The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

-

Upload

andres-rojas-ortega -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

1/18

This article was downloaded by: [Universidad de Chile]On: 02 May 2013, At: 13:19Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Constructivist PsychologyPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/upcy20

The Problem of Narrative CoherenceDan P. Mcadams

a

aNorthwestern University, Program in Human Development and Social Policy, Evanston,

Illinois, USA

Published online: 16 Aug 2006.

To cite this article: Dan P. Mcadams (2006): The Problem of Narrative Coherence, Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 19:

109-125

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720530500508720

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematicreproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form toanyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contentswill be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses shouldbe independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims,proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly inconnection with or arising out of the use of this material.

http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditionshttp://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditionshttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720530500508720http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/upcy20 -

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

2/18

109

Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 19:109125, 2006Copyright Taylor & Francis Goup, LLCISSN: 1072-0537 print / 1521-0650 online

DOI: 10.1080/10720530500508720

THE PROBLEM OF NARRATIVE COHERENCE

DAN P. MCADAMS

Northwestern University, Program in Human Developmentand Social Policy, Evanston, Illinois, USA

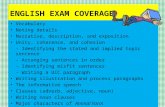

A growing number of psychological theorists, researchers, and therapists agreethat people create meaningful selves through the individual and social con-struction of coherent life stories. But what is a coherent story? And are goodlife stories always coherent? This article addresses the problem of narrativecoherence by considering the propositions that coherent life stories (1) provideconvincing causal explanations for the self, (2) reflect the richness of livedexperience, and (3) advance socially-valued living action. Like all stories, lifestories exist to be told or performed in social contexts. Most criteria for coher-ence, therefore, reflect the culture within which the story is told and the life islived.

The idea that a human life resembles, or can be made to re-semble, a coherent story holds a great deal of intuitive appeal.After all, it is quite likely that people have been telling stories

about lives for thousands of years. But it has only been within thepast two decades that psychological researchers, theorists, andpractitioners in the United States and Europe have begun toexplore stories and storytelling in a systematic and critical way. Anarrative psychology of human lives began to emerge in the 1980sas social philosophers (MacIntyre, 1981; Ricoeur, 1984) and so-cial scientists (Bruner, 1986; Cohler, 1982; McAdams, 1985; Sarbin,1986; Polkinghorne, 1988) proposed that people make sense oftheir own lives in terms of self-defining life storiesintegrative

Received 4 September 2005; accepted 25 November 2005.

The preparation of this article was supported by a grant to the author from the

Foley Family Foundation to establish the Foley Center for the Study of Lives at North-western University.

Address correspondence to Dan P. McAdams, Program in Human Development andSocial Policy, Northwestern University, 2120 Campus Drive, Evanston, IL 60208, USA.E-mail: [email protected]

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

3/18

110 D. P. McAdams

narratives of self that reconstruct the past and anticipate the fu-

ture in such a way as to provide life with identity, meaning, andcoherence. Around the same time, cognitive scientists began toconsider human information processing in terms of story scriptsand autobiographical scenes (Mandler, 1984), and developmentalpsychologists began to study the emergence of narrative under-standing in children (Nelson, 1988). On the practitioner side ofthe ledger, the 1980s witnessed a turn toward narrative amongmany psychoanalysts, who now began to conceive of therapy as aprocess of life-story re-formation and revision (Schafer, 1981; Spence,1982). Shortly thereafter, new approaches to counseling and psy-chotherapy began to emerge under the banner ofnarrative therapy

(White & Epston, 1990), a movement that continues apace today(Angus & McLeod, 2004; Lieblich, McAdams, & Josselson, 2004).The many different approaches to the narrative study of lives

that have emerged in the social sciences and the helping profes-sions over the past 20 years tend to share implicit constructivistassumptions about human behavior and experience (Josselson &Lieblich, 1993; Neimeyer, 2001; Neimeyer & Raskin, 2000). Peopleconstruct stories to make sense of their lives; therapists and theirclients co-construct new narratives to replace disorganized or in-coherent stories of self; lives become meaningful and coherent(or not) amidst the welter of social constructions and discoursesthat comprise contemporary postmodern life. It follows, further-

more, that story constructionat the level of the individual, group,and even culturemoves (ideally) in the direction of coherence(Linde, 1993). Theorists, researchers, and therapists of many dif-ferent stripes underscore the importance of constructing coher-ent narratives of the self. But what is a coherent narrative? Whatmakes a life story coherent, or incoherent? And why is coher-ence such an important property of stories? Many strong voicesin the narrative study of livesfrom sociologists to developmentalpsychologists to clinicianssuggest that a coherent story is, almostby definition, a good story. But are coherent life stories alwaysgood? And to what extent must a good life story be coherent?

