Thewindsbeneathyouthswings

-

Upload

jonathan-dunnemann -

Category

Education

-

view

6.269 -

download

0

Transcript of Thewindsbeneathyouthswings

“What <can> emerge from religion is individual worth of character.” -- Alfred North Whitehead

“The Winds beneath Youth’s Wings: A Proposed Mentoring Program of Humility and Humanity”

Jon Dunnemann, B.A., Michael Poutaine, Ph.D. & Nancy Hansen-Zuschlog, M.A.

Imagine a map drawn from your memory instead of from the atlas. It is made of strong places stitched together by the vivid threads of transforming journeys. It contains all the things you learned from the land and shows where you learned them. Think of this map as a living thing, not a chart but a tissue of stories that grows half-consciously with each experience. It tells where and who you are with respect to the earth, and in times of stress or disorientation, it gives you the bearings you need in order to move on. We all carry such maps within us as sentient and reflective beings, and we depend upon them unthinkingly, as we do upon language or thought and, it is part of wisdom, to consider this ecological aspect of our identity.

– John Tallmadge, Meeting the Tree of Life (1997: IX)

Abstract

The mission of “The Winds beneath Youth’s Wings: A Mentoring Program of Humility and Humanity” is to “create a life space” of nurturing by building a caring, cohesive, harmonious, moral, trustworthy atmosphere of warm and communicative relationships, and positive emotions, (e.g. bliss, contentment, gratitude, humor, joy, love, pleasure, serenity). In addition, we encourage an outlook of optimism, to facilitate social connection, to promote personal goal setting and strong follow—thru, and deep and insightful reflection among all participating youth. Individuals with Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties (EBD), that have fallen off-track, learn how to engage in the reappraisal of their environmental mastery, self-acceptance, and identity formation. Through personalized and flexible guidance, youth become equipped at identifying a clear purpose for their life, thereby achieving a greater sense of autonomy, effectively building better and more enduring relationships with others and developing a flourishing sense of spirituality and overall wellbeing. These tasks take place by facilitating and supporting youth in finding the positive meaning and long-term benefit within their best, worst and seemingly ordinary experiences each day. A study conducted by Barbara L. Frederickson, Director of the Positive Emotions and Psychological Laboratory at the University of Michigan revealed that positive emotions help broaden people’s mindsets. This leads to the discovery of novel ideas, and can undo the lingering effects of negative emotions (e.g., anger, contempt. defensiveness, disgust, embarrassment, fear, frustration, guilt, sadness and worry) consequently changing how one thinks and behaves (2003). However, the achievement of favorable long-term outcomes are dependent on youth having the opportunity to be active participants in their environment, to share their feelings, to build and experience bonding relationships, within which they can learn to utilize a much broader thought-action repertoire for day-to-day coping and problem solving.

Introduction

“Our past is not our potential”

~Unknown~

When there is past wrongdoing involved, youth must be able to play a major role in addressing

their wrong and making things right. This takes place by offering those who have fallen off-track the

value-added opportunity to “learn to engage in a process of cognitive, emotional, behavioral, social and

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 2

spiritual self-assessment and motivation through which one learns to regulate destructive reactivity, refine

perceptions of self, others, and life; and heal the traumatic psychological wounds” which left unattended

to are likely to fester (Kass, 2007). As a resource for thoughtful, resilient, and prosocial responses to the

chain of pain, and the inherent crises of worldly existence, spiritual insight and transformation can be a

real “game-changer” in the lives of individuals and communities (Kass, 2007). Youth who believe that they

can achieve a desired outcome of self-organizing, self-reflective, and self-regulative actions are likely to

find that they can also live more self-fulfilling lives and do better psychosocially and academically. The

“can do” attitude that they manifest mirrors a kind of “mindfulness” over one’s environment. This type of

adaptive action, regardless of ones faith or cultural context, generates well-rooted inner optimism, a level

of confidence, mental toughness, and an overall commitment that fosters the sense that one truly has

“what it takes” to effectively deal with daily stressors, life issues, and problems. On the other hand, a low

sense of self-efficacy is typically associated with insecurity, depression, anxiety and learned helplessness

(Scholz, Bebincio, Shonali, & Ralf, 2002). Persons with low self-efficacy also have a correspondingly low

self-esteem, and they tend to harbor pessimistic thoughts about their accomplishments and personal

development (Scholz, Bebincio, Shonali, & Ralf, 2002). In addition, negative emotions may generate

cognitive confusion, often leading to the selection of some of the worst possible solutions to current

problems.

What is spiritual transformation?

What is envisaged, is not merely on the cognitive level, but on that of the self and being… a progress which causes us to be more fully, and makes us better… a conversion which raises the individual from an inauthentic condition of life, darkened by unconsciousness and harassed by worry, to… inner peace and freedom. One has to renounce the true values of wealth, honors, and pleasure, and turn towards the true values of virtue, contemplation, a simple life-style, and the simple happiness of existing.

~Pierre Hadot~

Transformation occurs, when the sense of self along with changes to the nature of one’s habitual

mental states and spiritual practices changes and one’s sense of self-direction over them changes as

opposed to one being under their control. Individuals then feel themselves transformed at the level of the

self-concept, because what the individual perceives as self, its content has overwhelmingly changed. “We

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 3

believe that spirituality may foster an integrated moral and civic identity within a young person and lead

the individual along a path to becoming an adult contributing integratively to self, family, community, and

civil society (Lerner, R.M. et al, 2005)”

In addition to exploring spiritual transformation within the context of the Protestant, “born-again”

experience, wherein the passage in 2 Corinthians 5:17 tells us that this change is indeed a spiritual

‘rebirth’: “The old has passed away, behold the new has come.” Spiritual transformation is included in

other religious traditions also resulting in a profound change in the self. “This change is radical in its

consequences – indicated by such constructs as a new centering of concern, interest, and behaviors [or

practice]. For example, in Islam God in the Koran also “turns” in mercy and forgiveness toward those who

“repent” taba, meaning turn to God. In Judaism, and rabbinic literature a ba’al teshuva is a “master of

return” or “master of repentance”. In Buddhism, transformation occurs as improved psychological

functioning in human relations. Buddhism is not only a set of doctrine and beliefs. It is not simply a ritual

or a set of rules to follow. Rather, it acts as a spiritual force that becomes visibly operational in ones daily

life. In early Buddhism, there are stories of people who encountered the Buddha and suddenly attained

the "spotless eye of truth." They came to realize the truth of Buddhism in their hearts and minds and

became followers of Buddha. Enlightenment in principle means transformation, bodhi or awakening. We

waken to the truth. We wake up from ignorance, delusions, greed, hatreds and prejudices. It means to go

beyond the petty, superficial misunderstandings that cause discrimination against others. The awakening

brought about in Buddhism helps us to deal with our anxieties and our unhappiness. Indeed, one

objective of this proposed program and initial empirical study is to identify whether there exists a cluster of

universal affective traits that are common to all spiritually transforming experiences, regardless of

denomination or a particularly religious orientation (Schwartz, 2000) that can motivate and substantiate

changes in human behavior (Piedmont, 2004). Although Judaism, Islam and Buddhism do not use the

term ”born again,” these traditions clearly recognize the reality of spiritually transforming experiences that

can be witnessed through behavior constructs or ‘mechanisms’ (Shapiro, 2006).

