The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

-

Upload

nuttynena5130 -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

1/28

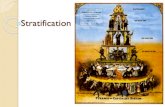

The traditional social stratification in Maharashtra was governed by Varnashrama dharma,t that is the division of society into an unequal hierarchical order comprising Brahmins,Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and Sudras. The social interaction between different castes governed

by this stratification was maintained by strict rules of pollution and purity. At the top, wasI the Brahmin caste with many rights and privileges which maintained their social controlover society by developing a religious ideology which gave legitimacy to many

superstitions and inhuman practices. At the lowest end were the Ati -Sudras or untouchableoutcastes deprived ofeducation and all other rights.In Maharashtra the Hindus were 74.8 per cent of h e total population. According to theCensus of 1881, the Kunbis or Marathas were the main community about 55.25 per cent of the total population. Kunbis were also economically powerful in rural society. Being a rich

peasant class they controlled agricultural production. However, the influence of thetraditional ideology and the institution of caste made them subservient to the Brahmins.The Brahmins, on the other hand, exercised considerable influence over other castes due totheir ritualistic power and monopoly over learning and knowledge. During the British

period the Brahmins successfully adopted the new English education and dominated thecolonial administration. The new intelligentsia therefore, came mostly from the alreadyadvanced Brahmin caste, occupying strategic positions as officials, professors, lower

bureaucrats, writers, editors or lawyers. This created fear among the non -Brahmin castes.It was this traditional social order which came under heavy fire both from The Christian

missionaries and the nationalist intelligentsia that had imbibed western liberal ideas. Wecan divide the reform movements into two distinct strands. The early radical reforms likeJotirao Govindrao Phule tried for a revolutionary reorganisation of the traditional cultureand society on the basis of the principles of equality and rationality. The later moderatereformers like Mahadev Govind Ranade (1842-1901), however, gave the argument of areturn to the Dast traditions and culture with some modifications. It was the earlv radical

tradition of Phule which gave birth to the non-Brahmin movement in Maharashtra.

In any case, the British administrators were, understandably overwhelmed by these figuresand felt obliged to find a way to compartmentalize chunks of population into manageablegroups. The most obvious way to do so was through the use of India's unique caste system.

The caste system had been a fascination of the British since their arrival in India. Comingfrom a society that was divided by class, the British attempted to equate the caste system tothe class system. As late as 1937 Professor T. C. Hodson stated that: "Class and caste stand toeach other in the relation of family to species. The general classification is by classes, thedetailed one by castes. The former represents the external, the latter the internal view of thesocial organization." The difficulty with definitions such as this is that class is based on

political and economic factors, caste is not. In fairness to Professor Hodson, by the time of his writing, caste had taken on many of the characteristics that he ascribed to it and that his

predecessors had ascribed to it but during the 19th century caste was not what the British believed it to be. It did not constitute a rigid description of the occupation and social level of a given group and it did not bear any real resemblance to the class system. However, this will

be dealt with later in this essay. At present, the main concern is that the British saw caste as away to deal with a huge population by breaking it down into discrete chunks with specificcharacteristics. Moreover, as will be seen later in this paper, it appears that the caste systemextant in the late 19th and early 20th century has been altered as a result of British actions sothat it increasingly took on the characteristics that were ascribed to by the British.

One of the main tools used in the British attempt to understand the Indian population was thecensus. Attempts were made as early as the beginning of the 19th century to estimate

populations in various regions of the country but these, as earlier noted, weremethodologically flawed and led to grossly erroneous conclusions. It was not until 1872 that

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

2/28

a planned comprehensive census was attempted. This was done under the direction of HenryBeverely, Inspector General of Registration in Bengal. The primary purpose given for thetaking of the census, that of governmental preparedness to deal with disaster situations, was

both laudable and logical. However, the census went well beyond counting heads or evenenquiring into sex ratios or general living conditions. Among the many questions wereenquiries regarding nationality, race, tribe, religion and caste. Certainly none of these things

were relevant to emergency measures responses by the government. Further, neither thenotion of curiosity nor planned subterfuge on the part of the administration suffices to explaintheir inclusion in the census. On the question of race or nationality it could be argued thatthese figures were needed to allow analyses of the various areas in an attempt to predictinternal unrest. However, there does not appear to have been any use made of the figuresfrom that perspective. With regard to the information on religion and caste, the same claimcould be made but once again there does not appear to have been any analyses done with thethought of internal disturbance in mind. Obviously there had to be some purpose to thegathering of this data since due to the size of both the population and the territory to becovered, extraneous questions would not have been included due to time factors. Therefore,there must have been a reason of some sort for their inclusion. That reason was, quite simply,the British belief that caste was the key to understanding the people of India. Caste was seenas the essence of Indian society, the system through which it was possible to classify all of the various groups of indigenous people according to their ability, as reflected by caste, to beof service to the British.

Caste was seen as an indicator of occupation, social standing, and intellectual ability. It was,therefore necessary to include it in the census if the census was to serve the purpose of givingthe government the information it needed in order to make optimum use of the people under its administration. Moreover, it becomes obvious that British conceptions of racial puritywere interwoven with these judgements of people based on caste when reactions to censusesare examined. Beverly concluded that a group of Muslims were in fact converted low casteHindus. This raised howls of protest from representatives of the group as late as 1895 since itwas felt that this was a slander and a lie.H. H. Risely, Commissioner of the 1901 census, alsoshowed British beliefs in an 1886 publication which stated that race sentiment, far from

being:

Here is a prime example of the racial purity theories that had been developing throughout the19th century. Here also is the plainest explanation for the inclusion of the questions on race,caste and religion being included with the censuses. Thus far this essay has dwelt almostentirely with British actions to the exclusion of any mention of Indian actions and reactions.This should not be taken to mean that the Indians were passive or without input into the

process. Any change within a society requires the participation of all the groups if it is tohave any lasting effect. The Indian people had a very profound effect on the formulation of the census and their analysis. However, Indian actions and reaction must be considered

within the context of Indian history and Indian culture in the same way that British actionsmust be considered within British cultural context. For this reason, it has been necessary to postpone consideration of Indian reactions and contributions to the British activities until thenext section of this essay which will then be followed by a more in depth examination of thedevelopment of British attitudes. Finally, the results of the combination of both Indian andBritish beliefs will be examined with a view to reaching a consensus on how they affected thecompilation of and conclusions reached through the censuses.