Basic Storytelling

The most fundamental property of stories is that they exist to betold. Stories presuppose a basic scenario of human sociality: a

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

4/18

Narrative Coherence 111

teller narrates or performs a story in a social context, to or for

an audience. The teller may seek to entertain, instruct, admon-ish, or inspire the audience, or the teller may merely be trying tostave off boredom, just passing the time of day. Whatever themotive or function behind the storytelling effort, the entire sce-nario falls apart if the audience cannot make sense of what theperformer conveys. In a social context, stories must be coherentenough to communicate something, no matter how simple themessage (Labov, 1972). The storyteller cannot avoid, then, thisimplicit question: Am I being understood? If the answer is no,then there is no point in telling the story in the first place.

In the most basic sense, the problem of narrative coherence

is the problem of being understood in a social context. A storytold in a foreign language is incomprehensible to a native audi-ence. In a similar manner, a story that depicts events or happen-ings in a random way, or in a way that defies the audiencesexpectations regarding how human affairs should unfold in time,may be deemed incoherent. Ricoeur (1984) and Bruner (1986)write that stories convey the vicissitudes of human intention or-ganized in time. A character wants something or intends to ac-complish something and the story chronicles that effort over time.Mandler (1984) argues that many stories follow a predictablegrammar: An initiating event evokes a response in the protago-nist, who then acts to accomplish a goal, which leads to a conse-

quence or reaction on the part of another character, which leadsto another attempt, and so on. Prior events are seen as causing,or at least leading up to, subsequent events. As one event leadsto the next, a story may build to a climax; by the end, tension isresolved and the listener experiences a sense of closure (Kermode,1967). Stories are typically structured to capture and hold anaudiences attention and to elicit from the audience certain emotionalresponses (Brewer & Lichtenstein, 1982). The plot structure needsto articulate a deviation from the course of humdrum, everydaylife in order to create suspense and elicit the audiences curiosity(Bruner, 1990). Otherwise, why tell a story?

Stories that defy structural expectations about time, inten-

tion, goal, causality, or closure may fail to elicit curiosity andinterest and may strike audiences as incoherent, or at least in-complete. A story that begins at the chronological end, jumpsthen to the chronological beginning, moves forward two years

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

5/18

112 D. P. McAdams

from that point, and then moves backward one month, and then

forward 10 years may be difficult to follow. The listener expects astory to have a beginning, middle, and end, and this expectationis typically couched in terms of time or chronology. Of course, askilled narrator may be able to toy with these expectations togood effect, but (James Joyce notwithstanding) he or she will stillneed to provide enough information so that the listener/reader/audience can eventually piece together a rough chronology ofevents. If the narrator does not do this, listeners may do it forthemselves, imposing a coherent temporal structure onto an ac-count that seems to lack one (Mandler, 1984). Or listeners mayjust give up, concluding that the story simply does not make

sense. In a similar vein, stories that depict characters whose ac-tions seem to have no motive or goal, or lay out plot lines thatseem to go nowhere, or fail to provide a causal account for asequence of events, or never reach a culmination, resolution, orsatisfying sense of an ending may also seem incoherent. In re-sponse to these kinds of stories, audiences end up scratchingtheir heads and wondering: What was that story about? Why didthat happen? What was the point? And concluding, I just dontget it.

While coherence, then, may refer to the structure or formof a story, it may also pertain to a storys content. A story thatdepicts events or happenings that defy the listeners understand-

ing of how the world works and how human beings typically act,think, feel, and want may seem as incoherent as one that violatesstructural norms. If, for example, I tell you a story about a younggirl who was so hungry that she no longer wanted to eat, or if Itell you how my friend once loved a woman so much that he felthe had to kill her, you are likely to say that my tales do not quitemake sense, or you will ask for more information, more narra-tive details, more context to render them more coherent thanthey initially seem to be. Our shared expectation is that as peopleget hungrier, they typically seek to eat; we also expect that as apersons love for another increases, he or she typically does notseek to kill the object of that love. Of course these kinds of

accounts could be made coherent (the girl lives in a universewherein eating depletes the bodys resources; my friend sufferedan abusive childhood, so now he associates love with violence),but in their present form they defy what most audiences under-