Abraham was a shepherd and an architect. Lao Tzu was an archivist. Mahavira and Siddhartha

Guatama were both princes. Confucius was a government worker. Socrates was a decorated soldier.

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 4

Jesus Nazareth was a carpenter and Muhammad a tradesman. Nanak was the manager of a store.

Martin Luther was a monk, Gandhi a lawyer, Mother Teresa a nun and Henry David Thoreau was a

Harvard graduate. All of these people were wise but at first glance, it seems that they have very little in

common. Yet, as we move deeper into an understanding of these individuals, we come to discover a

number of similarities (Dunn, 2005). Whenever they became engaged with others in dialogue, they all

acted 1) “On purpose” or intention, 2) “Paying attention” or intention, and 3) “in a particular way” or

attitude (mindfulness qualities). Shauna Shapiro & et al., in their article that appeared in the Journal of

Clinical Psychology, refer to these three components as “The Axioms” of Mindfulness (Shapiro, Carlson,

Astin & Freedman, 2006).

Spiritual transformation can be tremendously valuable.

“No one can define for us exactly what our path should be. Instead, we must allow the mystery and beauty of this question to resonate within our being. Then, somewhere within us, an answer will come and understanding will arise. If we are still and listen deeply, even for a moment, we will know if we are following a path with heart.”

~Jack Kornfield~

In a famous quote, F. Scott Fitzgerald once said that there are no second acts in American lives;

but Fitzgerald could not have been more wrong. From the time of the Puritan settlements to the present

day, Americans have reveled in stories of self-transformation. The self-proclaimed land of opportunity,

America has been imagined as a place where people can start over, pursue a new dream, and make a

life whose many scenes spell out second and third acts and even more. Americans have been reinventing

themselves ever since Benjamin Franklin (in 1771) showed them how he did it in his Autobiography

(McAdams, 2006).

To respond to life’s ever-changing conditions with inner-peace and compassion for the other, may

require disciplined, contemplative practice that transforms our fundamental perceptions of life, others, and

self (Kass, 2008). According to Ralph Piedmont (2004), “each of us must construct some sense of

purpose and meaning in life”. For example, we might ask ourselves, “Why am I here? What purpose does

my life serve? Why should I do the things I do? Our responses to these questions set the tempo, tone,

and direction for our lives. The answers to these questions “help to pull together the many disparate

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 5

threads of existence into a more meaningful coherence that gives us the will to live productively (Frankl,

1996)”.

Pargament (1997) posits that while most of the scientific research and theory in recent years has

focused on the conservational nature of religion, “religion has the transformative power to create

radical personal change.”

Almost one hundred years ago William James captured the essence of this transformation when

he wrote: “To say a man is ‘converted’ means that religious ideas, peripheral to his

consciousness, now take a central place, and that religious aims form the habitual center of his

energy (1902:276, emphasis added).

Although individuals must take full responsibility for their actions and lives, they can derive

meaning from the experience of relationship with life’s spiritual core. Tillich and Frankl suggest that a

primary cause of an individual’s most fundamental experience of anxiety is the perception that life lacks

intrinsic meaning (Frankl, 1959; Frankl, 1969; Tillich, 1952). In addition, they have suggested that a

primary source of psychological strength is through a relationship with the transcendent reality (Frankl,

1966; Tillich, 1952). Thus, meaning in life can be experienced, not simply as a functional derivative of

one’s personal goals or work, but as an ontological attribute of life itself. In this worldview, individuals are

fundamentally not alone. While they are still personally responsible for determining the meaning in their

lives, lasting meaning comes about through a relationship with the sacred aspect of life. In the article,

“Finding the Wise People”, Dr Jeff Myers says, “it occurred to me some time ago that the wisest people I

know all have something in common: they voraciously seek wisdom! This quest for wisdom, truth, and a

personal relationship with the One, is by far the most common trait amongst the wise. The Vision Quest

helps the seeker to realize his/her oneness with all life and that all creation is his own relative (Dunn,

2005). According to Jared Kass, “experiences of the ‘spiritual core’ [are] part of normal developmental

growth, rather than beliefs [which] are imparted through a theological system.

Consequently, I began to conceptualize ‘experiences of the spiritual core’ as a naturally

occurring, inherent perceptual capacity of individuals. In addition, I begin to view them as part of a

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 6

development process in which individuals become increasingly self-empowered in their actions,

and increasingly able to affirm the deepest aspects of their identities (Kass, 1995).

The central question that together we seek to examine though is how does faith and spirituality

positively affect the emotional and social behavior (self-regulation and control) of adolescent and young

adults facing difficulties in their lives on a regular basis (i.e. at a minimum weekly)? Roger Walsh, M.D., &

Ph.D., is the author of Essential Spirituality: The seven central practices. He informs his readers that

"Comparison across traditions suggests that there are seven practices that are widely regarded as central

and essential for effective transpersonal development; 1) an ethical lifestyle, 2) redirecting motivation, 3)

transforming emotions, 4) training attention, 5) refining awareness, 6) fostering wisdom, and 7) practicing

service to others (1999).

Transitional youth

It is radically empowering to say that suffering is caused by human Maladaptation to the way things are, and that it can thus be eliminated by a psychological adjustment—by evolving our understanding and learning to respond differently.

~Andrew Olendzki~

The time of transition from adolescence to young adulthood is a critical period that can shape the

adult life span. As we know from research in cognitive therapy, the cognitive schema through which we

respond to this stress has a telling effect on our wellbeing and the wellbeing of others (Davis & Stoep,

1997). Youth are in need of empathic services that will assist them in their successful crossing over from

adolescence to young adult behavior and functioning in the community. The Winds beneath Youth’s

Wings: A Mentoring Program of Humility and Humanity targets youth between the ages of 13 to 20 years

old, who have experienced alcohol abuse, anxiety, depression, frequent disciplinary problems, hostility,

impulsivity, juvenile crime, loss, social isolation, and trauma, or may have hurt someone through their

inappropriate behavior. Others may have reacted negatively and or have even contemplated suicide.

Acknowledging responsibility for past wrong doings, they have quietly endured the consequences of their

actions. These youth now seek understanding, forgiveness, grace, love, mercy, meaning in life, personal

growth and effectiveness, positive influences, reconciliation, regeneration, and sound teaching of core

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 7

morals and personal values that will equip them to overcome a divided self, transform their past attitudes,

feelings and behaviors, enabling them to better weight their available options, and attain greater wisdom

in the process. In many ways, these youth can potentially have a constructive and profound impact on

the lives of their peers and younger youth as their on-going self-awareness, transformation, the internal

management of their behavior, their social problem solving competencies, and an ability to maintain close

friendships and overall well-being increases over time. An expected outcome through ones involvement in

The Winds beneath Youth’s Wings program is that youth will become better able to anticipate, recognize,

and understand the negative consequences of specific actions before taking action. This will result in

intentional, positive outcomes, and far fewer negative consequences and experiences. Kabat-Zinn writes,

“Your intentions set the stage for what is possible. They remind you from moment to moment of why you

are practicing in the first place (Kabat-Zinn, 1990).”

