The prison experiences of the suffragettes in Edwardian Britain

-

Upload

felisdemulctamitis -

Category

Documents

-

view

320 -

download

7

description

Transcript of The prison experiences of the suffragettes in Edwardian Britain

This article was downloaded by: [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc]On: 17 April 2013, At: 07:32Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: MortimerHouse, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Women's History ReviewPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwhr20

The prison experiences of the suffragettes inEdwardian BritainJune Purvis aa University of Portsmouth, United KingdomVersion of record first published: 20 Dec 2006.

To cite this article: June Purvis (1995): The prison experiences of the suffragettes in Edwardian Britain, Women's HistoryReview, 4:1, 103-133

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09612029500200073

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematicreproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form toanyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contentswill be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug dosesshould be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions,claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly orindirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

The Prison Experiences of theSuffragettes in Edwardian Britain

JUNE PURVISUniversity of Portsmouth, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT This article focuses in depth upon the prison experiences of thesuffragettes in Edwardian Britain and challenges many of the assumptionsthat have commonly been made about women suffrage prisoners. Thus it isrevealed that a number of the prisoners were poor and working-class womenand not, as has been too readily assumed, bourgeois women. The assumptiontoo that the women prisoners were single is challenged. Married women andmothers as well as spinsters, endured the harshness of prison life. Otherdifferences between the women, such as disability and age, are also explored.Despite such differentiation, however, the women prisoners developedsupportive networks, a culture of sharing and an emphasis upon thecollectivity. Their courage, bravery and faith in the women’s cause, especiallywhen enduring the torture of forcible feeding and repeated imprisonments,should remain an inspiration to all feminists today.

The women’s movement of early Edwardian Britain has attracted theattention of many scholars.[1] In particular, most of the interest has focusedon the ‘militant’ [2] suffragettes, especially those active within the Women’sSocial and Political Union (WSPU), founded on 10 October 1903 by MrsEmmeline Pankhurst and her eldest daughter, Christabel. Yet, as Liz Stanleyand Ann Morley point out, the WSPU was not a single entity; on the level ofpractical feminist politics, the formal dividing barriers between the WSPUand other suffrage organisations – such as the Women’s Freedom League(WFL), the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), theUnited Suffragists (US) and the East London Federation of Suffragettes(ELF) – often broke down.[3] From 1905 until the outbreak of the FirstWorld War in August 1914 about 1000 women were sent to prison becauseof their suffrage activities, most of these being members of the WSPU and ofthe less militant WFL.[4] While these prison ‘experiences’ have not beenignored by historians, they have been discussed as a part of a broaderaccount of the suffrage movement rather than focused upon in depth as a

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

103

Women’s History Review, Volume 4, Number 1, 1995

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

subject worthy of investigation.[5] Furthermore, a dominant narrative ofthese experiences has emerged which has only recently been challenged bysome Second Wave feminist historians. In this dominant narrative, we mayidentify two main themes. First, that the women themselves were to blamefor their often harsh prison experiences, including the pain of hungerstriking and forcible feeding, and secondly, that the prisoners weremiddle-class and single women.

Early histories of the suffrage movement present a more sympatheticpicture of prison life than many subsequent accounts. Metcalfe, for example,writing in 1917, speaks of the “scenes of horror which had taken place inHolloway and other prisons ... in the unavailing effort to govern womenagainst their consent”.[6] However, it is the history written by theconstitutional suffragist, Ray Strachey, a member of the NUWSS and hostileto the WSPU, that became the influential text. Strachey blames the WSPUwomen themselves for the treatment they received from the prisonauthorities with what Dodd has termed “illiberal callousness”.[7] Unwillingto acknowledge the hunger strike as a political tool, Strachey comments howthe suffragettes, once in prison, ceased to be militant and created a numberof protests including the refusal to eat food. “Forcible feeding was tried invain”, she continues; “the prisoners struggled so violently against it that theprocess became actually dangerous, and the prison officials were obliged tolet them starve till they came to the edge of physical collapse, and then to letthem go”.[8] In spite of the severe pain and damage to health which theprocess involved, “scores of suffragettes adopted it ... The officials triedeverything they could think of in vain ...”.[9] This picture of irrationalwomen, deliberately seeking their own torture was eagerly seized upon bymale historians who sought to ridicule the WSPU and its politics.

George Dangerfield’s The Strange Death of Liberal England, firstpublished in 1935, discusses the suffragette movement as one of the forcesin the downfall of the Liberal Party.[10] Describing the movement as a formof “pre-war lesbianism” of “daring ladies”, he suggests that the best way toapproach the campaign for women’s emancipation is “through thewardrobe”.[11] Thus we find references to “high starched collars”, “hardstraw hats”, “long skirts”, “feathered hats” and “corseted bosoms”.[12] Notsurprisingly, Dangerfield too presents the suffragettes as fanatical womenwho chose the hardships of prison life in a sado-masochistic way ... “Howcan one avoid the thought”, he questions, “that they sought these sufferingswith an enraptured, a positively unhealthy pleasure?”[13] If the victim doesnot resist, “forcible feeding is no more than extremely unpleasant. But thesuffragettes were determined to resist”.[14] In view of the fact thatDangerfield’s account contained no footnotes whatsoever to primary sourcesto support his claims, it is incredulous that his analysis was received soenthusiastically and became so influential. The Times and Tribune, forexample, hailed it as “brilliant”.[15] Reprinted, at least up to 1972, it

JUNE PURVIS

104

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

presented a narrative and historical plot from which, as Jane Marcusobserves, subsequent historians have seldom been able to free themselves;as the first ‘historian’, that is male historian, to treat the women’s movement“seriously”, Dangerfield was assured of frequent citation.[16]

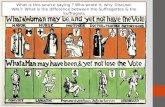

Thus the scene of the drama is set and the props are changed onlywith slight variations. Roger Fulford in 1957 emphasised the middle-classmembership of the WSPU and mocked their prison experiences, claimingthat solitary confinement in prison was “not always unwelcome toadults”.[17] Furthermore, although “forcible feeding is a disgusting topic ...it was not dangerous ... [It] is of course a familiar form of treatment inlunatic asylums”.[18] While Andrew Rosen is much more sympathetic to thewomen prisoners, he too, in a matter of fact way speaks of how forciblefeeding involved mouths being prised open, lacerations, phlegm, vomiting,pain in various organs, loss of weight “and so on”.[19] David Mitchellcompares the WSPU to the German terrorist Baader-Meinhof Gang andsuggests that “like the prison staffs which had to deal with writhing WSPUmilitants, German doctors were sometimes sorely tempted to let theircharges die of hunger if they wished”.[20] Martin Pugh contends that theWSPU, “by driving the Liberals to force-feeding and the ‘Cat and Mouse’Act” (Figure 1), hoped to discredit the government totally in the eyes of itssupporters.[21] Brian Harrison, while admiring the injudicious courage withwhich “respectable Edwardian middle-class women” undertook militancy,facetiously points out that “clumsiness in the prison-doctor during forciblefeeding could destroy woman’s greatest assets, her looks” which werenecessary for what was then seen as her “most important trade,marriage”.[22] And Les Garner, while noting that from April 1913 until theoutbreak of the First World War Mrs Pankhurst was in and out of prison“like a yo-yo – imprisoned and released ten times”, nevertheless adds, “Ifnothing else, suffragette militancy destroyed the myths about the physicalcapabilities of women”.[23]

This dominant narrative was not always challenged in the ‘new’feminist women’s history that was written after the advent of the SecondWave of feminism in Britain, Western Europe and the USA from the late1960s. In particular, in Britain, it was particularly socialist feminists whowere active in researching women’s past. And as socialists for whomcapitalism, not patriarchy, was the key source of women’s oppression, theWSPU was easily dismissed as a bourgeois movement that failed to attractworking-class women and to support working-class causes. SheilaRowbotham, for example, whose 1973 book, Hidden from History: 300years of women’s oppression and the fight against, is commonly regardedas the catalyst for the growth of feminist history in Britain, criticises MrsPankhurst and Christabel for not thinking of mobilising women workers tostrike, “but of making even more dramatic gestures”.[24] The Pankhursts,she asserts, minus the socialist daughter Sylvia, were “quite explicitly on the