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

6/18

Narrative Coherence 113

stand to be human nature, how people typically relate to each

other, the facts of the natural world, and so on.In the examples of the hungry girl and the love-stricken-

friend, the storys content renders it incoherent. What happensin the story does not make sense. In all cultures, storytellers areconstrained by content expectations that people the world overlikely have regarding human nature and social relationships. It isquite likely, for example, that the story of the hungry girl wouldmake as little sense among hunters and gatherers in the Austra-lian outback as it initially does among well-educated Europeans.But many other expectations about what kinds of plots can betold and what kinds of characters can be depicted are socially

constructed and articulated according to local norms. Shwederand Much (1987) document how storied explanations for behaviorthat would make little sense to most Americans and Europeansnarratives that explain todays behavior, for example, in terms ofthe kinds of food eaten yesterdayare viewed to be highly co-herent and meaningful in a rural Indian village. Within a givensociety, moreover, different narrative traditions offer their ownstandards of coherence. Among many evangelical Christians inthe United States, for example, stories about Christs secondcoming to earth, about Christians being taken up to heavenwhile all others are left behind, and about a great war betweenthe forces of God and the forces of Satan in the last days hold

tremendous power and coherence. Millions of Americans deeplybelieve these stories to be true. For millions of other Americans,these stories make no sense whatsoever. They seem unbelievable,incoherent, and even delusional.

Causal Explanations

Bruner (1986) suggests that the rational and material-cause logicof what he calls theparadigmaticmode of human thinking is bestsuited for explaining how the physical world works, but whenpeople seek to explain human behavior and experience they re-sort to the narrativemode. If the paradigmatic mode searches for

the one true answer to a question about physical reality, Brunersnarrative mode entertains a range of plots, characters, and sto-ries in order to explain why people do what they do. Narratorscast themselves as protagonists in the stories they tell to explain

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

7/18

114 D. P. McAdams

their lives and to make meaning of their own thoughts, feelings,

desires, and behaviors extended over time. If a life story is tomake psychological sense, then, it must explain how a personcame to be (and who a person may be in the future). It mustprovide a causal account of how, for example, a young womandecided to become a physician or why a middle-age man regretsnot having married his high-school sweetheart. The stories narra-tors provide to explain their lives (for themselves and others)cannot be proven true or false in the same way that paradigmaticarguments can often be assessed. But the stories still need tosound convincing.

In their research on adult attachment orientations, Main

(1991) and her colleagues ask men and women to recall impor-tant incidents from their childhood involving relationships withtheir parents and to consider how those incidents may have im-pacted their current functioning. In a number of studies, adultswhose accounts indicate a secure/autonomous attachment orienta-tion focused easily on the questions; showed few departures fromusual forms of narrative or discourse; easily marked the prin-ciples or rationales behind their responses; and struck judges asboth collaborative and truthful (Main, 1991, p. 142). The narra-tors with secure attachment histories provided more coherentaccounts of their childhood, including stories of both positiveand negative events with caregivers. By contrast, adults whose

accounts were judged to be less securethose showing dismissingand preoccupiedattachment orientationstended to be relativelyincoherent in their narrative transcripts. They exhibited

logical and factual contradictions; inability to stay with the interviewtopic; contradictions between general descriptors of their relationshipswith their parents and actual autobiographical episodes offered; appar-ent inability to express early memories; anomalous changing in wordingor intrusions into topics; slips of the tongue; metaphor or rhetoric in-appropriate to the discourse context; and inability to focus upon theinterviews. (p. 143)

Insecure orientations were also indicated by narrative passages

relying on bizarre thought patterns and magical causality (p.145). Being able to tell stories about childhood that themselvesprovide plausible causal accounts regarding the impact of parentson the self is a key indicator of a secure attachment orientation

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

8/18

Narrative Coherence 115

in adulthood, argues Main. Such accounts strike the listener as

sensible and believable; they provide coherent causal explana-tions for how a person believes he or she has developed overtime.

A number of theorists argue that people are not typicallyable to construct full life stories that provide convincing causalexplanations for how they came to be who they are until theyhave reached their late-adolescent or young-adult years (McAdams,1985; Singer, 2004). Reviewing research on life-storytelling andnarrative understanding, Habermas and Bluck (2000) demon-strate that the full expression of narrative identity awaits the con-solidation of four different cognitive skills, each linked to a form

of narrative coherence. What Habermas and Bluck (2000) calltemporal coherence typically emerges before the age of five, as chil-dren learn to recall and recite single events in their lives as littlestories with beginnings, middles, and endings. Temporal coher-ence refers to the ability to put the happenings of a single eventinto a sensible order. As they grow older, children learn aboutwhat events typically make up a normal life writ large, and theyinternalize societys expectations and assumptions about the hu-man life course. They may learn, for example, that children livewith their parents through most of their teen-aged years, thatthey may leave home to continue their schooling or get a jobafter that, that they may eventually find a life partner and per-

haps have children, that people often retire in their 60s, thatthey may live as long as age 90 or more, and so on. Differentsocieties and different subcultures hold different expectationsabout the life course, expectations that are also strongly shapedby gender and class (Stewart & Malley, 2004). The internaliza-tion of this societal knowledge provides what Habermas and Bluck(2000) describe as a sense of autobiographical coherencean im-plicit understanding of the typical events and their timing thatgo into the construction of a typical life story. The person maycome to see his or her own life as a variation on a general auto-biographical script.