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

3/28

The word caste is not a word that is indigenous to India. It originates in the Portuguese wordcasta which means race,breed, race or lineage. However, during the 19th century, the termcaste increasingly took on the connotations of the word race. Thus, from the very beginningof western contact with the subcontinent European constructions have been imposed onIndian systems and institutions. To fully appreciate the caste system one must step away fromthe definitions imposed by Europeans and look at the system as a whole, including the

religious beliefs that are an integral part of it. To the British, viewing the caste system fromthe outside and on a very superficial level, it appeared to be a static system of social orderingthat allowed the ruling class or Brahmins, to maintain their power over the other classes.What the British failed to realize was that Hindus existed in a different cosmological framethan did the British. The concern of the true Hindu was not his ranking economically withinsociety but rather his ability to regenerate on a higher plane of existence during eachsuccessive life. Perhaps the plainest verbalization of this attitude was stated by a 20th centuryHindu of one of the lower castes who stated: "Everything lies in the hands of God. We hopeto go to the top, but our Karma (Action) binds us to this level." If not for the concept of reincarnation, this would be a totally fatalistic attitude but if one takes into account the notionthat one's present life is simply one of many, then this fatalistic component is limited if noteliminated. Therefore, for the Hindu, acceptance of present status and the taking of ritualactions to improve status in the next life is not terribly different in theory to the attitudes of the poor in western society. The aim of the poor in the west is to improve their lot in thespace of a single life time. The aim of the lower castes in India is to improve their positionover the space of many lifetimes. It should also be borne in mind that an entire caste couldrise through the use of conquest or through service to rulers.Thus, it may be seen that withintraditional Indian society the caste system was not static either within the material or metaphysical plane of existence. With the introduction of European and particulary Britishsystems to India, the caste system began to modify. This was a natural reaction of Indiansattempting to adjust to the new regime and to make the most of whatever opportunities mayhave been presented to them. Moreover, with the apparent dominance exhibited by Britishscience and medicine there were movements that attempted to adapt traditional social systemsto fit with the new technology. Men such as Ram Mohan Roy, Swami Dayananda, andRamkrishna started movements that, to one degree or another, attempted to explore new pathsthat would allow them and their people to live more equitably within British India. Roy in

particular sits this description with his notion that the recognition of human rights wasconsistent with Hindu thought and the Hinduism could welcome external influences so longas they were not contrary to reason. While it is granted that the present paper is not theappropriate venue to explore such movements, they must be noted so that an impression of Indian submissiveness in the face of British intrusion may be avoided. There was a dynamicinterplay between the British and Indians that had a profound effect on both societies. Moreappropriate to the task at hand, however, are the reactions of various groups within India tothe census itself.

This is virtually a call for a public enquiry into what most westerners would consider arelatively minor matter of very limited concern.

A further example of Indian reaction to judgements made within the censuses becomesapparent from the claims of castes that they should have higher ranking following the censusof 1901.One claim in particular, that of the Mahtons, is of particular interest for the present

paper. The Mahtons claimed that they should be granted the status of Rajputs because of bothhistory and the fact that they followed Rajput customs. Therefore, since they had not receivedthis status in the 1901 census, they requested the change to be affected in the 1911 census.

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

4/28

Their request was rejected, not on the basis of any existing impediment but on the basis of the1881 census which stated that the Mahtons were an offshoot of the Mahtams who werehunter/scavengers. Thus, it appears that the census system had become self reinforcing.However, after further debate the Mahton were reclassified as Mahton Rajput on the basisthat they had separated themselves from the Mahtams and now acted in the manner of Rajputs. Interestingly, it was at this point that the reasoning behind the claim became evident.

Some of the Mahton wanted join an army regiment and this would only be possible if theyhad Rajput status. The Mahton, a rural agricultural group, were fully aware that the change of status would allow their members to obtain direct benefits. In and of itself, this definitelyshows that the actions of the British in classifying and enumerating castes within the censushad heightened indigenous awareness of the caste system and had added an economic aspectthat the Indian people were willing and anxious to exploit.

With this in mind, it is interesting to note that in doing the censuses, Indians were used as both census takers and as advisors regarding the caste system of hierarchy. Since it is verylikely that individual census takers filled out most of the data themselves, without consultingeach individual in the area, the possibilities for self serving activity was immeasurable.Moreover, those Indians who were used as advisors certainly had more than ampleopportunity to act in a manner that suited their own or their group's agenda since precedentwas based on interpretations of the writings of the various Hindu holy texts. To even amarginally cynical mind this would suggest immense possibilities for graft and corruption.This, in turn, suggests the possibility that the British were manipulated, at least to somedegree, by their mainly Brahman informants.

Contrary to what the British appear to have believed, it seems doubtful that the Brahmanswere dominant within the material world in pre colonial Indian society. A cursoryexamination of any of the ruling families quickly shows a dearth families of the Brahmincaste. Rather, one finds that the majority, though by no means all, of rulers were Kshytria andoccasionally Vashnia. This suggests that although the Brahmin caste had power in spiritualmatters, their power and control within the material world was limited to the amount of influence that they could gain with individual rulers. No doubt there were instances when thiswas quite considerable but there is also little doubt that there were times when Brahmaninfluence was very weak and insignificant. With this in mind, it is not difficult to imagine asituation where, Brahmans, seeing the ascendancy of British power, allied themselves to this

perceived new ruling class and attempted to gain influence through it. By establishingthemselves as authorities on the caste system they could then tell the British what they

believed the British wanted to hear and also what would most enhance their own position.The British would then take this information, received through the filter of the Brahmans, andinterpret it based on their own experience and their own cultural concepts. Thus, informationwas filtered at least twice before publication. Therefore, it seems certain that the informationthat was finally published was filled with conceptions that would seem to be downright

deceitful to those about whom the information was written. The flood of petitions protestingcaste rankings following the 1901 census would appear to bear witness to this. To fullyunderstand how the British arrived at their understanding of Indian society it will now benecessary to look at where British society was during the 19th century in both its concepts of self and of other.

At the beginning of the 19th century, society in Britain was still attempting to come to termswith the social structure that had developed within the British Isles. Symptomatic of this

phenomenon was the variation in terminology with reference to levels of societal existence

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

5/28

that was extant at this time. Phrases such as "gentlemen of wealth and property" and "thelower ranks from labour to thinking" were used to describe levels within society. While thisis not meant to suggest that the British did not recognize that there were stratifications withinthere society, it seems to indicate that there was an absence of the modern notion of class andclass structure. Instead, there appears to have been a linguistic shift occurring in which thevarious levels of society were being described in a variety of ways. Even within the two short

phrases quoted above, there is description of three different attributes; social standing,economics and intelligence. This may be seen as a reflection of the mobility that was beingexperienced within Georgian society itself as non aristocratic, non landed groups moved up inthe social order through the increase in industrialization. The use of the word "rank" itself indicates that the language had not entirely rid itself of feudal notions of high and low birth. Itis also interesting to note that the connection between social status and mental ability had

been made at this point in time. This tends to point toward the determinism that would later be seen in the works of phrenologists such as Spurzheim in which the inheritance of a givenskull shape determined the entire character and ability of both individuals and nations. Inturn, this deterministic attitude meshed well with later statistical ideas that human behaviour was caused and controlled by unvarying social laws and that free will was of little or noconsequence in the grand scheme of human progress.Therefore, it can be seen that as theBritish became increasingly entrenched in India, three distinct but inter-related intellectualmovements converged to provide the basis for British extrapolations and interpretations of Indian society. In this way, the British construction of Indian society was as much a reflectionof their own attempts to understand their own society as it was an attempt to reach anunderstanding about another society. The main key in the evolution of all of this was the useof statistics.