In Matthew 4:1-2, Jesus begins his Vision Quest by being, “led out into the wilderness by the Holy

Spirit to be tempted there by Satan. For forty days and forty nights, he ate nothing and became very

hungry. Around 610 AD Muhammad sought spiritual asylum in the mountain caves near Mecca. Having

spent months in solitude, Muhammad was visited by the archangel Gabriel, the same angel that had

visited Christ’s Mother, Mary, and told Muhammad to proclaim the Oneness of God. Mahvira, one of the

great founders of Jainism, spent thirteen years wandering in India. “He lived without clothing or a house

and went without food for weeks at a time. He endured insults, injuries, and insect bites without

complaint. In one story, some herdsman set fire to Mahriva’s feet and drive nails into his ears as he

meditated, but he did not flinch (Dunn, 2005).” In all of these examples, the individual maintained a strong

and consistent commitment to their defined purpose or intentions. They did not allow themselves, no

matter the circumstances, to become distracted or defeated in the midst of their trying ordeals or in the

complete fulfillment of their goals.

Many cultures have adopted this Vision Quest as an intrinsic part of life. In the Hindu tradition of

Ashrams, ‘The Four Stages’ of an ideal path of life is set forth. This code of living, developed in the 1st

century BC by Manu, stated that men should live as hermits and holy wanderers during their life. Possibly

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 8

the most recognized culture that incorporates the Vision Quest into their lives is that of Native Americans.

Black Elk, a famous Oglala Lakota Medicine Man [or Holy Man], says this of the Vision Quest; “Every

man can cry for a vision, or “lament”; and in the old days we all -- men and women – “lamented” all the

time. What is received through the ‘lamenting’ is determined in part by the character of the person who

does this...” Since time, immemorial people have gone to the wilderness to seek guidance, renewal, to let

their old lives and old selves die, to find the conditions where spirit may be rekindled, reborn within them

(Dunn, 2005).

Youth (and adults) become stronger when they find “transpersonal” connection to something

bigger and deeply more meaningful than just satisfying themselves, “for example, the furtherance of some

great cause, union with a power beyond the self, and or service to others as an expression of

identification beyond the personal ego (Rivers, 2006)”. By our nature, every person must eventually

search for their truth, freedom, integrity, meaning and purpose (i.e. why one is practicing (Bishop et al.,

2004). A good place to begin this is by embracing family and social responsibilities, promoting common

causes through teamwork, initiating healthy relationships, doing volunteer work that addresses the unmet

needs of others in the community, while simultaneously growing into healthier individuals of realized and

satisfied self-acceptance, and personal worth and spiritual maturity.

Empathy is the psychological means by which we become part of other people’s lives and share

meaningful experiences. The very notion of transcendence means to reach beyond oneself, to participate

with and belong to larger communities, embedding oneself in complex webs of meaning (Rifkin, 2009). To

honor all things, in relativity to the definition of wisdom, is to recognize the oneness of all things (Dunn,

2005). “Beauty is not within one’s skin nor is justice or order.” (Maslow, 1969) According to Arlen Wolpert

(2006), “The aim is to find an uncompromising balance between one’s inner or religious life and one’s life

in the world. This is what it means to ‘walk the razors edge’ (Katha Upanishads III:14; Mathew7:13-14).”

How does one become aware of their attachment to life’s spiritual core?

“Look at every path closely and deliberately. Try it as many times as you think necessary. Then ask yourself and yourself alone one question. This question is one that only a very old man asks. My benefactor told me about it once when I was young and my blood was too vigorous for me to understand

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 9

it. Now I do understand it. I will tell you what it is: Does this path have a heart? If it does, the path is good. If it doesn’t, it is of no use.”

~C. Castaneda~

When we understand that every human being on this planet is interrelated to every other person

through our shared connection to life’s spiritual core, we recognize why it is necessary to learn to love ‘the

other’ as our self. This profound state of moral and spiritual awareness, central to the teachings in all

spiritual traditions, is often missing in North American society, partly because we do not recognize secure

existential attachment as a developmental possibility. Yet the capacity for connective awareness (the

perception of intrinsic attachment between self, others, and the universe) is a developmental potential

within every human being. When we treat this developmental stage as an idyllic, unrealistic concept,

rather than a state of awareness that can be nurtured and achieved, we undermine our efforts to create a

society that is peaceful and just (Kass, 2001, 2008). This is especially relevant from the context of the

current international focus on positive psychology, which aims to “create a science of human strength

whose mission will be to understand and learn how to foster these virtues in young people” (Seligman &

Csikzentmihalyi,2000). Furthermore, it appears that a holistic approach to “healing”, therapy, health and

wellbeing, focusing on the integration of mind, body, and soul, is currently infiltrating the field of

psychology. As Kabat-Zinn (1990, as cited in Shapiro & Schwartz, 2000:131) points out, “science is

searching for more comprehensive models that are truer to our understanding of the interconnectedness

of space and time, mass and energy, mind and body, even consciousness and the universe”. The

concept of ‘mindfulness,’ is especially pertinent within this context, and shows potential promise as one

such model. Gaining greater insight about how adolescents experience mindfulness may generate further

understanding or research into the applicability of mindfulness [practice] to an important section of the

population, within the context of current trends and movements towards a positive psychology and

integrated holistic approaches to health and wellbeing (Dellbridge, 2009).

A New Kind of Religious Inquiry

Those experiences—voices and visions, responses to prayer, changes of heart, and deliverances from fear, and assurances of support—are the primary constituents of religious life. The meaning of the term “God” is those experiences.

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 10

~William James~

We put forth our first theory, that the combination of exemplary mentor facilitated dialogue,

deliberate critical thinking, loving kindness meditation, used to illuminate the nature and value of positive

emotions in building and broadening self-understanding and resiliency, and person-centered action

planning represents a formidable and integral set of resources for the support of youth with emotional and

behavioral difficulties (EBD). The second theory we wish to present here, is that the aforementioned tools

favorably contribute to the development of personal effectiveness, social responsibility, self-management

of one’s behavior, social problem solving, additional competencies, maintenance of important friendships

and relationships, and active coaching, maintenance coaching, and follow along support that is done and

decisions that are made in total partnership with youth.

Spiritual experience enhances emotional intelligence.

Spiritual education, therefore, implies the existence of an emotional relationship with the divine or personal object of one’s worship and devotions called God, Allah, Yahweh, Unknowable Essence, Heaven, Tao, etc. The Divine luminaries of the human civilization such as Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, Buddha, Krishna, The Bab and Bahu’u’llah have been the perfect mirrors of this personal relationship and its transforming influence. Mothers, beginning with conception, are the first educators of human spiritual nature through their emotional shared experience with their offspring. Prayer is an emotional engagement and relations process. More research is needed into the physical, mental, and spiritual powers of prayer and meditation. Abdu’ l-Baha writes: “Meditation is the key for opening the doors of mysteries.” Although the power of meditation is a mystery to man, its impact in self-mastery and regulation, creativity and discoveries is as old as man.

The Winds Beneath Youth’s Wings: A Mentoring Program of Humility and Humanity responsibly

teaches youth to look at new experiences and opportunities that will help to increase their understanding

of transcendence, personal relationships, codes to live by and specific spiritual values; honesty, courage,

patience, tolerance, compassion, kindness, forgiveness, generosity, joy, hope, and above all love. All of

these factors help in creating meaning in one’s life. It consists of exegetical and pedagogical practices

that promote a humanity of higher values (and attitude of mind) of a cooperative vision for what is just,

peaceful, and unites humanity throughout the world. Life changes when we find ourselves filled with a

sense of wonder.