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

105

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

side of the ruling class, conservatism and the Empire ... The split wasapparent when Sylvia’s attempt to link the women’s cause to that of theworking class met with her mother’s and her sister’s determinedopposition”.[25] This theme, that the only significant form of struggle is thatagainst class exploitation was especially evident in Liddington & Norris’saccount of the involvement of working-class women in radical suffragistpolitics in early twentieth-century Lancashire.[26] Although condemning theLiberal government’s cruel treatment of the WSPU prisoners, the WSPU isidentified with Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel and presented as a bourgeoisorganisation that during 1906 lost the support of working-class women.[27]

121mm

Figure 1. WSPU poster for the ‘The Cat and Mouse Act’ of 1913 (see note [21])

Critics of this analysis have not been plentiful in Britain, the most sustainedvoice being that of the radical feminists Stanley and Morley, who explore theway the Union operated as a feminist organisation through women’sfriendship networks; furthermore, they emphasise that the WSPU

JUNE PURVIS

106

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

campaigned for an end to a wide range of social ills that particularly affectedworking women, such as sweated labour, low pay, women’s and children’ssexual slavery, and was thus feminist socialist in orientation.[28] Apart fromtheir contribution, it has largely been left to US based feminist historians topresent an alternative picture to the dominant paradigm discussed above.Thus Martha Vicinus offers an insightful analysis of the way the suffragettesbelieved that only by giving their bodies to the women’s cause through suchpublic activities as marching in delegations or processions, selling literature,public speaking – and ultimately, for many, the physical sacrifice of prisonand hunger striking – would they win the necessary spiritual victory thatwould enable them to enter the male political world.[29] Marcus, in contrast,interprets the hunger strike as a “symbolic refusal of motherhood” sincewhen woman, as the quintessential nurturer, refuses to eat she cannotnurture the nation.[30] Mary Jean Corbett argues further that by denyingtheir prescribed reproductive function, suffragette hunger-strikers werecontesting patriarchal definitions of woman-as-mother while alsoappropriating what had been the political tool of other, mostly male,dissenters to make their own argument.[31] All of these feminist histories,however, as well as more recent accounts of the suffrage movement inScotland and Wales, stress the middle-class membership of the WSPU.[32]Furthermore, none of these accounts, like those considered previously, focusin detail on prison life.

The aim of this article is to address this neglect. In particular, bydrawing upon a range of personal texts written by the suffrage prisonersthemselves, such as published autobiographies, unpublished and publishedletters and unpublished and published testimonies, I shall reveal aspects ofthe prison experience that have remained hidden from view.[33] I shall focusespecially, although not exclusively, on WSPU women.

ooo

Although prison conditions might vary, depending on the year in which thesentence was served and upon local variations and personnel, commonadmission procedures stripped the individual of self-identification. On entryto Holloway in 1908, for example, the women were immediately called tosilence by the wardresses, locked in reception cells, and then sent to thedoctor before they were ordered to undress. Once they had been searched tomake sure they concealed nothing, their own clothes were stored by theauthorities and details requested about name, address, age, religion andprofession and whether she could read, write and sew. A bath was thentaken. Although each bather was separated from the next by a partition, lowdoors enabled wardresses to overlook such a private bodily function. Oncedried, the prisoner was told to dress herself from clothes lying in piles on

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

107

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

the floor. Second-class prisoners wore green serge dresses, third-classbrown. All had white caps, blue and white check aprons, and one big blueand white handkerchief a week. Every garment was branded in severalplaces, black on light things, white on dark, with a broad arrow.Underclothing was coarse and ill-fitting; shoes were heavy and clumsy andrarely in pairs while the black thick and shapeless stockings, with red stripesgoing round the legs, had no garters or suspenders to keep them up. On theway to her cell, the prisoner was given sheets for the bed, a toothbrush (ifshe asked for it), a Bible, prayer book and hymn book, a small book on‘Fresh Air and Cleanliness’ and a tract entitled ‘The Narrow Way’. Once inthe cell, which might be about 9 feet high and either about 13 feet by 7 feetor 10 feet by 6 feet (Figure 2), she was given a yellow badge bearing thenumber of her cell and the letter and number of its block in the prison.From now until her release, the inmate would be known only by her cell’snumber.[34]

124mm

JUNE PURVIS

108

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

Figure 2. A cell in Holloway Prison, similar to those occupied by the suffragettes, as it is in the daytime, with the plank bed against the wall and the bedding folded up. Source: Supplement to the Illustrated London News, 7 August 1909.Prison regulations imposed a certain routine on daily life.[35] At this periodin Holloway, for example, a waking up bell rang about 5.30, one andthree-quarter hours before a breakfast consisting of a pint of sweet tea, asmall brown loaf and two ounces of butter (which had to last all day) washanded to the prisoner in her cell. Before the daily half an hour of chapelthe prisoner had to empty her slops, scrub the floor and three planks thatformed her bedstead, fold up the bedclothes into a roll and stow them awaywith the mattress and pillow, and polish with soap and bath-brick the tinutensils of her cell. ‘Inspection’ each day ensured that the task was done inthe required manner. In chapel and at the daily hour of exercise in agravelled yard, talking was not permitted. Lunch was at noon and a supperconsisting of a pint of cocoa with thick grease on top plus a small brownloaf was taken at 5pm. The electric light in the cell was controlled fromoutside and turned off at 8 in the evening.

During the first 4 weeks of imprisonment, the rest of the prisoner’stime was spent in her cell, which was often airless, especially in summer; acertain amount of ‘associated labour’ had to be undertaken, which mightinvolve making nightgowns or knitting men’s socks. Once a week a bath wastaken and twice a week books could be borrowed from the poorly stockedprison library. After 4 weeks, prisoners were allowed to take theirneedlework or knitting to the hall downstairs, which was more airy, and sitside by side, although talking was still forbidden. Those serving one monthor less in the Second Division were not entitled to receive any visits fromfriends nor to have any correspondence with them. Special permission tovisit might sometimes be obtained by making special application to theHome Office or through a Member of Parliament. Those whose sentencesexceeded a month were entitled to a visit at the end of a month, and on thatoccasion not more than three friends were allowed to see the prisoner. Theprisoner was also entitled to write a letter at the end of a month’simprisonment, for which writing materials, in addition to the slates and slatepencils given on admission, were permitted.[36] A reply to that letter mightbe sent to the prison and then given to the prisoner.

While all suffragette prisoners shared with other women inmates thisstructuring of their daily lives (even though the formal rules were frequentlysubverted), their differential status was also apparent. Since it wascommonly recognised that the militants did not belong to the so-called“criminal classes”[37], they were usually segregated from the other womenby being placed in separate cell blocks and being kept separate in communalactivities, such as chapel and exercise. Often too, they were placed in thenewer, lighter cells, as Maud Joachim found when she entered HollowayGaol in 1908 – but this was not always so.[38] Katherine Gatty, of the WFL,in the same jail 4 years later was initially placed in E Block which “was

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

109

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

ghastly! The lavatory accommodation was absolutely inadequate. The wholeblock was infested with mice & co. – there was no heating apparatus at all”.Her relief was enormous when, during the month of March, she wastransferred to another block. “I’m all right now – in D”, she wrote to MrsArney.[39] Mary Nesbitt was another Holloway prisoner in 1912 who foundher cell unacceptable. On one of its dirty walls had been written “‘ThankGod I am going out in two days – had a month for soliciting in Hyde Park’”.Refusing to stay in a room that had been occupied by a prostitute, herrequest for a transfer was “given without delay”.[40] The hierarchy betweendifferent categories of prisoner was also evident in the practice of ThirdDivision women cleaning the cells of those who, for various reasons, wereexempted from doing so. Sylvia Pankhurst, placed in a hospital cell in 1913,exhausted and ill after being forcibly fed, remembered how Third Divisionprisoners scrubbed her cell floor – “old women: pale women: a bright younggirl who smiled at me whenever she raised her eyes from the floor; a poor,ugly creature without a nose, awful to look up”.[41] Such contacts oftenhighlighted for the suffragettes the common bond between all womankindand how they had to work not just for the vote but for a wider range ofissues, including prison reform. The “sweet and innocent-looking face” ofone prison cleaner, just over 20 years of age, made an impression on theyoung Greta Cameron, condemned to a punishment cell for “desiring freshair”. When Greta quietly asked the cleaner what crime she had committed,the reply of “attempted suicide!” so horrified the WSPU member that sheresolved to work for prison reform, after the “needful tool” of the vote waswon.[42]