Statistics was initially used as a tool to understanding the present state of European society sothat power structures could make optimum use of resources during times of crisis and, in thecase of Britain, as an attempt to avoid the societal unrest that dominated Europe during thefirst half of the 19th century. "Statistics, by their very name, are defined to be theobservations necessary to the social and moral sciences, to the sciences of the statist, towhom the statesman and the legislator must resort for the principles on which to legislate andgovern." Thus, at the turn of the century, statistics were used to accommodate manpower demands for the armies to fight the continental war against Napoleon and later during the1830s, as a part of an attempt to control the population and avoid the turmoil that hadengulfed the European mainland. Initially, statisticians confined their activities to thecollection of raw data that was then used by others to form or confirm social theories.However, there was a desire on the part of statists to go further and to ground there newscience on the same sort of constant that the universal law of gravity had provided for astronomy. This inspired the French statistician Quetelet to formulate a model of probabilitythat he believed would give social scientists that same grounding.

Henry Thomas Buckle took this idea one step further. He believed that it was possible to gainaccess to the rules that operate the human mind through the use of statistics. Moreover, it wasBuckle's belief that all human behaviour was caused by unvarying social laws and that moralcauses were inherent to the nation, not to individuals. Buckles concept of mankind wasshaped by the belief that there was no place for chance or supernatural intervention inaccounting for the history and progress of mankind. All of history was the result of theuniversality of law. Within this viewpoint, Buckle saw corporate entities such as the churchor political in

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

6/28

AbstractEmpire has manifested in many forms, such as the impact of neo imperialism and neocolonialism in the economic sector as well as the dynamics between developing anddeveloped societies, it has also had far reaching effects on the shaping of organizations inother ways. Empire, imperialism and colonialism (Hardt & Negri ,2000) have had a historicalimpact on the development of several societies and systems. This paper explores the impact

inIndia in terms of the effects on organizational life.While the colonization of the Indian nation by the British is a historical fact, the impact of thiscolonization on the Indian psyche is far deeper and carries over even into the present day.(Nandy, 1983; Bhabha,1994; Spivak,1994 ). In this paper, I explore this impact in one

particular area of Indian social organization, the caste system, and how then this had an effecton organizations.The Caste SystemScholars studying caste have tended to agree that the presence of castes throughout thecountry is a universal feature (Dumo nt, 1970). The main form of the system has beendescribed as hierarchical polarity and institutionalized inequality (Dumont, 1970). It has

been argued that even though there are regional variations, the caste system in fact representsa uniform and universal ideology when applied to an understanding of Indian society. Thesystem or ideology of caste has a powerful influence in the conduct of economic life,therefore economic life in India is very much a part of the social system. A discussion of theconcepts of Sanskritization (Srinivas, 1989) and Westernization (Srinivas, 1955, 1962, 1998)throws light on how the British created an elite group of Indians in the civil services andadministration by aligning themselves with the uppermost caste in the hierarchy. This thenresulted in the capture of top positions by the upper caste, the Brahmins. However, even after Indias independence in 1947, this dominance of the Brahmins continued in terms of education, occupational and organizational privileges and performance.Sanskritization and WesternizationThe process of Sanskritization delineates a mode by which a lower caste moved up in thehierarchy by adopting some of the practices of the upper castes. Simultaneously, theBrahmins, whereby they imitated the British in their form of dress, education and other aspects, thus considering themselves superior to the rest of the people, adopted a process of Westernization.According to Srinivas (1955), the caste system is a dynamic system, and the fixed and rigidview of caste is problematic. Especially in the middle ranges of the caste hierarchy,movement upward was possible. A lower caste was able in a generation or so to rise upwardin the hierarchy by adopting the rituals and eating practices of the higher caste, such asvegetarianism. The Brahmanic way of life, the customs, rites and beliefs of the Brahmins wasadopted. This process has been called Sanskritization. The other process that went hand inhand with the process of Sanskritization was Westernization. The acceptance of Western

cultural ethos and ideas by upper caste Hindus and the process of imitation of British customsand habits was the main feature of this process. The upper castes had an advantage in takingto Western education because of a tradition of literacy. The kind of westernization that wastaking place in different parts of the country varied from one region to another. For instance,in some cases westernization was confined to the acquisition of western science, knowledgeand literature, while others adopted westernized styles of dress, speech, sports and gadgets.These congruent processes were two sides of the same coin. While the upper castes werewesternizing themselves, they were declaring themselves separate and distinct from the lower castes, which were becoming increasingly sanskritized. The effect was thus to increase the

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

7/28

gulf between the upper and the lower castes. The upper castes were brought closer to theBritish rulers, which gave them political and economic adva ntage. Thus, the social gap

between the lower and the upper castes remained, only the forms and manifestations of their practices and rituals changed.Caste and ReservationsThe caste system has been interwoven with the Constitution of India, and the legal position.

The historical background of the Scheduled Castes can be traced back to the Government of India Act, 1935. On the basis of social and economic disabilities and historical discriminationsuffered by certain groups because of their belonging to certain castes, they were placed inthelist of Scheduled Castes (Parvathamma,1984).When the reservation policy was started there was a rationale behind it. Reservations refers tothe practice of ensuring a certain percentage or quota of positions in jobs as well as in thecaseof admissions to educational institutions for persons belonging to the categories of BackwardClasses, as well as Scheduled Castes. The logic behind following this as a concerted programof action on the part of the government of India was based on the principle of social justiceand to set right the discrimination faced by these groups historically.The Constitution of India had provided for the idea of protective discrimination, or affirmative action for the sections of society that were traditionally faced with discriminationand with the burden of the past. As such, this resulted in the formation of the BackwardClasses Commissions. The first such Commission was headed by Kaka Kalelkar and thereport was tabled in 1955. The second Backward Classes Commission the MandalCommission was set up in 1979 and the report was finalized in 1980 The Commission wasalso to identify the reference points of backwardness as social and economic backwardness.However, the impact of this second Commission was rather severe. Everywhere in thecountry there were anti- reservation stirs. In some cases, the policy advocated almost 50%reservations in jobs and educational institutions for the backward section of society. Thisresulted in the backlash against the recommendations of the Commission by the upper casteswho felt marginalized. It also brought into the limelight the debate about merit versusreservations. That is, does reservations go against the concept of merit and due recognition

being given to the talented and deserving? (Chatterji, 1996).Caste in contemporary IndiaThe stronghold or dare we say stranglehold of caste continues not only in terms of itsvisibility in all facets of life, but in the form of social marginalization. Despite MahatmaGandhi's efforts to raise the status of the Untouchables by calling them Harijans , (the Hindiword which literally means people of god) the strength of caste as a way of social acceptanceand political identification continues. Legislation protecting the castes who were oppressedfor centuries has heightened the awareness of difference. "Caste is experienced not so muchas something which you ' do, as something which is 'done to you' by other (high caste)

people" ( Searle -Chatterjee and Sharma,1994:11).

The intertwining of the caste system with the political and economic life of Indian societycontinues. Thus, certain caste groups are the landholding sections of society and control powerful voting blocks in many of the regions in India. Further, when there is a concentrationof a particular caste group in an area especially in industry and commerce, there is a biastowards appointments and positions of managerial authority being made from the same group(Barnabas and Mehta, 1965).ConclusionIn essence, then, it is the main thesis, that while the caste system existed as a system of occupational division of labor, and later social inequality for centuries, the role of empire in

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

8/28

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

9/28

focussed on caste is a reflection of its importance in defining Indian political, economic andsocial life both historically and today. The caste system is an elaborate social and religioushierarchy which has been created through a wide range of factors including ritual, religion,culture, wealth, history, ethnicity, politics and is highly evasive and difficult to categorise. Itsinfluence on the lives of the Indian population also varies significantly depending on region,time period and to which level of caste an individual may belong.