What Habermas and Bluck (2000) call causal coherenceemerges

in adolescence as people now become able to link separate eventsinto causal chains. The events themselves become the key epi-sodes to explain a current aspect of self or a future goal. Forexample, a young man may now be able to explain why he wants

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

9/18

116 D. P. McAdams

to become a lawyer. It all began, he suggests, in junior-high school

when he realized that he enjoys arguing with his teachers. Litigatorsargue cases; maybe I might be good at that, he thought. In highschool, he talked with his girlfriends mother, who is a practicinglawyer, about what lawyers do and what law school is like. Hisinterest was piqued further through college classes in politicalscience where he learned more about how laws are made andchanged. These developments dovetailed with the growing rec-ognition (in high school) that his baseball skills were probablynot strong enough to get him to the major leagues, putting anend to a rival career aspiration. The aspiring lawyer is able to putthese events together into causal chains, creating an explanatory

narrative. Should he eventually change his mind and decide togo into the ministry, he will need to choose different events, orspin the same ones in a different way, in order to provide acoherent explanation for a new life goal.

In a related fashion, adolescents and young adults are alsoable to extract from a series of narrated events an overarchingtheme or general message, revealing what Habermas and Bluck(2000) call thematic coherence. A young woman may describe dif-ferent events from childhood and her teenaged years that allconverge on the conclusion that I am a brutally honest person.A young man may survey very different episodes from school,family life, and experiences with friends to demonstrate that I

tend to have problems with commitment, especially when I reallycare about the people involved. In both these examples, thenarrator tries to explain a general self-attribution in terms of arecurrent theme that can be traced through different scenes inthe life story. The story is coherent to the extent that the listeneris convinced that the different scenes indeed express the sametheme.

In both causal and thematic coherence, the narrator justi-fies a conclusion about the self (I want to be a lawyer; I am abrutally honest person) in terms of an explanatory narrative. Work-ing in Bruners narrative mode of thought, the person links to-gether different scenes in his or her life to explain who he or she

is (Baerger & McAdams, 1999). Whether the scenes really hap-pened the way the narrator recalls and tells them is not a trivialissue (coherent stories should be credible, too), but the coher-ence of the account relies largely on the narrators powers of

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

10/18

Narrative Coherence 117

reconstruction, imagination, and synthesis. People differ substan-

tially with respect to their abilities to tell life stories exhibitingcausal and thematic coherence. Pals (in press) has examinedindividual differences in the extent to which adults justify self-attributions and draw conclusions about the self from autobio-graphical memories. She shows that the tendency to display causaland thematic coherence in life stories is positively associated withindependent measures of psychological well-being. In a similarvein, Blagov and Singer (2004) identify integrative memories in lifestories, in which narrators draw lessons about the self, importantrelationships, or life in general, suggesting that these kinds ofnarrative accounts are especially coherent and convincing. Thorne,

McLean, and Lawrence (2004) distinguish between specific les-sons learned and general insights gained in life-narrative accounts.Stories about lessons spell out how a protagonist applies what heor she learns from past events to similar new events whereasinsight stories reflect on the larger implications of the event forones construal of self or relationships with others. According tothese researchers, listeners are more positively inclined towardinsight stories, over stories about specific lessons. Among the mostcoherent and convincing life-narrative accounts are those thatshow how a protagonist gains insight, wisdom, or self-understandingfrom a series of reconstructed life scenes.

Lived Experience

In a clinical setting, a therapist may work with a patient to trans-form a disorganized and scattered life story into one that expressesmore causal and thematic coherence (Dimaggio & Semerari,2004). All other things being equal, a life story that explains clearlyhow a person came to be who he or she isa narrative thatsuccessfully integrates a life in timeis better than one that doesnot. Such a story suggests a modicum of self-insight and is morelikely, than an incoherent story, to make sense to the importantaudiences in a narrators lifefrom family, friends, and coworkersto the broader social settings and institutions that comprise the

social ecology within which a persons life is embedded. But iscoherence, in the sense described to this point, always enough?