Above all else, however, the recognition of the suffragettes as ‘notordinary’ inmates was marked by their collective belief in ‘The Cause’, atheme that was articulated by WSPU leaders and rank and file membersalike. Emmeline Pankhurst, the much loved leader of the WSPU, implored in1909:

Women! Comrades! Dear Fellow-workers! I charge you, love thisMovement, work for it, live for it. Let no thought of your own comfortand happiness hinder you from rendering it your whole service. Give ityour thought, your time, your all. It is worth everything that you cangive.[43]

For Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, treasurer of the WSPU and one of itsleaders until ousted by Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel in 1912, women of theupper, middle and working classes found a “new comradeship with eachother” in the suffrage cause. “Neither class, nor wealth, nor educationcounted any more”, she claimed, “only devotion to the common ideal”.[44]Although by 1912, when the more extreme forms of militancy were common,there was a marked decline in the rate of new members joining theWSPU[45], time and time again suffragette prisoners testified that theyendured the hardships of prison life because they believed in the women’s

JUNE PURVIS

110

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

movement, the feeling of collectivity that was fostered, the common bondthat united all women and the dignity of women to stand up and fight forwhat they believed in.

Patricia Woodlock, honorary secretary of the Liverpool branch of theWSPU and imprisoned many times, did not hesitate “to put the welfare ofher sex before her own freedom”.[46] Emily Wilding Davison, imprisonedeight times, stressed that the perfect militant warrior “will sacrifice all ... towin the Pearl of Freedom for her sex”.[47] Daisy Dorothea Solomon saw herprison life as a “baptism to work for the uplifting of womanhood”.[48] EthelSmyth remembered with affection those women “forgetful of everything savethe idea for which they had faced imprisonment”.[49] Kathleen Emerson,while serving her sentence in 1912, expressed her feelings in poetry:

THE WOMEN IN PRISONOh, Holloway, grim Holloway,With grey, forbidding towers!Stern are they walls, but sterner stillIs woman’s free, unconquered will.And though to-day and yesterdayBrought long and lonely hours,Those hours spent in captivityAre stepping-stones to liberty.[50]

Mary Nesbitt, coming out of jail in the same year, emphasised, “I was deeplyimpressed by the wonderful spirit of loyalty and love for the cause and forour leaders – all, irrespective of class, creed or age, were unwavering”.[51]For these women and many more, ‘The Cause’ was like a religion and theparticipants a “spiritual army” who sought a new way of life.[52] AsElizabeth Robins, the well-known actress, writer and WSPU membercommented, “the ideal for which Woman Suffrage stands has come, throughsuffering, to be a religion. No other faith held in the civilised world to-daycounts so many adherents ready to suffer so much for their faith’s sake”.[53]

This faith in the movement helped the forging of a community spiritand supportive networks amongst the women prisoners so that they were,what one WSPU member termed “a sympathetic family helping each other toendure”.[54] Various activities organised by the prisoners both expressedthis sense of belonging and helped to maintain it. In Holloway in 1912, on achilly May morning in the exercise yard, the women played “Here we comegathering nuts and may on a cold and frosty morning” with Mrs Pankhurstand Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence joining in the game.[55] Football wasplayed too, and with especial vigour by Emily Wilding Davison who becamevery hot and tired.[56] Various entertainments, such as singing, story tellingand reading aloud, also took place.[57] Even a sports day was held, completewith prizes, and considered by Margaret Thompson as more enjoyable thanVera Wentworth’s impersonation, with a button in her eye, of LordCromer.[58] A scene from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice was

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

111

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

performed, with Miss Grey as the Duke, Hilda Burkett as Shylock, DoreenAllen as Narissa, Mrs Field as Gratiano, Miss Mitchell as Antonia, and MrsBard as Bassanio.[59] All suffrage prisoners, including those who weremembers of the WFL, joined in the activities. Katherine Gatty, a Leaguemember friendly with Emily Wilding Davison, observed that her fellowprisoners played everything imaginable, “like a lot of small children &sometimes so roughly that now & again someone gets rather badly hurt,with a sprained wrist or ankle”. Furthermore:

One day we had – that was rather pretty & very clever – a Fancy DressBall. The girl who put on a brown paper hat & folded her arms likeNapoleon, was most clever ... Another day we had a contested generalelection, using our slates as sandwich men. The candidates (four girls)were “chained” – the aged electors ... we carried to the poll. The ...speeches, the election addresses, the canvassing & (I regret to say) thebribery & corruption were all realistic![60]

The group cohesion and emotional support so evident in these activitiescould also extend to the many ways the formal rules were broken by, forexample, hiding written notes in stockings and passing them secretly to eachother in church services on Sundays.[61]

The knowledge that WSPU members ‘outside’ were sending thoughtsof comfort and also demonstrating in a more noisy way around or near theprison walls reinforced the sense of solidarity. In her address at the weekly‘At Home’ of the WSPU at Queen’s Hall on Monday 6 November 1908, forexample, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence announced that a fresh demonstrationon a larger scale than previously would be made to Holloway the followingSaturday. “Singers, sellers and sewers wanted!”, she pleaded – the singers toform a choir, the sellers to distribute suffrage literature and the sewers tomake some imitation prison clothes for released prisoners to wear.[62] Suchdemonstrations, with bands playing ‘The March of the Women’ and thecrowd singing The Marseillaise could be “very cheering” to the lonelysuffragette prisoner, locked in her cell at night.[63] Indeed, as Mrs MarieLeigh, a working-class woman from Birmingham and the first suffragette tobe forcibly fed, pointed out, “it was all the Heart beats, thoughts & lovewhich were just concentrated on us from outside that enabled us to Hold onHold fast & Hold Out”.[64]

However, despite the sense of unity and friendship the suffragettes feltas they faced the common external reality of prison life, their sharedexperiences were not experienced equally but fractured on a number ofdifferences. This is not surprising given the complexity of women’s liveswithin a radical women’s political movement that was both in opposition to,and yet a part of, an Edwardian culture that expected women to be ideallylocated within the private sphere of the home rather than the male world ofpolitics. Differences would also be accentuated by the fact that hungerstriking and force feeding were acts committed by, and on, individuals in

JUNE PURVIS

112

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

their own cells. Whether force fed by a cup, tube through the nostril (themost common method) or tube down the throat into the stomach (the mostpainful), the individual suffragette struggled on her own and often feareddamage to the mind or body. Kitty Marion’s screaming in prison greatlyupset the other women, but she found it was the only way she could fightagainst the torture of forcible feeding and remain sane.[65] Rachel Peace, anembroideress, who had already experienced several nervous breakdowns,was not so fortunate. During a period of prolonged hunger striking andforcible feeding three times a day she feared, “I should go mad ... Olddistressing symptoms have re-appeared. I have frightful dreams and amstruggling with mad people half the night”.[66] Her fears became true whenshe “lost her reason in prison” and spent the rest of her life in and out ofasylums, with Lady Constance Lytton, an upper-middle-class WSPU worker,maintaining her.[67] The forcible feeding of the disabled May Billinghurst inHolloway in January 1913 brought a particular wave of revulsion since shewas “small, frail, and ha[d] been a cripple all her life”.[68] Paralysed as achild and confined to a tricycle for mobility[69], she told how the threedoctors and five wardresses who held her down:

forced a tube up my nostril; it was frightful agony, as my nostril is small.I coughed it up so that it didn’t go down my throat. They then weregoing to try the other nostril, which, I believe is a little deformed. Theyforced my mouth open with an iron instrument, and poured some foodinto my mouth. They pinched my nose and throat to make meswallow.[70]

After 10 days of “almost incredible suffering”, when she was fed three timesevery 24 hours, she was released “a physical wreck”.[71] MargaretThompson, in prison in 1912, had a facial disability, resulting from a caraccident; after examining her face to see if it was “fit” for forcible feeding,the doctor decided she should be fed by the cup rather than the tube.[72]Miss McCrae, in prison at the same time, thought she too should take foodthrough the cup, on account of her deafness, although she feared the otherwomen would scorn her for doing so.[73] For women with disabilities suchas those mentioned here, imprisonment and forcible feeding were particularacts of courage.