The ambivalence of the caste system is clearly reflected in the literature that has attempted toexplain it. The essentialist outlook of the Orientalists sees caste as an inherent and clear characteristic of India defining the Indian experience caste and complex social hierarchiesagainst a background of perceived western rationality and stability. This view is rejected byother historians, Inden for instance, emphasizes what he calls the role of 'human agencies' inthe making of history; that is, the unbiased study of the dynamics of indigenous social,economic, religious, and political organizations and structures which are devised andimplemented by the Indians themselves.

The caste system and its role in British rule has been an area of considerable interest for historians. Some have seen caste as 'a modern phenomenon... the product of an historicalencounter between India and Western Colonial rule' (Dirks) whilst others have seen caste as ahistoric and deep rooted system; few modern historians, however, would claim that Britishrule did not have a lasting influence upon the crystallisation and continuation of caste inIndian society today. Susan Bayly makes two important observations on the development of amore 'caste-conscious' society. Firstly the broader context of social changes that wereunderway before the intervention of colonial rule and secondly that the development towardsa more rigid caste framework could not have taken place without active indigenous

participation For Bayly the study of caste must concentrate on the 'orientalism' introduced bythe colonists as well as material and political context underlying its basis. Dirks takes this astep further stating 'colonialsim made caste what it is today' by means of an 'identifiableideological canon' under British dominion.

Caste clearly plays an important role in Indian society a role that can be seen in the daily livesof may Indians from a range of regions and castes, from the 'untouchables' at the bottom endof the hierarchy who are excluded from various jobs and are often social outcasts andBrahmins at the other end of the scale who see elevated social status due to their caste rank.On a wider political level though it is clear that caste was used deliberately in order to gainand perpetuate power both on the part of the British administration and Indian collaboratorsand intermediaries. What had previously been a relatively fluid social and religious hierarchywas transformed into a means of political control. Caste, therefore, cannot be defined withoutsome understanding of preexisting social and religious conditions combined with a detailedexamination of the manipulation and modification, whether it was deliberate or not, of thehierarchical caste system by the colonial authorities.

Caste is the hierarchical social system of India comprised of the Varna and jati. Varna

is the spiritual hierarchy found in the sacred text of the Vedas which Hindus are born into. It

is comprised in descending rank of Brahman, kshatriya, vaiysha and shruda. Of the twice

born Varna, Brahmans were historically Hindu priests and learned men, kshatriya were

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

10/28

traditionally warriors and vaiysha were traditionally merchants and agriculturists. Shrudas,

the lowest caste are traditionally labourers. Within these broad categories of Varna, are many

sub-castes and these are referred to as jati. Jati are the groupings relating to kinship and

specific occupational heritages. Another social group called the untouchables are considered

too impure to be part of this hierarchy. They remain outcasts expected to work the most

impure jobs.

Caste had existed in Indian since the sacred texts were written. The sacred texts

describing castes rules and customs were of Vedic origin as well as later dharma texts of

Manu. The idea of Varna with Brahmans at the top came from the Manu texts. Although

caste had existed prior to British occupation, ideas of caste were expanded and sharpened

from the early nineteenth century because the British wanted to gain knowledge about Indian

customs. The British commissioned ethnographic studies as well as the first India wide

census in completed in 1872. The impetus behind the census was the Rebellion of 1857. The

thinking was that Indian subjects could be more effectively managed if they could be ruled

according to categories. This would allow for simplification of the administration and more

effective running of the colony. The British collected cultural data on Indians during the

census including caste name and Varna. Such classification proved to be contentious for

Indians who did not want to be valued according to their caste. Caste groups began

petitioning the government for what they believed to be their rightful place in the Varna

categories. This was the beginning of the emergence of caste consciousness initiated by the

British interest in defining caste and caste norms. In the census of 1901, the commissioner

H.H. Risley decided to rank each caste according to social standing. Such methods increased

the level of caste consciousness and more caste interest groups began to form to maintain or

assert a higher social position. From 1901, it could be said that caste politics became more

prevalent as castes began to assert caste identities and rights, and debates about how the

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

11/28

privilege of certain castes was directly related to the dominance and oppression of others.

Thus caste and especially untouchable uplift movements began, at the same time as Congress

was beginning to mobilize peasantry. The poor and oppressed castes opposed the dominance

of the British and the high castes such as the wealthy zamindars who were backed by the

British. Ultimately caste became a divisive force in Indian society, which gave the British the

upper hand. As Congress was supported by Brahmans and moneyed men, it had a

conservative backing who wanted to maintain the hierarchy of caste and caste rules. The

struggle over caste and caste identity persists to this day which owes a large part to the

reciprocal relationship of the British definition and policy on caste and the Indian response to

them.

What is Caste?

The word caste was first used by the Potugese to describe inherited class status in society, yetthe word is more commonly linked with India. Caste is a complex social system of occupation, endogamy, culture, social class and political power; however caste should not beconfused with class. Members of the same caste are deemed to be similar in culture, for example, however members of the same class are not.The Indian caste system illustrates the social hierarchy and social restrictions in which socialclasses are defined by many endogamous traditional groups, known as jatis, or castes. Withineach jati exists a exogamous group known as a gotra, which is the lineage or clan of anindividual.According to ancient Hindus scriptures, there are four varnas, which refers to the maindivision of Hindu society into four social classes; the Brahmans, the Kshattriyas, theVaishyas, and the shudras. Varnas are decided upon Guna (tendencies), and Karma (actions).Christians and Muslims as well as Hindus followed caste practises in India. Caste did not

include all members of society however; the untouchables, who worked in jobs that wereseen as unhealthy or polluted, were not allowed to worship at the same temples membersof castes, or collect water or eat from the same places. If a member of a higher caste cameinto contact with an untouchable, either physically or socially, they were said to be corrupted.The castes did not compose a firm description of the occupation or social status of a group.Since British society was divided by class, at the time of the Raj, the British attempted toequate the Indian caste system to fit their own social class system. Caste was seen as angauge of occupation, social standing, and intellectual ability. The caste system obtained a

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

12/28

much more rigid structure at the time of the British Raj, when the British started to cataloguecastes during the ten year census, and codify the system under the rule of the Raj. The censusin addition to the British policy of divide and rule were large contributors to the hardening of caste identities. The British tried to encourage caste privileges and customs in the beginningsof the East India Companys rule, but the law courts back in Britain disagreed with the

discrimination against lower castes, such as the untouchables.Prior to the Birtish, caste ranking differed from one place to another caste did not comprisea firm description of the social status or occupation of the group.In conclusion, caste cannot be confused with class due to the different specifics it includes.The British changed the caste system in India to their own means, the social and politicalsignificance was hardened.

What is Caste?

An enormous body of academic scholars have attempted to portray their understanding of what constitutes caste in a variety of ways. Studies by anthropologists and other socialscientists have provided a wealth of information, often conflicting, and published varioustheoretical manuscripts that leave a historian with an ambivalent understanding of what it wasto be a caste. Defined by many scholars as the system of an elaborate social hierarchy, basedon a variety of events and rituals that included praying at different temples and drinking fromdifferent water wells, defining what constitutes caste has antagonised the same level of heated academic debate as discussions between race.

