race grew to 2 1/2 months, with the target destina-tion spanning Canada. With more pedometers, participationclimbed to about 75 people. It also extended to the TribalSchool, with a three-month program for preschool to Grade 9students.

The pedometers were critical. Apart from being fun gadgetsthey “let them celebrate their accomplishments on a dailybasis,” Child says. Competition was important, too. With therace component, “people didn’t want to lose a step.”

WHILE INDIVIDUAL SUCCESSES WERE REALIZED THROUGH THE DIABETES

Prevention Project, broader goals were met as well. The initialeight partners grew to 20. The resulting awareness among com-munity groups about their respective programs and their abilityto coordinate, not duplicate, services, has been a success initself, Wharf Higgins says.

Another goal is to simply maintain the momentum. The pro-ject’s legacy includes a pedometer-lending program at the Sid-ney public library and the training of senior and Aboriginal fit-ness leaders. The Adult Education Centre is lacing up for its next“race,” thanks to funding from the Saanich Indian School Boardfor 20 more pedometers. And then there are people like Brodskywho, after reaping the personal rewards of fitness and goodnutrition, are sharing that wisdom with others. Ideally, WharfHiggins would like to see a funded position to coordinate a con-tinued Peninsula program.

In a larger context, Wharf Higgins says the project has under-lined the “need to urge policy makers and the public to shifttheir view of public recreation beyond fun and games, to thehigher status of essential services.” Her point is that if recre-ation centres received more support for their programs andfacilities, it would be easier for people to participate, get health-ier, and reduce the burden on health care.

“The dwindling public purse and increased user fees makewhat is theoretically and historically a public service, intendedto benefit all citizens, accessible only to those who can afford topay. Rather than funneling more and more tax dollars into pub-lic health care, we would argue that earmarking a small portionto disease prevention and health promotion makes muchgreater sense.” T

Jennifer Blyth is a freelance writer in Victoria.

26 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

YOUTH HEALTH

THE 9 A.M. BUZZER SIGNALS THE START OF CLASSES AT THE CHEMAINUS

First Nation’s Stu” Ate Lelum Secondary School. Two girls chatas they enter a classroom where they’re about to start theirweekly participation in a university research project. The UVicCentre for Youth and Society calls it the Adolescent Girls’ Men-torship Study. The students here call it “girls’ group.”

Another girl shifts tables, dragging them together for thegroup. Her hardcover notebook for journal writing—each girls’group participant has one—is out and she seems eager to start.

But there is no easy feeling of camaraderie as the group’s six15- and 16-year-old girls settle in. Maybe it’s a reaction to themomentary presence of a square-looking white guy who’s writ-ing about them for a university magazine, but between mostgroup members there is only a guarded acknowledgement. Notall of these girls were friends before the group started meetingfour weeks ago, but that is changing.

“Some of the girls were so closed in,” says the group’s mentor,Samantha Sam. “They didn’t talk to anyone or try to befriendanybody who was a stranger to them.” But the girls in the group,which focuses on their dating relationships, are becoming moreopen and comfortable with each other as the weeks go by.

Sam, 30 years old, lived through many of the same issues asthe girls she is mentoring. She grew up poor, on reserve and infoster homes. At 15, she got into an abusive relationship that

took five years to escape. She dropped out of high school tohave a baby when she was 18.

“I’ve learned that when I open up more myself, that helps thegirls open up during the session. I say my life experiences andmy regrets. Then I’ll go on to all the goals I’ve achieved, andthey’re really listening. I can talk to the girls about that.”

The Stu” Ate Lelum group is the latest in a series that focuseson teenage girls’ intimate relationships. In 1997, a Victoria com-munity health clinic asked Elizabeth Banister, a professor in theSchool of Nursing, to research the most pressing health con-cerns of adolescent girls. Through focus groups and forums, shefound that girls linked many of their health concerns, includingunprotected sex and dating violence, to their relationships withboys.

“When you talk about health issues with them, it alwayscomes back to relationships. Their relationship concerns endup becoming a thread through most (of their) health issues.”

Banister has developed a model for small groups of teenagegirls to share experiences, strategies and information. Since1999 there have since been 11 such groups, most of them in Vic-toria, typically involving eight girls, a facilitator/research assis-tant, and a mentor. As well as their regular meetings, the groupsgo on educational outings to community agencies that the girlsthemselves select. Banister and her research team are preparing

CatchingDreamsTeenage girls and relationships: sometimes talking it out with a mentor,

someone who has been there, can make all the difference in the world.

BY M A R K VA R DY, BA ’ 0 5P H OTO G R A P H Y B Y H É L È N E C Y R

A drawing created by VioletSampson, memberof the ChemainusFirst Nation and aparticipant in theadolescent girls’mentorship study.