Age, too, would be another possible line of difference. The threegrandmothers, Mrs Heward, Mrs Boyd and Mrs Aldham, in Holloway in1912, as well as the 78 year-old Mrs Brackenbury, may have found prisonlife especially tiring.[74] And older women generally may have been moreprone to accidents. A tall suffragette, “by no means young”, tripped and fellin a frosty exercise yard one morning and broke several bones – althoughthis was not discovered until the day before her sentence expired.[75] It ishighly probable that few teenagers became prisoners since Mrs Pankhursthad an “inflexible rule” that no one under 21 years old should do anythingthat might incur a prison sentence.[76] Nevertheless, there were a number of

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

113

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

women prisoners in their mid-twenties and thirties who may have had moreenergy and agility than their more ‘mature’ sisters. However, those womenstill menstruating may have found their monthly cycle an inconvenience,especially when the supply of sanitary towels was inadequate. Phyllis Keller,in Holloway in 1912, found none available and so her mother sent to hersome of “the old fashioned, washable sort” while also using the opportunityto hide in the box a small ball with which the women would play.[77]Despite the importance of such factors as age and disability in fracturingprison experiences, personal accounts written by suffragette prisoners revealthat the most commonly recorded differences related to marital status, socialclass background and rank within the WSPU.

It is commonly assumed that the majority of suffragette prisoners weresingle rather than married women.[78] Of the 108 women arrested for stonethrowing after a demonstration to the House of Commons on 29 June 1909,for example, 80 were termed ‘Miss’ and 26 ‘Mrs’.[79] Yet there were, as weshall see, a number of married prisoners too, often with children, although itis difficult to quantify their number. However, whether married or not, thewomen were not separated from their lives outside the prison: the sexualpolitics of home, work and politics could intermesh with prison life incomplex yet different ways.[80]

Single women may have worried about employers, parents, friends andlovers, and some might have had dependants. The 80 single women arrestedand imprisoned for stone throwing on 29 June, included a number engagedin paid work – Miss Ivy Beach and Nellie Godfrey were both businesswomen; Sarah Carwin, Helen Grace Lenanton, Rachael Graham and EllenPitman were nurses; Millicent L. Brown, Alice E. Burton, Emily WildingDavison, Florence T. Down, Elizabeth Roberts, Irene Spong and Alice M.Walters were teachers; Kitty Marion an actress; Katheleen Streatfield anartist; Jessica Walker a portrait and landscape painter; and Harriet Rozier “atypical working woman, having had to earn her bread since she was nineyears old”.[81] Employers may not have looked kindly upon such behaviour,especially when it involved the inconvenience of ‘absenteeism’. Florence T.Down, for example, was a supply teacher in the elementary sector and had 2days’ pay withheld from her when her case was adjourned, a loss she couldbarely afford since she was “the eldest of seven at that time – and a greatdeal depended on me”.[82] Elementary schoolteachers, of course, wereparticularly vulnerable to hostility since their salaries were paid out of publicfunds.[83] Elsa Myers, a London County Council teacher somewhere inNorth London, arranged to be arrested on the last day of the summer termin order to keep her militant activity “unknown to the authority”. Thus shespent her summer vacation in jail and was released in time ready for thestart of the new term.[84] Kitty Marion, the actress, could find that even onenight in a cell, resulting in one missed performance, was sufficient to“damage” chances of future employment; the one member of the AFL who

JUNE PURVIS

114

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

was repeatedly arrested and imprisoned, she was eventually forced to giveup her theatrical career.[85] And countless more single women faced a rangeof other personal issues, including the pressure to hide their true identityunder a fictitious name. Agnes Olive Beamish, for example, along with ElsieDuval, was sentenced to 6 weeks’ imprisonment in April 1913 for being a“suspected person or reputed thief” when, both having lost their way in theearly hours of the morning, they were arrested on the street in possession ofparaffin and other incendiary materials carried in suitcases. Olive wasconvicted under the name of ‘Phyllis Brady’.[86]

Worries about dependants and parents must also have been commonfor single women. Dora Montefiore, a widow, found the visit of her daughterwho was pregnant with her first child and far from strong a bitter-sweetexperience. “I could not bear that she should see me, her mother, in prisondress”, wrote Dora in her autobiography.[87] She worried, too, about howshe could send money to her son who was entirely dependent upon herfinancially for his engineering studies:

The end of the month was approaching, and I had had one or twosleepless nights in prison wondering how I should send him hisallowance which was due at the end of the month, and wishing at thesame time I might be able to send him a message of love and of sorrowfor the trouble I knew I was causing him by the publicity of myactions.[88]

When Miss Charlotte Marsh was serving a 3 month prison sentence inWinson Green Prison in 1909, during which she was tube-fed 139 times, herfather became dangerously ill. Although the prison authorities knew of hisillness, they did not release Charlotte until 9 December, one day after theyreceived the news that he was dying. Travelling straight to Newcastle bytrain, she found her father unconscious. He died without recognisingher.[89] Alison Neilans, of the WFL, planning a hunger strike, smuggled outa note to Edith How-Martyn in December of the same year. “I have decidedon the ‘All’”, she confessed, “& have commenced the secret fast todayMonday 27th”. She implored her friend not to worry nor to enquire abouther, unless she became ill. “Don’t tell Mother yet”, was another plea, “but letPeter know”.[90] It was probably the rare suffragette – and yet there weresome – who felt that she had no one to worry about and no one to worryover her. Such circumstances, as with Mary Richardson, may have helpedthe unmarried WSPU member to become one of the more militant ‘guerrillaactivists’, engaging in bombing empty buildings and in arson:

What brought me some relief, personally, was the knowledge I belongednowhere; I had no home, and so there was nobody who would worryover me and over whom I need worry. From the start it had been thisknowledge that had made me feel I must do more than my fair share tomake up for the many women who stood back from militancy because

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

115

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

of the sorrow their actions would have caused some loved one. It wouldhave been the same with me had I been in their position. For anyonewho loved me to have suffered on my account would have been anunbearable thing.[91]

Contrary to the popular view[92], a number of married women did enterprison, although not always under their married name. Mrs Frances ClaraBarlett, for example, conscious of her “husband’s position”, decided to serveher month’s imprisonment as Frances Satterley, her maiden name.[93]Wives and mothers, especially those with small children, were likely to beanxious about how their families coped in their absence. Minnie Baldock, aWSPU organiser and wife of a fitter in Canning Town, was sentenced to onemonth’s imprisonment in February 1908. Her anxieties about her small son,left at home with his father, might be somewhat alleviated by the knowledgethat Union members outside would offer help. Julie East’s invitation toMinnie’s husband to bring the boy over to her one Sunday so she couldhave “lent him books & known more that he liked” was not realised,however, since Mr Baldock was unable to come and Julie East herself hadbeen “very poorly”.[94] Maud Arncliffe Sennett, on the other hand, arelatively wealthy Union member, sent the child some presents – much to hisdelight:

Dear LadyThank you very much for the toys you sent me. I am proud of mymother. I will be glad when She comes out of prison But I now [sic] Sheis there for a good cause. I am saving up all my farthings to put in thatmoney box you was kind enough to send me. I will send it on as soonas I get it full. For the cause. I am writing this letter with your nibs yousent me. Again thanking you for sending me so many nice presentswhich amuse me very much.I remain greatfully [sic] yours J. Baldock.[95]

Mrs Baldock, like other working-class women, would not be able to afford topay for alternative child care while she was in jail and would have to rely onthe goodwill of her husband and neighbours. But even when a prisoner didhave domestic help at home, the worries about the family were still acute. Atypical example is that of Myra Sadd Brown writing to her husband fromHolloway on 16 March 1912. She had discovered in her bag a photograph ofher children and now kissed them every night and was glad that they werealways looking at her. “Let them know a little where I am so that they cansend their loving thoughts to me”, she pleaded, “they need not thinkbecause I am shut up I have done wrong”. When she got into her narrowbed at night her thoughts however flew to her husband “& your strongloving arms”.[96] Her undated letter to her children and Mademoiselle,

JUNE PURVIS

116

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

written on dark brown lavatory paper, probably 6 days later, is especiallypoignant:

My three little Darlings & MlleMummy thanks you ever so much & also Mlle for the letters – theywere such a joy & I wanted to kiss them all over – but I am going tokiss all the writers when I see them & I don’t think there will be muchleft when I have finished. I have got such a funny little bed, which I canturn right up to the wall when I don’t use it. I am learning French &German so you must work well or Mummy will know lots more thanyou. Next time you see Granny I want you to give her a big kiss andhug from me with lots of love – Now 1. 2. & 3 it is Mummy’s bed time –so goodnight ... Lots of love & kissesMummy

Mrs Pankhurst thinks there is enough evidence against her to give her7 years.