Since the 1970s, revisionist scholars have questioned the traditional commentators on casteaccusing the earlier scholars of exaggerating the importance of caste on Indian society.Caste is a European word and an attempt to segregate Indian society into a more

controllable system of hierarchy in order to maintain more practical colonial control. Indefining various castes, some with more arduous qualities than others, Britain was able tolegitimise her role in India as one of helping a hopelessly chaotic India find some sort of democratic coherent rule. It seemed that caste hardened around British rule because prior to the formation of colonial authority Indian caste divide was indistinguishable. Thissuggest that instead of caste being an observable and physical phenomenon, one can look atthe influences on caste, like colonialism, and its ability to transform across various

provinces of India. Susan Bayly goes as far to question the very existence of a pan Indiancaste system, leading to the idea that the caste system was a colonial fabrication so datacollectors could quantify and rank Indian society conveniently.

Furthermore, from the nineteenth century onwards, colonial authority significantly expandedthe division of various social differences in India based around language and ideology thatwas suitable for a more stable British rule. The practises of representative government

became more deeply rooted in Indian society because they further enhanced the importanceof political affiliation based around particular collaboration of interests. The assertions of caste have made it possible for the British to build broad allegiances with the groups of society with the most similar of interests, promoting their way of life as pure in order to

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

13/28

establish an indigenous system of alliance. Yet at the same time, caste definitions have provided the means of excluding or subjugating those who did not conform to the particular interests of the ruling elite.

Thus, it seems that caste is generally a colonial interpretation of the social divisions in

India. Caste can be used as a way of British divide and rule (a term originally used for colonial activity in Africa but applicable here) so that divisions within Indian society reducethat threat of a pan Indian anti-colonial movement; something Gandhi tried to address in the1920s. It does seem however, that a uniform system if caste differentiation was almostimpossible in India because of the sheer scope and diversity of Indian society.

After the Great Rebellion of 1857, the colonial authorities in India realised that they need toform a fuller understanding of the Indian peoples in order to rule mor e completely. This ledto attempts to categorise the indigenous population on first a regional basis and, later, anational one. Without fully understanding the Indian principle of what they termed caste ,the British engaged in a continuous attempt to define, describe, interpret and

categorise . [1] It was this need to categorise that led the British to caste; and this increasedthe importance of caste greatly.

One of the reasons why caste became important in the late 19 th century is because it wasmade to seem important. The British related the census to the completion of imperialprojects; and, also, as a guide to which groups could be trusted. The British stimulated[competition] along communal lines; the prizes were government patronage, jobs andpolitical appointments . [2] This may suggest that it was not caste but the rewards on offerthat were more important originally. This is further suggested by the reaction of theKayastha s of Ajmere to General Order No. 9 of 1833. This classified the Kayastha s as lowcaste and excluded them from military service. Although the Adjutant -General offered toremove the word low from the classification, what they really want stated the KayasthaSamachar is that the orders about exclusion from the army should be withdrawn . [3] Thiswould suggest that it was the results of being considered a low caste rather than being of low caste itself that was the real issue.

C aste differences became important for the British over this period as they sought tovalidate their rule; often on racial grounds. As Dirks argues, caste was not only the centralmeans of colonial rule, it was also the dominant reason why colonial gover nance couldconceive of a limited future . [4] This suggests that by emphasising caste differences,colonialists would be able to impose racial superiority. This idea is further suggested byW.R. C ornish, Madras commissioner, who stated that the caste system had clearly beeninvented to prevent the mixture of the white and dark races . [5] As a result, the fair

Brahman caste was considered to be of the highest rank. This is a clear indication thatAryan racial difference was used to assert mastery over the indigenous population.

W. C . Plowden might have known that the whole question of caste is confused that hehoped that no attempt will be made to use it [6]; that did not stop it from becomingimportant in the late Victorian period. C aste became important as the colonialadministration needed a means to assert their superiority of Indians. They used caste todefine racial differences and to deicide who was worthy of their trust and privilege.

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

14/28

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

15/28

Caste in contemporary terms is viewed as the foundation of Indian identity. Caste originated as a formof hierarchy inherent in India, used to classify the different forms of stature in society. However, thiswas often at a local or regional level, and included a range of spheres without being confinedindividually to religion or basic social standing. However, the Colonial state changed thisphenomenon, distorting it into a category of social order used to exclude and justify Britishdominance.

Hence, Caste became the central symbol for India, used to portray its distinction from other cultures. Many historians view Caste as the basis of Indian society, whilst being described by Dirks asdefining the core of Indian tradition. Dumont states that hierarchy is the core value behind the Castesystem, providing a natural foundation of Indian society. He goes on to claim that it is a sign of Indiasreligiosity and depicts its separation from the West. Dirks however describes Caste as a moderntheory and the product of a historical progression between Indian society and the British colonialstate. Although rejecting the claim that Caste originated from British ideology, Dirks claims that under Colonial rule the symbol evolved into a single term to organize and explain Indias varied society.Thus, Britain projected an ideological canon onto India to aid Western understanding. Therefore,Dirks argues, Colonialism created the modern idea of Caste, alongside creating the necessaryconditions for this categorizing phenomenon to take shape.

The term Caste seems to originate from the Portuguese term Casta, used to refer to the socialorder in Britain. In the early sixteenth century the traveler Duarte separated the Indian social order

into three classes; the first contained the king, lords, knights and other fighting men, whilst the secondconsisted of Bramenes, the priests or rulers of houses of worship. Additionally, the Mughal rulers of India outlined the formal Varna scheme. The Brahmans constituted the first class, then the Ksatriyas,the Vaisyas and agriculturalists, and finally the sudras and servants. Additionally, all subdivisions fromintermarriages primarily originated from these categories. However, from 1870 Caste was interpretedas the primary form of social classification. After the mutiny, Britains need to understand India sociallyas well as economically grew, with a belief that rule would develop using anthropological knowledgeto attempt to understand the diverse communities. Thus, Caste was progressively institutionalized,becoming involved in the recruitment of soldiers and the implementation of legal codes, whilstcriminalizing entire Caste groups. Hence, Caste gradually became the modernist apparition of Indiastraditional self.

In modern terms, Caste remains dominant despite the more ostentatious conflict between Hindusand Muslims. Dirks puts forward the notion that Caste continues due to its predominant usethroughout History. Colonialism played a critical role in this, with Bernard Cohn claiming that Britainmisrecognised and simplified the concept, placing it within a Western stereotype of Indian society.The transformation of Caste into a predominately religious system by the colonial state affectedeveryday life, alongside the projection of inferiority involved within the British concept. Thus, under Colonial rule Caste became an increasingly pervasive concept whilst progressively containingreligious elements within its definition. However, Caste was also viewed as a single category amongnumerous others, failing to encompass the general sphere of Indian society as it had previously.Towards the end of Colonial rule Caste once more took on political connotations, used to maintainorder and justify external rule.

Therefore, Caste originated as a hierarchy, encompassing a range of categories to provide thefoundation of Indian hierarchy. However, Caste was then taken and molded to conform to theWestern perception of Indian society, eventually becoming a reminder of segregation and exclusionand used to explain and control the diverse Indian community.