S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 | U V I C TO R C H 27

two curriculum manuals—one of which, funded by HealthCanada, incorporates First Nations traditional knowledge—thatwill enable community groups across the province, and per-haps the country, to run similar groups.

Although dating violence receives a lot of attention, it’s not thegroups’ exclusive focus. “It’s also (about) asserting your needs,and developing a sense of your own self, and connecting withwho you are in a relationship. We help the girls identify whenpower dynamics were unequal in a relationship and what that

would look like,” says Banister. “It’s important to focus on girls’thinking, the way they see themselves and others.”

The mentorship study is among seven community-based pro-jects on youth injury prevention—together known as the Com-munity Alliance for Health Research—funded by the CanadianInstitutes of Health Research and organized by the UVic Centrefor Youth and Society.

Each group’s mentor is chosen by the girls and shares both hernegative and positive life experiences. Sam graduated from Stu”Ate Lelum in 1995. She had dropped out twice, once to have herbaby, and again when leaving her boyfriend. But she was moti-vated to finish high school and then go on to earn a certificatein business skills. “Watching all my aunts and uncles and mymom…alcohol, not working, not educated, I just wanted to dosomething, be able to have a job to have money to do things.”

Sam has worked at Stu” Ate Lelum for over six years, first asreceptionist and now as executive assis-tant. She is working toward a diploma inmanagement through BC Open University.And, having broken the cycle of beingstuck in abusive relationships, she is in ahealthy and supportive one.

“I get things on my birthday now. Thegirls laugh along with me about all thegood things that are happening to me now.They know what I’ve gone through.”

WITH 20 MINUTES LEFT IN THEIR SESSION, THE

group is making traditional dream catch-ers. Brass hoops, beads, feathers and pipe-cleaners brighter than a new box ofcrayons are scattered on the table. The girlsare more relaxed with one another, lesscautious.

Before working on their dream catchers,Banister says, the girls discussed their per-sonal goals, most of which centre on edu-cation. One participant’s goal is to contin-

ue her daily attendance at Stu” Ate Lelum. Others share the goalof graduating from high school.

The girl who pushed tables together earlier in the morning isplacing specific beads in her dream catcher to remind her of hergoals: “Getting a degree in being a daycare worker, and being aprofessional dancer.”

Banister nods. She says a degree in child and youth care wouldbe a good option for daycare work. The girl speaks up again. “Ithink we should have talked about our goals while we were

making dream catchers, instead of before.” Banister thanks herand tells her it’s a good idea for future girls’ groups.

Sam is quietly writing the girls’ names on large brownenvelopes to store their dream catchers until they finish them attheir next meeting. After the girls have left, she says that if sucha group like this existed when she was a teenager, she mighthave made different choices in her life.

“I just did things on my own, what I felt was right,” she says. “Ihad no mentor, no older sisters, no aunties or mother aroundme.” Now, after making a difference in these girls’ lives she isrethinking her own goals. She’ll complete her diploma in man-agement, she says, and then she just might pursue a careerworking with and helping teens. T

Mark Vardy will graduate in November from the UVic Writing program.

“Their relationship concerns end up becoming a threadthrough most (of their) health issues.”

Nursing Prof. ElizabethBanister: a focus on theway girls “see themselvesand others.”

Buying a Franchise in Canada:Understanding and Negotiatingyour Franchisee AgreementTONY WILSON, LLB ’85Franchises seem to be everywhere but itcan be hard to find legal material writtenspecifically for prospective franchiseowners. Wilson offers a guide to avoidingthe legal pitfalls that can come with afranchise, strategies for negotiating a bet-ter franchise deal, and a discussion of thepros and cons of owning a franchise.Self-Counsel Press, 2005 • 192 pages • $18.95

Dark Sun:Te Rapunga and the Quest of George DibbernERIKA GRUNDMANN, MA ’89The life story of German-born GeorgeDibbern (1889-1962), interned in bothWorld Wars, sailor-philosopher,vagabond, friend of all peoples. A self-proclaimed citizen of the world, he creat-ed his own passport and flag and used his10-metre ketch as a means of buildingbridges of international friendship.David Ling Publishing (NZ), 2004 • 510 pages • NZ$50

Everyone Can Cook SeafoodERIK AKIS, Cert. ’96Culinary basics combined with dozens ofrecipes—from baked oysters withspinach and parmesan to miso-glazedsalmon steaks—show any home cookhow to prepare seafood on the stovetop,on the grill and in the oven. The newbook picks up where Akis’ popular Every-one Can Cook left off.Whitecap Books, 2004 • 224 pages • $22.95