Josselson (2004) describes a clinical case in which a patientarticulated a very clear and convincing life story whose rejection,

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

11/18

118 D. P. McAdams

nonetheless, became the central goal of psychotherapy. A 19-

year-old woman referred to therapy for alcohol abuse, Heidipresented a well-ordered autobiographical account of a bright,high-achieving college student who enjoyed a full life with friendsand family. In therapy, however, it became clear that the storyHeidi told was not of her own emotional making. Instead, it wasthe story that Heidis mother narrated for her. Even in the firstsession, Heidi hinted that she was not the narrator of her ownlife. Asked how she had decided to come to therapy in the firstplace, Heidi replied that she did not know for sure, but, she said,I will be home this weekend and Ill listen to my mother tell itas a story. She weaves it into a plot with logic and a goal (Josselson,

2004, p. 112). Throughout her life, Heidi looked to her motherand other important authority figures to tell her what her lifemeant. In essence, Heidi functioned as the protagonist in a storynarrated by somebody else. What Heidi was missing were notthe cognitive components but the imagination necessary to makeher story go beyond logical, causal coherence to a story rootedin subjectivity, Josselson wrote (2004, p. 114). Over the courseof therapy, furthermore, Josselson came to realize that Heidi wasnow looking to her, the therapist, to narrate a new story for her.Josselson found it sometimes difficult to resist, for a therapistsempathy and desire to help can often result in a rush to coher-ence. Nonetheless, Josselson counsels therapists to hold back

when necessary and to be willing to experience with the patientthe anxiety of sitting with undigested elements of experienceuntil they take meaningful shape, however transitory or provi-sional the shape may be (Josselson, 2004, p. 125).

The case of Heidi points to a larger problem in evaluatinglife narratives, whether the evaluation takes place in therapy orresearch. For all its coherence and clarity, Heidis story was nother own. Her story did not reflect her own subjectivity, her ownlived experience (White & Epston, 1990, p. 15). Life is messierand more complex than the stories we tell about it. Yet the storiesneed to convey some of that complexity if they are to be viewed,by the self and by others, as credible and life-affirming. Bruner

(1986) argues that stories ultimately seek verisimilitudethe life-likeness that is conveyed when a story seems to capture well whatsubjective human experience is really like. Researchers such asKing and Raspin (2004) and Pals (in press) show that the ability

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

12/18

Narrative Coherence 119

to dig deep into painful experiences and to narrate personal

suffering in an honest and convincing way is indicative of psy-chological health and maturity in adulthood. Rosenwald (1992)writes: Better stories tend to be structurally more complex, morevaried and contrastive in the events and accompanying feelingsportrayed, more interesting and three-dimensional (p. 284). Lifestories that achieve verisimilitude express the full panoply of dis-cordant strivings, emotions, and points of view. As Hermans (1996)has argued, subjective experience is animated by contrasting voices,trends, and idiosyncratic expressions. The well-formed narrativeidentity is like a polyphonic novel, Hermans claims, giving fullexpression to a complex and shifting dialogue among the many

voices of the self. Stories that succumb to a single, dominantperspective, no matter how coherent they may seem to be, aretoo simplistic to be true; they fail to reflect lived experience.

Perspectives on narrative identity that prioritize multiplicityoffer a range of attitudes about coherence. Hermans (1996) re-jects the simple consistency of a univocal self, but he suggeststhat a kind of self-coherence can nonetheless be realized in themultivocal dialogue itself. Different voices, or I-positions, asserttheir separateness and autonomy, Hermans maintains, but theymay also be seen as working together by virtue of participating inthe same self-defining conversation. For Hermans, the dialogicalself incorporates both centrifugal and centripetal featuresforces

that promote both separateness and coherence. Hermans con-ceives of the dialogical self

as a synthesizing activity, that is, as a continuous attempt to make the selfa whole, despite the existence of parts that try to maintain or evenincrease their relative autonomy. The nature and function of this syn-thesizing activity can best become understood if we discern two antago-nistic forces in the self; one centrifugal, another centripetal. The cen-trifugal force refers to the tendency of the different parts to maintainand increase their autonomy: The lover wants to love, the critic to criti-cize, the artist to express, the achiever to excel. As long as these charac-ters are involved in their activity, they are not concerned with the strivingsand longings of the other characters. Their intentions require a certaindegree of autonomy. The centripetal force, however, attempts to bring

these tendencies together and to create a field in which the differentcharacters form a community. For the establishment and organizationof this community, the synthesizing quality of the Self is indispensable.(Hermans & Kempen, 1993, pp. 9293)