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 11

There is no place in schools for the emotional experience of divine love.

Communities that thrive and prosper in the future will do so because they will acknowledge the spiritual dimension of human nature and make the integrated moral, emotional, physical, and intellectual development of the individual, a central priority in their education programs.

~ Center for Global Integrated Education (CGIE) ~ Our societal response to intra-religious degradation and disintegration and polarization between

religion and science has resulted in the banning of a shared emotional attraction and experience from the

centers of learning. Schools are mainly a place for the cognitive experience provided by science.

This very shortsighted solution has led to the segregation of the two wings of human mind:

knowing and loving. To partake of the spiritual, the cohesive sense of shared values and emotionally

bonding experience in learning, children only have their parents and the limits of their segregated

religious community to turn to. The message is that the school is off limits to the emotional expressions of

shared values, the emotional context of learning right from wrong. Spiritual love, which is unique to the

human spirit and vital to its growth, is banned from the centers of learning while all other forms of love

which have to do with the lower nature and its appetites, such as love of power, money, status, comfort,

etc., are ushered in to fill up the vacuum. The result is that the student’s heart ends up robbed by these

lower loyalties and identities. Herein, rests the seed of the epidemic of emotional problems and

behavioral difficulties in our youth (Geula, 2004).

The 2001 Religious Influences on Life Attitudes and Self-Images Report reveals that for “31

percent of all 12th graders who attend religious services weekly and the 30 percent of high school seniors

for whom religion is very important they are significantly more likely than non-attendees and the non-

religious to;

• have positive attitudes toward themselves

• enjoy life as much as anyone

• feel like their lives are useful

• feel hopeful about their futures

• feel satisfied with their lives

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 12

• feel like they have something of which to be proud

• feel good to be alive

• feel like life is meaningful

• enjoy being in school

Religious teens tend to have a brighter outlook on the future. Most 12th graders feel hopeful about

their futures; 71 percent said they at least mostly disagree with the statement, “The future often seems

hopeless.” The picture is even brighter for weekly religious services attendees, those for whom religion is

important and those who have participated in religious youth groups for six or more years. These teens

are significantly less likely to feel hopeless about their futures than non-attendees, those for whom

religion is not important and those who have never participated in a religious youth group. Baptists,

Catholics and Mormons are also less likely to feel hopeless than non-religious teens. These relationships

are statistically significant, controlling for race, age, sex, rural/urban residence, region, parent, education,

number of siblings, whether or not the mother works and if the presence of a father/male guardian in the

household exists. (Smith & Farris, 2002)

Education without emotional context struggles to bear its ultimate fruit.

"We can either smother the divine fire of youth, or we may feed it".

~Jane Addams (1860-1935) ~

The segregation of the expression of universal love towards the one and only Unifier of humanity

has also backfired in further alienating hearts from one another and undermining the global emotional

benefits of a shared sense of values and universal emotional experience and attachment. If schools teach

moral education, it is mostly through an unemotional, cognitive, culturally centered approach, further

undermining the progressive laws of the oneness and equality of all humanity. The process of moral

education through the explanation of the natural and logical consequence of good and bad behavior, in

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 13

the global context of cultural relativism, does not go deep enough to produce individual behavior change

backed by the shared emotional support of a universal code of ethics or “matters of the soul”. Daniel

Goleman observes, “The beliefs of the rational mind are tentative; new evidence can disconfirm one belief

and replace it with a new one—it reasons by objective evidence. The emotional mind, however, takes its

beliefs to be absolutely true and so discounts any evidence to the contrary. Consequently, it has become

so hard to reason with someone who is emotionally upset: no matter the soundness of your argument

from a logical point of view, it carries no weight if it is out of keeping with the emotional conviction of the

moment. Feelings are self-justifying with a set of perceptions and ‘proofs’ all of their own.” (Goleman,

1995. P. 295). In the age of an abundance of information, the missing wing is the love that must lift the

spirit mobilizing one’s will towards self-regulation and self-discipline. Knowledge requires accompaniment

by self-motivation to lead into self-regulating actions (Geula, 2004).

Dialogue and critical thinking

“I have learned so much from God that I can no longer call myself a Christian, a Hindu, a Muslim, a Buddhist, a Jew.”

~Sufi Hafiz~

Dialogue is a communicative and investigative process engaged in by two or more persons (or

more persons (or communities) with differing beliefs, wherein each attempts to gain an increased

understanding of the other’s beliefs and the reasons for those beliefs. The primary goal in dialogue should

be understanding the other, rather than expressing one’s self, though self-expression is obviously also

essential to dialogue. The benefits of dialogue are many; among the most obvious are increased self-

understanding, improved understanding of others, better relations with others, and broad based

ideological research. Dialogue between equal parties should be beneficial to all involved.

It is not essential to dialogue for one to give up belief in the truth of one’s own system. It is

essential for one to give up the view that one has a “corner on the truth,” if one holds such a view. One

must be open to the possibility that some of one’s beliefs may be in error and that the beliefs of the

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 14

dialogue partner may be correct – or at least more correct than one’s own. (p. 379-380, Jones, 1999) As

Leonard Swidler has observed:

Religions and ideologies describe and prescribe for the whole of life; they are holistic, all

encompassing, and therefore tend to blot out, that is, either convert or condemn, outsiders even

more than other institutions that are not holistic. Thus, the need for modesty in truth claims and

for acknowledging, complementary or particular views of truth is most intense in the field of

religion (1990).

Genuine dialogue on human rights and freedom of religion or belief calls for respectful discourse,

discussion of taboos and clarity by persons of diverse beliefs. Inclusive dialogue includes people of

theistic, non-theistic and atheistic beliefs, as well as the right not to profess any religion or belief

(http://www.tandemproject.com). In these times, careful instruction on etiquette for dialogue has

never been more apparent and necessary as hardened boundaries continue to be forged in the public

sands of differing perspectives, positions, politics, and worldviews.

In the past, “before the nineteenth century in Europe truth, that is, a statement about reality, was

conceived in quite absolute, static, exclusivistic either-or manner” (Swidler, 1996).

If something was true at one time, it was always true; not only empirical facts but also the

meaning of things of the oughtness that was said to flow from them were thought of in this way.

For example, if it was true for the Pauline writer to say in the first century that women should keep

silence in the church, then it was always true that women should keep silence in the church; or if

it was true for Pope Boniface VIII to state in 1302, “we declare, state, and define that it is

absolutely necessary for the salvation of all human beings that they submit to the Roman Pontiff,”

then it was always true that they need do so. At bottom, the notion of truth was based exclusively

on the Aristotelian principle of contradiction: a thing could not be true and not true in the same

way at the same time. Truth was defined by way of exclusion; A was A because it could be shown

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 15

not to be not-A. Truth, was thus, understood to be absolute, static, exclusivistic either-or. This is a

classicist or absolutist view of truth (Swidler, 1996).

Loving-kindness meditation

“No forest, no moon, no ocean, no field, can be labeled “Buddhist” or Jewish” or “Muslim” or Christian.”