The increased importance attributed to caste difference in the late 19 th and early 20 th centuriesmust be understood within the wider context of changes to Indias political environment. Asignificant body of increasingly outdated scholarship argues that the caste identity was anentirely colonial construct, and the rise of caste consciousness was the direct result of manipulative government policies, aimed at stemming the growing tide of Indian nationalism.I agree with historians such as Bayly, in arguing that, although colonial attempts to acquireknowledge of the Indian population through census data, and the consequent interpretation of such data through sociological and ethnographic lenses had a significant impact upon the

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

16/28

solidification of caste identity, caste is a concept that historically predates the colonial period.

By focusing on the perspectives of figures such as Risley, Dirks acknowledges, that to

contemporaries of the time, caste was inextricably associated with colonial assumptions aboutIndian civilization. Differences between castes were firmly inscribed by the 1871 censuswhich privileged the essentially Brahmanic notion of caste, which placed Brahmans at thehead of a hierarchical system. This census contributed significantly to the politicization of caste by mobilising and unifying groups behind attempts petitions and attempts to influencethe manner in which their group or community was portrayed. Increased preoccupationwith class differences subsequently became a concern of nationalists who were wary thatsuccessful caste mobilisation would result in the British balancing any political concessionswith safeguards for the depressed communities. Ghurye, a prominent Indian sociologistcondemned the anti-Brahman movements demands for reserved representation for low castegroups, arguing that such policies were seriously damaging to the nationalist cause andBritish responsiveness to these reflected a colonial pattern of nurturing class division.Although Ghuryes argument was undeniably influenced by his own Brahman identity, hisargument is given credence by the non-Brahman movements extensive collaboration withthe British.

Bayly and Katsur, although similarly acknowledging that the subcontinent did become more pervasively caste-conscious in the late-colonial period, hold that this increased importance of caste difference was part of a longer history of intergroup conflict. Bayly refers to instancesin which the projection of British stereotypes did have significant ramifications upon Indianidentity and societal organisation, notably the classification of certain caste groups assuitable for army recruitment and the classification of women by caste in the census, whichled to the trend of upward marriage through which men could attempt to acquire a higher-caste status. Bayly is most convincing however, in her claims that campaigns based on caste-reform were not solely a product of modernisation but that the movements of alleged greatcaste uplift actually had roots in honours and status conflicts which had become widespreadsince the early nineteenth century. Rhetoric of social reforming activism was, according toBayly, just a public face for movements which had no intention of abolishing the caste-system but sought new honours within the established hierarchy. Katsuri likewise purportsthat colonial influence was central construction of Rajput identity in the North-Western

provinces, but that this identity had been formed as a multilayered and complex response toBritish influence.

Like the scholarly debate surrounding the rise of communalism during this period, too manyhistorians have claimed that the increased politicisation of caste was a direct andstraightforward consequence of colonial manipulation. I argue that, although castedifferences, as they came to be understood by early twentieth century, were far from

primordial and intrinsic aspects of Indian society, the system of caste had a complex history,and had long been used by Indians to pursue social and political agendas.

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

17/28

A NATION IN MAKING? RATIONAL REFORM , RELIGIOUS REVIVAL AND SWADESHINATIONALISM , 1858 TO 1914

Historians who focused on the politics of Western-educated elites had little hesitation inidentifying the beginnings of modern nationalism, narrowly defined, as the most importanthistorical theme of late nineteenth-century India. The foundation of the Indian NationalCongress in 1885 provided a convenient starting point for those with a penchant for

chronological precision. The recent reorientation of modern Indian historiography towardsthe subordinate social groups has dramatically altered perspectives and added confusion,complexity, subtlety and sophistication to the understanding of Indian society in the highnoon of colonialism. Anti-colonialism can be seen now to have been a much more variegated

phenomenon than simply the articulate dissent of educated urban groups imbued withWestern concepts of liberalism and nationalism. The currents and cross-currents of socialreform informed by reason and its apparent rejection in movements of religious revival are

being weighed and analysed more carefully. The overlapping nature of the periodization of resistance is being recognized. The ulgul an (great tumult) of 18991900 of the Munda tribeon the BengalBihar border was, after all, roughly coterminous with the first major attempt

by the educated urban elite to mobilize mass support for the swadeshi movement of 19058.What was novel, however, about the late nineteenth century was the inter-connectedness,

though not necessarily convergence, of social and political developments across regions onan unprecedented scale. In that general sense it was during this period that the idioms, andeven the irascible idiosyncrasies, of communitarian identities and national ideologies weresought to be given a semblance of coherence and structure. What needs emphasizing is thatthere were multiple and competing narratives informed by religious and linguistic culturalidentities seeking to contribute to the emerging discourse on the Indian nation. If Indiannationalist thought can at all be construed as a derivative discourse, it was derived from manydifferent sources not just the rationalism of

post-enlightenment Europe, but also the rational patriotisms laced with regional affinities andreligious sensibilities that were a major feature of late pre-colonial India.

Some of the impetus to the redefinition of social identities and the quest for social mobilitywas provided by the initiatives of the colonial state. The decennial censuses began a processof enumeration and rank-ordering of castes which spurred a great competition among manysub-castes by jati for high varna status. Upwardly mobile social groups rewrote their castehistories and changed their caste names as they climbed the ladder of respectability. For example, in north Tamil Nadu the Pallis claimed high varna status in 1872 and started callingthemselves Vanniyas; in south Tamil Nadu the Shanans did the same in 1901 and referred tothemselves as Nadars. Between 1872 and 1911, the Kaibartas of west Bengal becameMahishyas, the Chandals of east Bengal Namasudras, and the Koches of north Bengal

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

18/28

Rajbansi Kshatriyas. The desire for higher social status through census manipulation wasdiscernible among Muslims as well: butchers started calling themselves Quraishi and weaversMumin. Many Muslims claimed foreign descent in order to gain recognition as members of the ashraf classes in northern India and Bengal.

Although in 1858 the colonial power had announced its intention not to interfere in the

private realm of religion and custom, its policies in the late nineteenth century ensuredthat precisely these concerns had to be bandied about in the public arenas of the press and

politics. A plethora of communitarian narratives written in modernized vernacular languages, therefore, filled the pages churned out by a burgeoning press and publicationsmarket. In order to gain the attention of a colonial state minded to disburse differential

patronage, publicists needed to dip their pens in the ink of community. A direct publicstatement of anti-colonial politics ran the risk of running foul of the laws of seditionenshrined in a battery of vernacular press acts. The fictive separation of religion and politicsin the colonial stance was breached the moment the British took the momentous decision todeploy religious enumeration to define majority and minority communities. Colonialconstitutional initiatives lent religiously based communitarian affiliations a greater supra-local significance than regional, linguistic, class and sectarian divergences might otherwisehave warranted. The most important step in this regard was the construction of the politicalcategory of Indian Muslim. Whatever the internal differences among Indias Muslims, thisencouraged them to lay emphasis on their religious identity in putting forward politicalclaims. Not all of the social stirrings, of course, are reducible to colonial stimulus, even if they occurred within a broad colonial context of British rule. Brahman social dominance,

bolstered by a British-sponsored neo-Brahmanical ruling ideology, provoked a strong anti-Brahman or non-Brahman backlash in parts of western and southern India. A prominentexample of such a lower-caste movement is Jyotirao Phules

Satyashodhak Samaj (Society for the Quest of Truth), established in 1873 in Maharashtra.The debates between rival schools of Islam in the Punjab and Bengal also had a measure of autonomy from colonial manipulations. The redefinition of a more religiously informedcultural identity among Muslims in the late nineteenth century should not be mistaken,however, for a kind of communalism that has been read back into this period inretrospectively constructed nationalist pasts.