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

13/18

120 D. P. McAdams

Other theorists, however, are less sanguine about the selfs

powers to create coherence. Sampson (1989), Gergen (1991),and Raggatt (in press) argue that the modern self is bombardedwith so many diverse stimuli and shifting demands that it simplycannot assume a coherent form. Raggatt (in press) asserts thatthe imposition of coherence upon modern life constitutes a he-gemonic insult. Life stories should resist dominant cultural nar-ratives and strive instead to portray the rich diversity of livedexperience. For Gergen (1991), modern life creates a saturatedself. For many people living in contemporary, postindustrial soci-eties, lived experience is chaotic, confusing, even multiphrenicGergen (1991) asserts (p. 7). Therefore, if life narratives are true

to lived experience, they are likely to be unstable, indeterminate,and incoherent.Gergen may be exaggerating to make a cultural point, but

clinicians are indeed quite familiar with the kinds of life storieshe depicts. Dimaggio and Semerari (2004) write that many psy-chotherapy patients relate

stories that are confused, disordered, and incomprehensible, character-ized by thought themes and emotions that get mixed together withoutany apparent sense. Patients may provide descriptions of the same char-acter that are intense and at the same time opposite and mutually in-compatible, or they may open an infinite number of parentheses with-out ever closing them while hundreds of characters come onto the stage

competing with each other for the floor. (p. 267)

Many life stories portray the crowding together of a multiplicityof voices, struggling to get heard, drowning each other out, com-peting with each other, and subjecting a listener to an unintelli-gible whir (Dimaggio & Semerari, 2004, p. 268). For these therapists,life stories can be too true to lived experience! When the selfssynthesizing powers break down, therapists need to help patientsconstruct stories with fewer characters and simpler plots, in thehope that more coherent life stories will translate into more co-herent and more effective lived experience.

Advancing Living Action

A life story is more than a mere literary production. It is a storyof the self told by a living person whose actions affect others. It is

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

14/18

Narrative Coherence 121

a story whose form and contents hold real-world significance.

The problem of narrative coherence, therefore, extends to theissue of living action. Satisfactory [life] stories, Rosenwald (1992)writes, advance living action (p. 284). The stories we live bymust be evaluated with respect to their influence on how we live.A paranoid and self-absorbed middle-aged man may present alife story that convincingly and coherently explains how he cameto be who he is and where he is going in the future. His storymay fully express the deep lows and the exalted emotional highshe has experienced. It may effectively give voice to the manydifferent characters who populate his story. It may fully expresshis lived experience. But is this coherent story a good story?

Should the audiencefriends, family, societyrest content withthe narrative identity this man presents?Researchers, theorists, and clinicians continue to struggle

with the question of how life stories do and should relate tosocial life itself. The issues raised in this inquiry transcend theliterary and the psychological to encompass morality, values, andthe meaning of a good life. Some writers argue that a coherentlife story presupposes a clear moral perspective on the part ofthe narrator/protagonist (MacIntyre, 1981). Life stories are nevervalue-free, the argument goes. Narrators make implicit moral claimswhen they construct stories to convey their lived experience andto explain who they are (Linde, 1993). Furthermore, the life

stories they construct are grounded in moral assumptions andideological convictions regarding how the world should work andhow human beings should relate to it and to each other (McAdams,1985). When traumatic events undermine the ontological andmoral assumptions upon which a life story is based, the narratorfaces the daunting challenge of reworking those assumptions inorder to make new meanings in a world that now seems mean-ingless (Neimeyer, 2001; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995). For a lifestory to be considered coherent, therefore, it needs to be implic-itly based on a recognizable set of human values, and it needs tobe told from a recognizable moral perspective. The perspectiveshould advance the living action of a moral agent. That action

will be evaluated within moral communities, that is, all humancommunities. For social life is always moral in some sense, alwaysevaluated with respect to explicit and implicit norms about whatis good and what is not.

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

15/18

122 D. P. McAdams

This all seems a tall order for the concept of narrative co-

herence. It may suggest that we are stretching the notion of co-herence too far. Perhaps a more sensible assertion would go likethis: Good life stories need to be coherent, but coherence is notenough. If stories are to advance living action, if they are toinspire lives wherein protagonists love deeply and work effec-tively, lives in which people make positive contributions to theworld around them, then life stories must express more thanmere narrative coherence. We live and we tell, as Sartre (1965)understood. Human beings are storytelling animals, Sartre main-tained, but the stories we tell do not need to relate easily to thelives we live. Too much telling can get in the way of living; narra-