Don’t forget Matilda’s bedstead.[97]

Some weeks earlier, on 24 February 1912, Mrs Alice Singer, married withtwo small daughters, Mary and Christabel, had written to the WSPU officesto offer herself as a window breaker. After she committed the deed, she wasarrested. On 2 March 1912, while at Bow Street Police Station, she wrote toher husband and youngest child, Mary, “Perhaps you will not see me forsome weeks. That is why I thought I would write”. She also worried aboutMrs Lane, who sat next to her and whose “boys & Tom Rowat are so proudof her; but Col. Lane is very angry”. She entreated her family to try toalleviate the tensions in the Lane household. “You must cheer the boys up;& perhaps you, Daddy, can make their Daddy more reasonable”.[98]Another window breakerr, Mrs Hudleston, serving 6 months in BirminghamGaol, developed “excessive anxiety” at being separated from her smalldaughter who had developed tubercular glands, which might need anoperation. The anxious parent petitioned the Home Office for release oncondition of being bound over for a reasonable period, and was told that thepetition would only be granted if she consented to be bound over forlife.[99] As all these accounts by single and married women reveal, prisonlife could be interwoven with a range of duties as wage or salary earners,daughters, friends, wives and mothers.

It is commonly assumed that suffragettes were middle-class women,“the educated and well-to-do”.[100] Obviously working-class women, espec-ially in comparison with leisured middle- and upper-class women, would haveless time and money to give to ‘The Cause’. Hannah Mitchell, a working-classwife and mother and member of the WSPU in its early years, travelled downfrom Manchester to join the demonstration to the House of Commons on 23October 1906. Coming back home on the midnight train, tired and

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

117

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

exhausted, she knew that “arrears of work, including the weekly wash”awaited her return. Working housewives, she mused, faced with such anaccumulation of tasks, often resolved never to leave home again.[101] Yetdespite such difficulties, a number of poor WSPU women, like MinnieBaldock, served prison sentences. Indeed, even by 1912, 9 years after theWSPU was founded, Ethel Smyth found in Holloway more than a hundredwomen, “rich and poor ... young professional women ... countless poorwomen of the working class, nurses, typists, shop girls, and the like”.[102]These working-class women would have to rub shoulders with their moreelevated sisters, such as Miss Janie Allan, a millionairess of the Allan Line,Lord Kitchener’s niece Miss Parker, several cousins of Lord Haig’s, MrsBarbara Ayrton Gould (daughter of Hertha Ayrton, the scientist whoinvented the safety lamp for miners) and Alice Morgan Wright, an Americansculptress.[103]

The official line of the prison authorities was that all prisoners weretreated alike, irrespective of their class background, a claim of which somein the WSPU became very suspicious. Lady Constance Lytton, anupper-middle-class spinster, believed she had received preferential treatmentin Newcastle Prison when, on hunger strike in October 1909, she was notforcibly fed and released after only 2 days, officially because of her heartcondition. Although Constance did indeed have a weak heart and had been,in her own words, “more or less of a chronic invalid” throughout the greatpart of her youth [104], she felt that her family background and politicalconnections (her brother was the Earl of Lytton and a member of the Houseof Lords) had influenced the prison authorities; lesser known women andwomen in poorer health than she had been imprisoned longer and forciblyfed. An incident later in the year confirmed her doubts. On 21 December,Selina Martin, a working-class woman of “high character” [105], wasarrested and remanded for a week in Walton Gaol, Liverpool, bail beingturned down. Refusing to eat prison food, she and another working-classwoman, Leslie Hall, were forcibly fed – despite the fact that it was contraryto the law for remand prisoners to be treated in this way. After being kept inchains at night, Selina was frog-marched up the steps to a cell where shewas forcibly fed again. Since frog-marching involved seizing her arms andlegs and carrying her head downwards, her head bumped on each step. Thebrutality of the incident was reported in many of the major newspapers andon the front page of the 7 January 1910 issue of Votes for Women.

Constance, in Manchester at the time, shared her concerns with adistressed Mary Gawthorpe, another Union worker, who confided that thewomen were “quite unknown – nobody knows or cares about them excepttheir own friends. They go to prison again and again to be treated like this,until it kills them!” Constance determined to try out whether the prisonauthorities would recognise her need “for exceptional favours” if they didnot know her name.[106] Thus, after some elaborate planning, including

JUNE PURVIS

118

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

removing her own initials from her underwear, she assumed the guise of‘Jane Warton’, a working woman, and rejoined the WSPU under her newname. With her hair cut short and parted in early Victorian fashion, a tweedhat with a bit of tape saying “Votes for Women” interlaced with the hatband,woollen scarf and gloves, a pair of pince-nez spectacles, and small chinaportrait brooches of Mrs Pankhurst, Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and ChristabelPankhurst pinned to the collar of a long green coat costing 8s. and 6d, ‘JaneWarton’ protested against forcible feeding outside Walton Gaol – and wasarrested.[107] Sentenced to a fortnight in the Third Division, she went on ahunger strike.

140mm

Figure 3. A WSPU poster reproduced in Votes for Women, October 1909, p. 68.

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

119

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

Before the first forcible feeding, neither her heart was examined nor herpulse felt. After a struggle, the doctor managed to insert a steel gag whichfastened her jaws wide apart, far more than they could go naturally, andcaused intense pain. Then:

he put down my throat a tube which seemed to me much too wide andwas something like four feet in length. The irritation of the tube wasexcessive. I choked the moment it touched my throat until it had gotdown. Then the food was poured in quickly; it made me sick a fewseconds after it was down and the action of the sickness made my bodyand legs double up, but the wardresses instantly pressed back my headand the doctor leant on my knees. The horror of it was more than I candescribe. I was sick over the doctor and wardresses, and it seemed along time before they took the tube out. As the doctor left me he gaveme a slap on the cheek, not violently, but as it were, to express hiscontemptuous disapproval.[108]

This scene was repeated another seven times before Constance’s trueidentity was discovered and she was released. Although she had proved herpoint about the differential prison treatment of women from differing socialbackgrounds, she never fully recovered from her ordeal, but suffered astroke in 1912 and died in 1923.