“Promoting a prosocial orientation has long been at the core of some Eastern philosophies,

however. In particular, Buddhist traditions have emphasized the importance of cultivating connection and

love towards others through techniques such as loving-kindness meditation (LKM). This practice in which

one directs compassion and wishes for well-being toward real or imagined others, is designed to create

changes in emotion, motivation, and behavior in order to promote positive feelings and kindness toward

self and others (Salzberg, 1995) (Hutcherson, Seppala, & Gross, 2008).”

Loving-kindness meditation is a standardized form of meditation used for centuries by the

Buddhist tradition to develop love and transform anger into compassion. The role of unchecked anger and

resentment is significant when it blisters into hatred, prejudice and various forms of abuse or violence.

Loving-kindness meditation can serve as a positive emotion-oriented strategy in reducing feelings

of depression, pain, and suffering. It helps in the release of ‘negative emotions’ toward a loved one,

toward oneself, toward a neutral person, toward someone who has caused harm, and lastly, toward all

living beings. “Often, the focus of loving-kindness meditation is on expanding compassion and care to

larger social groups, or even to disliked others (Hutcherson, et al 2008).

The rationale for testing loving-kindness meditation with the specific ‘transitional youth’ population

that we have an interest in serving is that it is one technique that may help produce an affective shift from

more negative emotions to more positive emotions. Clinical observations do suggest that the frequent

practice of loving-kindness meditation very often is accompanied by a shift toward greater predominance

of positive emotions, such as feelings of calm and joy, and a corresponding decrease in negative

emotions like anger, anxiety, disgust, fear and sadness (Carson, Carson, Gil, & Baucom in press;

Salzberg, 1995).

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 16

Positive emotions

Science suggests that when we experience genuine, heartfelt positive emotions in a 3-to-1 ratio with negative emotions, we cross a psychological tipping point on the other side of which we function at our very best.

~Barbara L. Fredrickson~

Negative emotions are “all about me”. In contrast, positive emotions free the self from itself

(Vailliant, 2008). Mentors when properly trained can help to create very specific interpersonal conditions –

empathy, congruence, hope, unconditional positive regard and respect. As a direct outgrowth, the

learning community becomes an environment in which youth can become more empowered, self-

expressive, and creative. As their locus of evaluation and control becomes increasingly internal, they

experience their own ‘inner self’ as a trustworthy source of guidance, value, and action (Rogers, 1980;

Bowen, Justyn, Kass, Miller, Rogers, & Wood, 1978).

Helping youth with emotional and behavioral difficulties begins with understanding ourselves as

coaches, examples, helpers and mentors, particularly our own emotional processes that occur in the

midst of conflict. Although psychological soundness and effective interpersonal skills are essential

characteristics for teachers who work with this population (Kaufman, 1997; Webber, Anderson, & Otey,

1991), certain students can provoke even the most concerned, reasonable, and dedicated teachers to act

in impulsive, acrimonious, and rejecting ways (Long,1996a).

Awareness of our primary emotional triggers improves our chances of making rational decisions

based on conscious choice, rather than unconscious emotional conditioning.

The ten (10) principles that will guide this mentoring program of humility and humanity consist of an

ongoing commitment to doing the following:

1. Teach freedom of religious and spiritual expression and the rights of all individuals and peoples

as set forth in international law. (United Religions Initiative URI CHARTER, 2003)

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 17

2. Affirm the importance of meaningful dialogue and how it can be created with science and other

areas of modern knowledge and global concern such as contemplative education, ecology,

morality, the peace movement, human rights and holistic psychology; (Laurence Freeman OSB,

2002)

3. Review how to avoid ‘advocacy tendencies’ in order to engage fully in inquiry modes of

relationship; When balancing advocacy and inquiry, we lay out our reasoning and thinking, and

then encourage others to challenge us. Here is my view and here is how I have arrived at it. How

does it sound to you? What makes sense to you, and what does not? Do you see any ways in

which we can make improvement? Dialogue provides a way to test the truth of alternative theses

by allowing the participants the opportunity to test their fit within each participant's thought

system. (Knitter, 1985, p.219)

4. Model building blocks of behaviors and actions that can lead to authentic, bold, empowering,

respectful and committed relationships that open the mind, open the heart and serve to establish

community;

5. Demonstrate effective and attentive listening skills to; a) self; b) others, c) Inner Guidance and d)

Outer Community Guidance;

6. Investigate the idea that inner change presumes outer changes: i.e., seek to change oneself

before wanting or expecting to change others; (Fr. Greg Boyle)

7. Honor a simple ground rule: “no fixing, no saving, no advising, and no setting-straight”; (Palmer,

2004)

8. Present the idea of a spiritual presence that does no harm to the dignity and preciousness of

others. Organize a Sacred Text Reading Group for multi-layered conversation between the

participants and the texts. (United Communities of Spirit: World Scripture A Comparative

Anthology of Sacred Texts Dr. Andrew Wilson, Editor International Religious Foundation, 1991)

9. Equip youth to describe and support their visions of the purpose of human existence, ultimate

reasons for leading a moral life. Assist youth experiences and understanding of how religious

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 18

history, traditions and rituals, sacred images, authentic speech and the honoring of others

integrate into the fabric of personhood, family, community, culture, and national and global living.

10. Explore the spiritual dimensions of constructive and fair conflict negotiation and resolution.

Dialogue has become a real necessity in order to be able to coexist peacefully and to cooperate

effectively in areas of shared economic and political interest. (Jones, 1999, p.381)

Self-understanding and resiliency

“To see the Divine in all things is to begin to live, to begin to be awake and aware.”

How can a person become more spiritual and what is the result? Comparing biblical affirmations,

the views of Trappist monk Thomas Merton, of psychologists Han de Wit and Stanislav Grof, together

with those of Jane Loevinger and Robert Kegan, we see striking commonalities: (1) developing spirituality

is a lengthy, difficult process; (2) it leads to more humanness, to increased clarity of mind, to a

transformation of the self. Others gain importance in one’s own eyes, and one self becomes less

important, yet one understands oneself better. One acquires greater realism with respect to oneself and

the environment strengthens their willingness to be more open to self-examination. There is an

increasing recognition of other’s needs, the readiness to contribute to their satisfaction even if that means

to change and engage oneself more in a larger cause of a religious or a ‘nonreligious’ nature which

involves a non-egocentric enlargement of personal identity (Reich, 2001).

As evangelicals of transformational “life ways”, we are committed to providing programming

designed for and dedicated to youth with emotional and behavioral difficulties from all Faith-Oriented

Spiritual Practices, Eastern Spiritual Practices, New Age Spiritual Practices and Indigenous Spiritual

Practices around the globe. The support requirements to accomplish our mission are resource-intensive,

(they must also be diverse, accessible and respectful and sensitive towards others) involve multiple

modalities, and are largely relationship-based. Most significant of all, the benefits and lasting changes in

the well-being of the program recipients occur over a long period during which youth will have the

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 19

opportunity to form their religious and moral values, worldviews, and become exposed to different

experiences.

How do we practice and reflect on our actions and behaviors?

The process of personal devotions, prayerful meditation and religious fervor and experience also utilizes the same attachment elements that help create new neural pathways responsible for emotional modulation and mastery (Siegel, 1999). Self-regulation, which is seen as fundamentally emotion regulation, is the essence of spiritual development. “Emotional communication whether with one’s parents or the object of one’s devotions in prayer is the fundamental manner in which one mind connects with another” (Siegel, 1999).