tive coherence may signify what Sartre called bad faith.On the other hand, some researchers, theorists, and thera-pists have argued that people who do indeed love, work, and livewell, and who do make especially positive contributions to theworld around them, dotell especially coherent stories about theirlives (Colby & Damon, 1992; Rosenwald, 1992; White & Epston,1990). For example, McAdams (2006; McAdams, Diamond, deSt. Aubin, & Mansfield, 1997) shows that midlife American adultswho score especially high on measures ofgenerativityindicatinga highly productive and caring approach to social lifetend toconstruct highly coherent life stories whose main themes con-stellate around the idea of redemption. Redemptive life narra-

tives portray an innocent but deeply principled protagonist whojourneys forth into a dangerous world, transforming sufferinginto advantage, struggling with contrasting desires for freedom/power and community/love, and ultimately seeking to give backto others for the blessings enjoyed along the way. The redemp-tive narratives told by highly generative American adults in theirmidlife years appropriate some of the most cherished (and con-tested) discourses running through American cultural historyProtestant conversion narratives, rags-to-riches stories about theAmerican dream, narratives of liberation and freedom, self-helpnarratives about recovery and the actualization of human poten-tial, broader discourses about manifest destiny and the chosen

people. These kinds of stories are widely recognized in Americansociety as coherent and convincing accounts of the good life,even as they are sometimes critiqued for their presumptuous-ness, their lack of ambivalence, and their exuberant celebrationof the expansive individual self.

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

16/18

Narrative Coherence 123

In considering the power of life stories to advance living

action, the issue of narrative coherence shades into moral concernsand ultimately reveals the cultural underpinnings of narrativesand of the very concept of coherence itself. If the first principle ofstories is that they exist to be told, then any consideration ofnarrative coherence must eventually come to terms with the charac-teristic assumptions regarding what kinds of stories can and shouldbe told in a given culture, what stories are understandable andvalued among people who live in and through a given culture. Andthe same consideration cannot be divorced from cultural expecta-tions regarding what kinds of lives people should live. Livingaction, like narrative identity, can never hide from the interpretive

cultural eye. At the end of the day, culture will judge whether a lifeis worth living, and whether a life story is worth telling.

References

Angus, L. E., & McLeod, J. (Eds.) (2004). The handbook of narrative and psycho-therapy. London: Sage.

Baerger, D. R., & McAdams, D. P. (1999). Life story coherence and its relationto psychological well-being. Narrative Inquiry, 9, 6996.

Blagov, P. S., & Singer, J. A. (2004). Four dimensions of self-defining memories(specificity, meaning, content, and affect) and their relationships to self-restraint, distress, and repressive defensiveness. Journal of Personality, 72,481512.

Brewer, W. F., & Lichtenstein, E. J. (1982). Stories are to entertain: A struc-

tural-affect theory of stories. Journal of Pragmatics, 6, 473486.Bruner, J. S. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.Bruner, J. S. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Cohler, B. J. (1982). Personal narrative and the life course. In P. Baltes and

O. G. Brim, Jr. (Eds.), Life span development and behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 205241). New York: Academic Press.

Colby, A., & Damon, W. (1992). Some do care: Contemporary lives of moral commit-ment. New York: The Free Press.

Dimaggio, G., & Semerari, A. (2004). Disorganized narratives: The psychologi-cal condition and its treatment. In L. E. Angus and J. McLeod (Eds.), Thehandbook of narrative and psychotherapy (pp. 263282). London: Sage.

Gergen, K. (1991). The saturated self. New York: Basic Books.Habermas, T., & Bluck, S. (2000). Getting a life: The emergence of the life

story in adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 748769.Hermans, H. J. M. (1996). Voicing the self: From information processing to

dialogical interchange. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 3150.Hermans, H. J. M., & Kempen, H. J. G. (1993). The dialogical self: Meaning as

movement. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

17/18

124 D. P. McAdams

Josselson, R. (2004). On becoming the narrator of ones own life. In A. Lieblich,

D. P. McAdams, and R. Josselson (Eds.), Healing plots: The narrative basis ofpsychotherapy(pp. 111127). Washington, DC: American Psychological Asso-ciation Books.

Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (Eds.) (1993). The narrative study of lives. Thou-sand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kermode, F. (1967). The sense of an ending. New York: Oxford University Press.King, L. A., & Raspin, C. (2004). Lost and found possible selves, subjective

well-being, and ego development in divorced women. Journal of Personality,72, 603632.

Labov, W. (1972). Language in the inner city. Philadelphia, PA: University ofPennsylvania Press.

Lieblich, A., McAdams, D. P., & Josselson, R. (Eds.) (2004). Healing plots: Thenarrative basis of psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological As-sociation Books.