Social reform and religious revival were once seen by historians of the nineteenth century asstark contradictory processes. Hindu revival in the late nineteenth century was reckoned to begaining the upper hand over reformist activities set in motion in the 1820s and 1830s.Educated Muslim society was deemed to be experiencing a tussle between pro-Westreformers and conservative revivalists. Social trends among Hindus and Muslims alike weremuch too nuanced to be captured by the reformrevival, modernity tradition or indeed our (Indian) modernitytheir (Western) modernity dichotomies. It is true that Brahmo reform was

limited to a small circle and Iswarchandra Vidyasagars support for widow remarriage in the1850s was the final episode in which reformers prevailed in the public debate in Bengal. Theatmosphere was markedly more conservative during the controversy over the Age of ConsentAct of 1891, which raised the legal age of consent for girls from ten to twelve. Theintrusiveness of the colonial state in seeking to impose Western medicine during the plagueepidemics of the late 1890s elicited an even more virulent protest all over India. This did notamount to a wholesale rejection of the potential benefits of Western science, but representedan attitude of resistance to an authoritarian colonial state. The conflation of the colonial statewith Western/modern medicine has led some historians to view modern science primarily in

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

19/28

terms of a grave assault on the body of the colonized and to greatly exaggerate the anti-modern, religious overtones of resistance against epidemic measures. A more powerfulcritique of the colonial state would concentrate on its inaction, if not complete dereliction of responsibility, in the arena of public health, and a more historically fine-tuned analysis of theattitudes of colonial subjects would reveal strands of resistance to, as well as selectiveappropriation of, new scientific knowledge.

Religious sensibility could in the late nineteenth century be perfectly compatible with arational frame of mind, just as rational reform almost invariably sought divine sanction of some kind. Speaking at the eleventh social conference in Amraoti in 1897, Ranade scored adebating point against his revivalist critics:

When my revivalist friend presses his argument upon me, he has to seek recourse in somesubterfuge which really furnishes no reply to the question what shall we revive? Shall werevive the old habits of our people when the most sacred of our caste indulged in all the

abominations as we now understand them of animal food and drink which exhausted everysection of our countrys Zoology and Botany? The men and the Gods of those old days ateand drank forbidden things to excess in a way no revivalist will now venture to recommend.

What lay at the root of our helplessness, Ranade declared, was

the sense that we are always intended to remain children, to be subject to outside control, andnever to rise to the dignity of self-control by making our conscience and our reason thesupreme, if not the sole, guide to our conduct. We are children, no doubt, but the childrenof God, and not of man, and the voice of God is the only voice [to] which we are bound tolisten. With too many of us, a thing is true or false, righteous or sinful, simply becausesomebody in the past has said that it is so. Now the new idea which should take up the

place of this helplessness and dependence is not the idea of a rebellious overthrow of allauthority, but that of freedom responsible to the voice of God in us.

Seven years later in a 1904 article entitled Reform or Revival, Lala Lajpat Rai sought toargue that, while the reformers wanted reform on rational lines, the revivalists wantedreform on national lines. Attempting to turn Ranades argument on its head, Lajpat Raiwrote:

Cannot a revivalist, arguing in the same strain, ask the reformers into what they wish toreform us? Whether they want us to be reformed on the pattern of the English or the French?Whether they want us to accept the divorce laws of Christian society or the temporarymarriages that are now so much in favour in France or America? Whether they want to makemen of our women by putting them into those avocations for which nature never meant

them? Whether they want to reform us into Sunday drinkers of brandy and promiscuouseaters of beef? In short, whether they want to revolutionize our society by an outlandishimitation of European customs and manners and an undiminished adoption of European vice?

By this time Ranade was dead and he could not reply that there need be no necessarycontradiction between the rational and the national.

In late nineteenth-century Maharashtra, Hindu revival centred on Poona and it had a clear and strong Brahmanical content. Yet it was also from its Maharashtra base that Ranades

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

20/28

Social Conference sought to make a case for reform rather than revival. Lajpat Rai was alegator of the Arya

Samaj (Aryan Society) led by Dayanand Saraswati which had, in late nineteenth-centuryPunjab and western U.P., sought to include reformist postures on issues such as childmarriage, widow remarriage, idolatry, travel overseas and caste within a framework of the

assertion of Hindu supremacy over other religious faiths. If Hindu regeneration inMaharashtra had a Brahmanical flavour and the variant in Punjab had supremacist overtones,Hindu revival in Bengal certainly had its ambiguities. Ramakrishna Paramhansa, a priest ina Kali temple north of Calcutta, who cast an almost hypnotic spell over the Calcuttaintelligentsia (including staunch rationalists), clearly posed an antithesis to the Westernconcept of rationality. But his disciple Swami Vivekananda, who gained international fame,

preached the twin messages of self-strengthening and social service. He told young men thatit was more important to play football than to pray and predicted a millennium in which the

poor, the downtrodden and the Shudra would come into their own. Vivekananda seemed tohave little difficulty in combining reason with his vision of nation and religion. He deridedthe conservative opponents of the Age of Consent Bill and commented on northern Indian

protectors of the sacred mother cow like mother, like son. Vivekananda was alsogenerally respectful towards other religious faiths, including Islam, and took a clear standagainst what he called religiously inspired fanaticism. So there was in the late nineteenthcentury a great deal of interplay and overlap between the strands of reform and revival,whose meanings varied by region.

A sharply defined fault-line between tradition and modernity as well as Indian and Europeanmodernity makes it impossible to take full account of the contestations that animated thecreative efforts to fashion a vibrant culture and politics of anti-colonial modernity. Theseefforts were not just staked on claims of cultural exclusivity or difference but also onimaginative cultural borrowings and intellectual adaptations that consciously transgressed thefrontier between us and them. A difference-seeking distortion has crept into studies, suchas those of Partha Chatterjee, which privilege a particular strand of our modernity as the tradition of social and historical thinking on modernism and nationalism. BankimChattopadhyay, the Bengali Hindu novelist of the late nineteenth century, has been seen as anexemplar on this view of modernist, nationalist thought at its moment of departure. Yeteven within the charmed circle of the Bengali Hindu middle-class intelligentsia there weremany different responses to the challenge of Western modernity. Rationalism and humanismwere drawn upon by men like Rabindranath Tagore from both Indias pre-colonial andEuropes post-enlightenment intellectual traditions in projects of internal, social regenerationand reform which, on the whole, strengthened the ability to contest Western colonial power inthe arenas of politics and the state. In its attitude to European modernity the first radicalintellectual challenge to moderate nationalism was remarkably discriminating, judicious and

balanced. Aurobindo Ghoses remarks on this point in his sixth essay New Lamps for Old, published 4 December, 1893, bears quoting at some length:

No one will deny, no one at least in that considerable class to whose address my presentremarks are directed, that for us, and even for those of us who have a strong affection for original oriental things and believe that there is in them a great deal that is beautiful, a greatdeal that is serviceable, a great deal that is worth keeping, the most important objective is andmust inevitably be the admission into India of Occidental ideas, methods and culture: even if we are ambitious to conserve what is sound and beneficial in our indigenous civilization, we

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

21/28

can only do so by assisting very largely the influx of Occidentalism. But at the same time wehave a perfect right to insist, and every sagacious man will take pains to insist, that the

process of introduction shall not be as hitherto rash and ignorant, that it shall be judicious,discriminating. We are to have what the West can give us, because what the West can give usis just the thing and the only thing that will rescue us from our present appalling condition of intellectual and moral decay, but we are not to take it haphazard and in a lump; rather we

shall find it expedient to select the very best that is thought and known in Europe, and toimport even that with the changes and reservations which our diverse conditions may befound to dictate. Otherwise instead of a simple ameliorating influence, we shall have chaosannexed to chaos, the vices and calamities of the West superimposed on the vices andcalamities of the East.