Social class differences between women prisoners were also apparentnot just in the different ways they were treated by the prison authorities butin the differing class experiences and expectations of the women themselves.The new prisoner, Zoë Proctor, expected her bed to be made for her, muchto the amusement of the ‘old-timers’ around her.[109] Margaret Thompson,on her first imprisonment in February 1909, found that:

The scrubbing of my floor was a new experience. I was toiling away at itwhen a wardress came and looked on disapprovingly. ‘What have youbeen doing to the floor of your cell, 27?’ ‘I have been attempting toscrub it’, I answered. ‘I think it is an attempt’ was the sneering reply.Then she showed me how to wring out the flannel and remarked ‘Youmust do it better another time’.[110]

A parlour maid in Holloway with Margaret at this time, Miss Walsh, may nothave needed such instruction. She seemed “to keep to herself ... and wasconscious ... of not always knowing what good form was, and that kept herquiet and retiring”.[111]

Class differences between women prisoners may have become moreaccentuated after 15 March 1910 when Rule 243a was added to theregulations governing prison life. The new rule, framed with the suffragettesin mind, permitted the Secretary of State to approve “ameliorations ... inrespect of the wearing of prison clothing, bathing, hair-curling, cleaning ofcells, employment, exercise, books, and otherwise”.[112] Under the new rule,the wealthy Miss Allen was always “correctly dressed” for prison exercise,

JUNE PURVIS

120

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

and wore a hat and lemon kid gloves.[113] Under the new rule too, friendsand relatives outside, could send in extra food. Phyllis Keller asked hermother to send parcels of fruit and “a hamper with enough for three mealstwice a week”; on the other days she would eat prison food.[114] Thepotential of such gifts for splintering the sense of collectivity amongst theinmates was mitigated by the practice of those militants ‘outside’ organisingmoney collections for prisoners’ hampers and of those ‘inside’ sharing anyfood that was sent in. In 1912, for example, Mrs A. E. Gordon of 16Daleham Gardens, Hampstead, thanked those who had sent money inresponse to her appeal for funds for prisoners’ hampers. Those who gavemoney included Mrs M. Pollock, 10s; Miss Evelyn Sharp, £1.1s; Miss A.Clifford, 1s 6d; Mrs Saul Soloman, 10s 6d; and Miss Morice, 2s.[115] InHolloway in June 1912, Margaret Thompson went round distributing “muchpraised” shortbread while Miss Allan put cake, strawberries and cherries onher plate.[116] The arrival of another parcel from Ilkley, this time containingpressed beef and a large veal roll, was also shared.[117]

It was at this time, too, that the suffragette prisoners had anotherlesson in the ways the prison authorities could offer ‘preferential’ treatmentto certain of their members, on this occasion according to their rank withinthe WSPU. When Mrs Pankhurst, and Emmeline and FrederickPethick-Lawrence were sentenced on 22 May 1912 to 9 months in theSecond Division, they had all proclaimed their intention of hunger strikingunless they were accorded the normal rights of political offenders andtransferred to the First Division. Five days after their removal there, on 15June, the WSPU held a meeting at the Albert Hall where Mabel Tukeannounced that if the government did not transfer all 75 WSPU memberscurrently in prison also to the First Division, all, including the leaders, wouldhunger strike.[118] The audience cheered when she told them that messagesfrom the prisoners in Holloway, Winson Green Prison, Birmingham, andAylesbury Prison, would now be read out. The sense of collectivity that theWSPU inspired amongst its members was typically expressed by the WinsonGreen prisoners:

Give our love to all our friends, and tell them we long to join them intheir strenuous work out-side. Meanwhile, we are playing our part withundaunted spirits. Our hearts go out in love and sympathy to our braveleaders, and we are ready to face whatever lies before us and fight withall our strength to win for them and for all who come after us thestatus of political offenders.[119]

When the Government refused to transfer all suffragette prisoners to theFirst Division, the threatened hunger strike began on 19 June. FrederickPethick-Lawrence was force fed five times, his wife once. Mrs Pankhurst,lying in bed, very weak from starvation, was in the cell next to EmmelinePethick-Lawrence when she heard a sudden scream come from her friendand then the sound of a prolonged and very violent struggle. “I sprang out

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

121

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

of bed”, Mrs Pankhurst recalled in her autobiography, “and, shaking withweakness and with anger, I set my back against the wall and waited for whatmight come”.[120] When the doctors and wardressess appeared at her door,she grabbed a heavy earthenware water jug on a nearby table and cried, “Ifany of you dares so much as to take one step inside this cell I shall defendmyself”. The group retreated.[121]

By 6 July, all the hunger strikers had been released, including 545women who were freed before their sentences had expired.[122] This wasthe last attempt made by the prison authorities to forcibly feed EmmelinePankhurst. The Government was too worried about her possible death ontheir hands, and thus instant martyr status, to dare attempt such an assaultagain.[123]

Unlike well-connected women and high-ranking women within theWSPU who might receive ‘privileged’ prison treatment, unknown andoccasionally well-known women from the rank and file shared alike,irrespective of their social class background, the torture of forcible feeding.As we saw earlier, the first woman to be forcibly fed, in October 1909, was arank and file member from Lancashire, a working woman of “sturdyconstitution”, Mrs Marie or Mary Leigh.[124] Nurse Ellen Pitfield, alsoforcibly fed in 1909, was a poorly paid midwife.[125] In the summer of 1914,Mary Richardson, a relatively unknown middle-class woman who hadachieved notoriety by slashing the painting of the Robeky Venus in theNational Gallery earlier in the year, was a ‘mouse’ on an expired licence,evading arrest, when she was caught and convicted of arson. Back inHolloway, she was too tired and dejected to offer any resistance “physical ormental” to the first attempt to forcibly feed her.[126] Afterwards, lyingexhausted on her bed, she could barely acknowledge her old cleaner whobent over her, the smell of the dirty water in her bucket making Mary feelnauseous. The following week, when some of Mary’s strength returned andshe resisted the forcible feeding with “almost superhuman strength”, sternertactics were used. In a ju-jitsu hold, a small wardress threw her to the floorand then immobilised her by burrowing her thumbs into Mary’s neck anddrawing the pointed end of a large key up and down the soles of herstockinged feet. Thus “utterly passive, prostrate and amenable”, the onlydifficulty the doctors encountered was forcing the stiff end of the tube intoher swollen nostril.[127]

For many of these women, the worst feature of prison life was the‘public’ violation of their bodies when being forcibly fed. Helen GordonLiddle hated the lack of privacy when enduring the pain of forcedfeeding.[128] Nell Hall spoke of the “frightful indignity” of it all.[129] ForSylvia Pankhurst, the sense of degradation endured was worse than the painof sore and bleeding gums, with bits of loose jagged flesh, the agony ofcoughing up the tube three or four times before it was successfully inserted,the bruising of her shoulders and the aching of her back.[130] Sometimes,

JUNE PURVIS

122

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

when the struggle was over, or even in the heat of it, she felt as though shewas broken up into many different selves, of which one, aloof and calm,surveyed all the misery, and one, ruthless and unswerving, forced the weak,shrinking body to its ordeal. Although the word ‘rape’ is not used in thepersonal accounts of force fed victims, the instrumental invasion of thebody, accompanied by overpowering physical force, great suffering andhumiliation was akin to it [131], especially so for women fed through therectum or vagina. ‘Janet Arthur’, later identified as Fanny Parker, in Perthprison in 1914, was one such victim:

Thursday morning, 16th July ... the three wardresses appeared again.One of them said that if I did not resist, she would send the othersaway and do what she had come to do as gently and as decently aspossible. I consented. This was another attempt to feed me by therectum, and was done in a cruel way, causing me great pain.

She returned some time later and said she had ‘something else’ to do. Itook it to be another attempt to feed me in the same way, but it provedto be a grosser and more indecent outrage, which could have beendone for no other purpose than torture. It was followed by soreness,which lasted for several days.[132]

When released, a medical examination revealed swelling and rawness in thegenital region.[133] The knowledge that new tubes were not always availableand that used tubes may have been previously inflicted on diseased personsand the mentally ill or be dirty inside the tube, issues that had been openlydiscussed in Votes for Women[134], undoubtedly added to the feelings ofabuse, dirtiness and indecency that the women felt.