Linde, C. (1993). Life stories: The creation of coherence. New York: Oxford Univer-sity Press.

MacIntyre, A. (1981). After virtue. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre DamePress.

Main, M. (1991). Metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive monitoring, andsingular (coherent) vs. multiple (incoherent) model of attachment. In C. M.Parkes, J. Stevenson-Hinde, and P. Marris (Eds.), Attachment across the lifecycle (pp. 127159). London: Tavistock/Routledge.

Mandler, J. (1984). Stories, scripts, and scenes: Aspects of schema theory. Hillsdale,NJ: Erlbaum.

McAdams, D. P. (1985). Power, intimacy, and the life story: Personological inquiriesinto identity. New York: Guilford Press.

McAdams, D. P. (2006). The redemptive self: Stories Americans live by. New York:Oxford University Press.

McAdams, D. P., Diamond, A., de St. Aubin, E., & Mansfield, E. (1997). Storiesof commitment: The psychosocial construction of generative lives. Journalof Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 678694.

Neimeyer, R. A. (Eds.) (2001). Meaning reconstruction and the experience of loss.Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Neimeyer, R. A. & Raskin, J. (Eds.) (2000). Constructions of Disorder. Washing-ton, DC: American Psychological Association.

Nelson, K. (1988). The ontogeny of memory for real events. In U. Neisser andE. Winogard (Eds.), Remembering reconsidered(pp. 244276). New York: Cam-bridge University Press.

Pals, J. L. (in press). Constructing the Springboard Effect: Causal connec-tions, negative experiences, and the growth of self within the life story. InD. P. McAdams, R. Josselson, and A. Lieblich (Eds.), Identity and story: Cre-ating self in narrative. Washington, DC: American Psychological AssociationBooks.

Polkinghorne, D. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany, NY:SUNY Press.

-

7/28/2019 The Problem of Narrative Coherence Dan Mcadams

18/18

Narrative Coherence 125

Raggatt, P. (in press). Multiplicity and conflict in the dialogical self: A life

narrative approach. In D. P. McAdams, R. Josselson, and A. Lieblich (Eds.),Identity and story: Creating self in narrative. Washington, DC: American Psy-chological Association Books.

Ricoeur, P. (1984). Time and narrative (Vol. 1). Chicago, IL: University ofChicago Press, translated by Kathleen McGlaughlin and David Pellaver.

Rosenwald, G. C. (1992). Conclusion: Reflections on narrative self-understand-ing. In G. C. Rosenwald and R. L. Ochberg (Eds.), Storied lives: The culturalpolitics of self-understanding (pp. 265289). New Haven, CT: Yale UniversityPress.

Sampson, R. (1989). The deconstruction of the self. In J. Shotter and K.Gergen (Eds.), Texts of identity (pp. 119). London: Sage.

Sarbin, T. (1986). The narrative as root metaphor for psychology. In T. Sarbin(Ed.), Narrative psychology: The storied nature of human conduct (pp. 321).New York: Praeger.

Sartre, J-P. (1965). Essays in existentialism. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press.Schafer, R. (1981). Narration in the psychoanalytic dialogue. In W. J. J. Mitchell

(Ed.), On narrative (pp. 2549). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Shweder, R. A., & Much, N. C. (1987). Determinants of meaning: Discourse

and moral socialization. In W. M. Kurtines and J. L. Gewirtz (Eds.), Moraldevelopment through social interaction (pp. 197244). New York: Wiley.

Singer, J. A. (2004). Narrative identity and meaning making across the adultlifespan: An introduction. Journal of Personality, 72, 437459.

Spence, D. P. (1982). Narrative truth and historical truth: Meaning and interpreta-tion in psychoanalysis. New York: Norton.

Stewart, A. J., & Malley, J. (2004). Women of the greatest generation: Feel-ing on the margin of social history. In C. Daiute and C. Lightfoot (Eds.),Narrative analysis: Studying the development of individuals in society (pp. 223244). London: Sage.

Tedeschi, R., & Calhoun, L. G. (1995). Trauma and transformation: Growing inthe aftermath of suffering. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Thorne, A., McLean, K. C., & Lawrence, A. M. (2004). When remembering isnot enough: Reflecting on self-defining memories in late adolescence. Jour-nal of Personality, 72, 513542.

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York:Norton.

![Dan McAdams & Olson [2010] Personality Development](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/552bbb8e550346481e8b4579/dan-mcadams-olson-2010-personality-development.jpg)

![[Coherence] coherence 모니터링 v 1.0](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/54c1fc894a79599f448b456b/coherence-coherence-v-10.jpg)