Meditating, yoga, fasting, walking a prayer circle, making a pilgrimage, taking the sacraments,

singing with a choir, going on a weekend retreat, listening to the words of inspired speakers, lighting

Advent or Hanukkah candles, saying daily prayers, and contemplating a sunset or a mountaintop view are

all examples of religious or spiritual practices. Many of us use these practices in our daily lives, at special

seasons of the year, or maybe just once in a lifetime. Some practices begin early in life and stretch back

to our childhoods, while still others emerge in adolescence and young adulthood, representing new paths.

What all of these practices have in common, however, is the way in which they integrate different

aspects of our human experience – our emotions with our intellect or our minds with our bodies – while

also connecting us with others who share similar beliefs. We seek out these experiences, which are

special and set us distinctly apart from our mundane and ordinary daily lives. These experiences lift us up

out of our narrow selves and give us a glimpse – if only temporary – of another way to view things as a

part, however small, of a larger picture. Religious and spiritual practices help us integrate the body, mind,

and spirit.

Beginning with adolescence, we find that rituals or rites of passage practiced by many of the

major world religions play an important role in assisting individuals in successfully passing from one

phase of life into the next. Most of these transitions – baptisms, circumcisions, confirmations, coming-of-

age rituals, and marriages – occur early in life. However, what makes these religious traditions relevant to

health, especially in adolescence and early adulthood, is that they provide rules for living. For example,

some religions have very particular rules about diet and alcohol use, and most faiths have beliefs about

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 20

maintaining the purity of the body as the vessel of the soul. In general, religious faiths discourage self-

indulgent behaviors and promote “moderation in all things,” if not actual asceticism. Many spiritual and

religious practices, in fact, involve the temporary and intermittent, or in some cases, lifelong denial of

behaviors that are considered pleasurable by most people, such as drinking, eating meat, or having sex

(Spirituality in Higher Education Newsletter February 2008 Volume 4, Issue 2 Page 2).

Spiritual and religious practices predominantly represent highly constructive, virtuous pursuits,

and accepted preferences and values. They most favorably contribute to right behavior, social harmony,

and the collective ordering of family and community life. Researchers from the University of Michigan

analyzed data from an annual survey of high school seniors from 135 schools in 48 states in a study

called ‘Monitoring the Future’ (Wallace and Forman, 1998). The study findings show religious involvement

to have had a large impact on the lifestyles of the students in the study. Especially in late adolescence:

Students who say that religion is important in their lives and attend religious services frequently, have

lower rates of cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and marijuana use, higher rates of seat belt use, eating

fruits, vegetables, and breakfast, and lower rates of carrying weapons, getting into fights, and driving

while drinking. This is one of the few studies that have examined religiousness, spirituality, and health-

related practices in adolescence. More importantly, these findings demonstrate the origins of a healthy

adult lifestyle. Not smoking in adolescence, for example, dramatically reduces the likelihood that one will

ever smoke; it also reduces the exposure to related risk factors that cause heart disease, cancer, and

stroke, which all are major causes of death in our society.

In general, The Winds beneath Youth’s Wings program participating youth, their parents,

mentors, program instructors, and administrative staff alike are all expected to make a strong effort to

include the following practices in their daily lives:

1. Dialogue with others visiting each other’s sacred sites (i.e., mosques, synagogues, churches

and temples), simply meditating together, working together in the cause of reconciliation and

peace; (Freeman, OSB, 2002)

2. Learn to read, write and recite Hebrew, Hindu, Greek, Sanskrit, Arabic, and other sacred

texts

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 21

3. Welcome the spiritual education of the heart; Individuals do not simply conform their

consciousness and action to moral orders like chameleons changing color to match their

environment. Rather human beings internalize moral directives and orders in their subjective

inner worlds of identity, belief, loyalties, convictions, perceptions, interests, emotions, and

desires (Smith, 2003).

4. Become detectives for the presence of divinity (Anderson & Reese, 1999);

5. Set youth self awareness marks high, the higher the aim the higher they’ll reach;

6. Learn perseverance in your spiritual development and in your gaining of wisdom;

7. Gain an understanding about any past errors and sorrows;

8. Become the change that you wish to see in the world (Mahatma Gandhi);

9. Participate in inter-religious encounters as a celebration in the oneness of the “Holy Spirit”;

10. Work on interfaith projects locally, nationwide and internationally and thereby increase the

strength of the ties that bind us together; Train in contemplative education, authentic

leadership, interfaith dialogue, and the World Café´ conversational process for evoking

collective intelligence, and creating actionable results. (Co-founders Juanita Brown and David

Isaacs); and Become familiar with best practice to bring oneself into a harmonious or

responsive relationship with others.

What are the benefits of spiritual development?

It is possible to hold oneself in this very world, with all its challenges, in such a way that we are neither seduced into addiction by pleasure nor frightened into loathing by pain, and all mental states are characterized by an attitude of generosity, kindness, compassion, joy for the well-being of others, and a deep, penetrating wisdom that sees all things just as they are.

~Andrew Olendzki~

‘If there is a God,’ says Pascal, he is infinitely beyond our comprehension … and hence we are incapable of knowing either what he is or whether he is. And since reason cannot settle the matter, we have to make a practical choice, a choice on which our ultimate happiness depends.

~John Cottingham~

In the United States, highly religious people tend to live longer, have fewer health and mental

problems, steal less, volunteer more time, and give away more money than others. Even when other

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 22

relevant factors are controlled for statistically, these differences persist. Moreover, in many cases the

religiosity of the community influences these factors as much as the religiosity of individuals. Thus, there

seems to be a communal product that goes beyond individual religiosity (Woodberry, 2003).

According to Laurence Iannacone (1990), “just as the production of house hold commodities was

enhanced by the skills known as human capital, the production of religious practice and religious

satisfaction was enhanced by religious human capital. He defined religious human capital as skills and

experiences specific to ones religion, including religious knowledge, familiarity with church ritual and

doctrine and friendships with fellow worshippers (Finke, 2003).”

Religious organizations are repositories of financial, human, social and cultural capital, but they are

also sources of moral teachings and religious experiences that may motivate, channel, and strengthen

the people to reach particular ends (Finke, 2003).

The Winds beneath Youth’s Wings: A Mentoring Program of Humility and Humanity aims to establish

the following common set of universal meta-consciousness perspectives, spiritual activities, emotional

awareness and behavioral discipline, and practices widely known for their ability to enhance human

consciousness, spiritual growth, bio-psychosocial maturity and transformation.

1. Right View is the cognitive aspect of wisdom. It is simply to see things as they really are.

However, until we have completed all the steps, we do not have ‘Right View’. This makes forming

Right View extremely hard. Right View requires more than a simple knowledge. It requires us to

see through the confusion, to understand. To do so, we must begin with a sense of unknowing

(Varey, 2005).