On 10 August 1914, on the outbreak of the First World War, theGovernment ordered all persons serving prison sentences for suffrageagitation to be released.[135] Three days later, Mrs Pankhurst called an endto all militancy ... ” it has been decided to economise the Union’s energiesand financial resources by a temporary suspension of activities”.[136] Thisnews must have been greeted with mixed feelings by WSPU activists, gladthat their guerrilla activities would end, sad at the prospect of slaughter thatwar would bring and disappointed that all their efforts had still not won thevote for women. Mary Richardson and other ‘battle-worn’ suffragettes weredelighted to see the last of the policemen and detectives – as they were tosee the last of them.[137] Elsie Bowerman greeted the declaration of warwith almost “a sense of relief ... as we knew that our militancy, which hadreached an acute stage, could cease and we could devote ourselves entirelyto the service of our country”.[138]

ooo

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

123

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

This account of the prison experiences of the suffragettes in EdwardianBritain has revealed that historians have too readily assumed that thewomen were ‘bourgeois’. As we have seen, a focus on the suffrage prisonexperience offers an introduction to the poor, and not simply the workingclass. Furthermore, the common assumption that the women prisoners weresingle women is not valid. Mothers with children endured the harshness ofprison life as well as single women. Despite these and other ‘differences’,however, the prisoners developed supportive networks and a culture ofsharing. In particular, their insistence upon the collectivity holds animportant lesson for feminists today. As they knew, to emphasise ourdifferences at the expense of our commonalities, is to re-radicalise ourpolitics and to weaken the potential alliances between all women. Theircourage, bravery and faith, particularly when enduring the torture of forciblefeeding and repeated imprisonments, remains an inspiration to us all.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the two referees for this journal who commented onprevious drafts of this article which was accepted for publication in 1993.Any errors, however, remain my own. Some of the material presented herehas been discussed in June Purvis (1994) Doing feminist women’s history:researching the lives of women in the suffragette movement in EdwardianEngland, in Mary Maynard & June Purvis (Eds) Researching Women’s Livesfrom a Feminist Perspective, pp. 166-189 (Basingstoke: Taylor & Francis).

Notes

[1] See, for example, Ray Strachey (1928) ‘The Cause’, a short history of thewomen’s movement in Great Britain (London: G. Bell & Sons); E. SylviaPankhurst (1931) The Suffragette Movement, an intimate account of personsand ideals (London: Longmans, Green & Co.); Roger Fulford (1957) Votes forWomen, the story of a struggle (London: Faber & Faber); ChristabelPankhurst (1959) Unshackled, the story of how we won the vote (London:Hutchinson); Josephine Kamm (1966) Rapiers and Battleaxes, the women’smovement and its aftermath (London: George Allen & Unwin); ConstanceRover (1967) Women’s Suffrage and Party Politics in Britain 1866-1914(London: Routledge & Kegan Paul); David Mitchell (1967) The FightingPankhursts, a study in tenacity (London: Jonathan Cape); Antonia Raeburn(1973) The Militant Suffragettes (London: Michael Joseph); Jill Liddington &Jill Norris (1978) One Hand Tied Behind Us, the rise of the women’s suffragemovement (London: Virago); Brian Harrison (1978) Separate Spheres: theopposition to women’s suffrage in Britain (London: Croom Helm; MartinPugh (1990) Women’s Suffrage in Britain 1867-1928 (London: The HistoricalAssociation, pamphlet); Leslie Parker Hume (1982) The National Union ofWomen’s Suffrage Societies 1897-1914 (New York and London: Garland

JUNE PURVIS

124

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

Publishing); Brian Harrison (1982) The act of militancy, violence and thesuffragettes, 1904-1914, in his Peaceable Kingdom, stability and change inmodern Britain, pp. 26-81 (Oxford: Oxford University Press); Brian Harrison(1983) Women’s suffrage at Westminster, 1866-1928, in Michael Bentley &John Stevenson (Eds) High and Low Politics in Modern Britain (Oxford:Oxford University Press); Les Garner (1984) Stepping Stones to Women’sLiberty, feminist ideas in the women’s suffrage movement 1900-1918(London: Hutchinson); Sandra Stanley Holton (1986) Feminism andDemocracy, women’s suffrage and reform politics in Britain 1900-1918(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press); Susan Kingsley Kent (1987) Sex andSuffrage in Britain 1860-1914 (New Jersey: Princeton University Press); LisaTickner (1987) The Spectacle of Women, imagery of the suffrage campaign1907-14 (London: Chatto & Windus); Jane Marcus (Ed.) (1987) Suffrage andthe Pankhursts (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul); Linda Walker (1987)Party political women: a comparative study of Liberal women and the PrimroseLeague, 1890-1914, in Jane Rendall (Ed.) Equal or Different, women’s politics1800-1914, pp. 165-191 (Oxford: Basil Blackwell); Liz Stanley with Ann Morley(1988) The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison: a biographicaldetective story (London: The Women’s Press); Katrina Rolley (1990) Fashion,femininity and the fight for the vote, Art History, 13 March, pp. 47-71; ClaireHirshfield (1990) A fractured faith: Liberal Party women and the suffrage issuein Britain, 1892-1914, Gender and History, 2, pp. 173-197; Sandra StanleyHolton (1990) ‘In sorrowful wrath’; suffrage militancy and the romanticfeminism of Emmeline Pankhurst, in Harold Smith (Ed.) British Feminism inthe Twentieth Century, pp. 7-24 (Aldershot: Edward Elgar); Hilda Kean (1990)Deeds not Words: the lives of suffragette teachers (London: Pluto Press); LeahLeneman (1991) A Guid Cause, the women’s suffrage movement in Scotland(Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press); Rowena Fowler (1991) Why didsuffragettes attack works of art? Journal of Women’s History, 2, pp. 109-125;Kay Cook & Neil Evans (1991) ‘The petty antics of the bell-ringing boisterousband?’ the women’s suffrage movement in Wales, 1890-1918, in Angela John(Ed.) Our Mothers’ Land, chapters in Welsh women’s history 1830-1939(Cardiff: University of Wales Press); Janet Lyon (1992) Militant discourse,strange bedfellows: suffragettes and vorticists before the war, Differences: aJournal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 4, pp. 100-133; Sandra Stanley Holton(1992) The suffragist and the ‘average woman’, Women’s History Review, 1,pp. 9-24; June Purvis (1994) A lost dimension? The political education ofwomen in the suffragette movement in Edwardian Britain, Gender andEducation, 6, pp. 319-327; June Purvis (1995) ‘Deeds, not words’: the dailylives of militant WSPU suffragettes in Edwardian Britain, Women’s StudiesInternational Forum, 18, forthcoming.

[2] The term ‘militant’ is usually applied to the activities of members of the WSPUand ‘constitutional’ to the law-abiding methods of the NUWSS, led by MrsMillicent Garrett Fawcett. The analytical imprecision of these terms, however,is explored in Holton, Feminism and Democracy, p. 4, where she points outthat if ‘militancy’ involved a preparedness to resort to extreme forms ofviolence (such as arson, bombing and vandalising pillar boxes and large-scale

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

125

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

window-smashing raids) then few ‘militants’ were ‘militant’ and then only from1912 onwards. If, as Holton argues, militancy concocted amongst NUWSSmembers a willingness to take the issues on to the streets, or if it sometimesindicted labour and socialist affiliations, then many ‘constitutionalists’ werealso ‘militant’. Similarly Purvis (1995) ‘Deeds, not words’, points out that tolabel all WSPU members ‘militant’ is to ignore the differentiation within theWSPU; in particular, I suggest that we might apply the label ‘militant’ to thatsmall number of WSPU members who engaged in such activities as arson andwindow smashing and ‘feminists’ to that much larger number of WSPUmembers who participated in ‘peaceful’ activities, such as taking part inprocessions and demonstrations, selling newspapers, doing general officework. I am not adopting this terminology in this article, however, but, instead,follow the practice amongst historians of referring to WSPU and NUWSSmembers as ‘suffragettes’ and ‘suffragists’, respectively. It is commonlybelieved that the term ‘suffragette’ was coined by the Daily Mail in 1906 todescribe WSPU activists – see A. E. Metcalfe (1917) Woman’s Effort, achronicle of British women’s fifty years’ struggle for citizenship (1865-1914),p. 36 (Oxford: B. H. Blackwell), and Rosen, Rise Up Women!, p. 65.

[3] Stanley with Morley, The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison, p. 175.

[4] Figures are calculated from the Roll of Honour, Suffragette Prisoners1905-1914 (n.d.) (Keighley: Rydal Press). It is impossible to be accurate here. Iam assuming that those listed with female or male first names are,respectively, women and men. I have excluded from my count the 49 personslisted with a surname but no Christian name or initial.