Going CoastalWENDY FRENCH, BA ’94French’s writing has been called “chick-litwith snappy humour” and this, her sec-ond novel, promises more of the same.Jody Rogers, a 20-something small-townwoman whose coming off a failed rela-tionship, a job resignation and has noprospects—romantic or otherwise—onthe horizon.Forge Books/H.B. Fenn and Co., 2005 • 304 pages • $17.95

The Last Heathen:Encounters with Ghosts and Ancestors in MelanesiaCHARLES MONTGOMERY, BSc ’91Montgomery followed the steps of hisgreat-grandfather, the Anglican Bishop ofTasmania, through the South Pacific. Thenovel becomes a debate on the nature ofmagic, myth and religion—and ametaphor for the transforming power ofstorytelling. Winner of the 2005 CharlesTaylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction.Douglas & McIntyre, 2004 • 314 pages • $24.95

Last Notes TAMAS DOBOZY, BA ’91The second collection of stories from theNanaimo-born writer shines with irony,wisdom, dark comedy and a sense of thebonds of history, the pain of lonelinessand the price of fidelity. HarperCollinsCanada, 2005 • 192 pages • $24.95

The Pearl KingCATHERINE GREENWOOD, BA ’99Poems drawn from the stories and leg-ends surrounding the development of cul-tured pearls by Mikimoto, the “PearlKing.” Greenwood’s first collection probesthe conflict between nature and manufac-turing, and the quest for beauty.Brick Books, 2004 • 134 pages • $16.00

Unmarked Landscapes Along Highway 16SARAH DE LEEUW, BFA ’96Stories from northwest BC’s rough land-scape of fishing and logging communi-ties related through richly detailed per-sonal essays by a writer who has exploredlife along the road from Prince George toPrince Rupert.NeWest Press, 2004 • 128 pages • $19.95

Starfish

A plagueof fingersmiths,as though the starshad all falleninto the seaand become pilferingcold purple hands,the starfish searchamong slumbering oyster bedsfor the sunken reflectionof the moon, blindlybreaking the hingesof the shells,picking the lockson the luminous dream.

CATHERINE GREENWOOD

from The Pearl King

SELECTED TITLES FROM UVIC AUTHORSBOOKMARKS

Send forthcoming book notices [email protected]

28 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 | U V I C TO R C H 29

ALUMNI ARCHIVE

1 9 7 0BILL WHITE, BA, is a guidance counsellor at Mill-wood High School in Halifax. “Following gradua-tion I was a navy officer for three years, then leftto pursue a teaching career in Nova Scotia. MyUVic geography degree was a great selling feature!I’ve been a guidance counsellor since 1983.”

1 9 7 5LARRY ROSE, MA, is the news director at CKCOTelevision in Kitchener-Waterloo, and writes:“Anyone remember the old Lansdowne campus?Lectures in the Young building (which, of course,was actually a very old building)? Or perhaps thedart between Lansdowne and the new campus atGordon Head? Well, the above goes back to 1964so chances are most faculty, graduates and, mostcertainly, present day students, would notremember. So there’s definitely a geezer factor inmy recollections of UVic. It was an exciting timewith a feisty political climate on campus and off.We took part in huge protest marches to the legis-lature over university funding; the university wasnew and exploding in growth; and the experienceon campus was a marvelous though intimidating

adventure for someone from the small communi-ty of Rossland. I have gone back to Victoria onlyrarely but I did visit a couple of years ago and thechanges to the scale of the campus and the num-ber of new buildings is astonishing. As newsdirector at CKCO I receive stacks of resumes fromprospective employees. Last spring I came acrossone from an outstanding young journalist andnoted that we shared a background at UVic. As ithappened we were able to offer him, KYLECHRISTIE, BA ’99, a job and he has done excep-tionally well. So, we are UVic’s K-W connectionand I have enjoyed sharing UVic experiences.”

1 9 7 9PATSY PETERS (nee BAWLF) BA, is teaching coreFrench and is the department head of modernlanguages at David Thompson Secondary Schoolin Vancouver. “I completed my teaching diplomain French and socials at UBC and went on toteach 12 years at John Oliver Secondary Schoolbefore moving over to David Thompson in 2001. Icompleted my master’s degree in leadership andadministration in 2004 at UBC. My daughter LaraPeters is now completing her degree at McGill

University. Love to hear from any of the oldpartiers from the “SubPub” days.

1 9 8 1VICKI EASINGWOOD, LLB, recently moved fromVictoria to Duncan: “I have started a boutique-stylelegal practice dealing primarily with family lawmatters as well as providing support services toclients in day-to-day changes and challenges fac-ing them during a separation and divorce. Media-tion and negotiation are preferred to litigation.”