To put it in another way, colonized intellectuals were clearly seeking alternative routes of escape from the oppressive present, not all of which lay through creating illusions about o ur

past and denouncing the ir modernity.

An extension of the scope of enquiry to Muslim ashraf classes of northern India immediatelyreveals more intellectual variations on the theme of colonial and anti-colonial modernity. Thevariety of the Muslim elites responses to British colonialism and Western modernity cannot

be captured within the facile distinctions between liberals and traditionalists or modernists or anti-modernists. A reform-oriented current within Indian Islam was led bySaiyid Ahmed Khan, who sought to alter British conceptions about inherent Muslimdisloyalty and urged his co-religionists to accept Western education but not necessarily all itsideals. It was religious narrow-mindedness which, according to him, had prevented Muslimsfrom taking advantage of the new education. In 1875 he established the Aligarh Anglo-Muhammadan Oriental College which attracted the sons of Muslim landlords of northernIndia and drew British patronage. Yet, while making some compromises with the British, theAligarh movement, initiated by

Saiyid Ahmed, still jealously guarded against intrusions into what was termed custom as wellas personal law. Many affluent Muslims in north India and Bengal challenged the Britishattempt to draw a distinction between legal public waqfs (charitable institutions) and illegal

private ones established for the benefit of family members. Since charity begins at home, theysaw no reason why they should be debarred from preventing the fragmentation of propertythrough recourse to the time-honoured loophole in Islamic inheritance laws. After all, in thePunjab it was customary law rather than the Islamic sharia which decided matters related toinheritance. Saiyid Ahmeds rational approach to Islamic theology and law neverthelessearned him the hostility of the ulema bunched in the theological seminaries at Deoband and,less vociferously, Faranghi Mahal in Lucknow.

The ulema were not alone in opposing Saiyid Ahmeds new-fangled views. His ardent

promotion of Western knowledge and culture as well as loyalty to the raj drew acerbiccomments from Muslims attached to their societal moorings and the ideal of a universalMuslim ummah . The anti-Aligarh school was given a fillip by the great preacher of Islamicuniversalism Jamaluddin al-Afghani, who lived in Hyderabad and Calcutta between 1879 and1882. In India al-Afghani tempered his adherence to the political principles of Islamicuniversalism with calls for HinduMuslim unity against British colonialism. The poet Akbar Allahabadi, in his satirical verses, mercilessly ridiculed Saiyid Ahmad Khan and hisassociates for their shallow imitation of Western culture:

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

22/28

The venerable leaders of the nation had determined Not to keep scholars and worshipers at adisadvantage Religion will progress day by day Aligarh College is Londons mosque

But Akbar Allahabadi was equally derisive towards obscurantist maulvis. Maulana Shibli Numani, an associate of Saiyid Ahmed Khan, endorsed the Aligarh line that Indian Muslimswere British subjects and not bound by religion or Islamic history to submit to the dictates of

the Ottoman Khilafat. Yet on matters closer to home, Shiblis Islamic sentiments led him totake political paths different from those charted by Saiyid Ahmed Khan. By 1895 he was

publicly opposing Saiyid Ahmed Khans policy of Muslim non-participation in the Indian National Congress. So, in the 1890s, although there were serious instances of HinduMuslimconflict for instance, over the cow protection issue, the question of Hindi versus Urdu, andthe nature of electoral representation in much of northern India and beyond intra-communitarian debates, tensions and contradictions were almost quite as important as inter-communitarian ones.

Deepening and widening the historical perspective to include subalternity along lines of gender and class makes the cognitive map of colonial and

anti-colonial modernity even richer and more complex. Rokeya Sakhawat Hossains earlytwentieth-century tract, S ul t anas Dr e am, in which all the men were put in purdah, is perhapsan extreme but revealing example of male dominance without hegemony. In any case, anoveremphasis on the discourses of elite men and the modern political associations formed

by them would provide a very incomplete picture of the multifaceted contestations of thehubris of colonial modernity. Anti-colonial resistance in the late nineteenth century certainlytook many forms. Civilian insurrections of the sort noted in the early nineteenth century wereless frequent but not uncommon. A multiclass rural revolt took place in Maharashtra in 1879.Tenants protests against landlords took on a religious flavour among the Mappillas of Malabar. The new context of colonial tenancy law appeared to rob peasant resistance inBengal of its communitarian character and injected a legalistic and quasi-class dimension, asin the anti-rent Pabna agrarian movements of the 1870s. The collapse of the cotton boomcreated the conditions for the Deccan riots of the mid-1870s, in which Marwari moneylendersfrom the north were prime targets. No-revenue campaigns were launched in Assam andMaharashtra in the 1890s. Where forests met the plains in Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, central India,Bengal and Bihar, tribes revolted against the incursions of foreigners, white and brown. Themost serious millenarian tribal uprising occurred in eastern India, led by Birsa Munda in18991900. Subaltern anti-colonialism predated the attempts

by an urban elite to engage in the politics of mass mobilization against British rule.

In the cities at this time, the intelligentsia were articulating their disaffection in organizedfashion and the small class of industrial labour made their early protests in a combination of

class and communitarian modes brought from the rural areas. Educated Indians had beenforming political associations at the regional level since the 1870s. The more prominentamong these were the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha (1870), the Indian Association (in Bengal,1876), the Madras Mahajana Sabha (1884) and the Bombay Presidency Association (1885).After coming together at a couple of national conferences, these city-based professionalswere able to set up a permanent organization the Indian National Congress in 1885. Thefirst annual session of the Congress was attended by seventy-three self-appointed delegates.The political character and role of the early spokesmen of Indian nationalism variedaccording to region. In Bengal the professionals who formed the Indian Association had

-

8/8/2019 The Traditional Social Stratification in Maharashtra Was Governed by Varnashrama Dharma

23/28

broken ranks with rentier landlords who had their own British Indian Association since 1851.The fact of European dominance of commerce and industry in eastern India also facilitated acertain autonomy and radical disposition of the Bengali intelligentsia. Elsewhere, the vaki l s (lawyers) who played such a dominant role in early nationalist organizations were no morethan publicists tied to the interests of the shet ias (commercial men) in Bombay or the rais e s (local notables) in Allahabad.