[5] For feminists, women’s ‘experiences’ have traditionally formed the bedrock offeminist knowledge and, in particular, their common experiences derived fromtheir subordination under patriarchy. Thus finding women’s voices in the pasthas been regarded as a critical concern for feminist historians who search for,and quote from, personal texts written by women, such as personal letters,diaries and autobiographies, as a way of documenting a woman’s ‘experience’.However, the term ‘experience’ has recently been subjected to critical enquiryby post-structuralists, especially in the USA. For example, Joan Scott (1991)The evidence of experience, Critical Inquiry, 17, Summer, p. 797, points outthat the historian cannot capture the lived reality of any one individual, acomment with which many historians would agree. Experience, she continues,“is a linguistic event ... Experience is a subject’s history. Language is the site ofhistory’s enactment” (p. 793). Yet again, most historians would agree thatlanguage is necessary for both the subject of history and for the historianstudying that subject to communicate his or her views. However, Scott thengoes further in her argument and states that historians “need to attend to thehistorical processes that, through discourse, position subjects and producetheir experiences” (p. 779). This notion that language/discourses ‘produce’experiences and the emphasis generally given by post-structuralists to thestudy of such phenomena rather than material reality has been stronglycriticised by a number of feminists – see, for example, the exchange betweenJoan Scott and Linda Gordon (1990) in Signs, 15, pp. 848-860; Kathleen

JUNE PURVIS

126

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

Canning (1994) Feminist history after the linguistic turn: historicizingdiscourse and experience, Signs, 19, pp. 368-404, and the critique ofpost-structuralism offered by Joan Hoff (1994) Gender as a postmoderncategory of paralysis, Women’s History Review, 3, pp. 149-168. Ruth RoachPierson (1991) Experience, difference, dominance and voice in the writing ofCanadian women’s history, in Karen Offen, Ruth Roach Pierson & JaneRendall (Eds) Writing Women’s History: international perspectives, pp.79-106 (Basingstoke: Macmillan) offers some particularly useful reflectionswhich have influenced my own views on the debate. Thus I argue that asuffragette’s experience of prison life, as evident in the various textsdocumenting that experience, was not a mere abstraction or a ‘discursive’reality; to claim that it was would be to deny that woman a subjectivity fromwhich to speak. Although any one text quoted in this article is not thatsuffragette’s experience but a representation of it, it was a lived experienceeven if mediated through her material, social and interpersonal context – aswell as the discourses of the day. Thus any one prisoner’s experience would beboth ‘subject to’ and the ‘subject of’ such phenomena – something aboutwhich we cannot draw clear hard and fast distinctions.

[6] Metcalfe, Woman’s Effort, p. 363.

[7] Kathryn Dodd (1990) Cultural politics and women’s historical writing: the caseof Ray Strachey’s The Cause, Women’s Studies International Forum, 13,p. 135.

[8] Strachey, ‘The Cause’, p. 314.

[9] Ibid., p. 314.

[10] George Dangerfield (1972 reprint edition) The Strange Death of LiberalEngland (London: Granada Publishing; first published 1935, London:McGibbon & Kee). The other forces include Tory rebellion over Home Rule forIreland and the rise of organised labour.

[11] Ibid., pp. 40, 135.

[12] Ibid., p. 145.

[13] Ibid., p. 145.

[14] Ibid., p. 163.

[15] Ibid., cited on the back cover.

[16] Jane Marcus (1987) Introduction to Marcus (Ed.) Suffrage and the Pankhursts,pp. 2-3.

[17] Fulford, Votes for Women, p. 176.

[18] Ibid., p. 206, my emphasis.

[19] Rosen, Rise Up Women!, p. 124.

[20] David Mitchell (1977) Queen Christabel, a biography of Christabel Pankhurst,p. 322 (London: MacDonald & Janes).

[21] Pugh, Women’s Suffrage in Britain, p. 25, my emphasis. The ‘Cat and MouseAct’ is the popular term for the Prisoners’ Temporary Discharge for Ill-HealthAct, rushed through Parliament in April 1913, which allowed prisoners who

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

127

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

had damaged their own health through their own conduct to be released intothe community and then, once fit, to be re-arrested to continue their sentence.The ‘Cat’ was the state and the ‘Mouse’ the suffragette, ‘clawed’ back at thewish of her tormentor.

[22] Harrison, ‘The act of militancy’, p. 27.

[23] Garner, Stepping Stones to Women’s Liberty, p. 49, my emphasis.

[24] Sheila Rowbotham (1973) Hidden from History: 300 years of women’soppression and the fight against it, p. 88 (London: Pluto Press).

[25] Sheila Rowbotham (1975 reprint edition) Women, Resistance and Revolutionp. 85 (Harmondsworth: Penguin; first published 1972, London: Allen Lane).

[26] Liddington & Norris (1978) One Hand Tied Behind Us (London: Virago). Seethe insightful review by Christine Stansell (1983) One Hand Tied Behind Us: areview essay, in Judith L. Newton, Mary P. Ryan & Judith R. Walkowitz (Eds)Sex and Class in Women’s History (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul).

[27] Liddington & Norris, One Hand Tied Behind Us, p. 207. A similar viewpoint isevident in Gifford Lewis (1988) Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper (London:Pandora Press); although Gore-Booth and Roper were from upper-middle andmiddle-class backgrounds, respectively, their work in campaigning forimprovements in the lives of working-class women is praised while the WSPU isseen as a ‘narrow’ movement that excluded working-class women.

[28] Stanley with Morley, The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison, p. 84. Seealso the sympathetic appraisals of the Pankhursts in Dale Spender (1982)Women of Ideas and What Men Have Done To Them: from Aphra Behn toAdrienne Rich, pp. 397-403 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul) and ElizabethSarah (1983) Christabel Pankhurst: reclaiming her power (1880-1958), in DaleSpender (Ed.) Feminist Theorists: three centuries of women’s intellectualtraditions, pp. 256-284 (London: The Women’s Press).

[29] Martha Vicinus (1985) Independent Women: work and community for singlewomen 1850-1920, pp. 263, 268 (London: Virago).

[30] Marcus, ‘Introduction’ to her Suffrage and the Pankhursts, pp. 1-2.

[31] Mary Jean Corbett (1992) Representing Femininity: middle-class subjectivityin Victorian and Edwardian women’s autobiographies, p. 163 (New York andOxford: Oxford University Press).

[32] Stanley with Morley, The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison, p. 85;Vicinus, Independent Women, p. 256; Marcus, ‘Introduction’ to her editedSuffrage and the Pankhursts, p. 4; Corbettt, Representations of Femininity,p. 169; Leneman, A Guid Cause, pp. 93-94; Cook & Evans (1991) ‘The pettyantics of the bell-ringing boisterous band?’, p. 159.

[33] For a discussion of some of the factors that may have framed the way thesetexts were written and of the problems involved when consulting andinterpreting such personal texts see Purvis, ‘Doing feminist women’s history’,pp. 178-184.

[34] Mrs Pankhurst (1908) Suffragists in prison, The Daily Telegraph, 18 February.

JUNE PURVIS

128

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

MPI

Fue

r E

thno

logi

sche

For

sc]

at 0

7:32

17

Apr

il 20

13

[35] The following information is taken from Maud Joachim (1908) My Life inHolloway Gaol, Votes for Women, 1 October, pp. 4-5, and Daisy DorotheaSolomon (n.d. 1909?) My Prison Experiences, leaflet reprinted from theChristian Commonwealth, 25 August 1909.

[36] The Times (1908) 18 November, House of Commons, Tuesday, 17 November.

[37] Tickner, The Spectacle of Women, p. 107.

[38] Joachim, ‘My life in Holloway Gaol’, p. 5.

[39] Unpublished letter dated 14 March 1912 from Katherine Gatty in Holloway toMrs Arney, Fawcett Library Autograph Letter Collection, London GuildhallUniversity.

[40] Unpublished letter dated 1 May 1912 from Mary C. Nesbitt to Miss Sinclair,Suffragette Fellowship Collection, Museum of London.

[41] Pankhurst, The Suffragette Movement, p. 446.

[42] Greta Cameron (1909) The spirit that upheld us, Votes for Women, 20 August,p. 108.

[43] Emmeline Pankhurst (1909) March, breast forward!, Votes for Women, 2 July,p. 880.

[44] Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence (1938) My Part in a Changing World, p. 188(London: Victor Gollancz).

[45] Rosen, Rise Up Women!, p. 211.