2. Recognition of the need for and the value of having a moral operating system; Right Intention is

the purposive and volitional aspect of wisdom. It involves letting go of desire, deciding to have a

positive intention and intending to do no harm. (Varey, 2005)

3. Understanding that spirituality develops across the lifespan, Right Speech is the first of the moral

discipline steps. Right Speech recognizes that our words can cause harm, to ourselves and to

others. This can occur even if our intention is good. While we must avoid voicing slanderous,

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 23

harsh or idle opinions, to have Right Speech, we must also abstain from false speech. (Varey,

2005)

4. Define an individually constructed, culturally based cognitive system that focuses ones choice of

activities and goals, and endows their life with a sense of purpose, personal worth, and fulfillment

from a variety of sources; achievement, dialogue, relationship, religion, self-transcendence, self-

acceptance, intimacy, and fair treatment; Right Action is the moral discipline that reflects that

thought is made visible by deed. Right action involves not taking that which is not given and is

therefore not yours to take. Right actions lead to the right results, without unintended

consequences. (Varey, 2005)

5. Establish relationships with others and connectedness to something that youth can look to for

support in dealing with many of the tough issues that they will face; Right Livelihood is the third

moral discipline. It recognizes that a livelihood should be obtained, but not as to violate the

principles of Right Speech (deceit) or Right Action (illegality). Right Livelihood should not cause

suffering to others. (Varey, 2005)

6. Identify substantive personal beliefs and strategies that have relevancy in youth’s day-to-day

living and hold generative principles that are common to all spiritual, transforming experiences,

regardless of denomination or a particular religious faith; Right Effort is the first of the three

concentration paths. Right Effort is the mental discipline of applying yourself to the things that

matter most and avoiding the things that distract. It requires us to work with unflagging

perseverance. Quick results although easily gained are easily lost. Focus and diligence are

boring. They are however, necessary if we are not to adopt a false view too soon. (Varey, 2005)

7. Commitment to being accountable, responsible to the needs of others and in discerning what is

the loving and or right thing to do in most situations; and when unsure to have the self-

confidence, trust and determination to seek wise counsel from others; Right Mindedness is the

second of the mental disciplines. It is when we become conscious of our own mental processes.

The insight within us is ours to discover when we do not accept the authority or faith of others and

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 24

find it ourselves. Right Mindfulness is the presence of mind, attentiveness, and awareness

allowing us to know our own mind before attempting to know that of another. (Varey, 2005)

8. Recognize and accept that spirituality is worth contemplating and discussing as a deep human

concern, whether it is part of a specific faith tradition; Right concentration is the final step.

Through a strong awareness, it directs us to the subject of our focus to fully cognize the object.

Right Concentration is not simply about focus, it requires a wholesome focus that collects the

dispersed and dissipated streams into unification at a higher level of awareness. It requires us by

our concentration to shift our view. (Varey, 2005)

9. Willingness to help when help is needed and especially to look out for the physical safety of one

another’s children, women, gay, lesbian, or transgender, and the disabled, poor and the elderly

among us (Dunnemann, 2009)

10. Right Livelihood is the third moral discipline. It recognizes that a livelihood should be obtained,

but not as to violate the principles of Right Speech (deceit) or Right Action (illegality). We are to

obtain Right Livelihood in a way that does not cause suffering to others. (Varey, 2005)

11. Recognize and embrace the need to build a collaborative foundation, and creative partnership

among families, practitioners, and researchers (Dunnemann, 2009).

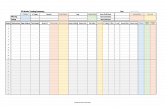

What are the selected measurement tools for data gathering and analysis?

Over the long term, what experiences and pathways lead to positive outcomes?

The Winds beneath Youth’s Wings program researchers will investigate whether or not youth

program participation produces the abovementioned outcomes, contributes to improved spiritual health

and well-being, and moves one towards a more integrated worldview through use of one or more of the

following Strengths-Based Assessment Instruments.

1. The Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue): The Trait Emotional Intelligence

Questionnaire (TEIQue) is an integral part of the scientific research program on trait emotional

intelligence. The TEIQue LF is a self-report inventory that covers the sampling domain of trait EI

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 25

comprehensively. It comprises 153 items, measuring 15 distinct facets, 4 factors, and global trait

EI (Petrides, & Furnham, 2003).

2. The Spirituality and Resilience Assessment (SRA) Packet: The Spirituality and Resilience

Assessment Packet (SRA) provides a simple, structured method for adults, teenagers, and

families to identify resilient and self-defeating aspects of their worldview whether their spirituality

contributes to their resilience the potential value of spiritual and psychological growth. It is an

excellent tool for generating concrete conversations about these complex topics. Most often,

clergy, health professionals, and educators use the SRA as a psycho-educational aid during

counseling with individuals, families, and groups. However, individuals and families who are

engaged in a process of psychological and spiritual growth can use the SRA by themselves. The

SRA has a self-scoring format. This empowers individuals to assess their own strengths and

weaknesses, and to engage in self-directed learning.

3. The Review of Personal Effectiveness and Locus of Control (ROPELIC) Instrument: ROPELIC is

a comprehensive instrument for reviewing life effectiveness. ROPELIC items are self-perceptions

but are expressed and interpreted in terms of behaviors. The ROPELIC has 14 scales; including

personal habits and beliefs (Self-Confidence, Self-Efficacy, Stress Management, Open Thinking),

social abilities (Social Effectiveness, Cooperative Teamwork, Leadership Ability), organizational

skills (Time Management, Quality Seeking, Coping with Change) and ‘energy’ scale called Active

Involvement and a measure of overall effectiveness in all aspects of life.

4. Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments (ASPIRES): The ASPIRES is available in

both a self-report and observer-rating forms. Each scale contains 12 items relating to Religious

Sentiments and 23 items concerning Spiritual Transcendence. There are also short form versions

of these two instruments. The short form contains 9 transcendence items and 4 religiosity items.

The scale has received extensive evaluations of psychometric robustness in a wide range of

samples, including college students, adults, medical patients, and treatment seeking substance

abusers and gamblers. The scale has been used in cross-cultural samples (India, Mexico, and

the Philippines). The ASPIRES is also the only spiritual inventory that has a validated observer

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 26

form.

5. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS): The DERS is a brief, 36-item, self-report

questionnaire designed to assess multiple aspects of emotion dysregulation. The measure yields

a total score as well as scores on six scales derived through factor analysis:

1. Nonacceptance of emotional responses (NONACCEPTANCE)

2. Difficulties engaging in goal directed behavior (GOALS)

3. Impulse control difficulties (IMPULSE)

4. Lack of emotional awareness (AWARENESS)

5. Limited access to emotion regulation strategies (STRATEGIES)

6. Lack of emotional clarity (CLARITY)

What challenges lie ahead?

The peril that earth finds herself in today is enough to motivate all of us as individuals and all of our communities of faith to lament our ways and transform our hearts and actions (Fox, 2000).

At every level of society, particular situations make or break the lives of children, adolescents and

young adults: situations of violence, loss, indifference and hatred. (Titus, 2002) Youth today find

themselves challenged by consumerism, cruelty, lack of integrity and respect, greed, homophobia,

ecological degradation and environmental vandalism resulting from the “looking out for me 1st” syndrome.

In the corporate world, the conscious less interest in profit maximization and achievement of the highest

return to shareholders, paid-out bonuses, general insensitivity, injustice, materialism, broken promises

and the recurrence of brutal wars negatively affects everyone on some level.