1 9 8 3GERALD KAZANOWSKI, BA, has been named tothe Canadian Basketball Hall of Fame. After lead-ing the Vikes to four straight national titles (1980-83), Gerald was drafted by the NBA’s Utah Jazz andenjoyed a pro career in Europe, Argentina andMexico. He also played for Canada at the 1984 and1988 Olympic Games. • IAN RESTON, BA andBARB RESTON (nee FERRIE), BEd ’88 providethis update from their home in Bratislava, Slova-kia: “After 10 years of teaching in Invermere, weattended a job fair at Queen’s University; we werehired by Quality Schools International and placed

Final Exams,1971Security patrolman Ray Stenningchecks one of the 527 exam desksthat awaited anxious students onApril 15, 1971. It was a rare quietmoment on a campus embroiled inan intense controversy over facul-ty tenure. The photo was shot inHut S, used as the main gymnasi-um until 1975 when the McKinnonGym opened for athletics andbecame the new home of themass exam-writing ritual.

(PH

OT

O:

WIL

LIA

M A

. B

OU

CH

ER

/UV

IC A

RC

HIV

ES

#0

50.0

20

8)

KEEPING IN TOUCH [email protected]

30 U V I C TO R C H | S P R I N G 2 0 0 5

ALUMNI NEWS

at one of their schools in Slovakia. Our two boys(Brodie, age 9 and Peter, 6) attend the sameschool. After years of people asking us, ‘Where isInvermere...?’ we have apparently moved toanother obscure location—no it is NOT Czecho-slovakia nor is it Slovenia! Bratislava at one timewas the capital, called Pressburg, of the Austria-Hungarian Empire. We are a mere 40 kilometresfrom Vienna! Our family is surround-ed by history, new experiences and achallenging new language!”

1 9 8 4WARREN TANINBAUM, MPA, is acommander with the US Naval Reserveand recently served two years of activeduty in Rota, Spain. He will be partner-ing with a Toronto-based trainingcompany offering programs in sales,management development, communi-cations and team development. He lives in Atlantawith his wife Loretta and their two daughters.

1 9 8 5JACQUIE PEARCE, BA, completed a master’s inenvironmental studies at York and worked briefly

in Toronto at the Canadian Children’s Book Cen-tre before returning to BC. “When health prob-lems forced me to reprioritize my life I decided tofocus on my real love: writing for children. In 2002my first novel for children, The Reunion, was pub-lished by Orca Books and my fifth book, DogHouse Blues, will be out this fall. I am married toCRAIG NAHERNIAK, BA ’85.” • ROBERT

SLAVEN, BSc, reports from his homein Surrey: “As a former five-time Jeop-ardy champion (1992, where I won$53,202 US), I was invited to partici-pate in the Jeopardy! Ultimate Tour-nament of Champions, which startedairing Feb. 9. My first-round appear-ance aired in March. The tournamentwill culminate in a three-day final inMay against Ken Jennings for a firstprize of $2 million. Details at jeop-ardy.com.”

1 9 8 7DAVID ARSENAULT, BA, is working in Pentictonwhere he and his partner have welcomed a newbaby boy. David also completed his MBA in 2004.• KERRY GODFREY, BSc, has been appointed

dean of business and leisure studies at the UHI(University of the Highlands and Islands) Millen-nium Institute in Scotland. He was director ofpostgraduate programmes and principal lecturerin tourism development at Oxford Brookes Uni-versity before joining UHI. • DENYSE KOO, BA,has joined the Sooke Neighbourhood House as itsprogram co-coordinator.

1 9 8 8DAVID BUCHAN, BMus, has been involved withmusic since graduating from UVic through bothchoral and instrumental conducting as well asthrough accompanying. He’s the choir directorand head of the music department at Colling-wood School, in West Vancouver. The musicdepartment there has performed in Japan, Eng-land, Scotland, Australia, and the U.S. David hasalso worked with the Vancouver Welsh Men’sChoir as both pianist and associate director overthe past 10 years, performing through Russia,England (Royal Albert Hall) and Wales. • DAWNDOIG (nee Young), BSc, and BRUCE DOIG, BEdand BA ’92, check in from their home in Yel-lowknife, NWT where she’s an audiologist and he’sa teacher: “Bruce and I and our two children (ages

ROBERT SLAVEN, ’85

AT THE END OF JUNE I WILL HAVE COMPLETED MY SEC-ond term as President of the Alumni Associationand this is likely my last message in the Torch. Ihave greatly enjoyed the experience and it has leftme with the firm belief that the future is verybright for both the university and the association.

During the last few years the university hasexperienced considerable growth. There are sev-eral new buildings including student’s resi-dences, the Island Medical Program Building, theEngineering/Computer Sciences Building, theContinuing Studies Building and the TechnologyEnterprise Facility. Many more new building pro-jects are in the planning stages. These includethe expansion of the library, the First Peoples’ House and more.It’s clear that UVic has become an institution of stature with ahistory and an identity of which all alumni can be proud.