Education has to face up to this problem now more than ever before as a world society struggles

painfully to be born. Education is at the heart of both personal and community development; its mission

is to enable each of us, without exception, to develop all our talents to the full and to realize our creative

potential, including responsibility for our own lives and achievement of our personal aims (UNESCO,

2009).

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 27

This aim transcends all others. Its achievement, though long and difficult, will be an essential

contribution to the search for a more just world, a better world to live in (UNESCO, 2009).

The Winds beneath Youth’s Wings: A Mentoring Program of Humility and Humanity aims to

strengthen youth’s resilience in three domains; first, to cope with hardship; second, to resist the possible

deformation of the competencies and integrity of one’s community, family and self; and third, to achieve a

new proficiency out of their unfavorable experiences. Resilience outcomes indicate to us how

developmental and resilience tutors (aids that promote resilience) require, more often than not, growth

through affective, intellectual and spiritual trials. They involve keeping in contact with our larger goals,

while grappling with intermediate ones (Titus, 2002).

Listed below are just some of the more widely publicized negative outcomes that today’s youth

encounter at various levels.

National Level

• Disregard for decency

• Domestic violence against women and children

• Growth in hate crimes and cynicism

• Media portrayal of sex and violence

• Low neighborhood attachment and community disorganization

• Neglectfulness in providing spiritual and civil ethics/guidance

• Acceptance of extreme anti-social and co-dependent dynamics

Family Level

• Family conflict, discord and failure

• Disconnected relationships, lack of meaning and joy

• Persistent anti-social and co-dependent dynamics within families

School Level

• Early and persistent anti-social behavior

• Academic failure beginning in the late elementary school

• Lack of commitment to school and low expectations

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 28

Individual/Peer Level

• Alienation, physical aggression, and rebelliousness

• Poor self-image and lack of self-esteem

• Withdrawal from social engagement and polarization

The Winds beneath Youth’s Wings mentors receive 100 hours of formal training over the course

of 10 weeks on how to engage youth in the establishment of their personal hopes, concerns, wishes,

experiences and priorities, and worldview.

Conclusion

Martin Seligman, a University of Pennsylvania psychologist, proposed: “For the last thirty of forty years we’ve seen the ascendance of individualism and a waning of larger belief in religion, and in supports from the community and extended family. To the extent [that] you see a failure as something that is lasting and which you magnify to taint everything in your life, you are prone to let a momentary defeat become a lasting source of hopelessness. But if you have a larger perspective, like belief in God and in afterlife, and you lose your job, it’s just a temporary defeat.” (Goleman, 1995, p.241).

Adolescence is often a stressful period during development because it involves a pivotal

transition from childhood dependency to adulthood interdependency and self-sufficiency (Smith, Cowie, &

Blades, 1998). One major challenge that adolescents encounter during their teenage years involves

acquiring a sense of personal agency in what often seems to be a recalcitrant world. Personal agency

refers to one’s capability to originate and direct actions for given purposes. Generally, this centers on the

belief in one’s effectiveness in performing specific tasks, which is termed self-efficacy, as well as by one’s

actual skill (Pajares, & Urdan, 2006). People with high self-efficacy choose to perform challenging tasks.

They set themselves higher goals and tend to stick to them. The Winds beneath Youth’s Wings helps

adolescents in crossing over from adolescence to young adulthood through an outcome oriented process

that encompasses a broad array of methods for reflection, open discussions, journaling and poetry, studio

art, performing arts and film, music and nature where together we are able to explore the distinctive

characteristics of religion and spirituality. Our intention is to provide strong framework for the process of

internal transformation, personal improvement, spiritual practice (“praxis”), and successful transition of

youth with EBD who have previously fallen off track so that they can grab a firm hold, regain their footing,

and more effectively step into their chosen field of desired living.

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 29

The value of a religious experience is independent of whether it is given a naturalistic or theistic explanation. That value is to be ascertained by looking at its consequences.

Similiarly,…, despite what they might say, people don’t judge a religious doctrine, practice, or experience by its origin, but by its fruits. The consequences of a belief or practice include not only what we might ordinarily call practical consequences, but also its fruitfulness for contributing to an understanding of the world.

~William James~

Clearly, it is possible to create learning communities of adolescents and young adults from

diverse religious and cultural backgrounds and explore the potential value of spiritual transformation in

their lives. The Winds beneath Youth’s Wings is committed to enriching such a community by establishing

an individualized, developmentally appropriate process to foster dialogue, healthy relationships, unify

‘spirit’, and promote positive emotions and religious ‘praxis’ (Cottingham, 2005) and observance within

youth with EBD.

The spirituality education methods that will be used include the following:

i. Case presentation and discussion

ii. Essay reflective writing or discussion or story-telling

iii. Experiential exercises on spiritual practice and well-being

iv. Panel of invited discussants for question/answer sessions

v. Self-study (readings)

vi. Shadowing a mentor or spiritual practitioner

vii. Small group discussion/seminar

viii. Retreat

ix. Taking a spiritual history on oneself

x. Watching a video on a person giving their spiritual history

‘‘‘ NNN GGG ooo ooo ddd CCC ooo mmm ppp aaa nnn yyy ––– AAA sss ppp iii rrr iii ttt uuu aaa lll lll yyy eee mmm eee rrr ggg iii nnn ggg eee nnn ttt eee rrr ppp rrr iii sss eee Page 30

“Given sufficient support humans can defy the odds and become agents of history”

(Ramphele, 2002, p.123)

References

Books

Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man’s Search for Meaning. Massachusetts: Beacon Press. Fromm, E. (2006). The Art of Loving. Harper Perennial Modern Classics Goleman, D., Small, G., Braden, G., Lipton, B. & McTaggert, L. (2008). Measuring the Immeasurable: The Scientific Case for Spirituality. Colorado: Sounds True Incorporated. James, W., (2004). The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Barnes and Noble Classics. Kornfield, J. (1995). The Eightfold Path for the Householder. Berkeley, CA: Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. Lerner, R.M., Alberts, A.E., Anderson, P.M., & Dowling, E.M. (2006). The Handbook of Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence – On Making Humans Human: Spirituality and the Promotion of Positive Youth Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. Niebuhr, G. (2008). Beyond Tolerance: How People Across America Are Building Bridges Between Faiths. New York: Penguin Books. Rodgers, C. R. (1989). On Becoming A Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. Tallmadge, J (1997). Meeting the Tree of Life – A Teacher’s Path. Utah: University of Utah Press, Whitehead, A.N. (1996). Religion in the Making. New York: Fordham University Press. Walsh, R. (1999). Essential spirituality: The 7 central practices to awaken heart and mind. New York: Wiley & Sons. Journal Articles

Chandler, C. K., Holden, J. M. & Kolander, C. A. (1992) Counseling for Spiritual Wellness: Theory and Practice. Journal of Counseling and Development Volume 71, 168-175. Cottingham, J. (2005). The Spiritual Dimension: Religion, Philosophy and Human Value. Cambridge University Press p. 1-6. Dunn, T. (2005) Living Wisdom. www.poetrybytroy.com/Living_Wisdom.pdf Ellis, A. (2000). Can Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) Be Effectively Used With People Who Have Devout Beliefs in God and Religion? Albert Ellis Albert Ellis Institute for Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy, Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. American Psychological Association, Inc. Vol. 31, No. 1, 29-33.